User login

News and Views that Matter to Pediatricians

The leading independent newspaper covering news and commentary in pediatrics.

Surgeon General says 13-year-olds shouldn’t be on social media

The U.S. Surgeon General says 13 years old is too young to begin using social media.

Most social media platforms including TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook allow users to create accounts if they say they are at least 13 years old.

“I, personally, based on the data I’ve seen, believe that 13 is too early. ... It’s a time where it’s really important for us to be thoughtful about what’s going into how they think about their own self-worth and their relationships, and the skewed and often distorted environment of social media often does a disservice to many of those children,” U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, told CNN.

Research has shown that teens are susceptible to cyberbullying and serious mental health impacts from social media usage and online activity during an era when the influence of the Internet has become everywhere for young people.

According to the Pew Research Center, 95% of teens age 13 and up have a smartphone, and 97% of teens say they use the Internet daily. Among 13- and 14-year-olds, 61% say they use TikTok and 51% say they use Snapchat. Older teens ages 15-17 use those social media platforms at higher rates, with 71% saying they use TikTok and 65% using Snapchat.

“If parents can band together and say you know, as a group, we’re not going to allow our kids to use social media until 16 or 17 or 18 or whatever age they choose, that’s a much more effective strategy in making sure your kids don’t get exposed to harm early,” Dr. Murthy said.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Surgeon General says 13 years old is too young to begin using social media.

Most social media platforms including TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook allow users to create accounts if they say they are at least 13 years old.

“I, personally, based on the data I’ve seen, believe that 13 is too early. ... It’s a time where it’s really important for us to be thoughtful about what’s going into how they think about their own self-worth and their relationships, and the skewed and often distorted environment of social media often does a disservice to many of those children,” U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, told CNN.

Research has shown that teens are susceptible to cyberbullying and serious mental health impacts from social media usage and online activity during an era when the influence of the Internet has become everywhere for young people.

According to the Pew Research Center, 95% of teens age 13 and up have a smartphone, and 97% of teens say they use the Internet daily. Among 13- and 14-year-olds, 61% say they use TikTok and 51% say they use Snapchat. Older teens ages 15-17 use those social media platforms at higher rates, with 71% saying they use TikTok and 65% using Snapchat.

“If parents can band together and say you know, as a group, we’re not going to allow our kids to use social media until 16 or 17 or 18 or whatever age they choose, that’s a much more effective strategy in making sure your kids don’t get exposed to harm early,” Dr. Murthy said.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Surgeon General says 13 years old is too young to begin using social media.

Most social media platforms including TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook allow users to create accounts if they say they are at least 13 years old.

“I, personally, based on the data I’ve seen, believe that 13 is too early. ... It’s a time where it’s really important for us to be thoughtful about what’s going into how they think about their own self-worth and their relationships, and the skewed and often distorted environment of social media often does a disservice to many of those children,” U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, told CNN.

Research has shown that teens are susceptible to cyberbullying and serious mental health impacts from social media usage and online activity during an era when the influence of the Internet has become everywhere for young people.

According to the Pew Research Center, 95% of teens age 13 and up have a smartphone, and 97% of teens say they use the Internet daily. Among 13- and 14-year-olds, 61% say they use TikTok and 51% say they use Snapchat. Older teens ages 15-17 use those social media platforms at higher rates, with 71% saying they use TikTok and 65% using Snapchat.

“If parents can band together and say you know, as a group, we’re not going to allow our kids to use social media until 16 or 17 or 18 or whatever age they choose, that’s a much more effective strategy in making sure your kids don’t get exposed to harm early,” Dr. Murthy said.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Six healthy lifestyle habits linked to slowed memory decline

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

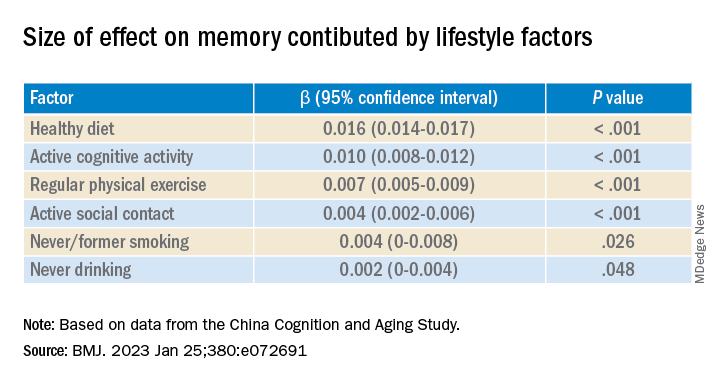

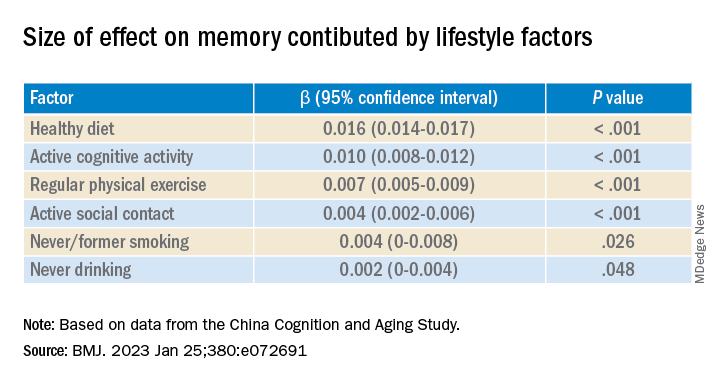

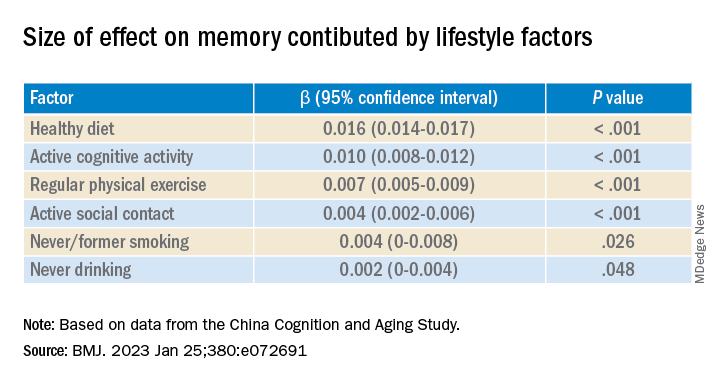

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

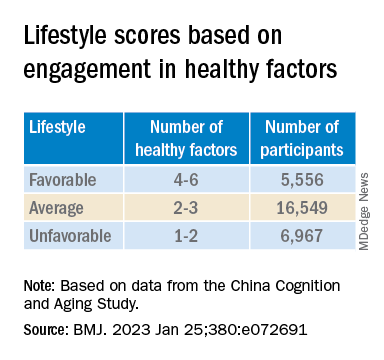

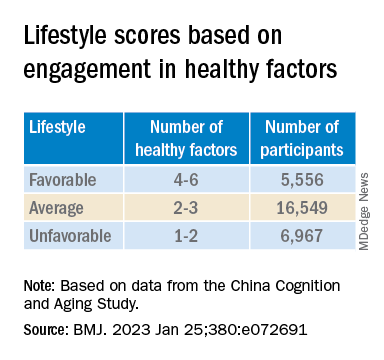

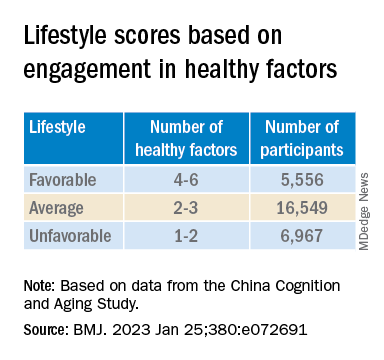

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE BMJ

Even one head injury boosts all-cause mortality risk

An analysis of more than 13,000 adult participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed a dose-response pattern in which one head injury was linked to a 66% increased risk for all-cause mortality, and two or more head injuries were associated with twice the risk in comparison with no head injuries.

These findings underscore the importance of preventing head injuries and of swift clinical intervention once a head injury occurs, lead author Holly Elser, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians should counsel patients who are at risk for falls about head injuries and ensure patients are promptly evaluated in the hospital setting if they do have a fall – especially with loss of consciousness or other symptoms, such as headache or dizziness,” Dr. Elser added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Consistent evidence

There is “pretty consistent evidence” that mortality rates are increased in the short term after head injury, predominantly among hospitalized patients, Dr. Elser noted.

“But there’s less evidence about the long-term mortality implications of head injuries and less evidence from adults living in the community,” she added.

The analysis included 13,037 participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing study involving adults aged 45-65 years who were recruited from four geographically and racially diverse U.S. communities. The mean age at baseline (1987-1989) was 54 years; 57.7% were women; and 27.9% were Black.

Study participants are followed at routine in-person visits and semiannually via telephone.

Data on head injuries came from hospital diagnostic codes and self-reports. These reports included information on the number of injuries and whether the injury required medical care and involved loss of consciousness.

During the 27-year follow-up, 18.4% of the study sample had at least one head injury. Injuries occurred more frequently among women, which may reflect the predominance of women in the study population, said Dr. Elser.

Overall, about 56% of participants died during the study period. The estimated median amount of survival time after head injury was 4.7 years.

The most common causes of death were neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disorders. Regarding specific neurologic causes of death, the researchers found that 62.2% of deaths were due to neurodegenerative disease among individuals with head injury, vs. 51.4% among those without head injury.

This, said Dr. Elser, raises the possibility of reverse causality. “If you have a neurodegenerative disorder like Alzheimer’s disease dementia or Parkinson’s disease that leads to difficulty walking, you may be more likely to fall and have a head injury. The head injury in turn may lead to increased mortality,” she noted.

However, she stressed that the data on cause-specific mortality are exploratory. “Our research motivates future studies that really examine this time-dependent relationship between neurodegenerative disease and head injuries,” Dr. Elser said.

Dose-dependent response

In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio of mortality among individuals with head injury was 2.21 (95% confidence interval, 2.09-2.34) compared with those who did not have head injury.

The association remained significant with adjustment for sociodemographic factors (HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.88-2.11) and with additional adjustment for vascular risk factors (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.81-2.03).

The findings also showed a dose-response pattern in the association of head injuries with mortality. Compared with participants who did not have head injury, the HR was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.56-1.77) for those with one head injury and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.89-2.37) for those with two or more head injuries.

“It’s not as though once you’ve had one head injury, you’ve accrued all the damage you possibly can. We see pretty clearly here that recurrent head injury further increased the rate of deaths from all causes,” said Dr. Elser.

Injury severity was determined from hospital diagnostic codes using established algorithms. Results showed that mortality rates were increased with even mild head injury.

Interestingly, the association between head injury and all-cause mortality was weaker among those whose injuries were self-reported. One possibility is that these injuries were less severe, Dr. Elser noted.

“If you have head injury that’s mild enough that you don’t need to go to the hospital, it’s probably going to confer less long-term health risks than one that’s severe enough that you needed to be examined in an acute care setting,” she said.

Results were similar by race and for sex. “Even though there were more women with head injuries, the rate of mortality associated with head injury doesn’t differ from the rate among men,” Dr. Elser reported.

However, the association was stronger among those younger than 54 years at baseline (HR, 2.26) compared with older individuals (HR, 2.0) in the model that adjusted for demographics and lifestyle factors.

This may be explained by the reference group (those without a head injury) – the mortality rate was in general higher for the older participants, said Dr. Elser. It could also be that younger adults are more likely to have severe head injuries from, for example, motor vehicle accidents or violence, she added.

These new findings underscore the importance of public health measures, such as seatbelt laws, to reduce head injuries, the investigators note.

They add that clinicians with patients at risk for head injuries may recommend steps to lessen the risk of falls, such as having access to durable medical equipment, and ensuring driver safety.

Shorter life span

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology in Port St. Lucie and past president of the Florida Society of Neurology, said the large number of participants “adds validity” to the finding that individuals with head injury are likely to have a shorter life span than those who do not suffer head trauma – and that this “was not purely by chance or from other causes.”

However, patients may not have accurately reported head injuries, in which case the rate of injury in the self-report subgroup would not reflect the actual incidence, noted Dr. Conidi, who was not involved with the research.

“In my practice, most patients have little knowledge as to the signs and symptoms of concussion and traumatic brain injury. Most think there needs to be some form of loss of consciousness to have a head injury, which is of course not true,” he said.

Dr. Conidi added that the finding of a higher incidence of death from neurodegenerative disorders supports the generally accepted consensus view that about 30% of patients with traumatic brain injury experience progression of symptoms and are at risk for early dementia.

The ARIC study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Elser and Dr. Conidi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An analysis of more than 13,000 adult participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed a dose-response pattern in which one head injury was linked to a 66% increased risk for all-cause mortality, and two or more head injuries were associated with twice the risk in comparison with no head injuries.

These findings underscore the importance of preventing head injuries and of swift clinical intervention once a head injury occurs, lead author Holly Elser, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians should counsel patients who are at risk for falls about head injuries and ensure patients are promptly evaluated in the hospital setting if they do have a fall – especially with loss of consciousness or other symptoms, such as headache or dizziness,” Dr. Elser added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Consistent evidence

There is “pretty consistent evidence” that mortality rates are increased in the short term after head injury, predominantly among hospitalized patients, Dr. Elser noted.

“But there’s less evidence about the long-term mortality implications of head injuries and less evidence from adults living in the community,” she added.

The analysis included 13,037 participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing study involving adults aged 45-65 years who were recruited from four geographically and racially diverse U.S. communities. The mean age at baseline (1987-1989) was 54 years; 57.7% were women; and 27.9% were Black.

Study participants are followed at routine in-person visits and semiannually via telephone.

Data on head injuries came from hospital diagnostic codes and self-reports. These reports included information on the number of injuries and whether the injury required medical care and involved loss of consciousness.

During the 27-year follow-up, 18.4% of the study sample had at least one head injury. Injuries occurred more frequently among women, which may reflect the predominance of women in the study population, said Dr. Elser.

Overall, about 56% of participants died during the study period. The estimated median amount of survival time after head injury was 4.7 years.

The most common causes of death were neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disorders. Regarding specific neurologic causes of death, the researchers found that 62.2% of deaths were due to neurodegenerative disease among individuals with head injury, vs. 51.4% among those without head injury.

This, said Dr. Elser, raises the possibility of reverse causality. “If you have a neurodegenerative disorder like Alzheimer’s disease dementia or Parkinson’s disease that leads to difficulty walking, you may be more likely to fall and have a head injury. The head injury in turn may lead to increased mortality,” she noted.

However, she stressed that the data on cause-specific mortality are exploratory. “Our research motivates future studies that really examine this time-dependent relationship between neurodegenerative disease and head injuries,” Dr. Elser said.

Dose-dependent response

In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio of mortality among individuals with head injury was 2.21 (95% confidence interval, 2.09-2.34) compared with those who did not have head injury.

The association remained significant with adjustment for sociodemographic factors (HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.88-2.11) and with additional adjustment for vascular risk factors (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.81-2.03).

The findings also showed a dose-response pattern in the association of head injuries with mortality. Compared with participants who did not have head injury, the HR was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.56-1.77) for those with one head injury and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.89-2.37) for those with two or more head injuries.

“It’s not as though once you’ve had one head injury, you’ve accrued all the damage you possibly can. We see pretty clearly here that recurrent head injury further increased the rate of deaths from all causes,” said Dr. Elser.

Injury severity was determined from hospital diagnostic codes using established algorithms. Results showed that mortality rates were increased with even mild head injury.

Interestingly, the association between head injury and all-cause mortality was weaker among those whose injuries were self-reported. One possibility is that these injuries were less severe, Dr. Elser noted.

“If you have head injury that’s mild enough that you don’t need to go to the hospital, it’s probably going to confer less long-term health risks than one that’s severe enough that you needed to be examined in an acute care setting,” she said.

Results were similar by race and for sex. “Even though there were more women with head injuries, the rate of mortality associated with head injury doesn’t differ from the rate among men,” Dr. Elser reported.

However, the association was stronger among those younger than 54 years at baseline (HR, 2.26) compared with older individuals (HR, 2.0) in the model that adjusted for demographics and lifestyle factors.

This may be explained by the reference group (those without a head injury) – the mortality rate was in general higher for the older participants, said Dr. Elser. It could also be that younger adults are more likely to have severe head injuries from, for example, motor vehicle accidents or violence, she added.

These new findings underscore the importance of public health measures, such as seatbelt laws, to reduce head injuries, the investigators note.

They add that clinicians with patients at risk for head injuries may recommend steps to lessen the risk of falls, such as having access to durable medical equipment, and ensuring driver safety.

Shorter life span

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology in Port St. Lucie and past president of the Florida Society of Neurology, said the large number of participants “adds validity” to the finding that individuals with head injury are likely to have a shorter life span than those who do not suffer head trauma – and that this “was not purely by chance or from other causes.”

However, patients may not have accurately reported head injuries, in which case the rate of injury in the self-report subgroup would not reflect the actual incidence, noted Dr. Conidi, who was not involved with the research.

“In my practice, most patients have little knowledge as to the signs and symptoms of concussion and traumatic brain injury. Most think there needs to be some form of loss of consciousness to have a head injury, which is of course not true,” he said.

Dr. Conidi added that the finding of a higher incidence of death from neurodegenerative disorders supports the generally accepted consensus view that about 30% of patients with traumatic brain injury experience progression of symptoms and are at risk for early dementia.

The ARIC study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Elser and Dr. Conidi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An analysis of more than 13,000 adult participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed a dose-response pattern in which one head injury was linked to a 66% increased risk for all-cause mortality, and two or more head injuries were associated with twice the risk in comparison with no head injuries.

These findings underscore the importance of preventing head injuries and of swift clinical intervention once a head injury occurs, lead author Holly Elser, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians should counsel patients who are at risk for falls about head injuries and ensure patients are promptly evaluated in the hospital setting if they do have a fall – especially with loss of consciousness or other symptoms, such as headache or dizziness,” Dr. Elser added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Consistent evidence

There is “pretty consistent evidence” that mortality rates are increased in the short term after head injury, predominantly among hospitalized patients, Dr. Elser noted.

“But there’s less evidence about the long-term mortality implications of head injuries and less evidence from adults living in the community,” she added.

The analysis included 13,037 participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing study involving adults aged 45-65 years who were recruited from four geographically and racially diverse U.S. communities. The mean age at baseline (1987-1989) was 54 years; 57.7% were women; and 27.9% were Black.

Study participants are followed at routine in-person visits and semiannually via telephone.

Data on head injuries came from hospital diagnostic codes and self-reports. These reports included information on the number of injuries and whether the injury required medical care and involved loss of consciousness.

During the 27-year follow-up, 18.4% of the study sample had at least one head injury. Injuries occurred more frequently among women, which may reflect the predominance of women in the study population, said Dr. Elser.

Overall, about 56% of participants died during the study period. The estimated median amount of survival time after head injury was 4.7 years.

The most common causes of death were neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disorders. Regarding specific neurologic causes of death, the researchers found that 62.2% of deaths were due to neurodegenerative disease among individuals with head injury, vs. 51.4% among those without head injury.

This, said Dr. Elser, raises the possibility of reverse causality. “If you have a neurodegenerative disorder like Alzheimer’s disease dementia or Parkinson’s disease that leads to difficulty walking, you may be more likely to fall and have a head injury. The head injury in turn may lead to increased mortality,” she noted.

However, she stressed that the data on cause-specific mortality are exploratory. “Our research motivates future studies that really examine this time-dependent relationship between neurodegenerative disease and head injuries,” Dr. Elser said.

Dose-dependent response

In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio of mortality among individuals with head injury was 2.21 (95% confidence interval, 2.09-2.34) compared with those who did not have head injury.

The association remained significant with adjustment for sociodemographic factors (HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.88-2.11) and with additional adjustment for vascular risk factors (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.81-2.03).

The findings also showed a dose-response pattern in the association of head injuries with mortality. Compared with participants who did not have head injury, the HR was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.56-1.77) for those with one head injury and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.89-2.37) for those with two or more head injuries.

“It’s not as though once you’ve had one head injury, you’ve accrued all the damage you possibly can. We see pretty clearly here that recurrent head injury further increased the rate of deaths from all causes,” said Dr. Elser.

Injury severity was determined from hospital diagnostic codes using established algorithms. Results showed that mortality rates were increased with even mild head injury.

Interestingly, the association between head injury and all-cause mortality was weaker among those whose injuries were self-reported. One possibility is that these injuries were less severe, Dr. Elser noted.

“If you have head injury that’s mild enough that you don’t need to go to the hospital, it’s probably going to confer less long-term health risks than one that’s severe enough that you needed to be examined in an acute care setting,” she said.

Results were similar by race and for sex. “Even though there were more women with head injuries, the rate of mortality associated with head injury doesn’t differ from the rate among men,” Dr. Elser reported.

However, the association was stronger among those younger than 54 years at baseline (HR, 2.26) compared with older individuals (HR, 2.0) in the model that adjusted for demographics and lifestyle factors.

This may be explained by the reference group (those without a head injury) – the mortality rate was in general higher for the older participants, said Dr. Elser. It could also be that younger adults are more likely to have severe head injuries from, for example, motor vehicle accidents or violence, she added.

These new findings underscore the importance of public health measures, such as seatbelt laws, to reduce head injuries, the investigators note.

They add that clinicians with patients at risk for head injuries may recommend steps to lessen the risk of falls, such as having access to durable medical equipment, and ensuring driver safety.

Shorter life span

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology in Port St. Lucie and past president of the Florida Society of Neurology, said the large number of participants “adds validity” to the finding that individuals with head injury are likely to have a shorter life span than those who do not suffer head trauma – and that this “was not purely by chance or from other causes.”

However, patients may not have accurately reported head injuries, in which case the rate of injury in the self-report subgroup would not reflect the actual incidence, noted Dr. Conidi, who was not involved with the research.

“In my practice, most patients have little knowledge as to the signs and symptoms of concussion and traumatic brain injury. Most think there needs to be some form of loss of consciousness to have a head injury, which is of course not true,” he said.

Dr. Conidi added that the finding of a higher incidence of death from neurodegenerative disorders supports the generally accepted consensus view that about 30% of patients with traumatic brain injury experience progression of symptoms and are at risk for early dementia.

The ARIC study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Elser and Dr. Conidi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Long COVID affecting more than one-third of college students, faculty

With a median age of 23 years, the study is unique for evaluating mostly healthy, young adults and for its rare look at long COVID in a university community.

The more symptoms during a bout with COVID, the greater the risk for long COVID, the researchers found. That lines up with previous studies. Also, the more vaccinations and booster shots against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, the lower the long COVID risk.

Women were more likely than men to be affected. Current or prior smoking, seeking medical care for COVID, and receiving antibody treatment also were linked to higher chances for developing long COVID.

Lead author Megan Landry, DrPH, MPH, and colleagues were already assessing students, staff, and faculty at George Washington University, Washington, who tested positive for COVID. Then they started seeing symptoms that lasted 28 days or more after their 10-day isolation period.

“We were starting to recognize that individuals ... were still having symptoms longer than the typical isolation period,” said Dr. Landry. So they developed a questionnaire to figure out the how long these symptoms last and how many people are affected by them.

The list of potential symptoms was long and included trouble thinking, fatigue, loss of smell or taste, shortness of breath, and more.

The study was published online in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Results are based on records and responses from 1,388 students, faculty, and staff from July 2021 to March 2022.

People had a median of four long COVID symptoms, about 63% were women, and 56% were non-Hispanic White. About three-quarters were students and the remainder were faculty and staff.

The finding that 36% of people with a history of COVID reported long COVID symptoms did not surprise Dr. Landry.

“Based on the literature that’s currently out there, it ranges from a 10% to an 80% prevalence of long COVID,” she said. “We kind of figured that we would fall somewhere in there.”

In contrast, that figure seemed high to Eric Topol, MD.

“That’s really high,” said Dr. Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He added most studies estimate that about 10% of people with a history of acute infection develop long COVID.

Even at 10%, which could be an underestimate, that’s a lot of affected people globally.

“At least 65 million individuals around the world have long COVID, based on a conservative estimated incidence of 10% of infected people and more than 651 million documented COVID-19 cases worldwide; the number is likely much higher due to many undocumented cases,” Dr. Topol and colleagues wrote in a long COVID review article published in Nature Reviews Microbiology.

About 30% of study participants were fully vaccinated with an initial vaccine series, 42% had received a booster dose, and 29% were not fully vaccinated at the time of their first positive test for COVID. Those who were not fully vaccinated were significantly more likely to report symptoms of long COVID.

“I know a lot of people wish they could put COVID on the back burner or brush it under the rug, but COVID is still a real thing. We need to continue supporting vaccines and boosters and make sure people are up to date. Not only for COVID, but for flu as well,” Dr. Topol said

Research continues

“Long COVID is still evolving and we continue to learn more about it every day,” Landry said. “It’s just so new and there are still a lot of unknowns. That’s why it’s important to get this information out.”

People with long COVID often have a hard time with occupational, educational, social, or personal activities, compared with before COVID, with effects that can last for more than 6 months, the authors noted.

“I think across the board, universities in general need to consider the possibility of folks on their campuses are having symptoms of long COVID,” Dr. Landry said.

Moving forward, Dr. Landry and colleagues would like to continue investigating long COVID. For example, in the current study, they did not ask about severity of symptoms or how the symptoms affected daily functioning.

“I would like to continue this and dive deeper into how disruptive their symptoms of long COVID are to their everyday studying, teaching, or their activities to keeping a university running,” Dr. Landry said.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

With a median age of 23 years, the study is unique for evaluating mostly healthy, young adults and for its rare look at long COVID in a university community.

The more symptoms during a bout with COVID, the greater the risk for long COVID, the researchers found. That lines up with previous studies. Also, the more vaccinations and booster shots against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, the lower the long COVID risk.

Women were more likely than men to be affected. Current or prior smoking, seeking medical care for COVID, and receiving antibody treatment also were linked to higher chances for developing long COVID.

Lead author Megan Landry, DrPH, MPH, and colleagues were already assessing students, staff, and faculty at George Washington University, Washington, who tested positive for COVID. Then they started seeing symptoms that lasted 28 days or more after their 10-day isolation period.

“We were starting to recognize that individuals ... were still having symptoms longer than the typical isolation period,” said Dr. Landry. So they developed a questionnaire to figure out the how long these symptoms last and how many people are affected by them.

The list of potential symptoms was long and included trouble thinking, fatigue, loss of smell or taste, shortness of breath, and more.

The study was published online in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Results are based on records and responses from 1,388 students, faculty, and staff from July 2021 to March 2022.

People had a median of four long COVID symptoms, about 63% were women, and 56% were non-Hispanic White. About three-quarters were students and the remainder were faculty and staff.

The finding that 36% of people with a history of COVID reported long COVID symptoms did not surprise Dr. Landry.

“Based on the literature that’s currently out there, it ranges from a 10% to an 80% prevalence of long COVID,” she said. “We kind of figured that we would fall somewhere in there.”

In contrast, that figure seemed high to Eric Topol, MD.

“That’s really high,” said Dr. Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He added most studies estimate that about 10% of people with a history of acute infection develop long COVID.

Even at 10%, which could be an underestimate, that’s a lot of affected people globally.

“At least 65 million individuals around the world have long COVID, based on a conservative estimated incidence of 10% of infected people and more than 651 million documented COVID-19 cases worldwide; the number is likely much higher due to many undocumented cases,” Dr. Topol and colleagues wrote in a long COVID review article published in Nature Reviews Microbiology.

About 30% of study participants were fully vaccinated with an initial vaccine series, 42% had received a booster dose, and 29% were not fully vaccinated at the time of their first positive test for COVID. Those who were not fully vaccinated were significantly more likely to report symptoms of long COVID.

“I know a lot of people wish they could put COVID on the back burner or brush it under the rug, but COVID is still a real thing. We need to continue supporting vaccines and boosters and make sure people are up to date. Not only for COVID, but for flu as well,” Dr. Topol said

Research continues

“Long COVID is still evolving and we continue to learn more about it every day,” Landry said. “It’s just so new and there are still a lot of unknowns. That’s why it’s important to get this information out.”

People with long COVID often have a hard time with occupational, educational, social, or personal activities, compared with before COVID, with effects that can last for more than 6 months, the authors noted.

“I think across the board, universities in general need to consider the possibility of folks on their campuses are having symptoms of long COVID,” Dr. Landry said.

Moving forward, Dr. Landry and colleagues would like to continue investigating long COVID. For example, in the current study, they did not ask about severity of symptoms or how the symptoms affected daily functioning.

“I would like to continue this and dive deeper into how disruptive their symptoms of long COVID are to their everyday studying, teaching, or their activities to keeping a university running,” Dr. Landry said.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

With a median age of 23 years, the study is unique for evaluating mostly healthy, young adults and for its rare look at long COVID in a university community.

The more symptoms during a bout with COVID, the greater the risk for long COVID, the researchers found. That lines up with previous studies. Also, the more vaccinations and booster shots against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, the lower the long COVID risk.

Women were more likely than men to be affected. Current or prior smoking, seeking medical care for COVID, and receiving antibody treatment also were linked to higher chances for developing long COVID.

Lead author Megan Landry, DrPH, MPH, and colleagues were already assessing students, staff, and faculty at George Washington University, Washington, who tested positive for COVID. Then they started seeing symptoms that lasted 28 days or more after their 10-day isolation period.

“We were starting to recognize that individuals ... were still having symptoms longer than the typical isolation period,” said Dr. Landry. So they developed a questionnaire to figure out the how long these symptoms last and how many people are affected by them.

The list of potential symptoms was long and included trouble thinking, fatigue, loss of smell or taste, shortness of breath, and more.

The study was published online in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Results are based on records and responses from 1,388 students, faculty, and staff from July 2021 to March 2022.

People had a median of four long COVID symptoms, about 63% were women, and 56% were non-Hispanic White. About three-quarters were students and the remainder were faculty and staff.

The finding that 36% of people with a history of COVID reported long COVID symptoms did not surprise Dr. Landry.

“Based on the literature that’s currently out there, it ranges from a 10% to an 80% prevalence of long COVID,” she said. “We kind of figured that we would fall somewhere in there.”

In contrast, that figure seemed high to Eric Topol, MD.

“That’s really high,” said Dr. Topol, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He added most studies estimate that about 10% of people with a history of acute infection develop long COVID.

Even at 10%, which could be an underestimate, that’s a lot of affected people globally.

“At least 65 million individuals around the world have long COVID, based on a conservative estimated incidence of 10% of infected people and more than 651 million documented COVID-19 cases worldwide; the number is likely much higher due to many undocumented cases,” Dr. Topol and colleagues wrote in a long COVID review article published in Nature Reviews Microbiology.

About 30% of study participants were fully vaccinated with an initial vaccine series, 42% had received a booster dose, and 29% were not fully vaccinated at the time of their first positive test for COVID. Those who were not fully vaccinated were significantly more likely to report symptoms of long COVID.

“I know a lot of people wish they could put COVID on the back burner or brush it under the rug, but COVID is still a real thing. We need to continue supporting vaccines and boosters and make sure people are up to date. Not only for COVID, but for flu as well,” Dr. Topol said

Research continues

“Long COVID is still evolving and we continue to learn more about it every day,” Landry said. “It’s just so new and there are still a lot of unknowns. That’s why it’s important to get this information out.”

People with long COVID often have a hard time with occupational, educational, social, or personal activities, compared with before COVID, with effects that can last for more than 6 months, the authors noted.

“I think across the board, universities in general need to consider the possibility of folks on their campuses are having symptoms of long COVID,” Dr. Landry said.

Moving forward, Dr. Landry and colleagues would like to continue investigating long COVID. For example, in the current study, they did not ask about severity of symptoms or how the symptoms affected daily functioning.

“I would like to continue this and dive deeper into how disruptive their symptoms of long COVID are to their everyday studying, teaching, or their activities to keeping a university running,” Dr. Landry said.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

‘Sugar tax’ prevented thousands of girls becoming obese

The introduction of the soft drinks industry levy (SDIL) – dubbed the ‘sugar tax’ – in England was followed by a drop in the number of older primary school girls succumbing to obesity, according to researchers from the Universities of Cambridge, Oxford, and Bath, with colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The study, published in PLOS Medicine, has led to calls to extend the levy to other unhealthy foods and drinks

Obesity has become a global public health problem, the researchers said. In England, around 10% of 4- to 5-year-old children and 20% of 10- to 11-year-olds were recorded as obese in 2020. Childhood obesity is associated with depression in children and the adults into which they maturate, as well as with serious health problems in later life including high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes.

In the United Kingdom, young people consume significantly more added sugars than are recommended – by late adolescence, typically 70 g of added sugar per day, more than double the recommended 30g. The team said that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are the primary sources of dietary added sugars in children, with high consumption commonly observed in more deprived areas where obesity prevalence is also highest.

Protecting children from excessive sugar

The two-tier SDIL on drinks manufacturers was implemented in April 2018 and aimed to protect children from excessive sugar consumption and tackle childhood obesity by incentivizing reformulation of SSBs in the U.K. with reduced sugar content.

To assess the effects of SDIL, the researchers used data from the National Child Measurement Programme on over 1 million children at ages 4 to 5 years (reception class) and 10 to 11 years (school year 6) in state-maintained English primary schools. The surveillance program includes annual repeat cross-sectional measurements, enabling the researchers to examine trajectories in monthly prevalence of obesity from September 2013 to November 2019, 19 months after the implementation of the SDIL.

Taking account of previous trends in obesity levels, they estimated both absolute and relative changes in obesity prevalence, both overall and by sex and deprivation, and compared obesity levels after the SDIL with predicted levels had the tax not been introduced, controlling for children’s sex and the level of deprivation of their school area.

Although they found no significant association with obesity levels in reception-age children or year-6 boys, they noted an overall absolute reduction in obesity prevalence of 1.6 percentage points (PPs) (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.1) in 10- to 11-year-old (year 6) girls. This equated to an 8% relative reduction in obesity rates compared with a counterfactual estimated from the trend prior to the SDIL announcement in March 2016, adjusted for temporal variations in obesity prevalence.

The researchers estimated that this was equivalent to preventing 5,234 cases of obesity per year in this group of year-6 girls alone.

Obesity reductions greatest in most deprived areas

Reductions were greatest in girls whose schools were in the most deprived areas, where children are known to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks. The greatest reductions in obesity were observed in the two most deprived quintiles – such that in the lowest quintile the absolute obesity prevalence reduction was 2.4 PP (95% CI, 1.6-3.2), equivalent to a 9% reduction in those living in the most deprived areas.

There are several reasons why the sugar tax did not lead to changes in levels of obesity among the younger children, the researchers said. Very young children consume fewer sugar-sweetened drinks than older children, so the soft drinks levy would have had a smaller effect. Also, fruit juices are not included in the levy, but contribute similar amounts of sugar in young children’s diets as do sugar-sweetened beverages.

Advertising may impact consumption in boys

It’s also unclear why the sugar tax might affect obesity prevalence in girls and boys differently, they said, especially since boys are higher consumers of sugar-sweetened beverages. One explanation is the possible impact of advertising – numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising than girls, both through higher levels of TV viewing and in how adverts are framed. Physical activity is often used to promote junk food and boys, compared with girls, have been shown to be more likely to believe that energy-dense junk foods depicted in adverts will boost physical performance, and so are more likely to choose energy-dense, nutrient-poor products following celebrity endorsements.

Tax ‘led to positive health impacts’

“Our findings suggest that the U.K. SDIL led to positive health impacts in the form of reduced obesity levels in girls aged 10-11 years,” the authors said. However: “Additional strategies beyond SSB taxation will be needed to reduce obesity prevalence overall, and particularly in older boys and younger children.”

Dr. Nina Rogers from the MRC Epidemiology Unit at Cambridge (England), who led the study, said: “We urgently need to find ways to tackle the increasing numbers of children living with obesity, otherwise we risk our children growing up to face significant health problems. That was one reason why the U.K.’s SDIL was introduced, and the evidence so far is promising. We’ve shown for the first time that it is likely to have helped prevent thousands of children each year becoming obese.

“It isn’t a straightforward picture, though, as it was mainly older girls who benefited. But the fact that we saw the biggest difference among girls from areas of high deprivation is important and is a step towards reducing the health inequalities they face.”

Although the researchers found an association rather than a causal link, this study adds to previous findings that the levy was associated with a substantial reduction in the amount of sugar in soft drinks.

Senior author Professor Jean Adams from the MRC Epidemiology Unit said: “We know that consuming too many sugary drinks contributes to obesity and that the U.K. soft drinks levy led to a drop in the amount of sugar in soft drinks available in the U.K., so it makes sense that we also see a drop in cases of obesity, although we only found this in girls. Children from more deprived backgrounds tend to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks, and it was among girls in this group that we saw the biggest change.”

Tom Sanders, professor emeritus of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, said: “The claim that the soft drink levy might have prevented 5,000 children from becoming obese is speculative because it is based on an association not actual measurements of consumption.”

He added that: “As well as continuing to discourage the consumption of sugar sweetened beverages and sweets, wider recognition should be given to foods such as biscuits [and] deep-fried foods (crisps, corn snacks, chips) that make [a] bigger contribution to excess calorie intake in children. Tackling poverty, however, is probably [the] best way to improve the diets of socially deprived children.”

Government ‘should learn from this success’

Asked to comment by this news organization, Katharine Jenner, director of the Obesity Health Alliance, said: “Government should be heartened that their soft drinks policy is already improving the health of young girls, regardless of where they live. The government should learn from this success, especially when compared with the many unsuccessful attempts to persuade industry to change their products voluntarily. They must now press ahead with policies that make it easier for everyone to eat a healthier diet, including extending the soft drinks industry levy to include other less healthy foods and drinks and measures to take junk food out of the spotlight.

“The research notes that numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising content than girls, negating the impact of the soft drinks levy [so] we need restriction on junk food marketing now, to put healthy food back in the spotlight.”

The research was supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research and the Medical Research Council.

A version of this article originally appeared on MedscapeUK.

The introduction of the soft drinks industry levy (SDIL) – dubbed the ‘sugar tax’ – in England was followed by a drop in the number of older primary school girls succumbing to obesity, according to researchers from the Universities of Cambridge, Oxford, and Bath, with colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The study, published in PLOS Medicine, has led to calls to extend the levy to other unhealthy foods and drinks

Obesity has become a global public health problem, the researchers said. In England, around 10% of 4- to 5-year-old children and 20% of 10- to 11-year-olds were recorded as obese in 2020. Childhood obesity is associated with depression in children and the adults into which they maturate, as well as with serious health problems in later life including high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes.

In the United Kingdom, young people consume significantly more added sugars than are recommended – by late adolescence, typically 70 g of added sugar per day, more than double the recommended 30g. The team said that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are the primary sources of dietary added sugars in children, with high consumption commonly observed in more deprived areas where obesity prevalence is also highest.

Protecting children from excessive sugar

The two-tier SDIL on drinks manufacturers was implemented in April 2018 and aimed to protect children from excessive sugar consumption and tackle childhood obesity by incentivizing reformulation of SSBs in the U.K. with reduced sugar content.

To assess the effects of SDIL, the researchers used data from the National Child Measurement Programme on over 1 million children at ages 4 to 5 years (reception class) and 10 to 11 years (school year 6) in state-maintained English primary schools. The surveillance program includes annual repeat cross-sectional measurements, enabling the researchers to examine trajectories in monthly prevalence of obesity from September 2013 to November 2019, 19 months after the implementation of the SDIL.

Taking account of previous trends in obesity levels, they estimated both absolute and relative changes in obesity prevalence, both overall and by sex and deprivation, and compared obesity levels after the SDIL with predicted levels had the tax not been introduced, controlling for children’s sex and the level of deprivation of their school area.

Although they found no significant association with obesity levels in reception-age children or year-6 boys, they noted an overall absolute reduction in obesity prevalence of 1.6 percentage points (PPs) (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.1) in 10- to 11-year-old (year 6) girls. This equated to an 8% relative reduction in obesity rates compared with a counterfactual estimated from the trend prior to the SDIL announcement in March 2016, adjusted for temporal variations in obesity prevalence.

The researchers estimated that this was equivalent to preventing 5,234 cases of obesity per year in this group of year-6 girls alone.

Obesity reductions greatest in most deprived areas

Reductions were greatest in girls whose schools were in the most deprived areas, where children are known to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks. The greatest reductions in obesity were observed in the two most deprived quintiles – such that in the lowest quintile the absolute obesity prevalence reduction was 2.4 PP (95% CI, 1.6-3.2), equivalent to a 9% reduction in those living in the most deprived areas.

There are several reasons why the sugar tax did not lead to changes in levels of obesity among the younger children, the researchers said. Very young children consume fewer sugar-sweetened drinks than older children, so the soft drinks levy would have had a smaller effect. Also, fruit juices are not included in the levy, but contribute similar amounts of sugar in young children’s diets as do sugar-sweetened beverages.

Advertising may impact consumption in boys

It’s also unclear why the sugar tax might affect obesity prevalence in girls and boys differently, they said, especially since boys are higher consumers of sugar-sweetened beverages. One explanation is the possible impact of advertising – numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising than girls, both through higher levels of TV viewing and in how adverts are framed. Physical activity is often used to promote junk food and boys, compared with girls, have been shown to be more likely to believe that energy-dense junk foods depicted in adverts will boost physical performance, and so are more likely to choose energy-dense, nutrient-poor products following celebrity endorsements.

Tax ‘led to positive health impacts’

“Our findings suggest that the U.K. SDIL led to positive health impacts in the form of reduced obesity levels in girls aged 10-11 years,” the authors said. However: “Additional strategies beyond SSB taxation will be needed to reduce obesity prevalence overall, and particularly in older boys and younger children.”

Dr. Nina Rogers from the MRC Epidemiology Unit at Cambridge (England), who led the study, said: “We urgently need to find ways to tackle the increasing numbers of children living with obesity, otherwise we risk our children growing up to face significant health problems. That was one reason why the U.K.’s SDIL was introduced, and the evidence so far is promising. We’ve shown for the first time that it is likely to have helped prevent thousands of children each year becoming obese.

“It isn’t a straightforward picture, though, as it was mainly older girls who benefited. But the fact that we saw the biggest difference among girls from areas of high deprivation is important and is a step towards reducing the health inequalities they face.”

Although the researchers found an association rather than a causal link, this study adds to previous findings that the levy was associated with a substantial reduction in the amount of sugar in soft drinks.

Senior author Professor Jean Adams from the MRC Epidemiology Unit said: “We know that consuming too many sugary drinks contributes to obesity and that the U.K. soft drinks levy led to a drop in the amount of sugar in soft drinks available in the U.K., so it makes sense that we also see a drop in cases of obesity, although we only found this in girls. Children from more deprived backgrounds tend to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks, and it was among girls in this group that we saw the biggest change.”

Tom Sanders, professor emeritus of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, said: “The claim that the soft drink levy might have prevented 5,000 children from becoming obese is speculative because it is based on an association not actual measurements of consumption.”

He added that: “As well as continuing to discourage the consumption of sugar sweetened beverages and sweets, wider recognition should be given to foods such as biscuits [and] deep-fried foods (crisps, corn snacks, chips) that make [a] bigger contribution to excess calorie intake in children. Tackling poverty, however, is probably [the] best way to improve the diets of socially deprived children.”

Government ‘should learn from this success’

Asked to comment by this news organization, Katharine Jenner, director of the Obesity Health Alliance, said: “Government should be heartened that their soft drinks policy is already improving the health of young girls, regardless of where they live. The government should learn from this success, especially when compared with the many unsuccessful attempts to persuade industry to change their products voluntarily. They must now press ahead with policies that make it easier for everyone to eat a healthier diet, including extending the soft drinks industry levy to include other less healthy foods and drinks and measures to take junk food out of the spotlight.

“The research notes that numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising content than girls, negating the impact of the soft drinks levy [so] we need restriction on junk food marketing now, to put healthy food back in the spotlight.”

The research was supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research and the Medical Research Council.

A version of this article originally appeared on MedscapeUK.

The introduction of the soft drinks industry levy (SDIL) – dubbed the ‘sugar tax’ – in England was followed by a drop in the number of older primary school girls succumbing to obesity, according to researchers from the Universities of Cambridge, Oxford, and Bath, with colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The study, published in PLOS Medicine, has led to calls to extend the levy to other unhealthy foods and drinks

Obesity has become a global public health problem, the researchers said. In England, around 10% of 4- to 5-year-old children and 20% of 10- to 11-year-olds were recorded as obese in 2020. Childhood obesity is associated with depression in children and the adults into which they maturate, as well as with serious health problems in later life including high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes.

In the United Kingdom, young people consume significantly more added sugars than are recommended – by late adolescence, typically 70 g of added sugar per day, more than double the recommended 30g. The team said that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are the primary sources of dietary added sugars in children, with high consumption commonly observed in more deprived areas where obesity prevalence is also highest.

Protecting children from excessive sugar