User login

Phototoxic Contact Dermatitis From Over-the-counter 8-Methoxypsoralen

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old Hispanic man with a history of vitiligo presented with an acute-onset blistering rash on the face, arms, and hands. Physical examination demonstrated photodistributed erythematous plaques with overlying vesicles and erosions with hemorrhagic crust on the face, neck, dorsal aspects of the hands, and wrists (Figure). Further history revealed that the patient applied a new cream that was recommended to treat vitiligo the night before the rash onset; he obtained the cream from a Central American market without a prescription. He had gone running in the park without any form of sun protection and then developed the rash within several hours. He denied taking any other medications or supplements. The involvement of sun-protected areas (ie, upper eyelids, nasolabial folds, submental area) was explained when the patient further elaborated that he had performed supine exercises during his outdoor recreation. He brought his new cream into the clinic, which was found to contain prescription-strength methoxsalen (8-methoxypsoralen), confirming the diagnosis of acute phototoxic contact dermatitis. The acute reaction had subsided, and the patient already had discontinued the causative agent. He was counseled on further avoidance of the cream and sun-protective measures.

The photosensitizing properties of certain compounds have been harnessed for therapeutic purposes. For example, psoralen plus UVA therapy has been used for psoriasis and vitiligo and photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses and superficial nonmelanoma skin cancers.1 However, these agents can induce severe phototoxicity if UV light exposure is not carefully monitored, as seen in our patient. This case is a classic example of phototoxic contact dermatitis and highlights the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history to allow for proper diagnosis and identification of the causative agent. Importantly, because prescription-strength topical medications are readily available over-the-counter, particularly in stores specializing in international goods, patients should be questioned about the use of all topical and systemic medications, both prescription and nonprescription.2

- Richard EG. The science and (lost) art of psoralen plus UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:11-23. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.08.002

- Kimyon RS, Schlarbaum JP, Liou YL, et al. Prescription-strengthtopical corticosteroids available over the counter: cross-sectional study of 80 stores in 13 United States cities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:524-525. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.035

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old Hispanic man with a history of vitiligo presented with an acute-onset blistering rash on the face, arms, and hands. Physical examination demonstrated photodistributed erythematous plaques with overlying vesicles and erosions with hemorrhagic crust on the face, neck, dorsal aspects of the hands, and wrists (Figure). Further history revealed that the patient applied a new cream that was recommended to treat vitiligo the night before the rash onset; he obtained the cream from a Central American market without a prescription. He had gone running in the park without any form of sun protection and then developed the rash within several hours. He denied taking any other medications or supplements. The involvement of sun-protected areas (ie, upper eyelids, nasolabial folds, submental area) was explained when the patient further elaborated that he had performed supine exercises during his outdoor recreation. He brought his new cream into the clinic, which was found to contain prescription-strength methoxsalen (8-methoxypsoralen), confirming the diagnosis of acute phototoxic contact dermatitis. The acute reaction had subsided, and the patient already had discontinued the causative agent. He was counseled on further avoidance of the cream and sun-protective measures.

The photosensitizing properties of certain compounds have been harnessed for therapeutic purposes. For example, psoralen plus UVA therapy has been used for psoriasis and vitiligo and photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses and superficial nonmelanoma skin cancers.1 However, these agents can induce severe phototoxicity if UV light exposure is not carefully monitored, as seen in our patient. This case is a classic example of phototoxic contact dermatitis and highlights the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history to allow for proper diagnosis and identification of the causative agent. Importantly, because prescription-strength topical medications are readily available over-the-counter, particularly in stores specializing in international goods, patients should be questioned about the use of all topical and systemic medications, both prescription and nonprescription.2

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old Hispanic man with a history of vitiligo presented with an acute-onset blistering rash on the face, arms, and hands. Physical examination demonstrated photodistributed erythematous plaques with overlying vesicles and erosions with hemorrhagic crust on the face, neck, dorsal aspects of the hands, and wrists (Figure). Further history revealed that the patient applied a new cream that was recommended to treat vitiligo the night before the rash onset; he obtained the cream from a Central American market without a prescription. He had gone running in the park without any form of sun protection and then developed the rash within several hours. He denied taking any other medications or supplements. The involvement of sun-protected areas (ie, upper eyelids, nasolabial folds, submental area) was explained when the patient further elaborated that he had performed supine exercises during his outdoor recreation. He brought his new cream into the clinic, which was found to contain prescription-strength methoxsalen (8-methoxypsoralen), confirming the diagnosis of acute phototoxic contact dermatitis. The acute reaction had subsided, and the patient already had discontinued the causative agent. He was counseled on further avoidance of the cream and sun-protective measures.

The photosensitizing properties of certain compounds have been harnessed for therapeutic purposes. For example, psoralen plus UVA therapy has been used for psoriasis and vitiligo and photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses and superficial nonmelanoma skin cancers.1 However, these agents can induce severe phototoxicity if UV light exposure is not carefully monitored, as seen in our patient. This case is a classic example of phototoxic contact dermatitis and highlights the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history to allow for proper diagnosis and identification of the causative agent. Importantly, because prescription-strength topical medications are readily available over-the-counter, particularly in stores specializing in international goods, patients should be questioned about the use of all topical and systemic medications, both prescription and nonprescription.2

- Richard EG. The science and (lost) art of psoralen plus UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:11-23. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.08.002

- Kimyon RS, Schlarbaum JP, Liou YL, et al. Prescription-strengthtopical corticosteroids available over the counter: cross-sectional study of 80 stores in 13 United States cities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:524-525. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.035

- Richard EG. The science and (lost) art of psoralen plus UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:11-23. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.08.002

- Kimyon RS, Schlarbaum JP, Liou YL, et al. Prescription-strengthtopical corticosteroids available over the counter: cross-sectional study of 80 stores in 13 United States cities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:524-525. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.035

Practice Points

- Phototoxic contact dermatitis is an irritant reaction resembling an exaggerated sunburn that occurs with the use of a photosensitizing agent and UV light exposure.

- A range of topical and systemic medications, plants, and natural products can elicit phototoxic reactions.

- With the wide availability of prescription-strength over-the-counter medications, a detailed history often is necessary to identify the causative agents of phototoxic contact dermatitis and ensure future avoidance.

Pencil-core Granuloma Forming 62 Years After Initial Injury

To the Editor:

Trauma from a pencil tip can sometimes result in a fragment of lead being left embedded within the skin. Pencil lead is composed of 66% graphite carbon, 26% aluminum silicate, and 8% paraffin.1,2 While the toxicity of these individual elements is low, paraffin can cause nonallergic foreign-body reactions, aluminum silicate can induce epithelioid granulomatous reactions, and graphite has been reported to cause chronic granulomatous reactions in the lungs of those who work with graphite.2 Penetrating trauma with a pencil can result in the formation of a cutaneous granulomatous reaction that can sometimes occur years to decades after the initial injury.3,4 Several cases of pencil-core granulomas have been published, with lag times between the initial trauma and lesion growth as long as 58 years.1-10 The pencil-core granuloma may simulate malignant melanoma, as it presents clinically as a growing, darkly pigmented lesion, thus prompting biopsy. We present a case of a pencil-core granuloma that began to grow 62 years after the initial trauma.

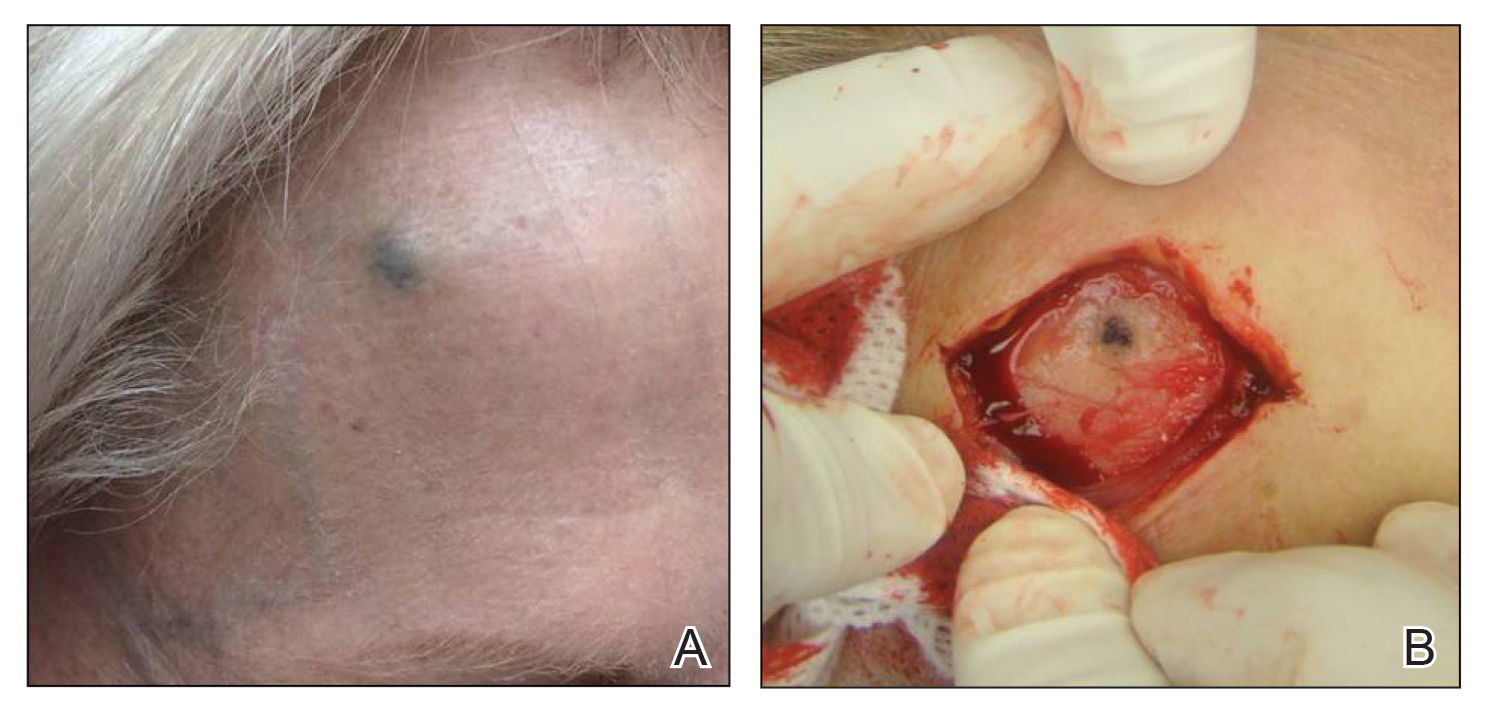

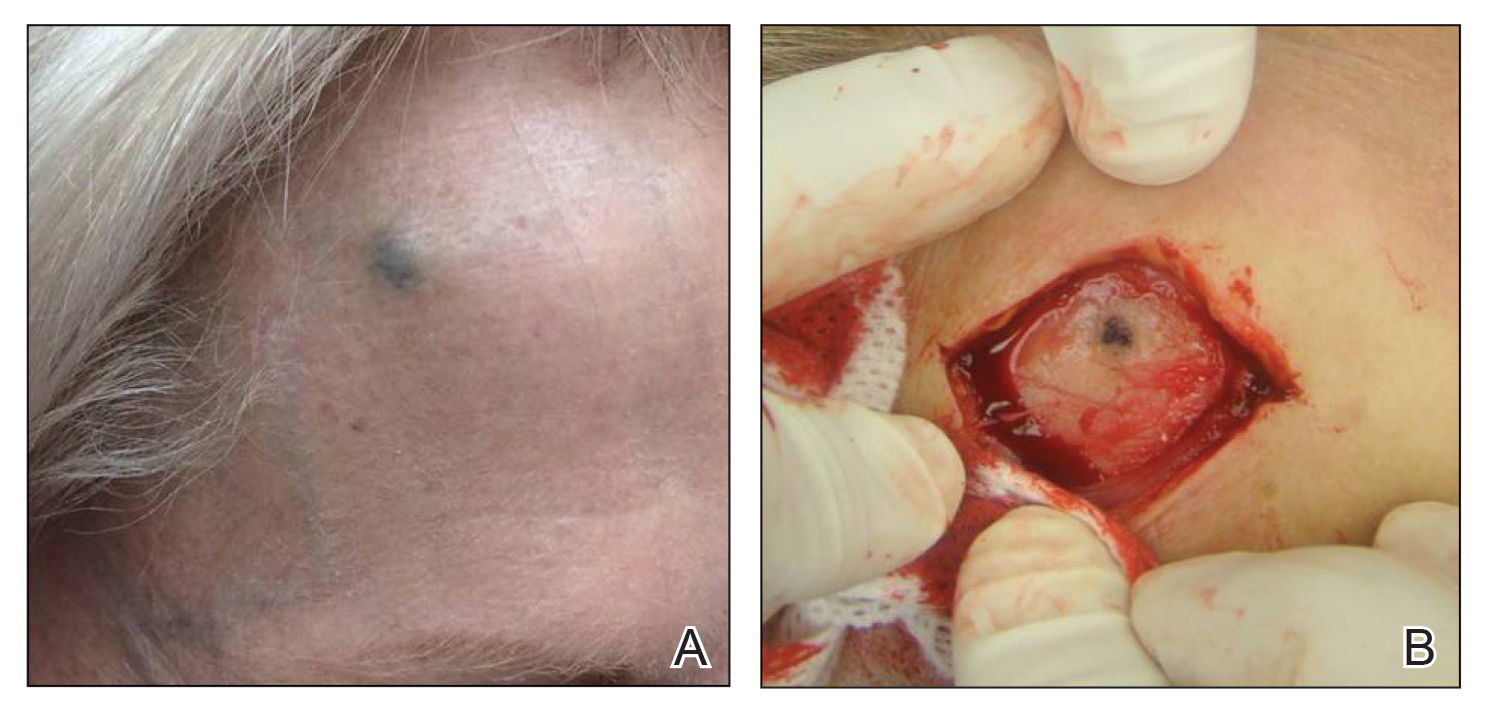

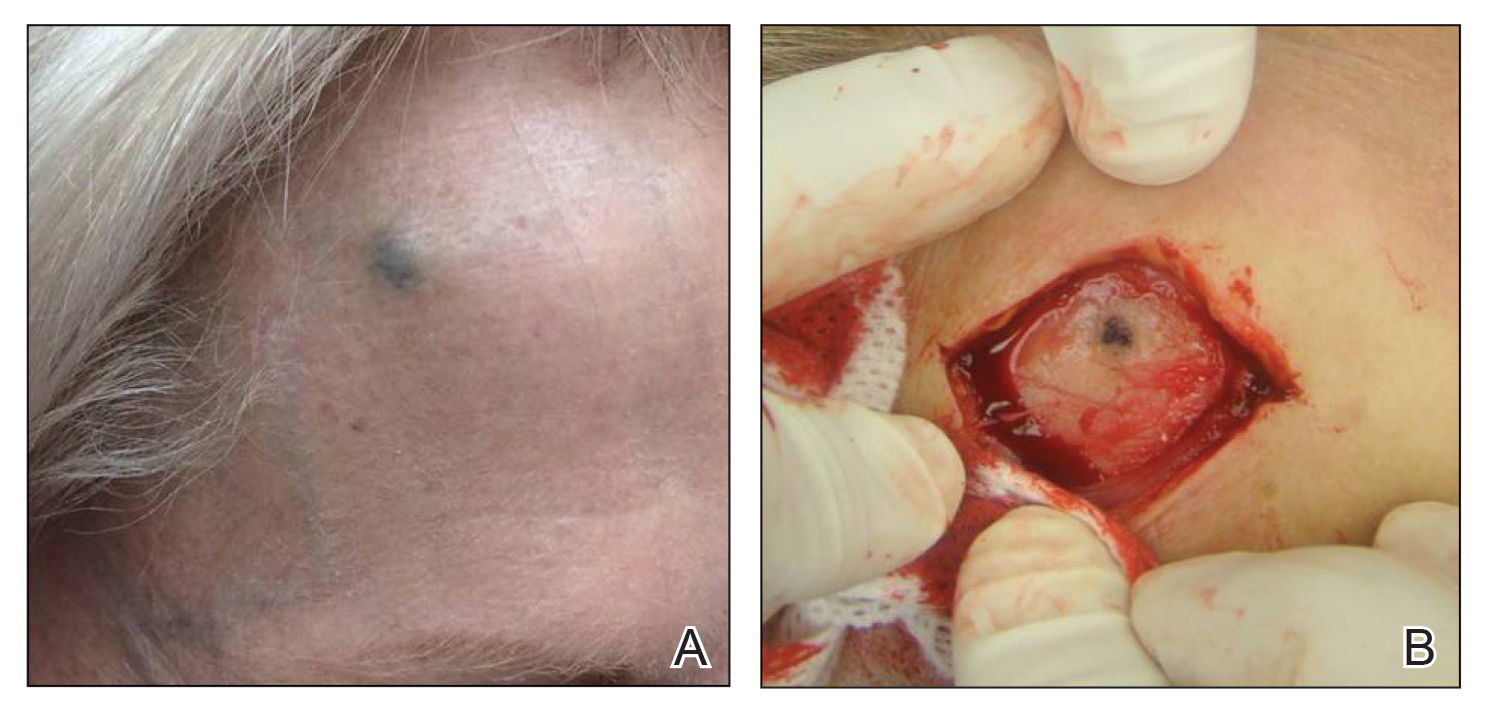

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a dark nodule on the forehead. The lesion had been present since the age of 10 years, reportedly from an accidental stabbing with a pencil. The lesion had been flat, stable, and asymptomatic since the trauma occurred; however, the patient reported that approximately 9 months prior to presentation, it had started growing and became painful. Physical examination revealed a 1.0-cm, round, bluish-black nodule on the right superior forehead (Figure 1A). No satellite lesions or local lymphadenopathy were noted on general examination.

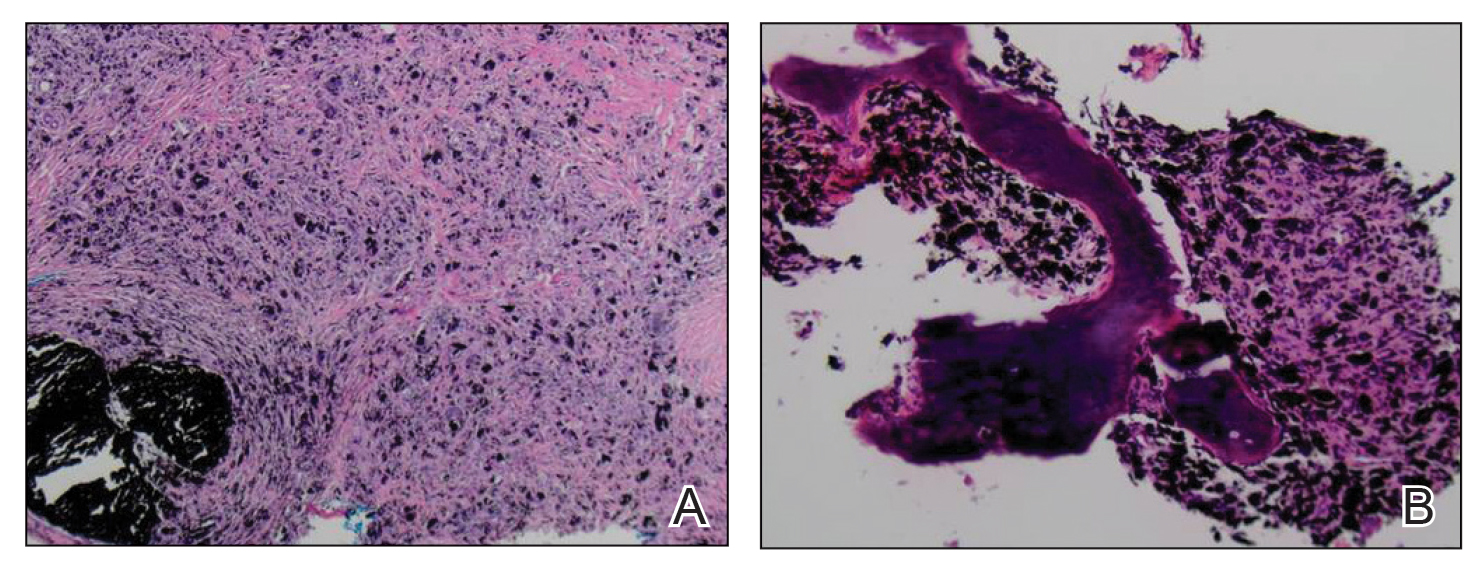

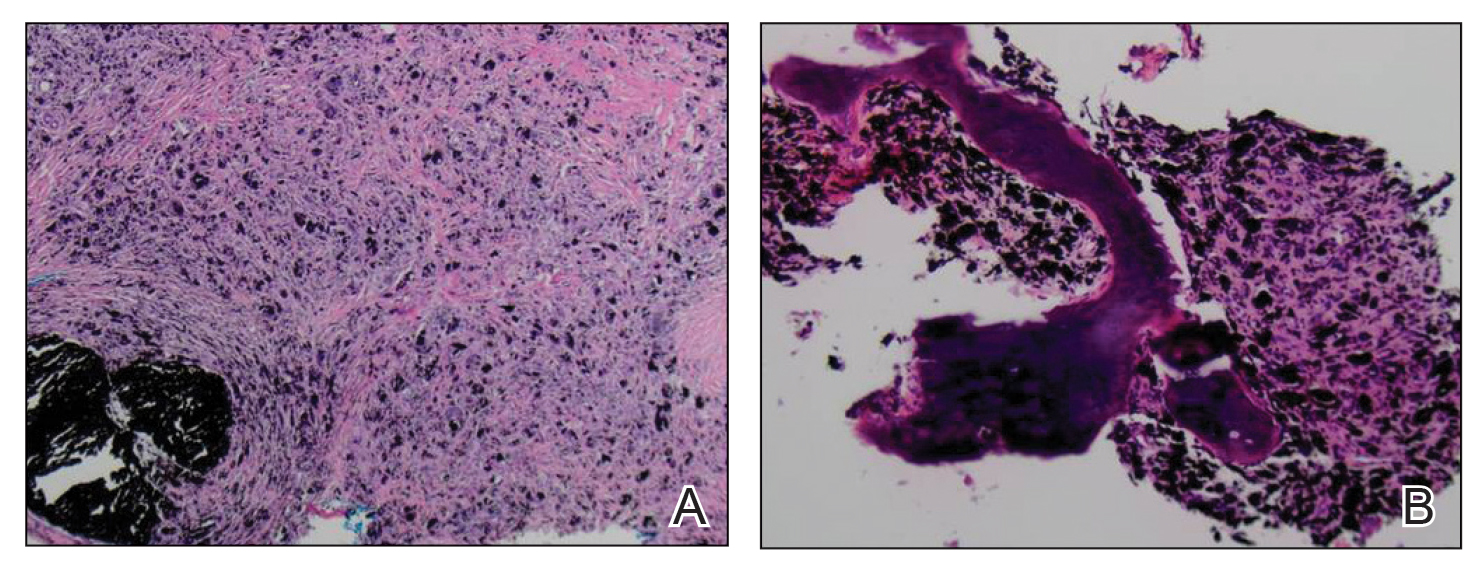

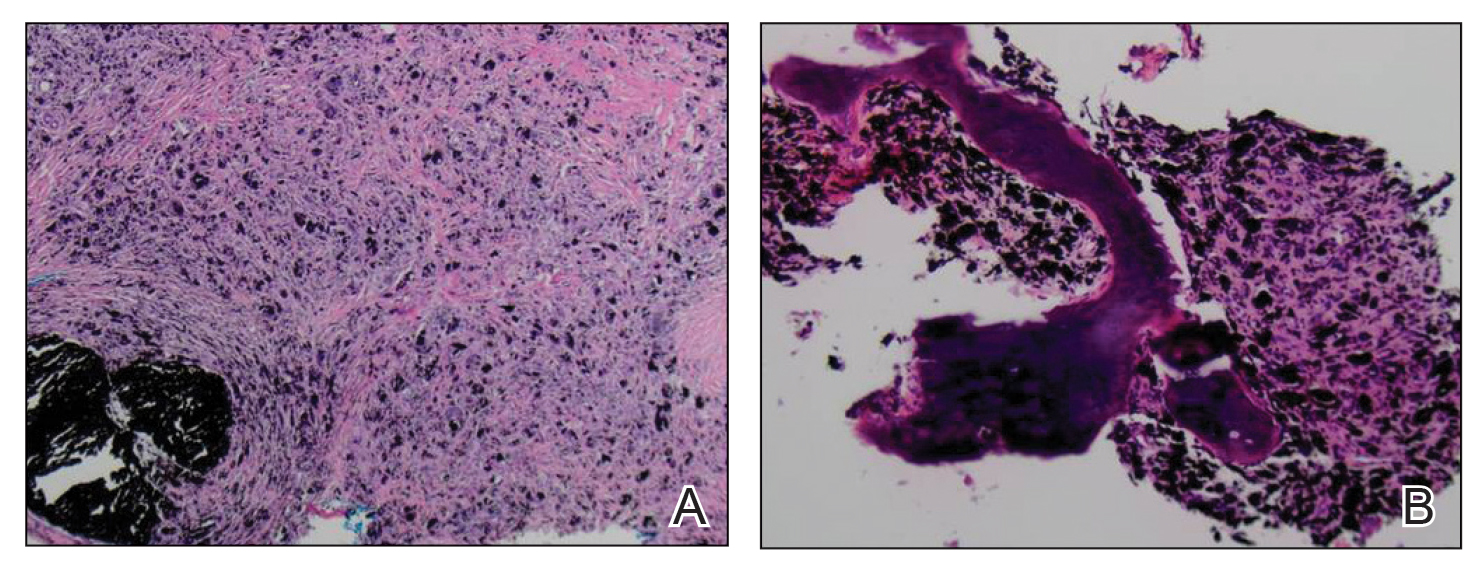

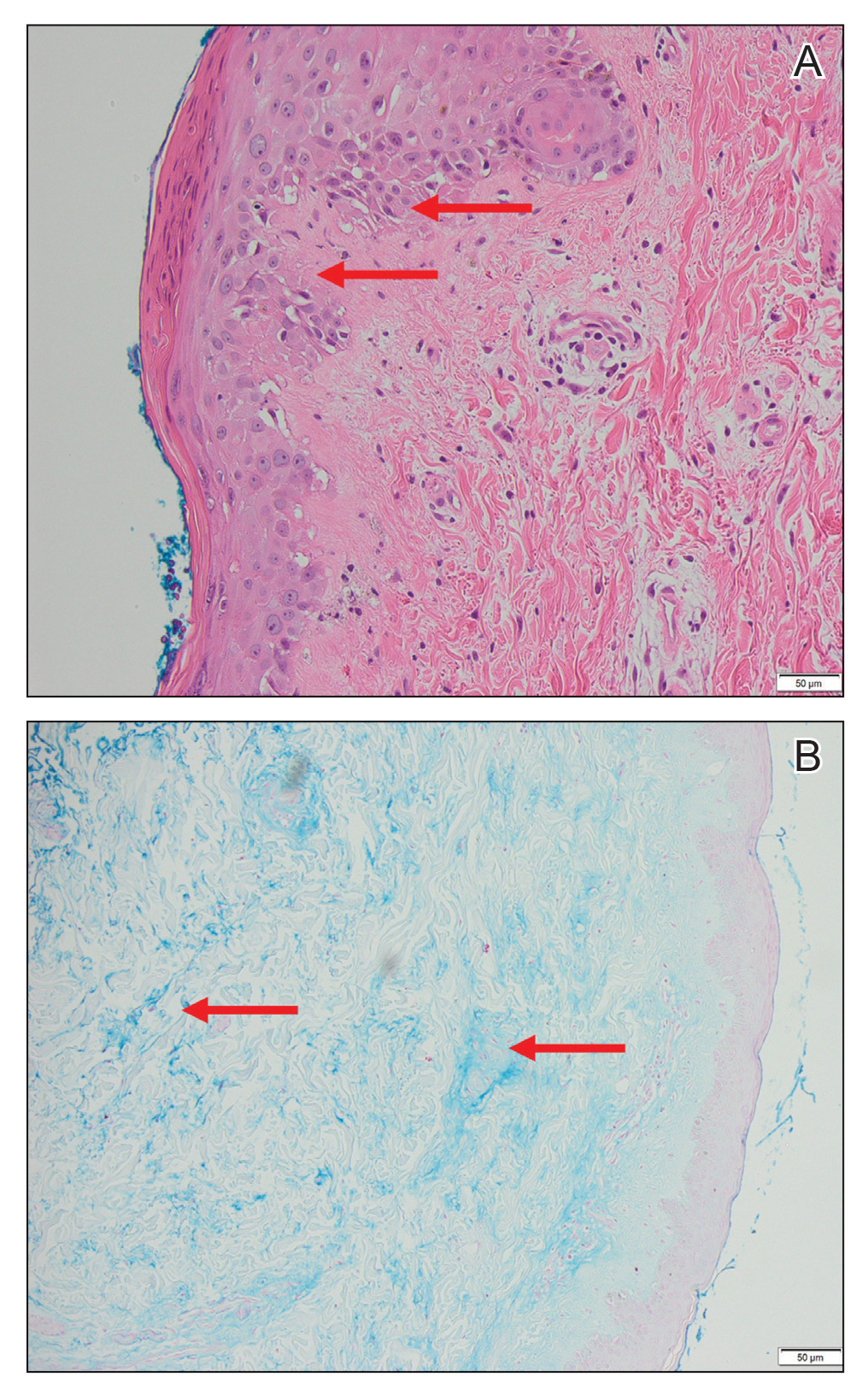

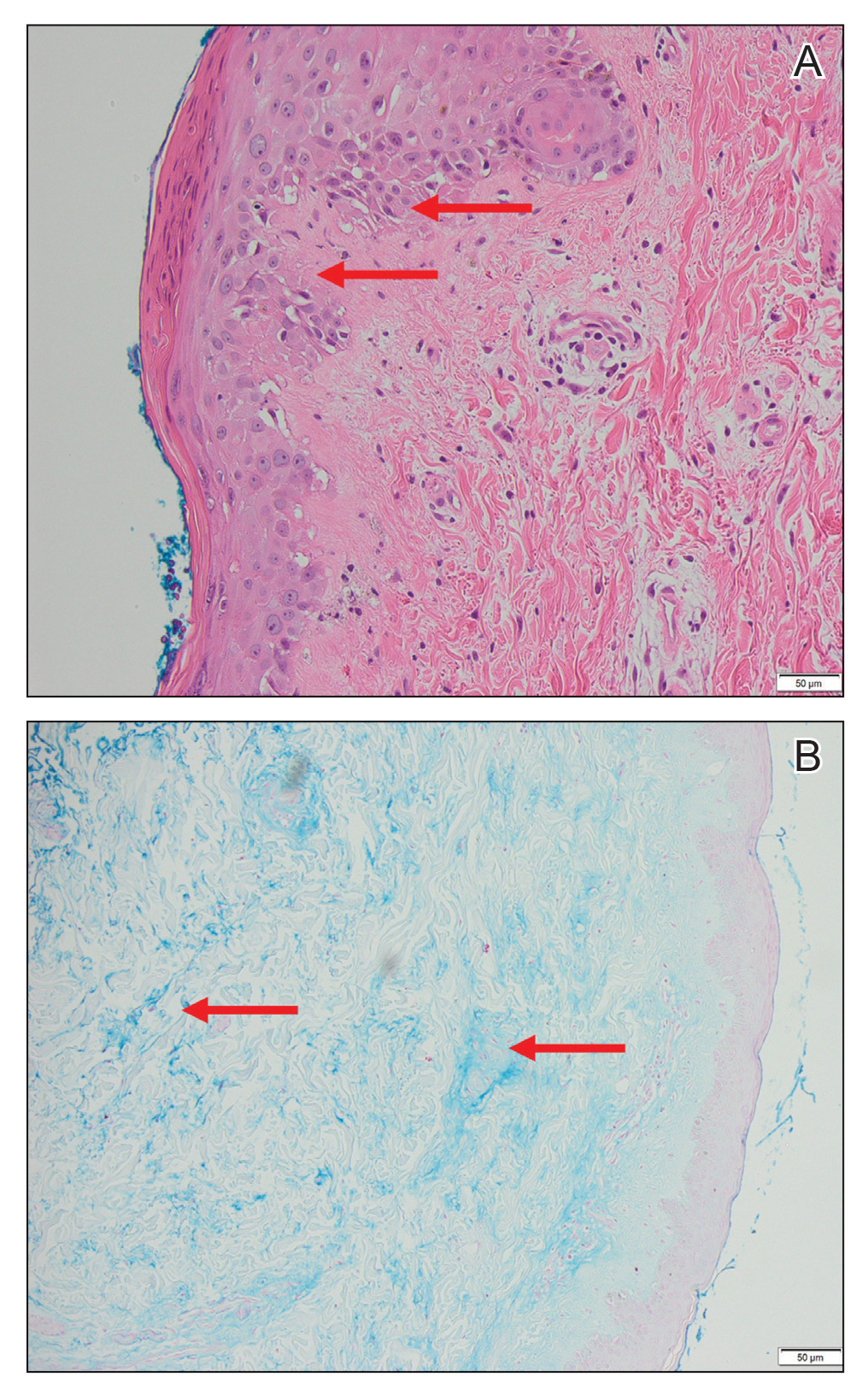

An elliptical excision of the lesion with 1-cm margins revealed a bluish-black mass extending through the dermis, through the frontalis muscle, and into the periosteum and frontal bone (Figure 1B). A No. 15 blade was then used to remove the remaining pigment from the outer table of the frontal bone. Histopathologic findings demonstrated a sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis associated with abundant, nonpolarizable, black, granular pigment consistent with carbon tattoo. This foreign material was readily identifiable in large extracellular deposits and also within histiocytes, including numerous multinucleated giant cells (Figure 2). Immunostaining for MART-1 and SOX-10 antigens failed to demonstrate a melanocytic proliferation. These findings were consistent with a sarcoidal foreign-body granulomatous reaction to carbon tattoo following traumatic graphite implantation.

Granulomatous reactions to carbon tattoo may be sarcoidal (foreign-body granulomatous dermatitis), palisading, or rarely tuberculoid (caseating). Sarcoidal granulomatous tattoo reactions may occur in patients with sarcoidosis due to koebnerization, and histology alone is not discriminatory; however, in our patient, the absence of underlying sarcoidosis or clinical or histologic findings of sarcoidosis outside of the site of the pencil-core granuloma excluded that possibility.11 Pencil-core granulomas are characterized by a delayed foreign-body reaction to retained fragments of lead often years following a penetrating trauma with a pencil. Previous reports have described various lag times from injury to lesion growth of up to 58 years.1-10 Our patient claimed to have noticed the lesion growing and becoming painful only after a 62-year lag time following the initial trauma. To our knowledge, this is the longest lag time between the initial pencil injury and induction of the foreign-body reaction reported in the literature. Clinically, the lesion appeared and behaved very similar to a melanoma, prompting further treatment and evaluation.

It has been suggested that the lag period between the initial trauma and the rapid growth of the lesion may correspond to the amount of time required for the breakdown of the pencil lead to a critical size followed by the dispersal of those particles within the interstitium, where they can induce a granulomatous reaction.1,2,9 One case described a patient who reported that the growth and clinical change of the pencil-core granuloma only started when the patient accidentally hit the area where the trauma had occurred 31 years prior.1 This additional trauma may have caused further mechanical breakdown of the lead to set off the tissue reaction. In our case, the patient did not recall any additional trauma to the head prior to the onset of growth of the nodule on the forehead.

Our case indicates that carbon tattoo may be a possible sequela of a penetrating injury from a pencil with retained pencil lead fragments; however, many of these carbon tattoos may remain stable throughout the remainder of the patient’s life.

- Gormley RH, Kovach SJ III, Zhang PJ. Role for trauma in inducing pencil “lead” granuloma in the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1074-1075.

- Terasawa N, Kishimoto S, Kibe Y, et al. Graphite foreign body granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:774-776.

- Fukunaga Y, Hashimoto I, Nakanishi H, et al. Pencil-core granuloma of the face: report of two rare cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1235-1237.

- Aswani VH, Kim SL. Fifty-three years after a pencil puncture wound. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:303-305.

- Taylor B, Frumkin A, Pitha JV. Delayed reaction to “lead” pencil simulating melanoma. Cutis. 1988;42:199-201.

- Granick MS, Erickson ER, Solomon MP. Pencil-core granuloma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:136-138.

- Andreano J. Stump the experts. foreign body granuloma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:277, 343.

- Yoshitatsu S, Takagi T. A case of giant pencil-core granuloma. J Dermatol. 2000;27:329-332.

- Hatano Y, Asada Y, Komada S, et al. A case of pencil core granuloma with an unusual temporal profile. Dermatology. 2000;201:151-153.

- Seitz IA, Silva BA, Schechter LS. Unusual sequela from a pencil stab wound reveals a retained graphite foreign body. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:568-570.

- Motaparthi K. Tattoo ink. In: Cockerell CJ, Hall BJ, eds. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Amirsys; 2016: 270.

To the Editor:

Trauma from a pencil tip can sometimes result in a fragment of lead being left embedded within the skin. Pencil lead is composed of 66% graphite carbon, 26% aluminum silicate, and 8% paraffin.1,2 While the toxicity of these individual elements is low, paraffin can cause nonallergic foreign-body reactions, aluminum silicate can induce epithelioid granulomatous reactions, and graphite has been reported to cause chronic granulomatous reactions in the lungs of those who work with graphite.2 Penetrating trauma with a pencil can result in the formation of a cutaneous granulomatous reaction that can sometimes occur years to decades after the initial injury.3,4 Several cases of pencil-core granulomas have been published, with lag times between the initial trauma and lesion growth as long as 58 years.1-10 The pencil-core granuloma may simulate malignant melanoma, as it presents clinically as a growing, darkly pigmented lesion, thus prompting biopsy. We present a case of a pencil-core granuloma that began to grow 62 years after the initial trauma.

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a dark nodule on the forehead. The lesion had been present since the age of 10 years, reportedly from an accidental stabbing with a pencil. The lesion had been flat, stable, and asymptomatic since the trauma occurred; however, the patient reported that approximately 9 months prior to presentation, it had started growing and became painful. Physical examination revealed a 1.0-cm, round, bluish-black nodule on the right superior forehead (Figure 1A). No satellite lesions or local lymphadenopathy were noted on general examination.

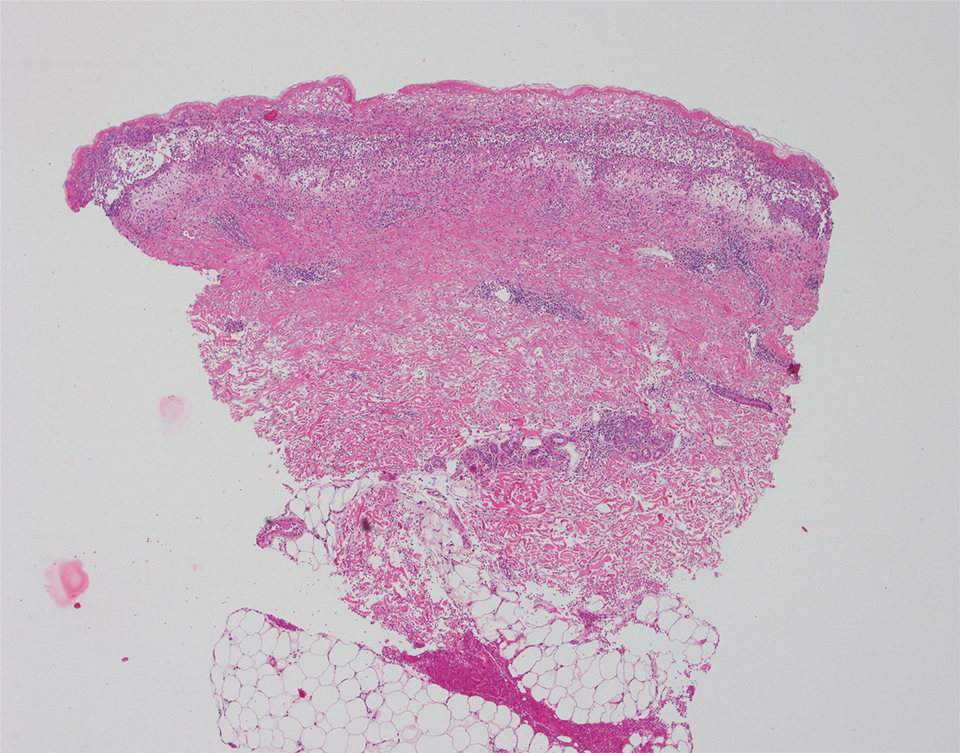

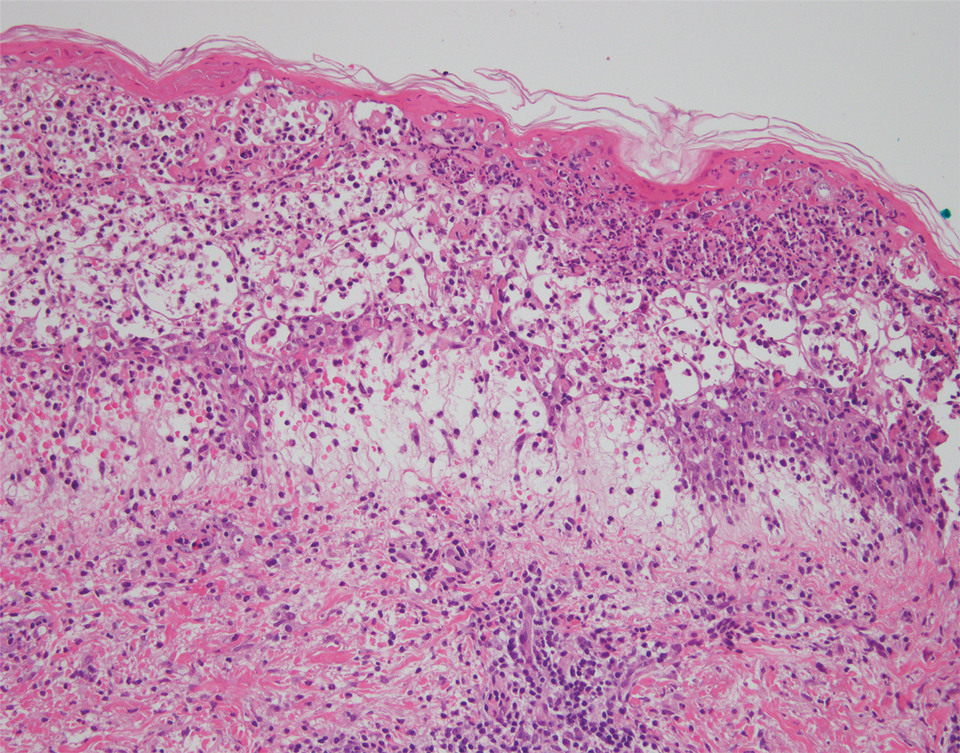

An elliptical excision of the lesion with 1-cm margins revealed a bluish-black mass extending through the dermis, through the frontalis muscle, and into the periosteum and frontal bone (Figure 1B). A No. 15 blade was then used to remove the remaining pigment from the outer table of the frontal bone. Histopathologic findings demonstrated a sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis associated with abundant, nonpolarizable, black, granular pigment consistent with carbon tattoo. This foreign material was readily identifiable in large extracellular deposits and also within histiocytes, including numerous multinucleated giant cells (Figure 2). Immunostaining for MART-1 and SOX-10 antigens failed to demonstrate a melanocytic proliferation. These findings were consistent with a sarcoidal foreign-body granulomatous reaction to carbon tattoo following traumatic graphite implantation.

Granulomatous reactions to carbon tattoo may be sarcoidal (foreign-body granulomatous dermatitis), palisading, or rarely tuberculoid (caseating). Sarcoidal granulomatous tattoo reactions may occur in patients with sarcoidosis due to koebnerization, and histology alone is not discriminatory; however, in our patient, the absence of underlying sarcoidosis or clinical or histologic findings of sarcoidosis outside of the site of the pencil-core granuloma excluded that possibility.11 Pencil-core granulomas are characterized by a delayed foreign-body reaction to retained fragments of lead often years following a penetrating trauma with a pencil. Previous reports have described various lag times from injury to lesion growth of up to 58 years.1-10 Our patient claimed to have noticed the lesion growing and becoming painful only after a 62-year lag time following the initial trauma. To our knowledge, this is the longest lag time between the initial pencil injury and induction of the foreign-body reaction reported in the literature. Clinically, the lesion appeared and behaved very similar to a melanoma, prompting further treatment and evaluation.

It has been suggested that the lag period between the initial trauma and the rapid growth of the lesion may correspond to the amount of time required for the breakdown of the pencil lead to a critical size followed by the dispersal of those particles within the interstitium, where they can induce a granulomatous reaction.1,2,9 One case described a patient who reported that the growth and clinical change of the pencil-core granuloma only started when the patient accidentally hit the area where the trauma had occurred 31 years prior.1 This additional trauma may have caused further mechanical breakdown of the lead to set off the tissue reaction. In our case, the patient did not recall any additional trauma to the head prior to the onset of growth of the nodule on the forehead.

Our case indicates that carbon tattoo may be a possible sequela of a penetrating injury from a pencil with retained pencil lead fragments; however, many of these carbon tattoos may remain stable throughout the remainder of the patient’s life.

To the Editor:

Trauma from a pencil tip can sometimes result in a fragment of lead being left embedded within the skin. Pencil lead is composed of 66% graphite carbon, 26% aluminum silicate, and 8% paraffin.1,2 While the toxicity of these individual elements is low, paraffin can cause nonallergic foreign-body reactions, aluminum silicate can induce epithelioid granulomatous reactions, and graphite has been reported to cause chronic granulomatous reactions in the lungs of those who work with graphite.2 Penetrating trauma with a pencil can result in the formation of a cutaneous granulomatous reaction that can sometimes occur years to decades after the initial injury.3,4 Several cases of pencil-core granulomas have been published, with lag times between the initial trauma and lesion growth as long as 58 years.1-10 The pencil-core granuloma may simulate malignant melanoma, as it presents clinically as a growing, darkly pigmented lesion, thus prompting biopsy. We present a case of a pencil-core granuloma that began to grow 62 years after the initial trauma.

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a dark nodule on the forehead. The lesion had been present since the age of 10 years, reportedly from an accidental stabbing with a pencil. The lesion had been flat, stable, and asymptomatic since the trauma occurred; however, the patient reported that approximately 9 months prior to presentation, it had started growing and became painful. Physical examination revealed a 1.0-cm, round, bluish-black nodule on the right superior forehead (Figure 1A). No satellite lesions or local lymphadenopathy were noted on general examination.

An elliptical excision of the lesion with 1-cm margins revealed a bluish-black mass extending through the dermis, through the frontalis muscle, and into the periosteum and frontal bone (Figure 1B). A No. 15 blade was then used to remove the remaining pigment from the outer table of the frontal bone. Histopathologic findings demonstrated a sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis associated with abundant, nonpolarizable, black, granular pigment consistent with carbon tattoo. This foreign material was readily identifiable in large extracellular deposits and also within histiocytes, including numerous multinucleated giant cells (Figure 2). Immunostaining for MART-1 and SOX-10 antigens failed to demonstrate a melanocytic proliferation. These findings were consistent with a sarcoidal foreign-body granulomatous reaction to carbon tattoo following traumatic graphite implantation.

Granulomatous reactions to carbon tattoo may be sarcoidal (foreign-body granulomatous dermatitis), palisading, or rarely tuberculoid (caseating). Sarcoidal granulomatous tattoo reactions may occur in patients with sarcoidosis due to koebnerization, and histology alone is not discriminatory; however, in our patient, the absence of underlying sarcoidosis or clinical or histologic findings of sarcoidosis outside of the site of the pencil-core granuloma excluded that possibility.11 Pencil-core granulomas are characterized by a delayed foreign-body reaction to retained fragments of lead often years following a penetrating trauma with a pencil. Previous reports have described various lag times from injury to lesion growth of up to 58 years.1-10 Our patient claimed to have noticed the lesion growing and becoming painful only after a 62-year lag time following the initial trauma. To our knowledge, this is the longest lag time between the initial pencil injury and induction of the foreign-body reaction reported in the literature. Clinically, the lesion appeared and behaved very similar to a melanoma, prompting further treatment and evaluation.

It has been suggested that the lag period between the initial trauma and the rapid growth of the lesion may correspond to the amount of time required for the breakdown of the pencil lead to a critical size followed by the dispersal of those particles within the interstitium, where they can induce a granulomatous reaction.1,2,9 One case described a patient who reported that the growth and clinical change of the pencil-core granuloma only started when the patient accidentally hit the area where the trauma had occurred 31 years prior.1 This additional trauma may have caused further mechanical breakdown of the lead to set off the tissue reaction. In our case, the patient did not recall any additional trauma to the head prior to the onset of growth of the nodule on the forehead.

Our case indicates that carbon tattoo may be a possible sequela of a penetrating injury from a pencil with retained pencil lead fragments; however, many of these carbon tattoos may remain stable throughout the remainder of the patient’s life.

- Gormley RH, Kovach SJ III, Zhang PJ. Role for trauma in inducing pencil “lead” granuloma in the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1074-1075.

- Terasawa N, Kishimoto S, Kibe Y, et al. Graphite foreign body granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:774-776.

- Fukunaga Y, Hashimoto I, Nakanishi H, et al. Pencil-core granuloma of the face: report of two rare cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1235-1237.

- Aswani VH, Kim SL. Fifty-three years after a pencil puncture wound. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:303-305.

- Taylor B, Frumkin A, Pitha JV. Delayed reaction to “lead” pencil simulating melanoma. Cutis. 1988;42:199-201.

- Granick MS, Erickson ER, Solomon MP. Pencil-core granuloma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:136-138.

- Andreano J. Stump the experts. foreign body granuloma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:277, 343.

- Yoshitatsu S, Takagi T. A case of giant pencil-core granuloma. J Dermatol. 2000;27:329-332.

- Hatano Y, Asada Y, Komada S, et al. A case of pencil core granuloma with an unusual temporal profile. Dermatology. 2000;201:151-153.

- Seitz IA, Silva BA, Schechter LS. Unusual sequela from a pencil stab wound reveals a retained graphite foreign body. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:568-570.

- Motaparthi K. Tattoo ink. In: Cockerell CJ, Hall BJ, eds. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Amirsys; 2016: 270.

- Gormley RH, Kovach SJ III, Zhang PJ. Role for trauma in inducing pencil “lead” granuloma in the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1074-1075.

- Terasawa N, Kishimoto S, Kibe Y, et al. Graphite foreign body granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:774-776.

- Fukunaga Y, Hashimoto I, Nakanishi H, et al. Pencil-core granuloma of the face: report of two rare cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1235-1237.

- Aswani VH, Kim SL. Fifty-three years after a pencil puncture wound. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:303-305.

- Taylor B, Frumkin A, Pitha JV. Delayed reaction to “lead” pencil simulating melanoma. Cutis. 1988;42:199-201.

- Granick MS, Erickson ER, Solomon MP. Pencil-core granuloma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:136-138.

- Andreano J. Stump the experts. foreign body granuloma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:277, 343.

- Yoshitatsu S, Takagi T. A case of giant pencil-core granuloma. J Dermatol. 2000;27:329-332.

- Hatano Y, Asada Y, Komada S, et al. A case of pencil core granuloma with an unusual temporal profile. Dermatology. 2000;201:151-153.

- Seitz IA, Silva BA, Schechter LS. Unusual sequela from a pencil stab wound reveals a retained graphite foreign body. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:568-570.

- Motaparthi K. Tattoo ink. In: Cockerell CJ, Hall BJ, eds. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Amirsys; 2016: 270.

Practice Points

- Pencil-core granulomas can arise even decades after the lead is embedded in the skin.

- It is important to biopsy to confirm the diagnosis, as pencil-core granulomas can very closely mimic melanomas.

Lower Leg Hyperpigmentation in MYH9-Related Disorder

To the Editor:

MYH9-related disorder is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by macrothrombocytopenia and neutrophil inclusions secondary to defective myosin-9.1 We describe a case of lower leg hyperpigmentation secondary to hemosiderin deposition from MYH9-related disorder.

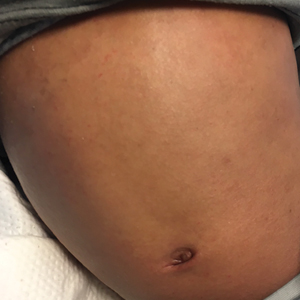

A 31-year-old woman with a history of MYH9-related disorder and mixed connective tissue disease presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with asymptomatic brown patches on the lower legs (Figure) of 10 years’ duration. She also had epistaxis, hearing loss, renal disease, and menorrhagia secondary to MYH9-related disorder. The patient had been started on hydroxychloroquine 2 years earlier by rheumatology for mixed connective tissue disorder. A biopsy was not performed, given the risk of bleeding from thrombocytopenia. Ammonium lactate lotion was recommended for the leg patches. No further interventions were undertaken. At 6-month follow-up, hyperpigmentation on the lower legs was stable. The patient expressed no desire for cosmetic intervention.

Prior to discovery of a common gene, MYH9-related disorder was classified as 4 overlapping syndromes: May-Hegglin anomaly, Epstein syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Sebastian syndrome.2 More than 30 MYH9 mutations have been identified, all of which encode for myosin-9, a subunit of myosin IIA,1,3 that is a nonmuscle myosin needed for cell movement, shape, and cytokinesis. Although most cells use myosin IIA to IIC, certain cells, such as platelets and neutrophils, use myosin IIA exclusively.

In neutrophils of patients with MYH9-related disorder, nonfunctional myosin-9 clumps to form hallmark inclusion bodies, which are seen on the peripheral blood smear. Macrothrombocytopenia, another hallmark of MYH9-related disorder, also can be seen on the peripheral smear of all affected patients. Approximately 30%of patients develop clinical manifestations of the disorder (eg, bleeding, renal failure, hearing loss, presenile cataracts). Bleeding tendency usually is mild; epistaxis and menorrhagia are the most common hematologic manifestations.4

We attribute the lower leg hyperpigmentation in our patient to a severe phenotype of MYH9-related disorder. In addition to hyperpigmentation, our patient had menorrhagia requiring treatment with tranexamic acid, renal failure, and hearing loss, further pointing to a more severe phenotype. Furthermore, it is likely that our patient’s hyperpigmentation was made worse by hydroxychloroquine and a coexisting diagnosis of mixed connective tissue disease, which led to a propensity for increased vessel fragility in the setting of thrombocytopenia.

The workup of suspected MYH9-related disorder includes exclusion of iron-deficiency anemia, which can increase bleeding in patients with the disorder. The presence of small red blood cells (RBCs) in microcytic anemia and large platelets of MYH9-related disorder can lead to a situation in which platelets travel near the center of the lumen of blood vessels, while RBCs travel to the periphery. This decrease in the platelet-endothelium interaction increases the risk for bleeding. Our patient’s hemoglobin level was within reference range, without evidence of iron-deficiency anemia. Correction of iron-deficiency anemia, if applicable, can prevent bleeding brought on by the mechanism of decreased platelet-endothelium interaction and avoid unnecessary antiplatelet medication because of misdiagnosis based on an erroneous platelet count.

The workup of MYH9-related disorder also should include audiography, ophthalmologic examination, and renal function testing for hearing loss, cataracts, and renal disease, respectively. Referral to genetics also may be warranted.

It also is of clinical interest that automated cell counters may underestimate the count of abnormally large platelets in MYH9-related disorder, counting them as RBCs or white blood cells. The platelet count in MYH9-related disorder may be underestimated by 4-fold or greater.4-7

Treatment of leg hyperpigmentation can prove challenging, given the location of dermal hemosiderin. Topical therapy likely is ineffective. Lasers and intense pulsed light therapy are treatment modalities to consider for the hyperpigmentation of MYH9-related disorder. There have been reports of improved cosmesis in dermal hemosiderin depositional disorders, such as venous stasis.4 Our patient was given ammonium lactate lotion to thicken collagen, possibly preventing future bleeding episodes.

- Pecci A, Canobbio I, Balduini A, et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hematological abnormalities of patients with MYH9 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3169-3178. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi344

- Seri M, Pecci A, Di Bari F, et al. MYH9-related disease: May-Hegglin anomaly, Sebastian syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Epstein syndrome are not distinct entities but represent a variable expression of a single illness. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:203-215. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000076006.64510.5c

- Medline Plus. MYH9-related disorder. National Library of Medicine website. Updated August 18, 2020. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/myh9-related-disorder#diagnosis

- Althaus K, Greinachar A. MYH9-related platelet disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:189-203. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1220327

- Kunishima S, Hamaguchi M, Saito H. Differential expression of wild-type and mutant NMMHC-IIA polypeptides in blood cells suggests cell-specific regulation mechanisms in MYH9 disorders. Blood. 2008;111:3015-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-116194

- Arrondel C, Vodovar N, Knebelmann B, et al. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:65-74. doi:10.1681/ASN.V13165

- Selleng K, Lubenow LE, Greinacher A, et al. Perioperative management of MYH9 hereditary macrothrombocytopenia (Fechtner syndrome). Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:263-268. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00913.x

To the Editor:

MYH9-related disorder is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by macrothrombocytopenia and neutrophil inclusions secondary to defective myosin-9.1 We describe a case of lower leg hyperpigmentation secondary to hemosiderin deposition from MYH9-related disorder.

A 31-year-old woman with a history of MYH9-related disorder and mixed connective tissue disease presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with asymptomatic brown patches on the lower legs (Figure) of 10 years’ duration. She also had epistaxis, hearing loss, renal disease, and menorrhagia secondary to MYH9-related disorder. The patient had been started on hydroxychloroquine 2 years earlier by rheumatology for mixed connective tissue disorder. A biopsy was not performed, given the risk of bleeding from thrombocytopenia. Ammonium lactate lotion was recommended for the leg patches. No further interventions were undertaken. At 6-month follow-up, hyperpigmentation on the lower legs was stable. The patient expressed no desire for cosmetic intervention.

Prior to discovery of a common gene, MYH9-related disorder was classified as 4 overlapping syndromes: May-Hegglin anomaly, Epstein syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Sebastian syndrome.2 More than 30 MYH9 mutations have been identified, all of which encode for myosin-9, a subunit of myosin IIA,1,3 that is a nonmuscle myosin needed for cell movement, shape, and cytokinesis. Although most cells use myosin IIA to IIC, certain cells, such as platelets and neutrophils, use myosin IIA exclusively.

In neutrophils of patients with MYH9-related disorder, nonfunctional myosin-9 clumps to form hallmark inclusion bodies, which are seen on the peripheral blood smear. Macrothrombocytopenia, another hallmark of MYH9-related disorder, also can be seen on the peripheral smear of all affected patients. Approximately 30%of patients develop clinical manifestations of the disorder (eg, bleeding, renal failure, hearing loss, presenile cataracts). Bleeding tendency usually is mild; epistaxis and menorrhagia are the most common hematologic manifestations.4

We attribute the lower leg hyperpigmentation in our patient to a severe phenotype of MYH9-related disorder. In addition to hyperpigmentation, our patient had menorrhagia requiring treatment with tranexamic acid, renal failure, and hearing loss, further pointing to a more severe phenotype. Furthermore, it is likely that our patient’s hyperpigmentation was made worse by hydroxychloroquine and a coexisting diagnosis of mixed connective tissue disease, which led to a propensity for increased vessel fragility in the setting of thrombocytopenia.

The workup of suspected MYH9-related disorder includes exclusion of iron-deficiency anemia, which can increase bleeding in patients with the disorder. The presence of small red blood cells (RBCs) in microcytic anemia and large platelets of MYH9-related disorder can lead to a situation in which platelets travel near the center of the lumen of blood vessels, while RBCs travel to the periphery. This decrease in the platelet-endothelium interaction increases the risk for bleeding. Our patient’s hemoglobin level was within reference range, without evidence of iron-deficiency anemia. Correction of iron-deficiency anemia, if applicable, can prevent bleeding brought on by the mechanism of decreased platelet-endothelium interaction and avoid unnecessary antiplatelet medication because of misdiagnosis based on an erroneous platelet count.

The workup of MYH9-related disorder also should include audiography, ophthalmologic examination, and renal function testing for hearing loss, cataracts, and renal disease, respectively. Referral to genetics also may be warranted.

It also is of clinical interest that automated cell counters may underestimate the count of abnormally large platelets in MYH9-related disorder, counting them as RBCs or white blood cells. The platelet count in MYH9-related disorder may be underestimated by 4-fold or greater.4-7

Treatment of leg hyperpigmentation can prove challenging, given the location of dermal hemosiderin. Topical therapy likely is ineffective. Lasers and intense pulsed light therapy are treatment modalities to consider for the hyperpigmentation of MYH9-related disorder. There have been reports of improved cosmesis in dermal hemosiderin depositional disorders, such as venous stasis.4 Our patient was given ammonium lactate lotion to thicken collagen, possibly preventing future bleeding episodes.

To the Editor:

MYH9-related disorder is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by macrothrombocytopenia and neutrophil inclusions secondary to defective myosin-9.1 We describe a case of lower leg hyperpigmentation secondary to hemosiderin deposition from MYH9-related disorder.

A 31-year-old woman with a history of MYH9-related disorder and mixed connective tissue disease presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with asymptomatic brown patches on the lower legs (Figure) of 10 years’ duration. She also had epistaxis, hearing loss, renal disease, and menorrhagia secondary to MYH9-related disorder. The patient had been started on hydroxychloroquine 2 years earlier by rheumatology for mixed connective tissue disorder. A biopsy was not performed, given the risk of bleeding from thrombocytopenia. Ammonium lactate lotion was recommended for the leg patches. No further interventions were undertaken. At 6-month follow-up, hyperpigmentation on the lower legs was stable. The patient expressed no desire for cosmetic intervention.

Prior to discovery of a common gene, MYH9-related disorder was classified as 4 overlapping syndromes: May-Hegglin anomaly, Epstein syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Sebastian syndrome.2 More than 30 MYH9 mutations have been identified, all of which encode for myosin-9, a subunit of myosin IIA,1,3 that is a nonmuscle myosin needed for cell movement, shape, and cytokinesis. Although most cells use myosin IIA to IIC, certain cells, such as platelets and neutrophils, use myosin IIA exclusively.

In neutrophils of patients with MYH9-related disorder, nonfunctional myosin-9 clumps to form hallmark inclusion bodies, which are seen on the peripheral blood smear. Macrothrombocytopenia, another hallmark of MYH9-related disorder, also can be seen on the peripheral smear of all affected patients. Approximately 30%of patients develop clinical manifestations of the disorder (eg, bleeding, renal failure, hearing loss, presenile cataracts). Bleeding tendency usually is mild; epistaxis and menorrhagia are the most common hematologic manifestations.4

We attribute the lower leg hyperpigmentation in our patient to a severe phenotype of MYH9-related disorder. In addition to hyperpigmentation, our patient had menorrhagia requiring treatment with tranexamic acid, renal failure, and hearing loss, further pointing to a more severe phenotype. Furthermore, it is likely that our patient’s hyperpigmentation was made worse by hydroxychloroquine and a coexisting diagnosis of mixed connective tissue disease, which led to a propensity for increased vessel fragility in the setting of thrombocytopenia.

The workup of suspected MYH9-related disorder includes exclusion of iron-deficiency anemia, which can increase bleeding in patients with the disorder. The presence of small red blood cells (RBCs) in microcytic anemia and large platelets of MYH9-related disorder can lead to a situation in which platelets travel near the center of the lumen of blood vessels, while RBCs travel to the periphery. This decrease in the platelet-endothelium interaction increases the risk for bleeding. Our patient’s hemoglobin level was within reference range, without evidence of iron-deficiency anemia. Correction of iron-deficiency anemia, if applicable, can prevent bleeding brought on by the mechanism of decreased platelet-endothelium interaction and avoid unnecessary antiplatelet medication because of misdiagnosis based on an erroneous platelet count.

The workup of MYH9-related disorder also should include audiography, ophthalmologic examination, and renal function testing for hearing loss, cataracts, and renal disease, respectively. Referral to genetics also may be warranted.

It also is of clinical interest that automated cell counters may underestimate the count of abnormally large platelets in MYH9-related disorder, counting them as RBCs or white blood cells. The platelet count in MYH9-related disorder may be underestimated by 4-fold or greater.4-7

Treatment of leg hyperpigmentation can prove challenging, given the location of dermal hemosiderin. Topical therapy likely is ineffective. Lasers and intense pulsed light therapy are treatment modalities to consider for the hyperpigmentation of MYH9-related disorder. There have been reports of improved cosmesis in dermal hemosiderin depositional disorders, such as venous stasis.4 Our patient was given ammonium lactate lotion to thicken collagen, possibly preventing future bleeding episodes.

- Pecci A, Canobbio I, Balduini A, et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hematological abnormalities of patients with MYH9 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3169-3178. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi344

- Seri M, Pecci A, Di Bari F, et al. MYH9-related disease: May-Hegglin anomaly, Sebastian syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Epstein syndrome are not distinct entities but represent a variable expression of a single illness. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:203-215. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000076006.64510.5c

- Medline Plus. MYH9-related disorder. National Library of Medicine website. Updated August 18, 2020. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/myh9-related-disorder#diagnosis

- Althaus K, Greinachar A. MYH9-related platelet disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:189-203. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1220327

- Kunishima S, Hamaguchi M, Saito H. Differential expression of wild-type and mutant NMMHC-IIA polypeptides in blood cells suggests cell-specific regulation mechanisms in MYH9 disorders. Blood. 2008;111:3015-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-116194

- Arrondel C, Vodovar N, Knebelmann B, et al. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:65-74. doi:10.1681/ASN.V13165

- Selleng K, Lubenow LE, Greinacher A, et al. Perioperative management of MYH9 hereditary macrothrombocytopenia (Fechtner syndrome). Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:263-268. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00913.x

- Pecci A, Canobbio I, Balduini A, et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hematological abnormalities of patients with MYH9 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3169-3178. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi344

- Seri M, Pecci A, Di Bari F, et al. MYH9-related disease: May-Hegglin anomaly, Sebastian syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Epstein syndrome are not distinct entities but represent a variable expression of a single illness. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:203-215. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000076006.64510.5c

- Medline Plus. MYH9-related disorder. National Library of Medicine website. Updated August 18, 2020. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/myh9-related-disorder#diagnosis

- Althaus K, Greinachar A. MYH9-related platelet disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:189-203. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1220327

- Kunishima S, Hamaguchi M, Saito H. Differential expression of wild-type and mutant NMMHC-IIA polypeptides in blood cells suggests cell-specific regulation mechanisms in MYH9 disorders. Blood. 2008;111:3015-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-116194

- Arrondel C, Vodovar N, Knebelmann B, et al. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:65-74. doi:10.1681/ASN.V13165

- Selleng K, Lubenow LE, Greinacher A, et al. Perioperative management of MYH9 hereditary macrothrombocytopenia (Fechtner syndrome). Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:263-268. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00913.x

Practice Points

- MYH9-related disorder is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by macrothrombocytopenia and neutrophil inclusions secondary to defective myosin-9.

- Leg hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to hemosiderin deposition from MYH9-related disorder.

- The workup of suspected MYH9-related disorder includes exclusion of iron-deficiency anemia, which can increase bleeding in patients with the disorder.

- Lasers and intense pulsed light therapy are modalities to consider for the hyperpigmentation of MYH9- related disorder.

Scleral Plaques in Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis

To the Editor:

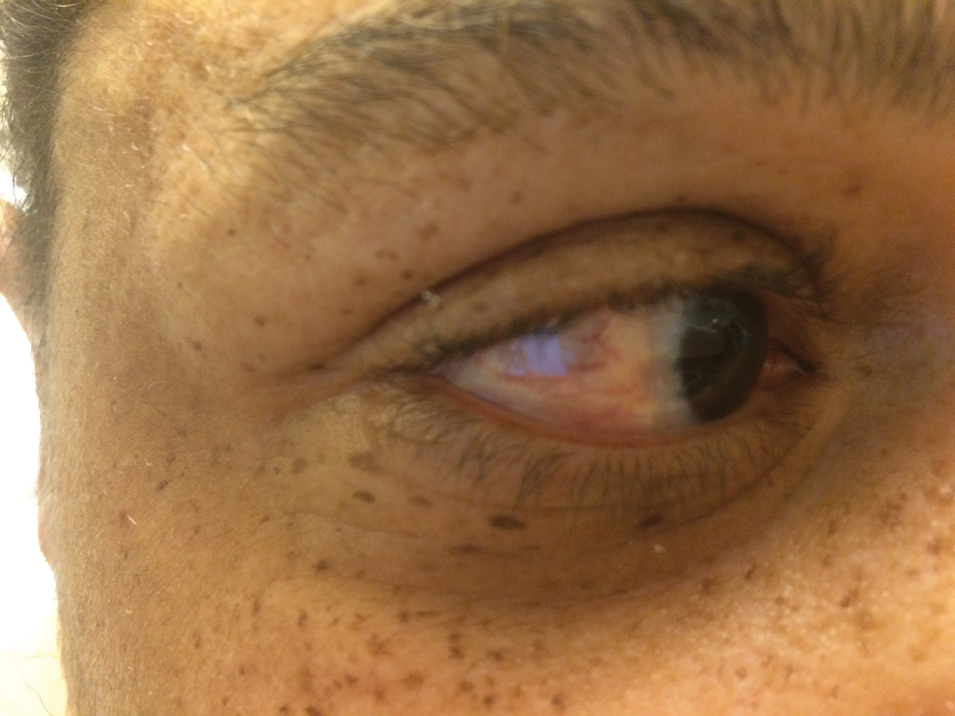

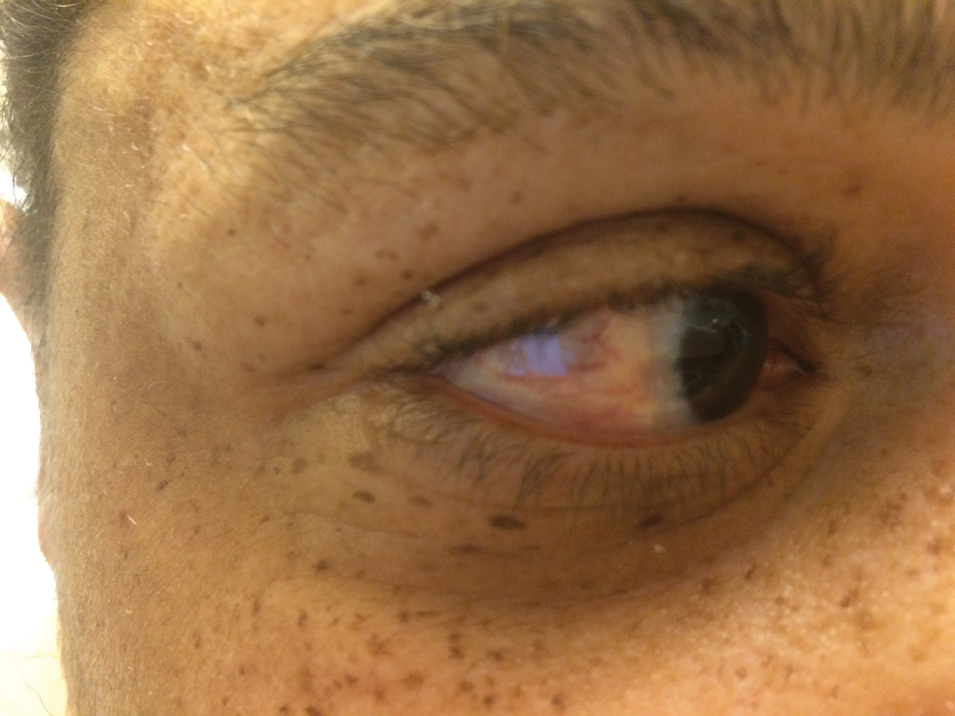

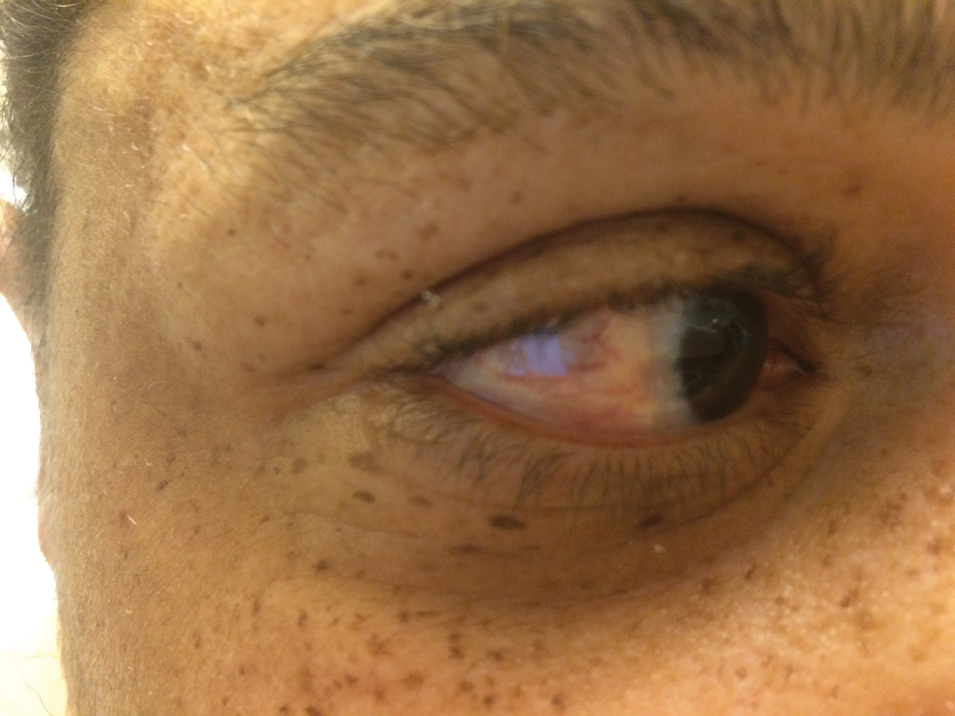

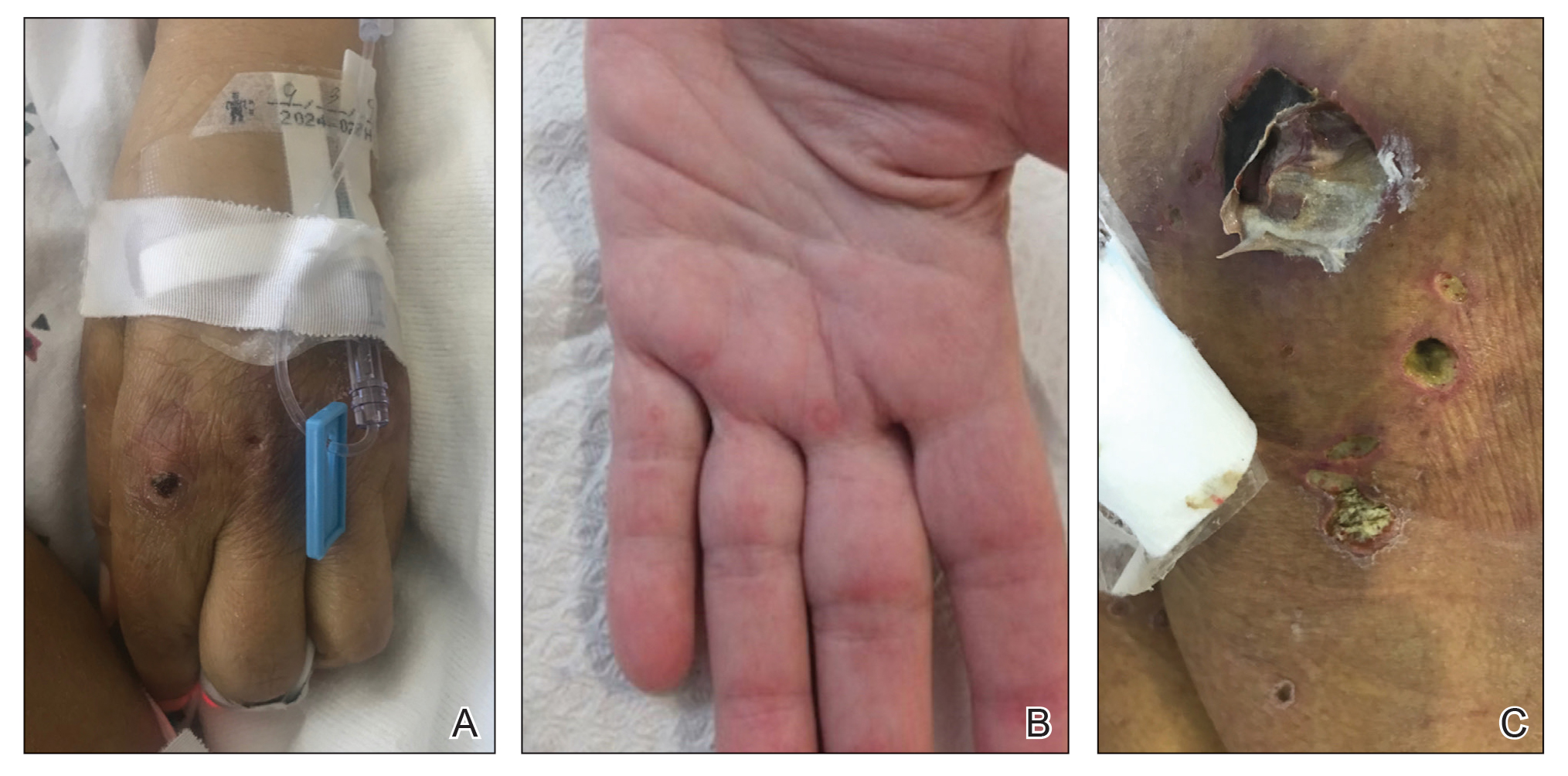

A 44-year-old man with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) complicated by lupus nephritis, end-stage renal disease, and antiphospholipid syndrome was evaluated for progressive skin tightening over the last 3 years, predominantly on the hands but also involving the feet, legs, and arms. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to hypopigmented, bound-down, indurated, fissured plaques over the distal upper and lower extremities, most prominent over the hands (Figure 1). Yellow plaques appeared on the lateral sclera of both eyes (Figure 2). A diagnosis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) was supported by typical findings on punch biopsy, including a proliferation of dermal fibroblasts with thickened collagen bundles and mucin deposition.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, also known as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, is characterized by fibrotic plaques and nodules that tend to be bilateral.1 The chronic course of this disease often is accompanied by flexion contractures. Yellow scleral plaques caused by calcium phosphate deposition are present in up to 75% of cases and are more specific to a diagnosis of NSF in patients younger than 45 years.1,2 A strong association exists between NSF and gadolinium contrast agents in patients with acute renal failure; our patient later confirmed multiple gadolinium exposures years prior. Deposits of gadolinium have even been found in NSF skin lesions.2

- Stone JH. A Clinician’s Pearls & Myths in Rheumatology. Springer London; 2009.

- Barker-Griffith A, Goldberg J, Abraham JL. Ocular pathologic features and gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:661-663.

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old man with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) complicated by lupus nephritis, end-stage renal disease, and antiphospholipid syndrome was evaluated for progressive skin tightening over the last 3 years, predominantly on the hands but also involving the feet, legs, and arms. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to hypopigmented, bound-down, indurated, fissured plaques over the distal upper and lower extremities, most prominent over the hands (Figure 1). Yellow plaques appeared on the lateral sclera of both eyes (Figure 2). A diagnosis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) was supported by typical findings on punch biopsy, including a proliferation of dermal fibroblasts with thickened collagen bundles and mucin deposition.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, also known as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, is characterized by fibrotic plaques and nodules that tend to be bilateral.1 The chronic course of this disease often is accompanied by flexion contractures. Yellow scleral plaques caused by calcium phosphate deposition are present in up to 75% of cases and are more specific to a diagnosis of NSF in patients younger than 45 years.1,2 A strong association exists between NSF and gadolinium contrast agents in patients with acute renal failure; our patient later confirmed multiple gadolinium exposures years prior. Deposits of gadolinium have even been found in NSF skin lesions.2

To the Editor:

A 44-year-old man with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) complicated by lupus nephritis, end-stage renal disease, and antiphospholipid syndrome was evaluated for progressive skin tightening over the last 3 years, predominantly on the hands but also involving the feet, legs, and arms. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to hypopigmented, bound-down, indurated, fissured plaques over the distal upper and lower extremities, most prominent over the hands (Figure 1). Yellow plaques appeared on the lateral sclera of both eyes (Figure 2). A diagnosis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) was supported by typical findings on punch biopsy, including a proliferation of dermal fibroblasts with thickened collagen bundles and mucin deposition.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, also known as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, is characterized by fibrotic plaques and nodules that tend to be bilateral.1 The chronic course of this disease often is accompanied by flexion contractures. Yellow scleral plaques caused by calcium phosphate deposition are present in up to 75% of cases and are more specific to a diagnosis of NSF in patients younger than 45 years.1,2 A strong association exists between NSF and gadolinium contrast agents in patients with acute renal failure; our patient later confirmed multiple gadolinium exposures years prior. Deposits of gadolinium have even been found in NSF skin lesions.2

- Stone JH. A Clinician’s Pearls & Myths in Rheumatology. Springer London; 2009.

- Barker-Griffith A, Goldberg J, Abraham JL. Ocular pathologic features and gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:661-663.

- Stone JH. A Clinician’s Pearls & Myths in Rheumatology. Springer London; 2009.

- Barker-Griffith A, Goldberg J, Abraham JL. Ocular pathologic features and gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:661-663.

Practice Points

- It is important to examine the eyes in a patient with sclerotic skin changes on physical examination.

- The presence of yellow scleral plaques strongly is associated with a diagnosis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.

Febrile Ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann Disease: A Rare Form of Pityriasis Lichenoides et Varioliformis Acuta

To the Editor:

Pityriasis lichenoides is a papulosquamous dermatologic disorder that is characterized by recurrent papules.1 There is a spectrum of disease in pityriasis lichenoides that includes pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) at one end and pityriasis lichenoides chronica at the other. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is more common in younger individuals and is characterized by erythematous papules that often crust; these lesions resolve over weeks. The lesions of pityriasis lichenoides chronica are characteristically scaly, pink to red-brown papules that tend to resolve over months.1

Histologically, PLEVA exhibits parakeratosis, interface dermatitis, and a wedge-shaped infiltrate.1 Necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes also are common features. Additionally, monoclonal T cells may be present in the infiltrate.1

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD) is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is characterized by ulceronecrotic lesions, fever, and systemic symptoms.2 Herein, we present a case of FUMHD.

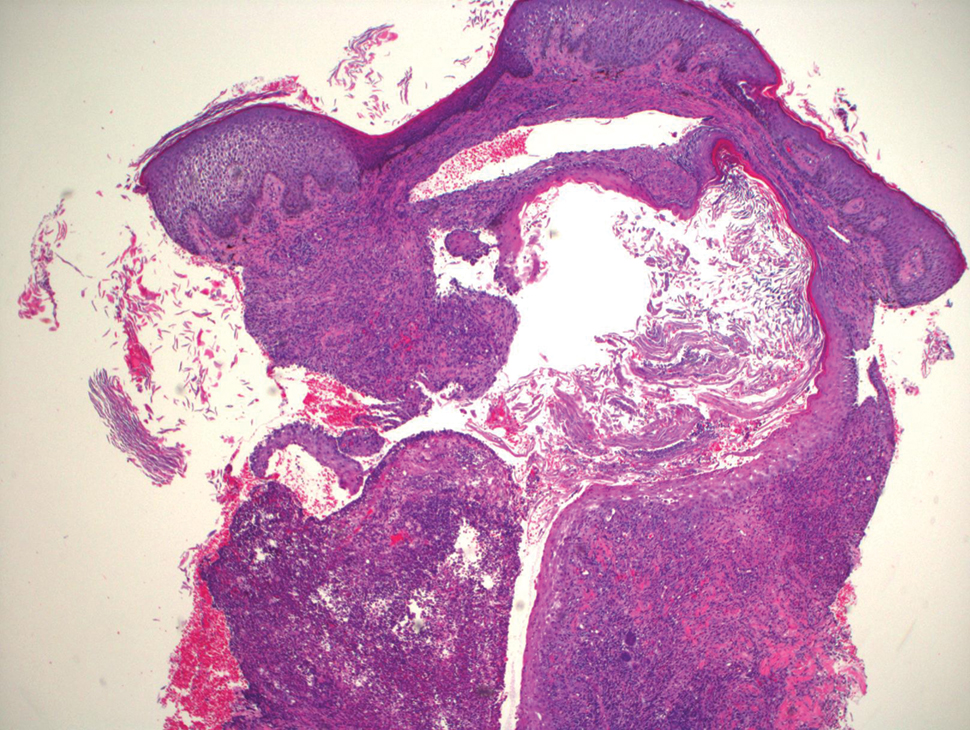

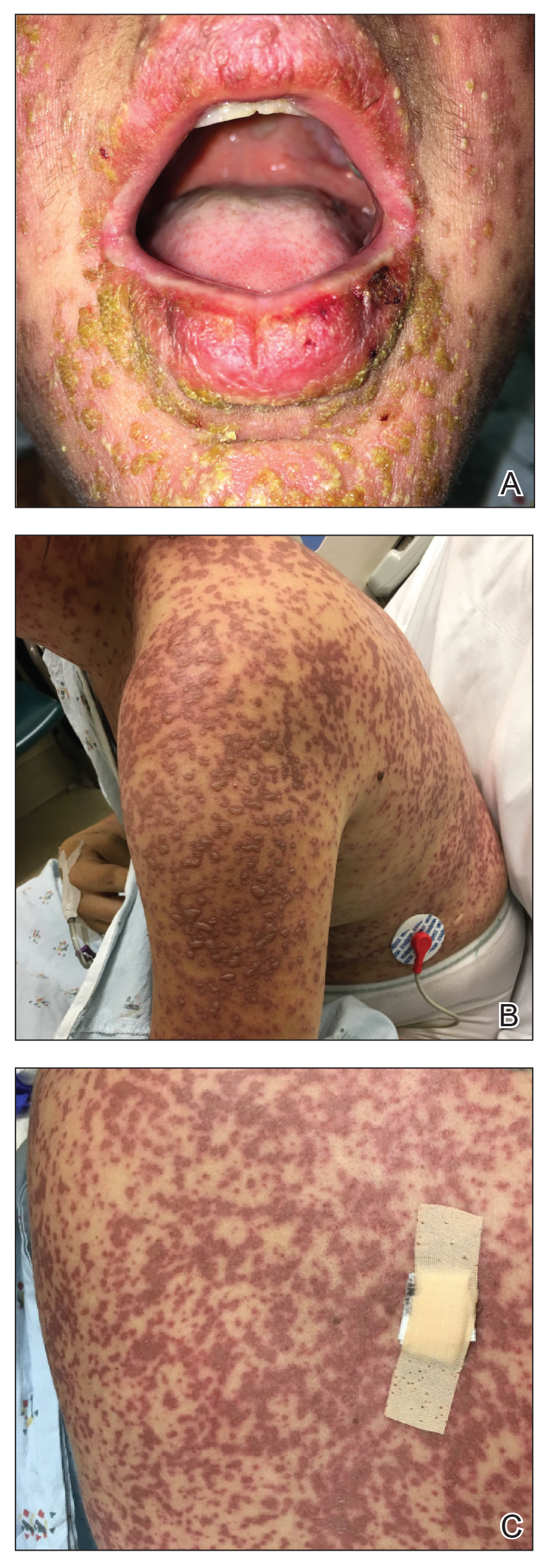

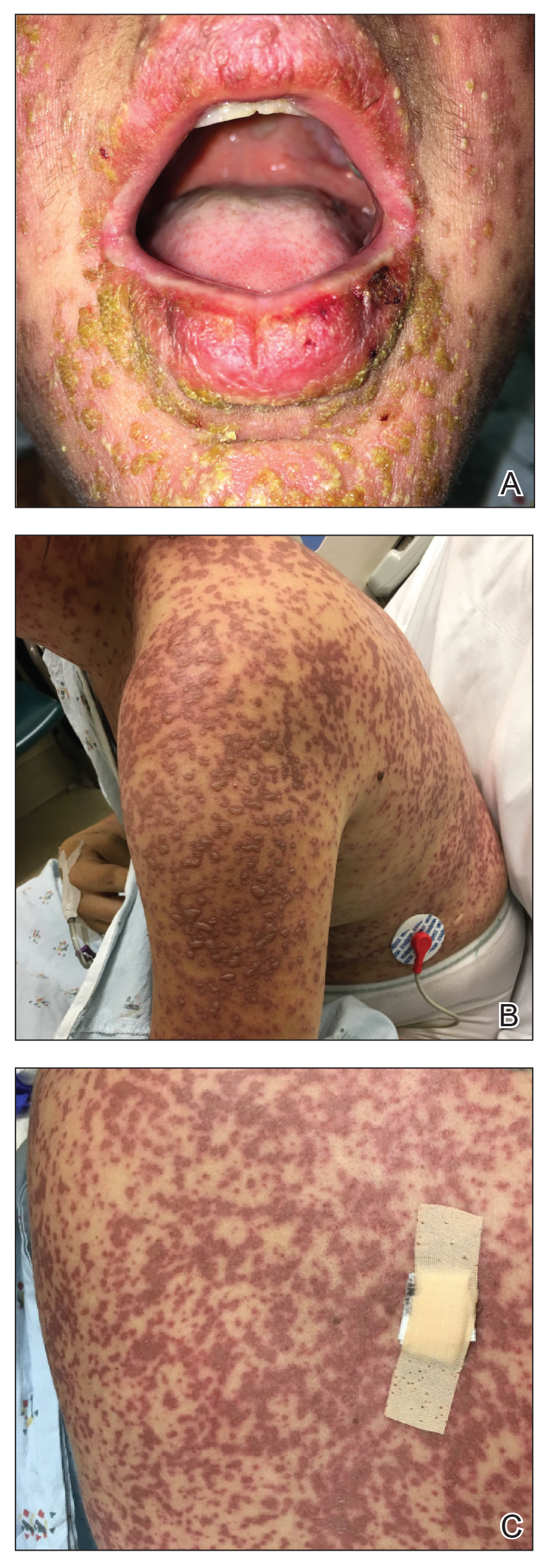

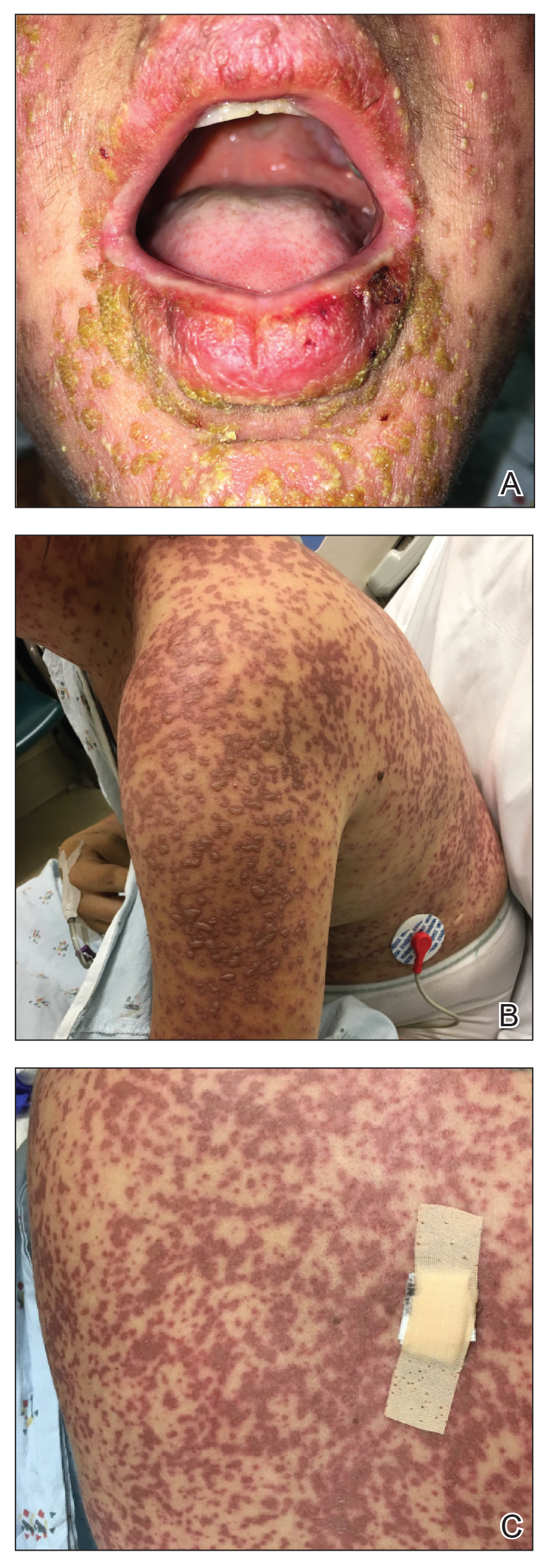

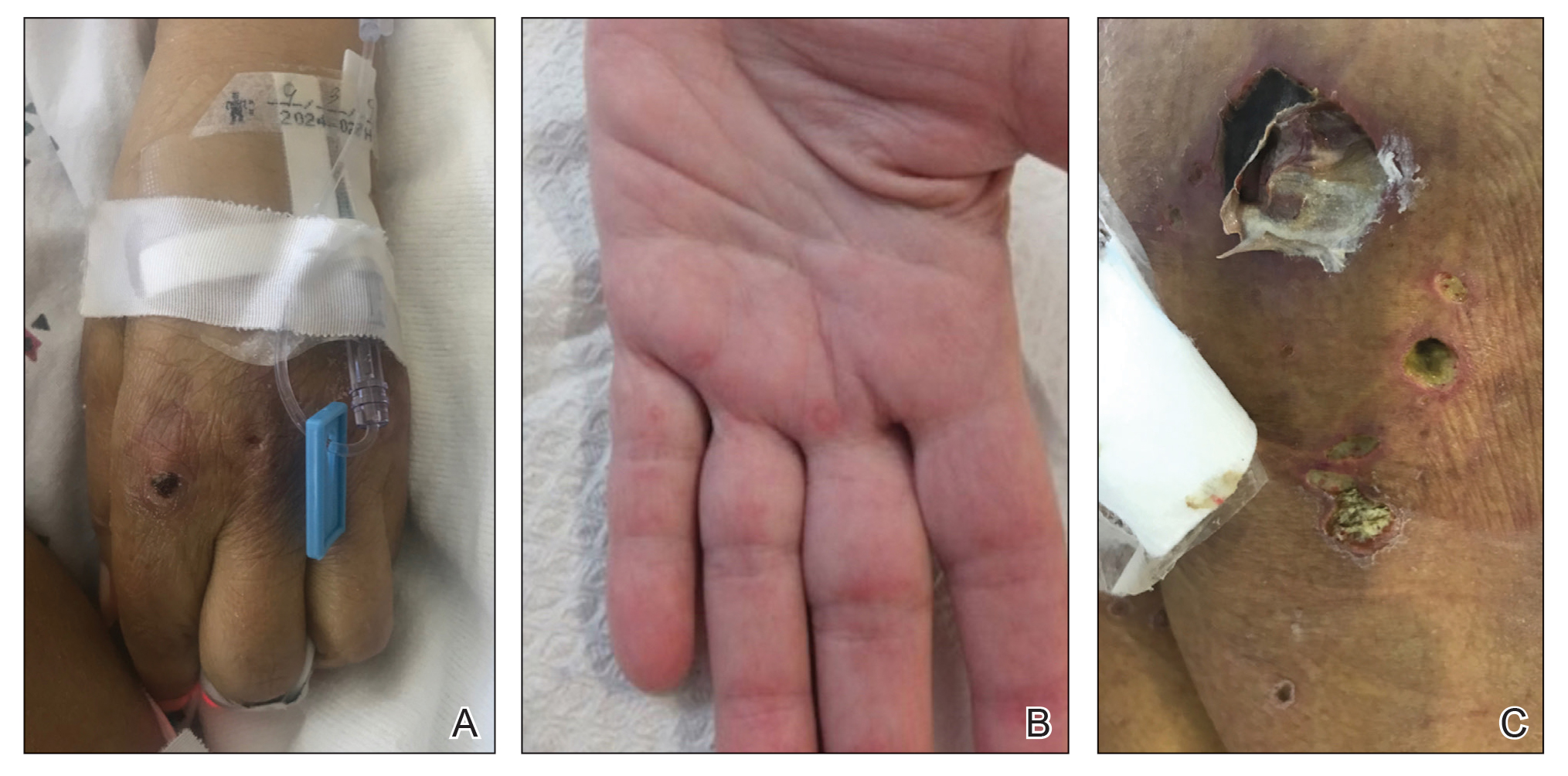

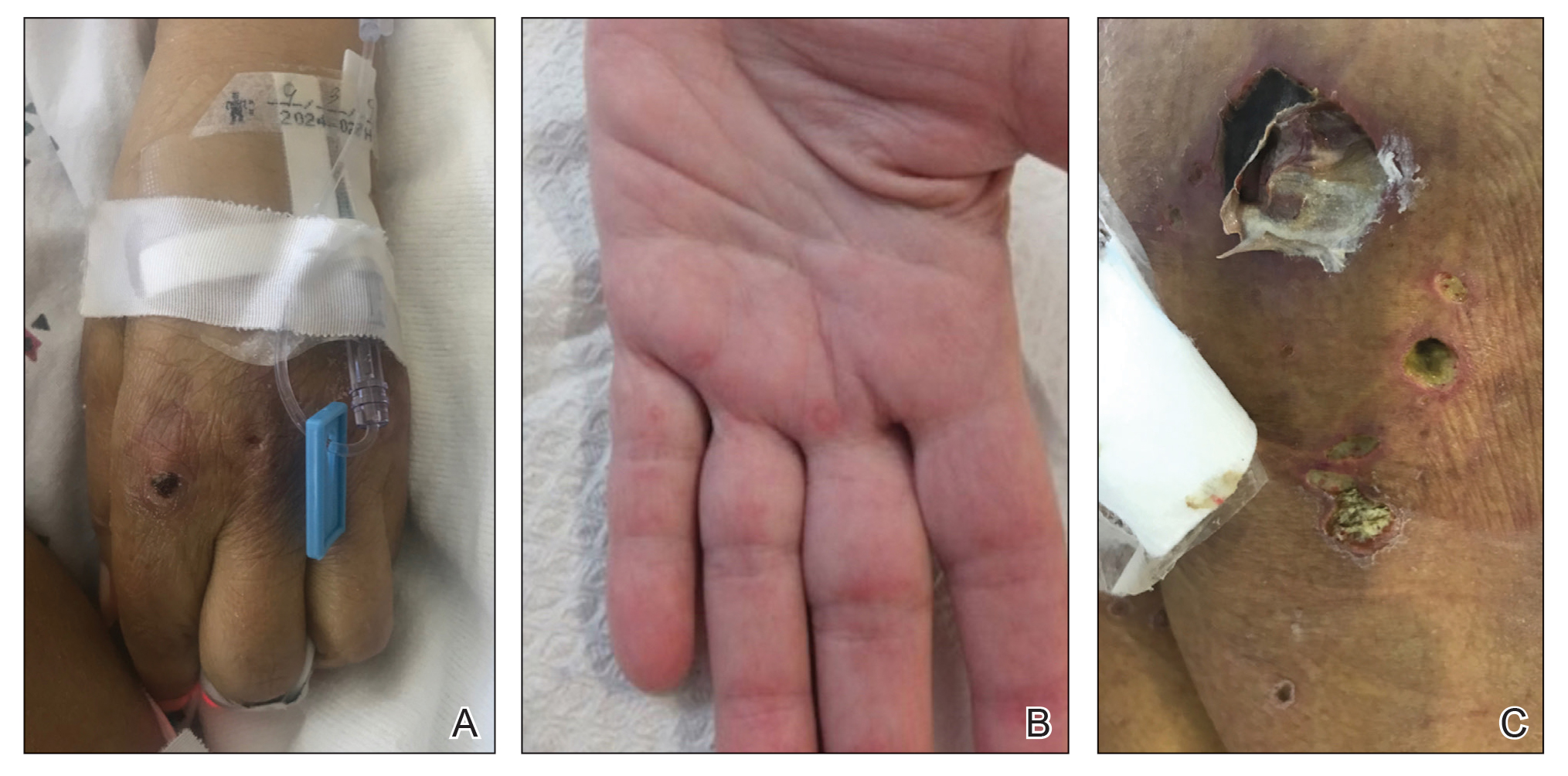

A 57-year-old man presented with an eruption of painful lesions involving the face, trunk, arms, legs, and genitalia of 1 month’s duration. The patient denied oral and ocular involvement. He had soreness and swelling of the arms and legs. A prior 12-day course of prednisone prescribed by a community dermatologist failed to improve the rash. A biopsy performed by a community dermatologist was nondiagnostic. The patient denied fever but did report chills. He had no preceding illness and was not taking new medications. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and normotensive with innumerable deep-seated pustules and crusted ulcerations on the face, palms, soles, trunk, extremities, and penis (Figures 1 and 2). There was a background morbilliform eruption on the trunk. The ocular and oral mucosae were spared. The upper and lower extremities had pitting edema.

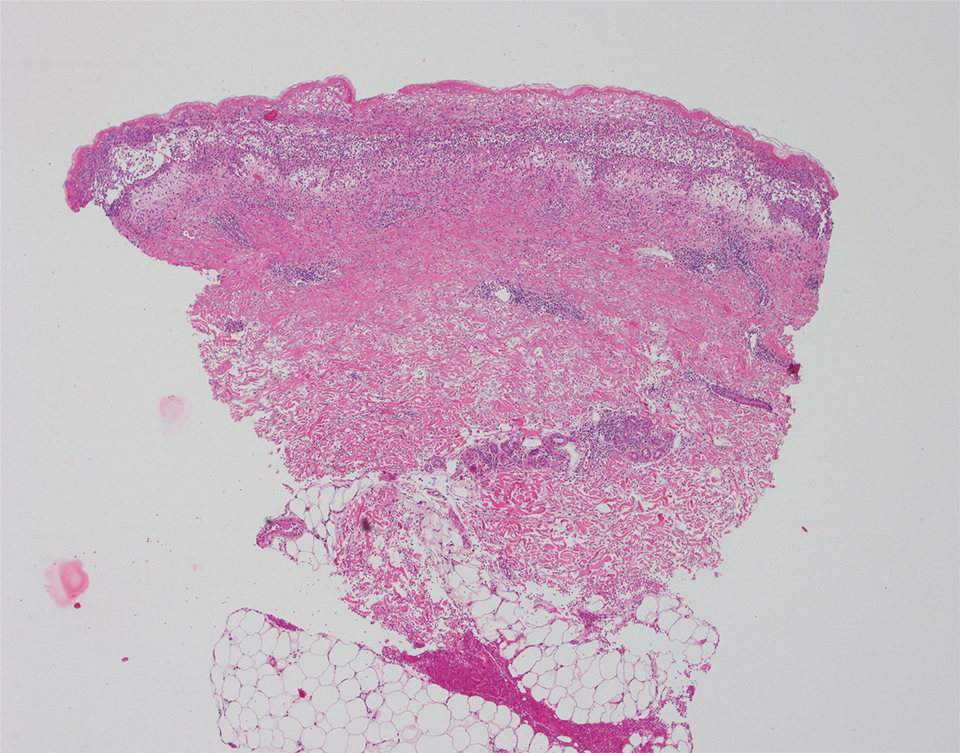

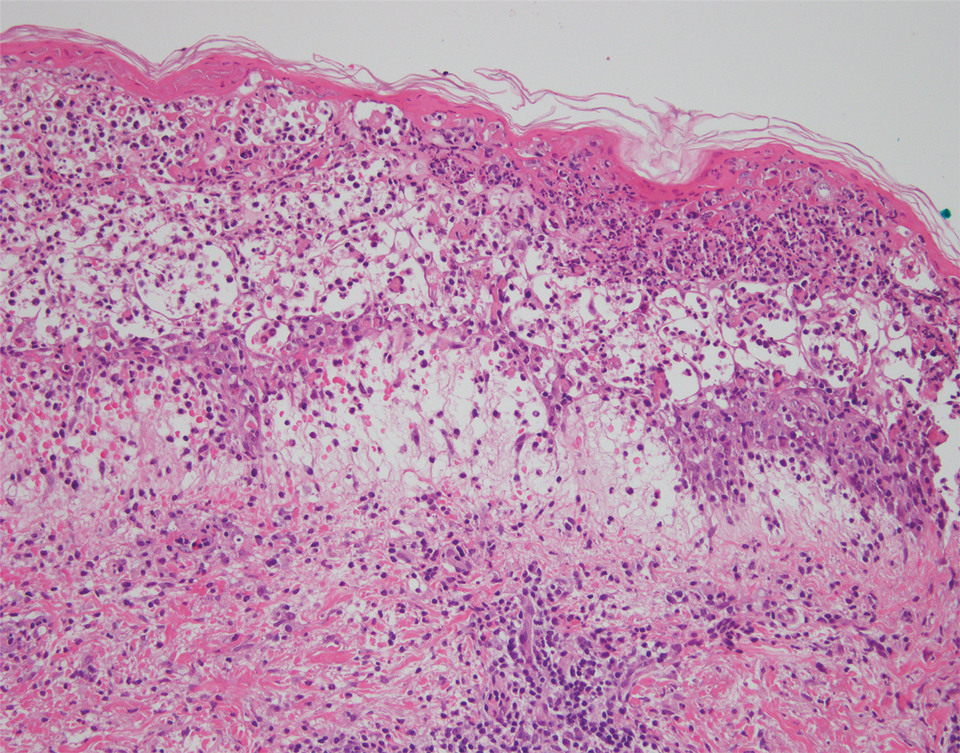

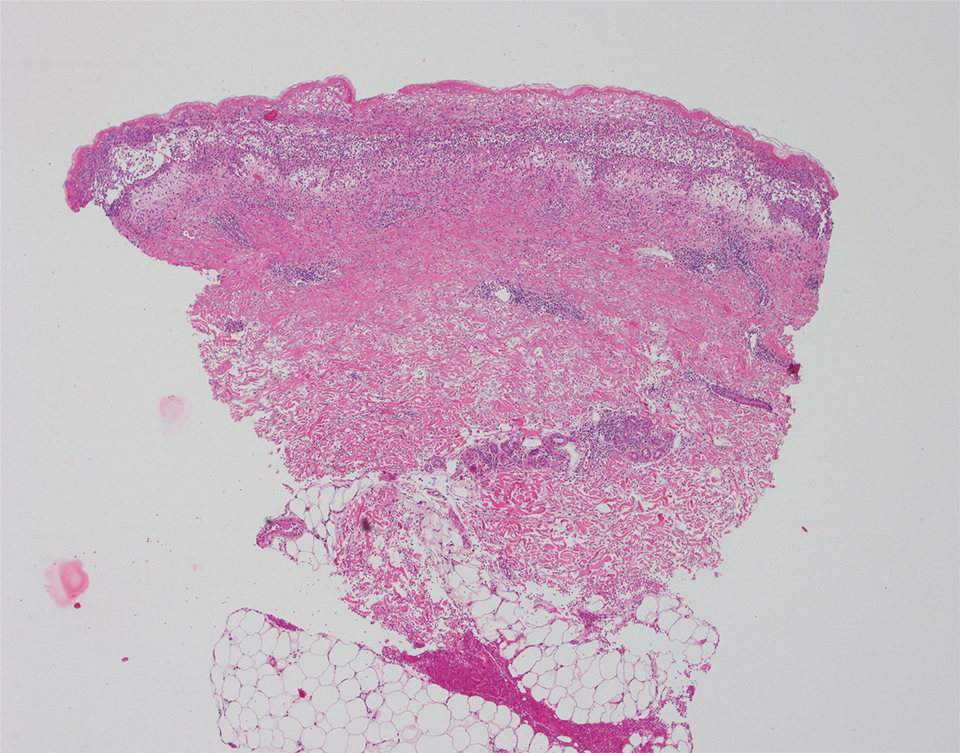

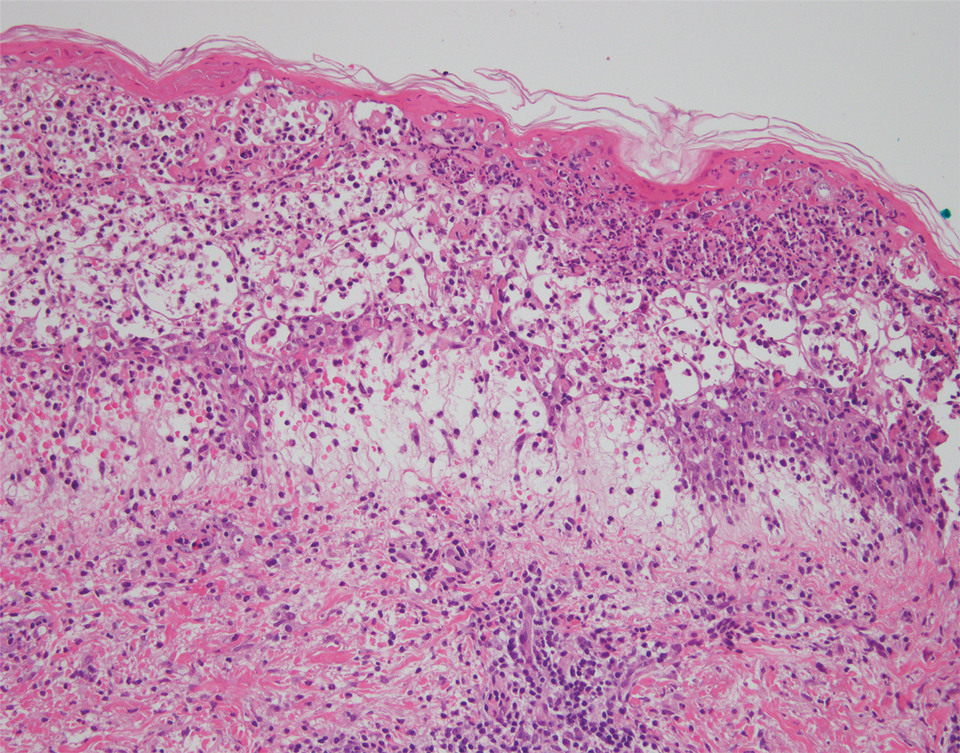

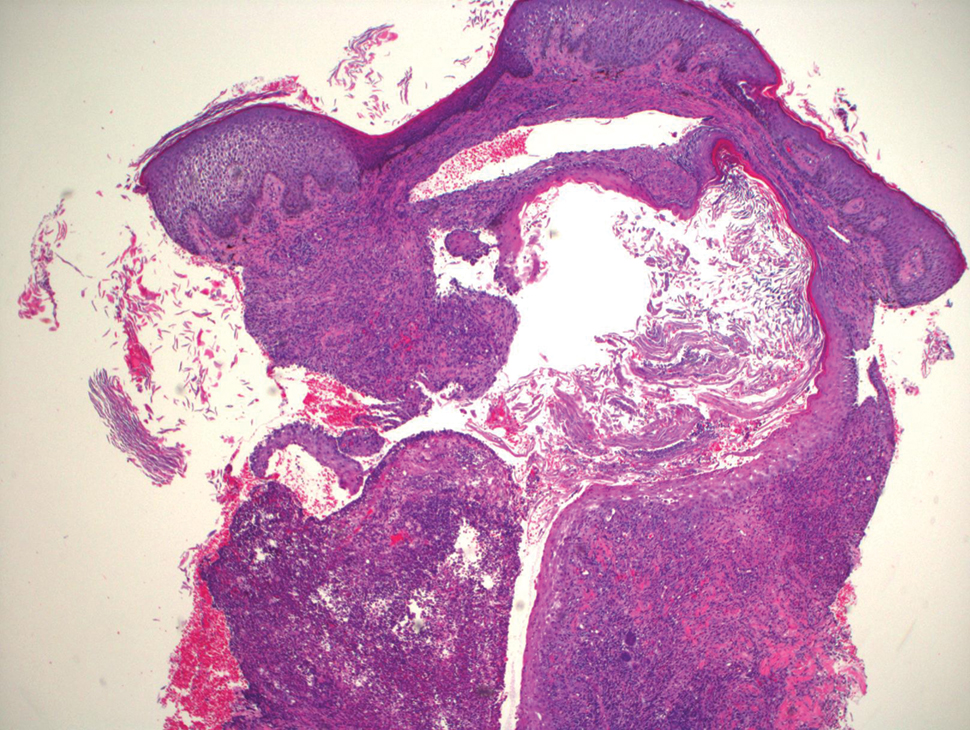

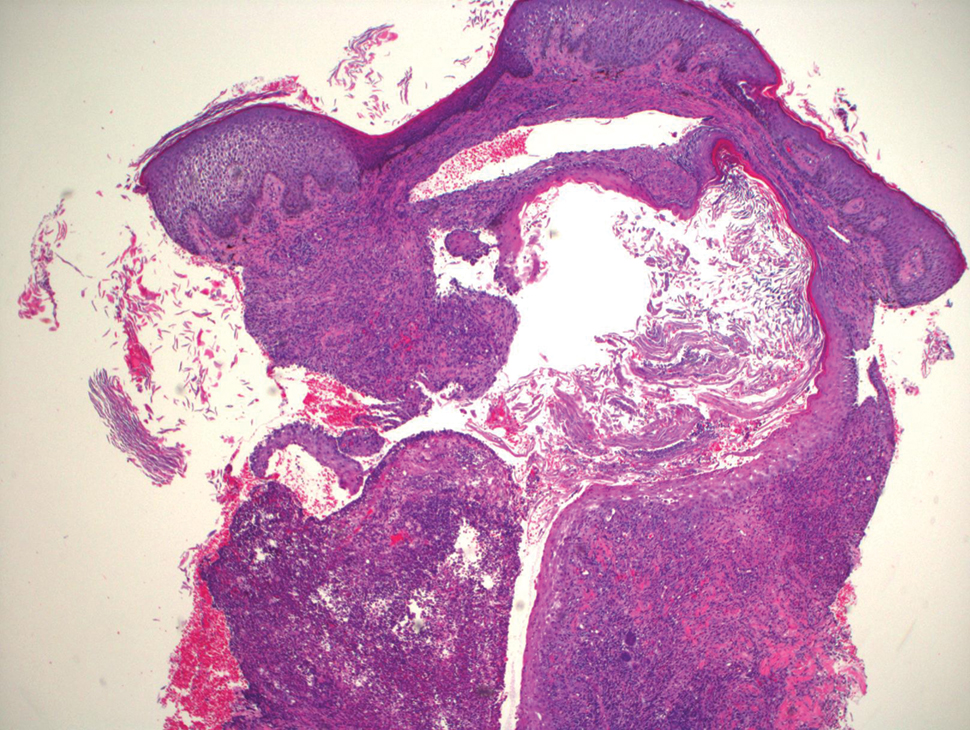

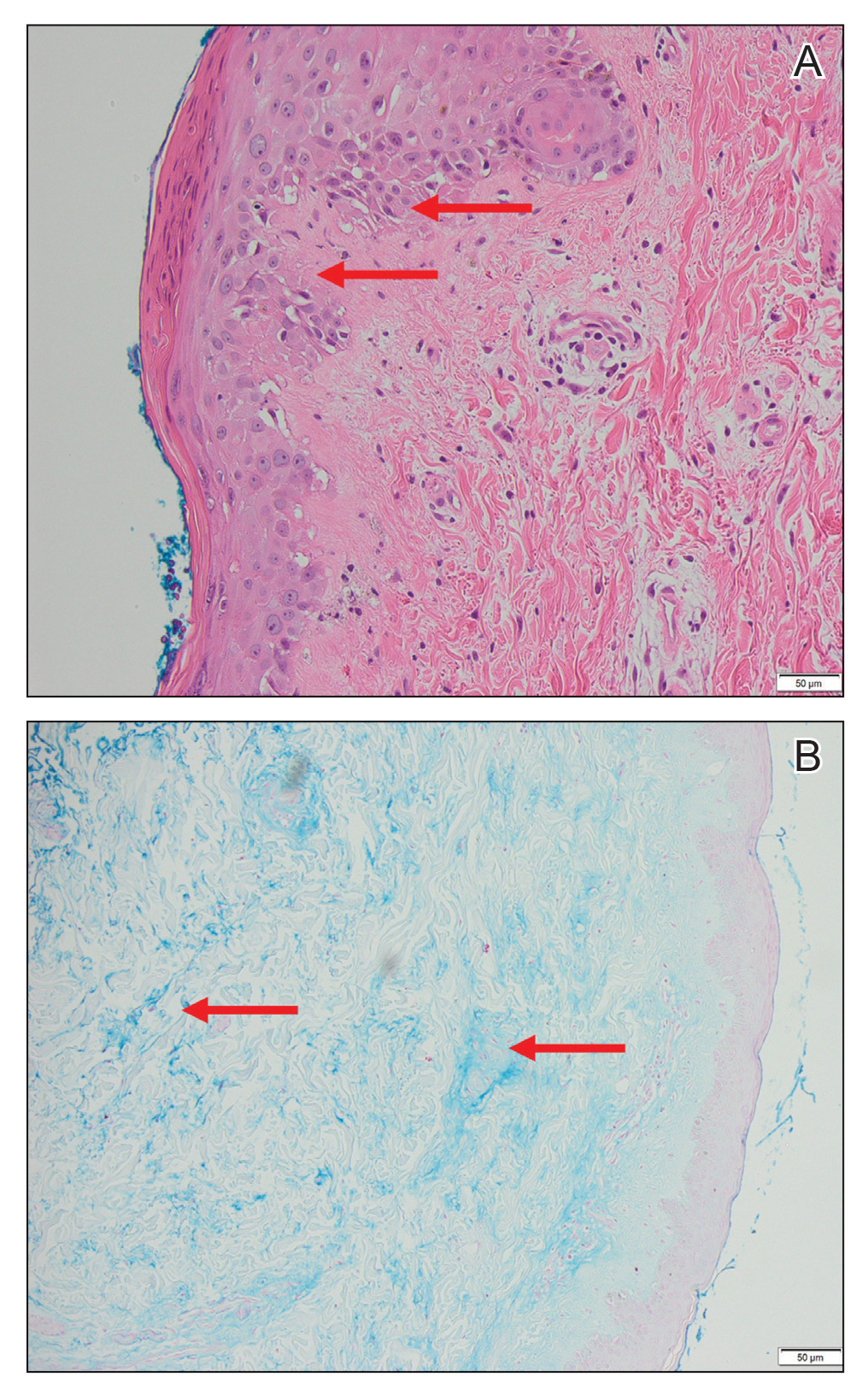

The patient’s alanine aminotransaminase and aspartate aminotransaminase levels were elevated at 55 and 51 U/L, respectively. His white blood cell count was within reference range; however, there was an elevated absolute neutrophil count (8.7×103/μL). No eosinophilia was noted. Laboratory evaluation showed a positive antimitochondrial antibody, and magnetic resonance imaging showed evidence of steatohepatitis. Punch biopsies from both the morbilliform eruption and a deep-seated pustule showed epidermal necrosis, parakeratosis, necrotic keratinocytes, and a lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes at the dermoepidermal interface. In the dermis, there was a wedge-shaped superficial and deep, perivascular infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes (Figures 3 and 4). Tissue Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus immunostains were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed colloid bodies, as can be seen in lichenoid dermatitis.

At the next clinic visit, the patient reported a fever of 39.4 °C. After reviewing the patient’s histopathology and clinical picture, along with the presence of fever, a final diagnosis of FUMHD was made. The patient was started on an oral regimen of prednisone 80 mg once daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and methotrexate 15 mg weekly. Unna boots (specialized compression wraps) with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% were placed weekly until the leg edema and ulcerations healed. He was maintained on methotrexate 15 mg weekly and 5 to 10 mg of prednisone once daily. The patient demonstrated residual scarring, with only rare new papulonodules that did not ulcerate when attempts were made to taper his medications. He was followed for nearly 3 years, with a recurrence of symptoms 2 years and 3 months after initial presentation to the academic dermatology clinic.

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA that can present with the rapid appearance of necrotic skin lesions, fever, and systemic manifestations, including pulmonary, gastrointestinal, central nervous system, cardiac, hematologic, and rheumatologic symptoms.2-4 The evolution from PLEVA to FUMHD ranges from days to weeks, and patientsrarely can have an initial presentation of FUMHD.2 The duration of illness has been reported to be 1 to 24 months5; however, the length of illness still remains unclear, as many studies of FUMHD are case reports with limited follow-up. Our patient had a disease duration of at least 27 months. The lesions of FUMHD usually are generalized with flexural prominence, and mucosal involvement occurs in approximately one-quarter of cases. Hypertrophic scarring may be seen after the ulcerated lesions heal.2 The incidence of FUMHD is higher in men than in women, and it is more common in younger individuals.2,6 There have been reported fatalities associated with FUMHD, mostly in adults.2,4

The clinical differential diagnosis for PLEVA includes disseminated herpes zoster, varicella-zoster virus or coxsackievirus infections, lymphomatoid papulosis, angiodestructive lymphoma such as extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, drug eruption, arthropod bite, erythema multiforme, ecthyma, ecthyma gangrenosum, necrotic folliculitis, and cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. To differentiate between these diagnoses and PLEVA or FUMHD, it is important to take a strong clinical history. For example, for varicella-zoster virus and coxsackievirus infections, exposure history to the viruses and vaccination history for varicella-zoster virus can help elucidate the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy can help differentiate between these entities and PLEVA or FUMHD. The histopathology of a nonulcerated lesion of FUMHD shows parakeratosis, spongiosis, and lymphocyte exocytosis, as well as lymphocytic vasculitis—findings commonly seen in PLEVA. With the ulceronecrotic lesions of FUMHD, epidermal necrosis and ulceration can be seen microscopically.2 Although skin biopsy is not absolutely necessary for making the diagnosis of PLEVA, it can be helpful.3 However, given the dramatic and extreme clinical impression with an extensive differential diagnosis that includes disorders ranging from infectious to neoplastic, biopsy of FUMHD with clinicopathologic correlation often is required.

It is important to avoid biopsying ulcerated lesions of FUMHD, as the histopathologic findings are more likely to be nonspecific. Additionally, nonspecific features often are seen with immunohistochemistry; abnormal laboratory testing may be seen in FUMHD, but there is no specific test to diagnose FUMHD.2 Finally, a predominantly CD8+ cell infiltrate was seen in 4 of 6 cases of FUMHD, with 2 cases showing a mixed infiltrate of CD8+ and CD4+ cells.5,7-10

Although no unified diagnostic criterion exists for FUMHD, Nofal et al2 proposed criteria comprised of constant features, which are found in every case of FUMHD and can confirm the diagnosis alone, and variable features to help ensure that cases of FUMHD are not missed. The constant features include fever, acute onset of generalized ulceronecrotic papules and plaques, a course that is rapid and progressive (without a tendency for spontaneous resolution), and histopathology that is consistent with PLEVA. The variable features include history of PLEVA, involvement of mucous membranes, and systemic involvement.2

No single unifying treatment modality for all cases of FUMHD has been described. Immunosuppressive drugs (eg, systemic steroids, methotrexate), antibiotics, antivirals, phototherapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, and dapsone have been tried in patients with FUMHD.2 Combination therapy with an oral medication such as erythromycin or methotrexate and psoralen plus UVA may be effective for FUMHD.3 Additionally, some authors believe that patients with FUMHD should be treated similar to burn victims with intensive supportive care.2

The etiology of PLEVA is unknown, but it is presumed to be associated with an effector cytotoxic T-cell response to either an infectious agent or a drug.11

Four cases of FUMHD with monoclonality have been reported,4,7,8 and some researchers propose that FUMHD may be a subset of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.7 However, 2 other cases of FUMHD did not show monoclonality of T cells,5,18 suggesting that FUMHD may represent an inflammatory disorder, rather than a lymphoproliferative process of T cells.18 Given the controversy surrounding the clonality of FUMHD, T-cell gene rearrangement studies were not performed in our case.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other papulosquamous disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:68-69.

- Nofal A, Assaf M, Alakad R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:729-738.

- Milligan A, Johnston GA. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease, Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 4th ed. Saunders; 2013:580-582.

- Miyamoto T, Takayama N, Kitada S, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:795-797.

- Meziane L, Caudron A, Dhaille F, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: treatment with infliximab and intravenous immunoglobulins and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:344-348.

- Robinson AB, Stein LD. Miscellaneous conditions associated with arthritis. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW III, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. W.B. Saunders Company; 2011:880.

- Cozzio A, Hafner J, Kempf W, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease with clonality: a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1014-1017.

- Tsianakas A, Hoeger PH. Transition of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta to febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is associated with elevated serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:794-799.

- Yanaba K, Ito M, Sasaki H, et al. A case of febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease requiring debridement of necrotic skin and epidermal autograft. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1249-1253.

- Lode HN, Döring P, Lauenstein P, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease following suspected hemorrhagic chickenpox infection in a 20-month-old boy. Infection. 2015;43:583-588.

- Tomasini D, Tomasini CF, Cerri A, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides: a cytotoxic T-cell-mediated skin disorder: evidence of human parvovirus B19 DNA in nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:531-538.

- Weiss LM, Wood GS, Ellisen LW, et al. Clonal T-cell populations in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (Mucha-Habermann disease). Am J Pathol. 1987;126:417-421.

- Dereure O, Levi E, Kadin ME. T-cell clonality in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a heteroduplex analysis of 20 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1483-1486.

- Weinberg JM, Kristal L, Chooback L, et al. The clonal nature of pityriasis lichenoides. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1063-1067.

- Fortson JS, Schroeter AL, Esterly NB. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (parapsoriasis en plaque): an association with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in young children. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1449-1453.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:958.

- Kim JE, Yun WJ, Mun SK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica: comparison of lesional T-cell subsets and investigation of viral associations. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:649-656.

- López-Estebaran´z JL, Vanaclocha F, Gil R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(5, pt 2):903-906.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis lichenoides is a papulosquamous dermatologic disorder that is characterized by recurrent papules.1 There is a spectrum of disease in pityriasis lichenoides that includes pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) at one end and pityriasis lichenoides chronica at the other. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is more common in younger individuals and is characterized by erythematous papules that often crust; these lesions resolve over weeks. The lesions of pityriasis lichenoides chronica are characteristically scaly, pink to red-brown papules that tend to resolve over months.1

Histologically, PLEVA exhibits parakeratosis, interface dermatitis, and a wedge-shaped infiltrate.1 Necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes also are common features. Additionally, monoclonal T cells may be present in the infiltrate.1

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD) is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is characterized by ulceronecrotic lesions, fever, and systemic symptoms.2 Herein, we present a case of FUMHD.

A 57-year-old man presented with an eruption of painful lesions involving the face, trunk, arms, legs, and genitalia of 1 month’s duration. The patient denied oral and ocular involvement. He had soreness and swelling of the arms and legs. A prior 12-day course of prednisone prescribed by a community dermatologist failed to improve the rash. A biopsy performed by a community dermatologist was nondiagnostic. The patient denied fever but did report chills. He had no preceding illness and was not taking new medications. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and normotensive with innumerable deep-seated pustules and crusted ulcerations on the face, palms, soles, trunk, extremities, and penis (Figures 1 and 2). There was a background morbilliform eruption on the trunk. The ocular and oral mucosae were spared. The upper and lower extremities had pitting edema.

The patient’s alanine aminotransaminase and aspartate aminotransaminase levels were elevated at 55 and 51 U/L, respectively. His white blood cell count was within reference range; however, there was an elevated absolute neutrophil count (8.7×103/μL). No eosinophilia was noted. Laboratory evaluation showed a positive antimitochondrial antibody, and magnetic resonance imaging showed evidence of steatohepatitis. Punch biopsies from both the morbilliform eruption and a deep-seated pustule showed epidermal necrosis, parakeratosis, necrotic keratinocytes, and a lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes at the dermoepidermal interface. In the dermis, there was a wedge-shaped superficial and deep, perivascular infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes (Figures 3 and 4). Tissue Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus immunostains were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed colloid bodies, as can be seen in lichenoid dermatitis.

At the next clinic visit, the patient reported a fever of 39.4 °C. After reviewing the patient’s histopathology and clinical picture, along with the presence of fever, a final diagnosis of FUMHD was made. The patient was started on an oral regimen of prednisone 80 mg once daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and methotrexate 15 mg weekly. Unna boots (specialized compression wraps) with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% were placed weekly until the leg edema and ulcerations healed. He was maintained on methotrexate 15 mg weekly and 5 to 10 mg of prednisone once daily. The patient demonstrated residual scarring, with only rare new papulonodules that did not ulcerate when attempts were made to taper his medications. He was followed for nearly 3 years, with a recurrence of symptoms 2 years and 3 months after initial presentation to the academic dermatology clinic.

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA that can present with the rapid appearance of necrotic skin lesions, fever, and systemic manifestations, including pulmonary, gastrointestinal, central nervous system, cardiac, hematologic, and rheumatologic symptoms.2-4 The evolution from PLEVA to FUMHD ranges from days to weeks, and patientsrarely can have an initial presentation of FUMHD.2 The duration of illness has been reported to be 1 to 24 months5; however, the length of illness still remains unclear, as many studies of FUMHD are case reports with limited follow-up. Our patient had a disease duration of at least 27 months. The lesions of FUMHD usually are generalized with flexural prominence, and mucosal involvement occurs in approximately one-quarter of cases. Hypertrophic scarring may be seen after the ulcerated lesions heal.2 The incidence of FUMHD is higher in men than in women, and it is more common in younger individuals.2,6 There have been reported fatalities associated with FUMHD, mostly in adults.2,4

The clinical differential diagnosis for PLEVA includes disseminated herpes zoster, varicella-zoster virus or coxsackievirus infections, lymphomatoid papulosis, angiodestructive lymphoma such as extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, drug eruption, arthropod bite, erythema multiforme, ecthyma, ecthyma gangrenosum, necrotic folliculitis, and cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. To differentiate between these diagnoses and PLEVA or FUMHD, it is important to take a strong clinical history. For example, for varicella-zoster virus and coxsackievirus infections, exposure history to the viruses and vaccination history for varicella-zoster virus can help elucidate the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy can help differentiate between these entities and PLEVA or FUMHD. The histopathology of a nonulcerated lesion of FUMHD shows parakeratosis, spongiosis, and lymphocyte exocytosis, as well as lymphocytic vasculitis—findings commonly seen in PLEVA. With the ulceronecrotic lesions of FUMHD, epidermal necrosis and ulceration can be seen microscopically.2 Although skin biopsy is not absolutely necessary for making the diagnosis of PLEVA, it can be helpful.3 However, given the dramatic and extreme clinical impression with an extensive differential diagnosis that includes disorders ranging from infectious to neoplastic, biopsy of FUMHD with clinicopathologic correlation often is required.

It is important to avoid biopsying ulcerated lesions of FUMHD, as the histopathologic findings are more likely to be nonspecific. Additionally, nonspecific features often are seen with immunohistochemistry; abnormal laboratory testing may be seen in FUMHD, but there is no specific test to diagnose FUMHD.2 Finally, a predominantly CD8+ cell infiltrate was seen in 4 of 6 cases of FUMHD, with 2 cases showing a mixed infiltrate of CD8+ and CD4+ cells.5,7-10

Although no unified diagnostic criterion exists for FUMHD, Nofal et al2 proposed criteria comprised of constant features, which are found in every case of FUMHD and can confirm the diagnosis alone, and variable features to help ensure that cases of FUMHD are not missed. The constant features include fever, acute onset of generalized ulceronecrotic papules and plaques, a course that is rapid and progressive (without a tendency for spontaneous resolution), and histopathology that is consistent with PLEVA. The variable features include history of PLEVA, involvement of mucous membranes, and systemic involvement.2

No single unifying treatment modality for all cases of FUMHD has been described. Immunosuppressive drugs (eg, systemic steroids, methotrexate), antibiotics, antivirals, phototherapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, and dapsone have been tried in patients with FUMHD.2 Combination therapy with an oral medication such as erythromycin or methotrexate and psoralen plus UVA may be effective for FUMHD.3 Additionally, some authors believe that patients with FUMHD should be treated similar to burn victims with intensive supportive care.2

The etiology of PLEVA is unknown, but it is presumed to be associated with an effector cytotoxic T-cell response to either an infectious agent or a drug.11

Four cases of FUMHD with monoclonality have been reported,4,7,8 and some researchers propose that FUMHD may be a subset of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.7 However, 2 other cases of FUMHD did not show monoclonality of T cells,5,18 suggesting that FUMHD may represent an inflammatory disorder, rather than a lymphoproliferative process of T cells.18 Given the controversy surrounding the clonality of FUMHD, T-cell gene rearrangement studies were not performed in our case.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis lichenoides is a papulosquamous dermatologic disorder that is characterized by recurrent papules.1 There is a spectrum of disease in pityriasis lichenoides that includes pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) at one end and pityriasis lichenoides chronica at the other. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is more common in younger individuals and is characterized by erythematous papules that often crust; these lesions resolve over weeks. The lesions of pityriasis lichenoides chronica are characteristically scaly, pink to red-brown papules that tend to resolve over months.1

Histologically, PLEVA exhibits parakeratosis, interface dermatitis, and a wedge-shaped infiltrate.1 Necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes also are common features. Additionally, monoclonal T cells may be present in the infiltrate.1

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD) is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is characterized by ulceronecrotic lesions, fever, and systemic symptoms.2 Herein, we present a case of FUMHD.

A 57-year-old man presented with an eruption of painful lesions involving the face, trunk, arms, legs, and genitalia of 1 month’s duration. The patient denied oral and ocular involvement. He had soreness and swelling of the arms and legs. A prior 12-day course of prednisone prescribed by a community dermatologist failed to improve the rash. A biopsy performed by a community dermatologist was nondiagnostic. The patient denied fever but did report chills. He had no preceding illness and was not taking new medications. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and normotensive with innumerable deep-seated pustules and crusted ulcerations on the face, palms, soles, trunk, extremities, and penis (Figures 1 and 2). There was a background morbilliform eruption on the trunk. The ocular and oral mucosae were spared. The upper and lower extremities had pitting edema.

The patient’s alanine aminotransaminase and aspartate aminotransaminase levels were elevated at 55 and 51 U/L, respectively. His white blood cell count was within reference range; however, there was an elevated absolute neutrophil count (8.7×103/μL). No eosinophilia was noted. Laboratory evaluation showed a positive antimitochondrial antibody, and magnetic resonance imaging showed evidence of steatohepatitis. Punch biopsies from both the morbilliform eruption and a deep-seated pustule showed epidermal necrosis, parakeratosis, necrotic keratinocytes, and a lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes at the dermoepidermal interface. In the dermis, there was a wedge-shaped superficial and deep, perivascular infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes (Figures 3 and 4). Tissue Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus immunostains were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed colloid bodies, as can be seen in lichenoid dermatitis.

At the next clinic visit, the patient reported a fever of 39.4 °C. After reviewing the patient’s histopathology and clinical picture, along with the presence of fever, a final diagnosis of FUMHD was made. The patient was started on an oral regimen of prednisone 80 mg once daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and methotrexate 15 mg weekly. Unna boots (specialized compression wraps) with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% were placed weekly until the leg edema and ulcerations healed. He was maintained on methotrexate 15 mg weekly and 5 to 10 mg of prednisone once daily. The patient demonstrated residual scarring, with only rare new papulonodules that did not ulcerate when attempts were made to taper his medications. He was followed for nearly 3 years, with a recurrence of symptoms 2 years and 3 months after initial presentation to the academic dermatology clinic.

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA that can present with the rapid appearance of necrotic skin lesions, fever, and systemic manifestations, including pulmonary, gastrointestinal, central nervous system, cardiac, hematologic, and rheumatologic symptoms.2-4 The evolution from PLEVA to FUMHD ranges from days to weeks, and patientsrarely can have an initial presentation of FUMHD.2 The duration of illness has been reported to be 1 to 24 months5; however, the length of illness still remains unclear, as many studies of FUMHD are case reports with limited follow-up. Our patient had a disease duration of at least 27 months. The lesions of FUMHD usually are generalized with flexural prominence, and mucosal involvement occurs in approximately one-quarter of cases. Hypertrophic scarring may be seen after the ulcerated lesions heal.2 The incidence of FUMHD is higher in men than in women, and it is more common in younger individuals.2,6 There have been reported fatalities associated with FUMHD, mostly in adults.2,4

The clinical differential diagnosis for PLEVA includes disseminated herpes zoster, varicella-zoster virus or coxsackievirus infections, lymphomatoid papulosis, angiodestructive lymphoma such as extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, drug eruption, arthropod bite, erythema multiforme, ecthyma, ecthyma gangrenosum, necrotic folliculitis, and cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. To differentiate between these diagnoses and PLEVA or FUMHD, it is important to take a strong clinical history. For example, for varicella-zoster virus and coxsackievirus infections, exposure history to the viruses and vaccination history for varicella-zoster virus can help elucidate the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy can help differentiate between these entities and PLEVA or FUMHD. The histopathology of a nonulcerated lesion of FUMHD shows parakeratosis, spongiosis, and lymphocyte exocytosis, as well as lymphocytic vasculitis—findings commonly seen in PLEVA. With the ulceronecrotic lesions of FUMHD, epidermal necrosis and ulceration can be seen microscopically.2 Although skin biopsy is not absolutely necessary for making the diagnosis of PLEVA, it can be helpful.3 However, given the dramatic and extreme clinical impression with an extensive differential diagnosis that includes disorders ranging from infectious to neoplastic, biopsy of FUMHD with clinicopathologic correlation often is required.

It is important to avoid biopsying ulcerated lesions of FUMHD, as the histopathologic findings are more likely to be nonspecific. Additionally, nonspecific features often are seen with immunohistochemistry; abnormal laboratory testing may be seen in FUMHD, but there is no specific test to diagnose FUMHD.2 Finally, a predominantly CD8+ cell infiltrate was seen in 4 of 6 cases of FUMHD, with 2 cases showing a mixed infiltrate of CD8+ and CD4+ cells.5,7-10

Although no unified diagnostic criterion exists for FUMHD, Nofal et al2 proposed criteria comprised of constant features, which are found in every case of FUMHD and can confirm the diagnosis alone, and variable features to help ensure that cases of FUMHD are not missed. The constant features include fever, acute onset of generalized ulceronecrotic papules and plaques, a course that is rapid and progressive (without a tendency for spontaneous resolution), and histopathology that is consistent with PLEVA. The variable features include history of PLEVA, involvement of mucous membranes, and systemic involvement.2