User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

ACIP recommends LAIV as an option for all people with egg allergies

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) is likely to be an option for all individuals with egg allergies, regardless of allergy severity, because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to approve proposed amendments to the existing recommendations regarding administration of LAIV in individuals with egg allergies.

With 11 members voting “yes” and three choosing to abstain, the committee agreed to leave sections 1, 2, and 3 as they currently are, with a slight change to section 1 so that it will now include the latter half of recommendations that were previously placed under section 4. Therefore, section 1 of the recommendations for influenza vaccination of persons with egg allergy – which already states that “Regardless of a recipient’s allergy history, all vaccines should be administered in settings in which personnel and equipment for rapid recognition and treatment of anaphylaxis are available” – will now also include text stating that the vaccine should be administered in a medical setting and supervised by a health care provider with “experience in the recognition and management of severe allergic conditions,” or that such a medical professional should be “immediately available.”

Sections 2 and 3 will remain the same. Section 2 states that a previous allergic reaction to the influenza vaccine is a contraindication to ever receiving the vaccine again in the future. Section 3 states that individuals with egg allergy who have only experienced hives due to eggs still should be administered the influenza vaccine.

The committee voted to strike section 5 of the existing recommendations, which calls for a 30-minute postvaccination observation period. However, the committee still advises that health care providers monitor all patients, particularly adolescents, for 15 minutes immediately after vaccination, and that individuals should be seated or lying down “to decrease the risk for injury should syncopy occur.”

The CDC generally follows ACIP’s recommendations.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) is likely to be an option for all individuals with egg allergies, regardless of allergy severity, because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to approve proposed amendments to the existing recommendations regarding administration of LAIV in individuals with egg allergies.

With 11 members voting “yes” and three choosing to abstain, the committee agreed to leave sections 1, 2, and 3 as they currently are, with a slight change to section 1 so that it will now include the latter half of recommendations that were previously placed under section 4. Therefore, section 1 of the recommendations for influenza vaccination of persons with egg allergy – which already states that “Regardless of a recipient’s allergy history, all vaccines should be administered in settings in which personnel and equipment for rapid recognition and treatment of anaphylaxis are available” – will now also include text stating that the vaccine should be administered in a medical setting and supervised by a health care provider with “experience in the recognition and management of severe allergic conditions,” or that such a medical professional should be “immediately available.”

Sections 2 and 3 will remain the same. Section 2 states that a previous allergic reaction to the influenza vaccine is a contraindication to ever receiving the vaccine again in the future. Section 3 states that individuals with egg allergy who have only experienced hives due to eggs still should be administered the influenza vaccine.

The committee voted to strike section 5 of the existing recommendations, which calls for a 30-minute postvaccination observation period. However, the committee still advises that health care providers monitor all patients, particularly adolescents, for 15 minutes immediately after vaccination, and that individuals should be seated or lying down “to decrease the risk for injury should syncopy occur.”

The CDC generally follows ACIP’s recommendations.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) is likely to be an option for all individuals with egg allergies, regardless of allergy severity, because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to approve proposed amendments to the existing recommendations regarding administration of LAIV in individuals with egg allergies.

With 11 members voting “yes” and three choosing to abstain, the committee agreed to leave sections 1, 2, and 3 as they currently are, with a slight change to section 1 so that it will now include the latter half of recommendations that were previously placed under section 4. Therefore, section 1 of the recommendations for influenza vaccination of persons with egg allergy – which already states that “Regardless of a recipient’s allergy history, all vaccines should be administered in settings in which personnel and equipment for rapid recognition and treatment of anaphylaxis are available” – will now also include text stating that the vaccine should be administered in a medical setting and supervised by a health care provider with “experience in the recognition and management of severe allergic conditions,” or that such a medical professional should be “immediately available.”

Sections 2 and 3 will remain the same. Section 2 states that a previous allergic reaction to the influenza vaccine is a contraindication to ever receiving the vaccine again in the future. Section 3 states that individuals with egg allergy who have only experienced hives due to eggs still should be administered the influenza vaccine.

The committee voted to strike section 5 of the existing recommendations, which calls for a 30-minute postvaccination observation period. However, the committee still advises that health care providers monitor all patients, particularly adolescents, for 15 minutes immediately after vaccination, and that individuals should be seated or lying down “to decrease the risk for injury should syncopy occur.”

The CDC generally follows ACIP’s recommendations.

FROM AN ACIP MEETING

ACA accelerated hospital readmission reduction efforts

Hospital readmissions have declined in recent years for three conditions targeted under the Affordable Care Act, with smaller declines for other conditions, according to new research.

The study, published online Feb. 24 in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that 30-day readmission rates declined quickly after the passage of the ACA in 2010 and then slowed at the end of 2012. The researchers also analyzed trends in the use of observation units during the same period and concluded that the drop in readmissions was not being masked by a similar uptick in patients being seen under observation status (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024).

Under the ACA’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, hospitals are financially penalized if they have higher-than-expected readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia.

The researchers, led by Rachael B. Zuckerman, M.P.H., of the Department of Health & Human Services, examined Medicare data from 3,387 hospitals from October 2007 through May 2015. Overall readmissions for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia – the three conditions targeted in the readmissions reduction program – dropped from 21.5% to 17.8% during this time period. Readmissions for nontargeted conditions also dropped from 15.3% to 13.1%.

The researchers reported that readmissions for the targeted conditions were already declining before the ACA implementation (slope of monthly rate, –0.017), accelerating between April 2010 and October 2010 (–0.103), then leveling off through 2015 (–0.05). A similar pattern was seen with readmissions for conditions not targeted under the health law, though the declines were less pronounced.

Observation rates for the targeted conditions increased from 2.6% to 4.7% during the study period, while rates for nontargeted conditions rose from 2.5% to 4.2%. The researchers did not observe any significant associations increases in observation-unit stays – which were steady throughout the study period – and the implementation of the ACA.

“It seems likely that the upward trend in observation-service use may be attributable to factors that are largely unrelated to the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, such as confusion over whether an inpatient stay would be deemed inappropriate by Medicare recovery audit contractors,” the researchers wrote.

Though the observational design of the study could not confirm a causal link between the ACA penalties and the drop in readmissions, the findings suggest that the declines are not solely a response to the ACA.

The health law likely “catalyzed behavioral change by many hospitals” that was already underway, possibly because of broader concern about readmissions and to earlier Medicare initiatives designed to reduce them. Also, the investigators noted, hospitals may have been helped by other government efforts on the readmission front, including the dissemination of best practices by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The study was funded by HHS and the researchers were agency employees. They reported having no other financial disclosures.

Hospital readmissions have declined in recent years for three conditions targeted under the Affordable Care Act, with smaller declines for other conditions, according to new research.

The study, published online Feb. 24 in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that 30-day readmission rates declined quickly after the passage of the ACA in 2010 and then slowed at the end of 2012. The researchers also analyzed trends in the use of observation units during the same period and concluded that the drop in readmissions was not being masked by a similar uptick in patients being seen under observation status (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024).

Under the ACA’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, hospitals are financially penalized if they have higher-than-expected readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia.

The researchers, led by Rachael B. Zuckerman, M.P.H., of the Department of Health & Human Services, examined Medicare data from 3,387 hospitals from October 2007 through May 2015. Overall readmissions for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia – the three conditions targeted in the readmissions reduction program – dropped from 21.5% to 17.8% during this time period. Readmissions for nontargeted conditions also dropped from 15.3% to 13.1%.

The researchers reported that readmissions for the targeted conditions were already declining before the ACA implementation (slope of monthly rate, –0.017), accelerating between April 2010 and October 2010 (–0.103), then leveling off through 2015 (–0.05). A similar pattern was seen with readmissions for conditions not targeted under the health law, though the declines were less pronounced.

Observation rates for the targeted conditions increased from 2.6% to 4.7% during the study period, while rates for nontargeted conditions rose from 2.5% to 4.2%. The researchers did not observe any significant associations increases in observation-unit stays – which were steady throughout the study period – and the implementation of the ACA.

“It seems likely that the upward trend in observation-service use may be attributable to factors that are largely unrelated to the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, such as confusion over whether an inpatient stay would be deemed inappropriate by Medicare recovery audit contractors,” the researchers wrote.

Though the observational design of the study could not confirm a causal link between the ACA penalties and the drop in readmissions, the findings suggest that the declines are not solely a response to the ACA.

The health law likely “catalyzed behavioral change by many hospitals” that was already underway, possibly because of broader concern about readmissions and to earlier Medicare initiatives designed to reduce them. Also, the investigators noted, hospitals may have been helped by other government efforts on the readmission front, including the dissemination of best practices by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The study was funded by HHS and the researchers were agency employees. They reported having no other financial disclosures.

Hospital readmissions have declined in recent years for three conditions targeted under the Affordable Care Act, with smaller declines for other conditions, according to new research.

The study, published online Feb. 24 in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that 30-day readmission rates declined quickly after the passage of the ACA in 2010 and then slowed at the end of 2012. The researchers also analyzed trends in the use of observation units during the same period and concluded that the drop in readmissions was not being masked by a similar uptick in patients being seen under observation status (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024).

Under the ACA’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, hospitals are financially penalized if they have higher-than-expected readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia.

The researchers, led by Rachael B. Zuckerman, M.P.H., of the Department of Health & Human Services, examined Medicare data from 3,387 hospitals from October 2007 through May 2015. Overall readmissions for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia – the three conditions targeted in the readmissions reduction program – dropped from 21.5% to 17.8% during this time period. Readmissions for nontargeted conditions also dropped from 15.3% to 13.1%.

The researchers reported that readmissions for the targeted conditions were already declining before the ACA implementation (slope of monthly rate, –0.017), accelerating between April 2010 and October 2010 (–0.103), then leveling off through 2015 (–0.05). A similar pattern was seen with readmissions for conditions not targeted under the health law, though the declines were less pronounced.

Observation rates for the targeted conditions increased from 2.6% to 4.7% during the study period, while rates for nontargeted conditions rose from 2.5% to 4.2%. The researchers did not observe any significant associations increases in observation-unit stays – which were steady throughout the study period – and the implementation of the ACA.

“It seems likely that the upward trend in observation-service use may be attributable to factors that are largely unrelated to the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, such as confusion over whether an inpatient stay would be deemed inappropriate by Medicare recovery audit contractors,” the researchers wrote.

Though the observational design of the study could not confirm a causal link between the ACA penalties and the drop in readmissions, the findings suggest that the declines are not solely a response to the ACA.

The health law likely “catalyzed behavioral change by many hospitals” that was already underway, possibly because of broader concern about readmissions and to earlier Medicare initiatives designed to reduce them. Also, the investigators noted, hospitals may have been helped by other government efforts on the readmission front, including the dissemination of best practices by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The study was funded by HHS and the researchers were agency employees. They reported having no other financial disclosures.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Hospital readmission rates declined following ACA enactment in 2010, but increased use of observation units did not account for the change.

Major finding: During 2007-2015, 30-day hospital readmissions for three targeted conditions dropped from 21.5% to 17.8%.

Data source: An interrupted time-series analysis of readmission and observation unit stay data of elderly Medicare beneficiaries from nearly 3,400 hospitals from 2007-2015.

Disclosures: The Health and Human Services department funded the study and the researchers were agency employees. They reported having no other financial disclosures.

Chronic cough guidelines highlight research needs

Neuromodulatory therapies and speech pathology–based cough suppression are suggested treatment options for unexplained chronic cough in new guidelines from the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

The panel noted, however, that evidence supporting the diagnosis and management of unexplained chronic cough is limited. As part of the guideline development, they considered approaches for improving related research.

“Persistent cough of unexplained origin is a significant health issue that occurs in up to 5% to 10% of patients seeking medical assistance for a chronic cough and from 0% to 46% of patients referred to specialty cough clinics. Patients with unexplained chronic cough experience significant impairments in quality of life ... there is a need to identify effective treatment approaches,” Dr. Peter Gibson of Hunter Medical Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues reported on behalf of the panel (Chest. 2016;149[1]:27-44).

The panel defined unexplained chronic cough as a cough that persists longer than 8 weeks, and that remains unexplained after evaluations and supervised therapeutic trials are conducted according to guidelines.

The panel also suggested the following therapeutic approaches:

• That adult patients have objective testing for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilic bronchitis, or be offered a trial of corticosteroid therapy.

• That adult patients have a trial of multi-modality speech pathology therapy.

• That inhaled corticosteroids not be prescribed in adult patients who test negative for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilia.

• That a therapeutic trial of gabapentin be offered as long as the risk-benefit profile is discussed with the patient, and as long as reassessment of the risk-benefit profile be conducted at 6 months – before continuing the drug. The recommended starting dose is 300 mg daily in those without contraindications, with dose escalation daily as tolerated up to a maximum tolerable dose of 1,800 mg daily in two divided doses.

• That adult patients with a negative workup for acid gastroesophageal reflux disease not be prescribed a proton pump inhibitor.

The panel’s suggestions are the result of a systematic review of 11 randomized controlled trials and 5 systematic reviews to discern whether treatment is more efficacious than usual care with respect to cough severity, cough frequency, and cough-related quality of life.

Studies reviewed included data on 570 subjects over age 12 years with chronic cough who received a variety of interventions. Positive effects on cough-related quality of life were noted for both gabapentin and morphine, but the panel determined that only gabapentin was supported as a treatment recommendation.

After controlling for intervention fidelity bias, inhaled corticosteroids were not found to be effective for unexplained chronic cough, and esomeprazole was not effective in patients without features of gastroesophageal acid reflux.

Most of the recommendations are based on consensus opinion and limited data. As a result, the panel examined clinical trial design, chronic cough registries, and potential research questions in an effort to identify ways to improve research. Among other conclusions, the panel said future trials should include comparison groups as a significant placebo effect can occur in cough trials. Also, quality of life should be used as the primary study outcome.

“Registries for unexplained chronic cough could be used to document patient characteristics and outcomes, as well as clinical trials in progress. They could also serve as a source of research participants for trials and may allow for phenotyping according to age, sex, cough duration, cough severity, cough reflex sensitivity, and other biomarkers. Registries can be used for genetic studies in chronic cough.”

“Unexplained chronic cough requires further study to determine consistent terminology and the optimal methods of investigation using established criteria for intervention fidelity,” the panel concluded.

Dr. Gibson reported having no disclosures. One other author, Dr. Lorcan McGarvey, reported serving on advisory boards for Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline in relation to novel compounds with a potential role in treatment of cough, and serving as chairman for the Mortality Adjudication Committee for UPLIFT and TIOSPIR – two phase IV chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinical trials for Boehringer Ingelheim.

Neuromodulatory therapies and speech pathology–based cough suppression are suggested treatment options for unexplained chronic cough in new guidelines from the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

The panel noted, however, that evidence supporting the diagnosis and management of unexplained chronic cough is limited. As part of the guideline development, they considered approaches for improving related research.

“Persistent cough of unexplained origin is a significant health issue that occurs in up to 5% to 10% of patients seeking medical assistance for a chronic cough and from 0% to 46% of patients referred to specialty cough clinics. Patients with unexplained chronic cough experience significant impairments in quality of life ... there is a need to identify effective treatment approaches,” Dr. Peter Gibson of Hunter Medical Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues reported on behalf of the panel (Chest. 2016;149[1]:27-44).

The panel defined unexplained chronic cough as a cough that persists longer than 8 weeks, and that remains unexplained after evaluations and supervised therapeutic trials are conducted according to guidelines.

The panel also suggested the following therapeutic approaches:

• That adult patients have objective testing for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilic bronchitis, or be offered a trial of corticosteroid therapy.

• That adult patients have a trial of multi-modality speech pathology therapy.

• That inhaled corticosteroids not be prescribed in adult patients who test negative for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilia.

• That a therapeutic trial of gabapentin be offered as long as the risk-benefit profile is discussed with the patient, and as long as reassessment of the risk-benefit profile be conducted at 6 months – before continuing the drug. The recommended starting dose is 300 mg daily in those without contraindications, with dose escalation daily as tolerated up to a maximum tolerable dose of 1,800 mg daily in two divided doses.

• That adult patients with a negative workup for acid gastroesophageal reflux disease not be prescribed a proton pump inhibitor.

The panel’s suggestions are the result of a systematic review of 11 randomized controlled trials and 5 systematic reviews to discern whether treatment is more efficacious than usual care with respect to cough severity, cough frequency, and cough-related quality of life.

Studies reviewed included data on 570 subjects over age 12 years with chronic cough who received a variety of interventions. Positive effects on cough-related quality of life were noted for both gabapentin and morphine, but the panel determined that only gabapentin was supported as a treatment recommendation.

After controlling for intervention fidelity bias, inhaled corticosteroids were not found to be effective for unexplained chronic cough, and esomeprazole was not effective in patients without features of gastroesophageal acid reflux.

Most of the recommendations are based on consensus opinion and limited data. As a result, the panel examined clinical trial design, chronic cough registries, and potential research questions in an effort to identify ways to improve research. Among other conclusions, the panel said future trials should include comparison groups as a significant placebo effect can occur in cough trials. Also, quality of life should be used as the primary study outcome.

“Registries for unexplained chronic cough could be used to document patient characteristics and outcomes, as well as clinical trials in progress. They could also serve as a source of research participants for trials and may allow for phenotyping according to age, sex, cough duration, cough severity, cough reflex sensitivity, and other biomarkers. Registries can be used for genetic studies in chronic cough.”

“Unexplained chronic cough requires further study to determine consistent terminology and the optimal methods of investigation using established criteria for intervention fidelity,” the panel concluded.

Dr. Gibson reported having no disclosures. One other author, Dr. Lorcan McGarvey, reported serving on advisory boards for Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline in relation to novel compounds with a potential role in treatment of cough, and serving as chairman for the Mortality Adjudication Committee for UPLIFT and TIOSPIR – two phase IV chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinical trials for Boehringer Ingelheim.

Neuromodulatory therapies and speech pathology–based cough suppression are suggested treatment options for unexplained chronic cough in new guidelines from the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

The panel noted, however, that evidence supporting the diagnosis and management of unexplained chronic cough is limited. As part of the guideline development, they considered approaches for improving related research.

“Persistent cough of unexplained origin is a significant health issue that occurs in up to 5% to 10% of patients seeking medical assistance for a chronic cough and from 0% to 46% of patients referred to specialty cough clinics. Patients with unexplained chronic cough experience significant impairments in quality of life ... there is a need to identify effective treatment approaches,” Dr. Peter Gibson of Hunter Medical Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues reported on behalf of the panel (Chest. 2016;149[1]:27-44).

The panel defined unexplained chronic cough as a cough that persists longer than 8 weeks, and that remains unexplained after evaluations and supervised therapeutic trials are conducted according to guidelines.

The panel also suggested the following therapeutic approaches:

• That adult patients have objective testing for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilic bronchitis, or be offered a trial of corticosteroid therapy.

• That adult patients have a trial of multi-modality speech pathology therapy.

• That inhaled corticosteroids not be prescribed in adult patients who test negative for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilia.

• That a therapeutic trial of gabapentin be offered as long as the risk-benefit profile is discussed with the patient, and as long as reassessment of the risk-benefit profile be conducted at 6 months – before continuing the drug. The recommended starting dose is 300 mg daily in those without contraindications, with dose escalation daily as tolerated up to a maximum tolerable dose of 1,800 mg daily in two divided doses.

• That adult patients with a negative workup for acid gastroesophageal reflux disease not be prescribed a proton pump inhibitor.

The panel’s suggestions are the result of a systematic review of 11 randomized controlled trials and 5 systematic reviews to discern whether treatment is more efficacious than usual care with respect to cough severity, cough frequency, and cough-related quality of life.

Studies reviewed included data on 570 subjects over age 12 years with chronic cough who received a variety of interventions. Positive effects on cough-related quality of life were noted for both gabapentin and morphine, but the panel determined that only gabapentin was supported as a treatment recommendation.

After controlling for intervention fidelity bias, inhaled corticosteroids were not found to be effective for unexplained chronic cough, and esomeprazole was not effective in patients without features of gastroesophageal acid reflux.

Most of the recommendations are based on consensus opinion and limited data. As a result, the panel examined clinical trial design, chronic cough registries, and potential research questions in an effort to identify ways to improve research. Among other conclusions, the panel said future trials should include comparison groups as a significant placebo effect can occur in cough trials. Also, quality of life should be used as the primary study outcome.

“Registries for unexplained chronic cough could be used to document patient characteristics and outcomes, as well as clinical trials in progress. They could also serve as a source of research participants for trials and may allow for phenotyping according to age, sex, cough duration, cough severity, cough reflex sensitivity, and other biomarkers. Registries can be used for genetic studies in chronic cough.”

“Unexplained chronic cough requires further study to determine consistent terminology and the optimal methods of investigation using established criteria for intervention fidelity,” the panel concluded.

Dr. Gibson reported having no disclosures. One other author, Dr. Lorcan McGarvey, reported serving on advisory boards for Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline in relation to novel compounds with a potential role in treatment of cough, and serving as chairman for the Mortality Adjudication Committee for UPLIFT and TIOSPIR – two phase IV chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinical trials for Boehringer Ingelheim.

FROM CHEST

Vaccine coverage remains low in U.S. adults

Vaccine coverage of adults in the United States continues to be low for the seven vaccines currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, according to a study published in MMWR.

Illness attributable to vaccine-preventable diseases is more prevalent among adults than among children, and is especially high among the oldest adults.

For example, an estimated 50%-70% of influenza-related hospitalizations, 80%-90% of influenza-related deaths, and 50% of invasive pneumococcal disease each year occur in people aged 65 years and older, noted Dr. Walter W. Williams of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC, Atlanta, and his associates.

The influenza vaccine is recommended for all adults every year; the Td (pneumococcal, tetanus, diphtheria), Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis), hepatitis A, hepatitis B, herpes zoster, and HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccines are routinely recommended for many adults based on patient age, underlying medical conditions, lifestyle factors, occupation, travel, and other considerations.

However, adult vaccination coverage is low because of limited public awareness about the need for these vaccines, lack of vaccine requirements for adults like the immunization requirements in place for children, failure to incorporate routine vaccine assessments and recommendations in adult health care visits, the costs of stocking vaccines and providing vaccine services, inadequate or inconsistent payment for vaccines and for vaccine administration, and the tendency to prioritize acute over preventive medical care, they noted.

The investigators assessed nationwide vaccine coverage of adults using data from the 2013 and 2014 National Health Interview Survey, which annually collects health information from a large, nationally representative sample of households via in-person interviews. The 2014 sample included 36,324 adults who self-reported their vaccination status (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2016;65:1-36).

Coverage for Tdap slightly increased 2.9 percentage points to 20.1% of the eligible population in 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, and coverage for herpes zoster among high-risk patients aged 60 and older slightly increased 3.6 percentage points to 27.9% of the population. Coverage for the other five vaccines remained steady and low: for the influenza vaccine, 43.2% of the population; for the pneumococcal vaccine, 20.3% of high-risk younger adults and 61.3% of very high-risk older adults; for the Td vaccine, 62.2%; for hepatitis A, 9%; for hepatitis B, 24.5%; and for HPV, coverage was 8.2% for men and 40.2% for women aged 19-26 years.

As expected, vaccine coverage was lower for people who didn’t have health insurance, didn’t have a usual site for receiving health care, and didn’t have any physician contacts during the preceding year. However, even among adults who had health insurance and had 10 or more physician contacts within the past year, up to 88% reported that they hadn’t received vaccinations that were recommended for everyone or for specific populations.

Racial and ethnic gaps in vaccine coverage persisted for five of these vaccines and actually worsened for the Tdap and herpes zoster vaccines.

Advice from health care providers is strongly associated with delivery of adult vaccinations. To address these gaps in vaccine coverage, clinicians should consider routine assessment of all adult patients’ vaccine needs, use of a reminder/recall system, use of standing-order programs for vaccination, and assessment of their practices’ vaccination rates. “Efforts are also needed to identify adults who do not have a regular provider or insurance and who report fewer health care visits,” Dr. Williams and his associates said.

The CDC updates vaccine recommendations annually and publishes them in the U.S. Adult Immunization Schedule, which is “a ready resource for persons who provide healthcare services in various settings,” they added.

The CDC supported the study. The authors’ financial disclosures were not provided.

It is unfortunate that vaccination rates for preventable conditions continue to be stagnant at low levels. As stated in the article, there are a multitude of reasons proposed for this (and likely others - such as a very vocal anti-vaccination movement), and until prevention efforts are given the time and monetary attention similar to that of disease management, this trend will continue. A follow-up to this study would be informative to assess the effect of the Affordable Care Act's mandate to cover these preventive services.

Dr. Eric Gartman, FCCP, is a member of the editorial advisory board for CHEST Physician.

It is unfortunate that vaccination rates for preventable conditions continue to be stagnant at low levels. As stated in the article, there are a multitude of reasons proposed for this (and likely others - such as a very vocal anti-vaccination movement), and until prevention efforts are given the time and monetary attention similar to that of disease management, this trend will continue. A follow-up to this study would be informative to assess the effect of the Affordable Care Act's mandate to cover these preventive services.

Dr. Eric Gartman, FCCP, is a member of the editorial advisory board for CHEST Physician.

It is unfortunate that vaccination rates for preventable conditions continue to be stagnant at low levels. As stated in the article, there are a multitude of reasons proposed for this (and likely others - such as a very vocal anti-vaccination movement), and until prevention efforts are given the time and monetary attention similar to that of disease management, this trend will continue. A follow-up to this study would be informative to assess the effect of the Affordable Care Act's mandate to cover these preventive services.

Dr. Eric Gartman, FCCP, is a member of the editorial advisory board for CHEST Physician.

Vaccine coverage of adults in the United States continues to be low for the seven vaccines currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, according to a study published in MMWR.

Illness attributable to vaccine-preventable diseases is more prevalent among adults than among children, and is especially high among the oldest adults.

For example, an estimated 50%-70% of influenza-related hospitalizations, 80%-90% of influenza-related deaths, and 50% of invasive pneumococcal disease each year occur in people aged 65 years and older, noted Dr. Walter W. Williams of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC, Atlanta, and his associates.

The influenza vaccine is recommended for all adults every year; the Td (pneumococcal, tetanus, diphtheria), Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis), hepatitis A, hepatitis B, herpes zoster, and HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccines are routinely recommended for many adults based on patient age, underlying medical conditions, lifestyle factors, occupation, travel, and other considerations.

However, adult vaccination coverage is low because of limited public awareness about the need for these vaccines, lack of vaccine requirements for adults like the immunization requirements in place for children, failure to incorporate routine vaccine assessments and recommendations in adult health care visits, the costs of stocking vaccines and providing vaccine services, inadequate or inconsistent payment for vaccines and for vaccine administration, and the tendency to prioritize acute over preventive medical care, they noted.

The investigators assessed nationwide vaccine coverage of adults using data from the 2013 and 2014 National Health Interview Survey, which annually collects health information from a large, nationally representative sample of households via in-person interviews. The 2014 sample included 36,324 adults who self-reported their vaccination status (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2016;65:1-36).

Coverage for Tdap slightly increased 2.9 percentage points to 20.1% of the eligible population in 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, and coverage for herpes zoster among high-risk patients aged 60 and older slightly increased 3.6 percentage points to 27.9% of the population. Coverage for the other five vaccines remained steady and low: for the influenza vaccine, 43.2% of the population; for the pneumococcal vaccine, 20.3% of high-risk younger adults and 61.3% of very high-risk older adults; for the Td vaccine, 62.2%; for hepatitis A, 9%; for hepatitis B, 24.5%; and for HPV, coverage was 8.2% for men and 40.2% for women aged 19-26 years.

As expected, vaccine coverage was lower for people who didn’t have health insurance, didn’t have a usual site for receiving health care, and didn’t have any physician contacts during the preceding year. However, even among adults who had health insurance and had 10 or more physician contacts within the past year, up to 88% reported that they hadn’t received vaccinations that were recommended for everyone or for specific populations.

Racial and ethnic gaps in vaccine coverage persisted for five of these vaccines and actually worsened for the Tdap and herpes zoster vaccines.

Advice from health care providers is strongly associated with delivery of adult vaccinations. To address these gaps in vaccine coverage, clinicians should consider routine assessment of all adult patients’ vaccine needs, use of a reminder/recall system, use of standing-order programs for vaccination, and assessment of their practices’ vaccination rates. “Efforts are also needed to identify adults who do not have a regular provider or insurance and who report fewer health care visits,” Dr. Williams and his associates said.

The CDC updates vaccine recommendations annually and publishes them in the U.S. Adult Immunization Schedule, which is “a ready resource for persons who provide healthcare services in various settings,” they added.

The CDC supported the study. The authors’ financial disclosures were not provided.

Vaccine coverage of adults in the United States continues to be low for the seven vaccines currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, according to a study published in MMWR.

Illness attributable to vaccine-preventable diseases is more prevalent among adults than among children, and is especially high among the oldest adults.

For example, an estimated 50%-70% of influenza-related hospitalizations, 80%-90% of influenza-related deaths, and 50% of invasive pneumococcal disease each year occur in people aged 65 years and older, noted Dr. Walter W. Williams of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC, Atlanta, and his associates.

The influenza vaccine is recommended for all adults every year; the Td (pneumococcal, tetanus, diphtheria), Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis), hepatitis A, hepatitis B, herpes zoster, and HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccines are routinely recommended for many adults based on patient age, underlying medical conditions, lifestyle factors, occupation, travel, and other considerations.

However, adult vaccination coverage is low because of limited public awareness about the need for these vaccines, lack of vaccine requirements for adults like the immunization requirements in place for children, failure to incorporate routine vaccine assessments and recommendations in adult health care visits, the costs of stocking vaccines and providing vaccine services, inadequate or inconsistent payment for vaccines and for vaccine administration, and the tendency to prioritize acute over preventive medical care, they noted.

The investigators assessed nationwide vaccine coverage of adults using data from the 2013 and 2014 National Health Interview Survey, which annually collects health information from a large, nationally representative sample of households via in-person interviews. The 2014 sample included 36,324 adults who self-reported their vaccination status (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2016;65:1-36).

Coverage for Tdap slightly increased 2.9 percentage points to 20.1% of the eligible population in 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, and coverage for herpes zoster among high-risk patients aged 60 and older slightly increased 3.6 percentage points to 27.9% of the population. Coverage for the other five vaccines remained steady and low: for the influenza vaccine, 43.2% of the population; for the pneumococcal vaccine, 20.3% of high-risk younger adults and 61.3% of very high-risk older adults; for the Td vaccine, 62.2%; for hepatitis A, 9%; for hepatitis B, 24.5%; and for HPV, coverage was 8.2% for men and 40.2% for women aged 19-26 years.

As expected, vaccine coverage was lower for people who didn’t have health insurance, didn’t have a usual site for receiving health care, and didn’t have any physician contacts during the preceding year. However, even among adults who had health insurance and had 10 or more physician contacts within the past year, up to 88% reported that they hadn’t received vaccinations that were recommended for everyone or for specific populations.

Racial and ethnic gaps in vaccine coverage persisted for five of these vaccines and actually worsened for the Tdap and herpes zoster vaccines.

Advice from health care providers is strongly associated with delivery of adult vaccinations. To address these gaps in vaccine coverage, clinicians should consider routine assessment of all adult patients’ vaccine needs, use of a reminder/recall system, use of standing-order programs for vaccination, and assessment of their practices’ vaccination rates. “Efforts are also needed to identify adults who do not have a regular provider or insurance and who report fewer health care visits,” Dr. Williams and his associates said.

The CDC updates vaccine recommendations annually and publishes them in the U.S. Adult Immunization Schedule, which is “a ready resource for persons who provide healthcare services in various settings,” they added.

The CDC supported the study. The authors’ financial disclosures were not provided.

from Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Key clinical point: Vaccine coverage of adults in the United States remains low for the seven vaccines currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Major finding: Vaccine coverage was 20.1% for Tdap, 27.9% for herpes zoster, 43.2% for influenza, 20.3%-61.3% for pneumococcal disease, 62.2% for Td, 9.0% for hepatitis A, 24.5% for hepatitis B, and 8.2%-40.2% for HPV.

Data source: An analysis of self-reported vaccine status in a nationally representative sample of 36,324 adults participating in the cross-sectional National Health Interview Survey.

Disclosures: The CDC supported the study. The authors’ financial disclosures were not provided.

Watch for failure to thrive in children with eosinophilic esophagitis

Be on the lookout for failure to thrive among pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, according to a letter to the editor of Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology by Dr. Brenda Paquet of Sainte-Justine University Hospital Center in Montreal, and her colleagues.

These investigators reviewed charts for all children referred to their allergy clinic with a diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) from 2004 to 2012. In addition to a standard clinical evaluation, patients had undergone a series of food and respiratory skin prick tests and food patch testing. Dr. Paquet and her associates also reviewed anthropometric measurements for the children and applied failure to thrive (FTT) criteria to all growth parameters available from birth.

Of 62 patients referred to the clinic, 15 (24%) met at least one of the six criteria for FTT, and more than half (n = 8) met at least two criteria. The most frequent FTT criterion met was a weight deceleration crossing two major percentile lines.

FTT should be assessed through different growth characteristics, such as weight, length, growth velocity, and body mass index, Dr Paquet and her associates wrote. “Because no single clinical feature can accurately predict it, it is important to maintain a high level of suspicion for FTT in children with a confirmed or suspected diagnosis of EoE, and inversely, EoE should be included in the differential diagnosis of FTT.” Although FTT usually resolves, it can persist in some children despite medical treatment, “highlighting the need for research and new therapies.”

Read the article in Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (2016 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.09.015).

Be on the lookout for failure to thrive among pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, according to a letter to the editor of Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology by Dr. Brenda Paquet of Sainte-Justine University Hospital Center in Montreal, and her colleagues.

These investigators reviewed charts for all children referred to their allergy clinic with a diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) from 2004 to 2012. In addition to a standard clinical evaluation, patients had undergone a series of food and respiratory skin prick tests and food patch testing. Dr. Paquet and her associates also reviewed anthropometric measurements for the children and applied failure to thrive (FTT) criteria to all growth parameters available from birth.

Of 62 patients referred to the clinic, 15 (24%) met at least one of the six criteria for FTT, and more than half (n = 8) met at least two criteria. The most frequent FTT criterion met was a weight deceleration crossing two major percentile lines.

FTT should be assessed through different growth characteristics, such as weight, length, growth velocity, and body mass index, Dr Paquet and her associates wrote. “Because no single clinical feature can accurately predict it, it is important to maintain a high level of suspicion for FTT in children with a confirmed or suspected diagnosis of EoE, and inversely, EoE should be included in the differential diagnosis of FTT.” Although FTT usually resolves, it can persist in some children despite medical treatment, “highlighting the need for research and new therapies.”

Read the article in Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (2016 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.09.015).

Be on the lookout for failure to thrive among pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, according to a letter to the editor of Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology by Dr. Brenda Paquet of Sainte-Justine University Hospital Center in Montreal, and her colleagues.

These investigators reviewed charts for all children referred to their allergy clinic with a diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) from 2004 to 2012. In addition to a standard clinical evaluation, patients had undergone a series of food and respiratory skin prick tests and food patch testing. Dr. Paquet and her associates also reviewed anthropometric measurements for the children and applied failure to thrive (FTT) criteria to all growth parameters available from birth.

Of 62 patients referred to the clinic, 15 (24%) met at least one of the six criteria for FTT, and more than half (n = 8) met at least two criteria. The most frequent FTT criterion met was a weight deceleration crossing two major percentile lines.

FTT should be assessed through different growth characteristics, such as weight, length, growth velocity, and body mass index, Dr Paquet and her associates wrote. “Because no single clinical feature can accurately predict it, it is important to maintain a high level of suspicion for FTT in children with a confirmed or suspected diagnosis of EoE, and inversely, EoE should be included in the differential diagnosis of FTT.” Although FTT usually resolves, it can persist in some children despite medical treatment, “highlighting the need for research and new therapies.”

Read the article in Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (2016 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.09.015).

FROM ANNALS OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA & IMMUNOLOGY

U.S. flu activity at its highest level yet

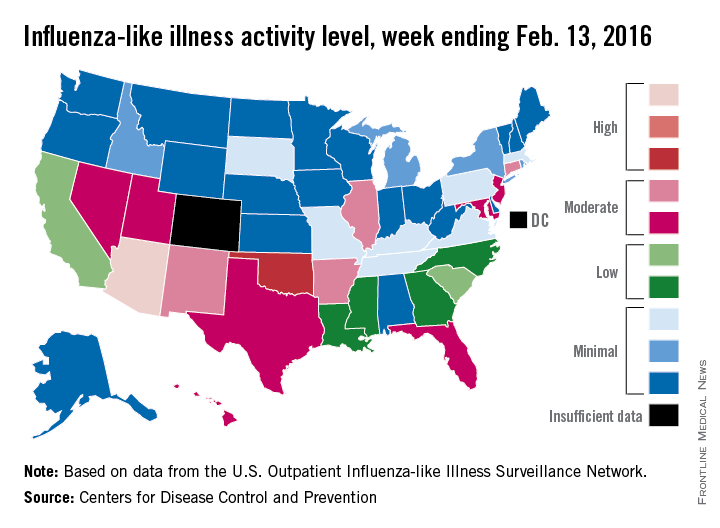

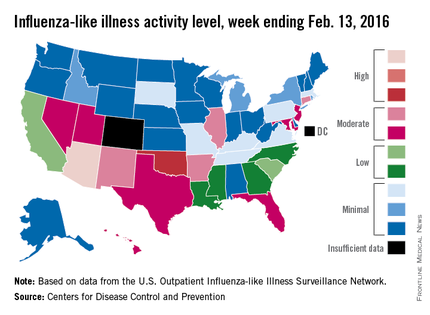

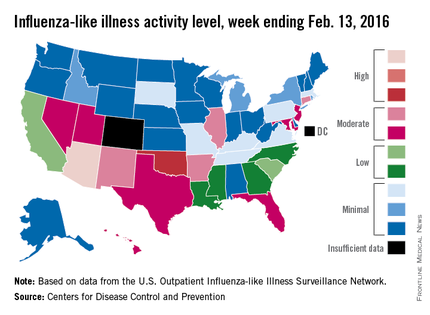

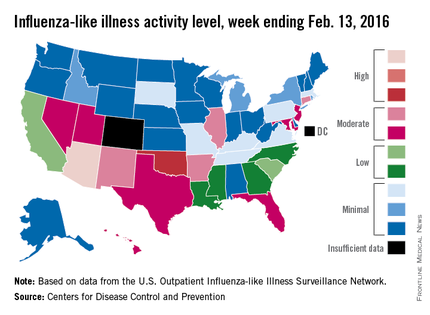

Activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) was at its highest level so far for week 18 of the 2015-2016 flu season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That increased activity put Arizona and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity for the week ending Feb. 13. Joining them in the “high” range of activity was Oklahoma at level 8, the CDC reported Feb. 19.

The percentage of visits for ILI in week 18 was 3.1%, higher than the national baseline of 2.1% and the highest level of the flu season. For the week, 30 states were at level 2 or higher on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, which is the highest number for the season. States in the “moderate” range were Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, and New Mexico at level 7 and Florida, Hawaii, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, Texas, and Utah at level 6. California and South Carolina (level 5) and Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and North Carolina (level 4) took their place in the “low” range, data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network show.

Two ILI-related pediatric deaths were reported for the week – one of which occurred during the week ending Jan. 16 – bringing the total to 13 for the season. Three of those deaths occurred in Florida and two in California, with Arizona, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Nevada, Puerto Rico, Tennessee, and Washington each reporting one death, the CDC said.

Since Oct. 1, 2015, the overall ILI-related hospitalization rate is 4.1 per 100,000 population, with 1,147 laboratory-confirmed flu hospitalizations reported. Among all hospitalizations, 71.1% were associated with influenza A, 26.4% with influenza B, 1.7% with influenza A and B coinfection, and 0.8% had no virus type information. Hospitalization data come from the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, which covers more than 70 counties in 10 states as well as 3 additional states.

Activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) was at its highest level so far for week 18 of the 2015-2016 flu season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That increased activity put Arizona and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity for the week ending Feb. 13. Joining them in the “high” range of activity was Oklahoma at level 8, the CDC reported Feb. 19.

The percentage of visits for ILI in week 18 was 3.1%, higher than the national baseline of 2.1% and the highest level of the flu season. For the week, 30 states were at level 2 or higher on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, which is the highest number for the season. States in the “moderate” range were Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, and New Mexico at level 7 and Florida, Hawaii, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, Texas, and Utah at level 6. California and South Carolina (level 5) and Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and North Carolina (level 4) took their place in the “low” range, data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network show.

Two ILI-related pediatric deaths were reported for the week – one of which occurred during the week ending Jan. 16 – bringing the total to 13 for the season. Three of those deaths occurred in Florida and two in California, with Arizona, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Nevada, Puerto Rico, Tennessee, and Washington each reporting one death, the CDC said.

Since Oct. 1, 2015, the overall ILI-related hospitalization rate is 4.1 per 100,000 population, with 1,147 laboratory-confirmed flu hospitalizations reported. Among all hospitalizations, 71.1% were associated with influenza A, 26.4% with influenza B, 1.7% with influenza A and B coinfection, and 0.8% had no virus type information. Hospitalization data come from the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, which covers more than 70 counties in 10 states as well as 3 additional states.

Activity of influenza-like illness (ILI) was at its highest level so far for week 18 of the 2015-2016 flu season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That increased activity put Arizona and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity for the week ending Feb. 13. Joining them in the “high” range of activity was Oklahoma at level 8, the CDC reported Feb. 19.

The percentage of visits for ILI in week 18 was 3.1%, higher than the national baseline of 2.1% and the highest level of the flu season. For the week, 30 states were at level 2 or higher on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, which is the highest number for the season. States in the “moderate” range were Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, and New Mexico at level 7 and Florida, Hawaii, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, Texas, and Utah at level 6. California and South Carolina (level 5) and Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and North Carolina (level 4) took their place in the “low” range, data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network show.

Two ILI-related pediatric deaths were reported for the week – one of which occurred during the week ending Jan. 16 – bringing the total to 13 for the season. Three of those deaths occurred in Florida and two in California, with Arizona, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Nevada, Puerto Rico, Tennessee, and Washington each reporting one death, the CDC said.

Since Oct. 1, 2015, the overall ILI-related hospitalization rate is 4.1 per 100,000 population, with 1,147 laboratory-confirmed flu hospitalizations reported. Among all hospitalizations, 71.1% were associated with influenza A, 26.4% with influenza B, 1.7% with influenza A and B coinfection, and 0.8% had no virus type information. Hospitalization data come from the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, which covers more than 70 counties in 10 states as well as 3 additional states.

TB declines among foreign-born in U.S.

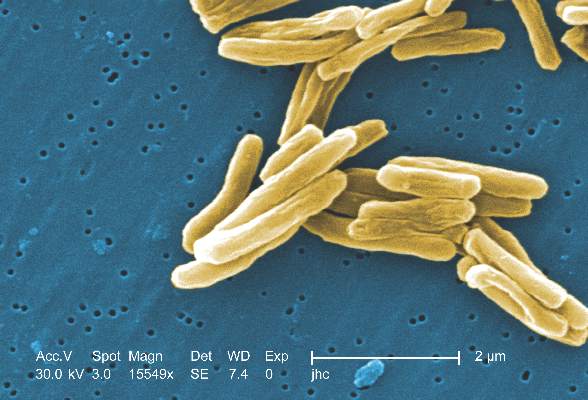

Tuberculosis rates among foreign-born people living in the United States have fallen by nearly 20%, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report in PLOS One.

From 2007 to 2011, there was an overall decline of 1,456 TB cases (–19.3%) among all foreign-born people in the United States, wrote Dr. Brian Baker of the CDC’s division of tuberculosis elimination, and colleagues. The largest relative declines in case counts were among those who emigrated within the past 3 years from Mexico (–56.1%, –270 cases); the Philippines (–52.5%, –180 cases), and India (–39.8%, –101 cases).

Factors contributing to the declines varied by country of origin.

Among recent entrants born in Mexico, 80.7% of the case count decline was attributable to a decrease in people from that country coming to the United States, while declines among recent entrants from the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China were almost exclusively (95.5%-100%) the result of decreases in TB case rates.

TB rates also declined among foreign-born individuals who have been in the United States for 3 years or more, the investigators noted. There was an 8.9% decline in this population (–443 cases) that resulted entirely from a decrease in the TB case rate.

Strategies such as investment in overseas TB control, as well as expanded testing of high-risk subgroups living in the United States, “will be necessary to achieve further declines in TB morbidity among foreign-born persons,” the authors wrote.

Read the article in PLOS One (2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147353)

Tuberculosis rates among foreign-born people living in the United States have fallen by nearly 20%, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report in PLOS One.

From 2007 to 2011, there was an overall decline of 1,456 TB cases (–19.3%) among all foreign-born people in the United States, wrote Dr. Brian Baker of the CDC’s division of tuberculosis elimination, and colleagues. The largest relative declines in case counts were among those who emigrated within the past 3 years from Mexico (–56.1%, –270 cases); the Philippines (–52.5%, –180 cases), and India (–39.8%, –101 cases).

Factors contributing to the declines varied by country of origin.

Among recent entrants born in Mexico, 80.7% of the case count decline was attributable to a decrease in people from that country coming to the United States, while declines among recent entrants from the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China were almost exclusively (95.5%-100%) the result of decreases in TB case rates.

TB rates also declined among foreign-born individuals who have been in the United States for 3 years or more, the investigators noted. There was an 8.9% decline in this population (–443 cases) that resulted entirely from a decrease in the TB case rate.

Strategies such as investment in overseas TB control, as well as expanded testing of high-risk subgroups living in the United States, “will be necessary to achieve further declines in TB morbidity among foreign-born persons,” the authors wrote.

Read the article in PLOS One (2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147353)

Tuberculosis rates among foreign-born people living in the United States have fallen by nearly 20%, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report in PLOS One.

From 2007 to 2011, there was an overall decline of 1,456 TB cases (–19.3%) among all foreign-born people in the United States, wrote Dr. Brian Baker of the CDC’s division of tuberculosis elimination, and colleagues. The largest relative declines in case counts were among those who emigrated within the past 3 years from Mexico (–56.1%, –270 cases); the Philippines (–52.5%, –180 cases), and India (–39.8%, –101 cases).

Factors contributing to the declines varied by country of origin.

Among recent entrants born in Mexico, 80.7% of the case count decline was attributable to a decrease in people from that country coming to the United States, while declines among recent entrants from the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China were almost exclusively (95.5%-100%) the result of decreases in TB case rates.

TB rates also declined among foreign-born individuals who have been in the United States for 3 years or more, the investigators noted. There was an 8.9% decline in this population (–443 cases) that resulted entirely from a decrease in the TB case rate.

Strategies such as investment in overseas TB control, as well as expanded testing of high-risk subgroups living in the United States, “will be necessary to achieve further declines in TB morbidity among foreign-born persons,” the authors wrote.

Read the article in PLOS One (2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147353)

FROM PLOS ONE

Why so many pertussis outbreaks despite acellular pertussis vaccine? A call to action

There has been a justified re-examination of acellular pertussis vaccine (aP)1,2 in light of the multiple large outbreaks of pertussis since 2000, particularly the two large California outbreaks in 2010 and 2014.

Lessons learned: aP protection is less durable than originally thought, and much pertussis is not in infants, but in the school-age and adolescent populations.

aP appears to produce reasonable protection (approximately 84% overall) for infants and preschool children, plus a much improved adverse effect profile, compared with whole cell pertussis vaccine (WCP), which provided approximately 94% protection.1 This 10% difference in aP versus WCP, however, means that herd immunity is more difficult to attain. The accepted pertussis immunization rate needed to provide herd immunity is 92%-94%. Because our current tools (DTaP and Tdap) provide only 84% protection at least in infants and preschoolers, even 100% uptake may leave us 6% to 8% short of the threshold for complete herd immunity.

The California outbreak data from school-age and teenage populations show protection rates drop each year post aP booster. That means that by the fourth year after the last dose, protection is less than 10%. So despite a Tdap dose at 11- to 12-years-of-age, protection gaps occur in 8-to 10-year-olds and 14- to 18-year-olds. These vulnerable periods in older children add to aP’s 84% vs. WCP’s 94% protection for those greater than 3 years of age, explaining more frequent pertussis outbreaks as the pool of WCP-immunized children among older populations decreased.

But before we place all blame on switching to aP, consider that we can now confirm more pertussis infections with molecular assays than was possible with culture and fluorescent assay testing in the WCP era. So improved testing sensitivity means more reports of minimally symptomatic cases that may have been missed before. So WCP, if still used today, might not show 94% protection either.

Additionally, aPs rely heavily on pertactin as a target antigen,3 likely less than WCP, given that WCP contained all pertussis antigens rather than just the 3-5 purified antigens in aPs. So the emergence of pertactin-altered pertussis strains could disproportionately affect protection from aP, compared with WCP.

There seem to be no quick fixes to preventing outbreaks using aPs as our vaccine. One suggestion by the authors of the California outbreak report is to use aP mostly to terminate outbreaks rather than routinely in late childhood. My concern is that if we do not continue routine use in 4-to 6-year-olds, 10-to 11-year-olds, and in early adulthood, the vulnerable proportion of the population during outbreaks would be larger, making outbreaks more difficult to terminate. So continuing to produce some protection, albeit short-lived, with current schedules of aP vaccines seems important.

Also remember that T cells, particularly TH 17 pertussis-specific cells, may be as important as pertussis antibody. Therefore, crafting pertussis vaccines that yield improved antibody plus T cell responses is the current goal. Disease and WCP seem to elicit more T-17 response than aP. One method to craft a better vaccine is to use antigen blends that differ from those in the current vaccines, such as antigens derived from circulating pertussis strains instead of the standard laboratory strain. Another option is to use current antigens but with more potent adjuvants. Such vaccines are likely 5 years away.

But we need to have reasonable expectations for pertussis vaccines. Pertussis infection begins in respiratory epithelium. Many of the most obvious signs and symptoms are due to destruction of ciliated respiratory epithelium plus increased tenacity/volume of secretions. Can a parenterally administered vaccine that induces mostly serum antibody protect against infection of epithelium where antibody concentrations are likely 10% or less than in serum? The short answer is – likely not. We should expect neither aP nor WCP to consistently protect against pertussis infection, but it does seem reasonable to expect aP to reduce disease severity. Preventing infections awaits a vaccine that induces surface IgA. Mucosally administered vaccines produce surface IgA – for example, rotavirus vaccine – but no mucosal pertussis vaccine appears imminent.

A key question is whether our most vulnerable populations, young children, have increased morbidity and mortality. Data from the California suggest an increase but mostly in infants under 6 months of age, the group not old enough to benefit from even the most effective of infant vaccines. Protecting young infants depends on vaccine administered prenatally to mothers. The over-representation of the Hispanic infants among fatalities shows a population on which to focus with maternal immunization. Hopefully, the recent universal TdaP recommendation in pregnancy will help when maternal immunization is higher than current approximately 50% rates.4

Despite the problems, it seems clear that we must continue to use current aP vaccines according to the current schedules, attempting to get as close to 100% uptake as possible. While the current, nearly 10% unimmunized rates add to the likelihood that we are losing complete herd immunity, partial herd immunity is better than no herd immunity.

Expectations: There will be ongoing outbreaks. Continue to be alert for signs of pertussis. They are often less obvious in older patients, and may be as subtle as more than 2 weeks of persistent cough. During outbreaks, we may be called upon to give aP doses at intervals shorter than the usual schedule.

Our responsibility: Do not become discouraged or lose enthusiasm for aP, but explain to parents that because aP is less reactogenic, it produces less protection and is less durable, particularly in school-age children. But please emphasize that modest protection is best in the youngest and modest protection of older children is better than none. Emphasize that the adverse effect profile of current aPs puts the harm/benefit balance heavily in favor of aP.

Bottom line: We can hopefully do better than the current 88% to 92% rate of aP vaccine uptake. We need to get as close to 100% uptake as possible until new vaccines or new strategies become available.

1. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 7; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw051.

2. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 5; doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3326.

3. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007 Feb;6(1):47-56.

4. Vaccine. 2016 Feb 10;34(7):968-73.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He disclosed that his institution received grant support for a study on hexavalent infant vaccine containing pertussis from GlaxoSmithKline, and he was the local primary investigator.*

*Correction, 2/17/2016: An earlier version of this article incompletely stated Dr. Harrison's disclosure information.

There has been a justified re-examination of acellular pertussis vaccine (aP)1,2 in light of the multiple large outbreaks of pertussis since 2000, particularly the two large California outbreaks in 2010 and 2014.

Lessons learned: aP protection is less durable than originally thought, and much pertussis is not in infants, but in the school-age and adolescent populations.

aP appears to produce reasonable protection (approximately 84% overall) for infants and preschool children, plus a much improved adverse effect profile, compared with whole cell pertussis vaccine (WCP), which provided approximately 94% protection.1 This 10% difference in aP versus WCP, however, means that herd immunity is more difficult to attain. The accepted pertussis immunization rate needed to provide herd immunity is 92%-94%. Because our current tools (DTaP and Tdap) provide only 84% protection at least in infants and preschoolers, even 100% uptake may leave us 6% to 8% short of the threshold for complete herd immunity.

The California outbreak data from school-age and teenage populations show protection rates drop each year post aP booster. That means that by the fourth year after the last dose, protection is less than 10%. So despite a Tdap dose at 11- to 12-years-of-age, protection gaps occur in 8-to 10-year-olds and 14- to 18-year-olds. These vulnerable periods in older children add to aP’s 84% vs. WCP’s 94% protection for those greater than 3 years of age, explaining more frequent pertussis outbreaks as the pool of WCP-immunized children among older populations decreased.

But before we place all blame on switching to aP, consider that we can now confirm more pertussis infections with molecular assays than was possible with culture and fluorescent assay testing in the WCP era. So improved testing sensitivity means more reports of minimally symptomatic cases that may have been missed before. So WCP, if still used today, might not show 94% protection either.

Additionally, aPs rely heavily on pertactin as a target antigen,3 likely less than WCP, given that WCP contained all pertussis antigens rather than just the 3-5 purified antigens in aPs. So the emergence of pertactin-altered pertussis strains could disproportionately affect protection from aP, compared with WCP.

There seem to be no quick fixes to preventing outbreaks using aPs as our vaccine. One suggestion by the authors of the California outbreak report is to use aP mostly to terminate outbreaks rather than routinely in late childhood. My concern is that if we do not continue routine use in 4-to 6-year-olds, 10-to 11-year-olds, and in early adulthood, the vulnerable proportion of the population during outbreaks would be larger, making outbreaks more difficult to terminate. So continuing to produce some protection, albeit short-lived, with current schedules of aP vaccines seems important.

Also remember that T cells, particularly TH 17 pertussis-specific cells, may be as important as pertussis antibody. Therefore, crafting pertussis vaccines that yield improved antibody plus T cell responses is the current goal. Disease and WCP seem to elicit more T-17 response than aP. One method to craft a better vaccine is to use antigen blends that differ from those in the current vaccines, such as antigens derived from circulating pertussis strains instead of the standard laboratory strain. Another option is to use current antigens but with more potent adjuvants. Such vaccines are likely 5 years away.

But we need to have reasonable expectations for pertussis vaccines. Pertussis infection begins in respiratory epithelium. Many of the most obvious signs and symptoms are due to destruction of ciliated respiratory epithelium plus increased tenacity/volume of secretions. Can a parenterally administered vaccine that induces mostly serum antibody protect against infection of epithelium where antibody concentrations are likely 10% or less than in serum? The short answer is – likely not. We should expect neither aP nor WCP to consistently protect against pertussis infection, but it does seem reasonable to expect aP to reduce disease severity. Preventing infections awaits a vaccine that induces surface IgA. Mucosally administered vaccines produce surface IgA – for example, rotavirus vaccine – but no mucosal pertussis vaccine appears imminent.

A key question is whether our most vulnerable populations, young children, have increased morbidity and mortality. Data from the California suggest an increase but mostly in infants under 6 months of age, the group not old enough to benefit from even the most effective of infant vaccines. Protecting young infants depends on vaccine administered prenatally to mothers. The over-representation of the Hispanic infants among fatalities shows a population on which to focus with maternal immunization. Hopefully, the recent universal TdaP recommendation in pregnancy will help when maternal immunization is higher than current approximately 50% rates.4

Despite the problems, it seems clear that we must continue to use current aP vaccines according to the current schedules, attempting to get as close to 100% uptake as possible. While the current, nearly 10% unimmunized rates add to the likelihood that we are losing complete herd immunity, partial herd immunity is better than no herd immunity.

Expectations: There will be ongoing outbreaks. Continue to be alert for signs of pertussis. They are often less obvious in older patients, and may be as subtle as more than 2 weeks of persistent cough. During outbreaks, we may be called upon to give aP doses at intervals shorter than the usual schedule.

Our responsibility: Do not become discouraged or lose enthusiasm for aP, but explain to parents that because aP is less reactogenic, it produces less protection and is less durable, particularly in school-age children. But please emphasize that modest protection is best in the youngest and modest protection of older children is better than none. Emphasize that the adverse effect profile of current aPs puts the harm/benefit balance heavily in favor of aP.

Bottom line: We can hopefully do better than the current 88% to 92% rate of aP vaccine uptake. We need to get as close to 100% uptake as possible until new vaccines or new strategies become available.

1. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 7; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw051.

2. Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 5; doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3326.

3. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007 Feb;6(1):47-56.

4. Vaccine. 2016 Feb 10;34(7):968-73.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He disclosed that his institution received grant support for a study on hexavalent infant vaccine containing pertussis from GlaxoSmithKline, and he was the local primary investigator.*

*Correction, 2/17/2016: An earlier version of this article incompletely stated Dr. Harrison's disclosure information.

There has been a justified re-examination of acellular pertussis vaccine (aP)1,2 in light of the multiple large outbreaks of pertussis since 2000, particularly the two large California outbreaks in 2010 and 2014.

Lessons learned: aP protection is less durable than originally thought, and much pertussis is not in infants, but in the school-age and adolescent populations.

aP appears to produce reasonable protection (approximately 84% overall) for infants and preschool children, plus a much improved adverse effect profile, compared with whole cell pertussis vaccine (WCP), which provided approximately 94% protection.1 This 10% difference in aP versus WCP, however, means that herd immunity is more difficult to attain. The accepted pertussis immunization rate needed to provide herd immunity is 92%-94%. Because our current tools (DTaP and Tdap) provide only 84% protection at least in infants and preschoolers, even 100% uptake may leave us 6% to 8% short of the threshold for complete herd immunity.

The California outbreak data from school-age and teenage populations show protection rates drop each year post aP booster. That means that by the fourth year after the last dose, protection is less than 10%. So despite a Tdap dose at 11- to 12-years-of-age, protection gaps occur in 8-to 10-year-olds and 14- to 18-year-olds. These vulnerable periods in older children add to aP’s 84% vs. WCP’s 94% protection for those greater than 3 years of age, explaining more frequent pertussis outbreaks as the pool of WCP-immunized children among older populations decreased.

But before we place all blame on switching to aP, consider that we can now confirm more pertussis infections with molecular assays than was possible with culture and fluorescent assay testing in the WCP era. So improved testing sensitivity means more reports of minimally symptomatic cases that may have been missed before. So WCP, if still used today, might not show 94% protection either.

Additionally, aPs rely heavily on pertactin as a target antigen,3 likely less than WCP, given that WCP contained all pertussis antigens rather than just the 3-5 purified antigens in aPs. So the emergence of pertactin-altered pertussis strains could disproportionately affect protection from aP, compared with WCP.

There seem to be no quick fixes to preventing outbreaks using aPs as our vaccine. One suggestion by the authors of the California outbreak report is to use aP mostly to terminate outbreaks rather than routinely in late childhood. My concern is that if we do not continue routine use in 4-to 6-year-olds, 10-to 11-year-olds, and in early adulthood, the vulnerable proportion of the population during outbreaks would be larger, making outbreaks more difficult to terminate. So continuing to produce some protection, albeit short-lived, with current schedules of aP vaccines seems important.

Also remember that T cells, particularly TH 17 pertussis-specific cells, may be as important as pertussis antibody. Therefore, crafting pertussis vaccines that yield improved antibody plus T cell responses is the current goal. Disease and WCP seem to elicit more T-17 response than aP. One method to craft a better vaccine is to use antigen blends that differ from those in the current vaccines, such as antigens derived from circulating pertussis strains instead of the standard laboratory strain. Another option is to use current antigens but with more potent adjuvants. Such vaccines are likely 5 years away.