User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Children’s hospitals grapple with wave of mental illness

Krissy Williams, 15, had attempted suicide before, but never with pills.

The teen was diagnosed with schizophrenia when she was 9. People with this chronic mental health condition perceive reality differently and often experience hallucinations and delusions. She learned to manage these symptoms with a variety of services offered at home and at school.

But the pandemic upended those lifelines. She lost much of the support offered at school. She also lost regular contact with her peers. Her mother lost access to respite care – which allowed her to take a break.

On a Thursday in October, the isolation and sadness came to a head. As Krissy’s mother, Patricia Williams, called a mental crisis hotline for help, she said, Krissy stood on the deck of their Maryland home with a bottle of pain medication in one hand and water in the other.

Before Patricia could react, Krissy placed the pills in her mouth and swallowed.

Efforts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus in the United States have led to drastic changes in the way children and teens learn, play and socialize. Tens of millions of students are attending school through some form of distance learning. Many extracurricular activities have been canceled. Playgrounds, zoos, and other recreational spaces have closed. Kids like Krissy have struggled to cope and the toll is becoming evident.

Government figures show the proportion of children who arrived in EDs with mental health issues increased 24% from mid-March through mid-October, compared with the same period in 2019. Among preteens and adolescents, it rose by 31%. Anecdotally, some hospitals said they are seeing more cases of severe depression and suicidal thoughts among children, particularly attempts to overdose.

The increased demand for intensive mental health care that has accompanied the pandemic has worsened issues that have long plagued the system. In some hospitals, the number of children unable to immediately get a bed in the psychiatric unit rose. Others reduced the number of beds or closed psychiatric units altogether to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

“It’s only a matter of time before a tsunami sort of reaches the shore of our service system, and it’s going to be overwhelmed with the mental health needs of kids,” said Jason Williams, PsyD, a psychologist and director of operations of the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

“I think we’re just starting to see the tip of the iceberg, to be honest with you.”

Before COVID, more than 8 million kids between ages 3 and 17 were diagnosed with a mental or behavioral health condition, according to the most recent National Survey of Children’s Health. A separate survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found one in three high school students in 2019 reported feeling persistently sad and hopeless – a 40% increase from 2009.

The coronavirus pandemic appears to be adding to these difficulties. A review of 80 studies found forced isolation and loneliness among children correlated with an increased risk of depression.

“We’re all social beings, but they’re [teenagers] at the point in their development where their peers are their reality,” said Terrie Andrews, PhD, a psychologist and administrator of behavioral health at Wolfson Children’s Hospital in Jacksonville, Fla. “Their peers are their grounding mechanism.”

Children’s hospitals in Colorado, Missouri, and New York all reported an uptick in the number of patients who thought about or attempted suicide. Clinicians also mentioned spikes in children with severe depression and those with autism who are acting out.

The number of overdose attempts among children has caught the attention of clinicians at two facilities. Dr. Andrews said the facility gives out lockboxes for weapons and medication to the public – including parents who come in after children attempted to take their life using medication.

Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., also has experienced an uptick, said Colby Tyson, MD, associate director of inpatient psychiatry. She’s seen children’s mental health deteriorate because of a likely increase in family conflict – often a consequence of the chaos caused by the pandemic. Without school, connections with peers or employment, families don’t have the opportunity to spend time away from one another and regroup, which can add stress to an already tense situation.

“That break is gone,” she said.

The higher demand for child mental health services caused by the pandemic has made finding a bed at an inpatient unit more difficult.

Now, some hospitals report running at full capacity and having more children “boarding,” or sleeping in EDs before being admitted to the psychiatric unit. Among them is the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado. Williams said the inpatient unit has been full since March. Some children now wait nearly 2 days for a bed, up from the 8-10 hours common before the pandemic.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio is also running at full capacity, said clinicians, and had several days in which the unit was above capacity and placed kids instead in the emergency department waiting to be admitted. In Florida, Dr. Andrews said, up to 25 children have been held on surgical floors at Wolfson Children’s while waiting for a spot to open in the inpatient psychiatric unit. Their wait could last as long as 5 days, she said.

Multiple hospitals said the usual summer slump in child psychiatric admissions was missing last year. “We never saw that during the pandemic,” said Andrews. “We stayed completely busy the entire time.”

Some facilities have decided to reduce the number of beds available to maintain physical distancing, further constricting supply. Children’s National in D.C. cut five beds from its unit to maintain single occupancy in every room, said Adelaide Robb, MD, division chief of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

The measures taken to curb the spread of COVID have also affected the way hospitalized children receive mental health services. In addition to providers wearing protective equipment, some hospitals like Cincinnati Children’s rearranged furniture and placed cues on the floor as reminders to stay 6 feet apart. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Western Psychiatric Hospital and other facilities encourage children to keep their masks on by offering rewards like extra computer time. Patients at Children’s National now eat in their rooms, a change from when they ate together.

Despite the need for distance, social interaction still represents an important part of mental health care for children, clinicians said. Facilities have come up with various ways to do so safely, including creating smaller pods for group therapy. Children at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital can play with toys, but only with ones that can be wiped clean afterward. No cards or board games, said Suzanne Sampang, MD, clinical medical director for child and adolescent psychiatry at the hospital.

“I think what’s different about psychiatric treatment is that, really, interaction is the treatment,” she said, “just as much as a medication.”

The added infection-control precautions pose challenges to forging therapeutic connections. Masks can complicate the ability to read a person’s face. Online meetings make it difficult to build trust between a patient and a therapist.

“There’s something about the real relationship in person that the best technology can’t give to you,” said Dr. Robb.

For now, Krissy Williams is relying on virtual platforms to receive some of her mental health services. Despite being hospitalized and suffering brain damage due to the overdose, she is now at home and in good spirits. She enjoys geometry, dancing on TikTok, and trying to beat her mother at Super Mario Bros. on the Wii. But being away from her friends, she said, has been a hard adjustment.

“When you’re used to something,” she said, “it’s not easy to change everything.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Krissy Williams, 15, had attempted suicide before, but never with pills.

The teen was diagnosed with schizophrenia when she was 9. People with this chronic mental health condition perceive reality differently and often experience hallucinations and delusions. She learned to manage these symptoms with a variety of services offered at home and at school.

But the pandemic upended those lifelines. She lost much of the support offered at school. She also lost regular contact with her peers. Her mother lost access to respite care – which allowed her to take a break.

On a Thursday in October, the isolation and sadness came to a head. As Krissy’s mother, Patricia Williams, called a mental crisis hotline for help, she said, Krissy stood on the deck of their Maryland home with a bottle of pain medication in one hand and water in the other.

Before Patricia could react, Krissy placed the pills in her mouth and swallowed.

Efforts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus in the United States have led to drastic changes in the way children and teens learn, play and socialize. Tens of millions of students are attending school through some form of distance learning. Many extracurricular activities have been canceled. Playgrounds, zoos, and other recreational spaces have closed. Kids like Krissy have struggled to cope and the toll is becoming evident.

Government figures show the proportion of children who arrived in EDs with mental health issues increased 24% from mid-March through mid-October, compared with the same period in 2019. Among preteens and adolescents, it rose by 31%. Anecdotally, some hospitals said they are seeing more cases of severe depression and suicidal thoughts among children, particularly attempts to overdose.

The increased demand for intensive mental health care that has accompanied the pandemic has worsened issues that have long plagued the system. In some hospitals, the number of children unable to immediately get a bed in the psychiatric unit rose. Others reduced the number of beds or closed psychiatric units altogether to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

“It’s only a matter of time before a tsunami sort of reaches the shore of our service system, and it’s going to be overwhelmed with the mental health needs of kids,” said Jason Williams, PsyD, a psychologist and director of operations of the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

“I think we’re just starting to see the tip of the iceberg, to be honest with you.”

Before COVID, more than 8 million kids between ages 3 and 17 were diagnosed with a mental or behavioral health condition, according to the most recent National Survey of Children’s Health. A separate survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found one in three high school students in 2019 reported feeling persistently sad and hopeless – a 40% increase from 2009.

The coronavirus pandemic appears to be adding to these difficulties. A review of 80 studies found forced isolation and loneliness among children correlated with an increased risk of depression.

“We’re all social beings, but they’re [teenagers] at the point in their development where their peers are their reality,” said Terrie Andrews, PhD, a psychologist and administrator of behavioral health at Wolfson Children’s Hospital in Jacksonville, Fla. “Their peers are their grounding mechanism.”

Children’s hospitals in Colorado, Missouri, and New York all reported an uptick in the number of patients who thought about or attempted suicide. Clinicians also mentioned spikes in children with severe depression and those with autism who are acting out.

The number of overdose attempts among children has caught the attention of clinicians at two facilities. Dr. Andrews said the facility gives out lockboxes for weapons and medication to the public – including parents who come in after children attempted to take their life using medication.

Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., also has experienced an uptick, said Colby Tyson, MD, associate director of inpatient psychiatry. She’s seen children’s mental health deteriorate because of a likely increase in family conflict – often a consequence of the chaos caused by the pandemic. Without school, connections with peers or employment, families don’t have the opportunity to spend time away from one another and regroup, which can add stress to an already tense situation.

“That break is gone,” she said.

The higher demand for child mental health services caused by the pandemic has made finding a bed at an inpatient unit more difficult.

Now, some hospitals report running at full capacity and having more children “boarding,” or sleeping in EDs before being admitted to the psychiatric unit. Among them is the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado. Williams said the inpatient unit has been full since March. Some children now wait nearly 2 days for a bed, up from the 8-10 hours common before the pandemic.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio is also running at full capacity, said clinicians, and had several days in which the unit was above capacity and placed kids instead in the emergency department waiting to be admitted. In Florida, Dr. Andrews said, up to 25 children have been held on surgical floors at Wolfson Children’s while waiting for a spot to open in the inpatient psychiatric unit. Their wait could last as long as 5 days, she said.

Multiple hospitals said the usual summer slump in child psychiatric admissions was missing last year. “We never saw that during the pandemic,” said Andrews. “We stayed completely busy the entire time.”

Some facilities have decided to reduce the number of beds available to maintain physical distancing, further constricting supply. Children’s National in D.C. cut five beds from its unit to maintain single occupancy in every room, said Adelaide Robb, MD, division chief of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

The measures taken to curb the spread of COVID have also affected the way hospitalized children receive mental health services. In addition to providers wearing protective equipment, some hospitals like Cincinnati Children’s rearranged furniture and placed cues on the floor as reminders to stay 6 feet apart. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Western Psychiatric Hospital and other facilities encourage children to keep their masks on by offering rewards like extra computer time. Patients at Children’s National now eat in their rooms, a change from when they ate together.

Despite the need for distance, social interaction still represents an important part of mental health care for children, clinicians said. Facilities have come up with various ways to do so safely, including creating smaller pods for group therapy. Children at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital can play with toys, but only with ones that can be wiped clean afterward. No cards or board games, said Suzanne Sampang, MD, clinical medical director for child and adolescent psychiatry at the hospital.

“I think what’s different about psychiatric treatment is that, really, interaction is the treatment,” she said, “just as much as a medication.”

The added infection-control precautions pose challenges to forging therapeutic connections. Masks can complicate the ability to read a person’s face. Online meetings make it difficult to build trust between a patient and a therapist.

“There’s something about the real relationship in person that the best technology can’t give to you,” said Dr. Robb.

For now, Krissy Williams is relying on virtual platforms to receive some of her mental health services. Despite being hospitalized and suffering brain damage due to the overdose, she is now at home and in good spirits. She enjoys geometry, dancing on TikTok, and trying to beat her mother at Super Mario Bros. on the Wii. But being away from her friends, she said, has been a hard adjustment.

“When you’re used to something,” she said, “it’s not easy to change everything.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Krissy Williams, 15, had attempted suicide before, but never with pills.

The teen was diagnosed with schizophrenia when she was 9. People with this chronic mental health condition perceive reality differently and often experience hallucinations and delusions. She learned to manage these symptoms with a variety of services offered at home and at school.

But the pandemic upended those lifelines. She lost much of the support offered at school. She also lost regular contact with her peers. Her mother lost access to respite care – which allowed her to take a break.

On a Thursday in October, the isolation and sadness came to a head. As Krissy’s mother, Patricia Williams, called a mental crisis hotline for help, she said, Krissy stood on the deck of their Maryland home with a bottle of pain medication in one hand and water in the other.

Before Patricia could react, Krissy placed the pills in her mouth and swallowed.

Efforts to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus in the United States have led to drastic changes in the way children and teens learn, play and socialize. Tens of millions of students are attending school through some form of distance learning. Many extracurricular activities have been canceled. Playgrounds, zoos, and other recreational spaces have closed. Kids like Krissy have struggled to cope and the toll is becoming evident.

Government figures show the proportion of children who arrived in EDs with mental health issues increased 24% from mid-March through mid-October, compared with the same period in 2019. Among preteens and adolescents, it rose by 31%. Anecdotally, some hospitals said they are seeing more cases of severe depression and suicidal thoughts among children, particularly attempts to overdose.

The increased demand for intensive mental health care that has accompanied the pandemic has worsened issues that have long plagued the system. In some hospitals, the number of children unable to immediately get a bed in the psychiatric unit rose. Others reduced the number of beds or closed psychiatric units altogether to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

“It’s only a matter of time before a tsunami sort of reaches the shore of our service system, and it’s going to be overwhelmed with the mental health needs of kids,” said Jason Williams, PsyD, a psychologist and director of operations of the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

“I think we’re just starting to see the tip of the iceberg, to be honest with you.”

Before COVID, more than 8 million kids between ages 3 and 17 were diagnosed with a mental or behavioral health condition, according to the most recent National Survey of Children’s Health. A separate survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found one in three high school students in 2019 reported feeling persistently sad and hopeless – a 40% increase from 2009.

The coronavirus pandemic appears to be adding to these difficulties. A review of 80 studies found forced isolation and loneliness among children correlated with an increased risk of depression.

“We’re all social beings, but they’re [teenagers] at the point in their development where their peers are their reality,” said Terrie Andrews, PhD, a psychologist and administrator of behavioral health at Wolfson Children’s Hospital in Jacksonville, Fla. “Their peers are their grounding mechanism.”

Children’s hospitals in Colorado, Missouri, and New York all reported an uptick in the number of patients who thought about or attempted suicide. Clinicians also mentioned spikes in children with severe depression and those with autism who are acting out.

The number of overdose attempts among children has caught the attention of clinicians at two facilities. Dr. Andrews said the facility gives out lockboxes for weapons and medication to the public – including parents who come in after children attempted to take their life using medication.

Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., also has experienced an uptick, said Colby Tyson, MD, associate director of inpatient psychiatry. She’s seen children’s mental health deteriorate because of a likely increase in family conflict – often a consequence of the chaos caused by the pandemic. Without school, connections with peers or employment, families don’t have the opportunity to spend time away from one another and regroup, which can add stress to an already tense situation.

“That break is gone,” she said.

The higher demand for child mental health services caused by the pandemic has made finding a bed at an inpatient unit more difficult.

Now, some hospitals report running at full capacity and having more children “boarding,” or sleeping in EDs before being admitted to the psychiatric unit. Among them is the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado. Williams said the inpatient unit has been full since March. Some children now wait nearly 2 days for a bed, up from the 8-10 hours common before the pandemic.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio is also running at full capacity, said clinicians, and had several days in which the unit was above capacity and placed kids instead in the emergency department waiting to be admitted. In Florida, Dr. Andrews said, up to 25 children have been held on surgical floors at Wolfson Children’s while waiting for a spot to open in the inpatient psychiatric unit. Their wait could last as long as 5 days, she said.

Multiple hospitals said the usual summer slump in child psychiatric admissions was missing last year. “We never saw that during the pandemic,” said Andrews. “We stayed completely busy the entire time.”

Some facilities have decided to reduce the number of beds available to maintain physical distancing, further constricting supply. Children’s National in D.C. cut five beds from its unit to maintain single occupancy in every room, said Adelaide Robb, MD, division chief of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

The measures taken to curb the spread of COVID have also affected the way hospitalized children receive mental health services. In addition to providers wearing protective equipment, some hospitals like Cincinnati Children’s rearranged furniture and placed cues on the floor as reminders to stay 6 feet apart. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Western Psychiatric Hospital and other facilities encourage children to keep their masks on by offering rewards like extra computer time. Patients at Children’s National now eat in their rooms, a change from when they ate together.

Despite the need for distance, social interaction still represents an important part of mental health care for children, clinicians said. Facilities have come up with various ways to do so safely, including creating smaller pods for group therapy. Children at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital can play with toys, but only with ones that can be wiped clean afterward. No cards or board games, said Suzanne Sampang, MD, clinical medical director for child and adolescent psychiatry at the hospital.

“I think what’s different about psychiatric treatment is that, really, interaction is the treatment,” she said, “just as much as a medication.”

The added infection-control precautions pose challenges to forging therapeutic connections. Masks can complicate the ability to read a person’s face. Online meetings make it difficult to build trust between a patient and a therapist.

“There’s something about the real relationship in person that the best technology can’t give to you,” said Dr. Robb.

For now, Krissy Williams is relying on virtual platforms to receive some of her mental health services. Despite being hospitalized and suffering brain damage due to the overdose, she is now at home and in good spirits. She enjoys geometry, dancing on TikTok, and trying to beat her mother at Super Mario Bros. on the Wii. But being away from her friends, she said, has been a hard adjustment.

“When you’re used to something,” she said, “it’s not easy to change everything.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Dupilumab curbed itch intensity, frequency in children with severe eczema

.

The findings come from a post hoc analysis of a phase 3 trial known as LIBERTY AD PEDS (NCT03345914) that Gil Yosipovitch, MD, presented during a late-breaking research session at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium.

“Severe AD is complex, highly symptomatic, multidimensional condition characterized by an intense pruritus that negatively impacts a patient’s life,” said Dr. Yosipovitch, professor of dermatology and director of the Miami Itch Center at the University of Miami. Published data from the double-blind, placebo-controlled, 16-week, LIBERTY AD PEDS trial in children aged 6–11 years with severe AD showed that dupilumab significantly improved AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life, with an acceptable safety profile (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;21:119-31).

For the current analysis, Dr. Yosipovitch and colleagues evaluated the time to onset, magnitude, and sustainability of the effect of dupilumab on different measures of itch using data from approved Food and Drug Administration doses studied in the LIBERTY AD PEDS trial. A total of 243 children aged 6-11 years were randomized to dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks (300 mg q4w, baseline weight of less than 30 kg; 600-mg loading dose), 200 mg every 2 weeks (200 mg q2w, baseline weight 30 kg or greater; 400-mg loading dose), or placebo. All patients received concomitant medium-potency topical corticosteroids.

The mean age of patients was 8.4 years and those in the 300-mg q4w group were about 2 years younger than those in the 200-mg q2w group. On the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), the researchers observed that treatment with dupilumab was associated with a significant improvement from baseline in daily worst itch score through day 22 in the 300-mg q4w group and the 200-mg q2w group, compared with placebo (–29% vs. –30%, respectively; P less than or equal to .001 and P less than or equal to .05). Treatment with dupilumab was also associated with a significant improvement from baseline in weekly average of daily worst itch score through week 16, compared with placebo (–55% vs. –58%; P less than or equal to .001). Similarly, a higher daily proportion of dupilumab-treated patients achieved a 2-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (51% vs. 49%; P less than or equal to .001 and P less than or equal to .05). The same association held true for the daily proportion of dupilumab-treated patients who achieved a 4-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (21% in both groups; P less than or equal to .05).

By week 16, a higher weekly proportion of dupilumab-treated patients achieved a 2-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (72% in the 300-mg q4w group vs. 74% in the 200-mg q2w group; P less than or equal to .001). The same association held true for the daily proportion of dupilumab-treated patients who achieved a 4-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (54% vs. 61%; P less than or equal to .001).

Next, the researchers evaluated the proportion of patients reporting the number of days with itchy skin over the previous 7 days as assessed from the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) itch item question: “Over the last week, on how many days has your child’s skin been itchy because of their eczema?” By week 16, the majority of children treated with dupilumab achieved a reduction of days experiencing itch from every day at baseline to at most 2 days, with some improvement to zero days per week.

“Overall, in the LIBERTY AD PEDS trial, dupilumab was well tolerated and data were consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile observed in adults and adolescents,” Dr. Yosipovitch said. “Injection site reactions and conjunctivitis were more common with dupilumab. Infections and AD exacerbations were more common with placebo.”

The study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Yosipovitch and coauthors reporting having received financial grants and research grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

.

The findings come from a post hoc analysis of a phase 3 trial known as LIBERTY AD PEDS (NCT03345914) that Gil Yosipovitch, MD, presented during a late-breaking research session at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium.

“Severe AD is complex, highly symptomatic, multidimensional condition characterized by an intense pruritus that negatively impacts a patient’s life,” said Dr. Yosipovitch, professor of dermatology and director of the Miami Itch Center at the University of Miami. Published data from the double-blind, placebo-controlled, 16-week, LIBERTY AD PEDS trial in children aged 6–11 years with severe AD showed that dupilumab significantly improved AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life, with an acceptable safety profile (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;21:119-31).

For the current analysis, Dr. Yosipovitch and colleagues evaluated the time to onset, magnitude, and sustainability of the effect of dupilumab on different measures of itch using data from approved Food and Drug Administration doses studied in the LIBERTY AD PEDS trial. A total of 243 children aged 6-11 years were randomized to dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks (300 mg q4w, baseline weight of less than 30 kg; 600-mg loading dose), 200 mg every 2 weeks (200 mg q2w, baseline weight 30 kg or greater; 400-mg loading dose), or placebo. All patients received concomitant medium-potency topical corticosteroids.

The mean age of patients was 8.4 years and those in the 300-mg q4w group were about 2 years younger than those in the 200-mg q2w group. On the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), the researchers observed that treatment with dupilumab was associated with a significant improvement from baseline in daily worst itch score through day 22 in the 300-mg q4w group and the 200-mg q2w group, compared with placebo (–29% vs. –30%, respectively; P less than or equal to .001 and P less than or equal to .05). Treatment with dupilumab was also associated with a significant improvement from baseline in weekly average of daily worst itch score through week 16, compared with placebo (–55% vs. –58%; P less than or equal to .001). Similarly, a higher daily proportion of dupilumab-treated patients achieved a 2-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (51% vs. 49%; P less than or equal to .001 and P less than or equal to .05). The same association held true for the daily proportion of dupilumab-treated patients who achieved a 4-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (21% in both groups; P less than or equal to .05).

By week 16, a higher weekly proportion of dupilumab-treated patients achieved a 2-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (72% in the 300-mg q4w group vs. 74% in the 200-mg q2w group; P less than or equal to .001). The same association held true for the daily proportion of dupilumab-treated patients who achieved a 4-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (54% vs. 61%; P less than or equal to .001).

Next, the researchers evaluated the proportion of patients reporting the number of days with itchy skin over the previous 7 days as assessed from the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) itch item question: “Over the last week, on how many days has your child’s skin been itchy because of their eczema?” By week 16, the majority of children treated with dupilumab achieved a reduction of days experiencing itch from every day at baseline to at most 2 days, with some improvement to zero days per week.

“Overall, in the LIBERTY AD PEDS trial, dupilumab was well tolerated and data were consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile observed in adults and adolescents,” Dr. Yosipovitch said. “Injection site reactions and conjunctivitis were more common with dupilumab. Infections and AD exacerbations were more common with placebo.”

The study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Yosipovitch and coauthors reporting having received financial grants and research grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

.

The findings come from a post hoc analysis of a phase 3 trial known as LIBERTY AD PEDS (NCT03345914) that Gil Yosipovitch, MD, presented during a late-breaking research session at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium.

“Severe AD is complex, highly symptomatic, multidimensional condition characterized by an intense pruritus that negatively impacts a patient’s life,” said Dr. Yosipovitch, professor of dermatology and director of the Miami Itch Center at the University of Miami. Published data from the double-blind, placebo-controlled, 16-week, LIBERTY AD PEDS trial in children aged 6–11 years with severe AD showed that dupilumab significantly improved AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life, with an acceptable safety profile (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;21:119-31).

For the current analysis, Dr. Yosipovitch and colleagues evaluated the time to onset, magnitude, and sustainability of the effect of dupilumab on different measures of itch using data from approved Food and Drug Administration doses studied in the LIBERTY AD PEDS trial. A total of 243 children aged 6-11 years were randomized to dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks (300 mg q4w, baseline weight of less than 30 kg; 600-mg loading dose), 200 mg every 2 weeks (200 mg q2w, baseline weight 30 kg or greater; 400-mg loading dose), or placebo. All patients received concomitant medium-potency topical corticosteroids.

The mean age of patients was 8.4 years and those in the 300-mg q4w group were about 2 years younger than those in the 200-mg q2w group. On the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), the researchers observed that treatment with dupilumab was associated with a significant improvement from baseline in daily worst itch score through day 22 in the 300-mg q4w group and the 200-mg q2w group, compared with placebo (–29% vs. –30%, respectively; P less than or equal to .001 and P less than or equal to .05). Treatment with dupilumab was also associated with a significant improvement from baseline in weekly average of daily worst itch score through week 16, compared with placebo (–55% vs. –58%; P less than or equal to .001). Similarly, a higher daily proportion of dupilumab-treated patients achieved a 2-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (51% vs. 49%; P less than or equal to .001 and P less than or equal to .05). The same association held true for the daily proportion of dupilumab-treated patients who achieved a 4-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (21% in both groups; P less than or equal to .05).

By week 16, a higher weekly proportion of dupilumab-treated patients achieved a 2-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (72% in the 300-mg q4w group vs. 74% in the 200-mg q2w group; P less than or equal to .001). The same association held true for the daily proportion of dupilumab-treated patients who achieved a 4-point or more improvement in worst itch score, compared with placebo (54% vs. 61%; P less than or equal to .001).

Next, the researchers evaluated the proportion of patients reporting the number of days with itchy skin over the previous 7 days as assessed from the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) itch item question: “Over the last week, on how many days has your child’s skin been itchy because of their eczema?” By week 16, the majority of children treated with dupilumab achieved a reduction of days experiencing itch from every day at baseline to at most 2 days, with some improvement to zero days per week.

“Overall, in the LIBERTY AD PEDS trial, dupilumab was well tolerated and data were consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile observed in adults and adolescents,” Dr. Yosipovitch said. “Injection site reactions and conjunctivitis were more common with dupilumab. Infections and AD exacerbations were more common with placebo.”

The study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Yosipovitch and coauthors reporting having received financial grants and research grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM REVOLUTIONIZING AD 2020

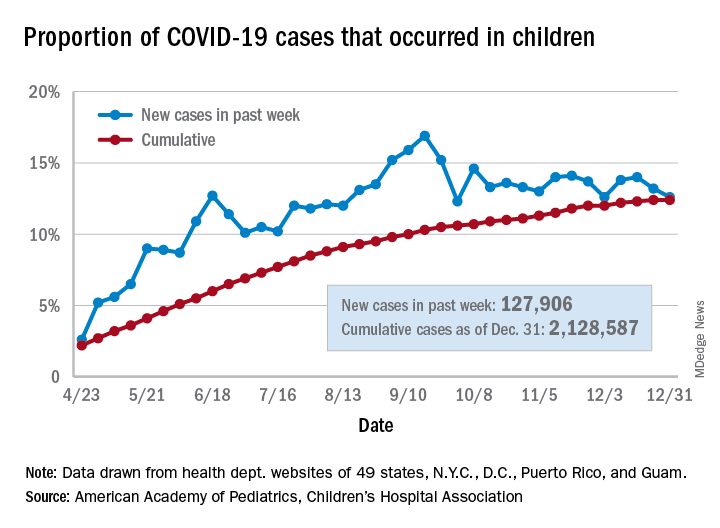

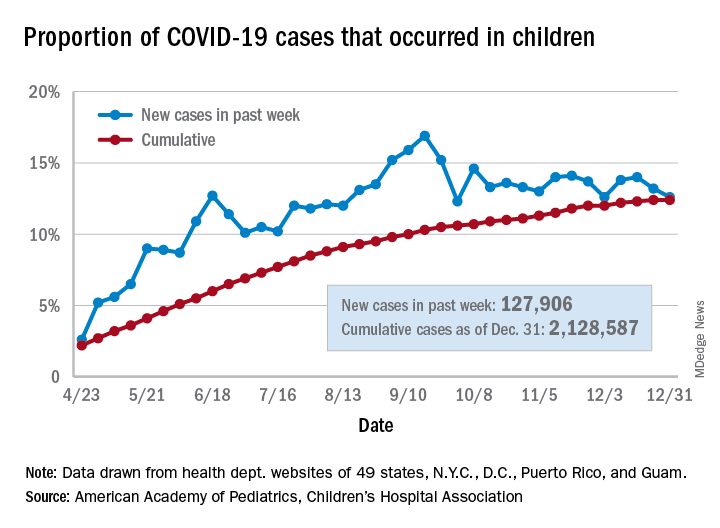

Study confirms key COVID-19 risk factors in children

Children and adolescents who receive positive COVID-19 test results are not only more likely to have been in close contact with someone with a confirmed case of the virus but also are less likely to have reported consistent mask use among students and staff inside the school they attended, reported Charlotte V. Hobbs, MD, and colleagues at the University of Mississippi, Jackson.

In partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Response Team, Dr. Hobbs and colleagues conducted a case-control study of 397 children and adolescents under 18 years of age to assess school, community, and close contact exposures associated with pediatric COVID-19. Patients tested for COVID-19 at outpatient health centers or emergency departments affiliated with the University of Mississippi Medical Center between Sept. 1 and Nov. 5, 2020, were included in the study.

Nearly two-thirds reported that exposure came from family members

Of the total study participants observed, 82 (21%) were under 4 years of age; 214 (54%) were female; 217 (55%) were non-Hispanic black, and 145 (37%) were non-Hispanic white. More than half (53%) sought testing because of COVID-19 symptoms. Of those who tested positive, 66% reported having come into close contact with a COVID-19 case, and 64% reported that those contacts were family members, compared with 15% of contacts who were schoolmates and 27% who were child care classmates.

All participants completed in-person school or child care attendance less than 14 days before testing positive for the virus, including 62% of patients testing positive and 68% of those testing negative. The authors noted that school attendance itself was not found to be associated with any positive test results. In fact, parents in 64% of positive cases and 76% of negative cases reported mask wearing among children and staff inside places of learning.

Of those study participants testing positive who did come into close contact with someone with COVID-19, the contacts were more likely to be family members than school or child care classmates. Specifically, they were more likely, in the 2-week period preceding testing, to have attended gatherings with individuals outside their immediate households, including social events and activities with other children. Parents of students testing positive were also less likely to report consistent indoor mask use among their children older than 2 years and school staff members.

School attendance was not found to increase likelihood of testing positive

Attending in-person school or child care during the 2 weeks before the SARS-CoV-2 test was not associated with greater likelihood of testing positive, the study authors noted, adding that the majority of study respondents reported universal mask use inside school and child care facilities, consistent with Mississippi State Department of Health recommended guidelines.

Dr. Hobbs and colleagues reported at least four limitations of the study. They noted that the study participants may not be representative of youth in other geographic regions of the country. They considered the possibility of unmeasured confounding of participant behaviors that may not have been factored into the study. No attempt was made to verify parent claims of mask use at schools and child care programs. Lastly, they acknowledged that “case or control status might be subject to misclassification because of imperfect sensitivity or specificity of PCR-based testing.

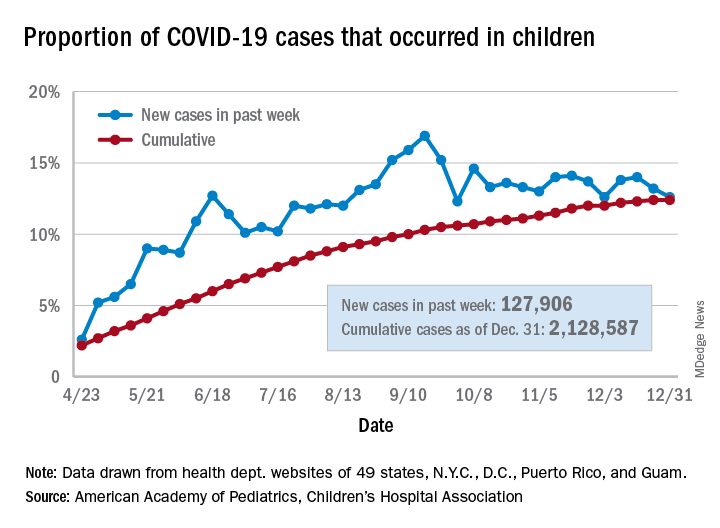

As of Dec. 14, 2020, the CDC reported that 10.2% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States were in children and adolescents under the age of 18.

“Continued efforts to prevent transmission at schools and child care programs are important, as are assessments of various types of activities and exposures to identify risk factors for COVID-19 as children engage in classroom and social interactions.” Promoting behaviors to reduce exposures to the virus among youth in the household, the community, schools, and child care programs is important to preventing outbreaks of the virus at schools, the authors cautioned.

In a separate interview with this news organization, Karalyn Kinsella, MD, general pediatrician in a small group private practice in Cheshire, Conn., said, “What this report tells me is that COVID cases are more common when mask use is inconsistent in schools and at home and in schools that don’t properly adhere to CDC guidelines. Overall, so long as social distancing guidelines are followed, schools are pretty safe places for kids during this pandemic.”

This finding is important, since many families are keeping their children out of school over fears of contracting the virus, she added. Some of the consequences these children are suffering include a lack of social connection and structure, which in some cases is leading to worsening anxiety and depression, and for those with disabilities, such as those who receive physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech or have IEPs, they’re not getting the full benefit of the services that they would otherwise receive in person, she observed.

“I don’t think families really understand the risks of getting together with family or friends “in their bubble” or the risk of continuing sports participation. This is where the majority of COVID cases are coming from,” she said, adding that it is important to discuss this risk with them at appointments. So, when families ask us what we think of in-person learning, I think we should feel fairly confident that the benefit may outweigh the risk.”

Dr. Hobbs and colleagues, and Dr. Kinsella, had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1925-9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950e3.

Children and adolescents who receive positive COVID-19 test results are not only more likely to have been in close contact with someone with a confirmed case of the virus but also are less likely to have reported consistent mask use among students and staff inside the school they attended, reported Charlotte V. Hobbs, MD, and colleagues at the University of Mississippi, Jackson.

In partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Response Team, Dr. Hobbs and colleagues conducted a case-control study of 397 children and adolescents under 18 years of age to assess school, community, and close contact exposures associated with pediatric COVID-19. Patients tested for COVID-19 at outpatient health centers or emergency departments affiliated with the University of Mississippi Medical Center between Sept. 1 and Nov. 5, 2020, were included in the study.

Nearly two-thirds reported that exposure came from family members

Of the total study participants observed, 82 (21%) were under 4 years of age; 214 (54%) were female; 217 (55%) were non-Hispanic black, and 145 (37%) were non-Hispanic white. More than half (53%) sought testing because of COVID-19 symptoms. Of those who tested positive, 66% reported having come into close contact with a COVID-19 case, and 64% reported that those contacts were family members, compared with 15% of contacts who were schoolmates and 27% who were child care classmates.

All participants completed in-person school or child care attendance less than 14 days before testing positive for the virus, including 62% of patients testing positive and 68% of those testing negative. The authors noted that school attendance itself was not found to be associated with any positive test results. In fact, parents in 64% of positive cases and 76% of negative cases reported mask wearing among children and staff inside places of learning.

Of those study participants testing positive who did come into close contact with someone with COVID-19, the contacts were more likely to be family members than school or child care classmates. Specifically, they were more likely, in the 2-week period preceding testing, to have attended gatherings with individuals outside their immediate households, including social events and activities with other children. Parents of students testing positive were also less likely to report consistent indoor mask use among their children older than 2 years and school staff members.

School attendance was not found to increase likelihood of testing positive

Attending in-person school or child care during the 2 weeks before the SARS-CoV-2 test was not associated with greater likelihood of testing positive, the study authors noted, adding that the majority of study respondents reported universal mask use inside school and child care facilities, consistent with Mississippi State Department of Health recommended guidelines.

Dr. Hobbs and colleagues reported at least four limitations of the study. They noted that the study participants may not be representative of youth in other geographic regions of the country. They considered the possibility of unmeasured confounding of participant behaviors that may not have been factored into the study. No attempt was made to verify parent claims of mask use at schools and child care programs. Lastly, they acknowledged that “case or control status might be subject to misclassification because of imperfect sensitivity or specificity of PCR-based testing.

As of Dec. 14, 2020, the CDC reported that 10.2% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States were in children and adolescents under the age of 18.

“Continued efforts to prevent transmission at schools and child care programs are important, as are assessments of various types of activities and exposures to identify risk factors for COVID-19 as children engage in classroom and social interactions.” Promoting behaviors to reduce exposures to the virus among youth in the household, the community, schools, and child care programs is important to preventing outbreaks of the virus at schools, the authors cautioned.

In a separate interview with this news organization, Karalyn Kinsella, MD, general pediatrician in a small group private practice in Cheshire, Conn., said, “What this report tells me is that COVID cases are more common when mask use is inconsistent in schools and at home and in schools that don’t properly adhere to CDC guidelines. Overall, so long as social distancing guidelines are followed, schools are pretty safe places for kids during this pandemic.”

This finding is important, since many families are keeping their children out of school over fears of contracting the virus, she added. Some of the consequences these children are suffering include a lack of social connection and structure, which in some cases is leading to worsening anxiety and depression, and for those with disabilities, such as those who receive physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech or have IEPs, they’re not getting the full benefit of the services that they would otherwise receive in person, she observed.

“I don’t think families really understand the risks of getting together with family or friends “in their bubble” or the risk of continuing sports participation. This is where the majority of COVID cases are coming from,” she said, adding that it is important to discuss this risk with them at appointments. So, when families ask us what we think of in-person learning, I think we should feel fairly confident that the benefit may outweigh the risk.”

Dr. Hobbs and colleagues, and Dr. Kinsella, had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1925-9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950e3.

Children and adolescents who receive positive COVID-19 test results are not only more likely to have been in close contact with someone with a confirmed case of the virus but also are less likely to have reported consistent mask use among students and staff inside the school they attended, reported Charlotte V. Hobbs, MD, and colleagues at the University of Mississippi, Jackson.

In partnership with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Response Team, Dr. Hobbs and colleagues conducted a case-control study of 397 children and adolescents under 18 years of age to assess school, community, and close contact exposures associated with pediatric COVID-19. Patients tested for COVID-19 at outpatient health centers or emergency departments affiliated with the University of Mississippi Medical Center between Sept. 1 and Nov. 5, 2020, were included in the study.

Nearly two-thirds reported that exposure came from family members

Of the total study participants observed, 82 (21%) were under 4 years of age; 214 (54%) were female; 217 (55%) were non-Hispanic black, and 145 (37%) were non-Hispanic white. More than half (53%) sought testing because of COVID-19 symptoms. Of those who tested positive, 66% reported having come into close contact with a COVID-19 case, and 64% reported that those contacts were family members, compared with 15% of contacts who were schoolmates and 27% who were child care classmates.

All participants completed in-person school or child care attendance less than 14 days before testing positive for the virus, including 62% of patients testing positive and 68% of those testing negative. The authors noted that school attendance itself was not found to be associated with any positive test results. In fact, parents in 64% of positive cases and 76% of negative cases reported mask wearing among children and staff inside places of learning.

Of those study participants testing positive who did come into close contact with someone with COVID-19, the contacts were more likely to be family members than school or child care classmates. Specifically, they were more likely, in the 2-week period preceding testing, to have attended gatherings with individuals outside their immediate households, including social events and activities with other children. Parents of students testing positive were also less likely to report consistent indoor mask use among their children older than 2 years and school staff members.

School attendance was not found to increase likelihood of testing positive

Attending in-person school or child care during the 2 weeks before the SARS-CoV-2 test was not associated with greater likelihood of testing positive, the study authors noted, adding that the majority of study respondents reported universal mask use inside school and child care facilities, consistent with Mississippi State Department of Health recommended guidelines.

Dr. Hobbs and colleagues reported at least four limitations of the study. They noted that the study participants may not be representative of youth in other geographic regions of the country. They considered the possibility of unmeasured confounding of participant behaviors that may not have been factored into the study. No attempt was made to verify parent claims of mask use at schools and child care programs. Lastly, they acknowledged that “case or control status might be subject to misclassification because of imperfect sensitivity or specificity of PCR-based testing.

As of Dec. 14, 2020, the CDC reported that 10.2% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States were in children and adolescents under the age of 18.

“Continued efforts to prevent transmission at schools and child care programs are important, as are assessments of various types of activities and exposures to identify risk factors for COVID-19 as children engage in classroom and social interactions.” Promoting behaviors to reduce exposures to the virus among youth in the household, the community, schools, and child care programs is important to preventing outbreaks of the virus at schools, the authors cautioned.

In a separate interview with this news organization, Karalyn Kinsella, MD, general pediatrician in a small group private practice in Cheshire, Conn., said, “What this report tells me is that COVID cases are more common when mask use is inconsistent in schools and at home and in schools that don’t properly adhere to CDC guidelines. Overall, so long as social distancing guidelines are followed, schools are pretty safe places for kids during this pandemic.”

This finding is important, since many families are keeping their children out of school over fears of contracting the virus, she added. Some of the consequences these children are suffering include a lack of social connection and structure, which in some cases is leading to worsening anxiety and depression, and for those with disabilities, such as those who receive physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech or have IEPs, they’re not getting the full benefit of the services that they would otherwise receive in person, she observed.

“I don’t think families really understand the risks of getting together with family or friends “in their bubble” or the risk of continuing sports participation. This is where the majority of COVID cases are coming from,” she said, adding that it is important to discuss this risk with them at appointments. So, when families ask us what we think of in-person learning, I think we should feel fairly confident that the benefit may outweigh the risk.”

Dr. Hobbs and colleagues, and Dr. Kinsella, had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1925-9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950e3.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

IDSA panel updates guidelines on COVID molecular diagnostic tests

Saliva spit tests stack up well against the gold standard for molecular COVID-19 tests – the back-of-the-nose deep swab – without the discomfort and induced coughing or sneezing of the test taker, updated guidelines indicate.

In a press briefing on Jan. 6, the Infectious Diseases Society of America explained the findings of an expert panel that reviewed the literature since the IDSA released its first guidelines in May.

The panel found that saliva tests were especially effective if the test included instructions to cough or clear the throat before spitting into the tube, said panel chair Kimberly E. Hanson, MD, MHS, of University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City.

Throat swab alone less effective

Using a throat swab alone was less effective and missed more cases than the other methods, she said.

The IDSA has updated its recommendation: A saliva test or swabs from either the middle or front of the nose front are preferred to a throat swab alone.

A combination of saliva and swabs from the front and middle of the nose and throat together “looked pretty much equivalent” to the gold-standard deep swab, the panel found.

She acknowledged, however, that multiple swabs exacerbate already challenging supply issues.

Saliva samples do come with challenges, Dr. Hanson noted. A laboratory must validate that its systems can handle the stickier material. And asking a patient to cough necessitates more personal protective equipment for the health care professional.

Each center will have to tailor the specimen type it chooses, based on what resources it has available and the setting – whether in a hospital or a drive-through operation, for instance, she said.

Rapid testing vs. standard

Panel member Angela M. Caliendo, MD, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., said the panel preferred rapid polymerase chain reaction tests and standard, laboratory-based PCR tests over a rapid isothermal test.

The panel defined rapid tests as those for which results are available within an hour after a test provider has the specimen in hand. They excluded home tests for this category.

The only rapid isothermal test that had enough data on which to issue a recommendation was the ID NOW test (Abbott Labs), she noted.

Rapid PCR tests performed just as well as the standard laboratory-based tests, she said, with a high sensitivity of “97% on average and a very high specificity.”

But the rapid isothermal test had an average sensitivity of only about 80%, compared with the lab-based PCR test, Dr. Caliendo said, yielding a substantial number of false-negative results.

Testing centers will have to weigh the considerable advantages of having results in 15 minutes with a rapid isothermal test and being able to educate positive patients about immediate isolation against the potential for false negatives, which could send positive patients home thinking they don’t have the virus – and thus potentially spreading the disease.

And if a clinician gets a negative result with the rapid isothermal test, but has a strong suspicion the person has COVID or lives in an area with high prevalence, a backup test with a rapid PCR or laboratory-based test should be administered.

“You will miss a certain percentage of people using this rapid isothermal test,” she said.

However, Dr. Caliendo said, if the only available option is the isothermal test, “you should definitely use it because it’s certainly better than not testing at all.”

On a positive note, she said, all the varieties of tests have high specificity, so “you’re not going to see a lot of false-positive results.”

The guidelines back in May didn’t make recommendations on rapid tests, she said, because there weren’t enough data in the literature.

Dr. Caliendo noted that most of the available data were for symptomatic patients, but there are some data that show the amount of virus in the respiratory tract is similar for people with and without symptoms. The panel, therefore, expects that the performance of the various assays would be similar whether or not a person had symptoms.

Testing the immunocompromised

Dr. Hanson said the original recommendation in May was to do molecular testing for asymptomatic people who were awaiting a transplant or were waiting to start immunosuppressive therapy for cancer or an autoimmune disease. Now the current guidelines “make no recommendation for or against screening” in those cases.

Dr. Hanson added that the panel feels that patients awaiting bone marrow and solid organ transplants should have the testing because of the high risks that will result if patients have contracted the virus.

But for those with cancer or an autoimmune disease, the panel decided to leave it up to each physician to assess individual risk and determine whether the patient should be tested.

Home testing

The IDSA guidelines didn’t weigh in on home testing because the products are so new and studies so far have included fewer than 200 patients. But Dr. Caliendo said they clearly perform better earlier in the disease phase – the first 5-7 days – when the amount of the virus is higher.

Dr. Hanson and Dr. Caliendo also fielded a question about what the new virus variant, first discovered in the United Kingdom and now spreading to other countries (including the United States) means for diagnostic testing.

“So far we think with the majority of tests that are [emergency use] authorized, it doesn’t look like this new variant should really affect test performance,” Dr. Hanson said.

The variant has differences in the spike gene, and many of the current tests detect and identify SARS-CoV-2 without the spike gene so they wouldn’t be affected, she added.

Dr. Caliendo agreed: “I think the vast majority of our tests should be in good shape.”

Dr. Hanson and Dr. Caliendo disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Saliva spit tests stack up well against the gold standard for molecular COVID-19 tests – the back-of-the-nose deep swab – without the discomfort and induced coughing or sneezing of the test taker, updated guidelines indicate.

In a press briefing on Jan. 6, the Infectious Diseases Society of America explained the findings of an expert panel that reviewed the literature since the IDSA released its first guidelines in May.

The panel found that saliva tests were especially effective if the test included instructions to cough or clear the throat before spitting into the tube, said panel chair Kimberly E. Hanson, MD, MHS, of University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City.

Throat swab alone less effective

Using a throat swab alone was less effective and missed more cases than the other methods, she said.

The IDSA has updated its recommendation: A saliva test or swabs from either the middle or front of the nose front are preferred to a throat swab alone.

A combination of saliva and swabs from the front and middle of the nose and throat together “looked pretty much equivalent” to the gold-standard deep swab, the panel found.

She acknowledged, however, that multiple swabs exacerbate already challenging supply issues.

Saliva samples do come with challenges, Dr. Hanson noted. A laboratory must validate that its systems can handle the stickier material. And asking a patient to cough necessitates more personal protective equipment for the health care professional.

Each center will have to tailor the specimen type it chooses, based on what resources it has available and the setting – whether in a hospital or a drive-through operation, for instance, she said.

Rapid testing vs. standard

Panel member Angela M. Caliendo, MD, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., said the panel preferred rapid polymerase chain reaction tests and standard, laboratory-based PCR tests over a rapid isothermal test.

The panel defined rapid tests as those for which results are available within an hour after a test provider has the specimen in hand. They excluded home tests for this category.

The only rapid isothermal test that had enough data on which to issue a recommendation was the ID NOW test (Abbott Labs), she noted.

Rapid PCR tests performed just as well as the standard laboratory-based tests, she said, with a high sensitivity of “97% on average and a very high specificity.”

But the rapid isothermal test had an average sensitivity of only about 80%, compared with the lab-based PCR test, Dr. Caliendo said, yielding a substantial number of false-negative results.

Testing centers will have to weigh the considerable advantages of having results in 15 minutes with a rapid isothermal test and being able to educate positive patients about immediate isolation against the potential for false negatives, which could send positive patients home thinking they don’t have the virus – and thus potentially spreading the disease.

And if a clinician gets a negative result with the rapid isothermal test, but has a strong suspicion the person has COVID or lives in an area with high prevalence, a backup test with a rapid PCR or laboratory-based test should be administered.

“You will miss a certain percentage of people using this rapid isothermal test,” she said.

However, Dr. Caliendo said, if the only available option is the isothermal test, “you should definitely use it because it’s certainly better than not testing at all.”

On a positive note, she said, all the varieties of tests have high specificity, so “you’re not going to see a lot of false-positive results.”

The guidelines back in May didn’t make recommendations on rapid tests, she said, because there weren’t enough data in the literature.

Dr. Caliendo noted that most of the available data were for symptomatic patients, but there are some data that show the amount of virus in the respiratory tract is similar for people with and without symptoms. The panel, therefore, expects that the performance of the various assays would be similar whether or not a person had symptoms.

Testing the immunocompromised

Dr. Hanson said the original recommendation in May was to do molecular testing for asymptomatic people who were awaiting a transplant or were waiting to start immunosuppressive therapy for cancer or an autoimmune disease. Now the current guidelines “make no recommendation for or against screening” in those cases.

Dr. Hanson added that the panel feels that patients awaiting bone marrow and solid organ transplants should have the testing because of the high risks that will result if patients have contracted the virus.

But for those with cancer or an autoimmune disease, the panel decided to leave it up to each physician to assess individual risk and determine whether the patient should be tested.

Home testing

The IDSA guidelines didn’t weigh in on home testing because the products are so new and studies so far have included fewer than 200 patients. But Dr. Caliendo said they clearly perform better earlier in the disease phase – the first 5-7 days – when the amount of the virus is higher.

Dr. Hanson and Dr. Caliendo also fielded a question about what the new virus variant, first discovered in the United Kingdom and now spreading to other countries (including the United States) means for diagnostic testing.

“So far we think with the majority of tests that are [emergency use] authorized, it doesn’t look like this new variant should really affect test performance,” Dr. Hanson said.

The variant has differences in the spike gene, and many of the current tests detect and identify SARS-CoV-2 without the spike gene so they wouldn’t be affected, she added.

Dr. Caliendo agreed: “I think the vast majority of our tests should be in good shape.”

Dr. Hanson and Dr. Caliendo disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Saliva spit tests stack up well against the gold standard for molecular COVID-19 tests – the back-of-the-nose deep swab – without the discomfort and induced coughing or sneezing of the test taker, updated guidelines indicate.

In a press briefing on Jan. 6, the Infectious Diseases Society of America explained the findings of an expert panel that reviewed the literature since the IDSA released its first guidelines in May.

The panel found that saliva tests were especially effective if the test included instructions to cough or clear the throat before spitting into the tube, said panel chair Kimberly E. Hanson, MD, MHS, of University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City.

Throat swab alone less effective

Using a throat swab alone was less effective and missed more cases than the other methods, she said.

The IDSA has updated its recommendation: A saliva test or swabs from either the middle or front of the nose front are preferred to a throat swab alone.

A combination of saliva and swabs from the front and middle of the nose and throat together “looked pretty much equivalent” to the gold-standard deep swab, the panel found.

She acknowledged, however, that multiple swabs exacerbate already challenging supply issues.

Saliva samples do come with challenges, Dr. Hanson noted. A laboratory must validate that its systems can handle the stickier material. And asking a patient to cough necessitates more personal protective equipment for the health care professional.

Each center will have to tailor the specimen type it chooses, based on what resources it has available and the setting – whether in a hospital or a drive-through operation, for instance, she said.

Rapid testing vs. standard

Panel member Angela M. Caliendo, MD, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., said the panel preferred rapid polymerase chain reaction tests and standard, laboratory-based PCR tests over a rapid isothermal test.

The panel defined rapid tests as those for which results are available within an hour after a test provider has the specimen in hand. They excluded home tests for this category.

The only rapid isothermal test that had enough data on which to issue a recommendation was the ID NOW test (Abbott Labs), she noted.

Rapid PCR tests performed just as well as the standard laboratory-based tests, she said, with a high sensitivity of “97% on average and a very high specificity.”

But the rapid isothermal test had an average sensitivity of only about 80%, compared with the lab-based PCR test, Dr. Caliendo said, yielding a substantial number of false-negative results.

Testing centers will have to weigh the considerable advantages of having results in 15 minutes with a rapid isothermal test and being able to educate positive patients about immediate isolation against the potential for false negatives, which could send positive patients home thinking they don’t have the virus – and thus potentially spreading the disease.

And if a clinician gets a negative result with the rapid isothermal test, but has a strong suspicion the person has COVID or lives in an area with high prevalence, a backup test with a rapid PCR or laboratory-based test should be administered.

“You will miss a certain percentage of people using this rapid isothermal test,” she said.

However, Dr. Caliendo said, if the only available option is the isothermal test, “you should definitely use it because it’s certainly better than not testing at all.”

On a positive note, she said, all the varieties of tests have high specificity, so “you’re not going to see a lot of false-positive results.”

The guidelines back in May didn’t make recommendations on rapid tests, she said, because there weren’t enough data in the literature.

Dr. Caliendo noted that most of the available data were for symptomatic patients, but there are some data that show the amount of virus in the respiratory tract is similar for people with and without symptoms. The panel, therefore, expects that the performance of the various assays would be similar whether or not a person had symptoms.

Testing the immunocompromised

Dr. Hanson said the original recommendation in May was to do molecular testing for asymptomatic people who were awaiting a transplant or were waiting to start immunosuppressive therapy for cancer or an autoimmune disease. Now the current guidelines “make no recommendation for or against screening” in those cases.

Dr. Hanson added that the panel feels that patients awaiting bone marrow and solid organ transplants should have the testing because of the high risks that will result if patients have contracted the virus.

But for those with cancer or an autoimmune disease, the panel decided to leave it up to each physician to assess individual risk and determine whether the patient should be tested.

Home testing

The IDSA guidelines didn’t weigh in on home testing because the products are so new and studies so far have included fewer than 200 patients. But Dr. Caliendo said they clearly perform better earlier in the disease phase – the first 5-7 days – when the amount of the virus is higher.

Dr. Hanson and Dr. Caliendo also fielded a question about what the new virus variant, first discovered in the United Kingdom and now spreading to other countries (including the United States) means for diagnostic testing.

“So far we think with the majority of tests that are [emergency use] authorized, it doesn’t look like this new variant should really affect test performance,” Dr. Hanson said.

The variant has differences in the spike gene, and many of the current tests detect and identify SARS-CoV-2 without the spike gene so they wouldn’t be affected, she added.

Dr. Caliendo agreed: “I think the vast majority of our tests should be in good shape.”

Dr. Hanson and Dr. Caliendo disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Guidance issued on COVID vaccine use in patients with dermal fillers

outlining the potential risk and clinical relevance.

The association is not surprising, since other vaccines, including the influenza vaccine, have also been associated with inflammatory reactions in patients with dermal fillers. A warning about inflammatory events from these and other immunologic triggers should be part of routine informed consent, according to Sue Ellen Cox, MD, a coauthor of the guidance and the ASDS president-elect.

“Patients who have had dermal filler should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine, and those who have received the vaccine should not be discouraged from receiving dermal filler,” Dr. Cox, who practices in Chapel Hill, N.C., said in an interview.

The only available data to assess the risk came from the trial of the Moderna vaccine. Of a total of 15,184 participants who received at least one dose of mRNA-1273, three developed facial or lip swelling that was presumably related to dermal filler. In the placebo group, there were no comparable inflammatory events.

“This is a very small number, but there is no reliable information about the number of patients in either group who had dermal filler, so we do not know the denominator,” Dr. Cox said.

In all three cases, the swelling at the site of dermal filler was observed within 2 days of the vaccination. None were considered a serious adverse event and all resolved. The filler had been administered 2 weeks prior to vaccination in one case, 6 months prior in a second, and time of administration was unknown in the third.

The resolution of the inflammatory reactions associated with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is similar to those related to dermal fillers following other immunologic triggers, which not only include other vaccines, but viral or bacterial illnesses and dental procedures. Typically, they are readily controlled with oral corticosteroids, but also typically resolve even in the absence of treatment, according to Dr. Cox.

“The good news is that these will go away,” Dr. Cox said.

The ASDS guidance is meant to alert clinicians and patients to the potential association between inflammatory events and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with dermal filler, but Dr. Cox said that it will ultimately have very little effect on her own practice. She already employs an informed consent that includes language warning about the potential risk of local reactions to immunological triggers that include vaccines. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination can now be added to examples of potential triggers, but it does not change the importance of informing patients of such triggers, Dr. Cox explained.

Asked if patients should be informed specifically about the association between dermal filler inflammatory reactions and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the current ASDS president and first author of the guidance, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, suggested that they should. Although he emphasized that the side effect is clearly rare, he believes it deserves attention.

“We wanted dermatologists and other physicians to be aware of the potential. We focused on the available data but specifically decided not to provide any treatment recommendations at this time,” he said in an interview.

As new data become available, the Soft-Tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

“Our guidance was based only on the trial data, but there will soon be tens of millions of patients exposed to several different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. We may learn things we do not know now, and we plan to communicate to our membership and others any new information as events unfold,” said Dr. Avram, who is director of dermatologic surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston,

Based on her own expertise in the field, Dr. Cox suggested that administration of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and administration of dermal filler should be separated by at least 2 weeks regardless of which comes first. Her recommendation is not based on controlled data, but she considers this a prudent interval even if it has not been tested in a controlled study.

The full ASDS guidance is scheduled to appear in an upcoming issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

As new data become available, the Soft-tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other types of vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

This article was updated 1/7/21.

outlining the potential risk and clinical relevance.

The association is not surprising, since other vaccines, including the influenza vaccine, have also been associated with inflammatory reactions in patients with dermal fillers. A warning about inflammatory events from these and other immunologic triggers should be part of routine informed consent, according to Sue Ellen Cox, MD, a coauthor of the guidance and the ASDS president-elect.

“Patients who have had dermal filler should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine, and those who have received the vaccine should not be discouraged from receiving dermal filler,” Dr. Cox, who practices in Chapel Hill, N.C., said in an interview.

The only available data to assess the risk came from the trial of the Moderna vaccine. Of a total of 15,184 participants who received at least one dose of mRNA-1273, three developed facial or lip swelling that was presumably related to dermal filler. In the placebo group, there were no comparable inflammatory events.