User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

FDA approves OTC antihistamine nasal spray

, making it the first nasal antihistamine available over the counter in the United States.

The 0.15% strength of azelastine hydrochloride nasal spray is now approved for nonprescription treatment of seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis in adults and children 6 years of age or older, the agency said. The 0.1% strength remains a prescription product that is indicated in younger children.

The “approval provides individuals an option for a safe and effective nasal antihistamine without requiring the assistance of a health care provider,” Theresa M. Michele, MD, director of the office of nonprescription drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement.

The FDA granted the nonprescription approval to Bayer Healthcare LLC, which said in a press release that the nasal spray would be available in national mass retail locations starting in the first quarter of 2022.

Oral antihistamines such as cetirizine (Zyrtec), loratadine (Claritin), and fexofenadine (Allegra) have been on store shelves for years. Azelastine 0.15% will be the first and only over-the-counter antihistamine for indoor and outdoor allergy relief in a nasal formulation, Bayer said.

An over-the-counter nasal antihistamine could be a better option for some allergy sufferers when compared with what is already over the counter, said Tracy Prematta, MD, a private practice allergist in Havertown, Pa.

“In general, I like the nasal antihistamines,” Dr. Prematta said in an interview. “They work quickly, whereas the nasal steroids don’t, and I think a lot of people who go to the drugstore looking for allergy relief are actually looking for something quick-acting.”

However, the cost of the over-the-counter azelastine may play a big role in whether patients go with the prescription or nonprescription option, according to Dr. Prematta.

Bayer has not yet set the price for nonprescription azelastine, a company spokesperson told this news organization.

The change in azelastine approval status happened through a regulatory process called an Rx-to-OTC switch. According to the FDA, products switched to nonprescription status need to have data demonstrating that they are safe and effective as self-medication when used as directed.

The product manufacturer has to show that consumers know how to use the drug safely and effectively without a health care professional supervising them, the FDA said.

The FDA considers the change in status for azelastine a partial Rx-to-OTC switch, since the 0.15% strength is now over the counter and the 0.1% strength remains a prescription product.

The 0.1% strength is indicated for perennial allergies in children 6 months to 6 years old, and seasonal allergies for children 2-6 years old, according to the FDA.

Drowsiness is a side effect of azelastine, the FDA said. According to prescribing information, consumers using the nasal spray need to be careful when driving or operating machinery, and should avoid alcohol.

Using the product with alcohol, sedatives, or tranquilizers may increase drowsiness, the agency added.

Sedation is also common with the oral antihistamines people take to treat their allergies, said Dr. Prematta, who added that patients may also complain of dry mouth, nose, or throat.

Although some allergy sufferers dislike the taste of antihistamine nasal spray, they can try to overcome that issue by tilting the head forward, pointing the tip of the nozzle toward the outside of the nose, and sniffing gently, Dr. Prematta said.

“That really minimizes what gets in the back of your throat, so taste becomes less of a problem,” she explained.

Dr. Prematta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, making it the first nasal antihistamine available over the counter in the United States.

The 0.15% strength of azelastine hydrochloride nasal spray is now approved for nonprescription treatment of seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis in adults and children 6 years of age or older, the agency said. The 0.1% strength remains a prescription product that is indicated in younger children.

The “approval provides individuals an option for a safe and effective nasal antihistamine without requiring the assistance of a health care provider,” Theresa M. Michele, MD, director of the office of nonprescription drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement.

The FDA granted the nonprescription approval to Bayer Healthcare LLC, which said in a press release that the nasal spray would be available in national mass retail locations starting in the first quarter of 2022.

Oral antihistamines such as cetirizine (Zyrtec), loratadine (Claritin), and fexofenadine (Allegra) have been on store shelves for years. Azelastine 0.15% will be the first and only over-the-counter antihistamine for indoor and outdoor allergy relief in a nasal formulation, Bayer said.

An over-the-counter nasal antihistamine could be a better option for some allergy sufferers when compared with what is already over the counter, said Tracy Prematta, MD, a private practice allergist in Havertown, Pa.

“In general, I like the nasal antihistamines,” Dr. Prematta said in an interview. “They work quickly, whereas the nasal steroids don’t, and I think a lot of people who go to the drugstore looking for allergy relief are actually looking for something quick-acting.”

However, the cost of the over-the-counter azelastine may play a big role in whether patients go with the prescription or nonprescription option, according to Dr. Prematta.

Bayer has not yet set the price for nonprescription azelastine, a company spokesperson told this news organization.

The change in azelastine approval status happened through a regulatory process called an Rx-to-OTC switch. According to the FDA, products switched to nonprescription status need to have data demonstrating that they are safe and effective as self-medication when used as directed.

The product manufacturer has to show that consumers know how to use the drug safely and effectively without a health care professional supervising them, the FDA said.

The FDA considers the change in status for azelastine a partial Rx-to-OTC switch, since the 0.15% strength is now over the counter and the 0.1% strength remains a prescription product.

The 0.1% strength is indicated for perennial allergies in children 6 months to 6 years old, and seasonal allergies for children 2-6 years old, according to the FDA.

Drowsiness is a side effect of azelastine, the FDA said. According to prescribing information, consumers using the nasal spray need to be careful when driving or operating machinery, and should avoid alcohol.

Using the product with alcohol, sedatives, or tranquilizers may increase drowsiness, the agency added.

Sedation is also common with the oral antihistamines people take to treat their allergies, said Dr. Prematta, who added that patients may also complain of dry mouth, nose, or throat.

Although some allergy sufferers dislike the taste of antihistamine nasal spray, they can try to overcome that issue by tilting the head forward, pointing the tip of the nozzle toward the outside of the nose, and sniffing gently, Dr. Prematta said.

“That really minimizes what gets in the back of your throat, so taste becomes less of a problem,” she explained.

Dr. Prematta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, making it the first nasal antihistamine available over the counter in the United States.

The 0.15% strength of azelastine hydrochloride nasal spray is now approved for nonprescription treatment of seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis in adults and children 6 years of age or older, the agency said. The 0.1% strength remains a prescription product that is indicated in younger children.

The “approval provides individuals an option for a safe and effective nasal antihistamine without requiring the assistance of a health care provider,” Theresa M. Michele, MD, director of the office of nonprescription drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement.

The FDA granted the nonprescription approval to Bayer Healthcare LLC, which said in a press release that the nasal spray would be available in national mass retail locations starting in the first quarter of 2022.

Oral antihistamines such as cetirizine (Zyrtec), loratadine (Claritin), and fexofenadine (Allegra) have been on store shelves for years. Azelastine 0.15% will be the first and only over-the-counter antihistamine for indoor and outdoor allergy relief in a nasal formulation, Bayer said.

An over-the-counter nasal antihistamine could be a better option for some allergy sufferers when compared with what is already over the counter, said Tracy Prematta, MD, a private practice allergist in Havertown, Pa.

“In general, I like the nasal antihistamines,” Dr. Prematta said in an interview. “They work quickly, whereas the nasal steroids don’t, and I think a lot of people who go to the drugstore looking for allergy relief are actually looking for something quick-acting.”

However, the cost of the over-the-counter azelastine may play a big role in whether patients go with the prescription or nonprescription option, according to Dr. Prematta.

Bayer has not yet set the price for nonprescription azelastine, a company spokesperson told this news organization.

The change in azelastine approval status happened through a regulatory process called an Rx-to-OTC switch. According to the FDA, products switched to nonprescription status need to have data demonstrating that they are safe and effective as self-medication when used as directed.

The product manufacturer has to show that consumers know how to use the drug safely and effectively without a health care professional supervising them, the FDA said.

The FDA considers the change in status for azelastine a partial Rx-to-OTC switch, since the 0.15% strength is now over the counter and the 0.1% strength remains a prescription product.

The 0.1% strength is indicated for perennial allergies in children 6 months to 6 years old, and seasonal allergies for children 2-6 years old, according to the FDA.

Drowsiness is a side effect of azelastine, the FDA said. According to prescribing information, consumers using the nasal spray need to be careful when driving or operating machinery, and should avoid alcohol.

Using the product with alcohol, sedatives, or tranquilizers may increase drowsiness, the agency added.

Sedation is also common with the oral antihistamines people take to treat their allergies, said Dr. Prematta, who added that patients may also complain of dry mouth, nose, or throat.

Although some allergy sufferers dislike the taste of antihistamine nasal spray, they can try to overcome that issue by tilting the head forward, pointing the tip of the nozzle toward the outside of the nose, and sniffing gently, Dr. Prematta said.

“That really minimizes what gets in the back of your throat, so taste becomes less of a problem,” she explained.

Dr. Prematta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

High rates of work-related trauma, PTSD in intern physicians

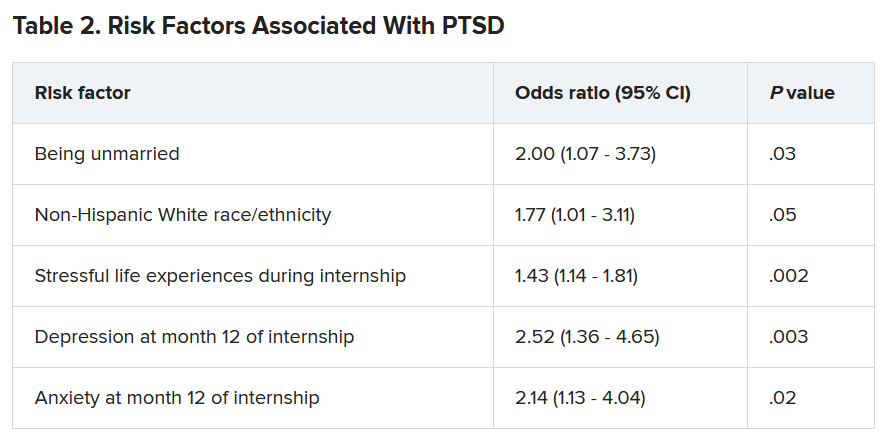

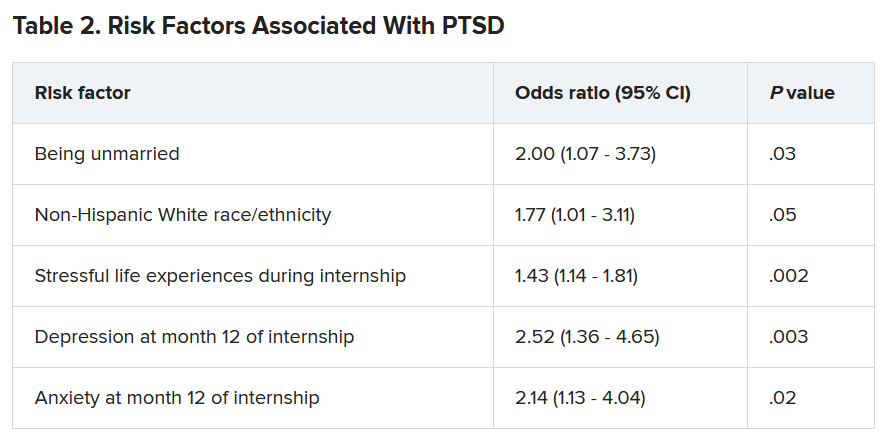

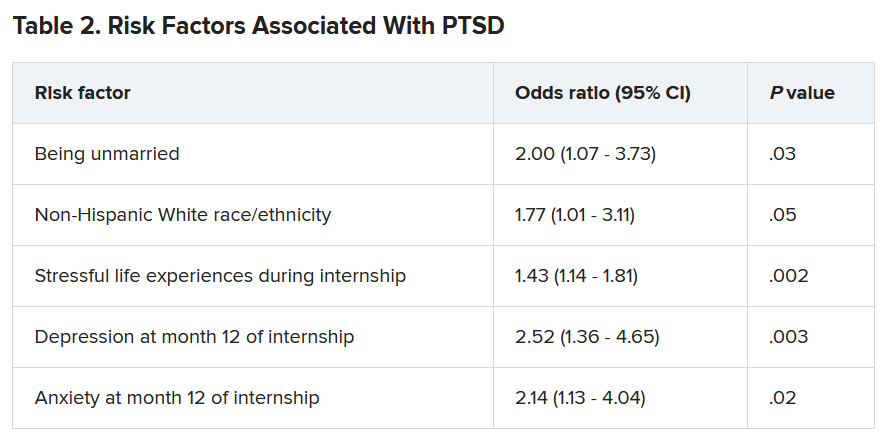

Work-related posttraumatic stress disorder is three times higher in interns than the general population, new research shows.

Investigators assessed PTSD in more than 1,100 physicians at the end of their internship year and found that a little over half reported work-related trauma exposure, and of these, 20% screened positive for PTSD.

Overall, 10% of participants screened positive for PTSD by the end of the internship year, compared with a 12-month PTSD prevalence of 3.6% in the general population.

“Work-related trauma exposure and PTSD are common and underdiscussed phenomena among intern physicians,” lead author Mary Vance, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., said in an interview.

“I urge medical educators and policy makers to include this topic in their discussions about physician well-being and to implement effective interventions to mitigate the impact of work-related trauma and PTSD among physician trainees,” she said.

The study was published online June 8 in JAMA Network Open.

Burnout, depression, suicide

“Burnout, depression, and suicide are increasingly recognized as occupational mental health hazards among health care professionals, including physicians,” Dr. Vance said.

“However, in my professional experience as a physician and educator, despite observing anecdotal evidence among my peers and trainees that this is also an issue,” she added.

This gap prompted her “to investigate rates of work-related trauma exposure and PTSD among physicians.”

The researchers sent emails to 4,350 individuals during academic year 2018-2019, 2 months prior to starting internships. Of these, 2,129 agreed to participate and 1,134 (58.6% female, 61.6% non-Hispanic White; mean age, 27.52) completed the study.

Prior to beginning internship, participants completed a baseline survey that assessed demographic characteristics as well as medical education and psychological and psychosocial factors.

Participants completed follow-up surveys sent by email at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of the internship year. The surveys assessed stressful life events, concern over perceived medical errors in the past 3 months, and number of hours worked over the past week.

At month 12, current PTSD and symptoms of depression and anxiety were also assessed using the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5, the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale, respectively.

Participants were asked to self-report whether they ever had an episode of depression and to complete the Risky Families Questionnaire to assess if they had experienced childhood abuse, neglect, and family conflict. Additionally, they completed an 11-item scale developed specifically for the study regarding recent stressful events.

‘Crucible’ year

A total of 56.4% of respondents reported work-related trauma exposure, and among these, 19.0% screened positive for PTSD. One-tenth (10.8%) of the entire sample screened positive for PTSD by the end of internship year, which is three times higher than the 12-month prevalence of PTSD in the general population (3.6%), the authors noted.

Trauma exposure differed by specialty, ranging from 43.1% in anesthesiology to 72.4% in emergency medicine. Of the respondents in internal medicine, surgery, and medicine/pediatrics, 56.6%, 63.3%, and 71%, respectively, reported work-related trauma exposure.

Work-related PTSD also differed by specialty, ranging from 7.5% in ob.gyn. to 30.0% in pediatrics. Of respondents in internal medicine and family practice, 23.9% and 25.9%, respectively, reported work-related PTSD.

Dr. Vance called the intern year “a crucible, during which newly minted doctors receive intensive on-the-job training at the front lines of patient care [and] work long hours in rapidly shifting environments, often caring for critically ill patients.”

Work-related trauma exposure “is more likely to occur during this high-stress internship year than during the same year in the general population,” she said.

She noted that the “issue of workplace trauma and PTSD among health care workers became even more salient during the height of COVID,” adding that she expects it “to remain a pressure issue for healthcare workers in the post-COVID era.”

Call to action

Commenting on the study David A. Marcus, MD, chair, GME Physician Well-Being Committee, Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, N.Y., noted the study’s “relatively low response rate” is a “significant limitation” of the study.

An additional limitation is the lack of a baseline PTSD assessment, said Dr. Marcus, an assistant professor at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., who was not involved in the research.

Nevertheless, the “overall prevalence [of work-related PTSD] should serve as a call to action for physician leaders and for leaders in academic medicine,” he said.

Additionally, the study “reminds us that trauma-informed care should be an essential part of mental health support services provided to trainees and to physicians in general,” Dr. Marcus stated.

Also commenting on the study, Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, professor of medicine and medical education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., agreed.

“Organizational strategies should include system-level interventions to reduce the risk of frightening, horrible, or traumatic events from occurring in the workplace in the first place, as well as faculty development efforts to upskill teaching faculty in their ability to support trainees when such events do occur,” she said.

These approaches “should coincide with organizational efforts to support individual trainees by providing adequate time off after traumatic events, ensuring trainees can access affordable mental healthcare, and reducing other barriers to appropriate help-seeking, such as stigma, and efforts to build a culture of well-being,” suggested Dr. Dyrbye, who is codirector of the Mayo Clinic Program on Physician Wellbeing and was not involved in the study.

The study was supported by grants from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Vance and coauthors, Dr. Marcus, and Dr. Dyrbye reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Work-related posttraumatic stress disorder is three times higher in interns than the general population, new research shows.

Investigators assessed PTSD in more than 1,100 physicians at the end of their internship year and found that a little over half reported work-related trauma exposure, and of these, 20% screened positive for PTSD.

Overall, 10% of participants screened positive for PTSD by the end of the internship year, compared with a 12-month PTSD prevalence of 3.6% in the general population.

“Work-related trauma exposure and PTSD are common and underdiscussed phenomena among intern physicians,” lead author Mary Vance, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., said in an interview.

“I urge medical educators and policy makers to include this topic in their discussions about physician well-being and to implement effective interventions to mitigate the impact of work-related trauma and PTSD among physician trainees,” she said.

The study was published online June 8 in JAMA Network Open.

Burnout, depression, suicide

“Burnout, depression, and suicide are increasingly recognized as occupational mental health hazards among health care professionals, including physicians,” Dr. Vance said.

“However, in my professional experience as a physician and educator, despite observing anecdotal evidence among my peers and trainees that this is also an issue,” she added.

This gap prompted her “to investigate rates of work-related trauma exposure and PTSD among physicians.”

The researchers sent emails to 4,350 individuals during academic year 2018-2019, 2 months prior to starting internships. Of these, 2,129 agreed to participate and 1,134 (58.6% female, 61.6% non-Hispanic White; mean age, 27.52) completed the study.

Prior to beginning internship, participants completed a baseline survey that assessed demographic characteristics as well as medical education and psychological and psychosocial factors.

Participants completed follow-up surveys sent by email at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of the internship year. The surveys assessed stressful life events, concern over perceived medical errors in the past 3 months, and number of hours worked over the past week.

At month 12, current PTSD and symptoms of depression and anxiety were also assessed using the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5, the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale, respectively.

Participants were asked to self-report whether they ever had an episode of depression and to complete the Risky Families Questionnaire to assess if they had experienced childhood abuse, neglect, and family conflict. Additionally, they completed an 11-item scale developed specifically for the study regarding recent stressful events.

‘Crucible’ year

A total of 56.4% of respondents reported work-related trauma exposure, and among these, 19.0% screened positive for PTSD. One-tenth (10.8%) of the entire sample screened positive for PTSD by the end of internship year, which is three times higher than the 12-month prevalence of PTSD in the general population (3.6%), the authors noted.

Trauma exposure differed by specialty, ranging from 43.1% in anesthesiology to 72.4% in emergency medicine. Of the respondents in internal medicine, surgery, and medicine/pediatrics, 56.6%, 63.3%, and 71%, respectively, reported work-related trauma exposure.

Work-related PTSD also differed by specialty, ranging from 7.5% in ob.gyn. to 30.0% in pediatrics. Of respondents in internal medicine and family practice, 23.9% and 25.9%, respectively, reported work-related PTSD.

Dr. Vance called the intern year “a crucible, during which newly minted doctors receive intensive on-the-job training at the front lines of patient care [and] work long hours in rapidly shifting environments, often caring for critically ill patients.”

Work-related trauma exposure “is more likely to occur during this high-stress internship year than during the same year in the general population,” she said.

She noted that the “issue of workplace trauma and PTSD among health care workers became even more salient during the height of COVID,” adding that she expects it “to remain a pressure issue for healthcare workers in the post-COVID era.”

Call to action

Commenting on the study David A. Marcus, MD, chair, GME Physician Well-Being Committee, Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, N.Y., noted the study’s “relatively low response rate” is a “significant limitation” of the study.

An additional limitation is the lack of a baseline PTSD assessment, said Dr. Marcus, an assistant professor at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., who was not involved in the research.

Nevertheless, the “overall prevalence [of work-related PTSD] should serve as a call to action for physician leaders and for leaders in academic medicine,” he said.

Additionally, the study “reminds us that trauma-informed care should be an essential part of mental health support services provided to trainees and to physicians in general,” Dr. Marcus stated.

Also commenting on the study, Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, professor of medicine and medical education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., agreed.

“Organizational strategies should include system-level interventions to reduce the risk of frightening, horrible, or traumatic events from occurring in the workplace in the first place, as well as faculty development efforts to upskill teaching faculty in their ability to support trainees when such events do occur,” she said.

These approaches “should coincide with organizational efforts to support individual trainees by providing adequate time off after traumatic events, ensuring trainees can access affordable mental healthcare, and reducing other barriers to appropriate help-seeking, such as stigma, and efforts to build a culture of well-being,” suggested Dr. Dyrbye, who is codirector of the Mayo Clinic Program on Physician Wellbeing and was not involved in the study.

The study was supported by grants from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Vance and coauthors, Dr. Marcus, and Dr. Dyrbye reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Work-related posttraumatic stress disorder is three times higher in interns than the general population, new research shows.

Investigators assessed PTSD in more than 1,100 physicians at the end of their internship year and found that a little over half reported work-related trauma exposure, and of these, 20% screened positive for PTSD.

Overall, 10% of participants screened positive for PTSD by the end of the internship year, compared with a 12-month PTSD prevalence of 3.6% in the general population.

“Work-related trauma exposure and PTSD are common and underdiscussed phenomena among intern physicians,” lead author Mary Vance, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., said in an interview.

“I urge medical educators and policy makers to include this topic in their discussions about physician well-being and to implement effective interventions to mitigate the impact of work-related trauma and PTSD among physician trainees,” she said.

The study was published online June 8 in JAMA Network Open.

Burnout, depression, suicide

“Burnout, depression, and suicide are increasingly recognized as occupational mental health hazards among health care professionals, including physicians,” Dr. Vance said.

“However, in my professional experience as a physician and educator, despite observing anecdotal evidence among my peers and trainees that this is also an issue,” she added.

This gap prompted her “to investigate rates of work-related trauma exposure and PTSD among physicians.”

The researchers sent emails to 4,350 individuals during academic year 2018-2019, 2 months prior to starting internships. Of these, 2,129 agreed to participate and 1,134 (58.6% female, 61.6% non-Hispanic White; mean age, 27.52) completed the study.

Prior to beginning internship, participants completed a baseline survey that assessed demographic characteristics as well as medical education and psychological and psychosocial factors.

Participants completed follow-up surveys sent by email at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of the internship year. The surveys assessed stressful life events, concern over perceived medical errors in the past 3 months, and number of hours worked over the past week.

At month 12, current PTSD and symptoms of depression and anxiety were also assessed using the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5, the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale, respectively.

Participants were asked to self-report whether they ever had an episode of depression and to complete the Risky Families Questionnaire to assess if they had experienced childhood abuse, neglect, and family conflict. Additionally, they completed an 11-item scale developed specifically for the study regarding recent stressful events.

‘Crucible’ year

A total of 56.4% of respondents reported work-related trauma exposure, and among these, 19.0% screened positive for PTSD. One-tenth (10.8%) of the entire sample screened positive for PTSD by the end of internship year, which is three times higher than the 12-month prevalence of PTSD in the general population (3.6%), the authors noted.

Trauma exposure differed by specialty, ranging from 43.1% in anesthesiology to 72.4% in emergency medicine. Of the respondents in internal medicine, surgery, and medicine/pediatrics, 56.6%, 63.3%, and 71%, respectively, reported work-related trauma exposure.

Work-related PTSD also differed by specialty, ranging from 7.5% in ob.gyn. to 30.0% in pediatrics. Of respondents in internal medicine and family practice, 23.9% and 25.9%, respectively, reported work-related PTSD.

Dr. Vance called the intern year “a crucible, during which newly minted doctors receive intensive on-the-job training at the front lines of patient care [and] work long hours in rapidly shifting environments, often caring for critically ill patients.”

Work-related trauma exposure “is more likely to occur during this high-stress internship year than during the same year in the general population,” she said.

She noted that the “issue of workplace trauma and PTSD among health care workers became even more salient during the height of COVID,” adding that she expects it “to remain a pressure issue for healthcare workers in the post-COVID era.”

Call to action

Commenting on the study David A. Marcus, MD, chair, GME Physician Well-Being Committee, Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, N.Y., noted the study’s “relatively low response rate” is a “significant limitation” of the study.

An additional limitation is the lack of a baseline PTSD assessment, said Dr. Marcus, an assistant professor at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., who was not involved in the research.

Nevertheless, the “overall prevalence [of work-related PTSD] should serve as a call to action for physician leaders and for leaders in academic medicine,” he said.

Additionally, the study “reminds us that trauma-informed care should be an essential part of mental health support services provided to trainees and to physicians in general,” Dr. Marcus stated.

Also commenting on the study, Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, professor of medicine and medical education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., agreed.

“Organizational strategies should include system-level interventions to reduce the risk of frightening, horrible, or traumatic events from occurring in the workplace in the first place, as well as faculty development efforts to upskill teaching faculty in their ability to support trainees when such events do occur,” she said.

These approaches “should coincide with organizational efforts to support individual trainees by providing adequate time off after traumatic events, ensuring trainees can access affordable mental healthcare, and reducing other barriers to appropriate help-seeking, such as stigma, and efforts to build a culture of well-being,” suggested Dr. Dyrbye, who is codirector of the Mayo Clinic Program on Physician Wellbeing and was not involved in the study.

The study was supported by grants from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Vance and coauthors, Dr. Marcus, and Dr. Dyrbye reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ten killer steps to writing a great medical thriller

For many physicians and other professionals, aspirations of crafting a work of fiction are not uncommon — and with good reason. We are, after all, a generally well-disciplined bunch capable of completing complex tasks, and there is certainly no shortage of excitement and drama in medicine and surgery — ample fodder for thrilling stories. Nonetheless, writing a novel is a major commitment, and it requires persistence, patience, and dedicated time, especially for one with a busy medical career.

Getting started is not easy. Writing workshops are helpful, and in my case, I tried to mentor with some of the best. Before writing my novel, I attended workshops for aspiring novelists, given by noted physician authors Tess Gerritsen (Body Double, The Surgeon) and the late Michael Palmer (The Society, The Fifth Vial).

Writers are often advised to “write about what you know.” In my case, I combined my knowledge of medicine and my experience with the thoroughbred racing world to craft a thriller that one reviewer described as “Dick Francis meets Robin Cook.” For those who have never read the Dick Francis series, he was a renowned crime writer whose novels centered on horse racing in England. Having been an avid reader of both authors, that comparison was the ultimate compliment.

So against that backdrop, the novel Shedrow, along with some shared wisdom from a few legendary writers.

1. Start with the big “what if.” Any great story starts with that simple “what if” question. What if a series of high-profile executives in the managed care industry are serially murdered (Michael Palmer’s The Society)? What if a multimillion-dollar stallion dies suddenly under very mysterious circumstances on a supposedly secure farm in Kentucky (Dean DeLuke’s Shedrow)?

2. Put a MacGuffin to work in your story. Popularized by Alfred Hitchcock, the MacGuffin is that essential plot element that drives virtually all characters in the story, although it may be rather vague and meaningless to the story itself. In the iconic movie Pulp Fiction, the MacGuffin is the briefcase — everyone wants it, and we never do find out what’s in it.

3. Pacing is critical. Plot out the timeline of emotional highs and lows in a story. It should look like a rolling pattern of highs and lows that crescendo upward to the ultimate crisis. Take advantage of the fact that following any of those emotional peaks, you probably have the reader’s undivided attention. That would be a good time to provide backstory or fill in needed information for the reader – information that may be critical but perhaps not as exciting as what just transpired.

4. Torture your protagonists. Just when the reader thinks that the hero is finally home free, throw in another obstacle. Readers will empathize with the character and be drawn in by the unexpected hurdle.

5. Be original and surprise your readers. Create twists and turns that are totally unexpected, yet believable. This is easier said than done but will go a long way toward making your novel original, gripping, and unpredictable.

6. As a general rule, consider short sentences and short chapters. This is strictly a personal preference, but who can argue with James Patterson’s short chapters or with Robert Parker’s short and engaging sentences? Sentence length can be varied for effect, too, with shorter sentences serving to heighten action or increase tension.

7. Avoid the passive voice. Your readers want action. This is an important rule in almost any type of writing.

8. Keep descriptions brief. Long, drawn-out descriptions of the way characters look, or even setting descriptions, are easily overdone in a thriller. The thriller genre is very different from literary fiction in this regard. Stephen King advises writers to “just say what they see, then get on with the story.”

9. Sustain the reader’s interest throughout. Assess each chapter ending and determine whether the reader has been given enough reason to want to continue reading. Pose a question, end with a minor cliffhanger, or at least ensure that there is enough accumulated tension in the story.

10. Edit aggressively and cut out the fluff. Ernest Hemingway once confided to F. Scott Fitzgerald, “I write one page of masterpiece to 91 pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”

Dr. DeLuke is professor emeritus of oral and facial surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of the novel Shedrow.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For many physicians and other professionals, aspirations of crafting a work of fiction are not uncommon — and with good reason. We are, after all, a generally well-disciplined bunch capable of completing complex tasks, and there is certainly no shortage of excitement and drama in medicine and surgery — ample fodder for thrilling stories. Nonetheless, writing a novel is a major commitment, and it requires persistence, patience, and dedicated time, especially for one with a busy medical career.

Getting started is not easy. Writing workshops are helpful, and in my case, I tried to mentor with some of the best. Before writing my novel, I attended workshops for aspiring novelists, given by noted physician authors Tess Gerritsen (Body Double, The Surgeon) and the late Michael Palmer (The Society, The Fifth Vial).

Writers are often advised to “write about what you know.” In my case, I combined my knowledge of medicine and my experience with the thoroughbred racing world to craft a thriller that one reviewer described as “Dick Francis meets Robin Cook.” For those who have never read the Dick Francis series, he was a renowned crime writer whose novels centered on horse racing in England. Having been an avid reader of both authors, that comparison was the ultimate compliment.

So against that backdrop, the novel Shedrow, along with some shared wisdom from a few legendary writers.

1. Start with the big “what if.” Any great story starts with that simple “what if” question. What if a series of high-profile executives in the managed care industry are serially murdered (Michael Palmer’s The Society)? What if a multimillion-dollar stallion dies suddenly under very mysterious circumstances on a supposedly secure farm in Kentucky (Dean DeLuke’s Shedrow)?

2. Put a MacGuffin to work in your story. Popularized by Alfred Hitchcock, the MacGuffin is that essential plot element that drives virtually all characters in the story, although it may be rather vague and meaningless to the story itself. In the iconic movie Pulp Fiction, the MacGuffin is the briefcase — everyone wants it, and we never do find out what’s in it.

3. Pacing is critical. Plot out the timeline of emotional highs and lows in a story. It should look like a rolling pattern of highs and lows that crescendo upward to the ultimate crisis. Take advantage of the fact that following any of those emotional peaks, you probably have the reader’s undivided attention. That would be a good time to provide backstory or fill in needed information for the reader – information that may be critical but perhaps not as exciting as what just transpired.

4. Torture your protagonists. Just when the reader thinks that the hero is finally home free, throw in another obstacle. Readers will empathize with the character and be drawn in by the unexpected hurdle.

5. Be original and surprise your readers. Create twists and turns that are totally unexpected, yet believable. This is easier said than done but will go a long way toward making your novel original, gripping, and unpredictable.

6. As a general rule, consider short sentences and short chapters. This is strictly a personal preference, but who can argue with James Patterson’s short chapters or with Robert Parker’s short and engaging sentences? Sentence length can be varied for effect, too, with shorter sentences serving to heighten action or increase tension.

7. Avoid the passive voice. Your readers want action. This is an important rule in almost any type of writing.

8. Keep descriptions brief. Long, drawn-out descriptions of the way characters look, or even setting descriptions, are easily overdone in a thriller. The thriller genre is very different from literary fiction in this regard. Stephen King advises writers to “just say what they see, then get on with the story.”

9. Sustain the reader’s interest throughout. Assess each chapter ending and determine whether the reader has been given enough reason to want to continue reading. Pose a question, end with a minor cliffhanger, or at least ensure that there is enough accumulated tension in the story.

10. Edit aggressively and cut out the fluff. Ernest Hemingway once confided to F. Scott Fitzgerald, “I write one page of masterpiece to 91 pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”

Dr. DeLuke is professor emeritus of oral and facial surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of the novel Shedrow.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For many physicians and other professionals, aspirations of crafting a work of fiction are not uncommon — and with good reason. We are, after all, a generally well-disciplined bunch capable of completing complex tasks, and there is certainly no shortage of excitement and drama in medicine and surgery — ample fodder for thrilling stories. Nonetheless, writing a novel is a major commitment, and it requires persistence, patience, and dedicated time, especially for one with a busy medical career.

Getting started is not easy. Writing workshops are helpful, and in my case, I tried to mentor with some of the best. Before writing my novel, I attended workshops for aspiring novelists, given by noted physician authors Tess Gerritsen (Body Double, The Surgeon) and the late Michael Palmer (The Society, The Fifth Vial).

Writers are often advised to “write about what you know.” In my case, I combined my knowledge of medicine and my experience with the thoroughbred racing world to craft a thriller that one reviewer described as “Dick Francis meets Robin Cook.” For those who have never read the Dick Francis series, he was a renowned crime writer whose novels centered on horse racing in England. Having been an avid reader of both authors, that comparison was the ultimate compliment.

So against that backdrop, the novel Shedrow, along with some shared wisdom from a few legendary writers.

1. Start with the big “what if.” Any great story starts with that simple “what if” question. What if a series of high-profile executives in the managed care industry are serially murdered (Michael Palmer’s The Society)? What if a multimillion-dollar stallion dies suddenly under very mysterious circumstances on a supposedly secure farm in Kentucky (Dean DeLuke’s Shedrow)?

2. Put a MacGuffin to work in your story. Popularized by Alfred Hitchcock, the MacGuffin is that essential plot element that drives virtually all characters in the story, although it may be rather vague and meaningless to the story itself. In the iconic movie Pulp Fiction, the MacGuffin is the briefcase — everyone wants it, and we never do find out what’s in it.

3. Pacing is critical. Plot out the timeline of emotional highs and lows in a story. It should look like a rolling pattern of highs and lows that crescendo upward to the ultimate crisis. Take advantage of the fact that following any of those emotional peaks, you probably have the reader’s undivided attention. That would be a good time to provide backstory or fill in needed information for the reader – information that may be critical but perhaps not as exciting as what just transpired.

4. Torture your protagonists. Just when the reader thinks that the hero is finally home free, throw in another obstacle. Readers will empathize with the character and be drawn in by the unexpected hurdle.

5. Be original and surprise your readers. Create twists and turns that are totally unexpected, yet believable. This is easier said than done but will go a long way toward making your novel original, gripping, and unpredictable.

6. As a general rule, consider short sentences and short chapters. This is strictly a personal preference, but who can argue with James Patterson’s short chapters or with Robert Parker’s short and engaging sentences? Sentence length can be varied for effect, too, with shorter sentences serving to heighten action or increase tension.

7. Avoid the passive voice. Your readers want action. This is an important rule in almost any type of writing.

8. Keep descriptions brief. Long, drawn-out descriptions of the way characters look, or even setting descriptions, are easily overdone in a thriller. The thriller genre is very different from literary fiction in this regard. Stephen King advises writers to “just say what they see, then get on with the story.”

9. Sustain the reader’s interest throughout. Assess each chapter ending and determine whether the reader has been given enough reason to want to continue reading. Pose a question, end with a minor cliffhanger, or at least ensure that there is enough accumulated tension in the story.

10. Edit aggressively and cut out the fluff. Ernest Hemingway once confided to F. Scott Fitzgerald, “I write one page of masterpiece to 91 pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”

Dr. DeLuke is professor emeritus of oral and facial surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of the novel Shedrow.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why getting a COVID-19 vaccine to children could take time

Testing COVID-19 vaccines in young children is going to be tricky. Deciding how to approve them and who should get them may be even more difficult.

So far, the vaccines available to Americans ages 12 and up have sailed through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory checks, taking advantage of an accelerated clearance process called an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

EUAs set a lower bar for effectiveness, saying the vaccines may be safe and effective based on just a few months of data.

But with COVID cases plummeting in the United States and children historically seeing far less serious disease than adults, a panel of expert advisors to the FDA was asked to deliberate on Thursday whether the agency could consider vaccines for this age group under the same standard.

Stated another way: Is COVID an emergency for kids?

There’s another wrinkle in the mix, too – heart inflammation, which appears to be a very rare emerging adverse event tied to vaccination. It seems to happen more often in teens and young adults. To date, cases of myocarditis and pericarditis appear to be happening in 16 to 30 people for every 1 million doses given.

But if it is conclusively linked to the shots, some wonder whether it might tip the balance between benefits and risks for kids.

That left some of the experts who sit on the FDA’s advisory committee for vaccines and related biological products urging the FDA to take its time and more thoroughly study the shots before they’re given to millions of children.

Vaccine studies different in children?

Clinical studies of the vaccines in teens and adults have thus far relied on some straightforward math. You take two groups of similar people. You give half the vaccine and half a placebo. Then you wait and see which group has more symptomatic infections. To date, the vaccines have dramatically cut the risk of getting severely ill with COVID for every age group tested.

But COVID infections are falling rapidly in the U.S., and that may make it more difficult for researchers to conduct a similar kind of experiment in children.

The FDA is considering different approaches to figure out whether a vaccine would be effective in kids, including something called an “immunobridging trial.”

In bridging trials, researchers don’t look for infections; rather, they look for proven signs that someone has developed immunity, like antibody levels. Those biomarkers are then compared to the immune responses of younger adults who have demonstrated good protection against infection.

The main advantage of bridging studies is speed. It’s possible to get a snapshot of how the immune system responds to a vaccine within weeks of the final dose.

The drawback is that researchers don’t know exactly what to look for to judge how well the shots are generating protection.

That’s made even more difficult because kids’ immune systems are still developing, so it may be tough to draw direct parallels to adults.

“We don’t know what the serologic correlate of immunity is now. We don’t know how much antibody you have to get in order to be protected. We don’t know what the role of T cells will be,” said H. Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

“I have so much sympathy for the FDA because these are enormous problems, and you have to make a decision,” said Dr. Meissner, who is a member of the FDA’s vaccines and related biological products advisory committee.

Speed vaccines to market, or gather more data?

The plummeting rate of infections in the United States also means that it may be more difficult for the FDA to justify allowing a vaccine on the market for emergency use for children under age 12.

In its recent advisory committee meeting, the agency asked the panel whether it should consider COVID vaccines for children under an EUA or a biologics license application (BLA), aka full approval.

A BLA typically means the agency considers a year or two of data on a new product, rather than just 2 months’ worth. Emergency use also allows products on the market under a looser standard – they “may be” safe and effective, instead of has been proven to be safe and effective.

Several committee members said they didn’t feel the United States was still in an emergency with COVID and couldn’t see the FDA allowing a vaccine to be used in kids that wasn’t given the agency’s highest level of scrutiny, particularly with reports of adverse events like myocarditis coming to light.

“I just want to be sure the price we pay for vaccinating millions of children justifies the side effects, and I don’t think we know that yet,” Dr. Meissner said.

Others acknowledged that there was little risk to kids now with infections on the decline but said that picture could change as variants spread, schools reopen, and colder temperatures force people indoors.

The FDA must decide whether to act based on where we are now or where we could be in a few months.

“I think it’s the million-dollar question right now,” said Hannah Kirking, MD, a medical epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who presented new and unpublished data on COVID’s impact in children to the FDA’s advisory committee.

She said prospective studies tracking the way COVID moves through a household with weekly testing from New York City and Utah had found that children catch and transmit COVID almost as readily as adults. But they don’t usually get as sick as adults do, so their cases are easy to miss.

She also presented the results of blood tests from samples around the country looking for evidence of past infection. In these seroprevalence studies, about 27% of children under age 17 had antibodies to COVID – the most of any age group. So more than 1 in 4 kids already has some natural immunity.

That means the main benefit of vaccinating children might be the protection of others, while they still bear the risks – however tiny.

Some experts felt that wasn’t enough reason to justify mass distribution of the vaccines to kids, and from a regulatory standpoint, it might not be permissible.

“FDA can only approve a medical product in a population if the benefits outweigh the risks in that population,” said Peter Doshi, PhD, assistant professor of pharmaceutical health services research in the University of Maryland’s school of pharmacy, Baltimore.

“If benefits don’t outweigh risks in children, it can’t be indicated for children. Full stop,” said Dr. Doshi, who is also an editor at the BMJ.

He said there’s another way to give children access to vaccines, through an expanded access or compassionate use program. Because most COVID deaths have been in children with underlying health conditions, Dr. Doshi and others said it might make sense to allow expanded access – which would get vaccines to children at high risk for complications – without turning them loose on millions before they are more thoroughly studied.

“It’s not a particularly attractive option for industry, because there’s no money to be made. Your medicine can’t be commercialized under expanded access. The most you can reap is manufacturing cost, which is not a lot,” he said.

Art Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University’s Langone medical center, said the argument for vaccinating children for flu falls along the same lines. The benefit-to-risk ratio is finely balanced in children. The main value of protecting them is to protect others.

“Flu rarely kills young folks. But you’re really trying to protect old folks and that’s the classic example,” he said.

What’s more, he said the idea that children would take on some risk with a vaccine for little personal benefit is oversimplified.

“Yes, you might get vaccinated to prevent harm to others, but those others are providing benefits to you. It’s not a one-way street. I think that’s a little morally distorted,” Mr. Caplan said. “Being able to keep society open benefits kids and adults alike.”

Other committee members felt like it was too early to sound the all-clear on COVID and said the FDA should authorize vaccines for children as quickly as it had for other age groups.

“We are still, I believe, in an emergency situation. I think that when this virus goes into our children, which is what it’s going to do, that will give it an incubator to change,” said Oveta Fuller, PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Fuller said that for the good of the world, Americans needed to vaccinate children to prevent the virus from mutating and creating new and potentially more dangerous variants.

Weighing risk over safety

Beth Thielen, MD, PhD, pediatric infectious disease specialist and virologist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said she had not followed the committee’s discussions, but about once a month she treats kids who are very sick because of the virus – either because of a COVID infection or because of multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), an inflammatory reaction that strikes after infection.

She’s worried about how the virus has already changed. She said the kind of disease she’s seeing in kids now is different than what she saw in the early months of the pandemic.

“In the last couple of months, I’ve actually seen a few cases of severe pulmonary disease, more similar to adult disease in children,” Dr. Thielen said. “I see on the horizon that we could start seeing more significant disease in young people, and then the risks of being unvaccinated go up substantially.”

But she also knows nobody has a crystal ball, and right now, everything seems to be trending in the right direction with COVID. That makes the risk-to-benefit consideration murkier.

“The question in my mind is, what is the risk of side effects from the vaccine?” she said. “I think we really need to know what the safety profile of vaccine looks like in children because we do have a decent understanding now what risk from disease looks like, because it’s small, but we are seeing it.”

Dr. Thielen said she’ll be keeping an eye on the next meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for more answers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Testing COVID-19 vaccines in young children is going to be tricky. Deciding how to approve them and who should get them may be even more difficult.

So far, the vaccines available to Americans ages 12 and up have sailed through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory checks, taking advantage of an accelerated clearance process called an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

EUAs set a lower bar for effectiveness, saying the vaccines may be safe and effective based on just a few months of data.

But with COVID cases plummeting in the United States and children historically seeing far less serious disease than adults, a panel of expert advisors to the FDA was asked to deliberate on Thursday whether the agency could consider vaccines for this age group under the same standard.

Stated another way: Is COVID an emergency for kids?

There’s another wrinkle in the mix, too – heart inflammation, which appears to be a very rare emerging adverse event tied to vaccination. It seems to happen more often in teens and young adults. To date, cases of myocarditis and pericarditis appear to be happening in 16 to 30 people for every 1 million doses given.

But if it is conclusively linked to the shots, some wonder whether it might tip the balance between benefits and risks for kids.

That left some of the experts who sit on the FDA’s advisory committee for vaccines and related biological products urging the FDA to take its time and more thoroughly study the shots before they’re given to millions of children.

Vaccine studies different in children?

Clinical studies of the vaccines in teens and adults have thus far relied on some straightforward math. You take two groups of similar people. You give half the vaccine and half a placebo. Then you wait and see which group has more symptomatic infections. To date, the vaccines have dramatically cut the risk of getting severely ill with COVID for every age group tested.

But COVID infections are falling rapidly in the U.S., and that may make it more difficult for researchers to conduct a similar kind of experiment in children.

The FDA is considering different approaches to figure out whether a vaccine would be effective in kids, including something called an “immunobridging trial.”

In bridging trials, researchers don’t look for infections; rather, they look for proven signs that someone has developed immunity, like antibody levels. Those biomarkers are then compared to the immune responses of younger adults who have demonstrated good protection against infection.

The main advantage of bridging studies is speed. It’s possible to get a snapshot of how the immune system responds to a vaccine within weeks of the final dose.

The drawback is that researchers don’t know exactly what to look for to judge how well the shots are generating protection.

That’s made even more difficult because kids’ immune systems are still developing, so it may be tough to draw direct parallels to adults.

“We don’t know what the serologic correlate of immunity is now. We don’t know how much antibody you have to get in order to be protected. We don’t know what the role of T cells will be,” said H. Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

“I have so much sympathy for the FDA because these are enormous problems, and you have to make a decision,” said Dr. Meissner, who is a member of the FDA’s vaccines and related biological products advisory committee.

Speed vaccines to market, or gather more data?

The plummeting rate of infections in the United States also means that it may be more difficult for the FDA to justify allowing a vaccine on the market for emergency use for children under age 12.

In its recent advisory committee meeting, the agency asked the panel whether it should consider COVID vaccines for children under an EUA or a biologics license application (BLA), aka full approval.

A BLA typically means the agency considers a year or two of data on a new product, rather than just 2 months’ worth. Emergency use also allows products on the market under a looser standard – they “may be” safe and effective, instead of has been proven to be safe and effective.

Several committee members said they didn’t feel the United States was still in an emergency with COVID and couldn’t see the FDA allowing a vaccine to be used in kids that wasn’t given the agency’s highest level of scrutiny, particularly with reports of adverse events like myocarditis coming to light.

“I just want to be sure the price we pay for vaccinating millions of children justifies the side effects, and I don’t think we know that yet,” Dr. Meissner said.

Others acknowledged that there was little risk to kids now with infections on the decline but said that picture could change as variants spread, schools reopen, and colder temperatures force people indoors.

The FDA must decide whether to act based on where we are now or where we could be in a few months.

“I think it’s the million-dollar question right now,” said Hannah Kirking, MD, a medical epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who presented new and unpublished data on COVID’s impact in children to the FDA’s advisory committee.

She said prospective studies tracking the way COVID moves through a household with weekly testing from New York City and Utah had found that children catch and transmit COVID almost as readily as adults. But they don’t usually get as sick as adults do, so their cases are easy to miss.

She also presented the results of blood tests from samples around the country looking for evidence of past infection. In these seroprevalence studies, about 27% of children under age 17 had antibodies to COVID – the most of any age group. So more than 1 in 4 kids already has some natural immunity.

That means the main benefit of vaccinating children might be the protection of others, while they still bear the risks – however tiny.

Some experts felt that wasn’t enough reason to justify mass distribution of the vaccines to kids, and from a regulatory standpoint, it might not be permissible.

“FDA can only approve a medical product in a population if the benefits outweigh the risks in that population,” said Peter Doshi, PhD, assistant professor of pharmaceutical health services research in the University of Maryland’s school of pharmacy, Baltimore.

“If benefits don’t outweigh risks in children, it can’t be indicated for children. Full stop,” said Dr. Doshi, who is also an editor at the BMJ.

He said there’s another way to give children access to vaccines, through an expanded access or compassionate use program. Because most COVID deaths have been in children with underlying health conditions, Dr. Doshi and others said it might make sense to allow expanded access – which would get vaccines to children at high risk for complications – without turning them loose on millions before they are more thoroughly studied.

“It’s not a particularly attractive option for industry, because there’s no money to be made. Your medicine can’t be commercialized under expanded access. The most you can reap is manufacturing cost, which is not a lot,” he said.

Art Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University’s Langone medical center, said the argument for vaccinating children for flu falls along the same lines. The benefit-to-risk ratio is finely balanced in children. The main value of protecting them is to protect others.

“Flu rarely kills young folks. But you’re really trying to protect old folks and that’s the classic example,” he said.

What’s more, he said the idea that children would take on some risk with a vaccine for little personal benefit is oversimplified.

“Yes, you might get vaccinated to prevent harm to others, but those others are providing benefits to you. It’s not a one-way street. I think that’s a little morally distorted,” Mr. Caplan said. “Being able to keep society open benefits kids and adults alike.”

Other committee members felt like it was too early to sound the all-clear on COVID and said the FDA should authorize vaccines for children as quickly as it had for other age groups.

“We are still, I believe, in an emergency situation. I think that when this virus goes into our children, which is what it’s going to do, that will give it an incubator to change,” said Oveta Fuller, PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Fuller said that for the good of the world, Americans needed to vaccinate children to prevent the virus from mutating and creating new and potentially more dangerous variants.

Weighing risk over safety

Beth Thielen, MD, PhD, pediatric infectious disease specialist and virologist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said she had not followed the committee’s discussions, but about once a month she treats kids who are very sick because of the virus – either because of a COVID infection or because of multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), an inflammatory reaction that strikes after infection.

She’s worried about how the virus has already changed. She said the kind of disease she’s seeing in kids now is different than what she saw in the early months of the pandemic.

“In the last couple of months, I’ve actually seen a few cases of severe pulmonary disease, more similar to adult disease in children,” Dr. Thielen said. “I see on the horizon that we could start seeing more significant disease in young people, and then the risks of being unvaccinated go up substantially.”

But she also knows nobody has a crystal ball, and right now, everything seems to be trending in the right direction with COVID. That makes the risk-to-benefit consideration murkier.

“The question in my mind is, what is the risk of side effects from the vaccine?” she said. “I think we really need to know what the safety profile of vaccine looks like in children because we do have a decent understanding now what risk from disease looks like, because it’s small, but we are seeing it.”

Dr. Thielen said she’ll be keeping an eye on the next meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for more answers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Testing COVID-19 vaccines in young children is going to be tricky. Deciding how to approve them and who should get them may be even more difficult.

So far, the vaccines available to Americans ages 12 and up have sailed through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory checks, taking advantage of an accelerated clearance process called an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

EUAs set a lower bar for effectiveness, saying the vaccines may be safe and effective based on just a few months of data.

But with COVID cases plummeting in the United States and children historically seeing far less serious disease than adults, a panel of expert advisors to the FDA was asked to deliberate on Thursday whether the agency could consider vaccines for this age group under the same standard.

Stated another way: Is COVID an emergency for kids?

There’s another wrinkle in the mix, too – heart inflammation, which appears to be a very rare emerging adverse event tied to vaccination. It seems to happen more often in teens and young adults. To date, cases of myocarditis and pericarditis appear to be happening in 16 to 30 people for every 1 million doses given.

But if it is conclusively linked to the shots, some wonder whether it might tip the balance between benefits and risks for kids.

That left some of the experts who sit on the FDA’s advisory committee for vaccines and related biological products urging the FDA to take its time and more thoroughly study the shots before they’re given to millions of children.

Vaccine studies different in children?

Clinical studies of the vaccines in teens and adults have thus far relied on some straightforward math. You take two groups of similar people. You give half the vaccine and half a placebo. Then you wait and see which group has more symptomatic infections. To date, the vaccines have dramatically cut the risk of getting severely ill with COVID for every age group tested.

But COVID infections are falling rapidly in the U.S., and that may make it more difficult for researchers to conduct a similar kind of experiment in children.

The FDA is considering different approaches to figure out whether a vaccine would be effective in kids, including something called an “immunobridging trial.”

In bridging trials, researchers don’t look for infections; rather, they look for proven signs that someone has developed immunity, like antibody levels. Those biomarkers are then compared to the immune responses of younger adults who have demonstrated good protection against infection.

The main advantage of bridging studies is speed. It’s possible to get a snapshot of how the immune system responds to a vaccine within weeks of the final dose.

The drawback is that researchers don’t know exactly what to look for to judge how well the shots are generating protection.

That’s made even more difficult because kids’ immune systems are still developing, so it may be tough to draw direct parallels to adults.

“We don’t know what the serologic correlate of immunity is now. We don’t know how much antibody you have to get in order to be protected. We don’t know what the role of T cells will be,” said H. Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

“I have so much sympathy for the FDA because these are enormous problems, and you have to make a decision,” said Dr. Meissner, who is a member of the FDA’s vaccines and related biological products advisory committee.

Speed vaccines to market, or gather more data?

The plummeting rate of infections in the United States also means that it may be more difficult for the FDA to justify allowing a vaccine on the market for emergency use for children under age 12.

In its recent advisory committee meeting, the agency asked the panel whether it should consider COVID vaccines for children under an EUA or a biologics license application (BLA), aka full approval.

A BLA typically means the agency considers a year or two of data on a new product, rather than just 2 months’ worth. Emergency use also allows products on the market under a looser standard – they “may be” safe and effective, instead of has been proven to be safe and effective.

Several committee members said they didn’t feel the United States was still in an emergency with COVID and couldn’t see the FDA allowing a vaccine to be used in kids that wasn’t given the agency’s highest level of scrutiny, particularly with reports of adverse events like myocarditis coming to light.

“I just want to be sure the price we pay for vaccinating millions of children justifies the side effects, and I don’t think we know that yet,” Dr. Meissner said.

Others acknowledged that there was little risk to kids now with infections on the decline but said that picture could change as variants spread, schools reopen, and colder temperatures force people indoors.

The FDA must decide whether to act based on where we are now or where we could be in a few months.

“I think it’s the million-dollar question right now,” said Hannah Kirking, MD, a medical epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who presented new and unpublished data on COVID’s impact in children to the FDA’s advisory committee.

She said prospective studies tracking the way COVID moves through a household with weekly testing from New York City and Utah had found that children catch and transmit COVID almost as readily as adults. But they don’t usually get as sick as adults do, so their cases are easy to miss.

She also presented the results of blood tests from samples around the country looking for evidence of past infection. In these seroprevalence studies, about 27% of children under age 17 had antibodies to COVID – the most of any age group. So more than 1 in 4 kids already has some natural immunity.

That means the main benefit of vaccinating children might be the protection of others, while they still bear the risks – however tiny.

Some experts felt that wasn’t enough reason to justify mass distribution of the vaccines to kids, and from a regulatory standpoint, it might not be permissible.

“FDA can only approve a medical product in a population if the benefits outweigh the risks in that population,” said Peter Doshi, PhD, assistant professor of pharmaceutical health services research in the University of Maryland’s school of pharmacy, Baltimore.

“If benefits don’t outweigh risks in children, it can’t be indicated for children. Full stop,” said Dr. Doshi, who is also an editor at the BMJ.

He said there’s another way to give children access to vaccines, through an expanded access or compassionate use program. Because most COVID deaths have been in children with underlying health conditions, Dr. Doshi and others said it might make sense to allow expanded access – which would get vaccines to children at high risk for complications – without turning them loose on millions before they are more thoroughly studied.

“It’s not a particularly attractive option for industry, because there’s no money to be made. Your medicine can’t be commercialized under expanded access. The most you can reap is manufacturing cost, which is not a lot,” he said.

Art Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University’s Langone medical center, said the argument for vaccinating children for flu falls along the same lines. The benefit-to-risk ratio is finely balanced in children. The main value of protecting them is to protect others.

“Flu rarely kills young folks. But you’re really trying to protect old folks and that’s the classic example,” he said.

What’s more, he said the idea that children would take on some risk with a vaccine for little personal benefit is oversimplified.

“Yes, you might get vaccinated to prevent harm to others, but those others are providing benefits to you. It’s not a one-way street. I think that’s a little morally distorted,” Mr. Caplan said. “Being able to keep society open benefits kids and adults alike.”

Other committee members felt like it was too early to sound the all-clear on COVID and said the FDA should authorize vaccines for children as quickly as it had for other age groups.

“We are still, I believe, in an emergency situation. I think that when this virus goes into our children, which is what it’s going to do, that will give it an incubator to change,” said Oveta Fuller, PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Fuller said that for the good of the world, Americans needed to vaccinate children to prevent the virus from mutating and creating new and potentially more dangerous variants.

Weighing risk over safety

Beth Thielen, MD, PhD, pediatric infectious disease specialist and virologist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said she had not followed the committee’s discussions, but about once a month she treats kids who are very sick because of the virus – either because of a COVID infection or because of multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), an inflammatory reaction that strikes after infection.

She’s worried about how the virus has already changed. She said the kind of disease she’s seeing in kids now is different than what she saw in the early months of the pandemic.

“In the last couple of months, I’ve actually seen a few cases of severe pulmonary disease, more similar to adult disease in children,” Dr. Thielen said. “I see on the horizon that we could start seeing more significant disease in young people, and then the risks of being unvaccinated go up substantially.”

But she also knows nobody has a crystal ball, and right now, everything seems to be trending in the right direction with COVID. That makes the risk-to-benefit consideration murkier.

“The question in my mind is, what is the risk of side effects from the vaccine?” she said. “I think we really need to know what the safety profile of vaccine looks like in children because we do have a decent understanding now what risk from disease looks like, because it’s small, but we are seeing it.”

Dr. Thielen said she’ll be keeping an eye on the next meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for more answers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insomnia in children tied to mood and anxiety disorders in adulthood

, new research indicates. However, insomnia symptoms in childhood that remit in the transition to adolescence do not confer increased risk of mood or anxiety disorders later on, the study found.

“As insomnia symptoms may precipitate or maintain internalizing disorders, our findings further reinforce the need for early sleep interventions to prevent future mental health disorders,” said lead investigator Julio Fernandez-Mendoza, PhD, associate professor at Penn State University, Hershey.

He presented his research at Virtual SLEEP 2021, the 35th annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Results ‘very clear’

The findings are based on data from the Penn State Child Cohort, a longitudinal, population-based sample of 700 children with a median age of 9 years, including 421 who were followed up 8 years later as adolescents (median age, 16 years) and 502 who were followed up 15 years later as young adults (median age, 24 years).

The data are “very clear that the risk of having internalizing disorders in young adulthood associated with having persistent insomnia symptoms, since childhood through adolescence into young adulthood,” Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza said in his presentation.

A persistent developmental trajectory was associated with a threefold increased risk of adult internalizing disorder (hazard ratio, 3.19).

The risk of having an internalizing disorder in young adulthood associated with newly developing (incident) insomnia symptoms is about twofold higher (HR, 1.94), whereas the risk associated with the waxing and waning pattern of insomnia is 1.5-fold (HR, 1.53) higher and only marginally significant, he reported.

An equally important finding, said Dr. Fernandez-Mendoza, is that those who had remitted insomnia symptoms in the transition to adolescence and throughout young adulthood were not at increased risk of having an internalizing disorder in young adulthood.

“Insomnia symptoms in a persistent manner associated with long-term adverse mental health outcomes, but remission of those insomnia symptoms associated with a good prognosis,” he said.

It’s also important to note, he said, that about 40% of children do not outgrow their insomnia symptoms in the transition to adolescence and are at risk of developing mental health disorders later on during early adulthood.

Reached for comment, Nitun Verma, MD, a spokesperson for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, said: “There is a connection with mood and anxiety disorders with sleep, especially insomnia. This is a good reminder that reviewing someone’s sleep habits should always be a part of assessing someone’s mental health.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research indicates. However, insomnia symptoms in childhood that remit in the transition to adolescence do not confer increased risk of mood or anxiety disorders later on, the study found.