User login

VIDEO: Five Reasons You Should Attend Hospital Medicine 2013 in Washington, D.C.

Clinical Guidelines Updated for Surviving Sepsis in Hospitals

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign (www.survivingsepsis.org) has updated its best clinical practices for patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.6 Sixty-eight international experts worked to update the campaign’s 2008 guidelines. For example, the update includes a strong recommendation for the use of crystalloids (e.g. normal saline) as the initial fluid resuscitation for patients with severe sepsis.

The campaign, a collaboration of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, estimates 400,000 lives could be saved per year worldwide if 10,000 hospitals were committed to its recommendations and if even half of eligible patients were treated in conformance with the campaign’s quality bundles. The campaign also tries to develop strategies for improving the care of septic patients in settings where healthcare resources are limited.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Reference

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign (www.survivingsepsis.org) has updated its best clinical practices for patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.6 Sixty-eight international experts worked to update the campaign’s 2008 guidelines. For example, the update includes a strong recommendation for the use of crystalloids (e.g. normal saline) as the initial fluid resuscitation for patients with severe sepsis.

The campaign, a collaboration of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, estimates 400,000 lives could be saved per year worldwide if 10,000 hospitals were committed to its recommendations and if even half of eligible patients were treated in conformance with the campaign’s quality bundles. The campaign also tries to develop strategies for improving the care of septic patients in settings where healthcare resources are limited.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Reference

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign (www.survivingsepsis.org) has updated its best clinical practices for patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.6 Sixty-eight international experts worked to update the campaign’s 2008 guidelines. For example, the update includes a strong recommendation for the use of crystalloids (e.g. normal saline) as the initial fluid resuscitation for patients with severe sepsis.

The campaign, a collaboration of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, estimates 400,000 lives could be saved per year worldwide if 10,000 hospitals were committed to its recommendations and if even half of eligible patients were treated in conformance with the campaign’s quality bundles. The campaign also tries to develop strategies for improving the care of septic patients in settings where healthcare resources are limited.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Reference

Robotic Vaporizers Reduce Hospital Bacterial Infections

Paired, robotlike devices that disperse a bleaching disinfectant into the air of hospital rooms, then detoxify the disinfecting chemical, were found to be highly effective at killing and preventing the spread of “superbug” bacteria, according to research from Johns Hopkins Hospital published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.5 Hydrogen peroxide vaporizers were first deployed in Singapore hospitals in 2002 during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

Almost half of a study group of 6,350 patients in and out of 180 hospital rooms over a two-and-a-half-year period received the enhanced cleaning technology, while the others received routine cleaning only. Manufactured by Bioquell Inc. of Horsham, Pa. (www.bioquell.com), each device is about the size of a washing machine. They were deployed in hospital rooms with sealed vents, dispersing a thin film of hydrogen peroxide across all exposed surfaces, equipment, floors, and walls. This approach reduced by 64% the number of patients who later became contaminated with any of the most common drug-resistant organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Clostridium difficile, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Spreading the bleaching vapor this way “represents a major technological advance in preventing the spread of dangerous bacteria inside hospital rooms,” says senior investigator Trish Perl, MD, MSc, professor of medicine and an infectious disease specialist at Johns Hopkins. The hospital announced in December that it would begin decontaminating isolation rooms with these devices as standard practice starting in January.

Reference

Paired, robotlike devices that disperse a bleaching disinfectant into the air of hospital rooms, then detoxify the disinfecting chemical, were found to be highly effective at killing and preventing the spread of “superbug” bacteria, according to research from Johns Hopkins Hospital published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.5 Hydrogen peroxide vaporizers were first deployed in Singapore hospitals in 2002 during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

Almost half of a study group of 6,350 patients in and out of 180 hospital rooms over a two-and-a-half-year period received the enhanced cleaning technology, while the others received routine cleaning only. Manufactured by Bioquell Inc. of Horsham, Pa. (www.bioquell.com), each device is about the size of a washing machine. They were deployed in hospital rooms with sealed vents, dispersing a thin film of hydrogen peroxide across all exposed surfaces, equipment, floors, and walls. This approach reduced by 64% the number of patients who later became contaminated with any of the most common drug-resistant organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Clostridium difficile, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Spreading the bleaching vapor this way “represents a major technological advance in preventing the spread of dangerous bacteria inside hospital rooms,” says senior investigator Trish Perl, MD, MSc, professor of medicine and an infectious disease specialist at Johns Hopkins. The hospital announced in December that it would begin decontaminating isolation rooms with these devices as standard practice starting in January.

Reference

Paired, robotlike devices that disperse a bleaching disinfectant into the air of hospital rooms, then detoxify the disinfecting chemical, were found to be highly effective at killing and preventing the spread of “superbug” bacteria, according to research from Johns Hopkins Hospital published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.5 Hydrogen peroxide vaporizers were first deployed in Singapore hospitals in 2002 during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

Almost half of a study group of 6,350 patients in and out of 180 hospital rooms over a two-and-a-half-year period received the enhanced cleaning technology, while the others received routine cleaning only. Manufactured by Bioquell Inc. of Horsham, Pa. (www.bioquell.com), each device is about the size of a washing machine. They were deployed in hospital rooms with sealed vents, dispersing a thin film of hydrogen peroxide across all exposed surfaces, equipment, floors, and walls. This approach reduced by 64% the number of patients who later became contaminated with any of the most common drug-resistant organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Clostridium difficile, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Spreading the bleaching vapor this way “represents a major technological advance in preventing the spread of dangerous bacteria inside hospital rooms,” says senior investigator Trish Perl, MD, MSc, professor of medicine and an infectious disease specialist at Johns Hopkins. The hospital announced in December that it would begin decontaminating isolation rooms with these devices as standard practice starting in January.

Reference

Digital Diagnostic Tools Unpopular with Patients, Study Finds

A recent study from the University of Missouri to explore how patients react to physicians’ use of computerized clinical decision support systems finds that these devices could leave patients feeling ignored and dissatisfied with their medical care, potentially increasing noncompliance with treatment while distracting physicians from the patient encounter.1

“Patients may be concerned that the decision aids reduce their face-to-face time with physicians,” says lead author Victoria Shaffer, PhD, assistant professor of health and psychological sciences at the University of Missouri. She recommends incorporating computerized systems as teaching tools to engage patients and help them understand their diagnoses and recommendations. “Anything physicians or nurses can do to humanize the process may make patients more comfortable,” she says.

The study presented participants with written descriptions of hypothetical physician-patient encounters, with the physician using unaided judgment, pursuing advice from a medical expert, or using computerized clinical decision support. Physicians using the latter were viewed as less capable, but participants also were less likely to assign those physicians responsibility for negative outcomes.

A concurrent study from Missouri, part of a $14 million project funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to reduce avoidable rehospitalizations of nursing home residents, suggests that sophisticated information technology (IT) can lead to more robust and integrated communication strategies among clinical staff, as well as better-coordinated care.2 Nursing informatics expert Gregory Alexander found that nursing homes with IT used it to help make clinical decisions, electronically track patient care, and securely relay medical information.

References

- Shaffer VA, Probst CA, Merkle EC, Arkes HR, Mitchell AM. Why do patients derogate physicians who use a computer-based diagnostic support system? Med Decis Making. 2013;33(1):108-118.

- Alexander GL, Steege LM, Pasupathy KS, Wise K. Case studies of IT sophistication in nursing homes: a mixed method approach to examine communication strategies about pressure ulcer prevention practices. SciVerse website. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169814112001229. Accessed March 10, 2013.

A recent study from the University of Missouri to explore how patients react to physicians’ use of computerized clinical decision support systems finds that these devices could leave patients feeling ignored and dissatisfied with their medical care, potentially increasing noncompliance with treatment while distracting physicians from the patient encounter.1

“Patients may be concerned that the decision aids reduce their face-to-face time with physicians,” says lead author Victoria Shaffer, PhD, assistant professor of health and psychological sciences at the University of Missouri. She recommends incorporating computerized systems as teaching tools to engage patients and help them understand their diagnoses and recommendations. “Anything physicians or nurses can do to humanize the process may make patients more comfortable,” she says.

The study presented participants with written descriptions of hypothetical physician-patient encounters, with the physician using unaided judgment, pursuing advice from a medical expert, or using computerized clinical decision support. Physicians using the latter were viewed as less capable, but participants also were less likely to assign those physicians responsibility for negative outcomes.

A concurrent study from Missouri, part of a $14 million project funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to reduce avoidable rehospitalizations of nursing home residents, suggests that sophisticated information technology (IT) can lead to more robust and integrated communication strategies among clinical staff, as well as better-coordinated care.2 Nursing informatics expert Gregory Alexander found that nursing homes with IT used it to help make clinical decisions, electronically track patient care, and securely relay medical information.

References

- Shaffer VA, Probst CA, Merkle EC, Arkes HR, Mitchell AM. Why do patients derogate physicians who use a computer-based diagnostic support system? Med Decis Making. 2013;33(1):108-118.

- Alexander GL, Steege LM, Pasupathy KS, Wise K. Case studies of IT sophistication in nursing homes: a mixed method approach to examine communication strategies about pressure ulcer prevention practices. SciVerse website. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169814112001229. Accessed March 10, 2013.

A recent study from the University of Missouri to explore how patients react to physicians’ use of computerized clinical decision support systems finds that these devices could leave patients feeling ignored and dissatisfied with their medical care, potentially increasing noncompliance with treatment while distracting physicians from the patient encounter.1

“Patients may be concerned that the decision aids reduce their face-to-face time with physicians,” says lead author Victoria Shaffer, PhD, assistant professor of health and psychological sciences at the University of Missouri. She recommends incorporating computerized systems as teaching tools to engage patients and help them understand their diagnoses and recommendations. “Anything physicians or nurses can do to humanize the process may make patients more comfortable,” she says.

The study presented participants with written descriptions of hypothetical physician-patient encounters, with the physician using unaided judgment, pursuing advice from a medical expert, or using computerized clinical decision support. Physicians using the latter were viewed as less capable, but participants also were less likely to assign those physicians responsibility for negative outcomes.

A concurrent study from Missouri, part of a $14 million project funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to reduce avoidable rehospitalizations of nursing home residents, suggests that sophisticated information technology (IT) can lead to more robust and integrated communication strategies among clinical staff, as well as better-coordinated care.2 Nursing informatics expert Gregory Alexander found that nursing homes with IT used it to help make clinical decisions, electronically track patient care, and securely relay medical information.

References

- Shaffer VA, Probst CA, Merkle EC, Arkes HR, Mitchell AM. Why do patients derogate physicians who use a computer-based diagnostic support system? Med Decis Making. 2013;33(1):108-118.

- Alexander GL, Steege LM, Pasupathy KS, Wise K. Case studies of IT sophistication in nursing homes: a mixed method approach to examine communication strategies about pressure ulcer prevention practices. SciVerse website. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169814112001229. Accessed March 10, 2013.

National Medicare Readmissions Study Identifies Little Progress

A new Dartmouth Atlas Project study of Medicare 30-day hospital readmissions found that rates essentially stayed the same (15.9% for medical discharges) between 2008 and 2010. But readmission rates varied widely across regions, with medical discharges at 18.1% in Bronx, N.Y., versus 11.4% in Ogden, Utah.

The report, The Revolving Door: A Report on U.S. Hospital Readmissions, also incorporates results from in-depth interviews with patients and providers.1 It sheds light on why so many patients (1 in 6 medical and 1 in 8 surgical discharges) end up back in the hospital so soon—and what hospitals, physicians, nurses, and others are doing to limit avoidable readmissions.

An online interactive map (available at www.rwjf.org) displays the Dartmouth data on 30-day readmissions by hospital referral region.

The research was supported and publicized by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation of Princeton, N.J., which has a number of other efforts under way to address readmissions. Another recent study supported by the foundation’s Nurse Faculty Scholars Program found that increased nurse-to-patient staffing ratios and good working environments for nurses were associated with significantly reduced 30-day readmissions.2

The foundation recently named the five winners of its “Transitions to Better Care” video contest, in which hospitals and health systems submitted short films to highlight innovative local practices to improve care transitions before, during, and after discharge. Check out the winning videos by searching “contest” at rwjf.org.

References

- The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. The Revolving Door: A Report on U.S. Hospital Readmissions. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care website. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/pages/readmissions2013. Accessed March 10, 2013.

- McHugh M, Ma C. Hospital nursing and 30-day readmissions among Medicare patients with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. Med Care. 2013;51(1):52-59.

A new Dartmouth Atlas Project study of Medicare 30-day hospital readmissions found that rates essentially stayed the same (15.9% for medical discharges) between 2008 and 2010. But readmission rates varied widely across regions, with medical discharges at 18.1% in Bronx, N.Y., versus 11.4% in Ogden, Utah.

The report, The Revolving Door: A Report on U.S. Hospital Readmissions, also incorporates results from in-depth interviews with patients and providers.1 It sheds light on why so many patients (1 in 6 medical and 1 in 8 surgical discharges) end up back in the hospital so soon—and what hospitals, physicians, nurses, and others are doing to limit avoidable readmissions.

An online interactive map (available at www.rwjf.org) displays the Dartmouth data on 30-day readmissions by hospital referral region.

The research was supported and publicized by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation of Princeton, N.J., which has a number of other efforts under way to address readmissions. Another recent study supported by the foundation’s Nurse Faculty Scholars Program found that increased nurse-to-patient staffing ratios and good working environments for nurses were associated with significantly reduced 30-day readmissions.2

The foundation recently named the five winners of its “Transitions to Better Care” video contest, in which hospitals and health systems submitted short films to highlight innovative local practices to improve care transitions before, during, and after discharge. Check out the winning videos by searching “contest” at rwjf.org.

References

- The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. The Revolving Door: A Report on U.S. Hospital Readmissions. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care website. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/pages/readmissions2013. Accessed March 10, 2013.

- McHugh M, Ma C. Hospital nursing and 30-day readmissions among Medicare patients with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. Med Care. 2013;51(1):52-59.

A new Dartmouth Atlas Project study of Medicare 30-day hospital readmissions found that rates essentially stayed the same (15.9% for medical discharges) between 2008 and 2010. But readmission rates varied widely across regions, with medical discharges at 18.1% in Bronx, N.Y., versus 11.4% in Ogden, Utah.

The report, The Revolving Door: A Report on U.S. Hospital Readmissions, also incorporates results from in-depth interviews with patients and providers.1 It sheds light on why so many patients (1 in 6 medical and 1 in 8 surgical discharges) end up back in the hospital so soon—and what hospitals, physicians, nurses, and others are doing to limit avoidable readmissions.

An online interactive map (available at www.rwjf.org) displays the Dartmouth data on 30-day readmissions by hospital referral region.

The research was supported and publicized by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation of Princeton, N.J., which has a number of other efforts under way to address readmissions. Another recent study supported by the foundation’s Nurse Faculty Scholars Program found that increased nurse-to-patient staffing ratios and good working environments for nurses were associated with significantly reduced 30-day readmissions.2

The foundation recently named the five winners of its “Transitions to Better Care” video contest, in which hospitals and health systems submitted short films to highlight innovative local practices to improve care transitions before, during, and after discharge. Check out the winning videos by searching “contest” at rwjf.org.

References

- The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. The Revolving Door: A Report on U.S. Hospital Readmissions. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care website. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/pages/readmissions2013. Accessed March 10, 2013.

- McHugh M, Ma C. Hospital nursing and 30-day readmissions among Medicare patients with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. Med Care. 2013;51(1):52-59.

Short QT syndrome

To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Drs. Al Maluli and Meshkov on short QT syndrome in the January 2013 issue.1 We are wondering whether Holter monitoring and giving a beta-blocker can help in the diagnosis of this syndrome.

Compared with the normal population, patients with short QT syndrome have less variation of the QT interval in relation to the change in heart rate. This will result in misinterpretation of the corrected QT interval with a faster heart rate and subsequently false-negative diagnosis of this possibly fatal syndrome. Holter monitoring can be helpful in this situation because it allows measurement of the corrected QT interval during a period of slower heart rate, such as sleep.

Bjerregaard2 mentioned the use of a beta-blocker to slow the heart rate when measuring the corrected QT interval. According to the diagnostic criteria, a shorter corrected QT interval correlates with a higher probability of short QT syndrome. Using the above measures may reveal the true corrected QT interval and improve the diagnostic accuracy of short QT syndrome in patients with a rapid heart rate.

- Al Maluli H, Meshkov AB. A short story of the short QT syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 2013; 80:40–47.

- Bjerregaard P. Proposed diagnostic criteria for short QT syndrome are badly founded. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:549–550.

To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Drs. Al Maluli and Meshkov on short QT syndrome in the January 2013 issue.1 We are wondering whether Holter monitoring and giving a beta-blocker can help in the diagnosis of this syndrome.

Compared with the normal population, patients with short QT syndrome have less variation of the QT interval in relation to the change in heart rate. This will result in misinterpretation of the corrected QT interval with a faster heart rate and subsequently false-negative diagnosis of this possibly fatal syndrome. Holter monitoring can be helpful in this situation because it allows measurement of the corrected QT interval during a period of slower heart rate, such as sleep.

Bjerregaard2 mentioned the use of a beta-blocker to slow the heart rate when measuring the corrected QT interval. According to the diagnostic criteria, a shorter corrected QT interval correlates with a higher probability of short QT syndrome. Using the above measures may reveal the true corrected QT interval and improve the diagnostic accuracy of short QT syndrome in patients with a rapid heart rate.

To the Editor: We read with great interest the article by Drs. Al Maluli and Meshkov on short QT syndrome in the January 2013 issue.1 We are wondering whether Holter monitoring and giving a beta-blocker can help in the diagnosis of this syndrome.

Compared with the normal population, patients with short QT syndrome have less variation of the QT interval in relation to the change in heart rate. This will result in misinterpretation of the corrected QT interval with a faster heart rate and subsequently false-negative diagnosis of this possibly fatal syndrome. Holter monitoring can be helpful in this situation because it allows measurement of the corrected QT interval during a period of slower heart rate, such as sleep.

Bjerregaard2 mentioned the use of a beta-blocker to slow the heart rate when measuring the corrected QT interval. According to the diagnostic criteria, a shorter corrected QT interval correlates with a higher probability of short QT syndrome. Using the above measures may reveal the true corrected QT interval and improve the diagnostic accuracy of short QT syndrome in patients with a rapid heart rate.

- Al Maluli H, Meshkov AB. A short story of the short QT syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 2013; 80:40–47.

- Bjerregaard P. Proposed diagnostic criteria for short QT syndrome are badly founded. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:549–550.

- Al Maluli H, Meshkov AB. A short story of the short QT syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med 2013; 80:40–47.

- Bjerregaard P. Proposed diagnostic criteria for short QT syndrome are badly founded. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:549–550.

In reply: Short QT syndrome

In Reply: We thank Dr. Ratanapo and colleagues for their interest in our article. As we mentioned in our paper, and as they emphasized, the QT interval response to heart rate variation seems to be minimal. They wonder if using a beta-blockers in addition to Holter monitoring can provide a better estimate of the “true corrected QT interval” since it will allow the measurement of corrected QT with slower heart rates. While we agree that Holter monitoring may provide an opportunity to observe the lack of prolongation of the QT interval when the heart rate slows down naturally (eg, during sleep), we have reservations about the other points.

First, we prefer not to use the term “true corrected QT interval” because, as we mentioned in our article, the correction formulas do not perform well in short QT syndrome. A better thing would be to use the QT interval itself, no matter what the heart rate is.

Second, whether beta-blockers would alter the heart rate without altering the QT interval is something that deserves to be evaluated in patients with an established diagnosis of short QT syndrome. Since catecholamines can cause shortening of the QT interval,1 could beta-blockers have a different effect on the QT interval in patients with and without short QT syndrome? To our knowledge, there are no data that specifically address this question.

The last point we would like to emphasize is the complexity of making the diagnosis of short QT syndrome. Electrocardiographic criteria, especially when equivocal, should probably not be the sole diagnostic basis for short QT syndrome. A personal or family history of arrhythmias, with or without genetic testing, has additive value as demonstrated by the excellent paper by Gollob et al.2

- Bjerregaard P, Gusak I. Short QT syndrome: mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2005; 2:84–87.

- Gollob MH, Redpath CJ, Roberts JD. The short QT syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:802–812.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Ratanapo and colleagues for their interest in our article. As we mentioned in our paper, and as they emphasized, the QT interval response to heart rate variation seems to be minimal. They wonder if using a beta-blockers in addition to Holter monitoring can provide a better estimate of the “true corrected QT interval” since it will allow the measurement of corrected QT with slower heart rates. While we agree that Holter monitoring may provide an opportunity to observe the lack of prolongation of the QT interval when the heart rate slows down naturally (eg, during sleep), we have reservations about the other points.

First, we prefer not to use the term “true corrected QT interval” because, as we mentioned in our article, the correction formulas do not perform well in short QT syndrome. A better thing would be to use the QT interval itself, no matter what the heart rate is.

Second, whether beta-blockers would alter the heart rate without altering the QT interval is something that deserves to be evaluated in patients with an established diagnosis of short QT syndrome. Since catecholamines can cause shortening of the QT interval,1 could beta-blockers have a different effect on the QT interval in patients with and without short QT syndrome? To our knowledge, there are no data that specifically address this question.

The last point we would like to emphasize is the complexity of making the diagnosis of short QT syndrome. Electrocardiographic criteria, especially when equivocal, should probably not be the sole diagnostic basis for short QT syndrome. A personal or family history of arrhythmias, with or without genetic testing, has additive value as demonstrated by the excellent paper by Gollob et al.2

In Reply: We thank Dr. Ratanapo and colleagues for their interest in our article. As we mentioned in our paper, and as they emphasized, the QT interval response to heart rate variation seems to be minimal. They wonder if using a beta-blockers in addition to Holter monitoring can provide a better estimate of the “true corrected QT interval” since it will allow the measurement of corrected QT with slower heart rates. While we agree that Holter monitoring may provide an opportunity to observe the lack of prolongation of the QT interval when the heart rate slows down naturally (eg, during sleep), we have reservations about the other points.

First, we prefer not to use the term “true corrected QT interval” because, as we mentioned in our article, the correction formulas do not perform well in short QT syndrome. A better thing would be to use the QT interval itself, no matter what the heart rate is.

Second, whether beta-blockers would alter the heart rate without altering the QT interval is something that deserves to be evaluated in patients with an established diagnosis of short QT syndrome. Since catecholamines can cause shortening of the QT interval,1 could beta-blockers have a different effect on the QT interval in patients with and without short QT syndrome? To our knowledge, there are no data that specifically address this question.

The last point we would like to emphasize is the complexity of making the diagnosis of short QT syndrome. Electrocardiographic criteria, especially when equivocal, should probably not be the sole diagnostic basis for short QT syndrome. A personal or family history of arrhythmias, with or without genetic testing, has additive value as demonstrated by the excellent paper by Gollob et al.2

- Bjerregaard P, Gusak I. Short QT syndrome: mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2005; 2:84–87.

- Gollob MH, Redpath CJ, Roberts JD. The short QT syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:802–812.

- Bjerregaard P, Gusak I. Short QT syndrome: mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2005; 2:84–87.

- Gollob MH, Redpath CJ, Roberts JD. The short QT syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:802–812.

Options for managing severe aortic stenosis: A case-based review

Surgical aortic valve replacement remains the gold standard treatment for symptomatic aortic valve stenosis in patients at low or moderate risk of surgical complications. But this is a disease of the elderly, many of whom are too frail or too sick to undergo surgery.

Now, patients who cannot undergo this surgery can be offered the less invasive option of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Balloon valvuloplasty, sodium nitroprusside, and intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation can buy time for ill patients while more permanent mechanical interventions are being considered.

In this review, we will present several cases that highlight management choices for patients with severe aortic stenosis.

A PROGRESSIVE DISEASE OF THE ELDERLY

Aortic stenosis is the most common acquired valvular disease in the United States, and its incidence and prevalence are rising as the population ages. Epidemiologic studies suggest that 2% to 7% of all patients over age 65 have it.1,2

The natural history of the untreated disease is well established, with several case series showing an average decrease of 0.1 cm2 per year in aortic valve area and an increase of 7 mm Hg per year in the pressure gradient across the valve once the diagnosis is made.3,4 Development of angina, syncope, or heart failure is associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including death, and warrants prompt intervention with aortic valve replacement.5–7 Without intervention, the mortality rates reach as high as 75% in 3 years once symptoms develop.

Statins, bisphosphonates, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have been used in attempts to slow or reverse the progression of aortic stenosis. However, studies of these drugs have had mixed results, and no definitive benefit has been shown.8–13 Surgical aortic valve replacement, on the other hand, normalizes the life expectancy of patients with aortic stenosis to that of age- and sex-matched controls and remains the gold standard therapy for patients who have symptoms.14

Traditionally, valve replacement has involved open heart surgery, since it requires direct visualization of the valve while the patient is on cardiopulmonary bypass. Unfortunately, many patients have multiple comorbid conditions and therefore are not candidates for open heart surgery. Options for these patients include aortic valvuloplasty and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. While there is considerable experience with aortic valvuloplasty, transcatheter aortic valve replacement is relatively new. In large randomized trials and registries, the transcatheter procedure has been shown to significantly improve long-term survival compared with medical management alone in inoperable patients and to have benefit similar to that of surgery in the high-risk population.15–17

CASE 1: SEVERE, SYMPTOMATIC STENOSIS IN A GOOD SURGICAL CANDIDATE

Mr. A, age 83, presents with shortness of breath and peripheral edema that have been worsening over the past several months. His pulse rate is 64 beats per minute and his blood pressure is 110/90 mm Hg. Auscultation reveals an absent aortic second heart sound with a late peaking systolic murmur that increases with expiration.

On echocardiography, his left ventricular ejection fraction is 55%, peak transaortic valve gradient 88 mm Hg, mean gradient 60 mm Hg, and effective valve area 0.6 cm2. He undergoes catheterization of the left side of his heart, which shows normal coronary arteries.

Mr. A also has hypertension and hyperlipidemia; his renal and pulmonary functions are normal.

How would you manage Mr. A’s aortic stenosis?

Symptomatic aortic stenosis leads to adverse clinical outcomes if managed medically without mechanical intervention,5–7 but patients who undergo aortic valve replacement have age-corrected postoperative survival rates that are nearly normal.14 Furthermore, thanks to improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative management, surgical mortality rates have decreased significantly in recent years and now range from 1% to 8%.18–20 The accumulated evidence showing clear superiority of a surgical approach over medical therapy has greatly simplified the therapeutic algorithm.21

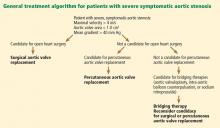

Consequently, the current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) give surgery a class I indication (evidence or general agreement that the procedure is beneficial, useful, and effective) for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (Figure 1). This level of recommendation also applies to patients who have severe but asymptomatic aortic stenosis who are undergoing other types of cardiac surgery and also to patients with severe aortic stenosis and left ventricular dysfunction (defined as an ejection fraction < 50%).21

Mr. A was referred for surgical aortic valve replacement, given its clear survival benefit.

CASE 2: SYMPTOMS AND LEFT VENTRICULAR DYSFUNCTION

Ms. B, age 79, has hypertension and hyperlipidemia and now presents to the outpatient department with worsening shortness of breath and chest discomfort. Electrocardiography shows significant left ventricular hypertrophy and abnormal repolarization. Left heart catheterization reveals mild nonobstructive coronary artery disease.

Echocardiography reveals an ejection fraction of 25%, severe left ventricular hypertrophy, and global hypokinesis. The aortic valve leaflets appear heavily calcified, with restricted motion. The peak and mean gradients across the aortic valve are 40 and 28 mm Hg, and the valve area is 0.8 cm2. Right heart catheterization shows a cardiac output of 3.1 L/min.

Does this patient’s aortic stenosis account for her clinical presentation?

Managing patients who have suspected severe aortic stenosis, left ventricular dysfunction, and low aortic valve gradients can be challenging. Although data for surgical intervention are not as robust for these patient subsets as for patients like Mr. A, several case series have suggested that survival in these patients is significantly better with surgery than with medical therapy alone.22–27

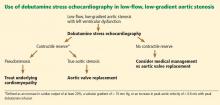

Specific factors predict whether patients with ventricular dysfunction and low gradients will benefit from aortic valve replacement. Dobutamine stress echocardiography is helpful in distinguishing true severe aortic stenosis from “pseudostenosis,” in which leaflet motion is restricted due to primary cardiomyopathy and low flow. Distinguishing between true aortic stenosis and pseudostenosis is of paramount value, as surgery is associated with improved long-term outcomes in patients with true aortic stenosis (even though they are at higher surgical risk), whereas those with pseudostenosis will not benefit from surgery.28–31

Infusion of dobutamine increases the flow across the aortic valve (if the left ventricle has contractile reserve; more on this below), and an increasing valve area with increasing doses of dobutamine is consistent with pseudostenosis. In this situation, treatment of the underlying cardiomyopathy is indicated as opposed to replacement of the aortic valve (Figure 2).

Contractile reserve is defined as an increase in stroke volume (> 20%), valvular gradient (> 10 mm Hg), or peak velocity (> 0.6 m/s) with peak dobutamine infusion. The presence of contractile reserve in patients with aortic stenosis identifies a high-risk group that benefits from aortic valve replacement (Figure 2).

Treatment of patients who have inadequate reserve is controversial. In the absence of contractile reserve, an adjunct imaging study such as computed tomography may be of value in detecting calcified valve leaflets, as the presence of calcium is associated with true aortic stenosis. Comorbid conditions should be taken into account as well, given the higher surgical risk in this patient subset, as aortic valve replacement in this already high-risk group of patients might be futile in some cases.

The ACC/AHA guidelines now give dobutamine stress echocardiography a class IIa indication (meaning the weight of the evidence or opinion is in favor of usefulness or efficacy) for determination of contractile reserve and valvular stenosis for patients with an ejection fraction of 30% or less or a mean gradient of 40 mm Hg or less.21

Ms. B underwent dobutamine stress echocardiography. It showed increases in ejection fraction, stroke volume, and transvalvular gradients, indicating that she did have contractile reserve and true severe aortic stenosis. Consequently, she was referred for surgical aortic valve replacement.

CASE 3: MODERATE STENOSIS AND THREE-VESSEL CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Mr. C, age 81, has hypertension and hyperlipidemia. He now presents to the emergency department with chest discomfort that began suddenly, awakening him from sleep. His presenting electrocardiogram shows nonspecific changes, and he is diagnosed with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. He undergoes left heart catheterization, which reveals severe three-vessel coronary artery disease.

Echocardiography reveals an ejection fraction of 55% and aortic stenosis, with an aortic valve area of 1.2 cm2, a peak gradient of 44 mm Hg, and a mean gradient of 28 mm Hg.

How would you manage his aortic stenosis?

Moderate aortic stenosis in a patient who needs surgery for severe triple-vessel coronary artery disease, other valve diseases, or aortic disease raises the question of whether aortic valve replacement should be performed in conjunction with these surgeries. Although these patients would not otherwise qualify for aortic valve replacement, the fact that they will undergo a procedure that will expose them to the risks associated with open heart surgery makes them reasonable candidates. Even if the patient does not need aortic valve replacement right now, aortic stenosis progresses at a predictable rate—the valve area decreases by a mean of 0.1 cm2/year and the gradients increase by 7 mm Hg/year. Therefore, clinical judgment should be exercised so that the patient will not need to undergo open heart surgery again in the near future.

The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend aortic valve replacement for patients with moderate aortic stenosis undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting or surgery on the aorta or other heart valves, giving it a class IIa indication.21 This recommendation is based on several retrospective case series that evaluated survival, the need for reoperation for aortic valve replacement, or both in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting.32–35

No data exist, however, on adding aortic valve replacement to coronary artery bypass grafting in cases of mild aortic stenosis. As a result, it is controversial and carries a class IIb recommendation (meaning that its usefulness or efficacy is less well established). The ACC/AHA guidelines state that aortic valve replacement “may be considered” in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting who have mild aortic stenosis (mean gradient < 30 mm Hg or jet velocity < 3 m/s) when there is evidence, such as moderate or severe valve calcification, that progression may be rapid (level of evidence C: based only on consensus opinion of experts, case studies or standard of care).21

Mr. C, who has moderate aortic stenosis, underwent aortic valve replacement in conjunction with three-vessel bypass grafting.

CASE 4: ASYMPTOMATIC BUT SEVERE STENOSIS

Mr. D, age 74, has hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and aortic stenosis. He now presents to the outpatient department for his annual echocardiogram to follow his aortic stenosis. He has a sedentary lifestyle but feels well performing activities of daily living. He denies dyspnea on exertion, chest pain, or syncope.

His echocardiogram reveals an effective aortic valve area of 0.7 cm2, peak gradient 90 mm Hg, and mean gradient 70 mm Hg. There is evidence of severe left ventricular hypertrophy, and the valve leaflets show bulky calcification and severe restriction. An echocardiogram performed at the same institution a year earlier revealed gradients of 60 and 40 mm Hg.

Blood is drawn for laboratory tests, including N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, which is 350 pg/mL (reference range for his age < 125 pg/mL). He is referred for a treadmill stress test, which elicits symptoms at a moderate activity level.

How would you manage his aortic stenosis?

Aortic valve replacement can be considered in patients who have asymptomatic but severe aortic stenosis with preserved left ventricular function (class IIb indication).21

Clinical assessment of asymptomatic aortic stenosis can be challenging, however, as patients may underreport their symptoms or decrease their activity levels to avoid symptoms. Exercise testing in such patients can elicit symptoms, unmask diminished exercise capacity, and help determine if they should be referred for surgery.36,37 Natriuretic peptide levels have been shown to correlate with the severity of aortic stenosis,38,39 and more importantly, to help predict symptom onset, cardiac death, and need for aortic valve replacement.40–42

Some patients with asymptomatic but severe aortic stenosis are at higher risk of morbidity and death. High-risk subsets include patients with rapid progression of aortic stenosis and those with critical aortic stenosis characterized by an aortic valve area less than 0.60 cm2, mean gradient greater than 60 mm Hg, and jet velocity greater than 5.0 m/s. It is reasonable to offer these patients surgery if their expected operative mortality risk is less than 1.0%.21

Mr. D has evidence of rapid progression as defined by an increase in aortic jet velocity of more than 0.3 m/s/year. He is at low surgical risk and was referred for elective aortic valve replacement.

CASE 5: TOO FRAIL FOR SURGERY

Mr. E, age 84, has severe aortic stenosis (valve area 0.6 cm2, peak and mean gradients of 88 and 56 mm Hg), coronary artery disease status post coronary artery bypass grafting, moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (forced expiratory volume in 1 second 0.8 L), chronic kidney disease (serum creatinine 1.9 mg/dL), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. He has preserved left ventricular function. He presents to the outpatient department with worsening shortness of breath and peripheral edema over the past several months. Your impression is that he is very frail. How would you manage Mr. E’s aortic stenosis?

Advances in surgical techniques and perioperative management over the years have enabled higher-risk patients to undergo surgical aortic valve replacement with excellent out-comes.18–20,43 Yet many patients still cannot undergo surgery because their risk is too high. Patients ineligible for surgery have traditionally been treated medically—with poor out-comes—or with balloon aortic valvuloplasty to palliate symptoms.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011, now provides another option for these patients. In this procedure, a bioprosthetic valve mounted on a metal frame is implanted over the native stenotic valve.

Currently, the only FDA-approved and commercially available valve in the United States is the Edwards SAPIEN valve, which has bovine pericardial tissue leaflets fixed to a balloon-expandable stainless steel frame (Figure 3). In the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial,15 patients who could not undergo surgery who underwent transcatheter replacement with this valve had a significantly better survival rate than patients treated medically.15,17 Use of this valve has also been compared against conventional surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients and was found to have similar long-term outcomes (Figure 4).16 It was on the basis of this trial that this valve was granted approval for patients who cannot undergo surgery.

The standard of care for high-risk patients remains surgical aortic valve replacement, although it remains to be seen whether transcatheter replacement will be made available as well to patients eligible for surgery in the near future. There are currently no randomized data for transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients at moderate to low surgical risk, and these patients should not be considered for this procedure.

Although the initial studies are encouraging for patients who cannot undergo surgery and who are at high risk without it, several issues and concerns remain. Importantly, the long-term durability of the transcatheter valve and longer-term outcomes remain unknown. Furthermore, the risk of vascular complications remains high (10% to 15%), dictating the need for careful patient selection. There are also concerns about the risks of stroke and of paravalvular aortic insufficiency. These issues are being investigated and addressed, however, and we hope that with increasing operator experience and improvements in the technique, outcomes will be improved.

Which approach for transcatheter aortic valve replacement?

There are several considerations in determining a patient’s eligibility for transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Initially, these valves were placed by a transvenous, transseptal approach, but now retrograde placement through the femoral artery has become standard. In this procedure, the device is advanced retrograde from the femoral artery through the aorta and placed across the native aortic valve under fluoroscopic and echocardiographic guidance.

Patients who are not eligible for transfemoral placement because of severe atherosclerosis, tortuosity, or ectasia of the iliofemoral artery or aorta can still undergo percutaneous treatment with a transapical approach. This is a hybrid surgical-transcatheter approach in which the valve is delivered through a sheath placed by left ventricular apical puncture.17,44

A newer approach gaining popularity is the transaortic technique, in which the ascending aorta is accessed directly through a ministernotomy and the delivery sheath is placed with a direct puncture. Other approaches are through the axillary and subclavian arteries.

Other valves are under development

Several other valves are under development and will likely change the landscape of transcatheter aortic valve replacement with improving outcomes. Valves that are available in the United States are shown in Figure 3. The CoreValve, consisting of porcine pericardial leaflets mounted on a self-expanding nitinol stent, is currently being studied in a trial in the United States, and the manufacturer (Medtronic) will seek approval when results are complete in the near future.

Mr. E was initially referred for surgery, but when deemed to be unable to undergo surgery was found to be a good candidate for transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

CASE 6: LIFE-LIMITING COMORBID ILLNESS

Mr. F, age 77, has multiple problems: severe aortic stenosis (aortic valve area 0.6 cm2; peak and mean gradients of 92 and 59 mm Hg), stage IV pancreatic cancer, coronary artery disease status post coronary artery bypass grafting, chronic kidney disease (serum creatinine 1.9 mg/dL), hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. He presents to the outpatient department with shortness of breath at rest, orthopnea, effort intolerance, and peripheral edema over the past several months.

On physical examination rales in both lung bases can be heard. Left heart catheterization shows patent bypass grafts.

How would you manage Mr. F’s aortic stenosis?

Aortic valve replacement is not considered an option in patients with noncardiac illnesses and comorbidities that are life-limiting in the near term. Under these circumstances, aortic valvuloplasty can be offered as a means of palliating symptoms or, if the comorbid conditions can be modified, as a bridge to more definitive treatment with aortic valve replacement.

Since first described in 1986,45 percutaneous aortic valvuloplasty has been studied in several case series and registries, with consistent findings. Acutely, it increases the valve area and lessens the gradients across the valve, relieving symptoms. The risk of death during the procedure ranged from 3% to 13.5% in several case series, with a 30-day survival rate greater than 85%.46 However, the hemodynamic and symptomatic improvement is only short-term, as valve area and gradients gradually worsen within several months.47,48 Consequently, balloon valvuloplasty is considered a palliative approach.

Mr. F has a potentially life-limiting illness, ie, cancer, which would make him a candidate for aortic valvuloplasty rather than replacement. He can be referred for evaluation for this procedure in hopes of palliating his symptoms by relieving his dyspnea and improving his quality of life.

CASE 7: HEMODYNAMIC INSTABILITY

Mr. G, age 87, is scheduled for surgical aortic valve replacement because of severe aortic stenosis (valve area 0.5 cm2, peak and mean gradients 89 and 45 mm Hg) with an ejection fraction of 30%.

Two weeks before his scheduled surgery he presents to the emergency department with worsening fluid overload and increasing shortness of breath. His initial laboratory work shows new-onset renal failure, and he has signs of hypoperfusion on physical examination. He is transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit for further care.

How would you manage his aortic stenosis?

Patients with decompensated aortic stenosis and hemodynamic instability are at extreme risk during surgery. Medical stabilization beforehand may mitigate the risks associated with surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Aortic valvuloplasty, treatment with sodium nitroprusside, and support with intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation may help stabilize patients in this “low-output” setting.

Sodium nitroprusside has long been used in low-output states. By relaxing vascular smooth muscle, it leads to increased venous capacitance, decreasing preload and congestion. It also decreases systemic vascular resistance with a subsequent decrease in afterload, which in turn improves systolic emptying. Together, these effects reduce systolic and diastolic wall stress, lower myocardial oxygen consumption, and ultimately increase cardiac output.49,50

These theoretical benefits translate to clinical improvement and increased cardiac output, as shown in a case series of 25 patients with severe aortic stenosis and left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction 35%) presenting in a low-output state in the absence of hypotension.51 These findings have led to a ACC/AHA recommendation for the use of sodium nitroprusside in patients who have severe aortic stenosis presenting in low-output state with decompensated heart failure.21

Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation, introduced in 1968, has been used in several clinical settings, including acute coronary syndromes, intractable ventricular arrhythmias, and refractory heart failure, and for support of hemodynamics in the perioperative setting. Its role in managing ventricular septal rupture and acute mitral regurgitation is well established. It reliably reduces afterload and improves coronary perfusion, augmenting the cardiac output. This in turn leads to improved systemic perfusion, which can buy time for a critically ill patient during which the primary disease process is addressed.

Recently, a case series in which intraaortic balloon counterpulsation devices were placed in patients with severe aortic stenosis and cardiogenic shock showed findings similar to those with sodium nitroprusside infusion. Specifically, their use was associated with improved cardiac indices and filling pressures with a decrease in systemic vascular resistance. These changes have led to increased cardiac performance, resulting in better systemic perfusion.52 Thus, intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation can be an option for stabilizing patients with severe aortic stenosis and cardiogenic shock.

Mr. G was treated with sodium nitroprusside and intravenous diuretics. He achieved symptomatic relief and his renal function returned to baseline. He subsequently underwent aortic valve replacement during the hospitalization.

- Carabello BA, Paulus WJ. Aortic stenosis. Lancet 2009; 373:956–966.

- Lindroos M, Kupari M, Heikkilä J, Tilvis R. Prevalence of aortic valve abnormalities in the elderly: an echocardiographic study of a random population sample. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993; 21:1220–1225.

- Otto CM, Pearlman AS, Gardner CL. Hemodynamic progression of aortic stenosis in adults assessed by Doppler echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989; 13:545–550.

- Otto CM, Burwash IG, Legget ME, et al. Prospective study of asymptomatic valvular aortic stenosis. Clinical, echocardiographic, and exercise predictors of outcome. Circulation 1997; 95:2262–2270.

- Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, Pai RG. Clinical profile and natural history of 453 nonsurgically managed patients with severe aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 82:2111–2115.

- Turina J, Hess O, Sepulcri F, Krayenbuehl HP. Spontaneous course of aortic valve disease. Eur Heart J 1987; 8:471–483.

- Horstkotte D, Loogen F. The natural history of aortic valve stenosis. Eur Heart J 1988; 9(suppl E):57–64.

- Novaro GM, Tiong IY, Pearce GL, Lauer MS, Sprecher DL, Griffin BP. Effect of hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitors on the progression of calcific aortic stenosis. Circulation 2001; 104:2205–2209.

- Cowell SJ, Newby DE, Prescott RJ, et al; Scottish Aortic Stenosis and Lipid Lowering Trial, Impact on Regression (SALTIRE) Investigators. A randomized trial of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in calcific aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2389–2397.

- Rossebø AB, Pedersen TR, Boman K, et al; SEAS Investigators. Intensive lipid lowering with simvastatin and ezetimibe in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1343–1356.

- Moura LM, Ramos SF, Zamorano JL, et al. Rosuvastatin affecting aortic valve endothelium to slow the progression of aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:554–561.

- Rosenhek R, Rader F, Loho N, et al. Statins but not angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors delay progression of aortic stenosis. Circulation 2004; 110:1291–1295.

- O’Brien KD, Probstfield JL, Caulked MT, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and change in aortic valve calcium. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:858–862.

- Lindblom D, Lindblom U, Qvist J, Lundström H. Long-term relative survival rates after heart valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990; 15:566–573.

- Makkar RR, Fontana G P, Jilaihawi H, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement for inoperable severe aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1696–1704.

- Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2187–2198.

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:1597–1607.

- Di Eusanio M, Fortuna D, Cristell D, et al; RERIC (Emilia Romagna Cardiac Surgery Registry) Investigators. Contemporary outcomes of conventional aortic valve replacement in 638 octogenarians: insights from an Italian Regional Cardiac Surgery Registry (RERIC). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012; 41:1247–1252.

- Di Eusanio M, Fortuna D, De Palma R, et al. Aortic valve replacement: results and predictors of mortality from a contemporary series of 2256 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011; 141:940–947.

- Jamieson WR, Edwards FH, Schwartz M, Bero JW, Clark RE, Grover FL. Risk stratification for cardiac valve replacement. National Cardiac Surgery Database. Database Committee of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg 1999; 67:943–951.

- Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2008 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease). Endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52:e1–e142.

- Hachicha Z, Dumesnil JG, Bogaty P, Pibarot P. Paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis despite preserved ejection fraction is associated with higher afterload and reduced survival. Circulation 2007; 115:2856–2864.

- Vaquette B, Corbineau H, Laurent M, et al. Valve replacement in patients with critical aortic stenosis and depressed left ventricular function: predictors of operative risk, left ventricular function recovery, and long term outcome. Heart 2005; 91:1324–1329.

- Connolly HM, Oh JK, Orszulak TA, et al. Aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Prognostic indicators. Circulation 1997; 95:2395–2400.

- Connolly HM, Oh JK, Schaff HV, et al. Severe aortic stenosis with low transvalvular gradient and severe left ventricular dysfunction: result of aortic valve replacement in 52 patients. Circulation 2000; 101:1940–1946.

- Pereira JJ, Lauer MS, Bashir M, et al. Survival after aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis with low transvalvular gradients and severe left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:1356–1363.

- Pai RG, Varadarajan P, Razzouk A. Survival benefit of aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis with low ejection fraction and low gradient with normal ejection fraction. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 86:1781–1789.

- Monin JL, Monchi M, Gest V, Duval-Moulin AM, Dubois-Rande JL, Gueret P. Aortic stenosis with severe left ventricular dysfunction and low transvalvular pressure gradients: risk stratification by low-dose dobutamine echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 37:2101–2107.

- Monin JL, Quéré J P, Monchi M, et al. Low-gradient aortic stenosis: operative risk stratification and predictors for long-term outcome: a multicenter study using dobutamine stress hemodynamics. Circulation 2003; 108:319–324.

- Zuppiroli A, Mori F, Olivotto I, Castelli G, Favilli S, Dolara A. Therapeutic implications of contractile reserve elicited by dobutamine echocardiography in symptomatic, low-gradient aortic stenosis. Ital Heart J 2003; 4:264–270.

- Tribouilloy C, Lévy F, Rusinaru D, et al. Outcome after aortic valve replacement for low-flow/low-gradient aortic stenosis without contractile reserve on dobutamine stress echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:1865–1873.

- Ahmed AA, Graham AN, Lovell D, O’Kane HO. Management of mild to moderate aortic valve disease during coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2003; 24:535–539.

- Verhoye J P, Merlicco F, Sami IM, et al. Aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis after previous coronary artery bypass grafting: could early reoperation be prevented? J Heart Valve Dis 2006; 15:474–478.

- Hochrein J, Lucke JC, Harrison JK, et al. Mortality and need for reoperation in patients with mild-to-moderate asymptomatic aortic valve disease undergoing coronary artery bypass graft alone. Am Heart J 1999; 138:791–797.

- Pereira JJ, Balaban K, Lauer MS, Lytle B, Thomas JD, Garcia MJ. Aortic valve replacement in patients with mild or moderate aortic stenosis and coronary bypass surgery. Am J Med 2005; 118:735–742.

- Amato MC, Moffa PJ, Werner KE, Ramires JA. Treatment decision in asymptomatic aortic valve stenosis: role of exercise testing. Heart 2001; 86:381–386.

- Das P, Rimington H, Chambers J. Exercise testing to stratify risk in aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J 2005; 26:1309–1313.

- Weber M, Arnold R, Rau M, et al. Relation of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide to severity of valvular aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 2004; 94:740–745.

- Weber M, Hausen M, Arnold R, et al. Prognostic value of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide for conservatively and surgically treated patients with aortic valve stenosis. Heart 2006; 92:1639–1644.

- Gerber IL, Stewart RA, Legget ME, et al. Increased plasma natriuretic peptide levels refect symptom onset in aortic stenosis. Circulation 2003; 107:1884–1890.

- Bergler-Klein J, Klaar U, Heger M, et al. Natriuretic peptides predict symptom-free survival and postoperative outcome in severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2004; 109:2302–2308.

- Lancellotti P, Moonen M, Magne J, et al. Prognostic effect of long-axis left ventricular dysfunction and B-type natriuretic peptide levels in asymptomatic aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 2010; 105:383–388.

- Langanay T, Flécher E, Fouquet O, et al. Aortic valve replacement in the elderly: the real life. Ann Thorac Surg 2012; 93:70–77.

- Christofferson RD, Kapadia SR, Rajagopal V, Tuzcu EM. Emerging transcatheter therapies for aortic and mitral disease. Heart 2009; 95:148–155.

- Cribier A, Savin T, Saoudi N, Rocha P, Berland J, Letac B. Percutaneous transluminal valvuloplasty of acquired aortic stenosis in elderly patients: an alternative to valve replacement? Lancet 1986; 1:63–67.

- Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Acute and 30-day follow-up results in 674 patients from the NHLBI Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry. Circulation 1991; 84:2383–2397.

- Otto CM, Mickel MC, Kennedy JW, et al. Three-year outcome after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Insights into prognosis of valvular aortic stenosis. Circulation 1994; 89:642–650.

- Bernard Y, Etievent J, Mourand JL, et al. Long-term results of percutaneous aortic valvuloplasty compared with aortic valve replacement in patients more than 75 years old. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 20:796–801.

- Elkayam U, Janmohamed M, Habib M, Hatamizadeh P. Vasodilators in the management of acute heart failure. Crit Care Med 2008; 36(suppl 1):S95–S105.

- Popovic ZB, Khot UN, Novaro GM, et al. Effects of sodium nitroprusside in aortic stenosis associated with severe heart failure: pressure-volume loop analysis using a numerical model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005; 288:H416–H423.

- Khot UN, Novaro GM, Popovic ZB, et al. Nitroprusside in critically ill patients with left ventricular dysfunction and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:1756–1763.

- Aksoy O, Yousefzai R, Singh D, et al. Cardiogenic shock in the setting of severe aortic stenosis: role of intra-aortic balloon pump support. Heart 2011; 97:838–843.

Surgical aortic valve replacement remains the gold standard treatment for symptomatic aortic valve stenosis in patients at low or moderate risk of surgical complications. But this is a disease of the elderly, many of whom are too frail or too sick to undergo surgery.

Now, patients who cannot undergo this surgery can be offered the less invasive option of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Balloon valvuloplasty, sodium nitroprusside, and intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation can buy time for ill patients while more permanent mechanical interventions are being considered.

In this review, we will present several cases that highlight management choices for patients with severe aortic stenosis.

A PROGRESSIVE DISEASE OF THE ELDERLY

Aortic stenosis is the most common acquired valvular disease in the United States, and its incidence and prevalence are rising as the population ages. Epidemiologic studies suggest that 2% to 7% of all patients over age 65 have it.1,2

The natural history of the untreated disease is well established, with several case series showing an average decrease of 0.1 cm2 per year in aortic valve area and an increase of 7 mm Hg per year in the pressure gradient across the valve once the diagnosis is made.3,4 Development of angina, syncope, or heart failure is associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including death, and warrants prompt intervention with aortic valve replacement.5–7 Without intervention, the mortality rates reach as high as 75% in 3 years once symptoms develop.

Statins, bisphosphonates, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have been used in attempts to slow or reverse the progression of aortic stenosis. However, studies of these drugs have had mixed results, and no definitive benefit has been shown.8–13 Surgical aortic valve replacement, on the other hand, normalizes the life expectancy of patients with aortic stenosis to that of age- and sex-matched controls and remains the gold standard therapy for patients who have symptoms.14

Traditionally, valve replacement has involved open heart surgery, since it requires direct visualization of the valve while the patient is on cardiopulmonary bypass. Unfortunately, many patients have multiple comorbid conditions and therefore are not candidates for open heart surgery. Options for these patients include aortic valvuloplasty and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. While there is considerable experience with aortic valvuloplasty, transcatheter aortic valve replacement is relatively new. In large randomized trials and registries, the transcatheter procedure has been shown to significantly improve long-term survival compared with medical management alone in inoperable patients and to have benefit similar to that of surgery in the high-risk population.15–17

CASE 1: SEVERE, SYMPTOMATIC STENOSIS IN A GOOD SURGICAL CANDIDATE

Mr. A, age 83, presents with shortness of breath and peripheral edema that have been worsening over the past several months. His pulse rate is 64 beats per minute and his blood pressure is 110/90 mm Hg. Auscultation reveals an absent aortic second heart sound with a late peaking systolic murmur that increases with expiration.

On echocardiography, his left ventricular ejection fraction is 55%, peak transaortic valve gradient 88 mm Hg, mean gradient 60 mm Hg, and effective valve area 0.6 cm2. He undergoes catheterization of the left side of his heart, which shows normal coronary arteries.

Mr. A also has hypertension and hyperlipidemia; his renal and pulmonary functions are normal.

How would you manage Mr. A’s aortic stenosis?

Symptomatic aortic stenosis leads to adverse clinical outcomes if managed medically without mechanical intervention,5–7 but patients who undergo aortic valve replacement have age-corrected postoperative survival rates that are nearly normal.14 Furthermore, thanks to improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative management, surgical mortality rates have decreased significantly in recent years and now range from 1% to 8%.18–20 The accumulated evidence showing clear superiority of a surgical approach over medical therapy has greatly simplified the therapeutic algorithm.21

Consequently, the current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) give surgery a class I indication (evidence or general agreement that the procedure is beneficial, useful, and effective) for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (Figure 1). This level of recommendation also applies to patients who have severe but asymptomatic aortic stenosis who are undergoing other types of cardiac surgery and also to patients with severe aortic stenosis and left ventricular dysfunction (defined as an ejection fraction < 50%).21

Mr. A was referred for surgical aortic valve replacement, given its clear survival benefit.

CASE 2: SYMPTOMS AND LEFT VENTRICULAR DYSFUNCTION

Ms. B, age 79, has hypertension and hyperlipidemia and now presents to the outpatient department with worsening shortness of breath and chest discomfort. Electrocardiography shows significant left ventricular hypertrophy and abnormal repolarization. Left heart catheterization reveals mild nonobstructive coronary artery disease.

Echocardiography reveals an ejection fraction of 25%, severe left ventricular hypertrophy, and global hypokinesis. The aortic valve leaflets appear heavily calcified, with restricted motion. The peak and mean gradients across the aortic valve are 40 and 28 mm Hg, and the valve area is 0.8 cm2. Right heart catheterization shows a cardiac output of 3.1 L/min.

Does this patient’s aortic stenosis account for her clinical presentation?

Managing patients who have suspected severe aortic stenosis, left ventricular dysfunction, and low aortic valve gradients can be challenging. Although data for surgical intervention are not as robust for these patient subsets as for patients like Mr. A, several case series have suggested that survival in these patients is significantly better with surgery than with medical therapy alone.22–27

Specific factors predict whether patients with ventricular dysfunction and low gradients will benefit from aortic valve replacement. Dobutamine stress echocardiography is helpful in distinguishing true severe aortic stenosis from “pseudostenosis,” in which leaflet motion is restricted due to primary cardiomyopathy and low flow. Distinguishing between true aortic stenosis and pseudostenosis is of paramount value, as surgery is associated with improved long-term outcomes in patients with true aortic stenosis (even though they are at higher surgical risk), whereas those with pseudostenosis will not benefit from surgery.28–31

Infusion of dobutamine increases the flow across the aortic valve (if the left ventricle has contractile reserve; more on this below), and an increasing valve area with increasing doses of dobutamine is consistent with pseudostenosis. In this situation, treatment of the underlying cardiomyopathy is indicated as opposed to replacement of the aortic valve (Figure 2).

Contractile reserve is defined as an increase in stroke volume (> 20%), valvular gradient (> 10 mm Hg), or peak velocity (> 0.6 m/s) with peak dobutamine infusion. The presence of contractile reserve in patients with aortic stenosis identifies a high-risk group that benefits from aortic valve replacement (Figure 2).

Treatment of patients who have inadequate reserve is controversial. In the absence of contractile reserve, an adjunct imaging study such as computed tomography may be of value in detecting calcified valve leaflets, as the presence of calcium is associated with true aortic stenosis. Comorbid conditions should be taken into account as well, given the higher surgical risk in this patient subset, as aortic valve replacement in this already high-risk group of patients might be futile in some cases.

The ACC/AHA guidelines now give dobutamine stress echocardiography a class IIa indication (meaning the weight of the evidence or opinion is in favor of usefulness or efficacy) for determination of contractile reserve and valvular stenosis for patients with an ejection fraction of 30% or less or a mean gradient of 40 mm Hg or less.21

Ms. B underwent dobutamine stress echocardiography. It showed increases in ejection fraction, stroke volume, and transvalvular gradients, indicating that she did have contractile reserve and true severe aortic stenosis. Consequently, she was referred for surgical aortic valve replacement.

CASE 3: MODERATE STENOSIS AND THREE-VESSEL CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Mr. C, age 81, has hypertension and hyperlipidemia. He now presents to the emergency department with chest discomfort that began suddenly, awakening him from sleep. His presenting electrocardiogram shows nonspecific changes, and he is diagnosed with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. He undergoes left heart catheterization, which reveals severe three-vessel coronary artery disease.

Echocardiography reveals an ejection fraction of 55% and aortic stenosis, with an aortic valve area of 1.2 cm2, a peak gradient of 44 mm Hg, and a mean gradient of 28 mm Hg.

How would you manage his aortic stenosis?

Moderate aortic stenosis in a patient who needs surgery for severe triple-vessel coronary artery disease, other valve diseases, or aortic disease raises the question of whether aortic valve replacement should be performed in conjunction with these surgeries. Although these patients would not otherwise qualify for aortic valve replacement, the fact that they will undergo a procedure that will expose them to the risks associated with open heart surgery makes them reasonable candidates. Even if the patient does not need aortic valve replacement right now, aortic stenosis progresses at a predictable rate—the valve area decreases by a mean of 0.1 cm2/year and the gradients increase by 7 mm Hg/year. Therefore, clinical judgment should be exercised so that the patient will not need to undergo open heart surgery again in the near future.

The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend aortic valve replacement for patients with moderate aortic stenosis undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting or surgery on the aorta or other heart valves, giving it a class IIa indication.21 This recommendation is based on several retrospective case series that evaluated survival, the need for reoperation for aortic valve replacement, or both in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting.32–35

No data exist, however, on adding aortic valve replacement to coronary artery bypass grafting in cases of mild aortic stenosis. As a result, it is controversial and carries a class IIb recommendation (meaning that its usefulness or efficacy is less well established). The ACC/AHA guidelines state that aortic valve replacement “may be considered” in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting who have mild aortic stenosis (mean gradient < 30 mm Hg or jet velocity < 3 m/s) when there is evidence, such as moderate or severe valve calcification, that progression may be rapid (level of evidence C: based only on consensus opinion of experts, case studies or standard of care).21

Mr. C, who has moderate aortic stenosis, underwent aortic valve replacement in conjunction with three-vessel bypass grafting.

CASE 4: ASYMPTOMATIC BUT SEVERE STENOSIS

Mr. D, age 74, has hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and aortic stenosis. He now presents to the outpatient department for his annual echocardiogram to follow his aortic stenosis. He has a sedentary lifestyle but feels well performing activities of daily living. He denies dyspnea on exertion, chest pain, or syncope.

His echocardiogram reveals an effective aortic valve area of 0.7 cm2, peak gradient 90 mm Hg, and mean gradient 70 mm Hg. There is evidence of severe left ventricular hypertrophy, and the valve leaflets show bulky calcification and severe restriction. An echocardiogram performed at the same institution a year earlier revealed gradients of 60 and 40 mm Hg.

Blood is drawn for laboratory tests, including N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, which is 350 pg/mL (reference range for his age < 125 pg/mL). He is referred for a treadmill stress test, which elicits symptoms at a moderate activity level.

How would you manage his aortic stenosis?

Aortic valve replacement can be considered in patients who have asymptomatic but severe aortic stenosis with preserved left ventricular function (class IIb indication).21