User login

What’s in a number? 697,633 children with COVID-19

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

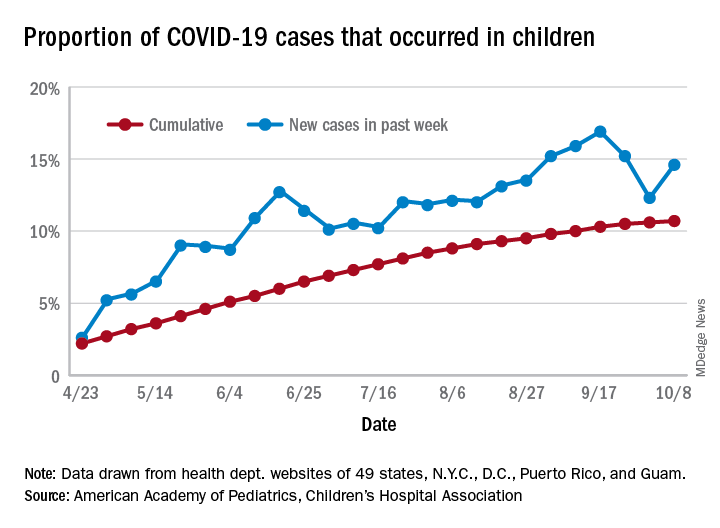

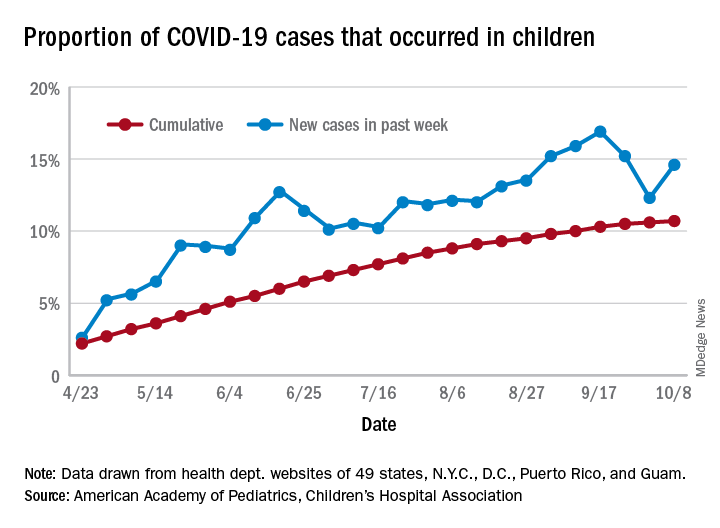

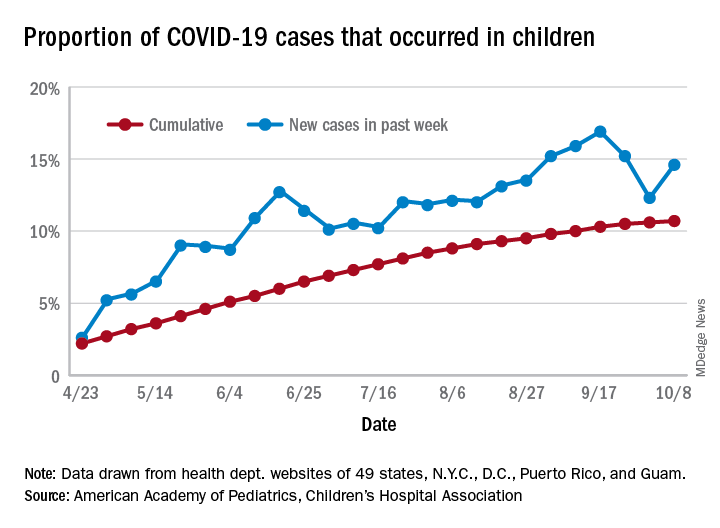

For the week, 14.6% of all COVID-19 cases reported in the United States occurred in children, after 2 consecutive weeks of declines that saw the proportion drop from 16.9% to 12.3%. The cumulative rate of child cases for the entire pandemic is 10.7%, with total child cases in the United States now up to 697,633 and cases among all ages at just over 6.5 million, the AAP and the CHA said Oct. 12 in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Nationally, there were 927 cases reported per 100,000 children as of Oct. 8, with rates at the state level varying from 176 per 100,000 in Vermont to 2,221 per 100,000 in North Dakota. Two other states were over 2,000 cases per 100,000 children: Tennessee (2,155) and South Carolina (2,116), based on data from the health departments of 49 states (New York does not report age distribution), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Severe illness continues to be rare in children, and national (25 states and New York City) hospitalization rates dropped in the last week. The proportion of hospitalizations occurring in children slipped from a pandemic high of 1.8% the previous week to 1.7% during the week of Oct. 8, and the rate of hospitalizations for children with COVID-19 was down to 1.4% from 1.6% the week before and 1.9% on Sept. 3, the AAP and the CHA said.

Mortality data from 42 states and New York City also show a decline. For the third consecutive week, children represented just 0.06% of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States, down from a high of 0.07% on Sept. 17. Only 0.02% of all cases in children have resulted in death, and that figure has been dropping since early June, when it reached 0.06%, according to the AAP/CHA report. As of Oct. 8, there have been 115 total deaths reported in children.

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

For the week, 14.6% of all COVID-19 cases reported in the United States occurred in children, after 2 consecutive weeks of declines that saw the proportion drop from 16.9% to 12.3%. The cumulative rate of child cases for the entire pandemic is 10.7%, with total child cases in the United States now up to 697,633 and cases among all ages at just over 6.5 million, the AAP and the CHA said Oct. 12 in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Nationally, there were 927 cases reported per 100,000 children as of Oct. 8, with rates at the state level varying from 176 per 100,000 in Vermont to 2,221 per 100,000 in North Dakota. Two other states were over 2,000 cases per 100,000 children: Tennessee (2,155) and South Carolina (2,116), based on data from the health departments of 49 states (New York does not report age distribution), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Severe illness continues to be rare in children, and national (25 states and New York City) hospitalization rates dropped in the last week. The proportion of hospitalizations occurring in children slipped from a pandemic high of 1.8% the previous week to 1.7% during the week of Oct. 8, and the rate of hospitalizations for children with COVID-19 was down to 1.4% from 1.6% the week before and 1.9% on Sept. 3, the AAP and the CHA said.

Mortality data from 42 states and New York City also show a decline. For the third consecutive week, children represented just 0.06% of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States, down from a high of 0.07% on Sept. 17. Only 0.02% of all cases in children have resulted in death, and that figure has been dropping since early June, when it reached 0.06%, according to the AAP/CHA report. As of Oct. 8, there have been 115 total deaths reported in children.

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

For the week, 14.6% of all COVID-19 cases reported in the United States occurred in children, after 2 consecutive weeks of declines that saw the proportion drop from 16.9% to 12.3%. The cumulative rate of child cases for the entire pandemic is 10.7%, with total child cases in the United States now up to 697,633 and cases among all ages at just over 6.5 million, the AAP and the CHA said Oct. 12 in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Nationally, there were 927 cases reported per 100,000 children as of Oct. 8, with rates at the state level varying from 176 per 100,000 in Vermont to 2,221 per 100,000 in North Dakota. Two other states were over 2,000 cases per 100,000 children: Tennessee (2,155) and South Carolina (2,116), based on data from the health departments of 49 states (New York does not report age distribution), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Severe illness continues to be rare in children, and national (25 states and New York City) hospitalization rates dropped in the last week. The proportion of hospitalizations occurring in children slipped from a pandemic high of 1.8% the previous week to 1.7% during the week of Oct. 8, and the rate of hospitalizations for children with COVID-19 was down to 1.4% from 1.6% the week before and 1.9% on Sept. 3, the AAP and the CHA said.

Mortality data from 42 states and New York City also show a decline. For the third consecutive week, children represented just 0.06% of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States, down from a high of 0.07% on Sept. 17. Only 0.02% of all cases in children have resulted in death, and that figure has been dropping since early June, when it reached 0.06%, according to the AAP/CHA report. As of Oct. 8, there have been 115 total deaths reported in children.

Flu vaccine significantly cuts pediatric hospitalizations

Unlike previous studies focused on vaccine effectiveness (VE) in ambulatory care office visits, Angela P. Campbell, MD, MPH, and associates have uncovered evidence of the overall benefit influenza vaccines play in reducing hospitalizations and emergency department visits in pediatric influenza patients.

“Our data provide important VE estimates against severe influenza in children,” the researchers noted in Pediatrics, adding that the findings “provide important evidence supporting the annual recommendation that all children 6 months and older should receive influenza vaccination.”

Dr. Campbell and colleagues collected ongoing surveillance data from the New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN), which is a network of pediatric hospitals across seven cities, including Kansas City, Mo.; Rochester, N.Y.; Cincinnati; Pittsburgh; Nashville, Tenn.; Houston; and Seattle. The influenza season encompassed the period Nov. 7, 2018 to June 21, 2019.

A total of 2,748 hospitalized children and 2,676 children who had completed ED visits that did not lead to hospitalization were included. Once those under 6 months were excluded, 1,792 hospitalized children were included in the VE analysis; of these, 226 (13%) tested positive for influenza infection, including 211 (93%) with influenza A viruses and 15 (7%) with influenza B viruses. Fully 1,611 of the patients (90%), had verified vaccine status, while 181 (10%) had solely parental reported vaccine status. The researchers reported 88 (5%) of the patients received mechanical ventilation and 7 (<1%) died.

Most noteworthy, They further estimated a significant reduction in hospitalizations linked to A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, even in the presence of circulating A(H3N2) viruses that differed from the A(H3N2) vaccine component.

Studies from other countries during the same time period showed that while “significant protection against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits and hospitalizations among children infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses” was observed, the same could not be said for protection against A(H3N2) viruses, which varied among pediatric outpatients in the United States (24%), in England (17% outpatient; 31% inpatient), Europe (46%), and Canada (48%). They explained that such variation in vaccine protection is multifactorial, and includes virus-, host-, and environment-related factors. They also noted that regional variations in circulating viruses, host factors including age, imprinting, and previous vaccination could explain the study’s finding of vaccine protection against both A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses.

When comparing VE estimates between ED visits and hospitalizations, the researchers observed one significant difference, that “hospitalized children likely represent more medically complex patients, with 58% having underlying medical conditions and 38% reporting at lease one hospitalization in the past year, compared with 28% and 14% respectively, among ED participants.”

Strengths of the study included the prospective multisite enrollment that provided data across diverse locations and representation from pediatric hospitalizations and ED care, which were not previously strongly represented in the literature. The single-season study with small sample size was considered a limitation, as was the inability to evaluate full and partial vaccine status. Vaccine data also were limited for many of the ED patients observed.

Dr. Campbell and colleagues did caution that while they consider their test-negative design optimal for evaluating both hospitalized and ED patients, they feel their results should not be “interpreted as VE against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits or infections that are not medically attended.”

In a separate interview, Michael E. Pichichero, MD, director of the Rochester General Hospital Research Institute and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), observed: “There are really no surprises here. A well done contemporary study confirms again the benefits of annual influenza vaccinations for children. Viral coinfections involving SARS-CoV-2 and influenza have been reported from Australia to cause heightened illnesses. That observation provides further impetus for parents to have their children receive influenza vaccinations.”

The researchers cited multiple sources of financial support for their ongoing work, including Sanofi, Quidel, Moderna, Karius, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. Funding for this study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Pichichero said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Campbell AP et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1368.

Unlike previous studies focused on vaccine effectiveness (VE) in ambulatory care office visits, Angela P. Campbell, MD, MPH, and associates have uncovered evidence of the overall benefit influenza vaccines play in reducing hospitalizations and emergency department visits in pediatric influenza patients.

“Our data provide important VE estimates against severe influenza in children,” the researchers noted in Pediatrics, adding that the findings “provide important evidence supporting the annual recommendation that all children 6 months and older should receive influenza vaccination.”

Dr. Campbell and colleagues collected ongoing surveillance data from the New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN), which is a network of pediatric hospitals across seven cities, including Kansas City, Mo.; Rochester, N.Y.; Cincinnati; Pittsburgh; Nashville, Tenn.; Houston; and Seattle. The influenza season encompassed the period Nov. 7, 2018 to June 21, 2019.

A total of 2,748 hospitalized children and 2,676 children who had completed ED visits that did not lead to hospitalization were included. Once those under 6 months were excluded, 1,792 hospitalized children were included in the VE analysis; of these, 226 (13%) tested positive for influenza infection, including 211 (93%) with influenza A viruses and 15 (7%) with influenza B viruses. Fully 1,611 of the patients (90%), had verified vaccine status, while 181 (10%) had solely parental reported vaccine status. The researchers reported 88 (5%) of the patients received mechanical ventilation and 7 (<1%) died.

Most noteworthy, They further estimated a significant reduction in hospitalizations linked to A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, even in the presence of circulating A(H3N2) viruses that differed from the A(H3N2) vaccine component.

Studies from other countries during the same time period showed that while “significant protection against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits and hospitalizations among children infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses” was observed, the same could not be said for protection against A(H3N2) viruses, which varied among pediatric outpatients in the United States (24%), in England (17% outpatient; 31% inpatient), Europe (46%), and Canada (48%). They explained that such variation in vaccine protection is multifactorial, and includes virus-, host-, and environment-related factors. They also noted that regional variations in circulating viruses, host factors including age, imprinting, and previous vaccination could explain the study’s finding of vaccine protection against both A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses.

When comparing VE estimates between ED visits and hospitalizations, the researchers observed one significant difference, that “hospitalized children likely represent more medically complex patients, with 58% having underlying medical conditions and 38% reporting at lease one hospitalization in the past year, compared with 28% and 14% respectively, among ED participants.”

Strengths of the study included the prospective multisite enrollment that provided data across diverse locations and representation from pediatric hospitalizations and ED care, which were not previously strongly represented in the literature. The single-season study with small sample size was considered a limitation, as was the inability to evaluate full and partial vaccine status. Vaccine data also were limited for many of the ED patients observed.

Dr. Campbell and colleagues did caution that while they consider their test-negative design optimal for evaluating both hospitalized and ED patients, they feel their results should not be “interpreted as VE against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits or infections that are not medically attended.”

In a separate interview, Michael E. Pichichero, MD, director of the Rochester General Hospital Research Institute and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), observed: “There are really no surprises here. A well done contemporary study confirms again the benefits of annual influenza vaccinations for children. Viral coinfections involving SARS-CoV-2 and influenza have been reported from Australia to cause heightened illnesses. That observation provides further impetus for parents to have their children receive influenza vaccinations.”

The researchers cited multiple sources of financial support for their ongoing work, including Sanofi, Quidel, Moderna, Karius, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. Funding for this study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Pichichero said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Campbell AP et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1368.

Unlike previous studies focused on vaccine effectiveness (VE) in ambulatory care office visits, Angela P. Campbell, MD, MPH, and associates have uncovered evidence of the overall benefit influenza vaccines play in reducing hospitalizations and emergency department visits in pediatric influenza patients.

“Our data provide important VE estimates against severe influenza in children,” the researchers noted in Pediatrics, adding that the findings “provide important evidence supporting the annual recommendation that all children 6 months and older should receive influenza vaccination.”

Dr. Campbell and colleagues collected ongoing surveillance data from the New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN), which is a network of pediatric hospitals across seven cities, including Kansas City, Mo.; Rochester, N.Y.; Cincinnati; Pittsburgh; Nashville, Tenn.; Houston; and Seattle. The influenza season encompassed the period Nov. 7, 2018 to June 21, 2019.

A total of 2,748 hospitalized children and 2,676 children who had completed ED visits that did not lead to hospitalization were included. Once those under 6 months were excluded, 1,792 hospitalized children were included in the VE analysis; of these, 226 (13%) tested positive for influenza infection, including 211 (93%) with influenza A viruses and 15 (7%) with influenza B viruses. Fully 1,611 of the patients (90%), had verified vaccine status, while 181 (10%) had solely parental reported vaccine status. The researchers reported 88 (5%) of the patients received mechanical ventilation and 7 (<1%) died.

Most noteworthy, They further estimated a significant reduction in hospitalizations linked to A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, even in the presence of circulating A(H3N2) viruses that differed from the A(H3N2) vaccine component.

Studies from other countries during the same time period showed that while “significant protection against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits and hospitalizations among children infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses” was observed, the same could not be said for protection against A(H3N2) viruses, which varied among pediatric outpatients in the United States (24%), in England (17% outpatient; 31% inpatient), Europe (46%), and Canada (48%). They explained that such variation in vaccine protection is multifactorial, and includes virus-, host-, and environment-related factors. They also noted that regional variations in circulating viruses, host factors including age, imprinting, and previous vaccination could explain the study’s finding of vaccine protection against both A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses.

When comparing VE estimates between ED visits and hospitalizations, the researchers observed one significant difference, that “hospitalized children likely represent more medically complex patients, with 58% having underlying medical conditions and 38% reporting at lease one hospitalization in the past year, compared with 28% and 14% respectively, among ED participants.”

Strengths of the study included the prospective multisite enrollment that provided data across diverse locations and representation from pediatric hospitalizations and ED care, which were not previously strongly represented in the literature. The single-season study with small sample size was considered a limitation, as was the inability to evaluate full and partial vaccine status. Vaccine data also were limited for many of the ED patients observed.

Dr. Campbell and colleagues did caution that while they consider their test-negative design optimal for evaluating both hospitalized and ED patients, they feel their results should not be “interpreted as VE against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits or infections that are not medically attended.”

In a separate interview, Michael E. Pichichero, MD, director of the Rochester General Hospital Research Institute and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), observed: “There are really no surprises here. A well done contemporary study confirms again the benefits of annual influenza vaccinations for children. Viral coinfections involving SARS-CoV-2 and influenza have been reported from Australia to cause heightened illnesses. That observation provides further impetus for parents to have their children receive influenza vaccinations.”

The researchers cited multiple sources of financial support for their ongoing work, including Sanofi, Quidel, Moderna, Karius, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. Funding for this study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Pichichero said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Campbell AP et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1368.

FROM PEDIATRICS

COVID-19 pandemic amplifies uncertainty for immigrant hospitalists

H1-B visa program needs improvement

Statistics tell the tale of immigrants in the American health care workforce in broad strokes. In an interview, though, one hospitalist shared the particulars of his professional and personal journey since arriving in the United States from India 15 years ago.

Mihir Patel, MD, MPH, FHM, came to the United States in 2005 to complete a Master’s in Public Health. Fifteen years later, he is still waiting for the green card that signifies U.S. permanent residency status. The paperwork for the application, he said, was completed in 2012. Since then, he’s been renewing his H-1B visa every three years, and he has no expectation that anything will change soon.

“If you are from India, which has a significant backlog of green cards – up to 50 years…you just wait forever,” he said. “Many people even die waiting for their green card to arrive.”

Arriving on a student visa, Dr. Patel completed his MPH in 2008 and began an internal medicine residency that same year, holding a J-1 visa for the 3 years of his US residency program.

“Post-residency, I started working in a rural hospital in an underserved area of northeast Tennessee as a hospitalist,” thus completing the 3 years of service in a rural underserved area that’s a requirement for J-1 visa holders, said Dr. Patel. “I loved this rural community hospital so much that I ended up staying there for 6 years. During my work at this rural hospital, I was able to enjoy the autonomy of managing a small ICU, doing both critical care procedures and management of intubated critical patients while working as a hospitalist,” he said. Dr. Patel served as chief of staff at the hospital for two years, and also served on the board of directors for his 400-physician medical group.

“I was a proud member of this rural community – Rogersville,” said Dr. Patel. Although he and his wife, who was completing her hospitalist residency, lived in Johnson City, Tenn., “I did not mind driving 120 miles round trip every day to go to my small-town hospital for 6 years,” he said.

Spending this time in rural Tennessee allowed Dr. Patel to finish the requirements necessary for the Physician National Interest Waiver and submit his application for permanent residency. The waiver, though, doesn’t give him priority status in the waiting list for permanent residency status.

After a stint in northern California to be closer to extended family, the pull of “beautiful northeast Tennesse and the rural community” was too strong, so Dr. Patel and his family moved back to Johnson City in 2018.

Now, Dr. Patel is a hospitalist at Ballad Health System in Johnson City. He is the corporate director of Ballad’s telemedicine program and is now also the medical director of the COVID-19 Strike Team. He co-founded and is president of the Blue Ridge Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Under another H-1B visa, Dr. Patel works part-time from home as a telehospitalist, covering six hospitals in 4 different states.

Even in ordinary circumstances, the H-1B visa comes with constraints. Although Dr. Patel’s 6-year old daughter was born in the U.S. and is a citizen, Dr. Patel and his wife have to reapply for their visas every 3 years. “If we travel outside the U.S., we have to get our visas stamped. We cannot change jobs easily due to fear of visa denial, especially with the recent political environment,” said Dr. Patel. “It feels like we are essential health care workers but non-essential immigrants.”

Having recently completed a physician executive MBA program, Dr. Patel said he’d like to start a business of his own using Lean health care principles and telemedicine to improve rural health care. “But while on an H-1B I cannot do anything outside my sponsored employment,” he said.

Ideally, health care organizations would have high flexibility in how and where staff are deployed when a surge of COVID-19 patients hits. Dr. Patel made the point that visa restrictions can make this much harder: “During this COVID crisis, this restriction can cause significant negative impact for small rural hospitals, where local physicians are quarantined and available physicians are on a visa who cannot legally work outside their primary facilities – even though they are willing to work,” he said. “One cannot even work using telemedicine in the same health system, if that is not specifically mentioned during H-1B petition filling. More than 15,000 physicians who are struck by the green card backlog are in the same situation all over U.S.,” he added.

These constraints, though, pale before the consequences of a worst-case pandemic scenario for an immigrant family, where the physician – the primary visa-holder – becomes disabled or dies. In this case, dependent family members must self-deport. “In addition, there would not be any disability or Social Security benefits for the physician or dependents, as they are not citizens or green card holders and they cannot legally stay in the US,” noted Dr. Patel. “Any hospitalist working during the COVID-19 pandemic can have this fate due to our high exposure risk.”

Reauthorizing the H1-B visa program

SHM has been advocating to improve the H1-B visa system for years, Dr. Patel said, The Fairness for High Skilled Immigrants Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives with bipartisan support, and the Society is advocating for its passage in the Senate.

The Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act (S. 386) simplifies the employment-based immigration system by removing per-country caps, converting the employment-based immigration system into a “first-come, first serve” system that does not discriminate on country of origin. The act will also help alleviate the decades-long green card and permanent residency application backlogs.

Dr. Patel emphasized the importance of action by Congress to reauthorize the physician visa waiver program and expediting physician permanent residency. “This is a crisis and we are all physicians who are ready to serve, regardless of our country of origin. Please let us help this great nation by giving us freedom from visa restrictions and providing security for our families.

“During wartime, all frontline soldiers are naturalized and given citizenship by presidential mandate; this is more than war and we are not asking for citizenship – but at least give us a green card which we have already satisfied all requirements for. If not now, then when?” he asked.

H1-B visa program needs improvement

H1-B visa program needs improvement

Statistics tell the tale of immigrants in the American health care workforce in broad strokes. In an interview, though, one hospitalist shared the particulars of his professional and personal journey since arriving in the United States from India 15 years ago.

Mihir Patel, MD, MPH, FHM, came to the United States in 2005 to complete a Master’s in Public Health. Fifteen years later, he is still waiting for the green card that signifies U.S. permanent residency status. The paperwork for the application, he said, was completed in 2012. Since then, he’s been renewing his H-1B visa every three years, and he has no expectation that anything will change soon.

“If you are from India, which has a significant backlog of green cards – up to 50 years…you just wait forever,” he said. “Many people even die waiting for their green card to arrive.”

Arriving on a student visa, Dr. Patel completed his MPH in 2008 and began an internal medicine residency that same year, holding a J-1 visa for the 3 years of his US residency program.

“Post-residency, I started working in a rural hospital in an underserved area of northeast Tennessee as a hospitalist,” thus completing the 3 years of service in a rural underserved area that’s a requirement for J-1 visa holders, said Dr. Patel. “I loved this rural community hospital so much that I ended up staying there for 6 years. During my work at this rural hospital, I was able to enjoy the autonomy of managing a small ICU, doing both critical care procedures and management of intubated critical patients while working as a hospitalist,” he said. Dr. Patel served as chief of staff at the hospital for two years, and also served on the board of directors for his 400-physician medical group.

“I was a proud member of this rural community – Rogersville,” said Dr. Patel. Although he and his wife, who was completing her hospitalist residency, lived in Johnson City, Tenn., “I did not mind driving 120 miles round trip every day to go to my small-town hospital for 6 years,” he said.

Spending this time in rural Tennessee allowed Dr. Patel to finish the requirements necessary for the Physician National Interest Waiver and submit his application for permanent residency. The waiver, though, doesn’t give him priority status in the waiting list for permanent residency status.

After a stint in northern California to be closer to extended family, the pull of “beautiful northeast Tennesse and the rural community” was too strong, so Dr. Patel and his family moved back to Johnson City in 2018.

Now, Dr. Patel is a hospitalist at Ballad Health System in Johnson City. He is the corporate director of Ballad’s telemedicine program and is now also the medical director of the COVID-19 Strike Team. He co-founded and is president of the Blue Ridge Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Under another H-1B visa, Dr. Patel works part-time from home as a telehospitalist, covering six hospitals in 4 different states.

Even in ordinary circumstances, the H-1B visa comes with constraints. Although Dr. Patel’s 6-year old daughter was born in the U.S. and is a citizen, Dr. Patel and his wife have to reapply for their visas every 3 years. “If we travel outside the U.S., we have to get our visas stamped. We cannot change jobs easily due to fear of visa denial, especially with the recent political environment,” said Dr. Patel. “It feels like we are essential health care workers but non-essential immigrants.”

Having recently completed a physician executive MBA program, Dr. Patel said he’d like to start a business of his own using Lean health care principles and telemedicine to improve rural health care. “But while on an H-1B I cannot do anything outside my sponsored employment,” he said.

Ideally, health care organizations would have high flexibility in how and where staff are deployed when a surge of COVID-19 patients hits. Dr. Patel made the point that visa restrictions can make this much harder: “During this COVID crisis, this restriction can cause significant negative impact for small rural hospitals, where local physicians are quarantined and available physicians are on a visa who cannot legally work outside their primary facilities – even though they are willing to work,” he said. “One cannot even work using telemedicine in the same health system, if that is not specifically mentioned during H-1B petition filling. More than 15,000 physicians who are struck by the green card backlog are in the same situation all over U.S.,” he added.

These constraints, though, pale before the consequences of a worst-case pandemic scenario for an immigrant family, where the physician – the primary visa-holder – becomes disabled or dies. In this case, dependent family members must self-deport. “In addition, there would not be any disability or Social Security benefits for the physician or dependents, as they are not citizens or green card holders and they cannot legally stay in the US,” noted Dr. Patel. “Any hospitalist working during the COVID-19 pandemic can have this fate due to our high exposure risk.”

Reauthorizing the H1-B visa program

SHM has been advocating to improve the H1-B visa system for years, Dr. Patel said, The Fairness for High Skilled Immigrants Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives with bipartisan support, and the Society is advocating for its passage in the Senate.

The Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act (S. 386) simplifies the employment-based immigration system by removing per-country caps, converting the employment-based immigration system into a “first-come, first serve” system that does not discriminate on country of origin. The act will also help alleviate the decades-long green card and permanent residency application backlogs.

Dr. Patel emphasized the importance of action by Congress to reauthorize the physician visa waiver program and expediting physician permanent residency. “This is a crisis and we are all physicians who are ready to serve, regardless of our country of origin. Please let us help this great nation by giving us freedom from visa restrictions and providing security for our families.

“During wartime, all frontline soldiers are naturalized and given citizenship by presidential mandate; this is more than war and we are not asking for citizenship – but at least give us a green card which we have already satisfied all requirements for. If not now, then when?” he asked.

Statistics tell the tale of immigrants in the American health care workforce in broad strokes. In an interview, though, one hospitalist shared the particulars of his professional and personal journey since arriving in the United States from India 15 years ago.

Mihir Patel, MD, MPH, FHM, came to the United States in 2005 to complete a Master’s in Public Health. Fifteen years later, he is still waiting for the green card that signifies U.S. permanent residency status. The paperwork for the application, he said, was completed in 2012. Since then, he’s been renewing his H-1B visa every three years, and he has no expectation that anything will change soon.

“If you are from India, which has a significant backlog of green cards – up to 50 years…you just wait forever,” he said. “Many people even die waiting for their green card to arrive.”

Arriving on a student visa, Dr. Patel completed his MPH in 2008 and began an internal medicine residency that same year, holding a J-1 visa for the 3 years of his US residency program.

“Post-residency, I started working in a rural hospital in an underserved area of northeast Tennessee as a hospitalist,” thus completing the 3 years of service in a rural underserved area that’s a requirement for J-1 visa holders, said Dr. Patel. “I loved this rural community hospital so much that I ended up staying there for 6 years. During my work at this rural hospital, I was able to enjoy the autonomy of managing a small ICU, doing both critical care procedures and management of intubated critical patients while working as a hospitalist,” he said. Dr. Patel served as chief of staff at the hospital for two years, and also served on the board of directors for his 400-physician medical group.

“I was a proud member of this rural community – Rogersville,” said Dr. Patel. Although he and his wife, who was completing her hospitalist residency, lived in Johnson City, Tenn., “I did not mind driving 120 miles round trip every day to go to my small-town hospital for 6 years,” he said.

Spending this time in rural Tennessee allowed Dr. Patel to finish the requirements necessary for the Physician National Interest Waiver and submit his application for permanent residency. The waiver, though, doesn’t give him priority status in the waiting list for permanent residency status.

After a stint in northern California to be closer to extended family, the pull of “beautiful northeast Tennesse and the rural community” was too strong, so Dr. Patel and his family moved back to Johnson City in 2018.

Now, Dr. Patel is a hospitalist at Ballad Health System in Johnson City. He is the corporate director of Ballad’s telemedicine program and is now also the medical director of the COVID-19 Strike Team. He co-founded and is president of the Blue Ridge Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Under another H-1B visa, Dr. Patel works part-time from home as a telehospitalist, covering six hospitals in 4 different states.

Even in ordinary circumstances, the H-1B visa comes with constraints. Although Dr. Patel’s 6-year old daughter was born in the U.S. and is a citizen, Dr. Patel and his wife have to reapply for their visas every 3 years. “If we travel outside the U.S., we have to get our visas stamped. We cannot change jobs easily due to fear of visa denial, especially with the recent political environment,” said Dr. Patel. “It feels like we are essential health care workers but non-essential immigrants.”

Having recently completed a physician executive MBA program, Dr. Patel said he’d like to start a business of his own using Lean health care principles and telemedicine to improve rural health care. “But while on an H-1B I cannot do anything outside my sponsored employment,” he said.

Ideally, health care organizations would have high flexibility in how and where staff are deployed when a surge of COVID-19 patients hits. Dr. Patel made the point that visa restrictions can make this much harder: “During this COVID crisis, this restriction can cause significant negative impact for small rural hospitals, where local physicians are quarantined and available physicians are on a visa who cannot legally work outside their primary facilities – even though they are willing to work,” he said. “One cannot even work using telemedicine in the same health system, if that is not specifically mentioned during H-1B petition filling. More than 15,000 physicians who are struck by the green card backlog are in the same situation all over U.S.,” he added.

These constraints, though, pale before the consequences of a worst-case pandemic scenario for an immigrant family, where the physician – the primary visa-holder – becomes disabled or dies. In this case, dependent family members must self-deport. “In addition, there would not be any disability or Social Security benefits for the physician or dependents, as they are not citizens or green card holders and they cannot legally stay in the US,” noted Dr. Patel. “Any hospitalist working during the COVID-19 pandemic can have this fate due to our high exposure risk.”

Reauthorizing the H1-B visa program

SHM has been advocating to improve the H1-B visa system for years, Dr. Patel said, The Fairness for High Skilled Immigrants Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives with bipartisan support, and the Society is advocating for its passage in the Senate.

The Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act (S. 386) simplifies the employment-based immigration system by removing per-country caps, converting the employment-based immigration system into a “first-come, first serve” system that does not discriminate on country of origin. The act will also help alleviate the decades-long green card and permanent residency application backlogs.

Dr. Patel emphasized the importance of action by Congress to reauthorize the physician visa waiver program and expediting physician permanent residency. “This is a crisis and we are all physicians who are ready to serve, regardless of our country of origin. Please let us help this great nation by giving us freedom from visa restrictions and providing security for our families.

“During wartime, all frontline soldiers are naturalized and given citizenship by presidential mandate; this is more than war and we are not asking for citizenship – but at least give us a green card which we have already satisfied all requirements for. If not now, then when?” he asked.

‘Profound human toll’ in excess deaths from COVID-19 calculated in two studies

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fourteen-day sports hiatus recommended for children after COVID-19

Children should not return to sports for 14 days after exposure to COVID-19, and those with moderate symptoms should undergo an electrocardiogram before returning, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

said Susannah Briskin, MD, a pediatric sports medicine specialist at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland.

“There has been emerging evidence about cases of myocarditis occurring in athletes, including athletes who are asymptomatic with COVID-19,” she said in an interview.

The update aligns the AAP recommendations with those from the American College of Cardiologists, she added.

Recent imaging studies have turned up signs of myocarditis in athletes recovering from mild or asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 and have prompted calls for clearer guidelines about imaging studies and return to play.

Viral myocarditis poses a risk to athletes because it can lead to potentially fatal arrhythmias, Dr. Briskin said.

Although children benefit from participating in sports, these activities also put them at risk of contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to others, the guidance noted.

To balance the risks and benefits, the academy proposed guidelines that vary depending on the severity of the presentation.

In the first category are patients with a severe presentation (hypotension, arrhythmias, need for intubation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, kidney or cardiac failure) or with multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Clinicians should treat these patients as though they have myocarditis. Patients should be restricted from engaging in sports and other exercise for 3-6 months, the guidance stated.

The primary care physician and “appropriate pediatric medical subspecialist, preferably in consultation with a pediatric cardiologist,” should clear them before they return to activities. In examining patients for return to play, clinicians should focus on cardiac symptoms, including chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, palpitations, or syncope, the guidance said.

In another category are patients with cardiac symptoms, those with concerning findings on examination, and those with moderate symptoms of COVID-19, including prolonged fever. These patients should undergo an ECG and possibly be referred to a pediatric cardiologist, the guidelines said. These symptoms must be absent for at least 14 days before these patients can return to sports, and the athletes should obtain clearance from their primary care physicians before they resume.

In a third category are patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or who have had close contact with someone who was infected but who have not themselves experienced symptoms. These athletes should refrain from sports for at least 14 days, the guidelines said.

Children who don’t fall into any of these categories should not be tested for the virus or antibodies to it before participation in sports, the academy said.

The guidelines don’t vary depending on the sport. But the academy has issued separate guidance for parents and guardians to help them evaluate the risk for COVID-19 transmission by sport.

Athletes participating in “sports that have greater amount of contact time or proximity to people would be at higher risk for contracting COVID-19,” Dr. Briskin said. “But I think that’s all fairly common sense, given the recommendations for non–sport-related activity just in terms of social distancing and masking.”

The new guidance called on sports organizers to minimize contact by, for example, modifying drills and conditioning. It recommended that athletes wear masks except during vigorous exercise or when participating in water sports, as well as in other circumstances in which the mask could become a safety hazard.

They also recommended using handwashing stations or hand sanitizer, avoiding contact with shared surfaces, and avoiding small rooms and areas with poor ventilation.

Dr. Briskin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Children should not return to sports for 14 days after exposure to COVID-19, and those with moderate symptoms should undergo an electrocardiogram before returning, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

said Susannah Briskin, MD, a pediatric sports medicine specialist at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland.

“There has been emerging evidence about cases of myocarditis occurring in athletes, including athletes who are asymptomatic with COVID-19,” she said in an interview.

The update aligns the AAP recommendations with those from the American College of Cardiologists, she added.

Recent imaging studies have turned up signs of myocarditis in athletes recovering from mild or asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 and have prompted calls for clearer guidelines about imaging studies and return to play.

Viral myocarditis poses a risk to athletes because it can lead to potentially fatal arrhythmias, Dr. Briskin said.

Although children benefit from participating in sports, these activities also put them at risk of contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to others, the guidance noted.

To balance the risks and benefits, the academy proposed guidelines that vary depending on the severity of the presentation.

In the first category are patients with a severe presentation (hypotension, arrhythmias, need for intubation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, kidney or cardiac failure) or with multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Clinicians should treat these patients as though they have myocarditis. Patients should be restricted from engaging in sports and other exercise for 3-6 months, the guidance stated.

The primary care physician and “appropriate pediatric medical subspecialist, preferably in consultation with a pediatric cardiologist,” should clear them before they return to activities. In examining patients for return to play, clinicians should focus on cardiac symptoms, including chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, palpitations, or syncope, the guidance said.

In another category are patients with cardiac symptoms, those with concerning findings on examination, and those with moderate symptoms of COVID-19, including prolonged fever. These patients should undergo an ECG and possibly be referred to a pediatric cardiologist, the guidelines said. These symptoms must be absent for at least 14 days before these patients can return to sports, and the athletes should obtain clearance from their primary care physicians before they resume.

In a third category are patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or who have had close contact with someone who was infected but who have not themselves experienced symptoms. These athletes should refrain from sports for at least 14 days, the guidelines said.

Children who don’t fall into any of these categories should not be tested for the virus or antibodies to it before participation in sports, the academy said.

The guidelines don’t vary depending on the sport. But the academy has issued separate guidance for parents and guardians to help them evaluate the risk for COVID-19 transmission by sport.

Athletes participating in “sports that have greater amount of contact time or proximity to people would be at higher risk for contracting COVID-19,” Dr. Briskin said. “But I think that’s all fairly common sense, given the recommendations for non–sport-related activity just in terms of social distancing and masking.”

The new guidance called on sports organizers to minimize contact by, for example, modifying drills and conditioning. It recommended that athletes wear masks except during vigorous exercise or when participating in water sports, as well as in other circumstances in which the mask could become a safety hazard.

They also recommended using handwashing stations or hand sanitizer, avoiding contact with shared surfaces, and avoiding small rooms and areas with poor ventilation.

Dr. Briskin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Children should not return to sports for 14 days after exposure to COVID-19, and those with moderate symptoms should undergo an electrocardiogram before returning, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

said Susannah Briskin, MD, a pediatric sports medicine specialist at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland.

“There has been emerging evidence about cases of myocarditis occurring in athletes, including athletes who are asymptomatic with COVID-19,” she said in an interview.

The update aligns the AAP recommendations with those from the American College of Cardiologists, she added.

Recent imaging studies have turned up signs of myocarditis in athletes recovering from mild or asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 and have prompted calls for clearer guidelines about imaging studies and return to play.

Viral myocarditis poses a risk to athletes because it can lead to potentially fatal arrhythmias, Dr. Briskin said.

Although children benefit from participating in sports, these activities also put them at risk of contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to others, the guidance noted.

To balance the risks and benefits, the academy proposed guidelines that vary depending on the severity of the presentation.

In the first category are patients with a severe presentation (hypotension, arrhythmias, need for intubation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, kidney or cardiac failure) or with multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Clinicians should treat these patients as though they have myocarditis. Patients should be restricted from engaging in sports and other exercise for 3-6 months, the guidance stated.

The primary care physician and “appropriate pediatric medical subspecialist, preferably in consultation with a pediatric cardiologist,” should clear them before they return to activities. In examining patients for return to play, clinicians should focus on cardiac symptoms, including chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, palpitations, or syncope, the guidance said.

In another category are patients with cardiac symptoms, those with concerning findings on examination, and those with moderate symptoms of COVID-19, including prolonged fever. These patients should undergo an ECG and possibly be referred to a pediatric cardiologist, the guidelines said. These symptoms must be absent for at least 14 days before these patients can return to sports, and the athletes should obtain clearance from their primary care physicians before they resume.

In a third category are patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or who have had close contact with someone who was infected but who have not themselves experienced symptoms. These athletes should refrain from sports for at least 14 days, the guidelines said.

Children who don’t fall into any of these categories should not be tested for the virus or antibodies to it before participation in sports, the academy said.

The guidelines don’t vary depending on the sport. But the academy has issued separate guidance for parents and guardians to help them evaluate the risk for COVID-19 transmission by sport.

Athletes participating in “sports that have greater amount of contact time or proximity to people would be at higher risk for contracting COVID-19,” Dr. Briskin said. “But I think that’s all fairly common sense, given the recommendations for non–sport-related activity just in terms of social distancing and masking.”

The new guidance called on sports organizers to minimize contact by, for example, modifying drills and conditioning. It recommended that athletes wear masks except during vigorous exercise or when participating in water sports, as well as in other circumstances in which the mask could become a safety hazard.

They also recommended using handwashing stations or hand sanitizer, avoiding contact with shared surfaces, and avoiding small rooms and areas with poor ventilation.

Dr. Briskin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital leadership lessons in the era of COVID-19

The year 2020 has brought the COVID-19 pandemic and civil unrest and protests, which have resulted in unprecedented health care challenges to hospitals and clinics. The daunting prospect of a fall influenza season has hospital staff and administrators looking ahead to still greater challenges.

This year of crisis has put even greater emphasis on leadership in hospitals, as patients, clinicians, and staff look for direction in the face of uncertainty and stress. But hospital leaders often arrive at their positions unprepared for their roles, according to Leonard Marcus, PhD, director of the Program for Health Care Negotiation and Conflict Resolution at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston.

“Many times what happens in medicine is that someone with the greatest technical skills or greatest clinical skills emerges to be leader of a department, or a group, or a hospital, without having really paid attention to how they can build their leadership skills,” Dr. Marcus said during the 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine Leadership Virtual Seminar, held online Sept. 16-17.

Over 2 days, Dr. Marcus discussed the complex environments faced by hospital leaders, and some of the tools and strategies that can be used to maintain calm, problem-solve, and chart a course ahead.

He emphasized that hospitals and medical systems are complex, nonlinear organizations, which could be swept up by change in the form of mergers, financial policies, patient surges due to local emergencies, or pandemics.

“Complexity has to be central to how you think about leadership. If you think you can control everything, that doesn’t work that well,” said Dr. Marcus.

Most think of leadership as hierarchical, with a boss on top and underlings below, though this is starting to change. Dr. Marcus suggested a different view. Instead of just “leading down” to those who report to them, leaders should consider “leading up” to their own bosses or oversight committees, and across to other departments or even beyond to interlinked organizations such as nursing homes.

“Being able to build that connectivity not only within your hospital, but beyond your hospital, lets you see the chain that goes through the experience of any patient. You are looking at the problem from a much wider lens. We call this meta-leadership,” Dr. Marcus said.