User login

News and Views that Matter to Pediatricians

The leading independent newspaper covering news and commentary in pediatrics.

Washington medical board charges doctor with spreading COVID misinformation

Doctors and professional organizations are standing guard, hoping to protect patients from any harm that results from mistruths spread by colleagues.

Case in point: Several physicians and the American Board of Pathology filed complaints with Washington and Idaho medical boards alleging that Ryan Cole, MD, a board-certified pathologist who practices in Boise, Idaho, but who also holds a license in Washington, has spread antivaccine and pro-ivermectin statements on social media. Dr. Cole is one of the founders of America’s Frontline Doctors, a right-wing political organization. Dr. Cole did not respond to a request for comment.

Gary W. Procop, MD, CEO, American Board of Pathology, told this news organization that “as physicians and board-certified pathologists, we have a public trust, and we must be accountable to patients, society, and the profession. Misinformation can cause real harm to patients, which may include death. Misinformation diverts patients away from lifesaving vaccination and other preventive measures, promotes viral transmission, and recommends ineffective therapies that may be toxic instead of evidence-based medical care.”

Cavalcade of complaints

Several doctors also chimed in with formal complaints alleging that Cole is spreading unreliable information, according to a report from KTVB News. For example, a Boise doctor wrote in his complaint that Dr. Cole is “a major purveyor of misinformation” and called it “amazing” that the physician was continuing to publicly support debunked information about COVID-19 more than a year into the pandemic. The doctor also stated, “Cole is a health menace, abusing his status as a physician to mislead the public.”

As a result of such complaints, the Washington medical board has charged Cole with COVID-19–related violations. It is unclear whether or not the Idaho medical board will sanction the doctor. At least 12 medical boards have sanctioned doctors for similar violations since the start of the pandemic.

The statement of charges from the Washington medical board contends that since March 2021, Dr. Cole has made numerous misleading statements regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccines, the use of ivermectin to treat COVID-19, and the effectiveness of masks.

In addition, the statement alleges that Dr. Cole treated several COVID-19 patients via telemedicine. During these sessions, he prescribed ivermectin, an antiparasite drug that has not been found to have any effectiveness in treating, curing, or preventing COVID-19. One of the patients died after receiving this treatment, according to the complaint.

Citing a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Procop pointed out that use of ivermectin, which is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19, is particularly troubling.

“There is a concern whenever an ineffective treatment is prescribed when more effective and scientifically proven therapies are available. Therapeutics have potential side effects, and toxicities have been associated with the use of ivermectin,” Dr. Procop said. “The benefits of therapy should always outweigh the risks of treatment.”

If the Washington medical board finds that Dr. Cole has engaged in unprofessional conduct, possible sanctions include revocation or suspension of his license. Washington state law also provides for a range of other possible sanctions, including restriction or limitation of his practice, requiring that he complete a specific program of remedial education or treatment, monitoring of his practice, censure or reprimand, probation, a fine of up to $5,000 for each violation, or refunding fees that his practice has billed to and collected from patients. Dr. Cole had until January 30 to respond to the medical board’s statement.

“The American Board of Pathology supports the actions of the Washington State Medical Board regarding their inquiries into any physician that holds license in their state who makes false and misleading medical claims, or provides medical care beyond their scope of practice, as indicated by their training,” Dr. Procop said.

Law in limbo

While medical boards are seeking to sanction professionals who spread falsehoods, the pause button has been hit on the California law that allows regulators to punish doctors for spreading false information about COVID-19 vaccinations and treatments.

The law went into effect Jan. 1 but was temporarily halted when U.S. District Judge William B. Shubb of the Eastern District of California granted a preliminary injunction against the law on Jan. 25, according to a report in the Sacramento Bee.

Mr. Shubb said the measure’s definition of “misinformation” was “unconstitutionally vague” under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. He also criticized the law’s definition of “misinformation” as being “grammatically incoherent.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors and professional organizations are standing guard, hoping to protect patients from any harm that results from mistruths spread by colleagues.

Case in point: Several physicians and the American Board of Pathology filed complaints with Washington and Idaho medical boards alleging that Ryan Cole, MD, a board-certified pathologist who practices in Boise, Idaho, but who also holds a license in Washington, has spread antivaccine and pro-ivermectin statements on social media. Dr. Cole is one of the founders of America’s Frontline Doctors, a right-wing political organization. Dr. Cole did not respond to a request for comment.

Gary W. Procop, MD, CEO, American Board of Pathology, told this news organization that “as physicians and board-certified pathologists, we have a public trust, and we must be accountable to patients, society, and the profession. Misinformation can cause real harm to patients, which may include death. Misinformation diverts patients away from lifesaving vaccination and other preventive measures, promotes viral transmission, and recommends ineffective therapies that may be toxic instead of evidence-based medical care.”

Cavalcade of complaints

Several doctors also chimed in with formal complaints alleging that Cole is spreading unreliable information, according to a report from KTVB News. For example, a Boise doctor wrote in his complaint that Dr. Cole is “a major purveyor of misinformation” and called it “amazing” that the physician was continuing to publicly support debunked information about COVID-19 more than a year into the pandemic. The doctor also stated, “Cole is a health menace, abusing his status as a physician to mislead the public.”

As a result of such complaints, the Washington medical board has charged Cole with COVID-19–related violations. It is unclear whether or not the Idaho medical board will sanction the doctor. At least 12 medical boards have sanctioned doctors for similar violations since the start of the pandemic.

The statement of charges from the Washington medical board contends that since March 2021, Dr. Cole has made numerous misleading statements regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccines, the use of ivermectin to treat COVID-19, and the effectiveness of masks.

In addition, the statement alleges that Dr. Cole treated several COVID-19 patients via telemedicine. During these sessions, he prescribed ivermectin, an antiparasite drug that has not been found to have any effectiveness in treating, curing, or preventing COVID-19. One of the patients died after receiving this treatment, according to the complaint.

Citing a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Procop pointed out that use of ivermectin, which is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19, is particularly troubling.

“There is a concern whenever an ineffective treatment is prescribed when more effective and scientifically proven therapies are available. Therapeutics have potential side effects, and toxicities have been associated with the use of ivermectin,” Dr. Procop said. “The benefits of therapy should always outweigh the risks of treatment.”

If the Washington medical board finds that Dr. Cole has engaged in unprofessional conduct, possible sanctions include revocation or suspension of his license. Washington state law also provides for a range of other possible sanctions, including restriction or limitation of his practice, requiring that he complete a specific program of remedial education or treatment, monitoring of his practice, censure or reprimand, probation, a fine of up to $5,000 for each violation, or refunding fees that his practice has billed to and collected from patients. Dr. Cole had until January 30 to respond to the medical board’s statement.

“The American Board of Pathology supports the actions of the Washington State Medical Board regarding their inquiries into any physician that holds license in their state who makes false and misleading medical claims, or provides medical care beyond their scope of practice, as indicated by their training,” Dr. Procop said.

Law in limbo

While medical boards are seeking to sanction professionals who spread falsehoods, the pause button has been hit on the California law that allows regulators to punish doctors for spreading false information about COVID-19 vaccinations and treatments.

The law went into effect Jan. 1 but was temporarily halted when U.S. District Judge William B. Shubb of the Eastern District of California granted a preliminary injunction against the law on Jan. 25, according to a report in the Sacramento Bee.

Mr. Shubb said the measure’s definition of “misinformation” was “unconstitutionally vague” under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. He also criticized the law’s definition of “misinformation” as being “grammatically incoherent.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors and professional organizations are standing guard, hoping to protect patients from any harm that results from mistruths spread by colleagues.

Case in point: Several physicians and the American Board of Pathology filed complaints with Washington and Idaho medical boards alleging that Ryan Cole, MD, a board-certified pathologist who practices in Boise, Idaho, but who also holds a license in Washington, has spread antivaccine and pro-ivermectin statements on social media. Dr. Cole is one of the founders of America’s Frontline Doctors, a right-wing political organization. Dr. Cole did not respond to a request for comment.

Gary W. Procop, MD, CEO, American Board of Pathology, told this news organization that “as physicians and board-certified pathologists, we have a public trust, and we must be accountable to patients, society, and the profession. Misinformation can cause real harm to patients, which may include death. Misinformation diverts patients away from lifesaving vaccination and other preventive measures, promotes viral transmission, and recommends ineffective therapies that may be toxic instead of evidence-based medical care.”

Cavalcade of complaints

Several doctors also chimed in with formal complaints alleging that Cole is spreading unreliable information, according to a report from KTVB News. For example, a Boise doctor wrote in his complaint that Dr. Cole is “a major purveyor of misinformation” and called it “amazing” that the physician was continuing to publicly support debunked information about COVID-19 more than a year into the pandemic. The doctor also stated, “Cole is a health menace, abusing his status as a physician to mislead the public.”

As a result of such complaints, the Washington medical board has charged Cole with COVID-19–related violations. It is unclear whether or not the Idaho medical board will sanction the doctor. At least 12 medical boards have sanctioned doctors for similar violations since the start of the pandemic.

The statement of charges from the Washington medical board contends that since March 2021, Dr. Cole has made numerous misleading statements regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccines, the use of ivermectin to treat COVID-19, and the effectiveness of masks.

In addition, the statement alleges that Dr. Cole treated several COVID-19 patients via telemedicine. During these sessions, he prescribed ivermectin, an antiparasite drug that has not been found to have any effectiveness in treating, curing, or preventing COVID-19. One of the patients died after receiving this treatment, according to the complaint.

Citing a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Procop pointed out that use of ivermectin, which is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19, is particularly troubling.

“There is a concern whenever an ineffective treatment is prescribed when more effective and scientifically proven therapies are available. Therapeutics have potential side effects, and toxicities have been associated with the use of ivermectin,” Dr. Procop said. “The benefits of therapy should always outweigh the risks of treatment.”

If the Washington medical board finds that Dr. Cole has engaged in unprofessional conduct, possible sanctions include revocation or suspension of his license. Washington state law also provides for a range of other possible sanctions, including restriction or limitation of his practice, requiring that he complete a specific program of remedial education or treatment, monitoring of his practice, censure or reprimand, probation, a fine of up to $5,000 for each violation, or refunding fees that his practice has billed to and collected from patients. Dr. Cole had until January 30 to respond to the medical board’s statement.

“The American Board of Pathology supports the actions of the Washington State Medical Board regarding their inquiries into any physician that holds license in their state who makes false and misleading medical claims, or provides medical care beyond their scope of practice, as indicated by their training,” Dr. Procop said.

Law in limbo

While medical boards are seeking to sanction professionals who spread falsehoods, the pause button has been hit on the California law that allows regulators to punish doctors for spreading false information about COVID-19 vaccinations and treatments.

The law went into effect Jan. 1 but was temporarily halted when U.S. District Judge William B. Shubb of the Eastern District of California granted a preliminary injunction against the law on Jan. 25, according to a report in the Sacramento Bee.

Mr. Shubb said the measure’s definition of “misinformation” was “unconstitutionally vague” under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. He also criticized the law’s definition of “misinformation” as being “grammatically incoherent.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Kid with glasses: Many children live far from pediatric eye care

More than 2,800 counties in the United States lack a practicing pediatric ophthalmologist, limiting easy access to specialized eye care, a new study found.

The review of public, online pediatric ophthalmology directories found 1,056 pediatric ophthalmologists registered. The majority of these doctors practiced in densely populated areas, leaving many poor and rural residents across the United States without a nearby doctor to visit, and with the burden of spending time and money to get care for their children.

Travel for that care may be out of reach for some, according to Hannah Walsh, a medical student at the University of Miami, who led the study published in JAMA Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh’s research found that the median income of families living in a county without a pediatric ophthalmologist was nearly $17,000 lower than that for families with access to such specialists (95% confidence interval, −$18,544 to −$14,389; P < .001). These families were also less likely to own a car.

“We found that counties that didn’t have access to ophthalmic care for pediatrics were already disproportionately affected by lower socioeconomic status,” she said.

Children often receive routine vision screenings through their primary care clinician, but children who fail a routine screening may need to visit a pediatric ophthalmologist for a full eye examination, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh and colleagues pulled data in March 2022 on the demographics of pediatric ophthalmologists from online directories hosted by the AAO and the American Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Ms. Walsh cautioned that the directories might include eye doctors who are no longer practicing, or there might be specialists who had not registered for the databases.

Yasmin Bradfield, MD, a pediatric ophthalmologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, noted that after the study published, pediatric ophthalmologists from Vermont and New Mexico notified study authors and AAPOS that they are practicing in the states.

Dr. Bradfield, a board member of AAPOS who also heads the organization’s recruitment task force, said the organization is aware of only one state – Wyoming – without a currently practicing pediatric ophthalmologist.

But based on the March 2022 data, Ms. Walsh and her colleagues found four states – New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont – did not have any pediatric ophthalmologists listed in directories for the organizations. Meanwhile, the country’s most populous states – California, New York, Florida, and Texas – had the most pediatric ophthalmologists.

For every million people, the study identified 7.7 pediatric ophthalmologists nationwide.

Julius T. Oatts, MD, the lead author of an accompanying editorial, said the findings are “valuable and sobering.” Even in San Francisco, where Dr. Oatts practices, most pediatric eye specialists have 6-month wait lists, he said.

Not fixing the shortage of children’s eye doctors could carry lifetime consequences, Dr. Oatts and his colleagues warned.

“Vision and eye health represent an important health barrier to learning in children,” Dr. Oatts and his colleagues wrote. “Lack of access to pediatric vision screening and care also contributes to the academic achievement gap and educational disparities.”

Dr. Bradfield said that disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care could leave some children at risk for losing their vision or never being able to see 20/20. Parents living in areas without a specialist may decide to instead visit an optometrist, but they are not trained to treat serious cases, such as strabismus, and only test and diagnose vision changes, according to AAPOS.

“If we don’t get to the kids in time, they can lose vision permanently, even if it’s something as simple as they just need glasses as a toddler,” Dr. Bradfield said.

Dr. Bradfield said AAPOS is recruiting new pediatric ophthalmologists by offering fellowships for medical students to attend the association’s annual conference and creating shadowing opportunities for students. The society also will release a survey of pediatric ophthalmology salaries to dispel rumors that the specialty does not have lucrative wages.

Ms. Walsh said she was interested in looking at disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care, in part, because she was surprised by how few of her classmates attending medical school were interested in the field of study.

“I hope it encourages ophthalmologists to consider pediatric ophthalmology, or to consider volunteering their time, or going to underserved areas to provide care to families that really are in need,” she said.

Coauthor Jayanth Sridhar, MD, reported receiving personal fees from Alcon, Apellis, Allergan, Dutch Ophthalmic Research Center, Genentech, OcuTerra Therapeutics, and Regeneron outside the submitted work. The other authors and the editorialists report no relevant financial relationships.

*This article was updated on 2/2/2023.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 2,800 counties in the United States lack a practicing pediatric ophthalmologist, limiting easy access to specialized eye care, a new study found.

The review of public, online pediatric ophthalmology directories found 1,056 pediatric ophthalmologists registered. The majority of these doctors practiced in densely populated areas, leaving many poor and rural residents across the United States without a nearby doctor to visit, and with the burden of spending time and money to get care for their children.

Travel for that care may be out of reach for some, according to Hannah Walsh, a medical student at the University of Miami, who led the study published in JAMA Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh’s research found that the median income of families living in a county without a pediatric ophthalmologist was nearly $17,000 lower than that for families with access to such specialists (95% confidence interval, −$18,544 to −$14,389; P < .001). These families were also less likely to own a car.

“We found that counties that didn’t have access to ophthalmic care for pediatrics were already disproportionately affected by lower socioeconomic status,” she said.

Children often receive routine vision screenings through their primary care clinician, but children who fail a routine screening may need to visit a pediatric ophthalmologist for a full eye examination, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh and colleagues pulled data in March 2022 on the demographics of pediatric ophthalmologists from online directories hosted by the AAO and the American Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Ms. Walsh cautioned that the directories might include eye doctors who are no longer practicing, or there might be specialists who had not registered for the databases.

Yasmin Bradfield, MD, a pediatric ophthalmologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, noted that after the study published, pediatric ophthalmologists from Vermont and New Mexico notified study authors and AAPOS that they are practicing in the states.

Dr. Bradfield, a board member of AAPOS who also heads the organization’s recruitment task force, said the organization is aware of only one state – Wyoming – without a currently practicing pediatric ophthalmologist.

But based on the March 2022 data, Ms. Walsh and her colleagues found four states – New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont – did not have any pediatric ophthalmologists listed in directories for the organizations. Meanwhile, the country’s most populous states – California, New York, Florida, and Texas – had the most pediatric ophthalmologists.

For every million people, the study identified 7.7 pediatric ophthalmologists nationwide.

Julius T. Oatts, MD, the lead author of an accompanying editorial, said the findings are “valuable and sobering.” Even in San Francisco, where Dr. Oatts practices, most pediatric eye specialists have 6-month wait lists, he said.

Not fixing the shortage of children’s eye doctors could carry lifetime consequences, Dr. Oatts and his colleagues warned.

“Vision and eye health represent an important health barrier to learning in children,” Dr. Oatts and his colleagues wrote. “Lack of access to pediatric vision screening and care also contributes to the academic achievement gap and educational disparities.”

Dr. Bradfield said that disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care could leave some children at risk for losing their vision or never being able to see 20/20. Parents living in areas without a specialist may decide to instead visit an optometrist, but they are not trained to treat serious cases, such as strabismus, and only test and diagnose vision changes, according to AAPOS.

“If we don’t get to the kids in time, they can lose vision permanently, even if it’s something as simple as they just need glasses as a toddler,” Dr. Bradfield said.

Dr. Bradfield said AAPOS is recruiting new pediatric ophthalmologists by offering fellowships for medical students to attend the association’s annual conference and creating shadowing opportunities for students. The society also will release a survey of pediatric ophthalmology salaries to dispel rumors that the specialty does not have lucrative wages.

Ms. Walsh said she was interested in looking at disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care, in part, because she was surprised by how few of her classmates attending medical school were interested in the field of study.

“I hope it encourages ophthalmologists to consider pediatric ophthalmology, or to consider volunteering their time, or going to underserved areas to provide care to families that really are in need,” she said.

Coauthor Jayanth Sridhar, MD, reported receiving personal fees from Alcon, Apellis, Allergan, Dutch Ophthalmic Research Center, Genentech, OcuTerra Therapeutics, and Regeneron outside the submitted work. The other authors and the editorialists report no relevant financial relationships.

*This article was updated on 2/2/2023.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 2,800 counties in the United States lack a practicing pediatric ophthalmologist, limiting easy access to specialized eye care, a new study found.

The review of public, online pediatric ophthalmology directories found 1,056 pediatric ophthalmologists registered. The majority of these doctors practiced in densely populated areas, leaving many poor and rural residents across the United States without a nearby doctor to visit, and with the burden of spending time and money to get care for their children.

Travel for that care may be out of reach for some, according to Hannah Walsh, a medical student at the University of Miami, who led the study published in JAMA Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh’s research found that the median income of families living in a county without a pediatric ophthalmologist was nearly $17,000 lower than that for families with access to such specialists (95% confidence interval, −$18,544 to −$14,389; P < .001). These families were also less likely to own a car.

“We found that counties that didn’t have access to ophthalmic care for pediatrics were already disproportionately affected by lower socioeconomic status,” she said.

Children often receive routine vision screenings through their primary care clinician, but children who fail a routine screening may need to visit a pediatric ophthalmologist for a full eye examination, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh and colleagues pulled data in March 2022 on the demographics of pediatric ophthalmologists from online directories hosted by the AAO and the American Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Ms. Walsh cautioned that the directories might include eye doctors who are no longer practicing, or there might be specialists who had not registered for the databases.

Yasmin Bradfield, MD, a pediatric ophthalmologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, noted that after the study published, pediatric ophthalmologists from Vermont and New Mexico notified study authors and AAPOS that they are practicing in the states.

Dr. Bradfield, a board member of AAPOS who also heads the organization’s recruitment task force, said the organization is aware of only one state – Wyoming – without a currently practicing pediatric ophthalmologist.

But based on the March 2022 data, Ms. Walsh and her colleagues found four states – New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont – did not have any pediatric ophthalmologists listed in directories for the organizations. Meanwhile, the country’s most populous states – California, New York, Florida, and Texas – had the most pediatric ophthalmologists.

For every million people, the study identified 7.7 pediatric ophthalmologists nationwide.

Julius T. Oatts, MD, the lead author of an accompanying editorial, said the findings are “valuable and sobering.” Even in San Francisco, where Dr. Oatts practices, most pediatric eye specialists have 6-month wait lists, he said.

Not fixing the shortage of children’s eye doctors could carry lifetime consequences, Dr. Oatts and his colleagues warned.

“Vision and eye health represent an important health barrier to learning in children,” Dr. Oatts and his colleagues wrote. “Lack of access to pediatric vision screening and care also contributes to the academic achievement gap and educational disparities.”

Dr. Bradfield said that disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care could leave some children at risk for losing their vision or never being able to see 20/20. Parents living in areas without a specialist may decide to instead visit an optometrist, but they are not trained to treat serious cases, such as strabismus, and only test and diagnose vision changes, according to AAPOS.

“If we don’t get to the kids in time, they can lose vision permanently, even if it’s something as simple as they just need glasses as a toddler,” Dr. Bradfield said.

Dr. Bradfield said AAPOS is recruiting new pediatric ophthalmologists by offering fellowships for medical students to attend the association’s annual conference and creating shadowing opportunities for students. The society also will release a survey of pediatric ophthalmology salaries to dispel rumors that the specialty does not have lucrative wages.

Ms. Walsh said she was interested in looking at disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care, in part, because she was surprised by how few of her classmates attending medical school were interested in the field of study.

“I hope it encourages ophthalmologists to consider pediatric ophthalmology, or to consider volunteering their time, or going to underserved areas to provide care to families that really are in need,” she said.

Coauthor Jayanth Sridhar, MD, reported receiving personal fees from Alcon, Apellis, Allergan, Dutch Ophthalmic Research Center, Genentech, OcuTerra Therapeutics, and Regeneron outside the submitted work. The other authors and the editorialists report no relevant financial relationships.

*This article was updated on 2/2/2023.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Similar brain atrophy in obesity and Alzheimer’s disease

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Expert offers insights on pediatric dermatology emergencies

ORLANDO – The eruption spread away from the head and her transaminase levels were “dramatic,” in the 700s, said Kalyani S. Marathe, MD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati.

Dr. Marathe, director of the division of dermatology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, reviewed this case in a presentation on pediatric dermatologic emergencies at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgery Conference, pointing out potential pitfalls and important aspects that might require swift action.

The patient was diagnosed with drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).

Facial involvement is common in pediatric cases of DRESS, but edema of the face is less common in children than adults, Dr. Marathe said.

Antiepileptic medications are the most common cause of DRESS, followed by antibiotics – most often, vancomycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, she said. But sometimes the trigger is not clear, she noted, recalling a vexing case she once saw in which IV contrast was eventually identified as the cause.

When DRESS is suspected, she said, lab work should be done during the acute eruption and after resolution. This should include CBC, liver function tests, creatinine, and urinalysis, and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) and thyroid testing.

Treatment typically includes supportive care, unless symptoms are systemic, or if there is impending liver failure, when steroids, cyclosporine, or IVIG can be used.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN): Mortality rates when these diseases overlap is 4%, Dr. Marathe said. Clues to diagnosing this other medication-induced condition include involvement of the palms and the soles of the feet; presence of the Nikolsky sign in which the top layers of the skin slip away from the lower layers when rubbed; mucosal involvement, which often precedes cutaneous involvement; and these symptoms occurring within the first 8 weeks of taking a medication, which are most commonly antibiotics and anti-epileptics.

Dr. Marathe underscored how important it is to get ophthalmology involved right away, because of the risk of vision loss. Amniotic membrane transfer to the eye at the time of diagnosis has been found to produce dramatically better outcomes, she said. The membrane has anti-inflammatory and antiscarring properties and can promote wound healing on the surface of the eye.

“I would recommend getting your ophthalmology team on board early because they have to advocate for these patients,” she said.

Corticosteroids and IVIG can improve ocular outcomes, but cyclosporine is associated with better mortality outcomes, she said. Emerging data on etanercept has also led to more use of that drug, she said.

Erythema multiforme (EM): unlike urticaria, multiforme EM can have mucosal involvement, Dr. Marathe said. Clinicians should look for three zones of color: A central duskiness, a rim of pallor, and a ring of erythema.

EM is triggered by a virus, which is usually herpes simplex virus (HSV). But she added that HSV is not always found. “So, there are certainly other triggers out there that we just haven’t identified,” she said.

If HSV is suspected, oral acyclovir is effective, she noted.

Other cases might not be as straightforward. Dr. Marathe said that during her fellowship, she saw a patient with EM that was controlled only by IVIG, so it was administered every 3 months. In that case, the trigger was never found.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): This syndrome can follow COVID-19 infection, and usually presents with 3-5 days of fever after COVID has resolved. It can include gastrointestinal, cardiorespiratory, and neurocognitive symptoms.

The skin presentation is mainly a morbilliform pattern, but clinicians might also see conjunctival involvement, mucosal involvement, and “COVID toes,” painful red or purple lesions on the toes.

Treatment is usually IVIG and systemic corticosteroids, with the treatment course depending on the severity.

MIS-C was initially thought to be Kawasaki’s disease, another autoinflammatory disorder, which is related but distinct, Dr. Marathe said.

Patients with MIS-C “are usually going to have COVID-positive antibodies,” she said. But since almost everybody may have COVID antibodies, “it’s not usually a helpful test for you now. But early on, that’s what we used as helpful indicator.”

Dr. Marathe reported no relevant financial relationships.

ORLANDO – The eruption spread away from the head and her transaminase levels were “dramatic,” in the 700s, said Kalyani S. Marathe, MD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati.

Dr. Marathe, director of the division of dermatology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, reviewed this case in a presentation on pediatric dermatologic emergencies at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgery Conference, pointing out potential pitfalls and important aspects that might require swift action.

The patient was diagnosed with drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).

Facial involvement is common in pediatric cases of DRESS, but edema of the face is less common in children than adults, Dr. Marathe said.

Antiepileptic medications are the most common cause of DRESS, followed by antibiotics – most often, vancomycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, she said. But sometimes the trigger is not clear, she noted, recalling a vexing case she once saw in which IV contrast was eventually identified as the cause.

When DRESS is suspected, she said, lab work should be done during the acute eruption and after resolution. This should include CBC, liver function tests, creatinine, and urinalysis, and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) and thyroid testing.

Treatment typically includes supportive care, unless symptoms are systemic, or if there is impending liver failure, when steroids, cyclosporine, or IVIG can be used.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN): Mortality rates when these diseases overlap is 4%, Dr. Marathe said. Clues to diagnosing this other medication-induced condition include involvement of the palms and the soles of the feet; presence of the Nikolsky sign in which the top layers of the skin slip away from the lower layers when rubbed; mucosal involvement, which often precedes cutaneous involvement; and these symptoms occurring within the first 8 weeks of taking a medication, which are most commonly antibiotics and anti-epileptics.

Dr. Marathe underscored how important it is to get ophthalmology involved right away, because of the risk of vision loss. Amniotic membrane transfer to the eye at the time of diagnosis has been found to produce dramatically better outcomes, she said. The membrane has anti-inflammatory and antiscarring properties and can promote wound healing on the surface of the eye.

“I would recommend getting your ophthalmology team on board early because they have to advocate for these patients,” she said.

Corticosteroids and IVIG can improve ocular outcomes, but cyclosporine is associated with better mortality outcomes, she said. Emerging data on etanercept has also led to more use of that drug, she said.

Erythema multiforme (EM): unlike urticaria, multiforme EM can have mucosal involvement, Dr. Marathe said. Clinicians should look for three zones of color: A central duskiness, a rim of pallor, and a ring of erythema.

EM is triggered by a virus, which is usually herpes simplex virus (HSV). But she added that HSV is not always found. “So, there are certainly other triggers out there that we just haven’t identified,” she said.

If HSV is suspected, oral acyclovir is effective, she noted.

Other cases might not be as straightforward. Dr. Marathe said that during her fellowship, she saw a patient with EM that was controlled only by IVIG, so it was administered every 3 months. In that case, the trigger was never found.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): This syndrome can follow COVID-19 infection, and usually presents with 3-5 days of fever after COVID has resolved. It can include gastrointestinal, cardiorespiratory, and neurocognitive symptoms.

The skin presentation is mainly a morbilliform pattern, but clinicians might also see conjunctival involvement, mucosal involvement, and “COVID toes,” painful red or purple lesions on the toes.

Treatment is usually IVIG and systemic corticosteroids, with the treatment course depending on the severity.

MIS-C was initially thought to be Kawasaki’s disease, another autoinflammatory disorder, which is related but distinct, Dr. Marathe said.

Patients with MIS-C “are usually going to have COVID-positive antibodies,” she said. But since almost everybody may have COVID antibodies, “it’s not usually a helpful test for you now. But early on, that’s what we used as helpful indicator.”

Dr. Marathe reported no relevant financial relationships.

ORLANDO – The eruption spread away from the head and her transaminase levels were “dramatic,” in the 700s, said Kalyani S. Marathe, MD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati.

Dr. Marathe, director of the division of dermatology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, reviewed this case in a presentation on pediatric dermatologic emergencies at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgery Conference, pointing out potential pitfalls and important aspects that might require swift action.

The patient was diagnosed with drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).

Facial involvement is common in pediatric cases of DRESS, but edema of the face is less common in children than adults, Dr. Marathe said.

Antiepileptic medications are the most common cause of DRESS, followed by antibiotics – most often, vancomycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, she said. But sometimes the trigger is not clear, she noted, recalling a vexing case she once saw in which IV contrast was eventually identified as the cause.

When DRESS is suspected, she said, lab work should be done during the acute eruption and after resolution. This should include CBC, liver function tests, creatinine, and urinalysis, and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) and thyroid testing.

Treatment typically includes supportive care, unless symptoms are systemic, or if there is impending liver failure, when steroids, cyclosporine, or IVIG can be used.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN): Mortality rates when these diseases overlap is 4%, Dr. Marathe said. Clues to diagnosing this other medication-induced condition include involvement of the palms and the soles of the feet; presence of the Nikolsky sign in which the top layers of the skin slip away from the lower layers when rubbed; mucosal involvement, which often precedes cutaneous involvement; and these symptoms occurring within the first 8 weeks of taking a medication, which are most commonly antibiotics and anti-epileptics.

Dr. Marathe underscored how important it is to get ophthalmology involved right away, because of the risk of vision loss. Amniotic membrane transfer to the eye at the time of diagnosis has been found to produce dramatically better outcomes, she said. The membrane has anti-inflammatory and antiscarring properties and can promote wound healing on the surface of the eye.

“I would recommend getting your ophthalmology team on board early because they have to advocate for these patients,” she said.

Corticosteroids and IVIG can improve ocular outcomes, but cyclosporine is associated with better mortality outcomes, she said. Emerging data on etanercept has also led to more use of that drug, she said.

Erythema multiforme (EM): unlike urticaria, multiforme EM can have mucosal involvement, Dr. Marathe said. Clinicians should look for three zones of color: A central duskiness, a rim of pallor, and a ring of erythema.

EM is triggered by a virus, which is usually herpes simplex virus (HSV). But she added that HSV is not always found. “So, there are certainly other triggers out there that we just haven’t identified,” she said.

If HSV is suspected, oral acyclovir is effective, she noted.

Other cases might not be as straightforward. Dr. Marathe said that during her fellowship, she saw a patient with EM that was controlled only by IVIG, so it was administered every 3 months. In that case, the trigger was never found.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): This syndrome can follow COVID-19 infection, and usually presents with 3-5 days of fever after COVID has resolved. It can include gastrointestinal, cardiorespiratory, and neurocognitive symptoms.

The skin presentation is mainly a morbilliform pattern, but clinicians might also see conjunctival involvement, mucosal involvement, and “COVID toes,” painful red or purple lesions on the toes.

Treatment is usually IVIG and systemic corticosteroids, with the treatment course depending on the severity.

MIS-C was initially thought to be Kawasaki’s disease, another autoinflammatory disorder, which is related but distinct, Dr. Marathe said.

Patients with MIS-C “are usually going to have COVID-positive antibodies,” she said. But since almost everybody may have COVID antibodies, “it’s not usually a helpful test for you now. But early on, that’s what we used as helpful indicator.”

Dr. Marathe reported no relevant financial relationships.

AT ODAC 2023

Poor sleep quality as a teen may up MS risk in adulthood

Too little sleep or poor sleep quality during the teen years can significantly increase the risk for multiple sclerosis (MS) during adulthood, new research suggests.

In a large case-control study, individuals who slept less than 7 hours a night on average during adolescence were 40% more likely to develop MS later on. The risk was even higher for those who rated their sleep quality as bad.

On the other hand, MS was significantly less common among individuals who slept longer as teens – indicating a possible protective benefit.

While sleep duration has been associated with mortality or disease risk for other conditions, sleep quality usually has little to no effect on risk, lead investigator Torbjörn Åkerstedt, PhD, sleep researcher and professor of psychology, department of neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“I hadn’t really expected that, but those results were quite strong, even stronger than sleep duration,” Dr. Åkerstedt said.

“We don’t really know why this is happening in young age, but the most suitable explanation is that the brain in still developing quite a bit, and you’re interfering with it,” he added.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Strong association

Other studies have tied sleep deprivation to increased risk for serious illness, but the link between sleep and MS risk isn’t as well studied.

Previous research by Dr. Åkerstedt showed that the risk for MS was higher among individuals who took part in shift work before the age of 20. However, the impact of sleep duration or quality among teens was unknown.

The current Swedish population-based case-control study included 2,075 patients with MS and 3,164 without the disorder. All participants were asked to recall how many hours on average they slept per night between the ages of 15 and 19 years and to rate their sleep quality during that time.

Results showed that individuals who slept fewer than 7 hours a night during their teen years were 40% more likely to have MS as adults (odds ratio [OR], 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-1.7).

Poor sleep quality increased MS risk even more (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3-1.9).

The association remained strong even after adjustment for additional sleep on weekends and breaks and excluding shift workers.

Long sleep ‘apparently good’

The researchers also conducted several sensitivity studies to rule out confounders that might bias the association, such as excluding participants who reported currently experiencing less sleep or poor sleep.

“You would expect that people who are suffering from sleep problems today would be the people who reported sleep problems during their youth,” but that didn’t happen, Dr. Åkerstedt noted.

The investigators also entered data on sleep duration and sleep quality at the same time, thinking the data would cancel each other out. However, the association remained the same.

“Quite often you see that sleep duration would eliminate the effect of sleep complaints in the prediction of disease, but here both remain significant when they are entered at the same time,” Dr. Åkerstedt said. “You get the feeling that this might mean they act together to produce results,” he added.

“One other thing that surprised me is that long sleep was apparently good,” said Dr. Åkerstedt.

The investigators have conducted several studies on sleep duration and mortality. In recent research, they found that both short sleep and long sleep predicted mortality – “and often, long sleep is a stronger predictor than short sleep,” he said.

Underestimated problem?

Commenting on the findings, Kathleen Zackowski, PhD, associate vice president of research for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society in Baltimore, noted that participants were asked to rate their own sleep quality during adolescence, a subjective report that may mean sleep quality has an even larger association with MS risk.

“That they found a result with sleep quality says to me that there probably is a bigger problem, because I don’t know if people over- or underestimate their sleep quality,” said Dr. Zackowski, who was not involved with the research.

“If we could get to that sleep quality question a little more objectively, I bet that we’d find there’s a lot more to the story,” she said.

That’s a story the researchers would like to explore, Dr. Åkerstedt reported. Designing a prospective study that more closely tracks sleeping habits during adolescence and follows individuals through adulthood could provide valuable information about how sleep quality and duration affect immune system development and MS risk, he said.

Dr. Zackowski said clinicians know that MS is not caused just by a genetic abnormality and that other environmental lifestyle factors seem to play a part.

“If we find out that sleep is one of those lifestyle factors, this is very changeable,” she added.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, the Swedish Brain Foundation, AFA Insurance, the European Aviation Safety Authority, the Tercentenary Fund of the Bank of Sweden, the Margaretha af Ugglas Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for MS Research, and NEURO Sweden. Dr. Åkerstadt has been supported by Tercentenary Fund of Bank of Sweden, AFA Insurance, and the European Aviation Safety Authority. Dr. Zackowski reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Too little sleep or poor sleep quality during the teen years can significantly increase the risk for multiple sclerosis (MS) during adulthood, new research suggests.

In a large case-control study, individuals who slept less than 7 hours a night on average during adolescence were 40% more likely to develop MS later on. The risk was even higher for those who rated their sleep quality as bad.

On the other hand, MS was significantly less common among individuals who slept longer as teens – indicating a possible protective benefit.

While sleep duration has been associated with mortality or disease risk for other conditions, sleep quality usually has little to no effect on risk, lead investigator Torbjörn Åkerstedt, PhD, sleep researcher and professor of psychology, department of neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“I hadn’t really expected that, but those results were quite strong, even stronger than sleep duration,” Dr. Åkerstedt said.

“We don’t really know why this is happening in young age, but the most suitable explanation is that the brain in still developing quite a bit, and you’re interfering with it,” he added.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Strong association

Other studies have tied sleep deprivation to increased risk for serious illness, but the link between sleep and MS risk isn’t as well studied.

Previous research by Dr. Åkerstedt showed that the risk for MS was higher among individuals who took part in shift work before the age of 20. However, the impact of sleep duration or quality among teens was unknown.

The current Swedish population-based case-control study included 2,075 patients with MS and 3,164 without the disorder. All participants were asked to recall how many hours on average they slept per night between the ages of 15 and 19 years and to rate their sleep quality during that time.

Results showed that individuals who slept fewer than 7 hours a night during their teen years were 40% more likely to have MS as adults (odds ratio [OR], 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-1.7).

Poor sleep quality increased MS risk even more (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3-1.9).

The association remained strong even after adjustment for additional sleep on weekends and breaks and excluding shift workers.

Long sleep ‘apparently good’

The researchers also conducted several sensitivity studies to rule out confounders that might bias the association, such as excluding participants who reported currently experiencing less sleep or poor sleep.

“You would expect that people who are suffering from sleep problems today would be the people who reported sleep problems during their youth,” but that didn’t happen, Dr. Åkerstedt noted.

The investigators also entered data on sleep duration and sleep quality at the same time, thinking the data would cancel each other out. However, the association remained the same.

“Quite often you see that sleep duration would eliminate the effect of sleep complaints in the prediction of disease, but here both remain significant when they are entered at the same time,” Dr. Åkerstedt said. “You get the feeling that this might mean they act together to produce results,” he added.

“One other thing that surprised me is that long sleep was apparently good,” said Dr. Åkerstedt.

The investigators have conducted several studies on sleep duration and mortality. In recent research, they found that both short sleep and long sleep predicted mortality – “and often, long sleep is a stronger predictor than short sleep,” he said.

Underestimated problem?

Commenting on the findings, Kathleen Zackowski, PhD, associate vice president of research for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society in Baltimore, noted that participants were asked to rate their own sleep quality during adolescence, a subjective report that may mean sleep quality has an even larger association with MS risk.

“That they found a result with sleep quality says to me that there probably is a bigger problem, because I don’t know if people over- or underestimate their sleep quality,” said Dr. Zackowski, who was not involved with the research.

“If we could get to that sleep quality question a little more objectively, I bet that we’d find there’s a lot more to the story,” she said.

That’s a story the researchers would like to explore, Dr. Åkerstedt reported. Designing a prospective study that more closely tracks sleeping habits during adolescence and follows individuals through adulthood could provide valuable information about how sleep quality and duration affect immune system development and MS risk, he said.

Dr. Zackowski said clinicians know that MS is not caused just by a genetic abnormality and that other environmental lifestyle factors seem to play a part.

“If we find out that sleep is one of those lifestyle factors, this is very changeable,” she added.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, the Swedish Brain Foundation, AFA Insurance, the European Aviation Safety Authority, the Tercentenary Fund of the Bank of Sweden, the Margaretha af Ugglas Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for MS Research, and NEURO Sweden. Dr. Åkerstadt has been supported by Tercentenary Fund of Bank of Sweden, AFA Insurance, and the European Aviation Safety Authority. Dr. Zackowski reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Too little sleep or poor sleep quality during the teen years can significantly increase the risk for multiple sclerosis (MS) during adulthood, new research suggests.

In a large case-control study, individuals who slept less than 7 hours a night on average during adolescence were 40% more likely to develop MS later on. The risk was even higher for those who rated their sleep quality as bad.

On the other hand, MS was significantly less common among individuals who slept longer as teens – indicating a possible protective benefit.

While sleep duration has been associated with mortality or disease risk for other conditions, sleep quality usually has little to no effect on risk, lead investigator Torbjörn Åkerstedt, PhD, sleep researcher and professor of psychology, department of neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“I hadn’t really expected that, but those results were quite strong, even stronger than sleep duration,” Dr. Åkerstedt said.

“We don’t really know why this is happening in young age, but the most suitable explanation is that the brain in still developing quite a bit, and you’re interfering with it,” he added.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Strong association

Other studies have tied sleep deprivation to increased risk for serious illness, but the link between sleep and MS risk isn’t as well studied.

Previous research by Dr. Åkerstedt showed that the risk for MS was higher among individuals who took part in shift work before the age of 20. However, the impact of sleep duration or quality among teens was unknown.

The current Swedish population-based case-control study included 2,075 patients with MS and 3,164 without the disorder. All participants were asked to recall how many hours on average they slept per night between the ages of 15 and 19 years and to rate their sleep quality during that time.

Results showed that individuals who slept fewer than 7 hours a night during their teen years were 40% more likely to have MS as adults (odds ratio [OR], 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-1.7).

Poor sleep quality increased MS risk even more (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3-1.9).

The association remained strong even after adjustment for additional sleep on weekends and breaks and excluding shift workers.

Long sleep ‘apparently good’

The researchers also conducted several sensitivity studies to rule out confounders that might bias the association, such as excluding participants who reported currently experiencing less sleep or poor sleep.

“You would expect that people who are suffering from sleep problems today would be the people who reported sleep problems during their youth,” but that didn’t happen, Dr. Åkerstedt noted.

The investigators also entered data on sleep duration and sleep quality at the same time, thinking the data would cancel each other out. However, the association remained the same.

“Quite often you see that sleep duration would eliminate the effect of sleep complaints in the prediction of disease, but here both remain significant when they are entered at the same time,” Dr. Åkerstedt said. “You get the feeling that this might mean they act together to produce results,” he added.

“One other thing that surprised me is that long sleep was apparently good,” said Dr. Åkerstedt.

The investigators have conducted several studies on sleep duration and mortality. In recent research, they found that both short sleep and long sleep predicted mortality – “and often, long sleep is a stronger predictor than short sleep,” he said.

Underestimated problem?

Commenting on the findings, Kathleen Zackowski, PhD, associate vice president of research for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society in Baltimore, noted that participants were asked to rate their own sleep quality during adolescence, a subjective report that may mean sleep quality has an even larger association with MS risk.

“That they found a result with sleep quality says to me that there probably is a bigger problem, because I don’t know if people over- or underestimate their sleep quality,” said Dr. Zackowski, who was not involved with the research.

“If we could get to that sleep quality question a little more objectively, I bet that we’d find there’s a lot more to the story,” she said.

That’s a story the researchers would like to explore, Dr. Åkerstedt reported. Designing a prospective study that more closely tracks sleeping habits during adolescence and follows individuals through adulthood could provide valuable information about how sleep quality and duration affect immune system development and MS risk, he said.

Dr. Zackowski said clinicians know that MS is not caused just by a genetic abnormality and that other environmental lifestyle factors seem to play a part.

“If we find out that sleep is one of those lifestyle factors, this is very changeable,” she added.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, the Swedish Brain Foundation, AFA Insurance, the European Aviation Safety Authority, the Tercentenary Fund of the Bank of Sweden, the Margaretha af Ugglas Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for MS Research, and NEURO Sweden. Dr. Åkerstadt has been supported by Tercentenary Fund of Bank of Sweden, AFA Insurance, and the European Aviation Safety Authority. Dr. Zackowski reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

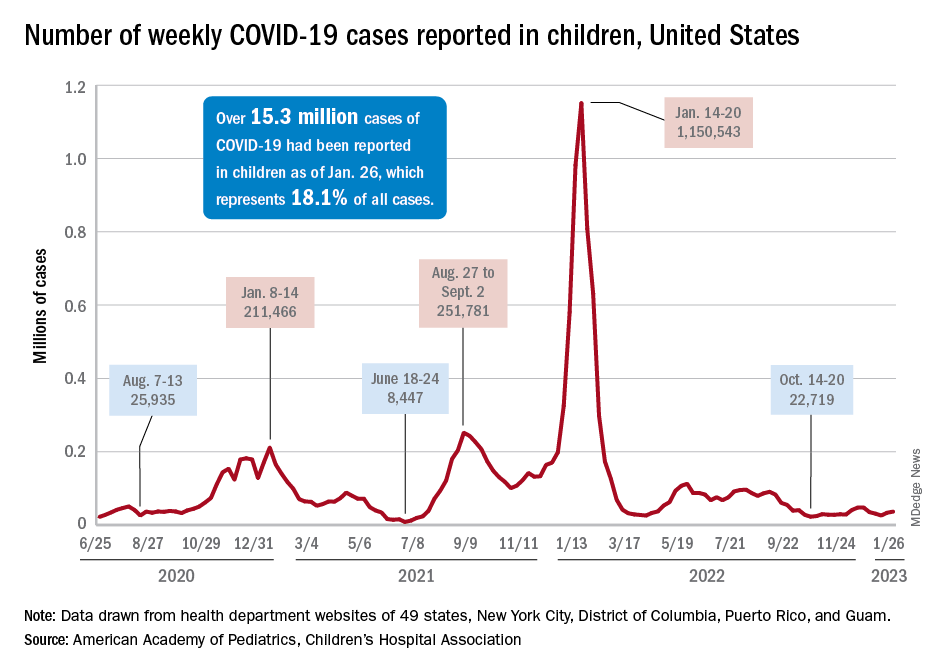

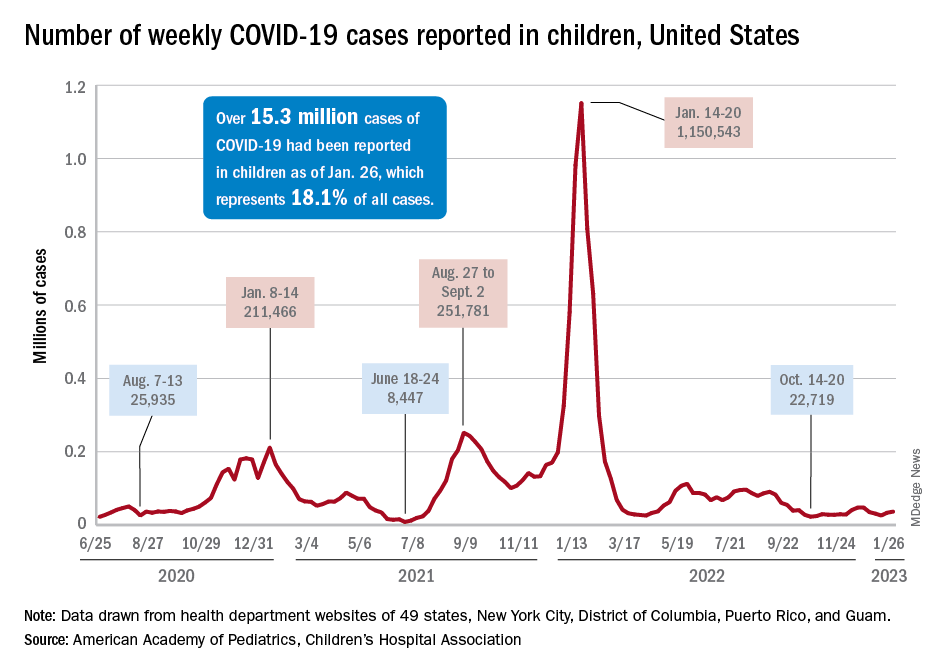

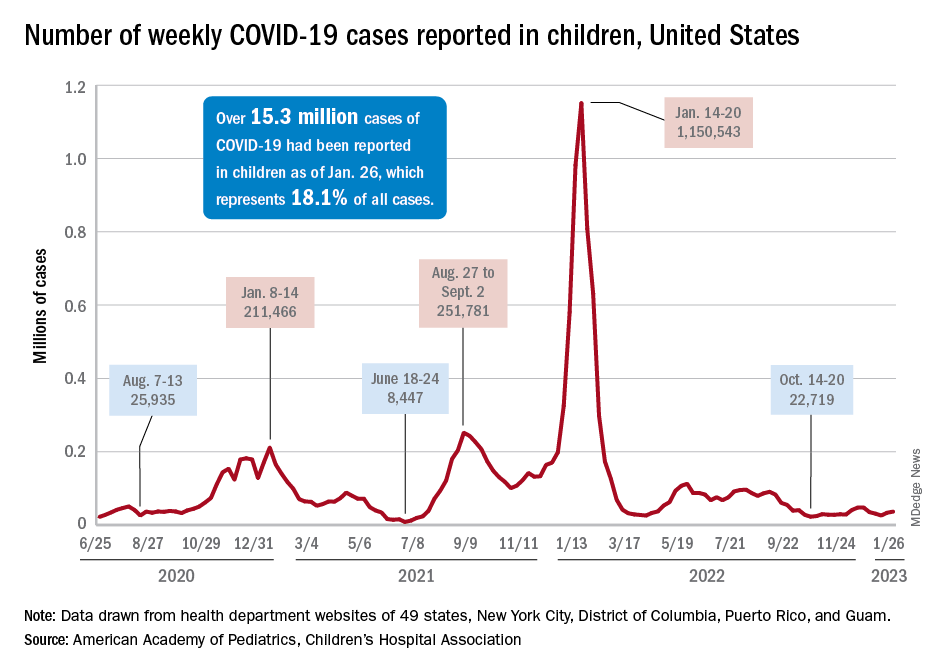

Children and COVID: Weekly cases may have doubled in early January

Although new COVID-19 cases in children, as measured by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have remained fairly steady in recent months, data from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention suggest that weekly cases took a big jump in early January.

For the most recent week covered . New cases for the first 2 weeks of the year – 31,000 for the week of Dec. 30 to Jan. 5 and 26,000 during Jan. 6-12 – were consistent with the AAP/CHA assertion that “weekly reported child cases have plateaued at an average of about 32,000 cases ... over the past 4 months.”

The CDC data, however, show that new cases doubled during the week of Jan. 1-7 to over 65,000, compared with the end of December, and stayed at that level for Jan. 8-14, and since CDC figures are subject to a 6-week reporting delay, the final numbers are likely to be even higher. The composition by age changed somewhat between the 2 weeks, though, as those aged 0-4 years went from almost half of all cases in the first week down to 40% in the second, while cases rose for children aged 5-11 and 12-15, based on data from the COVID-19 response team.

Emergency department visits for January do not show a corresponding increase. ED visits among children aged 0-11 years with COVID-19, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, declined over the course of the month, as did visits for 16- and 17-year-olds, while those aged 12-15 started the month at 1.4% and were at 1.4% on Jan. 27, with a slight dip down to 1.2% in between, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Daily hospitalizations for children aged 0-17 also declined through mid-January and did not reflect the jump in new cases.

Meanwhile, vaccinated children are still in the minority: 57% of those under age 18 have received no COVID vaccine yet, the AAP said in a separate report. Just 7.4% of children under age 2 years had received at least one dose as of Jan. 25, as had 10.1% of those aged 2-4 years, 39.6% of 5- to 11-year-olds and 71.8% of those 12-17 years old, according to the CDC, with corresponding figures for completion of the primary series at 3.5%, 5.3%, 32.5%, and 61.5%.

Although new COVID-19 cases in children, as measured by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have remained fairly steady in recent months, data from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention suggest that weekly cases took a big jump in early January.

For the most recent week covered . New cases for the first 2 weeks of the year – 31,000 for the week of Dec. 30 to Jan. 5 and 26,000 during Jan. 6-12 – were consistent with the AAP/CHA assertion that “weekly reported child cases have plateaued at an average of about 32,000 cases ... over the past 4 months.”

The CDC data, however, show that new cases doubled during the week of Jan. 1-7 to over 65,000, compared with the end of December, and stayed at that level for Jan. 8-14, and since CDC figures are subject to a 6-week reporting delay, the final numbers are likely to be even higher. The composition by age changed somewhat between the 2 weeks, though, as those aged 0-4 years went from almost half of all cases in the first week down to 40% in the second, while cases rose for children aged 5-11 and 12-15, based on data from the COVID-19 response team.

Emergency department visits for January do not show a corresponding increase. ED visits among children aged 0-11 years with COVID-19, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, declined over the course of the month, as did visits for 16- and 17-year-olds, while those aged 12-15 started the month at 1.4% and were at 1.4% on Jan. 27, with a slight dip down to 1.2% in between, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Daily hospitalizations for children aged 0-17 also declined through mid-January and did not reflect the jump in new cases.

Meanwhile, vaccinated children are still in the minority: 57% of those under age 18 have received no COVID vaccine yet, the AAP said in a separate report. Just 7.4% of children under age 2 years had received at least one dose as of Jan. 25, as had 10.1% of those aged 2-4 years, 39.6% of 5- to 11-year-olds and 71.8% of those 12-17 years old, according to the CDC, with corresponding figures for completion of the primary series at 3.5%, 5.3%, 32.5%, and 61.5%.

Although new COVID-19 cases in children, as measured by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have remained fairly steady in recent months, data from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention suggest that weekly cases took a big jump in early January.