User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

New RSV vaccine will cut hospitalizations, study shows

, according to research presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“With RSV maternal vaccination that is associated with clinical efficacy of 69% against severe RSV disease at 6 months, we estimated that up to 200,000 cases can be averted, and that is associated with almost $800 million in total,” presenting author Amy W. Law, PharmD, director of global value and evidence at Pfizer, pointed out during a news briefing.

“RSV is associated with a significant burden in the U.S. and this newly approved and recommended maternal RSV vaccine can have substantial impact in easing some of that burden,” Dr. Law explained.

This study is “particularly timely as we head into RSV peak season,” said briefing moderator Natasha Halasa, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The challenge, said Dr. Halasa, is that uptake of maternal vaccines and vaccines in general is “not optimal,” making increased awareness of this new maternal RSV vaccine important.

Strong efficacy data

Most children are infected with RSV at least once by the time they reach age 2 years. Very young children are at particular risk of severe complications, such as pneumonia or bronchitis.

As reported previously by this news organization, in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine had an almost 82% efficacy against severe RSV infection in infants from birth through the first 90 days of life.

The vaccine also had a 69% efficacy against severe disease through the first 6 months of life. As part of the trial, a total of 7,400 women received a single dose of the vaccine in the late second or third trimester of their pregnancy. There were no signs of safety issues for the mothers or infants.

Based on the results, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the vaccine, known as Abrysvo, in August, to be given between weeks 32 and 36 of pregnancy.

New modeling study

Dr. Law and colleagues modeled the potential public health impact – both clinical and economic – of the maternal RSV vaccine among the population of all pregnant women and their infants born during a 12-month period in the United States. The model focused on severe RSV disease in babies that required medical attention.

According to their model, without widespread use of the maternal RSV vaccine, 48,246 hospitalizations, 144,495 emergency department encounters, and 399,313 outpatient clinic visits related to RSV are projected to occur annually among the U.S. birth cohort of 3.7 million infants younger than 12 months.

With widespread use of the vaccine, annual hospitalizations resulting from infant RSV would fall by 51%, emergency department encounters would decline by 32%, and outpatient clinic visits by 32% – corresponding to a decrease in direct medical costs of about $692 million and indirect nonmedical costs of roughly $110 million.

Dr. Law highlighted two important caveats to the data. “The protections are based on the year-round administration of the vaccine to pregnant women at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestational age, and this is also assuming 100% uptake. Of course, in reality, that most likely is not the case,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa noted that the peak age for severe RSV illness is 3 months and it’s tough to identify infants at highest risk for severe RSV.

Nearly 80% of infants with RSV who are hospitalized do not have an underlying medical condition, “so we don’t even know who those high-risk infants are. That’s why having this vaccine is so exciting,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa said it’s also important to note that infants with severe RSV typically make not just one but multiple visits to the clinic or emergency department, leading to missed days of work for the parent, not to mention the “emotional burden of having your otherwise healthy newborn or young infant in the hospital.”

In addition to Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine, the FDA in July approved AstraZeneca’s monoclonal antibody nirsevimab (Beyfortus) for the prevention of RSV in neonates and infants entering their first RSV season, and in children up to 24 months who remain vulnerable to severe RSV disease through their second RSV season.

The study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Law is employed by Pfizer. Dr. Halasa has received grant and research support from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to research presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“With RSV maternal vaccination that is associated with clinical efficacy of 69% against severe RSV disease at 6 months, we estimated that up to 200,000 cases can be averted, and that is associated with almost $800 million in total,” presenting author Amy W. Law, PharmD, director of global value and evidence at Pfizer, pointed out during a news briefing.

“RSV is associated with a significant burden in the U.S. and this newly approved and recommended maternal RSV vaccine can have substantial impact in easing some of that burden,” Dr. Law explained.

This study is “particularly timely as we head into RSV peak season,” said briefing moderator Natasha Halasa, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The challenge, said Dr. Halasa, is that uptake of maternal vaccines and vaccines in general is “not optimal,” making increased awareness of this new maternal RSV vaccine important.

Strong efficacy data

Most children are infected with RSV at least once by the time they reach age 2 years. Very young children are at particular risk of severe complications, such as pneumonia or bronchitis.

As reported previously by this news organization, in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine had an almost 82% efficacy against severe RSV infection in infants from birth through the first 90 days of life.

The vaccine also had a 69% efficacy against severe disease through the first 6 months of life. As part of the trial, a total of 7,400 women received a single dose of the vaccine in the late second or third trimester of their pregnancy. There were no signs of safety issues for the mothers or infants.

Based on the results, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the vaccine, known as Abrysvo, in August, to be given between weeks 32 and 36 of pregnancy.

New modeling study

Dr. Law and colleagues modeled the potential public health impact – both clinical and economic – of the maternal RSV vaccine among the population of all pregnant women and their infants born during a 12-month period in the United States. The model focused on severe RSV disease in babies that required medical attention.

According to their model, without widespread use of the maternal RSV vaccine, 48,246 hospitalizations, 144,495 emergency department encounters, and 399,313 outpatient clinic visits related to RSV are projected to occur annually among the U.S. birth cohort of 3.7 million infants younger than 12 months.

With widespread use of the vaccine, annual hospitalizations resulting from infant RSV would fall by 51%, emergency department encounters would decline by 32%, and outpatient clinic visits by 32% – corresponding to a decrease in direct medical costs of about $692 million and indirect nonmedical costs of roughly $110 million.

Dr. Law highlighted two important caveats to the data. “The protections are based on the year-round administration of the vaccine to pregnant women at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestational age, and this is also assuming 100% uptake. Of course, in reality, that most likely is not the case,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa noted that the peak age for severe RSV illness is 3 months and it’s tough to identify infants at highest risk for severe RSV.

Nearly 80% of infants with RSV who are hospitalized do not have an underlying medical condition, “so we don’t even know who those high-risk infants are. That’s why having this vaccine is so exciting,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa said it’s also important to note that infants with severe RSV typically make not just one but multiple visits to the clinic or emergency department, leading to missed days of work for the parent, not to mention the “emotional burden of having your otherwise healthy newborn or young infant in the hospital.”

In addition to Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine, the FDA in July approved AstraZeneca’s monoclonal antibody nirsevimab (Beyfortus) for the prevention of RSV in neonates and infants entering their first RSV season, and in children up to 24 months who remain vulnerable to severe RSV disease through their second RSV season.

The study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Law is employed by Pfizer. Dr. Halasa has received grant and research support from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to research presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“With RSV maternal vaccination that is associated with clinical efficacy of 69% against severe RSV disease at 6 months, we estimated that up to 200,000 cases can be averted, and that is associated with almost $800 million in total,” presenting author Amy W. Law, PharmD, director of global value and evidence at Pfizer, pointed out during a news briefing.

“RSV is associated with a significant burden in the U.S. and this newly approved and recommended maternal RSV vaccine can have substantial impact in easing some of that burden,” Dr. Law explained.

This study is “particularly timely as we head into RSV peak season,” said briefing moderator Natasha Halasa, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

The challenge, said Dr. Halasa, is that uptake of maternal vaccines and vaccines in general is “not optimal,” making increased awareness of this new maternal RSV vaccine important.

Strong efficacy data

Most children are infected with RSV at least once by the time they reach age 2 years. Very young children are at particular risk of severe complications, such as pneumonia or bronchitis.

As reported previously by this news organization, in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine had an almost 82% efficacy against severe RSV infection in infants from birth through the first 90 days of life.

The vaccine also had a 69% efficacy against severe disease through the first 6 months of life. As part of the trial, a total of 7,400 women received a single dose of the vaccine in the late second or third trimester of their pregnancy. There were no signs of safety issues for the mothers or infants.

Based on the results, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the vaccine, known as Abrysvo, in August, to be given between weeks 32 and 36 of pregnancy.

New modeling study

Dr. Law and colleagues modeled the potential public health impact – both clinical and economic – of the maternal RSV vaccine among the population of all pregnant women and their infants born during a 12-month period in the United States. The model focused on severe RSV disease in babies that required medical attention.

According to their model, without widespread use of the maternal RSV vaccine, 48,246 hospitalizations, 144,495 emergency department encounters, and 399,313 outpatient clinic visits related to RSV are projected to occur annually among the U.S. birth cohort of 3.7 million infants younger than 12 months.

With widespread use of the vaccine, annual hospitalizations resulting from infant RSV would fall by 51%, emergency department encounters would decline by 32%, and outpatient clinic visits by 32% – corresponding to a decrease in direct medical costs of about $692 million and indirect nonmedical costs of roughly $110 million.

Dr. Law highlighted two important caveats to the data. “The protections are based on the year-round administration of the vaccine to pregnant women at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestational age, and this is also assuming 100% uptake. Of course, in reality, that most likely is not the case,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa noted that the peak age for severe RSV illness is 3 months and it’s tough to identify infants at highest risk for severe RSV.

Nearly 80% of infants with RSV who are hospitalized do not have an underlying medical condition, “so we don’t even know who those high-risk infants are. That’s why having this vaccine is so exciting,” she told the briefing.

Dr. Halasa said it’s also important to note that infants with severe RSV typically make not just one but multiple visits to the clinic or emergency department, leading to missed days of work for the parent, not to mention the “emotional burden of having your otherwise healthy newborn or young infant in the hospital.”

In addition to Pfizer’s maternal RSV vaccine, the FDA in July approved AstraZeneca’s monoclonal antibody nirsevimab (Beyfortus) for the prevention of RSV in neonates and infants entering their first RSV season, and in children up to 24 months who remain vulnerable to severe RSV disease through their second RSV season.

The study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Law is employed by Pfizer. Dr. Halasa has received grant and research support from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM IDWEEK 2023

Have you asked your patients: What is your ideal outpatient gynecology experience?

There has been increasing awareness of a need for creating a more patient-centered experience with outpatient gynecology; however, very little data exist about what interventions are important to patients. Given social media’s ease of use and ability for widespread access to a diverse group of users, it has the potential to be a powerful tool for qualitative research questions without the difficulties of cost, transportation, transcription, etc. required of a focus group. Crowdsourced public opinion also has the advantage of producing qualitative metrics in the form of “likes” that, at scale, can provide a reliable measure of public support or engagement for a particular concept.1 Particularly for topics that are controversial or novel, X (formerly Twitter, and referred to as Twitter intermittently throughout this article based on the time the study was conducted), with 300 million monthly users,2 has become a popular tool for general and health care ̶ focused content and sentiment analysis.3,4 This study presents a qualitative analysis of themes from a crowdsourced request on Twitter to design the ideal outpatient gynecologic experience that subsequently went “viral”.5,6

When asked to design the optimized outpatient gynecology experience, social media users expressed:

- hospitality, comfort, and pain control as frequent themes

- preserving privacy and acknowledgement of voluntary nulliparity as frequent themes

- a desire for diverse imagery and representation related to race, LGBTQIA+ themes, age, and weight/body type within the office setting

- a call for a sense of psychological safety within gynecology

Why the need for our research question on patient-centered gyn care

While the body of literature on patient-centered health care has grown rapidly in recent years, a patient-centered outpatient gynecology experience has not yet been described in the medical literature.

Patient-centered office design, driven by cultural sensitivity, has been shown in other studies to be both appreciated by established patients and a viable business strategy to attract new patients.7 Topics such as pain control, trauma-informed care in gynecologyclinics,8 and diverse representation in patient materials and illustrations9 have been popular topics in medicine and in the lay press. Our primary aim in our research was to utilize feedback from the question posed to quantify and rank patient-centered interventions in a gynecology office. These themes and others that emerged in our analysis were used to suggest b

What we asked social media users. The survey query to social media users, “I have the opportunity to design my office from scratch. I’m asking women: How would you design/optimize a visit to the gynecologist’s office?” was crowd-sourced via Twitter on December 5, 2021.5 Given a robust response to the query, it provided an opportunity for a qualitative research study exploring social media users’ perspectives on optimizing outpatient gynecologic care, although the original question was not planned for research utilization.

What we found

By December 27, 2021, the original tweet had earned 9,411 likes; 2,143 retweets; and 3,400 replies. Of this group, we analyzed 131 tweets, all of which had 100 or greater likes on Twitter at the time of the review. The majority of analyzed tweets earned between 100 ̶ 500 likes (75/131; 57.3%), while 22.9% (30/131) had 501 ̶ 1,000 likes, 11.5% (15/131) had >2,000 likes, and 8.4% (11/131) had 1,001 ̶ 1,999 likes.

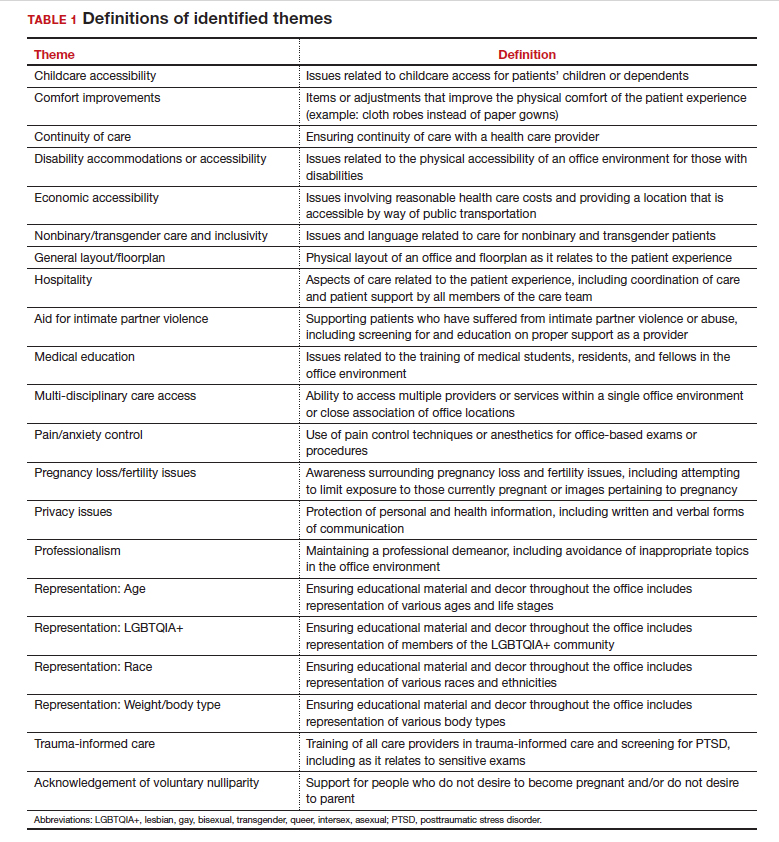

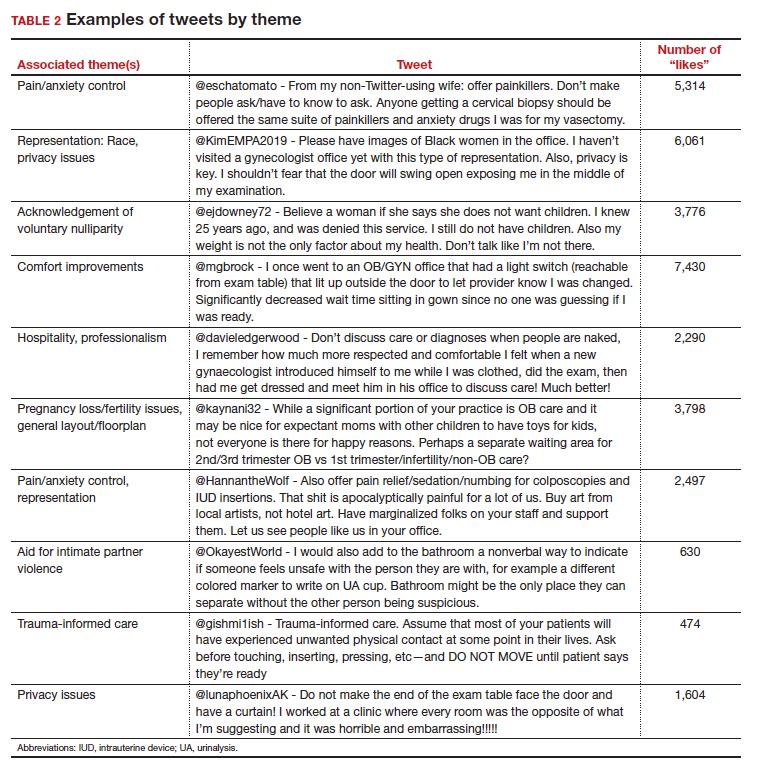

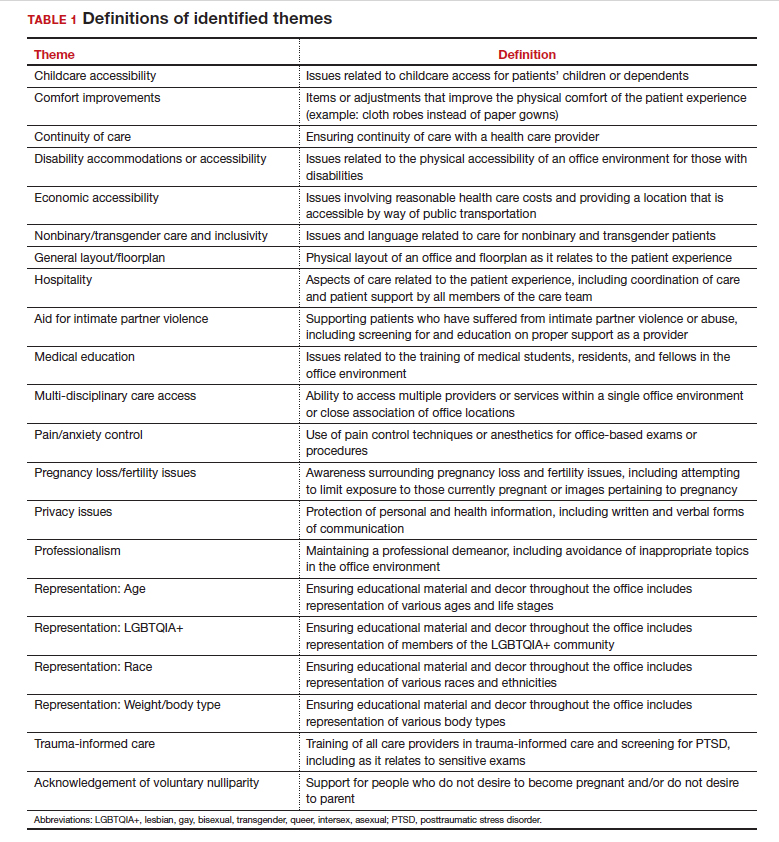

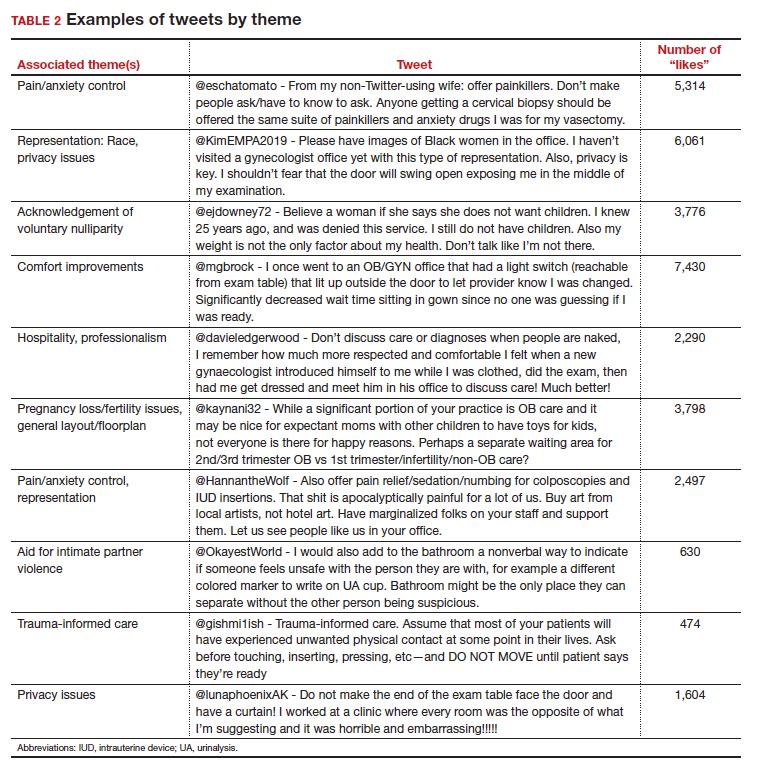

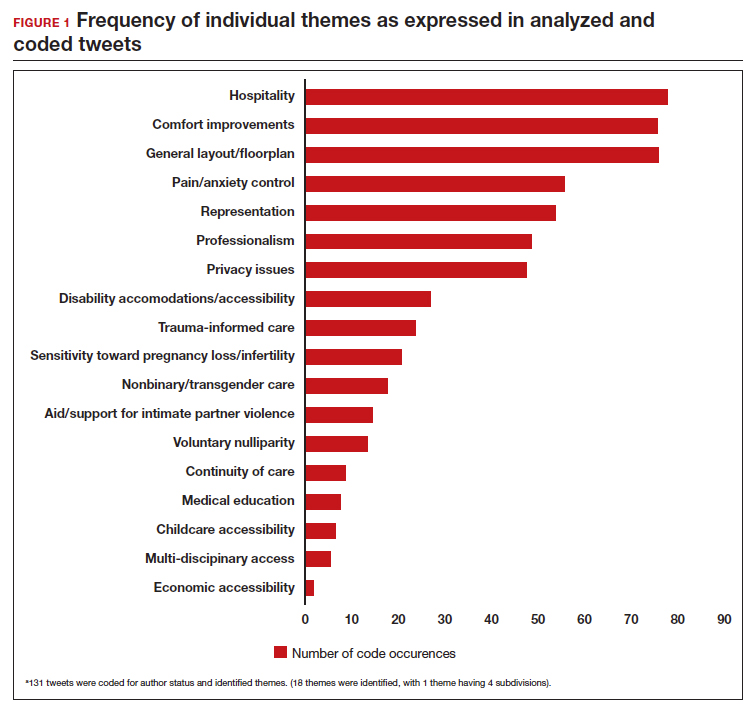

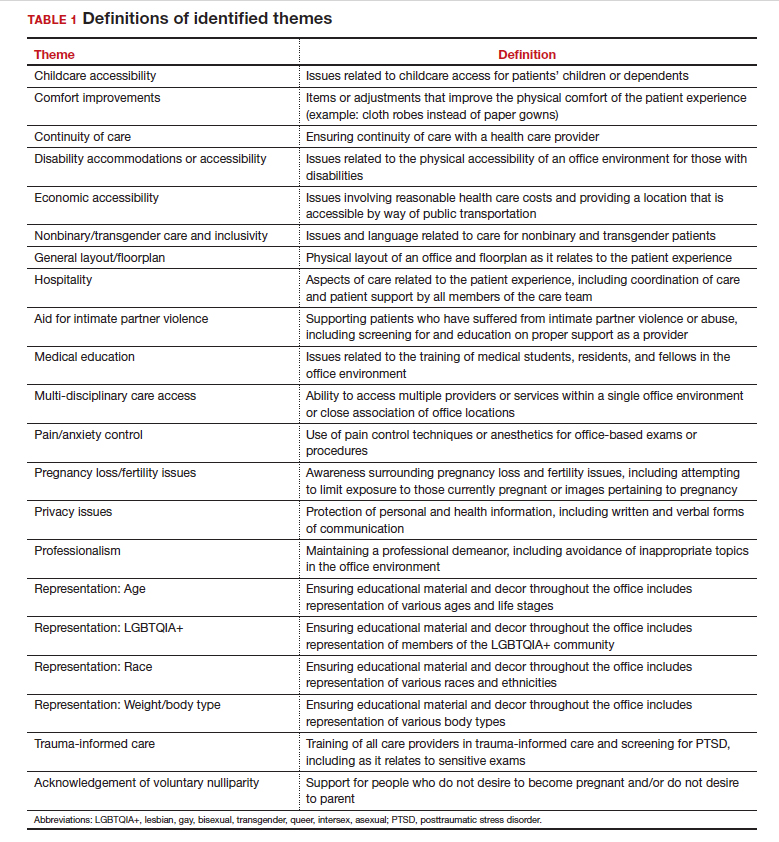

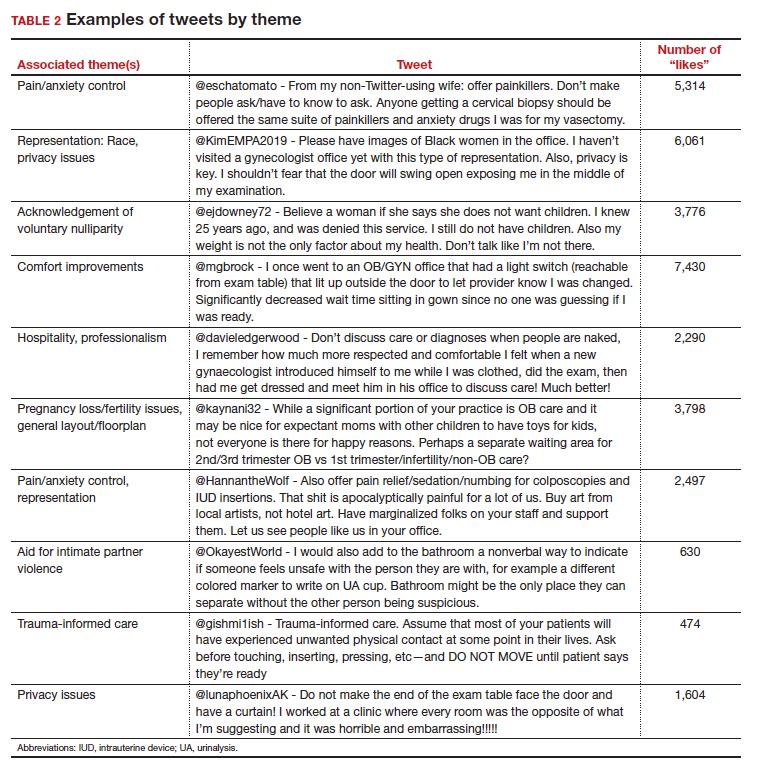

Identified themes within the tweets analyzed included: medical education, comfort improvements, continuity of care, disability accommodations/accessibility, economic accessibility, nonbinary/transgender care and inclusivity, general layout/floorplan, hospitality, aid for intimate partner violence, childcare accessibility, multi-disciplinary care access, pain/anxiety control, sensitivity toward pregnancy loss/fertility issues, privacy issues, professionalism, representation (subdivided into race, LGBTQIA+, age, and weight/body type), trauma-informed care, and acknowledgement of voluntary nulliparity/support for reproductive choices (TABLE 1). TABLE 2 lists examples of popular tweets by selected themes.

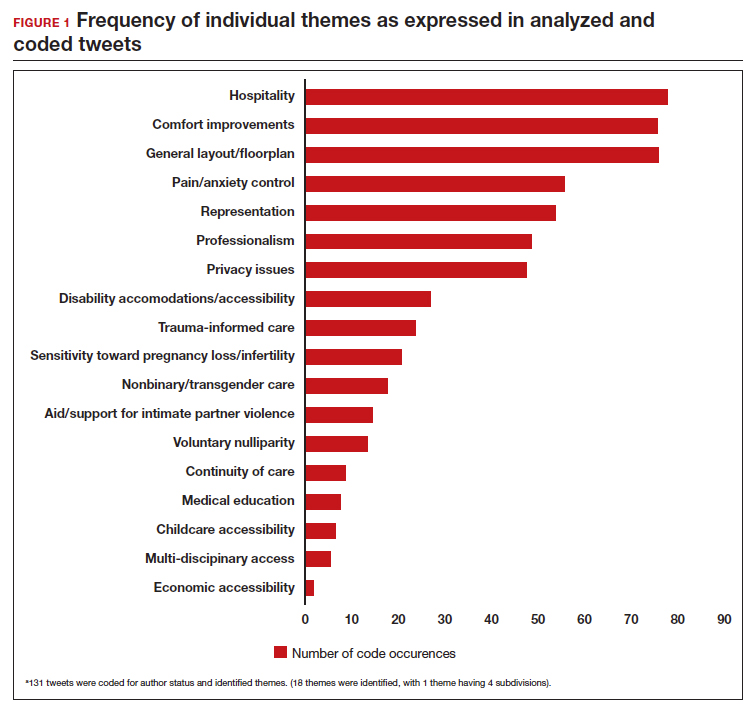

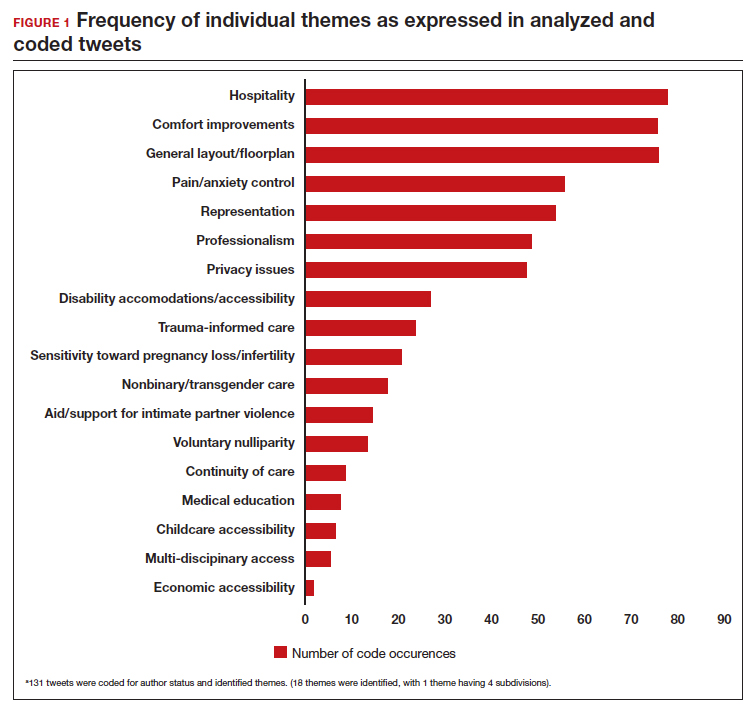

Frequent themes. The most frequently occurring themes within the 131 analyzed tweets (FIGURE 1) were:

- hospitality (77 occurrences)

- comfort improvements (75 occurrences)

- general layout/floorplan (75 occurrences)

- pain/anxiety control (55 occurrences)

- representation (53 occurrences).

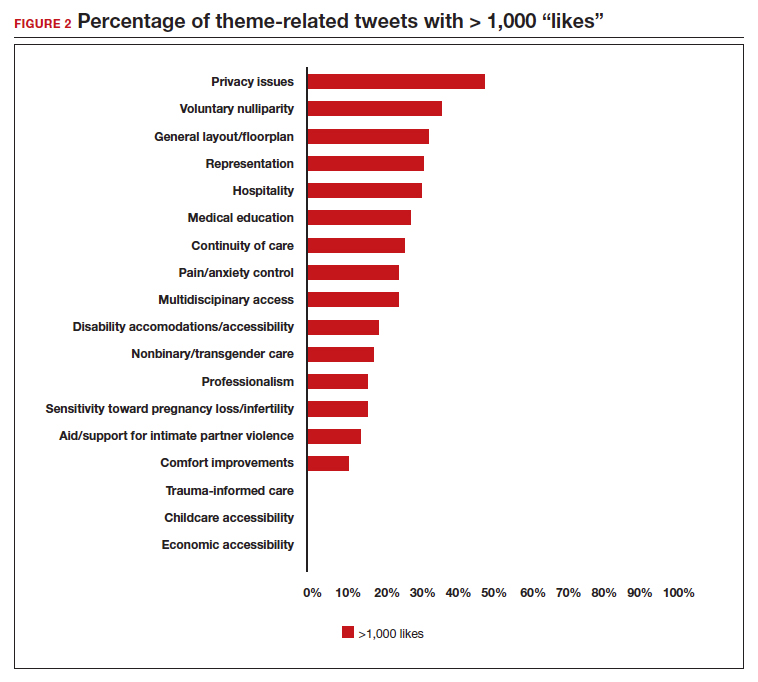

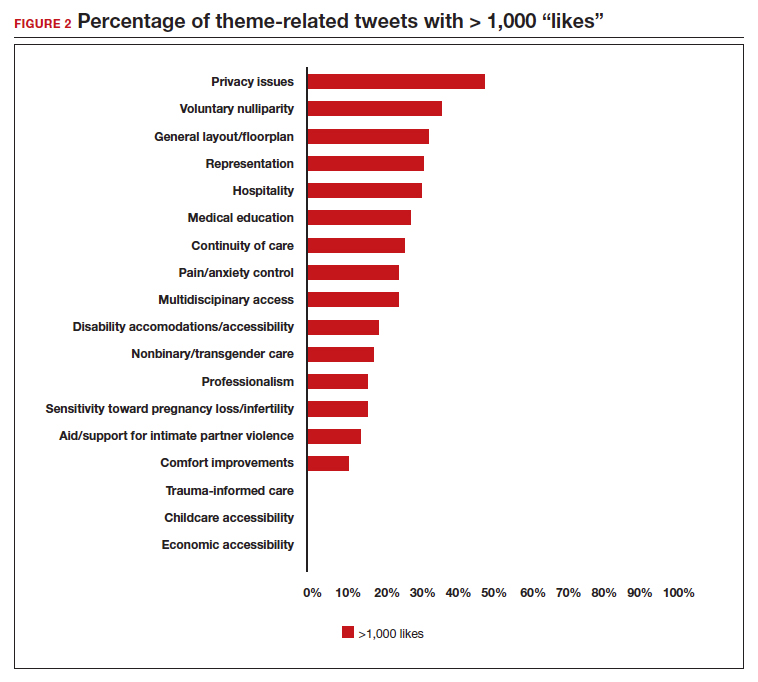

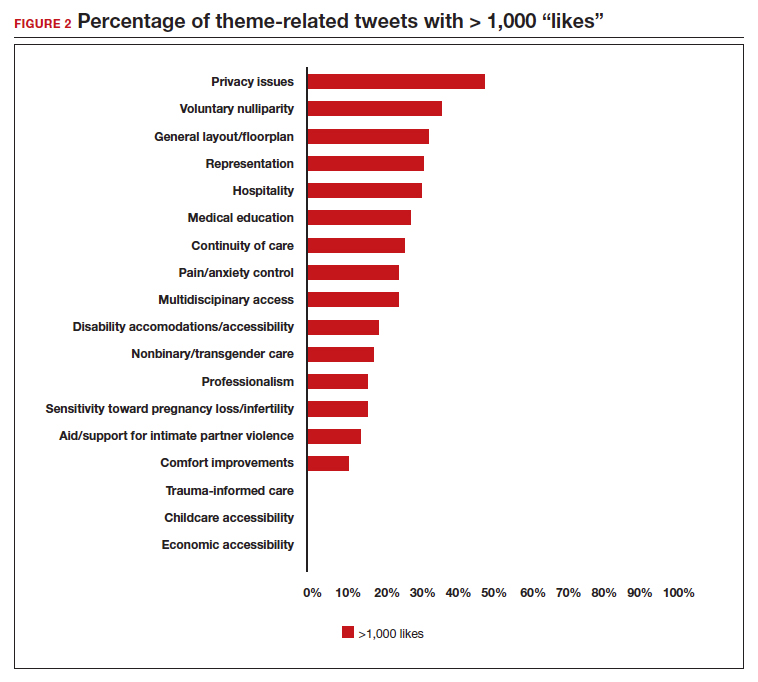

Popular themes. Defined as those with more than 1,000 likes at the time of analysis (FIGURE 2), the most popular themes included:

- privacy issues (48.5% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- voluntary nulliparity (37.0% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- general layout/floorplan (33.4% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- representation (32.1% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- hospitality (31.3% of related tweets with >1,000 likes).

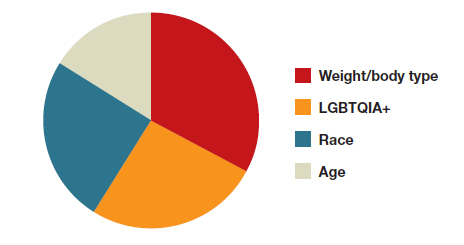

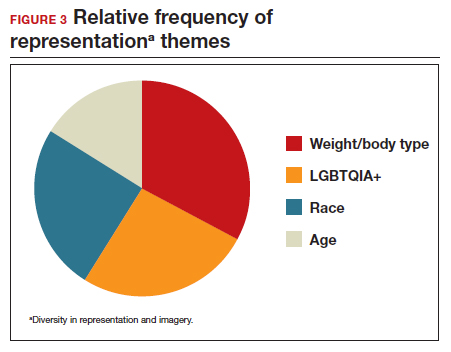

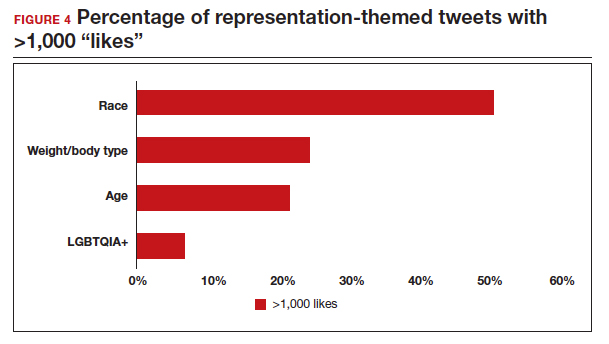

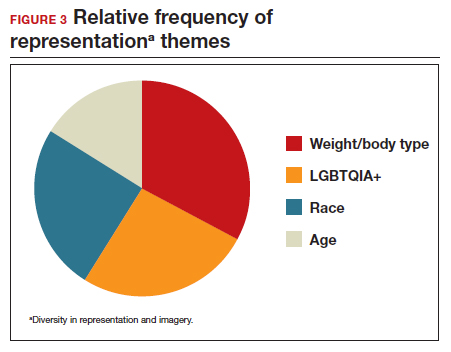

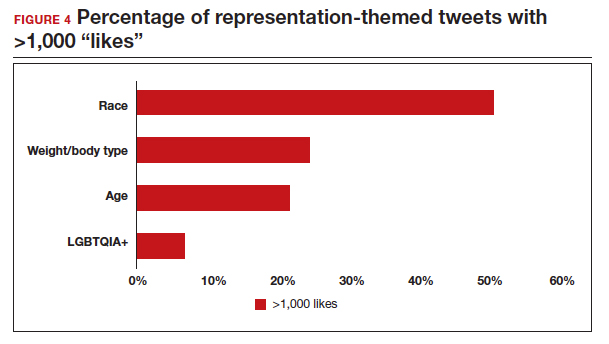

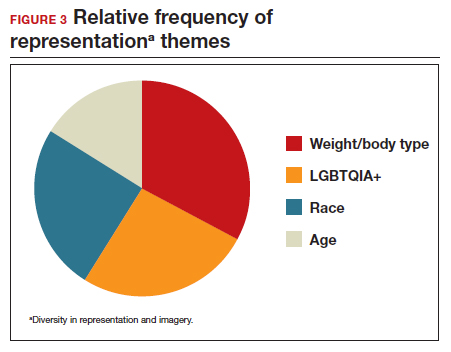

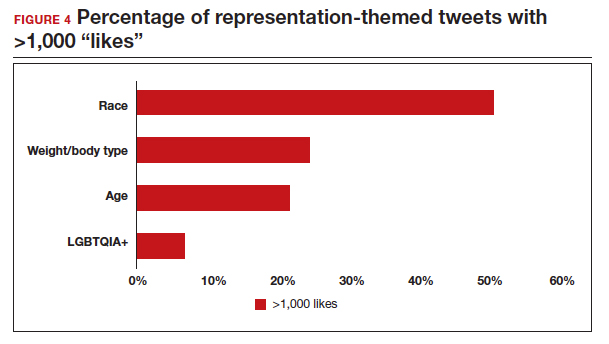

A sub-analysis of themes related to specific types of representation—race, LGBTQIA+, age, and weight/body type was performed. Tweets related to diverse weight/body type representation occurred most frequently (19 code occurrences; FIGURE 3). Similarly, tweets related to the representation of diverse races and the LGBTQIA+ community each comprised 26% of the total representation-based tweets. In terms of popularity as described above, 51.4% of tweets describing racial representation earned >1,000 likes (FIGURE 4).

Tweet demographics. Seven (7/131; 5.3%) of the tweet authors were verified Twitter users and 35 (35/131; 26.7%) authors reported working in the health care field within their Twitter profile description.

Continue to: Implementing our feedback can enhance patient experience and care...

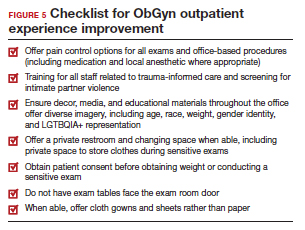

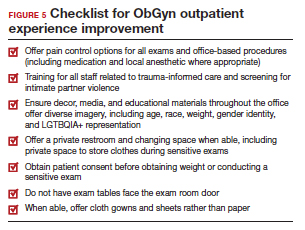

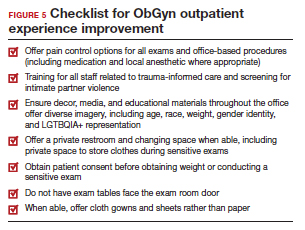

Implementing our feedback can enhance patient experience and care

Our study provides a unique view of the patient perspective through analyzed crowdsourced public opinion via Twitter. To our knowledge, an optimized patient-centered outpatient gynecology experience has not previously been described in the medical literature. Optimizing the found domains of hospitality, comfort measures, pain and anxiety control, privacy, and diverse representationin the outpatient gynecologic experience within the outpatient care setting may ultimately result in improved patient satisfaction, patient well-being, and adherence to care through maximizing patient-centered care. We created a checklist of suggestions, including offering analgesics during office-based procedures and tailoring the floorplan to maximize privacy (FIGURE 5), for improving the outpatient gynecology experience based on our findings.

Prior data on patient satisfaction and outcomes

Improving patient satisfaction with health care is a priority for both clinicians and hospital systems. Prior studies have revealed only variable associations between patient satisfaction, safety, and clinical outcomes. One study involving the analysis of clinical and operational data from 171 hospitals found that hospital size, surgical volume, and low mortality rates were associated with higher patient satisfaction, while favorable surgical outcomes did not consistently correlate with higher Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores.10 Smaller, lower-volume hospitals earned higher satisfaction scores related to cleanliness, quietness, and receiving help measures.10 It has also been shown that the strongest predictors of patient satisfaction with the hospital childbirth experience included items related to staff communication, compassion, empathy, and respect.11 These data suggest that patient satisfaction is likely more significantly impacted by factors other than patient safety and effectiveness, and this was supported by the findings of our analysis. The growing body of literature associating a sense of psychological and physical safety within the health care system and improved patient outcomes and experience suggests that the data gathered from public commentary such as that presented here is extremely important for galvanizing change within the US health care system.

In one systematic review, the relationship between patient-centered care and clinical outcomes was mixed, although generally the association was positive.12 Additionally, patient-centered care was often associated with increased patient satisfaction and well-being. Some studies suggest that patient well-being and satisfaction also may be associated with improved adherence and self-management behaviors.12,13 Overall, optimizing patient-centered care may lead to improved patient satisfaction and potentially improved clinical outcomes.

Additionally, increasing diverse representation in patient materials and illustrations may help to improve the patient experience. Louie and colleagues found that dark skin tones were represented in only 4.5% of 4,146 images from anatomy texts analyzed in 2018.14 Similarly, a photogrammetric analysis of medical images utilized in New England Journal of Medicine found that only 18% of images depicted non-white skin.15 More recent efforts to create a royalty-free digital gallery of images reflecting bodies with diverse skin tones, body shapes, body hair, and age as well as transgender and nonbinary people have been discussed in the lay press.9 Based on our findings, social media users value and are actively seeking diversity in representation and imagery during their outpatient gynecology experience.

Opportunities for future study

Our research utilized social media as a diverse and accessible source of information; however, there are significant opportunities to refine the methodologic approach to answering the fundamental question of creating the patient-centered gynecologic experience. This type of study has not yet been conducted; however, the richness of the information from this current analysis could be informative to survey creation. Future research on this subject outside of social media could bolster the generalizability of our conclusions and the ability to report on qualitative findings in the setting of known patient demographics.

Social media remains a powerful tool as evidenced by this study, and continued use and observation of trending themes among patients is essential. The influence of social media will remain important for answering questions in gynecology and beyond.

Our work is strengthened by social media’s low threshold for use and the ability for widespread access to a diverse group of users. Additionally, social media allows for many responses to be collected in a timely manner, giving strength to the abstracted themes. The constant production of data by X users and their accessibility provide the opportunity for greater geographic coverage in those surveyed.4 Crowdsourced public opinion also has the advantage of producing qualitative metrics in the form of likes and retweets that may provide a reliable measure of public support or engagement.1

Future studies should examine ways to implement the suggested improvements to the office setting in a cost-effective manner and follow both subjective patient-reported outcomes as well as objective data after implementation, as these changes may have implications for much broader public health crises, such as maternal morbidity and mortality.

Study limitations. Our study is limited by the inherent biases and confounders associated with utilizing data derived from social media. Specifically, not all patients who seek outpatient gynecologic care utilize social media and/or X; using a “like” as a surrogate for endorsement of an idea by an identified party limits the generalizability of the data.

The initial Twitter query specified, “I’m asking women”, which may have altered the intended study population, influenced the analysis, and affected the representativeness of the sample through utilizing non ̶inclusive language. While non-binary/transgender care and inclusivity emerged as a theme discussed with the tweets, it is unclear if this represents an independent theme or rather a reaction to the non–inclusive language within the original tweet. ●

The data abstracted was analyzed with Dedoose1 software using a convenience sample and a mixed-methods analysis. Utilizing X (formerly Twitter and referred here as such given the time the study was conducted) for crowdsourcing functions similarly to an open survey. In the absence of similar analyses, a modified Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) checklist was utilized to organize our approach.2

This analysis was comprised of information freely available in the public domain, and the study was classified as IRB exempt. Ethical considerations were made for the fact that this is open access information and participants can reasonably expect their responses to be viewed by the public.3 As this question was not originally intended for research purposes, there was not a formalized development, recruitment, or consent process. The survey was not advertised beyond the original posting on Twitter, and the organic interest that it generated online. No incentives were offered to participants, and all participation was voluntary. There is no mechanism on Twitter for respondents to edit their response, although responses can be deleted. Unique visitors or viewers beyond posted impressions in response to the original tweet could not be determined.

Twitter thread responses were reviewed, and all completed and posted responses to the original Twitter query with 100 or greater “likes” were included in the analysis. These tweets were abstracted from Twitter between December 17, 2021, and December 27, 2021. At the time of tweet abstraction, engagement metrics, including the numbers of likes, retweets, and replies, were recorded. Additionally, author characteristics were abstracted, including author verification status and association with health care, as described in their Twitter profile. Definition of an individual associated with health care was broad and included physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, first responders, and allied health professionals.

A total of 131 tweets met inclusion criteria and were uploaded for analysis using Dedoose qualitative analytic software.1 Two authors independently utilized a qualitative analysis to code the isolated tweets and identify thematic patterns among them. Uploaded tweets were additionally coded based on ranges of likes: 100-500; 501-1,000; 1,001-1,999; and >2,000. Tweets were coded for author verification status and whether or not the author was associated with the health care field. Themes were identified and defined during the coding process and were shared between the two authors. A total of 18 themes were identified, with 1 theme having 4 subdivisions. Interrater reliability testing was performed using Dedoose1 software and resulted with a pooled Cohen’s Kappa of 0.63, indicating “good” agreement between authors, which is an adequate level of agreement per the Dedoose software guidelines.

References

1. Dedoose website. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www .dedoose.com/

2. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES) [published correction appears in J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e8. doi:10.2196/jmir.2042]. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi:10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34

3. Townsend L, Wallace C. Social media research: a guide to ethics [University of Glasgow Information for the Media website]. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://www.gla.ac.uk /media/Media_487729_smxx.pdf

- Garvey MD, Samuel J, Pelaez A. Would you please like my tweet?! An artificially intelligent, generative probabilistic, and econometric based system design for popularity-driven tweet content generation. Decis Support Syst. 2021;144:113497. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2021.113497

- Twitter Revenue and Usage Statistics (2023). Business of apps. Published August 10, 2023. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/twitter-statistics/

- Doan AE, Bogen KW, Higgins E. A content analysis of twitter backlash to Georgia’s abortion ban. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2022;31:100689. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100689

- Roberts H, Sadler J, Chapman L. The value of Twitter data for determining the emotional responses of people to urban green spaces: a case study and critical evaluation. Urban Stud. 2019;56:818-835. doi: 10.1177/0042098017748544

- Stewart R [@stuboo]. I have the opportunity to design my office from scratch. I’m asking women. How would you design/optimize a visit to the gynecologist’s office? problems frustrations solutions No detail is too small. If I’ve ever had a tweet worthy of virality, it’s this one. RT. Twitter. Published December 5, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://twitter .com/stuboo/status/1467522852664532994

- A gynecologist asked Twitter how he should redesign his office. The answers he got were about deeper health care issues. Fortune. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://fortune .com/2021/12/07/gynecologist-twitter-question/

- Anderson GD, Nelson-Becker C, Hannigan EV, et al. A patientcentered health care delivery system by a university obstetrics and gynecology department. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:205210. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000146288.28195.27

- Ades V, Wu SX, Rabinowitz E, et al. An integrated, traumainformed care model for female survivors of sexual violence: the engage, motivate, protect, organize, self-worth, educate, respect (EMPOWER) clinic. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:803809. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003186

- Gordon D. Health equity comes to medical illustrations with launch of new image library. Forbes. Accessed March 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/debgordon/2022/05/11 /health-equity-comes-to-medical-illustrations-with-launch -of-new-image-library/

- Kennedy GD, Tevis SE, Kent KC. Is there a relationship between patient satisfaction and favorable outcomes? Ann Surg. 2014;260:592-600. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000932

- Gregory KD, Korst LM, Saeb S, et al. Childbirth-specific patient-reported outcomes as predictors of hospital satisfaction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:201.e1-201.e19. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.093

- Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:351-379. doi:10.1177/1077558712465774

- Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, et al. Patient-centered experiences in breast cancer: predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Med Care. 2007;45:431-439. doi:10.1097/01 .mlr.0000257193.10760.7

- Louie P, Wilkes R. Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery. Soc Sci Med. 2018;202:38-42. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.023

- Massie JP, Cho DY, Kneib CJ, et al. A picture of modern medicine: race and visual representation in medical literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:88-94. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2020.07.013

There has been increasing awareness of a need for creating a more patient-centered experience with outpatient gynecology; however, very little data exist about what interventions are important to patients. Given social media’s ease of use and ability for widespread access to a diverse group of users, it has the potential to be a powerful tool for qualitative research questions without the difficulties of cost, transportation, transcription, etc. required of a focus group. Crowdsourced public opinion also has the advantage of producing qualitative metrics in the form of “likes” that, at scale, can provide a reliable measure of public support or engagement for a particular concept.1 Particularly for topics that are controversial or novel, X (formerly Twitter, and referred to as Twitter intermittently throughout this article based on the time the study was conducted), with 300 million monthly users,2 has become a popular tool for general and health care ̶ focused content and sentiment analysis.3,4 This study presents a qualitative analysis of themes from a crowdsourced request on Twitter to design the ideal outpatient gynecologic experience that subsequently went “viral”.5,6

When asked to design the optimized outpatient gynecology experience, social media users expressed:

- hospitality, comfort, and pain control as frequent themes

- preserving privacy and acknowledgement of voluntary nulliparity as frequent themes

- a desire for diverse imagery and representation related to race, LGBTQIA+ themes, age, and weight/body type within the office setting

- a call for a sense of psychological safety within gynecology

Why the need for our research question on patient-centered gyn care

While the body of literature on patient-centered health care has grown rapidly in recent years, a patient-centered outpatient gynecology experience has not yet been described in the medical literature.

Patient-centered office design, driven by cultural sensitivity, has been shown in other studies to be both appreciated by established patients and a viable business strategy to attract new patients.7 Topics such as pain control, trauma-informed care in gynecologyclinics,8 and diverse representation in patient materials and illustrations9 have been popular topics in medicine and in the lay press. Our primary aim in our research was to utilize feedback from the question posed to quantify and rank patient-centered interventions in a gynecology office. These themes and others that emerged in our analysis were used to suggest b

What we asked social media users. The survey query to social media users, “I have the opportunity to design my office from scratch. I’m asking women: How would you design/optimize a visit to the gynecologist’s office?” was crowd-sourced via Twitter on December 5, 2021.5 Given a robust response to the query, it provided an opportunity for a qualitative research study exploring social media users’ perspectives on optimizing outpatient gynecologic care, although the original question was not planned for research utilization.

What we found

By December 27, 2021, the original tweet had earned 9,411 likes; 2,143 retweets; and 3,400 replies. Of this group, we analyzed 131 tweets, all of which had 100 or greater likes on Twitter at the time of the review. The majority of analyzed tweets earned between 100 ̶ 500 likes (75/131; 57.3%), while 22.9% (30/131) had 501 ̶ 1,000 likes, 11.5% (15/131) had >2,000 likes, and 8.4% (11/131) had 1,001 ̶ 1,999 likes.

Identified themes within the tweets analyzed included: medical education, comfort improvements, continuity of care, disability accommodations/accessibility, economic accessibility, nonbinary/transgender care and inclusivity, general layout/floorplan, hospitality, aid for intimate partner violence, childcare accessibility, multi-disciplinary care access, pain/anxiety control, sensitivity toward pregnancy loss/fertility issues, privacy issues, professionalism, representation (subdivided into race, LGBTQIA+, age, and weight/body type), trauma-informed care, and acknowledgement of voluntary nulliparity/support for reproductive choices (TABLE 1). TABLE 2 lists examples of popular tweets by selected themes.

Frequent themes. The most frequently occurring themes within the 131 analyzed tweets (FIGURE 1) were:

- hospitality (77 occurrences)

- comfort improvements (75 occurrences)

- general layout/floorplan (75 occurrences)

- pain/anxiety control (55 occurrences)

- representation (53 occurrences).

Popular themes. Defined as those with more than 1,000 likes at the time of analysis (FIGURE 2), the most popular themes included:

- privacy issues (48.5% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- voluntary nulliparity (37.0% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- general layout/floorplan (33.4% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- representation (32.1% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- hospitality (31.3% of related tweets with >1,000 likes).

A sub-analysis of themes related to specific types of representation—race, LGBTQIA+, age, and weight/body type was performed. Tweets related to diverse weight/body type representation occurred most frequently (19 code occurrences; FIGURE 3). Similarly, tweets related to the representation of diverse races and the LGBTQIA+ community each comprised 26% of the total representation-based tweets. In terms of popularity as described above, 51.4% of tweets describing racial representation earned >1,000 likes (FIGURE 4).

Tweet demographics. Seven (7/131; 5.3%) of the tweet authors were verified Twitter users and 35 (35/131; 26.7%) authors reported working in the health care field within their Twitter profile description.

Continue to: Implementing our feedback can enhance patient experience and care...

Implementing our feedback can enhance patient experience and care

Our study provides a unique view of the patient perspective through analyzed crowdsourced public opinion via Twitter. To our knowledge, an optimized patient-centered outpatient gynecology experience has not previously been described in the medical literature. Optimizing the found domains of hospitality, comfort measures, pain and anxiety control, privacy, and diverse representationin the outpatient gynecologic experience within the outpatient care setting may ultimately result in improved patient satisfaction, patient well-being, and adherence to care through maximizing patient-centered care. We created a checklist of suggestions, including offering analgesics during office-based procedures and tailoring the floorplan to maximize privacy (FIGURE 5), for improving the outpatient gynecology experience based on our findings.

Prior data on patient satisfaction and outcomes

Improving patient satisfaction with health care is a priority for both clinicians and hospital systems. Prior studies have revealed only variable associations between patient satisfaction, safety, and clinical outcomes. One study involving the analysis of clinical and operational data from 171 hospitals found that hospital size, surgical volume, and low mortality rates were associated with higher patient satisfaction, while favorable surgical outcomes did not consistently correlate with higher Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores.10 Smaller, lower-volume hospitals earned higher satisfaction scores related to cleanliness, quietness, and receiving help measures.10 It has also been shown that the strongest predictors of patient satisfaction with the hospital childbirth experience included items related to staff communication, compassion, empathy, and respect.11 These data suggest that patient satisfaction is likely more significantly impacted by factors other than patient safety and effectiveness, and this was supported by the findings of our analysis. The growing body of literature associating a sense of psychological and physical safety within the health care system and improved patient outcomes and experience suggests that the data gathered from public commentary such as that presented here is extremely important for galvanizing change within the US health care system.

In one systematic review, the relationship between patient-centered care and clinical outcomes was mixed, although generally the association was positive.12 Additionally, patient-centered care was often associated with increased patient satisfaction and well-being. Some studies suggest that patient well-being and satisfaction also may be associated with improved adherence and self-management behaviors.12,13 Overall, optimizing patient-centered care may lead to improved patient satisfaction and potentially improved clinical outcomes.

Additionally, increasing diverse representation in patient materials and illustrations may help to improve the patient experience. Louie and colleagues found that dark skin tones were represented in only 4.5% of 4,146 images from anatomy texts analyzed in 2018.14 Similarly, a photogrammetric analysis of medical images utilized in New England Journal of Medicine found that only 18% of images depicted non-white skin.15 More recent efforts to create a royalty-free digital gallery of images reflecting bodies with diverse skin tones, body shapes, body hair, and age as well as transgender and nonbinary people have been discussed in the lay press.9 Based on our findings, social media users value and are actively seeking diversity in representation and imagery during their outpatient gynecology experience.

Opportunities for future study

Our research utilized social media as a diverse and accessible source of information; however, there are significant opportunities to refine the methodologic approach to answering the fundamental question of creating the patient-centered gynecologic experience. This type of study has not yet been conducted; however, the richness of the information from this current analysis could be informative to survey creation. Future research on this subject outside of social media could bolster the generalizability of our conclusions and the ability to report on qualitative findings in the setting of known patient demographics.

Social media remains a powerful tool as evidenced by this study, and continued use and observation of trending themes among patients is essential. The influence of social media will remain important for answering questions in gynecology and beyond.

Our work is strengthened by social media’s low threshold for use and the ability for widespread access to a diverse group of users. Additionally, social media allows for many responses to be collected in a timely manner, giving strength to the abstracted themes. The constant production of data by X users and their accessibility provide the opportunity for greater geographic coverage in those surveyed.4 Crowdsourced public opinion also has the advantage of producing qualitative metrics in the form of likes and retweets that may provide a reliable measure of public support or engagement.1

Future studies should examine ways to implement the suggested improvements to the office setting in a cost-effective manner and follow both subjective patient-reported outcomes as well as objective data after implementation, as these changes may have implications for much broader public health crises, such as maternal morbidity and mortality.

Study limitations. Our study is limited by the inherent biases and confounders associated with utilizing data derived from social media. Specifically, not all patients who seek outpatient gynecologic care utilize social media and/or X; using a “like” as a surrogate for endorsement of an idea by an identified party limits the generalizability of the data.

The initial Twitter query specified, “I’m asking women”, which may have altered the intended study population, influenced the analysis, and affected the representativeness of the sample through utilizing non ̶inclusive language. While non-binary/transgender care and inclusivity emerged as a theme discussed with the tweets, it is unclear if this represents an independent theme or rather a reaction to the non–inclusive language within the original tweet. ●

The data abstracted was analyzed with Dedoose1 software using a convenience sample and a mixed-methods analysis. Utilizing X (formerly Twitter and referred here as such given the time the study was conducted) for crowdsourcing functions similarly to an open survey. In the absence of similar analyses, a modified Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) checklist was utilized to organize our approach.2

This analysis was comprised of information freely available in the public domain, and the study was classified as IRB exempt. Ethical considerations were made for the fact that this is open access information and participants can reasonably expect their responses to be viewed by the public.3 As this question was not originally intended for research purposes, there was not a formalized development, recruitment, or consent process. The survey was not advertised beyond the original posting on Twitter, and the organic interest that it generated online. No incentives were offered to participants, and all participation was voluntary. There is no mechanism on Twitter for respondents to edit their response, although responses can be deleted. Unique visitors or viewers beyond posted impressions in response to the original tweet could not be determined.

Twitter thread responses were reviewed, and all completed and posted responses to the original Twitter query with 100 or greater “likes” were included in the analysis. These tweets were abstracted from Twitter between December 17, 2021, and December 27, 2021. At the time of tweet abstraction, engagement metrics, including the numbers of likes, retweets, and replies, were recorded. Additionally, author characteristics were abstracted, including author verification status and association with health care, as described in their Twitter profile. Definition of an individual associated with health care was broad and included physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, first responders, and allied health professionals.

A total of 131 tweets met inclusion criteria and were uploaded for analysis using Dedoose qualitative analytic software.1 Two authors independently utilized a qualitative analysis to code the isolated tweets and identify thematic patterns among them. Uploaded tweets were additionally coded based on ranges of likes: 100-500; 501-1,000; 1,001-1,999; and >2,000. Tweets were coded for author verification status and whether or not the author was associated with the health care field. Themes were identified and defined during the coding process and were shared between the two authors. A total of 18 themes were identified, with 1 theme having 4 subdivisions. Interrater reliability testing was performed using Dedoose1 software and resulted with a pooled Cohen’s Kappa of 0.63, indicating “good” agreement between authors, which is an adequate level of agreement per the Dedoose software guidelines.

References

1. Dedoose website. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www .dedoose.com/

2. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES) [published correction appears in J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e8. doi:10.2196/jmir.2042]. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi:10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34

3. Townsend L, Wallace C. Social media research: a guide to ethics [University of Glasgow Information for the Media website]. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://www.gla.ac.uk /media/Media_487729_smxx.pdf

There has been increasing awareness of a need for creating a more patient-centered experience with outpatient gynecology; however, very little data exist about what interventions are important to patients. Given social media’s ease of use and ability for widespread access to a diverse group of users, it has the potential to be a powerful tool for qualitative research questions without the difficulties of cost, transportation, transcription, etc. required of a focus group. Crowdsourced public opinion also has the advantage of producing qualitative metrics in the form of “likes” that, at scale, can provide a reliable measure of public support or engagement for a particular concept.1 Particularly for topics that are controversial or novel, X (formerly Twitter, and referred to as Twitter intermittently throughout this article based on the time the study was conducted), with 300 million monthly users,2 has become a popular tool for general and health care ̶ focused content and sentiment analysis.3,4 This study presents a qualitative analysis of themes from a crowdsourced request on Twitter to design the ideal outpatient gynecologic experience that subsequently went “viral”.5,6

When asked to design the optimized outpatient gynecology experience, social media users expressed:

- hospitality, comfort, and pain control as frequent themes

- preserving privacy and acknowledgement of voluntary nulliparity as frequent themes

- a desire for diverse imagery and representation related to race, LGBTQIA+ themes, age, and weight/body type within the office setting

- a call for a sense of psychological safety within gynecology

Why the need for our research question on patient-centered gyn care

While the body of literature on patient-centered health care has grown rapidly in recent years, a patient-centered outpatient gynecology experience has not yet been described in the medical literature.

Patient-centered office design, driven by cultural sensitivity, has been shown in other studies to be both appreciated by established patients and a viable business strategy to attract new patients.7 Topics such as pain control, trauma-informed care in gynecologyclinics,8 and diverse representation in patient materials and illustrations9 have been popular topics in medicine and in the lay press. Our primary aim in our research was to utilize feedback from the question posed to quantify and rank patient-centered interventions in a gynecology office. These themes and others that emerged in our analysis were used to suggest b

What we asked social media users. The survey query to social media users, “I have the opportunity to design my office from scratch. I’m asking women: How would you design/optimize a visit to the gynecologist’s office?” was crowd-sourced via Twitter on December 5, 2021.5 Given a robust response to the query, it provided an opportunity for a qualitative research study exploring social media users’ perspectives on optimizing outpatient gynecologic care, although the original question was not planned for research utilization.

What we found

By December 27, 2021, the original tweet had earned 9,411 likes; 2,143 retweets; and 3,400 replies. Of this group, we analyzed 131 tweets, all of which had 100 or greater likes on Twitter at the time of the review. The majority of analyzed tweets earned between 100 ̶ 500 likes (75/131; 57.3%), while 22.9% (30/131) had 501 ̶ 1,000 likes, 11.5% (15/131) had >2,000 likes, and 8.4% (11/131) had 1,001 ̶ 1,999 likes.

Identified themes within the tweets analyzed included: medical education, comfort improvements, continuity of care, disability accommodations/accessibility, economic accessibility, nonbinary/transgender care and inclusivity, general layout/floorplan, hospitality, aid for intimate partner violence, childcare accessibility, multi-disciplinary care access, pain/anxiety control, sensitivity toward pregnancy loss/fertility issues, privacy issues, professionalism, representation (subdivided into race, LGBTQIA+, age, and weight/body type), trauma-informed care, and acknowledgement of voluntary nulliparity/support for reproductive choices (TABLE 1). TABLE 2 lists examples of popular tweets by selected themes.

Frequent themes. The most frequently occurring themes within the 131 analyzed tweets (FIGURE 1) were:

- hospitality (77 occurrences)

- comfort improvements (75 occurrences)

- general layout/floorplan (75 occurrences)

- pain/anxiety control (55 occurrences)

- representation (53 occurrences).

Popular themes. Defined as those with more than 1,000 likes at the time of analysis (FIGURE 2), the most popular themes included:

- privacy issues (48.5% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- voluntary nulliparity (37.0% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- general layout/floorplan (33.4% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- representation (32.1% of related tweets with >1,000 likes)

- hospitality (31.3% of related tweets with >1,000 likes).

A sub-analysis of themes related to specific types of representation—race, LGBTQIA+, age, and weight/body type was performed. Tweets related to diverse weight/body type representation occurred most frequently (19 code occurrences; FIGURE 3). Similarly, tweets related to the representation of diverse races and the LGBTQIA+ community each comprised 26% of the total representation-based tweets. In terms of popularity as described above, 51.4% of tweets describing racial representation earned >1,000 likes (FIGURE 4).

Tweet demographics. Seven (7/131; 5.3%) of the tweet authors were verified Twitter users and 35 (35/131; 26.7%) authors reported working in the health care field within their Twitter profile description.

Continue to: Implementing our feedback can enhance patient experience and care...

Implementing our feedback can enhance patient experience and care

Our study provides a unique view of the patient perspective through analyzed crowdsourced public opinion via Twitter. To our knowledge, an optimized patient-centered outpatient gynecology experience has not previously been described in the medical literature. Optimizing the found domains of hospitality, comfort measures, pain and anxiety control, privacy, and diverse representationin the outpatient gynecologic experience within the outpatient care setting may ultimately result in improved patient satisfaction, patient well-being, and adherence to care through maximizing patient-centered care. We created a checklist of suggestions, including offering analgesics during office-based procedures and tailoring the floorplan to maximize privacy (FIGURE 5), for improving the outpatient gynecology experience based on our findings.

Prior data on patient satisfaction and outcomes

Improving patient satisfaction with health care is a priority for both clinicians and hospital systems. Prior studies have revealed only variable associations between patient satisfaction, safety, and clinical outcomes. One study involving the analysis of clinical and operational data from 171 hospitals found that hospital size, surgical volume, and low mortality rates were associated with higher patient satisfaction, while favorable surgical outcomes did not consistently correlate with higher Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores.10 Smaller, lower-volume hospitals earned higher satisfaction scores related to cleanliness, quietness, and receiving help measures.10 It has also been shown that the strongest predictors of patient satisfaction with the hospital childbirth experience included items related to staff communication, compassion, empathy, and respect.11 These data suggest that patient satisfaction is likely more significantly impacted by factors other than patient safety and effectiveness, and this was supported by the findings of our analysis. The growing body of literature associating a sense of psychological and physical safety within the health care system and improved patient outcomes and experience suggests that the data gathered from public commentary such as that presented here is extremely important for galvanizing change within the US health care system.

In one systematic review, the relationship between patient-centered care and clinical outcomes was mixed, although generally the association was positive.12 Additionally, patient-centered care was often associated with increased patient satisfaction and well-being. Some studies suggest that patient well-being and satisfaction also may be associated with improved adherence and self-management behaviors.12,13 Overall, optimizing patient-centered care may lead to improved patient satisfaction and potentially improved clinical outcomes.

Additionally, increasing diverse representation in patient materials and illustrations may help to improve the patient experience. Louie and colleagues found that dark skin tones were represented in only 4.5% of 4,146 images from anatomy texts analyzed in 2018.14 Similarly, a photogrammetric analysis of medical images utilized in New England Journal of Medicine found that only 18% of images depicted non-white skin.15 More recent efforts to create a royalty-free digital gallery of images reflecting bodies with diverse skin tones, body shapes, body hair, and age as well as transgender and nonbinary people have been discussed in the lay press.9 Based on our findings, social media users value and are actively seeking diversity in representation and imagery during their outpatient gynecology experience.

Opportunities for future study

Our research utilized social media as a diverse and accessible source of information; however, there are significant opportunities to refine the methodologic approach to answering the fundamental question of creating the patient-centered gynecologic experience. This type of study has not yet been conducted; however, the richness of the information from this current analysis could be informative to survey creation. Future research on this subject outside of social media could bolster the generalizability of our conclusions and the ability to report on qualitative findings in the setting of known patient demographics.

Social media remains a powerful tool as evidenced by this study, and continued use and observation of trending themes among patients is essential. The influence of social media will remain important for answering questions in gynecology and beyond.

Our work is strengthened by social media’s low threshold for use and the ability for widespread access to a diverse group of users. Additionally, social media allows for many responses to be collected in a timely manner, giving strength to the abstracted themes. The constant production of data by X users and their accessibility provide the opportunity for greater geographic coverage in those surveyed.4 Crowdsourced public opinion also has the advantage of producing qualitative metrics in the form of likes and retweets that may provide a reliable measure of public support or engagement.1

Future studies should examine ways to implement the suggested improvements to the office setting in a cost-effective manner and follow both subjective patient-reported outcomes as well as objective data after implementation, as these changes may have implications for much broader public health crises, such as maternal morbidity and mortality.

Study limitations. Our study is limited by the inherent biases and confounders associated with utilizing data derived from social media. Specifically, not all patients who seek outpatient gynecologic care utilize social media and/or X; using a “like” as a surrogate for endorsement of an idea by an identified party limits the generalizability of the data.

The initial Twitter query specified, “I’m asking women”, which may have altered the intended study population, influenced the analysis, and affected the representativeness of the sample through utilizing non ̶inclusive language. While non-binary/transgender care and inclusivity emerged as a theme discussed with the tweets, it is unclear if this represents an independent theme or rather a reaction to the non–inclusive language within the original tweet. ●

The data abstracted was analyzed with Dedoose1 software using a convenience sample and a mixed-methods analysis. Utilizing X (formerly Twitter and referred here as such given the time the study was conducted) for crowdsourcing functions similarly to an open survey. In the absence of similar analyses, a modified Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) checklist was utilized to organize our approach.2

This analysis was comprised of information freely available in the public domain, and the study was classified as IRB exempt. Ethical considerations were made for the fact that this is open access information and participants can reasonably expect their responses to be viewed by the public.3 As this question was not originally intended for research purposes, there was not a formalized development, recruitment, or consent process. The survey was not advertised beyond the original posting on Twitter, and the organic interest that it generated online. No incentives were offered to participants, and all participation was voluntary. There is no mechanism on Twitter for respondents to edit their response, although responses can be deleted. Unique visitors or viewers beyond posted impressions in response to the original tweet could not be determined.

Twitter thread responses were reviewed, and all completed and posted responses to the original Twitter query with 100 or greater “likes” were included in the analysis. These tweets were abstracted from Twitter between December 17, 2021, and December 27, 2021. At the time of tweet abstraction, engagement metrics, including the numbers of likes, retweets, and replies, were recorded. Additionally, author characteristics were abstracted, including author verification status and association with health care, as described in their Twitter profile. Definition of an individual associated with health care was broad and included physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, first responders, and allied health professionals.

A total of 131 tweets met inclusion criteria and were uploaded for analysis using Dedoose qualitative analytic software.1 Two authors independently utilized a qualitative analysis to code the isolated tweets and identify thematic patterns among them. Uploaded tweets were additionally coded based on ranges of likes: 100-500; 501-1,000; 1,001-1,999; and >2,000. Tweets were coded for author verification status and whether or not the author was associated with the health care field. Themes were identified and defined during the coding process and were shared between the two authors. A total of 18 themes were identified, with 1 theme having 4 subdivisions. Interrater reliability testing was performed using Dedoose1 software and resulted with a pooled Cohen’s Kappa of 0.63, indicating “good” agreement between authors, which is an adequate level of agreement per the Dedoose software guidelines.

References

1. Dedoose website. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www .dedoose.com/

2. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES) [published correction appears in J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e8. doi:10.2196/jmir.2042]. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi:10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34

3. Townsend L, Wallace C. Social media research: a guide to ethics [University of Glasgow Information for the Media website]. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://www.gla.ac.uk /media/Media_487729_smxx.pdf

- Garvey MD, Samuel J, Pelaez A. Would you please like my tweet?! An artificially intelligent, generative probabilistic, and econometric based system design for popularity-driven tweet content generation. Decis Support Syst. 2021;144:113497. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2021.113497

- Twitter Revenue and Usage Statistics (2023). Business of apps. Published August 10, 2023. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/twitter-statistics/

- Doan AE, Bogen KW, Higgins E. A content analysis of twitter backlash to Georgia’s abortion ban. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2022;31:100689. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100689

- Roberts H, Sadler J, Chapman L. The value of Twitter data for determining the emotional responses of people to urban green spaces: a case study and critical evaluation. Urban Stud. 2019;56:818-835. doi: 10.1177/0042098017748544

- Stewart R [@stuboo]. I have the opportunity to design my office from scratch. I’m asking women. How would you design/optimize a visit to the gynecologist’s office? problems frustrations solutions No detail is too small. If I’ve ever had a tweet worthy of virality, it’s this one. RT. Twitter. Published December 5, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://twitter .com/stuboo/status/1467522852664532994

- A gynecologist asked Twitter how he should redesign his office. The answers he got were about deeper health care issues. Fortune. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://fortune .com/2021/12/07/gynecologist-twitter-question/

- Anderson GD, Nelson-Becker C, Hannigan EV, et al. A patientcentered health care delivery system by a university obstetrics and gynecology department. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:205210. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000146288.28195.27

- Ades V, Wu SX, Rabinowitz E, et al. An integrated, traumainformed care model for female survivors of sexual violence: the engage, motivate, protect, organize, self-worth, educate, respect (EMPOWER) clinic. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:803809. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003186

- Gordon D. Health equity comes to medical illustrations with launch of new image library. Forbes. Accessed March 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/debgordon/2022/05/11 /health-equity-comes-to-medical-illustrations-with-launch -of-new-image-library/

- Kennedy GD, Tevis SE, Kent KC. Is there a relationship between patient satisfaction and favorable outcomes? Ann Surg. 2014;260:592-600. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000932

- Gregory KD, Korst LM, Saeb S, et al. Childbirth-specific patient-reported outcomes as predictors of hospital satisfaction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:201.e1-201.e19. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.093

- Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:351-379. doi:10.1177/1077558712465774

- Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, et al. Patient-centered experiences in breast cancer: predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Med Care. 2007;45:431-439. doi:10.1097/01 .mlr.0000257193.10760.7

- Louie P, Wilkes R. Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery. Soc Sci Med. 2018;202:38-42. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.023

- Massie JP, Cho DY, Kneib CJ, et al. A picture of modern medicine: race and visual representation in medical literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:88-94. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2020.07.013

- Garvey MD, Samuel J, Pelaez A. Would you please like my tweet?! An artificially intelligent, generative probabilistic, and econometric based system design for popularity-driven tweet content generation. Decis Support Syst. 2021;144:113497. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2021.113497

- Twitter Revenue and Usage Statistics (2023). Business of apps. Published August 10, 2023. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/twitter-statistics/

- Doan AE, Bogen KW, Higgins E. A content analysis of twitter backlash to Georgia’s abortion ban. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2022;31:100689. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100689

- Roberts H, Sadler J, Chapman L. The value of Twitter data for determining the emotional responses of people to urban green spaces: a case study and critical evaluation. Urban Stud. 2019;56:818-835. doi: 10.1177/0042098017748544

- Stewart R [@stuboo]. I have the opportunity to design my office from scratch. I’m asking women. How would you design/optimize a visit to the gynecologist’s office? problems frustrations solutions No detail is too small. If I’ve ever had a tweet worthy of virality, it’s this one. RT. Twitter. Published December 5, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://twitter .com/stuboo/status/1467522852664532994

- A gynecologist asked Twitter how he should redesign his office. The answers he got were about deeper health care issues. Fortune. Accessed March 2, 2023. https://fortune .com/2021/12/07/gynecologist-twitter-question/

- Anderson GD, Nelson-Becker C, Hannigan EV, et al. A patientcentered health care delivery system by a university obstetrics and gynecology department. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:205210. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000146288.28195.27

- Ades V, Wu SX, Rabinowitz E, et al. An integrated, traumainformed care model for female survivors of sexual violence: the engage, motivate, protect, organize, self-worth, educate, respect (EMPOWER) clinic. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:803809. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003186

- Gordon D. Health equity comes to medical illustrations with launch of new image library. Forbes. Accessed March 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/debgordon/2022/05/11 /health-equity-comes-to-medical-illustrations-with-launch -of-new-image-library/

- Kennedy GD, Tevis SE, Kent KC. Is there a relationship between patient satisfaction and favorable outcomes? Ann Surg. 2014;260:592-600. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000932

- Gregory KD, Korst LM, Saeb S, et al. Childbirth-specific patient-reported outcomes as predictors of hospital satisfaction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:201.e1-201.e19. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.093

- Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:351-379. doi:10.1177/1077558712465774

- Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, et al. Patient-centered experiences in breast cancer: predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Med Care. 2007;45:431-439. doi:10.1097/01 .mlr.0000257193.10760.7

- Louie P, Wilkes R. Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery. Soc Sci Med. 2018;202:38-42. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.023

- Massie JP, Cho DY, Kneib CJ, et al. A picture of modern medicine: race and visual representation in medical literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:88-94. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2020.07.013

What the first authorized DNA cancer risk test can and can’t tell you

A novel DNA test system that assesses a person’s genetic predisposition for certain cancers – the first of its kind granted marketing authorization by the Food and Drug Administration – may become a valuable new public health tool.

The Common Hereditary Cancers Panel (Invitae) was approved late September following FDA review under the De Novo process, a regulatory pathway for new types of low- to moderate-risk devices.

Validation of the prescription-only in vitro test was based on assessments of more than 9,000 clinical samples, which demonstrated accuracy of at least 99% for all tested variants in 47 genes known to be associated with an increased risk of developing certain cancers, including breast, ovarian, uterine, prostate, colorectal, gastric, pancreatic as well as melanoma.

How the test system works

Next-generation sequencing assesses germline human genomic DNA extracted from a single blood sample collected at the point of care, such as a doctor’s office, and is sent to a laboratory for analysis.

Specifically, the system aims to detect substitutions, small insertion and deletion alterations, and copy number variants in the panel of 47 targeted genes.

Jeff Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological health, explained in an FDA press release announcing the marketing authorization.

Clinical interpretation is based on evidence from the published literature, prediction programs, public databases, and Invitae’s own variants database, the FDA statement explained.

What the test can do

Not only can the Common Hereditary Cancer Panel identify genetic variants that increase an individual’s risk of certain cancers, the panel can also help identify potential cancer-related hereditary variants in patients already diagnosed with cancer.

The most clinically significant genes the test system can detect include BRCA1 and BRCA2, which have known associations with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome; Lynch syndrome–associated genes including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM; CDH1, which is largely associated with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer and lobular breast cancer; and STK11, which is associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

“Patients should speak with a health care professional, such as a genetic counselor, to discuss any personal/family history of cancer, as such information can be helpful in interpreting test results,” the FDA advised.

What the test can’t do

The test is not intended to identify or evaluate all known genes tied to a person’s potential predisposition for cancer. The test is also not intended for cancer screening or prenatal testing.

For these reasons, and because genetics are not the only factor associated with developing cancer, negative test results could lead to misunderstanding among some patients about their cancer risk.

“Results are intended to be interpreted within the context of additional laboratory results, family history, and clinical findings,” the company wrote in a statement.

Test safety

Risks associated with the test include the possibility of false positive and false negative results and the potential for people to misunderstand what the results mean about their risk for cancer.

A false sense of assurance after a false negative result might, for instance, lead patients to forgo recommended surveillance or clinical management, whereas false positive test results could lead to inappropriate decision-making and undesirable consequences.

“These risks are mitigated by the analytical performance validation, clinical validation, and appropriate labeling of this test,” the agency explained.

Along with the De Novo authorization, the FDA is establishing special controls to define requirements for these tests. For instance, accuracy must be 99% or higher for positive agreement and at least 99.9% for negative agreement with a validated, independent method.

Public health implications

The information gleaned from this tool can “help guide physicians to provide appropriate monitoring and potential therapy, based on discovered variants,” Dr. Shuren said.

The marketing authorization of Invitae’s test established a new regulatory category, which “means that subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through FDA’s 510(k) premarket process,” the FDA explained.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel DNA test system that assesses a person’s genetic predisposition for certain cancers – the first of its kind granted marketing authorization by the Food and Drug Administration – may become a valuable new public health tool.

The Common Hereditary Cancers Panel (Invitae) was approved late September following FDA review under the De Novo process, a regulatory pathway for new types of low- to moderate-risk devices.

Validation of the prescription-only in vitro test was based on assessments of more than 9,000 clinical samples, which demonstrated accuracy of at least 99% for all tested variants in 47 genes known to be associated with an increased risk of developing certain cancers, including breast, ovarian, uterine, prostate, colorectal, gastric, pancreatic as well as melanoma.

How the test system works

Next-generation sequencing assesses germline human genomic DNA extracted from a single blood sample collected at the point of care, such as a doctor’s office, and is sent to a laboratory for analysis.

Specifically, the system aims to detect substitutions, small insertion and deletion alterations, and copy number variants in the panel of 47 targeted genes.

Jeff Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological health, explained in an FDA press release announcing the marketing authorization.

Clinical interpretation is based on evidence from the published literature, prediction programs, public databases, and Invitae’s own variants database, the FDA statement explained.

What the test can do

Not only can the Common Hereditary Cancer Panel identify genetic variants that increase an individual’s risk of certain cancers, the panel can also help identify potential cancer-related hereditary variants in patients already diagnosed with cancer.

The most clinically significant genes the test system can detect include BRCA1 and BRCA2, which have known associations with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome; Lynch syndrome–associated genes including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM; CDH1, which is largely associated with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer and lobular breast cancer; and STK11, which is associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

“Patients should speak with a health care professional, such as a genetic counselor, to discuss any personal/family history of cancer, as such information can be helpful in interpreting test results,” the FDA advised.

What the test can’t do

The test is not intended to identify or evaluate all known genes tied to a person’s potential predisposition for cancer. The test is also not intended for cancer screening or prenatal testing.