User login

HHS Nominee: Take Two

The so-far fitful process of choosing a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary may not delay meaningful healthcare reform—if President Obama remains committed to making the overhaul a top priority, says one of SHM's co-founders.

"On the one hand, he hasn't been able to get anything done in the first 100 days," says Hospitalist Win Whitcomb, MD, vice president of quality improvement at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. "That's not as concerning as if he did not prioritize the first year of his presidency. If he doesn't lay the groundwork for meaningful reform in healthcare, that's concerning."

Dr. Whitcomb's comments came as Obama picked Kansas Gov. Kathleen Sebelius as his new HHS secretary nominee. Obama's original choice, former Sen. Tom Daschle, withdrew from consideration amid questions about his taxes. Sebelius, a Democratic governor in a conservative state, could face a contentious Senate confirmation because of her anti-abortion critics. Obama, however, already has filled the other job Daschle was to hold with Nancy-Ann DeParle, a former health policy official during the Clinton administration. She will lead the White House Office on Health Reform; the appointment does not require Senate approval.

What this means for hospitalists is that Obama's goals to expand health insurance coverage, help install electronic record systems, and establish pay for performance in care delivery are receiving significant Oval Office attention. All were discussion topics last week as SHM officials met with congressional leaders on Capitol Hill.

"Any sort of reform that's going to be affecting hospitals, we'll be the key role players in making those changes," Dr. Whitcomb says. "We're in the hospital all the time and [among] the most invested."

For more on Obama's healthcare agenda visit http://www.whitehouse.gov/agenda/health_care.

The so-far fitful process of choosing a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary may not delay meaningful healthcare reform—if President Obama remains committed to making the overhaul a top priority, says one of SHM's co-founders.

"On the one hand, he hasn't been able to get anything done in the first 100 days," says Hospitalist Win Whitcomb, MD, vice president of quality improvement at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. "That's not as concerning as if he did not prioritize the first year of his presidency. If he doesn't lay the groundwork for meaningful reform in healthcare, that's concerning."

Dr. Whitcomb's comments came as Obama picked Kansas Gov. Kathleen Sebelius as his new HHS secretary nominee. Obama's original choice, former Sen. Tom Daschle, withdrew from consideration amid questions about his taxes. Sebelius, a Democratic governor in a conservative state, could face a contentious Senate confirmation because of her anti-abortion critics. Obama, however, already has filled the other job Daschle was to hold with Nancy-Ann DeParle, a former health policy official during the Clinton administration. She will lead the White House Office on Health Reform; the appointment does not require Senate approval.

What this means for hospitalists is that Obama's goals to expand health insurance coverage, help install electronic record systems, and establish pay for performance in care delivery are receiving significant Oval Office attention. All were discussion topics last week as SHM officials met with congressional leaders on Capitol Hill.

"Any sort of reform that's going to be affecting hospitals, we'll be the key role players in making those changes," Dr. Whitcomb says. "We're in the hospital all the time and [among] the most invested."

For more on Obama's healthcare agenda visit http://www.whitehouse.gov/agenda/health_care.

The so-far fitful process of choosing a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary may not delay meaningful healthcare reform—if President Obama remains committed to making the overhaul a top priority, says one of SHM's co-founders.

"On the one hand, he hasn't been able to get anything done in the first 100 days," says Hospitalist Win Whitcomb, MD, vice president of quality improvement at Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. "That's not as concerning as if he did not prioritize the first year of his presidency. If he doesn't lay the groundwork for meaningful reform in healthcare, that's concerning."

Dr. Whitcomb's comments came as Obama picked Kansas Gov. Kathleen Sebelius as his new HHS secretary nominee. Obama's original choice, former Sen. Tom Daschle, withdrew from consideration amid questions about his taxes. Sebelius, a Democratic governor in a conservative state, could face a contentious Senate confirmation because of her anti-abortion critics. Obama, however, already has filled the other job Daschle was to hold with Nancy-Ann DeParle, a former health policy official during the Clinton administration. She will lead the White House Office on Health Reform; the appointment does not require Senate approval.

What this means for hospitalists is that Obama's goals to expand health insurance coverage, help install electronic record systems, and establish pay for performance in care delivery are receiving significant Oval Office attention. All were discussion topics last week as SHM officials met with congressional leaders on Capitol Hill.

"Any sort of reform that's going to be affecting hospitals, we'll be the key role players in making those changes," Dr. Whitcomb says. "We're in the hospital all the time and [among] the most invested."

For more on Obama's healthcare agenda visit http://www.whitehouse.gov/agenda/health_care.

IV Contrast in Thyrotoxic Patients

Thyrotoxicosis is a relatively common endocrine disorder. An epidemiologic study estimated the prevalence of hyperthyroidism in the United States at 1.3%.1 In our experience newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis is 1 of the more frequent reasons for inpatient endocrinology specialty consultation. Generally, the diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis is made on clinical and laboratory grounds, and consultation is obtained in order to assist with diagnosing the specific cause and to arrange necessary treatment. A 24‐hour radioactive iodine uptake and scan are useful studies for differentiating the cause of thyrotoxicosis. These tests provide an indication of thyroid pathophysiology based on measurement and imaging of thyroidal uptake of a small dose of orally administered radioiodine. In thyrotoxic patients, the uptake is typically high in those with conditions associated with increased hormone synthesis, such as Graves' disease or autonomously functioning thyroid nodules, and is low in those with conditions associated with decreased hormone synthesis, such as thyroiditis or exogenous thyroid hormone ingestion.

Establishing the correct diagnosis has significant impact on the selection of appropriate therapy for these vastly different etiologies. Radioactive iodine in the form of I‐131 is useful in the treatment of certain thyrotoxic conditions. Radioiodine is the treatment most frequently employed in the United States for Graves' disease,2 and is also the most commonly used treatment of solitary toxic nodules and toxic multinodular goiter. However, it is of no use in treatment of subacute thyroiditis or exogenous ingestion of thyroid hormone. While antithyroid drugs such as methimazole or propylthiouracil can be used to treat conditions associated with increased thyroid hormone synthesis, they also are not effective in treating subacute thyroiditis or thyrotoxicosis factitia; therefore, it is important to establish the diagnosis before using these medications.

Exogenous iodine that has been administered prior to administration of radioiodine can interfere with the uptake of radioiodine by the thyroid, thus rendering the 24‐hour uptake and scan inaccurate as a means of diagnosis, and interfering with the utility of I‐131 as a treatment.3 In our experience, many inpatients with newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis receive exogenous iodine in the form of intravenous (IV) contrast agents near the time of their presentation, leading to an inability to utilize radioactive iodine to diagnose and potentially treat them. One common reason for the use of iodinated contrast is to enhance computed tomography (CT) scan images. Many symptoms that could presumably lead to the ordering of a CT scan may overlap with symptoms of thyrotoxicosis. Prompt diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis, along with awareness of the interference of IV contrast with use of radioactive iodine and the frequency with which this occurs, may prevent unnecessary CT scans in some patients. Therefore, we undertook this study to quantify the frequency of this occurrence, and the frequency that the IV contrast studies were ultimately useful in the management of these patients.

Methods

The records of inpatient endocrinology consultations over a 48‐month period (January 2003 through January 2007) were reviewed. Consultations requested for thyroid disease were identified, and those which were for thyrotoxicosis were reviewed. Patients with thyrotoxicosis with a cause that had been previously determined, or who had already undergone treatment, were not included in the analysis. The remaining patients with new onset thyrotoxicosis, based on clinical and laboratory findings, in whom radioactive iodine would have been useful for diagnostic and potentially treatment purposes, were included.

Of the patients included, our records were reviewed to determine demographic data, whether intravenous contrast had been administered within 2 weeks of endocrinology consultation, and the type of study that was performed. The results of the contrast studies were reviewed, with attention to findings that potentially could have changed acute or inpatient management of the patients.

Results

A total of 1171 consults were reviewed. Of these, 324 (27.7%) were for thyroid disease. One hundred patients (8.5% of total consults, 30.8% of thyroid disease consults) were identified with previously unevaluated thyrotoxicosis as the primary reason for the consult. Of these patients, 74% were women, and 26% were men. The mean age was 54.6 years (range 18‐93 years).

Forty‐five patients (45%) had been given iodinated contrast within 2 weeks prior to endocrinology evaluation, 43 for CT scanning, and 2 for angiography. There were a total of 50 contrast‐enhanced CT scans done (7 patients had CT scans of multiple anatomic regions). There were 26 chest CT scans, 16 abdominal/pelvic CT scans, and 8 neck CT scans. Indications for the CT scans in these patients are shown in Table 1.

| Indication for CT Scan | Number of Patients |

|---|---|

| Palpitations/shortness of breath | 20 |

| Abdominal pain | 6 |

| Neck swelling | 6 |

| Weight loss | 2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 |

| Loose stool | 1 |

| Question of abdominal mass | 1 |

| Jaundice | 1 |

| Palpable lymphadenopathy | 1 |

| Trauma | 1 |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 |

Of the 43 patients who underwent CT scanning, 7 (16%) had a finding that potentially changed their inpatient management (2 with tracheal compression by a goiter, 1 with airway compromise from tonsillar edema, 1 with appendicitis, 1 with pulmonary hypertension, 1 with diffuse lymphoma, and 1 with a rib fracture after trauma). Only 1 of these patients (appendicitis) required emergent treatment of their condition before further diagnostic studies could have been reasonably performed. Among the angiography patients, 1 had undergone cardiac catheterization, which was diagnostic of coronary artery disease, and 1 had undergone angiography of the lower extremities, which revealed an acute arterial clot.

Also of note, in April 2005 at our institution, a new emergency department opened which made it logistically easier to obtain a CT scan. Prior to that time, 16 of 49 patients (33%) evaluated for thyrotoxicosis had received iodinated contrast for a CT scan. After that time, 27 of 51 patients (52%) received a contrast CT study.

Discussion

Indications for contrast‐enhanced CT scans in the acute care setting are numerous. The majority of the CT scans ordered in the above patients were of the chest. CT scans of the chest may be used to evaluate suspected pulmonary emboli or aortic dissection. Coronary CT angiography is also being studied as a method of risk stratification of patients presenting with acute chest pain.4 Common signs and symptoms of the above disorders include chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, and tachycardia. Many of the most common cardiovascular signs and symptoms associated with thyrotoxicosis overlap with those seen in the above disorders. A recent study of thyrotoxic patients found that on presentation, 73% had palpitations, 60% had dyspnea, 25% had chest pain, and 35% had cough.5 Mean heart rate has been shown to be significantly elevated in thyrotoxic patients compared with normal controls.5, 6 Atrial fibrillation or flutter can occur in about 8% of thyrotoxic patients, especially in males, in older ages, and in those with underlying cardiac disease.7

We also noted that 16 out of the 50 total contrast‐enhanced CT scans performed were of the abdomen and pelvis. While abdominal and gastrointestinal signs and symptoms seem to be less common manifestations of thyrotoxicosis than cardiovascular ones, hyperdefecation with or without diarrhea can be seen in approximately in one‐third of cases. Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and jaundice occur less commonly but can be seen occasionally with severe thyrotoxicosis.3 Weight loss is common, and fever may occur occasionally, which also may trigger evaluation by imaging for malignancy or infection.

Indications for the CT scans ordered for the patients in this study can be seen in Table 1. Some of the studies were ordered for symptoms not likely to be thyroid‐related and may have been unavoidable. However, many of the studies, especially those done for complaints such as palpitations, dyspnea, and weight loss were likely obtained due to symptoms that ultimately turned out to be caused by thyrotoxicosis.

A variety of other factors may uncommonly decrease radioactive iodine uptake, including cardiac decompensation, vomiting after ingestion of the orally dosed radioiodine capsule, and medications, including thioureas. However, exogenous iodine is probably the most common interfering factor.8 Exogenous iodine decreases thyroidal radioiodine uptake both by dilution of the total body iodine pool, and by inhibition of thyroid hormone synthesis via the Wolff‐Chaikoff effect.8 Sources of iodine include diet, medications (amiodarone, which contains approximately 6 mg of inorganic iodine per 200 mg tablet, and potassium iodide), and, most prominently in the hospitalized patient, intravenous contrast material. It has been shown that exposure to as little as 100 g of intravenous iodide can suppress uptake in hyperthyroid patients.9 Both ionic and nonionic intravenous contrast media contain sufficient amounts of inorganic iodide (10 g/ml) to induce this suppression when given in typical doses of 50‐200 ml. This iodide may be derived from deiodination of the contrast media molecule, and also from free iodide contaminants.10 The duration of uptake suppression varies among patients and generally ranges from 4 to 12 weeks, although it may be shorter in hyperthyroid patients.8 This long‐term suppression may be related to the slow deiodination of contrast media remaining in the body.10 Urinary iodine normalization can be used as a means of determining the time when uptake can be measured without interference from exogenous iodine.

Iodine administration can also have deleterious effects on thyroid function apart from its effect on radioiodine uptake. In euthyroid patients, exogenous iodine in large doses inhibits organification of iodide and thyroid hormone synthesis (Wolff‐Chaikoff effect). Normally this effect diminishes after several weeks, but in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, it may persist, leading to hypothyroidism.11 Iodine ingestion may also lead to hyperthyroidism. In areas of endemic iodine deficiency, this is thought to represent unmasking of thyroid autonomy that had been suppressed by lack of iodine, encompassing such patients as those with Graves' disease or autonomous nodules. In areas of iodine sufficiency such as the United States, the incidence of iodine‐induced thyrotoxicosis is low, and typically occurs in patients with autonomous thyroid nodules or multinodular goiter.11, 12 Cases of thyroid storm have been reported following iodinated contrast administration.13 The elderly may be at greater risk for iodine‐induced thyrotoxicosis,14 which is of concern given their inherent higher likelihood of cardiac disease. It is possible that in some of the patients in our study who had CT scans done for nonthyroid‐related symptoms, iodinated contrast could have precipitated subsequent thyrotoxicosis. In general, caution should be used when administering intravenous contrast agents to patients with known thyroid disease.

CT scanning is being used much more frequently in the acute care setting. One study in the emergency department at a single institution revealed that from the years 2000 to 2005, CT scanning of the chest increased by 226%, and of the abdomen by 72%, despite only a 13% increase in patient volume and a stable level of acuity.15 We refer the reader to this recent review for a discussion of the recent increase in the use of CT scans and the associated risks.16 We have found that a substantial proportion of inpatients with thyrotoxicosis receive intravenous contrast prior to endocrinologic evaluation, thus limiting the ability to use radioactive iodine in diagnosis and treatment. The vast majority of these diagnostic studies are contrast‐enhanced CT scans. Acute findings from these studies in this population that change patient management are uncommon.

The increasing usage of CT scans may exacerbate this problem. Education of physicians that are likely to diagnose thyrotoxicosis prior to subspecialty evaluation (internists, family practitioners, and emergency medicine physicians) regarding the similarity of thyrotoxic symptoms to those typically triggering the request of a CT scan is essential. Clinicians should have an appreciation of the interference of iodinated contrast with the ability to obtain a radioiodine uptake and scan. They should also be aware of the potential effects of iodinated contrast on thyroid function when ordering a contrast‐enhanced CT scan in patients with known thyroid disease or symptoms consistent with the presence of thyrotoxicosis. Under these circumstances consideration of thyroid dysfunction with appropriate blood tests may result in more accurate and timely diagnosis and treatment of underlying thyroid disease and enhance patient outcomes.

- ,,, et al.Serum TSH, T4, and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).J Clin Endo Metab.2002;87:489–499.

- ,,,.Differences and similarities in the diagnosis and treatment of Graves' disease in Europe, Japan, and the United States.Thyroid.1991;1:129–135.

- ,.Thyrotoxicosis. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, eds.Williams Textbook of Endocrinology.10th ed.Philadelphia:Saunders;2003:374–421.

- .Chest pain in the emergency department.JThorac Imaging.2007;22:49–55.

- ,,, et al.Cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism before and after antithyroid therapy.J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;49:71–81.

- ,.Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system.N Engl J Med.2001;344:501–509.

- ,,.Hyperthyroidism and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter.Arch Intern Med.2004;164:1675–1678.

- .Factors which influence the radioactive iodine thyroidal uptake test.Am J Med.1960;28:397–415.

- ,,, et al.The effect of varying quantities of inorganic iodide (carrier) on the urinary excretion and thyroidal accumulation of radioiodine in exophthalmic goiter.J Clin Invest.1950;29:726–738.

- ,,.Contrast material iodides: potential effects on radioactive iodine thyroid uptake.J Nucl Med.1992;33:237–238.

- ,.Iodine excess and hyperthyroidism.Thyroid.2001;11:493–500.

- ,,.Effect of iodinated contrast media on thyroid function in adults.Eur Radiol.2004;14:902–907.

- ,,,.Thyroidectomy in iodine induced thyrotoxic storm.Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes.1999;107:468–472.

- ,.Hyperthyroidism in elderly hospitalized patients.Med J Aust.1996;164:200–203.

- ,.Increasing utilization of computed tomography in the adult emergency department, 2000–2005.Emerg Radiol.2006;13:25–30.

- ,.Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure.N Engl J Med.2007;357:2277–2284.

Thyrotoxicosis is a relatively common endocrine disorder. An epidemiologic study estimated the prevalence of hyperthyroidism in the United States at 1.3%.1 In our experience newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis is 1 of the more frequent reasons for inpatient endocrinology specialty consultation. Generally, the diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis is made on clinical and laboratory grounds, and consultation is obtained in order to assist with diagnosing the specific cause and to arrange necessary treatment. A 24‐hour radioactive iodine uptake and scan are useful studies for differentiating the cause of thyrotoxicosis. These tests provide an indication of thyroid pathophysiology based on measurement and imaging of thyroidal uptake of a small dose of orally administered radioiodine. In thyrotoxic patients, the uptake is typically high in those with conditions associated with increased hormone synthesis, such as Graves' disease or autonomously functioning thyroid nodules, and is low in those with conditions associated with decreased hormone synthesis, such as thyroiditis or exogenous thyroid hormone ingestion.

Establishing the correct diagnosis has significant impact on the selection of appropriate therapy for these vastly different etiologies. Radioactive iodine in the form of I‐131 is useful in the treatment of certain thyrotoxic conditions. Radioiodine is the treatment most frequently employed in the United States for Graves' disease,2 and is also the most commonly used treatment of solitary toxic nodules and toxic multinodular goiter. However, it is of no use in treatment of subacute thyroiditis or exogenous ingestion of thyroid hormone. While antithyroid drugs such as methimazole or propylthiouracil can be used to treat conditions associated with increased thyroid hormone synthesis, they also are not effective in treating subacute thyroiditis or thyrotoxicosis factitia; therefore, it is important to establish the diagnosis before using these medications.

Exogenous iodine that has been administered prior to administration of radioiodine can interfere with the uptake of radioiodine by the thyroid, thus rendering the 24‐hour uptake and scan inaccurate as a means of diagnosis, and interfering with the utility of I‐131 as a treatment.3 In our experience, many inpatients with newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis receive exogenous iodine in the form of intravenous (IV) contrast agents near the time of their presentation, leading to an inability to utilize radioactive iodine to diagnose and potentially treat them. One common reason for the use of iodinated contrast is to enhance computed tomography (CT) scan images. Many symptoms that could presumably lead to the ordering of a CT scan may overlap with symptoms of thyrotoxicosis. Prompt diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis, along with awareness of the interference of IV contrast with use of radioactive iodine and the frequency with which this occurs, may prevent unnecessary CT scans in some patients. Therefore, we undertook this study to quantify the frequency of this occurrence, and the frequency that the IV contrast studies were ultimately useful in the management of these patients.

Methods

The records of inpatient endocrinology consultations over a 48‐month period (January 2003 through January 2007) were reviewed. Consultations requested for thyroid disease were identified, and those which were for thyrotoxicosis were reviewed. Patients with thyrotoxicosis with a cause that had been previously determined, or who had already undergone treatment, were not included in the analysis. The remaining patients with new onset thyrotoxicosis, based on clinical and laboratory findings, in whom radioactive iodine would have been useful for diagnostic and potentially treatment purposes, were included.

Of the patients included, our records were reviewed to determine demographic data, whether intravenous contrast had been administered within 2 weeks of endocrinology consultation, and the type of study that was performed. The results of the contrast studies were reviewed, with attention to findings that potentially could have changed acute or inpatient management of the patients.

Results

A total of 1171 consults were reviewed. Of these, 324 (27.7%) were for thyroid disease. One hundred patients (8.5% of total consults, 30.8% of thyroid disease consults) were identified with previously unevaluated thyrotoxicosis as the primary reason for the consult. Of these patients, 74% were women, and 26% were men. The mean age was 54.6 years (range 18‐93 years).

Forty‐five patients (45%) had been given iodinated contrast within 2 weeks prior to endocrinology evaluation, 43 for CT scanning, and 2 for angiography. There were a total of 50 contrast‐enhanced CT scans done (7 patients had CT scans of multiple anatomic regions). There were 26 chest CT scans, 16 abdominal/pelvic CT scans, and 8 neck CT scans. Indications for the CT scans in these patients are shown in Table 1.

| Indication for CT Scan | Number of Patients |

|---|---|

| Palpitations/shortness of breath | 20 |

| Abdominal pain | 6 |

| Neck swelling | 6 |

| Weight loss | 2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 |

| Loose stool | 1 |

| Question of abdominal mass | 1 |

| Jaundice | 1 |

| Palpable lymphadenopathy | 1 |

| Trauma | 1 |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 |

Of the 43 patients who underwent CT scanning, 7 (16%) had a finding that potentially changed their inpatient management (2 with tracheal compression by a goiter, 1 with airway compromise from tonsillar edema, 1 with appendicitis, 1 with pulmonary hypertension, 1 with diffuse lymphoma, and 1 with a rib fracture after trauma). Only 1 of these patients (appendicitis) required emergent treatment of their condition before further diagnostic studies could have been reasonably performed. Among the angiography patients, 1 had undergone cardiac catheterization, which was diagnostic of coronary artery disease, and 1 had undergone angiography of the lower extremities, which revealed an acute arterial clot.

Also of note, in April 2005 at our institution, a new emergency department opened which made it logistically easier to obtain a CT scan. Prior to that time, 16 of 49 patients (33%) evaluated for thyrotoxicosis had received iodinated contrast for a CT scan. After that time, 27 of 51 patients (52%) received a contrast CT study.

Discussion

Indications for contrast‐enhanced CT scans in the acute care setting are numerous. The majority of the CT scans ordered in the above patients were of the chest. CT scans of the chest may be used to evaluate suspected pulmonary emboli or aortic dissection. Coronary CT angiography is also being studied as a method of risk stratification of patients presenting with acute chest pain.4 Common signs and symptoms of the above disorders include chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, and tachycardia. Many of the most common cardiovascular signs and symptoms associated with thyrotoxicosis overlap with those seen in the above disorders. A recent study of thyrotoxic patients found that on presentation, 73% had palpitations, 60% had dyspnea, 25% had chest pain, and 35% had cough.5 Mean heart rate has been shown to be significantly elevated in thyrotoxic patients compared with normal controls.5, 6 Atrial fibrillation or flutter can occur in about 8% of thyrotoxic patients, especially in males, in older ages, and in those with underlying cardiac disease.7

We also noted that 16 out of the 50 total contrast‐enhanced CT scans performed were of the abdomen and pelvis. While abdominal and gastrointestinal signs and symptoms seem to be less common manifestations of thyrotoxicosis than cardiovascular ones, hyperdefecation with or without diarrhea can be seen in approximately in one‐third of cases. Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and jaundice occur less commonly but can be seen occasionally with severe thyrotoxicosis.3 Weight loss is common, and fever may occur occasionally, which also may trigger evaluation by imaging for malignancy or infection.

Indications for the CT scans ordered for the patients in this study can be seen in Table 1. Some of the studies were ordered for symptoms not likely to be thyroid‐related and may have been unavoidable. However, many of the studies, especially those done for complaints such as palpitations, dyspnea, and weight loss were likely obtained due to symptoms that ultimately turned out to be caused by thyrotoxicosis.

A variety of other factors may uncommonly decrease radioactive iodine uptake, including cardiac decompensation, vomiting after ingestion of the orally dosed radioiodine capsule, and medications, including thioureas. However, exogenous iodine is probably the most common interfering factor.8 Exogenous iodine decreases thyroidal radioiodine uptake both by dilution of the total body iodine pool, and by inhibition of thyroid hormone synthesis via the Wolff‐Chaikoff effect.8 Sources of iodine include diet, medications (amiodarone, which contains approximately 6 mg of inorganic iodine per 200 mg tablet, and potassium iodide), and, most prominently in the hospitalized patient, intravenous contrast material. It has been shown that exposure to as little as 100 g of intravenous iodide can suppress uptake in hyperthyroid patients.9 Both ionic and nonionic intravenous contrast media contain sufficient amounts of inorganic iodide (10 g/ml) to induce this suppression when given in typical doses of 50‐200 ml. This iodide may be derived from deiodination of the contrast media molecule, and also from free iodide contaminants.10 The duration of uptake suppression varies among patients and generally ranges from 4 to 12 weeks, although it may be shorter in hyperthyroid patients.8 This long‐term suppression may be related to the slow deiodination of contrast media remaining in the body.10 Urinary iodine normalization can be used as a means of determining the time when uptake can be measured without interference from exogenous iodine.

Iodine administration can also have deleterious effects on thyroid function apart from its effect on radioiodine uptake. In euthyroid patients, exogenous iodine in large doses inhibits organification of iodide and thyroid hormone synthesis (Wolff‐Chaikoff effect). Normally this effect diminishes after several weeks, but in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, it may persist, leading to hypothyroidism.11 Iodine ingestion may also lead to hyperthyroidism. In areas of endemic iodine deficiency, this is thought to represent unmasking of thyroid autonomy that had been suppressed by lack of iodine, encompassing such patients as those with Graves' disease or autonomous nodules. In areas of iodine sufficiency such as the United States, the incidence of iodine‐induced thyrotoxicosis is low, and typically occurs in patients with autonomous thyroid nodules or multinodular goiter.11, 12 Cases of thyroid storm have been reported following iodinated contrast administration.13 The elderly may be at greater risk for iodine‐induced thyrotoxicosis,14 which is of concern given their inherent higher likelihood of cardiac disease. It is possible that in some of the patients in our study who had CT scans done for nonthyroid‐related symptoms, iodinated contrast could have precipitated subsequent thyrotoxicosis. In general, caution should be used when administering intravenous contrast agents to patients with known thyroid disease.

CT scanning is being used much more frequently in the acute care setting. One study in the emergency department at a single institution revealed that from the years 2000 to 2005, CT scanning of the chest increased by 226%, and of the abdomen by 72%, despite only a 13% increase in patient volume and a stable level of acuity.15 We refer the reader to this recent review for a discussion of the recent increase in the use of CT scans and the associated risks.16 We have found that a substantial proportion of inpatients with thyrotoxicosis receive intravenous contrast prior to endocrinologic evaluation, thus limiting the ability to use radioactive iodine in diagnosis and treatment. The vast majority of these diagnostic studies are contrast‐enhanced CT scans. Acute findings from these studies in this population that change patient management are uncommon.

The increasing usage of CT scans may exacerbate this problem. Education of physicians that are likely to diagnose thyrotoxicosis prior to subspecialty evaluation (internists, family practitioners, and emergency medicine physicians) regarding the similarity of thyrotoxic symptoms to those typically triggering the request of a CT scan is essential. Clinicians should have an appreciation of the interference of iodinated contrast with the ability to obtain a radioiodine uptake and scan. They should also be aware of the potential effects of iodinated contrast on thyroid function when ordering a contrast‐enhanced CT scan in patients with known thyroid disease or symptoms consistent with the presence of thyrotoxicosis. Under these circumstances consideration of thyroid dysfunction with appropriate blood tests may result in more accurate and timely diagnosis and treatment of underlying thyroid disease and enhance patient outcomes.

Thyrotoxicosis is a relatively common endocrine disorder. An epidemiologic study estimated the prevalence of hyperthyroidism in the United States at 1.3%.1 In our experience newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis is 1 of the more frequent reasons for inpatient endocrinology specialty consultation. Generally, the diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis is made on clinical and laboratory grounds, and consultation is obtained in order to assist with diagnosing the specific cause and to arrange necessary treatment. A 24‐hour radioactive iodine uptake and scan are useful studies for differentiating the cause of thyrotoxicosis. These tests provide an indication of thyroid pathophysiology based on measurement and imaging of thyroidal uptake of a small dose of orally administered radioiodine. In thyrotoxic patients, the uptake is typically high in those with conditions associated with increased hormone synthesis, such as Graves' disease or autonomously functioning thyroid nodules, and is low in those with conditions associated with decreased hormone synthesis, such as thyroiditis or exogenous thyroid hormone ingestion.

Establishing the correct diagnosis has significant impact on the selection of appropriate therapy for these vastly different etiologies. Radioactive iodine in the form of I‐131 is useful in the treatment of certain thyrotoxic conditions. Radioiodine is the treatment most frequently employed in the United States for Graves' disease,2 and is also the most commonly used treatment of solitary toxic nodules and toxic multinodular goiter. However, it is of no use in treatment of subacute thyroiditis or exogenous ingestion of thyroid hormone. While antithyroid drugs such as methimazole or propylthiouracil can be used to treat conditions associated with increased thyroid hormone synthesis, they also are not effective in treating subacute thyroiditis or thyrotoxicosis factitia; therefore, it is important to establish the diagnosis before using these medications.

Exogenous iodine that has been administered prior to administration of radioiodine can interfere with the uptake of radioiodine by the thyroid, thus rendering the 24‐hour uptake and scan inaccurate as a means of diagnosis, and interfering with the utility of I‐131 as a treatment.3 In our experience, many inpatients with newly diagnosed thyrotoxicosis receive exogenous iodine in the form of intravenous (IV) contrast agents near the time of their presentation, leading to an inability to utilize radioactive iodine to diagnose and potentially treat them. One common reason for the use of iodinated contrast is to enhance computed tomography (CT) scan images. Many symptoms that could presumably lead to the ordering of a CT scan may overlap with symptoms of thyrotoxicosis. Prompt diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis, along with awareness of the interference of IV contrast with use of radioactive iodine and the frequency with which this occurs, may prevent unnecessary CT scans in some patients. Therefore, we undertook this study to quantify the frequency of this occurrence, and the frequency that the IV contrast studies were ultimately useful in the management of these patients.

Methods

The records of inpatient endocrinology consultations over a 48‐month period (January 2003 through January 2007) were reviewed. Consultations requested for thyroid disease were identified, and those which were for thyrotoxicosis were reviewed. Patients with thyrotoxicosis with a cause that had been previously determined, or who had already undergone treatment, were not included in the analysis. The remaining patients with new onset thyrotoxicosis, based on clinical and laboratory findings, in whom radioactive iodine would have been useful for diagnostic and potentially treatment purposes, were included.

Of the patients included, our records were reviewed to determine demographic data, whether intravenous contrast had been administered within 2 weeks of endocrinology consultation, and the type of study that was performed. The results of the contrast studies were reviewed, with attention to findings that potentially could have changed acute or inpatient management of the patients.

Results

A total of 1171 consults were reviewed. Of these, 324 (27.7%) were for thyroid disease. One hundred patients (8.5% of total consults, 30.8% of thyroid disease consults) were identified with previously unevaluated thyrotoxicosis as the primary reason for the consult. Of these patients, 74% were women, and 26% were men. The mean age was 54.6 years (range 18‐93 years).

Forty‐five patients (45%) had been given iodinated contrast within 2 weeks prior to endocrinology evaluation, 43 for CT scanning, and 2 for angiography. There were a total of 50 contrast‐enhanced CT scans done (7 patients had CT scans of multiple anatomic regions). There were 26 chest CT scans, 16 abdominal/pelvic CT scans, and 8 neck CT scans. Indications for the CT scans in these patients are shown in Table 1.

| Indication for CT Scan | Number of Patients |

|---|---|

| Palpitations/shortness of breath | 20 |

| Abdominal pain | 6 |

| Neck swelling | 6 |

| Weight loss | 2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 |

| Loose stool | 1 |

| Question of abdominal mass | 1 |

| Jaundice | 1 |

| Palpable lymphadenopathy | 1 |

| Trauma | 1 |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 |

Of the 43 patients who underwent CT scanning, 7 (16%) had a finding that potentially changed their inpatient management (2 with tracheal compression by a goiter, 1 with airway compromise from tonsillar edema, 1 with appendicitis, 1 with pulmonary hypertension, 1 with diffuse lymphoma, and 1 with a rib fracture after trauma). Only 1 of these patients (appendicitis) required emergent treatment of their condition before further diagnostic studies could have been reasonably performed. Among the angiography patients, 1 had undergone cardiac catheterization, which was diagnostic of coronary artery disease, and 1 had undergone angiography of the lower extremities, which revealed an acute arterial clot.

Also of note, in April 2005 at our institution, a new emergency department opened which made it logistically easier to obtain a CT scan. Prior to that time, 16 of 49 patients (33%) evaluated for thyrotoxicosis had received iodinated contrast for a CT scan. After that time, 27 of 51 patients (52%) received a contrast CT study.

Discussion

Indications for contrast‐enhanced CT scans in the acute care setting are numerous. The majority of the CT scans ordered in the above patients were of the chest. CT scans of the chest may be used to evaluate suspected pulmonary emboli or aortic dissection. Coronary CT angiography is also being studied as a method of risk stratification of patients presenting with acute chest pain.4 Common signs and symptoms of the above disorders include chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, and tachycardia. Many of the most common cardiovascular signs and symptoms associated with thyrotoxicosis overlap with those seen in the above disorders. A recent study of thyrotoxic patients found that on presentation, 73% had palpitations, 60% had dyspnea, 25% had chest pain, and 35% had cough.5 Mean heart rate has been shown to be significantly elevated in thyrotoxic patients compared with normal controls.5, 6 Atrial fibrillation or flutter can occur in about 8% of thyrotoxic patients, especially in males, in older ages, and in those with underlying cardiac disease.7

We also noted that 16 out of the 50 total contrast‐enhanced CT scans performed were of the abdomen and pelvis. While abdominal and gastrointestinal signs and symptoms seem to be less common manifestations of thyrotoxicosis than cardiovascular ones, hyperdefecation with or without diarrhea can be seen in approximately in one‐third of cases. Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and jaundice occur less commonly but can be seen occasionally with severe thyrotoxicosis.3 Weight loss is common, and fever may occur occasionally, which also may trigger evaluation by imaging for malignancy or infection.

Indications for the CT scans ordered for the patients in this study can be seen in Table 1. Some of the studies were ordered for symptoms not likely to be thyroid‐related and may have been unavoidable. However, many of the studies, especially those done for complaints such as palpitations, dyspnea, and weight loss were likely obtained due to symptoms that ultimately turned out to be caused by thyrotoxicosis.

A variety of other factors may uncommonly decrease radioactive iodine uptake, including cardiac decompensation, vomiting after ingestion of the orally dosed radioiodine capsule, and medications, including thioureas. However, exogenous iodine is probably the most common interfering factor.8 Exogenous iodine decreases thyroidal radioiodine uptake both by dilution of the total body iodine pool, and by inhibition of thyroid hormone synthesis via the Wolff‐Chaikoff effect.8 Sources of iodine include diet, medications (amiodarone, which contains approximately 6 mg of inorganic iodine per 200 mg tablet, and potassium iodide), and, most prominently in the hospitalized patient, intravenous contrast material. It has been shown that exposure to as little as 100 g of intravenous iodide can suppress uptake in hyperthyroid patients.9 Both ionic and nonionic intravenous contrast media contain sufficient amounts of inorganic iodide (10 g/ml) to induce this suppression when given in typical doses of 50‐200 ml. This iodide may be derived from deiodination of the contrast media molecule, and also from free iodide contaminants.10 The duration of uptake suppression varies among patients and generally ranges from 4 to 12 weeks, although it may be shorter in hyperthyroid patients.8 This long‐term suppression may be related to the slow deiodination of contrast media remaining in the body.10 Urinary iodine normalization can be used as a means of determining the time when uptake can be measured without interference from exogenous iodine.

Iodine administration can also have deleterious effects on thyroid function apart from its effect on radioiodine uptake. In euthyroid patients, exogenous iodine in large doses inhibits organification of iodide and thyroid hormone synthesis (Wolff‐Chaikoff effect). Normally this effect diminishes after several weeks, but in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, it may persist, leading to hypothyroidism.11 Iodine ingestion may also lead to hyperthyroidism. In areas of endemic iodine deficiency, this is thought to represent unmasking of thyroid autonomy that had been suppressed by lack of iodine, encompassing such patients as those with Graves' disease or autonomous nodules. In areas of iodine sufficiency such as the United States, the incidence of iodine‐induced thyrotoxicosis is low, and typically occurs in patients with autonomous thyroid nodules or multinodular goiter.11, 12 Cases of thyroid storm have been reported following iodinated contrast administration.13 The elderly may be at greater risk for iodine‐induced thyrotoxicosis,14 which is of concern given their inherent higher likelihood of cardiac disease. It is possible that in some of the patients in our study who had CT scans done for nonthyroid‐related symptoms, iodinated contrast could have precipitated subsequent thyrotoxicosis. In general, caution should be used when administering intravenous contrast agents to patients with known thyroid disease.

CT scanning is being used much more frequently in the acute care setting. One study in the emergency department at a single institution revealed that from the years 2000 to 2005, CT scanning of the chest increased by 226%, and of the abdomen by 72%, despite only a 13% increase in patient volume and a stable level of acuity.15 We refer the reader to this recent review for a discussion of the recent increase in the use of CT scans and the associated risks.16 We have found that a substantial proportion of inpatients with thyrotoxicosis receive intravenous contrast prior to endocrinologic evaluation, thus limiting the ability to use radioactive iodine in diagnosis and treatment. The vast majority of these diagnostic studies are contrast‐enhanced CT scans. Acute findings from these studies in this population that change patient management are uncommon.

The increasing usage of CT scans may exacerbate this problem. Education of physicians that are likely to diagnose thyrotoxicosis prior to subspecialty evaluation (internists, family practitioners, and emergency medicine physicians) regarding the similarity of thyrotoxic symptoms to those typically triggering the request of a CT scan is essential. Clinicians should have an appreciation of the interference of iodinated contrast with the ability to obtain a radioiodine uptake and scan. They should also be aware of the potential effects of iodinated contrast on thyroid function when ordering a contrast‐enhanced CT scan in patients with known thyroid disease or symptoms consistent with the presence of thyrotoxicosis. Under these circumstances consideration of thyroid dysfunction with appropriate blood tests may result in more accurate and timely diagnosis and treatment of underlying thyroid disease and enhance patient outcomes.

- ,,, et al.Serum TSH, T4, and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).J Clin Endo Metab.2002;87:489–499.

- ,,,.Differences and similarities in the diagnosis and treatment of Graves' disease in Europe, Japan, and the United States.Thyroid.1991;1:129–135.

- ,.Thyrotoxicosis. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, eds.Williams Textbook of Endocrinology.10th ed.Philadelphia:Saunders;2003:374–421.

- .Chest pain in the emergency department.JThorac Imaging.2007;22:49–55.

- ,,, et al.Cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism before and after antithyroid therapy.J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;49:71–81.

- ,.Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system.N Engl J Med.2001;344:501–509.

- ,,.Hyperthyroidism and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter.Arch Intern Med.2004;164:1675–1678.

- .Factors which influence the radioactive iodine thyroidal uptake test.Am J Med.1960;28:397–415.

- ,,, et al.The effect of varying quantities of inorganic iodide (carrier) on the urinary excretion and thyroidal accumulation of radioiodine in exophthalmic goiter.J Clin Invest.1950;29:726–738.

- ,,.Contrast material iodides: potential effects on radioactive iodine thyroid uptake.J Nucl Med.1992;33:237–238.

- ,.Iodine excess and hyperthyroidism.Thyroid.2001;11:493–500.

- ,,.Effect of iodinated contrast media on thyroid function in adults.Eur Radiol.2004;14:902–907.

- ,,,.Thyroidectomy in iodine induced thyrotoxic storm.Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes.1999;107:468–472.

- ,.Hyperthyroidism in elderly hospitalized patients.Med J Aust.1996;164:200–203.

- ,.Increasing utilization of computed tomography in the adult emergency department, 2000–2005.Emerg Radiol.2006;13:25–30.

- ,.Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure.N Engl J Med.2007;357:2277–2284.

- ,,, et al.Serum TSH, T4, and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).J Clin Endo Metab.2002;87:489–499.

- ,,,.Differences and similarities in the diagnosis and treatment of Graves' disease in Europe, Japan, and the United States.Thyroid.1991;1:129–135.

- ,.Thyrotoxicosis. In: Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, eds.Williams Textbook of Endocrinology.10th ed.Philadelphia:Saunders;2003:374–421.

- .Chest pain in the emergency department.JThorac Imaging.2007;22:49–55.

- ,,, et al.Cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism before and after antithyroid therapy.J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;49:71–81.

- ,.Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system.N Engl J Med.2001;344:501–509.

- ,,.Hyperthyroidism and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter.Arch Intern Med.2004;164:1675–1678.

- .Factors which influence the radioactive iodine thyroidal uptake test.Am J Med.1960;28:397–415.

- ,,, et al.The effect of varying quantities of inorganic iodide (carrier) on the urinary excretion and thyroidal accumulation of radioiodine in exophthalmic goiter.J Clin Invest.1950;29:726–738.

- ,,.Contrast material iodides: potential effects on radioactive iodine thyroid uptake.J Nucl Med.1992;33:237–238.

- ,.Iodine excess and hyperthyroidism.Thyroid.2001;11:493–500.

- ,,.Effect of iodinated contrast media on thyroid function in adults.Eur Radiol.2004;14:902–907.

- ,,,.Thyroidectomy in iodine induced thyrotoxic storm.Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes.1999;107:468–472.

- ,.Hyperthyroidism in elderly hospitalized patients.Med J Aust.1996;164:200–203.

- ,.Increasing utilization of computed tomography in the adult emergency department, 2000–2005.Emerg Radiol.2006;13:25–30.

- ,.Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure.N Engl J Med.2007;357:2277–2284.

Copyright © 2009 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalist‐PCP Communication Needs

Hospitalist systems focus on providing acute treatments to patients and expediting hospital discharge, sometimes without regard for the need to work in concert with community providers, leading to fragmentation of care.1 This fragmentation, particularly at the transitions of care, such as when patients move from the outpatient setting to a hospitalist system and then back to their primary care providers (PCPs), can lead to communication breakdowns and delays in care, and may compromise patient outcomes.2 Suboptimal treatments, such as medication errors and the ordering of redundant tests can occur in either setting if prior treatment information is not relayed in a timely and accurate fashion. Landrigan et al.3 described a conceptual model in 2001 that recognized the complexity of the hospitalist‐PCP communication system. Specifically, optimal care of hospitalized children includes PCPs, family members, hospitalists, and support staff while meeting the communication needs of families and PCPs. Additionally, mediating a smooth transition into and out of the hospital needs to be measured carefully.3

Previous adult studies have reported that hospitalist systems sometimes create discontinuity of patient care, which can have a negative impact on the quality of care provided to patients if there is poor communication between hospitalists and PCPs.2, 4, 5 Existing research on hospitalist‐PCP communication focuses mainly on adult hospitalist models with little known about the quality of current pediatric hospitalist‐PCP communication.

The objective of this study was to qualitatively explore issues around communication between pediatric hospitalists and PCPs. Specifically, we sought to explore the quality of communication practices and barriers to optimal communication within the hospitalist‐PCP model at a tertiary care children's hospital. The results are serving as a needs assessment to guide the design of a quality improvement project with the aim of improving pediatric hospitalist‐PCP communication.

METHODS

Study Design

Phone interviews of pediatric hospitalists and PCPs were conducted. The study was approved by the University of Utah and Primary Children's Medical Center (PCMC) Institutional Review Boards.

Setting

PCMC is a 232‐bed, tertiary‐care referral center and community hospital in Salt Lake City, UT, which serves a catchment area of approximately 1,000,000 children in 5 Intermountain West states (Utah, Idaho, Nevada, Montana, and Wyoming). In 2005, there were more than 40,000 emergency department visits and more than 11,000 hospital admissions. At the time of this study, the Division of Pediatric Inpatient Medicine (hospitalist division) included 11 full‐time equivalents. All hospitalists play a teaching role and are on faculty at the University of Utah School of Medicine. In 2005, approximately 45% of medical inpatients at PCMC were cared for by the hospitalist division, with approximately 95% cared for by resident teams.

Participants

Ten University of Utah pediatric hospitalists and 12 PCPs within our catchment area completed interviews. Verbal consent was given before study participants began the phone interview. All hospitalists from the hospitalist division, excluding the first author, completed an interview. PCPs who had referred patients to the hospitalist division in the year preceding this study (2004) were identified through a referring database kept by the hospitalist division. An attempt was made to interview physicians in multiple practice settings and geographic locations.

Inclusion criteria for PCPs included their willingness to complete the interview as well as having had patients cared for by the hospitalist division in the preceding year (2004). There was no preference given to any physicians, including physicians well‐known by the research team or more frequent users of the hospitalist division.

Instrument

To develop our questionnaire, we conducted a detailed literature search to identify issues surrounding hospitalist‐PCP communication in the adult and pediatric hospitalist literature. Search terms included: hospitalists, interprofessional relations, patient discharge, communication, follow‐up care, transitions, and primary care provider using the PubMed database, limited to English language articles from 1990 to 2005. The 6 issues for the final questionnaire were identified from published hospitalist survey questions (in both adult and pediatric literature) and published articles addressing themes regarding hospitalist and PCP attitudes (specifically in regard to the communication process).1, 2, 4, 6 These 6 issues (quality of communication, barriers to communication, methods of information sharing, key data element requirements, critical timing, and perceived benefits) were incorporated into the open‐ended and closed‐ended questionnaire (Table 1). The original draft of the questionnaire was pretested on 2 hospitalists and 3 PCPs by L.H., who has graduate level formal training and experience in the design, refinement, implementation, and evaluation of questionnaires.

| Questions |

|---|

| 1. Do you use the hospitalist system at PCMC? yes/no |

| 1a. If yes: For what % of your patients that are hospitalized do you use the hospitalist system? |

| 2. How would you rate the quality of communications between hospitalists and Primary Care Providers? |

| a: excellent; b: very good; c: good; d: fair; e: poor. |

| 2a. Why did you give it that rating? |

| 3. What barriers, if any, have you experienced in communicating with hospitalists/Primary Care Providers? |

| 4. What communication methods have been effective in the past? What suggestions do you have for improving communication methods? |

| 5. What information would you like to receive from hospitalists/Primary Care Providers regarding your patients' hospital care? |

| 6. At what points in the care process would you like to receive communications from hospitalists/Primary Care Providers? |

| 7. What suggestions do you have for improving overall communications between hospitalists and Primary Care Providers? |

| 8. Do you have access to e‐mail and use it regularly in your practice? |

| 8a. Do you have access to a fax machine and use it regularly in your practice? |

| 8b. Do you have access to a telephone and use it regularly in your practice? |

| 8c. Considering e‐mail, fax, and telephone, which of these methods do you think would be the most effective for communicating with hospitalists/Primary Care Providers? |

| 9. Do you believe that improving communications between hospitalists and Primary Care Providers would improve the quality of patient care? |

| 9a. If yes: How? |

| 9b. If no: Why not? |

| 10. Any other comments/feedback? |

Data Collection/Analysis

After consent, participants were administered the phone questionnaire by L.H. during April, May, and June 2005. Interviews were transcribed verbatim into a Microsoft Word document by a trained transcriptionist. Responses were openly coded and then grouped into the respective main topics of interest. No further interviews were conducted when theoretical saturation was obtained (ie, respondents did not identify any new themes). Themes were compared using qualitative methods.7, 8

RESULTS

Only 1 physician per practice was interviewed. No PCP who was able to be contacted declined an interview, although some did require multiple phone attempts to schedule the interview. PCPs were located in Salt Lake County (n = 6), in other Utah counties (n = 3), and in surrounding Intermountain West states (n = 3). From January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2004, we estimate that the hospitalist division cared for patients from approximately 35 practices (50% in Salt Lake County, 30% in other Utah counties, and 20% in surrounding Intermountain West states).

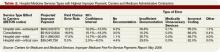

Hospitalists and PCPs agreed that overall quality of communication ranged from poor to very good (Table 2). Both parties acknowledged that significant barriers to optimal communication exist, yet the barriers differed for each group. Hospitalists and PCPs also agreed that optimal communication could improve many aspects of patient care and should take place upon discharge and admission of patients and with major clinical changes. Both hospitalists and PCPs also wanted accurate and timely information. One priority that the participants emphasized is the timely transfer of admission notification and the receipt of accurate and timely discharge summaries by PCPs.

| Hospitalists | Primary Care Providers | |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of communication | ||

| Poor | 0% | 33% |

| Fair | 50% | 17% |

| Good | 40% | 8% |

| Very good | 10% | 42% |

| Excellent | 0% | 0% |

| Barriers to communication | Lack of PCP directory; | Not knowing name and contact information of hospitalist taking care of their patient; |

| Lack of access to patients' medication or problem list; | Teaching hospital with numerous residents and students | |

| Lack of standardized system | ||

| Methods of information sharing | Electronic medical record ideal for sharing information | Electronic medical record ideal for sharing information; |

| Phone calls and faxes effective, especially if pager numbers were included | ||

| Key data elements | Diagnoses; | Diagnoses; |

| Medications; | Medications; | |

| Follow‐up plans | Follow‐up plans | |

| Critical timing | At discharge; | At discharge; |

| After admission; | After admission; | |

| Major clinical changes | Major clinical changes | |

| Perceived benefits | Improved patient satisfaction; | Improved patient satisfaction; |

| Improved follow‐up; | Improved follow‐up; | |

| Decreased medication errors; | Decreased medication errors; | |

| Increased efficiency | Increased efficiency |

Quality of Communication

Overall, both groups rated communication quality from poor to very good (Table 2). Notably, no hospitalists or PCPs rated overall quality as excellent, but 33% of PCPs rated it as poor compared to 0% of the hospitalists. Fifty‐eight percent (7/12) of PCPs used the hospitalists for 80% of their admissions to the hospital.

For hospitalists, lack of communication stemmed from busy schedules, not knowing who the PCP was, or not having the PCP contact information. Similarly, PCPs commented that they often found out their patient was admitted to the hospital only when the patient showed up in their office for a follow‐up visit. Both hospitalists and PCPs felt it was the hospitalist's job to inform and update PCPs on their patient's status while hospitalized. However, if the patient was admitted via the emergency department (ED), hospitalists felt that it was the ED's responsibility to inform the PCPs of their patients' admission.

Barriers to Communication

PCPs and hospitalists noted different barriers to optimal communication. Hospitalists identified the lack of a PCP directory, the lack of access to patients' medication and problem lists, and the lack of a standardized system to communicate with PCPs as major barriers. The delayed receipt of the discharge summary by PCPs was also viewed as a barrier by hospitalists. Pediatric hospitalists found the large variation in PCP availability as well as the variation in PCP preferred methods of communication (phone call, fax, or e‐mail) to be additional barriers. PCPs, on the other hand, struggled with the complexity of the hospital system. The fact that PCMC is a teaching hospital with numerous residents and students assisting in their patients' care, as well as not knowing the names and contact information of the hospitalists taking care of their patients, served as barriers to optimal communication. Additionally, PCPs noted the delay in receiving discharge summaries as a barrier and a source of frustration.

Methods of Information Sharing

All PCPs and hospitalists had access to telephones and faxes and used them regularly in their practices (100% for both groups). A majority of PCPs believed phone calls and faxes were effective means of information sharing, especially if pager numbers of the hospitalists were included. Some PCPs and a larger number of hospitalists thought an electronic medical record was an ideal tool for sharing information. However, PCPs appeared to have a lower rate of e‐mail access and usage compared with hospitalists.

Key Data Elements

There was agreement among PCPs and hospitalists regarding which data elements were important to be relayed among providers. PCPs and hospitalists were most interested in the following data elements upon patient discharge: diagnoses from the hospitalization, medications the patient was to take, and follow‐up plans for the patient. Hospitalists also thought PCPs could help by providing a list of current medications and a detailed past medical and social history upon admission. This information could be easily provided to the accepting hospitalist attending by phone or fax from the PCP.

Critical Timing and Perceived Benefits

Hospitalists and PCPs agreed that the most critical times for optimal hospitalist‐PCP communication were primarily at time of discharge from the hospital, after admission to the hospital, and when major clinical changes occurred. The majority of hospitalists and PCPs thought that improved communication would improve the quality of patient care through: (1) improved patient satisfaction; (2) improved quality and quantity of follow‐up; (3) decreased medication errors; and (4) increased efficiency for the PCPs and hospitalists.

DISCUSSION

Both pediatric hospitalists and PCPs agree on what information is important to transmit (diagnoses, medications, follow‐up needs, and pending laboratory test results) and critical times for communication during the hospitalization (at discharge, admission, and during major clinical changes). However, there was discrepancy in the barriers to optimal communication for each group. Identifying and addressing these barriers can help both hospitalists and PCPs implement targeted interventions aimed at improving communication. As the number of pediatric hospitalist programs increases, the risk for hospitalist‐PCP communication breakdowns, which can have a negative impact on patient care, also increases.

Previous adult studies describe the scope of the problem around poor communication between hospitalists and PCPs.1, 912 Kripalani et al.10 reported recently that delays and omissions in communication are common at hospital discharge among adult hospitalists and that computer‐generated summaries, educational interventions, and standardized formats may facilitate more timely transfer of pertinent information. However, there is limited data on pediatric hospitalist‐PCP communication. Srivastava et al.5 found that 60% of community physicians thought hospitalist systems may impair communication with PCPs when evaluating community and hospital‐based physicians' attitudes regarding pediatric hospitalist systems.

PCPs can feel left out when their patients are cared for by hospitalists.13 One PCP in our study commented: Include the referral doc as part of the team. We're the ones who will take care of them after discharge. It seems like an autonomous thing down there and we're excluded from the patient care team. Additionally, patients want their PCPs to remain involved in their care as they transition into and out of the hospital setting.1, 13

The continuity visit model has been proposed by Wachter and Pantilat14 to describe a clinical encounter between the primary physician and hospitalized patient, when the patient has a different physician of record. In this model, the PCP can endorse the hospitalist model and the individual hospitalist, notice subtle findings that differ from the patient's baseline, and help clarify patient preferences regarding difficult situations by drawing on their previous relationship with the patient. This visit may also benefit the PCP by providing insights into the patient's illness, personality, or social support that he or she was unaware of previously. However, in order for the continuity visit to exist, the PCP has to be informed of their patient's admission in the first place. Ethical dilemmas also have been raised regarding who bears primary responsibility for maintaining open lines of communication when patients are hospitalized.15 Lo15 advocates that PCPs can and should be involved in meaningful ways in the inpatient care of their patients even when they are not acting as the treating physicians. Specifically, he suggests that PCPs personally visit particularly ill patients or those with difficult diagnoses and use frequent phone calls to all admitted patients.

Beyond telephone calls and continuity visits, hospitalists and PCPs rely on discharge summaries as a key part of the information transfer about a patient's hospitalization.1, 16, 17 These documents are rendered useless if they are inaccurate, illegible, or not delivered in a timely manner.18 In a study of California family physicians, discharge summaries were thought to be too detailed by 84% of PCPs, and reportedly arrived before the patient's first follow‐up appointment only 33% of the time.1 O'Leary et al.19 found that 41% of the Department of Medicine physicians surveyed believed that at least 1 of their patients hospitalized in the previous 6 months had experienced a preventable adverse event related to poor transfer of information at discharge. In our study, PCPs noted that discharge summaries often arrived in their offices well after the patient had been seen for their follow‐up appointment.

Both hospitalists and PCPs agree that a concise and precise discharge summary should include an overview of the hospitalization with important details highlighted. Similar to the findings of Pantilat et al.,1 in our study PCPs specifically want detailed information with regard to diagnoses, discharge medications, and what to expect when they see the patient in their clinic. Follow‐up phone calls to PCPs to see that they received written information and if they require further details is 1 solution to ensuring good follow‐up, yet this adds to the burden of communication and could be an additional barrier.

The teaching institutions in which physicians train also pose unique obstacles to optimal communication. In academic medical centers, medical students and residents perform a majority of the discharge duties (eg, writing prescriptions, dictating discharge summaries, making follow‐up appointments, and calling PCPs), and teaching these trainees the importance of timely and accurate communication becomes an added challenge. Educators have to find novel ways of providing incentives to residents and medical students to get them to effectively participate in this process. Plauth et al.20 reports that hospitalists feel they needed better training in residency around communicating, noting a meaningful underemphasis during residency training in regard to communication with referring physicians. These skills should be taught in medical school and supported by both hospitalists and PCPs throughout residency training.

Both hospitalists and PCPs also want easy and reliable ways to access their colleagues, which ideally would be automatic. One PCP commented: a weekly or semiweekly phone call would be nice. Another suggested to: fax a short note. One hospitalist acknowledged: a systematic approach would be betterwhether a fax or telephone call and make sure there is a way of checking to make sure the communication has happened. Another hospitalist simply remarked: it needs to be done on every patient.

Thus, it seems an improved communication system should be flexible enough to accommodate unique provider preferences, such as communication via phone, fax, or e‐mail. This is demonstrated by 1 PCP who preferred the phone, but most convenient is the periodic fax updates. I don't have to be taken away from seeing patients.

Lo15 calls for a standard to be established for delivering care within the patient‐PCP‐hospitalist triad. Phone calls and faxes are 2 readily available methods of communication. However, the frequent back‐and‐forth of missed calls, unreturned calls, and days‐off is certainly a factor in determining efficiency and effectiveness of phone calls.

E‐mail, if it is widely used by all participants, may be an effective option for delivery that could provide confirmation of receipt. However, the lack of universal e‐mail usage by all providers remains a barrier. Questions as to which method is more time consuming and for whom, need to be studied further. Patient confidentiality also requires that this protected health information arrive in the proper hands. Personal relationships can also contribute to successful communication. One provider may be more likely to contact another if they know each other through some personal connection, such as medical school, residency, or a social group.

Our study has several limitations. The sample size was small. We obtained responses from a sample of key stakeholders in the hospitalist‐PCP communication process. We were limited by the number of hospitalists at our institution as well as the interest and availability of PCPs to respond. We are unable to determine the total number of patients by respondent PCP practice cared for by the hospitalist division. This could influence the results depending on whether the respondent PCP was a frequent or infrequent utilizer of the hospitalist system. However, we feel reassured that we are not missing important information, because in our methods, a priori, we had intended to stop interviewing PCPs once theoretical saturation had been reached (ie, respondents did not identify any new information). In our study, that occurred with 12 PCPs.

We attempted to interview a single physician in a number of different practice settings in order to gain insight into the perceptions of that individual as well as those of their partners. The views expressed by these individuals may not represent the views of hospitalists and PCPs outside of our practice area. Furthermore, PCMC serves as both a community pediatric hospital and a tertiary‐referral center for a large area, yet the current experience of 1 hospitalist division and 1 cohort of referring PCPs may contain regional variation that contributed bias to the responses.

Selection bias may have been introduced in our study by the inherent nature of phone interviews. We interviewed only providers with previous communication experience with our hospitalist division. These providers may have had a vested interest in the communication process. We did not interview those PCPs who did not have any communication with our hospitalist division or those who may have used the hospitalist division previously and decided to no longer use the division. Interviewing these groups may have provided additional insight into the communication issues mentioned here. Additionally, useful information could have been gleaned from trying to find out more from the 33% of PCPs who felt communication was poor. We anticipate further studies exploring this issue in more depth.

Future Directions

As a result of this study, we have implemented several interventions to improve information sharing between hospitalists and PCPs, including: 1) we updated current contact information (including names of physicians, office addresses, phone numbers, fax numbers, and e‐mail addresses) for all PCPs in our catchment area along with their preferred methods of communication; 2) we worked with the transcription services to automatically add PCP addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers to dictated notes, eliminating time wasted searching for contact information; and 3) we standardized key data elements in admission history and physicals and discharge notes to increase the efficiency of the communication process.

Furthermore, we have implemented a standardized system to facilitate communication with PCPs. This system includes an automated process to notify PCPs of their patient's hospital admission, including the admission date, preliminary diagnoses, and responsible physician's contact information. We are currently undertaking a quality improvement project aimed at achieving timely transfer of discharge information to PCPs, including medications, follow‐up appointments, and a succinct hospital summary. Finally, establishing an evaluation process to monitor both successes and failures will be paramount to any interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

Hospitalists and PCPs agree that overall quality of communication ranges from poor to very good. Both PCPs and pediatric hospitalists acknowledge that significant barriers to optimal communication exist, yet the barriers differ for each group. They also agree that optimal communication would improve many aspects of patient care and should take place upon discharge and admission of patients and with major clinical changes.

Pediatric hospitalists and PCPs identified issues around optimal communication similar to those noted in the adult hospital medicine literature. Interventions to improve pediatric hospitalist‐PCP communication should at least address these 6 issues: (1) quality of communication; (2) barriers to communication; (3) methods of information sharing; (4) key data element requirements; (5) critical timing; and (6) perceived benefits. Such interventions will likely improve hospitalist‐PCP communication and potentially improve the quality of patient care. However, future studies will need to demonstrate the link between improved hospitalist‐PCP communication and improved patient care and outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Flory Nkoy, MD, MPH, MS, for his help in manuscript preparation and critical review.

- ,,,.Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists.Am J Med.2001;111(9B):15S–20S.

- ,,,,,.Physician attitudes toward and prevalence of the hospitalist model of care: results of a national survey.Am J Med.2000;109(8):648–653.

- ,,,,,.Pediatric hospitalists: what do we know, and where do we go from here?Ambul Pediatr.2001;1(6):340–345.

- ,,.Physician views on caring for hospitalized patients and the hospitalist model of inpatient care.J Gen Intern Med.2001;16(2):116–119.

- ,,,,,.Community and hospital‐based physicians' attitudes regarding pediatric hospitalist systems.Pediatrics.2005;115(1):34–38.

- ,.The patient provider relationship and the hospitalist movement. Introduction.Dis Mon.2002;48(4):189–190.

- ,.Rigour and qualitative research.BMJ.1995;311(6997):109–112.

- ,.Needs assessment in post graduate medical education: a review.Med Educ Online.2001;7:1–8.

- ,,,.How physicians perceive hospitalist services after implementation: anticipation vs reality.Arch Intern Med.2003;163(19):2330–2336.

- ,,,,,.Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297(8):831–841.

- ,,.Generalist‐subspecialist communication for children with chronic conditions: a regional physician survey.Pediatrics.2003;112(6 Pt 1):1314–1320.

- ,,,,,.Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process.J Gen Intern Med.2000;15(9):626–631.

- ,,.How do patients view the role of the primary care physician in inpatient care?Dis Mon.2002;48(4):230–238.

- ,.The “continuity visit” and the hospitalist model of care.Dis Mon.2002;48(4):267–272.

- .Ethical and policy implications of hospitalist systems.Dis Mon.2002;48(4):281–290.