User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Medicaid to cover routine costs for patients in trials

A boost for patients with cancer and other serious illnesses.

Congress has ordered the holdouts among U.S. states to have their Medicaid programs cover expenses related to participation in certain clinical trials, a move that was hailed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and other groups as a boost to trials as well as to patients with serious illness who have lower incomes.

A massive wrap-up spending/COVID-19 relief bill that was signed into law Dec. 27 carried with it a mandate on Medicaid. States are ordered to put in place Medicaid payment policies for routine items and services, such as the cost of physician visits or laboratory tests, that are provided in connection with participation in clinical trials for serious and life-threatening conditions. The law includes a January 2022 target date for this coverage through Medicaid.

Medicare and other large insurers already pick up the tab for these kinds of expenses, leaving Medicaid as an outlier, ASCO noted in a press statement. ASCO and other cancer groups have for years pressed Medicaid to cover routine expenses for people participating in clinical trials. Already, 15 states, including California, require their Medicaid programs to cover these expenses, according to ASCO.

“We believe that the trials can bring extra benefits to patients,” said Monica M. Bertagnolli, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston. Dr. Bertagnolli has worked for years to secure Medicaid coverage for expenses connected to clinical trials.

Although Medicaid covers costs of standard care for cancer patients, people enrolled in the program may have concerns about participating in clinical studies, said Dr. Bertagnolli, chair of the Association for Clinical Oncology, which was established by ASCO to promote wider access to cancer care. Having extra medical expenses may be more than these patients can tolerate.

“Many of them just say, ‘I can’t take that financial risk, so I’ll just stay with standard of care,’ “ Dr. Bertagnolli said in an interview.

Equity issues

Medicaid has expanded greatly, owing to financial aid provided to states through the Affordable Care Act of 2010.

To date, 38 of 50 U.S. states have accepted federal aid to lift income limits for Medicaid eligibility, according to a tally kept by the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. This Medicaid expansion has given more of the nation’s working poor access to health.care, including cancer treatment. Between 2013 and January 2020, enrollment in Medicaid in expansion states increased by about 12.4 million, according to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.

Medicaid is the nation’s dominant health insurer. Enrollment has been around 70 million in recent months.

That tops the 61 million enrolled in Medicare, the federal program for people aged 65 and older and those with disabilities. (There’s some overlap between Medicare and Medicaid. About 12.8 million persons were dually eligible for these programs in 2018.) UnitedHealth, a giant private insurer, has about 43 million domestic customers.

Medicaid also serves many of the groups of people for which researchers have been seeking to increase participation in clinical trials. ASCO’s Association for Clinical Oncology and dozens of its partners raised this point in a letter to congressional leaders on Feb. 15, 2020.

“Lack of participation in clinical trials from the Medicaid population means these patients are being excluded from potentially life-saving trials and are not reflected in the outcome of the clinical research,” the groups wrote. “Increased access to clinical trial participation for Medicaid enrollees helps ensure medical research results more accurately capture and reflect the populations of this country.”

The ACA’s Medicaid expansion is working to address some of the racial gaps in insurance coverage, according to a January 2020 report from the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund.

Black and Hispanic adults are almost twice as likely as are White adults to have incomes that are less than 200% of the federal poverty level, according to the Commonwealth Fund report. The report also said that people in these groups reported significantly higher rates of cost-related problems in receiving care before the Medicaid expansion began in 2014.

The uninsured rate for Black adults dropped from 24.4% in 2013 to 14.4% in 2018; the rate for Hispanic adults fell from 40.2% to 24.9%, according to the Commonwealth Fund report.

There are concerns, though, about attempts by some governors to impose onerous restrictions on adults enrolled in Medicaid, Dr. Bertagnolli said. She was president of ASCO in 2018 when the group called on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reject state requests to create restrictions that could hinder people’s access to cancer screening or care.

The Trump administration encouraged governors to adopt work requirements. As a result, a dozen states approved these policies, according to a November report from the nonprofit Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The efforts were blocked by courts.

Data from the limited period of implementation in Arkansas, Michigan, and New Hampshire provide evidence that these kinds of requirements don’t work as intended, according to the CBPP report.

“In all three states, evidence suggests that people who were working and people with serious health needs who should have been eligible for exemptions lost coverage or were at risk of losing coverage due to red tape,” CBPP analysts Jennifer Wagner and Jessica Schubel wrote in their report.

In 2019, The New England Journal of Medicine published an article about the early stages of the Arkansas experiment with Medicaid work rules. Almost 17,000 adults lost their health care coverage in the initial months of implementation, but there appeared to be no significant difference in employment, Benjamin Sommers, MD, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their article.

For many people in Arkansas, coverage was lost because of difficulties in reporting compliance with the Medicaid work rule, not because of the employment mandate itself, according to the authors. More than 95% of persons who were targeted by Arkansas’ Medicaid work policy already met its requirements or should have been exempt, they wrote.

Democrats have tended to oppose efforts to attach work requirements, which can include volunteer activities or career training, to Medicaid. Dr. Bertagnolli said there is a need to guard against any future bid to add work requirements to the program.

Extra bureaucratic hurdles may pose an especially tough burden on working adults enrolled in Medicaid, she said.

People who qualify for the program may already be worried about their finances while juggling continued demands of child care and employment, she said. They don’t need to be put at risk of losing access to medical care over administrative rules while undergoing cancer treatment, she said.

“We have to take care of people who are sick. That’s just the way it is,” Dr. Bertagnolli said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A boost for patients with cancer and other serious illnesses.

A boost for patients with cancer and other serious illnesses.

Congress has ordered the holdouts among U.S. states to have their Medicaid programs cover expenses related to participation in certain clinical trials, a move that was hailed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and other groups as a boost to trials as well as to patients with serious illness who have lower incomes.

A massive wrap-up spending/COVID-19 relief bill that was signed into law Dec. 27 carried with it a mandate on Medicaid. States are ordered to put in place Medicaid payment policies for routine items and services, such as the cost of physician visits or laboratory tests, that are provided in connection with participation in clinical trials for serious and life-threatening conditions. The law includes a January 2022 target date for this coverage through Medicaid.

Medicare and other large insurers already pick up the tab for these kinds of expenses, leaving Medicaid as an outlier, ASCO noted in a press statement. ASCO and other cancer groups have for years pressed Medicaid to cover routine expenses for people participating in clinical trials. Already, 15 states, including California, require their Medicaid programs to cover these expenses, according to ASCO.

“We believe that the trials can bring extra benefits to patients,” said Monica M. Bertagnolli, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston. Dr. Bertagnolli has worked for years to secure Medicaid coverage for expenses connected to clinical trials.

Although Medicaid covers costs of standard care for cancer patients, people enrolled in the program may have concerns about participating in clinical studies, said Dr. Bertagnolli, chair of the Association for Clinical Oncology, which was established by ASCO to promote wider access to cancer care. Having extra medical expenses may be more than these patients can tolerate.

“Many of them just say, ‘I can’t take that financial risk, so I’ll just stay with standard of care,’ “ Dr. Bertagnolli said in an interview.

Equity issues

Medicaid has expanded greatly, owing to financial aid provided to states through the Affordable Care Act of 2010.

To date, 38 of 50 U.S. states have accepted federal aid to lift income limits for Medicaid eligibility, according to a tally kept by the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. This Medicaid expansion has given more of the nation’s working poor access to health.care, including cancer treatment. Between 2013 and January 2020, enrollment in Medicaid in expansion states increased by about 12.4 million, according to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.

Medicaid is the nation’s dominant health insurer. Enrollment has been around 70 million in recent months.

That tops the 61 million enrolled in Medicare, the federal program for people aged 65 and older and those with disabilities. (There’s some overlap between Medicare and Medicaid. About 12.8 million persons were dually eligible for these programs in 2018.) UnitedHealth, a giant private insurer, has about 43 million domestic customers.

Medicaid also serves many of the groups of people for which researchers have been seeking to increase participation in clinical trials. ASCO’s Association for Clinical Oncology and dozens of its partners raised this point in a letter to congressional leaders on Feb. 15, 2020.

“Lack of participation in clinical trials from the Medicaid population means these patients are being excluded from potentially life-saving trials and are not reflected in the outcome of the clinical research,” the groups wrote. “Increased access to clinical trial participation for Medicaid enrollees helps ensure medical research results more accurately capture and reflect the populations of this country.”

The ACA’s Medicaid expansion is working to address some of the racial gaps in insurance coverage, according to a January 2020 report from the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund.

Black and Hispanic adults are almost twice as likely as are White adults to have incomes that are less than 200% of the federal poverty level, according to the Commonwealth Fund report. The report also said that people in these groups reported significantly higher rates of cost-related problems in receiving care before the Medicaid expansion began in 2014.

The uninsured rate for Black adults dropped from 24.4% in 2013 to 14.4% in 2018; the rate for Hispanic adults fell from 40.2% to 24.9%, according to the Commonwealth Fund report.

There are concerns, though, about attempts by some governors to impose onerous restrictions on adults enrolled in Medicaid, Dr. Bertagnolli said. She was president of ASCO in 2018 when the group called on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reject state requests to create restrictions that could hinder people’s access to cancer screening or care.

The Trump administration encouraged governors to adopt work requirements. As a result, a dozen states approved these policies, according to a November report from the nonprofit Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The efforts were blocked by courts.

Data from the limited period of implementation in Arkansas, Michigan, and New Hampshire provide evidence that these kinds of requirements don’t work as intended, according to the CBPP report.

“In all three states, evidence suggests that people who were working and people with serious health needs who should have been eligible for exemptions lost coverage or were at risk of losing coverage due to red tape,” CBPP analysts Jennifer Wagner and Jessica Schubel wrote in their report.

In 2019, The New England Journal of Medicine published an article about the early stages of the Arkansas experiment with Medicaid work rules. Almost 17,000 adults lost their health care coverage in the initial months of implementation, but there appeared to be no significant difference in employment, Benjamin Sommers, MD, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their article.

For many people in Arkansas, coverage was lost because of difficulties in reporting compliance with the Medicaid work rule, not because of the employment mandate itself, according to the authors. More than 95% of persons who were targeted by Arkansas’ Medicaid work policy already met its requirements or should have been exempt, they wrote.

Democrats have tended to oppose efforts to attach work requirements, which can include volunteer activities or career training, to Medicaid. Dr. Bertagnolli said there is a need to guard against any future bid to add work requirements to the program.

Extra bureaucratic hurdles may pose an especially tough burden on working adults enrolled in Medicaid, she said.

People who qualify for the program may already be worried about their finances while juggling continued demands of child care and employment, she said. They don’t need to be put at risk of losing access to medical care over administrative rules while undergoing cancer treatment, she said.

“We have to take care of people who are sick. That’s just the way it is,” Dr. Bertagnolli said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Congress has ordered the holdouts among U.S. states to have their Medicaid programs cover expenses related to participation in certain clinical trials, a move that was hailed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and other groups as a boost to trials as well as to patients with serious illness who have lower incomes.

A massive wrap-up spending/COVID-19 relief bill that was signed into law Dec. 27 carried with it a mandate on Medicaid. States are ordered to put in place Medicaid payment policies for routine items and services, such as the cost of physician visits or laboratory tests, that are provided in connection with participation in clinical trials for serious and life-threatening conditions. The law includes a January 2022 target date for this coverage through Medicaid.

Medicare and other large insurers already pick up the tab for these kinds of expenses, leaving Medicaid as an outlier, ASCO noted in a press statement. ASCO and other cancer groups have for years pressed Medicaid to cover routine expenses for people participating in clinical trials. Already, 15 states, including California, require their Medicaid programs to cover these expenses, according to ASCO.

“We believe that the trials can bring extra benefits to patients,” said Monica M. Bertagnolli, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston. Dr. Bertagnolli has worked for years to secure Medicaid coverage for expenses connected to clinical trials.

Although Medicaid covers costs of standard care for cancer patients, people enrolled in the program may have concerns about participating in clinical studies, said Dr. Bertagnolli, chair of the Association for Clinical Oncology, which was established by ASCO to promote wider access to cancer care. Having extra medical expenses may be more than these patients can tolerate.

“Many of them just say, ‘I can’t take that financial risk, so I’ll just stay with standard of care,’ “ Dr. Bertagnolli said in an interview.

Equity issues

Medicaid has expanded greatly, owing to financial aid provided to states through the Affordable Care Act of 2010.

To date, 38 of 50 U.S. states have accepted federal aid to lift income limits for Medicaid eligibility, according to a tally kept by the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. This Medicaid expansion has given more of the nation’s working poor access to health.care, including cancer treatment. Between 2013 and January 2020, enrollment in Medicaid in expansion states increased by about 12.4 million, according to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.

Medicaid is the nation’s dominant health insurer. Enrollment has been around 70 million in recent months.

That tops the 61 million enrolled in Medicare, the federal program for people aged 65 and older and those with disabilities. (There’s some overlap between Medicare and Medicaid. About 12.8 million persons were dually eligible for these programs in 2018.) UnitedHealth, a giant private insurer, has about 43 million domestic customers.

Medicaid also serves many of the groups of people for which researchers have been seeking to increase participation in clinical trials. ASCO’s Association for Clinical Oncology and dozens of its partners raised this point in a letter to congressional leaders on Feb. 15, 2020.

“Lack of participation in clinical trials from the Medicaid population means these patients are being excluded from potentially life-saving trials and are not reflected in the outcome of the clinical research,” the groups wrote. “Increased access to clinical trial participation for Medicaid enrollees helps ensure medical research results more accurately capture and reflect the populations of this country.”

The ACA’s Medicaid expansion is working to address some of the racial gaps in insurance coverage, according to a January 2020 report from the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund.

Black and Hispanic adults are almost twice as likely as are White adults to have incomes that are less than 200% of the federal poverty level, according to the Commonwealth Fund report. The report also said that people in these groups reported significantly higher rates of cost-related problems in receiving care before the Medicaid expansion began in 2014.

The uninsured rate for Black adults dropped from 24.4% in 2013 to 14.4% in 2018; the rate for Hispanic adults fell from 40.2% to 24.9%, according to the Commonwealth Fund report.

There are concerns, though, about attempts by some governors to impose onerous restrictions on adults enrolled in Medicaid, Dr. Bertagnolli said. She was president of ASCO in 2018 when the group called on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reject state requests to create restrictions that could hinder people’s access to cancer screening or care.

The Trump administration encouraged governors to adopt work requirements. As a result, a dozen states approved these policies, according to a November report from the nonprofit Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The efforts were blocked by courts.

Data from the limited period of implementation in Arkansas, Michigan, and New Hampshire provide evidence that these kinds of requirements don’t work as intended, according to the CBPP report.

“In all three states, evidence suggests that people who were working and people with serious health needs who should have been eligible for exemptions lost coverage or were at risk of losing coverage due to red tape,” CBPP analysts Jennifer Wagner and Jessica Schubel wrote in their report.

In 2019, The New England Journal of Medicine published an article about the early stages of the Arkansas experiment with Medicaid work rules. Almost 17,000 adults lost their health care coverage in the initial months of implementation, but there appeared to be no significant difference in employment, Benjamin Sommers, MD, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and colleagues wrote in their article.

For many people in Arkansas, coverage was lost because of difficulties in reporting compliance with the Medicaid work rule, not because of the employment mandate itself, according to the authors. More than 95% of persons who were targeted by Arkansas’ Medicaid work policy already met its requirements or should have been exempt, they wrote.

Democrats have tended to oppose efforts to attach work requirements, which can include volunteer activities or career training, to Medicaid. Dr. Bertagnolli said there is a need to guard against any future bid to add work requirements to the program.

Extra bureaucratic hurdles may pose an especially tough burden on working adults enrolled in Medicaid, she said.

People who qualify for the program may already be worried about their finances while juggling continued demands of child care and employment, she said. They don’t need to be put at risk of losing access to medical care over administrative rules while undergoing cancer treatment, she said.

“We have to take care of people who are sick. That’s just the way it is,” Dr. Bertagnolli said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Hidden’ danger of type 2 diabetes diagnosis at early age

Those who are found to have type 2 diabetes at a younger age face “hidden” dangers. The issue is becoming more and more important, “since new diagnoses in this younger age group continue to rise,” said the authors of a new study, led by Natalie Nanayakkara, MD.

They believe clinical approaches should be based on age at diagnosis. The results of their new meta-analysis, published online in Diabetologia, reveal the extent of the problem.

Believed to be the first systematic review of its kind, the study showed that the younger the age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, the greater the risks of dying and of having either microvascular or macrovascular complications each subsequent year (adjusted for current age).

“This difference in risk between younger and older people in terms of absolute versus lifetime risks of type 2 diabetes complications should perhaps be recognized in diabetes management guidelines,” wrote Dr. Nanayakkara, an endocrinologist at Monash University, Melbourne, and colleagues.

Those diagnosed at younger ages are more likely to develop complications that cause greater disability and lead to loss of productivity compared with people diagnosed at an older age, they stressed.

Hence, they suggested “a greater emphasis on preventive measures for younger people with type 2 diabetes,” with “early intensive multifactorial risk factor intervention ... sustained long term to minimize risks over time.”

Large dataset: Use age at diagnosis to risk stratify patients

Rates of type 2 diabetes have increased in all age groups and virtually all countries over the past 3 decades. Particularly worrying is a trend toward increased rates among adults aged 20-44 years. The increases are associated with higher rates of overweight and obesity, poor diet, and decreasing levels of physical activity, numerous studies have shown.

But few studies have examined the association between age at diagnosis and subsequent complications from type 2 diabetes, the authors noted.

Their review included 26 observational studies involving more than one million individuals from 30 countries in the Asia Pacific, Europe, and North America. The investigators found that each 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis was significantly associated with a 4%, 3%, and 5% decreased risk for all-cause mortality, macrovascular disease, and microvascular disease, respectively, adjusted for current age (all P < .001).

Similar decreases in risk per 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis were seen for coronary heart disease (2%), cerebrovascular disease (2%), peripheral vascular disease (3%), retinopathy (8%), nephropathy (6%), and neuropathy (5%); all associations were significant (P < .001).

Dr. Nanayakkara and colleagues noted that current treatment guidelines are limited in that they’re related to the management of patients with suboptimal blood glucose control, and there is no way to predict which people require intensified treatment.

Therefore, they said, “refined stratification using age at diagnosis may provide a method of identifying, at diagnosis, those at greatest risk of complications who would most benefit from targeted, individualized treatment regimens.”

Awareness of this “hidden” danger to younger adults with type 2 diabetes is becoming more and more important, because such cases continue to rise, they reiterated.

They also advised that “public health measures to delay and/or prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes until older age may yield benefits by reducing the duration of diabetes and the burden of complications.”

Dr. Nanayakkara disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Those who are found to have type 2 diabetes at a younger age face “hidden” dangers. The issue is becoming more and more important, “since new diagnoses in this younger age group continue to rise,” said the authors of a new study, led by Natalie Nanayakkara, MD.

They believe clinical approaches should be based on age at diagnosis. The results of their new meta-analysis, published online in Diabetologia, reveal the extent of the problem.

Believed to be the first systematic review of its kind, the study showed that the younger the age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, the greater the risks of dying and of having either microvascular or macrovascular complications each subsequent year (adjusted for current age).

“This difference in risk between younger and older people in terms of absolute versus lifetime risks of type 2 diabetes complications should perhaps be recognized in diabetes management guidelines,” wrote Dr. Nanayakkara, an endocrinologist at Monash University, Melbourne, and colleagues.

Those diagnosed at younger ages are more likely to develop complications that cause greater disability and lead to loss of productivity compared with people diagnosed at an older age, they stressed.

Hence, they suggested “a greater emphasis on preventive measures for younger people with type 2 diabetes,” with “early intensive multifactorial risk factor intervention ... sustained long term to minimize risks over time.”

Large dataset: Use age at diagnosis to risk stratify patients

Rates of type 2 diabetes have increased in all age groups and virtually all countries over the past 3 decades. Particularly worrying is a trend toward increased rates among adults aged 20-44 years. The increases are associated with higher rates of overweight and obesity, poor diet, and decreasing levels of physical activity, numerous studies have shown.

But few studies have examined the association between age at diagnosis and subsequent complications from type 2 diabetes, the authors noted.

Their review included 26 observational studies involving more than one million individuals from 30 countries in the Asia Pacific, Europe, and North America. The investigators found that each 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis was significantly associated with a 4%, 3%, and 5% decreased risk for all-cause mortality, macrovascular disease, and microvascular disease, respectively, adjusted for current age (all P < .001).

Similar decreases in risk per 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis were seen for coronary heart disease (2%), cerebrovascular disease (2%), peripheral vascular disease (3%), retinopathy (8%), nephropathy (6%), and neuropathy (5%); all associations were significant (P < .001).

Dr. Nanayakkara and colleagues noted that current treatment guidelines are limited in that they’re related to the management of patients with suboptimal blood glucose control, and there is no way to predict which people require intensified treatment.

Therefore, they said, “refined stratification using age at diagnosis may provide a method of identifying, at diagnosis, those at greatest risk of complications who would most benefit from targeted, individualized treatment regimens.”

Awareness of this “hidden” danger to younger adults with type 2 diabetes is becoming more and more important, because such cases continue to rise, they reiterated.

They also advised that “public health measures to delay and/or prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes until older age may yield benefits by reducing the duration of diabetes and the burden of complications.”

Dr. Nanayakkara disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Those who are found to have type 2 diabetes at a younger age face “hidden” dangers. The issue is becoming more and more important, “since new diagnoses in this younger age group continue to rise,” said the authors of a new study, led by Natalie Nanayakkara, MD.

They believe clinical approaches should be based on age at diagnosis. The results of their new meta-analysis, published online in Diabetologia, reveal the extent of the problem.

Believed to be the first systematic review of its kind, the study showed that the younger the age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, the greater the risks of dying and of having either microvascular or macrovascular complications each subsequent year (adjusted for current age).

“This difference in risk between younger and older people in terms of absolute versus lifetime risks of type 2 diabetes complications should perhaps be recognized in diabetes management guidelines,” wrote Dr. Nanayakkara, an endocrinologist at Monash University, Melbourne, and colleagues.

Those diagnosed at younger ages are more likely to develop complications that cause greater disability and lead to loss of productivity compared with people diagnosed at an older age, they stressed.

Hence, they suggested “a greater emphasis on preventive measures for younger people with type 2 diabetes,” with “early intensive multifactorial risk factor intervention ... sustained long term to minimize risks over time.”

Large dataset: Use age at diagnosis to risk stratify patients

Rates of type 2 diabetes have increased in all age groups and virtually all countries over the past 3 decades. Particularly worrying is a trend toward increased rates among adults aged 20-44 years. The increases are associated with higher rates of overweight and obesity, poor diet, and decreasing levels of physical activity, numerous studies have shown.

But few studies have examined the association between age at diagnosis and subsequent complications from type 2 diabetes, the authors noted.

Their review included 26 observational studies involving more than one million individuals from 30 countries in the Asia Pacific, Europe, and North America. The investigators found that each 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis was significantly associated with a 4%, 3%, and 5% decreased risk for all-cause mortality, macrovascular disease, and microvascular disease, respectively, adjusted for current age (all P < .001).

Similar decreases in risk per 1-year increase in age at diabetes diagnosis were seen for coronary heart disease (2%), cerebrovascular disease (2%), peripheral vascular disease (3%), retinopathy (8%), nephropathy (6%), and neuropathy (5%); all associations were significant (P < .001).

Dr. Nanayakkara and colleagues noted that current treatment guidelines are limited in that they’re related to the management of patients with suboptimal blood glucose control, and there is no way to predict which people require intensified treatment.

Therefore, they said, “refined stratification using age at diagnosis may provide a method of identifying, at diagnosis, those at greatest risk of complications who would most benefit from targeted, individualized treatment regimens.”

Awareness of this “hidden” danger to younger adults with type 2 diabetes is becoming more and more important, because such cases continue to rise, they reiterated.

They also advised that “public health measures to delay and/or prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes until older age may yield benefits by reducing the duration of diabetes and the burden of complications.”

Dr. Nanayakkara disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 vaccine rollout faces delays

If the current pace of vaccination continues, “it’s going to take years, not months, to vaccinate the American people,” President-elect Joe Biden said during a briefing Dec. 29.

In fact, at the current rate, it would take nearly 10 years to vaccinate enough Americans to bring the pandemic under control, according to NBC News. To reach 80% of the country by late June, 3 million people would need to receive a COVID-19 vaccine each day.

“As I long feared and warned, the effort to distribute and administer the vaccine is not progressing as it should,” Mr. Biden said, reemphasizing his pledge to get 100 million doses to Americans during his first 100 days as president.

So far, 11.4 million doses have been distributed and 2.1 million people have received a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most states have administered a fraction of the doses they’ve received, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

Federal officials have said there’s an “expected lag” between delivery of doses, shots going into arms, and the data being reported to the CDC, according to CNN. The Food and Drug Administration must assess each shipment for quality control, which has slowed down distribution, and the CDC data are just now beginning to include the Moderna vaccine, which the FDA authorized for emergency use on Dec. 18.

The 2.1 million number is “an underestimate,” Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, told NBC News Dec. 29. At the same time, the U.S. won’t meet the goal of vaccinating 20 million people in the next few days, he said.

Another 30 million doses will go out in January, Dr. Giroir said, followed by 50 million in February.

Some vaccine experts have said they’re not surprised by the speed of vaccine distribution.

“It had to go this way,” Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT. “We had to trip and fall and stumble and figure this out.”

To speed up distribution in 2021, the federal government will need to help states, Mr. Biden said Dec. 29. He plans to use the Defense Authorization Act to ramp up production of vaccine supplies. Even still, the process will take months, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

If the current pace of vaccination continues, “it’s going to take years, not months, to vaccinate the American people,” President-elect Joe Biden said during a briefing Dec. 29.

In fact, at the current rate, it would take nearly 10 years to vaccinate enough Americans to bring the pandemic under control, according to NBC News. To reach 80% of the country by late June, 3 million people would need to receive a COVID-19 vaccine each day.

“As I long feared and warned, the effort to distribute and administer the vaccine is not progressing as it should,” Mr. Biden said, reemphasizing his pledge to get 100 million doses to Americans during his first 100 days as president.

So far, 11.4 million doses have been distributed and 2.1 million people have received a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most states have administered a fraction of the doses they’ve received, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

Federal officials have said there’s an “expected lag” between delivery of doses, shots going into arms, and the data being reported to the CDC, according to CNN. The Food and Drug Administration must assess each shipment for quality control, which has slowed down distribution, and the CDC data are just now beginning to include the Moderna vaccine, which the FDA authorized for emergency use on Dec. 18.

The 2.1 million number is “an underestimate,” Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, told NBC News Dec. 29. At the same time, the U.S. won’t meet the goal of vaccinating 20 million people in the next few days, he said.

Another 30 million doses will go out in January, Dr. Giroir said, followed by 50 million in February.

Some vaccine experts have said they’re not surprised by the speed of vaccine distribution.

“It had to go this way,” Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT. “We had to trip and fall and stumble and figure this out.”

To speed up distribution in 2021, the federal government will need to help states, Mr. Biden said Dec. 29. He plans to use the Defense Authorization Act to ramp up production of vaccine supplies. Even still, the process will take months, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

If the current pace of vaccination continues, “it’s going to take years, not months, to vaccinate the American people,” President-elect Joe Biden said during a briefing Dec. 29.

In fact, at the current rate, it would take nearly 10 years to vaccinate enough Americans to bring the pandemic under control, according to NBC News. To reach 80% of the country by late June, 3 million people would need to receive a COVID-19 vaccine each day.

“As I long feared and warned, the effort to distribute and administer the vaccine is not progressing as it should,” Mr. Biden said, reemphasizing his pledge to get 100 million doses to Americans during his first 100 days as president.

So far, 11.4 million doses have been distributed and 2.1 million people have received a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most states have administered a fraction of the doses they’ve received, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

Federal officials have said there’s an “expected lag” between delivery of doses, shots going into arms, and the data being reported to the CDC, according to CNN. The Food and Drug Administration must assess each shipment for quality control, which has slowed down distribution, and the CDC data are just now beginning to include the Moderna vaccine, which the FDA authorized for emergency use on Dec. 18.

The 2.1 million number is “an underestimate,” Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, told NBC News Dec. 29. At the same time, the U.S. won’t meet the goal of vaccinating 20 million people in the next few days, he said.

Another 30 million doses will go out in January, Dr. Giroir said, followed by 50 million in February.

Some vaccine experts have said they’re not surprised by the speed of vaccine distribution.

“It had to go this way,” Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT. “We had to trip and fall and stumble and figure this out.”

To speed up distribution in 2021, the federal government will need to help states, Mr. Biden said Dec. 29. He plans to use the Defense Authorization Act to ramp up production of vaccine supplies. Even still, the process will take months, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

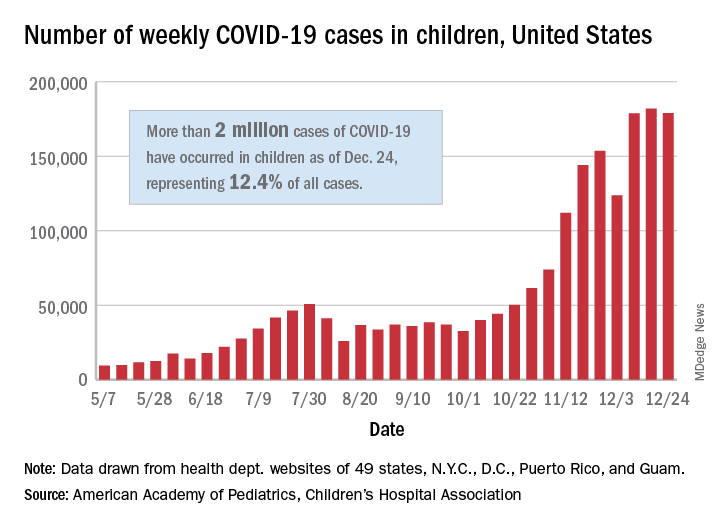

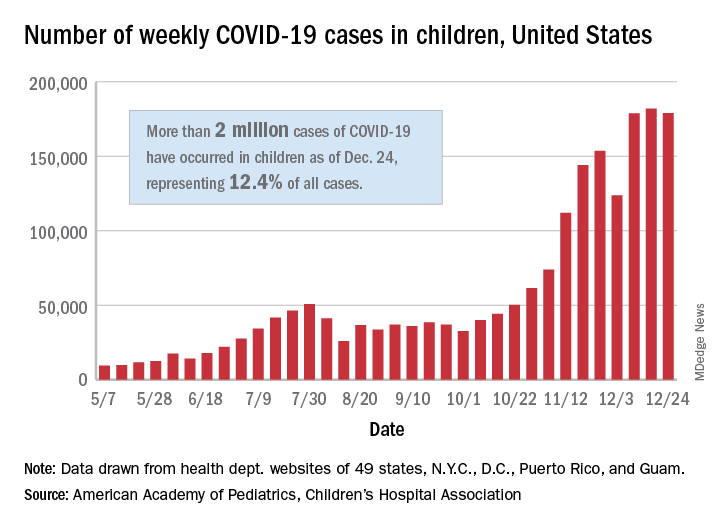

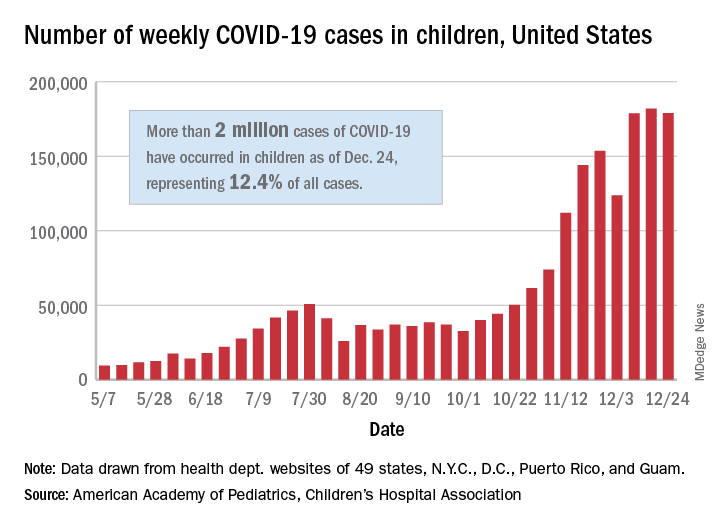

New pediatric cases down as U.S. tops 2 million children with COVID-19

The United States exceeded 2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in children just 6 weeks after recording its 1 millionth case, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of cases in children was 2,000,681 as of Dec. 24, which represents 12.4% of all cases reported by the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA stated Dec. 29.

The case count for just the latest week, 178,935, was actually down 1.7% from the 182,018 reported the week before, marking the second drop since the beginning of December. The first came during the week ending Dec. 3, when the number of cases dropped more than 19% from the previous week, based on data from the AAP/CHA report.

The cumulative national rate of coronavirus infection is now 2,658 cases per 100,000 children, and “13 states have reported more than 4,000 cases per 100,000,” the two groups said.

The highest rate for any state can be found in North Dakota, which has had 7,722 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 children. Wyoming has the highest proportion of cases in children at 20.5%, and California has reported the most cases overall, 234,174, the report shows.

Data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality were not included in the Dec. 29 report because of the holiday but will be available in the next edition, scheduled for release on Jan. 5, 2021.

The United States exceeded 2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in children just 6 weeks after recording its 1 millionth case, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of cases in children was 2,000,681 as of Dec. 24, which represents 12.4% of all cases reported by the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA stated Dec. 29.

The case count for just the latest week, 178,935, was actually down 1.7% from the 182,018 reported the week before, marking the second drop since the beginning of December. The first came during the week ending Dec. 3, when the number of cases dropped more than 19% from the previous week, based on data from the AAP/CHA report.

The cumulative national rate of coronavirus infection is now 2,658 cases per 100,000 children, and “13 states have reported more than 4,000 cases per 100,000,” the two groups said.

The highest rate for any state can be found in North Dakota, which has had 7,722 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 children. Wyoming has the highest proportion of cases in children at 20.5%, and California has reported the most cases overall, 234,174, the report shows.

Data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality were not included in the Dec. 29 report because of the holiday but will be available in the next edition, scheduled for release on Jan. 5, 2021.

The United States exceeded 2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in children just 6 weeks after recording its 1 millionth case, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of cases in children was 2,000,681 as of Dec. 24, which represents 12.4% of all cases reported by the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA stated Dec. 29.

The case count for just the latest week, 178,935, was actually down 1.7% from the 182,018 reported the week before, marking the second drop since the beginning of December. The first came during the week ending Dec. 3, when the number of cases dropped more than 19% from the previous week, based on data from the AAP/CHA report.

The cumulative national rate of coronavirus infection is now 2,658 cases per 100,000 children, and “13 states have reported more than 4,000 cases per 100,000,” the two groups said.

The highest rate for any state can be found in North Dakota, which has had 7,722 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 children. Wyoming has the highest proportion of cases in children at 20.5%, and California has reported the most cases overall, 234,174, the report shows.

Data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality were not included in the Dec. 29 report because of the holiday but will be available in the next edition, scheduled for release on Jan. 5, 2021.

New dietary guidelines omit recommended cuts to sugar, alcohol intake

Although the new guidelines were informed by an advisory committee’s scientific report, officials omitted certain recommendations that would have reduced allowances for added sugars and alcohol intake.

The 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans “carried forward the committee’s emphasis on limiting these dietary components, but did not include changes to quantitative recommendations, as there was not a preponderance of evidence in the material the committee reviewed to support specific changes, as required by law,” the agencies said in a news release.

The guidelines encourage Americans to “Make Every Bite Count” through four overarching suggestions:

- Follow a healthy dietary pattern at every life stage.

- Customize nutrient-dense food and beverage choices to reflect preferences, cultural traditions, and budgets.

- Focus on meeting dietary needs from five food groups – vegetables, fruits, grains, dairy and fortified soy alternatives, and proteins – and stay within calorie limits.

- Limit foods and beverages that are higher in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium, and limit alcoholic beverages.

The guidance “can help all Americans lead healthier lives by making every bite count,” Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue said.

Proposed cutoffs rejected

The guidelines omit a recommendation from the advisory committee’s scientific report to reduce intake of added sugars from less than 10% of calories to less than 6% of calories.

It also omits a recommendation that men and women who drink alcohol limit themselves to one drink per day. It maintains guidance from the 2015-2020 edition that allows two drinks per day for men.

The agencies published a document explaining why they omitted the advisory committee›s conclusions.

The American Heart Association in July had praised the suggestion to reduce added sugars. The proposed change would have helped “steer the public toward a more heart-healthy path in their daily diets,” Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, president of the AHA, said at the time. The association would “strongly oppose any efforts to weaken these recommendations,” he added.

In its response to the new guidelines, Dr. Elkind praised the emphasis on a healthy diet “at every life stage” but called out a missed opportunity.

“We are disappointed that USDA and HHS did not accept all of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee’s science-based recommendations in the final guidelines for 2020, including the recommendation to lower added sugars consumption to less than 6% of calories,” he said in a prepared statement.

Guidance for infants and toddlers

The guidelines advise that for about the first 6 months of life, infants should exclusively receive breast milk. Infants should continue to receive breast milk through at least the first year of life, and longer if desired. Infants should be fed iron-fortified infant formula during the first year of life when breast milk is unavailable, and infants should receive supplemental vitamin D soon after birth, the guidelines advise.

At about 6 months, infants should be introduced to a variety of nutrient-dense complementary foods, including potentially allergenic foods. Infants should eat foods that are rich in iron and zinc, particularly if they are fed breast milk.

The guidelines also include dietary and caloric advice for pregnant and lactating women with daily or weekly amounts of food from different groups and subgroups.

Dr. Elkind highlighted the significance of these additions.

“We are pleased that for the first time, the guidelines provide recommendations for pregnant and breastfeeding women as well as infants and toddlers, underscoring the importance of maternal health and proper nutrition across the lifespan,” he said.

For all ages

From 12 months through older adulthood, people should follow a healthy dietary pattern to meet nutrient needs, help achieve a healthy body weight, and reduce the risk of chronic disease.

According to the guidelines, core elements of a healthy diet include:

- Vegetables of all types (dark green; red and orange; beans, peas, and lentils; starchy; and other types).

- Fruits (especially whole fruit).

- Grains, at least half of which are whole grain.

- Dairy, including fat-free or low-fat milk, yogurt, and cheese, and lactose-free versions; and fortified soy beverages and yogurt as alternatives.

- Protein foods, including lean meats, poultry, and eggs; seafood; beans, peas, and lentils; and nuts, seeds, and soy products.

- Oils, including vegetable oils and oils in food, such as seafood and nuts.

The guidelines spell out limits to added sugars, sodium, saturated fat, and alcohol. The recommendation to limit added sugars to less than 10% of calories per day starts at age 2 years. Before age 2, foods and beverages with added sugars should be avoided.

Saturated fat should be limited to less than 10% of calories per day starting at age 2. And sodium intake should be limited to 2,300 mg/day for those age 14 and older, but just 1,200 mg/day for toddlers, 1,500 mg/day for children aged 4-8, and 1,800 mg/day for children 9-13.

“Adults of legal drinking age can choose not to drink or to drink in moderation by limiting intake to 2 drinks or less in a day for men and 1 drink or less in a day for women, when alcohol is consumed,” the agencies said. “Drinking less is better for health than drinking more. There are some adults who should not drink alcohol, such as women who are pregnant.”

An appendix includes estimated calorie needs based on a person’s age, sex, height, weight, and level of physical activity. A need to lose, maintain, or gain weight are among the factors that influence how many calories should be consumed, the guidelines note.

The guidelines are designed for use by health care professionals and policymakers. The USDA has launched a new MyPlate website to help consumers incorporate the dietary guidance.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although the new guidelines were informed by an advisory committee’s scientific report, officials omitted certain recommendations that would have reduced allowances for added sugars and alcohol intake.

The 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans “carried forward the committee’s emphasis on limiting these dietary components, but did not include changes to quantitative recommendations, as there was not a preponderance of evidence in the material the committee reviewed to support specific changes, as required by law,” the agencies said in a news release.

The guidelines encourage Americans to “Make Every Bite Count” through four overarching suggestions:

- Follow a healthy dietary pattern at every life stage.

- Customize nutrient-dense food and beverage choices to reflect preferences, cultural traditions, and budgets.

- Focus on meeting dietary needs from five food groups – vegetables, fruits, grains, dairy and fortified soy alternatives, and proteins – and stay within calorie limits.

- Limit foods and beverages that are higher in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium, and limit alcoholic beverages.

The guidance “can help all Americans lead healthier lives by making every bite count,” Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue said.

Proposed cutoffs rejected

The guidelines omit a recommendation from the advisory committee’s scientific report to reduce intake of added sugars from less than 10% of calories to less than 6% of calories.

It also omits a recommendation that men and women who drink alcohol limit themselves to one drink per day. It maintains guidance from the 2015-2020 edition that allows two drinks per day for men.

The agencies published a document explaining why they omitted the advisory committee›s conclusions.

The American Heart Association in July had praised the suggestion to reduce added sugars. The proposed change would have helped “steer the public toward a more heart-healthy path in their daily diets,” Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, president of the AHA, said at the time. The association would “strongly oppose any efforts to weaken these recommendations,” he added.

In its response to the new guidelines, Dr. Elkind praised the emphasis on a healthy diet “at every life stage” but called out a missed opportunity.

“We are disappointed that USDA and HHS did not accept all of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee’s science-based recommendations in the final guidelines for 2020, including the recommendation to lower added sugars consumption to less than 6% of calories,” he said in a prepared statement.

Guidance for infants and toddlers

The guidelines advise that for about the first 6 months of life, infants should exclusively receive breast milk. Infants should continue to receive breast milk through at least the first year of life, and longer if desired. Infants should be fed iron-fortified infant formula during the first year of life when breast milk is unavailable, and infants should receive supplemental vitamin D soon after birth, the guidelines advise.

At about 6 months, infants should be introduced to a variety of nutrient-dense complementary foods, including potentially allergenic foods. Infants should eat foods that are rich in iron and zinc, particularly if they are fed breast milk.

The guidelines also include dietary and caloric advice for pregnant and lactating women with daily or weekly amounts of food from different groups and subgroups.

Dr. Elkind highlighted the significance of these additions.

“We are pleased that for the first time, the guidelines provide recommendations for pregnant and breastfeeding women as well as infants and toddlers, underscoring the importance of maternal health and proper nutrition across the lifespan,” he said.

For all ages

From 12 months through older adulthood, people should follow a healthy dietary pattern to meet nutrient needs, help achieve a healthy body weight, and reduce the risk of chronic disease.

According to the guidelines, core elements of a healthy diet include:

- Vegetables of all types (dark green; red and orange; beans, peas, and lentils; starchy; and other types).

- Fruits (especially whole fruit).

- Grains, at least half of which are whole grain.

- Dairy, including fat-free or low-fat milk, yogurt, and cheese, and lactose-free versions; and fortified soy beverages and yogurt as alternatives.

- Protein foods, including lean meats, poultry, and eggs; seafood; beans, peas, and lentils; and nuts, seeds, and soy products.

- Oils, including vegetable oils and oils in food, such as seafood and nuts.

The guidelines spell out limits to added sugars, sodium, saturated fat, and alcohol. The recommendation to limit added sugars to less than 10% of calories per day starts at age 2 years. Before age 2, foods and beverages with added sugars should be avoided.

Saturated fat should be limited to less than 10% of calories per day starting at age 2. And sodium intake should be limited to 2,300 mg/day for those age 14 and older, but just 1,200 mg/day for toddlers, 1,500 mg/day for children aged 4-8, and 1,800 mg/day for children 9-13.

“Adults of legal drinking age can choose not to drink or to drink in moderation by limiting intake to 2 drinks or less in a day for men and 1 drink or less in a day for women, when alcohol is consumed,” the agencies said. “Drinking less is better for health than drinking more. There are some adults who should not drink alcohol, such as women who are pregnant.”

An appendix includes estimated calorie needs based on a person’s age, sex, height, weight, and level of physical activity. A need to lose, maintain, or gain weight are among the factors that influence how many calories should be consumed, the guidelines note.

The guidelines are designed for use by health care professionals and policymakers. The USDA has launched a new MyPlate website to help consumers incorporate the dietary guidance.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although the new guidelines were informed by an advisory committee’s scientific report, officials omitted certain recommendations that would have reduced allowances for added sugars and alcohol intake.

The 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans “carried forward the committee’s emphasis on limiting these dietary components, but did not include changes to quantitative recommendations, as there was not a preponderance of evidence in the material the committee reviewed to support specific changes, as required by law,” the agencies said in a news release.

The guidelines encourage Americans to “Make Every Bite Count” through four overarching suggestions:

- Follow a healthy dietary pattern at every life stage.

- Customize nutrient-dense food and beverage choices to reflect preferences, cultural traditions, and budgets.

- Focus on meeting dietary needs from five food groups – vegetables, fruits, grains, dairy and fortified soy alternatives, and proteins – and stay within calorie limits.

- Limit foods and beverages that are higher in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium, and limit alcoholic beverages.

The guidance “can help all Americans lead healthier lives by making every bite count,” Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue said.

Proposed cutoffs rejected

The guidelines omit a recommendation from the advisory committee’s scientific report to reduce intake of added sugars from less than 10% of calories to less than 6% of calories.

It also omits a recommendation that men and women who drink alcohol limit themselves to one drink per day. It maintains guidance from the 2015-2020 edition that allows two drinks per day for men.

The agencies published a document explaining why they omitted the advisory committee›s conclusions.

The American Heart Association in July had praised the suggestion to reduce added sugars. The proposed change would have helped “steer the public toward a more heart-healthy path in their daily diets,” Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, president of the AHA, said at the time. The association would “strongly oppose any efforts to weaken these recommendations,” he added.

In its response to the new guidelines, Dr. Elkind praised the emphasis on a healthy diet “at every life stage” but called out a missed opportunity.

“We are disappointed that USDA and HHS did not accept all of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee’s science-based recommendations in the final guidelines for 2020, including the recommendation to lower added sugars consumption to less than 6% of calories,” he said in a prepared statement.

Guidance for infants and toddlers

The guidelines advise that for about the first 6 months of life, infants should exclusively receive breast milk. Infants should continue to receive breast milk through at least the first year of life, and longer if desired. Infants should be fed iron-fortified infant formula during the first year of life when breast milk is unavailable, and infants should receive supplemental vitamin D soon after birth, the guidelines advise.

At about 6 months, infants should be introduced to a variety of nutrient-dense complementary foods, including potentially allergenic foods. Infants should eat foods that are rich in iron and zinc, particularly if they are fed breast milk.

The guidelines also include dietary and caloric advice for pregnant and lactating women with daily or weekly amounts of food from different groups and subgroups.

Dr. Elkind highlighted the significance of these additions.

“We are pleased that for the first time, the guidelines provide recommendations for pregnant and breastfeeding women as well as infants and toddlers, underscoring the importance of maternal health and proper nutrition across the lifespan,” he said.

For all ages

From 12 months through older adulthood, people should follow a healthy dietary pattern to meet nutrient needs, help achieve a healthy body weight, and reduce the risk of chronic disease.

According to the guidelines, core elements of a healthy diet include:

- Vegetables of all types (dark green; red and orange; beans, peas, and lentils; starchy; and other types).

- Fruits (especially whole fruit).

- Grains, at least half of which are whole grain.

- Dairy, including fat-free or low-fat milk, yogurt, and cheese, and lactose-free versions; and fortified soy beverages and yogurt as alternatives.

- Protein foods, including lean meats, poultry, and eggs; seafood; beans, peas, and lentils; and nuts, seeds, and soy products.

- Oils, including vegetable oils and oils in food, such as seafood and nuts.

The guidelines spell out limits to added sugars, sodium, saturated fat, and alcohol. The recommendation to limit added sugars to less than 10% of calories per day starts at age 2 years. Before age 2, foods and beverages with added sugars should be avoided.

Saturated fat should be limited to less than 10% of calories per day starting at age 2. And sodium intake should be limited to 2,300 mg/day for those age 14 and older, but just 1,200 mg/day for toddlers, 1,500 mg/day for children aged 4-8, and 1,800 mg/day for children 9-13.

“Adults of legal drinking age can choose not to drink or to drink in moderation by limiting intake to 2 drinks or less in a day for men and 1 drink or less in a day for women, when alcohol is consumed,” the agencies said. “Drinking less is better for health than drinking more. There are some adults who should not drink alcohol, such as women who are pregnant.”

An appendix includes estimated calorie needs based on a person’s age, sex, height, weight, and level of physical activity. A need to lose, maintain, or gain weight are among the factors that influence how many calories should be consumed, the guidelines note.

The guidelines are designed for use by health care professionals and policymakers. The USDA has launched a new MyPlate website to help consumers incorporate the dietary guidance.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

2.1 Million COVID Vaccine Doses Given in U.S.

The U.S. has distributed more than 11.4 million doses of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, and more than 2.1 million of those had been given to people as of December 28, according to the CDC.

The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker showed the updated numbers as of 9 a.m. on that day. The distribution total is based on the CDC’s Vaccine Tracking System, and the administered total is based on reports from state and local public health departments, as well as updates from five federal agencies: the Bureau of Prisons, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, Department of State, and Indian Health Services.

Health care providers report to public health agencies up to 72 hours after the vaccine is given, and public health agencies report to the CDC after that, so there may be a lag in the data. The CDC’s numbers will be updated on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

“A large difference between the number of doses distributed and the number of doses administered is expected at this point in the COVID vaccination program due to several factors,” the CDC says.

Delays could occur due to the reporting of doses given, how states and local vaccine sites are managing vaccines, and the pending launch of vaccination through the federal Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program.

“Numbers reported on other websites may differ from what is posted on CDC’s website because CDC’s overall numbers are validated through a data submission process with each jurisdiction,” the CDC says.

On Dec. 26, the agency’s tally showed that 9.5 million doses had been distributed and 1.9 million had been given, according to Reuters.

Public health officials and health care workers have begun to voice their concerns about the delay in giving the vaccines.

“We certainly are not at the numbers that we wanted to be at the end of December,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNNDec. 29.

Operation Warp Speed had planned for 20 million people to be vaccinated by the end of the year. Fauci said he hopes that number will be achieved next month.

“I believe that as we get into January, we are going to see an increase in the momentum,” he said.

Shipment delays have affected other priority groups as well. The New York Police Department anticipated a rollout Dec. 29, but it’s now been delayed since the department hasn’t received enough Moderna doses to start giving the shots, according to the New York Daily News.

“We’ve made numerous attempts to get updated information, and when we get further word on its availability, we will immediately keep our members appraised of the new date and the method of distribution,” Paul DiGiacomo, president of the Detectives’ Endowment Association, wrote in a memo to members on Dec. 28.

“Every detective squad has been crushed with [COVID-19],” he told the newspaper. “Within the last couple of weeks, we’ve had at least two detectives hospitalized.”

President-elect Joe Biden will receive a briefing from his COVID-19 advisory team, provide a general update on the pandemic, and describe his own plan for vaccinating people quickly during an address Dec. 29, a transition official told Axios. Biden has pledged to administer 100 million vaccine doses in his first 100 days in office.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMd.

The U.S. has distributed more than 11.4 million doses of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, and more than 2.1 million of those had been given to people as of December 28, according to the CDC.

The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker showed the updated numbers as of 9 a.m. on that day. The distribution total is based on the CDC’s Vaccine Tracking System, and the administered total is based on reports from state and local public health departments, as well as updates from five federal agencies: the Bureau of Prisons, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, Department of State, and Indian Health Services.

Health care providers report to public health agencies up to 72 hours after the vaccine is given, and public health agencies report to the CDC after that, so there may be a lag in the data. The CDC’s numbers will be updated on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

“A large difference between the number of doses distributed and the number of doses administered is expected at this point in the COVID vaccination program due to several factors,” the CDC says.

Delays could occur due to the reporting of doses given, how states and local vaccine sites are managing vaccines, and the pending launch of vaccination through the federal Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program.

“Numbers reported on other websites may differ from what is posted on CDC’s website because CDC’s overall numbers are validated through a data submission process with each jurisdiction,” the CDC says.

On Dec. 26, the agency’s tally showed that 9.5 million doses had been distributed and 1.9 million had been given, according to Reuters.

Public health officials and health care workers have begun to voice their concerns about the delay in giving the vaccines.

“We certainly are not at the numbers that we wanted to be at the end of December,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNNDec. 29.

Operation Warp Speed had planned for 20 million people to be vaccinated by the end of the year. Fauci said he hopes that number will be achieved next month.

“I believe that as we get into January, we are going to see an increase in the momentum,” he said.

Shipment delays have affected other priority groups as well. The New York Police Department anticipated a rollout Dec. 29, but it’s now been delayed since the department hasn’t received enough Moderna doses to start giving the shots, according to the New York Daily News.

“We’ve made numerous attempts to get updated information, and when we get further word on its availability, we will immediately keep our members appraised of the new date and the method of distribution,” Paul DiGiacomo, president of the Detectives’ Endowment Association, wrote in a memo to members on Dec. 28.

“Every detective squad has been crushed with [COVID-19],” he told the newspaper. “Within the last couple of weeks, we’ve had at least two detectives hospitalized.”

President-elect Joe Biden will receive a briefing from his COVID-19 advisory team, provide a general update on the pandemic, and describe his own plan for vaccinating people quickly during an address Dec. 29, a transition official told Axios. Biden has pledged to administer 100 million vaccine doses in his first 100 days in office.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMd.

The U.S. has distributed more than 11.4 million doses of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, and more than 2.1 million of those had been given to people as of December 28, according to the CDC.

The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker showed the updated numbers as of 9 a.m. on that day. The distribution total is based on the CDC’s Vaccine Tracking System, and the administered total is based on reports from state and local public health departments, as well as updates from five federal agencies: the Bureau of Prisons, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, Department of State, and Indian Health Services.

Health care providers report to public health agencies up to 72 hours after the vaccine is given, and public health agencies report to the CDC after that, so there may be a lag in the data. The CDC’s numbers will be updated on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

“A large difference between the number of doses distributed and the number of doses administered is expected at this point in the COVID vaccination program due to several factors,” the CDC says.

Delays could occur due to the reporting of doses given, how states and local vaccine sites are managing vaccines, and the pending launch of vaccination through the federal Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program.

“Numbers reported on other websites may differ from what is posted on CDC’s website because CDC’s overall numbers are validated through a data submission process with each jurisdiction,” the CDC says.

On Dec. 26, the agency’s tally showed that 9.5 million doses had been distributed and 1.9 million had been given, according to Reuters.

Public health officials and health care workers have begun to voice their concerns about the delay in giving the vaccines.

“We certainly are not at the numbers that we wanted to be at the end of December,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNNDec. 29.

Operation Warp Speed had planned for 20 million people to be vaccinated by the end of the year. Fauci said he hopes that number will be achieved next month.

“I believe that as we get into January, we are going to see an increase in the momentum,” he said.

Shipment delays have affected other priority groups as well. The New York Police Department anticipated a rollout Dec. 29, but it’s now been delayed since the department hasn’t received enough Moderna doses to start giving the shots, according to the New York Daily News.

“We’ve made numerous attempts to get updated information, and when we get further word on its availability, we will immediately keep our members appraised of the new date and the method of distribution,” Paul DiGiacomo, president of the Detectives’ Endowment Association, wrote in a memo to members on Dec. 28.

“Every detective squad has been crushed with [COVID-19],” he told the newspaper. “Within the last couple of weeks, we’ve had at least two detectives hospitalized.”

President-elect Joe Biden will receive a briefing from his COVID-19 advisory team, provide a general update on the pandemic, and describe his own plan for vaccinating people quickly during an address Dec. 29, a transition official told Axios. Biden has pledged to administer 100 million vaccine doses in his first 100 days in office.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMd.

CDC issues COVID-19 vaccine guidance for underlying conditions

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued updated guidance for people with underlying medical conditions who are considering getting the coronavirus vaccine.

“Adults of any age with certain underlying medical conditions are at increased risk for severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” the CDC said in the guidance, posted on Dec. 26. “mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may be administered to people with underlying medical conditions provided they have not had a severe allergic reaction to any of the ingredients in the vaccine.”

Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use mRNA, or messenger RNA.

The CDC guidance had specific information for people with HIV, weakened immune systems, and autoimmune conditions such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and Bell’s palsy who are thinking of getting the vaccine.

People with HIV and weakened immune systems “may receive a COVID-19 vaccine. However, they should be aware of the limited safety data,” the CDC said.

There’s no information available yet about the safety of the vaccines for people with weakened immune systems. People with HIV were included in clinical trials, but “safety data specific to this group are not yet available at this time,” the CDC said.

Cases of Bell’s palsy, a temporary facial paralysis, were reported in people receiving the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in clinical trials, the Food and Drug Administration said Dec. 17.

But the new CDC guidance said that the FDA “does not consider these to be above the rate expected in the general population. They have not concluded these cases were caused by vaccination. Therefore, persons who have previously had Bell’s palsy may receive an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.”

Researchers have determined the vaccines are safe for people with GBS, a rare autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks nerves just as they leave the spinal cord, the CDC said.

“To date, no cases of GBS have been reported following vaccination among participants in the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials,” the CDC guidance said. “With few exceptions, the independent Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices general best practice guidelines for immunization do not include a history of GBS as a precaution to vaccination with other vaccines.”

For months, the CDC and other health authorities have said that people with certain medical conditions are at an increased risk of developing severe cases of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued updated guidance for people with underlying medical conditions who are considering getting the coronavirus vaccine.

“Adults of any age with certain underlying medical conditions are at increased risk for severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” the CDC said in the guidance, posted on Dec. 26. “mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may be administered to people with underlying medical conditions provided they have not had a severe allergic reaction to any of the ingredients in the vaccine.”

Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use mRNA, or messenger RNA.

The CDC guidance had specific information for people with HIV, weakened immune systems, and autoimmune conditions such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and Bell’s palsy who are thinking of getting the vaccine.

People with HIV and weakened immune systems “may receive a COVID-19 vaccine. However, they should be aware of the limited safety data,” the CDC said.

There’s no information available yet about the safety of the vaccines for people with weakened immune systems. People with HIV were included in clinical trials, but “safety data specific to this group are not yet available at this time,” the CDC said.

Cases of Bell’s palsy, a temporary facial paralysis, were reported in people receiving the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in clinical trials, the Food and Drug Administration said Dec. 17.

But the new CDC guidance said that the FDA “does not consider these to be above the rate expected in the general population. They have not concluded these cases were caused by vaccination. Therefore, persons who have previously had Bell’s palsy may receive an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.”

Researchers have determined the vaccines are safe for people with GBS, a rare autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks nerves just as they leave the spinal cord, the CDC said.

“To date, no cases of GBS have been reported following vaccination among participants in the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials,” the CDC guidance said. “With few exceptions, the independent Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices general best practice guidelines for immunization do not include a history of GBS as a precaution to vaccination with other vaccines.”

For months, the CDC and other health authorities have said that people with certain medical conditions are at an increased risk of developing severe cases of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued updated guidance for people with underlying medical conditions who are considering getting the coronavirus vaccine.