User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Four mental health trajectories in youth: Predicting persistent psychopathology

A study that tracked psychopathology in 13,000 children and adolescents found that

Investigators also found a strong correlation between new incidence of high psychopathology and externalizing problems such as hyperactivity. “It is of paramount importance to identify factors that distinguish those with persisting problems and escalating trajectories so that resources can be appropriately directed,” wrote the authors of the study published online in JAMA Network Open.

Recent studies have shown that concurrent and sequential comorbidity of psychiatric disorders are very common in adult populations, lead author Colm Healy, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher for psychiatry with the University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ireland, said in an interview.

The speculation is that this occurs in early life when psychiatry symptoms experience high fluidity. “This presents a complex scenario to model, where young people’s mental health appears to shift and change across development. Few investigations to date have had the data available to examine these trajectories over the full range of child development,” said Dr. Healy.

He and his colleagues attempted to map the profiles and trajectories of psychopathology in children and adolescents, using latent profile transition analysis (LPTA), a person-centered method, to assess comorbidity and movement in the various phases of childhood development.

“The idea behind person-centered methods such as LTPA is that it identifies unobserved subgroups of participants who respond similarly to specific variables – in this case responses to a broad measure of psychopathology,” explained Dr. Healy.

The study included 7,507 children from the child sample (ages 3, 5, and 9 years) and 6,039 children from the adolescent sample (ages 9, 13, and 17 or 18 years). Data analysis took place from October 2020 to September 2021.

Dr. Healy and colleagues in a supplementary investigation compared cohorts at age 9 years to look for sex and generational differences.

Four developmental profiles

Researchers identified 4 distinct developmental profies for person-centered psychopathological trajectories: no psychopathology (incidence range, 60%-70%), high psychopathology (incidence range, 3%-5%), externalizing problems (incidence range, 15%-25%), and internalizing problems (incidence range, 7%-12%).

Internalizing problems reflect issues with peers and emotional problems whereas externalizing problems more closely associate with hyperactivity and conduct.

Less than 5% of the youth studied experienced persistent symptoms. However, 48.6% in the child cohort and 44.1% in the adolescent cohort moved into one of the 3 psychopathology profiles (high psychopathology, externalizing, internalizing problems) at some point in development.

The spread of trajectories was more diverse in the child cohort, said Dr. Healy. “Children ebbed and flowed between the different profiles over time with a large proportion falling into one of the psychopathology categories and then switching between these profiles.” Switching was also evident in the adolescent cohort but to a lesser extent, he said.

Externalizing problems link to high psychopathology

Rates of remittance were higher among individuals in both cohorts for internalizing problems, compared with externalizing problems.

It’s possible that for some of these young people, internalizing problems are a reaction to environmental stressors such as bullying,” said Dr. Healy. “When that stress is relieved, the internalizing problems may dissipate.”

In a clinically relevant finding, children with externalizing problems (age 5, 129 [61.3%] and age 9, 95 [74.3%]) were more likely to present with new incidents of high psychopathology. This was also true in the adolescent group (age 13, 129 [91.1%] and age 17, 146 [89.9%]).

This suggests that a proportion of youth with externalizing problems have an escalating trajectory of psychopathology. “Thus, it may be possible to distinguish those with an escalating trajectory from a stable or remitting trajectory. The specific distinguishing factors require further investigation, but it has been observed before that some of those reporting externalizing problems in early life continue to have difficulties into later life,” noted Dr. Healy.

A combination of environmental or biological factors may explain this escalation, which could respond to early intervention, he said.

Overall, few children in the study transitioned directly from no psychopathology to high psychopathology.

Differences between boys, girls

In both cohorts, investigators noticed significant differences between the sexes.

Boys in childhood made up a larger proportion of the three psychopathology profiles. But by late adolescence, girls made up a larger proportion of the internalizing profile whereas boys made up a larger proportion of the externalizing profile. “These differences were in line with our expectations,” said Dr. Healy.

Trajectories also differed among boys and girls. In childhood, girls had a higher percentage of de-escalating trajectories relative to boys. “More girls than boys in the psychopathology profiles switched to a non or less severe profile. In adolescence, differences in trajectories were less obvious, with the exception that girls were more likely than boys to transition to internalizing problems from all of the other profiles at age 17,” said Dr. Healy.

Most young people who experience psychopathology will eventually see an improvement in symptoms, noted Dr. Healy. Next steps are to identify markers that distinguish individuals with persistent trajectories from remitting trajectories at the different phases of development, he said.

Study draws mixed reviews

Clinical psychiatrists not involved in the study had varying reactions to the results.

“This study is notable for its data-driven and powerful illustration of how childhood and adolescence are dynamic periods during which psychiatric symptoms can emerge and evolve,” said Sunny X. Tang, MD, a psychiatrist and an assistant professor at the Institute of Behavioral Science and the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York.

The clinical call for action is for person-centered mental health screening to be a routine part of pediatric and adolescent primary care or school-based services, noted Dr. Tang.

Paul S. Nestadt, MD, an assistant professor and public mental health researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, did not think the study would have a significant impact on clinical practice.

He noted that Dr. Healy and coauthors found that some children stayed true to type, but many fluctuated between the four profile groups. The finding that fluctuation occurred more frequently in younger children is not surprising “and is consistent with what we know about the ‘moving targets’ that make diagnosing children so difficult,” said Dr. Nestadt.

“It would have been helpful to have identified clinical indicators of likely persistence in psychopathology, but the measure employed here did not allow that. It is also frustrating to not have any information on treatment, such that we cannot know whether the children who shifted to ‘no psychopathology’ did so because of treatment or spontaneously,” he added.

Victor M. Fornari, MD, MS, director of the Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry at The Zucker Hillside Hospital and Cohen’s Children’s Medical Center, New York, said the study is an important contribution to understanding the development of psychopathology during childhood.

“Generally, it is felt that nearly one in five youth will meet criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder by the age of 18. It is well known that externalizing disorders like ADHD manifest earlier in childhood and that depression often manifests later in adolescence,” he said.

No disclosures were reported.

A study that tracked psychopathology in 13,000 children and adolescents found that

Investigators also found a strong correlation between new incidence of high psychopathology and externalizing problems such as hyperactivity. “It is of paramount importance to identify factors that distinguish those with persisting problems and escalating trajectories so that resources can be appropriately directed,” wrote the authors of the study published online in JAMA Network Open.

Recent studies have shown that concurrent and sequential comorbidity of psychiatric disorders are very common in adult populations, lead author Colm Healy, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher for psychiatry with the University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ireland, said in an interview.

The speculation is that this occurs in early life when psychiatry symptoms experience high fluidity. “This presents a complex scenario to model, where young people’s mental health appears to shift and change across development. Few investigations to date have had the data available to examine these trajectories over the full range of child development,” said Dr. Healy.

He and his colleagues attempted to map the profiles and trajectories of psychopathology in children and adolescents, using latent profile transition analysis (LPTA), a person-centered method, to assess comorbidity and movement in the various phases of childhood development.

“The idea behind person-centered methods such as LTPA is that it identifies unobserved subgroups of participants who respond similarly to specific variables – in this case responses to a broad measure of psychopathology,” explained Dr. Healy.

The study included 7,507 children from the child sample (ages 3, 5, and 9 years) and 6,039 children from the adolescent sample (ages 9, 13, and 17 or 18 years). Data analysis took place from October 2020 to September 2021.

Dr. Healy and colleagues in a supplementary investigation compared cohorts at age 9 years to look for sex and generational differences.

Four developmental profiles

Researchers identified 4 distinct developmental profies for person-centered psychopathological trajectories: no psychopathology (incidence range, 60%-70%), high psychopathology (incidence range, 3%-5%), externalizing problems (incidence range, 15%-25%), and internalizing problems (incidence range, 7%-12%).

Internalizing problems reflect issues with peers and emotional problems whereas externalizing problems more closely associate with hyperactivity and conduct.

Less than 5% of the youth studied experienced persistent symptoms. However, 48.6% in the child cohort and 44.1% in the adolescent cohort moved into one of the 3 psychopathology profiles (high psychopathology, externalizing, internalizing problems) at some point in development.

The spread of trajectories was more diverse in the child cohort, said Dr. Healy. “Children ebbed and flowed between the different profiles over time with a large proportion falling into one of the psychopathology categories and then switching between these profiles.” Switching was also evident in the adolescent cohort but to a lesser extent, he said.

Externalizing problems link to high psychopathology

Rates of remittance were higher among individuals in both cohorts for internalizing problems, compared with externalizing problems.

It’s possible that for some of these young people, internalizing problems are a reaction to environmental stressors such as bullying,” said Dr. Healy. “When that stress is relieved, the internalizing problems may dissipate.”

In a clinically relevant finding, children with externalizing problems (age 5, 129 [61.3%] and age 9, 95 [74.3%]) were more likely to present with new incidents of high psychopathology. This was also true in the adolescent group (age 13, 129 [91.1%] and age 17, 146 [89.9%]).

This suggests that a proportion of youth with externalizing problems have an escalating trajectory of psychopathology. “Thus, it may be possible to distinguish those with an escalating trajectory from a stable or remitting trajectory. The specific distinguishing factors require further investigation, but it has been observed before that some of those reporting externalizing problems in early life continue to have difficulties into later life,” noted Dr. Healy.

A combination of environmental or biological factors may explain this escalation, which could respond to early intervention, he said.

Overall, few children in the study transitioned directly from no psychopathology to high psychopathology.

Differences between boys, girls

In both cohorts, investigators noticed significant differences between the sexes.

Boys in childhood made up a larger proportion of the three psychopathology profiles. But by late adolescence, girls made up a larger proportion of the internalizing profile whereas boys made up a larger proportion of the externalizing profile. “These differences were in line with our expectations,” said Dr. Healy.

Trajectories also differed among boys and girls. In childhood, girls had a higher percentage of de-escalating trajectories relative to boys. “More girls than boys in the psychopathology profiles switched to a non or less severe profile. In adolescence, differences in trajectories were less obvious, with the exception that girls were more likely than boys to transition to internalizing problems from all of the other profiles at age 17,” said Dr. Healy.

Most young people who experience psychopathology will eventually see an improvement in symptoms, noted Dr. Healy. Next steps are to identify markers that distinguish individuals with persistent trajectories from remitting trajectories at the different phases of development, he said.

Study draws mixed reviews

Clinical psychiatrists not involved in the study had varying reactions to the results.

“This study is notable for its data-driven and powerful illustration of how childhood and adolescence are dynamic periods during which psychiatric symptoms can emerge and evolve,” said Sunny X. Tang, MD, a psychiatrist and an assistant professor at the Institute of Behavioral Science and the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York.

The clinical call for action is for person-centered mental health screening to be a routine part of pediatric and adolescent primary care or school-based services, noted Dr. Tang.

Paul S. Nestadt, MD, an assistant professor and public mental health researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, did not think the study would have a significant impact on clinical practice.

He noted that Dr. Healy and coauthors found that some children stayed true to type, but many fluctuated between the four profile groups. The finding that fluctuation occurred more frequently in younger children is not surprising “and is consistent with what we know about the ‘moving targets’ that make diagnosing children so difficult,” said Dr. Nestadt.

“It would have been helpful to have identified clinical indicators of likely persistence in psychopathology, but the measure employed here did not allow that. It is also frustrating to not have any information on treatment, such that we cannot know whether the children who shifted to ‘no psychopathology’ did so because of treatment or spontaneously,” he added.

Victor M. Fornari, MD, MS, director of the Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry at The Zucker Hillside Hospital and Cohen’s Children’s Medical Center, New York, said the study is an important contribution to understanding the development of psychopathology during childhood.

“Generally, it is felt that nearly one in five youth will meet criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder by the age of 18. It is well known that externalizing disorders like ADHD manifest earlier in childhood and that depression often manifests later in adolescence,” he said.

No disclosures were reported.

A study that tracked psychopathology in 13,000 children and adolescents found that

Investigators also found a strong correlation between new incidence of high psychopathology and externalizing problems such as hyperactivity. “It is of paramount importance to identify factors that distinguish those with persisting problems and escalating trajectories so that resources can be appropriately directed,” wrote the authors of the study published online in JAMA Network Open.

Recent studies have shown that concurrent and sequential comorbidity of psychiatric disorders are very common in adult populations, lead author Colm Healy, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher for psychiatry with the University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ireland, said in an interview.

The speculation is that this occurs in early life when psychiatry symptoms experience high fluidity. “This presents a complex scenario to model, where young people’s mental health appears to shift and change across development. Few investigations to date have had the data available to examine these trajectories over the full range of child development,” said Dr. Healy.

He and his colleagues attempted to map the profiles and trajectories of psychopathology in children and adolescents, using latent profile transition analysis (LPTA), a person-centered method, to assess comorbidity and movement in the various phases of childhood development.

“The idea behind person-centered methods such as LTPA is that it identifies unobserved subgroups of participants who respond similarly to specific variables – in this case responses to a broad measure of psychopathology,” explained Dr. Healy.

The study included 7,507 children from the child sample (ages 3, 5, and 9 years) and 6,039 children from the adolescent sample (ages 9, 13, and 17 or 18 years). Data analysis took place from October 2020 to September 2021.

Dr. Healy and colleagues in a supplementary investigation compared cohorts at age 9 years to look for sex and generational differences.

Four developmental profiles

Researchers identified 4 distinct developmental profies for person-centered psychopathological trajectories: no psychopathology (incidence range, 60%-70%), high psychopathology (incidence range, 3%-5%), externalizing problems (incidence range, 15%-25%), and internalizing problems (incidence range, 7%-12%).

Internalizing problems reflect issues with peers and emotional problems whereas externalizing problems more closely associate with hyperactivity and conduct.

Less than 5% of the youth studied experienced persistent symptoms. However, 48.6% in the child cohort and 44.1% in the adolescent cohort moved into one of the 3 psychopathology profiles (high psychopathology, externalizing, internalizing problems) at some point in development.

The spread of trajectories was more diverse in the child cohort, said Dr. Healy. “Children ebbed and flowed between the different profiles over time with a large proportion falling into one of the psychopathology categories and then switching between these profiles.” Switching was also evident in the adolescent cohort but to a lesser extent, he said.

Externalizing problems link to high psychopathology

Rates of remittance were higher among individuals in both cohorts for internalizing problems, compared with externalizing problems.

It’s possible that for some of these young people, internalizing problems are a reaction to environmental stressors such as bullying,” said Dr. Healy. “When that stress is relieved, the internalizing problems may dissipate.”

In a clinically relevant finding, children with externalizing problems (age 5, 129 [61.3%] and age 9, 95 [74.3%]) were more likely to present with new incidents of high psychopathology. This was also true in the adolescent group (age 13, 129 [91.1%] and age 17, 146 [89.9%]).

This suggests that a proportion of youth with externalizing problems have an escalating trajectory of psychopathology. “Thus, it may be possible to distinguish those with an escalating trajectory from a stable or remitting trajectory. The specific distinguishing factors require further investigation, but it has been observed before that some of those reporting externalizing problems in early life continue to have difficulties into later life,” noted Dr. Healy.

A combination of environmental or biological factors may explain this escalation, which could respond to early intervention, he said.

Overall, few children in the study transitioned directly from no psychopathology to high psychopathology.

Differences between boys, girls

In both cohorts, investigators noticed significant differences between the sexes.

Boys in childhood made up a larger proportion of the three psychopathology profiles. But by late adolescence, girls made up a larger proportion of the internalizing profile whereas boys made up a larger proportion of the externalizing profile. “These differences were in line with our expectations,” said Dr. Healy.

Trajectories also differed among boys and girls. In childhood, girls had a higher percentage of de-escalating trajectories relative to boys. “More girls than boys in the psychopathology profiles switched to a non or less severe profile. In adolescence, differences in trajectories were less obvious, with the exception that girls were more likely than boys to transition to internalizing problems from all of the other profiles at age 17,” said Dr. Healy.

Most young people who experience psychopathology will eventually see an improvement in symptoms, noted Dr. Healy. Next steps are to identify markers that distinguish individuals with persistent trajectories from remitting trajectories at the different phases of development, he said.

Study draws mixed reviews

Clinical psychiatrists not involved in the study had varying reactions to the results.

“This study is notable for its data-driven and powerful illustration of how childhood and adolescence are dynamic periods during which psychiatric symptoms can emerge and evolve,” said Sunny X. Tang, MD, a psychiatrist and an assistant professor at the Institute of Behavioral Science and the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York.

The clinical call for action is for person-centered mental health screening to be a routine part of pediatric and adolescent primary care or school-based services, noted Dr. Tang.

Paul S. Nestadt, MD, an assistant professor and public mental health researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, did not think the study would have a significant impact on clinical practice.

He noted that Dr. Healy and coauthors found that some children stayed true to type, but many fluctuated between the four profile groups. The finding that fluctuation occurred more frequently in younger children is not surprising “and is consistent with what we know about the ‘moving targets’ that make diagnosing children so difficult,” said Dr. Nestadt.

“It would have been helpful to have identified clinical indicators of likely persistence in psychopathology, but the measure employed here did not allow that. It is also frustrating to not have any information on treatment, such that we cannot know whether the children who shifted to ‘no psychopathology’ did so because of treatment or spontaneously,” he added.

Victor M. Fornari, MD, MS, director of the Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry at The Zucker Hillside Hospital and Cohen’s Children’s Medical Center, New York, said the study is an important contribution to understanding the development of psychopathology during childhood.

“Generally, it is felt that nearly one in five youth will meet criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder by the age of 18. It is well known that externalizing disorders like ADHD manifest earlier in childhood and that depression often manifests later in adolescence,” he said.

No disclosures were reported.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Measles outbreaks: Protecting your patients during international travel

The U.S. immunization program is one of the best public health success stories. Physicians who provide care for children are familiar with the routine childhood immunization schedule and administer a measles-containing vaccine at age-appropriate times. Thanks to its rigorous implementation and acceptance, endemic measles (absence of continuous virus transmission for > 1 year) was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Loss of this status was in jeopardy in 2019 when 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states (7 were multistate outbreaks). That year, 1,163 cases were reported.1 Most cases occurred in unvaccinated persons (89%) and 81 cases were imported of which 54 were in U.S. citizens returning from international travel. All outbreaks were linked to travel. Fortunately, the outbreaks were controlled prior to the elimination deadline, or the United States would have lost its measles elimination status. Restrictions on travel because of COVID-19 have relaxed significantly since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in increased regional and international travel. Multiple countries, including the United States noted a decline in routine immunizations rates during the last 2 years. Recent U.S. data for the 2020-2021 school year indicates that MMR immunizations rates (two doses) for kindergarteners declined to 93.9% (range 78.9% to > 98.9%), while the overall percentage of those students with an exemption remained low at 2.2%. Vaccine coverage greater than 95% was reported in only 16 states. Coverage of less than 90% was reported in seven states and the District of Columbia (Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).2 Vaccine coverage should be 95% or higher to maintain herd immunity and control outbreaks.

Why is measles prevention so important? Many physicians practicing in the United States today have never seen a case or know its potential complications. I saw my first case as a resident in an immigrant child. It took our training director to point out the subtle signs and symptoms. It was the first time I saw Kolpik spots. Measles is transmitted person to person via large respiratory droplets and less often by airborne spread. It is highly contagious for susceptible individuals with an attack rate of 90%. In this case, a medical student on the team developed symptoms about 10 days later. Six years would pass before I diagnosed my next case of measles. An HIV patient acquired it after close contact with someone who was in the prodromal stage. He presented with the 3 C’s: Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, in addition to fever and an erythematous rash. He did not recover from complications of the disease.

Prior to the routine administration of a measles vaccine, 3-4 million cases with almost 500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. Worldwide, 35 million cases and more than 6 million deaths occurred each year. Here, most patients recover completely; however, complications including otitis media, pneumonia, croup, and encephalitis can develop. Complications commonly occur in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Groups with the highest fatality rates include children aged less than 5 years, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women. Worldwide, fatality rates are dependent on the patients underlying nutritional and health status in addition to the quality of health care available.3

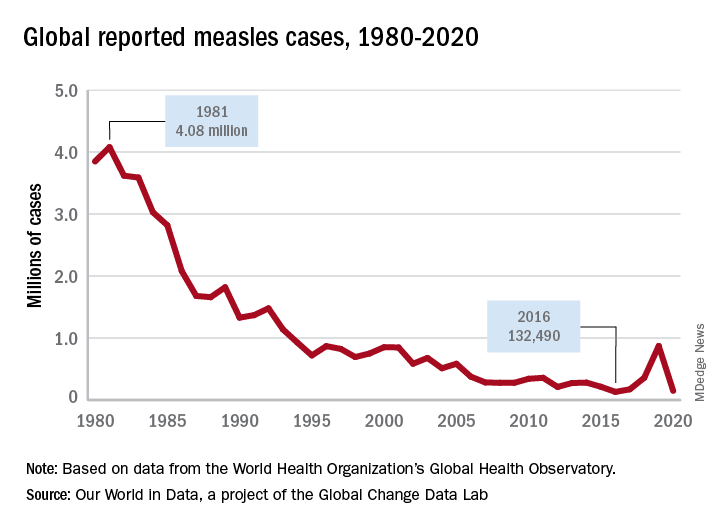

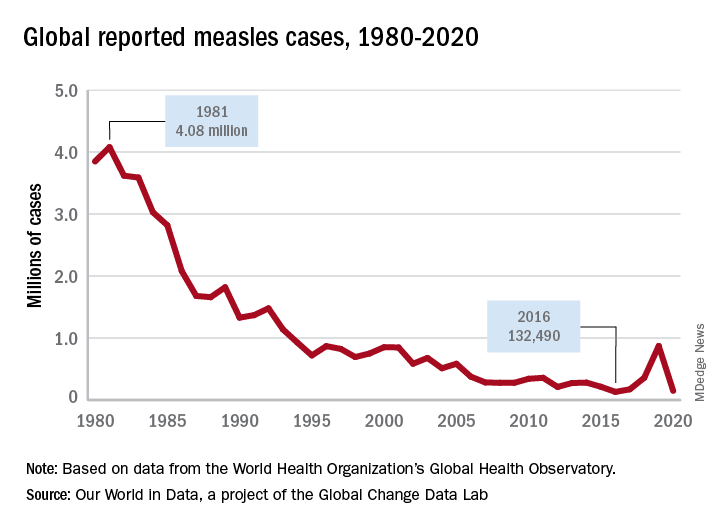

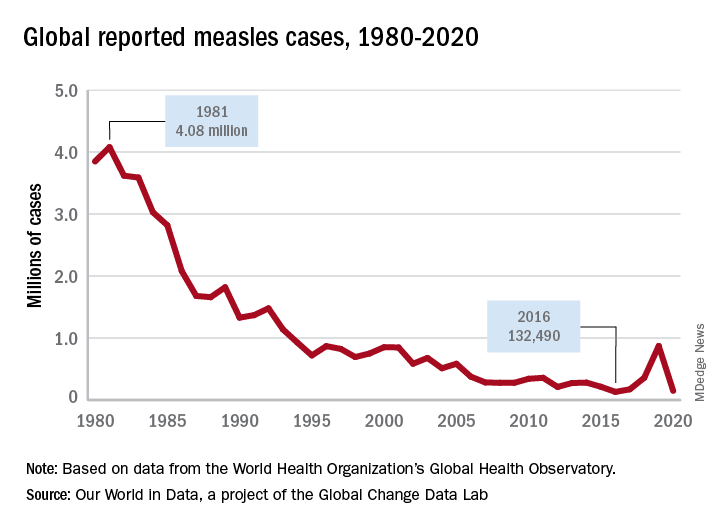

Measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 and cases began to decline (Figure 1). There was a resurgence in 1989 but it was not limited to the United States. The cause of the U.S. resurgence was multifactorial: Widespread viral transmission among unvaccinated preschool-age children residing in inner cities, outbreaks in vaccinated school-age children, outbreaks in students and personnel on college campuses, and primary vaccine failure (2%-5% of recipients failed to have an adequate response). In 1989, to help prevent future outbreaks, the United States recommended a two-dose schedule for measles and in 1993, the Vaccines for Children Program, a federally funded program, was established to improve access to vaccines for all children.

What is going on internationally?

Figure 2 lists the top 10 countries with current measles outbreaks.

Most countries on the list may not be typical travel destinations for tourists; however, they are common destinations for individuals visiting friends and relatives after immigrating to the United States. In contrast to the United States, most countries with limited resources and infrastructure have mass-vaccination campaigns to ensure vaccine administration to large segments of the population. They too have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By report, at least 41 countries delayed implementation of their measles campaign in 2020 and 2021, thus, leading to the potential for even larger outbreaks.4

Progress toward the global elimination of measles is evidenced by the following: All 194 countries now include one dose of measles in their routine schedules; between 2000 and 2019 coverage of one dose of measles increased from 72% to 85% and countries with more than 90% coverage increased from 45% to 63%. Finally, the number of countries offering two doses of measles increased from 50% to 91% and vaccine coverage increased from 18% to 71% over the same time period.3

What can you do for your patients and their parents before they travel abroad?

- Inform all staff that the MMR vaccine can be administered to children as young as 6 months and at times other than those listed on the routine immunization schedule. This will help avoid parents seeking vaccine being denied an appointment.

- Children 6-11 months need 1 dose of MMR. Two additional doses will still need to be administered at the routine time.

- Children 12 months or older need 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart.

- If yellow fever vaccine is needed, coordinate administration with a travel medicine clinic since both are live vaccines and must be given on the same day.

- Any person born after 1956 should have 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart if they have no evidence of immunity.

- Encourage parents to always inform you and your staff of any international travel plans.

Moving forward, remember this increased global activity and the presence of inadequately vaccinated individuals/communities keeps the United States at continued risk for measles outbreaks. The source of the next outbreak may only be one plane ride away.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated 6/29/22.

References

1. Patel M et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-6.

2. Seither R et al. MMWR. 2022 Apr 22;71(16):561-8.

3. Gastañaduy PA et al. J Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 30;224(12 Suppl 2):S420-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa793.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). http://www.CDC.gov/Measles.

The U.S. immunization program is one of the best public health success stories. Physicians who provide care for children are familiar with the routine childhood immunization schedule and administer a measles-containing vaccine at age-appropriate times. Thanks to its rigorous implementation and acceptance, endemic measles (absence of continuous virus transmission for > 1 year) was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Loss of this status was in jeopardy in 2019 when 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states (7 were multistate outbreaks). That year, 1,163 cases were reported.1 Most cases occurred in unvaccinated persons (89%) and 81 cases were imported of which 54 were in U.S. citizens returning from international travel. All outbreaks were linked to travel. Fortunately, the outbreaks were controlled prior to the elimination deadline, or the United States would have lost its measles elimination status. Restrictions on travel because of COVID-19 have relaxed significantly since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in increased regional and international travel. Multiple countries, including the United States noted a decline in routine immunizations rates during the last 2 years. Recent U.S. data for the 2020-2021 school year indicates that MMR immunizations rates (two doses) for kindergarteners declined to 93.9% (range 78.9% to > 98.9%), while the overall percentage of those students with an exemption remained low at 2.2%. Vaccine coverage greater than 95% was reported in only 16 states. Coverage of less than 90% was reported in seven states and the District of Columbia (Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).2 Vaccine coverage should be 95% or higher to maintain herd immunity and control outbreaks.

Why is measles prevention so important? Many physicians practicing in the United States today have never seen a case or know its potential complications. I saw my first case as a resident in an immigrant child. It took our training director to point out the subtle signs and symptoms. It was the first time I saw Kolpik spots. Measles is transmitted person to person via large respiratory droplets and less often by airborne spread. It is highly contagious for susceptible individuals with an attack rate of 90%. In this case, a medical student on the team developed symptoms about 10 days later. Six years would pass before I diagnosed my next case of measles. An HIV patient acquired it after close contact with someone who was in the prodromal stage. He presented with the 3 C’s: Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, in addition to fever and an erythematous rash. He did not recover from complications of the disease.

Prior to the routine administration of a measles vaccine, 3-4 million cases with almost 500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. Worldwide, 35 million cases and more than 6 million deaths occurred each year. Here, most patients recover completely; however, complications including otitis media, pneumonia, croup, and encephalitis can develop. Complications commonly occur in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Groups with the highest fatality rates include children aged less than 5 years, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women. Worldwide, fatality rates are dependent on the patients underlying nutritional and health status in addition to the quality of health care available.3

Measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 and cases began to decline (Figure 1). There was a resurgence in 1989 but it was not limited to the United States. The cause of the U.S. resurgence was multifactorial: Widespread viral transmission among unvaccinated preschool-age children residing in inner cities, outbreaks in vaccinated school-age children, outbreaks in students and personnel on college campuses, and primary vaccine failure (2%-5% of recipients failed to have an adequate response). In 1989, to help prevent future outbreaks, the United States recommended a two-dose schedule for measles and in 1993, the Vaccines for Children Program, a federally funded program, was established to improve access to vaccines for all children.

What is going on internationally?

Figure 2 lists the top 10 countries with current measles outbreaks.

Most countries on the list may not be typical travel destinations for tourists; however, they are common destinations for individuals visiting friends and relatives after immigrating to the United States. In contrast to the United States, most countries with limited resources and infrastructure have mass-vaccination campaigns to ensure vaccine administration to large segments of the population. They too have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By report, at least 41 countries delayed implementation of their measles campaign in 2020 and 2021, thus, leading to the potential for even larger outbreaks.4

Progress toward the global elimination of measles is evidenced by the following: All 194 countries now include one dose of measles in their routine schedules; between 2000 and 2019 coverage of one dose of measles increased from 72% to 85% and countries with more than 90% coverage increased from 45% to 63%. Finally, the number of countries offering two doses of measles increased from 50% to 91% and vaccine coverage increased from 18% to 71% over the same time period.3

What can you do for your patients and their parents before they travel abroad?

- Inform all staff that the MMR vaccine can be administered to children as young as 6 months and at times other than those listed on the routine immunization schedule. This will help avoid parents seeking vaccine being denied an appointment.

- Children 6-11 months need 1 dose of MMR. Two additional doses will still need to be administered at the routine time.

- Children 12 months or older need 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart.

- If yellow fever vaccine is needed, coordinate administration with a travel medicine clinic since both are live vaccines and must be given on the same day.

- Any person born after 1956 should have 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart if they have no evidence of immunity.

- Encourage parents to always inform you and your staff of any international travel plans.

Moving forward, remember this increased global activity and the presence of inadequately vaccinated individuals/communities keeps the United States at continued risk for measles outbreaks. The source of the next outbreak may only be one plane ride away.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated 6/29/22.

References

1. Patel M et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-6.

2. Seither R et al. MMWR. 2022 Apr 22;71(16):561-8.

3. Gastañaduy PA et al. J Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 30;224(12 Suppl 2):S420-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa793.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). http://www.CDC.gov/Measles.

The U.S. immunization program is one of the best public health success stories. Physicians who provide care for children are familiar with the routine childhood immunization schedule and administer a measles-containing vaccine at age-appropriate times. Thanks to its rigorous implementation and acceptance, endemic measles (absence of continuous virus transmission for > 1 year) was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Loss of this status was in jeopardy in 2019 when 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states (7 were multistate outbreaks). That year, 1,163 cases were reported.1 Most cases occurred in unvaccinated persons (89%) and 81 cases were imported of which 54 were in U.S. citizens returning from international travel. All outbreaks were linked to travel. Fortunately, the outbreaks were controlled prior to the elimination deadline, or the United States would have lost its measles elimination status. Restrictions on travel because of COVID-19 have relaxed significantly since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in increased regional and international travel. Multiple countries, including the United States noted a decline in routine immunizations rates during the last 2 years. Recent U.S. data for the 2020-2021 school year indicates that MMR immunizations rates (two doses) for kindergarteners declined to 93.9% (range 78.9% to > 98.9%), while the overall percentage of those students with an exemption remained low at 2.2%. Vaccine coverage greater than 95% was reported in only 16 states. Coverage of less than 90% was reported in seven states and the District of Columbia (Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).2 Vaccine coverage should be 95% or higher to maintain herd immunity and control outbreaks.

Why is measles prevention so important? Many physicians practicing in the United States today have never seen a case or know its potential complications. I saw my first case as a resident in an immigrant child. It took our training director to point out the subtle signs and symptoms. It was the first time I saw Kolpik spots. Measles is transmitted person to person via large respiratory droplets and less often by airborne spread. It is highly contagious for susceptible individuals with an attack rate of 90%. In this case, a medical student on the team developed symptoms about 10 days later. Six years would pass before I diagnosed my next case of measles. An HIV patient acquired it after close contact with someone who was in the prodromal stage. He presented with the 3 C’s: Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, in addition to fever and an erythematous rash. He did not recover from complications of the disease.

Prior to the routine administration of a measles vaccine, 3-4 million cases with almost 500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. Worldwide, 35 million cases and more than 6 million deaths occurred each year. Here, most patients recover completely; however, complications including otitis media, pneumonia, croup, and encephalitis can develop. Complications commonly occur in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Groups with the highest fatality rates include children aged less than 5 years, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women. Worldwide, fatality rates are dependent on the patients underlying nutritional and health status in addition to the quality of health care available.3

Measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 and cases began to decline (Figure 1). There was a resurgence in 1989 but it was not limited to the United States. The cause of the U.S. resurgence was multifactorial: Widespread viral transmission among unvaccinated preschool-age children residing in inner cities, outbreaks in vaccinated school-age children, outbreaks in students and personnel on college campuses, and primary vaccine failure (2%-5% of recipients failed to have an adequate response). In 1989, to help prevent future outbreaks, the United States recommended a two-dose schedule for measles and in 1993, the Vaccines for Children Program, a federally funded program, was established to improve access to vaccines for all children.

What is going on internationally?

Figure 2 lists the top 10 countries with current measles outbreaks.

Most countries on the list may not be typical travel destinations for tourists; however, they are common destinations for individuals visiting friends and relatives after immigrating to the United States. In contrast to the United States, most countries with limited resources and infrastructure have mass-vaccination campaigns to ensure vaccine administration to large segments of the population. They too have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By report, at least 41 countries delayed implementation of their measles campaign in 2020 and 2021, thus, leading to the potential for even larger outbreaks.4

Progress toward the global elimination of measles is evidenced by the following: All 194 countries now include one dose of measles in their routine schedules; between 2000 and 2019 coverage of one dose of measles increased from 72% to 85% and countries with more than 90% coverage increased from 45% to 63%. Finally, the number of countries offering two doses of measles increased from 50% to 91% and vaccine coverage increased from 18% to 71% over the same time period.3

What can you do for your patients and their parents before they travel abroad?

- Inform all staff that the MMR vaccine can be administered to children as young as 6 months and at times other than those listed on the routine immunization schedule. This will help avoid parents seeking vaccine being denied an appointment.

- Children 6-11 months need 1 dose of MMR. Two additional doses will still need to be administered at the routine time.

- Children 12 months or older need 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart.

- If yellow fever vaccine is needed, coordinate administration with a travel medicine clinic since both are live vaccines and must be given on the same day.

- Any person born after 1956 should have 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart if they have no evidence of immunity.

- Encourage parents to always inform you and your staff of any international travel plans.

Moving forward, remember this increased global activity and the presence of inadequately vaccinated individuals/communities keeps the United States at continued risk for measles outbreaks. The source of the next outbreak may only be one plane ride away.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated 6/29/22.

References

1. Patel M et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-6.

2. Seither R et al. MMWR. 2022 Apr 22;71(16):561-8.

3. Gastañaduy PA et al. J Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 30;224(12 Suppl 2):S420-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa793.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). http://www.CDC.gov/Measles.

FDA-cleared panties could reduce STI risk during oral sex

.

The underwear, sold as Lorals for Protection, are single-use, vanilla-scented, natural latex panties that cover the genitals and anus and block the transfer of bodily fluids during oral sex, according to the company website. They sell in packages of four for $25.

The FDA didn’t run human clinical trials but granted authorization after the company gave it data about the product, The New York Times reported.

“The FDA’s authorization of this product gives people another option to protect against STIs during oral sex,” said Courtney Lias, PhD, director of the FDA office that led the review of the underwear.

Previously, the FDA authorized oral dams to prevent the spread of STIs during oral sex. Oral dams, sometimes called oral sex condoms, are thin latex barriers that go between one partner’s mouth and the other person’s genitals. The dams haven’t been widely used, partly because a person has to hold the dam in place during sex, unlike the panties.

“They’re extremely unpopular,” Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told the Times. “I mean, honestly, could there be anything less sexy than a dental dam?”Melanie Cristol said she came up with the idea for the panties after discovering on her 2014 honeymoon that she had an infection that could be sexually transmitted.

“I wanted to feel sexy and confident and use something that was made with my body and actual sex in mind,” she told the Times.

The panties are made of material about as thin as a condom and form a seal on the thigh to keep fluids inside, she said.

Dr. Marrazzo said the panties are an advancement because there are few options for safe oral sex. She noted that some teenagers have their first sexual experience with oral sex and that the panties could reduce anxiety for people of all ages.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

.

The underwear, sold as Lorals for Protection, are single-use, vanilla-scented, natural latex panties that cover the genitals and anus and block the transfer of bodily fluids during oral sex, according to the company website. They sell in packages of four for $25.

The FDA didn’t run human clinical trials but granted authorization after the company gave it data about the product, The New York Times reported.

“The FDA’s authorization of this product gives people another option to protect against STIs during oral sex,” said Courtney Lias, PhD, director of the FDA office that led the review of the underwear.

Previously, the FDA authorized oral dams to prevent the spread of STIs during oral sex. Oral dams, sometimes called oral sex condoms, are thin latex barriers that go between one partner’s mouth and the other person’s genitals. The dams haven’t been widely used, partly because a person has to hold the dam in place during sex, unlike the panties.

“They’re extremely unpopular,” Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told the Times. “I mean, honestly, could there be anything less sexy than a dental dam?”Melanie Cristol said she came up with the idea for the panties after discovering on her 2014 honeymoon that she had an infection that could be sexually transmitted.

“I wanted to feel sexy and confident and use something that was made with my body and actual sex in mind,” she told the Times.

The panties are made of material about as thin as a condom and form a seal on the thigh to keep fluids inside, she said.

Dr. Marrazzo said the panties are an advancement because there are few options for safe oral sex. She noted that some teenagers have their first sexual experience with oral sex and that the panties could reduce anxiety for people of all ages.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

.

The underwear, sold as Lorals for Protection, are single-use, vanilla-scented, natural latex panties that cover the genitals and anus and block the transfer of bodily fluids during oral sex, according to the company website. They sell in packages of four for $25.

The FDA didn’t run human clinical trials but granted authorization after the company gave it data about the product, The New York Times reported.

“The FDA’s authorization of this product gives people another option to protect against STIs during oral sex,” said Courtney Lias, PhD, director of the FDA office that led the review of the underwear.

Previously, the FDA authorized oral dams to prevent the spread of STIs during oral sex. Oral dams, sometimes called oral sex condoms, are thin latex barriers that go between one partner’s mouth and the other person’s genitals. The dams haven’t been widely used, partly because a person has to hold the dam in place during sex, unlike the panties.

“They’re extremely unpopular,” Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told the Times. “I mean, honestly, could there be anything less sexy than a dental dam?”Melanie Cristol said she came up with the idea for the panties after discovering on her 2014 honeymoon that she had an infection that could be sexually transmitted.

“I wanted to feel sexy and confident and use something that was made with my body and actual sex in mind,” she told the Times.

The panties are made of material about as thin as a condom and form a seal on the thigh to keep fluids inside, she said.

Dr. Marrazzo said the panties are an advancement because there are few options for safe oral sex. She noted that some teenagers have their first sexual experience with oral sex and that the panties could reduce anxiety for people of all ages.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Nurses under fire: The stress of medical malpractice

Just because nurses are sued less often than doctors doesn’t mean that their actions aren’t a focus of a large number of medical malpractice lawsuits. A condition known as medical malpractice stress syndrome (MMSS) is increasingly being recognized as affecting medical professionals who are subjected to litigation.

According to a 2019 report by CRICO, the risk management arm of Harvard’s medical facilities, nursing was a “primary service” in 34% of cases with a high-severity injury and in 44% of cases that were closed with a payment. And even though nurses were named as defendants only 14% of the time, likely because many nurses don’t have their own personal malpractice coverage, their hospitals or facilities were sued in most of these cases – making the nurses important witnesses for the defense.

We have every reason to believe that things have gotten worse since the CRICO study was published. Chronic nursing shortages were exacerbated during the COVID pandemic, and we have seen a large number of nurses leave the workforce altogether. In a recent survey of nurses by Hospital IQ, 90% of respondents said they were considering leaving the nursing profession in the next year, with 71% of nurses who have more than 15 years of nursing experience thinking about leaving within the next few months.

Those remaining are faced with increased workloads and extra shifts – often mandated – and working with too little sleep. Their commitment to their mission is heroic, but they are only human; it’s hard to imagine the number of errors, the number of bad outcomes, and the number of lawsuits going anywhere but up.

And of course, the entire profession has been fixated on the recent case of the Tennessee nurse who was prosecuted criminally and convicted in connection with a fatal medication error.

These are all reasons to expect that an increasing number of nurses are going to be trying to cope with symptoms of MMSS. Too many of them will initially be viewed by lawyers or claims professionals as simply defensive, arrogant, or difficult to work with. In fact, it’s impossible to know how many cases are settled just to avoid the risk of such a “difficult client” being deposed.

These caring, hard-working, and committed individuals have had their lives shaken in ways that they never expected. Nurses with MMSS need support, but traditional psychotherapy, with a diffuse focus and long-time horizon, is not the most effective option. What’s necessary is practical support that is short term, goal oriented, and tailored to the specifics of the pending litigation process.

Most important, they need to know that they are not experiencing this alone, that MMSS is a common phenomenon, and that a productive coaching relationship can be highly effective.

When approached and supported effectively, nurses – and indeed all medical professionals – can regain their confidence and focus, continue having productive professional and personal lives, and reduce the likelihood of a downhill spiral. And it makes it more likely that they’ll remain in the profession rather than becoming just another statistic in the ever-worsening shortage of nurses in the United States.

Signs of MMSS in nurses

Mixed with their feelings of anxiety and depression, nurses with MMSS often have thoughts such as:

- Am I going to lose my license?

- Am I going to lose my job?

- Will my reputation be destroyed? Will I ever be able to work as a nurse again?

- What am I going to do for a living?

- If I lose everything, will my spouse divorce me? Will I lose my kids?

- I don’t think I did anything wrong, but what if I’m still found to be at fault?

- Did I miss something? Did I make a mistake? Was there something more that I should have done?

- What’s going to happen next? What else could go wrong?

- Are there more people out there who are going to sue me?

- Everything feels overwhelming and out of control.

- My entire identity is now in question.

- How do I get this case out of my head? I can’t focus on anything else.

- I’m developing medical problems of my own.

- I’m having difficulty focusing at work and relating to patients; how do I know who’s going to sue me next?

- I wish that I could escape it all; I feel like killing myself.

Gail Fiore is president of The Winning Focus, which works with physicians and other professionals involved in litigation who are having difficulty coping with stress, anxiety, and other emotional issues. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Just because nurses are sued less often than doctors doesn’t mean that their actions aren’t a focus of a large number of medical malpractice lawsuits. A condition known as medical malpractice stress syndrome (MMSS) is increasingly being recognized as affecting medical professionals who are subjected to litigation.

According to a 2019 report by CRICO, the risk management arm of Harvard’s medical facilities, nursing was a “primary service” in 34% of cases with a high-severity injury and in 44% of cases that were closed with a payment. And even though nurses were named as defendants only 14% of the time, likely because many nurses don’t have their own personal malpractice coverage, their hospitals or facilities were sued in most of these cases – making the nurses important witnesses for the defense.

We have every reason to believe that things have gotten worse since the CRICO study was published. Chronic nursing shortages were exacerbated during the COVID pandemic, and we have seen a large number of nurses leave the workforce altogether. In a recent survey of nurses by Hospital IQ, 90% of respondents said they were considering leaving the nursing profession in the next year, with 71% of nurses who have more than 15 years of nursing experience thinking about leaving within the next few months.

Those remaining are faced with increased workloads and extra shifts – often mandated – and working with too little sleep. Their commitment to their mission is heroic, but they are only human; it’s hard to imagine the number of errors, the number of bad outcomes, and the number of lawsuits going anywhere but up.

And of course, the entire profession has been fixated on the recent case of the Tennessee nurse who was prosecuted criminally and convicted in connection with a fatal medication error.

These are all reasons to expect that an increasing number of nurses are going to be trying to cope with symptoms of MMSS. Too many of them will initially be viewed by lawyers or claims professionals as simply defensive, arrogant, or difficult to work with. In fact, it’s impossible to know how many cases are settled just to avoid the risk of such a “difficult client” being deposed.

These caring, hard-working, and committed individuals have had their lives shaken in ways that they never expected. Nurses with MMSS need support, but traditional psychotherapy, with a diffuse focus and long-time horizon, is not the most effective option. What’s necessary is practical support that is short term, goal oriented, and tailored to the specifics of the pending litigation process.

Most important, they need to know that they are not experiencing this alone, that MMSS is a common phenomenon, and that a productive coaching relationship can be highly effective.

When approached and supported effectively, nurses – and indeed all medical professionals – can regain their confidence and focus, continue having productive professional and personal lives, and reduce the likelihood of a downhill spiral. And it makes it more likely that they’ll remain in the profession rather than becoming just another statistic in the ever-worsening shortage of nurses in the United States.

Signs of MMSS in nurses

Mixed with their feelings of anxiety and depression, nurses with MMSS often have thoughts such as:

- Am I going to lose my license?

- Am I going to lose my job?

- Will my reputation be destroyed? Will I ever be able to work as a nurse again?

- What am I going to do for a living?

- If I lose everything, will my spouse divorce me? Will I lose my kids?

- I don’t think I did anything wrong, but what if I’m still found to be at fault?

- Did I miss something? Did I make a mistake? Was there something more that I should have done?

- What’s going to happen next? What else could go wrong?

- Are there more people out there who are going to sue me?

- Everything feels overwhelming and out of control.

- My entire identity is now in question.

- How do I get this case out of my head? I can’t focus on anything else.

- I’m developing medical problems of my own.

- I’m having difficulty focusing at work and relating to patients; how do I know who’s going to sue me next?

- I wish that I could escape it all; I feel like killing myself.

Gail Fiore is president of The Winning Focus, which works with physicians and other professionals involved in litigation who are having difficulty coping with stress, anxiety, and other emotional issues. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Just because nurses are sued less often than doctors doesn’t mean that their actions aren’t a focus of a large number of medical malpractice lawsuits. A condition known as medical malpractice stress syndrome (MMSS) is increasingly being recognized as affecting medical professionals who are subjected to litigation.

According to a 2019 report by CRICO, the risk management arm of Harvard’s medical facilities, nursing was a “primary service” in 34% of cases with a high-severity injury and in 44% of cases that were closed with a payment. And even though nurses were named as defendants only 14% of the time, likely because many nurses don’t have their own personal malpractice coverage, their hospitals or facilities were sued in most of these cases – making the nurses important witnesses for the defense.

We have every reason to believe that things have gotten worse since the CRICO study was published. Chronic nursing shortages were exacerbated during the COVID pandemic, and we have seen a large number of nurses leave the workforce altogether. In a recent survey of nurses by Hospital IQ, 90% of respondents said they were considering leaving the nursing profession in the next year, with 71% of nurses who have more than 15 years of nursing experience thinking about leaving within the next few months.

Those remaining are faced with increased workloads and extra shifts – often mandated – and working with too little sleep. Their commitment to their mission is heroic, but they are only human; it’s hard to imagine the number of errors, the number of bad outcomes, and the number of lawsuits going anywhere but up.

And of course, the entire profession has been fixated on the recent case of the Tennessee nurse who was prosecuted criminally and convicted in connection with a fatal medication error.

These are all reasons to expect that an increasing number of nurses are going to be trying to cope with symptoms of MMSS. Too many of them will initially be viewed by lawyers or claims professionals as simply defensive, arrogant, or difficult to work with. In fact, it’s impossible to know how many cases are settled just to avoid the risk of such a “difficult client” being deposed.

These caring, hard-working, and committed individuals have had their lives shaken in ways that they never expected. Nurses with MMSS need support, but traditional psychotherapy, with a diffuse focus and long-time horizon, is not the most effective option. What’s necessary is practical support that is short term, goal oriented, and tailored to the specifics of the pending litigation process.

Most important, they need to know that they are not experiencing this alone, that MMSS is a common phenomenon, and that a productive coaching relationship can be highly effective.

When approached and supported effectively, nurses – and indeed all medical professionals – can regain their confidence and focus, continue having productive professional and personal lives, and reduce the likelihood of a downhill spiral. And it makes it more likely that they’ll remain in the profession rather than becoming just another statistic in the ever-worsening shortage of nurses in the United States.

Signs of MMSS in nurses

Mixed with their feelings of anxiety and depression, nurses with MMSS often have thoughts such as:

- Am I going to lose my license?

- Am I going to lose my job?

- Will my reputation be destroyed? Will I ever be able to work as a nurse again?

- What am I going to do for a living?

- If I lose everything, will my spouse divorce me? Will I lose my kids?

- I don’t think I did anything wrong, but what if I’m still found to be at fault?

- Did I miss something? Did I make a mistake? Was there something more that I should have done?

- What’s going to happen next? What else could go wrong?

- Are there more people out there who are going to sue me?

- Everything feels overwhelming and out of control.

- My entire identity is now in question.

- How do I get this case out of my head? I can’t focus on anything else.

- I’m developing medical problems of my own.

- I’m having difficulty focusing at work and relating to patients; how do I know who’s going to sue me next?

- I wish that I could escape it all; I feel like killing myself.

Gail Fiore is president of The Winning Focus, which works with physicians and other professionals involved in litigation who are having difficulty coping with stress, anxiety, and other emotional issues. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low butyrylcholinesterase: A possible biomarker of SIDS risk?

Reduced levels of the cholinergic-system enzyme butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) may provide another piece of the puzzle for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), preliminary data from Australian researchers suggested.

A small case-control study led by Carmel T. Harrington, PhD,* a sleep medicine expert and honorary research fellow at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead (Australia), found that measurements in 722 dried blood spots taken during neonatal screening 2 or 3 days after birth were lower in babies who subsequently died of SIDS, compared with those of matched surviving controls and other babies who died of non-SIDS causes.

In groups in which cases were reported as SIDS death (n = 26) there was strong evidence that lower BChE-specific activity was associated with death (odds ratio, 0.73 per U/mg; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.89, P = .0014). In groups with a non-SIDS death (n = 41), there was no evidence of a linear association between BChE activity and death (OR, 1.001 per U/mg; 95% CI, 0.89-1.13, P = .99). A cohort of 655 age- and sex-matched controls served as a reference group.

Writing online in eBioMedicine, the researchers concluded that a previously unidentified cholinergic deficit, identifiable by abnormal BChE-specific activity, is present at birth in SIDS babies and represents a measurable, specific vulnerability prior to their death. “The finding presents the possibility of identifying infants at future risk for SIDS and it provides a specific avenue for future research into interventions prior to death.”

They hypothesized that the association is evidence of an altered cholinergic homeostasis and claim theirs is the first study to identify a measurable biochemical marker in babies who succumbed to SIDS. The marker “could plausibly produce functional alterations to an infant’s autonomic and arousal responses to an exogenous stressor leaving them vulnerable to sudden death.”

Commenting in a press release, Dr. Harrington said that “babies have a very powerful mechanism to let us know when they are not happy. Usually, if a baby is confronted with a life-threatening situation, such as difficulty breathing during sleep because they are on their tummies, they will arouse and cry out. What this research shows is that some babies don’t have this same robust arousal response.” Despite the sparse data, she believes that BChE is likely involved.

Providing a U.S. perspective on the study but not involved in it, Fern R. Hauck, MD, MS, a professor of family medicine and public health at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said that “the media coverage presenting this as the ‘cause of SIDS,’ for which we may find a cure within 5 years, is very disturbing and very misleading. The data are very preliminary and results are based on only 26 SIDS cases.” In addition, the blood samples were more than 2 years old.

This research needs to be repeated in other labs in larger and diverse SIDS populations, she added. “Furthermore, we are not provided any racial-ethnic information about the SIDS cases in this study. In the U.S., the infants who are at greatest risk of dying from SIDS are most commonly African American and Native American/Alaska Native, and thus, these studies would need to be repeated in U.S. populations.”

Dr. Hauck added that, while the differences in blood levels of this enzyme were statistically different, even if this is confirmed by larger studies, there was enough overlap in the blood levels between cases and controls that it could not be used as a blood test at this point with any reasonable predictive value.

As the authors pointed out, she said, the leading theory of SIDS causation is that multiple factors interact. “While everyone would be happy to find one single explanation, it is not so simple. This research does, however, bring into focus the issues of arousal in SIDS and work on biomarkers. The arousal issue is one researchers have been working on for a long time.”

The SIDS research community has long been interested in biomarkers, Dr. Hauck continued. “Dr. Hannah Kinney’s first autoradiography study reported decreased muscarinic cholinergic receptor binding in the arcuate nucleus in SIDS, which the butyrylcholinesterase work further elaborates. More recently, Dr. Kinney reported abnormal cholinergic binding in the mesopontine reticular formation that is related to arousal and REM.”

Moreover, Robin Haynes and colleagues reported in 2017 that differences in serotonin can similarly be found in newborns on a newborn blood test, she said. “Like the butyrylcholinesterase research, there is a lot of work to do before understanding how specifically it can identify risk. The problem with using it prematurely is that it will unnecessarily alarm parents that their baby will die, and, to make it worse, be inaccurate in our warning.”

She also expressed concern that with the focus on a biomarker, parents will forget that SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths have come down considerably in the United States thanks to greater emphasis on promoting safe infant sleep behaviors.

The research was supported by a crowdfunding campaign and by NSW Health Pathology. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Hauck disclosed no conflicts of interest.

* This story was corrected on 5/20/2022.

Reduced levels of the cholinergic-system enzyme butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) may provide another piece of the puzzle for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), preliminary data from Australian researchers suggested.

A small case-control study led by Carmel T. Harrington, PhD,* a sleep medicine expert and honorary research fellow at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead (Australia), found that measurements in 722 dried blood spots taken during neonatal screening 2 or 3 days after birth were lower in babies who subsequently died of SIDS, compared with those of matched surviving controls and other babies who died of non-SIDS causes.

In groups in which cases were reported as SIDS death (n = 26) there was strong evidence that lower BChE-specific activity was associated with death (odds ratio, 0.73 per U/mg; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.89, P = .0014). In groups with a non-SIDS death (n = 41), there was no evidence of a linear association between BChE activity and death (OR, 1.001 per U/mg; 95% CI, 0.89-1.13, P = .99). A cohort of 655 age- and sex-matched controls served as a reference group.

Writing online in eBioMedicine, the researchers concluded that a previously unidentified cholinergic deficit, identifiable by abnormal BChE-specific activity, is present at birth in SIDS babies and represents a measurable, specific vulnerability prior to their death. “The finding presents the possibility of identifying infants at future risk for SIDS and it provides a specific avenue for future research into interventions prior to death.”

They hypothesized that the association is evidence of an altered cholinergic homeostasis and claim theirs is the first study to identify a measurable biochemical marker in babies who succumbed to SIDS. The marker “could plausibly produce functional alterations to an infant’s autonomic and arousal responses to an exogenous stressor leaving them vulnerable to sudden death.”

Commenting in a press release, Dr. Harrington said that “babies have a very powerful mechanism to let us know when they are not happy. Usually, if a baby is confronted with a life-threatening situation, such as difficulty breathing during sleep because they are on their tummies, they will arouse and cry out. What this research shows is that some babies don’t have this same robust arousal response.” Despite the sparse data, she believes that BChE is likely involved.

Providing a U.S. perspective on the study but not involved in it, Fern R. Hauck, MD, MS, a professor of family medicine and public health at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said that “the media coverage presenting this as the ‘cause of SIDS,’ for which we may find a cure within 5 years, is very disturbing and very misleading. The data are very preliminary and results are based on only 26 SIDS cases.” In addition, the blood samples were more than 2 years old.

This research needs to be repeated in other labs in larger and diverse SIDS populations, she added. “Furthermore, we are not provided any racial-ethnic information about the SIDS cases in this study. In the U.S., the infants who are at greatest risk of dying from SIDS are most commonly African American and Native American/Alaska Native, and thus, these studies would need to be repeated in U.S. populations.”

Dr. Hauck added that, while the differences in blood levels of this enzyme were statistically different, even if this is confirmed by larger studies, there was enough overlap in the blood levels between cases and controls that it could not be used as a blood test at this point with any reasonable predictive value.

As the authors pointed out, she said, the leading theory of SIDS causation is that multiple factors interact. “While everyone would be happy to find one single explanation, it is not so simple. This research does, however, bring into focus the issues of arousal in SIDS and work on biomarkers. The arousal issue is one researchers have been working on for a long time.”

The SIDS research community has long been interested in biomarkers, Dr. Hauck continued. “Dr. Hannah Kinney’s first autoradiography study reported decreased muscarinic cholinergic receptor binding in the arcuate nucleus in SIDS, which the butyrylcholinesterase work further elaborates. More recently, Dr. Kinney reported abnormal cholinergic binding in the mesopontine reticular formation that is related to arousal and REM.”

Moreover, Robin Haynes and colleagues reported in 2017 that differences in serotonin can similarly be found in newborns on a newborn blood test, she said. “Like the butyrylcholinesterase research, there is a lot of work to do before understanding how specifically it can identify risk. The problem with using it prematurely is that it will unnecessarily alarm parents that their baby will die, and, to make it worse, be inaccurate in our warning.”

She also expressed concern that with the focus on a biomarker, parents will forget that SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths have come down considerably in the United States thanks to greater emphasis on promoting safe infant sleep behaviors.

The research was supported by a crowdfunding campaign and by NSW Health Pathology. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Hauck disclosed no conflicts of interest.

* This story was corrected on 5/20/2022.

Reduced levels of the cholinergic-system enzyme butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) may provide another piece of the puzzle for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), preliminary data from Australian researchers suggested.

A small case-control study led by Carmel T. Harrington, PhD,* a sleep medicine expert and honorary research fellow at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead (Australia), found that measurements in 722 dried blood spots taken during neonatal screening 2 or 3 days after birth were lower in babies who subsequently died of SIDS, compared with those of matched surviving controls and other babies who died of non-SIDS causes.

In groups in which cases were reported as SIDS death (n = 26) there was strong evidence that lower BChE-specific activity was associated with death (odds ratio, 0.73 per U/mg; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.89, P = .0014). In groups with a non-SIDS death (n = 41), there was no evidence of a linear association between BChE activity and death (OR, 1.001 per U/mg; 95% CI, 0.89-1.13, P = .99). A cohort of 655 age- and sex-matched controls served as a reference group.

Writing online in eBioMedicine, the researchers concluded that a previously unidentified cholinergic deficit, identifiable by abnormal BChE-specific activity, is present at birth in SIDS babies and represents a measurable, specific vulnerability prior to their death. “The finding presents the possibility of identifying infants at future risk for SIDS and it provides a specific avenue for future research into interventions prior to death.”

They hypothesized that the association is evidence of an altered cholinergic homeostasis and claim theirs is the first study to identify a measurable biochemical marker in babies who succumbed to SIDS. The marker “could plausibly produce functional alterations to an infant’s autonomic and arousal responses to an exogenous stressor leaving them vulnerable to sudden death.”

Commenting in a press release, Dr. Harrington said that “babies have a very powerful mechanism to let us know when they are not happy. Usually, if a baby is confronted with a life-threatening situation, such as difficulty breathing during sleep because they are on their tummies, they will arouse and cry out. What this research shows is that some babies don’t have this same robust arousal response.” Despite the sparse data, she believes that BChE is likely involved.

Providing a U.S. perspective on the study but not involved in it, Fern R. Hauck, MD, MS, a professor of family medicine and public health at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said that “the media coverage presenting this as the ‘cause of SIDS,’ for which we may find a cure within 5 years, is very disturbing and very misleading. The data are very preliminary and results are based on only 26 SIDS cases.” In addition, the blood samples were more than 2 years old.