User login

Inattention to history dooms patient to repeat it ... Persistent breast lumps but no biopsy ... more

When an atypical presentation is missed

A 50-YEAR-OLD MORBIDLY OBESE MAN went to his family physician with complaints of back pain radiating to the chest, episodic shortness of breath, and diaphoresis. He had a history of uncontrolled high cholesterol. An electrocardiogram showed a Q wave in an inferior lead, which the physician attributed to an old infarct. The doctor didn’t order cardiac enzymes because his office couldn’t do the test.

The physician discharged the patient with a diagnosis of chest pain and a prescription for acetaminophen and hydrocodone. He was scheduled to see a cardiologist in 10 days, but no further cardiology workup was done.

The man died an hour later.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The doctor was negligent in failing to recognize acute coronary syndrome resulting from obstructive coronary artery disease.

THE DEFENSE The patient was discharged in stable condition; cardiac arrest so soon after discharge increased the likelihood that the patient would have suffered sudden cardiac death even if he’d received emergency treatment.

VERDICT $825,000 Virginia settlement.

COMMENT Common, serious problems can present in atypical ways. A high index of suspicion for coronary artery disease in high-risk patients with thoracic pain and shortness of breath—as well as a rapid, thorough evaluation—should keep you out of court (and your patients alive).

Treatment delayed while infection spins out of control

VOMITING, DIARRHEA, AND PAIN AND SWELLING IN THE RIGHT HAND led to an ambulance trip to the emergency department (ED) for a 31-year-old woman. The ED physician diagnosed cellulitis and sepsis. Later that day, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, where the admitting physician noted lethargy and confusion, tachycardia, and blueness of the middle and ring fingers on the woman’s right hand. Her medical record suggested that she might have been bitten by a spider.

The patient spent the next 3 days in the ICU in deteriorating condition. She was then transferred to another hospital for treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. She underwent a number of surgeries, including amputation of her right middle and ring fingers, which resulted in significant scarring and deformity of her right hand and forearm.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The defendants were negligent in failing to diagnose necrotizing fasciitis promptly.

THE DEFENSE The defendants who didn’t settle denied any negligence.

VERDICT $80,000 Indiana settlement with the defendant hospital and 1 physician; Indiana defense verdict for the other defendants.

COMMENT When serious infections don’t resolve in a timely manner, expert consultation is imperative.

Inattention to history dooms patient to repeat it

HEADACHES, FEVER, CHILLS, AND JOINT AND MUSCLE PAIN prompted a 42-year-old man to visit his medical group. He told the nurse practitioner (NP) who examined him that his mother had died of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. The NP diagnosed a viral syndrome, ordered blood tests, and sent the patient home with prescriptions for antibiotics and pain medication. The patient didn’t undergo a neurologic examination.

About 2 weeks later, while continuing to suffer from headaches, the man collapsed and was found unresponsive. A computed tomography scan of his brain showed a subarachnoid hemorrhage and intercerebral hematoma. Further tests revealed a ruptured complex aneurysm, the cause of the hemorrhage. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient fell into a coma and died 3 months later.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The NP should have realized that the patient was at high risk of an aneurysm.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.5 million New Jersey settlement.

COMMENT I provided expert opinion in a similar case a couple of years ago. The lesson: Pay attention to the family history!

Persistent breast lumps, but no biopsy

ABOUT 3 YEARS AFTER GIVING BIRTH, a 38-year-old woman, who was still breastfeeding, went to her primary care physician complaining of pain, a dime-sized lump in her breast, and discharge from the nipple. The patient’s 2-year-old breast implants limited examination by the nurse practitioner (NP) who saw her. Galactorrhea was diagnosed and the woman was told to stop breastfeeding, apply ice packs, and come back in 2 weeks.

When the patient returned, her only remaining complaint was the lump, which the primary care physician attributed to mastitis. At a routine check-up 5 months later, the patient continued to complain of breast lumps. No breast exam was done, but the woman was referred to a gynecologist. An appointment for a breast ultrasound was scheduled for later in the month, but the patient said she didn’t receive notification of the date.

Metastatic breast cancer was subsequently diagnosed, and the woman died about 3 years later.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The NP and primary care physician should have recommended a biopsy sooner.

THE DEFENSE The care given was proper; an earlier diagnosis wouldn’t have changed the outcome.

VERDICT $750,000 Massachusetts settlement.

COMMENT Failure to recommend biopsy of breast lumps is a leading cause of malpractice cases against family physicians. All persistent breast lumps require referral for biopsy— regardless of the patient’s age.

A red flag that was ignored for too long

A MAN IN HIS EARLY 30S consulted an orthopedist for mid-back pain. The doctor took radiographs of the man’s lower back and reported that he saw nothing amiss. When the man returned 3 months later complaining of the same kind of pain, the orthopedist examined him, prescribed a muscle relaxant, and sent him for physical therapy. The physician did not take any radiographs.

Four months later, the patient came back with pain in his mid-back and ribs. The orthopedist ordered radiographs of the ribs, which were read as normal.

After 18 months, the patient consulted another orthopedist, who ordered a magnetic resonance imaging scan and diagnosed a spinal plasmacytoma at levels T9 to T11. The tumor had destroyed some vertebrae and was compressing the spinal cord.

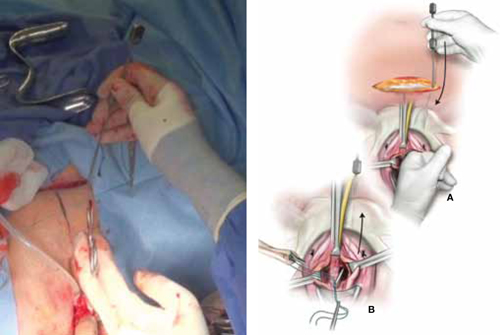

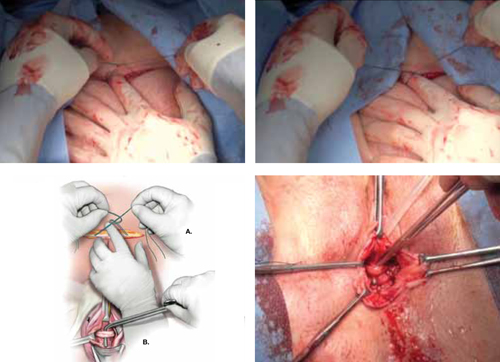

The patient underwent surgery to remove the tumor and insert screws from T6 to L2 to stabilize the spine. He wore a brace around his torso for months and had a bone marrow transplant. The patient couldn’t return to work.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The tumor was clearly visible on the radiographs taken at the patient’s third visit to the first orthopedist; thoracic spine radiographs should have been taken at the previous 2 visits.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $875,000 New Jersey settlement.

COMMENT Current guidelines recommend a red flags approach to imaging. This patient had a red flag—unremitting pain. When back pain persists unabated, it’s time for a thorough evaluation.

When an atypical presentation is missed

A 50-YEAR-OLD MORBIDLY OBESE MAN went to his family physician with complaints of back pain radiating to the chest, episodic shortness of breath, and diaphoresis. He had a history of uncontrolled high cholesterol. An electrocardiogram showed a Q wave in an inferior lead, which the physician attributed to an old infarct. The doctor didn’t order cardiac enzymes because his office couldn’t do the test.

The physician discharged the patient with a diagnosis of chest pain and a prescription for acetaminophen and hydrocodone. He was scheduled to see a cardiologist in 10 days, but no further cardiology workup was done.

The man died an hour later.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The doctor was negligent in failing to recognize acute coronary syndrome resulting from obstructive coronary artery disease.

THE DEFENSE The patient was discharged in stable condition; cardiac arrest so soon after discharge increased the likelihood that the patient would have suffered sudden cardiac death even if he’d received emergency treatment.

VERDICT $825,000 Virginia settlement.

COMMENT Common, serious problems can present in atypical ways. A high index of suspicion for coronary artery disease in high-risk patients with thoracic pain and shortness of breath—as well as a rapid, thorough evaluation—should keep you out of court (and your patients alive).

Treatment delayed while infection spins out of control

VOMITING, DIARRHEA, AND PAIN AND SWELLING IN THE RIGHT HAND led to an ambulance trip to the emergency department (ED) for a 31-year-old woman. The ED physician diagnosed cellulitis and sepsis. Later that day, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, where the admitting physician noted lethargy and confusion, tachycardia, and blueness of the middle and ring fingers on the woman’s right hand. Her medical record suggested that she might have been bitten by a spider.

The patient spent the next 3 days in the ICU in deteriorating condition. She was then transferred to another hospital for treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. She underwent a number of surgeries, including amputation of her right middle and ring fingers, which resulted in significant scarring and deformity of her right hand and forearm.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The defendants were negligent in failing to diagnose necrotizing fasciitis promptly.

THE DEFENSE The defendants who didn’t settle denied any negligence.

VERDICT $80,000 Indiana settlement with the defendant hospital and 1 physician; Indiana defense verdict for the other defendants.

COMMENT When serious infections don’t resolve in a timely manner, expert consultation is imperative.

Inattention to history dooms patient to repeat it

HEADACHES, FEVER, CHILLS, AND JOINT AND MUSCLE PAIN prompted a 42-year-old man to visit his medical group. He told the nurse practitioner (NP) who examined him that his mother had died of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. The NP diagnosed a viral syndrome, ordered blood tests, and sent the patient home with prescriptions for antibiotics and pain medication. The patient didn’t undergo a neurologic examination.

About 2 weeks later, while continuing to suffer from headaches, the man collapsed and was found unresponsive. A computed tomography scan of his brain showed a subarachnoid hemorrhage and intercerebral hematoma. Further tests revealed a ruptured complex aneurysm, the cause of the hemorrhage. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient fell into a coma and died 3 months later.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The NP should have realized that the patient was at high risk of an aneurysm.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.5 million New Jersey settlement.

COMMENT I provided expert opinion in a similar case a couple of years ago. The lesson: Pay attention to the family history!

Persistent breast lumps, but no biopsy

ABOUT 3 YEARS AFTER GIVING BIRTH, a 38-year-old woman, who was still breastfeeding, went to her primary care physician complaining of pain, a dime-sized lump in her breast, and discharge from the nipple. The patient’s 2-year-old breast implants limited examination by the nurse practitioner (NP) who saw her. Galactorrhea was diagnosed and the woman was told to stop breastfeeding, apply ice packs, and come back in 2 weeks.

When the patient returned, her only remaining complaint was the lump, which the primary care physician attributed to mastitis. At a routine check-up 5 months later, the patient continued to complain of breast lumps. No breast exam was done, but the woman was referred to a gynecologist. An appointment for a breast ultrasound was scheduled for later in the month, but the patient said she didn’t receive notification of the date.

Metastatic breast cancer was subsequently diagnosed, and the woman died about 3 years later.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The NP and primary care physician should have recommended a biopsy sooner.

THE DEFENSE The care given was proper; an earlier diagnosis wouldn’t have changed the outcome.

VERDICT $750,000 Massachusetts settlement.

COMMENT Failure to recommend biopsy of breast lumps is a leading cause of malpractice cases against family physicians. All persistent breast lumps require referral for biopsy— regardless of the patient’s age.

A red flag that was ignored for too long

A MAN IN HIS EARLY 30S consulted an orthopedist for mid-back pain. The doctor took radiographs of the man’s lower back and reported that he saw nothing amiss. When the man returned 3 months later complaining of the same kind of pain, the orthopedist examined him, prescribed a muscle relaxant, and sent him for physical therapy. The physician did not take any radiographs.

Four months later, the patient came back with pain in his mid-back and ribs. The orthopedist ordered radiographs of the ribs, which were read as normal.

After 18 months, the patient consulted another orthopedist, who ordered a magnetic resonance imaging scan and diagnosed a spinal plasmacytoma at levels T9 to T11. The tumor had destroyed some vertebrae and was compressing the spinal cord.

The patient underwent surgery to remove the tumor and insert screws from T6 to L2 to stabilize the spine. He wore a brace around his torso for months and had a bone marrow transplant. The patient couldn’t return to work.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The tumor was clearly visible on the radiographs taken at the patient’s third visit to the first orthopedist; thoracic spine radiographs should have been taken at the previous 2 visits.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $875,000 New Jersey settlement.

COMMENT Current guidelines recommend a red flags approach to imaging. This patient had a red flag—unremitting pain. When back pain persists unabated, it’s time for a thorough evaluation.

When an atypical presentation is missed

A 50-YEAR-OLD MORBIDLY OBESE MAN went to his family physician with complaints of back pain radiating to the chest, episodic shortness of breath, and diaphoresis. He had a history of uncontrolled high cholesterol. An electrocardiogram showed a Q wave in an inferior lead, which the physician attributed to an old infarct. The doctor didn’t order cardiac enzymes because his office couldn’t do the test.

The physician discharged the patient with a diagnosis of chest pain and a prescription for acetaminophen and hydrocodone. He was scheduled to see a cardiologist in 10 days, but no further cardiology workup was done.

The man died an hour later.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The doctor was negligent in failing to recognize acute coronary syndrome resulting from obstructive coronary artery disease.

THE DEFENSE The patient was discharged in stable condition; cardiac arrest so soon after discharge increased the likelihood that the patient would have suffered sudden cardiac death even if he’d received emergency treatment.

VERDICT $825,000 Virginia settlement.

COMMENT Common, serious problems can present in atypical ways. A high index of suspicion for coronary artery disease in high-risk patients with thoracic pain and shortness of breath—as well as a rapid, thorough evaluation—should keep you out of court (and your patients alive).

Treatment delayed while infection spins out of control

VOMITING, DIARRHEA, AND PAIN AND SWELLING IN THE RIGHT HAND led to an ambulance trip to the emergency department (ED) for a 31-year-old woman. The ED physician diagnosed cellulitis and sepsis. Later that day, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, where the admitting physician noted lethargy and confusion, tachycardia, and blueness of the middle and ring fingers on the woman’s right hand. Her medical record suggested that she might have been bitten by a spider.

The patient spent the next 3 days in the ICU in deteriorating condition. She was then transferred to another hospital for treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. She underwent a number of surgeries, including amputation of her right middle and ring fingers, which resulted in significant scarring and deformity of her right hand and forearm.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The defendants were negligent in failing to diagnose necrotizing fasciitis promptly.

THE DEFENSE The defendants who didn’t settle denied any negligence.

VERDICT $80,000 Indiana settlement with the defendant hospital and 1 physician; Indiana defense verdict for the other defendants.

COMMENT When serious infections don’t resolve in a timely manner, expert consultation is imperative.

Inattention to history dooms patient to repeat it

HEADACHES, FEVER, CHILLS, AND JOINT AND MUSCLE PAIN prompted a 42-year-old man to visit his medical group. He told the nurse practitioner (NP) who examined him that his mother had died of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. The NP diagnosed a viral syndrome, ordered blood tests, and sent the patient home with prescriptions for antibiotics and pain medication. The patient didn’t undergo a neurologic examination.

About 2 weeks later, while continuing to suffer from headaches, the man collapsed and was found unresponsive. A computed tomography scan of his brain showed a subarachnoid hemorrhage and intercerebral hematoma. Further tests revealed a ruptured complex aneurysm, the cause of the hemorrhage. Despite aggressive treatment, the patient fell into a coma and died 3 months later.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The NP should have realized that the patient was at high risk of an aneurysm.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.5 million New Jersey settlement.

COMMENT I provided expert opinion in a similar case a couple of years ago. The lesson: Pay attention to the family history!

Persistent breast lumps, but no biopsy

ABOUT 3 YEARS AFTER GIVING BIRTH, a 38-year-old woman, who was still breastfeeding, went to her primary care physician complaining of pain, a dime-sized lump in her breast, and discharge from the nipple. The patient’s 2-year-old breast implants limited examination by the nurse practitioner (NP) who saw her. Galactorrhea was diagnosed and the woman was told to stop breastfeeding, apply ice packs, and come back in 2 weeks.

When the patient returned, her only remaining complaint was the lump, which the primary care physician attributed to mastitis. At a routine check-up 5 months later, the patient continued to complain of breast lumps. No breast exam was done, but the woman was referred to a gynecologist. An appointment for a breast ultrasound was scheduled for later in the month, but the patient said she didn’t receive notification of the date.

Metastatic breast cancer was subsequently diagnosed, and the woman died about 3 years later.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The NP and primary care physician should have recommended a biopsy sooner.

THE DEFENSE The care given was proper; an earlier diagnosis wouldn’t have changed the outcome.

VERDICT $750,000 Massachusetts settlement.

COMMENT Failure to recommend biopsy of breast lumps is a leading cause of malpractice cases against family physicians. All persistent breast lumps require referral for biopsy— regardless of the patient’s age.

A red flag that was ignored for too long

A MAN IN HIS EARLY 30S consulted an orthopedist for mid-back pain. The doctor took radiographs of the man’s lower back and reported that he saw nothing amiss. When the man returned 3 months later complaining of the same kind of pain, the orthopedist examined him, prescribed a muscle relaxant, and sent him for physical therapy. The physician did not take any radiographs.

Four months later, the patient came back with pain in his mid-back and ribs. The orthopedist ordered radiographs of the ribs, which were read as normal.

After 18 months, the patient consulted another orthopedist, who ordered a magnetic resonance imaging scan and diagnosed a spinal plasmacytoma at levels T9 to T11. The tumor had destroyed some vertebrae and was compressing the spinal cord.

The patient underwent surgery to remove the tumor and insert screws from T6 to L2 to stabilize the spine. He wore a brace around his torso for months and had a bone marrow transplant. The patient couldn’t return to work.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The tumor was clearly visible on the radiographs taken at the patient’s third visit to the first orthopedist; thoracic spine radiographs should have been taken at the previous 2 visits.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $875,000 New Jersey settlement.

COMMENT Current guidelines recommend a red flags approach to imaging. This patient had a red flag—unremitting pain. When back pain persists unabated, it’s time for a thorough evaluation.

Patient overusing antianxiety meds? Say so (in a letter)

Express your concern about long-term use of benzodiazepines in a letter—a simple intervention that patients often respond to by reducing or eliminating their use of the drug.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a well-done meta-analysis with few clinical trials.

Mugunthan K, McGuire T, Glasziou P. Minimal interventions to decrease long-term use of benzodiazepines in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e573-e578.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 65-year-old patient has been taking lorazepam for insomnia for more than a year. You are concerned about her ongoing use of the benzodiazepine and want to wean her from the medication. What strategies can you use to decrease, or eliminate, her use of the drug?

Benzodiazepines are commonly used medications, with an estimated 12-month prevalence of use of 8.6% in the United States.2 While short-term use of these antianxiety medications can be effective, long-term use (defined as regular use for >3 months) is associated with significant risk.

Abuse linked to chronic use

Prescription drug abuse has recently become the nation’s leading cause of accidental death, overtaking motor vehicle accidents.3 And tranquilizers, including benzodiazepines, are the second most abused prescription medication, after pain relievers.4 In addition to dependence and withdrawal, chronic use of benzodiazepines is associated with daytime somnolence, blunted reflexes, memory loss, cognitive impairment, and an increased risk of falls and fractures—particularly in older patients.5

Reducing long-term use of benzodiazepines in a primary care setting is important but challenging. Until recently, most of the successful strategies reported were resource intensive and required multiple office visits.6

STUDY SUMMARY: Brief interventions are often effective

This study was a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in which “minimal interventions” were compared with usual care for their effectiveness in reducing or eliminating benzodiazepine use in primary care patients. A minimal intervention was defined as a letter, self-help information, or short consultation with a primary care provider. In each case, the message to the patient included (a) an expression of concern about the patient’s long-term use of the medication, (b) information about the potential adverse effects of the medication, and (c) advice on how to gradually reduce or stop using it.

Three studies met the inclusion criteria for randomization, blinding, and analysis by intention-to-treat.7-9 All 3 (n=615) had a 6-month follow-up period, a higher proportion of women (>60%), and participants with a mean age >60 years. Few patients were lost to follow-up; withdrawal rates were low and similar in all 3 studies. Each study compared a letter with usual care; 2 of the 3 had a third arm that included both a letter and a short consultation.

Pooled results from the studies showed twice the reduction in benzodiazepine use in the intervention groups compared with the control groups (risk ratio [RR]=2.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-2.8; P< .001). The RR for cessation of benzodiazepine use was 2.3 (95% CI, 1.3-4.2; P= .003). The number needed to treat for a reduction or cessation of use was 12. The studies reported benzodiazepine reduction rates of 20% to 35% in the intervention groups vs 6% to 15% in the usual care groups.7-9 There appeared to be no additional benefit to adding the brief consultation compared with the letter alone.

WHAT’S NEW?: This strategy is easy to implement

While many methods to reduce benzodiazepine use have been studied, most involved levels of skill and resources that are not feasible for widespread use. This study found that a letter, stating the risks of continued use of the medication and providing a weaning schedule and tips for handling withdrawal, can be effective in reducing chronic use in a small but significant part of the population.

CAVEATS: Effects of withdrawal went unaddressed

The study did not adequately address the adverse effects of withdrawal from benzodiazepines, with one of the studies reporting significantly worse qualitative (but not quantitative) withdrawal symptoms at 6 months.7 This is of particular concern, as withdrawal symptoms are associated with the potential for relapse and concomitant abuse of other drugs and alcohol. We recommend that primary care physicians screen for substance abuse prior to the intervention and arrange for adequate follow-up.

All 3 studies in the meta-analysis lasted 6 months; no longer-term outcomes were reported. In addition, the study did not yield enough information to identify patients who would be most likely to respond to this brief intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Determining which patients to target

Identifying patients who are appropriate candidates for this brief intervention and providing adequate monitoring for adverse effects of withdrawal are the main challenges of this practice changer. Nonetheless, chronic benzodiazepine use is of considerable concern, and we believe that this is a useful, and manageable intervention.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Mugunthan K, McGuire T, Glasziou P. Minimal interventions to decrease long-term use of benzodiazepines in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e573-e578.

2. Tyrer PJ. Benzodiazepines on trial. Br Med J. 1984;288:1101-1102.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: Leading causes for 2008. June 6, 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr60/nvsr60_06.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Topics in brief: Prescription drug abuse. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/topics-in-brief/prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed October 11, 2012.

5. Morin CM, Bastien C, Guay B, et al. Randomized clinical trail of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:332-342.

6. Oude Voshaar RC, Couvee JE, van Balkorn AJ, et al. Strategies for discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine use-meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatr. 2006;189:213-220.

7. Bashir K, King M, Ashworth M. Controlled evaluation of brief intervention by general practitioners to reduce chronic use of benzodiazepines. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:408-412.

8. Cormack MA, Sweeney KG, Hughes-Jones H, et al. Evaluation of an easy, cost-effective strategy to cut benzodiazepine use in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:5-8

9. Heather NA, Bowie A, Ashton H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of two brief interventions against long-term benzodiazepine use: outcome of intervention. Addict Res Theory. 2004;12:141-145.

Express your concern about long-term use of benzodiazepines in a letter—a simple intervention that patients often respond to by reducing or eliminating their use of the drug.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a well-done meta-analysis with few clinical trials.

Mugunthan K, McGuire T, Glasziou P. Minimal interventions to decrease long-term use of benzodiazepines in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e573-e578.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 65-year-old patient has been taking lorazepam for insomnia for more than a year. You are concerned about her ongoing use of the benzodiazepine and want to wean her from the medication. What strategies can you use to decrease, or eliminate, her use of the drug?

Benzodiazepines are commonly used medications, with an estimated 12-month prevalence of use of 8.6% in the United States.2 While short-term use of these antianxiety medications can be effective, long-term use (defined as regular use for >3 months) is associated with significant risk.

Abuse linked to chronic use

Prescription drug abuse has recently become the nation’s leading cause of accidental death, overtaking motor vehicle accidents.3 And tranquilizers, including benzodiazepines, are the second most abused prescription medication, after pain relievers.4 In addition to dependence and withdrawal, chronic use of benzodiazepines is associated with daytime somnolence, blunted reflexes, memory loss, cognitive impairment, and an increased risk of falls and fractures—particularly in older patients.5

Reducing long-term use of benzodiazepines in a primary care setting is important but challenging. Until recently, most of the successful strategies reported were resource intensive and required multiple office visits.6

STUDY SUMMARY: Brief interventions are often effective

This study was a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in which “minimal interventions” were compared with usual care for their effectiveness in reducing or eliminating benzodiazepine use in primary care patients. A minimal intervention was defined as a letter, self-help information, or short consultation with a primary care provider. In each case, the message to the patient included (a) an expression of concern about the patient’s long-term use of the medication, (b) information about the potential adverse effects of the medication, and (c) advice on how to gradually reduce or stop using it.

Three studies met the inclusion criteria for randomization, blinding, and analysis by intention-to-treat.7-9 All 3 (n=615) had a 6-month follow-up period, a higher proportion of women (>60%), and participants with a mean age >60 years. Few patients were lost to follow-up; withdrawal rates were low and similar in all 3 studies. Each study compared a letter with usual care; 2 of the 3 had a third arm that included both a letter and a short consultation.

Pooled results from the studies showed twice the reduction in benzodiazepine use in the intervention groups compared with the control groups (risk ratio [RR]=2.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-2.8; P< .001). The RR for cessation of benzodiazepine use was 2.3 (95% CI, 1.3-4.2; P= .003). The number needed to treat for a reduction or cessation of use was 12. The studies reported benzodiazepine reduction rates of 20% to 35% in the intervention groups vs 6% to 15% in the usual care groups.7-9 There appeared to be no additional benefit to adding the brief consultation compared with the letter alone.

WHAT’S NEW?: This strategy is easy to implement

While many methods to reduce benzodiazepine use have been studied, most involved levels of skill and resources that are not feasible for widespread use. This study found that a letter, stating the risks of continued use of the medication and providing a weaning schedule and tips for handling withdrawal, can be effective in reducing chronic use in a small but significant part of the population.

CAVEATS: Effects of withdrawal went unaddressed

The study did not adequately address the adverse effects of withdrawal from benzodiazepines, with one of the studies reporting significantly worse qualitative (but not quantitative) withdrawal symptoms at 6 months.7 This is of particular concern, as withdrawal symptoms are associated with the potential for relapse and concomitant abuse of other drugs and alcohol. We recommend that primary care physicians screen for substance abuse prior to the intervention and arrange for adequate follow-up.

All 3 studies in the meta-analysis lasted 6 months; no longer-term outcomes were reported. In addition, the study did not yield enough information to identify patients who would be most likely to respond to this brief intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Determining which patients to target

Identifying patients who are appropriate candidates for this brief intervention and providing adequate monitoring for adverse effects of withdrawal are the main challenges of this practice changer. Nonetheless, chronic benzodiazepine use is of considerable concern, and we believe that this is a useful, and manageable intervention.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Express your concern about long-term use of benzodiazepines in a letter—a simple intervention that patients often respond to by reducing or eliminating their use of the drug.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a well-done meta-analysis with few clinical trials.

Mugunthan K, McGuire T, Glasziou P. Minimal interventions to decrease long-term use of benzodiazepines in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e573-e578.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 65-year-old patient has been taking lorazepam for insomnia for more than a year. You are concerned about her ongoing use of the benzodiazepine and want to wean her from the medication. What strategies can you use to decrease, or eliminate, her use of the drug?

Benzodiazepines are commonly used medications, with an estimated 12-month prevalence of use of 8.6% in the United States.2 While short-term use of these antianxiety medications can be effective, long-term use (defined as regular use for >3 months) is associated with significant risk.

Abuse linked to chronic use

Prescription drug abuse has recently become the nation’s leading cause of accidental death, overtaking motor vehicle accidents.3 And tranquilizers, including benzodiazepines, are the second most abused prescription medication, after pain relievers.4 In addition to dependence and withdrawal, chronic use of benzodiazepines is associated with daytime somnolence, blunted reflexes, memory loss, cognitive impairment, and an increased risk of falls and fractures—particularly in older patients.5

Reducing long-term use of benzodiazepines in a primary care setting is important but challenging. Until recently, most of the successful strategies reported were resource intensive and required multiple office visits.6

STUDY SUMMARY: Brief interventions are often effective

This study was a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in which “minimal interventions” were compared with usual care for their effectiveness in reducing or eliminating benzodiazepine use in primary care patients. A minimal intervention was defined as a letter, self-help information, or short consultation with a primary care provider. In each case, the message to the patient included (a) an expression of concern about the patient’s long-term use of the medication, (b) information about the potential adverse effects of the medication, and (c) advice on how to gradually reduce or stop using it.

Three studies met the inclusion criteria for randomization, blinding, and analysis by intention-to-treat.7-9 All 3 (n=615) had a 6-month follow-up period, a higher proportion of women (>60%), and participants with a mean age >60 years. Few patients were lost to follow-up; withdrawal rates were low and similar in all 3 studies. Each study compared a letter with usual care; 2 of the 3 had a third arm that included both a letter and a short consultation.

Pooled results from the studies showed twice the reduction in benzodiazepine use in the intervention groups compared with the control groups (risk ratio [RR]=2.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-2.8; P< .001). The RR for cessation of benzodiazepine use was 2.3 (95% CI, 1.3-4.2; P= .003). The number needed to treat for a reduction or cessation of use was 12. The studies reported benzodiazepine reduction rates of 20% to 35% in the intervention groups vs 6% to 15% in the usual care groups.7-9 There appeared to be no additional benefit to adding the brief consultation compared with the letter alone.

WHAT’S NEW?: This strategy is easy to implement

While many methods to reduce benzodiazepine use have been studied, most involved levels of skill and resources that are not feasible for widespread use. This study found that a letter, stating the risks of continued use of the medication and providing a weaning schedule and tips for handling withdrawal, can be effective in reducing chronic use in a small but significant part of the population.

CAVEATS: Effects of withdrawal went unaddressed

The study did not adequately address the adverse effects of withdrawal from benzodiazepines, with one of the studies reporting significantly worse qualitative (but not quantitative) withdrawal symptoms at 6 months.7 This is of particular concern, as withdrawal symptoms are associated with the potential for relapse and concomitant abuse of other drugs and alcohol. We recommend that primary care physicians screen for substance abuse prior to the intervention and arrange for adequate follow-up.

All 3 studies in the meta-analysis lasted 6 months; no longer-term outcomes were reported. In addition, the study did not yield enough information to identify patients who would be most likely to respond to this brief intervention.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Determining which patients to target

Identifying patients who are appropriate candidates for this brief intervention and providing adequate monitoring for adverse effects of withdrawal are the main challenges of this practice changer. Nonetheless, chronic benzodiazepine use is of considerable concern, and we believe that this is a useful, and manageable intervention.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Mugunthan K, McGuire T, Glasziou P. Minimal interventions to decrease long-term use of benzodiazepines in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e573-e578.

2. Tyrer PJ. Benzodiazepines on trial. Br Med J. 1984;288:1101-1102.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: Leading causes for 2008. June 6, 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr60/nvsr60_06.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Topics in brief: Prescription drug abuse. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/topics-in-brief/prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed October 11, 2012.

5. Morin CM, Bastien C, Guay B, et al. Randomized clinical trail of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:332-342.

6. Oude Voshaar RC, Couvee JE, van Balkorn AJ, et al. Strategies for discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine use-meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatr. 2006;189:213-220.

7. Bashir K, King M, Ashworth M. Controlled evaluation of brief intervention by general practitioners to reduce chronic use of benzodiazepines. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:408-412.

8. Cormack MA, Sweeney KG, Hughes-Jones H, et al. Evaluation of an easy, cost-effective strategy to cut benzodiazepine use in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:5-8

9. Heather NA, Bowie A, Ashton H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of two brief interventions against long-term benzodiazepine use: outcome of intervention. Addict Res Theory. 2004;12:141-145.

1. Mugunthan K, McGuire T, Glasziou P. Minimal interventions to decrease long-term use of benzodiazepines in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e573-e578.

2. Tyrer PJ. Benzodiazepines on trial. Br Med J. 1984;288:1101-1102.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths: Leading causes for 2008. June 6, 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr60/nvsr60_06.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2012.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Topics in brief: Prescription drug abuse. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/topics-in-brief/prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed October 11, 2012.

5. Morin CM, Bastien C, Guay B, et al. Randomized clinical trail of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:332-342.

6. Oude Voshaar RC, Couvee JE, van Balkorn AJ, et al. Strategies for discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine use-meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatr. 2006;189:213-220.

7. Bashir K, King M, Ashworth M. Controlled evaluation of brief intervention by general practitioners to reduce chronic use of benzodiazepines. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:408-412.

8. Cormack MA, Sweeney KG, Hughes-Jones H, et al. Evaluation of an easy, cost-effective strategy to cut benzodiazepine use in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:5-8

9. Heather NA, Bowie A, Ashton H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of two brief interventions against long-term benzodiazepine use: outcome of intervention. Addict Res Theory. 2004;12:141-145.

Copyright © 2012 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Let’s put a stop to the prescribing cascade

I am delighted by the commonsense approach Drs. Weiss and Lee have taken in advising us to be wary of prescribing—or continuing—too many medications for our older patients (“Is your patient taking too many pills?”). Frankly, this advice applies to all patients, regardless of their age, and to virtually all family physicians. We all have stories about medication overuse. I’d like to tell you 2 of mine.

When Mrs. S, a 68-year-old patient, came to see me for the first time, I scanned her medication list. It included a nasal steroid for allergic rhinitis, a PPI for reflux, and 2 asthma inhalers—albuterol and an inhaled corticosteroid.

I asked her if she had hay fever. She didn’t think so. Heartburn? She said No. A history of asthma? No. So why was she taking these medications? To treat a chronic cough, the patient said. Was the cough better? No.

In the past 12 months, Mrs. S had seen an allergist, a gastroenterologist, and an otolaryngologist. The result? All 3 specialists added their favorite medication. I scanned the patient’s medication list again and noticed that she was taking amitriptyline 25 mg as a sleep aid. Because of the drug’s anticholinergic adverse effects, I had a hunch, and asked her to go one week without the amitriptyline. She agreed.

You can guess the happy ending. Mrs. S’s cough vanished, along with 4 medications she never needed in the first place. She was a victim of the prescribing cascade.

The other story is even more dramatic.

A friend who’s both an FP and a geriatrician became medical director of a local nursing home. To his chagrin, the average number of prescription drugs per resident when he took over was 9.6. Systematically, he went about reevaluating what residents really required. After a year and a half, the average had fallen to 5.4. The residents were no more depressed or agitated, and were generally more alert.

But here’s the catch: I checked back at the nursing home a couple of years after my friend left, and the average number of meds was back up to 10. It takes constant attention to not overprescribe. In fact, I now spend about as much time stopping meds as starting them.

Our health care system is the land of excess. It is up to family physicians—indeed, to all primary care clinicians—to ensure that we only prescribe or continue prescriptions when it’s the right patient, the right medication, at the right time.

Now it’s your turn. Send me your favorite, or most dramatic, medication overtreatment stories for our Letters column. We’ll continue the dialogue there.

I am delighted by the commonsense approach Drs. Weiss and Lee have taken in advising us to be wary of prescribing—or continuing—too many medications for our older patients (“Is your patient taking too many pills?”). Frankly, this advice applies to all patients, regardless of their age, and to virtually all family physicians. We all have stories about medication overuse. I’d like to tell you 2 of mine.

When Mrs. S, a 68-year-old patient, came to see me for the first time, I scanned her medication list. It included a nasal steroid for allergic rhinitis, a PPI for reflux, and 2 asthma inhalers—albuterol and an inhaled corticosteroid.

I asked her if she had hay fever. She didn’t think so. Heartburn? She said No. A history of asthma? No. So why was she taking these medications? To treat a chronic cough, the patient said. Was the cough better? No.

In the past 12 months, Mrs. S had seen an allergist, a gastroenterologist, and an otolaryngologist. The result? All 3 specialists added their favorite medication. I scanned the patient’s medication list again and noticed that she was taking amitriptyline 25 mg as a sleep aid. Because of the drug’s anticholinergic adverse effects, I had a hunch, and asked her to go one week without the amitriptyline. She agreed.

You can guess the happy ending. Mrs. S’s cough vanished, along with 4 medications she never needed in the first place. She was a victim of the prescribing cascade.

The other story is even more dramatic.

A friend who’s both an FP and a geriatrician became medical director of a local nursing home. To his chagrin, the average number of prescription drugs per resident when he took over was 9.6. Systematically, he went about reevaluating what residents really required. After a year and a half, the average had fallen to 5.4. The residents were no more depressed or agitated, and were generally more alert.

But here’s the catch: I checked back at the nursing home a couple of years after my friend left, and the average number of meds was back up to 10. It takes constant attention to not overprescribe. In fact, I now spend about as much time stopping meds as starting them.

Our health care system is the land of excess. It is up to family physicians—indeed, to all primary care clinicians—to ensure that we only prescribe or continue prescriptions when it’s the right patient, the right medication, at the right time.

Now it’s your turn. Send me your favorite, or most dramatic, medication overtreatment stories for our Letters column. We’ll continue the dialogue there.

I am delighted by the commonsense approach Drs. Weiss and Lee have taken in advising us to be wary of prescribing—or continuing—too many medications for our older patients (“Is your patient taking too many pills?”). Frankly, this advice applies to all patients, regardless of their age, and to virtually all family physicians. We all have stories about medication overuse. I’d like to tell you 2 of mine.

When Mrs. S, a 68-year-old patient, came to see me for the first time, I scanned her medication list. It included a nasal steroid for allergic rhinitis, a PPI for reflux, and 2 asthma inhalers—albuterol and an inhaled corticosteroid.

I asked her if she had hay fever. She didn’t think so. Heartburn? She said No. A history of asthma? No. So why was she taking these medications? To treat a chronic cough, the patient said. Was the cough better? No.

In the past 12 months, Mrs. S had seen an allergist, a gastroenterologist, and an otolaryngologist. The result? All 3 specialists added their favorite medication. I scanned the patient’s medication list again and noticed that she was taking amitriptyline 25 mg as a sleep aid. Because of the drug’s anticholinergic adverse effects, I had a hunch, and asked her to go one week without the amitriptyline. She agreed.

You can guess the happy ending. Mrs. S’s cough vanished, along with 4 medications she never needed in the first place. She was a victim of the prescribing cascade.

The other story is even more dramatic.

A friend who’s both an FP and a geriatrician became medical director of a local nursing home. To his chagrin, the average number of prescription drugs per resident when he took over was 9.6. Systematically, he went about reevaluating what residents really required. After a year and a half, the average had fallen to 5.4. The residents were no more depressed or agitated, and were generally more alert.

But here’s the catch: I checked back at the nursing home a couple of years after my friend left, and the average number of meds was back up to 10. It takes constant attention to not overprescribe. In fact, I now spend about as much time stopping meds as starting them.

Our health care system is the land of excess. It is up to family physicians—indeed, to all primary care clinicians—to ensure that we only prescribe or continue prescriptions when it’s the right patient, the right medication, at the right time.

Now it’s your turn. Send me your favorite, or most dramatic, medication overtreatment stories for our Letters column. We’ll continue the dialogue there.

AGING: Are these 4 pain myths complicating care?

Beliefs about aging itself can also have dramatic consequences, both positive and negative. In one longitudinal study, those who had positive self-perceptions of aging when they were 50 had better health during 2 decades of follow-up and lived, on average, 7½ years longer than those who had negative self-perceptions at the age of 50.4

Although little research has focused specifically on pain-related stereotypes held by older adults, their importance has long been recognized.

Twenty years ago, a review found that the failure to incorporate older patients’ beliefs about pain could have a negative effect on pain management.5 And in 2011, an Institute of Medicine report found a critical need for public education to counter the myths, misunderstandings, stereotypes, and stigma that hinder pain management in patients across the lifespan.6

We set out to identify widely held stereotypes that older adults and physicians have about pain—and to report on primary studies that support or refute them. We focused on noncancer pain. In the pages that follow, we identify 4 key stereotypes that misrepresent the experience of older adults with regard to pain, and present evidence to debunk them.

Stereotype #1: Pain is a natural part of getting older

Chronic pain is often perceived as an age-related condition. In in-depth interviews, older adults with osteoarthritis reported pain as a normal, even essential, part of life. As one patient put it, “That’s how you know you’re alive … you ache.”7

Among primary care patients with osteoarthritis, those older than 70 years were more likely than younger patients to believe that people should expect to live with pain as they get older.8 And more than half of older adults who responded to a community-based survey considered arthritis to be a natural part of getting old.9

Physicians, too, often view pain as an inevitable part of the aging process, giving patients feedback such as “What do you expect? You’re just getting older.”10

Are they right?

Is pain inevitable? No

In fact, chronic pain is common in older adults, occurring in more than half of those assessed, according to some studies.11 In addition, some epidemiological studies have found an age-related increase in the prevalence of pain,12-14 with older age predicting a more likely onset of, and failure to recover from, persistent pain.15 But numerous studies have failed to find a direct relationship between pain and age.

A National Center for Health Statistics report found that 29% of adults between the ages of 45 and 64 years vs 21% of those 65 or older reported pain lasting >24 hours in the month before the survey.16 And a meta-analysis comparing age-related differences in pain perception found that the highest prevalence of chronic pain occurred at about age 65; a slight decline with advancing age followed, even beyond the age of 85.17

Chronic pain disorders are less frequent. In fact, many chronic pain disorders occur less frequently with advancing age. Population-based studies have found a lower prevalence of low back, neck, and face pain among older adults compared with their younger counterparts;16 evidence has also found lower rates of headache and abdominal pain.18 Other epidemiological studies suggest that the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain generally declines with advancing age,19 and a study of patients in their last 2 years of life found pain to be inversely correlated with age.20 These findings refute the stereotype that advancing age inexorably involves pain, and challenge the notion that pain in later life is normal and expected, and unworthy of treatment.

Stereotype #2: Pain worsens

over time

Some patients and physicians expect that as people age, their pain will increase in intensity. In one study of community-dwelling older adults, 87% of those surveyed rated the belief that more aches and pains are an accepted part of aging as definitely or somewhat true.21 Indeed, patients of all ages have expressed the belief that older age confers greater susceptibility to, and suffering from, painful conditions like arthritis.22 Many common causes of pain in older adults, especially osteoarthritis, are seen as resulting from degenerative changes, which worsen over time.23

Does pain intensify? Not necessarily

Some studies have linked older age to a worse prognosis for patients with musculoskeletal pain, but a greater number have found that aging has no effect on it.24

Pain does not always progress. In a large cohort of patients with peripheral joint osteoarthritis, radiographic joint space narrowing worsened over 3 years, but this did not correlate consistently with worsening pain.25 When the same cohort was assessed after 8 years, there was significant variability in pain, with no clear progression.26

In another study involving older patients with restrictive back pain, the pain was frequently short-lived and episodic and did not increase with age.27 And in a population sample in Norway, the mean number of pain sites decreased slightly over 14 years in those older than 60 years, while increasing in those aged 44 to 60.28 Another study of patients with knee osteoarthritis identified factors that were protective against a decline in pain-related function: These included good mental health, self-efficacy, social support, and greater activity—but not younger age.29 The enormous heterogeneity in both the experience and the course of pain suggests that age-related pain progression is neither universal nor expected—and contradicts a purely biological paradigm in which pain inevitably worsens over time.

Stereotype #3: Stoicism leads to pain tolerance

Some patients believe that the inability to deal with pain is a sign of being soft or weak, and that a “tough it out” approach makes pain easier to tolerate.7 In one survey, older adults were more likely than their younger counterparts to express such stoicism, frequently agreeing with statements like, “I maintain my pride and keep a stiff upper lip when in pain,” “I go on as if nothing had happened …,” and “Pain is something that should be ignored.” 30

Unfortunately, some physicians reinforce such attitudes, telling older patients, in effect, that they’d better “get used to it.”10 And family and friends may make it worse. Patients taking opioids reported that it wasn’t unusual for those close to them to view their use of these analgesics as a sign of weakness.31

Does stoicism help? Probably not

Older adults seem less likely than younger adults to label a sensation as painful, suggesting a more stoic approach in general.30 While some research has found that nociception—the perception of pain in response to painful stimuli—decreases with advancing age,32 other studies have found the opposite.33 And population-based studies focusing on the consequences of pain indicate that it continues to have powerful negative effects, especially depression and insomnia, in older patients.

The degree of pain experienced is more strongly associated with depression in older patients compared with younger adults,34 and greater pain reduces the likelihood that depression will improve with treatment.35 Pain also continues to interfere with sleep. In one national sample, 25% of those with arthritis said they suffered from insomnia, roughly twice the prevalence of insomnia found in those without arthritis.36 In another study, individuals with arthritis were 3 times more likely to have sleep problems compared with individuals without arthritis37—an association independent of age. Being stoic about pain, it appears, does not diminish its consequences over time or help patients better tolerate it.

Stereotype #4: Prescription analgesics are highly addictive

Patients often think that prescription analgesics, especially opioids, are highly addictive or harmful—and older adults may refuse to take them for fear of becoming addicted.7 The stereotype is often shared by family and friends, as well as clinicians.

In one study, one-third of physicians said they hesitated to prescribe opioid medications to older adults because of the risk of addiction (a concern that no clinician with training in geriatrics shared).38 What’s more, 16% of the physicians estimated that about one in 4 older patients receiving chronic opioid therapy becomes addicted. The actual risk is far lower. (More on that below.) News reports of an epidemic of prescription opioid addictions and fatalities,39 including the assertion that opioids are replacing heroin as the primary drug of choice on the street,40 may reinforce such stereotypes.

How great is the risk of addiction? For older adults, it’s very low

While rates of aberrant opioid use vary widely depending on the context, one consistent theme is that older age is associated with decreased risk.41 In one retrospective cohort study of older patients who had recently been started on an opioid medication for the treatment of chronic pain, only 3% showed evidence of behaviors associated with abuse or misuse.42

What’s more, long-term opioid use among older patients with painful conditions is relatively uncommon, and prescription patterns suggest that most older adults discontinue opioids after one or 2 prescriptions.42-44 Decades of research have found that, although opioid medications can cause physiological dependence, addiction is rare in patients treated with them.45,46 (To learn more, see “Diagnosing and treating opioid dependence,” J Fam Pract. 2012;61: 588-597.)

Debunking myths: Implications for practice

Our findings—that pain is not a natural part of aging and often improves or remains stable over time, stoicism does not lead to acclimation, and pain medications are not highly addictive in older adults—make it clear that the stereotypes we identified are misconceptions of pain in later life. Debunking these stereotypes has several implications for clinical practice. We recommend the following:

Identify and counter these stereotypes. Avoid reinforcing stereotypes; counter them by summarizing these evidence-based findings for older patients. We believe patients would be receptive.

In one study, more than 80% of patients with osteoarthritis said they wanted prognostic information about the course of the disease, but only about one-third had received it.47 Presenting the research findings would challenge patients’ stereotypes and help them reframe their expectations.

Elicit patients’ perspectives. Ask patients about age- and pain-related stereotypes and their expectations and perspectives of what constitutes successful treatment. Research shows that patients often wish to discuss lifestyle changes and nonmedical approaches to pain, for example, but that clinicians typically focus on medications instead.48

Emphasize the positive. Frame discussions of pain and aging in a positive light, offering encouragement rather than supporting stoicism or resignation. Attention to protective factors, including good mental health, self-efficacy, social support, and greater activity, may enable older patients to adapt better to any pain they experience.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen Thielke, MD, MSPH, MA, University of Washington, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Box 356560, Seattle, WA 98195; [email protected]

1. Herr K. Pain in the older adult: an imperative across all health care settings. Pain Manag Nurs. 2010;11(2 suppl):S1-S10.

2. Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Management of nonmalignant pain in home-dwelling older people: a population-based survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1861-1865.

3. Levy B. Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:332-336.

4. Levy BR, Slade MD, Kasl SV. Longitudinal benefit of positive self-perceptions of aging on functional health. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:409-417.

5. Hofland SL. Elder beliefs: blocks to pain management. J Gerontol Nurs. 1992;18:19-23.

6. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

7. Sale J, Gignac M, Hawker G. How “bad” does the pain have to be? A qualitative study examining adherence to pain medication in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:272-278.

8. Appelt CJ, Burant BC, Siminoff LA, et al. Health beliefs related to aging among older male patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:184-190.

9. Goodwin JS, Black SA, Satish S. Aging versus disease: the opinions of older black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white Americans about the causes and treatment of common medical conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:973-979.

10. Gignac M, Davis A, Hawker G, et al. “What do you expect? You’re just getting older”: a comparison of perceived osteoarthritis-related and aging-related health experiences in middle- and older-age adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:905-912.

11. Helme RD, Gibson SJ. Pain in the elderly. In: Jensen TS, Turner JA, Weisenfeld-Hallin Z, eds. Progress in Pain Research and Management. Proceedings of the 8th World Congress on Pain. Vol 8. Seattle, Wash: IASP Press; 1997:919–944.

12. Badley EM, Tennant A. Changing profile of joint disorders with age: findings from a postal survey of the population of Calderdale, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom. Ann Rheumatic Dis. 1992;51:366-371.

13. Brattberg G, Parker MG, Thorslund M. A longitudinal study of pain: reported pain from middle age to old age. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:144-149.

14. Crook J, Rideout E, Browne G. The prevalence of pain complaints in a general population. Pain. 1984;18:299-314.

15. Gureje O, Simon GE, Von Korff M. A cross-national study of the course of persistent pain in primary care. Pain. 2001;92:195-200.

16. National Center for Health Statistics. Special feature: pain. In: Health, United States, 2006 with Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, Md: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006:68–87. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus06.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2012.

17. Gibson SJ, Helme RD. Age differences in pain perception and report: a review of physiological, psychological, laboratory and clinical studies. Pain Rev. 1995;2:111-137.

18. Gallagher RM, Verma S, Mossey J. Chronic pain. Sources of late-life pain and risk factors for disability. Geriatrics. 2000;55:40-44, 47.

19. Picavet HS, Schouten JS. Musculoskeletal pain in the Netherlands: prevalences, consequences and risk groups, the DMC(3)-study. Pain. 2003;102:167-178.

20. Smith AK, Cenzer IS, Knight SJ, et al. The epidemiology of pain during the last 2 years of life. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:563-569.

21. Sarkisian CA, Hays RD, Mangione CM. Do older adults expect to age successfully? The association between expectations regarding aging and beliefs regarding healthcare seeking among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1837-1843.

22. Keller ML, Leventhal H, Prohaska TR, et al. Beliefs about aging and illness in a community sample. Res Nurs Health. 1989;12:247-255.

23. Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nguyen M, et al. Longitudinal radiologic evaluation of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatology. 1992;19:378-384.

24. Mallen CD, Peat G, Thomas E, et al. Prognostic factors for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:655-661.

25. Dieppe PA, Cushnaghan J, Shepstone L. The Bristol ‘OA500’ study: progression of osteoarthritis (OA) over 3 years and the relationship between clinical and radiographic changes at the knee joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1997;5:87-97.

26. Dieppe P, Cushnaghan J, Tucker M, et al. The Bristol ‘OA500 study’: progression and impact of the disease after 8 years. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:63-68.

27. Makris UE, Fraenkel L, Han L, et al. Epidemiology of restricting back pain in community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:610-614.

28. Kamaleri Y, Natvig B, Ihlebaek CM, et al. Change in the number of musculoskeletal pain sites: a 14-year prospective study. Pain. 2009;141:25-30.

29. Sharma L, Cahue S, Song J, et al. Physical functioning over three years in knee osteoarthritis: role of psychosocial, local mechanical, and neuromuscular factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3359-3370.

30. Yong HH, Gibson SJ, Horne DJ, et al. Development of a pin attitudes questionnaire to assess stoicism and cautiousness for possible age differences. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56:279-284.

31. Vallerand A, Nowak L. Chronic opioid therapy for nonmalignant pain: the patient’s perspective. Part II—barriers to chronic opioid therapy. Pain manag nurs. 2010;11:126-131.

32. Gibson SJ, Farrell M. A review of age differences in the neurophysiology of nociception and the perceptual experience of pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:227-239.

33. Woodrow KM, Friedman GD, Siegelaub AB, et al. Pain tolerance: differences according to age, sex and race. Psychosom Med. 1972;34:548-556.

34. Turk DC, Okifuji A, Scharff L. Chronic pain and depression: role of perceived impact and perceived control in different age cohorts. Pain. 1995;61:93-101.

35. Thielke SM, Fan MY, Sullivan M, et al. Pain limits the effectiveness of collaborative care for depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:699-707.

36. Power JD, Perruccio AV, Badley EM. Pain as a mediator of sleep problems in arthritis and other chronic conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:911-919.

37. Louie GH, Tektonidou MG, Caban-Martizen AJ, et al. Sleep disturbances in adults with arthritis: prevalence, mediators, and subgroups at greatest risk. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:247-260.

38. Lin JJ, Alfandre D, Moore C. Physician attitudes toward opioid prescribing for patients with persistent noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:799-803.

39. Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300:2613-2620.

40. Fischer B, Gittins J, Kendall P, et al. Thinking the unthinkable: could the increasing misuse of prescription opioids among street drug users offer benefits for public health? Public Health. 2009;123:145-146.

41. Fleming MF, Davis J, Passik SD. Reported lifetime aberrant drug-taking behaviors are predictive of current substance use and mental health problems in primary care patients. Pain Med. 2008;9:1098-1106.

42. Reid MC, Henderson CR, Jr, Papaleontiou M, et al. Characteristics of older adults receiving opioids in primary care: treatment duration and outcomes. Pain Med. 2010;11:1063-1071.

43. Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. The comparative safety of opioids for nonmalignant pain in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1979-1986.

44. Thielke SM, Simoni-Wastila L, Edlund MJ, et al. Age and sex trends in long-term opioid use in two large American health systems between 2000 and 2005. Pain Med. 2010;11:248-256.

45. Soden K, Ali S, Alloway L, et al. How do nurses assess and manage breakthrough pain in specialist palliative care inpatient units? A multicentre study. Palliat Med. 2010;24:294-298.

46. Papaleontiou M, Henderson CR, Jr, Turner BJ, et al. Outcomes associated with opioid use in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1353-1369.

47. Mallen CD, Peat G. Discussing prognosis with older people with musculoskeletal pain: a cross-sectional study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:50.-

48. Rosemann T, Wensing M, Joest K, et al. Problems and needs for improving primary care of osteoarthritis patients: the views of patients, general practitioners and practice nurses. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:48.

Beliefs about aging itself can also have dramatic consequences, both positive and negative. In one longitudinal study, those who had positive self-perceptions of aging when they were 50 had better health during 2 decades of follow-up and lived, on average, 7½ years longer than those who had negative self-perceptions at the age of 50.4

Although little research has focused specifically on pain-related stereotypes held by older adults, their importance has long been recognized.

Twenty years ago, a review found that the failure to incorporate older patients’ beliefs about pain could have a negative effect on pain management.5 And in 2011, an Institute of Medicine report found a critical need for public education to counter the myths, misunderstandings, stereotypes, and stigma that hinder pain management in patients across the lifespan.6

We set out to identify widely held stereotypes that older adults and physicians have about pain—and to report on primary studies that support or refute them. We focused on noncancer pain. In the pages that follow, we identify 4 key stereotypes that misrepresent the experience of older adults with regard to pain, and present evidence to debunk them.

Stereotype #1: Pain is a natural part of getting older

Chronic pain is often perceived as an age-related condition. In in-depth interviews, older adults with osteoarthritis reported pain as a normal, even essential, part of life. As one patient put it, “That’s how you know you’re alive … you ache.”7

Among primary care patients with osteoarthritis, those older than 70 years were more likely than younger patients to believe that people should expect to live with pain as they get older.8 And more than half of older adults who responded to a community-based survey considered arthritis to be a natural part of getting old.9

Physicians, too, often view pain as an inevitable part of the aging process, giving patients feedback such as “What do you expect? You’re just getting older.”10

Are they right?

Is pain inevitable? No

In fact, chronic pain is common in older adults, occurring in more than half of those assessed, according to some studies.11 In addition, some epidemiological studies have found an age-related increase in the prevalence of pain,12-14 with older age predicting a more likely onset of, and failure to recover from, persistent pain.15 But numerous studies have failed to find a direct relationship between pain and age.

A National Center for Health Statistics report found that 29% of adults between the ages of 45 and 64 years vs 21% of those 65 or older reported pain lasting >24 hours in the month before the survey.16 And a meta-analysis comparing age-related differences in pain perception found that the highest prevalence of chronic pain occurred at about age 65; a slight decline with advancing age followed, even beyond the age of 85.17

Chronic pain disorders are less frequent. In fact, many chronic pain disorders occur less frequently with advancing age. Population-based studies have found a lower prevalence of low back, neck, and face pain among older adults compared with their younger counterparts;16 evidence has also found lower rates of headache and abdominal pain.18 Other epidemiological studies suggest that the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain generally declines with advancing age,19 and a study of patients in their last 2 years of life found pain to be inversely correlated with age.20 These findings refute the stereotype that advancing age inexorably involves pain, and challenge the notion that pain in later life is normal and expected, and unworthy of treatment.

Stereotype #2: Pain worsens

over time

Some patients and physicians expect that as people age, their pain will increase in intensity. In one study of community-dwelling older adults, 87% of those surveyed rated the belief that more aches and pains are an accepted part of aging as definitely or somewhat true.21 Indeed, patients of all ages have expressed the belief that older age confers greater susceptibility to, and suffering from, painful conditions like arthritis.22 Many common causes of pain in older adults, especially osteoarthritis, are seen as resulting from degenerative changes, which worsen over time.23

Does pain intensify? Not necessarily

Some studies have linked older age to a worse prognosis for patients with musculoskeletal pain, but a greater number have found that aging has no effect on it.24

Pain does not always progress. In a large cohort of patients with peripheral joint osteoarthritis, radiographic joint space narrowing worsened over 3 years, but this did not correlate consistently with worsening pain.25 When the same cohort was assessed after 8 years, there was significant variability in pain, with no clear progression.26

In another study involving older patients with restrictive back pain, the pain was frequently short-lived and episodic and did not increase with age.27 And in a population sample in Norway, the mean number of pain sites decreased slightly over 14 years in those older than 60 years, while increasing in those aged 44 to 60.28 Another study of patients with knee osteoarthritis identified factors that were protective against a decline in pain-related function: These included good mental health, self-efficacy, social support, and greater activity—but not younger age.29 The enormous heterogeneity in both the experience and the course of pain suggests that age-related pain progression is neither universal nor expected—and contradicts a purely biological paradigm in which pain inevitably worsens over time.

Stereotype #3: Stoicism leads to pain tolerance

Some patients believe that the inability to deal with pain is a sign of being soft or weak, and that a “tough it out” approach makes pain easier to tolerate.7 In one survey, older adults were more likely than their younger counterparts to express such stoicism, frequently agreeing with statements like, “I maintain my pride and keep a stiff upper lip when in pain,” “I go on as if nothing had happened …,” and “Pain is something that should be ignored.” 30

Unfortunately, some physicians reinforce such attitudes, telling older patients, in effect, that they’d better “get used to it.”10 And family and friends may make it worse. Patients taking opioids reported that it wasn’t unusual for those close to them to view their use of these analgesics as a sign of weakness.31

Does stoicism help? Probably not

Older adults seem less likely than younger adults to label a sensation as painful, suggesting a more stoic approach in general.30 While some research has found that nociception—the perception of pain in response to painful stimuli—decreases with advancing age,32 other studies have found the opposite.33 And population-based studies focusing on the consequences of pain indicate that it continues to have powerful negative effects, especially depression and insomnia, in older patients.

The degree of pain experienced is more strongly associated with depression in older patients compared with younger adults,34 and greater pain reduces the likelihood that depression will improve with treatment.35 Pain also continues to interfere with sleep. In one national sample, 25% of those with arthritis said they suffered from insomnia, roughly twice the prevalence of insomnia found in those without arthritis.36 In another study, individuals with arthritis were 3 times more likely to have sleep problems compared with individuals without arthritis37—an association independent of age. Being stoic about pain, it appears, does not diminish its consequences over time or help patients better tolerate it.

Stereotype #4: Prescription analgesics are highly addictive

Patients often think that prescription analgesics, especially opioids, are highly addictive or harmful—and older adults may refuse to take them for fear of becoming addicted.7 The stereotype is often shared by family and friends, as well as clinicians.

In one study, one-third of physicians said they hesitated to prescribe opioid medications to older adults because of the risk of addiction (a concern that no clinician with training in geriatrics shared).38 What’s more, 16% of the physicians estimated that about one in 4 older patients receiving chronic opioid therapy becomes addicted. The actual risk is far lower. (More on that below.) News reports of an epidemic of prescription opioid addictions and fatalities,39 including the assertion that opioids are replacing heroin as the primary drug of choice on the street,40 may reinforce such stereotypes.

How great is the risk of addiction? For older adults, it’s very low