User login

Multiple Eruptive Dermatofibromas Associated With Down Syndrome

To the Editor:

Dermatofibromas (also known as fibrous histiocytomas) are benign fibrous nodules that most often arise as solitary lesions on the lower extremities. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas (MEDFs) are uncommon and have been defined as more than 15 in number1 or 5 to 8 dermatofibromas appearing within 4 months.2 They have been reported in association with a number of conditions of immune dysregulation such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, HIV infection, and leukemia.3 Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas also have been described in patients with Down syndrome (DS).4-7 We report a case of MEDFs in a patient with DS and review the literature on the association between MEDFs and DS.

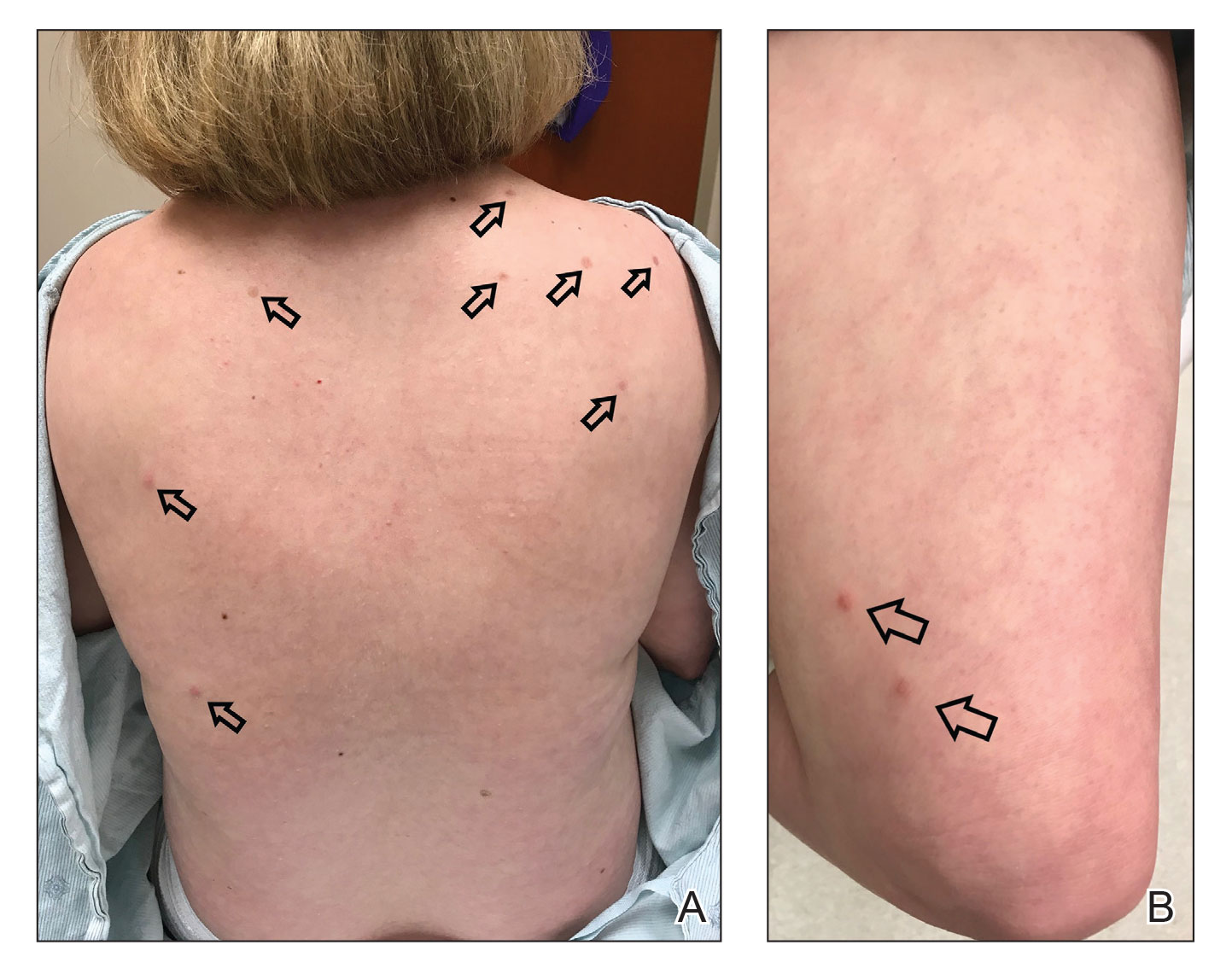

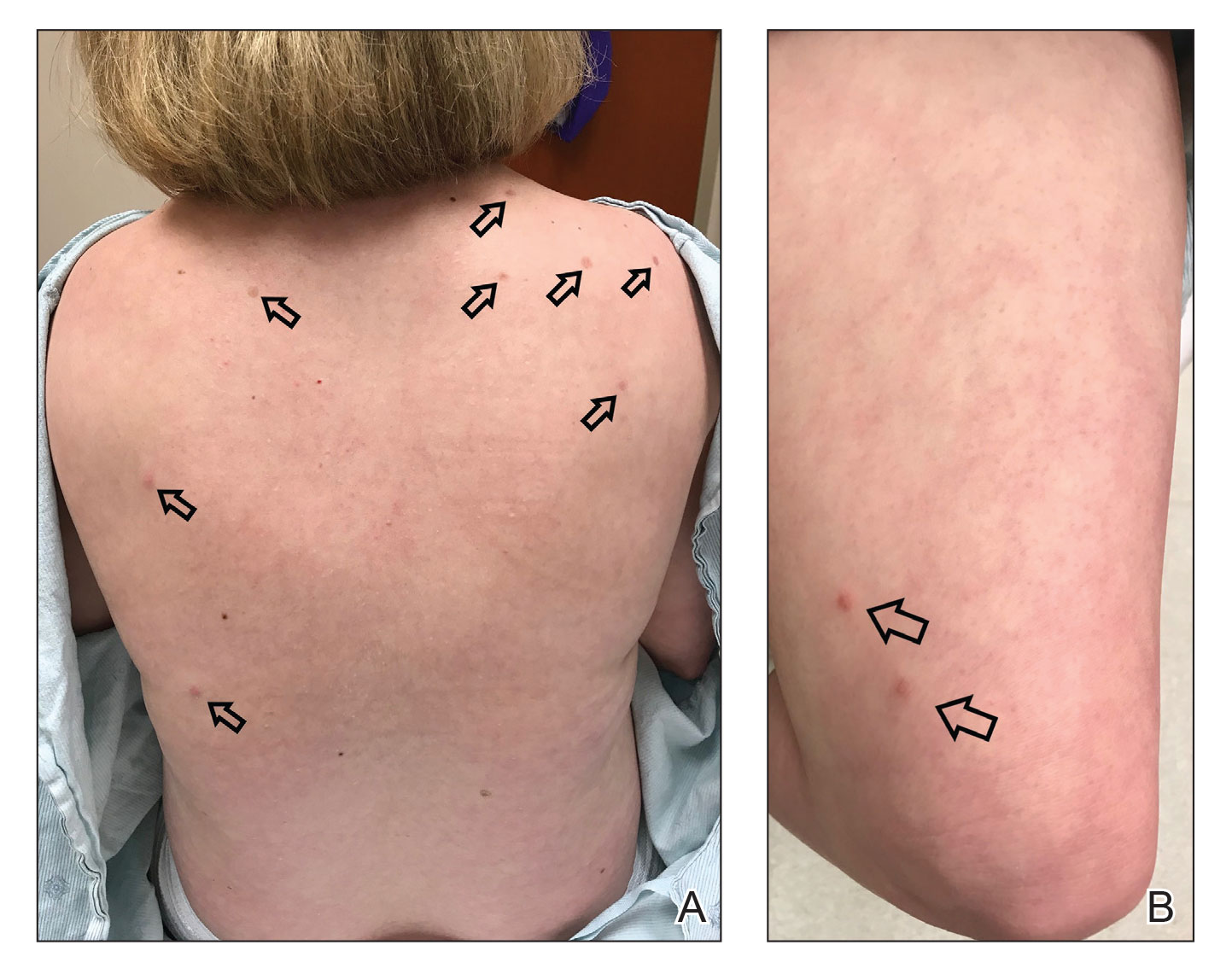

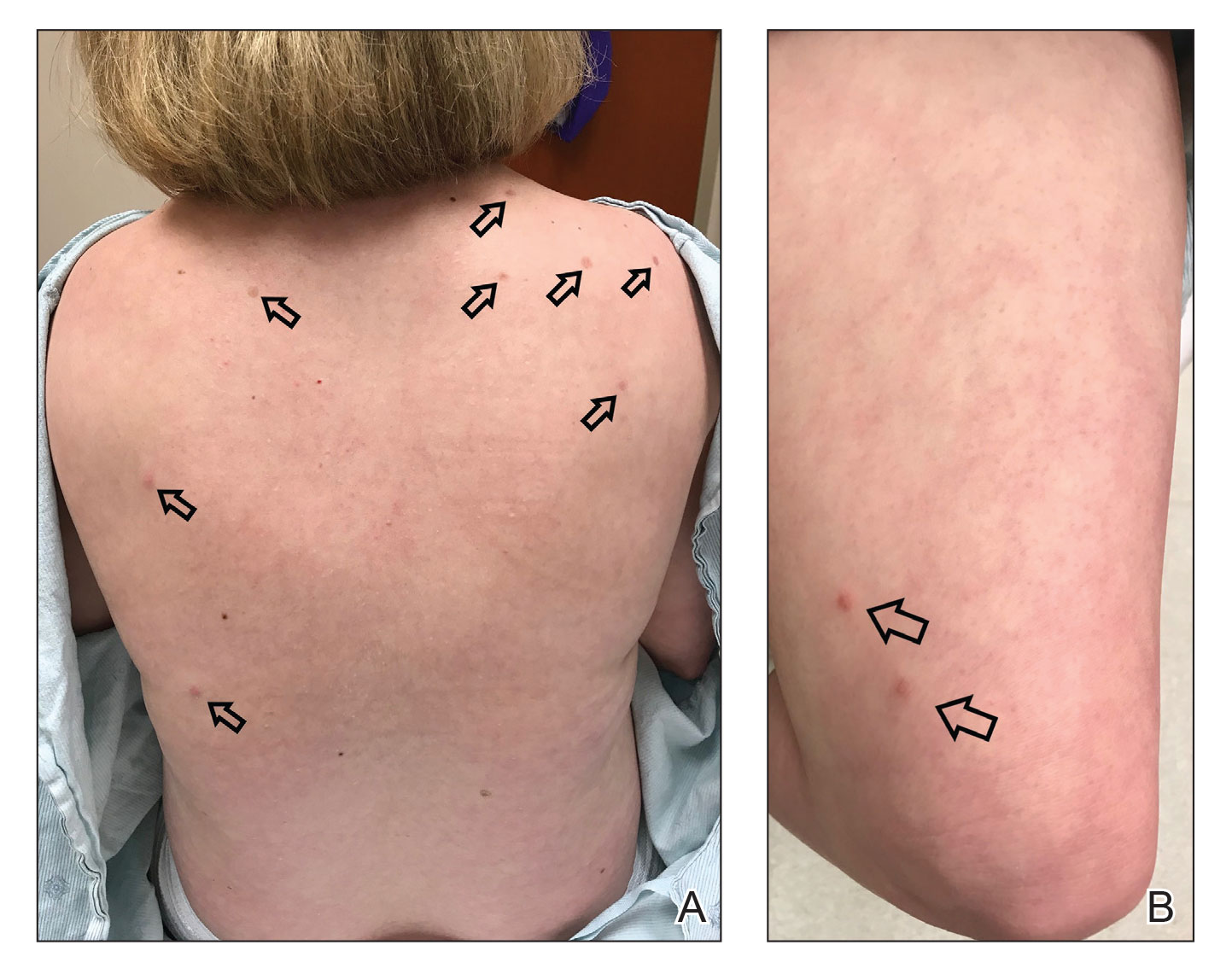

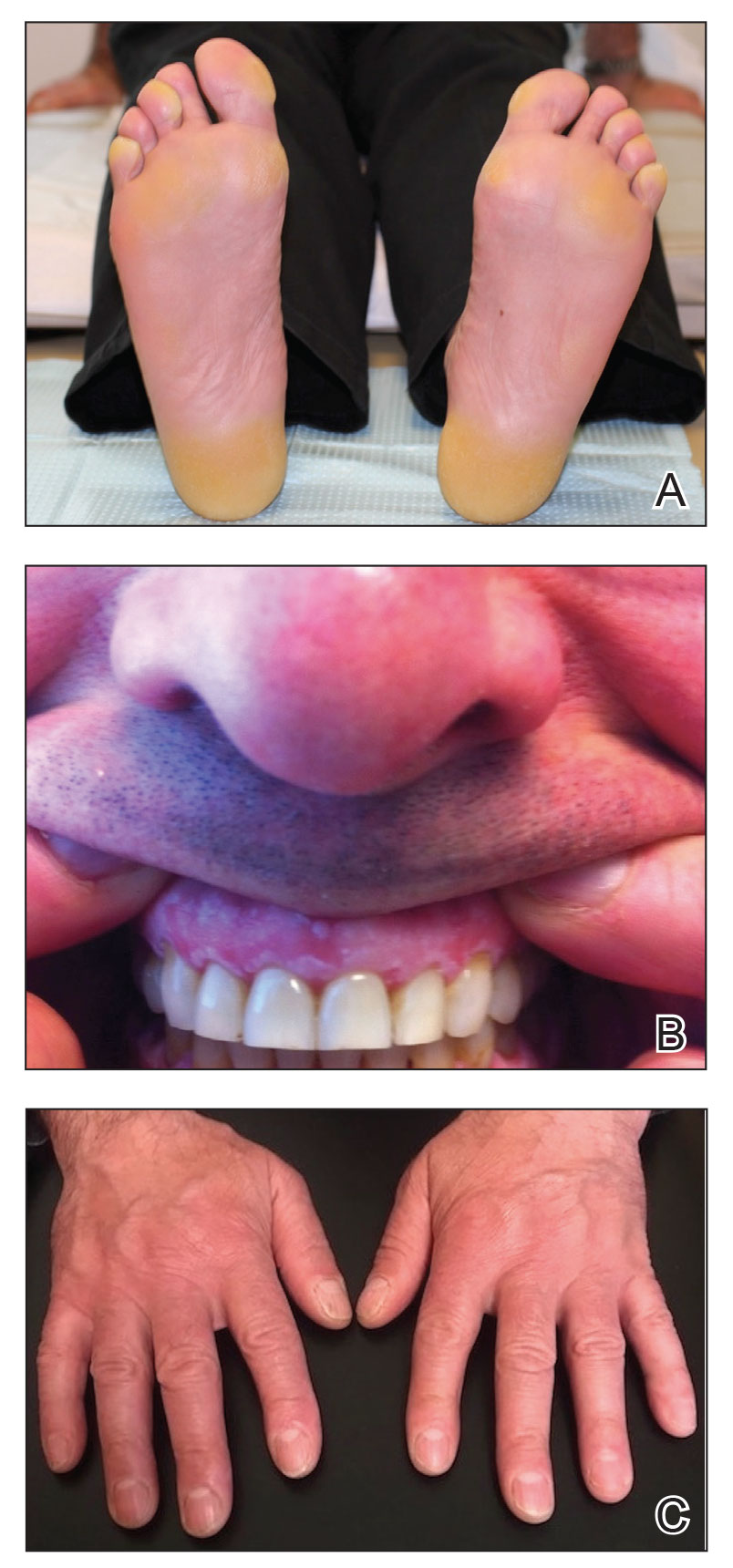

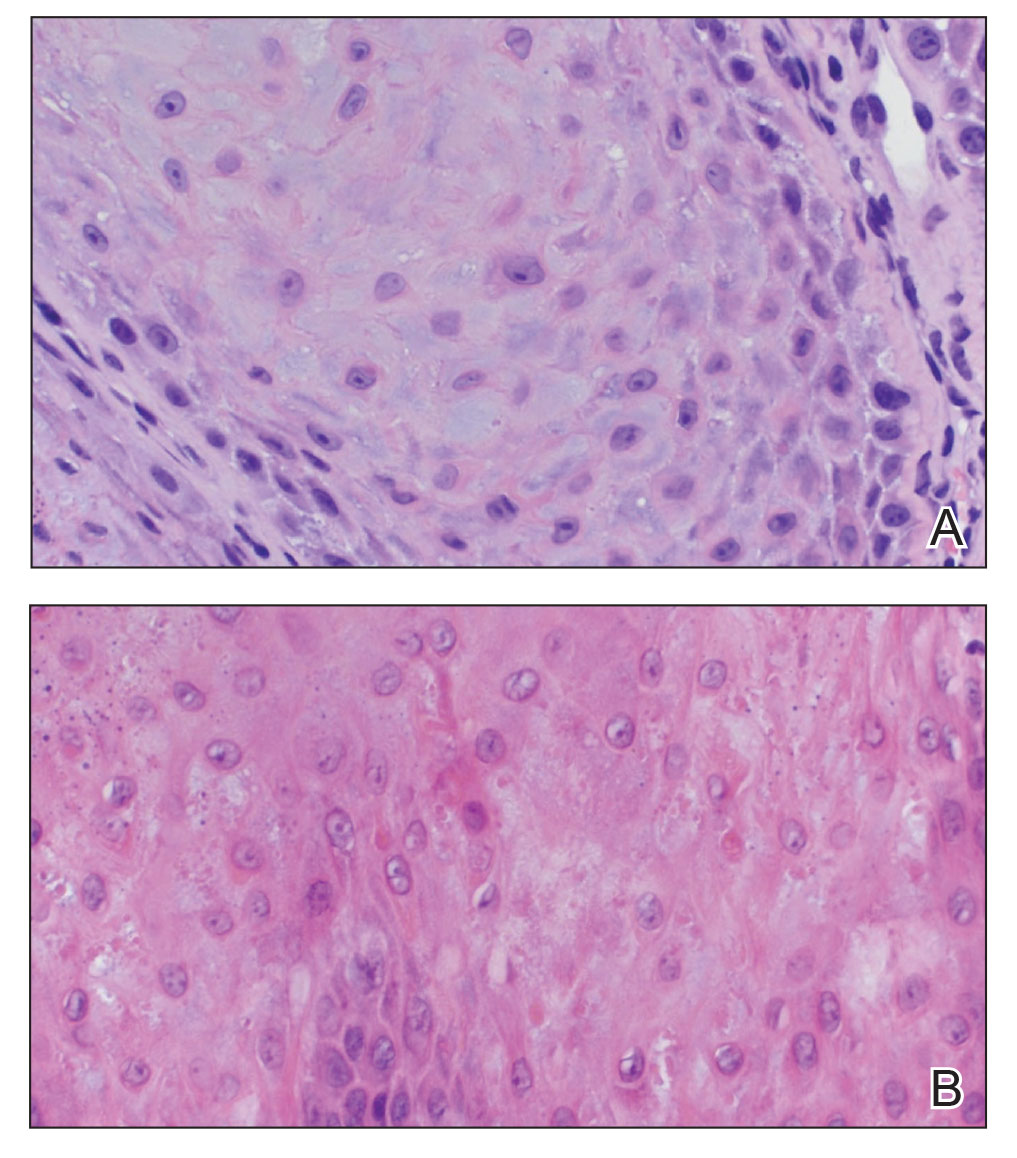

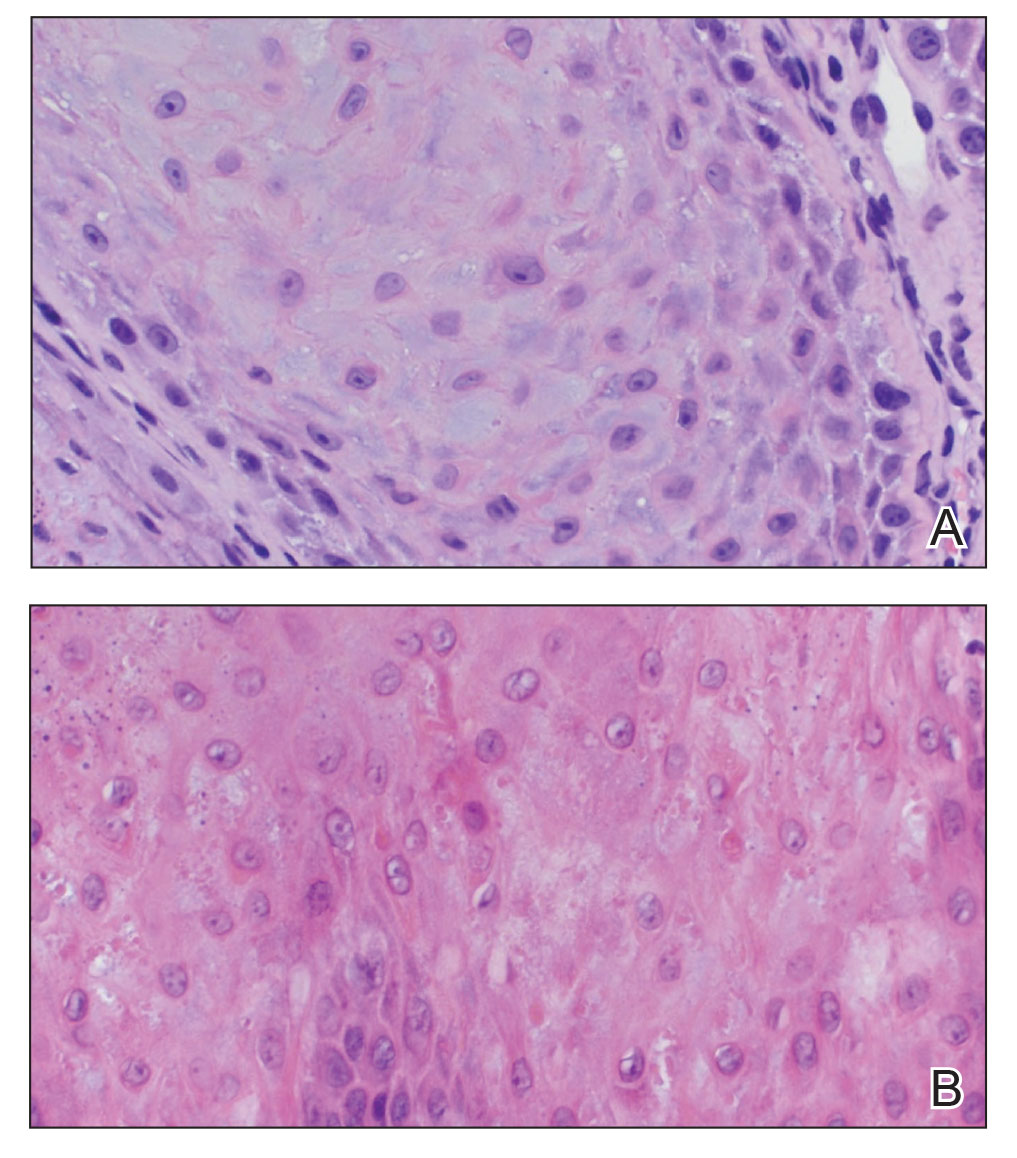

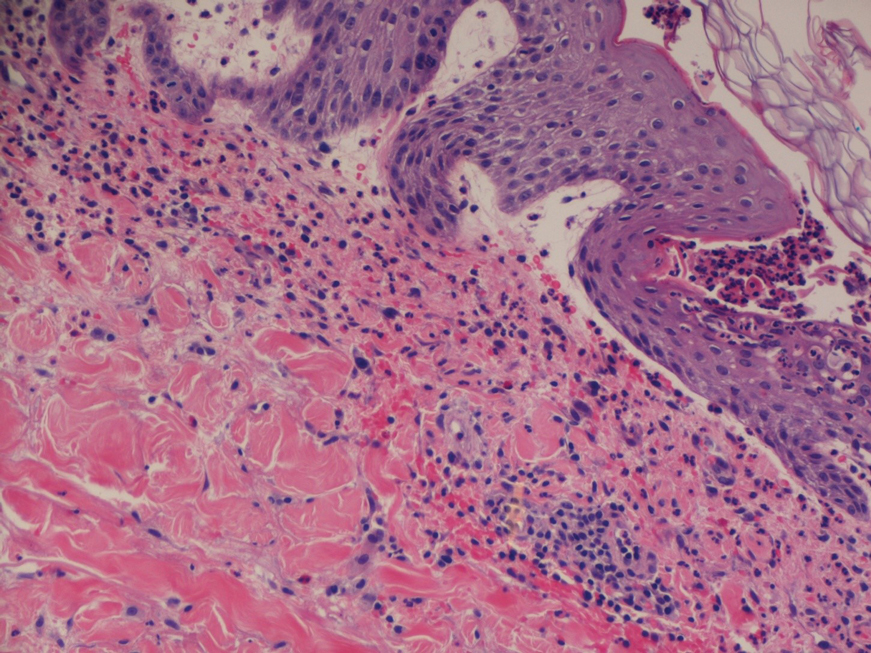

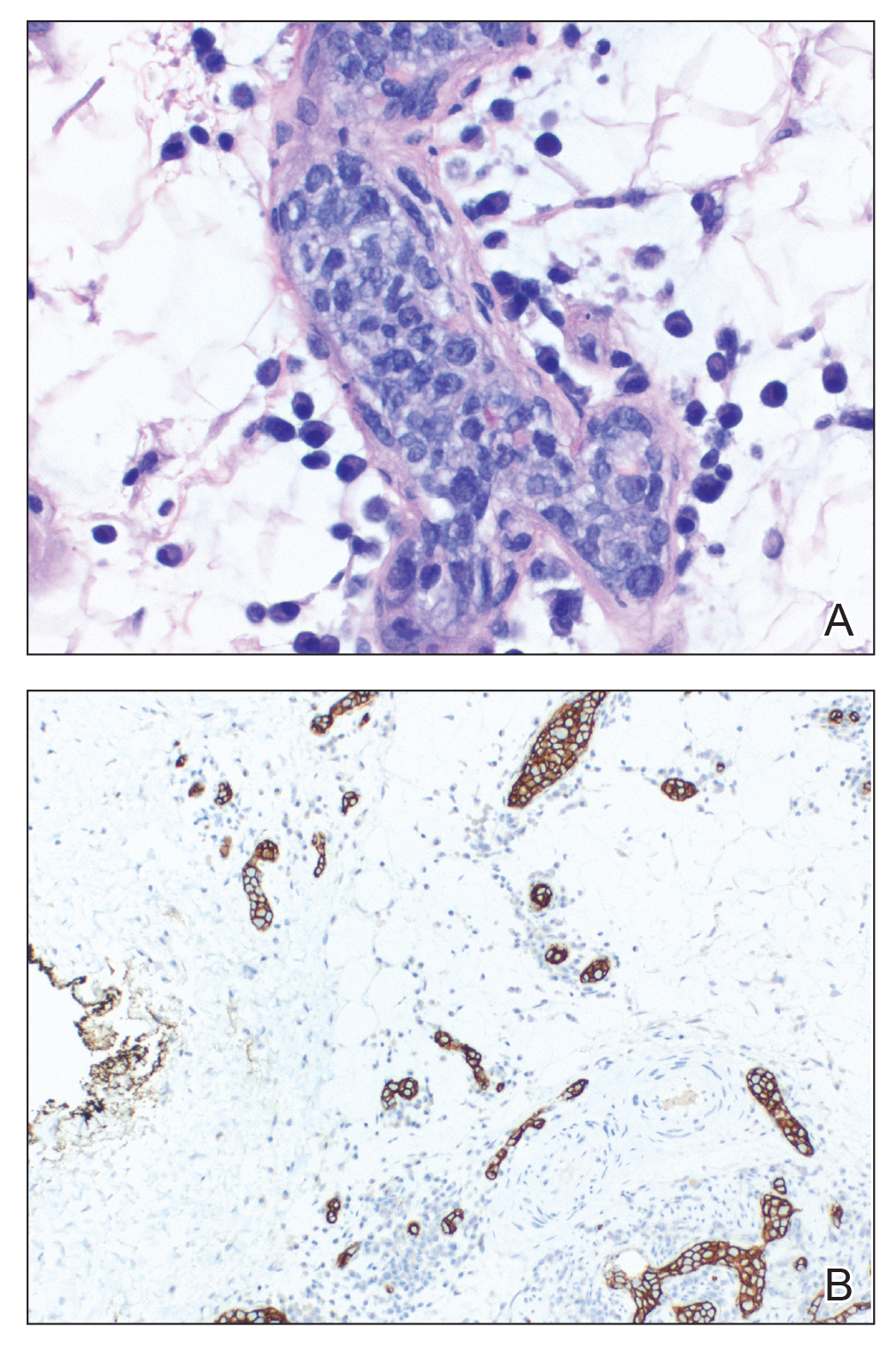

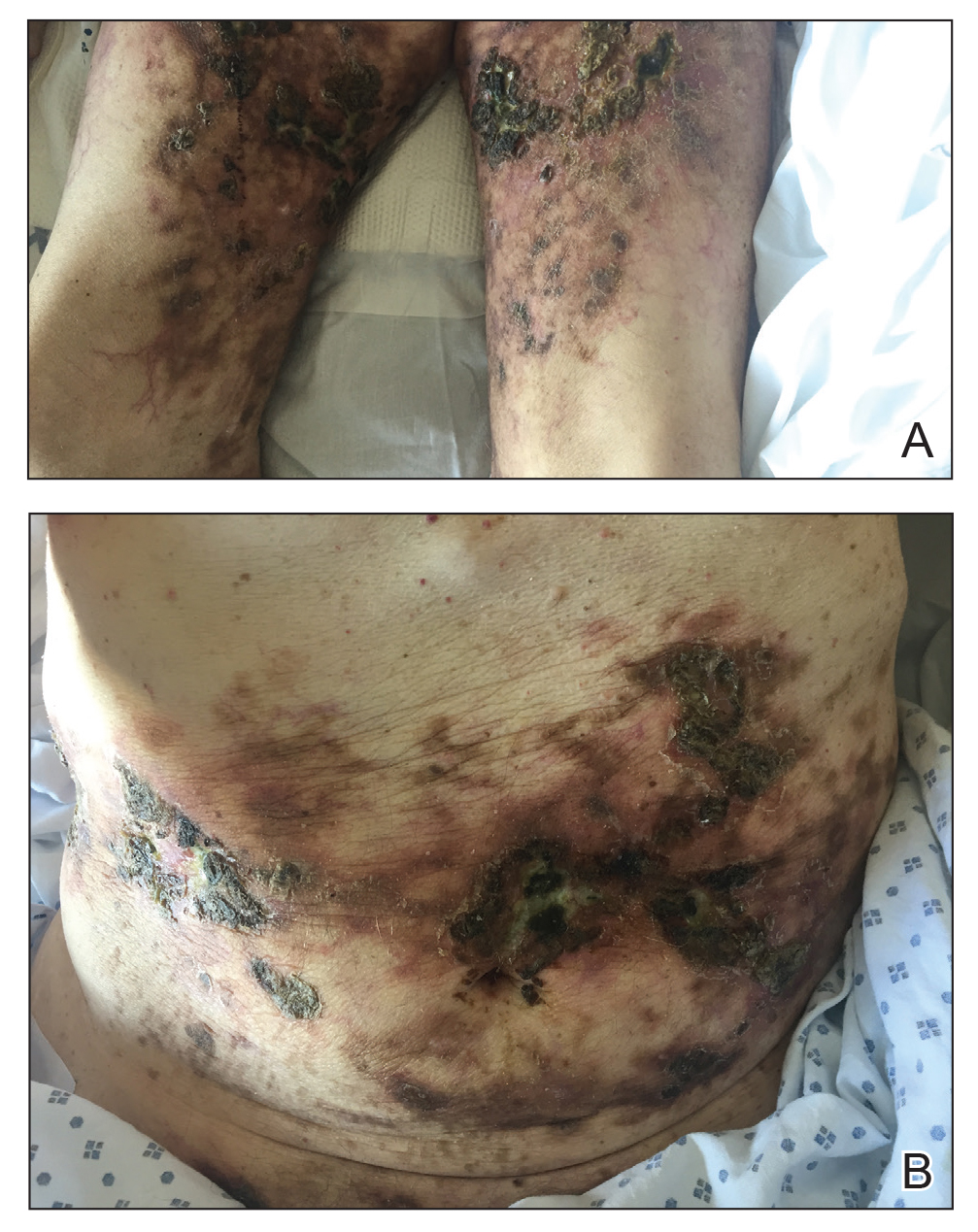

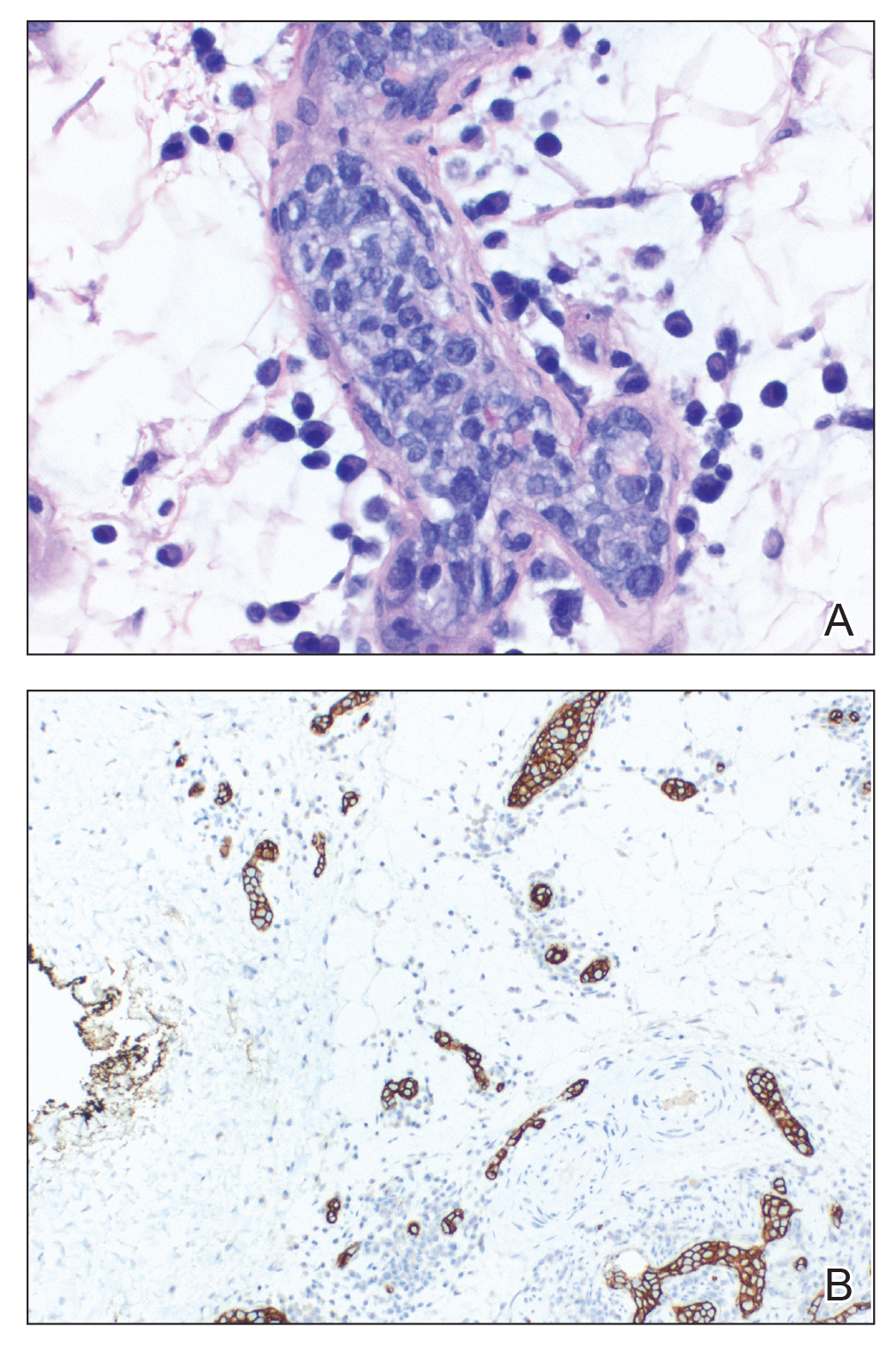

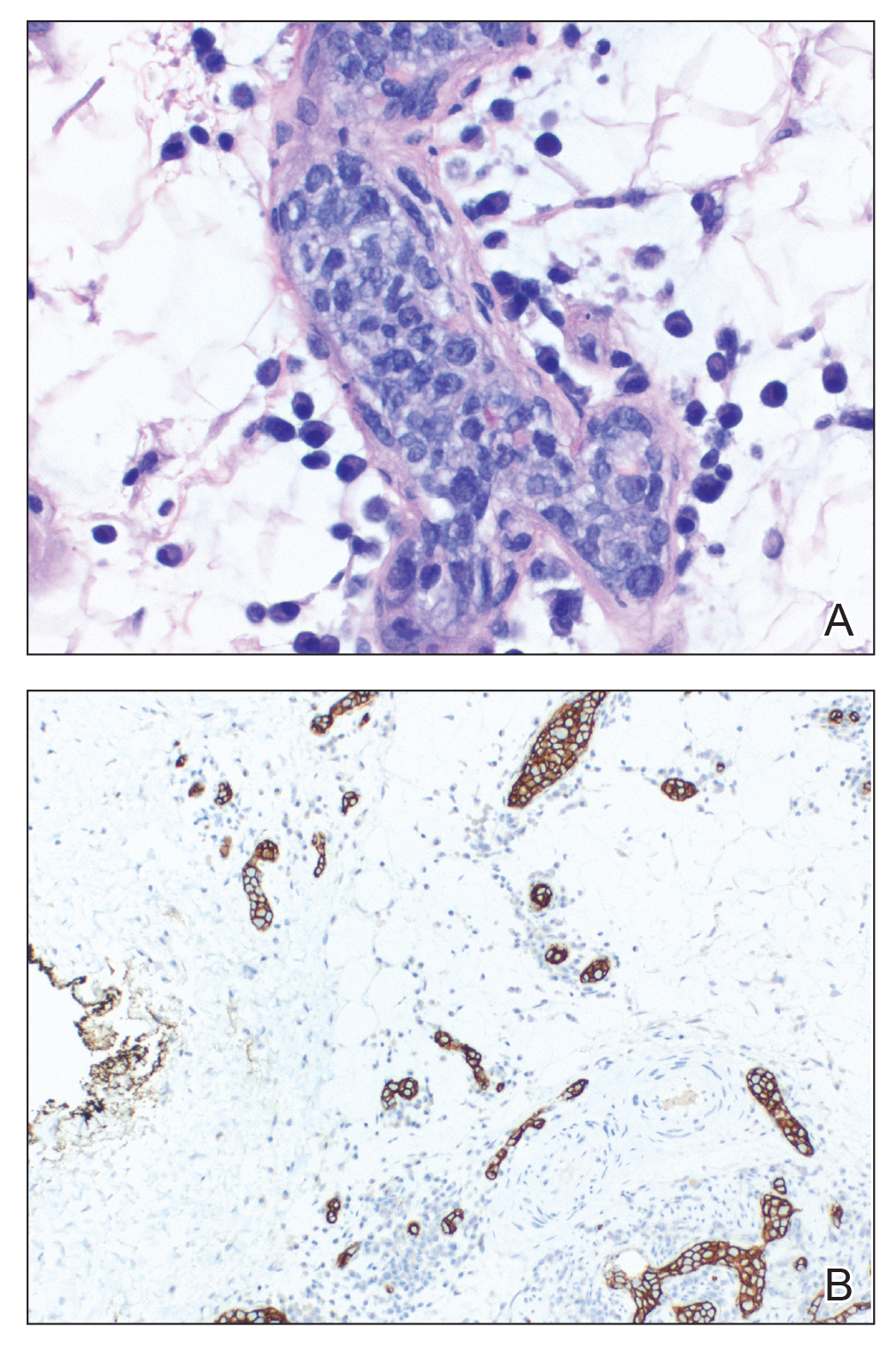

A 38-year-old woman with DS, hidradenitis suppurativa, and hypothyroidism presented with multiple cutaneous lesions developing over the last year. The lesions continued to increase in number but were otherwise asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed approximately 20 rubbery, pink-tan papules measuring less than 1 cm in diameter that were scattered along the trunk (Figure, A), arms, and legs (Figure, B).

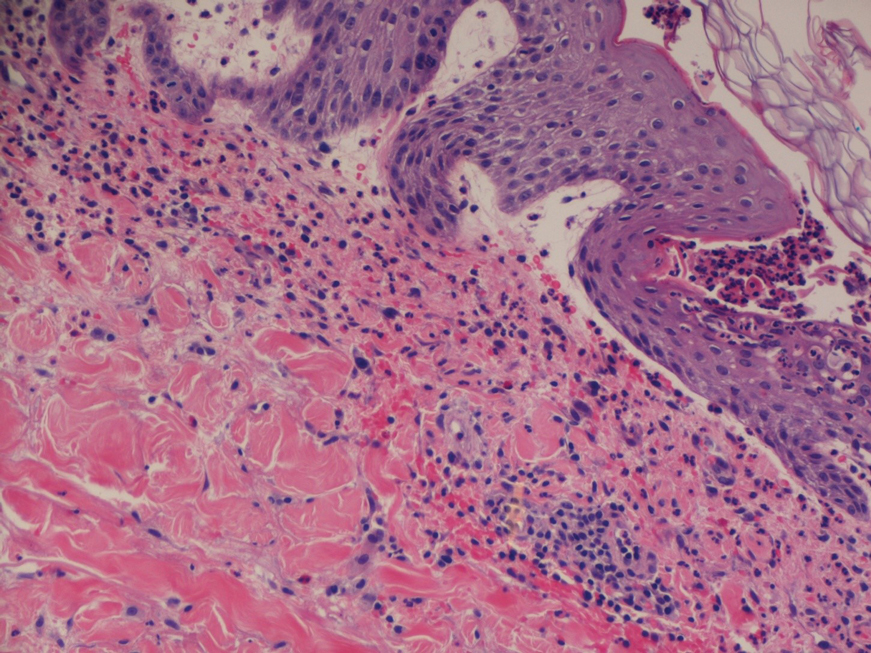

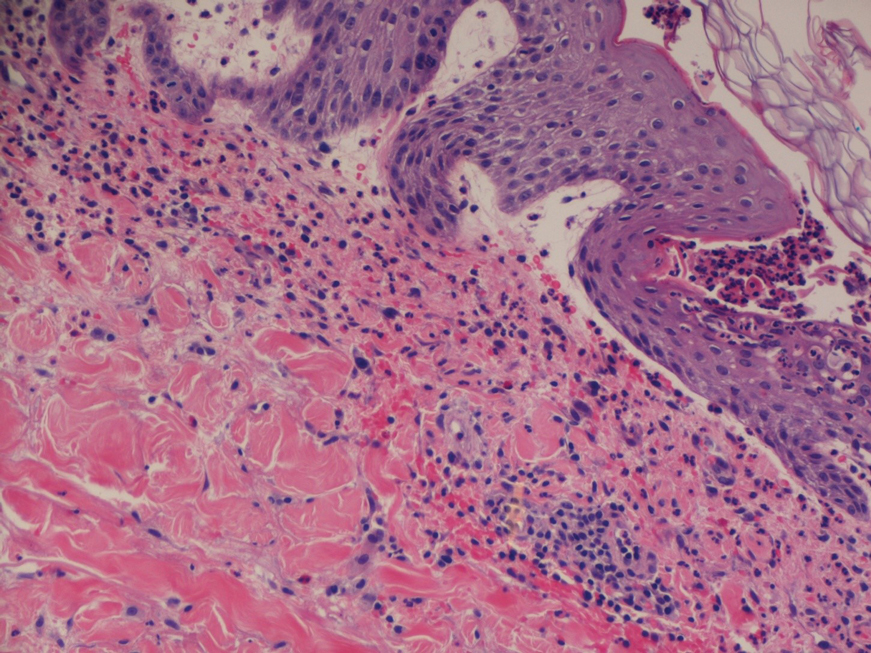

The patient had no known history of immunosuppression or rheumatologic disease and was otherwise healthy. Basic laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count and antinuclear antibody titer were within reference range. The lesions were clinically consistent with dermatofibromas, but due to their increasing number within a short period of time, a biopsy of a representative lesion was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

The exact incidence of MEDFs is unknown, but they are rare, with one review finding only 50 cases reported from 1960 to 2002.8 They are increasingly recognized as a sign of potential immune dysregulation. Approximately 56% to 70% of cases are seen in patients with an underlying disease state; 80% are immune mediated.8,9 Interestingly, DS has long been associated with notable immune dysfunction,10,11 with evidence suggesting that trisomy 21 may result in widespread changes in gene expression that can lead to interferon activation.12

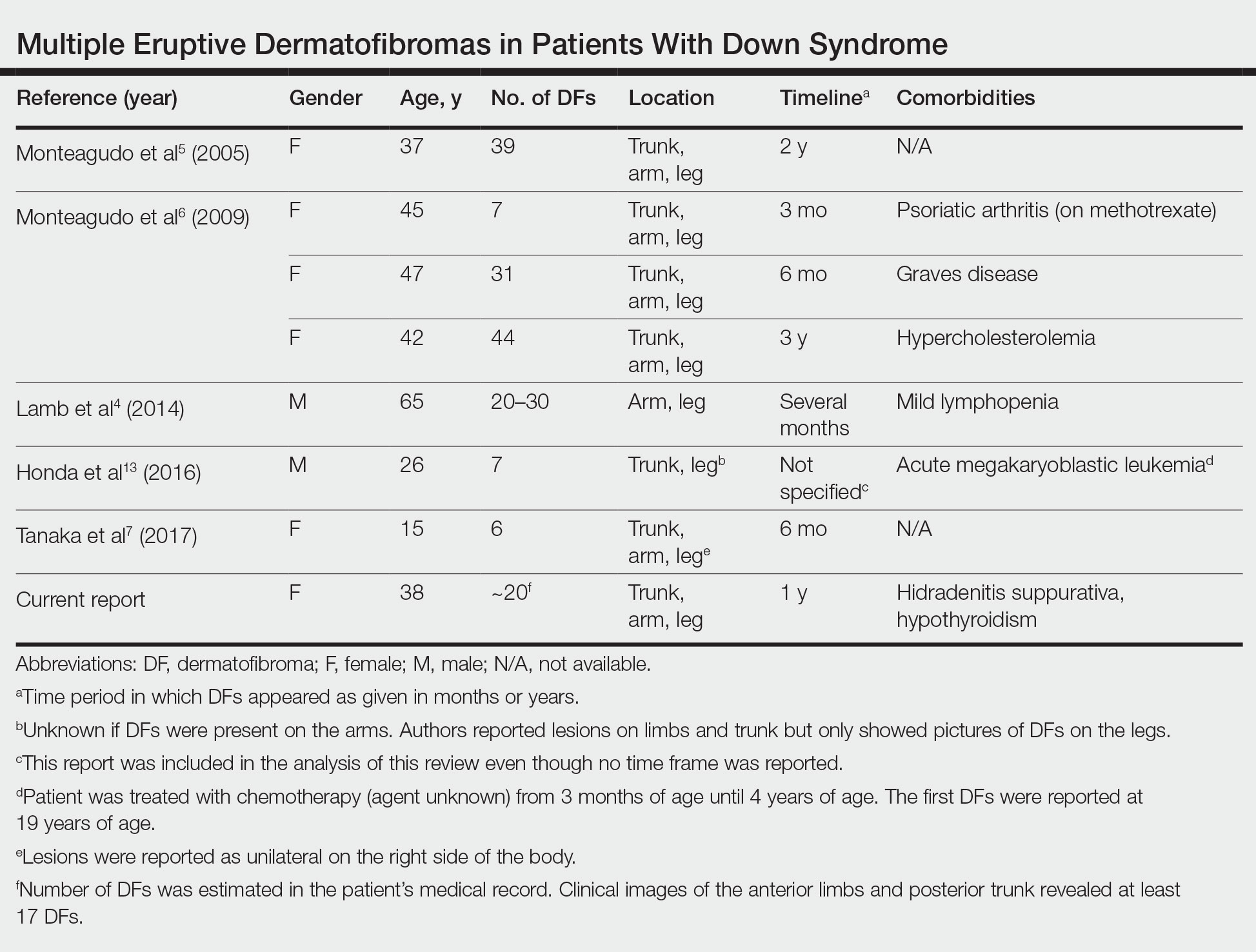

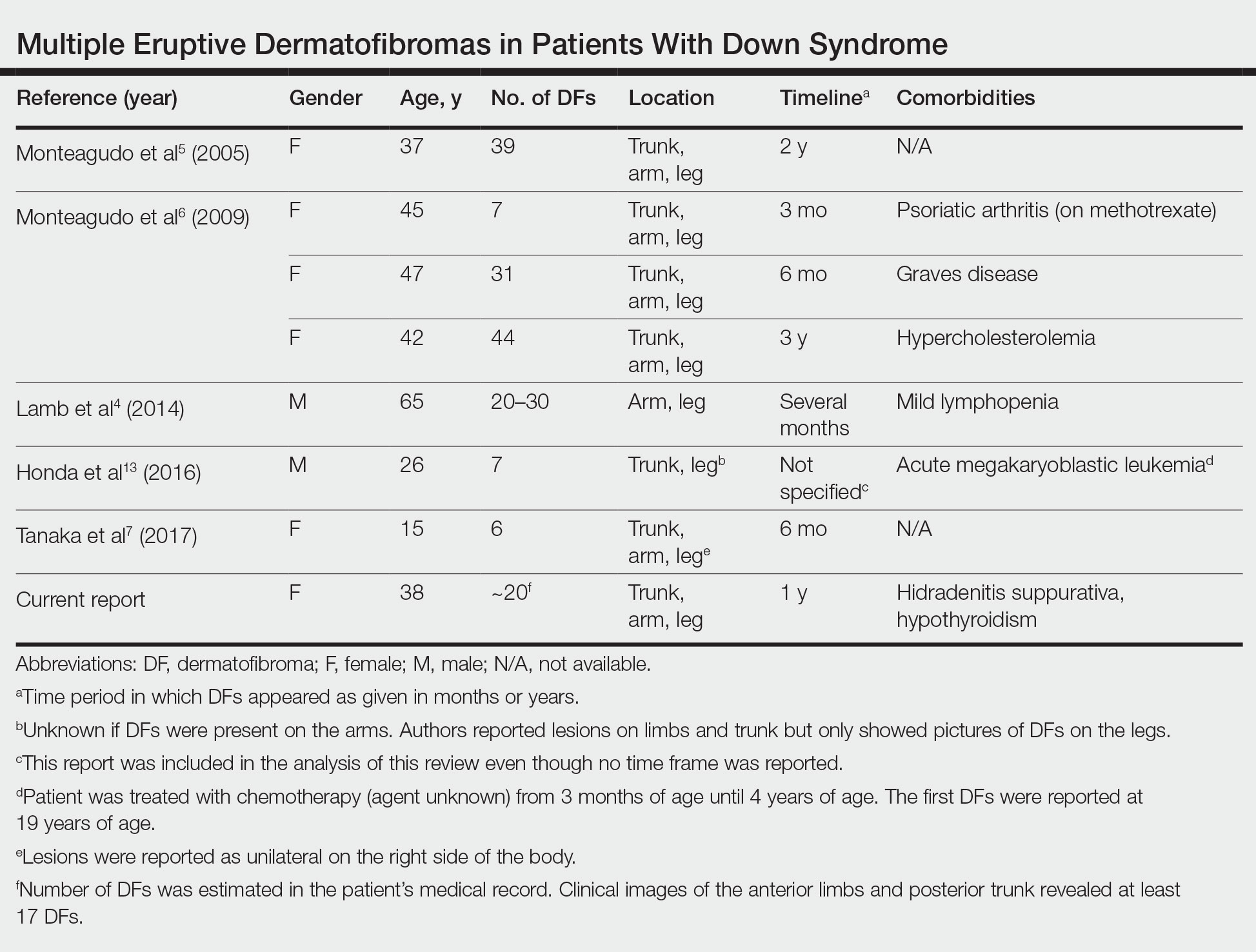

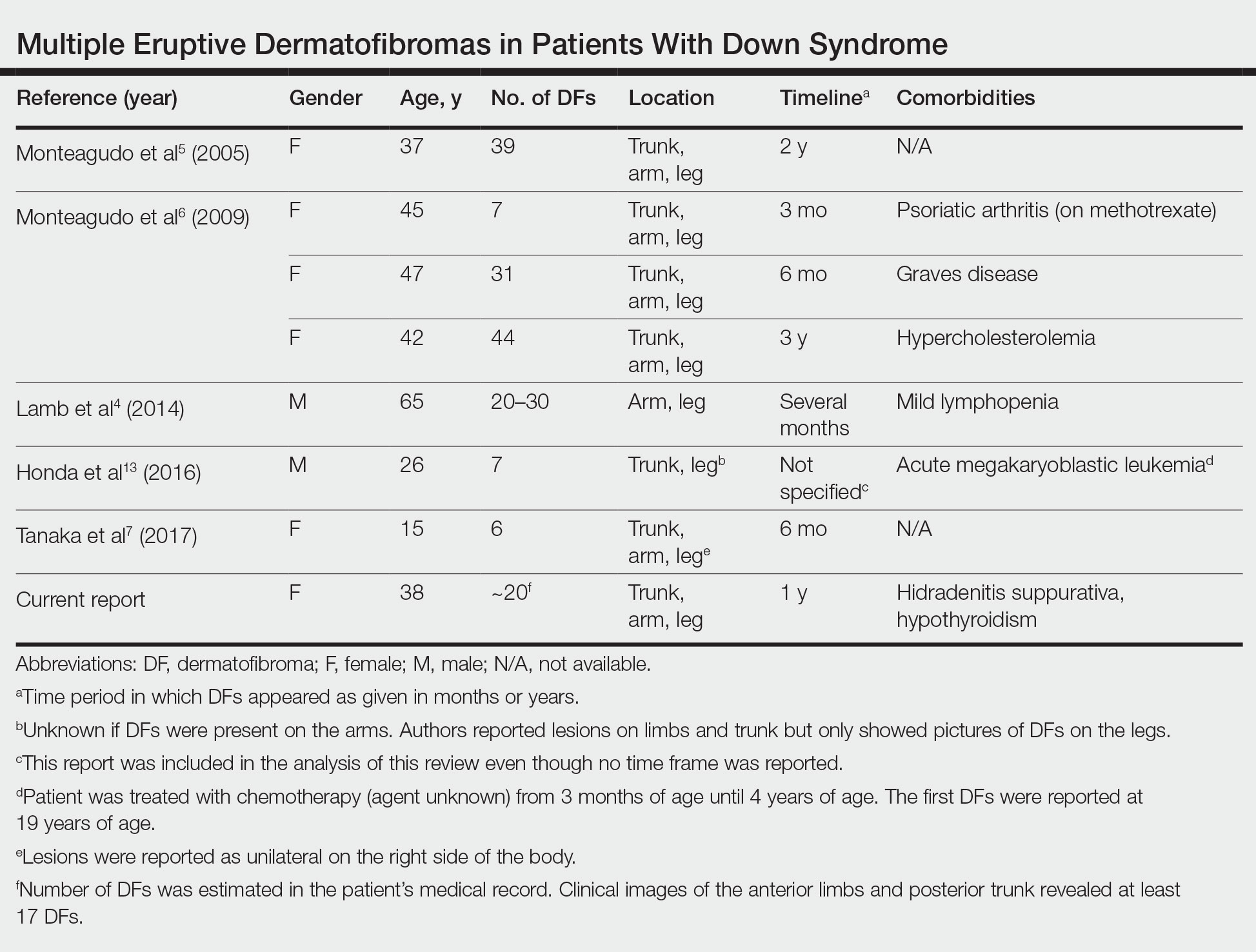

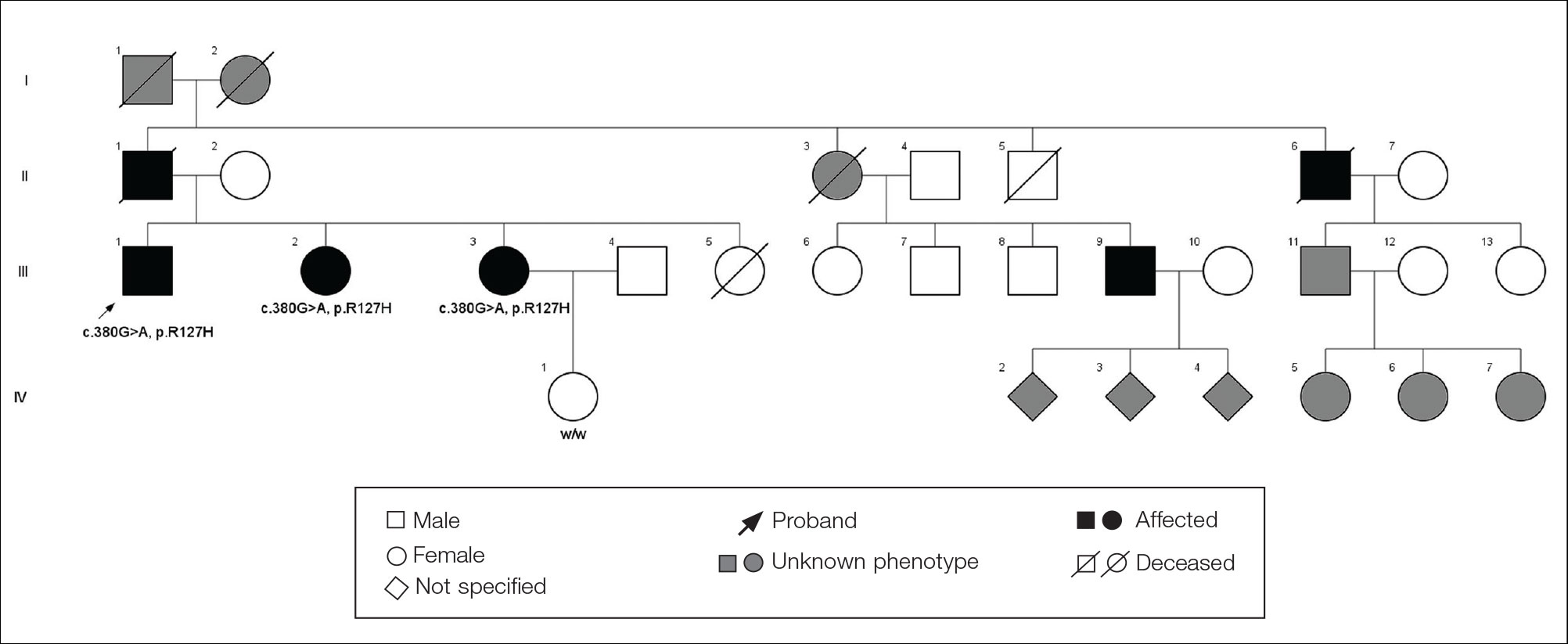

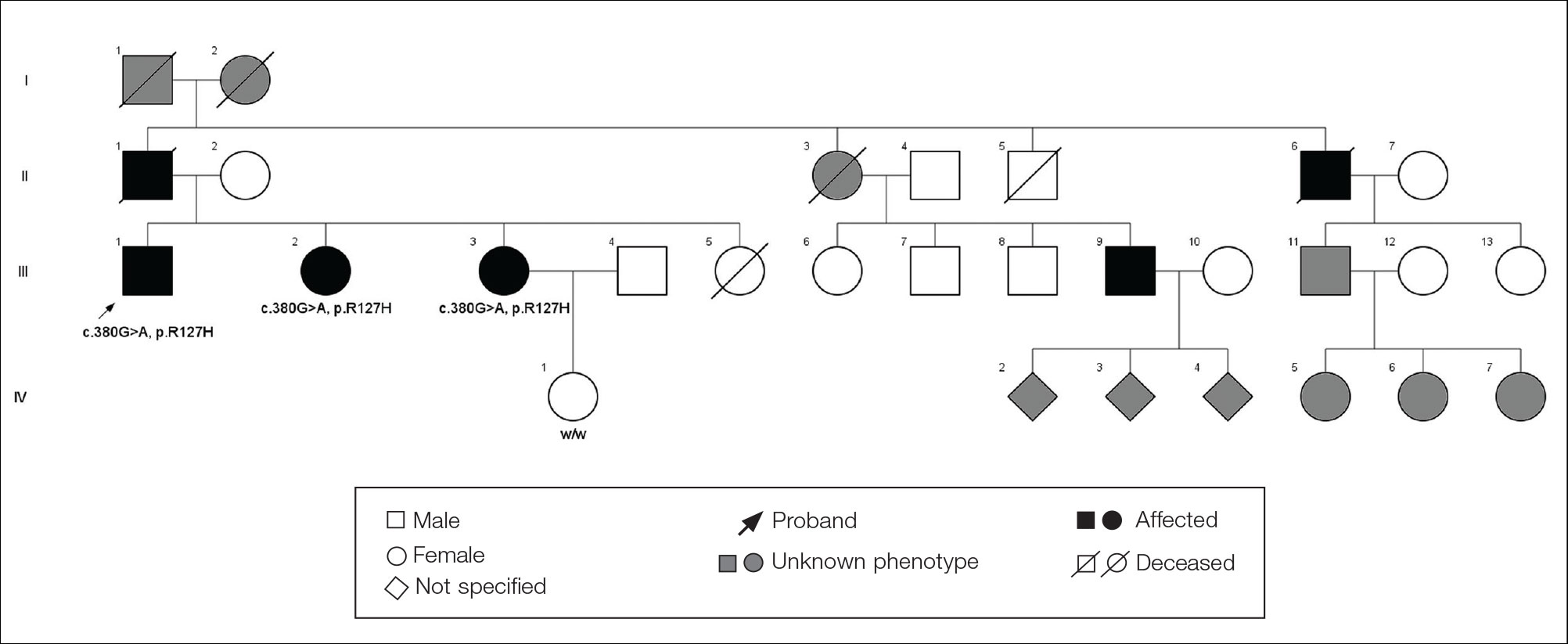

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms dermatofibroma and Down, dermatofibroma and Down syndrome, eruptive dermatofibroma and Down syndrome, and multiple dermatofibroma and Down syndrome revealed 6 cases of MEDFs in patients with DS that have been reported since 2005.4-7 An additional report by Honda et al13 described a patient with DS who developed 7 dermatofibromas, but no time frame of development was specified. We reviewed the characteristics of 8 patients with DS with MEDFs, which included our patient (Table). The average age at time of presentation was 39 years (median age, 40 years). Six patients (75%) were female and 2 (25%) were male. Dermatofibromas were reported to appear over the course of months to years. Comorbidities included psoriatic arthritis (treated with methotrexate),6 thyroid disorders (ie, Graves disease),6 hypercholesterolemia,6 hidradenitis suppurativa, long-standing mild lymphopenia (1.4×109/L [reference range, 1.5−4.0×109/L]),4 and acute megakaryoblastic leukemia13 treated 15 years before the appearance of dermatofibromas.

Many dermatologic conditions have been reported at increased rates in individuals with DS, including seborrheic dermatitis, alopecia areata, syringomas, elastosis perforans serpiginosa, cutis marmorata, xerosis, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.14,15 Although drawing conclusions about associations between MEDFs and DS is limited by our small sample size, we have reported this case and reviewed existing cases of MEDFs in DS to highlight a potential association that may be underrecognized or underreported. More evidence is needed to determine the strength of the association between MEDFs and DS, but dermatologists should be aware that MEDFs may be an additional skin finding associated with DS that is related to the syndrome’s immune dysregulation.

- Baraf CS, Shapiro L. Multiple histiocytomas: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:588-590.

- Ammirati CT, Mann C, Hornstra IK. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in three men with HIV infection. Dermatology. 1997;4:344-348.

- Zaccaria E, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:723-727.

- Lamb RC, Gangopadhyay M, MacDonald A. Multiple dermatofibromas in Down syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E274-E275.

- Monteagudo B, Álvarez-Fernández JC, Iglesias B, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with Down’s syndrome [article in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:199.

- Monteagudo B, Suárez-Amor O, Cabanillas M, et al. Down syndrome: another cause of immunosuppression associated with multiple eruptive dermatofibroma? [article in Spanish]. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:15.

- Tanaka M, Hoashi T, Serizawa N, et al. Multiple unilaterally localized dermatofibromas in a patient with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2017;44:1074-1076.

- Niiyama S, Katsuoka K, Happle R, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:241-244.

- Her Y, Ku SH, Kim KH. A case of multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a healthy adult. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:539-540.

- Bertotto A, Arcangeli C, Crupi S, et al. T cell response to anti-CD3 antibody in Down’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:1148-1151.

- Kusters MA, Verstegen RH, Gemen EF, et al. Intrinsic defect of the immune system in children with Down syndrome: a review. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:189-193.

- Sullivan KD, Evans D, Pandey A, et al. Trisomy 21 causes changes in the circulating proteome indicative of chronic inflammation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14818.

- Honda M, Tomimura S, de Vega S, et al. Multiple dermatofibromas in a patient with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2016;43:346-348.

- Daneshpazhooh M, Nazemi TM, Bigdeloo L, et al. Mucocutaneous findings in 100 children with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:317-320.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down’s syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

To the Editor:

Dermatofibromas (also known as fibrous histiocytomas) are benign fibrous nodules that most often arise as solitary lesions on the lower extremities. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas (MEDFs) are uncommon and have been defined as more than 15 in number1 or 5 to 8 dermatofibromas appearing within 4 months.2 They have been reported in association with a number of conditions of immune dysregulation such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, HIV infection, and leukemia.3 Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas also have been described in patients with Down syndrome (DS).4-7 We report a case of MEDFs in a patient with DS and review the literature on the association between MEDFs and DS.

A 38-year-old woman with DS, hidradenitis suppurativa, and hypothyroidism presented with multiple cutaneous lesions developing over the last year. The lesions continued to increase in number but were otherwise asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed approximately 20 rubbery, pink-tan papules measuring less than 1 cm in diameter that were scattered along the trunk (Figure, A), arms, and legs (Figure, B).

The patient had no known history of immunosuppression or rheumatologic disease and was otherwise healthy. Basic laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count and antinuclear antibody titer were within reference range. The lesions were clinically consistent with dermatofibromas, but due to their increasing number within a short period of time, a biopsy of a representative lesion was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

The exact incidence of MEDFs is unknown, but they are rare, with one review finding only 50 cases reported from 1960 to 2002.8 They are increasingly recognized as a sign of potential immune dysregulation. Approximately 56% to 70% of cases are seen in patients with an underlying disease state; 80% are immune mediated.8,9 Interestingly, DS has long been associated with notable immune dysfunction,10,11 with evidence suggesting that trisomy 21 may result in widespread changes in gene expression that can lead to interferon activation.12

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms dermatofibroma and Down, dermatofibroma and Down syndrome, eruptive dermatofibroma and Down syndrome, and multiple dermatofibroma and Down syndrome revealed 6 cases of MEDFs in patients with DS that have been reported since 2005.4-7 An additional report by Honda et al13 described a patient with DS who developed 7 dermatofibromas, but no time frame of development was specified. We reviewed the characteristics of 8 patients with DS with MEDFs, which included our patient (Table). The average age at time of presentation was 39 years (median age, 40 years). Six patients (75%) were female and 2 (25%) were male. Dermatofibromas were reported to appear over the course of months to years. Comorbidities included psoriatic arthritis (treated with methotrexate),6 thyroid disorders (ie, Graves disease),6 hypercholesterolemia,6 hidradenitis suppurativa, long-standing mild lymphopenia (1.4×109/L [reference range, 1.5−4.0×109/L]),4 and acute megakaryoblastic leukemia13 treated 15 years before the appearance of dermatofibromas.

Many dermatologic conditions have been reported at increased rates in individuals with DS, including seborrheic dermatitis, alopecia areata, syringomas, elastosis perforans serpiginosa, cutis marmorata, xerosis, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.14,15 Although drawing conclusions about associations between MEDFs and DS is limited by our small sample size, we have reported this case and reviewed existing cases of MEDFs in DS to highlight a potential association that may be underrecognized or underreported. More evidence is needed to determine the strength of the association between MEDFs and DS, but dermatologists should be aware that MEDFs may be an additional skin finding associated with DS that is related to the syndrome’s immune dysregulation.

To the Editor:

Dermatofibromas (also known as fibrous histiocytomas) are benign fibrous nodules that most often arise as solitary lesions on the lower extremities. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas (MEDFs) are uncommon and have been defined as more than 15 in number1 or 5 to 8 dermatofibromas appearing within 4 months.2 They have been reported in association with a number of conditions of immune dysregulation such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, HIV infection, and leukemia.3 Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas also have been described in patients with Down syndrome (DS).4-7 We report a case of MEDFs in a patient with DS and review the literature on the association between MEDFs and DS.

A 38-year-old woman with DS, hidradenitis suppurativa, and hypothyroidism presented with multiple cutaneous lesions developing over the last year. The lesions continued to increase in number but were otherwise asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed approximately 20 rubbery, pink-tan papules measuring less than 1 cm in diameter that were scattered along the trunk (Figure, A), arms, and legs (Figure, B).

The patient had no known history of immunosuppression or rheumatologic disease and was otherwise healthy. Basic laboratory tests including a complete blood cell count and antinuclear antibody titer were within reference range. The lesions were clinically consistent with dermatofibromas, but due to their increasing number within a short period of time, a biopsy of a representative lesion was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

The exact incidence of MEDFs is unknown, but they are rare, with one review finding only 50 cases reported from 1960 to 2002.8 They are increasingly recognized as a sign of potential immune dysregulation. Approximately 56% to 70% of cases are seen in patients with an underlying disease state; 80% are immune mediated.8,9 Interestingly, DS has long been associated with notable immune dysfunction,10,11 with evidence suggesting that trisomy 21 may result in widespread changes in gene expression that can lead to interferon activation.12

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms dermatofibroma and Down, dermatofibroma and Down syndrome, eruptive dermatofibroma and Down syndrome, and multiple dermatofibroma and Down syndrome revealed 6 cases of MEDFs in patients with DS that have been reported since 2005.4-7 An additional report by Honda et al13 described a patient with DS who developed 7 dermatofibromas, but no time frame of development was specified. We reviewed the characteristics of 8 patients with DS with MEDFs, which included our patient (Table). The average age at time of presentation was 39 years (median age, 40 years). Six patients (75%) were female and 2 (25%) were male. Dermatofibromas were reported to appear over the course of months to years. Comorbidities included psoriatic arthritis (treated with methotrexate),6 thyroid disorders (ie, Graves disease),6 hypercholesterolemia,6 hidradenitis suppurativa, long-standing mild lymphopenia (1.4×109/L [reference range, 1.5−4.0×109/L]),4 and acute megakaryoblastic leukemia13 treated 15 years before the appearance of dermatofibromas.

Many dermatologic conditions have been reported at increased rates in individuals with DS, including seborrheic dermatitis, alopecia areata, syringomas, elastosis perforans serpiginosa, cutis marmorata, xerosis, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis.14,15 Although drawing conclusions about associations between MEDFs and DS is limited by our small sample size, we have reported this case and reviewed existing cases of MEDFs in DS to highlight a potential association that may be underrecognized or underreported. More evidence is needed to determine the strength of the association between MEDFs and DS, but dermatologists should be aware that MEDFs may be an additional skin finding associated with DS that is related to the syndrome’s immune dysregulation.

- Baraf CS, Shapiro L. Multiple histiocytomas: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:588-590.

- Ammirati CT, Mann C, Hornstra IK. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in three men with HIV infection. Dermatology. 1997;4:344-348.

- Zaccaria E, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:723-727.

- Lamb RC, Gangopadhyay M, MacDonald A. Multiple dermatofibromas in Down syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E274-E275.

- Monteagudo B, Álvarez-Fernández JC, Iglesias B, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with Down’s syndrome [article in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:199.

- Monteagudo B, Suárez-Amor O, Cabanillas M, et al. Down syndrome: another cause of immunosuppression associated with multiple eruptive dermatofibroma? [article in Spanish]. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:15.

- Tanaka M, Hoashi T, Serizawa N, et al. Multiple unilaterally localized dermatofibromas in a patient with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2017;44:1074-1076.

- Niiyama S, Katsuoka K, Happle R, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:241-244.

- Her Y, Ku SH, Kim KH. A case of multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a healthy adult. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:539-540.

- Bertotto A, Arcangeli C, Crupi S, et al. T cell response to anti-CD3 antibody in Down’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:1148-1151.

- Kusters MA, Verstegen RH, Gemen EF, et al. Intrinsic defect of the immune system in children with Down syndrome: a review. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:189-193.

- Sullivan KD, Evans D, Pandey A, et al. Trisomy 21 causes changes in the circulating proteome indicative of chronic inflammation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14818.

- Honda M, Tomimura S, de Vega S, et al. Multiple dermatofibromas in a patient with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2016;43:346-348.

- Daneshpazhooh M, Nazemi TM, Bigdeloo L, et al. Mucocutaneous findings in 100 children with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:317-320.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down’s syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Baraf CS, Shapiro L. Multiple histiocytomas: report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:588-590.

- Ammirati CT, Mann C, Hornstra IK. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in three men with HIV infection. Dermatology. 1997;4:344-348.

- Zaccaria E, Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas and immunosuppression: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:723-727.

- Lamb RC, Gangopadhyay M, MacDonald A. Multiple dermatofibromas in Down syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E274-E275.

- Monteagudo B, Álvarez-Fernández JC, Iglesias B, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a patient with Down’s syndrome [article in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:199.

- Monteagudo B, Suárez-Amor O, Cabanillas M, et al. Down syndrome: another cause of immunosuppression associated with multiple eruptive dermatofibroma? [article in Spanish]. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:15.

- Tanaka M, Hoashi T, Serizawa N, et al. Multiple unilaterally localized dermatofibromas in a patient with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2017;44:1074-1076.

- Niiyama S, Katsuoka K, Happle R, et al. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas: a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:241-244.

- Her Y, Ku SH, Kim KH. A case of multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in a healthy adult. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:539-540.

- Bertotto A, Arcangeli C, Crupi S, et al. T cell response to anti-CD3 antibody in Down’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:1148-1151.

- Kusters MA, Verstegen RH, Gemen EF, et al. Intrinsic defect of the immune system in children with Down syndrome: a review. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:189-193.

- Sullivan KD, Evans D, Pandey A, et al. Trisomy 21 causes changes in the circulating proteome indicative of chronic inflammation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14818.

- Honda M, Tomimura S, de Vega S, et al. Multiple dermatofibromas in a patient with Down syndrome. J Dermatol. 2016;43:346-348.

- Daneshpazhooh M, Nazemi TM, Bigdeloo L, et al. Mucocutaneous findings in 100 children with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:317-320.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down’s syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

Practice Points

- Although dermatofibromas are common and benign skin lesions, multiple eruptive dermatofibromas have been associated with a number of underlying conditions, particularly those associated with immune dysregulation.

- The immune dysregulation reported in Down syndrome may explain the appearance of multiple dermatofibromas.

Sun Protection Factor Testing: A Call for an In Vitro Method

The sun protection factor (SPF) value indicates to consumers the level of protection that a given sunscreen formulation provides against erythemally effective UV radiation (UVR). 1 In vivo SPF testing, the gold standard for determining SPF, yields highly variable results and can harm human test participants. 2 In vitro SPF testing methodologies have been under development for years but none have (yet) replaced the in vivo test required by national and international regulatory agencies.

Recent European studies have shown strong data to support a highly standardized in vitro method,1 now under development by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)—potentially to serve as a new SPF determination standard.1,3 Academia and industry should follow this example and actively take steps to develop and validate a suitable replacement for in vivo SPF testing.

In Vivo SPF Testing

The in vivo SPF test involves comparing doses of UVR necessary to induce erythema in human participants with and without sunscreen applied.2 Although this method has long been the standard for SPF determination, it is associated with the following major disadvantages:

- Cost: The in vivo test is expensive.

- Variability: Results of the test are subject to high interlaboratory variability due to the inherent subjectivity of identifying erythema, the variable skin types of human participants, and other laboratory-dependent factors.2 A study found that the average coefficient of variation for SPF values obtained from 3 or 4 laboratories to be 20%—with values exceeding 50% in some cases. With that level of variability, the same sunscreen may be labeled SPF 30, SPF 50, or SPF 50+, thereby posing a health risk to consumers who rely on the accuracy of such claims. In fact, Miksa et al2 concluded that “the largest obstacle to a reliable SPF assessment for consumer health is the in vivo SPF test itself.”

- Ethical concerns: Human participants are intentionally exposed to harmful UVR until sunburn is achieved. For that reason, there have been calls to abandon the practice of in vivo testing.1

Alternatives to In Vivo SPF Testing

There has been international interest in developing in silico and in vitro alternatives to the in vivo SPF test. These options are attractive because they are relatively inexpensive; avoid exposing human participants to harmful UVR; and have the potential to be more accurate and more reproducible than in vivo tests.

In Vitro Protocols—Many such in vitro tests exist; all generally involve applying a layer of sunscreen to an artificial substrate, exposing it to UVR from a solar simulator, and measuring the UVR transmittance through the product and film by spectrophotometry.1 Prior shortcomings of this method have included suboptimal reproducibility, lack of data on substrate and product properties, and lack of demonstrated equivalency to in vivo SPF testing.4

In Silico Protocols—These tests use data on the UV spectra of sunscreen filters, physical characteristics of sunscreen films on skin, and the unique photoinstability of filters to calculate expected UVR transmittance and SPF of sunscreens based on their ingredients.5 Reports have shown high correlation with in vivo values. Results are not subject to random error; reproducibility is theoretically perfect.5

Regulatory Agencies and In Vitro Testing

In the United States, sunscreens are regulated as over-the-counter drugs. In vivo testing is the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved method for determining SPF for labeling purposes.1 In a 2007 Proposed Rule and a 2011 Final Rule, the FDA stated that in vitro SPF tests were an inadequate alternative to in vivo tests because of their shortcomings.4,6

Acknowledging the potential benefits of in vitro testing, the FDA wrote that it would consider in vitro alternatives if equivalency to the in vivo test could be proved.6 The agency has not published an official stance on in vitro SPF testing since those statements in 2007 and 2011. Of note, the FDA deems in vitro testing sufficient for making claims of broad-spectrum coverage.4

In contrast to the regulatory scenario in the United States, Europe regulates sunscreens as cosmetics, and the European Union (EU) has banned animal testing of cosmetics,7 which poses a problem for the development of new sunscreens. It is not surprising, therefore, that in 2006 the European Commission (the executive arm of the EU) published a mandate that in vitro SPF testing methods be actively developed due to ethical concerns associated with in vivo methods.8 In 2017, the International Organization for Standardization released specific validation criteria for proposed in vitro tests to facilitate the eventual approval of such methods.1

Progress of In Vitro Methods

In recent years, advances in in vitro SPF testing methods have addressed shortcomings noted previously by the FDA, which has led to notably improved reproducibility of results and correlation with in vivo values, in large part due to strict standardization of protocols,1 such as tight temperature control of samples, a multisubstrate approach, robotic product application to ensure even distribution, and pre-irradiation of sunscreen samples.

With these improvements, a 2018 study demonstrated an in vitro SPF testing methodology that exceeded published ISO validation criteria for emulsion-type products.1 This method was found to have low interlaboratory variability and high correlation with in vivo SPF values (Pearson r=0.88). Importantly, the authors noted that the consistency and reliability of in vitro SPF testing requires broad institution of a single unified method.1

The method described in the 2018 study1 has been accepted by the ISO Technical Committee and is undergoing further development3

Final Thoughts and Future Steps

Recent data confirm the potential viability of in vitro testing as a primary method of determining SPF values.1 Although ISO has moved forward with development of this method, the FDA has been quiet on in vitro SPF testing since 2011.4 The agency has, however, acknowledged the disadvantages of in vivo broad-spectrum testing, including exposure of human participants to harmful UVR and poor interlaboratory reproducibility.6

Given the technical developments and substantial potential benefits of in vitro testing, we believe that it is time for the FDA to revisit this matter. We propose that the FDA take 2 steps toward in vitro testing. First, publish specific validation criteria that would be deemed necessary for approval of such a test, similar to what ISO published in 2017. Second, thoroughly assess new data supporting the viability of available in vitro testing to determine if the FDA’s stated position that in vitro testing is inadequate remains true.

Although these 2 steps will be important to the process, adoption of an in vitro standard will require more than statements from the FDA. Additional funding should be allocated to researchers who are studying in vitro methodologies, and companies that profit from the multibillion-dollar sunscreen industry should be encouraged to invest in the development of more accurate and more ethical alternatives to in vivo SPF testing.

In vitro SPF testing is inexpensive, avoids the moral quandary of intentionally sunburning human participants, and is more reliable than in vivo testing. It is time for the FDA to facilitate the efforts of academia and industry in taking concrete steps toward approval of an in vitro alternative to in vivo SPF testing.

- Pissavini M, Tricaud C, Wiener G, et al. Validation of an in vitro sun protection factor (SPF) method in blinded ring-testing. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:263-268. doi:10.1111/ics.12459

- Miksa S, Lutz D, Guy C, et al. Sunscreen sun protection factor claim based on in vivo interlaboratory variability. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:541-549. doi:10.1111/ics.12333

- ISO/CD 23675: Cosmetics—sun protection test methods—in vitro determination of sun protection factor. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). July 25, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.iso.org/standard/76616.html

- US Food and Drug Administration. Labeling and effectiveness testing; sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Regist. 2011;76(117):35620-35665. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2011-06-17/pdf/2011-14766.pdf

- Herzog B, Osterwalder U. Simulation of sunscreen performance. Pure Appl Chem. 2015;87:937-951. doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0401

- US Food and Drug Administration. Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; proposed amendment of final monograph. Fed Regist. 2007;72(165):49070-49122. Published August 27, 2007. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2007-08-27/pdf/07-4131.pdf

- Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products. November 30, 2009. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02009R1223-20190813

- European Commission Recommendation 2006/647/EC. Published September 22, 2006. Accessed August 10, 2022. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32006H0647

The sun protection factor (SPF) value indicates to consumers the level of protection that a given sunscreen formulation provides against erythemally effective UV radiation (UVR). 1 In vivo SPF testing, the gold standard for determining SPF, yields highly variable results and can harm human test participants. 2 In vitro SPF testing methodologies have been under development for years but none have (yet) replaced the in vivo test required by national and international regulatory agencies.

Recent European studies have shown strong data to support a highly standardized in vitro method,1 now under development by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)—potentially to serve as a new SPF determination standard.1,3 Academia and industry should follow this example and actively take steps to develop and validate a suitable replacement for in vivo SPF testing.

In Vivo SPF Testing

The in vivo SPF test involves comparing doses of UVR necessary to induce erythema in human participants with and without sunscreen applied.2 Although this method has long been the standard for SPF determination, it is associated with the following major disadvantages:

- Cost: The in vivo test is expensive.

- Variability: Results of the test are subject to high interlaboratory variability due to the inherent subjectivity of identifying erythema, the variable skin types of human participants, and other laboratory-dependent factors.2 A study found that the average coefficient of variation for SPF values obtained from 3 or 4 laboratories to be 20%—with values exceeding 50% in some cases. With that level of variability, the same sunscreen may be labeled SPF 30, SPF 50, or SPF 50+, thereby posing a health risk to consumers who rely on the accuracy of such claims. In fact, Miksa et al2 concluded that “the largest obstacle to a reliable SPF assessment for consumer health is the in vivo SPF test itself.”

- Ethical concerns: Human participants are intentionally exposed to harmful UVR until sunburn is achieved. For that reason, there have been calls to abandon the practice of in vivo testing.1

Alternatives to In Vivo SPF Testing

There has been international interest in developing in silico and in vitro alternatives to the in vivo SPF test. These options are attractive because they are relatively inexpensive; avoid exposing human participants to harmful UVR; and have the potential to be more accurate and more reproducible than in vivo tests.

In Vitro Protocols—Many such in vitro tests exist; all generally involve applying a layer of sunscreen to an artificial substrate, exposing it to UVR from a solar simulator, and measuring the UVR transmittance through the product and film by spectrophotometry.1 Prior shortcomings of this method have included suboptimal reproducibility, lack of data on substrate and product properties, and lack of demonstrated equivalency to in vivo SPF testing.4

In Silico Protocols—These tests use data on the UV spectra of sunscreen filters, physical characteristics of sunscreen films on skin, and the unique photoinstability of filters to calculate expected UVR transmittance and SPF of sunscreens based on their ingredients.5 Reports have shown high correlation with in vivo values. Results are not subject to random error; reproducibility is theoretically perfect.5

Regulatory Agencies and In Vitro Testing

In the United States, sunscreens are regulated as over-the-counter drugs. In vivo testing is the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved method for determining SPF for labeling purposes.1 In a 2007 Proposed Rule and a 2011 Final Rule, the FDA stated that in vitro SPF tests were an inadequate alternative to in vivo tests because of their shortcomings.4,6

Acknowledging the potential benefits of in vitro testing, the FDA wrote that it would consider in vitro alternatives if equivalency to the in vivo test could be proved.6 The agency has not published an official stance on in vitro SPF testing since those statements in 2007 and 2011. Of note, the FDA deems in vitro testing sufficient for making claims of broad-spectrum coverage.4

In contrast to the regulatory scenario in the United States, Europe regulates sunscreens as cosmetics, and the European Union (EU) has banned animal testing of cosmetics,7 which poses a problem for the development of new sunscreens. It is not surprising, therefore, that in 2006 the European Commission (the executive arm of the EU) published a mandate that in vitro SPF testing methods be actively developed due to ethical concerns associated with in vivo methods.8 In 2017, the International Organization for Standardization released specific validation criteria for proposed in vitro tests to facilitate the eventual approval of such methods.1

Progress of In Vitro Methods

In recent years, advances in in vitro SPF testing methods have addressed shortcomings noted previously by the FDA, which has led to notably improved reproducibility of results and correlation with in vivo values, in large part due to strict standardization of protocols,1 such as tight temperature control of samples, a multisubstrate approach, robotic product application to ensure even distribution, and pre-irradiation of sunscreen samples.

With these improvements, a 2018 study demonstrated an in vitro SPF testing methodology that exceeded published ISO validation criteria for emulsion-type products.1 This method was found to have low interlaboratory variability and high correlation with in vivo SPF values (Pearson r=0.88). Importantly, the authors noted that the consistency and reliability of in vitro SPF testing requires broad institution of a single unified method.1

The method described in the 2018 study1 has been accepted by the ISO Technical Committee and is undergoing further development3

Final Thoughts and Future Steps

Recent data confirm the potential viability of in vitro testing as a primary method of determining SPF values.1 Although ISO has moved forward with development of this method, the FDA has been quiet on in vitro SPF testing since 2011.4 The agency has, however, acknowledged the disadvantages of in vivo broad-spectrum testing, including exposure of human participants to harmful UVR and poor interlaboratory reproducibility.6

Given the technical developments and substantial potential benefits of in vitro testing, we believe that it is time for the FDA to revisit this matter. We propose that the FDA take 2 steps toward in vitro testing. First, publish specific validation criteria that would be deemed necessary for approval of such a test, similar to what ISO published in 2017. Second, thoroughly assess new data supporting the viability of available in vitro testing to determine if the FDA’s stated position that in vitro testing is inadequate remains true.

Although these 2 steps will be important to the process, adoption of an in vitro standard will require more than statements from the FDA. Additional funding should be allocated to researchers who are studying in vitro methodologies, and companies that profit from the multibillion-dollar sunscreen industry should be encouraged to invest in the development of more accurate and more ethical alternatives to in vivo SPF testing.

In vitro SPF testing is inexpensive, avoids the moral quandary of intentionally sunburning human participants, and is more reliable than in vivo testing. It is time for the FDA to facilitate the efforts of academia and industry in taking concrete steps toward approval of an in vitro alternative to in vivo SPF testing.

The sun protection factor (SPF) value indicates to consumers the level of protection that a given sunscreen formulation provides against erythemally effective UV radiation (UVR). 1 In vivo SPF testing, the gold standard for determining SPF, yields highly variable results and can harm human test participants. 2 In vitro SPF testing methodologies have been under development for years but none have (yet) replaced the in vivo test required by national and international regulatory agencies.

Recent European studies have shown strong data to support a highly standardized in vitro method,1 now under development by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)—potentially to serve as a new SPF determination standard.1,3 Academia and industry should follow this example and actively take steps to develop and validate a suitable replacement for in vivo SPF testing.

In Vivo SPF Testing

The in vivo SPF test involves comparing doses of UVR necessary to induce erythema in human participants with and without sunscreen applied.2 Although this method has long been the standard for SPF determination, it is associated with the following major disadvantages:

- Cost: The in vivo test is expensive.

- Variability: Results of the test are subject to high interlaboratory variability due to the inherent subjectivity of identifying erythema, the variable skin types of human participants, and other laboratory-dependent factors.2 A study found that the average coefficient of variation for SPF values obtained from 3 or 4 laboratories to be 20%—with values exceeding 50% in some cases. With that level of variability, the same sunscreen may be labeled SPF 30, SPF 50, or SPF 50+, thereby posing a health risk to consumers who rely on the accuracy of such claims. In fact, Miksa et al2 concluded that “the largest obstacle to a reliable SPF assessment for consumer health is the in vivo SPF test itself.”

- Ethical concerns: Human participants are intentionally exposed to harmful UVR until sunburn is achieved. For that reason, there have been calls to abandon the practice of in vivo testing.1

Alternatives to In Vivo SPF Testing

There has been international interest in developing in silico and in vitro alternatives to the in vivo SPF test. These options are attractive because they are relatively inexpensive; avoid exposing human participants to harmful UVR; and have the potential to be more accurate and more reproducible than in vivo tests.

In Vitro Protocols—Many such in vitro tests exist; all generally involve applying a layer of sunscreen to an artificial substrate, exposing it to UVR from a solar simulator, and measuring the UVR transmittance through the product and film by spectrophotometry.1 Prior shortcomings of this method have included suboptimal reproducibility, lack of data on substrate and product properties, and lack of demonstrated equivalency to in vivo SPF testing.4

In Silico Protocols—These tests use data on the UV spectra of sunscreen filters, physical characteristics of sunscreen films on skin, and the unique photoinstability of filters to calculate expected UVR transmittance and SPF of sunscreens based on their ingredients.5 Reports have shown high correlation with in vivo values. Results are not subject to random error; reproducibility is theoretically perfect.5

Regulatory Agencies and In Vitro Testing

In the United States, sunscreens are regulated as over-the-counter drugs. In vivo testing is the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved method for determining SPF for labeling purposes.1 In a 2007 Proposed Rule and a 2011 Final Rule, the FDA stated that in vitro SPF tests were an inadequate alternative to in vivo tests because of their shortcomings.4,6

Acknowledging the potential benefits of in vitro testing, the FDA wrote that it would consider in vitro alternatives if equivalency to the in vivo test could be proved.6 The agency has not published an official stance on in vitro SPF testing since those statements in 2007 and 2011. Of note, the FDA deems in vitro testing sufficient for making claims of broad-spectrum coverage.4

In contrast to the regulatory scenario in the United States, Europe regulates sunscreens as cosmetics, and the European Union (EU) has banned animal testing of cosmetics,7 which poses a problem for the development of new sunscreens. It is not surprising, therefore, that in 2006 the European Commission (the executive arm of the EU) published a mandate that in vitro SPF testing methods be actively developed due to ethical concerns associated with in vivo methods.8 In 2017, the International Organization for Standardization released specific validation criteria for proposed in vitro tests to facilitate the eventual approval of such methods.1

Progress of In Vitro Methods

In recent years, advances in in vitro SPF testing methods have addressed shortcomings noted previously by the FDA, which has led to notably improved reproducibility of results and correlation with in vivo values, in large part due to strict standardization of protocols,1 such as tight temperature control of samples, a multisubstrate approach, robotic product application to ensure even distribution, and pre-irradiation of sunscreen samples.

With these improvements, a 2018 study demonstrated an in vitro SPF testing methodology that exceeded published ISO validation criteria for emulsion-type products.1 This method was found to have low interlaboratory variability and high correlation with in vivo SPF values (Pearson r=0.88). Importantly, the authors noted that the consistency and reliability of in vitro SPF testing requires broad institution of a single unified method.1

The method described in the 2018 study1 has been accepted by the ISO Technical Committee and is undergoing further development3

Final Thoughts and Future Steps

Recent data confirm the potential viability of in vitro testing as a primary method of determining SPF values.1 Although ISO has moved forward with development of this method, the FDA has been quiet on in vitro SPF testing since 2011.4 The agency has, however, acknowledged the disadvantages of in vivo broad-spectrum testing, including exposure of human participants to harmful UVR and poor interlaboratory reproducibility.6

Given the technical developments and substantial potential benefits of in vitro testing, we believe that it is time for the FDA to revisit this matter. We propose that the FDA take 2 steps toward in vitro testing. First, publish specific validation criteria that would be deemed necessary for approval of such a test, similar to what ISO published in 2017. Second, thoroughly assess new data supporting the viability of available in vitro testing to determine if the FDA’s stated position that in vitro testing is inadequate remains true.

Although these 2 steps will be important to the process, adoption of an in vitro standard will require more than statements from the FDA. Additional funding should be allocated to researchers who are studying in vitro methodologies, and companies that profit from the multibillion-dollar sunscreen industry should be encouraged to invest in the development of more accurate and more ethical alternatives to in vivo SPF testing.

In vitro SPF testing is inexpensive, avoids the moral quandary of intentionally sunburning human participants, and is more reliable than in vivo testing. It is time for the FDA to facilitate the efforts of academia and industry in taking concrete steps toward approval of an in vitro alternative to in vivo SPF testing.

- Pissavini M, Tricaud C, Wiener G, et al. Validation of an in vitro sun protection factor (SPF) method in blinded ring-testing. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:263-268. doi:10.1111/ics.12459

- Miksa S, Lutz D, Guy C, et al. Sunscreen sun protection factor claim based on in vivo interlaboratory variability. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:541-549. doi:10.1111/ics.12333

- ISO/CD 23675: Cosmetics—sun protection test methods—in vitro determination of sun protection factor. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). July 25, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.iso.org/standard/76616.html

- US Food and Drug Administration. Labeling and effectiveness testing; sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Regist. 2011;76(117):35620-35665. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2011-06-17/pdf/2011-14766.pdf

- Herzog B, Osterwalder U. Simulation of sunscreen performance. Pure Appl Chem. 2015;87:937-951. doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0401

- US Food and Drug Administration. Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; proposed amendment of final monograph. Fed Regist. 2007;72(165):49070-49122. Published August 27, 2007. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2007-08-27/pdf/07-4131.pdf

- Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products. November 30, 2009. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02009R1223-20190813

- European Commission Recommendation 2006/647/EC. Published September 22, 2006. Accessed August 10, 2022. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32006H0647

- Pissavini M, Tricaud C, Wiener G, et al. Validation of an in vitro sun protection factor (SPF) method in blinded ring-testing. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:263-268. doi:10.1111/ics.12459

- Miksa S, Lutz D, Guy C, et al. Sunscreen sun protection factor claim based on in vivo interlaboratory variability. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:541-549. doi:10.1111/ics.12333

- ISO/CD 23675: Cosmetics—sun protection test methods—in vitro determination of sun protection factor. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). July 25, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.iso.org/standard/76616.html

- US Food and Drug Administration. Labeling and effectiveness testing; sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Regist. 2011;76(117):35620-35665. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2011-06-17/pdf/2011-14766.pdf

- Herzog B, Osterwalder U. Simulation of sunscreen performance. Pure Appl Chem. 2015;87:937-951. doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0401

- US Food and Drug Administration. Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; proposed amendment of final monograph. Fed Regist. 2007;72(165):49070-49122. Published August 27, 2007. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2007-08-27/pdf/07-4131.pdf

- Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products. November 30, 2009. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02009R1223-20190813

- European Commission Recommendation 2006/647/EC. Published September 22, 2006. Accessed August 10, 2022. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32006H0647

Practice Points

- The methodology for determining sun protection factor (SPF) that currently is accepted by the US Food and Drug Administration is an expensive and imprecise in vivo test that exposes human participants to harmful UV radiation.

- In vitro tests for determining SPF may be viable alternatives to the current in vivo gold standard.

- Researchers and the sunscreen industry should actively develop these in vitro methodologies to adopt a more accurate and less harmful test for SPF.

Intralesional Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Therapy for Recalcitrant Plantar Wart Triggers Gout Flare

To the Editor:

There is increasing evidence supporting the use of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in the treatment of recalcitrant common warts.1 We describe a potential complication associated with HPV vaccine treatment of warts that would be of interest to dermatologists.

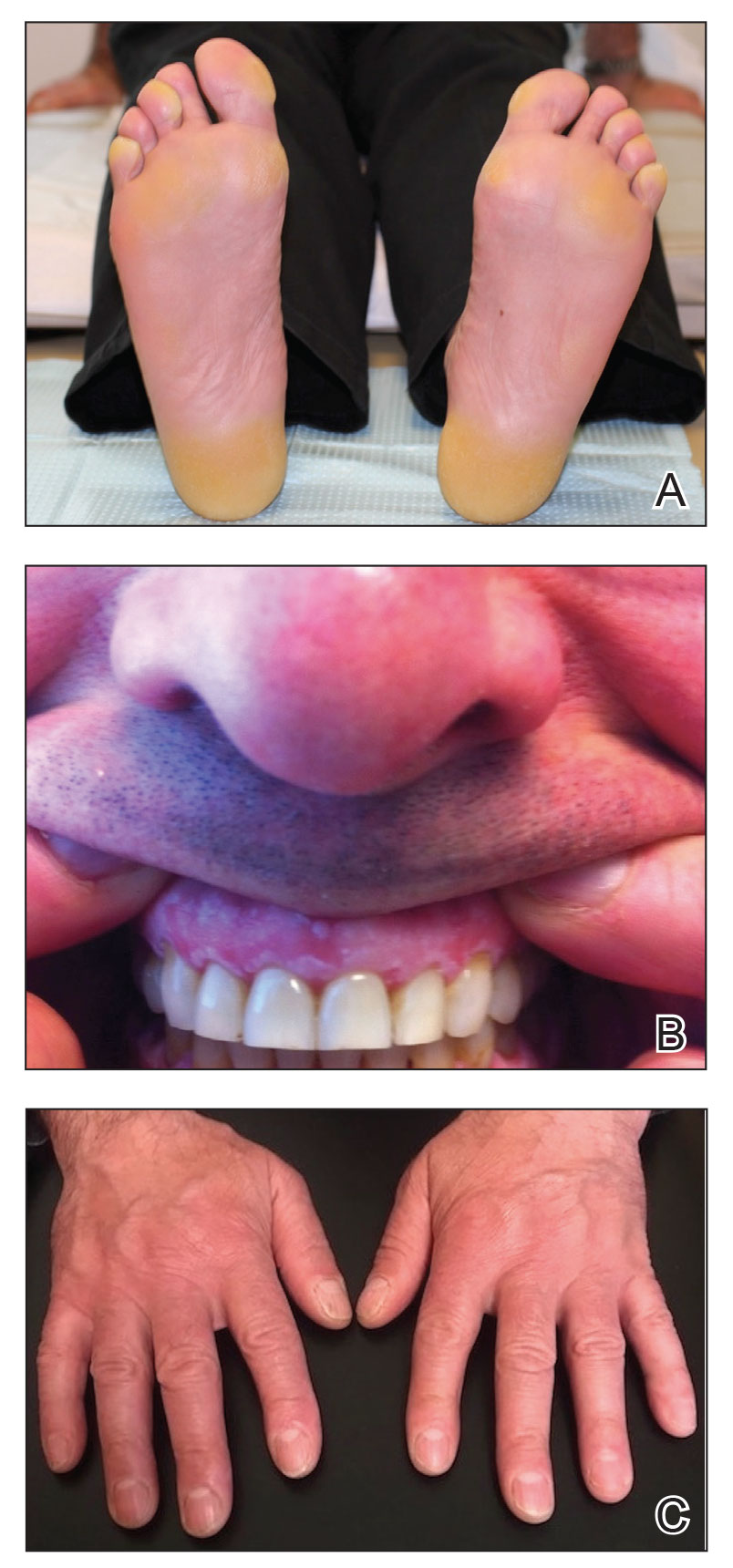

A 70-year-old woman presented with a plantar wart measuring 6 mm in diameter at the base of the right hallux of 5 years’ duration. Prior failed therapies for wart removal included multiple paring treatments, cryotherapy, and topical salicylic acid 40% to 60%. The patient had no notable comorbidities; no history of gout; and no known risk factors for gout, such as hypertension, renal insufficiency, diuretic use, obesity, family history, or trauma.

Prior reports cited effective treatment of recalcitrant warts with recombinant HPV vaccines, both intralesionally1 and intramuscularly.2,3 With this knowledge in mind, we administered an intralesional injection with 0.1-mL recombinant HPV 9-valent vaccine to the patient’s plantar wart. Gradual erythema and swelling of the right first metatarsophalangeal joint developed over the next 7 days. Synovial fluid analysis demonstrated negatively birefringent crystals. The patient commenced treatment with colchicine and indomethacin and improved over the next 5 days. The wart resolved 3 months later and required no further treatment.

Prophylactic quadrivalent HPV vaccines have shown efficacy in treating HPV-associated precancerous and cancerous lesions.4 Case reports have suggested that HPV vaccines may be an effective treatment option for recalcitrant warts,1-3,5 especially in cases that do not respond to traditional treatment. It is possible that the mechanism of wart treatment involves overlap in the antigenic epitopes of the HPV types targeted by the vaccine vs the HPV types responsible for causing warts.2 Papillomaviruslike particles, based on the L1 capsid protein, can induce a specific CD8+ activation signal, leading to a vaccine-induced cytotoxic T-cell response that targets the wart cells with HPV-like antigens.6 The HPV vaccine contains aluminium, which has been shown to activate NLRP3 inflammasome,5 which may trigger gout by increasing monosodium urate crystal deposition via IL-1β production.7 This may lead to an increased risk for gout flares, an adverse effect of the HPV vaccine. This finding is supported by other studies of aluminium-containing vaccines that show an association with gout.6 It is noted that these vaccines are mostly delivered intramuscularly or subcutaneously in some cases.

We reported a case of gout triggered by intralesional HPV vaccine treatment of warts. It is unclear whether the gout was induced by the vaccine itself or whether it was due to trauma caused by the intralesional injection near the joint space. Based on our findings, we recommend that patients receiving intralesional injections for wart treatment be advised of this potential adverse effect, especially if they have risk factors for gout or have a history of gout.

- Nofal A, Marei A, Ibrahim AM et al. Intralesional versus intramuscular bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in the treatment of recalcitrant common warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:94-100.

- Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Recalcitrant cutaneous warts treated with recombinant quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) in a developmentally delayed, 31-year-old white man. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:475-477.

- Daniel BS, Murrell DF. Complete resolution of chronic multiple verruca vulgaris treated with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:370-372.

- Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, et al. Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1838-1847.

- Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O’Connor W, et al. Crucial role for the NALP3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008;453:1122-1166.

- Bellone S, El-Sahwi K, Cocco E, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) virus-like particle L1-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are equally effective as E7-specific CD8+ CTLs in killing autologous HPV-16-positive tumor cells in cervical cancer patients: implications for L1 dendritic cell-based therapeutic vaccines. J Virol. 2009;83:6779-6789.

- Yokose C, McCormick N, Chen C, et al. Risk of gout flares after vaccination: a prospective case cross-over study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1601-1604.

To the Editor:

There is increasing evidence supporting the use of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in the treatment of recalcitrant common warts.1 We describe a potential complication associated with HPV vaccine treatment of warts that would be of interest to dermatologists.

A 70-year-old woman presented with a plantar wart measuring 6 mm in diameter at the base of the right hallux of 5 years’ duration. Prior failed therapies for wart removal included multiple paring treatments, cryotherapy, and topical salicylic acid 40% to 60%. The patient had no notable comorbidities; no history of gout; and no known risk factors for gout, such as hypertension, renal insufficiency, diuretic use, obesity, family history, or trauma.

Prior reports cited effective treatment of recalcitrant warts with recombinant HPV vaccines, both intralesionally1 and intramuscularly.2,3 With this knowledge in mind, we administered an intralesional injection with 0.1-mL recombinant HPV 9-valent vaccine to the patient’s plantar wart. Gradual erythema and swelling of the right first metatarsophalangeal joint developed over the next 7 days. Synovial fluid analysis demonstrated negatively birefringent crystals. The patient commenced treatment with colchicine and indomethacin and improved over the next 5 days. The wart resolved 3 months later and required no further treatment.

Prophylactic quadrivalent HPV vaccines have shown efficacy in treating HPV-associated precancerous and cancerous lesions.4 Case reports have suggested that HPV vaccines may be an effective treatment option for recalcitrant warts,1-3,5 especially in cases that do not respond to traditional treatment. It is possible that the mechanism of wart treatment involves overlap in the antigenic epitopes of the HPV types targeted by the vaccine vs the HPV types responsible for causing warts.2 Papillomaviruslike particles, based on the L1 capsid protein, can induce a specific CD8+ activation signal, leading to a vaccine-induced cytotoxic T-cell response that targets the wart cells with HPV-like antigens.6 The HPV vaccine contains aluminium, which has been shown to activate NLRP3 inflammasome,5 which may trigger gout by increasing monosodium urate crystal deposition via IL-1β production.7 This may lead to an increased risk for gout flares, an adverse effect of the HPV vaccine. This finding is supported by other studies of aluminium-containing vaccines that show an association with gout.6 It is noted that these vaccines are mostly delivered intramuscularly or subcutaneously in some cases.

We reported a case of gout triggered by intralesional HPV vaccine treatment of warts. It is unclear whether the gout was induced by the vaccine itself or whether it was due to trauma caused by the intralesional injection near the joint space. Based on our findings, we recommend that patients receiving intralesional injections for wart treatment be advised of this potential adverse effect, especially if they have risk factors for gout or have a history of gout.

To the Editor:

There is increasing evidence supporting the use of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in the treatment of recalcitrant common warts.1 We describe a potential complication associated with HPV vaccine treatment of warts that would be of interest to dermatologists.

A 70-year-old woman presented with a plantar wart measuring 6 mm in diameter at the base of the right hallux of 5 years’ duration. Prior failed therapies for wart removal included multiple paring treatments, cryotherapy, and topical salicylic acid 40% to 60%. The patient had no notable comorbidities; no history of gout; and no known risk factors for gout, such as hypertension, renal insufficiency, diuretic use, obesity, family history, or trauma.

Prior reports cited effective treatment of recalcitrant warts with recombinant HPV vaccines, both intralesionally1 and intramuscularly.2,3 With this knowledge in mind, we administered an intralesional injection with 0.1-mL recombinant HPV 9-valent vaccine to the patient’s plantar wart. Gradual erythema and swelling of the right first metatarsophalangeal joint developed over the next 7 days. Synovial fluid analysis demonstrated negatively birefringent crystals. The patient commenced treatment with colchicine and indomethacin and improved over the next 5 days. The wart resolved 3 months later and required no further treatment.

Prophylactic quadrivalent HPV vaccines have shown efficacy in treating HPV-associated precancerous and cancerous lesions.4 Case reports have suggested that HPV vaccines may be an effective treatment option for recalcitrant warts,1-3,5 especially in cases that do not respond to traditional treatment. It is possible that the mechanism of wart treatment involves overlap in the antigenic epitopes of the HPV types targeted by the vaccine vs the HPV types responsible for causing warts.2 Papillomaviruslike particles, based on the L1 capsid protein, can induce a specific CD8+ activation signal, leading to a vaccine-induced cytotoxic T-cell response that targets the wart cells with HPV-like antigens.6 The HPV vaccine contains aluminium, which has been shown to activate NLRP3 inflammasome,5 which may trigger gout by increasing monosodium urate crystal deposition via IL-1β production.7 This may lead to an increased risk for gout flares, an adverse effect of the HPV vaccine. This finding is supported by other studies of aluminium-containing vaccines that show an association with gout.6 It is noted that these vaccines are mostly delivered intramuscularly or subcutaneously in some cases.

We reported a case of gout triggered by intralesional HPV vaccine treatment of warts. It is unclear whether the gout was induced by the vaccine itself or whether it was due to trauma caused by the intralesional injection near the joint space. Based on our findings, we recommend that patients receiving intralesional injections for wart treatment be advised of this potential adverse effect, especially if they have risk factors for gout or have a history of gout.

- Nofal A, Marei A, Ibrahim AM et al. Intralesional versus intramuscular bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in the treatment of recalcitrant common warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:94-100.

- Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Recalcitrant cutaneous warts treated with recombinant quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) in a developmentally delayed, 31-year-old white man. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:475-477.

- Daniel BS, Murrell DF. Complete resolution of chronic multiple verruca vulgaris treated with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:370-372.

- Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, et al. Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1838-1847.

- Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O’Connor W, et al. Crucial role for the NALP3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008;453:1122-1166.

- Bellone S, El-Sahwi K, Cocco E, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) virus-like particle L1-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are equally effective as E7-specific CD8+ CTLs in killing autologous HPV-16-positive tumor cells in cervical cancer patients: implications for L1 dendritic cell-based therapeutic vaccines. J Virol. 2009;83:6779-6789.

- Yokose C, McCormick N, Chen C, et al. Risk of gout flares after vaccination: a prospective case cross-over study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1601-1604.

- Nofal A, Marei A, Ibrahim AM et al. Intralesional versus intramuscular bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in the treatment of recalcitrant common warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:94-100.

- Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Recalcitrant cutaneous warts treated with recombinant quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) in a developmentally delayed, 31-year-old white man. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:475-477.

- Daniel BS, Murrell DF. Complete resolution of chronic multiple verruca vulgaris treated with quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:370-372.

- Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, et al. Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1838-1847.

- Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O’Connor W, et al. Crucial role for the NALP3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008;453:1122-1166.

- Bellone S, El-Sahwi K, Cocco E, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) virus-like particle L1-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are equally effective as E7-specific CD8+ CTLs in killing autologous HPV-16-positive tumor cells in cervical cancer patients: implications for L1 dendritic cell-based therapeutic vaccines. J Virol. 2009;83:6779-6789.

- Yokose C, McCormick N, Chen C, et al. Risk of gout flares after vaccination: a prospective case cross-over study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1601-1604.

Practice Points

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines are increasingly used for recalcitrant warts.

- We describe an unreported adverse effect of gout flare following HPV vaccine treatment of plantar wart.

Calcinosis Cutis Associated With Subcutaneous Glatiramer Acetate

To the Editor:

Calcinosis cutis is a condition characterized by the deposition of insoluble calcium salts in the skin. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is the most common type, occurring in previously traumatized skin in the absence of abnormal blood calcium levels. It commonly is seen in patients with connective tissue diseases and is thought to be precipitated by chronic inflammation and vascular hypoxia.1 Herein, we describe a case of calcinosis cutis arising after treatment with subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an agent that is effective for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). Diagnostic workup and treatment modalities for calcinosis cutis in this patient population should be considered in the context of minimizing interruption or discontinuation of this disease-modifying agent.

A 53-year-old woman with a history of relapsing-remitting MS and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with multiple firm asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules on the thighs of 1 year’s duration that were increasing in number. The involved areas were the injection sites of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an immunomodulator for the treatment of MS, which our patient self-administered 3 times weekly. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to white, firm, and nontender nodules on the thighs (Figure). There was no epidermal change, and she had no other skin involvement. A punch biopsy of one of the nodules revealed calcium deposits in collagen bundles of the deep dermis. Calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels were within reference range. She declined further treatment for the calcinosis cutis and opted to continue treatment with glatiramer acetate, as her MS was well controlled on this medication.

Glatiramer acetate is an immunogenic polypeptide injectable that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsing-remitting MS.2 It is composed of synthetic polypeptides and contains 4 naturally occurring amino acids. Glatiramer acetate is administered subcutaneously as 20 mg/mL/d or 40 mg/mL 3 times weekly. Transient injection-site reactions are the most common cutaneous adverse events and include localized edema, induration, erythema, pain, and pruritus.3 There have been multiple reports of lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis as well as embolia cutis medicamentosa (Nicolau syndrome).4,5 Our case of calcinosis cutis related to glatiramer acetate is unique. The mechanism of calcinosis cutis in our patient likely was dystrophic due to tissue damage, rather than due to the injection of a calcium-containing substance. Our patient’s history of SLE is a notable risk factor for the development of calcinosis cutis, likely incited by the trauma occurring with subcutaneous injections.6

The mainstay of treatment for localized calcinosis cutis in the setting of connective tissue disease is surgical excision as well as treatment of the underlying disorder. Potential therapies include calcium channel blockers, warfarin, bisphosphonates, intravenous immunoglobulin, minocycline, colchicine, anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, intralesional corticosteroids, intravenous sodium thiosulfate, and CO2 laser.1,6 Our patient was already on intravenous immunoglobulin for MS and hydroxychloroquine for SLE. In select cases where the patient is asymptomatic and prefers not to pursue treatment, no treatment is necessary.

Although calcinosis cutis may occur in SLE alone, it is uncommon and usually is seen in chronic severe SLE, where calcification usually occurs in the setting of pre-existing cutaneous lupus.4 This case report of calcinosis cutis following treatment with glatiramer acetate highlights some of the cutaneous side effects associated with glatiramer acetate injections and should prompt practitioners to consider dystrophic calcinosis cutis in patients requiring subcutaneous medications, particularly in those with pre-existing connective tissue disease.

- Valenzuela A, Chung L. Calcinosis: pathophysiology and management. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:542-548.

- Copaxone. Prescribing information. Teva Neuroscience, Inc; 2022. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.copaxone.com/globalassets/copaxone/prescribing-information.pdf

- McKeage K. Glatiramer acetate 40 mg/mL in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a review. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:425-432.

- Balak DMW, Hengstman GJD, Çakmak A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with disease-modifying treatment in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1705-1717.

- Watkins CE, Litchfield J, Youngberg G, et al. Glatiramer acetate-induced lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis. Cutis. 2015;95:E26-E30.

- Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1-12.

To the Editor:

Calcinosis cutis is a condition characterized by the deposition of insoluble calcium salts in the skin. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is the most common type, occurring in previously traumatized skin in the absence of abnormal blood calcium levels. It commonly is seen in patients with connective tissue diseases and is thought to be precipitated by chronic inflammation and vascular hypoxia.1 Herein, we describe a case of calcinosis cutis arising after treatment with subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an agent that is effective for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). Diagnostic workup and treatment modalities for calcinosis cutis in this patient population should be considered in the context of minimizing interruption or discontinuation of this disease-modifying agent.

A 53-year-old woman with a history of relapsing-remitting MS and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with multiple firm asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules on the thighs of 1 year’s duration that were increasing in number. The involved areas were the injection sites of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an immunomodulator for the treatment of MS, which our patient self-administered 3 times weekly. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to white, firm, and nontender nodules on the thighs (Figure). There was no epidermal change, and she had no other skin involvement. A punch biopsy of one of the nodules revealed calcium deposits in collagen bundles of the deep dermis. Calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels were within reference range. She declined further treatment for the calcinosis cutis and opted to continue treatment with glatiramer acetate, as her MS was well controlled on this medication.

Glatiramer acetate is an immunogenic polypeptide injectable that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsing-remitting MS.2 It is composed of synthetic polypeptides and contains 4 naturally occurring amino acids. Glatiramer acetate is administered subcutaneously as 20 mg/mL/d or 40 mg/mL 3 times weekly. Transient injection-site reactions are the most common cutaneous adverse events and include localized edema, induration, erythema, pain, and pruritus.3 There have been multiple reports of lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis as well as embolia cutis medicamentosa (Nicolau syndrome).4,5 Our case of calcinosis cutis related to glatiramer acetate is unique. The mechanism of calcinosis cutis in our patient likely was dystrophic due to tissue damage, rather than due to the injection of a calcium-containing substance. Our patient’s history of SLE is a notable risk factor for the development of calcinosis cutis, likely incited by the trauma occurring with subcutaneous injections.6

The mainstay of treatment for localized calcinosis cutis in the setting of connective tissue disease is surgical excision as well as treatment of the underlying disorder. Potential therapies include calcium channel blockers, warfarin, bisphosphonates, intravenous immunoglobulin, minocycline, colchicine, anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, intralesional corticosteroids, intravenous sodium thiosulfate, and CO2 laser.1,6 Our patient was already on intravenous immunoglobulin for MS and hydroxychloroquine for SLE. In select cases where the patient is asymptomatic and prefers not to pursue treatment, no treatment is necessary.

Although calcinosis cutis may occur in SLE alone, it is uncommon and usually is seen in chronic severe SLE, where calcification usually occurs in the setting of pre-existing cutaneous lupus.4 This case report of calcinosis cutis following treatment with glatiramer acetate highlights some of the cutaneous side effects associated with glatiramer acetate injections and should prompt practitioners to consider dystrophic calcinosis cutis in patients requiring subcutaneous medications, particularly in those with pre-existing connective tissue disease.

To the Editor:

Calcinosis cutis is a condition characterized by the deposition of insoluble calcium salts in the skin. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is the most common type, occurring in previously traumatized skin in the absence of abnormal blood calcium levels. It commonly is seen in patients with connective tissue diseases and is thought to be precipitated by chronic inflammation and vascular hypoxia.1 Herein, we describe a case of calcinosis cutis arising after treatment with subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an agent that is effective for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). Diagnostic workup and treatment modalities for calcinosis cutis in this patient population should be considered in the context of minimizing interruption or discontinuation of this disease-modifying agent.

A 53-year-old woman with a history of relapsing-remitting MS and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with multiple firm asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules on the thighs of 1 year’s duration that were increasing in number. The involved areas were the injection sites of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate, an immunomodulator for the treatment of MS, which our patient self-administered 3 times weekly. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored to white, firm, and nontender nodules on the thighs (Figure). There was no epidermal change, and she had no other skin involvement. A punch biopsy of one of the nodules revealed calcium deposits in collagen bundles of the deep dermis. Calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels were within reference range. She declined further treatment for the calcinosis cutis and opted to continue treatment with glatiramer acetate, as her MS was well controlled on this medication.

Glatiramer acetate is an immunogenic polypeptide injectable that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of relapsing-remitting MS.2 It is composed of synthetic polypeptides and contains 4 naturally occurring amino acids. Glatiramer acetate is administered subcutaneously as 20 mg/mL/d or 40 mg/mL 3 times weekly. Transient injection-site reactions are the most common cutaneous adverse events and include localized edema, induration, erythema, pain, and pruritus.3 There have been multiple reports of lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis as well as embolia cutis medicamentosa (Nicolau syndrome).4,5 Our case of calcinosis cutis related to glatiramer acetate is unique. The mechanism of calcinosis cutis in our patient likely was dystrophic due to tissue damage, rather than due to the injection of a calcium-containing substance. Our patient’s history of SLE is a notable risk factor for the development of calcinosis cutis, likely incited by the trauma occurring with subcutaneous injections.6

The mainstay of treatment for localized calcinosis cutis in the setting of connective tissue disease is surgical excision as well as treatment of the underlying disorder. Potential therapies include calcium channel blockers, warfarin, bisphosphonates, intravenous immunoglobulin, minocycline, colchicine, anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, intralesional corticosteroids, intravenous sodium thiosulfate, and CO2 laser.1,6 Our patient was already on intravenous immunoglobulin for MS and hydroxychloroquine for SLE. In select cases where the patient is asymptomatic and prefers not to pursue treatment, no treatment is necessary.

Although calcinosis cutis may occur in SLE alone, it is uncommon and usually is seen in chronic severe SLE, where calcification usually occurs in the setting of pre-existing cutaneous lupus.4 This case report of calcinosis cutis following treatment with glatiramer acetate highlights some of the cutaneous side effects associated with glatiramer acetate injections and should prompt practitioners to consider dystrophic calcinosis cutis in patients requiring subcutaneous medications, particularly in those with pre-existing connective tissue disease.

- Valenzuela A, Chung L. Calcinosis: pathophysiology and management. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:542-548.

- Copaxone. Prescribing information. Teva Neuroscience, Inc; 2022. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.copaxone.com/globalassets/copaxone/prescribing-information.pdf

- McKeage K. Glatiramer acetate 40 mg/mL in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a review. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:425-432.

- Balak DMW, Hengstman GJD, Çakmak A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with disease-modifying treatment in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1705-1717.

- Watkins CE, Litchfield J, Youngberg G, et al. Glatiramer acetate-induced lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis. Cutis. 2015;95:E26-E30.

- Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1-12.

- Valenzuela A, Chung L. Calcinosis: pathophysiology and management. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:542-548.

- Copaxone. Prescribing information. Teva Neuroscience, Inc; 2022. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://www.copaxone.com/globalassets/copaxone/prescribing-information.pdf

- McKeage K. Glatiramer acetate 40 mg/mL in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a review. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:425-432.

- Balak DMW, Hengstman GJD, Çakmak A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events associated with disease-modifying treatment in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1705-1717.

- Watkins CE, Litchfield J, Youngberg G, et al. Glatiramer acetate-induced lobular panniculitis and skin necrosis. Cutis. 2015;95:E26-E30.

- Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1-12.

Practice Points

- Glatiramer acetate is a subcutaneous injection utilized for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, and common adverse effects include injection-site reactions such as calcinosis cutis.

- Development of calcinosis cutis in association with glatiramer acetate is not an indication for medication discontinuation.

- Dermatologists should be aware of this potential association, and treatment should be considered in cases of symptomatic calcinosis cutis.

Rituximab for Acquired Hemophilia A in the Setting of Bullous Pemphigoid

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease characterized by the formation of antihemidesmosomal antibodies, resulting in tense bullae concentrated on the extremities and trunk that often are preceded by a pruritic urticarial phase.1 A rare complication of BP is the subsequent development of acquired hemophilia A. We report a case of BP with associated factor VIII–neutralizing antibodies in a patient who improved with prednisone and rituximab therapy.

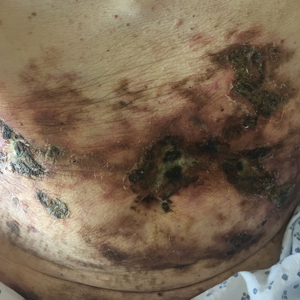

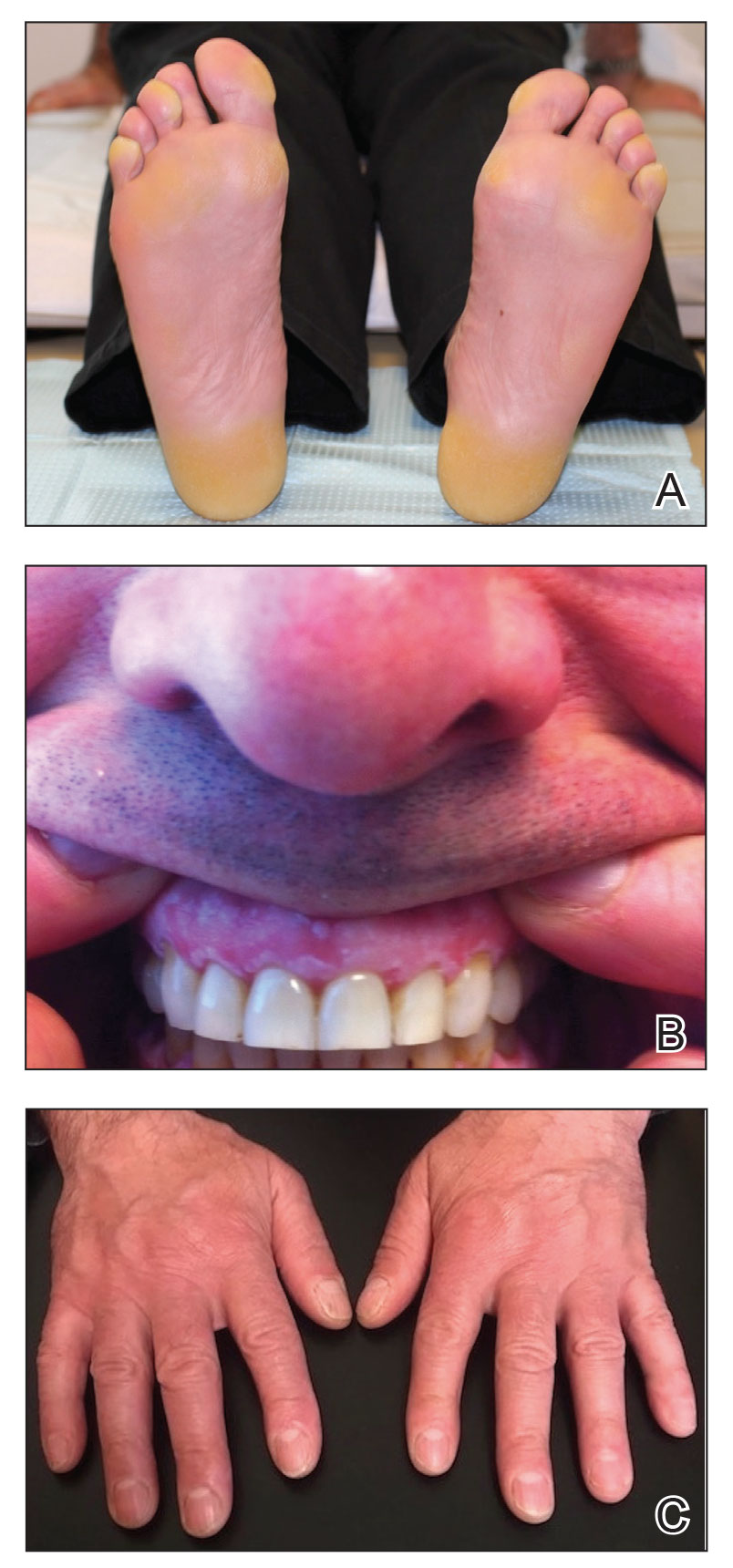

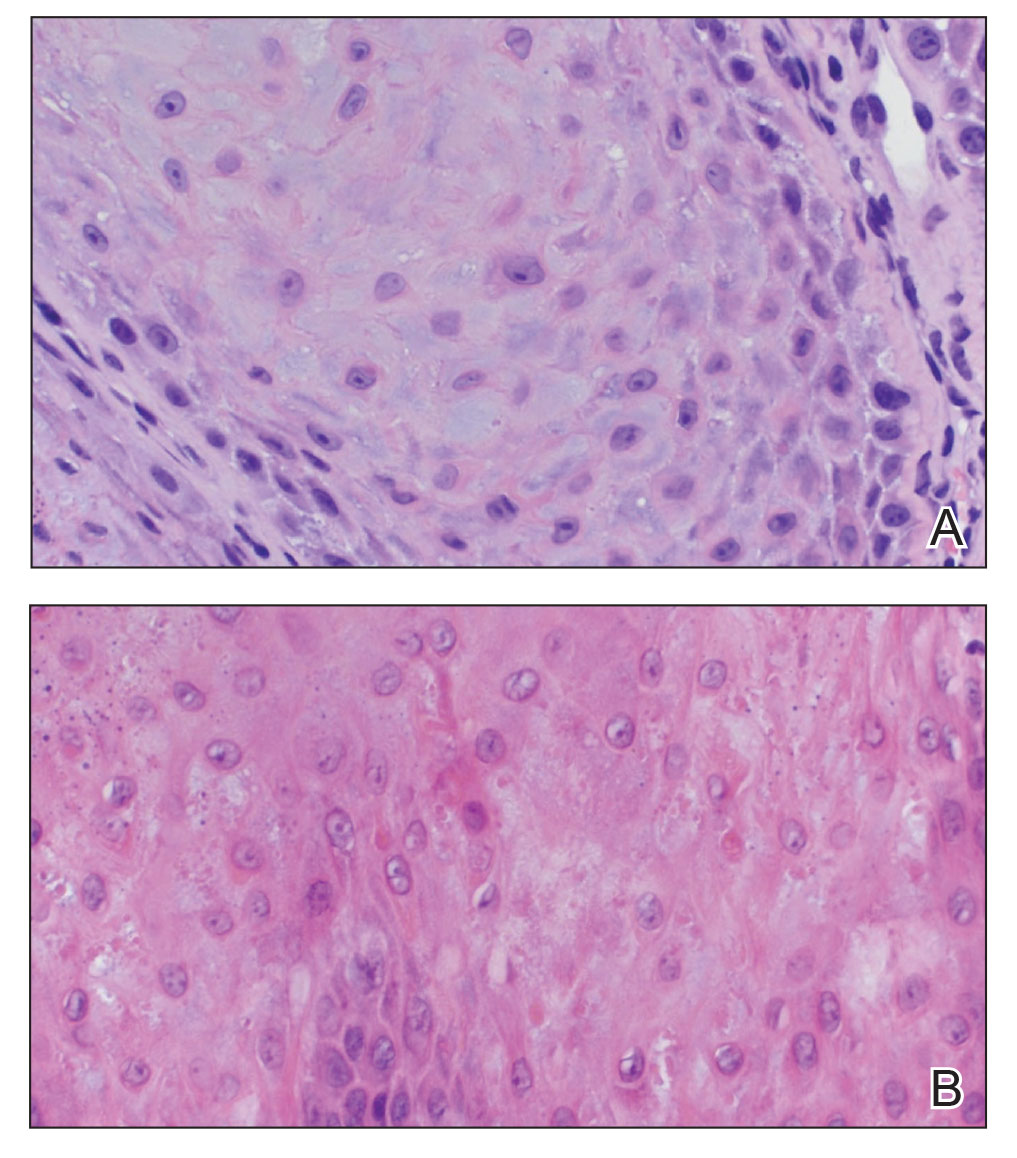

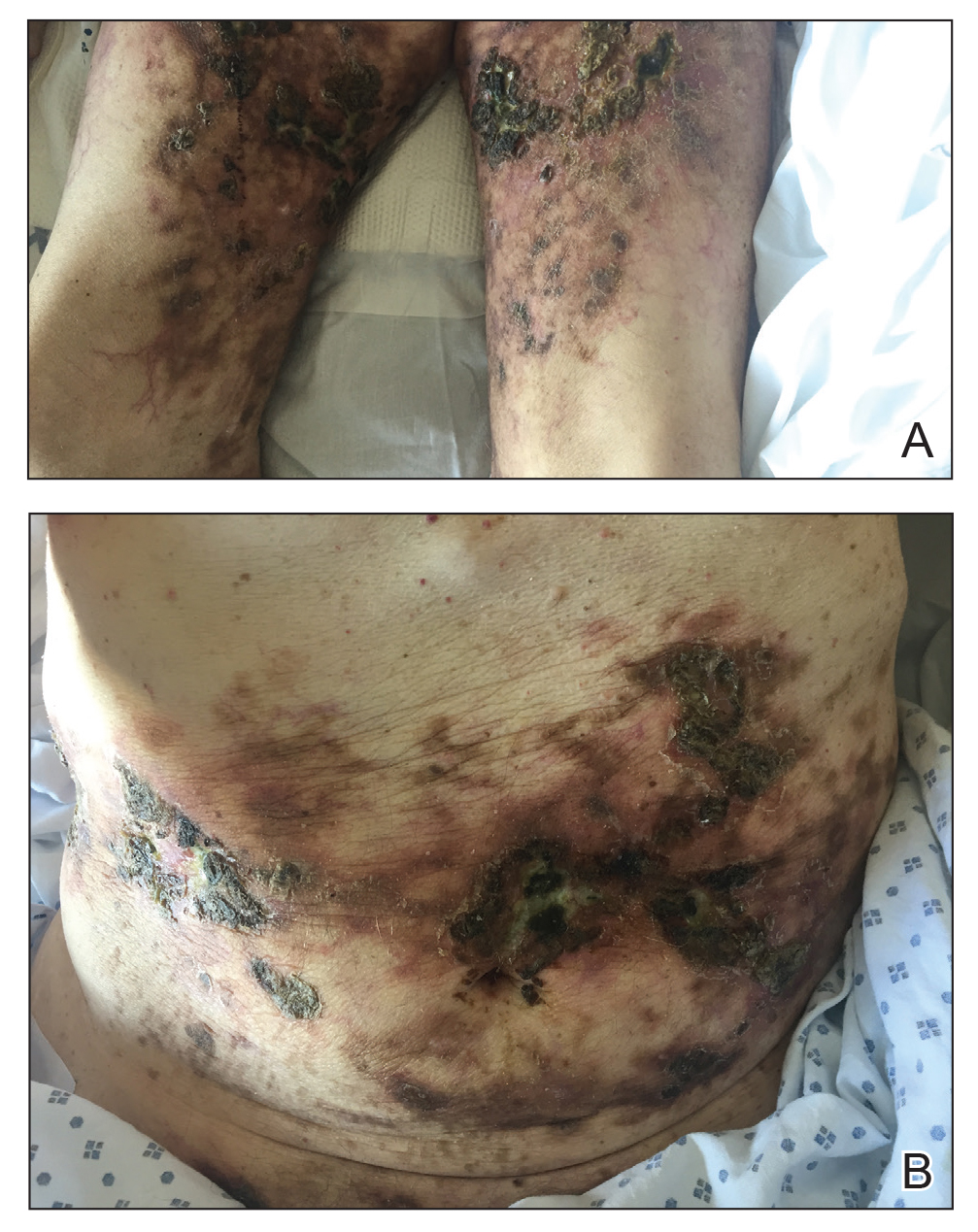

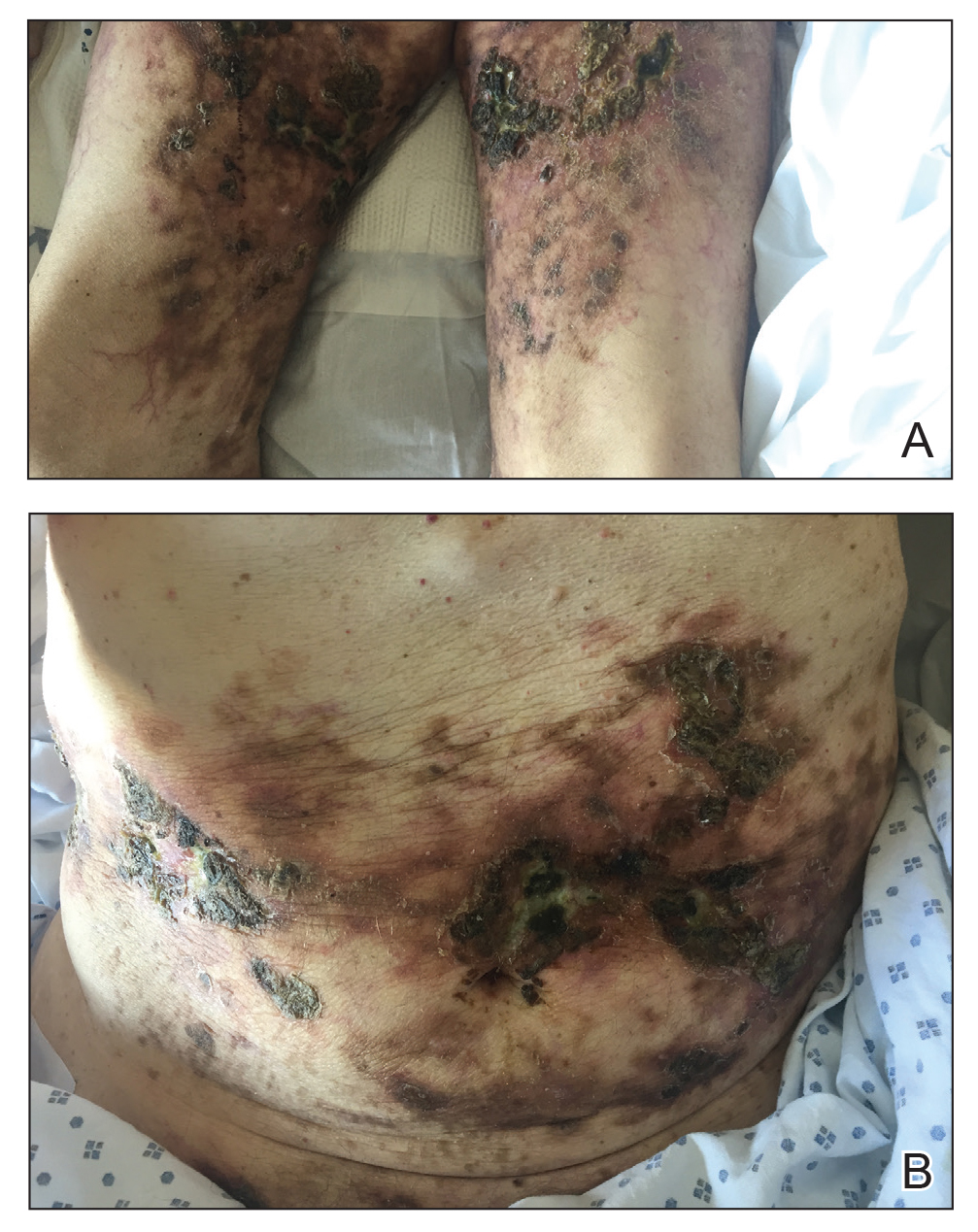

A 78-year-old woman presented with red-orange pruritic plaques on the right heel that spread to involve the arms and legs, abdomen, and trunk with new-onset bullae over the course of 2 weeks (Figure 1). Dermatology was consulted, and a diagnosis of BP was confirmed via biopsy and direct immunofluorescence.

Despite treatment with prednisone 40 mg/d and clobetasol ointment 0.05%, she continued to develop extensive cutaneous bullae and new hemorrhagic bullae on the buccal mucosae (Figure 2), necessitating hospital admission. She clinically improved after prednisone was increased to 60 mg/d and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg twice daily was added; however, she returned 8 days after discharge from the hospital with altered mental status, new-onset hematomas of the abdomen and right leg, and a hemoglobin level of 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). Activated prothrombin time was prolonged without correction on mixing studies, raising concern for coagulation factor inhibition. Factor VIII activity was diminished to 9% and then 1% three days later. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was acutely stabilized with blood transfusions, intravenous immunoglobulin, tranexamic acid, and aminocaproic acid. Rituximab was initiated at 1000 mg and then administered again 2 weeks later. At 7-week follow-up, coagulation studies normalized, and there was no evidence of blistering dermatosis on examination.

Bullous pemphigoid generally is seen in patients older than 60 years, and the incidence increases with age. The disease course follows formation of IgG antibodies against BP180 or BP230, leading to localized activation of the complement cascade at the basement membrane zone.1 Medications, vaccinations, UV radiation, and burns have been implicated in disease induction.2