User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

Children with poor lung function develop ACOS

Children with poor lung function will be more likely to develop asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap syndrome (ACOS), suggesting that prevention of this disease should be attempted in early life, a study shows.

While other research has found that patients with poor lung function in early life have poor lung function as adults, this was the first study to investigate the relationship between childhood lung function and ACOS in adult life, according to Dinh S. Bui of the University of Melbourne, and his colleagues.

The study, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, used multinomial regression models to investigate associations between childhood lung parameters at age 7 years and asthma, COPD, and ACOS at age 45 years (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Feb 1. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201606-1272OC).

“We found that ACOS participants showed evidence of persistently lower FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in 1 second] and FEV1/FVC [forced vital capacity] from childhood. This suggests that poorer childhood lung function tracked to early adult life, leading to impaired maximally attained lung function,” the researchers said.

“The study highlights that low childhood lung function is a risk factor for COPD (and ACOS) independent of smoking,” they noted.

The 1,355 study participants who had postbronchodilator (post-BD) lung function available were categorized into the following four mutually exclusive groups at age 45 years based on their asthma and COPD status: having neither asthma nor COPD (unaffected) (n = 959); having asthma alone (n = 269); having COPD alone (n = 59); having ACOS (n = 68).

Once adjusted for the sampling weights, the prevalence of current asthma alone was 13.5%, COPD alone was 4.1%, and ACOS was 2.9%. The researchers defined COPD at age 45 years as post-BD FEV1/FVC less than the Global Lung Initiative lower limit of normal. Because the associations between childhood lung function and both ACOS and COPD alone were nonlinear, the patients were grouped into quartiles based on their characteristics, such as their percent predicted FEV1 and percent predicted FEV1/FVC at 7 years, the investigators said.

Patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1 percent predicted at 7 years were 2.93 times more likely to have ACOS, compared with patients in the other quartiles for FEV1 percent predicted. Patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1/FVC percent predicted at 7 years were 16.3 times more likely to have ACOS and 5.76 times more likely to have COPD alone, compared with patients in the higher quartiles.

The researchers found large variation in childhood lung function among patients in the lowest quartiles for FEV1 and FEV1/FVC. To account for this, they conducted a sensitivity analysis, which excluded those with less than 80% predicted FEV1 and FEV1/FVC (n = 76 and 13, respectively).The associations between lung function measures and diseases in adulthood for patients in the lowest quartiles differed slightly following this adjustment. The sensitivity analysis showed that patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1 had an odds ratio of 2.4 for ACOS and that those patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1/FVC had an odds ratio of 5.2 for COPD alone and 15.1 for ACOS.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded patients with remitted asthma from the unaffected group showed childhood FEV1 was more strongly associated with ACOS for patients in the lowest quartile, compared with patients in the highest quartile (OR: 7.0, 95% CI: 2.7-18.3). This same analysis found that patients from the lowest quartile and second quartile for childhood FEV1/FVC were 6.8 and 3.9 times more likely to have COPD, respectively, compared with patients in the other quartiles. This sensitivity analysis also found that patients in the first quartile for FEV1/FVC were 19.1 times more likely to have ACOS, and patients in the second quartile for FEV1/FVC were 5.3 times more likely to have ACOS.

The researchers analyzed data from the Tasmanian Longitudinal Health Study, which began in 1968 when Tasmanian children born in 1961 and attending school in Tasmania were studied with respiratory health surveys and prebronchodilator (pre-BD) spirometry measurements. The most recent survey started in 2002. Survey respondents who had participated in past follow-up studies and/or reported symptoms of asthma or cough were invited to participate in a more detailed laboratory study from 2006 to 2008. That study included completing a questionnaire, pre-BD and post-BD spirometry, and skin prick testing. The predicted and percent predicted values for spirometry were derived from the Global Lung Initiative reference equations.

The final multinomial model was adjusted for various factors including childhood asthma, maternal smoking, and paternal smoking during childhood.

History of active smoking was significantly more frequent in patients with ACOS (73.5%) and COPD alone (73%) than in the unaffected (57%) groups. Childhood asthma, maternal asthma and atopy were more prevalent in the ACOS and asthma alone groups. ACOS and COPD participants had a higher prevalence of maternal smoking during childhood.

Individuals with ACOS had the lowest pre-BD FEV1 (percent predicted values) over time. Those with COPD alone or ACOS had significantly lower pre-BD FEV1/FVC (percent predicted values) at all time points, when patients were assessed, compared with unaffected participants. “Participants with COPD alone had significantly higher FVC at 7 and 13 years, while ACOS participants had significantly lower FVC at 45 years,” the researchers said.

“There was no evidence of effect modification by childhood lung infections, childhood asthma, maternal asthma, maternal smoking, or paternal smoking during childhood on the associations between childhood lung and the disease groups,” they noted.

The study was limited by its “relatively small sample sizes for the ACOS and COPD alone groups” and the absence of post-BD spirometry at 7 years, they added.

The researchers concluded that “screening of lung function in school-aged children may provide an opportunity to detect children likely to have ongoing poorer lung health, such as those with lung function below the lower limit of normal,” and that “[multifaceted] intervention strategies could then be implemented to reduce the burden of COPD and ACOS in adulthood.”

“I suspect that genetics may play a big role in the results, and there is increasing interest in learning how genetics are involved in COPD. A better understanding of the risk factors for lower lung function in children may also provide targets of intervention. The groups with ACOS and COPD have higher rates of maternal smoking, and while this study determined that the association between childhood low lung function and development of COPD and ACOS is independent of maternal smoking, maternal smoking still seems like a good area to target,” she said in an interview.

It would also be interesting to further study the first quartile of patients, she added. “The clinical disease for this quartile of patients covers a wide range of severities. I would be interested in dividing this group up further and learning the outcomes of their lung function and development of COPD and ACOS.”

Using inhaled corticosteroids and other medications for maintenance control, reducing and monitoring impairment, educating patients and patients’ guardians on triggers, avoiding triggers, and having an action plan for changing therapy based on symptoms or measured flows are ways to aggressively treat such conditions, said Dr. Gartman, assistant professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I*. He cited avoiding exposure to smoke, environmental pollutants, and living near highways, for those with low childhood function, as interventions that might prevent people with low lung function from later developing COPD.

Dr. Gartman added that differences between the availability of medication for children with asthma today and at the time of the study may mean there are differences between the children with low lung function in the study and those children who have low function today. A population of children with low lung function now may be experiencing relatively less asthma and more chronic lung disorders brought on by prematurity or cystic fibrosis, he noted. “As such, identification of poor function in today’s young children may carry with it a significantly different set of interventions and challenges,” Dr. Gartman said.

While asthma in children is better controlled now than it was at the time of the study, because the researchers did not provide any information about the asthma control of the study participants, “it [is] hard for me to say if better asthma drugs in those children would have made a difference in long-term outcomes of COPD and ACOS as an adult,” Dr. Swaminathan noted.

“The best thing we currently can do for children with low lung function is try and determine the underlying cause and treat any active diseases [such as asthma] that we can. This study reminds us of the need to keep searching for causes of low lung function that may be reversible,” she said.

The investigators recommended future research to understand the risk factors for lower lung function in children. They called for studies that address “the risk factors over adulthood that interact with lower lung function to increase the risk of rapid lung function decline.”

The study was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia research grant, the University of Melbourne, Clifford Craig Medical Research Trust of Tasmania, the Victorian, Queensland & Tasmanian Asthma Foundations, The Royal Hobart Hospital, Helen MacPherson Smith Trust, GlaxoSmithKline, and John L Hopper. Five authors were supported by the research grant; the others reported no conflicts. Dr. Swaminathan and Dr. Gartman had no disclosures.

*This story was updated March 16, 2017, with Dr. Gartman's full affiliation.

Children with poor lung function will be more likely to develop asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap syndrome (ACOS), suggesting that prevention of this disease should be attempted in early life, a study shows.

While other research has found that patients with poor lung function in early life have poor lung function as adults, this was the first study to investigate the relationship between childhood lung function and ACOS in adult life, according to Dinh S. Bui of the University of Melbourne, and his colleagues.

The study, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, used multinomial regression models to investigate associations between childhood lung parameters at age 7 years and asthma, COPD, and ACOS at age 45 years (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Feb 1. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201606-1272OC).

“We found that ACOS participants showed evidence of persistently lower FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in 1 second] and FEV1/FVC [forced vital capacity] from childhood. This suggests that poorer childhood lung function tracked to early adult life, leading to impaired maximally attained lung function,” the researchers said.

“The study highlights that low childhood lung function is a risk factor for COPD (and ACOS) independent of smoking,” they noted.

The 1,355 study participants who had postbronchodilator (post-BD) lung function available were categorized into the following four mutually exclusive groups at age 45 years based on their asthma and COPD status: having neither asthma nor COPD (unaffected) (n = 959); having asthma alone (n = 269); having COPD alone (n = 59); having ACOS (n = 68).

Once adjusted for the sampling weights, the prevalence of current asthma alone was 13.5%, COPD alone was 4.1%, and ACOS was 2.9%. The researchers defined COPD at age 45 years as post-BD FEV1/FVC less than the Global Lung Initiative lower limit of normal. Because the associations between childhood lung function and both ACOS and COPD alone were nonlinear, the patients were grouped into quartiles based on their characteristics, such as their percent predicted FEV1 and percent predicted FEV1/FVC at 7 years, the investigators said.

Patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1 percent predicted at 7 years were 2.93 times more likely to have ACOS, compared with patients in the other quartiles for FEV1 percent predicted. Patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1/FVC percent predicted at 7 years were 16.3 times more likely to have ACOS and 5.76 times more likely to have COPD alone, compared with patients in the higher quartiles.

The researchers found large variation in childhood lung function among patients in the lowest quartiles for FEV1 and FEV1/FVC. To account for this, they conducted a sensitivity analysis, which excluded those with less than 80% predicted FEV1 and FEV1/FVC (n = 76 and 13, respectively).The associations between lung function measures and diseases in adulthood for patients in the lowest quartiles differed slightly following this adjustment. The sensitivity analysis showed that patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1 had an odds ratio of 2.4 for ACOS and that those patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1/FVC had an odds ratio of 5.2 for COPD alone and 15.1 for ACOS.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded patients with remitted asthma from the unaffected group showed childhood FEV1 was more strongly associated with ACOS for patients in the lowest quartile, compared with patients in the highest quartile (OR: 7.0, 95% CI: 2.7-18.3). This same analysis found that patients from the lowest quartile and second quartile for childhood FEV1/FVC were 6.8 and 3.9 times more likely to have COPD, respectively, compared with patients in the other quartiles. This sensitivity analysis also found that patients in the first quartile for FEV1/FVC were 19.1 times more likely to have ACOS, and patients in the second quartile for FEV1/FVC were 5.3 times more likely to have ACOS.

The researchers analyzed data from the Tasmanian Longitudinal Health Study, which began in 1968 when Tasmanian children born in 1961 and attending school in Tasmania were studied with respiratory health surveys and prebronchodilator (pre-BD) spirometry measurements. The most recent survey started in 2002. Survey respondents who had participated in past follow-up studies and/or reported symptoms of asthma or cough were invited to participate in a more detailed laboratory study from 2006 to 2008. That study included completing a questionnaire, pre-BD and post-BD spirometry, and skin prick testing. The predicted and percent predicted values for spirometry were derived from the Global Lung Initiative reference equations.

The final multinomial model was adjusted for various factors including childhood asthma, maternal smoking, and paternal smoking during childhood.

History of active smoking was significantly more frequent in patients with ACOS (73.5%) and COPD alone (73%) than in the unaffected (57%) groups. Childhood asthma, maternal asthma and atopy were more prevalent in the ACOS and asthma alone groups. ACOS and COPD participants had a higher prevalence of maternal smoking during childhood.

Individuals with ACOS had the lowest pre-BD FEV1 (percent predicted values) over time. Those with COPD alone or ACOS had significantly lower pre-BD FEV1/FVC (percent predicted values) at all time points, when patients were assessed, compared with unaffected participants. “Participants with COPD alone had significantly higher FVC at 7 and 13 years, while ACOS participants had significantly lower FVC at 45 years,” the researchers said.

“There was no evidence of effect modification by childhood lung infections, childhood asthma, maternal asthma, maternal smoking, or paternal smoking during childhood on the associations between childhood lung and the disease groups,” they noted.

The study was limited by its “relatively small sample sizes for the ACOS and COPD alone groups” and the absence of post-BD spirometry at 7 years, they added.

The researchers concluded that “screening of lung function in school-aged children may provide an opportunity to detect children likely to have ongoing poorer lung health, such as those with lung function below the lower limit of normal,” and that “[multifaceted] intervention strategies could then be implemented to reduce the burden of COPD and ACOS in adulthood.”

“I suspect that genetics may play a big role in the results, and there is increasing interest in learning how genetics are involved in COPD. A better understanding of the risk factors for lower lung function in children may also provide targets of intervention. The groups with ACOS and COPD have higher rates of maternal smoking, and while this study determined that the association between childhood low lung function and development of COPD and ACOS is independent of maternal smoking, maternal smoking still seems like a good area to target,” she said in an interview.

It would also be interesting to further study the first quartile of patients, she added. “The clinical disease for this quartile of patients covers a wide range of severities. I would be interested in dividing this group up further and learning the outcomes of their lung function and development of COPD and ACOS.”

Using inhaled corticosteroids and other medications for maintenance control, reducing and monitoring impairment, educating patients and patients’ guardians on triggers, avoiding triggers, and having an action plan for changing therapy based on symptoms or measured flows are ways to aggressively treat such conditions, said Dr. Gartman, assistant professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I*. He cited avoiding exposure to smoke, environmental pollutants, and living near highways, for those with low childhood function, as interventions that might prevent people with low lung function from later developing COPD.

Dr. Gartman added that differences between the availability of medication for children with asthma today and at the time of the study may mean there are differences between the children with low lung function in the study and those children who have low function today. A population of children with low lung function now may be experiencing relatively less asthma and more chronic lung disorders brought on by prematurity or cystic fibrosis, he noted. “As such, identification of poor function in today’s young children may carry with it a significantly different set of interventions and challenges,” Dr. Gartman said.

While asthma in children is better controlled now than it was at the time of the study, because the researchers did not provide any information about the asthma control of the study participants, “it [is] hard for me to say if better asthma drugs in those children would have made a difference in long-term outcomes of COPD and ACOS as an adult,” Dr. Swaminathan noted.

“The best thing we currently can do for children with low lung function is try and determine the underlying cause and treat any active diseases [such as asthma] that we can. This study reminds us of the need to keep searching for causes of low lung function that may be reversible,” she said.

The investigators recommended future research to understand the risk factors for lower lung function in children. They called for studies that address “the risk factors over adulthood that interact with lower lung function to increase the risk of rapid lung function decline.”

The study was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia research grant, the University of Melbourne, Clifford Craig Medical Research Trust of Tasmania, the Victorian, Queensland & Tasmanian Asthma Foundations, The Royal Hobart Hospital, Helen MacPherson Smith Trust, GlaxoSmithKline, and John L Hopper. Five authors were supported by the research grant; the others reported no conflicts. Dr. Swaminathan and Dr. Gartman had no disclosures.

*This story was updated March 16, 2017, with Dr. Gartman's full affiliation.

Children with poor lung function will be more likely to develop asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap syndrome (ACOS), suggesting that prevention of this disease should be attempted in early life, a study shows.

While other research has found that patients with poor lung function in early life have poor lung function as adults, this was the first study to investigate the relationship between childhood lung function and ACOS in adult life, according to Dinh S. Bui of the University of Melbourne, and his colleagues.

The study, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, used multinomial regression models to investigate associations between childhood lung parameters at age 7 years and asthma, COPD, and ACOS at age 45 years (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Feb 1. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201606-1272OC).

“We found that ACOS participants showed evidence of persistently lower FEV1 [forced expiratory volume in 1 second] and FEV1/FVC [forced vital capacity] from childhood. This suggests that poorer childhood lung function tracked to early adult life, leading to impaired maximally attained lung function,” the researchers said.

“The study highlights that low childhood lung function is a risk factor for COPD (and ACOS) independent of smoking,” they noted.

The 1,355 study participants who had postbronchodilator (post-BD) lung function available were categorized into the following four mutually exclusive groups at age 45 years based on their asthma and COPD status: having neither asthma nor COPD (unaffected) (n = 959); having asthma alone (n = 269); having COPD alone (n = 59); having ACOS (n = 68).

Once adjusted for the sampling weights, the prevalence of current asthma alone was 13.5%, COPD alone was 4.1%, and ACOS was 2.9%. The researchers defined COPD at age 45 years as post-BD FEV1/FVC less than the Global Lung Initiative lower limit of normal. Because the associations between childhood lung function and both ACOS and COPD alone were nonlinear, the patients were grouped into quartiles based on their characteristics, such as their percent predicted FEV1 and percent predicted FEV1/FVC at 7 years, the investigators said.

Patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1 percent predicted at 7 years were 2.93 times more likely to have ACOS, compared with patients in the other quartiles for FEV1 percent predicted. Patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1/FVC percent predicted at 7 years were 16.3 times more likely to have ACOS and 5.76 times more likely to have COPD alone, compared with patients in the higher quartiles.

The researchers found large variation in childhood lung function among patients in the lowest quartiles for FEV1 and FEV1/FVC. To account for this, they conducted a sensitivity analysis, which excluded those with less than 80% predicted FEV1 and FEV1/FVC (n = 76 and 13, respectively).The associations between lung function measures and diseases in adulthood for patients in the lowest quartiles differed slightly following this adjustment. The sensitivity analysis showed that patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1 had an odds ratio of 2.4 for ACOS and that those patients in the lowest quartile for FEV1/FVC had an odds ratio of 5.2 for COPD alone and 15.1 for ACOS.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded patients with remitted asthma from the unaffected group showed childhood FEV1 was more strongly associated with ACOS for patients in the lowest quartile, compared with patients in the highest quartile (OR: 7.0, 95% CI: 2.7-18.3). This same analysis found that patients from the lowest quartile and second quartile for childhood FEV1/FVC were 6.8 and 3.9 times more likely to have COPD, respectively, compared with patients in the other quartiles. This sensitivity analysis also found that patients in the first quartile for FEV1/FVC were 19.1 times more likely to have ACOS, and patients in the second quartile for FEV1/FVC were 5.3 times more likely to have ACOS.

The researchers analyzed data from the Tasmanian Longitudinal Health Study, which began in 1968 when Tasmanian children born in 1961 and attending school in Tasmania were studied with respiratory health surveys and prebronchodilator (pre-BD) spirometry measurements. The most recent survey started in 2002. Survey respondents who had participated in past follow-up studies and/or reported symptoms of asthma or cough were invited to participate in a more detailed laboratory study from 2006 to 2008. That study included completing a questionnaire, pre-BD and post-BD spirometry, and skin prick testing. The predicted and percent predicted values for spirometry were derived from the Global Lung Initiative reference equations.

The final multinomial model was adjusted for various factors including childhood asthma, maternal smoking, and paternal smoking during childhood.

History of active smoking was significantly more frequent in patients with ACOS (73.5%) and COPD alone (73%) than in the unaffected (57%) groups. Childhood asthma, maternal asthma and atopy were more prevalent in the ACOS and asthma alone groups. ACOS and COPD participants had a higher prevalence of maternal smoking during childhood.

Individuals with ACOS had the lowest pre-BD FEV1 (percent predicted values) over time. Those with COPD alone or ACOS had significantly lower pre-BD FEV1/FVC (percent predicted values) at all time points, when patients were assessed, compared with unaffected participants. “Participants with COPD alone had significantly higher FVC at 7 and 13 years, while ACOS participants had significantly lower FVC at 45 years,” the researchers said.

“There was no evidence of effect modification by childhood lung infections, childhood asthma, maternal asthma, maternal smoking, or paternal smoking during childhood on the associations between childhood lung and the disease groups,” they noted.

The study was limited by its “relatively small sample sizes for the ACOS and COPD alone groups” and the absence of post-BD spirometry at 7 years, they added.

The researchers concluded that “screening of lung function in school-aged children may provide an opportunity to detect children likely to have ongoing poorer lung health, such as those with lung function below the lower limit of normal,” and that “[multifaceted] intervention strategies could then be implemented to reduce the burden of COPD and ACOS in adulthood.”

“I suspect that genetics may play a big role in the results, and there is increasing interest in learning how genetics are involved in COPD. A better understanding of the risk factors for lower lung function in children may also provide targets of intervention. The groups with ACOS and COPD have higher rates of maternal smoking, and while this study determined that the association between childhood low lung function and development of COPD and ACOS is independent of maternal smoking, maternal smoking still seems like a good area to target,” she said in an interview.

It would also be interesting to further study the first quartile of patients, she added. “The clinical disease for this quartile of patients covers a wide range of severities. I would be interested in dividing this group up further and learning the outcomes of their lung function and development of COPD and ACOS.”

Using inhaled corticosteroids and other medications for maintenance control, reducing and monitoring impairment, educating patients and patients’ guardians on triggers, avoiding triggers, and having an action plan for changing therapy based on symptoms or measured flows are ways to aggressively treat such conditions, said Dr. Gartman, assistant professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I*. He cited avoiding exposure to smoke, environmental pollutants, and living near highways, for those with low childhood function, as interventions that might prevent people with low lung function from later developing COPD.

Dr. Gartman added that differences between the availability of medication for children with asthma today and at the time of the study may mean there are differences between the children with low lung function in the study and those children who have low function today. A population of children with low lung function now may be experiencing relatively less asthma and more chronic lung disorders brought on by prematurity or cystic fibrosis, he noted. “As such, identification of poor function in today’s young children may carry with it a significantly different set of interventions and challenges,” Dr. Gartman said.

While asthma in children is better controlled now than it was at the time of the study, because the researchers did not provide any information about the asthma control of the study participants, “it [is] hard for me to say if better asthma drugs in those children would have made a difference in long-term outcomes of COPD and ACOS as an adult,” Dr. Swaminathan noted.

“The best thing we currently can do for children with low lung function is try and determine the underlying cause and treat any active diseases [such as asthma] that we can. This study reminds us of the need to keep searching for causes of low lung function that may be reversible,” she said.

The investigators recommended future research to understand the risk factors for lower lung function in children. They called for studies that address “the risk factors over adulthood that interact with lower lung function to increase the risk of rapid lung function decline.”

The study was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia research grant, the University of Melbourne, Clifford Craig Medical Research Trust of Tasmania, the Victorian, Queensland & Tasmanian Asthma Foundations, The Royal Hobart Hospital, Helen MacPherson Smith Trust, GlaxoSmithKline, and John L Hopper. Five authors were supported by the research grant; the others reported no conflicts. Dr. Swaminathan and Dr. Gartman had no disclosures.

*This story was updated March 16, 2017, with Dr. Gartman's full affiliation.

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine beats Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia

Routine use of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) reduced the incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia by 95% from a time period before to a time period after the vaccine was implemented, based on a review of more than 57,000 blood cultures from children aged 3-36 months.

Kaiser Permanente implemented universal immunization with PCV13 in June 2010. “Initial trends through 2012 demonstrated continued decline in pneumococcal infections, with the biggest impact in children less than 5 years old,” wrote Tara Greenhow, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, San Francisco, and her colleagues.

Overall, the incidence of S. pneumoniae bacteremia declined from 74.5 per 100,000 children during the period before PCV7 (1998-1999) to 3.5 per 100,000 children during a period after routine use of PCV13 (2013-2014). The annual number of bacteremia cases from any cause dropped by 78% between these two time periods.

As bacteremia caused by pneumococci decreased, 77% of cases in the post-PCV13 time period were caused by Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., and Staphylococcus aureus. “A total of 76% of bacteremia occurred with a source, including 34% urinary tract infections, 17% gastroenteritis, 8% pneumonias, 8% osteomyelitis, 6% skin and soft tissue infections, and 3% other,” Dr. Greenhow and her associates reported.

The large population of the Kaiser Permanente system supports the accuracy of the now rare incidence of bacteremia in young children, the researchers noted. However, “because bacteremia in the post-PCV13 era is more likely to occur with a source, a focused examination should be performed and appropriate studies should be obtained at the time of a blood culture collection,” they said.

Routine use of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) reduced the incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia by 95% from a time period before to a time period after the vaccine was implemented, based on a review of more than 57,000 blood cultures from children aged 3-36 months.

Kaiser Permanente implemented universal immunization with PCV13 in June 2010. “Initial trends through 2012 demonstrated continued decline in pneumococcal infections, with the biggest impact in children less than 5 years old,” wrote Tara Greenhow, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, San Francisco, and her colleagues.

Overall, the incidence of S. pneumoniae bacteremia declined from 74.5 per 100,000 children during the period before PCV7 (1998-1999) to 3.5 per 100,000 children during a period after routine use of PCV13 (2013-2014). The annual number of bacteremia cases from any cause dropped by 78% between these two time periods.

As bacteremia caused by pneumococci decreased, 77% of cases in the post-PCV13 time period were caused by Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., and Staphylococcus aureus. “A total of 76% of bacteremia occurred with a source, including 34% urinary tract infections, 17% gastroenteritis, 8% pneumonias, 8% osteomyelitis, 6% skin and soft tissue infections, and 3% other,” Dr. Greenhow and her associates reported.

The large population of the Kaiser Permanente system supports the accuracy of the now rare incidence of bacteremia in young children, the researchers noted. However, “because bacteremia in the post-PCV13 era is more likely to occur with a source, a focused examination should be performed and appropriate studies should be obtained at the time of a blood culture collection,” they said.

Routine use of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) reduced the incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia by 95% from a time period before to a time period after the vaccine was implemented, based on a review of more than 57,000 blood cultures from children aged 3-36 months.

Kaiser Permanente implemented universal immunization with PCV13 in June 2010. “Initial trends through 2012 demonstrated continued decline in pneumococcal infections, with the biggest impact in children less than 5 years old,” wrote Tara Greenhow, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, San Francisco, and her colleagues.

Overall, the incidence of S. pneumoniae bacteremia declined from 74.5 per 100,000 children during the period before PCV7 (1998-1999) to 3.5 per 100,000 children during a period after routine use of PCV13 (2013-2014). The annual number of bacteremia cases from any cause dropped by 78% between these two time periods.

As bacteremia caused by pneumococci decreased, 77% of cases in the post-PCV13 time period were caused by Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., and Staphylococcus aureus. “A total of 76% of bacteremia occurred with a source, including 34% urinary tract infections, 17% gastroenteritis, 8% pneumonias, 8% osteomyelitis, 6% skin and soft tissue infections, and 3% other,” Dr. Greenhow and her associates reported.

The large population of the Kaiser Permanente system supports the accuracy of the now rare incidence of bacteremia in young children, the researchers noted. However, “because bacteremia in the post-PCV13 era is more likely to occur with a source, a focused examination should be performed and appropriate studies should be obtained at the time of a blood culture collection,” they said.

FROM PEDIATRICS

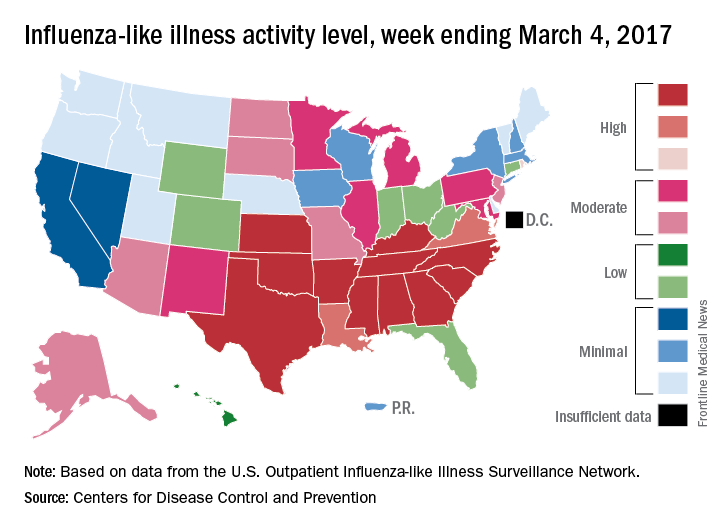

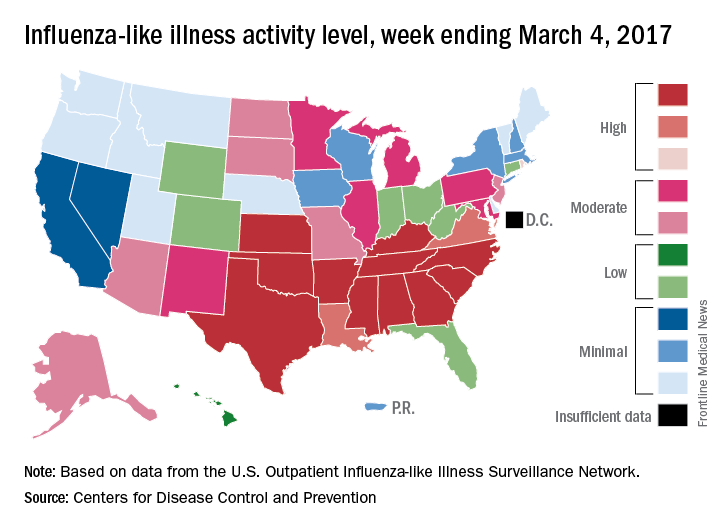

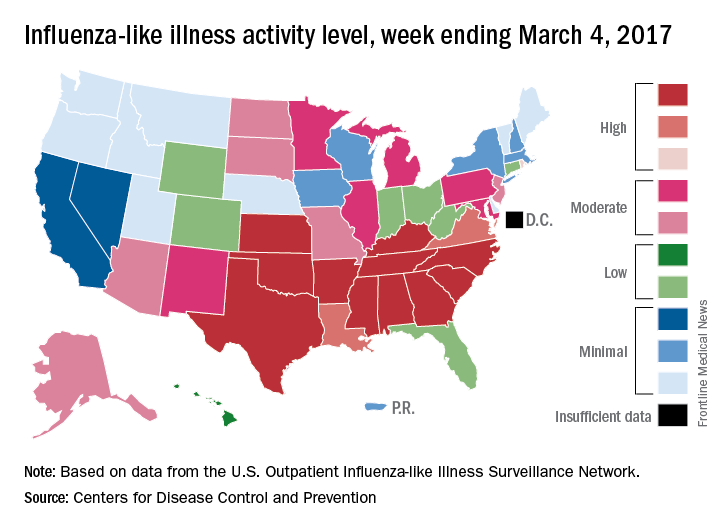

U.S. flu activity continues to decline

The 2016-2017 U.S. influenza season appears to have peaked, as activity measures dropped for the third consecutive week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

For the week ending March 4, there were 11 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, with another three in the “high” range at levels 8 and 9. The previous week (Feb. 25), there were 22 states at level 10, with a total of 27 in the high range of ILI activity. At the peak of activity during the week of Feb. 11, there were 25 states at level 10, data from the CDC’s Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network show.

There were eight ILI-related pediatric deaths reported during the week ending March 4, although all occurred in earlier weeks. For the 2016-2017 season so far, 48 ILI-related pediatric deaths have been reported, the CDC said.

For the 70 counties in 13 states that report to the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, the flu-related hospitalization rate for the season is 43.5 per 100,000 population. The highest rate by age group is for those 65 years and over at 198.8 per 100,000, followed by 50- to 64-year-olds at 42.2 per 100,000 and children aged 0-4 years at 28.8 per 100,000, according to the CDC.

The 2016-2017 U.S. influenza season appears to have peaked, as activity measures dropped for the third consecutive week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

For the week ending March 4, there were 11 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, with another three in the “high” range at levels 8 and 9. The previous week (Feb. 25), there were 22 states at level 10, with a total of 27 in the high range of ILI activity. At the peak of activity during the week of Feb. 11, there were 25 states at level 10, data from the CDC’s Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network show.

There were eight ILI-related pediatric deaths reported during the week ending March 4, although all occurred in earlier weeks. For the 2016-2017 season so far, 48 ILI-related pediatric deaths have been reported, the CDC said.

For the 70 counties in 13 states that report to the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, the flu-related hospitalization rate for the season is 43.5 per 100,000 population. The highest rate by age group is for those 65 years and over at 198.8 per 100,000, followed by 50- to 64-year-olds at 42.2 per 100,000 and children aged 0-4 years at 28.8 per 100,000, according to the CDC.

The 2016-2017 U.S. influenza season appears to have peaked, as activity measures dropped for the third consecutive week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

For the week ending March 4, there were 11 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, with another three in the “high” range at levels 8 and 9. The previous week (Feb. 25), there were 22 states at level 10, with a total of 27 in the high range of ILI activity. At the peak of activity during the week of Feb. 11, there were 25 states at level 10, data from the CDC’s Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network show.

There were eight ILI-related pediatric deaths reported during the week ending March 4, although all occurred in earlier weeks. For the 2016-2017 season so far, 48 ILI-related pediatric deaths have been reported, the CDC said.

For the 70 counties in 13 states that report to the Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network, the flu-related hospitalization rate for the season is 43.5 per 100,000 population. The highest rate by age group is for those 65 years and over at 198.8 per 100,000, followed by 50- to 64-year-olds at 42.2 per 100,000 and children aged 0-4 years at 28.8 per 100,000, according to the CDC.

CF patients live longer in Canada than in U.S.

People with cystic fibrosis (CF) survive an average of 10 years longer if they live in Canada than if they live in the United States, according to a report published online March 14 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Differences between the two nations’ health care systems, including access to insurance, “may, in part, explain the Canadian survival advantage,” said Anne L. Stephenson, MD, PhD, of St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, and her associates.

Overall there were 9,654 U.S. deaths and 1,288 Canadian deaths during the study period, for nearly identical overall mortality between the two countries (21.2% and 21.7%, respectively). However, the median survival was 10 years longer in Canada (50.9 years) than in the United States (40.6 years), a gap that persisted across numerous analyses that adjusted for patient characteristics and clinical factors, including CF severity.

One particular difference between the two study populations was found to be key: Canada has single-payer universal health insurance, while the United States does not. When U.S. patients were categorized according to their insurance status, Canadians had a 44% lower risk of death than did U.S. patients receiving continuous Medicaid or Medicare (95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.71; P less than .001), a 36% lower risk than for U.S. patients receiving intermittent Medicaid or Medicare (95% CI, 0.51-0.80; P = .002), and a 77% lower risk of death than U.S. patients with no or unknown health insurance (95% CI, 0.14-0.37; P less than .001), the investigators said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2017 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M16-0858). In contrast, there was no survival advantage for Canadian patients when compared with U.S. patients who had private health insurance. This “[raises] the question of whether a disparity exists in access to therapeutic approaches or health care delivery,” the researchers noted.

This study was supported by the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Cystic Fibrosis Canada, the National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Stephenson reported grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and fees from Cystic Fibrosis Canada. Several of the study’s other authors reported receiving fees from various sources and one of those authors reported serving on the boards of pharmaceutical companies.

Stephenson et al. confirmed that there is a “marked” [survival] “advantage” for CF patients in Canada, compared with those in the United States.

A key finding of this study was the survival difference between the two countries disappeared when U.S. patients insured by Medicaid or Medicare and those with no health insurance were excluded from the analysis. The fundamental differences between the two nations’ health care systems seem to be driving this disparity in survival.

Median predicted survival for all Canadians is higher than that of U.S. citizens, and this difference has increased over the last 2 decades.

Patrick A. Flume, MD, is at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Donald R. VanDevanter, PhD, is at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. They both reported ties to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Dr. Flume and Dr. VanDevanter made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Stephenson’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2017 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-0564).

Stephenson et al. confirmed that there is a “marked” [survival] “advantage” for CF patients in Canada, compared with those in the United States.

A key finding of this study was the survival difference between the two countries disappeared when U.S. patients insured by Medicaid or Medicare and those with no health insurance were excluded from the analysis. The fundamental differences between the two nations’ health care systems seem to be driving this disparity in survival.

Median predicted survival for all Canadians is higher than that of U.S. citizens, and this difference has increased over the last 2 decades.

Patrick A. Flume, MD, is at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Donald R. VanDevanter, PhD, is at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. They both reported ties to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Dr. Flume and Dr. VanDevanter made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Stephenson’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2017 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-0564).

Stephenson et al. confirmed that there is a “marked” [survival] “advantage” for CF patients in Canada, compared with those in the United States.

A key finding of this study was the survival difference between the two countries disappeared when U.S. patients insured by Medicaid or Medicare and those with no health insurance were excluded from the analysis. The fundamental differences between the two nations’ health care systems seem to be driving this disparity in survival.

Median predicted survival for all Canadians is higher than that of U.S. citizens, and this difference has increased over the last 2 decades.

Patrick A. Flume, MD, is at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Donald R. VanDevanter, PhD, is at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. They both reported ties to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Dr. Flume and Dr. VanDevanter made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Stephenson’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2017 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M17-0564).

People with cystic fibrosis (CF) survive an average of 10 years longer if they live in Canada than if they live in the United States, according to a report published online March 14 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Differences between the two nations’ health care systems, including access to insurance, “may, in part, explain the Canadian survival advantage,” said Anne L. Stephenson, MD, PhD, of St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, and her associates.

Overall there were 9,654 U.S. deaths and 1,288 Canadian deaths during the study period, for nearly identical overall mortality between the two countries (21.2% and 21.7%, respectively). However, the median survival was 10 years longer in Canada (50.9 years) than in the United States (40.6 years), a gap that persisted across numerous analyses that adjusted for patient characteristics and clinical factors, including CF severity.

One particular difference between the two study populations was found to be key: Canada has single-payer universal health insurance, while the United States does not. When U.S. patients were categorized according to their insurance status, Canadians had a 44% lower risk of death than did U.S. patients receiving continuous Medicaid or Medicare (95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.71; P less than .001), a 36% lower risk than for U.S. patients receiving intermittent Medicaid or Medicare (95% CI, 0.51-0.80; P = .002), and a 77% lower risk of death than U.S. patients with no or unknown health insurance (95% CI, 0.14-0.37; P less than .001), the investigators said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2017 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M16-0858). In contrast, there was no survival advantage for Canadian patients when compared with U.S. patients who had private health insurance. This “[raises] the question of whether a disparity exists in access to therapeutic approaches or health care delivery,” the researchers noted.

This study was supported by the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Cystic Fibrosis Canada, the National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Stephenson reported grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and fees from Cystic Fibrosis Canada. Several of the study’s other authors reported receiving fees from various sources and one of those authors reported serving on the boards of pharmaceutical companies.

People with cystic fibrosis (CF) survive an average of 10 years longer if they live in Canada than if they live in the United States, according to a report published online March 14 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Differences between the two nations’ health care systems, including access to insurance, “may, in part, explain the Canadian survival advantage,” said Anne L. Stephenson, MD, PhD, of St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, and her associates.

Overall there were 9,654 U.S. deaths and 1,288 Canadian deaths during the study period, for nearly identical overall mortality between the two countries (21.2% and 21.7%, respectively). However, the median survival was 10 years longer in Canada (50.9 years) than in the United States (40.6 years), a gap that persisted across numerous analyses that adjusted for patient characteristics and clinical factors, including CF severity.

One particular difference between the two study populations was found to be key: Canada has single-payer universal health insurance, while the United States does not. When U.S. patients were categorized according to their insurance status, Canadians had a 44% lower risk of death than did U.S. patients receiving continuous Medicaid or Medicare (95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.71; P less than .001), a 36% lower risk than for U.S. patients receiving intermittent Medicaid or Medicare (95% CI, 0.51-0.80; P = .002), and a 77% lower risk of death than U.S. patients with no or unknown health insurance (95% CI, 0.14-0.37; P less than .001), the investigators said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2017 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M16-0858). In contrast, there was no survival advantage for Canadian patients when compared with U.S. patients who had private health insurance. This “[raises] the question of whether a disparity exists in access to therapeutic approaches or health care delivery,” the researchers noted.

This study was supported by the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Cystic Fibrosis Canada, the National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Stephenson reported grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and fees from Cystic Fibrosis Canada. Several of the study’s other authors reported receiving fees from various sources and one of those authors reported serving on the boards of pharmaceutical companies.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: People with cystic fibrosis survive an average of 10 years longer if they live in Canada than if they live in the United States.

Major finding: Canadians with CF had a 44% lower risk of death than U.S. patients receiving Medicaid or Medicare and a striking 77% lower risk of death than U.S. patients with no health insurance, but the same risk as U.S. patients with private insurance.

Data source: A population-based cohort study involving 45,448 patients in a U.S. registry and 5,941 in a Canadian registry in 1990-2013.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the U.S. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Cystic Fibrosis Canada, the National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration. The authors’ financial disclosures are available at www.acponline.org

In children, peanut IgE levels increase over time

ATLANTA – Within a cohort of children diagnosed with peanut allergy who were followed since 2001, peanut IgE levels increased significantly over time in all races, according to a preliminary analysis of data.

In an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, lead study author Yasmin Hamzavi, MD, said that recent publications have implicated race as a factor in food sensitization, but how this may impact the management of food allergy has not been elucidated. “The novel aspect of this study is that we are not just looking at the baseline peanut IgE levels between the races, but at the rate of change in peanut IgE over time between the different races,” said Dr. Hamzavi, a fellow in the division of allergy and immunology at Northwell Health, Great Neck, N.Y. “My question was, does the level of peanut IgE decrease or increase faster in one race versus another?”

A significant increase in peanut IgE over time was observed among all races (P less than .0002). In addition, white and Asian children showed an increasing trend in peanut IgE, while black children demonstrated a decreasing trend over time (P less than .099), a finding that Dr. Hamzavi described as “surprising and unusual.” She called for larger studies exploring factors for the noted increase among all races, such as changes in testing methods, food avoidance, and increasing sensitization. “Understanding the changes in peanut sensitization over time is a crucial step in determining the likelihood of clinical reactivity,” she said.

Dr. Hamzavi is reviewing data for a similar analysis of children with milk and egg allergy. She reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Within a cohort of children diagnosed with peanut allergy who were followed since 2001, peanut IgE levels increased significantly over time in all races, according to a preliminary analysis of data.

In an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, lead study author Yasmin Hamzavi, MD, said that recent publications have implicated race as a factor in food sensitization, but how this may impact the management of food allergy has not been elucidated. “The novel aspect of this study is that we are not just looking at the baseline peanut IgE levels between the races, but at the rate of change in peanut IgE over time between the different races,” said Dr. Hamzavi, a fellow in the division of allergy and immunology at Northwell Health, Great Neck, N.Y. “My question was, does the level of peanut IgE decrease or increase faster in one race versus another?”

A significant increase in peanut IgE over time was observed among all races (P less than .0002). In addition, white and Asian children showed an increasing trend in peanut IgE, while black children demonstrated a decreasing trend over time (P less than .099), a finding that Dr. Hamzavi described as “surprising and unusual.” She called for larger studies exploring factors for the noted increase among all races, such as changes in testing methods, food avoidance, and increasing sensitization. “Understanding the changes in peanut sensitization over time is a crucial step in determining the likelihood of clinical reactivity,” she said.

Dr. Hamzavi is reviewing data for a similar analysis of children with milk and egg allergy. She reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Within a cohort of children diagnosed with peanut allergy who were followed since 2001, peanut IgE levels increased significantly over time in all races, according to a preliminary analysis of data.

In an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, lead study author Yasmin Hamzavi, MD, said that recent publications have implicated race as a factor in food sensitization, but how this may impact the management of food allergy has not been elucidated. “The novel aspect of this study is that we are not just looking at the baseline peanut IgE levels between the races, but at the rate of change in peanut IgE over time between the different races,” said Dr. Hamzavi, a fellow in the division of allergy and immunology at Northwell Health, Great Neck, N.Y. “My question was, does the level of peanut IgE decrease or increase faster in one race versus another?”

A significant increase in peanut IgE over time was observed among all races (P less than .0002). In addition, white and Asian children showed an increasing trend in peanut IgE, while black children demonstrated a decreasing trend over time (P less than .099), a finding that Dr. Hamzavi described as “surprising and unusual.” She called for larger studies exploring factors for the noted increase among all races, such as changes in testing methods, food avoidance, and increasing sensitization. “Understanding the changes in peanut sensitization over time is a crucial step in determining the likelihood of clinical reactivity,” she said.

Dr. Hamzavi is reviewing data for a similar analysis of children with milk and egg allergy. She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT 2017 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A significant increase in peanut IgE over time was observed among white, black, and Asian children (P less than .0002).

Data source: A retrospective review of 193 children diagnosed with peanut allergy .

Disclosures: Dr. Hamzavi reported having no financial disclosures.

FDA committee approves strains for 2017-2018 flu shot

ROCKVILLE, MD. – A committee of Food and Drug Administration advisers backed the World Health Organization’s influenza vaccine recommendations for the 2017-2018 season at a meeting March 9.

In a unanimous vote, members of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee recommended that trivalent vaccines for the 2017-2018 season should contain the following vaccine strains: A/Michigan/45/2015(H1N1)pdm09-like, A/Hong Kong/4801/2014(H3N2)-like, and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like.

These recommendations echo those from the 2016-2017 season, with the exception of a slight update to the H1N1 strain, which had previously been A/California/7/2009(H1N1)pdm09-like virus.

Regarding vaccine efficacy, the cell propagated A/Hong Kong strain was the strongest candidate, covering 93% of A(H3N2) viruses seen in the 2016-2017 season, according to Jacqueline Katz, PhD, director of the WHO Collaborating Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Control of Influenza at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In comparison, the egg propagated version of the A/Hong Kong virus covered 59%.

For the influenza B virus, the Yamagata lineage and Victoria lineage strain cycled monthly as the predominant strain in the 2016-2017 season, with a split of “around 50/50,” leaning toward Yamagata in North America, Europe, and Oceana, Dr. Katz explained. The Victoria lineage, in some cases, accounted for nearly 75% of B viruses in Africa and South America.

Committee members expressed concern over the difference between strain prevalence in the United States and abroad and considered recommending a strain that did not coincide with the WHO recommendation, something that has not happened in the history of the advisory committee.

“I’m very aware of influenza vaccinations being a global enterprise, and companies manufacture vaccines for use in multiple countries,” said Committee Chair Kathryn Edwards, MD, professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. “If we to select a B strain that differed from the WHO recommendation, would that adversely impact vaccine production for the U.S. market?”

Despite these questions, the committee continued to back the WHO recommendations.

Historically, the advisory committee has recommended flu vaccine strains earlier in the year, according to Beverly Taylor, PhD, head of influenza scientific affairs and pandemic readiness at Seqirus Vaccines. Dr. Taylor presented the vaccine manufacturers’ perspective. The delay has put added pressure on manufacturers.

“We haven’t seen impacts yet on start of vaccination dates,” said Dr. Taylor. “But the very clear message from manufacturers is if you keep squashing that manufacturing window, then there will reach a point where we are concerned we will see an impact on vaccine supply time.”

None of the committee members presented waivers of conflict of interest. While the FDA is not obligated to follow the recommendations of the advisory committee, it generally does.

[email protected]

On Twitter @EAZTweets

ROCKVILLE, MD. – A committee of Food and Drug Administration advisers backed the World Health Organization’s influenza vaccine recommendations for the 2017-2018 season at a meeting March 9.

In a unanimous vote, members of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee recommended that trivalent vaccines for the 2017-2018 season should contain the following vaccine strains: A/Michigan/45/2015(H1N1)pdm09-like, A/Hong Kong/4801/2014(H3N2)-like, and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like.

These recommendations echo those from the 2016-2017 season, with the exception of a slight update to the H1N1 strain, which had previously been A/California/7/2009(H1N1)pdm09-like virus.

Regarding vaccine efficacy, the cell propagated A/Hong Kong strain was the strongest candidate, covering 93% of A(H3N2) viruses seen in the 2016-2017 season, according to Jacqueline Katz, PhD, director of the WHO Collaborating Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Control of Influenza at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In comparison, the egg propagated version of the A/Hong Kong virus covered 59%.

For the influenza B virus, the Yamagata lineage and Victoria lineage strain cycled monthly as the predominant strain in the 2016-2017 season, with a split of “around 50/50,” leaning toward Yamagata in North America, Europe, and Oceana, Dr. Katz explained. The Victoria lineage, in some cases, accounted for nearly 75% of B viruses in Africa and South America.

Committee members expressed concern over the difference between strain prevalence in the United States and abroad and considered recommending a strain that did not coincide with the WHO recommendation, something that has not happened in the history of the advisory committee.

“I’m very aware of influenza vaccinations being a global enterprise, and companies manufacture vaccines for use in multiple countries,” said Committee Chair Kathryn Edwards, MD, professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. “If we to select a B strain that differed from the WHO recommendation, would that adversely impact vaccine production for the U.S. market?”

Despite these questions, the committee continued to back the WHO recommendations.

Historically, the advisory committee has recommended flu vaccine strains earlier in the year, according to Beverly Taylor, PhD, head of influenza scientific affairs and pandemic readiness at Seqirus Vaccines. Dr. Taylor presented the vaccine manufacturers’ perspective. The delay has put added pressure on manufacturers.

“We haven’t seen impacts yet on start of vaccination dates,” said Dr. Taylor. “But the very clear message from manufacturers is if you keep squashing that manufacturing window, then there will reach a point where we are concerned we will see an impact on vaccine supply time.”

None of the committee members presented waivers of conflict of interest. While the FDA is not obligated to follow the recommendations of the advisory committee, it generally does.

[email protected]

On Twitter @EAZTweets

ROCKVILLE, MD. – A committee of Food and Drug Administration advisers backed the World Health Organization’s influenza vaccine recommendations for the 2017-2018 season at a meeting March 9.

In a unanimous vote, members of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee recommended that trivalent vaccines for the 2017-2018 season should contain the following vaccine strains: A/Michigan/45/2015(H1N1)pdm09-like, A/Hong Kong/4801/2014(H3N2)-like, and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like.

These recommendations echo those from the 2016-2017 season, with the exception of a slight update to the H1N1 strain, which had previously been A/California/7/2009(H1N1)pdm09-like virus.

Regarding vaccine efficacy, the cell propagated A/Hong Kong strain was the strongest candidate, covering 93% of A(H3N2) viruses seen in the 2016-2017 season, according to Jacqueline Katz, PhD, director of the WHO Collaborating Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Control of Influenza at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In comparison, the egg propagated version of the A/Hong Kong virus covered 59%.

For the influenza B virus, the Yamagata lineage and Victoria lineage strain cycled monthly as the predominant strain in the 2016-2017 season, with a split of “around 50/50,” leaning toward Yamagata in North America, Europe, and Oceana, Dr. Katz explained. The Victoria lineage, in some cases, accounted for nearly 75% of B viruses in Africa and South America.

Committee members expressed concern over the difference between strain prevalence in the United States and abroad and considered recommending a strain that did not coincide with the WHO recommendation, something that has not happened in the history of the advisory committee.

“I’m very aware of influenza vaccinations being a global enterprise, and companies manufacture vaccines for use in multiple countries,” said Committee Chair Kathryn Edwards, MD, professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. “If we to select a B strain that differed from the WHO recommendation, would that adversely impact vaccine production for the U.S. market?”

Despite these questions, the committee continued to back the WHO recommendations.

Historically, the advisory committee has recommended flu vaccine strains earlier in the year, according to Beverly Taylor, PhD, head of influenza scientific affairs and pandemic readiness at Seqirus Vaccines. Dr. Taylor presented the vaccine manufacturers’ perspective. The delay has put added pressure on manufacturers.

“We haven’t seen impacts yet on start of vaccination dates,” said Dr. Taylor. “But the very clear message from manufacturers is if you keep squashing that manufacturing window, then there will reach a point where we are concerned we will see an impact on vaccine supply time.”

None of the committee members presented waivers of conflict of interest. While the FDA is not obligated to follow the recommendations of the advisory committee, it generally does.

[email protected]

On Twitter @EAZTweets

AT AN FDA ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING

Hospitals rarely offer cessation therapy to smokers with MI

according to a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Inpatient smoking cessation therapy coupled with outpatient follow-up can significantly improve long-term smoking cessation rates, but little is known about how often smoking cessation therapies are used among hospitalized patients,” wrote Dr Quinn R. Pack and coauthors from the Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, and Massachusetts General Hospital.

The nicotine patch was the most common therapy; 20.4% of patients received it with an average daily dose of 19.8 mg, while 2.2% of patients received bupropion, 0.4% received varenicline, 0.3% received nicotine gum, 0.2% received nicotine inhaler therapy, and just 0.04% received nicotine lozenge therapy. Nearly one in ten patients received professional counseling (9.6%).

Smoking cessation was more commonly given to patients with lung disease, depression, alcohol use or who were younger but the researchers noted significant variations in the use of smoking cessation therapies across hospitals. While the median treatment rate was 26.2%, it ranged from as low as 11.4% to a high of 51.1%.

Given the variation across hospitals, the authors said they plan to identify the strategies and practices that the high-performing hospitals use to provide smoking cessation therapies.

“Smoking cessation is the single most effective behavior change that patients can make after a hospitalization for coronary heart disease to prevent recurrent events,” the authors wrote. “Given that hospitalization is usually a teachable moment with high patient motivation to quit smoking, there appears to be a large opportunity for improvement in the care of smokers hospitalized with CHD.”

The authors noted that their data were limited to smoking cessation options provided during hospitalization; the researchers said they did not assess whether those therapies helped MI patients quit smoking, or whether there were patients who declined the therapies offered.

No conflict of interest disclosures were provided with the data.

according to a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Inpatient smoking cessation therapy coupled with outpatient follow-up can significantly improve long-term smoking cessation rates, but little is known about how often smoking cessation therapies are used among hospitalized patients,” wrote Dr Quinn R. Pack and coauthors from the Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, and Massachusetts General Hospital.

The nicotine patch was the most common therapy; 20.4% of patients received it with an average daily dose of 19.8 mg, while 2.2% of patients received bupropion, 0.4% received varenicline, 0.3% received nicotine gum, 0.2% received nicotine inhaler therapy, and just 0.04% received nicotine lozenge therapy. Nearly one in ten patients received professional counseling (9.6%).

Smoking cessation was more commonly given to patients with lung disease, depression, alcohol use or who were younger but the researchers noted significant variations in the use of smoking cessation therapies across hospitals. While the median treatment rate was 26.2%, it ranged from as low as 11.4% to a high of 51.1%.

Given the variation across hospitals, the authors said they plan to identify the strategies and practices that the high-performing hospitals use to provide smoking cessation therapies.

“Smoking cessation is the single most effective behavior change that patients can make after a hospitalization for coronary heart disease to prevent recurrent events,” the authors wrote. “Given that hospitalization is usually a teachable moment with high patient motivation to quit smoking, there appears to be a large opportunity for improvement in the care of smokers hospitalized with CHD.”

The authors noted that their data were limited to smoking cessation options provided during hospitalization; the researchers said they did not assess whether those therapies helped MI patients quit smoking, or whether there were patients who declined the therapies offered.

No conflict of interest disclosures were provided with the data.

according to a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Inpatient smoking cessation therapy coupled with outpatient follow-up can significantly improve long-term smoking cessation rates, but little is known about how often smoking cessation therapies are used among hospitalized patients,” wrote Dr Quinn R. Pack and coauthors from the Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, and Massachusetts General Hospital.

The nicotine patch was the most common therapy; 20.4% of patients received it with an average daily dose of 19.8 mg, while 2.2% of patients received bupropion, 0.4% received varenicline, 0.3% received nicotine gum, 0.2% received nicotine inhaler therapy, and just 0.04% received nicotine lozenge therapy. Nearly one in ten patients received professional counseling (9.6%).

Smoking cessation was more commonly given to patients with lung disease, depression, alcohol use or who were younger but the researchers noted significant variations in the use of smoking cessation therapies across hospitals. While the median treatment rate was 26.2%, it ranged from as low as 11.4% to a high of 51.1%.

Given the variation across hospitals, the authors said they plan to identify the strategies and practices that the high-performing hospitals use to provide smoking cessation therapies.

“Smoking cessation is the single most effective behavior change that patients can make after a hospitalization for coronary heart disease to prevent recurrent events,” the authors wrote. “Given that hospitalization is usually a teachable moment with high patient motivation to quit smoking, there appears to be a large opportunity for improvement in the care of smokers hospitalized with CHD.”

The authors noted that their data were limited to smoking cessation options provided during hospitalization; the researchers said they did not assess whether those therapies helped MI patients quit smoking, or whether there were patients who declined the therapies offered.

No conflict of interest disclosures were provided with the data.

FROM ACC 17

Key clinical point: Less than one-third of smokers hospitalized for myocardial infarction receive any kind of smoking cessation therapy during their stay in hospital.

Major finding: Only 29.9% of current smokers hospitalized for MI were given at least one kind of smoking cessation therapy while in hospital.

Data source: Cohort study of billing and ICD-9 data from 36,675 current smokers hospitalized for myocardial infarction.

Disclosures: No disclosures were available.

Corticosteroids reduce risks in elective extubation

Prophylactic corticosteroids before elective extubation could significantly reduce postextubation stridor and the incidence of reintubation, particularly in patients at high risk of airway obstruction, suggests a systematic review and meta-analysis.

While current guidelines for the management of tracheal extubation call for prophylactic use of corticosteroids in patients with airway compromise, Akira Kuriyama, MD, of Kurashiki Central Hospital in Japan, and coauthors noted that there is an outstanding question as to which patients are most likely to benefit.

Writing in the February 20 online edition of Chest, they reported on an analysis of 11 randomized, controlled trials of prophylactic corticosteroids given before elective extubation, involving 2,472 participants (Chest 2017 Feb 20. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.017).

They found that the use of prophylactic corticosteroids was associated with a significant 57% reduction in the incidence of postextubation airway obstruction, laryngeal edema, or stridor, and a 58% reduction in reintubation rates, compared with placebo or no treatment.

A subgroup analysis showed that the benefit in reduction of postextubation airway events was evident only in the six trials that selected patients at high risk of airway obstruction, identified by a cuff-leak test (RR = 0.34), and was not seen in trials with an unselected patient population. Similarly, the reduced incidence of reintubation was evident in trials of high-risk individuals (RR = 0.35) but not in the general patient population.

The authors noted that while the latest systematic reviews had shown that corticosteroids reduce the incidence of postextubation stridor and reintubation, only one review examined the efficacy in high-risk populations and even then, it was a pooled subgroup analysis of only three trials.

“The numbers needed to prevent one episode of postextubation airway events and reintubation in individuals at high risk for postextubation airway obstruction were 5 (95%; CI: 4-7) and 16 (95%; CI: 8-166) respectively,” they wrote, noting that routine administration of corticosteroids before elective extubation is not recommended.

“While the use of prophylactic corticosteroids was associated with few adverse events, it is reasonable to use the cuff-leak test as a screening method, and administer prophylactic steroids only to those who are at risk of developing postextubation obstruction, given our study findings.”

Two of the six trials that identified high-risk individuals used a cuff-leak volume less than 24% of tidal volume during inflation, three used a cuff-leak volume of less than 110 mL, and one used a cuff-leak volume less than 25% of tidal volume.

“This potentially indicates that cuff-leak testing, while applied with varying cut-off values, might be able to select those at similar risk for airway obstruction and underlines the importance of screening for high-risk patients,” the authors said.

Researchers also noted that the longer patients were intubated, the lower the effect size of prophylactic corticosteroids on both postexutubation airway events and reintubation.

“Patients thus tended to benefit from prophylactic corticosteroids to prevent postextubation airway events and subsequent reintubation when the duration of mechanical ventilation was short,” they wrote.

The authors noted that the included trials did differ in terms of populations, corticosteroid protocols, and observation periods. However, they pointed out that the statistical heterogeneity in their primary outcome analysis was due to the risk of postextubation airway obstruction.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Prophylactic corticosteroids before elective extubation could significantly reduce postextubation stridor and the incidence of reintubation, particularly in patients at high risk of airway obstruction, suggests a systematic review and meta-analysis.

While current guidelines for the management of tracheal extubation call for prophylactic use of corticosteroids in patients with airway compromise, Akira Kuriyama, MD, of Kurashiki Central Hospital in Japan, and coauthors noted that there is an outstanding question as to which patients are most likely to benefit.

Writing in the February 20 online edition of Chest, they reported on an analysis of 11 randomized, controlled trials of prophylactic corticosteroids given before elective extubation, involving 2,472 participants (Chest 2017 Feb 20. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.017).

They found that the use of prophylactic corticosteroids was associated with a significant 57% reduction in the incidence of postextubation airway obstruction, laryngeal edema, or stridor, and a 58% reduction in reintubation rates, compared with placebo or no treatment.

A subgroup analysis showed that the benefit in reduction of postextubation airway events was evident only in the six trials that selected patients at high risk of airway obstruction, identified by a cuff-leak test (RR = 0.34), and was not seen in trials with an unselected patient population. Similarly, the reduced incidence of reintubation was evident in trials of high-risk individuals (RR = 0.35) but not in the general patient population.

The authors noted that while the latest systematic reviews had shown that corticosteroids reduce the incidence of postextubation stridor and reintubation, only one review examined the efficacy in high-risk populations and even then, it was a pooled subgroup analysis of only three trials.

“The numbers needed to prevent one episode of postextubation airway events and reintubation in individuals at high risk for postextubation airway obstruction were 5 (95%; CI: 4-7) and 16 (95%; CI: 8-166) respectively,” they wrote, noting that routine administration of corticosteroids before elective extubation is not recommended.

“While the use of prophylactic corticosteroids was associated with few adverse events, it is reasonable to use the cuff-leak test as a screening method, and administer prophylactic steroids only to those who are at risk of developing postextubation obstruction, given our study findings.”

Two of the six trials that identified high-risk individuals used a cuff-leak volume less than 24% of tidal volume during inflation, three used a cuff-leak volume of less than 110 mL, and one used a cuff-leak volume less than 25% of tidal volume.

“This potentially indicates that cuff-leak testing, while applied with varying cut-off values, might be able to select those at similar risk for airway obstruction and underlines the importance of screening for high-risk patients,” the authors said.

Researchers also noted that the longer patients were intubated, the lower the effect size of prophylactic corticosteroids on both postexutubation airway events and reintubation.