User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

SDEF: Have higher degree of suspicion for pediatric allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is often missed in pediatric patients who present with eczema-like skin eruptions, in part because less is known about ACD in children than in adults.

“Often when we see a child with dermatitis, we automatically think of atopic dermatitis, but we should also consider the possibility of allergic contact dermatitis,” Dr. Joseph F. Fowler Jr. said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

A 2012 cohort study of 349 children between 0 and 15 years indicated that even very young children who were patch tested for common allergens had at least one positive result. Investigators found that nearly three-quarters of children studied tested positive for at least one allergen, typically nickel, other metals, fragrance, or preservatives (Dermatitis. 2012 Nov-Dec;23[6]:275-80).

“This is very similar to what we see in the adult population,” said Dr. Fowler, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Louisville (Ky.). “Other studies in recent years have borne this out.”

Dr. Fowler suggested having a high degree of suspicion for ACD, especially when pediatric patients present with:

• Chronic, difficult to control atopic condition, as this could indicate a systemic reaction.

• Localized or facial dermatitis, as this could indicate the point of contact with an allergen.

• Scattered, generalized dermatitis, which also could represent systemic allergic contact dermatitis.

• Dermatitis that worsens, despite otherwise adequate treatment regimen.

• Reactions following contact with metals, fragrances, topical components, such as preservatives or neomycin.

“In these situations, patch testing will help determine that an allergen is implicated,” Dr. Fowler said.

In children with eczema, Dr. Fowler recommended patch testing when the eczema is not in the typical areas such as behind the knees or elbows, or if it started in typical areas and then spread elsewhere, especially in children around 5 years old.

“The moral of the story is that kids can be allergic to the same things as adults, even though we have less about this in the literature,” Dr. Fowler. “Skin testing or blood testing for food allergies, unless very strongly positive, usually aren’t helpful in the management of the atopic individual. Patch test more and prick test less.”

Dr. Fowler disclosed a number of relationships with companies in the dermatology space. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Allergic contact dermatitis is often missed in pediatric patients who present with eczema-like skin eruptions, in part because less is known about ACD in children than in adults.

“Often when we see a child with dermatitis, we automatically think of atopic dermatitis, but we should also consider the possibility of allergic contact dermatitis,” Dr. Joseph F. Fowler Jr. said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

A 2012 cohort study of 349 children between 0 and 15 years indicated that even very young children who were patch tested for common allergens had at least one positive result. Investigators found that nearly three-quarters of children studied tested positive for at least one allergen, typically nickel, other metals, fragrance, or preservatives (Dermatitis. 2012 Nov-Dec;23[6]:275-80).

“This is very similar to what we see in the adult population,” said Dr. Fowler, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Louisville (Ky.). “Other studies in recent years have borne this out.”

Dr. Fowler suggested having a high degree of suspicion for ACD, especially when pediatric patients present with:

• Chronic, difficult to control atopic condition, as this could indicate a systemic reaction.

• Localized or facial dermatitis, as this could indicate the point of contact with an allergen.

• Scattered, generalized dermatitis, which also could represent systemic allergic contact dermatitis.

• Dermatitis that worsens, despite otherwise adequate treatment regimen.

• Reactions following contact with metals, fragrances, topical components, such as preservatives or neomycin.

“In these situations, patch testing will help determine that an allergen is implicated,” Dr. Fowler said.

In children with eczema, Dr. Fowler recommended patch testing when the eczema is not in the typical areas such as behind the knees or elbows, or if it started in typical areas and then spread elsewhere, especially in children around 5 years old.

“The moral of the story is that kids can be allergic to the same things as adults, even though we have less about this in the literature,” Dr. Fowler. “Skin testing or blood testing for food allergies, unless very strongly positive, usually aren’t helpful in the management of the atopic individual. Patch test more and prick test less.”

Dr. Fowler disclosed a number of relationships with companies in the dermatology space. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Allergic contact dermatitis is often missed in pediatric patients who present with eczema-like skin eruptions, in part because less is known about ACD in children than in adults.

“Often when we see a child with dermatitis, we automatically think of atopic dermatitis, but we should also consider the possibility of allergic contact dermatitis,” Dr. Joseph F. Fowler Jr. said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

A 2012 cohort study of 349 children between 0 and 15 years indicated that even very young children who were patch tested for common allergens had at least one positive result. Investigators found that nearly three-quarters of children studied tested positive for at least one allergen, typically nickel, other metals, fragrance, or preservatives (Dermatitis. 2012 Nov-Dec;23[6]:275-80).

“This is very similar to what we see in the adult population,” said Dr. Fowler, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Louisville (Ky.). “Other studies in recent years have borne this out.”

Dr. Fowler suggested having a high degree of suspicion for ACD, especially when pediatric patients present with:

• Chronic, difficult to control atopic condition, as this could indicate a systemic reaction.

• Localized or facial dermatitis, as this could indicate the point of contact with an allergen.

• Scattered, generalized dermatitis, which also could represent systemic allergic contact dermatitis.

• Dermatitis that worsens, despite otherwise adequate treatment regimen.

• Reactions following contact with metals, fragrances, topical components, such as preservatives or neomycin.

“In these situations, patch testing will help determine that an allergen is implicated,” Dr. Fowler said.

In children with eczema, Dr. Fowler recommended patch testing when the eczema is not in the typical areas such as behind the knees or elbows, or if it started in typical areas and then spread elsewhere, especially in children around 5 years old.

“The moral of the story is that kids can be allergic to the same things as adults, even though we have less about this in the literature,” Dr. Fowler. “Skin testing or blood testing for food allergies, unless very strongly positive, usually aren’t helpful in the management of the atopic individual. Patch test more and prick test less.”

Dr. Fowler disclosed a number of relationships with companies in the dermatology space. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Influenza linked to atrial fibrillation in large observational study

A diagnosis of influenza increased the risk of subsequent atrial fibrillation by about 18%, investigators reported online in Heart Rhythm.

Clinicians therefore should consider atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with influenza-like symptoms who report palpitations or experience an ischemic stroke, said Dr. Ting-Yung Chang of Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan and his associates. Influenza vaccination might help prevent AF, and high-risk patients should be encouraged to receive the vaccination annually, they said. However, a large prospective study is needed to clarify whether influenza vaccination reduces the risk of AF and subsequent ischemic stroke and systemic thromboembolic events, they added.

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of stroke about fivefold, triples the risk of heart failure, and doubles the chances of dementia and death, the researchers noted. Mounting evidence implicates inflammation and sympathetic nervous system dysregulation in the pathogenesis of AF, raising questions about whether influenza might underlie or contribute to some cases of AF. To explore relationships among AF, influenza, and influenza vaccination, the investigators analyzed data for 11,374 patients with AF who were enrolled in the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database between 2000 and 2010. They matched each patient with AF to four controls based on age, sex, enrollment date, and the Charlson comorbidity index (

Heart Rhythm. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.01.026

).

Unvaccinated patients with influenza were 18% more likely to develop AF than unvaccinated patients without influenza (odds ratio, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.38; P = .032), even after adjusting for demographic factors, medical history, and use of relevant health care services, the researchers reported. In contrast, vaccinated patients who later developed influenza were about as likely to develop AF as unvaccinated patients who did not develop influenza, both in the overall analysis and in subgroups stratified by age, sex, and comorbidities. Moreover, vaccinated patients without influenza were even less likely to develop AF than unvaccinated patients without influenza (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.84-0.93; P less than .001).

The registry database excluded relevant data on smoking history, body mass index, and physical activity level, the researchers said. “Influenza infection was diagnosed using ICD-9 codes with concomitant use of antiviral agents, and was not further confirmed based on the results of viral culture with throat swab,” they added. “The diagnostic accuracy of influenza infection cannot be fully ascertained.”

The National Science Council and the Taipei Veterans General Hospital funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

The authors readily acknowledge the limitations of [this] large, observational study using an insurance database. Despite these admitted limitations, the authors should be commended on adding to the literature regarding modifiable risk factor reduction for the prevention of AF. Recently, a growing body of literature has examined this topic with several straightforward yet promising interventions identified. Weight loss, moderate exercise, and treatment for underlying obstructive sleep apnea have all been shown to reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation incidence or recurrence. Influenza vaccination could represent another simple, cost‐effective intervention to prevent AF. Although the flu vaccine is already recommended for many patient groups, this study suggests that there are even more potential public health benefits of the vaccine.

Dr. Bradley P. Knight is with the division of cardiology, department of medicine, at Northwestern University, Chicago. He had no disclosures. These comments were adapted from his editorial (Heart Rhythm. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.01.025).

The authors readily acknowledge the limitations of [this] large, observational study using an insurance database. Despite these admitted limitations, the authors should be commended on adding to the literature regarding modifiable risk factor reduction for the prevention of AF. Recently, a growing body of literature has examined this topic with several straightforward yet promising interventions identified. Weight loss, moderate exercise, and treatment for underlying obstructive sleep apnea have all been shown to reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation incidence or recurrence. Influenza vaccination could represent another simple, cost‐effective intervention to prevent AF. Although the flu vaccine is already recommended for many patient groups, this study suggests that there are even more potential public health benefits of the vaccine.

Dr. Bradley P. Knight is with the division of cardiology, department of medicine, at Northwestern University, Chicago. He had no disclosures. These comments were adapted from his editorial (Heart Rhythm. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.01.025).

The authors readily acknowledge the limitations of [this] large, observational study using an insurance database. Despite these admitted limitations, the authors should be commended on adding to the literature regarding modifiable risk factor reduction for the prevention of AF. Recently, a growing body of literature has examined this topic with several straightforward yet promising interventions identified. Weight loss, moderate exercise, and treatment for underlying obstructive sleep apnea have all been shown to reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation incidence or recurrence. Influenza vaccination could represent another simple, cost‐effective intervention to prevent AF. Although the flu vaccine is already recommended for many patient groups, this study suggests that there are even more potential public health benefits of the vaccine.

Dr. Bradley P. Knight is with the division of cardiology, department of medicine, at Northwestern University, Chicago. He had no disclosures. These comments were adapted from his editorial (Heart Rhythm. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.01.025).

A diagnosis of influenza increased the risk of subsequent atrial fibrillation by about 18%, investigators reported online in Heart Rhythm.

Clinicians therefore should consider atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with influenza-like symptoms who report palpitations or experience an ischemic stroke, said Dr. Ting-Yung Chang of Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan and his associates. Influenza vaccination might help prevent AF, and high-risk patients should be encouraged to receive the vaccination annually, they said. However, a large prospective study is needed to clarify whether influenza vaccination reduces the risk of AF and subsequent ischemic stroke and systemic thromboembolic events, they added.

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of stroke about fivefold, triples the risk of heart failure, and doubles the chances of dementia and death, the researchers noted. Mounting evidence implicates inflammation and sympathetic nervous system dysregulation in the pathogenesis of AF, raising questions about whether influenza might underlie or contribute to some cases of AF. To explore relationships among AF, influenza, and influenza vaccination, the investigators analyzed data for 11,374 patients with AF who were enrolled in the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database between 2000 and 2010. They matched each patient with AF to four controls based on age, sex, enrollment date, and the Charlson comorbidity index (

Heart Rhythm. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.01.026

).

Unvaccinated patients with influenza were 18% more likely to develop AF than unvaccinated patients without influenza (odds ratio, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.38; P = .032), even after adjusting for demographic factors, medical history, and use of relevant health care services, the researchers reported. In contrast, vaccinated patients who later developed influenza were about as likely to develop AF as unvaccinated patients who did not develop influenza, both in the overall analysis and in subgroups stratified by age, sex, and comorbidities. Moreover, vaccinated patients without influenza were even less likely to develop AF than unvaccinated patients without influenza (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.84-0.93; P less than .001).

The registry database excluded relevant data on smoking history, body mass index, and physical activity level, the researchers said. “Influenza infection was diagnosed using ICD-9 codes with concomitant use of antiviral agents, and was not further confirmed based on the results of viral culture with throat swab,” they added. “The diagnostic accuracy of influenza infection cannot be fully ascertained.”

The National Science Council and the Taipei Veterans General Hospital funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

A diagnosis of influenza increased the risk of subsequent atrial fibrillation by about 18%, investigators reported online in Heart Rhythm.

Clinicians therefore should consider atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with influenza-like symptoms who report palpitations or experience an ischemic stroke, said Dr. Ting-Yung Chang of Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan and his associates. Influenza vaccination might help prevent AF, and high-risk patients should be encouraged to receive the vaccination annually, they said. However, a large prospective study is needed to clarify whether influenza vaccination reduces the risk of AF and subsequent ischemic stroke and systemic thromboembolic events, they added.

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of stroke about fivefold, triples the risk of heart failure, and doubles the chances of dementia and death, the researchers noted. Mounting evidence implicates inflammation and sympathetic nervous system dysregulation in the pathogenesis of AF, raising questions about whether influenza might underlie or contribute to some cases of AF. To explore relationships among AF, influenza, and influenza vaccination, the investigators analyzed data for 11,374 patients with AF who were enrolled in the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database between 2000 and 2010. They matched each patient with AF to four controls based on age, sex, enrollment date, and the Charlson comorbidity index (

Heart Rhythm. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.01.026

).

Unvaccinated patients with influenza were 18% more likely to develop AF than unvaccinated patients without influenza (odds ratio, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.38; P = .032), even after adjusting for demographic factors, medical history, and use of relevant health care services, the researchers reported. In contrast, vaccinated patients who later developed influenza were about as likely to develop AF as unvaccinated patients who did not develop influenza, both in the overall analysis and in subgroups stratified by age, sex, and comorbidities. Moreover, vaccinated patients without influenza were even less likely to develop AF than unvaccinated patients without influenza (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.84-0.93; P less than .001).

The registry database excluded relevant data on smoking history, body mass index, and physical activity level, the researchers said. “Influenza infection was diagnosed using ICD-9 codes with concomitant use of antiviral agents, and was not further confirmed based on the results of viral culture with throat swab,” they added. “The diagnostic accuracy of influenza infection cannot be fully ascertained.”

The National Science Council and the Taipei Veterans General Hospital funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

Key clinical point: Influenza might underlie some cases of atrial fibrillation.

Major finding: Among unvaccinated patients, an influenza diagnosis increased the odds of atrial fibrillation by 18% (OR, 1.18; P = .03).

Data source: An observational registry study of 11,374 patients with atrial fibrillation and 45,496 healthy controls.

Disclosures: The National Science Council and the Taipei Veterans General Hospital funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

COPD Exacerbation Amps Up Stroke Risk

People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have an approximately 20% increased risk of stroke, and the risk is highest during the time after an acute exacerbation of COPD, data from a large epidemiologic study indicate.

The study also indicated that cigarette smoking was a strong risk factor for stroke and that hypertension management is important in COPD patients given the elevated risk for hemorrhagic strokes observed, according to Dr. Marileen L. P. Portegies of Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues.

In 13,115 participants from the Rotterdam study, people with COPD had a 6.7-fold increase in the risk of stroke within the first 7 weeks of a severe exacerbation (hazard ratio, 6.66; 95% confidence interval, 2.42-18.20).

The study (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 193:251-8) found that 1,250 of the participants had a stroke (701 were ischemic and 107 hemorrhagic) over 126,347 person-years of follow-up.

After researchers adjusted for age and sex, COPD was significantly associated with all stroke (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.00-1.43), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.02-1.59), and hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.01-2.84).

Smoking was the strongest explanatory factor for the association between COPD and stroke, the researchers said. Adjustments for cardiovascular risk factors gave similar effect sizes, whereas adjustments for smoking attenuated the effect sizes: for all stroke, (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.91-1.31); for ischemic stroke, (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91-1.42) ; and for hemorrhagic stroke, (HR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.91-2.59) .

“Our study reveals the importance of smoking as a shared risk factor and implicates that clinicians should be aware of the higher risk of both stroke subtypes in subjects with COPD, especially after severe exacerbations,” they concluded.

Writing in an accompanying editorial Dr. Janice M. Leung and Dr. Don D. Sin from St. Paul’s Hospital University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said there was no doubt that cardiovascular disease, stroke, and COPD all shared smoking as a common risk factor.

But smoking alone failed to account for the particularly critical period of a COPD exacerbation during which the risk for strokes and myocardial infarctions exponentially increase.

“Surely, this acute period must offer clues as to why such a strong link exists among the lung, heart, and brain in COPD,” the researchers wrote.

COPD exacerbations may represent a time of intense oxidative stress and systemic inflammation that drive endothelial dysfunction, vascular reactivity, and even atherosclerotic plaque rupture.

“Pulmonologists must work closer with cardiologists and neurologists to enable optimal vascular care for patients with COPD, because it is clear that the lungs do not stand alone and that COPD, although a lung disease, is a major risk factor for stroke, especially during exacerbations,” they concluded.

People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have an approximately 20% increased risk of stroke, and the risk is highest during the time after an acute exacerbation of COPD, data from a large epidemiologic study indicate.

The study also indicated that cigarette smoking was a strong risk factor for stroke and that hypertension management is important in COPD patients given the elevated risk for hemorrhagic strokes observed, according to Dr. Marileen L. P. Portegies of Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues.

In 13,115 participants from the Rotterdam study, people with COPD had a 6.7-fold increase in the risk of stroke within the first 7 weeks of a severe exacerbation (hazard ratio, 6.66; 95% confidence interval, 2.42-18.20).

The study (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 193:251-8) found that 1,250 of the participants had a stroke (701 were ischemic and 107 hemorrhagic) over 126,347 person-years of follow-up.

After researchers adjusted for age and sex, COPD was significantly associated with all stroke (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.00-1.43), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.02-1.59), and hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.01-2.84).

Smoking was the strongest explanatory factor for the association between COPD and stroke, the researchers said. Adjustments for cardiovascular risk factors gave similar effect sizes, whereas adjustments for smoking attenuated the effect sizes: for all stroke, (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.91-1.31); for ischemic stroke, (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91-1.42) ; and for hemorrhagic stroke, (HR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.91-2.59) .

“Our study reveals the importance of smoking as a shared risk factor and implicates that clinicians should be aware of the higher risk of both stroke subtypes in subjects with COPD, especially after severe exacerbations,” they concluded.

Writing in an accompanying editorial Dr. Janice M. Leung and Dr. Don D. Sin from St. Paul’s Hospital University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said there was no doubt that cardiovascular disease, stroke, and COPD all shared smoking as a common risk factor.

But smoking alone failed to account for the particularly critical period of a COPD exacerbation during which the risk for strokes and myocardial infarctions exponentially increase.

“Surely, this acute period must offer clues as to why such a strong link exists among the lung, heart, and brain in COPD,” the researchers wrote.

COPD exacerbations may represent a time of intense oxidative stress and systemic inflammation that drive endothelial dysfunction, vascular reactivity, and even atherosclerotic plaque rupture.

“Pulmonologists must work closer with cardiologists and neurologists to enable optimal vascular care for patients with COPD, because it is clear that the lungs do not stand alone and that COPD, although a lung disease, is a major risk factor for stroke, especially during exacerbations,” they concluded.

People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have an approximately 20% increased risk of stroke, and the risk is highest during the time after an acute exacerbation of COPD, data from a large epidemiologic study indicate.

The study also indicated that cigarette smoking was a strong risk factor for stroke and that hypertension management is important in COPD patients given the elevated risk for hemorrhagic strokes observed, according to Dr. Marileen L. P. Portegies of Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues.

In 13,115 participants from the Rotterdam study, people with COPD had a 6.7-fold increase in the risk of stroke within the first 7 weeks of a severe exacerbation (hazard ratio, 6.66; 95% confidence interval, 2.42-18.20).

The study (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 193:251-8) found that 1,250 of the participants had a stroke (701 were ischemic and 107 hemorrhagic) over 126,347 person-years of follow-up.

After researchers adjusted for age and sex, COPD was significantly associated with all stroke (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.00-1.43), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.02-1.59), and hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.01-2.84).

Smoking was the strongest explanatory factor for the association between COPD and stroke, the researchers said. Adjustments for cardiovascular risk factors gave similar effect sizes, whereas adjustments for smoking attenuated the effect sizes: for all stroke, (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.91-1.31); for ischemic stroke, (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91-1.42) ; and for hemorrhagic stroke, (HR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.91-2.59) .

“Our study reveals the importance of smoking as a shared risk factor and implicates that clinicians should be aware of the higher risk of both stroke subtypes in subjects with COPD, especially after severe exacerbations,” they concluded.

Writing in an accompanying editorial Dr. Janice M. Leung and Dr. Don D. Sin from St. Paul’s Hospital University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said there was no doubt that cardiovascular disease, stroke, and COPD all shared smoking as a common risk factor.

But smoking alone failed to account for the particularly critical period of a COPD exacerbation during which the risk for strokes and myocardial infarctions exponentially increase.

“Surely, this acute period must offer clues as to why such a strong link exists among the lung, heart, and brain in COPD,” the researchers wrote.

COPD exacerbations may represent a time of intense oxidative stress and systemic inflammation that drive endothelial dysfunction, vascular reactivity, and even atherosclerotic plaque rupture.

“Pulmonologists must work closer with cardiologists and neurologists to enable optimal vascular care for patients with COPD, because it is clear that the lungs do not stand alone and that COPD, although a lung disease, is a major risk factor for stroke, especially during exacerbations,” they concluded.

FROM AJRCCM

COPD exacerbation amps up stroke risk

People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have an approximately 20% increased risk of stroke, and the risk is highest during the time after an acute exacerbation of COPD, data from a large epidemiologic study indicate.

The study also indicated that cigarette smoking was a strong risk factor for stroke and that hypertension management is important in COPD patients given the elevated risk for hemorrhagic strokes observed, according to Dr. Marileen L. P. Portegies of Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues.

In 13,115 participants from the Rotterdam study, people with COPD had a 6.7-fold increase in the risk of stroke within the first 7 weeks of a severe exacerbation (hazard ratio, 6.66; 95% confidence interval, 2.42-18.20).

The study (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 193:251-8) found that 1,250 of the participants had a stroke (701 were ischemic and 107 hemorrhagic) over 126,347 person-years of follow-up.

After researchers adjusted for age and sex, COPD was significantly associated with all stroke (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.00-1.43), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.02-1.59), and hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.01-2.84).

Smoking was the strongest explanatory factor for the association between COPD and stroke, the researchers said. Adjustments for cardiovascular risk factors gave similar effect sizes, whereas adjustments for smoking attenuated the effect sizes: for all stroke, (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.91-1.31); for ischemic stroke, (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91-1.42) ; and for hemorrhagic stroke, (HR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.91-2.59) .

“Our study reveals the importance of smoking as a shared risk factor and implicates that clinicians should be aware of the higher risk of both stroke subtypes in subjects with COPD, especially after severe exacerbations,” they concluded.

Writing in an accompanying editorial Dr. Janice M. Leung and Dr. Don D. Sin from St. Paul’s Hospital University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said there was no doubt that cardiovascular disease, stroke, and COPD all shared smoking as a common risk factor.

But smoking alone failed to account for the particularly critical period of a COPD exacerbation during which the risk for strokes and myocardial infarctions exponentially increase.

“Surely, this acute period must offer clues as to why such a strong link exists among the lung, heart, and brain in COPD,” the researchers wrote.

COPD exacerbations may represent a time of intense oxidative stress and systemic inflammation that drive endothelial dysfunction, vascular reactivity, and even atherosclerotic plaque rupture.

“Pulmonologists must work closer with cardiologists and neurologists to enable optimal vascular care for patients with COPD, because it is clear that the lungs do not stand alone and that COPD, although a lung disease, is a major risk factor for stroke, especially during exacerbations,” they concluded.

People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have an approximately 20% increased risk of stroke, and the risk is highest during the time after an acute exacerbation of COPD, data from a large epidemiologic study indicate.

The study also indicated that cigarette smoking was a strong risk factor for stroke and that hypertension management is important in COPD patients given the elevated risk for hemorrhagic strokes observed, according to Dr. Marileen L. P. Portegies of Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues.

In 13,115 participants from the Rotterdam study, people with COPD had a 6.7-fold increase in the risk of stroke within the first 7 weeks of a severe exacerbation (hazard ratio, 6.66; 95% confidence interval, 2.42-18.20).

The study (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 193:251-8) found that 1,250 of the participants had a stroke (701 were ischemic and 107 hemorrhagic) over 126,347 person-years of follow-up.

After researchers adjusted for age and sex, COPD was significantly associated with all stroke (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.00-1.43), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.02-1.59), and hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.01-2.84).

Smoking was the strongest explanatory factor for the association between COPD and stroke, the researchers said. Adjustments for cardiovascular risk factors gave similar effect sizes, whereas adjustments for smoking attenuated the effect sizes: for all stroke, (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.91-1.31); for ischemic stroke, (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91-1.42) ; and for hemorrhagic stroke, (HR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.91-2.59) .

“Our study reveals the importance of smoking as a shared risk factor and implicates that clinicians should be aware of the higher risk of both stroke subtypes in subjects with COPD, especially after severe exacerbations,” they concluded.

Writing in an accompanying editorial Dr. Janice M. Leung and Dr. Don D. Sin from St. Paul’s Hospital University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said there was no doubt that cardiovascular disease, stroke, and COPD all shared smoking as a common risk factor.

But smoking alone failed to account for the particularly critical period of a COPD exacerbation during which the risk for strokes and myocardial infarctions exponentially increase.

“Surely, this acute period must offer clues as to why such a strong link exists among the lung, heart, and brain in COPD,” the researchers wrote.

COPD exacerbations may represent a time of intense oxidative stress and systemic inflammation that drive endothelial dysfunction, vascular reactivity, and even atherosclerotic plaque rupture.

“Pulmonologists must work closer with cardiologists and neurologists to enable optimal vascular care for patients with COPD, because it is clear that the lungs do not stand alone and that COPD, although a lung disease, is a major risk factor for stroke, especially during exacerbations,” they concluded.

People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have an approximately 20% increased risk of stroke, and the risk is highest during the time after an acute exacerbation of COPD, data from a large epidemiologic study indicate.

The study also indicated that cigarette smoking was a strong risk factor for stroke and that hypertension management is important in COPD patients given the elevated risk for hemorrhagic strokes observed, according to Dr. Marileen L. P. Portegies of Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues.

In 13,115 participants from the Rotterdam study, people with COPD had a 6.7-fold increase in the risk of stroke within the first 7 weeks of a severe exacerbation (hazard ratio, 6.66; 95% confidence interval, 2.42-18.20).

The study (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 193:251-8) found that 1,250 of the participants had a stroke (701 were ischemic and 107 hemorrhagic) over 126,347 person-years of follow-up.

After researchers adjusted for age and sex, COPD was significantly associated with all stroke (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.00-1.43), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.02-1.59), and hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.01-2.84).

Smoking was the strongest explanatory factor for the association between COPD and stroke, the researchers said. Adjustments for cardiovascular risk factors gave similar effect sizes, whereas adjustments for smoking attenuated the effect sizes: for all stroke, (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.91-1.31); for ischemic stroke, (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91-1.42) ; and for hemorrhagic stroke, (HR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.91-2.59) .

“Our study reveals the importance of smoking as a shared risk factor and implicates that clinicians should be aware of the higher risk of both stroke subtypes in subjects with COPD, especially after severe exacerbations,” they concluded.

Writing in an accompanying editorial Dr. Janice M. Leung and Dr. Don D. Sin from St. Paul’s Hospital University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said there was no doubt that cardiovascular disease, stroke, and COPD all shared smoking as a common risk factor.

But smoking alone failed to account for the particularly critical period of a COPD exacerbation during which the risk for strokes and myocardial infarctions exponentially increase.

“Surely, this acute period must offer clues as to why such a strong link exists among the lung, heart, and brain in COPD,” the researchers wrote.

COPD exacerbations may represent a time of intense oxidative stress and systemic inflammation that drive endothelial dysfunction, vascular reactivity, and even atherosclerotic plaque rupture.

“Pulmonologists must work closer with cardiologists and neurologists to enable optimal vascular care for patients with COPD, because it is clear that the lungs do not stand alone and that COPD, although a lung disease, is a major risk factor for stroke, especially during exacerbations,” they concluded.

FROM AJRCCM

Key clinical point: Risk for stroke is 6.7-fold higher in the 7 weeks after an acute exacerbation of COPD.

Major finding: People with COPD had a 6.7-fold increase in the risk of stroke within the first 7 weeks of a severe exacerbation.

Data source: A prospective population-based Rotterdam study involving 13,115 participants of without a history or occurrence of stroke.

Disclosures: The Rotterdam Study is supported by the Erasmus MC University Medical Center and Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Human gene editing consensus study underway

A consensus study of the scientific underpinnings of human gene editing technologies is underway, and the committee of experts behind the effort will independently review potential applications for those technologies, as well as the clinical, ethical, legal, and social implications of their use.

The multidisciplinary committee met Feb. 11 to receive input from select stakeholders as it launches its review, the results of which will represent the official views of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine.

Among those stakeholders were representatives from several companies commercializing gene editing, a representative from the National Institutes of Health, and patient advocacy groups.

With some caveats, participants lobbied to maintain the existing regulatory framework related to gene therapy.

Michael Werner, cofounder and executive director of the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, which advocates globally for regenerative medicine and advanced therapies, said his organization believes “the existing regulatory framework overall works for these technologies.”

“We don’t believe the [Food and Drug Administration], for example, needs to create a whole separate oversight process in addition to the process we already have now for gene therapy,” he said, adding that “the ultimate goal here is not to have regulatory action or legislative action that will hinder or delay the development of these technologies.”

The consensus study follows an International Summit on Human Gene Editing held in December, and is the next component of the Human Gene Editing Initiative. The committee will study the potential for gene editing in biomedical research and medicine – including human germline editing – although representatives from each of the companies represented at the meeting noted that they are not currently focused on germline applications.

Rather, the commercial focus is on other areas, such as correcting genes in somatic cells.

“We start with medical need. We want to work on things where there is not currently a therapy that addresses adequately the medical need, and we need the ability to generate a differentiated product,” said Vic Myer, Ph.D., of Editas Medicine in Cambridge, Mass.

The company has projects underway for opthalmologic applications, sickle cell anemia, beta-thalassemia, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in the liver, and others.

“We are working on a number of different types of edits in a number of different tissues with a number of delivery modalities,” Dr. Myer said, noting that some programs will move quickly, while others will not.

Similarly, Intellia Therapeutics, also of Cambridge, Mass., is “focusing very much on what we hope will be curative products for somatic gene-based disorders,” said Dr. John Leonard, the company’s chief medical officer.

“We limit our work to somatic cells. We thought very carefully about that and that is what we do,” he added, noting that a recently launched division of Intellia is focused on autoimmune oncology opportunities (ex vivo), and on liver disease (in vivo).

The committee of experts conducting the consensus study, which began its information-gathering process in December at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing, will take these and other views expressed at the meeting into consideration during its work over the next year. The study will include a literature review and data gathering via meetings in the United States and abroad. The committee will continue to seek input from researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and the public.

“The committee will also monitor in real time the latest scientific achievements of importance in this rapidly developing field,” according to information from the National Academies.

The field has enormous potential, according to Mr. Werner, who explained that combined, the various types of gene editing technology available are “pretty powerful” in terms of an approach for targeting and changing DNA sequences in human cells.

“We’re talking about the potential to durably treat and potentially even cure diseases that currently represent unmet medical needs,” he said. “We could, in theory, be talking about millions of patients worldwide.”

A consensus study of the scientific underpinnings of human gene editing technologies is underway, and the committee of experts behind the effort will independently review potential applications for those technologies, as well as the clinical, ethical, legal, and social implications of their use.

The multidisciplinary committee met Feb. 11 to receive input from select stakeholders as it launches its review, the results of which will represent the official views of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine.

Among those stakeholders were representatives from several companies commercializing gene editing, a representative from the National Institutes of Health, and patient advocacy groups.

With some caveats, participants lobbied to maintain the existing regulatory framework related to gene therapy.

Michael Werner, cofounder and executive director of the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, which advocates globally for regenerative medicine and advanced therapies, said his organization believes “the existing regulatory framework overall works for these technologies.”

“We don’t believe the [Food and Drug Administration], for example, needs to create a whole separate oversight process in addition to the process we already have now for gene therapy,” he said, adding that “the ultimate goal here is not to have regulatory action or legislative action that will hinder or delay the development of these technologies.”

The consensus study follows an International Summit on Human Gene Editing held in December, and is the next component of the Human Gene Editing Initiative. The committee will study the potential for gene editing in biomedical research and medicine – including human germline editing – although representatives from each of the companies represented at the meeting noted that they are not currently focused on germline applications.

Rather, the commercial focus is on other areas, such as correcting genes in somatic cells.

“We start with medical need. We want to work on things where there is not currently a therapy that addresses adequately the medical need, and we need the ability to generate a differentiated product,” said Vic Myer, Ph.D., of Editas Medicine in Cambridge, Mass.

The company has projects underway for opthalmologic applications, sickle cell anemia, beta-thalassemia, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in the liver, and others.

“We are working on a number of different types of edits in a number of different tissues with a number of delivery modalities,” Dr. Myer said, noting that some programs will move quickly, while others will not.

Similarly, Intellia Therapeutics, also of Cambridge, Mass., is “focusing very much on what we hope will be curative products for somatic gene-based disorders,” said Dr. John Leonard, the company’s chief medical officer.

“We limit our work to somatic cells. We thought very carefully about that and that is what we do,” he added, noting that a recently launched division of Intellia is focused on autoimmune oncology opportunities (ex vivo), and on liver disease (in vivo).

The committee of experts conducting the consensus study, which began its information-gathering process in December at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing, will take these and other views expressed at the meeting into consideration during its work over the next year. The study will include a literature review and data gathering via meetings in the United States and abroad. The committee will continue to seek input from researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and the public.

“The committee will also monitor in real time the latest scientific achievements of importance in this rapidly developing field,” according to information from the National Academies.

The field has enormous potential, according to Mr. Werner, who explained that combined, the various types of gene editing technology available are “pretty powerful” in terms of an approach for targeting and changing DNA sequences in human cells.

“We’re talking about the potential to durably treat and potentially even cure diseases that currently represent unmet medical needs,” he said. “We could, in theory, be talking about millions of patients worldwide.”

A consensus study of the scientific underpinnings of human gene editing technologies is underway, and the committee of experts behind the effort will independently review potential applications for those technologies, as well as the clinical, ethical, legal, and social implications of their use.

The multidisciplinary committee met Feb. 11 to receive input from select stakeholders as it launches its review, the results of which will represent the official views of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine.

Among those stakeholders were representatives from several companies commercializing gene editing, a representative from the National Institutes of Health, and patient advocacy groups.

With some caveats, participants lobbied to maintain the existing regulatory framework related to gene therapy.

Michael Werner, cofounder and executive director of the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, which advocates globally for regenerative medicine and advanced therapies, said his organization believes “the existing regulatory framework overall works for these technologies.”

“We don’t believe the [Food and Drug Administration], for example, needs to create a whole separate oversight process in addition to the process we already have now for gene therapy,” he said, adding that “the ultimate goal here is not to have regulatory action or legislative action that will hinder or delay the development of these technologies.”

The consensus study follows an International Summit on Human Gene Editing held in December, and is the next component of the Human Gene Editing Initiative. The committee will study the potential for gene editing in biomedical research and medicine – including human germline editing – although representatives from each of the companies represented at the meeting noted that they are not currently focused on germline applications.

Rather, the commercial focus is on other areas, such as correcting genes in somatic cells.

“We start with medical need. We want to work on things where there is not currently a therapy that addresses adequately the medical need, and we need the ability to generate a differentiated product,” said Vic Myer, Ph.D., of Editas Medicine in Cambridge, Mass.

The company has projects underway for opthalmologic applications, sickle cell anemia, beta-thalassemia, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in the liver, and others.

“We are working on a number of different types of edits in a number of different tissues with a number of delivery modalities,” Dr. Myer said, noting that some programs will move quickly, while others will not.

Similarly, Intellia Therapeutics, also of Cambridge, Mass., is “focusing very much on what we hope will be curative products for somatic gene-based disorders,” said Dr. John Leonard, the company’s chief medical officer.

“We limit our work to somatic cells. We thought very carefully about that and that is what we do,” he added, noting that a recently launched division of Intellia is focused on autoimmune oncology opportunities (ex vivo), and on liver disease (in vivo).

The committee of experts conducting the consensus study, which began its information-gathering process in December at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing, will take these and other views expressed at the meeting into consideration during its work over the next year. The study will include a literature review and data gathering via meetings in the United States and abroad. The committee will continue to seek input from researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and the public.

“The committee will also monitor in real time the latest scientific achievements of importance in this rapidly developing field,” according to information from the National Academies.

The field has enormous potential, according to Mr. Werner, who explained that combined, the various types of gene editing technology available are “pretty powerful” in terms of an approach for targeting and changing DNA sequences in human cells.

“We’re talking about the potential to durably treat and potentially even cure diseases that currently represent unmet medical needs,” he said. “We could, in theory, be talking about millions of patients worldwide.”

Recent Active Asthma Raises AAA Rupture Risk

Patients aged 50 and older with recent active asthma are at elevated risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm and aneurysm rupture, according to new research.

A common inflammatory pathway between asthma and AAA, first observed nearly a decade ago in mice, is thought to be responsible.

The new findings, published online Feb. 11 in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306497) support the association in humans.

In a news release accompanying the findings, lead study author Guo-Ping Shi, D.Sc., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that the findings had clear clinical implications for older patients with a recent asthma diagnosis. Such patients, particularly older men, “should be checked for signs” of abdominal aortic aneurysm, Dr. Shi said.

For their research, Dr. Shi, along with colleagues at Zhengzhou (China) University, used data from a large Danish population-based cohort of nearly 16,000 patients (81% men) with AAA between 1996 and 2012, of which about 4,500 patients had rupture. They also looked at data from a comparison cohort of patients with and without AAA from a slightly larger population-based vascular screening trial of men in Denmark.

The investigators showed that hospital diagnosis of asthma within the previous year (n = 514) was associated with significantly higher risk of hospital admission with AAA rupture (n = 146) both before and after adjustment for AAA comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio 1.51-2.06). Higher risk of rupture also was seen for patients filling prescriptions for bronchodilators within the previous 3 months (aOR = 1.10-1.31), and for patients prescribed anti-asthma drugs (aOR OR = 1.09-1.48), which were seen as indicative of an outpatient asthma diagnosis.

“A hospital diagnosis of asthma or a recently filled prescription of an anti-asthmatic drug is associated with an increased risk of admission with rAAA compared with admission with intact AAA, both before and after adjusting for AAA comorbidities and relevant medications,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Moreover, “an asthma diagnosis or the use of bronchodilators or other anti-asthmatic drug prescriptions closer to the date of admission with AAA correlated directly with a higher risk of aortic rupture. The results remained robust after adjusting for a wide range of relevant possible confounders,” the researchers wrote.

In the cohort of patients from the vascular screening study, which included age-matched controls without AAA, asthma (measured by recent anti-asthmatic medication use) was seen associated with a significantly elevated risk of AAA before (OR = 1.45) and after adjustment for smoking (OR = 1.45) or other risk factors (OR = 1.46). This does not refer to rupture but just AAA.

Dr. Shi and colleagues noted that the AAA cohort lacked sufficient information on cigarette smoking, a known risk factor for AAA and AAA rupture, to preclude the possibility of confounding; however, the second all-male cohort did have extensive data on smoking, “and the risk of AAA among patients with asthma remained 45% higher than that of patients with nonasthma” even after adjustment.

The researchers hypothesized that an inflammatory response characterized by elevated immunoglobulin E may be the link between AAA pathogenesis and asthma, and that other allergic inflammatory diseases, including atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and some ocular allergic diseases, could potentially carry risks for AAA formation and rupture. Dr. Shi and colleagues previously investigated the IgE and aneurysm link in animal studies.

“The results have implications for the development of much needed advances in the prevention, screening criteria, and treatment of AAA, common conditions for which we currently lack sufficiently effective approaches,” the investigators wrote.

The Chinese, Danish, and U.S. governments sponsored the study. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Patients aged 50 and older with recent active asthma are at elevated risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm and aneurysm rupture, according to new research.

A common inflammatory pathway between asthma and AAA, first observed nearly a decade ago in mice, is thought to be responsible.

The new findings, published online Feb. 11 in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306497) support the association in humans.

In a news release accompanying the findings, lead study author Guo-Ping Shi, D.Sc., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that the findings had clear clinical implications for older patients with a recent asthma diagnosis. Such patients, particularly older men, “should be checked for signs” of abdominal aortic aneurysm, Dr. Shi said.

For their research, Dr. Shi, along with colleagues at Zhengzhou (China) University, used data from a large Danish population-based cohort of nearly 16,000 patients (81% men) with AAA between 1996 and 2012, of which about 4,500 patients had rupture. They also looked at data from a comparison cohort of patients with and without AAA from a slightly larger population-based vascular screening trial of men in Denmark.

The investigators showed that hospital diagnosis of asthma within the previous year (n = 514) was associated with significantly higher risk of hospital admission with AAA rupture (n = 146) both before and after adjustment for AAA comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio 1.51-2.06). Higher risk of rupture also was seen for patients filling prescriptions for bronchodilators within the previous 3 months (aOR = 1.10-1.31), and for patients prescribed anti-asthma drugs (aOR OR = 1.09-1.48), which were seen as indicative of an outpatient asthma diagnosis.

“A hospital diagnosis of asthma or a recently filled prescription of an anti-asthmatic drug is associated with an increased risk of admission with rAAA compared with admission with intact AAA, both before and after adjusting for AAA comorbidities and relevant medications,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Moreover, “an asthma diagnosis or the use of bronchodilators or other anti-asthmatic drug prescriptions closer to the date of admission with AAA correlated directly with a higher risk of aortic rupture. The results remained robust after adjusting for a wide range of relevant possible confounders,” the researchers wrote.

In the cohort of patients from the vascular screening study, which included age-matched controls without AAA, asthma (measured by recent anti-asthmatic medication use) was seen associated with a significantly elevated risk of AAA before (OR = 1.45) and after adjustment for smoking (OR = 1.45) or other risk factors (OR = 1.46). This does not refer to rupture but just AAA.

Dr. Shi and colleagues noted that the AAA cohort lacked sufficient information on cigarette smoking, a known risk factor for AAA and AAA rupture, to preclude the possibility of confounding; however, the second all-male cohort did have extensive data on smoking, “and the risk of AAA among patients with asthma remained 45% higher than that of patients with nonasthma” even after adjustment.

The researchers hypothesized that an inflammatory response characterized by elevated immunoglobulin E may be the link between AAA pathogenesis and asthma, and that other allergic inflammatory diseases, including atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and some ocular allergic diseases, could potentially carry risks for AAA formation and rupture. Dr. Shi and colleagues previously investigated the IgE and aneurysm link in animal studies.

“The results have implications for the development of much needed advances in the prevention, screening criteria, and treatment of AAA, common conditions for which we currently lack sufficiently effective approaches,” the investigators wrote.

The Chinese, Danish, and U.S. governments sponsored the study. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Patients aged 50 and older with recent active asthma are at elevated risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm and aneurysm rupture, according to new research.

A common inflammatory pathway between asthma and AAA, first observed nearly a decade ago in mice, is thought to be responsible.

The new findings, published online Feb. 11 in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306497) support the association in humans.

In a news release accompanying the findings, lead study author Guo-Ping Shi, D.Sc., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that the findings had clear clinical implications for older patients with a recent asthma diagnosis. Such patients, particularly older men, “should be checked for signs” of abdominal aortic aneurysm, Dr. Shi said.

For their research, Dr. Shi, along with colleagues at Zhengzhou (China) University, used data from a large Danish population-based cohort of nearly 16,000 patients (81% men) with AAA between 1996 and 2012, of which about 4,500 patients had rupture. They also looked at data from a comparison cohort of patients with and without AAA from a slightly larger population-based vascular screening trial of men in Denmark.

The investigators showed that hospital diagnosis of asthma within the previous year (n = 514) was associated with significantly higher risk of hospital admission with AAA rupture (n = 146) both before and after adjustment for AAA comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio 1.51-2.06). Higher risk of rupture also was seen for patients filling prescriptions for bronchodilators within the previous 3 months (aOR = 1.10-1.31), and for patients prescribed anti-asthma drugs (aOR OR = 1.09-1.48), which were seen as indicative of an outpatient asthma diagnosis.

“A hospital diagnosis of asthma or a recently filled prescription of an anti-asthmatic drug is associated with an increased risk of admission with rAAA compared with admission with intact AAA, both before and after adjusting for AAA comorbidities and relevant medications,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Moreover, “an asthma diagnosis or the use of bronchodilators or other anti-asthmatic drug prescriptions closer to the date of admission with AAA correlated directly with a higher risk of aortic rupture. The results remained robust after adjusting for a wide range of relevant possible confounders,” the researchers wrote.

In the cohort of patients from the vascular screening study, which included age-matched controls without AAA, asthma (measured by recent anti-asthmatic medication use) was seen associated with a significantly elevated risk of AAA before (OR = 1.45) and after adjustment for smoking (OR = 1.45) or other risk factors (OR = 1.46). This does not refer to rupture but just AAA.

Dr. Shi and colleagues noted that the AAA cohort lacked sufficient information on cigarette smoking, a known risk factor for AAA and AAA rupture, to preclude the possibility of confounding; however, the second all-male cohort did have extensive data on smoking, “and the risk of AAA among patients with asthma remained 45% higher than that of patients with nonasthma” even after adjustment.

The researchers hypothesized that an inflammatory response characterized by elevated immunoglobulin E may be the link between AAA pathogenesis and asthma, and that other allergic inflammatory diseases, including atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and some ocular allergic diseases, could potentially carry risks for AAA formation and rupture. Dr. Shi and colleagues previously investigated the IgE and aneurysm link in animal studies.

“The results have implications for the development of much needed advances in the prevention, screening criteria, and treatment of AAA, common conditions for which we currently lack sufficiently effective approaches,” the investigators wrote.

The Chinese, Danish, and U.S. governments sponsored the study. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM ARTERIOSCLEROSIS, THROMBOSIS, AND VASCULAR BIOLOGY

Recent active asthma raises AAA rupture risk

Patients aged 50 and older with recent active asthma are at elevated risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm and aneurysm rupture, according to new research.

A common inflammatory pathway between asthma and AAA, first observed nearly a decade ago in mice, is thought to be responsible.

The new findings, published online Feb. 11 in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306497) support the association in humans.

In a news release accompanying the findings, lead study author Guo-Ping Shi, ScD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that the findings had clear clinical implications for older patients with a recent asthma diagnosis. Such patients, particularly older men, “should be checked for signs” of abdominal aortic aneurysm, Dr. Shi said.*

For their research, Dr. Shi, along with colleagues at Zhengzhou (China) University, used data from a large Danish population-based cohort of nearly 16,000 patients (81% men) with AAA between 1996 and 2012, of which about 4,500 patients had rupture. They also looked at data from a comparison cohort of patients with and without AAA from a slightly larger population-based vascular screening trial of men in Denmark.

The investigators showed that hospital diagnosis of asthma within the previous year (n = 514) was associated with significantly higher risk of hospital admission with AAA rupture (n = 146) both before and after adjustment for AAA comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio 1.51-2.06). Higher risk of rupture also was seen for patients filling prescriptions for bronchodilators within the previous 3 months (aOR = 1.10-1.31), and for patients prescribed anti-asthma drugs (aOR OR = 1.09-1.48), which were seen as indicative of an outpatient asthma diagnosis.

“A hospital diagnosis of asthma or a recently filled prescription of an anti-asthmatic drug is associated with an increased risk of admission with rAAA compared with admission with intact AAA, both before and after adjusting for AAA comorbidities and relevant medications,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Moreover, “an asthma diagnosis or the use of bronchodilators or other anti-asthmatic drug prescriptions closer to the date of admission with AAA correlated directly with a higher risk of aortic rupture. The results remained robust after adjusting for a wide range of relevant possible confounders,” the researchers wrote.

In the cohort of patients from the vascular screening study, which included age-matched controls without AAA, asthma (measured by recent anti-asthmatic medication use) was seen associated with a significantly elevated risk of AAA before (OR = 1.45) and after adjustment for smoking (OR = 1.45) or other risk factors (OR = 1.46). This does not refer to rupture but just AAA.

Dr. Shi and colleagues noted that the AAA cohort lacked sufficient information on cigarette smoking, a known risk factor for AAA and AAA rupture, to preclude the possibility of confounding; however, the second all-male cohort did have extensive data on smoking, “and the risk of AAA among patients with asthma remained 45% higher than that of patients with nonasthma” even after adjustment.

The researchers hypothesized that an inflammatory response characterized by elevated immunoglobulin E may be the link between AAA pathogenesis and asthma, and that other allergic inflammatory diseases, including atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and some ocular allergic diseases, could potentially carry risks for AAA formation and rupture. Dr. Shi and colleagues previously investigated the IgE and aneurysm link in animal studies.

“The results have implications for the development of much needed advances in the prevention, screening criteria, and treatment of AAA, common conditions for which we currently lack sufficiently effective approaches,” the investigators wrote.

The Chinese, Danish, and U.S. governments sponsored the study. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

*CORRECTION 8/12/2020: Dr. Shi's credential was misstated in the original version on this article and has been corrected to ScD.

Patients aged 50 and older with recent active asthma are at elevated risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm and aneurysm rupture, according to new research.

A common inflammatory pathway between asthma and AAA, first observed nearly a decade ago in mice, is thought to be responsible.

The new findings, published online Feb. 11 in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306497) support the association in humans.

In a news release accompanying the findings, lead study author Guo-Ping Shi, ScD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that the findings had clear clinical implications for older patients with a recent asthma diagnosis. Such patients, particularly older men, “should be checked for signs” of abdominal aortic aneurysm, Dr. Shi said.*

For their research, Dr. Shi, along with colleagues at Zhengzhou (China) University, used data from a large Danish population-based cohort of nearly 16,000 patients (81% men) with AAA between 1996 and 2012, of which about 4,500 patients had rupture. They also looked at data from a comparison cohort of patients with and without AAA from a slightly larger population-based vascular screening trial of men in Denmark.

The investigators showed that hospital diagnosis of asthma within the previous year (n = 514) was associated with significantly higher risk of hospital admission with AAA rupture (n = 146) both before and after adjustment for AAA comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio 1.51-2.06). Higher risk of rupture also was seen for patients filling prescriptions for bronchodilators within the previous 3 months (aOR = 1.10-1.31), and for patients prescribed anti-asthma drugs (aOR OR = 1.09-1.48), which were seen as indicative of an outpatient asthma diagnosis.

“A hospital diagnosis of asthma or a recently filled prescription of an anti-asthmatic drug is associated with an increased risk of admission with rAAA compared with admission with intact AAA, both before and after adjusting for AAA comorbidities and relevant medications,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Moreover, “an asthma diagnosis or the use of bronchodilators or other anti-asthmatic drug prescriptions closer to the date of admission with AAA correlated directly with a higher risk of aortic rupture. The results remained robust after adjusting for a wide range of relevant possible confounders,” the researchers wrote.

In the cohort of patients from the vascular screening study, which included age-matched controls without AAA, asthma (measured by recent anti-asthmatic medication use) was seen associated with a significantly elevated risk of AAA before (OR = 1.45) and after adjustment for smoking (OR = 1.45) or other risk factors (OR = 1.46). This does not refer to rupture but just AAA.

Dr. Shi and colleagues noted that the AAA cohort lacked sufficient information on cigarette smoking, a known risk factor for AAA and AAA rupture, to preclude the possibility of confounding; however, the second all-male cohort did have extensive data on smoking, “and the risk of AAA among patients with asthma remained 45% higher than that of patients with nonasthma” even after adjustment.

The researchers hypothesized that an inflammatory response characterized by elevated immunoglobulin E may be the link between AAA pathogenesis and asthma, and that other allergic inflammatory diseases, including atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and some ocular allergic diseases, could potentially carry risks for AAA formation and rupture. Dr. Shi and colleagues previously investigated the IgE and aneurysm link in animal studies.

“The results have implications for the development of much needed advances in the prevention, screening criteria, and treatment of AAA, common conditions for which we currently lack sufficiently effective approaches,” the investigators wrote.

The Chinese, Danish, and U.S. governments sponsored the study. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

*CORRECTION 8/12/2020: Dr. Shi's credential was misstated in the original version on this article and has been corrected to ScD.

Patients aged 50 and older with recent active asthma are at elevated risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm and aneurysm rupture, according to new research.

A common inflammatory pathway between asthma and AAA, first observed nearly a decade ago in mice, is thought to be responsible.

The new findings, published online Feb. 11 in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306497) support the association in humans.

In a news release accompanying the findings, lead study author Guo-Ping Shi, ScD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that the findings had clear clinical implications for older patients with a recent asthma diagnosis. Such patients, particularly older men, “should be checked for signs” of abdominal aortic aneurysm, Dr. Shi said.*

For their research, Dr. Shi, along with colleagues at Zhengzhou (China) University, used data from a large Danish population-based cohort of nearly 16,000 patients (81% men) with AAA between 1996 and 2012, of which about 4,500 patients had rupture. They also looked at data from a comparison cohort of patients with and without AAA from a slightly larger population-based vascular screening trial of men in Denmark.

The investigators showed that hospital diagnosis of asthma within the previous year (n = 514) was associated with significantly higher risk of hospital admission with AAA rupture (n = 146) both before and after adjustment for AAA comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio 1.51-2.06). Higher risk of rupture also was seen for patients filling prescriptions for bronchodilators within the previous 3 months (aOR = 1.10-1.31), and for patients prescribed anti-asthma drugs (aOR OR = 1.09-1.48), which were seen as indicative of an outpatient asthma diagnosis.

“A hospital diagnosis of asthma or a recently filled prescription of an anti-asthmatic drug is associated with an increased risk of admission with rAAA compared with admission with intact AAA, both before and after adjusting for AAA comorbidities and relevant medications,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

Moreover, “an asthma diagnosis or the use of bronchodilators or other anti-asthmatic drug prescriptions closer to the date of admission with AAA correlated directly with a higher risk of aortic rupture. The results remained robust after adjusting for a wide range of relevant possible confounders,” the researchers wrote.

In the cohort of patients from the vascular screening study, which included age-matched controls without AAA, asthma (measured by recent anti-asthmatic medication use) was seen associated with a significantly elevated risk of AAA before (OR = 1.45) and after adjustment for smoking (OR = 1.45) or other risk factors (OR = 1.46). This does not refer to rupture but just AAA.

Dr. Shi and colleagues noted that the AAA cohort lacked sufficient information on cigarette smoking, a known risk factor for AAA and AAA rupture, to preclude the possibility of confounding; however, the second all-male cohort did have extensive data on smoking, “and the risk of AAA among patients with asthma remained 45% higher than that of patients with nonasthma” even after adjustment.

The researchers hypothesized that an inflammatory response characterized by elevated immunoglobulin E may be the link between AAA pathogenesis and asthma, and that other allergic inflammatory diseases, including atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and some ocular allergic diseases, could potentially carry risks for AAA formation and rupture. Dr. Shi and colleagues previously investigated the IgE and aneurysm link in animal studies.

“The results have implications for the development of much needed advances in the prevention, screening criteria, and treatment of AAA, common conditions for which we currently lack sufficiently effective approaches,” the investigators wrote.

The Chinese, Danish, and U.S. governments sponsored the study. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

*CORRECTION 8/12/2020: Dr. Shi's credential was misstated in the original version on this article and has been corrected to ScD.

FROM ARTERIOSCLEROSIS, THROMBOSIS, AND VASCULAR BIOLOGY

Key clinical point: Older patients with a recent asthma diagnosis, particularly men, should be checked for abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Major finding: People over 50 with recent active asthma and abdominal aortic aneurysm saw a more than 50% greater risk of rupture compared with patients without asthma.

Data source: Two large cohorts from Denmark of AAA patients 50 and older (n = 15,942) and men 65 and older with and without AAA (n = 18,749), with information on asthma diagnosis and rupture.

Disclosures: The Chinese, Danish, and U.S. governments sponsored the study. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

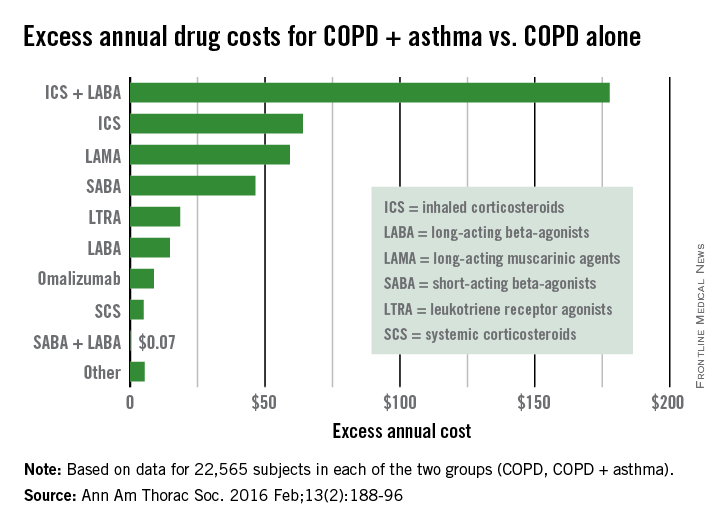

COPD + asthma more expensive than COPD alone

Health care costs almost $400 more per year for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who have a history of asthma, compared with those without asthma, according to a study using the health care and demographic records of over 45,000 adults in British Columbia.

From 1997 to 2012, the average annual health care cost for patients with COPD + asthma (n = 22,565) was $391 higher than for COPD patients who had no history of diagnosed asthma (n = 22,565), reported Dr. Mohsen Sadatsafavi of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his associates (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016 Feb;13[2]:188-96).

The largest component of that excess was medication costs, which were $476 higher for patients with COPD + asthma, with outpatient services ($92) and community care ($19) making smaller contributions. These excesses were somewhat offset by hospitalization costs, which were $196 less per year for the COPD + asthma group, the investigators said. (All costs in the study were given in Canadian dollars and have been converted here to U.S. dollars.)

Among the respiratory medications, the drug class with the largest difference was inhaled corticosteroids/long-acting beta-agonists, which cost almost $178 more per year for the COPD + asthma patients. Inhaled corticosteroids were next, with a cost excess of $64 annually, followed by long-acting muscarinic agents ($59), short-acting beta-agonists ($46) and leukotriene receptor agonists ($19), Dr. Sadatsafavi and his associates said.