User login

Win Whitcomb: Mortality Rates Become a Measuring Stick for Hospital Performance

—Blue Oyster Cult

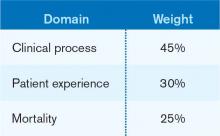

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

—Blue Oyster Cult

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

—Blue Oyster Cult

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Multidisciplinary Palliative-Care Consults Help Reduce Hospital Readmissions

Research on seriously ill, hospitalized, Medicare-age patients finds that those who received inpatient consultations from a multidisciplinary, palliative-care team (including a physician, nurse, and social worker) had lower 30-day hospital readmission rates.1 Ten percent of discharged patients who received the palliative-care consult were readmitted within 30 days at an urban HMO medical center in Los Angeles County during the same period, even though they were sicker than the overall discharged population.

Receipt of hospice care or home-based palliative-care services following discharge was also associated with significantly lower rates of readmissions, suggesting opportunities for systemic cost savings from earlier access to longitudinal, or ongoing, palliative-care services, says Susan Enguidanos, MPH, PhD, assistant professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Patients discharged from the hospital without any follow-up care in the home had higher odds of readmission.

“Hospitals and medical centers should seriously consider an inpatient palliative care consultation team for many reasons, mostly arising from findings from other studies that have demonstrated improved quality of life, pain and symptom management, satisfaction with medical care, and other promising outcomes,” Dr. Enguidanos says. “Our study suggests that longitudinal palliative care is also associated with the lower readmission rate.”

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Research on seriously ill, hospitalized, Medicare-age patients finds that those who received inpatient consultations from a multidisciplinary, palliative-care team (including a physician, nurse, and social worker) had lower 30-day hospital readmission rates.1 Ten percent of discharged patients who received the palliative-care consult were readmitted within 30 days at an urban HMO medical center in Los Angeles County during the same period, even though they were sicker than the overall discharged population.

Receipt of hospice care or home-based palliative-care services following discharge was also associated with significantly lower rates of readmissions, suggesting opportunities for systemic cost savings from earlier access to longitudinal, or ongoing, palliative-care services, says Susan Enguidanos, MPH, PhD, assistant professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Patients discharged from the hospital without any follow-up care in the home had higher odds of readmission.

“Hospitals and medical centers should seriously consider an inpatient palliative care consultation team for many reasons, mostly arising from findings from other studies that have demonstrated improved quality of life, pain and symptom management, satisfaction with medical care, and other promising outcomes,” Dr. Enguidanos says. “Our study suggests that longitudinal palliative care is also associated with the lower readmission rate.”

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Research on seriously ill, hospitalized, Medicare-age patients finds that those who received inpatient consultations from a multidisciplinary, palliative-care team (including a physician, nurse, and social worker) had lower 30-day hospital readmission rates.1 Ten percent of discharged patients who received the palliative-care consult were readmitted within 30 days at an urban HMO medical center in Los Angeles County during the same period, even though they were sicker than the overall discharged population.

Receipt of hospice care or home-based palliative-care services following discharge was also associated with significantly lower rates of readmissions, suggesting opportunities for systemic cost savings from earlier access to longitudinal, or ongoing, palliative-care services, says Susan Enguidanos, MPH, PhD, assistant professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Patients discharged from the hospital without any follow-up care in the home had higher odds of readmission.

“Hospitals and medical centers should seriously consider an inpatient palliative care consultation team for many reasons, mostly arising from findings from other studies that have demonstrated improved quality of life, pain and symptom management, satisfaction with medical care, and other promising outcomes,” Dr. Enguidanos says. “Our study suggests that longitudinal palliative care is also associated with the lower readmission rate.”

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Cardiologists Help Lower Readmission Rates for Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients

Data reported at the American Heart Association’s scientific sessions in Los Angeles in November suggest that when a cardiologist, rather than a hospitalist, is the attending physician for a hospitalized heart failure patient, readmission is less likely. Casey M. Lawler, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, says her center began establishing protocols to improve heart failure readmissions rates five years ago, after determining that many patients did not understand their diagnosis or treatment. “Thus, we became much more involved in post-discharge care,” including the phoning of discharged patients and follow-up with primary-care providers.

When the heart failure patients’ attending physicians were cardiologists, their readmission rate was 16%, versus 27.1% with hospitalists, even though their severity of illness was higher. Length of stay was similar for both groups and total mean costs were higher for the patients managed by cardiologists. “Although these results reveal that specialists have a positive impact on readmission rates, an overhaul to an entire healthcare system’s treatment of [heart failure] patients—from admission to post-discharge follow-up—is required to truly impact preventable readmissions,” Dr. Lawler asserted.

In the Minneapolis study, 65% of the 2,300 heart failure patients were managed by hospitalists, and 35% by cardiologists. A recent national survey of advanced heart failure programs found that cardiologists managed the care of acute HF patients more than 60 percent of the time.2

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Data reported at the American Heart Association’s scientific sessions in Los Angeles in November suggest that when a cardiologist, rather than a hospitalist, is the attending physician for a hospitalized heart failure patient, readmission is less likely. Casey M. Lawler, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, says her center began establishing protocols to improve heart failure readmissions rates five years ago, after determining that many patients did not understand their diagnosis or treatment. “Thus, we became much more involved in post-discharge care,” including the phoning of discharged patients and follow-up with primary-care providers.

When the heart failure patients’ attending physicians were cardiologists, their readmission rate was 16%, versus 27.1% with hospitalists, even though their severity of illness was higher. Length of stay was similar for both groups and total mean costs were higher for the patients managed by cardiologists. “Although these results reveal that specialists have a positive impact on readmission rates, an overhaul to an entire healthcare system’s treatment of [heart failure] patients—from admission to post-discharge follow-up—is required to truly impact preventable readmissions,” Dr. Lawler asserted.

In the Minneapolis study, 65% of the 2,300 heart failure patients were managed by hospitalists, and 35% by cardiologists. A recent national survey of advanced heart failure programs found that cardiologists managed the care of acute HF patients more than 60 percent of the time.2

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Data reported at the American Heart Association’s scientific sessions in Los Angeles in November suggest that when a cardiologist, rather than a hospitalist, is the attending physician for a hospitalized heart failure patient, readmission is less likely. Casey M. Lawler, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, says her center began establishing protocols to improve heart failure readmissions rates five years ago, after determining that many patients did not understand their diagnosis or treatment. “Thus, we became much more involved in post-discharge care,” including the phoning of discharged patients and follow-up with primary-care providers.

When the heart failure patients’ attending physicians were cardiologists, their readmission rate was 16%, versus 27.1% with hospitalists, even though their severity of illness was higher. Length of stay was similar for both groups and total mean costs were higher for the patients managed by cardiologists. “Although these results reveal that specialists have a positive impact on readmission rates, an overhaul to an entire healthcare system’s treatment of [heart failure] patients—from admission to post-discharge follow-up—is required to truly impact preventable readmissions,” Dr. Lawler asserted.

In the Minneapolis study, 65% of the 2,300 heart failure patients were managed by hospitalists, and 35% by cardiologists. A recent national survey of advanced heart failure programs found that cardiologists managed the care of acute HF patients more than 60 percent of the time.2

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

VTE Pathway Improves Outcomes for Uninsured Patients

A poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April describes a standardized, systematic, multidisciplinary clinical pathway for treating acute VTE (venous thromboembolism) in an urban hospital serving a high proportion of the uninsured.3 Implementing the pathway in February 2011 “dramatically reduced hospital utilization and cost, particularly among uninsured patients,” who were previously shown to have increased length of stay, cost, and emergency department recidivism, says lead author Gregory Misky, MD, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

The pathway—which aimed to standardize all VTE care from hospital presentation to post-discharge follow-up—contained multiple components, including education for staff, enhanced communication processes, written order sets, and a series of formal and informal meetings held with community providers, such as the clinics where these patients get their follow-up primary care. Dr. Misky collaborated with his university’s anticoagulation clinic to help identify primary-care physicians and clinics and arrange follow-up outpatient appointments much sooner than the patients could have obtained by themselves.

The prospective study compared 135 VTE patients presenting to the emergency department or admitted to a medicine service and receiving care under the pathway, compared with 234 VTE patients prior to its introduction. Length of stay dropped to 2.5 days from 4.2, and for uninsured patients it dropped even more, to 2.2 days from 5.5.

Dr. Misky says the data gathered since the San Diego conference “continue to show good results in resource utilization, particularly for the uninsured, with emergency department visits and readmissions slashed.” Readmissions have dropped to 5.2% from 9.8%—and to 3.5% from 11.6% for uninsured VTE patients. He suggests that the clinical pathway approach likely has implications for other diseases as well.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

A poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April describes a standardized, systematic, multidisciplinary clinical pathway for treating acute VTE (venous thromboembolism) in an urban hospital serving a high proportion of the uninsured.3 Implementing the pathway in February 2011 “dramatically reduced hospital utilization and cost, particularly among uninsured patients,” who were previously shown to have increased length of stay, cost, and emergency department recidivism, says lead author Gregory Misky, MD, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

The pathway—which aimed to standardize all VTE care from hospital presentation to post-discharge follow-up—contained multiple components, including education for staff, enhanced communication processes, written order sets, and a series of formal and informal meetings held with community providers, such as the clinics where these patients get their follow-up primary care. Dr. Misky collaborated with his university’s anticoagulation clinic to help identify primary-care physicians and clinics and arrange follow-up outpatient appointments much sooner than the patients could have obtained by themselves.

The prospective study compared 135 VTE patients presenting to the emergency department or admitted to a medicine service and receiving care under the pathway, compared with 234 VTE patients prior to its introduction. Length of stay dropped to 2.5 days from 4.2, and for uninsured patients it dropped even more, to 2.2 days from 5.5.

Dr. Misky says the data gathered since the San Diego conference “continue to show good results in resource utilization, particularly for the uninsured, with emergency department visits and readmissions slashed.” Readmissions have dropped to 5.2% from 9.8%—and to 3.5% from 11.6% for uninsured VTE patients. He suggests that the clinical pathway approach likely has implications for other diseases as well.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

A poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April describes a standardized, systematic, multidisciplinary clinical pathway for treating acute VTE (venous thromboembolism) in an urban hospital serving a high proportion of the uninsured.3 Implementing the pathway in February 2011 “dramatically reduced hospital utilization and cost, particularly among uninsured patients,” who were previously shown to have increased length of stay, cost, and emergency department recidivism, says lead author Gregory Misky, MD, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

The pathway—which aimed to standardize all VTE care from hospital presentation to post-discharge follow-up—contained multiple components, including education for staff, enhanced communication processes, written order sets, and a series of formal and informal meetings held with community providers, such as the clinics where these patients get their follow-up primary care. Dr. Misky collaborated with his university’s anticoagulation clinic to help identify primary-care physicians and clinics and arrange follow-up outpatient appointments much sooner than the patients could have obtained by themselves.

The prospective study compared 135 VTE patients presenting to the emergency department or admitted to a medicine service and receiving care under the pathway, compared with 234 VTE patients prior to its introduction. Length of stay dropped to 2.5 days from 4.2, and for uninsured patients it dropped even more, to 2.2 days from 5.5.

Dr. Misky says the data gathered since the San Diego conference “continue to show good results in resource utilization, particularly for the uninsured, with emergency department visits and readmissions slashed.” Readmissions have dropped to 5.2% from 9.8%—and to 3.5% from 11.6% for uninsured VTE patients. He suggests that the clinical pathway approach likely has implications for other diseases as well.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Well-Designed IT Systems Essential to Healthcare Integration

David Lawrence, MD, retired head of the Kaiser Foundation health plan, says in a recent Information Week article that it will be “nearly impossible” to achieve the goals of healthcare integration without the connectivity of a well-designed health IT system.4 Dr. Lawrence was a member of a committee that authored the recent report Order from Chaos: Accelerating Care Integration for the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Care Safety Foundation. Failures of coordination most often happen during the crucial information transfers that happen during care transitions, but there has not been enough attention to how important information technology could be to these transfers, Dr. Lawrence told the magazine. “It’s the really complex stuff where this becomes particularly critical,” he said.

The federal Office of Inspector General (OIG) took the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to task in a November report for not having adequate oversight or safeguards for its EHR meaningful-use program.5 As a result, OIG described Medicare as “vulnerable” to fraud and abuse of incentive payments made to hospitals and health professionals, according to OIG. OIG recommends that CMS request and review supporting documentation for selected providers and issue guidance with specific examples of appropriate documentation. As of September 2012, CMS had paid out $4 billion in meaningful-use incentives to 1,400 hospitals and 82,000 professionals.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

David Lawrence, MD, retired head of the Kaiser Foundation health plan, says in a recent Information Week article that it will be “nearly impossible” to achieve the goals of healthcare integration without the connectivity of a well-designed health IT system.4 Dr. Lawrence was a member of a committee that authored the recent report Order from Chaos: Accelerating Care Integration for the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Care Safety Foundation. Failures of coordination most often happen during the crucial information transfers that happen during care transitions, but there has not been enough attention to how important information technology could be to these transfers, Dr. Lawrence told the magazine. “It’s the really complex stuff where this becomes particularly critical,” he said.

The federal Office of Inspector General (OIG) took the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to task in a November report for not having adequate oversight or safeguards for its EHR meaningful-use program.5 As a result, OIG described Medicare as “vulnerable” to fraud and abuse of incentive payments made to hospitals and health professionals, according to OIG. OIG recommends that CMS request and review supporting documentation for selected providers and issue guidance with specific examples of appropriate documentation. As of September 2012, CMS had paid out $4 billion in meaningful-use incentives to 1,400 hospitals and 82,000 professionals.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

David Lawrence, MD, retired head of the Kaiser Foundation health plan, says in a recent Information Week article that it will be “nearly impossible” to achieve the goals of healthcare integration without the connectivity of a well-designed health IT system.4 Dr. Lawrence was a member of a committee that authored the recent report Order from Chaos: Accelerating Care Integration for the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Care Safety Foundation. Failures of coordination most often happen during the crucial information transfers that happen during care transitions, but there has not been enough attention to how important information technology could be to these transfers, Dr. Lawrence told the magazine. “It’s the really complex stuff where this becomes particularly critical,” he said.

The federal Office of Inspector General (OIG) took the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to task in a November report for not having adequate oversight or safeguards for its EHR meaningful-use program.5 As a result, OIG described Medicare as “vulnerable” to fraud and abuse of incentive payments made to hospitals and health professionals, according to OIG. OIG recommends that CMS request and review supporting documentation for selected providers and issue guidance with specific examples of appropriate documentation. As of September 2012, CMS had paid out $4 billion in meaningful-use incentives to 1,400 hospitals and 82,000 professionals.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Hospitals Adopt Better Nutritional Standards for Meals

Number of meals served annually to patients, visitors, and staff by 155 leading U.S. hospitals, which are adopting new standards and criteria for nutritional care at their facilities in order to promote healthier meal options for patients and in their cafeterias. These hospitals belong to the Healthier Hospitals initiative.

(healthierhospitals.org/) led by the Partnership for a Healthier America, a group working to end childhood obesity. Among its goals are to increase the proportion of fruits and vegetables in hospitals’ food purchasing, to remove deep fat-fried products by the end of 2015, and to take advantage of the buying power and community influence hospitals can leverage to increase demand for healthier food.

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Number of meals served annually to patients, visitors, and staff by 155 leading U.S. hospitals, which are adopting new standards and criteria for nutritional care at their facilities in order to promote healthier meal options for patients and in their cafeterias. These hospitals belong to the Healthier Hospitals initiative.

(healthierhospitals.org/) led by the Partnership for a Healthier America, a group working to end childhood obesity. Among its goals are to increase the proportion of fruits and vegetables in hospitals’ food purchasing, to remove deep fat-fried products by the end of 2015, and to take advantage of the buying power and community influence hospitals can leverage to increase demand for healthier food.

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Number of meals served annually to patients, visitors, and staff by 155 leading U.S. hospitals, which are adopting new standards and criteria for nutritional care at their facilities in order to promote healthier meal options for patients and in their cafeterias. These hospitals belong to the Healthier Hospitals initiative.

(healthierhospitals.org/) led by the Partnership for a Healthier America, a group working to end childhood obesity. Among its goals are to increase the proportion of fruits and vegetables in hospitals’ food purchasing, to remove deep fat-fried products by the end of 2015, and to take advantage of the buying power and community influence hospitals can leverage to increase demand for healthier food.

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: How to take the fear out of expanding a hospitalist group

Click here to listen to Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of Inova Fairfax Hospital Group in Fairfax, Va.

Click here to listen to Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of Inova Fairfax Hospital Group in Fairfax, Va.

Click here to listen to Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of Inova Fairfax Hospital Group in Fairfax, Va.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: American Pain Society Board Member Discusses Opioid Risks, Rewards, and Why Continuing Education is a Must

Click here to listen to Scott Strassels, PhD, PharmD, BCPS, an assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin and a board member of the American Pain Society, discuss the risks and rewards of opioid therapies, and why continuing education is important for all clinicians.

Click here to listen to Scott Strassels, PhD, PharmD, BCPS, an assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin and a board member of the American Pain Society, discuss the risks and rewards of opioid therapies, and why continuing education is important for all clinicians.

Click here to listen to Scott Strassels, PhD, PharmD, BCPS, an assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin and a board member of the American Pain Society, discuss the risks and rewards of opioid therapies, and why continuing education is important for all clinicians.

Increased Ordering of Diagnostic Tests Associated with Longer Lengths of Stay in Pediatric Pneumonia

Clinical question: What is the relationship between variation in resource utilization and outcomes in children with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Variation in clinical care, particularly when driven by provider preferences, often highlights opportunities for improvement in the quality of our care. CAP is one of the most common reasons for hospitalization in children. The relationship between variation in care processes, utilization, and outcomes in pediatric CAP is not well defined.

Study design: Retrospective database review.

Setting: Twenty-nine freestanding children's hospitals.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database was used to review utilization and outcomes data on 43,819 children admitted with nonsevere CAP during a five-year period. Substantial degrees of variation in test ordering, empiric antibiotic selection, length of stay (LOS), and 14-day readmissions were found. An association was noted between increased resource utilization—specifically, ordering of diagnostic tests—and longer LOS.

The association between increased resource utilization and LOS has been suggested in other work in respiratory illness in children. Although the retrospective nature of this work precludes detailed resolution of whether confounding by severity was an issue, this appears unlikely based on the relatively homogeneous patient populations and hospital types. Additional limitations of this work exist, and include an inability to further assess the appropriateness of the testing that was ordered—as well as relatively crude rankings of hospitals based on resource utilization. Nevertheless, in an era where a premium is placed on finding value in clinical medicine, these results should prompt further exploration of the link between testing and LOS in children hospitalized with CAP.

Bottom line: Unnecessary testing in children hospitalized with pneumonia may lead to longer LOS.

Citation: Brogan TV, Hall M, Williams DJ, et al. Variability in processes of care and outcomes among children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Ped Infect Dis J. 2012;31:1036-1041.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between variation in resource utilization and outcomes in children with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Variation in clinical care, particularly when driven by provider preferences, often highlights opportunities for improvement in the quality of our care. CAP is one of the most common reasons for hospitalization in children. The relationship between variation in care processes, utilization, and outcomes in pediatric CAP is not well defined.

Study design: Retrospective database review.

Setting: Twenty-nine freestanding children's hospitals.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database was used to review utilization and outcomes data on 43,819 children admitted with nonsevere CAP during a five-year period. Substantial degrees of variation in test ordering, empiric antibiotic selection, length of stay (LOS), and 14-day readmissions were found. An association was noted between increased resource utilization—specifically, ordering of diagnostic tests—and longer LOS.

The association between increased resource utilization and LOS has been suggested in other work in respiratory illness in children. Although the retrospective nature of this work precludes detailed resolution of whether confounding by severity was an issue, this appears unlikely based on the relatively homogeneous patient populations and hospital types. Additional limitations of this work exist, and include an inability to further assess the appropriateness of the testing that was ordered—as well as relatively crude rankings of hospitals based on resource utilization. Nevertheless, in an era where a premium is placed on finding value in clinical medicine, these results should prompt further exploration of the link between testing and LOS in children hospitalized with CAP.

Bottom line: Unnecessary testing in children hospitalized with pneumonia may lead to longer LOS.

Citation: Brogan TV, Hall M, Williams DJ, et al. Variability in processes of care and outcomes among children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Ped Infect Dis J. 2012;31:1036-1041.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between variation in resource utilization and outcomes in children with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Variation in clinical care, particularly when driven by provider preferences, often highlights opportunities for improvement in the quality of our care. CAP is one of the most common reasons for hospitalization in children. The relationship between variation in care processes, utilization, and outcomes in pediatric CAP is not well defined.

Study design: Retrospective database review.

Setting: Twenty-nine freestanding children's hospitals.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database was used to review utilization and outcomes data on 43,819 children admitted with nonsevere CAP during a five-year period. Substantial degrees of variation in test ordering, empiric antibiotic selection, length of stay (LOS), and 14-day readmissions were found. An association was noted between increased resource utilization—specifically, ordering of diagnostic tests—and longer LOS.

The association between increased resource utilization and LOS has been suggested in other work in respiratory illness in children. Although the retrospective nature of this work precludes detailed resolution of whether confounding by severity was an issue, this appears unlikely based on the relatively homogeneous patient populations and hospital types. Additional limitations of this work exist, and include an inability to further assess the appropriateness of the testing that was ordered—as well as relatively crude rankings of hospitals based on resource utilization. Nevertheless, in an era where a premium is placed on finding value in clinical medicine, these results should prompt further exploration of the link between testing and LOS in children hospitalized with CAP.

Bottom line: Unnecessary testing in children hospitalized with pneumonia may lead to longer LOS.

Citation: Brogan TV, Hall M, Williams DJ, et al. Variability in processes of care and outcomes among children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Ped Infect Dis J. 2012;31:1036-1041.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

How Hospitalists Can Improve the Care of Patients on Opioids

Pain is one of the chief complaints that results in patient admissions to the hospital. Hospitalists inevitably confront pain issues every day, says Joe A. Contreras, MD, FAAHPM, chair of the Pain and Palliative Medicine Institute at Hackensack University Medical Center in Hackensack, N.J. As a result, “it is expected that all physicians who take care of sick people have some baseline knowledge of opioids use,” Dr. Contreras says.

There is a preference on the public’s part and, consequently, from the physician’s perspective to treat pain with opioids, even though minor cases can be controlled without pharmacologic interventions, Dr. Contreras says. Patients might receive some relief from repositioning, hot or cold packs, extra pillows, Reiki therapy, and other soothing modalities. Additionally, hospitals can benefit from having a pain champion on staff to safely manage various situations.

A hospitalist should still obtain important and relevant information when a patient is admitted. This includes the pain medicine the patient is taking and how often, who prescribed it, whether it helps, and if the patient has experienced side effects.

“As the primary-care physician in the hospital,” Dr. Liao says, “the hospitalist is ultimately responsible.”

Special attention is needed during care transitions.

“This is when patients are most vulnerable,” says Beth B. Murinson, MS, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of pain education in the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

These situations occur during transfers from the ED or recovery room to an inpatient unit, and from hospital to home or skilled nursing facility. Patients being discharged must be thoroughly informed about their opioid pain relievers, Dr. Murinson says, with instructions to store them in a secure place. TH

Susan Kreimer is a freelance writer in New York City.

Pain is one of the chief complaints that results in patient admissions to the hospital. Hospitalists inevitably confront pain issues every day, says Joe A. Contreras, MD, FAAHPM, chair of the Pain and Palliative Medicine Institute at Hackensack University Medical Center in Hackensack, N.J. As a result, “it is expected that all physicians who take care of sick people have some baseline knowledge of opioids use,” Dr. Contreras says.

There is a preference on the public’s part and, consequently, from the physician’s perspective to treat pain with opioids, even though minor cases can be controlled without pharmacologic interventions, Dr. Contreras says. Patients might receive some relief from repositioning, hot or cold packs, extra pillows, Reiki therapy, and other soothing modalities. Additionally, hospitals can benefit from having a pain champion on staff to safely manage various situations.

A hospitalist should still obtain important and relevant information when a patient is admitted. This includes the pain medicine the patient is taking and how often, who prescribed it, whether it helps, and if the patient has experienced side effects.

“As the primary-care physician in the hospital,” Dr. Liao says, “the hospitalist is ultimately responsible.”

Special attention is needed during care transitions.

“This is when patients are most vulnerable,” says Beth B. Murinson, MS, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of pain education in the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

These situations occur during transfers from the ED or recovery room to an inpatient unit, and from hospital to home or skilled nursing facility. Patients being discharged must be thoroughly informed about their opioid pain relievers, Dr. Murinson says, with instructions to store them in a secure place. TH

Susan Kreimer is a freelance writer in New York City.

Pain is one of the chief complaints that results in patient admissions to the hospital. Hospitalists inevitably confront pain issues every day, says Joe A. Contreras, MD, FAAHPM, chair of the Pain and Palliative Medicine Institute at Hackensack University Medical Center in Hackensack, N.J. As a result, “it is expected that all physicians who take care of sick people have some baseline knowledge of opioids use,” Dr. Contreras says.

There is a preference on the public’s part and, consequently, from the physician’s perspective to treat pain with opioids, even though minor cases can be controlled without pharmacologic interventions, Dr. Contreras says. Patients might receive some relief from repositioning, hot or cold packs, extra pillows, Reiki therapy, and other soothing modalities. Additionally, hospitals can benefit from having a pain champion on staff to safely manage various situations.

A hospitalist should still obtain important and relevant information when a patient is admitted. This includes the pain medicine the patient is taking and how often, who prescribed it, whether it helps, and if the patient has experienced side effects.

“As the primary-care physician in the hospital,” Dr. Liao says, “the hospitalist is ultimately responsible.”

Special attention is needed during care transitions.

“This is when patients are most vulnerable,” says Beth B. Murinson, MS, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of pain education in the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

These situations occur during transfers from the ED or recovery room to an inpatient unit, and from hospital to home or skilled nursing facility. Patients being discharged must be thoroughly informed about their opioid pain relievers, Dr. Murinson says, with instructions to store them in a secure place. TH

Susan Kreimer is a freelance writer in New York City.