User login

News and Views that Matter to Pediatricians

The leading independent newspaper covering news and commentary in pediatrics.

How heat kills: Deadly weather ‘cooking’ people from within

Millions of Americans have been languishing for weeks in the oppressive heat and humidity of a merciless summer. Deadly heat has already taken the lives of hundreds in the Pacific Northwest alone, with numbers likely to grow as the full impact of heat-related deaths eventually comes to light.

In the final week of July, the National Weather Service issued excessive heat warnings for 17 states, stretching from the West Coast, across the Midwest, down south into Louisiana and Georgia. Temperatures 10° to 15° F above average threaten the lives and livelihoods of people all across the country.

After a scorching heat wave in late June, residents of the Pacific Northwest are once again likely to see triple-digit temperatures in the coming days. With the heat, hospitals may face another surge of people with heat-related illnesses.

Erika Moseson, MD, a lung and intensive care specialist, witnessed firsthand the life-threatening impacts of soaring temperatures. She happened to be running her 10-bed intensive care unit in a suburban hospital in Gresham, Ore., about 15 miles east of Portland, the weekend of June 26. Within 12 hours, almost half her ICU beds were filled with people found unconscious on the street, in the bushes, or in their own beds, all because their body’s defenses had become overwhelmed by heat.

“It was unidentified person after unidentified person, coming in, same story, temperatures through the roof, comatose,” Dr. Moseson recalled. Young people in their 20s with muscle breakdown markers through the roof, a sign of rhabdomyolysis; people with no other medical problems that would have put them in a high-risk category.

As a lifelong Oregonian, she’d never seen anything like this before. “We’re all trained for it. I know what happens to you if you have heatstroke, I know how to treat it,” she trailed off, still finding it hard to believe. Still reeling from the number of cases in just a few hours. Still shocked that this happened on what’s supposed to be the cooler, rainforest side of Oregon.

Among those she treated and resuscitated, the memory of a patient that she lost continues to gnaw at her.

“I’ve gone back to it day after day since it happened,” she reflected.

Adults, in their 50s, living at home with their children. Just 1 hour prior, they’d all said goodnight. Then 1 hour later, when a child came to check in, both parents were unconscious.

Dr. Moseson shared how her team tried everything in their power for 18 hours to save the parent that was brought to her ICU. But like hundreds of others who went through the heat wave that weekend, her patient didn’t survive.

It was too late. From Dr. Moseson’s experience, it’s what happens “if you’re cooking a human.”

How heat kills

Regardless of where we live on the planet, humans maintain a consistent internal temperature around 98° F for our systems to function properly.

Our bodies have an entire temperature-regulating system to balance heat gain with heat loss so we don’t stray too far from our ideal range. The hypothalamus functions as the thermostat, communicating with heat sensors in our skin, muscles, and spinal cord. Based on signals about our core body temperature, our nervous system makes many decisions for us – opening up blood vessels in the peripheral parts of our body, pushing more blood toward the skin, and activating sweat glands to produce more sweat.

Sweat is one of the most powerful tools we have to maintain a safe internal temperature. Of course, there are some things under our control, such as removing clothing, drinking more water, and finding shade (or preferably air conditioning). But beyond that, it’s our ability to sweat that keeps us cool. When sweat evaporates into the air, heat from our skin goes with it, cooling us off.

Over time, our sweat response can work better as we get used to warmer environments, a process that’s known as acclimatization. Over the period of a few days to weeks, the sweat glands of acclimated people can start making sweat at lower temperatures, produce more sweat, and absorb more salt back into our system, all to make us more efficient “sweaters.”

While someone who’s not used to the heat may only produce 1 liter of sweat per hour, people who have become acclimated can produce 2-3 liters every hour, allowing evaporation to eliminate more than two times the amount of heat.

Because the process of acclimatization can take some time, typically it’s the first throes of summer, or heat waves in places where people don’t typically see high temperatures, that are the most deadly. And of course, the right infrastructure, like access to air conditioning, also plays a large role in limiting heat-related death and hospitalization.

A 2019 study showed that heat-related hospitalizations peak at different temperatures in different places. For example, hospitalizations typically peak in Texas when the temperature hits 105° F. But they might be highest in the Pacific Northwest at just 81° F.

Even with acclimatization, there are limits to how much our bodies can adapt to heat. When the humidity goes up past 75%, there’s already so much moisture in the air that heat loss through evaporation no longer occurs.

It’s this connection between heat and humidity that can be deadly. This is why the heat index (a measure that takes into account temperature and relative humidity) and wet bulb globe temperature (a measure commonly used by the military and competitive athletes that takes into account temperature, humidity, wind speed, sun angle, and cloud cover) are both better at showing how dangerous the heat may be for our health, compared to temperature alone.

Kristie L. Ebi, PhD, a professor in the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the University of Washington, Seattle, has been studying the effects of heat and other climate-sensitive conditions on health for over 20 years. She stresses that it’s not just the recorded temperatures, but the prolonged exposure that kills.

If you never get a chance to bring down that core body temperature, if your internal temperatures stay above the range where your cells and your organs can work well for a long time, that’s when you can have the most dangerous effects of heat.

“It depends then on your age, your fitness, your individual physiology, underlying medical conditions, to how quickly that could affect the functioning of those organs. There’s lots of variability in there,” Dr. Ebi said.

Our hearts take on the brunt of the early response, working harder to pump blood toward the skin. Water and salt loss through our skin can start to cause electrolyte changes that can cause heat cramps and heat exhaustion. We feel tired, nauseated, dizzy. With enough water loss, we may become dehydrated, limiting the blood flow to our brains, causing us to pass out.

These early signs are like a car’s check engine light – systems are already being damaged, but resting, refueling, and, most importantly, turning off the heat are critical steps to prevent fatal injury.

If hazardous heat exposure continues and our internal temperatures continue to rise, nerves stop talking to each other, the proteins in our body unfold and lose their shape, and the cells of our organs disintegrate. This in turn sets off a fire alarm in our blood vessels, where a variety of chemical messengers, including “heat-shock proteins,” are released. The release of these inflammatory proteins, coupled with the loss of blood flow, eventually leads to the death of cells throughout the body, from the brain, to the heart, the muscles, and the kidneys.

This process is referred to as heatstroke. In essence, we melt from the inside.

At a certain point, this cascade can’t be reversed. Just like when you cool a melting block of ice, the parts that have melted will not go back to their original shape. It’s a similar process in our bodies, so delays in cooling and treatment can lead to death rates as high as 80%.

On the outside, we see people who look confused and disoriented, with hot skin and rapid breathing, and they may eventually become unconscious. Core body temperatures over 105° F clinch the diagnosis, but at the first sign of feeling unwell, cooling should be started.

There is no fancier or more effective treatment than that: Cool right away. In emergency rooms in Washington State, doctors used body bags filled with ice and water to cool victims of the heat wave in late June.

“It was all from heat ... that’s the thing, you feel so idiotic ... you’re like, ‘I’ve given you ice’ ... you bring their temperature down. But it’s already set off this cascade that you can’t stop,” Dr. Moseson said.

By the time Dr. Moseson’s patient made it to her, cooling with ice was just the beginning of the attempts to resuscitate and revive. The patient was already showing evidence of a process causing widespread bleeding and clotting, known as disseminated intravascular coagulation, along with damage to the heart and failing kidneys. Over 18 hours, her team cooled the patient, flooded the blood vessels with fluids and blood products, attempted to start dialysis, and inserted a breathing tube – all of the technology that is used to save people from serious cardiovascular collapse from other conditions. But nothing could reverse the melting that had already occurred.

Deaths from heat are 100% preventable. Until they’re not.

No respite

As Dr. Ebi says, the key to preventing heat-related death is to cool down enough to stabilize our internal cells and proteins before the irreversible cascade begins.

But for close to 80% of Americans who live in urban areas, temperatures can be even higher and more intolerable compared to surrounding areas because of the way we’ve designed our cities. In effect, we have unintentionally created hot zones called “urban heat islands.”

Jeremy Hoffman, PhD, chief scientist for the Science Museum of Virginia, explains that things like bricks, asphalt, and parking lots absorb more of the sun’s energy throughout the day and then emit that back into the air as heat throughout the afternoon and into the evening. This raises the air and surface temperatures in cities, relative to rural areas. When temperatures don’t cool enough at night, there’s no way to recover from the day’s heat. You start the next day still depleted, with less reserve to face the heat of a new day.

When you dig even deeper, it turns out that even within the same city, there are huge “thermal inequities,” as Dr. Hoffman calls them. In a 2019 study, he found that wealthier parts of cities had more natural spaces such as parks and tree-lined streets, compared to areas that had been intentionally “redlined,” or systematically deprived of investment. This pattern repeats itself in over 100 urban areas across the country and translates to huge temperature differences on the order of 10-20 degrees Fahrenheit within the same city, at the exact same time during a heat wave.

“In some ways, the way that we’ve decided to plan and build our cities physically turns up the thermostat by several tens of degrees during heat waves in particular neighborhoods,” Dr. Hoffman said.

Dr. Hoffman’s work showed that the city of Portland (where the death toll from the heat wave in late June was the highest) had some of the most intense differences between formerly redlined vs. tree-lined areas out of the more than 100 cities that he studied.

“Watching it play out, I was really concerned, not only as a climate scientist, but as a human. Understanding the urban heat island effect and the extreme nature of the inequity in our cities, thermally and otherwise, once you start to really recognize it, you can’t forget it.”

The most vulnerable

When it comes to identifying and protecting the people most vulnerable to heat stress and heat-related death, there is an ever-growing list of those most at risk. Unfortunately, very few recognize when they themselves are at risk, often until it’s too late.

According to Linda McCauley, PhD, dean of the Emory University School of Nursing in Atlanta, “the scope of who is vulnerable is quickly increasing.”

For example, we’re used to recognizing that pregnant women and young children are at risk. Public health campaigns have long advised us not to leave young children and pets in hot cars. We know that adolescents who play sports during hot summer months are at high risk for heat-related events and even death.

In Georgia, a 15-year-old boy collapsed and died after his first day back at football practice when the heat index was 105° F on July 26, even as it appears that all protocols for heat safety were being followed.

We recognize that outdoor workers face devastating consequences from prolonged exertion in the heat and must have safer working conditions.

The elderly and those with long-term medical and mental health conditions are also more vulnerable to heat. The elderly may not have the same warning signs and may not recognize that they are dehydrated until it is too late. In addition, their sweating mechanism weakens, and they may be taking medicines that interfere with their ability to regulate their temperature.

Poverty and inadequate housing are risk factors, especially for those in urban heat islands. For many people, their housing does not have enough cooling to protect them, and they can’t safely get themselves to cooling shelters.

These patterns for the most vulnerable fit for the majority of deaths in Oregon during the late June heat wave. Most victims were older, lived alone, and didn’t have air conditioning. But with climate change, the predictions are that temperatures will go higher and heat waves will last longer.

“There’s probably very few people today that are ‘immune’ to the effects of heat-related stress with climate change. All of us can be put in situations where we are susceptible,” Dr. McCauley said.

Dr. Moseson agreed. Many of her patients fit none of these risk categories – she treated people with no health problems in their 20s in her ICU, and the patient she lost would not traditionally have been thought of as high risk. That 50-something patient had no long-standing medical problems, and lived with family in a newly renovated suburban home that had air conditioning. The only problem was that the air conditioner had broken and there had been no rush to fix it based on past experience with Oregon summers.

Preventing heat deaths

Protecting ourselves and our families means monitoring the “simple things.” The first three rules are to make sure we’re drinking plenty of water – this means drinking whether we feel thirsty or not. If we’re not in an air-conditioned place, we’ve got to look for shade. And we need to take regular rest breaks.

Inside a home without air conditioning, placing ice in front of a fan to cool the air can work, but realistically, if you are in a place without air conditioning and the temperatures are approaching 90° F, it’s safest to find another place to stay, if possible.

For those playing sports, there are usually 1-week to 2-week protocols that allow for acclimatization when the season begins – this means starting slowly, without gear, and ramping up activity. Still, parents and coaches should watch advanced weather reports to make sure it’s safe to practice outside.

How we dress can also help us, so light clothing is key. And if we’re able to schedule activities for times when it is cooler, that can also protect us from overheating.

If anyone shows early signs of heat stress, removing clothing, cooling their bodies with cold water, and getting them out of the heat is critical. Any evidence of heatstroke is an emergency, and 911 should be called without delay. The faster the core temperature can be dropped, the better the chances for recovery.

On the level of communities, access to natural air conditioning in the form of healthy tree canopies, and trees at bus stops to provide shade can help a lot. According to Dr. Hoffman, these investments help almost right away. Reimagining our cities to remove the “hot zones” that we have created is another key to protecting ourselves as our climate changes.

Reaching our limits in a changing climate

Already, we are seeing more intense, more frequent, and longer-lasting heat waves throughout the country and across the globe.

Dr. Ebi, a coauthor of a recently released scientific analysis that found that the late June Pacific Northwest heat wave would have been virtually impossible without climate change, herself lived through the scorching temperatures in Seattle. Her work shows that the changing climate is killing us right now.

We are approaching a time where extreme temperatures and humidity will make it almost impossible for people to be outside in many parts of the world. Researchers have found that periods of extreme humid heat have more than doubled since 1979, and some places have already had wet-bulb temperatures at the limits of what scientists think humans can tolerate under ideal conditions, meaning for people in perfect health, completely unclothed, in gale-force winds, performing no activity. Obviously that’s less than ideal for most of us and helps explain why thousands of people die at temperatures much lower than our upper limit.

Dr. Ebi pointed out that the good news is that many local communities with a long history of managing high temperatures have a lot of knowledge to share with regions that are newly dealing with these conditions. This includes how local areas develop early warning and response systems with specific action plans.

But, she cautions, it’s going to take a lot of coordination and a lot of behavior change to stabilize the earth’s climate, understand our weak points, and protect our health.

For Dr. Moseson, this reality has hit home.

“I already spent the year being terrified that I as an ICU doctor was going to be the one who gave my mom COVID. Finally I’m vaccinated, she’s vaccinated. Now I’ve watched someone die because they don’t have AC. And my parents, they’re old-school Oregonians, they don’t have AC.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Millions of Americans have been languishing for weeks in the oppressive heat and humidity of a merciless summer. Deadly heat has already taken the lives of hundreds in the Pacific Northwest alone, with numbers likely to grow as the full impact of heat-related deaths eventually comes to light.

In the final week of July, the National Weather Service issued excessive heat warnings for 17 states, stretching from the West Coast, across the Midwest, down south into Louisiana and Georgia. Temperatures 10° to 15° F above average threaten the lives and livelihoods of people all across the country.

After a scorching heat wave in late June, residents of the Pacific Northwest are once again likely to see triple-digit temperatures in the coming days. With the heat, hospitals may face another surge of people with heat-related illnesses.

Erika Moseson, MD, a lung and intensive care specialist, witnessed firsthand the life-threatening impacts of soaring temperatures. She happened to be running her 10-bed intensive care unit in a suburban hospital in Gresham, Ore., about 15 miles east of Portland, the weekend of June 26. Within 12 hours, almost half her ICU beds were filled with people found unconscious on the street, in the bushes, or in their own beds, all because their body’s defenses had become overwhelmed by heat.

“It was unidentified person after unidentified person, coming in, same story, temperatures through the roof, comatose,” Dr. Moseson recalled. Young people in their 20s with muscle breakdown markers through the roof, a sign of rhabdomyolysis; people with no other medical problems that would have put them in a high-risk category.

As a lifelong Oregonian, she’d never seen anything like this before. “We’re all trained for it. I know what happens to you if you have heatstroke, I know how to treat it,” she trailed off, still finding it hard to believe. Still reeling from the number of cases in just a few hours. Still shocked that this happened on what’s supposed to be the cooler, rainforest side of Oregon.

Among those she treated and resuscitated, the memory of a patient that she lost continues to gnaw at her.

“I’ve gone back to it day after day since it happened,” she reflected.

Adults, in their 50s, living at home with their children. Just 1 hour prior, they’d all said goodnight. Then 1 hour later, when a child came to check in, both parents were unconscious.

Dr. Moseson shared how her team tried everything in their power for 18 hours to save the parent that was brought to her ICU. But like hundreds of others who went through the heat wave that weekend, her patient didn’t survive.

It was too late. From Dr. Moseson’s experience, it’s what happens “if you’re cooking a human.”

How heat kills

Regardless of where we live on the planet, humans maintain a consistent internal temperature around 98° F for our systems to function properly.

Our bodies have an entire temperature-regulating system to balance heat gain with heat loss so we don’t stray too far from our ideal range. The hypothalamus functions as the thermostat, communicating with heat sensors in our skin, muscles, and spinal cord. Based on signals about our core body temperature, our nervous system makes many decisions for us – opening up blood vessels in the peripheral parts of our body, pushing more blood toward the skin, and activating sweat glands to produce more sweat.

Sweat is one of the most powerful tools we have to maintain a safe internal temperature. Of course, there are some things under our control, such as removing clothing, drinking more water, and finding shade (or preferably air conditioning). But beyond that, it’s our ability to sweat that keeps us cool. When sweat evaporates into the air, heat from our skin goes with it, cooling us off.

Over time, our sweat response can work better as we get used to warmer environments, a process that’s known as acclimatization. Over the period of a few days to weeks, the sweat glands of acclimated people can start making sweat at lower temperatures, produce more sweat, and absorb more salt back into our system, all to make us more efficient “sweaters.”

While someone who’s not used to the heat may only produce 1 liter of sweat per hour, people who have become acclimated can produce 2-3 liters every hour, allowing evaporation to eliminate more than two times the amount of heat.

Because the process of acclimatization can take some time, typically it’s the first throes of summer, or heat waves in places where people don’t typically see high temperatures, that are the most deadly. And of course, the right infrastructure, like access to air conditioning, also plays a large role in limiting heat-related death and hospitalization.

A 2019 study showed that heat-related hospitalizations peak at different temperatures in different places. For example, hospitalizations typically peak in Texas when the temperature hits 105° F. But they might be highest in the Pacific Northwest at just 81° F.

Even with acclimatization, there are limits to how much our bodies can adapt to heat. When the humidity goes up past 75%, there’s already so much moisture in the air that heat loss through evaporation no longer occurs.

It’s this connection between heat and humidity that can be deadly. This is why the heat index (a measure that takes into account temperature and relative humidity) and wet bulb globe temperature (a measure commonly used by the military and competitive athletes that takes into account temperature, humidity, wind speed, sun angle, and cloud cover) are both better at showing how dangerous the heat may be for our health, compared to temperature alone.

Kristie L. Ebi, PhD, a professor in the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the University of Washington, Seattle, has been studying the effects of heat and other climate-sensitive conditions on health for over 20 years. She stresses that it’s not just the recorded temperatures, but the prolonged exposure that kills.

If you never get a chance to bring down that core body temperature, if your internal temperatures stay above the range where your cells and your organs can work well for a long time, that’s when you can have the most dangerous effects of heat.

“It depends then on your age, your fitness, your individual physiology, underlying medical conditions, to how quickly that could affect the functioning of those organs. There’s lots of variability in there,” Dr. Ebi said.

Our hearts take on the brunt of the early response, working harder to pump blood toward the skin. Water and salt loss through our skin can start to cause electrolyte changes that can cause heat cramps and heat exhaustion. We feel tired, nauseated, dizzy. With enough water loss, we may become dehydrated, limiting the blood flow to our brains, causing us to pass out.

These early signs are like a car’s check engine light – systems are already being damaged, but resting, refueling, and, most importantly, turning off the heat are critical steps to prevent fatal injury.

If hazardous heat exposure continues and our internal temperatures continue to rise, nerves stop talking to each other, the proteins in our body unfold and lose their shape, and the cells of our organs disintegrate. This in turn sets off a fire alarm in our blood vessels, where a variety of chemical messengers, including “heat-shock proteins,” are released. The release of these inflammatory proteins, coupled with the loss of blood flow, eventually leads to the death of cells throughout the body, from the brain, to the heart, the muscles, and the kidneys.

This process is referred to as heatstroke. In essence, we melt from the inside.

At a certain point, this cascade can’t be reversed. Just like when you cool a melting block of ice, the parts that have melted will not go back to their original shape. It’s a similar process in our bodies, so delays in cooling and treatment can lead to death rates as high as 80%.

On the outside, we see people who look confused and disoriented, with hot skin and rapid breathing, and they may eventually become unconscious. Core body temperatures over 105° F clinch the diagnosis, but at the first sign of feeling unwell, cooling should be started.

There is no fancier or more effective treatment than that: Cool right away. In emergency rooms in Washington State, doctors used body bags filled with ice and water to cool victims of the heat wave in late June.

“It was all from heat ... that’s the thing, you feel so idiotic ... you’re like, ‘I’ve given you ice’ ... you bring their temperature down. But it’s already set off this cascade that you can’t stop,” Dr. Moseson said.

By the time Dr. Moseson’s patient made it to her, cooling with ice was just the beginning of the attempts to resuscitate and revive. The patient was already showing evidence of a process causing widespread bleeding and clotting, known as disseminated intravascular coagulation, along with damage to the heart and failing kidneys. Over 18 hours, her team cooled the patient, flooded the blood vessels with fluids and blood products, attempted to start dialysis, and inserted a breathing tube – all of the technology that is used to save people from serious cardiovascular collapse from other conditions. But nothing could reverse the melting that had already occurred.

Deaths from heat are 100% preventable. Until they’re not.

No respite

As Dr. Ebi says, the key to preventing heat-related death is to cool down enough to stabilize our internal cells and proteins before the irreversible cascade begins.

But for close to 80% of Americans who live in urban areas, temperatures can be even higher and more intolerable compared to surrounding areas because of the way we’ve designed our cities. In effect, we have unintentionally created hot zones called “urban heat islands.”

Jeremy Hoffman, PhD, chief scientist for the Science Museum of Virginia, explains that things like bricks, asphalt, and parking lots absorb more of the sun’s energy throughout the day and then emit that back into the air as heat throughout the afternoon and into the evening. This raises the air and surface temperatures in cities, relative to rural areas. When temperatures don’t cool enough at night, there’s no way to recover from the day’s heat. You start the next day still depleted, with less reserve to face the heat of a new day.

When you dig even deeper, it turns out that even within the same city, there are huge “thermal inequities,” as Dr. Hoffman calls them. In a 2019 study, he found that wealthier parts of cities had more natural spaces such as parks and tree-lined streets, compared to areas that had been intentionally “redlined,” or systematically deprived of investment. This pattern repeats itself in over 100 urban areas across the country and translates to huge temperature differences on the order of 10-20 degrees Fahrenheit within the same city, at the exact same time during a heat wave.

“In some ways, the way that we’ve decided to plan and build our cities physically turns up the thermostat by several tens of degrees during heat waves in particular neighborhoods,” Dr. Hoffman said.

Dr. Hoffman’s work showed that the city of Portland (where the death toll from the heat wave in late June was the highest) had some of the most intense differences between formerly redlined vs. tree-lined areas out of the more than 100 cities that he studied.

“Watching it play out, I was really concerned, not only as a climate scientist, but as a human. Understanding the urban heat island effect and the extreme nature of the inequity in our cities, thermally and otherwise, once you start to really recognize it, you can’t forget it.”

The most vulnerable

When it comes to identifying and protecting the people most vulnerable to heat stress and heat-related death, there is an ever-growing list of those most at risk. Unfortunately, very few recognize when they themselves are at risk, often until it’s too late.

According to Linda McCauley, PhD, dean of the Emory University School of Nursing in Atlanta, “the scope of who is vulnerable is quickly increasing.”

For example, we’re used to recognizing that pregnant women and young children are at risk. Public health campaigns have long advised us not to leave young children and pets in hot cars. We know that adolescents who play sports during hot summer months are at high risk for heat-related events and even death.

In Georgia, a 15-year-old boy collapsed and died after his first day back at football practice when the heat index was 105° F on July 26, even as it appears that all protocols for heat safety were being followed.

We recognize that outdoor workers face devastating consequences from prolonged exertion in the heat and must have safer working conditions.

The elderly and those with long-term medical and mental health conditions are also more vulnerable to heat. The elderly may not have the same warning signs and may not recognize that they are dehydrated until it is too late. In addition, their sweating mechanism weakens, and they may be taking medicines that interfere with their ability to regulate their temperature.

Poverty and inadequate housing are risk factors, especially for those in urban heat islands. For many people, their housing does not have enough cooling to protect them, and they can’t safely get themselves to cooling shelters.

These patterns for the most vulnerable fit for the majority of deaths in Oregon during the late June heat wave. Most victims were older, lived alone, and didn’t have air conditioning. But with climate change, the predictions are that temperatures will go higher and heat waves will last longer.

“There’s probably very few people today that are ‘immune’ to the effects of heat-related stress with climate change. All of us can be put in situations where we are susceptible,” Dr. McCauley said.

Dr. Moseson agreed. Many of her patients fit none of these risk categories – she treated people with no health problems in their 20s in her ICU, and the patient she lost would not traditionally have been thought of as high risk. That 50-something patient had no long-standing medical problems, and lived with family in a newly renovated suburban home that had air conditioning. The only problem was that the air conditioner had broken and there had been no rush to fix it based on past experience with Oregon summers.

Preventing heat deaths

Protecting ourselves and our families means monitoring the “simple things.” The first three rules are to make sure we’re drinking plenty of water – this means drinking whether we feel thirsty or not. If we’re not in an air-conditioned place, we’ve got to look for shade. And we need to take regular rest breaks.

Inside a home without air conditioning, placing ice in front of a fan to cool the air can work, but realistically, if you are in a place without air conditioning and the temperatures are approaching 90° F, it’s safest to find another place to stay, if possible.

For those playing sports, there are usually 1-week to 2-week protocols that allow for acclimatization when the season begins – this means starting slowly, without gear, and ramping up activity. Still, parents and coaches should watch advanced weather reports to make sure it’s safe to practice outside.

How we dress can also help us, so light clothing is key. And if we’re able to schedule activities for times when it is cooler, that can also protect us from overheating.

If anyone shows early signs of heat stress, removing clothing, cooling their bodies with cold water, and getting them out of the heat is critical. Any evidence of heatstroke is an emergency, and 911 should be called without delay. The faster the core temperature can be dropped, the better the chances for recovery.

On the level of communities, access to natural air conditioning in the form of healthy tree canopies, and trees at bus stops to provide shade can help a lot. According to Dr. Hoffman, these investments help almost right away. Reimagining our cities to remove the “hot zones” that we have created is another key to protecting ourselves as our climate changes.

Reaching our limits in a changing climate

Already, we are seeing more intense, more frequent, and longer-lasting heat waves throughout the country and across the globe.

Dr. Ebi, a coauthor of a recently released scientific analysis that found that the late June Pacific Northwest heat wave would have been virtually impossible without climate change, herself lived through the scorching temperatures in Seattle. Her work shows that the changing climate is killing us right now.

We are approaching a time where extreme temperatures and humidity will make it almost impossible for people to be outside in many parts of the world. Researchers have found that periods of extreme humid heat have more than doubled since 1979, and some places have already had wet-bulb temperatures at the limits of what scientists think humans can tolerate under ideal conditions, meaning for people in perfect health, completely unclothed, in gale-force winds, performing no activity. Obviously that’s less than ideal for most of us and helps explain why thousands of people die at temperatures much lower than our upper limit.

Dr. Ebi pointed out that the good news is that many local communities with a long history of managing high temperatures have a lot of knowledge to share with regions that are newly dealing with these conditions. This includes how local areas develop early warning and response systems with specific action plans.

But, she cautions, it’s going to take a lot of coordination and a lot of behavior change to stabilize the earth’s climate, understand our weak points, and protect our health.

For Dr. Moseson, this reality has hit home.

“I already spent the year being terrified that I as an ICU doctor was going to be the one who gave my mom COVID. Finally I’m vaccinated, she’s vaccinated. Now I’ve watched someone die because they don’t have AC. And my parents, they’re old-school Oregonians, they don’t have AC.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Millions of Americans have been languishing for weeks in the oppressive heat and humidity of a merciless summer. Deadly heat has already taken the lives of hundreds in the Pacific Northwest alone, with numbers likely to grow as the full impact of heat-related deaths eventually comes to light.

In the final week of July, the National Weather Service issued excessive heat warnings for 17 states, stretching from the West Coast, across the Midwest, down south into Louisiana and Georgia. Temperatures 10° to 15° F above average threaten the lives and livelihoods of people all across the country.

After a scorching heat wave in late June, residents of the Pacific Northwest are once again likely to see triple-digit temperatures in the coming days. With the heat, hospitals may face another surge of people with heat-related illnesses.

Erika Moseson, MD, a lung and intensive care specialist, witnessed firsthand the life-threatening impacts of soaring temperatures. She happened to be running her 10-bed intensive care unit in a suburban hospital in Gresham, Ore., about 15 miles east of Portland, the weekend of June 26. Within 12 hours, almost half her ICU beds were filled with people found unconscious on the street, in the bushes, or in their own beds, all because their body’s defenses had become overwhelmed by heat.

“It was unidentified person after unidentified person, coming in, same story, temperatures through the roof, comatose,” Dr. Moseson recalled. Young people in their 20s with muscle breakdown markers through the roof, a sign of rhabdomyolysis; people with no other medical problems that would have put them in a high-risk category.

As a lifelong Oregonian, she’d never seen anything like this before. “We’re all trained for it. I know what happens to you if you have heatstroke, I know how to treat it,” she trailed off, still finding it hard to believe. Still reeling from the number of cases in just a few hours. Still shocked that this happened on what’s supposed to be the cooler, rainforest side of Oregon.

Among those she treated and resuscitated, the memory of a patient that she lost continues to gnaw at her.

“I’ve gone back to it day after day since it happened,” she reflected.

Adults, in their 50s, living at home with their children. Just 1 hour prior, they’d all said goodnight. Then 1 hour later, when a child came to check in, both parents were unconscious.

Dr. Moseson shared how her team tried everything in their power for 18 hours to save the parent that was brought to her ICU. But like hundreds of others who went through the heat wave that weekend, her patient didn’t survive.

It was too late. From Dr. Moseson’s experience, it’s what happens “if you’re cooking a human.”

How heat kills

Regardless of where we live on the planet, humans maintain a consistent internal temperature around 98° F for our systems to function properly.

Our bodies have an entire temperature-regulating system to balance heat gain with heat loss so we don’t stray too far from our ideal range. The hypothalamus functions as the thermostat, communicating with heat sensors in our skin, muscles, and spinal cord. Based on signals about our core body temperature, our nervous system makes many decisions for us – opening up blood vessels in the peripheral parts of our body, pushing more blood toward the skin, and activating sweat glands to produce more sweat.

Sweat is one of the most powerful tools we have to maintain a safe internal temperature. Of course, there are some things under our control, such as removing clothing, drinking more water, and finding shade (or preferably air conditioning). But beyond that, it’s our ability to sweat that keeps us cool. When sweat evaporates into the air, heat from our skin goes with it, cooling us off.

Over time, our sweat response can work better as we get used to warmer environments, a process that’s known as acclimatization. Over the period of a few days to weeks, the sweat glands of acclimated people can start making sweat at lower temperatures, produce more sweat, and absorb more salt back into our system, all to make us more efficient “sweaters.”

While someone who’s not used to the heat may only produce 1 liter of sweat per hour, people who have become acclimated can produce 2-3 liters every hour, allowing evaporation to eliminate more than two times the amount of heat.

Because the process of acclimatization can take some time, typically it’s the first throes of summer, or heat waves in places where people don’t typically see high temperatures, that are the most deadly. And of course, the right infrastructure, like access to air conditioning, also plays a large role in limiting heat-related death and hospitalization.

A 2019 study showed that heat-related hospitalizations peak at different temperatures in different places. For example, hospitalizations typically peak in Texas when the temperature hits 105° F. But they might be highest in the Pacific Northwest at just 81° F.

Even with acclimatization, there are limits to how much our bodies can adapt to heat. When the humidity goes up past 75%, there’s already so much moisture in the air that heat loss through evaporation no longer occurs.

It’s this connection between heat and humidity that can be deadly. This is why the heat index (a measure that takes into account temperature and relative humidity) and wet bulb globe temperature (a measure commonly used by the military and competitive athletes that takes into account temperature, humidity, wind speed, sun angle, and cloud cover) are both better at showing how dangerous the heat may be for our health, compared to temperature alone.

Kristie L. Ebi, PhD, a professor in the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the University of Washington, Seattle, has been studying the effects of heat and other climate-sensitive conditions on health for over 20 years. She stresses that it’s not just the recorded temperatures, but the prolonged exposure that kills.

If you never get a chance to bring down that core body temperature, if your internal temperatures stay above the range where your cells and your organs can work well for a long time, that’s when you can have the most dangerous effects of heat.

“It depends then on your age, your fitness, your individual physiology, underlying medical conditions, to how quickly that could affect the functioning of those organs. There’s lots of variability in there,” Dr. Ebi said.

Our hearts take on the brunt of the early response, working harder to pump blood toward the skin. Water and salt loss through our skin can start to cause electrolyte changes that can cause heat cramps and heat exhaustion. We feel tired, nauseated, dizzy. With enough water loss, we may become dehydrated, limiting the blood flow to our brains, causing us to pass out.

These early signs are like a car’s check engine light – systems are already being damaged, but resting, refueling, and, most importantly, turning off the heat are critical steps to prevent fatal injury.

If hazardous heat exposure continues and our internal temperatures continue to rise, nerves stop talking to each other, the proteins in our body unfold and lose their shape, and the cells of our organs disintegrate. This in turn sets off a fire alarm in our blood vessels, where a variety of chemical messengers, including “heat-shock proteins,” are released. The release of these inflammatory proteins, coupled with the loss of blood flow, eventually leads to the death of cells throughout the body, from the brain, to the heart, the muscles, and the kidneys.

This process is referred to as heatstroke. In essence, we melt from the inside.

At a certain point, this cascade can’t be reversed. Just like when you cool a melting block of ice, the parts that have melted will not go back to their original shape. It’s a similar process in our bodies, so delays in cooling and treatment can lead to death rates as high as 80%.

On the outside, we see people who look confused and disoriented, with hot skin and rapid breathing, and they may eventually become unconscious. Core body temperatures over 105° F clinch the diagnosis, but at the first sign of feeling unwell, cooling should be started.

There is no fancier or more effective treatment than that: Cool right away. In emergency rooms in Washington State, doctors used body bags filled with ice and water to cool victims of the heat wave in late June.

“It was all from heat ... that’s the thing, you feel so idiotic ... you’re like, ‘I’ve given you ice’ ... you bring their temperature down. But it’s already set off this cascade that you can’t stop,” Dr. Moseson said.

By the time Dr. Moseson’s patient made it to her, cooling with ice was just the beginning of the attempts to resuscitate and revive. The patient was already showing evidence of a process causing widespread bleeding and clotting, known as disseminated intravascular coagulation, along with damage to the heart and failing kidneys. Over 18 hours, her team cooled the patient, flooded the blood vessels with fluids and blood products, attempted to start dialysis, and inserted a breathing tube – all of the technology that is used to save people from serious cardiovascular collapse from other conditions. But nothing could reverse the melting that had already occurred.

Deaths from heat are 100% preventable. Until they’re not.

No respite

As Dr. Ebi says, the key to preventing heat-related death is to cool down enough to stabilize our internal cells and proteins before the irreversible cascade begins.

But for close to 80% of Americans who live in urban areas, temperatures can be even higher and more intolerable compared to surrounding areas because of the way we’ve designed our cities. In effect, we have unintentionally created hot zones called “urban heat islands.”

Jeremy Hoffman, PhD, chief scientist for the Science Museum of Virginia, explains that things like bricks, asphalt, and parking lots absorb more of the sun’s energy throughout the day and then emit that back into the air as heat throughout the afternoon and into the evening. This raises the air and surface temperatures in cities, relative to rural areas. When temperatures don’t cool enough at night, there’s no way to recover from the day’s heat. You start the next day still depleted, with less reserve to face the heat of a new day.

When you dig even deeper, it turns out that even within the same city, there are huge “thermal inequities,” as Dr. Hoffman calls them. In a 2019 study, he found that wealthier parts of cities had more natural spaces such as parks and tree-lined streets, compared to areas that had been intentionally “redlined,” or systematically deprived of investment. This pattern repeats itself in over 100 urban areas across the country and translates to huge temperature differences on the order of 10-20 degrees Fahrenheit within the same city, at the exact same time during a heat wave.

“In some ways, the way that we’ve decided to plan and build our cities physically turns up the thermostat by several tens of degrees during heat waves in particular neighborhoods,” Dr. Hoffman said.

Dr. Hoffman’s work showed that the city of Portland (where the death toll from the heat wave in late June was the highest) had some of the most intense differences between formerly redlined vs. tree-lined areas out of the more than 100 cities that he studied.

“Watching it play out, I was really concerned, not only as a climate scientist, but as a human. Understanding the urban heat island effect and the extreme nature of the inequity in our cities, thermally and otherwise, once you start to really recognize it, you can’t forget it.”

The most vulnerable

When it comes to identifying and protecting the people most vulnerable to heat stress and heat-related death, there is an ever-growing list of those most at risk. Unfortunately, very few recognize when they themselves are at risk, often until it’s too late.

According to Linda McCauley, PhD, dean of the Emory University School of Nursing in Atlanta, “the scope of who is vulnerable is quickly increasing.”

For example, we’re used to recognizing that pregnant women and young children are at risk. Public health campaigns have long advised us not to leave young children and pets in hot cars. We know that adolescents who play sports during hot summer months are at high risk for heat-related events and even death.

In Georgia, a 15-year-old boy collapsed and died after his first day back at football practice when the heat index was 105° F on July 26, even as it appears that all protocols for heat safety were being followed.

We recognize that outdoor workers face devastating consequences from prolonged exertion in the heat and must have safer working conditions.

The elderly and those with long-term medical and mental health conditions are also more vulnerable to heat. The elderly may not have the same warning signs and may not recognize that they are dehydrated until it is too late. In addition, their sweating mechanism weakens, and they may be taking medicines that interfere with their ability to regulate their temperature.

Poverty and inadequate housing are risk factors, especially for those in urban heat islands. For many people, their housing does not have enough cooling to protect them, and they can’t safely get themselves to cooling shelters.

These patterns for the most vulnerable fit for the majority of deaths in Oregon during the late June heat wave. Most victims were older, lived alone, and didn’t have air conditioning. But with climate change, the predictions are that temperatures will go higher and heat waves will last longer.

“There’s probably very few people today that are ‘immune’ to the effects of heat-related stress with climate change. All of us can be put in situations where we are susceptible,” Dr. McCauley said.

Dr. Moseson agreed. Many of her patients fit none of these risk categories – she treated people with no health problems in their 20s in her ICU, and the patient she lost would not traditionally have been thought of as high risk. That 50-something patient had no long-standing medical problems, and lived with family in a newly renovated suburban home that had air conditioning. The only problem was that the air conditioner had broken and there had been no rush to fix it based on past experience with Oregon summers.

Preventing heat deaths

Protecting ourselves and our families means monitoring the “simple things.” The first three rules are to make sure we’re drinking plenty of water – this means drinking whether we feel thirsty or not. If we’re not in an air-conditioned place, we’ve got to look for shade. And we need to take regular rest breaks.

Inside a home without air conditioning, placing ice in front of a fan to cool the air can work, but realistically, if you are in a place without air conditioning and the temperatures are approaching 90° F, it’s safest to find another place to stay, if possible.

For those playing sports, there are usually 1-week to 2-week protocols that allow for acclimatization when the season begins – this means starting slowly, without gear, and ramping up activity. Still, parents and coaches should watch advanced weather reports to make sure it’s safe to practice outside.

How we dress can also help us, so light clothing is key. And if we’re able to schedule activities for times when it is cooler, that can also protect us from overheating.

If anyone shows early signs of heat stress, removing clothing, cooling their bodies with cold water, and getting them out of the heat is critical. Any evidence of heatstroke is an emergency, and 911 should be called without delay. The faster the core temperature can be dropped, the better the chances for recovery.

On the level of communities, access to natural air conditioning in the form of healthy tree canopies, and trees at bus stops to provide shade can help a lot. According to Dr. Hoffman, these investments help almost right away. Reimagining our cities to remove the “hot zones” that we have created is another key to protecting ourselves as our climate changes.

Reaching our limits in a changing climate

Already, we are seeing more intense, more frequent, and longer-lasting heat waves throughout the country and across the globe.

Dr. Ebi, a coauthor of a recently released scientific analysis that found that the late June Pacific Northwest heat wave would have been virtually impossible without climate change, herself lived through the scorching temperatures in Seattle. Her work shows that the changing climate is killing us right now.

We are approaching a time where extreme temperatures and humidity will make it almost impossible for people to be outside in many parts of the world. Researchers have found that periods of extreme humid heat have more than doubled since 1979, and some places have already had wet-bulb temperatures at the limits of what scientists think humans can tolerate under ideal conditions, meaning for people in perfect health, completely unclothed, in gale-force winds, performing no activity. Obviously that’s less than ideal for most of us and helps explain why thousands of people die at temperatures much lower than our upper limit.

Dr. Ebi pointed out that the good news is that many local communities with a long history of managing high temperatures have a lot of knowledge to share with regions that are newly dealing with these conditions. This includes how local areas develop early warning and response systems with specific action plans.

But, she cautions, it’s going to take a lot of coordination and a lot of behavior change to stabilize the earth’s climate, understand our weak points, and protect our health.

For Dr. Moseson, this reality has hit home.

“I already spent the year being terrified that I as an ICU doctor was going to be the one who gave my mom COVID. Finally I’m vaccinated, she’s vaccinated. Now I’ve watched someone die because they don’t have AC. And my parents, they’re old-school Oregonians, they don’t have AC.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Delta variant could drive herd immunity threshold over 80%

Because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily than the original virus, the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity could be upward of 80% or more, experts say.

Also, it could be time to consider wearing an N95 mask in public indoor spaces regardless of vaccination status, according to a media briefing on Aug. 3 sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Furthermore, giving booster shots to the fully vaccinated is not the top public health priority now. Instead, third vaccinations should be reserved for more vulnerable populations – and efforts should focus on getting first vaccinations to unvaccinated people in the United States and around the world.

“The problem here is that the Delta variant is ... more transmissible than the original virus. That pushes the overall population herd immunity threshold much higher,” Ricardo Franco, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said during the briefing.

“For Delta, those threshold estimates go well over 80% and may be approaching 90%,” he said.

To put that figure in context, the original SARS-CoV-2 virus required an estimated 67% of the population to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Also, measles has one of the highest herd immunity thresholds at 95%, Dr. Franco added.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people are immunized that the entire population gains protection. And it’s already happening. “Unvaccinated people are actually benefiting from greater herd immunity protection in high-vaccination counties compared to low-vaccination ones,” he said.

Maximize mask protection

Unlike early in the COVID-19 pandemic with widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, face masks are now readily available. This includes N95 masks, which offer enhanced protection against SARS-CoV-2, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, said during the briefing.

Following the July 27 CDC recommendation that most Americans wear masks indoors when in public places, “I do think we need to upgrade our masks,” said Dr. Emanuel, who is Diane v.S. Levy & Robert M. Levy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It’s not just any mask,” he added. “Good masks make a big difference and are very important.”

Mask protection is about blocking 0.3-mcm particles, “and I think we need to make sure that people have masks that can filter that out,” he said. Although surgical masks are very good, he added, “they’re not quite as good as N95s.” As their name implies, N95s filter out 95% of these particles.

Dr. Emanuel acknowledged that people are tired of COVID-19 and complying with public health measures but urged perseverance. “We’ve sacrificed a lot. We should not throw it away in just a few months because we are tired. We’re all tired, but we do have to do the little bit extra getting vaccinated, wearing masks indoors, and protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities.”

Dealing with a disconnect

In response to a reporter’s question about the possibility that the large crowd at the Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago could become a superspreader event, Dr. Emanuel said, “it is worrisome.”

“I would say that, if you’re going to go to a gathering like that, wearing an N95 mask is wise, and not spending too long at any one place is also wise,” he said.

On the plus side, the event was held outdoors with lots of air circulation, Dr. Emanuel said.

However, “this is the kind of thing where we’ve got a sort of disconnect between people’s desire to get back to normal ... and the fact that we’re in the middle of this upsurge.”

Another potential problem is the event brought people together from many different locations, so when they travel home, they could be “potentially seeding lots of other communities.”

Boosters for some, for now

Even though not officially recommended, some fully vaccinated Americans are seeking a third or booster vaccination on their own.

Asked for his opinion, Dr. Emanuel said: “We’re probably going to have to be giving boosters to immunocompromised people and people who are susceptible. That’s where we are going to start.”

More research is needed regarding booster shots, he said. “There are very small studies – and the ‘very small’ should be emphasized – given that we’ve given shots to over 160 million people.”

“But it does appear that the boosters increase the antibodies and protection,” he said.

Instead of boosters, it is more important for people who haven’t been vaccinated to get fully vaccinated.

“We need to put our priorities in the right places,” he said.

Emanuel noted that, except for people in rural areas that might have to travel long distances, access to vaccines is no longer an issue. “It’s very hard not to find a vaccine if you want it.”

A remaining hurdle is “battling a major disinformation initiative. I don’t think this is misinformation. I think there’s very clear evidence that it is disinformation – false facts about the vaccines being spread,” Dr. Emanuel said.

The breakthrough infection dilemma

Breakthrough cases “remain the vast minority of infections at this time ... that is reassuring,” Dr. Franco said.

Also, tracking symptomatic breakthrough infections remains easier than studying fully vaccinated people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 but remain symptom free.

“We really don’t have a good handle on the frequency of asymptomatic cases,” Dr. Emanuel said. “If you’re missing breakthrough infections, a lot of them, you may be missing some [virus] evolution that would be very important for us to follow.” This missing information could include the emergence of new variants.

The asymptomatic breakthrough cases are the most worrisome group,” Dr. Emanuel said. “You get infected, you’re feeling fine. Maybe you’ve got a little sneeze or cough, but nothing unusual. And then you’re still able to transmit the Delta variant.”

The big picture

The upsurge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths is a major challenge, Dr. Emanuel said. “We need to address that by getting many more people vaccinated right now with what are very good vaccines.”

“But it also means that we have to stop being U.S. focused alone.” He pointed out that Delta and other variants originated overseas, “so getting the world vaccinated ... has to be a top priority.”

“We are obviously all facing a challenge as we move into the fall,” Dr. Emanuel said. “With schools opening and employers bringing their employees back together, even if these groups are vaccinated, there are going to be major challenges for all of us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily than the original virus, the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity could be upward of 80% or more, experts say.

Also, it could be time to consider wearing an N95 mask in public indoor spaces regardless of vaccination status, according to a media briefing on Aug. 3 sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Furthermore, giving booster shots to the fully vaccinated is not the top public health priority now. Instead, third vaccinations should be reserved for more vulnerable populations – and efforts should focus on getting first vaccinations to unvaccinated people in the United States and around the world.

“The problem here is that the Delta variant is ... more transmissible than the original virus. That pushes the overall population herd immunity threshold much higher,” Ricardo Franco, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said during the briefing.

“For Delta, those threshold estimates go well over 80% and may be approaching 90%,” he said.

To put that figure in context, the original SARS-CoV-2 virus required an estimated 67% of the population to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Also, measles has one of the highest herd immunity thresholds at 95%, Dr. Franco added.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people are immunized that the entire population gains protection. And it’s already happening. “Unvaccinated people are actually benefiting from greater herd immunity protection in high-vaccination counties compared to low-vaccination ones,” he said.

Maximize mask protection

Unlike early in the COVID-19 pandemic with widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, face masks are now readily available. This includes N95 masks, which offer enhanced protection against SARS-CoV-2, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, said during the briefing.

Following the July 27 CDC recommendation that most Americans wear masks indoors when in public places, “I do think we need to upgrade our masks,” said Dr. Emanuel, who is Diane v.S. Levy & Robert M. Levy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It’s not just any mask,” he added. “Good masks make a big difference and are very important.”

Mask protection is about blocking 0.3-mcm particles, “and I think we need to make sure that people have masks that can filter that out,” he said. Although surgical masks are very good, he added, “they’re not quite as good as N95s.” As their name implies, N95s filter out 95% of these particles.

Dr. Emanuel acknowledged that people are tired of COVID-19 and complying with public health measures but urged perseverance. “We’ve sacrificed a lot. We should not throw it away in just a few months because we are tired. We’re all tired, but we do have to do the little bit extra getting vaccinated, wearing masks indoors, and protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities.”

Dealing with a disconnect

In response to a reporter’s question about the possibility that the large crowd at the Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago could become a superspreader event, Dr. Emanuel said, “it is worrisome.”

“I would say that, if you’re going to go to a gathering like that, wearing an N95 mask is wise, and not spending too long at any one place is also wise,” he said.

On the plus side, the event was held outdoors with lots of air circulation, Dr. Emanuel said.

However, “this is the kind of thing where we’ve got a sort of disconnect between people’s desire to get back to normal ... and the fact that we’re in the middle of this upsurge.”

Another potential problem is the event brought people together from many different locations, so when they travel home, they could be “potentially seeding lots of other communities.”

Boosters for some, for now

Even though not officially recommended, some fully vaccinated Americans are seeking a third or booster vaccination on their own.

Asked for his opinion, Dr. Emanuel said: “We’re probably going to have to be giving boosters to immunocompromised people and people who are susceptible. That’s where we are going to start.”

More research is needed regarding booster shots, he said. “There are very small studies – and the ‘very small’ should be emphasized – given that we’ve given shots to over 160 million people.”

“But it does appear that the boosters increase the antibodies and protection,” he said.

Instead of boosters, it is more important for people who haven’t been vaccinated to get fully vaccinated.

“We need to put our priorities in the right places,” he said.

Emanuel noted that, except for people in rural areas that might have to travel long distances, access to vaccines is no longer an issue. “It’s very hard not to find a vaccine if you want it.”

A remaining hurdle is “battling a major disinformation initiative. I don’t think this is misinformation. I think there’s very clear evidence that it is disinformation – false facts about the vaccines being spread,” Dr. Emanuel said.

The breakthrough infection dilemma

Breakthrough cases “remain the vast minority of infections at this time ... that is reassuring,” Dr. Franco said.

Also, tracking symptomatic breakthrough infections remains easier than studying fully vaccinated people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 but remain symptom free.

“We really don’t have a good handle on the frequency of asymptomatic cases,” Dr. Emanuel said. “If you’re missing breakthrough infections, a lot of them, you may be missing some [virus] evolution that would be very important for us to follow.” This missing information could include the emergence of new variants.

The asymptomatic breakthrough cases are the most worrisome group,” Dr. Emanuel said. “You get infected, you’re feeling fine. Maybe you’ve got a little sneeze or cough, but nothing unusual. And then you’re still able to transmit the Delta variant.”

The big picture

The upsurge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths is a major challenge, Dr. Emanuel said. “We need to address that by getting many more people vaccinated right now with what are very good vaccines.”

“But it also means that we have to stop being U.S. focused alone.” He pointed out that Delta and other variants originated overseas, “so getting the world vaccinated ... has to be a top priority.”

“We are obviously all facing a challenge as we move into the fall,” Dr. Emanuel said. “With schools opening and employers bringing their employees back together, even if these groups are vaccinated, there are going to be major challenges for all of us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily than the original virus, the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity could be upward of 80% or more, experts say.

Also, it could be time to consider wearing an N95 mask in public indoor spaces regardless of vaccination status, according to a media briefing on Aug. 3 sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Furthermore, giving booster shots to the fully vaccinated is not the top public health priority now. Instead, third vaccinations should be reserved for more vulnerable populations – and efforts should focus on getting first vaccinations to unvaccinated people in the United States and around the world.

“The problem here is that the Delta variant is ... more transmissible than the original virus. That pushes the overall population herd immunity threshold much higher,” Ricardo Franco, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said during the briefing.

“For Delta, those threshold estimates go well over 80% and may be approaching 90%,” he said.

To put that figure in context, the original SARS-CoV-2 virus required an estimated 67% of the population to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Also, measles has one of the highest herd immunity thresholds at 95%, Dr. Franco added.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people are immunized that the entire population gains protection. And it’s already happening. “Unvaccinated people are actually benefiting from greater herd immunity protection in high-vaccination counties compared to low-vaccination ones,” he said.

Maximize mask protection

Unlike early in the COVID-19 pandemic with widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, face masks are now readily available. This includes N95 masks, which offer enhanced protection against SARS-CoV-2, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, said during the briefing.

Following the July 27 CDC recommendation that most Americans wear masks indoors when in public places, “I do think we need to upgrade our masks,” said Dr. Emanuel, who is Diane v.S. Levy & Robert M. Levy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It’s not just any mask,” he added. “Good masks make a big difference and are very important.”

Mask protection is about blocking 0.3-mcm particles, “and I think we need to make sure that people have masks that can filter that out,” he said. Although surgical masks are very good, he added, “they’re not quite as good as N95s.” As their name implies, N95s filter out 95% of these particles.

Dr. Emanuel acknowledged that people are tired of COVID-19 and complying with public health measures but urged perseverance. “We’ve sacrificed a lot. We should not throw it away in just a few months because we are tired. We’re all tired, but we do have to do the little bit extra getting vaccinated, wearing masks indoors, and protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities.”

Dealing with a disconnect

In response to a reporter’s question about the possibility that the large crowd at the Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago could become a superspreader event, Dr. Emanuel said, “it is worrisome.”

“I would say that, if you’re going to go to a gathering like that, wearing an N95 mask is wise, and not spending too long at any one place is also wise,” he said.

On the plus side, the event was held outdoors with lots of air circulation, Dr. Emanuel said.

However, “this is the kind of thing where we’ve got a sort of disconnect between people’s desire to get back to normal ... and the fact that we’re in the middle of this upsurge.”

Another potential problem is the event brought people together from many different locations, so when they travel home, they could be “potentially seeding lots of other communities.”

Boosters for some, for now

Even though not officially recommended, some fully vaccinated Americans are seeking a third or booster vaccination on their own.

Asked for his opinion, Dr. Emanuel said: “We’re probably going to have to be giving boosters to immunocompromised people and people who are susceptible. That’s where we are going to start.”

More research is needed regarding booster shots, he said. “There are very small studies – and the ‘very small’ should be emphasized – given that we’ve given shots to over 160 million people.”

“But it does appear that the boosters increase the antibodies and protection,” he said.

Instead of boosters, it is more important for people who haven’t been vaccinated to get fully vaccinated.

“We need to put our priorities in the right places,” he said.

Emanuel noted that, except for people in rural areas that might have to travel long distances, access to vaccines is no longer an issue. “It’s very hard not to find a vaccine if you want it.”

A remaining hurdle is “battling a major disinformation initiative. I don’t think this is misinformation. I think there’s very clear evidence that it is disinformation – false facts about the vaccines being spread,” Dr. Emanuel said.

The breakthrough infection dilemma

Breakthrough cases “remain the vast minority of infections at this time ... that is reassuring,” Dr. Franco said.

Also, tracking symptomatic breakthrough infections remains easier than studying fully vaccinated people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 but remain symptom free.

“We really don’t have a good handle on the frequency of asymptomatic cases,” Dr. Emanuel said. “If you’re missing breakthrough infections, a lot of them, you may be missing some [virus] evolution that would be very important for us to follow.” This missing information could include the emergence of new variants.

The asymptomatic breakthrough cases are the most worrisome group,” Dr. Emanuel said. “You get infected, you’re feeling fine. Maybe you’ve got a little sneeze or cough, but nothing unusual. And then you’re still able to transmit the Delta variant.”

The big picture

The upsurge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths is a major challenge, Dr. Emanuel said. “We need to address that by getting many more people vaccinated right now with what are very good vaccines.”

“But it also means that we have to stop being U.S. focused alone.” He pointed out that Delta and other variants originated overseas, “so getting the world vaccinated ... has to be a top priority.”

“We are obviously all facing a challenge as we move into the fall,” Dr. Emanuel said. “With schools opening and employers bringing their employees back together, even if these groups are vaccinated, there are going to be major challenges for all of us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Increases in new COVID cases among children far outpace vaccinations

New COVID-19 cases in children soared by almost 86% over the course of just 1 week, while the number of 12- to 17-year-old children who have received at least one dose of vaccine rose by 5.4%, according to two separate sources.

Meanwhile, the increase over the past 2 weeks – from 23,551 new cases for July 16-22 to almost 72,000 – works out to almost 205%, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children represented 19.0% of the cases reported during the week of July 23-29, and they have made up 14.3% of all cases since the pandemic began, with the total number of cases in children now approaching 4.2 million, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. About 22% of the U.S. population is under the age of 18 years.

As of Aug. 2, just over 9.8 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine, which was up by about 500,000, or 5.4%, from a week earlier, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Children aged 16-17 have reached a notable milestone on the journey that started with vaccine approval in December: 50.2% have gotten at least one dose and 40.3% are fully vaccinated. Among children aged 12-15 years, the proportion with at least one dose of vaccine is up to 39.5%, compared with 37.1% the previous week, while 29.0% are fully vaccinated (27.8% the week before), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

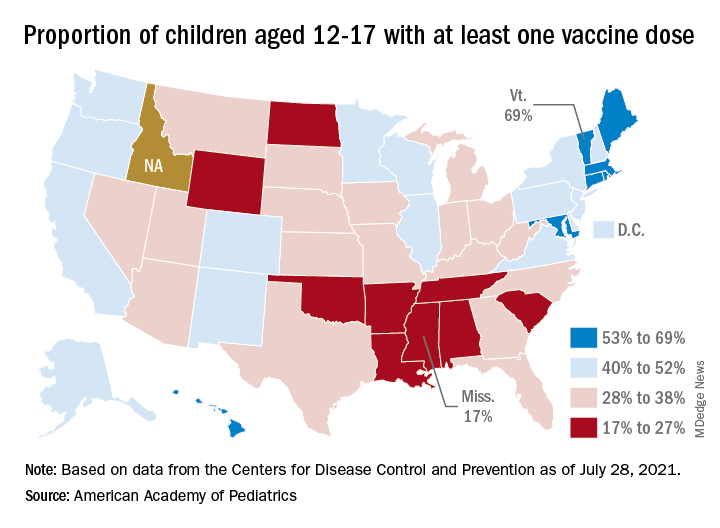

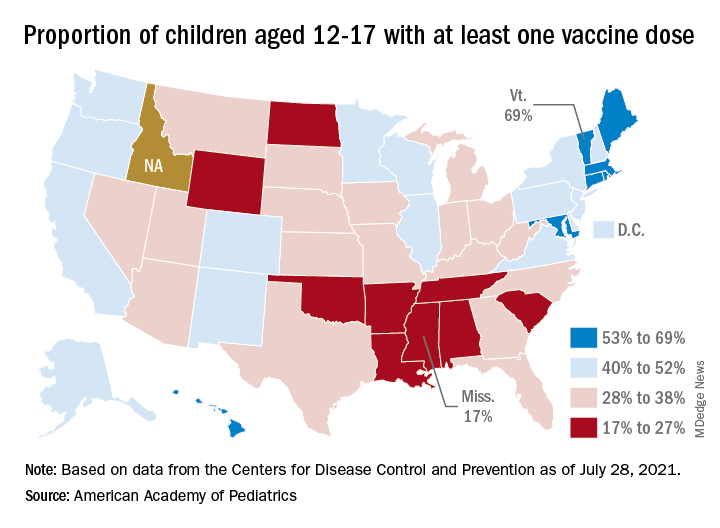

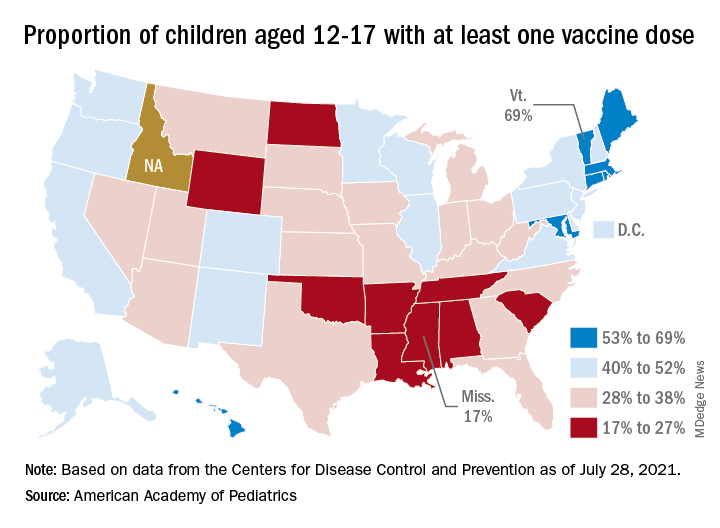

The national rates for child vaccination, however, tend to hide the disparities between states. There is a gap between Mississippi (lowest), where just 17% of children aged 12-17 years have gotten at least one dose, and Vermont (highest), which is up to 69%. Vermont also has the highest rate of vaccine completion (60%), while Alabama and Mississippi have the lowest (10%), according to a solo report from the AAP.

New COVID-19 cases in children soared by almost 86% over the course of just 1 week, while the number of 12- to 17-year-old children who have received at least one dose of vaccine rose by 5.4%, according to two separate sources.

Meanwhile, the increase over the past 2 weeks – from 23,551 new cases for July 16-22 to almost 72,000 – works out to almost 205%, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children represented 19.0% of the cases reported during the week of July 23-29, and they have made up 14.3% of all cases since the pandemic began, with the total number of cases in children now approaching 4.2 million, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. About 22% of the U.S. population is under the age of 18 years.

As of Aug. 2, just over 9.8 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine, which was up by about 500,000, or 5.4%, from a week earlier, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Children aged 16-17 have reached a notable milestone on the journey that started with vaccine approval in December: 50.2% have gotten at least one dose and 40.3% are fully vaccinated. Among children aged 12-15 years, the proportion with at least one dose of vaccine is up to 39.5%, compared with 37.1% the previous week, while 29.0% are fully vaccinated (27.8% the week before), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.