User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

AHA: Spirometry identifies mortality risk in asymptomatic adults

ORLANDO – Unselected people from the general population without clinically apparent lung disease but with low lung function had significantly increased mortality during follow-up that was independent of cardiac function, in results from more than 13,000 middle-aged Germans.

“Subtle, subclinical pulmonary impairment is a risk indicator for increased mortality independent of cardiac performance,” Dr. Christina Baum said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The researchers used spirometry to measure each subject’s forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). The results showed that “spirometry is a good screening tool that is not very expensive,” making spirometry an effective risk assessment tool for use in the general adult population, said Dr. Baum of the department of general and interventional cardiology at the University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany.

She and her associates used data collected in the Gutenberg Health Study, which enrolled more than 15,000 German women and men aged 35-74 years during 2007-2012. The investigators excluded people with a history of pulmonary disease, resulting in a study cohort of 13,191, who averaged 55 years old, with 51% men.

At enrollment into the study, all people underwent screening spirometry and echocardiography. Their average baseline FEV1 was 2.9 L and their average FVC was 3.7 L, and 4% had heart failure based on assessments of left ventricular size and function by echocardiography. The first 5,000 enrollees also had measurements taken of their serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I through use of a high-sensitivity assay. The researchers used data from patients followed for a median of 5.5 years.

During follow-up, people in the lowest tertile for FEV1 and those in the lowest tertile for FVC had higher rates of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the highest tertile for each of these two parameters.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure status, serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I, and other parameters, people with lower FEV1 and FVC readings had significantly worse survival, Dr. Baum said. Every 1–standard deviation increase in FEV1 was linked with a statistically significant, 38% reduced mortality rate; furthermore, a similar significant inverse association existed between FVC and mortality, she reported.

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Unselected people from the general population without clinically apparent lung disease but with low lung function had significantly increased mortality during follow-up that was independent of cardiac function, in results from more than 13,000 middle-aged Germans.

“Subtle, subclinical pulmonary impairment is a risk indicator for increased mortality independent of cardiac performance,” Dr. Christina Baum said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The researchers used spirometry to measure each subject’s forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). The results showed that “spirometry is a good screening tool that is not very expensive,” making spirometry an effective risk assessment tool for use in the general adult population, said Dr. Baum of the department of general and interventional cardiology at the University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany.

She and her associates used data collected in the Gutenberg Health Study, which enrolled more than 15,000 German women and men aged 35-74 years during 2007-2012. The investigators excluded people with a history of pulmonary disease, resulting in a study cohort of 13,191, who averaged 55 years old, with 51% men.

At enrollment into the study, all people underwent screening spirometry and echocardiography. Their average baseline FEV1 was 2.9 L and their average FVC was 3.7 L, and 4% had heart failure based on assessments of left ventricular size and function by echocardiography. The first 5,000 enrollees also had measurements taken of their serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I through use of a high-sensitivity assay. The researchers used data from patients followed for a median of 5.5 years.

During follow-up, people in the lowest tertile for FEV1 and those in the lowest tertile for FVC had higher rates of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the highest tertile for each of these two parameters.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure status, serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I, and other parameters, people with lower FEV1 and FVC readings had significantly worse survival, Dr. Baum said. Every 1–standard deviation increase in FEV1 was linked with a statistically significant, 38% reduced mortality rate; furthermore, a similar significant inverse association existed between FVC and mortality, she reported.

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Unselected people from the general population without clinically apparent lung disease but with low lung function had significantly increased mortality during follow-up that was independent of cardiac function, in results from more than 13,000 middle-aged Germans.

“Subtle, subclinical pulmonary impairment is a risk indicator for increased mortality independent of cardiac performance,” Dr. Christina Baum said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The researchers used spirometry to measure each subject’s forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). The results showed that “spirometry is a good screening tool that is not very expensive,” making spirometry an effective risk assessment tool for use in the general adult population, said Dr. Baum of the department of general and interventional cardiology at the University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany.

She and her associates used data collected in the Gutenberg Health Study, which enrolled more than 15,000 German women and men aged 35-74 years during 2007-2012. The investigators excluded people with a history of pulmonary disease, resulting in a study cohort of 13,191, who averaged 55 years old, with 51% men.

At enrollment into the study, all people underwent screening spirometry and echocardiography. Their average baseline FEV1 was 2.9 L and their average FVC was 3.7 L, and 4% had heart failure based on assessments of left ventricular size and function by echocardiography. The first 5,000 enrollees also had measurements taken of their serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I through use of a high-sensitivity assay. The researchers used data from patients followed for a median of 5.5 years.

During follow-up, people in the lowest tertile for FEV1 and those in the lowest tertile for FVC had higher rates of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the highest tertile for each of these two parameters.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure status, serum levels of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I, and other parameters, people with lower FEV1 and FVC readings had significantly worse survival, Dr. Baum said. Every 1–standard deviation increase in FEV1 was linked with a statistically significant, 38% reduced mortality rate; furthermore, a similar significant inverse association existed between FVC and mortality, she reported.

On Twitter@mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Measurement of low FEV1 or low FVC by spirometry identified people at increased mortality risk independent of their cardiac function.

Major finding: For each standard deviation rise in FEV1, mortality fell by 38%.

Data source: The Gutenberg Heart Study, which enrolled 15,010 German residents aged 35-74 years old, including 13,191 without prevalent pulmonary disease.

Disclosures: Dr. Baum had no relevant financial disclosures.

Higher anemia risk for children with atopic disease

Children with a history of atopic disease (AD) are at a significantly higher risk for an anemia diagnosis than are children without AD, according to an analysis of two large U.S. population-based studies.

In addition, the risk of anemia increased with the number of caregiver-reported atopic disorders, reported the investigators, Dr. Jonathan I. Silverberg and his associates in the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. A current diagnosis of eczema or asthma was associated with a significantly increased risk of anemia, particularly microcytic anemia, in the study, published online on Nov. 30 in JAMA Pediatrics (doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3065).

The authors evaluated data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) on about 207,000 children and adolescents collected between 1997 and 2013, and from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) on nearly 31,000 children and adolescents between 1999 and 2012.

Data from the NHIS cohort found a significantly elevated anemia risk among children with a caregiver-reported history of hay fever, eczema, asthma, and food allergy (P less than .001 for all 4 disorders). After adjustments for age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, the anemia risk for a child with any single atopic disorder was modestly elevated (adjusted odds ratio, 1.84; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-2.11; P less than .001). The adjusted risk among those with all four disorders was markedly elevated (adjusted OR, 7.87; 95% CI, 5.17-12.00; P less than .001).

In the NHANES cohort, the investigators found a current asthma or eczema diagnosis associated with anemia, as defined by laboratory assessment (adjusted OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.04-1.70; P = .02 for asthma; and an adjusted OR 1.93; 95% CI, 1.04-3.59; P = .04 for eczema).

In the NHANES cohort, asthma was associated with an increased risk for microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 1.61; 95% CI 1.09-2.38 P = .02). In the 2005-2006 NHANES cohort, a history of eczema was associated with an increased risk of microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.20-3.46; P = .009). But no significant associations for hay fever and any type of anemia were noted.

While the reasons for the observed association between atopic disease and anemia remain unknown and are probably multifactorial, physicians “should be aware that fatigue may be related to unrecognized anemia and not merely sleep loss owing to atopic dermatitis or airway disease,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, they noted, restricted diets to treat atopic disorders could play a role. “This finding underscores the importance of properly evaluating and ruling out suspected food allergy in children rather than placing them on empirical avoidance diets that might contribute to anemia,” they said.

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Silverberg and his coauthors, Kerry E. Drury and Matt Schaeffer, declared no conflicts of interest.

Children with a history of atopic disease (AD) are at a significantly higher risk for an anemia diagnosis than are children without AD, according to an analysis of two large U.S. population-based studies.

In addition, the risk of anemia increased with the number of caregiver-reported atopic disorders, reported the investigators, Dr. Jonathan I. Silverberg and his associates in the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. A current diagnosis of eczema or asthma was associated with a significantly increased risk of anemia, particularly microcytic anemia, in the study, published online on Nov. 30 in JAMA Pediatrics (doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3065).

The authors evaluated data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) on about 207,000 children and adolescents collected between 1997 and 2013, and from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) on nearly 31,000 children and adolescents between 1999 and 2012.

Data from the NHIS cohort found a significantly elevated anemia risk among children with a caregiver-reported history of hay fever, eczema, asthma, and food allergy (P less than .001 for all 4 disorders). After adjustments for age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, the anemia risk for a child with any single atopic disorder was modestly elevated (adjusted odds ratio, 1.84; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-2.11; P less than .001). The adjusted risk among those with all four disorders was markedly elevated (adjusted OR, 7.87; 95% CI, 5.17-12.00; P less than .001).

In the NHANES cohort, the investigators found a current asthma or eczema diagnosis associated with anemia, as defined by laboratory assessment (adjusted OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.04-1.70; P = .02 for asthma; and an adjusted OR 1.93; 95% CI, 1.04-3.59; P = .04 for eczema).

In the NHANES cohort, asthma was associated with an increased risk for microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 1.61; 95% CI 1.09-2.38 P = .02). In the 2005-2006 NHANES cohort, a history of eczema was associated with an increased risk of microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.20-3.46; P = .009). But no significant associations for hay fever and any type of anemia were noted.

While the reasons for the observed association between atopic disease and anemia remain unknown and are probably multifactorial, physicians “should be aware that fatigue may be related to unrecognized anemia and not merely sleep loss owing to atopic dermatitis or airway disease,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, they noted, restricted diets to treat atopic disorders could play a role. “This finding underscores the importance of properly evaluating and ruling out suspected food allergy in children rather than placing them on empirical avoidance diets that might contribute to anemia,” they said.

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Silverberg and his coauthors, Kerry E. Drury and Matt Schaeffer, declared no conflicts of interest.

Children with a history of atopic disease (AD) are at a significantly higher risk for an anemia diagnosis than are children without AD, according to an analysis of two large U.S. population-based studies.

In addition, the risk of anemia increased with the number of caregiver-reported atopic disorders, reported the investigators, Dr. Jonathan I. Silverberg and his associates in the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago. A current diagnosis of eczema or asthma was associated with a significantly increased risk of anemia, particularly microcytic anemia, in the study, published online on Nov. 30 in JAMA Pediatrics (doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3065).

The authors evaluated data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) on about 207,000 children and adolescents collected between 1997 and 2013, and from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) on nearly 31,000 children and adolescents between 1999 and 2012.

Data from the NHIS cohort found a significantly elevated anemia risk among children with a caregiver-reported history of hay fever, eczema, asthma, and food allergy (P less than .001 for all 4 disorders). After adjustments for age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, the anemia risk for a child with any single atopic disorder was modestly elevated (adjusted odds ratio, 1.84; 95% confidence interval, 1.60-2.11; P less than .001). The adjusted risk among those with all four disorders was markedly elevated (adjusted OR, 7.87; 95% CI, 5.17-12.00; P less than .001).

In the NHANES cohort, the investigators found a current asthma or eczema diagnosis associated with anemia, as defined by laboratory assessment (adjusted OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.04-1.70; P = .02 for asthma; and an adjusted OR 1.93; 95% CI, 1.04-3.59; P = .04 for eczema).

In the NHANES cohort, asthma was associated with an increased risk for microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 1.61; 95% CI 1.09-2.38 P = .02). In the 2005-2006 NHANES cohort, a history of eczema was associated with an increased risk of microcytic anemia (adjusted OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.20-3.46; P = .009). But no significant associations for hay fever and any type of anemia were noted.

While the reasons for the observed association between atopic disease and anemia remain unknown and are probably multifactorial, physicians “should be aware that fatigue may be related to unrecognized anemia and not merely sleep loss owing to atopic dermatitis or airway disease,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, they noted, restricted diets to treat atopic disorders could play a role. “This finding underscores the importance of properly evaluating and ruling out suspected food allergy in children rather than placing them on empirical avoidance diets that might contribute to anemia,” they said.

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Silverberg and his coauthors, Kerry E. Drury and Matt Schaeffer, declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Children with atopic disorders are at a higher risk of anemia, which may be underrecognized in this population, and could be related to a restricted diet.

Major finding: Children with history of eczema, asthma, hay fever, or food allergy were at an increased risk of anemia, compared with children without these disorders (P less than .001 for all).

Data source: The study evaluated data on children and adolescents in the population-based U.S. National Health Interview Survey (207,007) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (30,673 children).

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Dermatology Foundation; the authors reported no conflicts.

AHA: HFpEF, HFrEF cause similar acute hospitalization rates

ORLANDO – The number of Americans hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) with preserved ejection fraction during 2003-2012 nearly equaled the number hospitalized with ADHF with reduced ejection fraction, in an analysis of more than 5 million hospitalized heart failure patients tracked in a national-sample database.

But the profile of patients hospitalized with ADHF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) differed from patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), with a substantially higher percentage of women and patients aged 75 years or older, Dr. Parag Goyal said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The analysis also showed the strongest correlate for in-hospital mortality among HFpEF patients hospitalized with acute decompensation was a pulmonary circulation disorder, such as pulmonary hypertension, which nearly doubled the rate of in-hospital death among HFpEF patients. Other strong correlates of mortality during hospitalization were liver disease, which was linked with about a 50% boost in hospitalized mortality; and chronic renal failure, which was tied to a roughly one-third higher mortality, said Dr. Goyal, a cardiologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital.

His study used data collected by the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, which included data on more than 388 million hospitalized U.S. patients during 2003-2012, including 5,046,879 hospitalized with acute heart failure. This total included 2,329,391 patients (46%) diagnosed with HFpEF and 2,717,488 patients (54%) diagnosed with HFrEF.

The HFpEF patients’ average age was 76 years, with 60% at least 75 years old, while the HFrEF patients’ average age was 72 years, with 49% age 75 years or older. Nearly two-thirds of the HFpEF patients were women, compared with 42% in the HFrEF group. The HFrEF patients also had a substantially higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, 59%, compared with 41% in the HFpEF group. The prevalence of several comorbidities – including diabetes, hypertension, and chronic renal failure – were each roughly similar in both subgroups, but the obesity rate of 19% in the HFpEF patients substantially exceeded the 12% rate in HFrEF patients.

In-hospital mortality ran 4.3% in the HFpEF patients and 5.1% in the HFrEF patients, a 13% relative-risk reduction that was statistically significant. But average length of stay was similar between the two groups, about 7 days with either type of heart failure.

Dr. Goyal and his associates also examined time trends during 2003-2012. During this period, the percentage of patients with HFpEF aged 75 years or older rose from 57% to 60%. Even more notably, the percentage of men with HFpEF rose from 31% in 2003 to 37% in 2012. Furthermore, the reduced in-hospital mortality during the period was largely driven by mortality reductions among HFpEF patients aged 65 years or older. A multivariate analysis for significant correlates of in-hospital mortality identified age 75 years or older, male sex, and white race in both the HFpEF subgroup and in those with HFrEF. Older age had the highest impact, linked with about a 60% relatively higher mortality rate in patients with either type of heart failure.

The multivariate analysis also identified three comorbidities linked with in-hospital mortality. A pulmonary circulation disorder was associated with a 90% higher mortality rate among HFpEF patients and a 79% higher rate among those with HFrEF. Liver disease and chronic renal disease linked with smaller mortality increases for both heart failure types. The presence of treatable comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease, linked with significantly lower in-hospital mortality rates. Dr. Goyal speculated that the reduced mortality resulted from successful treatment of these conditions.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – The number of Americans hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) with preserved ejection fraction during 2003-2012 nearly equaled the number hospitalized with ADHF with reduced ejection fraction, in an analysis of more than 5 million hospitalized heart failure patients tracked in a national-sample database.

But the profile of patients hospitalized with ADHF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) differed from patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), with a substantially higher percentage of women and patients aged 75 years or older, Dr. Parag Goyal said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The analysis also showed the strongest correlate for in-hospital mortality among HFpEF patients hospitalized with acute decompensation was a pulmonary circulation disorder, such as pulmonary hypertension, which nearly doubled the rate of in-hospital death among HFpEF patients. Other strong correlates of mortality during hospitalization were liver disease, which was linked with about a 50% boost in hospitalized mortality; and chronic renal failure, which was tied to a roughly one-third higher mortality, said Dr. Goyal, a cardiologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital.

His study used data collected by the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, which included data on more than 388 million hospitalized U.S. patients during 2003-2012, including 5,046,879 hospitalized with acute heart failure. This total included 2,329,391 patients (46%) diagnosed with HFpEF and 2,717,488 patients (54%) diagnosed with HFrEF.

The HFpEF patients’ average age was 76 years, with 60% at least 75 years old, while the HFrEF patients’ average age was 72 years, with 49% age 75 years or older. Nearly two-thirds of the HFpEF patients were women, compared with 42% in the HFrEF group. The HFrEF patients also had a substantially higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, 59%, compared with 41% in the HFpEF group. The prevalence of several comorbidities – including diabetes, hypertension, and chronic renal failure – were each roughly similar in both subgroups, but the obesity rate of 19% in the HFpEF patients substantially exceeded the 12% rate in HFrEF patients.

In-hospital mortality ran 4.3% in the HFpEF patients and 5.1% in the HFrEF patients, a 13% relative-risk reduction that was statistically significant. But average length of stay was similar between the two groups, about 7 days with either type of heart failure.

Dr. Goyal and his associates also examined time trends during 2003-2012. During this period, the percentage of patients with HFpEF aged 75 years or older rose from 57% to 60%. Even more notably, the percentage of men with HFpEF rose from 31% in 2003 to 37% in 2012. Furthermore, the reduced in-hospital mortality during the period was largely driven by mortality reductions among HFpEF patients aged 65 years or older. A multivariate analysis for significant correlates of in-hospital mortality identified age 75 years or older, male sex, and white race in both the HFpEF subgroup and in those with HFrEF. Older age had the highest impact, linked with about a 60% relatively higher mortality rate in patients with either type of heart failure.

The multivariate analysis also identified three comorbidities linked with in-hospital mortality. A pulmonary circulation disorder was associated with a 90% higher mortality rate among HFpEF patients and a 79% higher rate among those with HFrEF. Liver disease and chronic renal disease linked with smaller mortality increases for both heart failure types. The presence of treatable comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease, linked with significantly lower in-hospital mortality rates. Dr. Goyal speculated that the reduced mortality resulted from successful treatment of these conditions.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – The number of Americans hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) with preserved ejection fraction during 2003-2012 nearly equaled the number hospitalized with ADHF with reduced ejection fraction, in an analysis of more than 5 million hospitalized heart failure patients tracked in a national-sample database.

But the profile of patients hospitalized with ADHF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) differed from patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), with a substantially higher percentage of women and patients aged 75 years or older, Dr. Parag Goyal said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The analysis also showed the strongest correlate for in-hospital mortality among HFpEF patients hospitalized with acute decompensation was a pulmonary circulation disorder, such as pulmonary hypertension, which nearly doubled the rate of in-hospital death among HFpEF patients. Other strong correlates of mortality during hospitalization were liver disease, which was linked with about a 50% boost in hospitalized mortality; and chronic renal failure, which was tied to a roughly one-third higher mortality, said Dr. Goyal, a cardiologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital.

His study used data collected by the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, which included data on more than 388 million hospitalized U.S. patients during 2003-2012, including 5,046,879 hospitalized with acute heart failure. This total included 2,329,391 patients (46%) diagnosed with HFpEF and 2,717,488 patients (54%) diagnosed with HFrEF.

The HFpEF patients’ average age was 76 years, with 60% at least 75 years old, while the HFrEF patients’ average age was 72 years, with 49% age 75 years or older. Nearly two-thirds of the HFpEF patients were women, compared with 42% in the HFrEF group. The HFrEF patients also had a substantially higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, 59%, compared with 41% in the HFpEF group. The prevalence of several comorbidities – including diabetes, hypertension, and chronic renal failure – were each roughly similar in both subgroups, but the obesity rate of 19% in the HFpEF patients substantially exceeded the 12% rate in HFrEF patients.

In-hospital mortality ran 4.3% in the HFpEF patients and 5.1% in the HFrEF patients, a 13% relative-risk reduction that was statistically significant. But average length of stay was similar between the two groups, about 7 days with either type of heart failure.

Dr. Goyal and his associates also examined time trends during 2003-2012. During this period, the percentage of patients with HFpEF aged 75 years or older rose from 57% to 60%. Even more notably, the percentage of men with HFpEF rose from 31% in 2003 to 37% in 2012. Furthermore, the reduced in-hospital mortality during the period was largely driven by mortality reductions among HFpEF patients aged 65 years or older. A multivariate analysis for significant correlates of in-hospital mortality identified age 75 years or older, male sex, and white race in both the HFpEF subgroup and in those with HFrEF. Older age had the highest impact, linked with about a 60% relatively higher mortality rate in patients with either type of heart failure.

The multivariate analysis also identified three comorbidities linked with in-hospital mortality. A pulmonary circulation disorder was associated with a 90% higher mortality rate among HFpEF patients and a 79% higher rate among those with HFrEF. Liver disease and chronic renal disease linked with smaller mortality increases for both heart failure types. The presence of treatable comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease, linked with significantly lower in-hospital mortality rates. Dr. Goyal speculated that the reduced mortality resulted from successful treatment of these conditions.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction closely tracked to heart failure with reduced ejection fraction for causing U.S. heart failure hospitalizations.

Major finding: Among U.S. heart failure patients hospitalized during 2003-2012, 46% had preserved ejection fraction and 54% had reduced ejection fraction.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 5 million U.S. patients hospitalized for heart failure during 2003-2012 and included in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Disclosures: Dr. Goyal had no disclosures.

AHA: Asthma History Boosts Heart Disease Risk in Postmenopausal Women

ORLANDO – A history of asthma was independently associated with a 24% increase in the risk of new-onset coronary heart disease among postmenopausal women in an analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative.

The study cohort included 90,168 women aged 50-79 years who were free of cardiovascular disease at enrollment in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), of whom 6,921 reported a history of physician-diagnosed asthma at baseline. During follow-up in the prospective study, the incidence of a CHD event was 8.6% in subjects with a history of asthma and 6.97% in the no-asthma group, Dr. Fady Y. Marmoush reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Moreover, the incidence of a first cardiovascular event was 11.6% in the asthma group, compared with 9.7% in the no-asthma controls, added Dr. Marmoush of Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Pawtucket.

The asthma group had an absolute 1%-2% greater baseline prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and family history of CHD. Those with asthma also were more likely to be obese. On the other hand, they were less likely to have ever smoked.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these and other potential confounders, including age, dyslipidemia, and waist-hip ratio, the women with a history of asthma had a 24% greater risk of CHD during prospective follow-up in the WHI, as well as a 21% increased rate of cardiovascular events, including stroke, compared with the no-asthma group.

Thus, a history of asthma could be a useful consideration – a tie breaker of sorts – in older women whose calculated 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk based on the standard risk factors places them on the borderline as candidates for statin therapy. The most likely mechanism for the observed association between asthma history and increased risk of cardiovascular disease is the chronic inflammatory state that’s a hallmark of asthma accelerating the atherosclerotic process, which also is inflammatory, she said.

The WHI is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Marmoush reported having no financial conflicts.

ORLANDO – A history of asthma was independently associated with a 24% increase in the risk of new-onset coronary heart disease among postmenopausal women in an analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative.

The study cohort included 90,168 women aged 50-79 years who were free of cardiovascular disease at enrollment in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), of whom 6,921 reported a history of physician-diagnosed asthma at baseline. During follow-up in the prospective study, the incidence of a CHD event was 8.6% in subjects with a history of asthma and 6.97% in the no-asthma group, Dr. Fady Y. Marmoush reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Moreover, the incidence of a first cardiovascular event was 11.6% in the asthma group, compared with 9.7% in the no-asthma controls, added Dr. Marmoush of Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Pawtucket.

The asthma group had an absolute 1%-2% greater baseline prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and family history of CHD. Those with asthma also were more likely to be obese. On the other hand, they were less likely to have ever smoked.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these and other potential confounders, including age, dyslipidemia, and waist-hip ratio, the women with a history of asthma had a 24% greater risk of CHD during prospective follow-up in the WHI, as well as a 21% increased rate of cardiovascular events, including stroke, compared with the no-asthma group.

Thus, a history of asthma could be a useful consideration – a tie breaker of sorts – in older women whose calculated 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk based on the standard risk factors places them on the borderline as candidates for statin therapy. The most likely mechanism for the observed association between asthma history and increased risk of cardiovascular disease is the chronic inflammatory state that’s a hallmark of asthma accelerating the atherosclerotic process, which also is inflammatory, she said.

The WHI is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Marmoush reported having no financial conflicts.

ORLANDO – A history of asthma was independently associated with a 24% increase in the risk of new-onset coronary heart disease among postmenopausal women in an analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative.

The study cohort included 90,168 women aged 50-79 years who were free of cardiovascular disease at enrollment in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), of whom 6,921 reported a history of physician-diagnosed asthma at baseline. During follow-up in the prospective study, the incidence of a CHD event was 8.6% in subjects with a history of asthma and 6.97% in the no-asthma group, Dr. Fady Y. Marmoush reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Moreover, the incidence of a first cardiovascular event was 11.6% in the asthma group, compared with 9.7% in the no-asthma controls, added Dr. Marmoush of Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Pawtucket.

The asthma group had an absolute 1%-2% greater baseline prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and family history of CHD. Those with asthma also were more likely to be obese. On the other hand, they were less likely to have ever smoked.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these and other potential confounders, including age, dyslipidemia, and waist-hip ratio, the women with a history of asthma had a 24% greater risk of CHD during prospective follow-up in the WHI, as well as a 21% increased rate of cardiovascular events, including stroke, compared with the no-asthma group.

Thus, a history of asthma could be a useful consideration – a tie breaker of sorts – in older women whose calculated 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk based on the standard risk factors places them on the borderline as candidates for statin therapy. The most likely mechanism for the observed association between asthma history and increased risk of cardiovascular disease is the chronic inflammatory state that’s a hallmark of asthma accelerating the atherosclerotic process, which also is inflammatory, she said.

The WHI is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Marmoush reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

AHA: Asthma history boosts heart disease risk in postmenopausal women

ORLANDO – A history of asthma was independently associated with a 24% increase in the risk of new-onset coronary heart disease among postmenopausal women in an analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative.

The study cohort included 90,168 women aged 50-79 years who were free of cardiovascular disease at enrollment in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), of whom 6,921 reported a history of physician-diagnosed asthma at baseline. During follow-up in the prospective study, the incidence of a CHD event was 8.6% in subjects with a history of asthma and 6.97% in the no-asthma group, Dr. Fady Y. Marmoush reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Moreover, the incidence of a first cardiovascular event was 11.6% in the asthma group, compared with 9.7% in the no-asthma controls, added Dr. Marmoush of Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Pawtucket.

The asthma group had an absolute 1%-2% greater baseline prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and family history of CHD. Those with asthma also were more likely to be obese. On the other hand, they were less likely to have ever smoked.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these and other potential confounders, including age, dyslipidemia, and waist-hip ratio, the women with a history of asthma had a 24% greater risk of CHD during prospective follow-up in the WHI, as well as a 21% increased rate of cardiovascular events, including stroke, compared with the no-asthma group.

Thus, a history of asthma could be a useful consideration – a tie breaker of sorts – in older women whose calculated 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk based on the standard risk factors places them on the borderline as candidates for statin therapy. The most likely mechanism for the observed association between asthma history and increased risk of cardiovascular disease is the chronic inflammatory state that’s a hallmark of asthma accelerating the atherosclerotic process, which also is inflammatory, she said.

The WHI is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Marmoush reported having no financial conflicts.

ORLANDO – A history of asthma was independently associated with a 24% increase in the risk of new-onset coronary heart disease among postmenopausal women in an analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative.

The study cohort included 90,168 women aged 50-79 years who were free of cardiovascular disease at enrollment in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), of whom 6,921 reported a history of physician-diagnosed asthma at baseline. During follow-up in the prospective study, the incidence of a CHD event was 8.6% in subjects with a history of asthma and 6.97% in the no-asthma group, Dr. Fady Y. Marmoush reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Moreover, the incidence of a first cardiovascular event was 11.6% in the asthma group, compared with 9.7% in the no-asthma controls, added Dr. Marmoush of Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Pawtucket.

The asthma group had an absolute 1%-2% greater baseline prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and family history of CHD. Those with asthma also were more likely to be obese. On the other hand, they were less likely to have ever smoked.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these and other potential confounders, including age, dyslipidemia, and waist-hip ratio, the women with a history of asthma had a 24% greater risk of CHD during prospective follow-up in the WHI, as well as a 21% increased rate of cardiovascular events, including stroke, compared with the no-asthma group.

Thus, a history of asthma could be a useful consideration – a tie breaker of sorts – in older women whose calculated 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk based on the standard risk factors places them on the borderline as candidates for statin therapy. The most likely mechanism for the observed association between asthma history and increased risk of cardiovascular disease is the chronic inflammatory state that’s a hallmark of asthma accelerating the atherosclerotic process, which also is inflammatory, she said.

The WHI is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Marmoush reported having no financial conflicts.

ORLANDO – A history of asthma was independently associated with a 24% increase in the risk of new-onset coronary heart disease among postmenopausal women in an analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative.

The study cohort included 90,168 women aged 50-79 years who were free of cardiovascular disease at enrollment in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), of whom 6,921 reported a history of physician-diagnosed asthma at baseline. During follow-up in the prospective study, the incidence of a CHD event was 8.6% in subjects with a history of asthma and 6.97% in the no-asthma group, Dr. Fady Y. Marmoush reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Moreover, the incidence of a first cardiovascular event was 11.6% in the asthma group, compared with 9.7% in the no-asthma controls, added Dr. Marmoush of Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Pawtucket.

The asthma group had an absolute 1%-2% greater baseline prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and family history of CHD. Those with asthma also were more likely to be obese. On the other hand, they were less likely to have ever smoked.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these and other potential confounders, including age, dyslipidemia, and waist-hip ratio, the women with a history of asthma had a 24% greater risk of CHD during prospective follow-up in the WHI, as well as a 21% increased rate of cardiovascular events, including stroke, compared with the no-asthma group.

Thus, a history of asthma could be a useful consideration – a tie breaker of sorts – in older women whose calculated 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk based on the standard risk factors places them on the borderline as candidates for statin therapy. The most likely mechanism for the observed association between asthma history and increased risk of cardiovascular disease is the chronic inflammatory state that’s a hallmark of asthma accelerating the atherosclerotic process, which also is inflammatory, she said.

The WHI is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Marmoush reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A history of asthma appears to substantially increase the risk of a first cardiovascular event in postmenopausal women.

Major finding: In a multivariate analysis adjusted for conventional cardiovascular risk factors, older women with a history of asthma had a 24% higher risk for a first coronary heart disease event and 21% greater risk of a cardiovascular event than those without such a history.

Data source: The Women’s Health Initiative is a prospective cohort study. This analysis included 90,168 women aged 50-79 at enrollment, of whom 6,921 reported a history of physician-diagnosed asthma.

Disclosures: The study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Prime-boost flu vaccination strategy effective in children

A prime-boost flu vaccination strategy proved effective in children and adolescents in an open-label phase III trial conducted by the vaccine manufacturer and reported online in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

This proof-of-concept result suggests that at the outbreak of the next flu pandemic, immediate priming with two doses of a subtype-matched flu vaccine, followed by boosting once a strain-matched vaccine becomes available, will offer the pediatric population better protection than simply waiting for adequate quantities of the strain-matched vaccine to be developed and marketed.

It is impossible to predict which specific viral strain will cause the next flu pandemic, but H5N1 is considered a likely candidate virus, “to the extent that vaccine manufacturers and regulatory authorities are actively developing H5N1 vaccines” for all age groups, said Dr. Patricia Izurieta of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Belgium, and her associates.

Waiting for a pandemic to begin and then producing strain-specific vaccines could take as long as 6 months, and even then supplies probably would be limited. Experts have theorized that preemptive “priming” with already stockpiled H5N1 vaccines immediately after a pandemic begins may provide broad cross-protection that could mitigate the intensity of the subsequent pandemic, potentially reducing morbidity, mortality, and viral transmission.

To test this theory, Dr. Izurieta and her associates mimicked a potential flu pandemic by priming children and adolescents with two doses of an H5N1-AS03 vaccine, giving a booster dose of a specific H5N1 strain at 6 months, and assessing antibody response to all the vaccinations through 12 months. (Assessing actual vaccine efficacy was impossible because it would be unethical to determine this by exposing children to a flu virus.)

A total of 520 participants at a single medical center in the Philippines who were aged 3-18 years (mean age, 9 years) were assigned to two intervention groups and two control groups. Approximately half of these children and adolescents received the intervention – two priming doses of A/Indonesia/05/2005/H5N1-AS03B vaccine – while the control subjects received a single dose of hepatitis A vaccine. At day 182, half of the primed and half of the unprimed participants then received a booster dose of A/turkey/Turkey/01/2005-H5N1-As03B, while the remainder received the hepatitis A vaccine.

Compared with no priming, priming afforded superior seroconversion and putative seroprotection against the second, specific strain of H5N1. This robust protective effect was seen within 10 days after vaccination, occurred across all ages, and persisted through 12 months of follow-up, the investigators said (Ped Infect Dis J. 2015 Nov 6. [doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000968]).

Adverse events within 7 days of the priming vaccinations developed in 68%-76% of the intervention group, compared with only 37%-64% of the control group. Adverse events within 7 days of the booster vaccinations developed in 69% of the intervention group, compared with only 40% of the control group. The most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection (20% vs 14%), nasopharyngitis (4% vs 3%), and rhinitis (3% in both study groups). The most serious adverse events affected two children and were classified as grade 3.

The study results suggest that a prime-boost strategy can induce broad and long-lasting immunity and could be effectively employed in this age group in the prepandemic setting, Dr. Izurieta and her associates reported.

This trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which also was involved in the design and conduct of the study, the data analysis, and the writing and publishing of the report. Dr. Izurieta and two of her associates are employed by GSK.

A prime-boost flu vaccination strategy proved effective in children and adolescents in an open-label phase III trial conducted by the vaccine manufacturer and reported online in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

This proof-of-concept result suggests that at the outbreak of the next flu pandemic, immediate priming with two doses of a subtype-matched flu vaccine, followed by boosting once a strain-matched vaccine becomes available, will offer the pediatric population better protection than simply waiting for adequate quantities of the strain-matched vaccine to be developed and marketed.

It is impossible to predict which specific viral strain will cause the next flu pandemic, but H5N1 is considered a likely candidate virus, “to the extent that vaccine manufacturers and regulatory authorities are actively developing H5N1 vaccines” for all age groups, said Dr. Patricia Izurieta of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Belgium, and her associates.

Waiting for a pandemic to begin and then producing strain-specific vaccines could take as long as 6 months, and even then supplies probably would be limited. Experts have theorized that preemptive “priming” with already stockpiled H5N1 vaccines immediately after a pandemic begins may provide broad cross-protection that could mitigate the intensity of the subsequent pandemic, potentially reducing morbidity, mortality, and viral transmission.

To test this theory, Dr. Izurieta and her associates mimicked a potential flu pandemic by priming children and adolescents with two doses of an H5N1-AS03 vaccine, giving a booster dose of a specific H5N1 strain at 6 months, and assessing antibody response to all the vaccinations through 12 months. (Assessing actual vaccine efficacy was impossible because it would be unethical to determine this by exposing children to a flu virus.)

A total of 520 participants at a single medical center in the Philippines who were aged 3-18 years (mean age, 9 years) were assigned to two intervention groups and two control groups. Approximately half of these children and adolescents received the intervention – two priming doses of A/Indonesia/05/2005/H5N1-AS03B vaccine – while the control subjects received a single dose of hepatitis A vaccine. At day 182, half of the primed and half of the unprimed participants then received a booster dose of A/turkey/Turkey/01/2005-H5N1-As03B, while the remainder received the hepatitis A vaccine.

Compared with no priming, priming afforded superior seroconversion and putative seroprotection against the second, specific strain of H5N1. This robust protective effect was seen within 10 days after vaccination, occurred across all ages, and persisted through 12 months of follow-up, the investigators said (Ped Infect Dis J. 2015 Nov 6. [doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000968]).

Adverse events within 7 days of the priming vaccinations developed in 68%-76% of the intervention group, compared with only 37%-64% of the control group. Adverse events within 7 days of the booster vaccinations developed in 69% of the intervention group, compared with only 40% of the control group. The most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection (20% vs 14%), nasopharyngitis (4% vs 3%), and rhinitis (3% in both study groups). The most serious adverse events affected two children and were classified as grade 3.

The study results suggest that a prime-boost strategy can induce broad and long-lasting immunity and could be effectively employed in this age group in the prepandemic setting, Dr. Izurieta and her associates reported.

This trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which also was involved in the design and conduct of the study, the data analysis, and the writing and publishing of the report. Dr. Izurieta and two of her associates are employed by GSK.

A prime-boost flu vaccination strategy proved effective in children and adolescents in an open-label phase III trial conducted by the vaccine manufacturer and reported online in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

This proof-of-concept result suggests that at the outbreak of the next flu pandemic, immediate priming with two doses of a subtype-matched flu vaccine, followed by boosting once a strain-matched vaccine becomes available, will offer the pediatric population better protection than simply waiting for adequate quantities of the strain-matched vaccine to be developed and marketed.

It is impossible to predict which specific viral strain will cause the next flu pandemic, but H5N1 is considered a likely candidate virus, “to the extent that vaccine manufacturers and regulatory authorities are actively developing H5N1 vaccines” for all age groups, said Dr. Patricia Izurieta of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Belgium, and her associates.

Waiting for a pandemic to begin and then producing strain-specific vaccines could take as long as 6 months, and even then supplies probably would be limited. Experts have theorized that preemptive “priming” with already stockpiled H5N1 vaccines immediately after a pandemic begins may provide broad cross-protection that could mitigate the intensity of the subsequent pandemic, potentially reducing morbidity, mortality, and viral transmission.

To test this theory, Dr. Izurieta and her associates mimicked a potential flu pandemic by priming children and adolescents with two doses of an H5N1-AS03 vaccine, giving a booster dose of a specific H5N1 strain at 6 months, and assessing antibody response to all the vaccinations through 12 months. (Assessing actual vaccine efficacy was impossible because it would be unethical to determine this by exposing children to a flu virus.)

A total of 520 participants at a single medical center in the Philippines who were aged 3-18 years (mean age, 9 years) were assigned to two intervention groups and two control groups. Approximately half of these children and adolescents received the intervention – two priming doses of A/Indonesia/05/2005/H5N1-AS03B vaccine – while the control subjects received a single dose of hepatitis A vaccine. At day 182, half of the primed and half of the unprimed participants then received a booster dose of A/turkey/Turkey/01/2005-H5N1-As03B, while the remainder received the hepatitis A vaccine.

Compared with no priming, priming afforded superior seroconversion and putative seroprotection against the second, specific strain of H5N1. This robust protective effect was seen within 10 days after vaccination, occurred across all ages, and persisted through 12 months of follow-up, the investigators said (Ped Infect Dis J. 2015 Nov 6. [doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000968]).

Adverse events within 7 days of the priming vaccinations developed in 68%-76% of the intervention group, compared with only 37%-64% of the control group. Adverse events within 7 days of the booster vaccinations developed in 69% of the intervention group, compared with only 40% of the control group. The most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection (20% vs 14%), nasopharyngitis (4% vs 3%), and rhinitis (3% in both study groups). The most serious adverse events affected two children and were classified as grade 3.

The study results suggest that a prime-boost strategy can induce broad and long-lasting immunity and could be effectively employed in this age group in the prepandemic setting, Dr. Izurieta and her associates reported.

This trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which also was involved in the design and conduct of the study, the data analysis, and the writing and publishing of the report. Dr. Izurieta and two of her associates are employed by GSK.

FROM THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASE JOURNAL

Key clinical point: A prime-boost flu vaccination strategy was found effective in children and adolescents.

Major finding: Compared with no priming, priming afforded superior seroconversion and putative seroprotection against the second, specific strain of H5N1.

Data source: An industry-sponsored, single-center, open-label phase III trial involving 520 participants aged 3-18 years followed for 1 year.

Disclosures: This trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, which also was involved in the design and conduct of the study, the data analysis, and the writing and publishing of the report. Dr. Izurieta and two of her associates are employed by GSK.

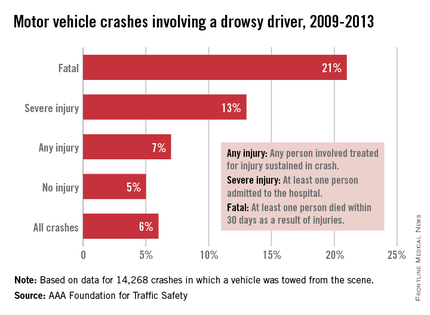

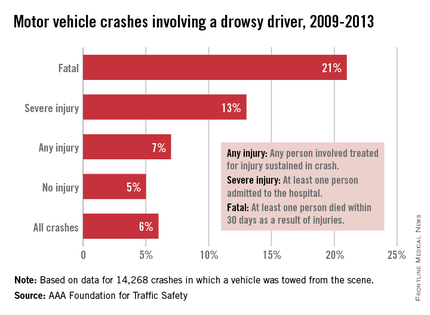

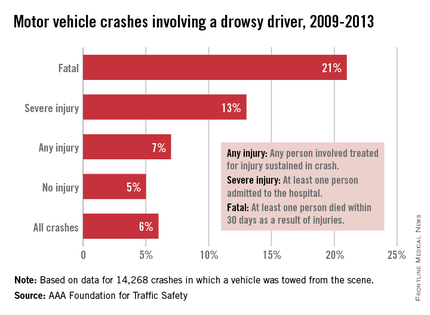

Sleep medicine specialists issue statement on drowsy driving

In an effort to combat drowsy driving, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine is calling for better education on the symptoms.

The organization also is calling for more research to understand the thresholds for when sleepiness while driving becomes dangerous.

“Driving while drowsy can have the same consequences as driving while under the influence of drugs and alcohol: drowsiness is similar to alcohol in how it compromises driving ability by reducing alertness and attentiveness, delaying reaction times, and hindering decision-making skills,” the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) said in a policy statement published Nov. 11, 2015, in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine (doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5200).

AASM is incorporating drowsy driving education online as part of its broader National Healthy Sleep Awareness Project.

The group identified a number of symptoms of drowsy driving, including frequent yawning or difficulty keeping eyes open, “nodding off” or difficulty keeping your head up, inability to remember driving the last few miles, missing road signs or turns, difficulty maintaining speed, and drifting out of your driving lane.

AASM is calling for collaboration among sleep physicians, state departments of motor vehicles and licensing, highway patrol, and the insurance industry to develop policies and procedures that reduce drowsy driving, educational material to be used in driver’s education and licensing examination, drowsy driving educational insurance discount programs, and manufacturing and infrastructure technologies that mitigate drowsy driving.

In addition, AASM “encourages more research that better defines indicators of drowsy driving, identifies the threshold at which sleepiness while driving becomes dangerous, and provides the public with simple methods to determine when they might be too tired to drive safely.”

It also warned that consumption of caffeine can temporarily increase alertness but is not a substitute for healthy sleep, and things like turning on the radio, opening the window, or turning on the air conditioner “are not effective techniques for staying awake while driving.”

In an effort to combat drowsy driving, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine is calling for better education on the symptoms.

The organization also is calling for more research to understand the thresholds for when sleepiness while driving becomes dangerous.

“Driving while drowsy can have the same consequences as driving while under the influence of drugs and alcohol: drowsiness is similar to alcohol in how it compromises driving ability by reducing alertness and attentiveness, delaying reaction times, and hindering decision-making skills,” the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) said in a policy statement published Nov. 11, 2015, in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine (doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5200).

AASM is incorporating drowsy driving education online as part of its broader National Healthy Sleep Awareness Project.

The group identified a number of symptoms of drowsy driving, including frequent yawning or difficulty keeping eyes open, “nodding off” or difficulty keeping your head up, inability to remember driving the last few miles, missing road signs or turns, difficulty maintaining speed, and drifting out of your driving lane.

AASM is calling for collaboration among sleep physicians, state departments of motor vehicles and licensing, highway patrol, and the insurance industry to develop policies and procedures that reduce drowsy driving, educational material to be used in driver’s education and licensing examination, drowsy driving educational insurance discount programs, and manufacturing and infrastructure technologies that mitigate drowsy driving.

In addition, AASM “encourages more research that better defines indicators of drowsy driving, identifies the threshold at which sleepiness while driving becomes dangerous, and provides the public with simple methods to determine when they might be too tired to drive safely.”

It also warned that consumption of caffeine can temporarily increase alertness but is not a substitute for healthy sleep, and things like turning on the radio, opening the window, or turning on the air conditioner “are not effective techniques for staying awake while driving.”

In an effort to combat drowsy driving, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine is calling for better education on the symptoms.

The organization also is calling for more research to understand the thresholds for when sleepiness while driving becomes dangerous.

“Driving while drowsy can have the same consequences as driving while under the influence of drugs and alcohol: drowsiness is similar to alcohol in how it compromises driving ability by reducing alertness and attentiveness, delaying reaction times, and hindering decision-making skills,” the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) said in a policy statement published Nov. 11, 2015, in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine (doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5200).

AASM is incorporating drowsy driving education online as part of its broader National Healthy Sleep Awareness Project.

The group identified a number of symptoms of drowsy driving, including frequent yawning or difficulty keeping eyes open, “nodding off” or difficulty keeping your head up, inability to remember driving the last few miles, missing road signs or turns, difficulty maintaining speed, and drifting out of your driving lane.

AASM is calling for collaboration among sleep physicians, state departments of motor vehicles and licensing, highway patrol, and the insurance industry to develop policies and procedures that reduce drowsy driving, educational material to be used in driver’s education and licensing examination, drowsy driving educational insurance discount programs, and manufacturing and infrastructure technologies that mitigate drowsy driving.

In addition, AASM “encourages more research that better defines indicators of drowsy driving, identifies the threshold at which sleepiness while driving becomes dangerous, and provides the public with simple methods to determine when they might be too tired to drive safely.”

It also warned that consumption of caffeine can temporarily increase alertness but is not a substitute for healthy sleep, and things like turning on the radio, opening the window, or turning on the air conditioner “are not effective techniques for staying awake while driving.”

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL SLEEP MEDICINE

Hold the checkpoint inhibitors when pneumonitis symptoms occur

BOSTON – Treatment of pneumonitis associated with the PD-1 axis checkpoint inhibitors requires close monitoring of patients and rapid clinical response, an oncologist advised.

“We need to be vigilant when we treat our patients. If a patient has cough or shortness of breath, you take it seriously, even if [it is] a patient who has lung cancer and is a smoker,” said Dr. Scott Gettinger of Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn.

He recommended that before starting patients on a programmed death-1 (PD-1) axis inhibitor such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or nivolumab (Opdivo), clinicians get baseline oxygen saturation levels to obtain an objective measure for following patients during therapy.

“When you suspect pneumonitis you have to start steroids right away, or patients can spiral down,” he said at the AACR/NCI/EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics.

Pneumonitis – characterized by cough, dyspnea, and hypoxia – is a common adverse event associated with PD-1 and PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, but is rarely seen in patients treated with CTLA-4 inhibitors such as ipilimumab (Yervoy). Current evidence suggests that pneumonitis is more prevalent in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, occurring in approximately 4%-6% of patients cases, than in melanoma (1%). The difference is probably due to a history of smoking common to the majority of patients with NSCLC, Dr. Gettinger said.

“The other theme that we’re beginning to see is that maybe pneumonitis is a bit more common with anti-PD-1 vs. anti-PD-L1 antibodies,” he said.

It’s theorized that PD-1 inhibitors may block binding of PD-L2 to one of its binding partners, thereby interfering with respiratory tolerance, he said.

Evidence from the pivotal clinical trial of nivolumab in lung cancer (Checkmate 057) suggests that the time to onset of pneumonitis was a median of 31.1 weeks (range 11.7 to 56.9 weeks). The pneumonitis resolved in about 5-7 weeks.

Investigators at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City reported at the European Cancer Congress 2015 on pneumonitis in 36 of 653 patients treated with an anti PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibody from 2009 through 2014, 33 of whom had received a PD-1 inhibitor, and 3 of whom received a PD-L1 inhibitor.

They found that pneumonitis in patients with lung cancer tended to resemble chronic obstructive pneumonia, whereas patients with melanoma were more likely to have ground-glass opacifications on radiography. There was a trend, falling just short of significance, toward association of COP-like pneumonitis with development of grade 3 or greater, and with a requirement for more than one type of immunosuppression, compared to other subtypes.

Algorithms for management

Dr. Gettinger briefly outlined an algorithm offered by Bristol-Myers Squibb for management of suspected pulmonary toxicity with nivolumab. For management of patients with grade 1 toxicities (asymptomatic, with radiographic changes only), it recommends that clinicians consider delay of immuno-oncologic (I-O) therapy, monitor for symptoms every 2-3 days, and consider consultations with pulmonary and infectious disease specialists.

For grade 2 pneumonitis, marked by mild to moderate new symptoms, the algorithm calls for clinicians to delay I-O therapy per protocol, consult with pulmonary and ID specialists, monitor symptoms daily and consider hospitalization, start the patient on steroids with 1.0 mg/kg per day methylprednisolone IV or the oral equivalent, and consider bronchoscopy and lung biopsy.

For patients with grade 3 or 4 toxicities, marked by severe new symptoms, new or worsening hypoxia, or other life-threatening symptoms, the algorithm states that clinicians should discontinue I-O therapy, hospitalize the patient, consult with pulmonary and ID, give 2-4 mg/kg per day methylprednisolone IV or the oral equivalent, add prophylactic antibiotics for opportunistic infections, and consider bronchoscopy and lung biopsy.

At Yale, Dr. Gettinger and colleagues, when presented with a symptomatic patient on a PD-axis inhibitor, will first rule out other etiologies such as infection, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, or cancer progression), typically with bronchoscopy.

For patients with moderate pneumonitis, they may treat with prednisone for 1 or 2 weeks, with a 4-6 week taper begun as symptoms start to resolve.

“In a patient who has profound hypoxia and shortness of breath, we may want to go higher: We might give them 2 mg/kg twice a day of [methylprednisolone] in the hospital, wait until they get better, and then slowly taper them, whether it be over 4 or 6 weeks or longer. Occasionally our patients need to get even higher doses of steroids and there’s really nothing to guide us. Who knows if 1 gram of [methylprednisolone] may be better than 60 g of prednisone? But we do it, and patients do get better with the higher doses,” he said.

In rare instances, patients may required other immunosuppressive agents, such as infliximab (Remicade), cyclophosphamide, or mycophenolate mofetil.

Patients who require additional immunosuppressive agents to resolve severe pneumonitis tend to have poor outcomes, Dr. Gettinger said.

Re-challenge of patients with a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor following resolution of pneumonitis appears to be inadvisable for all patients except possibly those with grade 1 (asymptomatic) toxicity, due to the high risk of recurrence, he said.

BOSTON – Treatment of pneumonitis associated with the PD-1 axis checkpoint inhibitors requires close monitoring of patients and rapid clinical response, an oncologist advised.

“We need to be vigilant when we treat our patients. If a patient has cough or shortness of breath, you take it seriously, even if [it is] a patient who has lung cancer and is a smoker,” said Dr. Scott Gettinger of Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn.

He recommended that before starting patients on a programmed death-1 (PD-1) axis inhibitor such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or nivolumab (Opdivo), clinicians get baseline oxygen saturation levels to obtain an objective measure for following patients during therapy.

“When you suspect pneumonitis you have to start steroids right away, or patients can spiral down,” he said at the AACR/NCI/EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics.

Pneumonitis – characterized by cough, dyspnea, and hypoxia – is a common adverse event associated with PD-1 and PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, but is rarely seen in patients treated with CTLA-4 inhibitors such as ipilimumab (Yervoy). Current evidence suggests that pneumonitis is more prevalent in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, occurring in approximately 4%-6% of patients cases, than in melanoma (1%). The difference is probably due to a history of smoking common to the majority of patients with NSCLC, Dr. Gettinger said.

“The other theme that we’re beginning to see is that maybe pneumonitis is a bit more common with anti-PD-1 vs. anti-PD-L1 antibodies,” he said.

It’s theorized that PD-1 inhibitors may block binding of PD-L2 to one of its binding partners, thereby interfering with respiratory tolerance, he said.

Evidence from the pivotal clinical trial of nivolumab in lung cancer (Checkmate 057) suggests that the time to onset of pneumonitis was a median of 31.1 weeks (range 11.7 to 56.9 weeks). The pneumonitis resolved in about 5-7 weeks.

Investigators at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City reported at the European Cancer Congress 2015 on pneumonitis in 36 of 653 patients treated with an anti PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibody from 2009 through 2014, 33 of whom had received a PD-1 inhibitor, and 3 of whom received a PD-L1 inhibitor.

They found that pneumonitis in patients with lung cancer tended to resemble chronic obstructive pneumonia, whereas patients with melanoma were more likely to have ground-glass opacifications on radiography. There was a trend, falling just short of significance, toward association of COP-like pneumonitis with development of grade 3 or greater, and with a requirement for more than one type of immunosuppression, compared to other subtypes.

Algorithms for management

Dr. Gettinger briefly outlined an algorithm offered by Bristol-Myers Squibb for management of suspected pulmonary toxicity with nivolumab. For management of patients with grade 1 toxicities (asymptomatic, with radiographic changes only), it recommends that clinicians consider delay of immuno-oncologic (I-O) therapy, monitor for symptoms every 2-3 days, and consider consultations with pulmonary and infectious disease specialists.

For grade 2 pneumonitis, marked by mild to moderate new symptoms, the algorithm calls for clinicians to delay I-O therapy per protocol, consult with pulmonary and ID specialists, monitor symptoms daily and consider hospitalization, start the patient on steroids with 1.0 mg/kg per day methylprednisolone IV or the oral equivalent, and consider bronchoscopy and lung biopsy.

For patients with grade 3 or 4 toxicities, marked by severe new symptoms, new or worsening hypoxia, or other life-threatening symptoms, the algorithm states that clinicians should discontinue I-O therapy, hospitalize the patient, consult with pulmonary and ID, give 2-4 mg/kg per day methylprednisolone IV or the oral equivalent, add prophylactic antibiotics for opportunistic infections, and consider bronchoscopy and lung biopsy.

At Yale, Dr. Gettinger and colleagues, when presented with a symptomatic patient on a PD-axis inhibitor, will first rule out other etiologies such as infection, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, or cancer progression), typically with bronchoscopy.

For patients with moderate pneumonitis, they may treat with prednisone for 1 or 2 weeks, with a 4-6 week taper begun as symptoms start to resolve.

“In a patient who has profound hypoxia and shortness of breath, we may want to go higher: We might give them 2 mg/kg twice a day of [methylprednisolone] in the hospital, wait until they get better, and then slowly taper them, whether it be over 4 or 6 weeks or longer. Occasionally our patients need to get even higher doses of steroids and there’s really nothing to guide us. Who knows if 1 gram of [methylprednisolone] may be better than 60 g of prednisone? But we do it, and patients do get better with the higher doses,” he said.

In rare instances, patients may required other immunosuppressive agents, such as infliximab (Remicade), cyclophosphamide, or mycophenolate mofetil.

Patients who require additional immunosuppressive agents to resolve severe pneumonitis tend to have poor outcomes, Dr. Gettinger said.

Re-challenge of patients with a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor following resolution of pneumonitis appears to be inadvisable for all patients except possibly those with grade 1 (asymptomatic) toxicity, due to the high risk of recurrence, he said.

BOSTON – Treatment of pneumonitis associated with the PD-1 axis checkpoint inhibitors requires close monitoring of patients and rapid clinical response, an oncologist advised.

“We need to be vigilant when we treat our patients. If a patient has cough or shortness of breath, you take it seriously, even if [it is] a patient who has lung cancer and is a smoker,” said Dr. Scott Gettinger of Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn.

He recommended that before starting patients on a programmed death-1 (PD-1) axis inhibitor such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or nivolumab (Opdivo), clinicians get baseline oxygen saturation levels to obtain an objective measure for following patients during therapy.

“When you suspect pneumonitis you have to start steroids right away, or patients can spiral down,” he said at the AACR/NCI/EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics.

Pneumonitis – characterized by cough, dyspnea, and hypoxia – is a common adverse event associated with PD-1 and PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, but is rarely seen in patients treated with CTLA-4 inhibitors such as ipilimumab (Yervoy). Current evidence suggests that pneumonitis is more prevalent in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, occurring in approximately 4%-6% of patients cases, than in melanoma (1%). The difference is probably due to a history of smoking common to the majority of patients with NSCLC, Dr. Gettinger said.

“The other theme that we’re beginning to see is that maybe pneumonitis is a bit more common with anti-PD-1 vs. anti-PD-L1 antibodies,” he said.

It’s theorized that PD-1 inhibitors may block binding of PD-L2 to one of its binding partners, thereby interfering with respiratory tolerance, he said.

Evidence from the pivotal clinical trial of nivolumab in lung cancer (Checkmate 057) suggests that the time to onset of pneumonitis was a median of 31.1 weeks (range 11.7 to 56.9 weeks). The pneumonitis resolved in about 5-7 weeks.

Investigators at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City reported at the European Cancer Congress 2015 on pneumonitis in 36 of 653 patients treated with an anti PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal antibody from 2009 through 2014, 33 of whom had received a PD-1 inhibitor, and 3 of whom received a PD-L1 inhibitor.

They found that pneumonitis in patients with lung cancer tended to resemble chronic obstructive pneumonia, whereas patients with melanoma were more likely to have ground-glass opacifications on radiography. There was a trend, falling just short of significance, toward association of COP-like pneumonitis with development of grade 3 or greater, and with a requirement for more than one type of immunosuppression, compared to other subtypes.

Algorithms for management

Dr. Gettinger briefly outlined an algorithm offered by Bristol-Myers Squibb for management of suspected pulmonary toxicity with nivolumab. For management of patients with grade 1 toxicities (asymptomatic, with radiographic changes only), it recommends that clinicians consider delay of immuno-oncologic (I-O) therapy, monitor for symptoms every 2-3 days, and consider consultations with pulmonary and infectious disease specialists.

For grade 2 pneumonitis, marked by mild to moderate new symptoms, the algorithm calls for clinicians to delay I-O therapy per protocol, consult with pulmonary and ID specialists, monitor symptoms daily and consider hospitalization, start the patient on steroids with 1.0 mg/kg per day methylprednisolone IV or the oral equivalent, and consider bronchoscopy and lung biopsy.

For patients with grade 3 or 4 toxicities, marked by severe new symptoms, new or worsening hypoxia, or other life-threatening symptoms, the algorithm states that clinicians should discontinue I-O therapy, hospitalize the patient, consult with pulmonary and ID, give 2-4 mg/kg per day methylprednisolone IV or the oral equivalent, add prophylactic antibiotics for opportunistic infections, and consider bronchoscopy and lung biopsy.

At Yale, Dr. Gettinger and colleagues, when presented with a symptomatic patient on a PD-axis inhibitor, will first rule out other etiologies such as infection, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, or cancer progression), typically with bronchoscopy.

For patients with moderate pneumonitis, they may treat with prednisone for 1 or 2 weeks, with a 4-6 week taper begun as symptoms start to resolve.