User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

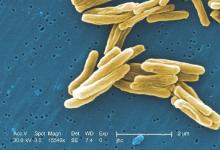

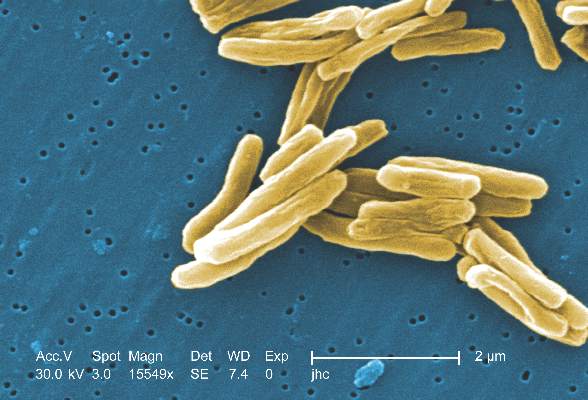

Number of TB-caused deaths fall, but disease still kills 1 million-plus

Tuberculosis (TB) mortality has fallen 47% since 1990, and the reporting on incidences of the disease has improved, says a global report by the World Health Organization (WHO). News about this disease is not all positive, however; TB continues to be one of the world’s deadliest diseases and many cases of TB went unreported last year, according to the WHO report.

Most improvements in mortality rate for TB patients occurred at the beginning of the 21st century, when the United Nations established the Millennium Development Goals, says the report. Such goals included halting and reversing TB incidence on a worldwide basis, in each of the 6 WHO regions, and in 16 of the 22 high-burden countries that collectively account for 80% of TB cases.

“In all, effective diagnosis and treatment of TB saved an estimated 43 million lives between 2000 and 2014,” says the report.

Better reporting on TB’s prevalence led to the first increase in the number of TB cases reported since 2007.

“The annual total of new TB cases, which had been about 5.7 million until 2013, rose to slightly more than 6 million in 2014 (an increase of 6%). This was mostly due to a 29% increase in notification in India, which followed the introduction of a policy of mandatory notification in May 2012, creation of a national Web-based reporting system in June 2012, and intensified efforts to engage the private health sector,” according to the report.

Despite these improvements in data collection of TB incidents, 37% of new TB cases were undiagnosed or not reported last year, with 9.6 million people having fallen sick to TB during a year when just 6 million new cases were reported, according to estimates. Regarding multidrug-resistant TB cases specifically, only 123,000 of an estimated 480,000 cases were detected and reported.

As for the deadliness of the disease, TB killed 1.5 million people in 2014.

Read the full report on the WHO website.

Tuberculosis (TB) mortality has fallen 47% since 1990, and the reporting on incidences of the disease has improved, says a global report by the World Health Organization (WHO). News about this disease is not all positive, however; TB continues to be one of the world’s deadliest diseases and many cases of TB went unreported last year, according to the WHO report.

Most improvements in mortality rate for TB patients occurred at the beginning of the 21st century, when the United Nations established the Millennium Development Goals, says the report. Such goals included halting and reversing TB incidence on a worldwide basis, in each of the 6 WHO regions, and in 16 of the 22 high-burden countries that collectively account for 80% of TB cases.

“In all, effective diagnosis and treatment of TB saved an estimated 43 million lives between 2000 and 2014,” says the report.

Better reporting on TB’s prevalence led to the first increase in the number of TB cases reported since 2007.

“The annual total of new TB cases, which had been about 5.7 million until 2013, rose to slightly more than 6 million in 2014 (an increase of 6%). This was mostly due to a 29% increase in notification in India, which followed the introduction of a policy of mandatory notification in May 2012, creation of a national Web-based reporting system in June 2012, and intensified efforts to engage the private health sector,” according to the report.

Despite these improvements in data collection of TB incidents, 37% of new TB cases were undiagnosed or not reported last year, with 9.6 million people having fallen sick to TB during a year when just 6 million new cases were reported, according to estimates. Regarding multidrug-resistant TB cases specifically, only 123,000 of an estimated 480,000 cases were detected and reported.

As for the deadliness of the disease, TB killed 1.5 million people in 2014.

Read the full report on the WHO website.

Tuberculosis (TB) mortality has fallen 47% since 1990, and the reporting on incidences of the disease has improved, says a global report by the World Health Organization (WHO). News about this disease is not all positive, however; TB continues to be one of the world’s deadliest diseases and many cases of TB went unreported last year, according to the WHO report.

Most improvements in mortality rate for TB patients occurred at the beginning of the 21st century, when the United Nations established the Millennium Development Goals, says the report. Such goals included halting and reversing TB incidence on a worldwide basis, in each of the 6 WHO regions, and in 16 of the 22 high-burden countries that collectively account for 80% of TB cases.

“In all, effective diagnosis and treatment of TB saved an estimated 43 million lives between 2000 and 2014,” says the report.

Better reporting on TB’s prevalence led to the first increase in the number of TB cases reported since 2007.

“The annual total of new TB cases, which had been about 5.7 million until 2013, rose to slightly more than 6 million in 2014 (an increase of 6%). This was mostly due to a 29% increase in notification in India, which followed the introduction of a policy of mandatory notification in May 2012, creation of a national Web-based reporting system in June 2012, and intensified efforts to engage the private health sector,” according to the report.

Despite these improvements in data collection of TB incidents, 37% of new TB cases were undiagnosed or not reported last year, with 9.6 million people having fallen sick to TB during a year when just 6 million new cases were reported, according to estimates. Regarding multidrug-resistant TB cases specifically, only 123,000 of an estimated 480,000 cases were detected and reported.

As for the deadliness of the disease, TB killed 1.5 million people in 2014.

Read the full report on the WHO website.

FDA approves mepolizumab for use in combination with other asthma drugs

Nucala (mepolizumab) has been approved for use with other asthma medicines as maintenance therapy for patients aged 12 years and older with a history of asthma exacerbations despite adherence with their current asthma medicines, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced Nov. 4.

“This approval offers patients with severe asthma an additional therapy when current treatments cannot maintain adequate control of their asthma,” Dr. Badrul Chowdhury, director of the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Rheumatology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

Nucala is a humanized interleukin-5 antagonist monoclonal antibody that limits severe asthma attacks by reducing the levels of blood eosinophils. Nucala is administered subcutaneously once every 4 weeks by a health care professional.

This innovation in precision medicine is the first and only approved, biologic therapy specifically developed for people with severe asthma with an eosinophilic phenotype, according to a statement from GlaxoSmithKline, the maker of Nucala.

The safety and efficacy of Nucala were established in three double-blind, randomized, placebo‑controlled trials in patients with severe asthma on currently available therapies. Nucala or a placebo was administered to patients every 4 weeks as an add-on asthma treatment. Compared with placebo, patients with severe asthma receiving Nucala had fewer exacerbations requiring hospitalization or emergency department visits, and a longer time to their first exacerbation. In addition, patients with severe asthma receiving Nucala experienced greater reductions in their daily maintenance oral corticosteroid dose, while maintaining asthma control, compared with patients receiving placebo. Treatment with mepolizumab did not result in a significant improvement in lung function, as measured by the volume of air exhaled by patients in 1 second, the FDA said in their statement.

The most common side effects of Nucala include headache, injection site reactions, back pain, and weakness. Hypersensitivity reactions can occur within hours or days of receiving Nucala.

Nucala (mepolizumab) has been approved for use with other asthma medicines as maintenance therapy for patients aged 12 years and older with a history of asthma exacerbations despite adherence with their current asthma medicines, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced Nov. 4.

“This approval offers patients with severe asthma an additional therapy when current treatments cannot maintain adequate control of their asthma,” Dr. Badrul Chowdhury, director of the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Rheumatology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

Nucala is a humanized interleukin-5 antagonist monoclonal antibody that limits severe asthma attacks by reducing the levels of blood eosinophils. Nucala is administered subcutaneously once every 4 weeks by a health care professional.

This innovation in precision medicine is the first and only approved, biologic therapy specifically developed for people with severe asthma with an eosinophilic phenotype, according to a statement from GlaxoSmithKline, the maker of Nucala.

The safety and efficacy of Nucala were established in three double-blind, randomized, placebo‑controlled trials in patients with severe asthma on currently available therapies. Nucala or a placebo was administered to patients every 4 weeks as an add-on asthma treatment. Compared with placebo, patients with severe asthma receiving Nucala had fewer exacerbations requiring hospitalization or emergency department visits, and a longer time to their first exacerbation. In addition, patients with severe asthma receiving Nucala experienced greater reductions in their daily maintenance oral corticosteroid dose, while maintaining asthma control, compared with patients receiving placebo. Treatment with mepolizumab did not result in a significant improvement in lung function, as measured by the volume of air exhaled by patients in 1 second, the FDA said in their statement.

The most common side effects of Nucala include headache, injection site reactions, back pain, and weakness. Hypersensitivity reactions can occur within hours or days of receiving Nucala.

Nucala (mepolizumab) has been approved for use with other asthma medicines as maintenance therapy for patients aged 12 years and older with a history of asthma exacerbations despite adherence with their current asthma medicines, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced Nov. 4.

“This approval offers patients with severe asthma an additional therapy when current treatments cannot maintain adequate control of their asthma,” Dr. Badrul Chowdhury, director of the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Rheumatology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

Nucala is a humanized interleukin-5 antagonist monoclonal antibody that limits severe asthma attacks by reducing the levels of blood eosinophils. Nucala is administered subcutaneously once every 4 weeks by a health care professional.

This innovation in precision medicine is the first and only approved, biologic therapy specifically developed for people with severe asthma with an eosinophilic phenotype, according to a statement from GlaxoSmithKline, the maker of Nucala.

The safety and efficacy of Nucala were established in three double-blind, randomized, placebo‑controlled trials in patients with severe asthma on currently available therapies. Nucala or a placebo was administered to patients every 4 weeks as an add-on asthma treatment. Compared with placebo, patients with severe asthma receiving Nucala had fewer exacerbations requiring hospitalization or emergency department visits, and a longer time to their first exacerbation. In addition, patients with severe asthma receiving Nucala experienced greater reductions in their daily maintenance oral corticosteroid dose, while maintaining asthma control, compared with patients receiving placebo. Treatment with mepolizumab did not result in a significant improvement in lung function, as measured by the volume of air exhaled by patients in 1 second, the FDA said in their statement.

The most common side effects of Nucala include headache, injection site reactions, back pain, and weakness. Hypersensitivity reactions can occur within hours or days of receiving Nucala.

CHEST: Catheter-directed thrombolysis shows pulmonary embolism efficacy

MONTREAL – Catheter-directed thrombolysis surpassed systemic thrombolysis for minimizing in-hospital mortality of patients with an acute pulmonary embolism in a review of more than 1,500 U.S. patients.

The review also found evidence that U.S. pulmonary embolism (PE) patients increasingly undergo catheter-directed thrombolysis, with usage jumping by more than 50% from 2010 to 2012, although in 2012 U.S. clinicians performed catheter-directed thrombolysis on 160 patients with an acute pulmonary embolism (PE) who were included in a national U.S. registry of hospitalized patients, Dr. Amina Saqib said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis resulted in a 9% in-hospital mortality rate and a 10% combined rate of in-hospital mortality plus intracerebral hemorrhages, rates significantly below those tallied in propensity score–matched patients who underwent systemic thrombolysis of their acute PE. The matched group with systemic thrombolysis had a 17% in-hospital mortality rate and a 17% combined mortality plus intracerebral hemorrhage rate, said Dr. Saqib, a researcher at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first, large, nationwide, observational study that compared safety and efficacy outcomes between systemic thrombolysis and catheter-directed thrombolysis in acute PE,” Dr. Saqib said.

The U.S. data, collected during 2010-2012, also showed that, after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables, each acute PE treatment by catheter-directed thrombolysis cost an average $9,428 above the cost for systemic thrombolysis, she said.

“We need to more systematically identify the patients with an acute PE who could benefit from catheter-directed thrombolysis, especially patients with a massive PE,” commented Dr. Muthiah P. Muthiah, a critical-care medicine physician at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis. “This may be something to offer to patients who have an absolute contraindication for systemic thrombolysis, such as recent surgery, but it is not available everywhere,” Dr. Muthiah said in an interview.

Dr. Saqib and her associates used data collected by the Federal National Inpatient Sample. Among U.S. patients hospitalized during 2010-2012 and entered into this database, they identified 1,169 adult acute PE patients who underwent systemic thrombolysis and 352 patients who received catheter-directed thrombolysis. The patients averaged about 58 years old and just under half were men.

The propensity score–adjusted analysis also showed no statistically significant difference between the two treatment approaches for the incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage, any hemorrhages requiring a transfusion, new-onset acute renal failure, or hospital length of stay. Among the patients treated by catheter-directed thrombolysis, all the intracerebral hemorrhages occurred during 2010; during 2011 and 2012 none of the patients treated this way had an intracerebral hemorrhage, Dr. Saqib noted.

Although the findings were consistent with results from prior analyses, the propensity-score adjustment used in the current study cannot fully account for all unmeasured confounding factors. The best way to compare catheter-directed thrombolysis and systemic thrombolysis for treating acute PE would be in a prospective, randomized study, Dr. Saqib said.

Dr. Saqib and Dr. Muthiah had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – Catheter-directed thrombolysis surpassed systemic thrombolysis for minimizing in-hospital mortality of patients with an acute pulmonary embolism in a review of more than 1,500 U.S. patients.

The review also found evidence that U.S. pulmonary embolism (PE) patients increasingly undergo catheter-directed thrombolysis, with usage jumping by more than 50% from 2010 to 2012, although in 2012 U.S. clinicians performed catheter-directed thrombolysis on 160 patients with an acute pulmonary embolism (PE) who were included in a national U.S. registry of hospitalized patients, Dr. Amina Saqib said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis resulted in a 9% in-hospital mortality rate and a 10% combined rate of in-hospital mortality plus intracerebral hemorrhages, rates significantly below those tallied in propensity score–matched patients who underwent systemic thrombolysis of their acute PE. The matched group with systemic thrombolysis had a 17% in-hospital mortality rate and a 17% combined mortality plus intracerebral hemorrhage rate, said Dr. Saqib, a researcher at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first, large, nationwide, observational study that compared safety and efficacy outcomes between systemic thrombolysis and catheter-directed thrombolysis in acute PE,” Dr. Saqib said.

The U.S. data, collected during 2010-2012, also showed that, after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables, each acute PE treatment by catheter-directed thrombolysis cost an average $9,428 above the cost for systemic thrombolysis, she said.

“We need to more systematically identify the patients with an acute PE who could benefit from catheter-directed thrombolysis, especially patients with a massive PE,” commented Dr. Muthiah P. Muthiah, a critical-care medicine physician at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis. “This may be something to offer to patients who have an absolute contraindication for systemic thrombolysis, such as recent surgery, but it is not available everywhere,” Dr. Muthiah said in an interview.

Dr. Saqib and her associates used data collected by the Federal National Inpatient Sample. Among U.S. patients hospitalized during 2010-2012 and entered into this database, they identified 1,169 adult acute PE patients who underwent systemic thrombolysis and 352 patients who received catheter-directed thrombolysis. The patients averaged about 58 years old and just under half were men.

The propensity score–adjusted analysis also showed no statistically significant difference between the two treatment approaches for the incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage, any hemorrhages requiring a transfusion, new-onset acute renal failure, or hospital length of stay. Among the patients treated by catheter-directed thrombolysis, all the intracerebral hemorrhages occurred during 2010; during 2011 and 2012 none of the patients treated this way had an intracerebral hemorrhage, Dr. Saqib noted.

Although the findings were consistent with results from prior analyses, the propensity-score adjustment used in the current study cannot fully account for all unmeasured confounding factors. The best way to compare catheter-directed thrombolysis and systemic thrombolysis for treating acute PE would be in a prospective, randomized study, Dr. Saqib said.

Dr. Saqib and Dr. Muthiah had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – Catheter-directed thrombolysis surpassed systemic thrombolysis for minimizing in-hospital mortality of patients with an acute pulmonary embolism in a review of more than 1,500 U.S. patients.

The review also found evidence that U.S. pulmonary embolism (PE) patients increasingly undergo catheter-directed thrombolysis, with usage jumping by more than 50% from 2010 to 2012, although in 2012 U.S. clinicians performed catheter-directed thrombolysis on 160 patients with an acute pulmonary embolism (PE) who were included in a national U.S. registry of hospitalized patients, Dr. Amina Saqib said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis resulted in a 9% in-hospital mortality rate and a 10% combined rate of in-hospital mortality plus intracerebral hemorrhages, rates significantly below those tallied in propensity score–matched patients who underwent systemic thrombolysis of their acute PE. The matched group with systemic thrombolysis had a 17% in-hospital mortality rate and a 17% combined mortality plus intracerebral hemorrhage rate, said Dr. Saqib, a researcher at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first, large, nationwide, observational study that compared safety and efficacy outcomes between systemic thrombolysis and catheter-directed thrombolysis in acute PE,” Dr. Saqib said.

The U.S. data, collected during 2010-2012, also showed that, after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables, each acute PE treatment by catheter-directed thrombolysis cost an average $9,428 above the cost for systemic thrombolysis, she said.

“We need to more systematically identify the patients with an acute PE who could benefit from catheter-directed thrombolysis, especially patients with a massive PE,” commented Dr. Muthiah P. Muthiah, a critical-care medicine physician at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis. “This may be something to offer to patients who have an absolute contraindication for systemic thrombolysis, such as recent surgery, but it is not available everywhere,” Dr. Muthiah said in an interview.

Dr. Saqib and her associates used data collected by the Federal National Inpatient Sample. Among U.S. patients hospitalized during 2010-2012 and entered into this database, they identified 1,169 adult acute PE patients who underwent systemic thrombolysis and 352 patients who received catheter-directed thrombolysis. The patients averaged about 58 years old and just under half were men.

The propensity score–adjusted analysis also showed no statistically significant difference between the two treatment approaches for the incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage, any hemorrhages requiring a transfusion, new-onset acute renal failure, or hospital length of stay. Among the patients treated by catheter-directed thrombolysis, all the intracerebral hemorrhages occurred during 2010; during 2011 and 2012 none of the patients treated this way had an intracerebral hemorrhage, Dr. Saqib noted.

Although the findings were consistent with results from prior analyses, the propensity-score adjustment used in the current study cannot fully account for all unmeasured confounding factors. The best way to compare catheter-directed thrombolysis and systemic thrombolysis for treating acute PE would be in a prospective, randomized study, Dr. Saqib said.

Dr. Saqib and Dr. Muthiah had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT CHEST 2015

Key clinical point: Catheter-directed thrombolysis was linked to reduced mortality, compared with systemic thrombolysis in patients with an acute pulmonary embolism.

Major finding: In-hospital mortality in acute pulmonary embolism patients ran 10% with catheter-directed thrombolysis and 17% with systemic thrombolysis.

Data source: Review of 1,521 U.S. patients treated for acute pulmonary embolism during 2010-2012 in the National Inpatient Sample.

Disclosures: Dr. Saqib and Dr. Muthiah had no disclosures.

AHA Releases First-ever Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension Guideline

The American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society jointly released the first-ever clinical practice guideline for assessing and managing pulmonary hypertension (PH) in the pediatric population, which was published online Nov. 3 in Circulation.

The two organizations developed this guideline because the causes and treatments of PH in neonates, infants, and children are often different from those in adults. The literature for adult PH is “robust,” and there are several treatment guidelines available, whereas pediatric PH has not been well studied, “and little is understood about the natural history, fundamental mechanisms, and treatment of childhood PH,” said Dr. Steven H. Abman, cochair of the guideline committee and a pediatric pulmonologist at the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital, both in Denver.

“It’s important to note that, although these guidelines provide a foundation for taking care of children with pulmonary hypertension, we still have a huge need for more specific data and research to further improve outcomes,” he said in a statement accompanying the guideline.

This guideline was developed by a working group of 27 clinicians and researchers with expertise in pediatric pulmonology, pediatric and adult cardiology, pediatric intensivism, neonatology, and translational science. They reviewed more than 600 articles in the literature, but given the paucity of high-quality data regarding pediatric PH, the guideline relies heavily on expert opinion and primarily describes “generally acceptable approaches” to diagnosis and management; more specific and detailed recommendations await the findings of future research, Dr. Abman and his associates said (Circulation. 2015 Oct 26. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000329).

In the pediatric population, PH is defined as a resting mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 25 mm Hg after the first few months of life and is usually related to cardiac, lung, or systemic diseases. Idiopathic PH, a pulmonary vasculopathy, is a diagnosis of exclusion after diseases of the left side of the heart, lung parenchyma, heart valves, thromboembolism, and other miscellaneous causes have been ruled out.

The guideline emphasizes that children thought to have PH should be evaluated and treated at comprehensive, multidisciplinary clinics at specialized pediatric centers. “When children are diagnosed, parents often feel helpless. However, it’s important that parents seek doctors and centers that see these children on a regular basis and can offer them access to new molecular diagnostics, new drug therapies, and new devices, as well as surgeries that have recently been developed,” Dr. Stephen L. Archer, cochair of the guideline committee and head of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., said in the statement.

“These children suffer with health issues throughout their lives or die prematurely, particularly if they’re not properly diagnosed and managed. But with the proper diagnosis and treatment at a specialized center for PH, the prognosis for many of these children is excellent,” he noted.

Properly classifying the type of PH is a key first step in determining treatment. The guideline addresses numerous methods for diagnosing and monitoring PH, including imaging studies, echocardiograms, cardiac catheterization, brain natriuretic peptide and other laboratory testing, 6-minute walk distance (at appropriate ages), sleep studies, and genetic testing. It specifically deals with persistent PH of the newborn and PH arising from congenital diaphragmatic hernia; bronchopulmonary dysplasia or other lung diseases; heart disease such as atrial-septal defect or patent ductus arteriosus; and systemic diseases such as hemolytic hemoglobinopathies and hepatic, renal, or metabolic illness; as well as idiopathic PH and PH related to high-altitude pulmonary edema.

Regarding ongoing outpatient care, the guideline recommends that children with PH receive influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations and prophylaxis for respiratory syncytial virus (if they are eligible), as well as antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent subacute bacterial endocarditis in those who are cyanotic or have indwelling central lines. Growth must be monitored rigorously, and infections and respiratory illnesses must be recognized and treated promptly. Any surgeries require careful preoperative planning and should be performed at hospitals with expertise in PH.

The guideline includes an extensive section on pharmacotherapy for childhood PH, including the use of digitalis, diuretics, long-term anticoagulation, oxygen therapy, calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists, intravenous and subcutaneous prostacyclin therapy, and the transition from parenteral to oral or inhaled treatment.

In addition, the guideline addresses exercise and sports participation, travel restrictions, and contraceptive counseling for adolescent patients. Finally, “given the impact of childhood PH on the entire family, [patients], siblings, and caregivers should be assessed for psychosocial stress and be readily provided support and referral as needed,” the guideline recommends.

A copy of the guideline is available at http://my.americanheart.org/statements.

The pediatric pulmonary, pediatric cardiology, and neonatal and pediatric intensivists all have greatly anticipated directions for the care of pediatric pulmonary hypertension. The guidelines have excellent care maps for the diagnosis and evaluation of the various etiologies of pulmonary hypertension.

The new guidelines also should help also with insurance authorizations for the expensive medications for pulmonary hypertension! Dr. Robyn J. Barst, a renowned leader in pediatric pulmonary hypertension, who passed away in 2013, would be so proud of this AHA guideline!

Dr. Susan L. Millard is director of research, pediatric pulmonary & sleep medicine at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, MI.

The pediatric pulmonary, pediatric cardiology, and neonatal and pediatric intensivists all have greatly anticipated directions for the care of pediatric pulmonary hypertension. The guidelines have excellent care maps for the diagnosis and evaluation of the various etiologies of pulmonary hypertension.

The new guidelines also should help also with insurance authorizations for the expensive medications for pulmonary hypertension! Dr. Robyn J. Barst, a renowned leader in pediatric pulmonary hypertension, who passed away in 2013, would be so proud of this AHA guideline!

Dr. Susan L. Millard is director of research, pediatric pulmonary & sleep medicine at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, MI.

The pediatric pulmonary, pediatric cardiology, and neonatal and pediatric intensivists all have greatly anticipated directions for the care of pediatric pulmonary hypertension. The guidelines have excellent care maps for the diagnosis and evaluation of the various etiologies of pulmonary hypertension.

The new guidelines also should help also with insurance authorizations for the expensive medications for pulmonary hypertension! Dr. Robyn J. Barst, a renowned leader in pediatric pulmonary hypertension, who passed away in 2013, would be so proud of this AHA guideline!

Dr. Susan L. Millard is director of research, pediatric pulmonary & sleep medicine at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, MI.

The American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society jointly released the first-ever clinical practice guideline for assessing and managing pulmonary hypertension (PH) in the pediatric population, which was published online Nov. 3 in Circulation.

The two organizations developed this guideline because the causes and treatments of PH in neonates, infants, and children are often different from those in adults. The literature for adult PH is “robust,” and there are several treatment guidelines available, whereas pediatric PH has not been well studied, “and little is understood about the natural history, fundamental mechanisms, and treatment of childhood PH,” said Dr. Steven H. Abman, cochair of the guideline committee and a pediatric pulmonologist at the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital, both in Denver.

“It’s important to note that, although these guidelines provide a foundation for taking care of children with pulmonary hypertension, we still have a huge need for more specific data and research to further improve outcomes,” he said in a statement accompanying the guideline.

This guideline was developed by a working group of 27 clinicians and researchers with expertise in pediatric pulmonology, pediatric and adult cardiology, pediatric intensivism, neonatology, and translational science. They reviewed more than 600 articles in the literature, but given the paucity of high-quality data regarding pediatric PH, the guideline relies heavily on expert opinion and primarily describes “generally acceptable approaches” to diagnosis and management; more specific and detailed recommendations await the findings of future research, Dr. Abman and his associates said (Circulation. 2015 Oct 26. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000329).

In the pediatric population, PH is defined as a resting mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 25 mm Hg after the first few months of life and is usually related to cardiac, lung, or systemic diseases. Idiopathic PH, a pulmonary vasculopathy, is a diagnosis of exclusion after diseases of the left side of the heart, lung parenchyma, heart valves, thromboembolism, and other miscellaneous causes have been ruled out.

The guideline emphasizes that children thought to have PH should be evaluated and treated at comprehensive, multidisciplinary clinics at specialized pediatric centers. “When children are diagnosed, parents often feel helpless. However, it’s important that parents seek doctors and centers that see these children on a regular basis and can offer them access to new molecular diagnostics, new drug therapies, and new devices, as well as surgeries that have recently been developed,” Dr. Stephen L. Archer, cochair of the guideline committee and head of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., said in the statement.

“These children suffer with health issues throughout their lives or die prematurely, particularly if they’re not properly diagnosed and managed. But with the proper diagnosis and treatment at a specialized center for PH, the prognosis for many of these children is excellent,” he noted.

Properly classifying the type of PH is a key first step in determining treatment. The guideline addresses numerous methods for diagnosing and monitoring PH, including imaging studies, echocardiograms, cardiac catheterization, brain natriuretic peptide and other laboratory testing, 6-minute walk distance (at appropriate ages), sleep studies, and genetic testing. It specifically deals with persistent PH of the newborn and PH arising from congenital diaphragmatic hernia; bronchopulmonary dysplasia or other lung diseases; heart disease such as atrial-septal defect or patent ductus arteriosus; and systemic diseases such as hemolytic hemoglobinopathies and hepatic, renal, or metabolic illness; as well as idiopathic PH and PH related to high-altitude pulmonary edema.

Regarding ongoing outpatient care, the guideline recommends that children with PH receive influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations and prophylaxis for respiratory syncytial virus (if they are eligible), as well as antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent subacute bacterial endocarditis in those who are cyanotic or have indwelling central lines. Growth must be monitored rigorously, and infections and respiratory illnesses must be recognized and treated promptly. Any surgeries require careful preoperative planning and should be performed at hospitals with expertise in PH.

The guideline includes an extensive section on pharmacotherapy for childhood PH, including the use of digitalis, diuretics, long-term anticoagulation, oxygen therapy, calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists, intravenous and subcutaneous prostacyclin therapy, and the transition from parenteral to oral or inhaled treatment.

In addition, the guideline addresses exercise and sports participation, travel restrictions, and contraceptive counseling for adolescent patients. Finally, “given the impact of childhood PH on the entire family, [patients], siblings, and caregivers should be assessed for psychosocial stress and be readily provided support and referral as needed,” the guideline recommends.

A copy of the guideline is available at http://my.americanheart.org/statements.

The American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society jointly released the first-ever clinical practice guideline for assessing and managing pulmonary hypertension (PH) in the pediatric population, which was published online Nov. 3 in Circulation.

The two organizations developed this guideline because the causes and treatments of PH in neonates, infants, and children are often different from those in adults. The literature for adult PH is “robust,” and there are several treatment guidelines available, whereas pediatric PH has not been well studied, “and little is understood about the natural history, fundamental mechanisms, and treatment of childhood PH,” said Dr. Steven H. Abman, cochair of the guideline committee and a pediatric pulmonologist at the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital, both in Denver.

“It’s important to note that, although these guidelines provide a foundation for taking care of children with pulmonary hypertension, we still have a huge need for more specific data and research to further improve outcomes,” he said in a statement accompanying the guideline.

This guideline was developed by a working group of 27 clinicians and researchers with expertise in pediatric pulmonology, pediatric and adult cardiology, pediatric intensivism, neonatology, and translational science. They reviewed more than 600 articles in the literature, but given the paucity of high-quality data regarding pediatric PH, the guideline relies heavily on expert opinion and primarily describes “generally acceptable approaches” to diagnosis and management; more specific and detailed recommendations await the findings of future research, Dr. Abman and his associates said (Circulation. 2015 Oct 26. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000329).

In the pediatric population, PH is defined as a resting mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 25 mm Hg after the first few months of life and is usually related to cardiac, lung, or systemic diseases. Idiopathic PH, a pulmonary vasculopathy, is a diagnosis of exclusion after diseases of the left side of the heart, lung parenchyma, heart valves, thromboembolism, and other miscellaneous causes have been ruled out.

The guideline emphasizes that children thought to have PH should be evaluated and treated at comprehensive, multidisciplinary clinics at specialized pediatric centers. “When children are diagnosed, parents often feel helpless. However, it’s important that parents seek doctors and centers that see these children on a regular basis and can offer them access to new molecular diagnostics, new drug therapies, and new devices, as well as surgeries that have recently been developed,” Dr. Stephen L. Archer, cochair of the guideline committee and head of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., said in the statement.

“These children suffer with health issues throughout their lives or die prematurely, particularly if they’re not properly diagnosed and managed. But with the proper diagnosis and treatment at a specialized center for PH, the prognosis for many of these children is excellent,” he noted.

Properly classifying the type of PH is a key first step in determining treatment. The guideline addresses numerous methods for diagnosing and monitoring PH, including imaging studies, echocardiograms, cardiac catheterization, brain natriuretic peptide and other laboratory testing, 6-minute walk distance (at appropriate ages), sleep studies, and genetic testing. It specifically deals with persistent PH of the newborn and PH arising from congenital diaphragmatic hernia; bronchopulmonary dysplasia or other lung diseases; heart disease such as atrial-septal defect or patent ductus arteriosus; and systemic diseases such as hemolytic hemoglobinopathies and hepatic, renal, or metabolic illness; as well as idiopathic PH and PH related to high-altitude pulmonary edema.

Regarding ongoing outpatient care, the guideline recommends that children with PH receive influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations and prophylaxis for respiratory syncytial virus (if they are eligible), as well as antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent subacute bacterial endocarditis in those who are cyanotic or have indwelling central lines. Growth must be monitored rigorously, and infections and respiratory illnesses must be recognized and treated promptly. Any surgeries require careful preoperative planning and should be performed at hospitals with expertise in PH.

The guideline includes an extensive section on pharmacotherapy for childhood PH, including the use of digitalis, diuretics, long-term anticoagulation, oxygen therapy, calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists, intravenous and subcutaneous prostacyclin therapy, and the transition from parenteral to oral or inhaled treatment.

In addition, the guideline addresses exercise and sports participation, travel restrictions, and contraceptive counseling for adolescent patients. Finally, “given the impact of childhood PH on the entire family, [patients], siblings, and caregivers should be assessed for psychosocial stress and be readily provided support and referral as needed,” the guideline recommends.

A copy of the guideline is available at http://my.americanheart.org/statements.

FROM CIRCULATION

AHA releases first-ever pediatric pulmonary hypertension guideline

The American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society jointly released the first-ever clinical practice guideline for assessing and managing pulmonary hypertension (PH) in the pediatric population, which was published online Nov. 3 in Circulation.

The two organizations developed this guideline because the causes and treatments of PH in neonates, infants, and children are often different from those in adults. The literature for adult PH is “robust,” and there are several treatment guidelines available, whereas pediatric PH has not been well studied, “and little is understood about the natural history, fundamental mechanisms, and treatment of childhood PH,” said Dr. Steven H. Abman, cochair of the guideline committee and a pediatric pulmonologist at the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital, both in Denver.

“It’s important to note that, although these guidelines provide a foundation for taking care of children with pulmonary hypertension, we still have a huge need for more specific data and research to further improve outcomes,” he said in a statement accompanying the guideline.

This guideline was developed by a working group of 27 clinicians and researchers with expertise in pediatric pulmonology, pediatric and adult cardiology, pediatric intensivism, neonatology, and translational science. They reviewed more than 600 articles in the literature, but given the paucity of high-quality data regarding pediatric PH, the guideline relies heavily on expert opinion and primarily describes “generally acceptable approaches” to diagnosis and management; more specific and detailed recommendations await the findings of future research, Dr. Abman and his associates said (Circulation. 2015 Oct 26. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000329).

In the pediatric population, PH is defined as a resting mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 25 mm Hg after the first few months of life and is usually related to cardiac, lung, or systemic diseases. Idiopathic PH, a pulmonary vasculopathy, is a diagnosis of exclusion after diseases of the left side of the heart, lung parenchyma, heart valves, thromboembolism, and other miscellaneous causes have been ruled out.

The guideline emphasizes that children thought to have PH should be evaluated and treated at comprehensive, multidisciplinary clinics at specialized pediatric centers. “When children are diagnosed, parents often feel helpless. However, it’s important that parents seek doctors and centers that see these children on a regular basis and can offer them access to new molecular diagnostics, new drug therapies, and new devices, as well as surgeries that have recently been developed,” Dr. Stephen L. Archer, cochair of the guideline committee and head of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., said in the statement.

“These children suffer with health issues throughout their lives or die prematurely, particularly if they’re not properly diagnosed and managed. But with the proper diagnosis and treatment at a specialized center for PH, the prognosis for many of these children is excellent,” he noted.

Properly classifying the type of PH is a key first step in determining treatment. The guideline addresses numerous methods for diagnosing and monitoring PH, including imaging studies, echocardiograms, cardiac catheterization, brain natriuretic peptide and other laboratory testing, 6-minute walk distance (at appropriate ages), sleep studies, and genetic testing. It specifically deals with persistent PH of the newborn and PH arising from congenital diaphragmatic hernia; bronchopulmonary dysplasia or other lung diseases; heart disease such as atrial-septal defect or patent ductus arteriosus; and systemic diseases such as hemolytic hemoglobinopathies and hepatic, renal, or metabolic illness; as well as idiopathic PH and PH related to high-altitude pulmonary edema.

Regarding ongoing outpatient care, the guideline recommends that children with PH receive influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations and prophylaxis for respiratory syncytial virus (if they are eligible), as well as antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent subacute bacterial endocarditis in those who are cyanotic or have indwelling central lines. Growth must be monitored rigorously, and infections and respiratory illnesses must be recognized and treated promptly. Any surgeries require careful preoperative planning and should be performed at hospitals with expertise in PH.

The guideline includes an extensive section on pharmacotherapy for childhood PH, including the use of digitalis, diuretics, long-term anticoagulation, oxygen therapy, calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists, intravenous and subcutaneous prostacyclin therapy, and the transition from parenteral to oral or inhaled treatment.

In addition, the guideline addresses exercise and sports participation, travel restrictions, and contraceptive counseling for adolescent patients. Finally, “given the impact of childhood PH on the entire family, [patients], siblings, and caregivers should be assessed for psychosocial stress and be readily provided support and referral as needed,” the guideline recommends.

A copy of the guideline is available at http://my.americanheart.org/statements.

The pediatric pulmonary, pediatric cardiology, and neonatal and pediatric intensivists all have greatly anticipated directions for the care of pediatric pulmonary hypertension. The guidelines have excellent care maps for the diagnosis and evaluation of the various etiologies of pulmonary hypertension.

The new guidelines also should help also with insurance authorizations for the expensive medications for pulmonary hypertension! Dr. Robyn J. Barst, a renowned leader in pediatric pulmonary hypertension, who passed away in 2013, would be so proud of this AHA guideline!

Dr. Susan L. Millard is director of research, pediatric pulmonary & sleep medicine at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, MI.

The pediatric pulmonary, pediatric cardiology, and neonatal and pediatric intensivists all have greatly anticipated directions for the care of pediatric pulmonary hypertension. The guidelines have excellent care maps for the diagnosis and evaluation of the various etiologies of pulmonary hypertension.

The new guidelines also should help also with insurance authorizations for the expensive medications for pulmonary hypertension! Dr. Robyn J. Barst, a renowned leader in pediatric pulmonary hypertension, who passed away in 2013, would be so proud of this AHA guideline!

Dr. Susan L. Millard is director of research, pediatric pulmonary & sleep medicine at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, MI.

The pediatric pulmonary, pediatric cardiology, and neonatal and pediatric intensivists all have greatly anticipated directions for the care of pediatric pulmonary hypertension. The guidelines have excellent care maps for the diagnosis and evaluation of the various etiologies of pulmonary hypertension.

The new guidelines also should help also with insurance authorizations for the expensive medications for pulmonary hypertension! Dr. Robyn J. Barst, a renowned leader in pediatric pulmonary hypertension, who passed away in 2013, would be so proud of this AHA guideline!

Dr. Susan L. Millard is director of research, pediatric pulmonary & sleep medicine at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, MI.

The American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society jointly released the first-ever clinical practice guideline for assessing and managing pulmonary hypertension (PH) in the pediatric population, which was published online Nov. 3 in Circulation.

The two organizations developed this guideline because the causes and treatments of PH in neonates, infants, and children are often different from those in adults. The literature for adult PH is “robust,” and there are several treatment guidelines available, whereas pediatric PH has not been well studied, “and little is understood about the natural history, fundamental mechanisms, and treatment of childhood PH,” said Dr. Steven H. Abman, cochair of the guideline committee and a pediatric pulmonologist at the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital, both in Denver.

“It’s important to note that, although these guidelines provide a foundation for taking care of children with pulmonary hypertension, we still have a huge need for more specific data and research to further improve outcomes,” he said in a statement accompanying the guideline.

This guideline was developed by a working group of 27 clinicians and researchers with expertise in pediatric pulmonology, pediatric and adult cardiology, pediatric intensivism, neonatology, and translational science. They reviewed more than 600 articles in the literature, but given the paucity of high-quality data regarding pediatric PH, the guideline relies heavily on expert opinion and primarily describes “generally acceptable approaches” to diagnosis and management; more specific and detailed recommendations await the findings of future research, Dr. Abman and his associates said (Circulation. 2015 Oct 26. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000329).

In the pediatric population, PH is defined as a resting mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 25 mm Hg after the first few months of life and is usually related to cardiac, lung, or systemic diseases. Idiopathic PH, a pulmonary vasculopathy, is a diagnosis of exclusion after diseases of the left side of the heart, lung parenchyma, heart valves, thromboembolism, and other miscellaneous causes have been ruled out.

The guideline emphasizes that children thought to have PH should be evaluated and treated at comprehensive, multidisciplinary clinics at specialized pediatric centers. “When children are diagnosed, parents often feel helpless. However, it’s important that parents seek doctors and centers that see these children on a regular basis and can offer them access to new molecular diagnostics, new drug therapies, and new devices, as well as surgeries that have recently been developed,” Dr. Stephen L. Archer, cochair of the guideline committee and head of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., said in the statement.

“These children suffer with health issues throughout their lives or die prematurely, particularly if they’re not properly diagnosed and managed. But with the proper diagnosis and treatment at a specialized center for PH, the prognosis for many of these children is excellent,” he noted.

Properly classifying the type of PH is a key first step in determining treatment. The guideline addresses numerous methods for diagnosing and monitoring PH, including imaging studies, echocardiograms, cardiac catheterization, brain natriuretic peptide and other laboratory testing, 6-minute walk distance (at appropriate ages), sleep studies, and genetic testing. It specifically deals with persistent PH of the newborn and PH arising from congenital diaphragmatic hernia; bronchopulmonary dysplasia or other lung diseases; heart disease such as atrial-septal defect or patent ductus arteriosus; and systemic diseases such as hemolytic hemoglobinopathies and hepatic, renal, or metabolic illness; as well as idiopathic PH and PH related to high-altitude pulmonary edema.

Regarding ongoing outpatient care, the guideline recommends that children with PH receive influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations and prophylaxis for respiratory syncytial virus (if they are eligible), as well as antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent subacute bacterial endocarditis in those who are cyanotic or have indwelling central lines. Growth must be monitored rigorously, and infections and respiratory illnesses must be recognized and treated promptly. Any surgeries require careful preoperative planning and should be performed at hospitals with expertise in PH.

The guideline includes an extensive section on pharmacotherapy for childhood PH, including the use of digitalis, diuretics, long-term anticoagulation, oxygen therapy, calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists, intravenous and subcutaneous prostacyclin therapy, and the transition from parenteral to oral or inhaled treatment.

In addition, the guideline addresses exercise and sports participation, travel restrictions, and contraceptive counseling for adolescent patients. Finally, “given the impact of childhood PH on the entire family, [patients], siblings, and caregivers should be assessed for psychosocial stress and be readily provided support and referral as needed,” the guideline recommends.

A copy of the guideline is available at http://my.americanheart.org/statements.

The American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society jointly released the first-ever clinical practice guideline for assessing and managing pulmonary hypertension (PH) in the pediatric population, which was published online Nov. 3 in Circulation.

The two organizations developed this guideline because the causes and treatments of PH in neonates, infants, and children are often different from those in adults. The literature for adult PH is “robust,” and there are several treatment guidelines available, whereas pediatric PH has not been well studied, “and little is understood about the natural history, fundamental mechanisms, and treatment of childhood PH,” said Dr. Steven H. Abman, cochair of the guideline committee and a pediatric pulmonologist at the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital, both in Denver.

“It’s important to note that, although these guidelines provide a foundation for taking care of children with pulmonary hypertension, we still have a huge need for more specific data and research to further improve outcomes,” he said in a statement accompanying the guideline.

This guideline was developed by a working group of 27 clinicians and researchers with expertise in pediatric pulmonology, pediatric and adult cardiology, pediatric intensivism, neonatology, and translational science. They reviewed more than 600 articles in the literature, but given the paucity of high-quality data regarding pediatric PH, the guideline relies heavily on expert opinion and primarily describes “generally acceptable approaches” to diagnosis and management; more specific and detailed recommendations await the findings of future research, Dr. Abman and his associates said (Circulation. 2015 Oct 26. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000329).

In the pediatric population, PH is defined as a resting mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 25 mm Hg after the first few months of life and is usually related to cardiac, lung, or systemic diseases. Idiopathic PH, a pulmonary vasculopathy, is a diagnosis of exclusion after diseases of the left side of the heart, lung parenchyma, heart valves, thromboembolism, and other miscellaneous causes have been ruled out.

The guideline emphasizes that children thought to have PH should be evaluated and treated at comprehensive, multidisciplinary clinics at specialized pediatric centers. “When children are diagnosed, parents often feel helpless. However, it’s important that parents seek doctors and centers that see these children on a regular basis and can offer them access to new molecular diagnostics, new drug therapies, and new devices, as well as surgeries that have recently been developed,” Dr. Stephen L. Archer, cochair of the guideline committee and head of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., said in the statement.

“These children suffer with health issues throughout their lives or die prematurely, particularly if they’re not properly diagnosed and managed. But with the proper diagnosis and treatment at a specialized center for PH, the prognosis for many of these children is excellent,” he noted.

Properly classifying the type of PH is a key first step in determining treatment. The guideline addresses numerous methods for diagnosing and monitoring PH, including imaging studies, echocardiograms, cardiac catheterization, brain natriuretic peptide and other laboratory testing, 6-minute walk distance (at appropriate ages), sleep studies, and genetic testing. It specifically deals with persistent PH of the newborn and PH arising from congenital diaphragmatic hernia; bronchopulmonary dysplasia or other lung diseases; heart disease such as atrial-septal defect or patent ductus arteriosus; and systemic diseases such as hemolytic hemoglobinopathies and hepatic, renal, or metabolic illness; as well as idiopathic PH and PH related to high-altitude pulmonary edema.

Regarding ongoing outpatient care, the guideline recommends that children with PH receive influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations and prophylaxis for respiratory syncytial virus (if they are eligible), as well as antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent subacute bacterial endocarditis in those who are cyanotic or have indwelling central lines. Growth must be monitored rigorously, and infections and respiratory illnesses must be recognized and treated promptly. Any surgeries require careful preoperative planning and should be performed at hospitals with expertise in PH.

The guideline includes an extensive section on pharmacotherapy for childhood PH, including the use of digitalis, diuretics, long-term anticoagulation, oxygen therapy, calcium channel blockers, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists, intravenous and subcutaneous prostacyclin therapy, and the transition from parenteral to oral or inhaled treatment.

In addition, the guideline addresses exercise and sports participation, travel restrictions, and contraceptive counseling for adolescent patients. Finally, “given the impact of childhood PH on the entire family, [patients], siblings, and caregivers should be assessed for psychosocial stress and be readily provided support and referral as needed,” the guideline recommends.

A copy of the guideline is available at http://my.americanheart.org/statements.

FROM CIRCULATION

VIDEO: MMF equals cyclophosphamide’s efficacy in sclerodermal lung disease

MONTREAL – The immunosuppressant mycophenolate mofetil worked as effectively as cyclophosphamide for treating scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease while being better tolerated and causing fewer adverse effects in a multicenter, head-to-head comparison with 142 randomized patients.

“The findings support the increasingly common clinical practice of prescribing MMF [mycophenolate mofetil] for this disease,” said Dr. Donald P. Tashkin at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Another limitation of cyclophosphamide is that it is usually not used for more than 1 year because of concerns that longer use substantially increases a patient’s risk for developing malignancy. That’s another reason why there is a “strong need for longer and safer immunosuppressive treatment with a drug like MMF,” said Dr. Tashkin, a pulmonologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

When used in this trial on patients with scleroderma, as defined by the American College of Rheumatology and with a baseline forced vital capacity of no more than 80% of predicted, “MMF was effective at reducing the rate of decline in vital capacity, improving symptoms such as dyspnea – the cardinal symptom of interstitial lung disease, and reducing lung fibrosis seen on CT scans, and MMF was better tolerated” than cyclophosphamide, Dr. Tashkin said in an interview. Cyclophosphamide treatment in this new trial “was associated with more toxicity, especially hematologic toxicity, an was not nearly as well tolerated, with more patients withdrawing because of side effects or a perceived lack of benefit.”

“Cyclophosphamide has a lot of side effects. MMF is just now coming into increased use. I think we’ll see it being used more for first-line treatment because the side effects with cyclophosphamide are so bad,” commented Dr. Thomas Fuhrman, chief of anesthesiology at the Bay Pines (Fla.) VA Healthcare System.

Dr. Tashkin and his associates conceived the Scleroderma Lung Study II (SLSII) as a follow-up to the first SLS run about a decade ago that compared cyclosphosphamide against placebo for controlling progression of interstitial lung disease in scleroderma patients. The results from the first SLS trial established cyclosphosphamide as a treatment that could preserve forced vital capacity percent predicted in patients with scleroderma-induced interstitial lung disease (N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 22;354[25]:2655-666).

For the new study they enrolled patients who averaged 52 years old, with an average scleroderma duration of almost 3 years. Their average percent predicted forced vital capacity was 67%, and their baseline dyspnea index was 7.1.

Patients received either a target oral MMF dosage of 1.5 g b.i.d. for 2 years, or a target cyclophosphamide dosage of 2 mg/kg/day for up to 1 year, followed by a year of placebo. Cyclophosphamide treatment was capped at 1 year to protect against causing malignancy. Among the 73 patients randomized to the cyclophosphamide arm, 58 had data available after 12 months with 48 patients continuing on cyclophosphamide, and 53 had data available out to 2 years, with 37 patients remaining on their assigned regimen. Among 69 patients randomized to MMF 58 had data available after 12 months with 53 continuing on MMF, and 53 patients had data available through 24 months with 49 remaining on their MMF regimen.

After 24 months, the average percent predicted forced vital capacity, the study’s primary endpoint, had increased by 3.3% among patients on MMF and 3.0% among those in the cyclophosphamide arm in an intention-to-treat analysis, a nonsignificant difference. After 24 months 72% of patients in the MMF arm and 65% in the cyclophosphamide arm had a positive change, compared with baseline, in their percent predicted forced vital capacity, Dr. Tashkin reported.

MMF also showed a superior overall safety profile. Patients on cyclophosphamide had a significantly increased rate of withdrawal from the study medication. Drug discontinuations occurred in 36 of the cyclophosphamide patients and in 20 of those on MMF. Serious adverse events attributable to study medication occurred in eight patients on cyclophosphamide and three patients on MMF. The most frequent protocol-defined adverse event was leukopenia, which occurred in 30 patients on cyclophosphamide and four patients on MMF.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – The immunosuppressant mycophenolate mofetil worked as effectively as cyclophosphamide for treating scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease while being better tolerated and causing fewer adverse effects in a multicenter, head-to-head comparison with 142 randomized patients.

“The findings support the increasingly common clinical practice of prescribing MMF [mycophenolate mofetil] for this disease,” said Dr. Donald P. Tashkin at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Another limitation of cyclophosphamide is that it is usually not used for more than 1 year because of concerns that longer use substantially increases a patient’s risk for developing malignancy. That’s another reason why there is a “strong need for longer and safer immunosuppressive treatment with a drug like MMF,” said Dr. Tashkin, a pulmonologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

When used in this trial on patients with scleroderma, as defined by the American College of Rheumatology and with a baseline forced vital capacity of no more than 80% of predicted, “MMF was effective at reducing the rate of decline in vital capacity, improving symptoms such as dyspnea – the cardinal symptom of interstitial lung disease, and reducing lung fibrosis seen on CT scans, and MMF was better tolerated” than cyclophosphamide, Dr. Tashkin said in an interview. Cyclophosphamide treatment in this new trial “was associated with more toxicity, especially hematologic toxicity, an was not nearly as well tolerated, with more patients withdrawing because of side effects or a perceived lack of benefit.”

“Cyclophosphamide has a lot of side effects. MMF is just now coming into increased use. I think we’ll see it being used more for first-line treatment because the side effects with cyclophosphamide are so bad,” commented Dr. Thomas Fuhrman, chief of anesthesiology at the Bay Pines (Fla.) VA Healthcare System.

Dr. Tashkin and his associates conceived the Scleroderma Lung Study II (SLSII) as a follow-up to the first SLS run about a decade ago that compared cyclosphosphamide against placebo for controlling progression of interstitial lung disease in scleroderma patients. The results from the first SLS trial established cyclosphosphamide as a treatment that could preserve forced vital capacity percent predicted in patients with scleroderma-induced interstitial lung disease (N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 22;354[25]:2655-666).

For the new study they enrolled patients who averaged 52 years old, with an average scleroderma duration of almost 3 years. Their average percent predicted forced vital capacity was 67%, and their baseline dyspnea index was 7.1.

Patients received either a target oral MMF dosage of 1.5 g b.i.d. for 2 years, or a target cyclophosphamide dosage of 2 mg/kg/day for up to 1 year, followed by a year of placebo. Cyclophosphamide treatment was capped at 1 year to protect against causing malignancy. Among the 73 patients randomized to the cyclophosphamide arm, 58 had data available after 12 months with 48 patients continuing on cyclophosphamide, and 53 had data available out to 2 years, with 37 patients remaining on their assigned regimen. Among 69 patients randomized to MMF 58 had data available after 12 months with 53 continuing on MMF, and 53 patients had data available through 24 months with 49 remaining on their MMF regimen.

After 24 months, the average percent predicted forced vital capacity, the study’s primary endpoint, had increased by 3.3% among patients on MMF and 3.0% among those in the cyclophosphamide arm in an intention-to-treat analysis, a nonsignificant difference. After 24 months 72% of patients in the MMF arm and 65% in the cyclophosphamide arm had a positive change, compared with baseline, in their percent predicted forced vital capacity, Dr. Tashkin reported.

MMF also showed a superior overall safety profile. Patients on cyclophosphamide had a significantly increased rate of withdrawal from the study medication. Drug discontinuations occurred in 36 of the cyclophosphamide patients and in 20 of those on MMF. Serious adverse events attributable to study medication occurred in eight patients on cyclophosphamide and three patients on MMF. The most frequent protocol-defined adverse event was leukopenia, which occurred in 30 patients on cyclophosphamide and four patients on MMF.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – The immunosuppressant mycophenolate mofetil worked as effectively as cyclophosphamide for treating scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease while being better tolerated and causing fewer adverse effects in a multicenter, head-to-head comparison with 142 randomized patients.

“The findings support the increasingly common clinical practice of prescribing MMF [mycophenolate mofetil] for this disease,” said Dr. Donald P. Tashkin at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Another limitation of cyclophosphamide is that it is usually not used for more than 1 year because of concerns that longer use substantially increases a patient’s risk for developing malignancy. That’s another reason why there is a “strong need for longer and safer immunosuppressive treatment with a drug like MMF,” said Dr. Tashkin, a pulmonologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

When used in this trial on patients with scleroderma, as defined by the American College of Rheumatology and with a baseline forced vital capacity of no more than 80% of predicted, “MMF was effective at reducing the rate of decline in vital capacity, improving symptoms such as dyspnea – the cardinal symptom of interstitial lung disease, and reducing lung fibrosis seen on CT scans, and MMF was better tolerated” than cyclophosphamide, Dr. Tashkin said in an interview. Cyclophosphamide treatment in this new trial “was associated with more toxicity, especially hematologic toxicity, an was not nearly as well tolerated, with more patients withdrawing because of side effects or a perceived lack of benefit.”

“Cyclophosphamide has a lot of side effects. MMF is just now coming into increased use. I think we’ll see it being used more for first-line treatment because the side effects with cyclophosphamide are so bad,” commented Dr. Thomas Fuhrman, chief of anesthesiology at the Bay Pines (Fla.) VA Healthcare System.

Dr. Tashkin and his associates conceived the Scleroderma Lung Study II (SLSII) as a follow-up to the first SLS run about a decade ago that compared cyclosphosphamide against placebo for controlling progression of interstitial lung disease in scleroderma patients. The results from the first SLS trial established cyclosphosphamide as a treatment that could preserve forced vital capacity percent predicted in patients with scleroderma-induced interstitial lung disease (N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 22;354[25]:2655-666).

For the new study they enrolled patients who averaged 52 years old, with an average scleroderma duration of almost 3 years. Their average percent predicted forced vital capacity was 67%, and their baseline dyspnea index was 7.1.

Patients received either a target oral MMF dosage of 1.5 g b.i.d. for 2 years, or a target cyclophosphamide dosage of 2 mg/kg/day for up to 1 year, followed by a year of placebo. Cyclophosphamide treatment was capped at 1 year to protect against causing malignancy. Among the 73 patients randomized to the cyclophosphamide arm, 58 had data available after 12 months with 48 patients continuing on cyclophosphamide, and 53 had data available out to 2 years, with 37 patients remaining on their assigned regimen. Among 69 patients randomized to MMF 58 had data available after 12 months with 53 continuing on MMF, and 53 patients had data available through 24 months with 49 remaining on their MMF regimen.

After 24 months, the average percent predicted forced vital capacity, the study’s primary endpoint, had increased by 3.3% among patients on MMF and 3.0% among those in the cyclophosphamide arm in an intention-to-treat analysis, a nonsignificant difference. After 24 months 72% of patients in the MMF arm and 65% in the cyclophosphamide arm had a positive change, compared with baseline, in their percent predicted forced vital capacity, Dr. Tashkin reported.

MMF also showed a superior overall safety profile. Patients on cyclophosphamide had a significantly increased rate of withdrawal from the study medication. Drug discontinuations occurred in 36 of the cyclophosphamide patients and in 20 of those on MMF. Serious adverse events attributable to study medication occurred in eight patients on cyclophosphamide and three patients on MMF. The most frequent protocol-defined adverse event was leukopenia, which occurred in 30 patients on cyclophosphamide and four patients on MMF.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT CHEST 2015

Key clinical point: Mycophenolate mofetil controlled scleroderma-induced interstitial lung disease as well as cyclosphosphamide did but with reduced toxicity.

Major finding: Average percent predicted forced vital capacity rose 3.0% in patients treated with cyclosphosphamide and 3.3% in those on MMF.

Data source: SLSII, a randomized trial that enrolled 142 scleroderma patients at 13 U.S. centers.

Disclosures: SLSII received partial funding from Hoffman-La Roche, a company that markets a formulation of mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept). Dr. Tashkin had no disclosures. Dr. Fuhrman had no disclosures.

Pediatric pertussis tied to minor elevation in epilepsy risk

Danish researchers reported a slightly heightened vulnerability to child-onset epilepsy in infants who contract pertussis, which strikes an estimated 16 million children globally on an annual basis, in a study published in the Nov. 3 issue of JAMA.

Dr. Morten Olsen of the department of clinical epidemiology, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, and his colleagues collected data from population-based medical registries encompassing every hospital and citizen in Denmark (roughly 5.6 million people) to catalogue all patients presenting with pertussis born between 1978 and 2011. Subjects were tracked for a maximum of 15 years, beginning with their respective initial pertussis diagnosis dates, up until their first-time epilepsy diagnosis, emigration, death, or Dec. 31, 2011 (whichever occurred first). To establish a control cohort, the national Danish Civil Registration System database was mined to identify and select 10 age- and sex-matched individuals from the general population for each patient with pertussis (JAMA. 2015 Nov 3;314[17]:1844-9).

Of the 4,700 identified pertussis patients (53% of whom were younger than 6 months of age when initially diagnosed with pertussis), 90 (2%) subsequently developed epilepsy (incidence rate, 1.56/1,000 person-years; 95% confidence interval, 1.55-1.57), compared with 511 (0.1%) in the 47,000-subject comparison arm (incidence rate, 0.88/1,000 person-years; 95% CI, 0.88-0.88). Pertussis patients were found to have a cumulative epilepsy incidence rate of 1.7% (95% CI, 1.4%-2.1%) at age 10 years; cumulative epilepsy incidence at age 10 years was 0.9% (95% CI, 0.8%-1%) in the control population. Moreover, epilepsy risk was demonstrated to be dependent on age of pertussis onset; a pertussis diagnosis was not associated with increased epilepsy risk in patients over the age of 3 years (hazard ratio, 1; 95% CI, 0.5-1.8).

According to study investigators, one explanation for the role that pertussis could potentially play in the pathophysiology of epilepsy may center on the occurrence of hypoxic brain damage resulting from severe pertussis-related coughing, “perhaps via increased intrathoracic and intra-abdominal pressure and central nervous system hemorrhages.”

The study was funded by the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure established by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The department of clinical epidemiology, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, receives funding for other studies from companies in the form of research grants.

Danish researchers reported a slightly heightened vulnerability to child-onset epilepsy in infants who contract pertussis, which strikes an estimated 16 million children globally on an annual basis, in a study published in the Nov. 3 issue of JAMA.

Dr. Morten Olsen of the department of clinical epidemiology, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, and his colleagues collected data from population-based medical registries encompassing every hospital and citizen in Denmark (roughly 5.6 million people) to catalogue all patients presenting with pertussis born between 1978 and 2011. Subjects were tracked for a maximum of 15 years, beginning with their respective initial pertussis diagnosis dates, up until their first-time epilepsy diagnosis, emigration, death, or Dec. 31, 2011 (whichever occurred first). To establish a control cohort, the national Danish Civil Registration System database was mined to identify and select 10 age- and sex-matched individuals from the general population for each patient with pertussis (JAMA. 2015 Nov 3;314[17]:1844-9).

Of the 4,700 identified pertussis patients (53% of whom were younger than 6 months of age when initially diagnosed with pertussis), 90 (2%) subsequently developed epilepsy (incidence rate, 1.56/1,000 person-years; 95% confidence interval, 1.55-1.57), compared with 511 (0.1%) in the 47,000-subject comparison arm (incidence rate, 0.88/1,000 person-years; 95% CI, 0.88-0.88). Pertussis patients were found to have a cumulative epilepsy incidence rate of 1.7% (95% CI, 1.4%-2.1%) at age 10 years; cumulative epilepsy incidence at age 10 years was 0.9% (95% CI, 0.8%-1%) in the control population. Moreover, epilepsy risk was demonstrated to be dependent on age of pertussis onset; a pertussis diagnosis was not associated with increased epilepsy risk in patients over the age of 3 years (hazard ratio, 1; 95% CI, 0.5-1.8).