User login

Residents' ECG Interpretation Skills

Decreased efficiency at the beginning of residency training likely results in preventable harm for patients, a phenomenon known as the July Effect.[1, 2] Postgraduate year (PGY)1 residents enter training with a variety of clinical skills and experiences, and concerns exist regarding their preparation to enter graduate medical education (GME).[3] Electrocardiogram (ECG) interpretation is a core clinical skill that residents must have on the first day of training to manage patients, recognize emergencies, and develop evidence‐based and cost‐effective treatment plans. We assessed incoming PGY‐1 residents' ability to interpret common ECG findings as part of a rigorous boot camp experience.[4]

METHODS

This was an institutional review board‐approved pre‐post study of 81 new PGY‐1 residents' ECG interpretation skills. Subjects represented all trainees from internal medicine (n=47), emergency medicine (n=13), anesthesiology (n=11), and general surgery (n=10), who entered GME at Northwestern University in June 2013. Residents completed a pretest, followed by a 60‐minute interactive small group tutorial and a post‐test. Program faculty and expert cardiologists selected 10 common ECG findings for the study, many representing medical emergencies requiring immediate treatment. The diagnoses were: normal sinus rhythm, hyperkalemia, right bundle branch block (RBBB), left bundle branch block (LBBB), complete heart block, lateral wall myocardial infarction (MI), anterior wall MI, atrial fibrillation, ventricular paced rhythm, and ventricular tachycardia (VT). ECGs were selected from an online reference set (

RESULTS

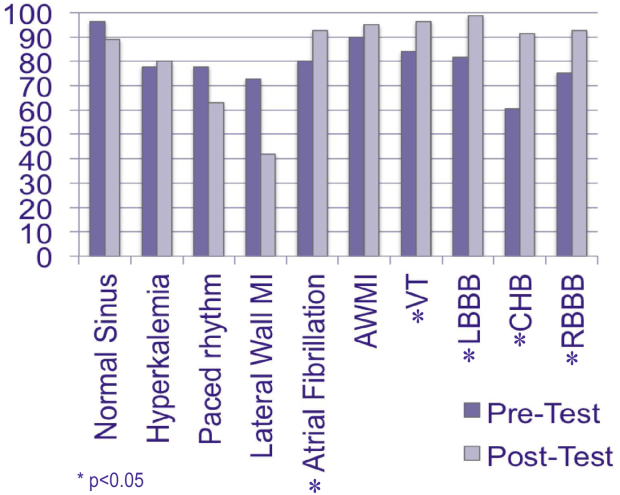

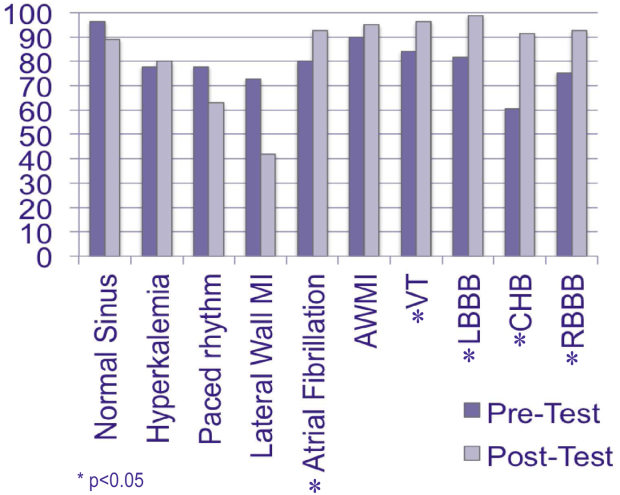

All 81 residents completed the study. The mean age was 27 years, and 56% were male. Eighty (99%) graduated from a US medical school. The mean United States Medical Licensing Examination scores were step 1: 243.8 (14.4) and step 2: 251.8 (13.6). Twenty‐six (32%) completed a cardiology rotation in medical school. Before the pretest, residents self‐assessed their ECG interpretation skills as a mean of 61.8 (standard deviation 17.2) using a scale of 0 (not confident) to 100 (very confident). Pretest results ranged from 60.5% correct (complete heart block) to 96.3% correct (normal sinus rhythm). Eighteen residents (22%) did not recognize hyperkalemia, 20 (25%) were unable to identify RBBB, and 15 (18%) LBBB. Twenty‐two (27%) could not discern a lateral wall MI, and 8 residents (10%) missed an anterior wall MI. Sixteen (20%) could not diagnose atrial fibrillation, 18 (22%) could not identify a ventricular paced rhythm, and 13 (16%) did not recognize VT. Mean post‐test scores improved significantly for 5 cases (P0.05), but did not rise significantly for normal sinus rhythm, lateral wall MI, anterior wall MI, hyperkalemia, and ventricular paced rhythm 1.

DISCUSSION

PGY‐1 residents from multiple specialties were not confident regarding their ability to interpret ECGs and could not reliably identify 10 basic findings. This is despite graduating almost exclusively from US medical schools and performing at high levels on standardized tests. Although boot camp improved recognition of important ECG findings, including VT and bundle branch blocks, identification of emergent diagnoses such as lateral/anterior MI and hyperkalemia require additional training and close supervision during patient care. This study provides further evidence that the preparation of PGY‐1 residents to enter GME is lacking. Recent calls for inclusion of cost‐consciousness and stewardship of resources as a seventh competency for residents[5] are challenging, because incoming trainees do not uniformly possess the basic clinical skills needed to make these judgments.[3, 4] If residents cannot reliably interpret ECGs, it is not possible to determine cost‐effective testing strategies for patients with cardiac conditions. Based on the result of this study and others,[3, 4] we believe medical schools should agree upon specific graduation requirements to ensure all students have mastered core competencies and are prepared to enter GME.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , . The July effect: fertile ground for systems improvement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):331–332.

- , , , , , . July effect: impact of the academic year‐end changeover on patient outcomes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):309–315.

- , , , . Assessing residents' competencies at baseline: identifying the gaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):564–570.

- , , , et al. Making July safer: simulation‐based mastery learning during intern boot camp. Acad Med. 2013;88(2):233–239.

- . Providing high‐value, cost‐conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386–388.

Decreased efficiency at the beginning of residency training likely results in preventable harm for patients, a phenomenon known as the July Effect.[1, 2] Postgraduate year (PGY)1 residents enter training with a variety of clinical skills and experiences, and concerns exist regarding their preparation to enter graduate medical education (GME).[3] Electrocardiogram (ECG) interpretation is a core clinical skill that residents must have on the first day of training to manage patients, recognize emergencies, and develop evidence‐based and cost‐effective treatment plans. We assessed incoming PGY‐1 residents' ability to interpret common ECG findings as part of a rigorous boot camp experience.[4]

METHODS

This was an institutional review board‐approved pre‐post study of 81 new PGY‐1 residents' ECG interpretation skills. Subjects represented all trainees from internal medicine (n=47), emergency medicine (n=13), anesthesiology (n=11), and general surgery (n=10), who entered GME at Northwestern University in June 2013. Residents completed a pretest, followed by a 60‐minute interactive small group tutorial and a post‐test. Program faculty and expert cardiologists selected 10 common ECG findings for the study, many representing medical emergencies requiring immediate treatment. The diagnoses were: normal sinus rhythm, hyperkalemia, right bundle branch block (RBBB), left bundle branch block (LBBB), complete heart block, lateral wall myocardial infarction (MI), anterior wall MI, atrial fibrillation, ventricular paced rhythm, and ventricular tachycardia (VT). ECGs were selected from an online reference set (

RESULTS

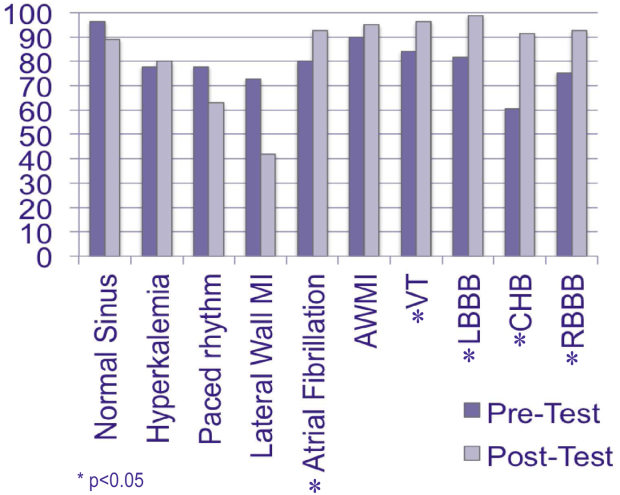

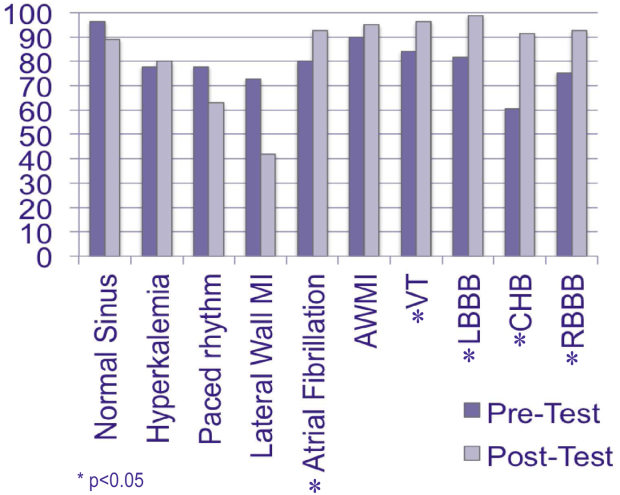

All 81 residents completed the study. The mean age was 27 years, and 56% were male. Eighty (99%) graduated from a US medical school. The mean United States Medical Licensing Examination scores were step 1: 243.8 (14.4) and step 2: 251.8 (13.6). Twenty‐six (32%) completed a cardiology rotation in medical school. Before the pretest, residents self‐assessed their ECG interpretation skills as a mean of 61.8 (standard deviation 17.2) using a scale of 0 (not confident) to 100 (very confident). Pretest results ranged from 60.5% correct (complete heart block) to 96.3% correct (normal sinus rhythm). Eighteen residents (22%) did not recognize hyperkalemia, 20 (25%) were unable to identify RBBB, and 15 (18%) LBBB. Twenty‐two (27%) could not discern a lateral wall MI, and 8 residents (10%) missed an anterior wall MI. Sixteen (20%) could not diagnose atrial fibrillation, 18 (22%) could not identify a ventricular paced rhythm, and 13 (16%) did not recognize VT. Mean post‐test scores improved significantly for 5 cases (P0.05), but did not rise significantly for normal sinus rhythm, lateral wall MI, anterior wall MI, hyperkalemia, and ventricular paced rhythm 1.

DISCUSSION

PGY‐1 residents from multiple specialties were not confident regarding their ability to interpret ECGs and could not reliably identify 10 basic findings. This is despite graduating almost exclusively from US medical schools and performing at high levels on standardized tests. Although boot camp improved recognition of important ECG findings, including VT and bundle branch blocks, identification of emergent diagnoses such as lateral/anterior MI and hyperkalemia require additional training and close supervision during patient care. This study provides further evidence that the preparation of PGY‐1 residents to enter GME is lacking. Recent calls for inclusion of cost‐consciousness and stewardship of resources as a seventh competency for residents[5] are challenging, because incoming trainees do not uniformly possess the basic clinical skills needed to make these judgments.[3, 4] If residents cannot reliably interpret ECGs, it is not possible to determine cost‐effective testing strategies for patients with cardiac conditions. Based on the result of this study and others,[3, 4] we believe medical schools should agree upon specific graduation requirements to ensure all students have mastered core competencies and are prepared to enter GME.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

Decreased efficiency at the beginning of residency training likely results in preventable harm for patients, a phenomenon known as the July Effect.[1, 2] Postgraduate year (PGY)1 residents enter training with a variety of clinical skills and experiences, and concerns exist regarding their preparation to enter graduate medical education (GME).[3] Electrocardiogram (ECG) interpretation is a core clinical skill that residents must have on the first day of training to manage patients, recognize emergencies, and develop evidence‐based and cost‐effective treatment plans. We assessed incoming PGY‐1 residents' ability to interpret common ECG findings as part of a rigorous boot camp experience.[4]

METHODS

This was an institutional review board‐approved pre‐post study of 81 new PGY‐1 residents' ECG interpretation skills. Subjects represented all trainees from internal medicine (n=47), emergency medicine (n=13), anesthesiology (n=11), and general surgery (n=10), who entered GME at Northwestern University in June 2013. Residents completed a pretest, followed by a 60‐minute interactive small group tutorial and a post‐test. Program faculty and expert cardiologists selected 10 common ECG findings for the study, many representing medical emergencies requiring immediate treatment. The diagnoses were: normal sinus rhythm, hyperkalemia, right bundle branch block (RBBB), left bundle branch block (LBBB), complete heart block, lateral wall myocardial infarction (MI), anterior wall MI, atrial fibrillation, ventricular paced rhythm, and ventricular tachycardia (VT). ECGs were selected from an online reference set (

RESULTS

All 81 residents completed the study. The mean age was 27 years, and 56% were male. Eighty (99%) graduated from a US medical school. The mean United States Medical Licensing Examination scores were step 1: 243.8 (14.4) and step 2: 251.8 (13.6). Twenty‐six (32%) completed a cardiology rotation in medical school. Before the pretest, residents self‐assessed their ECG interpretation skills as a mean of 61.8 (standard deviation 17.2) using a scale of 0 (not confident) to 100 (very confident). Pretest results ranged from 60.5% correct (complete heart block) to 96.3% correct (normal sinus rhythm). Eighteen residents (22%) did not recognize hyperkalemia, 20 (25%) were unable to identify RBBB, and 15 (18%) LBBB. Twenty‐two (27%) could not discern a lateral wall MI, and 8 residents (10%) missed an anterior wall MI. Sixteen (20%) could not diagnose atrial fibrillation, 18 (22%) could not identify a ventricular paced rhythm, and 13 (16%) did not recognize VT. Mean post‐test scores improved significantly for 5 cases (P0.05), but did not rise significantly for normal sinus rhythm, lateral wall MI, anterior wall MI, hyperkalemia, and ventricular paced rhythm 1.

DISCUSSION

PGY‐1 residents from multiple specialties were not confident regarding their ability to interpret ECGs and could not reliably identify 10 basic findings. This is despite graduating almost exclusively from US medical schools and performing at high levels on standardized tests. Although boot camp improved recognition of important ECG findings, including VT and bundle branch blocks, identification of emergent diagnoses such as lateral/anterior MI and hyperkalemia require additional training and close supervision during patient care. This study provides further evidence that the preparation of PGY‐1 residents to enter GME is lacking. Recent calls for inclusion of cost‐consciousness and stewardship of resources as a seventh competency for residents[5] are challenging, because incoming trainees do not uniformly possess the basic clinical skills needed to make these judgments.[3, 4] If residents cannot reliably interpret ECGs, it is not possible to determine cost‐effective testing strategies for patients with cardiac conditions. Based on the result of this study and others,[3, 4] we believe medical schools should agree upon specific graduation requirements to ensure all students have mastered core competencies and are prepared to enter GME.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , . The July effect: fertile ground for systems improvement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):331–332.

- , , , , , . July effect: impact of the academic year‐end changeover on patient outcomes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):309–315.

- , , , . Assessing residents' competencies at baseline: identifying the gaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):564–570.

- , , , et al. Making July safer: simulation‐based mastery learning during intern boot camp. Acad Med. 2013;88(2):233–239.

- . Providing high‐value, cost‐conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386–388.

- , . The July effect: fertile ground for systems improvement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):331–332.

- , , , , , . July effect: impact of the academic year‐end changeover on patient outcomes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):309–315.

- , , , . Assessing residents' competencies at baseline: identifying the gaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):564–570.

- , , , et al. Making July safer: simulation‐based mastery learning during intern boot camp. Acad Med. 2013;88(2):233–239.

- . Providing high‐value, cost‐conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386–388.

Entrusting Residents with Tasks

Determining when residents are independently prepared to perform clinical care tasks safely is not easy or understood. Educators have struggled to identify robust ways to evaluate trainees and their preparedness to treat patients while unsupervised. Trust allows the trainee to experience increasing levels of participation and responsibility in the workplace in a way that builds competence for future practice. The breadth of knowledge and skills required to become a competent and safe physician, coupled with the busy workload confound this challenge. Notably, a technically proficient trainee may not have the clinical judgment to treat patients without supervision.

The Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has previously outlined 6 core competencies for residency training: patient care, medical knowledge, practice‐based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems‐based practice.[1] A systematic literature review suggests that traditional trainee evaluation tools are difficult to use and unreliable in measuring the competencies independently from one another, whereas certain competencies are consistently difficult to quantify in a reliable and valid way.[2] The evaluation of trainees' clinical performance despite efforts to create objective tools remain strongly influenced by subjective measures and continues to be highly variable among different evaluators.[3] Objectively measuring resident autonomy and readiness to supervise junior colleagues remains imprecise.[4]

The ACGME's Next Accreditation System (NAS) incorporates educational milestones as part of the reporting of resident training outcomes.[5] The milestones allow for the translation of the core competencies into integrative and observable abilities. Furthermore, the milestone categories are stratified into tiers to allow progress to be measured longitudinally and by task complexity using a novel assessment strategy.

The development of trust between supervisors and trainees is a critical step in decisions to allow increased responsibility and the provision of autonomous decision making, which is an important aspect of physician training. Identifying the factors that influence the supervisors' evaluation of resident competency and capability is at the crux of trainee maturation as well as patient safety.[4] Trust, defined as believability and discernment by attendings of resident physicians, plays a large role in attending evaluations of residents during their clinical rotations.[3] Trust impacts the decisions of successful performance of entrustable professional activities (EPAs), or those tasks that require mastery prior to completion of training milestones.[6] A study of entrustment decisions made by attending anesthesiologists identified the factors that contribute to the amount of autonomy given to residents, such as trainee trustworthiness, medical knowledge, and level of training.[4] The aim of our study, building on this study, was 2‐fold: (1) use deductive qualitative analysis to apply this framework to existing resident and attending data, and (2) define the categories within this framework and describe how internal medicine attending and resident physician perceptions of trust can impact clinical decision making and patient care.

METHODS

We are reporting on a secondary data analysis of interview transcripts from a study conducted on the inpatient general medicine service at the University of Chicago, an academic tertiary care medical center. The methods for data collection and full consent have been outlined previously.[7, 8, 9] The institutional review board of the University of Chicago approved this study.

Briefly, between January 2006 and November 2006, all eligible internal medicine resident physicians, postgraduate year (PGY)‐2 or PGY‐3, and attending physicians, either generalists or hospitalists, were privately interviewed within 1 week of their final call night on the inpatient general medicine rotation to assess decision making and clinical supervision during the rotation. All interviews were conducted by 1 investigator (J.F.), and discussions were audio taped and transcribed for analysis. Interviews were conducted at the conclusion of the rotation to prevent any influence on resident and attending behavior during the rotation.

The critical incident technique, a procedure used for collecting direct observations of human behavior that have critical significance on the decision‐making process, was used to solicit examples of ineffective supervision, inquiring about 2 to 3 important clinical decisions made on the most recent call night, with probes to identify issues of trust, autonomy, and decision making.[10] A critical incident can be described as one that makes a significant contribution, either positively or negatively, on the process.

Appreciative inquiry, a technique that aims to uncover the best things about the clinical encounter being explored, was used to solicit examples of effective supervision. Probes are used to identify factors, either personal or situational, that influenced the withholding or provision of resident autonomy during periods of clinical care delivery.[11]

All identifiable information was removed from the interview transcripts to protect participant and patient confidentiality. Deductive qualitative analysis was performed using the conceptual EPA framework, which describes several factors that influence the attending physicians' decisions to deem a resident trustworthy to independently fulfill a specific clinical task.[4] These factors include (1) the nature of the task, (2) the qualities of the supervisor, (3) the qualities of the trainee and the quality of the relationship between the supervisor and the trainee, and (4) the circumstances surrounding the clinical task.

The deidentified, anonymous transcripts were reviewed by 2 investigators (K.J.C., J.M.F.) and analyzed using the constant comparative methods to deductively map the content to the existing framework and generate novel sub themes.[12, 13, 14] Novel categories within each of the domains were inductively generated. Two reviewers (K.J.C., J.M.F.) independently applied the themes to a randomly selected 10% portion of the interview transcripts to assess the inter‐rater reliability. The inter‐rater agreement was assessed using the generalized kappa statistic. The discrepancies between reviewers regarding assignment of codes were resolved via discussion and third party adjudication until consensus was achieved on thematic structure. The codes were then applied to the entire dataset.

RESULTS

Between January 2006 and November 2006, 46 of 50 (88%) attending physicians and 44 of 50 (92%) resident physicians were interviewed following the conclusion of their general medicine inpatient rotation. Of attending physicians, 55% were male, 45% were female, and 38% were academic faculty hospitalists. Of the residents who completed interviews, 47% were male, 53% were female, 52% were PGY‐2, and 45% were PGY‐3.

A total of 535 mentions of trust were abstracted from the transcripts. The 4 major domains that influence trusttrainee factors (Table 1), supervisor factors (Table 2), task factors (Table 3), and systems factors (Table 4)were deductively coded with several emerging novel categories and subthemes. The domains were consistent across the postgraduate year of trainee. No differences in themes were noted, other than those explicitly stated, between the postgraduate years.

| Domain (N) | Category (N) | Subtheme (N) | Definition and Representative Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Trainee factors (170); characteristics specific to the trainee that either promote or discourage trust. | Personal characteristics (78); traits that impact attendings' decision regarding trust/allowance of autonomy. | Confidence and overconfidence (29) | Displayed level of comfort when approaching specific clinical situations. I think I havea personality and presenting style [that] people think that I know what I am talkingabout and they just let me run with it. (R) |

| Accountability (18) | Sense of responsibility, including ability to follow‐up on details regarding patient care. [What] bothered me the most was that that kind of lack of accountability for patient careand it makes the whole dynamic of rounds much more stressful. I ended up asking him to page me every day to run the list. (A) | ||

| Familiarity/ reputation (18) | Comfort with trainee gained through prior working experience, or reputation of the trainee based on discussion with other supervisors. I do have to get to know someone a little to develop that level of trust, to know that it is okay to not check the labs every day, okay to not talk to them every afternoon. (A) | ||

| Honesty (13) | Sense trainee is not withholding information in order to impact decision making toward a specific outcome. [The residents] have more information than I do and they can clearly spin that information, and it is very difficult to unravelunless you treat them like a hostile witness on the stand.(A) | ||

| Clinical attributes (92); skills demonstrated in the context of patient care that promote or inhibit trust. | Leadership (19) | Ability to organize, teach, and manage coresidents, interns, and students. I want them to be in chargedeciding the plan and sitting down with the team before rounds. (A) | |

| Communication (12) | Establishing and encouraging conversation with supervisor regarding decision making.Some residents call me regularly and let me know what's going on and others don't, and those who don't I really have trouble withif you're not calling to check in, then I don't trust your judgment. (A) | ||

| Specialty (6) | Trainee future career plans. Whether it's right or wrong, nonmedicine interns may not be as attentive to smaller details, and so I had to be attentive to smaller details on [his] patients. (R2) | ||

| Medical knowledge (39) | Ability to display appropriate level of clinical acumen and apply evidence‐based medicine. I definitelygo on my own gestalt of talking with them and deciding if what they do is reasonable. If they can't explain things to me, that's when I worry. (A) | ||

| Recognition of limitations (16) | Trainee's ability to recognize his/her own weaknesses, accept criticism, and solicit help when appropriate. The first thing is that they know their limits and ask for help either in rounds or outside of rounds. That indicates to me that as they are out there on their own they are less likely to do things that they don't understand. (A) | ||

| Domain (N) | Major Category (N) | Subtheme (N) | Definition and Representative Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Supervisor factors (120); characteristics specific to the supervisor which either promote or discourage trust. | Approachability (34); personality traits, such as approachability, which impact the trainees' perception regarding trust/allowance of autonomy. | Sense that the attending physician is available to and receptive to questions from trainees. I think [attending physicians] being approachable and available to you if you need them is really helpful. (R) | |

| Clinical attributes (86); skills demonstrated in the context of patient care that promote or inhibit trust. | Institutional obligation (17) | Attending physician is the one contractually and legally responsible for the provision of high‐quality and appropriate patient care. If [the residents] have a good reason I can be argued out of my position. I am ultimately responsible andhave to choose if there is some serious dispute. (A) | |

| Experience and expertise (29) | Clinical experience, area of specialty, and research interests of the attending physician. You have to be confident in your own clinical skills and knowledge, confident enough that you can say its okay for me to let go a little bit. (A) | ||

| Observation‐based evaluation (27) | Evaluation of trainee decision‐making ability during the early part of the attending/trainee relationship. It's usually the first post‐call day experience, the first on‐call and post‐call day experience. One of the big things is [if they can] tell if a patient is sick or not sickif they are missing at that level then I get very nervous. I really get a sense [of] how they think about patients. (A) | ||

| Educational obligation (13) | Acknowledging the role of the attending as clinical teacher. My theory with the interns was that they should do it because that's how you learn. (R) | ||

| Domain (N) | Major Category (N) | Subtheme (N) | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Task factors (146); details or characteristics of the task that encouraged or impeded contacting the supervisor. | Clinical characteristics (103) | Case complexity (25) | Evaluation of the level of difficulty in patient management. I don't expect to be always looking over [the resident's] shoulder, I don't check labs everyday, and I don't call them if I see potassium of 3; I assume that they are going to take care of it. |

| Family/ethical dilemma (10) | Uncertainty regarding respecting the wishes of patients and other ethical dilemmas. There was 1 time I called because we had a very sick patient who had a lot of family asking for more aggressive measures, and I called to be a part of the conversation. | ||

| Interdepartment collaboration (18) | Difficulties when treating patients managed by multiple consult services. I have called [the attending] when I have had trouble pushing things through the systemif we had trouble getting tests or trouble with a particular consult team I would call him. | ||

| Urgency/severity of illness (13) | Clinical condition of patient requires immediate or urgent intervention. If I have something that is really pressing I would probably page my attending. If it's a question [of] just something that I didn't know the answer to [or] wasn't that urgent I could turn to my fellow residents. | ||

| Transitions of care (37) | Communication with supervisor because of concern/uncertainty regarding patient transition decisions. We wanted to know if it was okay to discharge somebody or if something changes where something in the plan changes. I usually text page her or call her. | ||

| Situation or environment characteristics (49) | Proximity of attending physicians and support staff (10) | Availability of attending physicians and staff resources . I have been called in once or twice to help with a lumbar puncture or paracentesis, but not too often. The procedure service makes life much easier than it used to be. | |

| Team culture (33) | Presence or absence of a collaborative and supportive group environment. I had a team that I did trust. I think we communicated well; we were all sort of on the same page. | ||

| Time of day (6) | Time of the task. Once its past 11 pm, I feel like I shouldn't call, the threshold is higherthe patient has to be sicker. | ||

| Domain (N) | Major Categories (N) | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Systems factors (99); unmodifiable factors not related to personal characteristics or knowledge of trainee or supervisor. | Workload (15) | Increasing trainee clinical workload results in a more intensive experience. They [residents] get 10 patients within a pretty concentrated timeso they really have to absorb a lot of information in a short period of time. |

| Institutional culture (4) | Anticipated quality of the trainee because of the status of the institution. I assume that our residents and interns are top notch, so I go in with this real assumption that I expect the best of them because we are [the best]. | |

| Clinical experience of trainee (36) | Types of clinical experience prior to supervisor/trainee interaction. The interns have done as much [general inpatient medicine] months as I havethey had both done like 2 or 3 months really close together, so they were sort of at their peak knowledge. | |

| Level of training (25) | Postgraduate year of trainee. It depends on the experience level of the resident. A second year who just finished internship, I am going to supervise more closely and be more detail oriented; a fourth year medicine‐pediatrics resident who is almost done, I will supervise a lot less. | |

| Duty hours/efficiency pressures (5) | Absence of residents due to other competing factors, including compliance with work‐hour restrictions. Before the work‐hour [restrictions], when [residents] were here all the time and knew everything about the patients, I found them to be a lot more reliableand now they are still supposed to be in charge, but hell I am here more often than they are. I am here every day, I have more information than they do. How can you run the show if you are not here every day? | |

| Philosophy of medical education (14) | Belief that trainees learn by the provision of completely autonomous decision making. When you are not around, [the residents] have autonomy, they are the people making the initial decisions and making the initial assessments. They are the ones who are there in the middle of the night, the ones who are there at 3 o'clock in the afternoon. The resident is supposed to have room to make decisions. When I am not there, it's not my show. | |

Trainee Factors

Attending and resident physicians both cited trainee factors as major determinants of granting entrustment (Table 1). Within the domain, the categories described included trainee personal characteristics and clinical characteristics. Of the subthemes noted within the major category of personal characteristics, the perceived confidence or overconfidence of the trainee was most often mentioned. Other subthemes included accountability, familiarity, and honesty. Attending physicians reported using perceived resident confidence as a gauge of the trainee's true ability and comfort. Conversely, some attending physicians reported that perceived overconfidence was a red flag that warranted increased scrutiny. Overconfidence was identified by faculty as trainees with an inability to recognize their limitations in either technical skill or knowledge. Confidence was noted in trainees that recognized their own limitations while also enacting effective management plans, and those physicians that prioritized the patient needs over their personal needs.

The clinical attributes of trainees described by attendings included: leadership skills, communication skills, anticipated specialty, medical knowledge, and perceived recognition of limitations. All participants expressed that the possession of adequate medical knowledge was the most important clinical skills‐related factor in the development of trust. Trainee demonstration of judgment, including applying evidence‐based practice, was used to support attending physician's decision to give residents more autonomy in managing patients. Many attending physicians described a specific pattern of observation and evaluation, in which they would rely on impressions shaped early in the rotation to inform their decisions of entrustment throughout the rotation. The use of this early litmus test was highlighted by several attending physicians. This litmus test described the importance of behavior on the first day/call night and postcall interactions as particularly important opportunities to gauge the ability of a resident to triage new patient admissions, manage their anxiety and uncertainty, and demonstrate maturity and professionalism. Several faculty members discussed examples of their litmus test including checking and knowing laboratory data prior to rounds but not mentioning their findings until they had noted the resident was unaware ([I]f I see a 2 g hemoglobin drop when I check the [electronic medical record {EMR}] and they don't bring it up, I will bring it to their attention, and then I'll get more involved.) or assessing the management of both straightforward and complex patients. They would then use this initial impression to determine their degree of involvement in the care of the patient.

The quality and nature of the communication skills, particularly the increased frequency of contact between resident and attending, was used as a barometer of trainee judgment. Furthermore, attending physicians expressed that they would often micromanage patient care if they did not trust a trainee's ability to reliably and frequently communicate patient status as well as the attendings concerns and uncertainty about future decisions. Some level of uncertainty was generally seen in a positive light by attending physicians, because it signaled that trainees had a mature understanding of their limitations. Finally, the trainee's expressed future specialty, especially if the trainee was a preliminary PGY‐1 resident, or a more senior resident anticipating subspecialty training in a procedural specialty, impacted the degree of autonomy provided.

Supervisor Factors

Supervisor characteristics were further categorized into their approachability and clinical attributes (Table 2). Approachability as a proxy for quality of the relationship, was cited as the personality characteristic that most influenced trust by the residents. This was often described by both attending and resident physicians as the presence of a supportive team atmosphere created through explicit declaration of availability to help with patient care tasks. Some attending physicians described the importance of expressing enthusiasm when receiving queries from their team to foster an atmosphere of nonjudgmental collaboration.

The clinical experience and knowledge base of the attending physician played a role in the provision of autonomy, particularly in times of disagreement about particular clinical decisions. Conversely, attending physicians who had spent less time on inpatient general medicine were more willing to yield to resident suggestions.

Task Factors

The domain of task factors was further divided into the categories that pertained to the clinical aspects of the task and those that pertained to the context, that is the environment in which the entrustment decisions were made (Table 3). Clinical characteristics included case complexity, presence of an ethical dilemma, interdepartmental collaboration, urgency/severity of situation, and transitions of care. The environmental characteristics included physical proximity of supervisors/support, team culture, and time of day. Increasing case complexity, especially the coexistence of legal and/or ethical dilemmas, was often mentioned as a factor driving greater attending involvement. Conversely, straightforward clinical decisions, such as electrolyte repletion, were described as sufficiently easy to allow limited attending involvement. Transitions of care, such as patient discharge or transfer, required greater communication and attending involvement or guidance, regardless of case complexity.

Attending and resident physicians reported that the team dynamics played a large role in the development, granting, or discouragement of trust. Teams with a positive rapport reported a collaborative environment that fostered increased trust by the attending and led to greater resident autonomy. Conversely, team discord that influenced the supervisor‐trainee relationship, often defined as toxic attitudes within the team, was often singled out as the reason attending physicians would feel the need to engage more directly in patient care and by extension have less trust in residents to manage their patients.

Systems Factors

Systems factors were described as the nonmodifiable factors, unrelated to either the characteristics of the supervisor, trainee, or the clinical task (Table 4). The subthemes that emerged included workload, institutional culture, trainee experience, level of training, and duty hours/efficiency pressures. Residents and attending physicians noted that trainee PGY and clinical experience commonly influenced the provision of autonomy and supervision by attendings. Participants reported that the importance of adequate clinical experience was of greater concern given the new duty‐hour restrictions, increased workload, as well as efficiency pressures. Attending physicians noted that trainee absences, even when required to comply with duty‐hour restrictions, had a negative effect on entrustment‐granting decisions. Many attendings felt that a trainee had to be physically present to make informed decisions on the inpatient medicine service.

DISCUSSION

Clinical supervisors must hold the quality of care constant while balancing the amount of supervision and autonomy provided to learners in procedural tasks and clinical decision making. We found that the development of trust is multifactorial and highly contextual. It occurs under the broad constructs of task, supervisor, trainee, and environmental factors, and is well described in prior work. We also demonstrate that often what determines these broader factors is highly subjective, frequently independent of objective measures of trainee performance. Many decisions are based on personal characteristics, such as the perception of honesty, disposition, perceived confidence or perceived overconfidence of the trainee, prior experience, and expressed future field of specialty.

Our findings are consistent with prior research, but go further in describing and demonstrating the existence and innovative use of factors, other than clinical knowledge and skill, in the formation of a multidimensional construct of trust. Kennedy et al. identified 4 dimensions of trust knowledge and skill, discernment, conscientiousness, and truthfulness[15]and demonstrated that supervising physicians rely on specific processes to assess trainee trustworthiness, specifically the use of double checks and language cues. This is consistent with our results, which demonstrate that many attending physicians independently verify information, such as laboratory findings, to inform their perceptions of trainee honesty, attention to detail, and ability to follow orders reliably. Furthermore, our subthemes of communication and the demonstration of logical clinical reasoning correspond to Kennedy's use of language cues.[15] We found that language cues are used as markers of trustworthiness, particularly early on in the rotation, as a litmus test to gauge the trainee's integrity and ability to assess and treat patients unsupervised.

To date, much has been written about the importance of direct observation in the evaluation of trainees.[16, 17, 18, 19] Our results demonstrate that supervising clinicians use a multifactorial, highly nuanced, and subjective process despite validated performance‐based assessment methods, such as the objective structured clinical exam or mini‐clinical evaluation exercise, to assess competence and grant entrustement.[3] Several factors utilized to determine trustworthiness in addition to direct observation are subjective in nature, specifically the trainee's prior experience and expressed career choice.

It is encouraging that attending physicians make use of direct observations to inform decisions of entrustment, albeit in an informal and unstructured way. They also seem to take into account the context and setting in which the observation occurs, and consider both the environmental factors as well as factors that relate to the task itself.[20] For example, attendings and residents reported that team dynamics played a large role in influencing trust decisions. We also found that attending physicians rely on indirect observation and will inquire among their colleagues and other senior residents to gain information about their trainees abilities and integrity. Evaluation tools that facilitate sharing of trainees' level of preparedness, prior feedback, and experience could facilitate the determination of readiness to complete EPAs as well as the reporting of achieved milestones in accordance with the ACGME NAS.

Sharing knowledge about trainees among attendings is common and of increasing importance in the context of attending physicians' shortened exposure to trainees due to the residency work‐hour restrictions and growing productivity pressures. In our study, attending physicians described work‐hour restrictions as detrimental to trainee trustworthiness, either in the context of decreased accountability for patient care or as intrinsic to the nature of forced absences that kept trainees from fully participating in daily ward activities and knowing their patients. Attending physicians felt that trainees did not know their patients well enough to be able to make independent decisions about care. The increased transition to a shift‐based structure of inpatient medicine may result in increasingly less time for direct observation and make it more difficult for attendings to justify their decisions about engendering trust. In addition, the increased fragmentation that is noted in training secondary to the work‐hour regulations may in fact have consequences on the development of clinical skill and decision making, such that increased attention to the need for supervision and longer lead to entrustment may be needed in certain circumstances. Attendings need guidance on how to improve their ability to observe trainees in the context of the new work environment, and how to role model decision making more effectively in the compressed time exposure to housestaff.

Our study has several limitations. The organizational structure and culture of our institution are unique to 1 academic setting. This may undermine our ability to generalize these research findings and analysis to the population at large.[21] In addition, recall bias may have played into the interpretation of the interview content given the timing with which they were performed after the conclusion of the rotation. The study interviews took place in 2006, and it is reasonable to believe that some perceptions concerning duty‐hour restrictions and competency‐based graduate medical education have changed. However, from our ongoing research over the past 5 years[4] and our personal experience with entrustment factors, we believe that the participants' perceptions of trust and competency are valid and have largely remained unchanged, given the similarity in findings to the accepted ten Cate framework. In addition, this work was done following the first iteration of the work‐hour regulations but prior to the implementation of explicit supervisory levels, so it may indeed represent a truer state of the supervisory relationship before external regulations were applied. Finally, this work represents an internal medicine residency training program and may not be generalizable to other specialties that posses different cultural factors that impact the decision for entrustment. However, the congruence of our data with that of the original work of ten Cate, which was done in gynecology,[6] and that of Sterkenberg et al. in anesthesiology,[4] supports our key factors being ubiquitous to all training programs.

In conclusion, we provide new insights into subjective factors that inform the perceptions of trust and entrustment decisions by supervising physicians, specifically subjective trainee characteristics, team dynamics, and informal observation. There was agreement among attendings about which elements of competence are considered most important in their entrustment decisions related to trainee, supervisor, task, and environmental factors. Rather than undervaluing the use of personal factors in the determination of trust, we believe that acknowledgement and appreciation of these factors may be important to give supervisors more confidence and better tools to assess resident physicians, and to understand how their personality traits relate to and impact their professional competence. Our findings are relevant for the development of assessment instruments to evaluate whether medical graduates are ready for safe practice without supervision.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Disclosures: Dr. Kevin Choo was supported by Scholarship and Discovery, University of Chicago, while in his role as a fourth‐year medical student. This study received institutional review board approval prior to evaluation of our human participants. Portions of this study were presented as an oral abstract at the 35th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, Orlando, Florida, May 912, 2012.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Common Program Requirements. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/429/ProgramandInstitutionalAccreditation/CommonProgramRequirements.aspx, Accessed November 30, 2013.

- , , . Measurement of the general competencies of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2009;84:301–309.

- , , , , . Toward authentic clinical evaluation: pitfalls in the pursuit of competency. Acad Med. 2010;85(5):780–786.

- , , , , . When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1408–1417.

- , , , . The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Eng J Med. 2012;366(11):1051–1056.

- . Trust, competence and the supervisor's role in postgraduate training. BMJ. 2006;333:748–751.

- , , , , . Clinical Decision Making and impact on patient care: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(2):122–126.

- , , , et al. Strategies for effective on call supervision for internal medicine residents: the superb/safety model. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(1):46–52.

- , , , , . On‐call supervision and resident autonomy: from micromanager to absentee attending. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):784–788.

- . The critical incident technique. Psychol Bull. 1954;51.4:327–359.

- , . Critical evaluation of appreciative inquiry: bridging an apparent paradox. Action Res. 2006;4(4):401–418.

- , . Basics of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998.

- , . How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- , . Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994.

- , , , . Point‐of‐care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008;84:S89–S92.

- , . Viewpoint: competency‐based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 2007;82(6):542–547.

- , , , et al. Assessment of competence and progressive independence in postgraduate clinical training. Med Educ. 2009;43:1156–1165.

- , , . Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: a systematic review. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1316–1326.

- . Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:387–396.

- , , , , . . A prospective study of paediatric cardiac surgical microsystems: assessing the relationships between non‐routine events, teamwork and patient outcomes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(7):599–603.

- . Generalizability and transferability of meta‐synthesis research findings. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(2):246–254.

Determining when residents are independently prepared to perform clinical care tasks safely is not easy or understood. Educators have struggled to identify robust ways to evaluate trainees and their preparedness to treat patients while unsupervised. Trust allows the trainee to experience increasing levels of participation and responsibility in the workplace in a way that builds competence for future practice. The breadth of knowledge and skills required to become a competent and safe physician, coupled with the busy workload confound this challenge. Notably, a technically proficient trainee may not have the clinical judgment to treat patients without supervision.

The Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has previously outlined 6 core competencies for residency training: patient care, medical knowledge, practice‐based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems‐based practice.[1] A systematic literature review suggests that traditional trainee evaluation tools are difficult to use and unreliable in measuring the competencies independently from one another, whereas certain competencies are consistently difficult to quantify in a reliable and valid way.[2] The evaluation of trainees' clinical performance despite efforts to create objective tools remain strongly influenced by subjective measures and continues to be highly variable among different evaluators.[3] Objectively measuring resident autonomy and readiness to supervise junior colleagues remains imprecise.[4]

The ACGME's Next Accreditation System (NAS) incorporates educational milestones as part of the reporting of resident training outcomes.[5] The milestones allow for the translation of the core competencies into integrative and observable abilities. Furthermore, the milestone categories are stratified into tiers to allow progress to be measured longitudinally and by task complexity using a novel assessment strategy.

The development of trust between supervisors and trainees is a critical step in decisions to allow increased responsibility and the provision of autonomous decision making, which is an important aspect of physician training. Identifying the factors that influence the supervisors' evaluation of resident competency and capability is at the crux of trainee maturation as well as patient safety.[4] Trust, defined as believability and discernment by attendings of resident physicians, plays a large role in attending evaluations of residents during their clinical rotations.[3] Trust impacts the decisions of successful performance of entrustable professional activities (EPAs), or those tasks that require mastery prior to completion of training milestones.[6] A study of entrustment decisions made by attending anesthesiologists identified the factors that contribute to the amount of autonomy given to residents, such as trainee trustworthiness, medical knowledge, and level of training.[4] The aim of our study, building on this study, was 2‐fold: (1) use deductive qualitative analysis to apply this framework to existing resident and attending data, and (2) define the categories within this framework and describe how internal medicine attending and resident physician perceptions of trust can impact clinical decision making and patient care.

METHODS

We are reporting on a secondary data analysis of interview transcripts from a study conducted on the inpatient general medicine service at the University of Chicago, an academic tertiary care medical center. The methods for data collection and full consent have been outlined previously.[7, 8, 9] The institutional review board of the University of Chicago approved this study.

Briefly, between January 2006 and November 2006, all eligible internal medicine resident physicians, postgraduate year (PGY)‐2 or PGY‐3, and attending physicians, either generalists or hospitalists, were privately interviewed within 1 week of their final call night on the inpatient general medicine rotation to assess decision making and clinical supervision during the rotation. All interviews were conducted by 1 investigator (J.F.), and discussions were audio taped and transcribed for analysis. Interviews were conducted at the conclusion of the rotation to prevent any influence on resident and attending behavior during the rotation.

The critical incident technique, a procedure used for collecting direct observations of human behavior that have critical significance on the decision‐making process, was used to solicit examples of ineffective supervision, inquiring about 2 to 3 important clinical decisions made on the most recent call night, with probes to identify issues of trust, autonomy, and decision making.[10] A critical incident can be described as one that makes a significant contribution, either positively or negatively, on the process.

Appreciative inquiry, a technique that aims to uncover the best things about the clinical encounter being explored, was used to solicit examples of effective supervision. Probes are used to identify factors, either personal or situational, that influenced the withholding or provision of resident autonomy during periods of clinical care delivery.[11]

All identifiable information was removed from the interview transcripts to protect participant and patient confidentiality. Deductive qualitative analysis was performed using the conceptual EPA framework, which describes several factors that influence the attending physicians' decisions to deem a resident trustworthy to independently fulfill a specific clinical task.[4] These factors include (1) the nature of the task, (2) the qualities of the supervisor, (3) the qualities of the trainee and the quality of the relationship between the supervisor and the trainee, and (4) the circumstances surrounding the clinical task.

The deidentified, anonymous transcripts were reviewed by 2 investigators (K.J.C., J.M.F.) and analyzed using the constant comparative methods to deductively map the content to the existing framework and generate novel sub themes.[12, 13, 14] Novel categories within each of the domains were inductively generated. Two reviewers (K.J.C., J.M.F.) independently applied the themes to a randomly selected 10% portion of the interview transcripts to assess the inter‐rater reliability. The inter‐rater agreement was assessed using the generalized kappa statistic. The discrepancies between reviewers regarding assignment of codes were resolved via discussion and third party adjudication until consensus was achieved on thematic structure. The codes were then applied to the entire dataset.

RESULTS

Between January 2006 and November 2006, 46 of 50 (88%) attending physicians and 44 of 50 (92%) resident physicians were interviewed following the conclusion of their general medicine inpatient rotation. Of attending physicians, 55% were male, 45% were female, and 38% were academic faculty hospitalists. Of the residents who completed interviews, 47% were male, 53% were female, 52% were PGY‐2, and 45% were PGY‐3.

A total of 535 mentions of trust were abstracted from the transcripts. The 4 major domains that influence trusttrainee factors (Table 1), supervisor factors (Table 2), task factors (Table 3), and systems factors (Table 4)were deductively coded with several emerging novel categories and subthemes. The domains were consistent across the postgraduate year of trainee. No differences in themes were noted, other than those explicitly stated, between the postgraduate years.

| Domain (N) | Category (N) | Subtheme (N) | Definition and Representative Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Trainee factors (170); characteristics specific to the trainee that either promote or discourage trust. | Personal characteristics (78); traits that impact attendings' decision regarding trust/allowance of autonomy. | Confidence and overconfidence (29) | Displayed level of comfort when approaching specific clinical situations. I think I havea personality and presenting style [that] people think that I know what I am talkingabout and they just let me run with it. (R) |

| Accountability (18) | Sense of responsibility, including ability to follow‐up on details regarding patient care. [What] bothered me the most was that that kind of lack of accountability for patient careand it makes the whole dynamic of rounds much more stressful. I ended up asking him to page me every day to run the list. (A) | ||

| Familiarity/ reputation (18) | Comfort with trainee gained through prior working experience, or reputation of the trainee based on discussion with other supervisors. I do have to get to know someone a little to develop that level of trust, to know that it is okay to not check the labs every day, okay to not talk to them every afternoon. (A) | ||

| Honesty (13) | Sense trainee is not withholding information in order to impact decision making toward a specific outcome. [The residents] have more information than I do and they can clearly spin that information, and it is very difficult to unravelunless you treat them like a hostile witness on the stand.(A) | ||

| Clinical attributes (92); skills demonstrated in the context of patient care that promote or inhibit trust. | Leadership (19) | Ability to organize, teach, and manage coresidents, interns, and students. I want them to be in chargedeciding the plan and sitting down with the team before rounds. (A) | |

| Communication (12) | Establishing and encouraging conversation with supervisor regarding decision making.Some residents call me regularly and let me know what's going on and others don't, and those who don't I really have trouble withif you're not calling to check in, then I don't trust your judgment. (A) | ||

| Specialty (6) | Trainee future career plans. Whether it's right or wrong, nonmedicine interns may not be as attentive to smaller details, and so I had to be attentive to smaller details on [his] patients. (R2) | ||

| Medical knowledge (39) | Ability to display appropriate level of clinical acumen and apply evidence‐based medicine. I definitelygo on my own gestalt of talking with them and deciding if what they do is reasonable. If they can't explain things to me, that's when I worry. (A) | ||

| Recognition of limitations (16) | Trainee's ability to recognize his/her own weaknesses, accept criticism, and solicit help when appropriate. The first thing is that they know their limits and ask for help either in rounds or outside of rounds. That indicates to me that as they are out there on their own they are less likely to do things that they don't understand. (A) | ||

| Domain (N) | Major Category (N) | Subtheme (N) | Definition and Representative Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Supervisor factors (120); characteristics specific to the supervisor which either promote or discourage trust. | Approachability (34); personality traits, such as approachability, which impact the trainees' perception regarding trust/allowance of autonomy. | Sense that the attending physician is available to and receptive to questions from trainees. I think [attending physicians] being approachable and available to you if you need them is really helpful. (R) | |

| Clinical attributes (86); skills demonstrated in the context of patient care that promote or inhibit trust. | Institutional obligation (17) | Attending physician is the one contractually and legally responsible for the provision of high‐quality and appropriate patient care. If [the residents] have a good reason I can be argued out of my position. I am ultimately responsible andhave to choose if there is some serious dispute. (A) | |

| Experience and expertise (29) | Clinical experience, area of specialty, and research interests of the attending physician. You have to be confident in your own clinical skills and knowledge, confident enough that you can say its okay for me to let go a little bit. (A) | ||

| Observation‐based evaluation (27) | Evaluation of trainee decision‐making ability during the early part of the attending/trainee relationship. It's usually the first post‐call day experience, the first on‐call and post‐call day experience. One of the big things is [if they can] tell if a patient is sick or not sickif they are missing at that level then I get very nervous. I really get a sense [of] how they think about patients. (A) | ||

| Educational obligation (13) | Acknowledging the role of the attending as clinical teacher. My theory with the interns was that they should do it because that's how you learn. (R) | ||

| Domain (N) | Major Category (N) | Subtheme (N) | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Task factors (146); details or characteristics of the task that encouraged or impeded contacting the supervisor. | Clinical characteristics (103) | Case complexity (25) | Evaluation of the level of difficulty in patient management. I don't expect to be always looking over [the resident's] shoulder, I don't check labs everyday, and I don't call them if I see potassium of 3; I assume that they are going to take care of it. |

| Family/ethical dilemma (10) | Uncertainty regarding respecting the wishes of patients and other ethical dilemmas. There was 1 time I called because we had a very sick patient who had a lot of family asking for more aggressive measures, and I called to be a part of the conversation. | ||

| Interdepartment collaboration (18) | Difficulties when treating patients managed by multiple consult services. I have called [the attending] when I have had trouble pushing things through the systemif we had trouble getting tests or trouble with a particular consult team I would call him. | ||

| Urgency/severity of illness (13) | Clinical condition of patient requires immediate or urgent intervention. If I have something that is really pressing I would probably page my attending. If it's a question [of] just something that I didn't know the answer to [or] wasn't that urgent I could turn to my fellow residents. | ||

| Transitions of care (37) | Communication with supervisor because of concern/uncertainty regarding patient transition decisions. We wanted to know if it was okay to discharge somebody or if something changes where something in the plan changes. I usually text page her or call her. | ||

| Situation or environment characteristics (49) | Proximity of attending physicians and support staff (10) | Availability of attending physicians and staff resources . I have been called in once or twice to help with a lumbar puncture or paracentesis, but not too often. The procedure service makes life much easier than it used to be. | |

| Team culture (33) | Presence or absence of a collaborative and supportive group environment. I had a team that I did trust. I think we communicated well; we were all sort of on the same page. | ||

| Time of day (6) | Time of the task. Once its past 11 pm, I feel like I shouldn't call, the threshold is higherthe patient has to be sicker. | ||

| Domain (N) | Major Categories (N) | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Systems factors (99); unmodifiable factors not related to personal characteristics or knowledge of trainee or supervisor. | Workload (15) | Increasing trainee clinical workload results in a more intensive experience. They [residents] get 10 patients within a pretty concentrated timeso they really have to absorb a lot of information in a short period of time. |

| Institutional culture (4) | Anticipated quality of the trainee because of the status of the institution. I assume that our residents and interns are top notch, so I go in with this real assumption that I expect the best of them because we are [the best]. | |

| Clinical experience of trainee (36) | Types of clinical experience prior to supervisor/trainee interaction. The interns have done as much [general inpatient medicine] months as I havethey had both done like 2 or 3 months really close together, so they were sort of at their peak knowledge. | |

| Level of training (25) | Postgraduate year of trainee. It depends on the experience level of the resident. A second year who just finished internship, I am going to supervise more closely and be more detail oriented; a fourth year medicine‐pediatrics resident who is almost done, I will supervise a lot less. | |

| Duty hours/efficiency pressures (5) | Absence of residents due to other competing factors, including compliance with work‐hour restrictions. Before the work‐hour [restrictions], when [residents] were here all the time and knew everything about the patients, I found them to be a lot more reliableand now they are still supposed to be in charge, but hell I am here more often than they are. I am here every day, I have more information than they do. How can you run the show if you are not here every day? | |

| Philosophy of medical education (14) | Belief that trainees learn by the provision of completely autonomous decision making. When you are not around, [the residents] have autonomy, they are the people making the initial decisions and making the initial assessments. They are the ones who are there in the middle of the night, the ones who are there at 3 o'clock in the afternoon. The resident is supposed to have room to make decisions. When I am not there, it's not my show. | |

Trainee Factors

Attending and resident physicians both cited trainee factors as major determinants of granting entrustment (Table 1). Within the domain, the categories described included trainee personal characteristics and clinical characteristics. Of the subthemes noted within the major category of personal characteristics, the perceived confidence or overconfidence of the trainee was most often mentioned. Other subthemes included accountability, familiarity, and honesty. Attending physicians reported using perceived resident confidence as a gauge of the trainee's true ability and comfort. Conversely, some attending physicians reported that perceived overconfidence was a red flag that warranted increased scrutiny. Overconfidence was identified by faculty as trainees with an inability to recognize their limitations in either technical skill or knowledge. Confidence was noted in trainees that recognized their own limitations while also enacting effective management plans, and those physicians that prioritized the patient needs over their personal needs.

The clinical attributes of trainees described by attendings included: leadership skills, communication skills, anticipated specialty, medical knowledge, and perceived recognition of limitations. All participants expressed that the possession of adequate medical knowledge was the most important clinical skills‐related factor in the development of trust. Trainee demonstration of judgment, including applying evidence‐based practice, was used to support attending physician's decision to give residents more autonomy in managing patients. Many attending physicians described a specific pattern of observation and evaluation, in which they would rely on impressions shaped early in the rotation to inform their decisions of entrustment throughout the rotation. The use of this early litmus test was highlighted by several attending physicians. This litmus test described the importance of behavior on the first day/call night and postcall interactions as particularly important opportunities to gauge the ability of a resident to triage new patient admissions, manage their anxiety and uncertainty, and demonstrate maturity and professionalism. Several faculty members discussed examples of their litmus test including checking and knowing laboratory data prior to rounds but not mentioning their findings until they had noted the resident was unaware ([I]f I see a 2 g hemoglobin drop when I check the [electronic medical record {EMR}] and they don't bring it up, I will bring it to their attention, and then I'll get more involved.) or assessing the management of both straightforward and complex patients. They would then use this initial impression to determine their degree of involvement in the care of the patient.

The quality and nature of the communication skills, particularly the increased frequency of contact between resident and attending, was used as a barometer of trainee judgment. Furthermore, attending physicians expressed that they would often micromanage patient care if they did not trust a trainee's ability to reliably and frequently communicate patient status as well as the attendings concerns and uncertainty about future decisions. Some level of uncertainty was generally seen in a positive light by attending physicians, because it signaled that trainees had a mature understanding of their limitations. Finally, the trainee's expressed future specialty, especially if the trainee was a preliminary PGY‐1 resident, or a more senior resident anticipating subspecialty training in a procedural specialty, impacted the degree of autonomy provided.

Supervisor Factors

Supervisor characteristics were further categorized into their approachability and clinical attributes (Table 2). Approachability as a proxy for quality of the relationship, was cited as the personality characteristic that most influenced trust by the residents. This was often described by both attending and resident physicians as the presence of a supportive team atmosphere created through explicit declaration of availability to help with patient care tasks. Some attending physicians described the importance of expressing enthusiasm when receiving queries from their team to foster an atmosphere of nonjudgmental collaboration.

The clinical experience and knowledge base of the attending physician played a role in the provision of autonomy, particularly in times of disagreement about particular clinical decisions. Conversely, attending physicians who had spent less time on inpatient general medicine were more willing to yield to resident suggestions.

Task Factors

The domain of task factors was further divided into the categories that pertained to the clinical aspects of the task and those that pertained to the context, that is the environment in which the entrustment decisions were made (Table 3). Clinical characteristics included case complexity, presence of an ethical dilemma, interdepartmental collaboration, urgency/severity of situation, and transitions of care. The environmental characteristics included physical proximity of supervisors/support, team culture, and time of day. Increasing case complexity, especially the coexistence of legal and/or ethical dilemmas, was often mentioned as a factor driving greater attending involvement. Conversely, straightforward clinical decisions, such as electrolyte repletion, were described as sufficiently easy to allow limited attending involvement. Transitions of care, such as patient discharge or transfer, required greater communication and attending involvement or guidance, regardless of case complexity.

Attending and resident physicians reported that the team dynamics played a large role in the development, granting, or discouragement of trust. Teams with a positive rapport reported a collaborative environment that fostered increased trust by the attending and led to greater resident autonomy. Conversely, team discord that influenced the supervisor‐trainee relationship, often defined as toxic attitudes within the team, was often singled out as the reason attending physicians would feel the need to engage more directly in patient care and by extension have less trust in residents to manage their patients.

Systems Factors

Systems factors were described as the nonmodifiable factors, unrelated to either the characteristics of the supervisor, trainee, or the clinical task (Table 4). The subthemes that emerged included workload, institutional culture, trainee experience, level of training, and duty hours/efficiency pressures. Residents and attending physicians noted that trainee PGY and clinical experience commonly influenced the provision of autonomy and supervision by attendings. Participants reported that the importance of adequate clinical experience was of greater concern given the new duty‐hour restrictions, increased workload, as well as efficiency pressures. Attending physicians noted that trainee absences, even when required to comply with duty‐hour restrictions, had a negative effect on entrustment‐granting decisions. Many attendings felt that a trainee had to be physically present to make informed decisions on the inpatient medicine service.

DISCUSSION

Clinical supervisors must hold the quality of care constant while balancing the amount of supervision and autonomy provided to learners in procedural tasks and clinical decision making. We found that the development of trust is multifactorial and highly contextual. It occurs under the broad constructs of task, supervisor, trainee, and environmental factors, and is well described in prior work. We also demonstrate that often what determines these broader factors is highly subjective, frequently independent of objective measures of trainee performance. Many decisions are based on personal characteristics, such as the perception of honesty, disposition, perceived confidence or perceived overconfidence of the trainee, prior experience, and expressed future field of specialty.

Our findings are consistent with prior research, but go further in describing and demonstrating the existence and innovative use of factors, other than clinical knowledge and skill, in the formation of a multidimensional construct of trust. Kennedy et al. identified 4 dimensions of trust knowledge and skill, discernment, conscientiousness, and truthfulness[15]and demonstrated that supervising physicians rely on specific processes to assess trainee trustworthiness, specifically the use of double checks and language cues. This is consistent with our results, which demonstrate that many attending physicians independently verify information, such as laboratory findings, to inform their perceptions of trainee honesty, attention to detail, and ability to follow orders reliably. Furthermore, our subthemes of communication and the demonstration of logical clinical reasoning correspond to Kennedy's use of language cues.[15] We found that language cues are used as markers of trustworthiness, particularly early on in the rotation, as a litmus test to gauge the trainee's integrity and ability to assess and treat patients unsupervised.

To date, much has been written about the importance of direct observation in the evaluation of trainees.[16, 17, 18, 19] Our results demonstrate that supervising clinicians use a multifactorial, highly nuanced, and subjective process despite validated performance‐based assessment methods, such as the objective structured clinical exam or mini‐clinical evaluation exercise, to assess competence and grant entrustement.[3] Several factors utilized to determine trustworthiness in addition to direct observation are subjective in nature, specifically the trainee's prior experience and expressed career choice.

It is encouraging that attending physicians make use of direct observations to inform decisions of entrustment, albeit in an informal and unstructured way. They also seem to take into account the context and setting in which the observation occurs, and consider both the environmental factors as well as factors that relate to the task itself.[20] For example, attendings and residents reported that team dynamics played a large role in influencing trust decisions. We also found that attending physicians rely on indirect observation and will inquire among their colleagues and other senior residents to gain information about their trainees abilities and integrity. Evaluation tools that facilitate sharing of trainees' level of preparedness, prior feedback, and experience could facilitate the determination of readiness to complete EPAs as well as the reporting of achieved milestones in accordance with the ACGME NAS.

Sharing knowledge about trainees among attendings is common and of increasing importance in the context of attending physicians' shortened exposure to trainees due to the residency work‐hour restrictions and growing productivity pressures. In our study, attending physicians described work‐hour restrictions as detrimental to trainee trustworthiness, either in the context of decreased accountability for patient care or as intrinsic to the nature of forced absences that kept trainees from fully participating in daily ward activities and knowing their patients. Attending physicians felt that trainees did not know their patients well enough to be able to make independent decisions about care. The increased transition to a shift‐based structure of inpatient medicine may result in increasingly less time for direct observation and make it more difficult for attendings to justify their decisions about engendering trust. In addition, the increased fragmentation that is noted in training secondary to the work‐hour regulations may in fact have consequences on the development of clinical skill and decision making, such that increased attention to the need for supervision and longer lead to entrustment may be needed in certain circumstances. Attendings need guidance on how to improve their ability to observe trainees in the context of the new work environment, and how to role model decision making more effectively in the compressed time exposure to housestaff.