User login

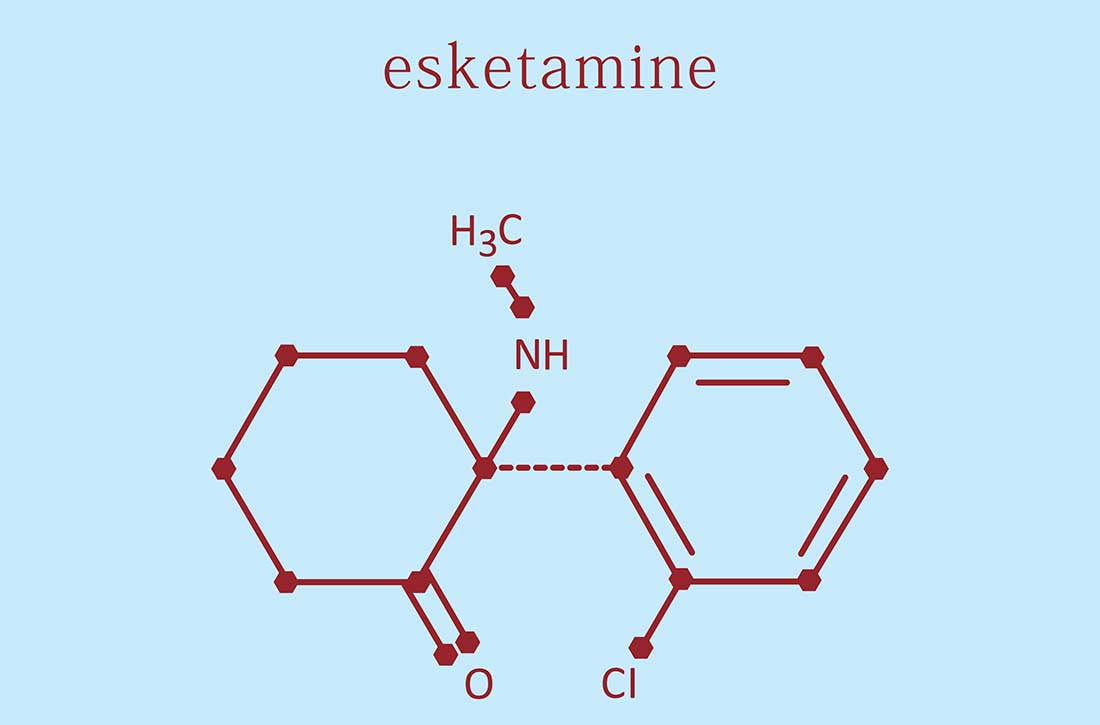

Intranasal esketamine: A primer

Intranasal esketamine is an FDA-approved ketamine molecule indicated for use together with an oral antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in patients age ≥18 who have had an inadequate response to ≥2 antidepressants, and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts or actions.¹ Since March 2019, we’ve been treating patients with intranasal esketamine. Based on our experiences, here is a summary of what we have learned.

REMS is required. Due to the potential risks resulting from sedation and dissociation caused by esketamine and the risk of abuse and misuse, esketamine is available only through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. The program links your office Drug Enforcement Administration number to the address where this schedule III medication will be stored and given to the patient for self-administration. Requirements and other details about the REMS are available at www.spravatorems.com.

Treatment. Start with the online REMS patient enrollment/consent form. Contraindications include having a history of aneurysmal vascular disease, intracerebral hemorrhage, or allergy to ketamine/esketamine. Adjunctive treatment with esketamine plus sertraline, escitalopram, venlafaxine, or duloxetine are comparably effective.¹ We have found that adding magnesium to block glutamate action at N-methyl-

Iatrogenic effects rarely lead to dropout. The first session is critical to allay anticipatory anxiety. Sedation, blood pressure increase, and dissociation are common but transient adverse effects that typically peak at 40 minutes and resolve by 90 minutes. Record blood pressure on a REMS monitoring form before treatment, at 40 minutes, and at 2 hours. Avoid administering sedative or prohypertensive medications together with esketamine.¹ Dissociation is more common in patients with a history of trauma. Combine music, guided imagery, or psychotherapy to harness this for therapeutic benefit. Sleepiness can last 4 hours; make sure the patient has arranged for a ride home, as they cannot drive until the next day. Verify normal blood pressure before starting treatment. Clonidine or labetalol for hypertension/severe dissociation and ondansetron or prochlorperazine for nausea are rarely needed. Advise patients to use the bathroom before treatment and keep a trash can nearby for vomiting. Other transient adverse effects found in TRD clinical trials that occurred >5% and twice that of placebo were dizziness, vertigo, numbness, and feeling drunk.¹

Reimbursement for treatment with esketamine is available through most insurances, including copay cards, rebates, deductible support, and free assistance programs. Coverage is either through pharmacy benefit, assignment of medical benefit (pharmacy handles the medical benefit), or medical benefit with remuneration above wholesale price.

Zeitgeist shift. Emergency departments are backlogged and patients languish waiting to feel the effects of oral antidepressants. Intranasal esketamine could help alleviate this situation by producing a more immediate response. We also have observed improvements in comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and in cognitive deficits of dementia, possibly due to rapidly enhanced neuroplasticity, neurogenesis, and astrocyte functioning, which NMDA receptor antagonism, AMPA activation, and downstream mediators (eg, brain-derived neurotrophic factor) may promote.4

1. Spravato (esketamine nasal spray) medication guide. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-patient-information/SPRAVATO-medication-guide.pdf

2. Spravato Healthcare Professional Website. TRD safety & efficacy. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.spravatohcp.com/trd-long-term/efficacy

3. Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed esketamine nasal spray combined with a newly initiated oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized double-blind active-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):428-438. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020172

4. Matveychuk D, Thomas RK, Swainson J, et al. Ketamine as an antidepressant: overview of its mechanisms of action and potential predictive biomarkers. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320916657. doi:10.1177/2045125320916657

Intranasal esketamine is an FDA-approved ketamine molecule indicated for use together with an oral antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in patients age ≥18 who have had an inadequate response to ≥2 antidepressants, and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts or actions.¹ Since March 2019, we’ve been treating patients with intranasal esketamine. Based on our experiences, here is a summary of what we have learned.

REMS is required. Due to the potential risks resulting from sedation and dissociation caused by esketamine and the risk of abuse and misuse, esketamine is available only through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. The program links your office Drug Enforcement Administration number to the address where this schedule III medication will be stored and given to the patient for self-administration. Requirements and other details about the REMS are available at www.spravatorems.com.

Treatment. Start with the online REMS patient enrollment/consent form. Contraindications include having a history of aneurysmal vascular disease, intracerebral hemorrhage, or allergy to ketamine/esketamine. Adjunctive treatment with esketamine plus sertraline, escitalopram, venlafaxine, or duloxetine are comparably effective.¹ We have found that adding magnesium to block glutamate action at N-methyl-

Iatrogenic effects rarely lead to dropout. The first session is critical to allay anticipatory anxiety. Sedation, blood pressure increase, and dissociation are common but transient adverse effects that typically peak at 40 minutes and resolve by 90 minutes. Record blood pressure on a REMS monitoring form before treatment, at 40 minutes, and at 2 hours. Avoid administering sedative or prohypertensive medications together with esketamine.¹ Dissociation is more common in patients with a history of trauma. Combine music, guided imagery, or psychotherapy to harness this for therapeutic benefit. Sleepiness can last 4 hours; make sure the patient has arranged for a ride home, as they cannot drive until the next day. Verify normal blood pressure before starting treatment. Clonidine or labetalol for hypertension/severe dissociation and ondansetron or prochlorperazine for nausea are rarely needed. Advise patients to use the bathroom before treatment and keep a trash can nearby for vomiting. Other transient adverse effects found in TRD clinical trials that occurred >5% and twice that of placebo were dizziness, vertigo, numbness, and feeling drunk.¹

Reimbursement for treatment with esketamine is available through most insurances, including copay cards, rebates, deductible support, and free assistance programs. Coverage is either through pharmacy benefit, assignment of medical benefit (pharmacy handles the medical benefit), or medical benefit with remuneration above wholesale price.

Zeitgeist shift. Emergency departments are backlogged and patients languish waiting to feel the effects of oral antidepressants. Intranasal esketamine could help alleviate this situation by producing a more immediate response. We also have observed improvements in comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and in cognitive deficits of dementia, possibly due to rapidly enhanced neuroplasticity, neurogenesis, and astrocyte functioning, which NMDA receptor antagonism, AMPA activation, and downstream mediators (eg, brain-derived neurotrophic factor) may promote.4

Intranasal esketamine is an FDA-approved ketamine molecule indicated for use together with an oral antidepressant for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in patients age ≥18 who have had an inadequate response to ≥2 antidepressants, and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts or actions.¹ Since March 2019, we’ve been treating patients with intranasal esketamine. Based on our experiences, here is a summary of what we have learned.

REMS is required. Due to the potential risks resulting from sedation and dissociation caused by esketamine and the risk of abuse and misuse, esketamine is available only through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. The program links your office Drug Enforcement Administration number to the address where this schedule III medication will be stored and given to the patient for self-administration. Requirements and other details about the REMS are available at www.spravatorems.com.

Treatment. Start with the online REMS patient enrollment/consent form. Contraindications include having a history of aneurysmal vascular disease, intracerebral hemorrhage, or allergy to ketamine/esketamine. Adjunctive treatment with esketamine plus sertraline, escitalopram, venlafaxine, or duloxetine are comparably effective.¹ We have found that adding magnesium to block glutamate action at N-methyl-

Iatrogenic effects rarely lead to dropout. The first session is critical to allay anticipatory anxiety. Sedation, blood pressure increase, and dissociation are common but transient adverse effects that typically peak at 40 minutes and resolve by 90 minutes. Record blood pressure on a REMS monitoring form before treatment, at 40 minutes, and at 2 hours. Avoid administering sedative or prohypertensive medications together with esketamine.¹ Dissociation is more common in patients with a history of trauma. Combine music, guided imagery, or psychotherapy to harness this for therapeutic benefit. Sleepiness can last 4 hours; make sure the patient has arranged for a ride home, as they cannot drive until the next day. Verify normal blood pressure before starting treatment. Clonidine or labetalol for hypertension/severe dissociation and ondansetron or prochlorperazine for nausea are rarely needed. Advise patients to use the bathroom before treatment and keep a trash can nearby for vomiting. Other transient adverse effects found in TRD clinical trials that occurred >5% and twice that of placebo were dizziness, vertigo, numbness, and feeling drunk.¹

Reimbursement for treatment with esketamine is available through most insurances, including copay cards, rebates, deductible support, and free assistance programs. Coverage is either through pharmacy benefit, assignment of medical benefit (pharmacy handles the medical benefit), or medical benefit with remuneration above wholesale price.

Zeitgeist shift. Emergency departments are backlogged and patients languish waiting to feel the effects of oral antidepressants. Intranasal esketamine could help alleviate this situation by producing a more immediate response. We also have observed improvements in comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and in cognitive deficits of dementia, possibly due to rapidly enhanced neuroplasticity, neurogenesis, and astrocyte functioning, which NMDA receptor antagonism, AMPA activation, and downstream mediators (eg, brain-derived neurotrophic factor) may promote.4

1. Spravato (esketamine nasal spray) medication guide. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-patient-information/SPRAVATO-medication-guide.pdf

2. Spravato Healthcare Professional Website. TRD safety & efficacy. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.spravatohcp.com/trd-long-term/efficacy

3. Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed esketamine nasal spray combined with a newly initiated oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized double-blind active-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):428-438. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020172

4. Matveychuk D, Thomas RK, Swainson J, et al. Ketamine as an antidepressant: overview of its mechanisms of action and potential predictive biomarkers. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320916657. doi:10.1177/2045125320916657

1. Spravato (esketamine nasal spray) medication guide. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-patient-information/SPRAVATO-medication-guide.pdf

2. Spravato Healthcare Professional Website. TRD safety & efficacy. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.spravatohcp.com/trd-long-term/efficacy

3. Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed esketamine nasal spray combined with a newly initiated oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized double-blind active-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):428-438. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020172

4. Matveychuk D, Thomas RK, Swainson J, et al. Ketamine as an antidepressant: overview of its mechanisms of action and potential predictive biomarkers. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320916657. doi:10.1177/2045125320916657

More on SWOT analysis, more

I enjoyed reading the optimistic outlook for psychiatry outlined in your SWOT analysis (“Contemporary psychiatry: A SWOT analysis,”

I think, though, you misplaced an opportunity as a threat in your assessment that the increase in the amount of advanced practice psychiatric nurses (PMHAPRNs) presents a threat to psychiatry. The presence of an increased number of PMHAPRNs provides access to a larger number of people needing treatment by qualified, skilled mental health professionals and an opportunity for psychiatrists to participate in highly effective teams of psychiatric clinicians. This workforce-building is of particular importance during our current clinician shortage, especially within psychiatry. Most research has shown that advanced practice nurses’ quality of care is competitive with that of physicians with similar experience, and that patient satisfaction is high. Advanced practice nurses are more likely than physicians to provide care in underserved populations and in rural communities. We are educated to practice independently within our scope, to standards established by our professional organizations as well as American Psychiatric Association (APA) clinical guidelines. I hope you will reconsider your view of your PMHAPRN colleagues as a threat and see them as a positive contribution to your chosen field of psychiatry, like the APA has shown in their choice of including a PMHAPRN as a clinical expert team member on the SMI Adviser initiative.

Stella Logan, APRN, PMHCNS-BC, PMHNP-BC

Austin, Texas

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thank you for your letter regarding my SWOT article. It was originally written for the newsletter of the Ohio Psychiatric Physicians Association, comprised of 1,000 psychiatrists. To them, nurse practitioners (NPs) are regarded as a threat because some mental health care systems have been laying off psychiatrists and hiring NPs to lower costs. This obviously is perceived as a threat. I do agree with you that well-qualified NPs are providing needed mental health services in underserved areas (eg, inner cities and rural areas), where it is very difficult to recruit psychiatrists due to the severe shortage nationally.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, DLFAPA

Editor-in-Chief

Continue to: More on the transdiagnostic model

More on the transdiagnostic model

I just had the pleasure of reading your February 2023 editorial (“Depression and schizophrenia: Many biological and clinical similarities,”

David Krassner, MD

Phoenix, Arizona

I completely agree with your promotion of a unified transdiagnostic model. All of this makes sense on the continuum of consciousness—restricted consciousness represents fear, whereas wide consciousness represents complete connectivity (love in the spiritual sense). Therefore, a threat not resolved can lead to defeat and an unresolved painful defeat can lead to a psychotic projection. Is it no surprise, then, that a medication such as quetiapine can treat the whole continuum from anxiety at low doses to psychosis at high doses?

Mike Primc, MD

Chardon, Ohio

I enjoyed reading the optimistic outlook for psychiatry outlined in your SWOT analysis (“Contemporary psychiatry: A SWOT analysis,”

I think, though, you misplaced an opportunity as a threat in your assessment that the increase in the amount of advanced practice psychiatric nurses (PMHAPRNs) presents a threat to psychiatry. The presence of an increased number of PMHAPRNs provides access to a larger number of people needing treatment by qualified, skilled mental health professionals and an opportunity for psychiatrists to participate in highly effective teams of psychiatric clinicians. This workforce-building is of particular importance during our current clinician shortage, especially within psychiatry. Most research has shown that advanced practice nurses’ quality of care is competitive with that of physicians with similar experience, and that patient satisfaction is high. Advanced practice nurses are more likely than physicians to provide care in underserved populations and in rural communities. We are educated to practice independently within our scope, to standards established by our professional organizations as well as American Psychiatric Association (APA) clinical guidelines. I hope you will reconsider your view of your PMHAPRN colleagues as a threat and see them as a positive contribution to your chosen field of psychiatry, like the APA has shown in their choice of including a PMHAPRN as a clinical expert team member on the SMI Adviser initiative.

Stella Logan, APRN, PMHCNS-BC, PMHNP-BC

Austin, Texas

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thank you for your letter regarding my SWOT article. It was originally written for the newsletter of the Ohio Psychiatric Physicians Association, comprised of 1,000 psychiatrists. To them, nurse practitioners (NPs) are regarded as a threat because some mental health care systems have been laying off psychiatrists and hiring NPs to lower costs. This obviously is perceived as a threat. I do agree with you that well-qualified NPs are providing needed mental health services in underserved areas (eg, inner cities and rural areas), where it is very difficult to recruit psychiatrists due to the severe shortage nationally.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, DLFAPA

Editor-in-Chief

Continue to: More on the transdiagnostic model

More on the transdiagnostic model

I just had the pleasure of reading your February 2023 editorial (“Depression and schizophrenia: Many biological and clinical similarities,”

David Krassner, MD

Phoenix, Arizona

I completely agree with your promotion of a unified transdiagnostic model. All of this makes sense on the continuum of consciousness—restricted consciousness represents fear, whereas wide consciousness represents complete connectivity (love in the spiritual sense). Therefore, a threat not resolved can lead to defeat and an unresolved painful defeat can lead to a psychotic projection. Is it no surprise, then, that a medication such as quetiapine can treat the whole continuum from anxiety at low doses to psychosis at high doses?

Mike Primc, MD

Chardon, Ohio

I enjoyed reading the optimistic outlook for psychiatry outlined in your SWOT analysis (“Contemporary psychiatry: A SWOT analysis,”

I think, though, you misplaced an opportunity as a threat in your assessment that the increase in the amount of advanced practice psychiatric nurses (PMHAPRNs) presents a threat to psychiatry. The presence of an increased number of PMHAPRNs provides access to a larger number of people needing treatment by qualified, skilled mental health professionals and an opportunity for psychiatrists to participate in highly effective teams of psychiatric clinicians. This workforce-building is of particular importance during our current clinician shortage, especially within psychiatry. Most research has shown that advanced practice nurses’ quality of care is competitive with that of physicians with similar experience, and that patient satisfaction is high. Advanced practice nurses are more likely than physicians to provide care in underserved populations and in rural communities. We are educated to practice independently within our scope, to standards established by our professional organizations as well as American Psychiatric Association (APA) clinical guidelines. I hope you will reconsider your view of your PMHAPRN colleagues as a threat and see them as a positive contribution to your chosen field of psychiatry, like the APA has shown in their choice of including a PMHAPRN as a clinical expert team member on the SMI Adviser initiative.

Stella Logan, APRN, PMHCNS-BC, PMHNP-BC

Austin, Texas

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thank you for your letter regarding my SWOT article. It was originally written for the newsletter of the Ohio Psychiatric Physicians Association, comprised of 1,000 psychiatrists. To them, nurse practitioners (NPs) are regarded as a threat because some mental health care systems have been laying off psychiatrists and hiring NPs to lower costs. This obviously is perceived as a threat. I do agree with you that well-qualified NPs are providing needed mental health services in underserved areas (eg, inner cities and rural areas), where it is very difficult to recruit psychiatrists due to the severe shortage nationally.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, DLFAPA

Editor-in-Chief

Continue to: More on the transdiagnostic model

More on the transdiagnostic model

I just had the pleasure of reading your February 2023 editorial (“Depression and schizophrenia: Many biological and clinical similarities,”

David Krassner, MD

Phoenix, Arizona

I completely agree with your promotion of a unified transdiagnostic model. All of this makes sense on the continuum of consciousness—restricted consciousness represents fear, whereas wide consciousness represents complete connectivity (love in the spiritual sense). Therefore, a threat not resolved can lead to defeat and an unresolved painful defeat can lead to a psychotic projection. Is it no surprise, then, that a medication such as quetiapine can treat the whole continuum from anxiety at low doses to psychosis at high doses?

Mike Primc, MD

Chardon, Ohio

2023 Update on fertility

Total fertility rate and fertility care: Demographic shifts and changing demands

Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;396:1285-1306.

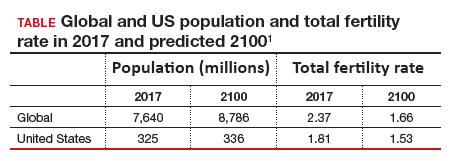

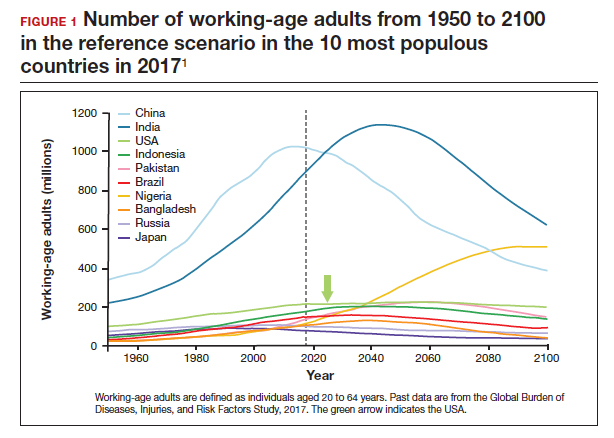

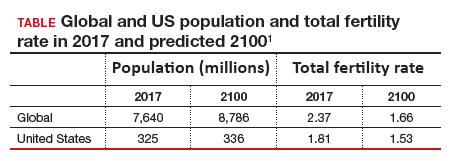

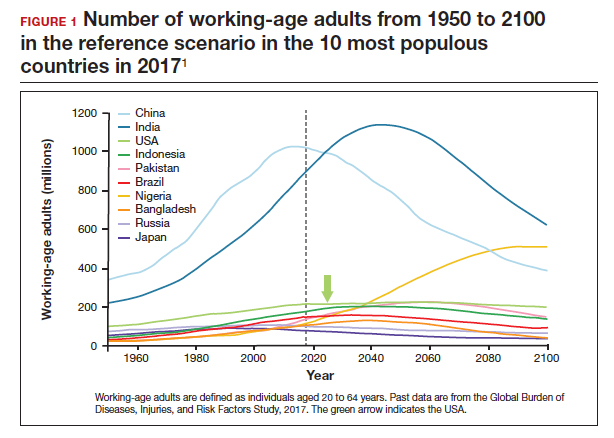

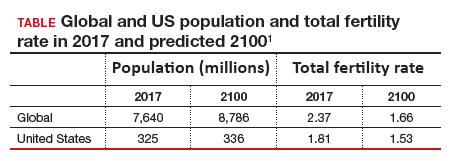

The total fertility rate (TFR) globally is decreasing rapidly, and in the United States it is now 1.8 births per woman, well below the required replacement rate of 2.1 that maintains the population.1 These reduced TFRs result in significant demographic shifts that affect the economy, workforce, society, health care needs, environment, and geopolitical standing of every country. These changes also will shift demands for the volume and type of services delivered by women’s health care clinicians.

In addition to the TFR, mortality rates and migration rates play essential roles in determining a country’s population.2 Anticipation and planning for these population and health care service changes by each country’s government, business, professionals, and other stakeholders are imperative to manage their impact and optimize quality of life.

US standings in projected population and economic growth

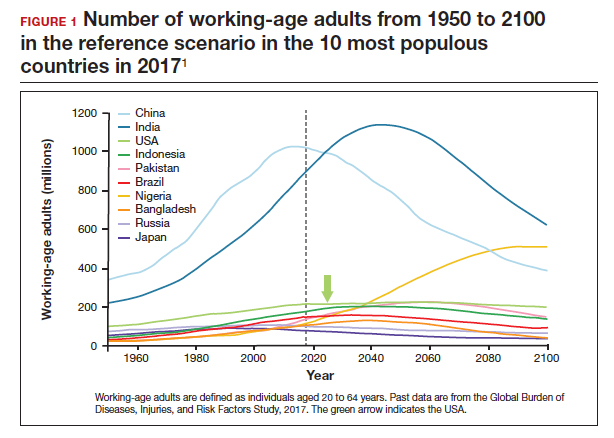

The US population is predicted to peak at 364 million in 2062 and decrease to 336 million in 2100, at which time it will be the fourth largest country in the world, according to a forecasting analysis by Vollset and colleagues.1 China is expected to become the biggest economy in the world in 2035, but this is predicted to change because of its decreasing population so that by 2098 the United States will again be the country with the largest economy (FIGURE 1).1

For the United States to maintain its economic and geopolitical standing, it is important to have policies that promote families. Other countries, especially in northern Europe, have implemented such policies. These include education of the population,economic incentives to create families, extended day care, and favorable tax policies.3 They also include increased access to family-forming fertility care. Such policies in Denmark have resulted in approximately 10% of all children being born from assisted reproductive technology (ART), compared with about 1.5% in the United States. Other countries have similar policies and success in increasing the number of children born from ART.

In the United States, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), RESOLVE: the National Infertility Association, the American Medical Women’s Association (AMWA), and others are promoting the need for increased access to fertility care and family-forming resources, primarily through family-forming benefits provided by companies.4 Such benefits are critical since the primary reason most people do not undergo fertility care is a lack of affordability. Only 1 person in 4 in the United States who needs fertility care receives treatment. Increased access would result in more babies being born to help address the reduced TFR.

Educational access, contraceptive goals, and access to fertility care

Continued trends in women’s educational attainment and access to contraception will hasten declines in the fertility rate and slow population growth (TABLE).1 These educational and contraceptive goals also must be pursued so that every person can achieve their individual reproductive life goals of having a family if and when they want to have a family. In addition to helping address the decreasing TFR, there is a fundamental right to found a family, as stated in the United Nations charter. It is a matter of social justice and equity that everyone who wants to have a family can access reproductive care on a nondiscriminatory basis when needed.

While the need for more and better insurance coverage for infertility has been well documented for many years, the decreasing TFR in the United States is an additional compelling reason that government, business, and other stakeholders should continue to increase access to fertility benefits and care. Women’s health care clinicians are encouraged to support these initiatives that also improve quality of life, equity, and social justice.

The decreasing global and US total fertility rate causes significant demographic changes, with major socioeconomic and health care consequences. The reduced TFR impacts women’s health care services, including the need for increased access to fertility care. Government and corporate policies, including those that improve access to fertility care, will help society adapt to these changes.

Continue to: A new comprehensive ovulatory disorders classification system developed by FIGO...

A new comprehensive ovulatory disorders classification system developed by FIGO

Munro MG, Balen AH, Cho S, et al; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:768-786.

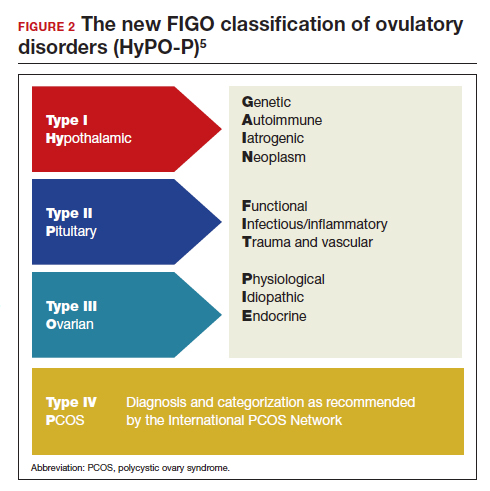

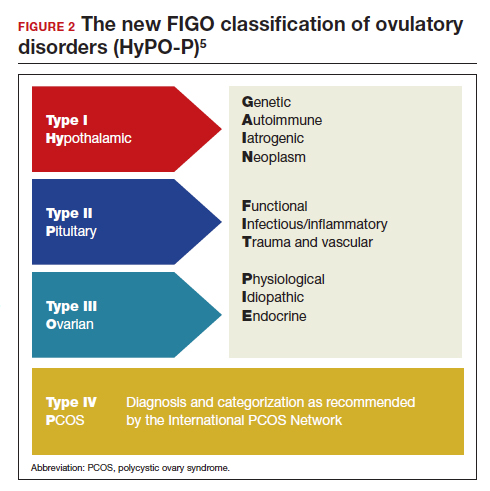

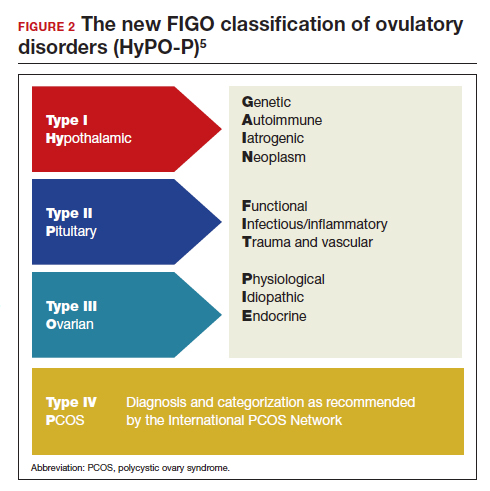

Ovulatory disorders are well-recognized and common causes of infertility and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). Ovulatory disorders occur on a spectrum, with the most severe form being anovulation, and comprise a heterogeneous group that has been classically categorized based on an initial monograph published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1973. That classification was based on gonadotropin levels and categorized these disorders into 3 groups: 1) hypogonadotropic (such as hypothalamic amenorrhea), 2) eugonadotropic (such as polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]), and 3) hypergonadotropic (such as primary ovarian insufficiency). This initial classification was the subject of several subsequent iterations and modifications over the past 50 years; for example, at one point, ovulatory disorder caused by hyperprolactinemia was added as a separate fourth category. However, due to advances in endocrine assays, imaging technology, and genetics, our understanding of ovulatory disorders has expanded remarkably over the past several decades.

Previous FIGO classifications

Considering the emergent complexity of these disorders and the limitations of the original WHO classification to capture these subtleties adequately, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) recently developed and published a new classification system for ovulatory disorders.5 This new system was designed using a meticulously followed Delphi process with inputs from a diverse group of national and international professional organizations, subspecialty societies, specialty journals, recognized experts in the field, and lay individuals interested in the subject matter.

Of note, FIGO had previously published classification systems for nongestational normal and abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years (FIGO AUB System 1),as well as a subsequent classification system that described potential causes of AUB symptoms (FIGO AUB System 2), with the 9 categories arranged under the acronym PALM-COEIN (Polyp, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, Malignancy–Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial disorders, Iatrogenic, and Not otherwise classified). This new FIGO classification of ovulatory disorders can be viewed as a continuation of the previous initiatives and aims to further categorize the subgroup of AUB-O (AUB with ovulatory disorders). However, it is important to recognize that while most ovulatory disorders manifest with the symptoms of AUB, the absence of AUB symptoms does not necessarily preclude ovulatory disorders.

New system uses a 3-tier approach

The new FIGO classification system for ovulatory disorders has adopted a 3-tier system.

The first tier is based on the anatomic components of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis and is referred to with the acronym HyPO, for Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian. Recognizing that PCOS refers to a distinct spectrum of conditions that share a variable combination of signs and symptoms caused to varying degrees by different pathophysiologic mechanisms that involve inherent ovarian follicular dysfunction, neuroendocrine dysfunction, insulin resistance, and androgen excess, it is categorized in a separate class of its own in the first tier, referred to with the letter P.

Adding PCOS to the anatomical categories referred to by HyPO, the first tier is overall referred to with the acronym HyPO-P (FIGURE 2).5

The second tier of stratification provides further etiologic details for any of the primary 3 anatomic classifications of hypothalamic, pituitary, and ovarian. These etiologies are arranged in 10 distinct groups under the mnemonic GAIN-FIT-PIE, which stands for Genetic, Autoimmune, Iatrogenic, Neoplasm; Functional, Infectious/inflammatory, Trauma and vascular; and Physiological, Idiopathic, Endocrine.

The third tier of the system refers to the specific clinical diagnosis. For example, an individual with Kallmann syndrome would be categorized as having type I (hypothalamic), Genetic, Kallmann syndrome, and an individual with PCOS would be categorized simply as having type IV, PCOS.

Our understanding of the etiology of ovulatory disorders has substantially increased over the past several decades. This progress has prompted the need to develop a more comprehensive classification system for these disorders. FIGO recently published a 3-tier classification system for ovulatory disorders that can be remembered with 2 mnemonics: HyPO-P and GAIN-FIT-PIE.

It is hoped that widespread adoption of this new classification system results in better and more concise communication between clinicians, researchers, and patients, ultimately leading to continued improvement in our understanding of the pathophysiology and management of ovulatory disorders.

Continue to: Live birth rate with conventional IVF shown noninferior to that with PGT-A...

Live birth rate with conventional IVF shown noninferior to that with PGT-A

Yan J, Qin Y, Zhao H, et al. Live birth with or without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2047-2058.

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) is increasingly used in many in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles in the United States. Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 43.8% of embryo transfers in the United States in 2019 included at least 1 PGT-A–tested embryo.6 Despite this widespread use, however, there are still no robust clinical data for PGT-A’s efficacy and safety, and the guidelines published by the ASRM do not recommend its routine use in all IVF cycles.7 In the past 2 to 3 years, several large studies have raised questions about the reported benefit of this technology.8,9

Details of the trial

In a multicenter, controlled, noninferiority trial conducted by Yan and colleagues, 1,212 subfertile women were randomly assigned to either conventional IVF with embryo selection based on morphology or embryo selection based on PGT-A with next-generation sequencing. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of subfertility, undergoing their first IVF cycle, female age of 20 to 37, and the availability of 3 or more good-quality blastocysts.

On day 5 of embryo culture, patients with 3 or more blastocysts were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the PGT-A group or conventional IVF. All embryos were then frozen, and patients subsequently underwent frozen embryo transfer of a single blastocyst, selected based on either morphology or euploid result by PGT-A. If the initial transfer did not result in a live birth, and there were remaining transferable embryos (either a euploid embryo in the PGT-A group or a morphologically transferable embryo in the conventional IVF group), patients underwent successive frozen embryo transfers until either there was a live birth or no more embryos were available for transfer.

The study’s primary outcome was the cumulative live birth rate per randomly assigned patient that resulted from up to 3 frozen embryo transfer cycles within 1 year. There were 606 patients randomly assigned to the PGT-A group and 606 randomly assigned to the conventional IVF group.

In the PGT-A group, 468 women (77.2%) had live births; in the conventional IVF group, 496 women (81.8%) had live births. Women in the PGT-A group had a lower incidence of pregnancy loss compared with the conventional IVF group: 8.7% versus 12.6% (absolute difference of -3.9%; 95% confidence interval [CI], -7.5 to -0.2). There was no difference in obstetric and neonatal outcomes between the 2 groups. The authors concluded that among women with 3 or more good-quality blastocysts, conventional IVF resulted in a cumulative live birth rate that was noninferior to that of the PGT-A group.

Some benefit shown with PGT-A

Although the study by Yan and colleagues did not show any benefit, and even a possible reduction, with regard to cumulative live birth rate for PGT-A, it did show a 4% reduction in clinical pregnancy loss when PGT-A was used. Furthermore, the study design has been criticized for performing PGT-A on only 3 blastocysts in the PGT-A group. It is quite conceivable that the PGT-A group would have had more euploid embryos available for transfer if the study design had included all the available embryos instead of only 3. On the other hand, one could argue that if the authors had extended the study to include all the available embryos, the conventional group would have also had more embryos for transfer and, therefore, more chances for pregnancy and live birth.

It is also important to recognize that only patients who had at least 3 embryos available for biopsy were included in this study, and therefore the results of this study cannot be extended to patients with fewer embryos, such as those with diminished ovarian reserve.

In summary, based on this study’s results, we may conclude that for the good-prognosis patients in the age group of 20 to 37 who have at least 3 embryos available for biopsy, PGT-A may reduce the miscarriage rate by about 4%, but this benefit comes at the expense of about a 4% reduction in the cumulative live birth rate. ●

Despite the lack of robust evidence for efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness, PGT-A has been widely adopted into clinical IVF practice in the United States over the past several years. A large randomized controlled trial has suggested that, compared with conventional IVF, PGT-A application may actually result in a slightly lower cumulative live birth rate, while the miscarriage rate may be slightly higher with conventional IVF.

PGT-A is a novel and evolving technology with the potential to improve embryo selection in IVF; however, at this juncture, there is not enough clinical data for its universal and routine use in all IVF cycles. PGT-A can potentially be more helpful in older women (>38–40) with good ovarian reserve who are likely to have a larger cohort of embryos to select from. Patients must clearly understand this technology’s pros and cons before agreeing to incorporate it into their care plan.

- Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;396:1285-1306.

- Dao TH, Docquier F, Maurel M, et al. Global migration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: the unstoppable force of demography. Rev World Econ. 2021;157:417-449.

- Atlas of fertility treatment policies in Europe. December 2021. Fertility Europe. Accessed December 29, 2022. https:// fertilityeurope.eu/atlas/#:~:text=Fertility%20Europe%20 in%20conjunction%20with%20the%20European%20 Parliamentary,The%20Atlas%20describes%20the%20 current%20situation%20in%202021

- AMWA’s physician fertility initiative. June 2021. American Medical Women’s Association. Accessed December 29, 2022. https://www.amwa-doc.org/our-work/initiatives/physician -infertility/

- Munro MG, Balen AH, Cho S, et al; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:768-786.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Assisted Reproductive Technology Fertility Clinic and National Summary Report. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/art /reports/2019/fertility-clinic.html

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. The use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:429-436.

- Yan J, Qin Y, Zhao H, et al. Live birth with or without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2047-2058.

- Kucherov A, Fazzari M, Lieman H, et al. PGT-A is associated with reduced cumulative live birth rate in first reported IVF stimulation cycles age ≤ 40: an analysis of 133,494 autologous cycles reported to SART CORS. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2023;40:137-149.

Total fertility rate and fertility care: Demographic shifts and changing demands

Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;396:1285-1306.

The total fertility rate (TFR) globally is decreasing rapidly, and in the United States it is now 1.8 births per woman, well below the required replacement rate of 2.1 that maintains the population.1 These reduced TFRs result in significant demographic shifts that affect the economy, workforce, society, health care needs, environment, and geopolitical standing of every country. These changes also will shift demands for the volume and type of services delivered by women’s health care clinicians.

In addition to the TFR, mortality rates and migration rates play essential roles in determining a country’s population.2 Anticipation and planning for these population and health care service changes by each country’s government, business, professionals, and other stakeholders are imperative to manage their impact and optimize quality of life.

US standings in projected population and economic growth

The US population is predicted to peak at 364 million in 2062 and decrease to 336 million in 2100, at which time it will be the fourth largest country in the world, according to a forecasting analysis by Vollset and colleagues.1 China is expected to become the biggest economy in the world in 2035, but this is predicted to change because of its decreasing population so that by 2098 the United States will again be the country with the largest economy (FIGURE 1).1

For the United States to maintain its economic and geopolitical standing, it is important to have policies that promote families. Other countries, especially in northern Europe, have implemented such policies. These include education of the population,economic incentives to create families, extended day care, and favorable tax policies.3 They also include increased access to family-forming fertility care. Such policies in Denmark have resulted in approximately 10% of all children being born from assisted reproductive technology (ART), compared with about 1.5% in the United States. Other countries have similar policies and success in increasing the number of children born from ART.

In the United States, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), RESOLVE: the National Infertility Association, the American Medical Women’s Association (AMWA), and others are promoting the need for increased access to fertility care and family-forming resources, primarily through family-forming benefits provided by companies.4 Such benefits are critical since the primary reason most people do not undergo fertility care is a lack of affordability. Only 1 person in 4 in the United States who needs fertility care receives treatment. Increased access would result in more babies being born to help address the reduced TFR.

Educational access, contraceptive goals, and access to fertility care

Continued trends in women’s educational attainment and access to contraception will hasten declines in the fertility rate and slow population growth (TABLE).1 These educational and contraceptive goals also must be pursued so that every person can achieve their individual reproductive life goals of having a family if and when they want to have a family. In addition to helping address the decreasing TFR, there is a fundamental right to found a family, as stated in the United Nations charter. It is a matter of social justice and equity that everyone who wants to have a family can access reproductive care on a nondiscriminatory basis when needed.

While the need for more and better insurance coverage for infertility has been well documented for many years, the decreasing TFR in the United States is an additional compelling reason that government, business, and other stakeholders should continue to increase access to fertility benefits and care. Women’s health care clinicians are encouraged to support these initiatives that also improve quality of life, equity, and social justice.

The decreasing global and US total fertility rate causes significant demographic changes, with major socioeconomic and health care consequences. The reduced TFR impacts women’s health care services, including the need for increased access to fertility care. Government and corporate policies, including those that improve access to fertility care, will help society adapt to these changes.

Continue to: A new comprehensive ovulatory disorders classification system developed by FIGO...

A new comprehensive ovulatory disorders classification system developed by FIGO

Munro MG, Balen AH, Cho S, et al; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:768-786.

Ovulatory disorders are well-recognized and common causes of infertility and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). Ovulatory disorders occur on a spectrum, with the most severe form being anovulation, and comprise a heterogeneous group that has been classically categorized based on an initial monograph published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1973. That classification was based on gonadotropin levels and categorized these disorders into 3 groups: 1) hypogonadotropic (such as hypothalamic amenorrhea), 2) eugonadotropic (such as polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]), and 3) hypergonadotropic (such as primary ovarian insufficiency). This initial classification was the subject of several subsequent iterations and modifications over the past 50 years; for example, at one point, ovulatory disorder caused by hyperprolactinemia was added as a separate fourth category. However, due to advances in endocrine assays, imaging technology, and genetics, our understanding of ovulatory disorders has expanded remarkably over the past several decades.

Previous FIGO classifications

Considering the emergent complexity of these disorders and the limitations of the original WHO classification to capture these subtleties adequately, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) recently developed and published a new classification system for ovulatory disorders.5 This new system was designed using a meticulously followed Delphi process with inputs from a diverse group of national and international professional organizations, subspecialty societies, specialty journals, recognized experts in the field, and lay individuals interested in the subject matter.

Of note, FIGO had previously published classification systems for nongestational normal and abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years (FIGO AUB System 1),as well as a subsequent classification system that described potential causes of AUB symptoms (FIGO AUB System 2), with the 9 categories arranged under the acronym PALM-COEIN (Polyp, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, Malignancy–Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial disorders, Iatrogenic, and Not otherwise classified). This new FIGO classification of ovulatory disorders can be viewed as a continuation of the previous initiatives and aims to further categorize the subgroup of AUB-O (AUB with ovulatory disorders). However, it is important to recognize that while most ovulatory disorders manifest with the symptoms of AUB, the absence of AUB symptoms does not necessarily preclude ovulatory disorders.

New system uses a 3-tier approach

The new FIGO classification system for ovulatory disorders has adopted a 3-tier system.

The first tier is based on the anatomic components of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis and is referred to with the acronym HyPO, for Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian. Recognizing that PCOS refers to a distinct spectrum of conditions that share a variable combination of signs and symptoms caused to varying degrees by different pathophysiologic mechanisms that involve inherent ovarian follicular dysfunction, neuroendocrine dysfunction, insulin resistance, and androgen excess, it is categorized in a separate class of its own in the first tier, referred to with the letter P.

Adding PCOS to the anatomical categories referred to by HyPO, the first tier is overall referred to with the acronym HyPO-P (FIGURE 2).5

The second tier of stratification provides further etiologic details for any of the primary 3 anatomic classifications of hypothalamic, pituitary, and ovarian. These etiologies are arranged in 10 distinct groups under the mnemonic GAIN-FIT-PIE, which stands for Genetic, Autoimmune, Iatrogenic, Neoplasm; Functional, Infectious/inflammatory, Trauma and vascular; and Physiological, Idiopathic, Endocrine.

The third tier of the system refers to the specific clinical diagnosis. For example, an individual with Kallmann syndrome would be categorized as having type I (hypothalamic), Genetic, Kallmann syndrome, and an individual with PCOS would be categorized simply as having type IV, PCOS.

Our understanding of the etiology of ovulatory disorders has substantially increased over the past several decades. This progress has prompted the need to develop a more comprehensive classification system for these disorders. FIGO recently published a 3-tier classification system for ovulatory disorders that can be remembered with 2 mnemonics: HyPO-P and GAIN-FIT-PIE.

It is hoped that widespread adoption of this new classification system results in better and more concise communication between clinicians, researchers, and patients, ultimately leading to continued improvement in our understanding of the pathophysiology and management of ovulatory disorders.

Continue to: Live birth rate with conventional IVF shown noninferior to that with PGT-A...

Live birth rate with conventional IVF shown noninferior to that with PGT-A

Yan J, Qin Y, Zhao H, et al. Live birth with or without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2047-2058.

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) is increasingly used in many in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles in the United States. Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 43.8% of embryo transfers in the United States in 2019 included at least 1 PGT-A–tested embryo.6 Despite this widespread use, however, there are still no robust clinical data for PGT-A’s efficacy and safety, and the guidelines published by the ASRM do not recommend its routine use in all IVF cycles.7 In the past 2 to 3 years, several large studies have raised questions about the reported benefit of this technology.8,9

Details of the trial

In a multicenter, controlled, noninferiority trial conducted by Yan and colleagues, 1,212 subfertile women were randomly assigned to either conventional IVF with embryo selection based on morphology or embryo selection based on PGT-A with next-generation sequencing. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of subfertility, undergoing their first IVF cycle, female age of 20 to 37, and the availability of 3 or more good-quality blastocysts.

On day 5 of embryo culture, patients with 3 or more blastocysts were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the PGT-A group or conventional IVF. All embryos were then frozen, and patients subsequently underwent frozen embryo transfer of a single blastocyst, selected based on either morphology or euploid result by PGT-A. If the initial transfer did not result in a live birth, and there were remaining transferable embryos (either a euploid embryo in the PGT-A group or a morphologically transferable embryo in the conventional IVF group), patients underwent successive frozen embryo transfers until either there was a live birth or no more embryos were available for transfer.

The study’s primary outcome was the cumulative live birth rate per randomly assigned patient that resulted from up to 3 frozen embryo transfer cycles within 1 year. There were 606 patients randomly assigned to the PGT-A group and 606 randomly assigned to the conventional IVF group.

In the PGT-A group, 468 women (77.2%) had live births; in the conventional IVF group, 496 women (81.8%) had live births. Women in the PGT-A group had a lower incidence of pregnancy loss compared with the conventional IVF group: 8.7% versus 12.6% (absolute difference of -3.9%; 95% confidence interval [CI], -7.5 to -0.2). There was no difference in obstetric and neonatal outcomes between the 2 groups. The authors concluded that among women with 3 or more good-quality blastocysts, conventional IVF resulted in a cumulative live birth rate that was noninferior to that of the PGT-A group.

Some benefit shown with PGT-A

Although the study by Yan and colleagues did not show any benefit, and even a possible reduction, with regard to cumulative live birth rate for PGT-A, it did show a 4% reduction in clinical pregnancy loss when PGT-A was used. Furthermore, the study design has been criticized for performing PGT-A on only 3 blastocysts in the PGT-A group. It is quite conceivable that the PGT-A group would have had more euploid embryos available for transfer if the study design had included all the available embryos instead of only 3. On the other hand, one could argue that if the authors had extended the study to include all the available embryos, the conventional group would have also had more embryos for transfer and, therefore, more chances for pregnancy and live birth.

It is also important to recognize that only patients who had at least 3 embryos available for biopsy were included in this study, and therefore the results of this study cannot be extended to patients with fewer embryos, such as those with diminished ovarian reserve.

In summary, based on this study’s results, we may conclude that for the good-prognosis patients in the age group of 20 to 37 who have at least 3 embryos available for biopsy, PGT-A may reduce the miscarriage rate by about 4%, but this benefit comes at the expense of about a 4% reduction in the cumulative live birth rate. ●

Despite the lack of robust evidence for efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness, PGT-A has been widely adopted into clinical IVF practice in the United States over the past several years. A large randomized controlled trial has suggested that, compared with conventional IVF, PGT-A application may actually result in a slightly lower cumulative live birth rate, while the miscarriage rate may be slightly higher with conventional IVF.

PGT-A is a novel and evolving technology with the potential to improve embryo selection in IVF; however, at this juncture, there is not enough clinical data for its universal and routine use in all IVF cycles. PGT-A can potentially be more helpful in older women (>38–40) with good ovarian reserve who are likely to have a larger cohort of embryos to select from. Patients must clearly understand this technology’s pros and cons before agreeing to incorporate it into their care plan.

Total fertility rate and fertility care: Demographic shifts and changing demands

Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;396:1285-1306.

The total fertility rate (TFR) globally is decreasing rapidly, and in the United States it is now 1.8 births per woman, well below the required replacement rate of 2.1 that maintains the population.1 These reduced TFRs result in significant demographic shifts that affect the economy, workforce, society, health care needs, environment, and geopolitical standing of every country. These changes also will shift demands for the volume and type of services delivered by women’s health care clinicians.

In addition to the TFR, mortality rates and migration rates play essential roles in determining a country’s population.2 Anticipation and planning for these population and health care service changes by each country’s government, business, professionals, and other stakeholders are imperative to manage their impact and optimize quality of life.

US standings in projected population and economic growth

The US population is predicted to peak at 364 million in 2062 and decrease to 336 million in 2100, at which time it will be the fourth largest country in the world, according to a forecasting analysis by Vollset and colleagues.1 China is expected to become the biggest economy in the world in 2035, but this is predicted to change because of its decreasing population so that by 2098 the United States will again be the country with the largest economy (FIGURE 1).1

For the United States to maintain its economic and geopolitical standing, it is important to have policies that promote families. Other countries, especially in northern Europe, have implemented such policies. These include education of the population,economic incentives to create families, extended day care, and favorable tax policies.3 They also include increased access to family-forming fertility care. Such policies in Denmark have resulted in approximately 10% of all children being born from assisted reproductive technology (ART), compared with about 1.5% in the United States. Other countries have similar policies and success in increasing the number of children born from ART.

In the United States, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), RESOLVE: the National Infertility Association, the American Medical Women’s Association (AMWA), and others are promoting the need for increased access to fertility care and family-forming resources, primarily through family-forming benefits provided by companies.4 Such benefits are critical since the primary reason most people do not undergo fertility care is a lack of affordability. Only 1 person in 4 in the United States who needs fertility care receives treatment. Increased access would result in more babies being born to help address the reduced TFR.

Educational access, contraceptive goals, and access to fertility care

Continued trends in women’s educational attainment and access to contraception will hasten declines in the fertility rate and slow population growth (TABLE).1 These educational and contraceptive goals also must be pursued so that every person can achieve their individual reproductive life goals of having a family if and when they want to have a family. In addition to helping address the decreasing TFR, there is a fundamental right to found a family, as stated in the United Nations charter. It is a matter of social justice and equity that everyone who wants to have a family can access reproductive care on a nondiscriminatory basis when needed.

While the need for more and better insurance coverage for infertility has been well documented for many years, the decreasing TFR in the United States is an additional compelling reason that government, business, and other stakeholders should continue to increase access to fertility benefits and care. Women’s health care clinicians are encouraged to support these initiatives that also improve quality of life, equity, and social justice.

The decreasing global and US total fertility rate causes significant demographic changes, with major socioeconomic and health care consequences. The reduced TFR impacts women’s health care services, including the need for increased access to fertility care. Government and corporate policies, including those that improve access to fertility care, will help society adapt to these changes.

Continue to: A new comprehensive ovulatory disorders classification system developed by FIGO...

A new comprehensive ovulatory disorders classification system developed by FIGO

Munro MG, Balen AH, Cho S, et al; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:768-786.

Ovulatory disorders are well-recognized and common causes of infertility and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). Ovulatory disorders occur on a spectrum, with the most severe form being anovulation, and comprise a heterogeneous group that has been classically categorized based on an initial monograph published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1973. That classification was based on gonadotropin levels and categorized these disorders into 3 groups: 1) hypogonadotropic (such as hypothalamic amenorrhea), 2) eugonadotropic (such as polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]), and 3) hypergonadotropic (such as primary ovarian insufficiency). This initial classification was the subject of several subsequent iterations and modifications over the past 50 years; for example, at one point, ovulatory disorder caused by hyperprolactinemia was added as a separate fourth category. However, due to advances in endocrine assays, imaging technology, and genetics, our understanding of ovulatory disorders has expanded remarkably over the past several decades.

Previous FIGO classifications

Considering the emergent complexity of these disorders and the limitations of the original WHO classification to capture these subtleties adequately, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) recently developed and published a new classification system for ovulatory disorders.5 This new system was designed using a meticulously followed Delphi process with inputs from a diverse group of national and international professional organizations, subspecialty societies, specialty journals, recognized experts in the field, and lay individuals interested in the subject matter.

Of note, FIGO had previously published classification systems for nongestational normal and abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years (FIGO AUB System 1),as well as a subsequent classification system that described potential causes of AUB symptoms (FIGO AUB System 2), with the 9 categories arranged under the acronym PALM-COEIN (Polyp, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, Malignancy–Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial disorders, Iatrogenic, and Not otherwise classified). This new FIGO classification of ovulatory disorders can be viewed as a continuation of the previous initiatives and aims to further categorize the subgroup of AUB-O (AUB with ovulatory disorders). However, it is important to recognize that while most ovulatory disorders manifest with the symptoms of AUB, the absence of AUB symptoms does not necessarily preclude ovulatory disorders.

New system uses a 3-tier approach

The new FIGO classification system for ovulatory disorders has adopted a 3-tier system.

The first tier is based on the anatomic components of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis and is referred to with the acronym HyPO, for Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian. Recognizing that PCOS refers to a distinct spectrum of conditions that share a variable combination of signs and symptoms caused to varying degrees by different pathophysiologic mechanisms that involve inherent ovarian follicular dysfunction, neuroendocrine dysfunction, insulin resistance, and androgen excess, it is categorized in a separate class of its own in the first tier, referred to with the letter P.

Adding PCOS to the anatomical categories referred to by HyPO, the first tier is overall referred to with the acronym HyPO-P (FIGURE 2).5

The second tier of stratification provides further etiologic details for any of the primary 3 anatomic classifications of hypothalamic, pituitary, and ovarian. These etiologies are arranged in 10 distinct groups under the mnemonic GAIN-FIT-PIE, which stands for Genetic, Autoimmune, Iatrogenic, Neoplasm; Functional, Infectious/inflammatory, Trauma and vascular; and Physiological, Idiopathic, Endocrine.

The third tier of the system refers to the specific clinical diagnosis. For example, an individual with Kallmann syndrome would be categorized as having type I (hypothalamic), Genetic, Kallmann syndrome, and an individual with PCOS would be categorized simply as having type IV, PCOS.

Our understanding of the etiology of ovulatory disorders has substantially increased over the past several decades. This progress has prompted the need to develop a more comprehensive classification system for these disorders. FIGO recently published a 3-tier classification system for ovulatory disorders that can be remembered with 2 mnemonics: HyPO-P and GAIN-FIT-PIE.

It is hoped that widespread adoption of this new classification system results in better and more concise communication between clinicians, researchers, and patients, ultimately leading to continued improvement in our understanding of the pathophysiology and management of ovulatory disorders.

Continue to: Live birth rate with conventional IVF shown noninferior to that with PGT-A...

Live birth rate with conventional IVF shown noninferior to that with PGT-A

Yan J, Qin Y, Zhao H, et al. Live birth with or without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2047-2058.

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) is increasingly used in many in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles in the United States. Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 43.8% of embryo transfers in the United States in 2019 included at least 1 PGT-A–tested embryo.6 Despite this widespread use, however, there are still no robust clinical data for PGT-A’s efficacy and safety, and the guidelines published by the ASRM do not recommend its routine use in all IVF cycles.7 In the past 2 to 3 years, several large studies have raised questions about the reported benefit of this technology.8,9

Details of the trial

In a multicenter, controlled, noninferiority trial conducted by Yan and colleagues, 1,212 subfertile women were randomly assigned to either conventional IVF with embryo selection based on morphology or embryo selection based on PGT-A with next-generation sequencing. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of subfertility, undergoing their first IVF cycle, female age of 20 to 37, and the availability of 3 or more good-quality blastocysts.

On day 5 of embryo culture, patients with 3 or more blastocysts were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the PGT-A group or conventional IVF. All embryos were then frozen, and patients subsequently underwent frozen embryo transfer of a single blastocyst, selected based on either morphology or euploid result by PGT-A. If the initial transfer did not result in a live birth, and there were remaining transferable embryos (either a euploid embryo in the PGT-A group or a morphologically transferable embryo in the conventional IVF group), patients underwent successive frozen embryo transfers until either there was a live birth or no more embryos were available for transfer.

The study’s primary outcome was the cumulative live birth rate per randomly assigned patient that resulted from up to 3 frozen embryo transfer cycles within 1 year. There were 606 patients randomly assigned to the PGT-A group and 606 randomly assigned to the conventional IVF group.

In the PGT-A group, 468 women (77.2%) had live births; in the conventional IVF group, 496 women (81.8%) had live births. Women in the PGT-A group had a lower incidence of pregnancy loss compared with the conventional IVF group: 8.7% versus 12.6% (absolute difference of -3.9%; 95% confidence interval [CI], -7.5 to -0.2). There was no difference in obstetric and neonatal outcomes between the 2 groups. The authors concluded that among women with 3 or more good-quality blastocysts, conventional IVF resulted in a cumulative live birth rate that was noninferior to that of the PGT-A group.

Some benefit shown with PGT-A

Although the study by Yan and colleagues did not show any benefit, and even a possible reduction, with regard to cumulative live birth rate for PGT-A, it did show a 4% reduction in clinical pregnancy loss when PGT-A was used. Furthermore, the study design has been criticized for performing PGT-A on only 3 blastocysts in the PGT-A group. It is quite conceivable that the PGT-A group would have had more euploid embryos available for transfer if the study design had included all the available embryos instead of only 3. On the other hand, one could argue that if the authors had extended the study to include all the available embryos, the conventional group would have also had more embryos for transfer and, therefore, more chances for pregnancy and live birth.

It is also important to recognize that only patients who had at least 3 embryos available for biopsy were included in this study, and therefore the results of this study cannot be extended to patients with fewer embryos, such as those with diminished ovarian reserve.

In summary, based on this study’s results, we may conclude that for the good-prognosis patients in the age group of 20 to 37 who have at least 3 embryos available for biopsy, PGT-A may reduce the miscarriage rate by about 4%, but this benefit comes at the expense of about a 4% reduction in the cumulative live birth rate. ●

Despite the lack of robust evidence for efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness, PGT-A has been widely adopted into clinical IVF practice in the United States over the past several years. A large randomized controlled trial has suggested that, compared with conventional IVF, PGT-A application may actually result in a slightly lower cumulative live birth rate, while the miscarriage rate may be slightly higher with conventional IVF.

PGT-A is a novel and evolving technology with the potential to improve embryo selection in IVF; however, at this juncture, there is not enough clinical data for its universal and routine use in all IVF cycles. PGT-A can potentially be more helpful in older women (>38–40) with good ovarian reserve who are likely to have a larger cohort of embryos to select from. Patients must clearly understand this technology’s pros and cons before agreeing to incorporate it into their care plan.

- Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;396:1285-1306.

- Dao TH, Docquier F, Maurel M, et al. Global migration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: the unstoppable force of demography. Rev World Econ. 2021;157:417-449.

- Atlas of fertility treatment policies in Europe. December 2021. Fertility Europe. Accessed December 29, 2022. https:// fertilityeurope.eu/atlas/#:~:text=Fertility%20Europe%20 in%20conjunction%20with%20the%20European%20 Parliamentary,The%20Atlas%20describes%20the%20 current%20situation%20in%202021

- AMWA’s physician fertility initiative. June 2021. American Medical Women’s Association. Accessed December 29, 2022. https://www.amwa-doc.org/our-work/initiatives/physician -infertility/

- Munro MG, Balen AH, Cho S, et al; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:768-786.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Assisted Reproductive Technology Fertility Clinic and National Summary Report. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/art /reports/2019/fertility-clinic.html

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. The use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:429-436.

- Yan J, Qin Y, Zhao H, et al. Live birth with or without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2047-2058.

- Kucherov A, Fazzari M, Lieman H, et al. PGT-A is associated with reduced cumulative live birth rate in first reported IVF stimulation cycles age ≤ 40: an analysis of 133,494 autologous cycles reported to SART CORS. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2023;40:137-149.

- Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;396:1285-1306.

- Dao TH, Docquier F, Maurel M, et al. Global migration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: the unstoppable force of demography. Rev World Econ. 2021;157:417-449.

- Atlas of fertility treatment policies in Europe. December 2021. Fertility Europe. Accessed December 29, 2022. https:// fertilityeurope.eu/atlas/#:~:text=Fertility%20Europe%20 in%20conjunction%20with%20the%20European%20 Parliamentary,The%20Atlas%20describes%20the%20 current%20situation%20in%202021

- AMWA’s physician fertility initiative. June 2021. American Medical Women’s Association. Accessed December 29, 2022. https://www.amwa-doc.org/our-work/initiatives/physician -infertility/

- Munro MG, Balen AH, Cho S, et al; FIGO Committee on Menstrual Disorders and Related Health Impacts, and FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, Endocrinology, and Infertility. The FIGO ovulatory disorders classification system. Fertil Steril. 2022;118:768-786.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Assisted Reproductive Technology Fertility Clinic and National Summary Report. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/art /reports/2019/fertility-clinic.html

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. The use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:429-436.

- Yan J, Qin Y, Zhao H, et al. Live birth with or without preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2047-2058.

- Kucherov A, Fazzari M, Lieman H, et al. PGT-A is associated with reduced cumulative live birth rate in first reported IVF stimulation cycles age ≤ 40: an analysis of 133,494 autologous cycles reported to SART CORS. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2023;40:137-149.

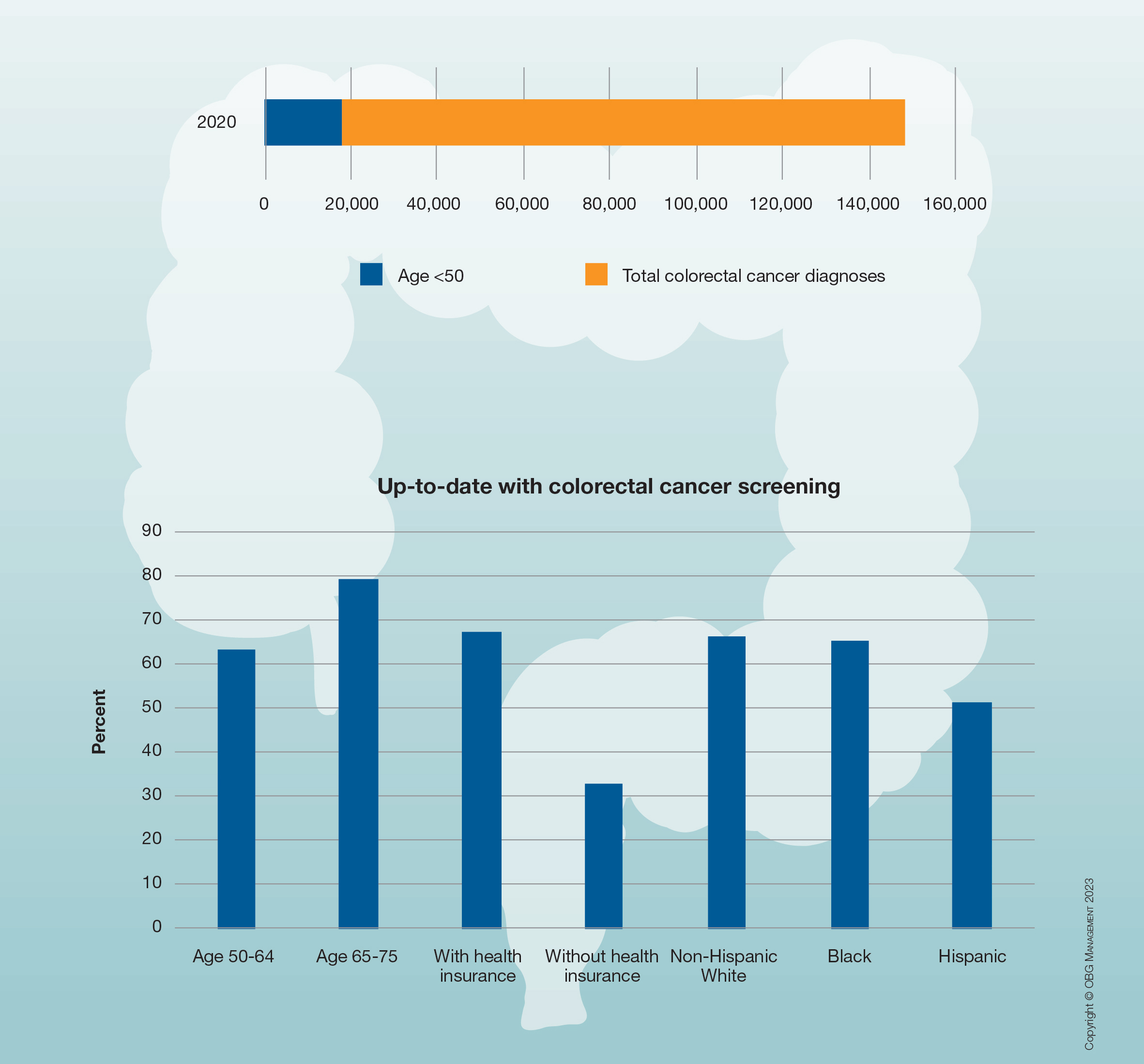

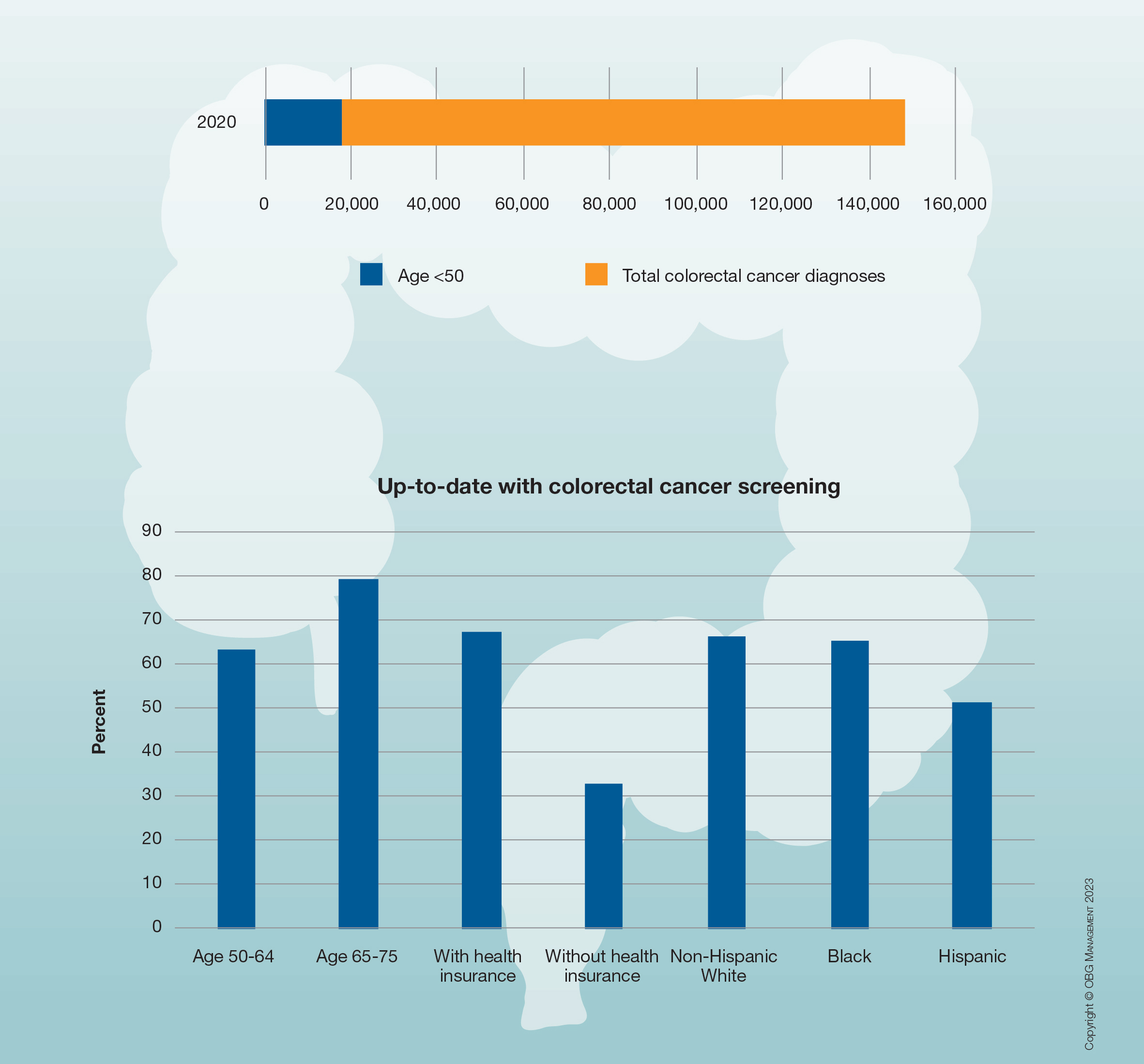

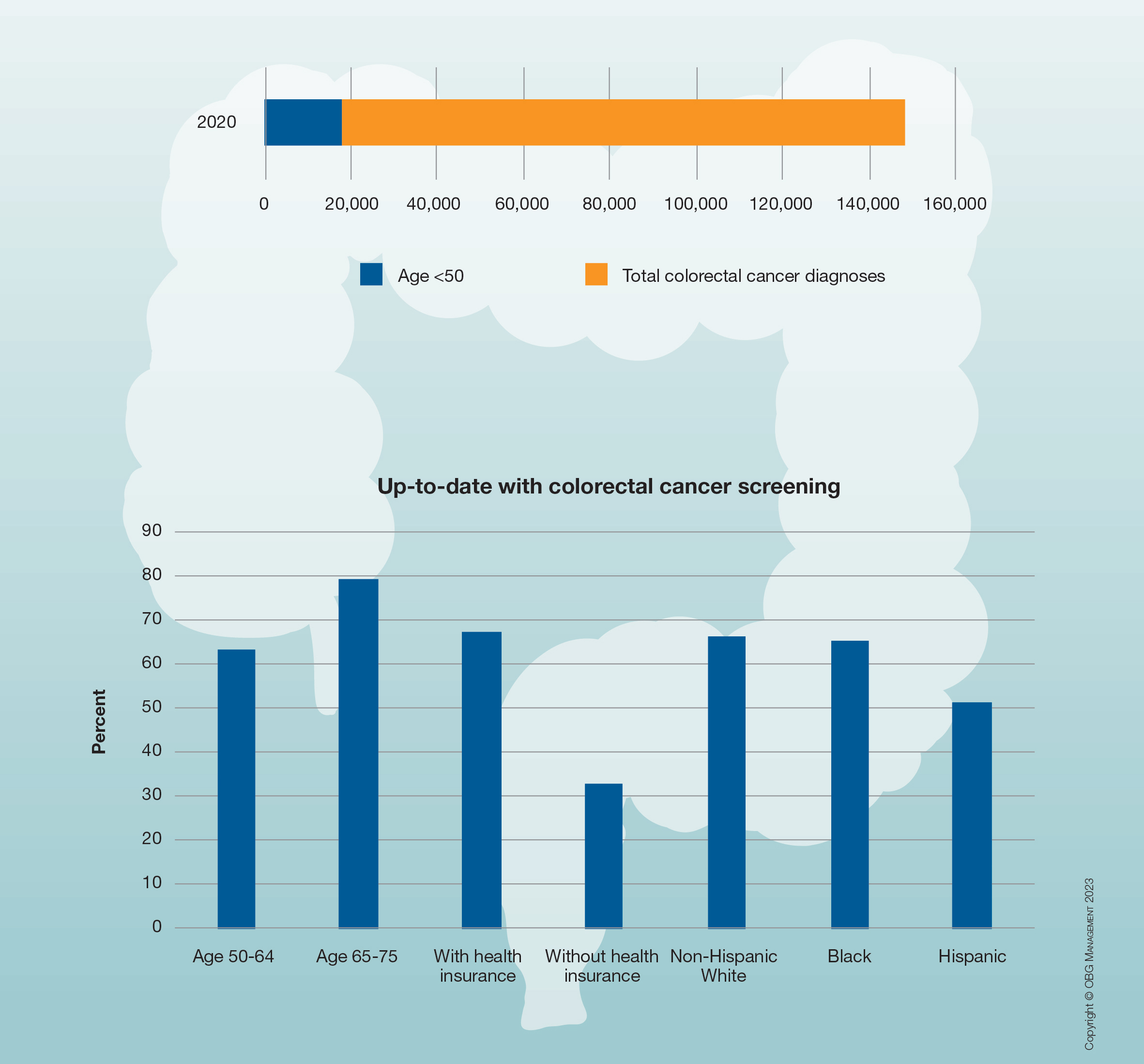

Trends in US colorectal cancer screening

Due to an increasing incidence of colon cancer among men and women aged 45 and younger, in 2018 the American Cancer Society, and in 2021 the US Preventive Services Task Force, recommended that screening for colon cancer begin at age 45 rather than age 50. More than half of the US population reports being up to date with these screening guidelines.

Due to an increasing incidence of colon cancer among men and women aged 45 and younger, in 2018 the American Cancer Society, and in 2021 the US Preventive Services Task Force, recommended that screening for colon cancer begin at age 45 rather than age 50. More than half of the US population reports being up to date with these screening guidelines.

Due to an increasing incidence of colon cancer among men and women aged 45 and younger, in 2018 the American Cancer Society, and in 2021 the US Preventive Services Task Force, recommended that screening for colon cancer begin at age 45 rather than age 50. More than half of the US population reports being up to date with these screening guidelines.

COMMENT & CONTROVERSY

Medical library access

During most of my clinical career I had an affiliation with a local medical school as a “Clinical Instructor” and then “Assistant Clinical Professor.” In addition to teaching medical students and residents from that institution that rotated through my hospital, it also gave me certain privileges, the most important of which was access to that institution’s electronic medical library. Using that access, even as an “LMD,” I have been able to contribute to the medical literature on subjects of interest to me and to others in my specialty.

Recently, now as an older clinician, I gave up my hospital privileges, although I continue my office practice. Giving up my hospital privileges meant that I no longer qualified as a faculty member—and therefore lost online access to the medical library. Still wishing to continue my medical writing, I have attempted to attain access to the medical literature by special request to that library, by contacting my state medical society, by contacting my national specialty organization, by contacting the department chair at the institution to which I had been affiliated, and by calling the Dean of the medical school to which my hospital was affiliated. Although meaning well, none was able to get me access to an online medical library. Thus, I am greatly hampered in my attempts to do research and to continue to write further papers on those areas in which I have previously published.

Is there no remedy for this? Should all clinicians who “age out” of institutional affiliations no longer be able to pursue research interests? And what about community physicians who have no academic affiliations? Can they not access the latest information they need to practice evidence-based, up-to-date medicine?

It makes no sense to me that access to the latest and most current aspects of medical care should be withheld from any clinician. For every clinician not to have access to such medical knowledge does a disservice to all those practicing medicine who wish to keep up to date and to all patients of American clinicians whose providers are prevented from practicing the best, evidence-based care.

Henry Lerner, MD

Boston, Massachusetts

Medical library access

During most of my clinical career I had an affiliation with a local medical school as a “Clinical Instructor” and then “Assistant Clinical Professor.” In addition to teaching medical students and residents from that institution that rotated through my hospital, it also gave me certain privileges, the most important of which was access to that institution’s electronic medical library. Using that access, even as an “LMD,” I have been able to contribute to the medical literature on subjects of interest to me and to others in my specialty.

Recently, now as an older clinician, I gave up my hospital privileges, although I continue my office practice. Giving up my hospital privileges meant that I no longer qualified as a faculty member—and therefore lost online access to the medical library. Still wishing to continue my medical writing, I have attempted to attain access to the medical literature by special request to that library, by contacting my state medical society, by contacting my national specialty organization, by contacting the department chair at the institution to which I had been affiliated, and by calling the Dean of the medical school to which my hospital was affiliated. Although meaning well, none was able to get me access to an online medical library. Thus, I am greatly hampered in my attempts to do research and to continue to write further papers on those areas in which I have previously published.

Is there no remedy for this? Should all clinicians who “age out” of institutional affiliations no longer be able to pursue research interests? And what about community physicians who have no academic affiliations? Can they not access the latest information they need to practice evidence-based, up-to-date medicine?