User login

The Downside of Truth

At a recent surgical Morbidity and Mortality Conference, we discussed a tragic case of an elderly gentleman who had been explored for a gastric outlet obstruction. He was found to have a widely metastatic malignancy of unknown primary that was clearly unresectable. Biopsies were taken, a bypass was performed to alleviate the obstruction, and the patient was closed. The surgeon subsequently discussed the findings with the patient and his family. They were understandably upset after getting the news, but plans were made for follow-up and possible treatment when the final pathology was back. During several days in the hospital, the patient seemed to be in good spirits and was seen regularly, encouraging his family not to worry. However, on the day of discharge, the patient went home and committed suicide.

This case raised a series of important questions at the Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) Conference. Had the patient shown signs of depression? Should he have been evaluated by psychiatry? Did the surgical team miss any signs of his impending actions? In the tradition of M&M Conferences, the discussion focused on the question, "What would you have done differently?"

One issue repeatedly raised in the discussions at conference given the patient’s response was whether he should have been told his diagnosis. Such a consideration is a radical idea today when no physician would argue against telling a patient a diagnosis of cancer. But this consensus of full disclosure is relatively new in the medical profession. In 1961, 88% of physicians surveyed at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago stated that their general policy was not to disclose a cancer diagnosis to the patient (JAMA 1961;175:1120-8). Certainly, this view among physicians has changed dramatically in recent decades. By 1979, the same survey at the same hospital revealed that 98% of physicians said that they tell patients that when the diagnosis is cancer (JAMA 1979;241:897-900).

In the medical profession, a diagnosis is no longer seen as information that can be withheld from a patient. The idea of respecting the patient as a person means that the patient must have the information necessary to make decisions about his or her future.

In this context, the recent New York Times article entitled "When Doctors Need to Lie" (Feb. 22, 2014) is provocative. Dr. Sandeep Jauhar suggests that sometimes there are situations in which doctors need to exercise a form of paternalism and lie to patients for their own benefit. Dr. Jauhar described a case in which he informed the family of a young patient of the true diagnosis, but only gradually and gently told the young man of his true condition.

Informing the elderly gentleman of his diagnosis may well have triggered his suicide. If the patient had not known that he had unresectable cancer, he could well still be alive. Nevertheless, no one at the M&M conference thought that lying about the diagnosis could be justified. Knowing the diagnosis is the fundamental basis for a patient to project a future existence. The ability to make the best medical and nonmedical decisions is dependent on having valid information. Without truthful information, the decisions made are uninformed and no better than guesses. It is not the physician’s role to guess the reaction of a patient to a diagnosis or project a future circumstance that may result from the patient learning the truth.

While the outcome of the transmission of knowledge to the patient may at times be unfortunate, the ethical implications of not telling patients the truth are potentially even more unfortunate. How can a surgeon establish a relationship of trust while also lying to a patient or withholding important information? Even though the choice made by this particular patient was tragic, to have lied to him is contrary to the physician’s role. Truth is the basis of trust, and trust in turn must be the basis of the relationship between doctor and patient.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

At a recent surgical Morbidity and Mortality Conference, we discussed a tragic case of an elderly gentleman who had been explored for a gastric outlet obstruction. He was found to have a widely metastatic malignancy of unknown primary that was clearly unresectable. Biopsies were taken, a bypass was performed to alleviate the obstruction, and the patient was closed. The surgeon subsequently discussed the findings with the patient and his family. They were understandably upset after getting the news, but plans were made for follow-up and possible treatment when the final pathology was back. During several days in the hospital, the patient seemed to be in good spirits and was seen regularly, encouraging his family not to worry. However, on the day of discharge, the patient went home and committed suicide.

This case raised a series of important questions at the Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) Conference. Had the patient shown signs of depression? Should he have been evaluated by psychiatry? Did the surgical team miss any signs of his impending actions? In the tradition of M&M Conferences, the discussion focused on the question, "What would you have done differently?"

One issue repeatedly raised in the discussions at conference given the patient’s response was whether he should have been told his diagnosis. Such a consideration is a radical idea today when no physician would argue against telling a patient a diagnosis of cancer. But this consensus of full disclosure is relatively new in the medical profession. In 1961, 88% of physicians surveyed at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago stated that their general policy was not to disclose a cancer diagnosis to the patient (JAMA 1961;175:1120-8). Certainly, this view among physicians has changed dramatically in recent decades. By 1979, the same survey at the same hospital revealed that 98% of physicians said that they tell patients that when the diagnosis is cancer (JAMA 1979;241:897-900).

In the medical profession, a diagnosis is no longer seen as information that can be withheld from a patient. The idea of respecting the patient as a person means that the patient must have the information necessary to make decisions about his or her future.

In this context, the recent New York Times article entitled "When Doctors Need to Lie" (Feb. 22, 2014) is provocative. Dr. Sandeep Jauhar suggests that sometimes there are situations in which doctors need to exercise a form of paternalism and lie to patients for their own benefit. Dr. Jauhar described a case in which he informed the family of a young patient of the true diagnosis, but only gradually and gently told the young man of his true condition.

Informing the elderly gentleman of his diagnosis may well have triggered his suicide. If the patient had not known that he had unresectable cancer, he could well still be alive. Nevertheless, no one at the M&M conference thought that lying about the diagnosis could be justified. Knowing the diagnosis is the fundamental basis for a patient to project a future existence. The ability to make the best medical and nonmedical decisions is dependent on having valid information. Without truthful information, the decisions made are uninformed and no better than guesses. It is not the physician’s role to guess the reaction of a patient to a diagnosis or project a future circumstance that may result from the patient learning the truth.

While the outcome of the transmission of knowledge to the patient may at times be unfortunate, the ethical implications of not telling patients the truth are potentially even more unfortunate. How can a surgeon establish a relationship of trust while also lying to a patient or withholding important information? Even though the choice made by this particular patient was tragic, to have lied to him is contrary to the physician’s role. Truth is the basis of trust, and trust in turn must be the basis of the relationship between doctor and patient.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

At a recent surgical Morbidity and Mortality Conference, we discussed a tragic case of an elderly gentleman who had been explored for a gastric outlet obstruction. He was found to have a widely metastatic malignancy of unknown primary that was clearly unresectable. Biopsies were taken, a bypass was performed to alleviate the obstruction, and the patient was closed. The surgeon subsequently discussed the findings with the patient and his family. They were understandably upset after getting the news, but plans were made for follow-up and possible treatment when the final pathology was back. During several days in the hospital, the patient seemed to be in good spirits and was seen regularly, encouraging his family not to worry. However, on the day of discharge, the patient went home and committed suicide.

This case raised a series of important questions at the Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) Conference. Had the patient shown signs of depression? Should he have been evaluated by psychiatry? Did the surgical team miss any signs of his impending actions? In the tradition of M&M Conferences, the discussion focused on the question, "What would you have done differently?"

One issue repeatedly raised in the discussions at conference given the patient’s response was whether he should have been told his diagnosis. Such a consideration is a radical idea today when no physician would argue against telling a patient a diagnosis of cancer. But this consensus of full disclosure is relatively new in the medical profession. In 1961, 88% of physicians surveyed at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago stated that their general policy was not to disclose a cancer diagnosis to the patient (JAMA 1961;175:1120-8). Certainly, this view among physicians has changed dramatically in recent decades. By 1979, the same survey at the same hospital revealed that 98% of physicians said that they tell patients that when the diagnosis is cancer (JAMA 1979;241:897-900).

In the medical profession, a diagnosis is no longer seen as information that can be withheld from a patient. The idea of respecting the patient as a person means that the patient must have the information necessary to make decisions about his or her future.

In this context, the recent New York Times article entitled "When Doctors Need to Lie" (Feb. 22, 2014) is provocative. Dr. Sandeep Jauhar suggests that sometimes there are situations in which doctors need to exercise a form of paternalism and lie to patients for their own benefit. Dr. Jauhar described a case in which he informed the family of a young patient of the true diagnosis, but only gradually and gently told the young man of his true condition.

Informing the elderly gentleman of his diagnosis may well have triggered his suicide. If the patient had not known that he had unresectable cancer, he could well still be alive. Nevertheless, no one at the M&M conference thought that lying about the diagnosis could be justified. Knowing the diagnosis is the fundamental basis for a patient to project a future existence. The ability to make the best medical and nonmedical decisions is dependent on having valid information. Without truthful information, the decisions made are uninformed and no better than guesses. It is not the physician’s role to guess the reaction of a patient to a diagnosis or project a future circumstance that may result from the patient learning the truth.

While the outcome of the transmission of knowledge to the patient may at times be unfortunate, the ethical implications of not telling patients the truth are potentially even more unfortunate. How can a surgeon establish a relationship of trust while also lying to a patient or withholding important information? Even though the choice made by this particular patient was tragic, to have lied to him is contrary to the physician’s role. Truth is the basis of trust, and trust in turn must be the basis of the relationship between doctor and patient.

Dr. Angelos is an ACS Fellow; the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Obesity: American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE)

Obesity rates in the United States have skyrocketed over the last 30 years, with rates for adults having doubled and rates for children tripled from 1980 to 2010. Approximately one-third of the U.S adult population is obese; that’s 72 million people. The consequences of obesity include an increased risk for stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, liver and gallbladder disease, orthopedic complications, mental health conditions, cancers, elevated lipids, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and reproductive complications such as infertility.

There is now solid evidence that we can intervene to help patient lose weight and decrease the complications that result from obesity. To this end, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) has issued recommendations giving guidance for clinicians about how to approach this issue. Intensive approaches to lifestyle modification with diet and exercise can help patients lose 7% or more of their body weight and have been show to decrease progression from prediabetes to diabetes. Two new medications, lorcaserin and phentermine/topiramate ER, have received Food and Drug Administration approval over the past 2 years as an adjunct to diet for weight loss. Bariatric surgery has emerged as a safe and effective method of weight loss as well.

The AACE guidelines focus on a "complications-centric model" as opposed to a body mass index–driven approach. The guidelines recommend treating obesity to decrease the risk of developing adverse metabolic consequences such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome, and to decrease disability from mechanical comorbidities such as osteoarthritis and obstructive sleep apnea. The AACE guidelines place obese patients into two categories: those that have obesity-related comorbidities and those that do not. The guidelines recommend a graded approach to treatment. All overweight and obese patients should receive therapeutic lifestyle counseling focusing on diet and exercise. Medical or surgical treatment is then recommended for the patients who stand to benefit the most, those with obesity-related comorbidities and those with more severe obesity who have not been able to lose weight using lifestyle modification alone.

In the initial evaluation of overweight and obese patients, the patients should be assessed for cardiometabolic and mechanical complications of obesity, as well as the severity of those complications in order to determine the level of treatment that is appropriate. Patients with obesity-related comorbidities are classified into two groups. The first group includes those with insulin resistance and/or cardiovascular consequences. For this group, evaluation should include waist circumference, fasting, and 2-hour glucose tolerance testing, and lipids, blood pressure, and liver function testing. The second group is composed of people with mechanical consequences including OSA, stress incontinence, orthopedic complications, and chronic pulmonary diseases.

It is important to determine target goals for weight loss to improve mechanical and cardiometabolic complications. Weight loss of 5% or more is enough to affect improvement in metabolic parameters such as glucose and lipids, decrease progression to diabetes, and improve mechanical complications such as knee and hip pain in osteoarthritis. The next step in the approach to treatment is to determine the type and intensity. Therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLC) are important for all patients with diabetes and prediabetes, regardless of risk factors. TLC recommendations include smoking cessation, physical activity, weight management, and healthy eating. Exercise is recommended 5 days/week for more than 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity, to achieve a more than 60% age-related heart rate. The diet recommended reduced saturated fat to less than 7% of calories, reduced cholesterol intake to 200 mg/day, increased fiber to 10-25 g/day, increased plant sterols/stanol esters to 2 g/day, caloric restriction, reduced simple carbohydrates and sugars, increased intake of unsaturated fats, elimination of trans fats, increased marine-based omega-3 ethyl esters, and restriction of alcohol to 20-30 g/day.

For patients with comorbidities and with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or more, consideration should be given to weight-loss medication in addition to lifestyle intervention. The currently approved medications for long-term weight loss include lorcaserin and phentermine/topiramate ER. In the FDA registration studies, the lorcaserin group had an average weight loss of 5.8% after 1 year vs. 2.2% in the placebo group. Phentermine/topiramate ER had an average weight loss of 10% at 1 year vs. 1.2% in the placebo group. These medications are FDA approved as adjuncts to lifestyle modification for the treatment of overweight patients with a BMI greater than 27 kg/m2 with comorbidities and for obese patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 regardless of comorbidities. Both medications improve blood pressure, triglycerides, and insulin sensitivity and prevent the progression to diabetes in patients with diabetes. Bariatric surgery should be considered for those with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or morewith comorbidities, especially if they have failed using other methods.

Once goals are reached, reassess the patient to evaluate for more interventions, if needed. If the targets for improvement in complications were not reached, then the weight loss therapy should become more intense.

Bottom line

The AACE recommendations recognize obesity as a disease and have formulated guidelines using a "complications-centric model." Patients should be assessed for obesity and related complications. Lifestyle counseling should be provided for all overweight and obese individuals, with the addition of weight loss medications for individuals with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or more who have obesity-related comorbidities, and the consideration of bariatric surgery for those with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more with comorbidities.

Reference

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ Comprehensive Diabetes Management Algorithm 2013 Consensus Statement. Published May/June 2013, Endocrine Practice, Vol. 19 (Suppl. 2).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. Dr. McDonald is a second-year resident in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Obesity rates in the United States have skyrocketed over the last 30 years, with rates for adults having doubled and rates for children tripled from 1980 to 2010. Approximately one-third of the U.S adult population is obese; that’s 72 million people. The consequences of obesity include an increased risk for stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, liver and gallbladder disease, orthopedic complications, mental health conditions, cancers, elevated lipids, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and reproductive complications such as infertility.

There is now solid evidence that we can intervene to help patient lose weight and decrease the complications that result from obesity. To this end, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) has issued recommendations giving guidance for clinicians about how to approach this issue. Intensive approaches to lifestyle modification with diet and exercise can help patients lose 7% or more of their body weight and have been show to decrease progression from prediabetes to diabetes. Two new medications, lorcaserin and phentermine/topiramate ER, have received Food and Drug Administration approval over the past 2 years as an adjunct to diet for weight loss. Bariatric surgery has emerged as a safe and effective method of weight loss as well.

The AACE guidelines focus on a "complications-centric model" as opposed to a body mass index–driven approach. The guidelines recommend treating obesity to decrease the risk of developing adverse metabolic consequences such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome, and to decrease disability from mechanical comorbidities such as osteoarthritis and obstructive sleep apnea. The AACE guidelines place obese patients into two categories: those that have obesity-related comorbidities and those that do not. The guidelines recommend a graded approach to treatment. All overweight and obese patients should receive therapeutic lifestyle counseling focusing on diet and exercise. Medical or surgical treatment is then recommended for the patients who stand to benefit the most, those with obesity-related comorbidities and those with more severe obesity who have not been able to lose weight using lifestyle modification alone.

In the initial evaluation of overweight and obese patients, the patients should be assessed for cardiometabolic and mechanical complications of obesity, as well as the severity of those complications in order to determine the level of treatment that is appropriate. Patients with obesity-related comorbidities are classified into two groups. The first group includes those with insulin resistance and/or cardiovascular consequences. For this group, evaluation should include waist circumference, fasting, and 2-hour glucose tolerance testing, and lipids, blood pressure, and liver function testing. The second group is composed of people with mechanical consequences including OSA, stress incontinence, orthopedic complications, and chronic pulmonary diseases.

It is important to determine target goals for weight loss to improve mechanical and cardiometabolic complications. Weight loss of 5% or more is enough to affect improvement in metabolic parameters such as glucose and lipids, decrease progression to diabetes, and improve mechanical complications such as knee and hip pain in osteoarthritis. The next step in the approach to treatment is to determine the type and intensity. Therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLC) are important for all patients with diabetes and prediabetes, regardless of risk factors. TLC recommendations include smoking cessation, physical activity, weight management, and healthy eating. Exercise is recommended 5 days/week for more than 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity, to achieve a more than 60% age-related heart rate. The diet recommended reduced saturated fat to less than 7% of calories, reduced cholesterol intake to 200 mg/day, increased fiber to 10-25 g/day, increased plant sterols/stanol esters to 2 g/day, caloric restriction, reduced simple carbohydrates and sugars, increased intake of unsaturated fats, elimination of trans fats, increased marine-based omega-3 ethyl esters, and restriction of alcohol to 20-30 g/day.

For patients with comorbidities and with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or more, consideration should be given to weight-loss medication in addition to lifestyle intervention. The currently approved medications for long-term weight loss include lorcaserin and phentermine/topiramate ER. In the FDA registration studies, the lorcaserin group had an average weight loss of 5.8% after 1 year vs. 2.2% in the placebo group. Phentermine/topiramate ER had an average weight loss of 10% at 1 year vs. 1.2% in the placebo group. These medications are FDA approved as adjuncts to lifestyle modification for the treatment of overweight patients with a BMI greater than 27 kg/m2 with comorbidities and for obese patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 regardless of comorbidities. Both medications improve blood pressure, triglycerides, and insulin sensitivity and prevent the progression to diabetes in patients with diabetes. Bariatric surgery should be considered for those with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or morewith comorbidities, especially if they have failed using other methods.

Once goals are reached, reassess the patient to evaluate for more interventions, if needed. If the targets for improvement in complications were not reached, then the weight loss therapy should become more intense.

Bottom line

The AACE recommendations recognize obesity as a disease and have formulated guidelines using a "complications-centric model." Patients should be assessed for obesity and related complications. Lifestyle counseling should be provided for all overweight and obese individuals, with the addition of weight loss medications for individuals with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or more who have obesity-related comorbidities, and the consideration of bariatric surgery for those with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more with comorbidities.

Reference

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ Comprehensive Diabetes Management Algorithm 2013 Consensus Statement. Published May/June 2013, Endocrine Practice, Vol. 19 (Suppl. 2).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. Dr. McDonald is a second-year resident in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Obesity rates in the United States have skyrocketed over the last 30 years, with rates for adults having doubled and rates for children tripled from 1980 to 2010. Approximately one-third of the U.S adult population is obese; that’s 72 million people. The consequences of obesity include an increased risk for stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, liver and gallbladder disease, orthopedic complications, mental health conditions, cancers, elevated lipids, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and reproductive complications such as infertility.

There is now solid evidence that we can intervene to help patient lose weight and decrease the complications that result from obesity. To this end, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) has issued recommendations giving guidance for clinicians about how to approach this issue. Intensive approaches to lifestyle modification with diet and exercise can help patients lose 7% or more of their body weight and have been show to decrease progression from prediabetes to diabetes. Two new medications, lorcaserin and phentermine/topiramate ER, have received Food and Drug Administration approval over the past 2 years as an adjunct to diet for weight loss. Bariatric surgery has emerged as a safe and effective method of weight loss as well.

The AACE guidelines focus on a "complications-centric model" as opposed to a body mass index–driven approach. The guidelines recommend treating obesity to decrease the risk of developing adverse metabolic consequences such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome, and to decrease disability from mechanical comorbidities such as osteoarthritis and obstructive sleep apnea. The AACE guidelines place obese patients into two categories: those that have obesity-related comorbidities and those that do not. The guidelines recommend a graded approach to treatment. All overweight and obese patients should receive therapeutic lifestyle counseling focusing on diet and exercise. Medical or surgical treatment is then recommended for the patients who stand to benefit the most, those with obesity-related comorbidities and those with more severe obesity who have not been able to lose weight using lifestyle modification alone.

In the initial evaluation of overweight and obese patients, the patients should be assessed for cardiometabolic and mechanical complications of obesity, as well as the severity of those complications in order to determine the level of treatment that is appropriate. Patients with obesity-related comorbidities are classified into two groups. The first group includes those with insulin resistance and/or cardiovascular consequences. For this group, evaluation should include waist circumference, fasting, and 2-hour glucose tolerance testing, and lipids, blood pressure, and liver function testing. The second group is composed of people with mechanical consequences including OSA, stress incontinence, orthopedic complications, and chronic pulmonary diseases.

It is important to determine target goals for weight loss to improve mechanical and cardiometabolic complications. Weight loss of 5% or more is enough to affect improvement in metabolic parameters such as glucose and lipids, decrease progression to diabetes, and improve mechanical complications such as knee and hip pain in osteoarthritis. The next step in the approach to treatment is to determine the type and intensity. Therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLC) are important for all patients with diabetes and prediabetes, regardless of risk factors. TLC recommendations include smoking cessation, physical activity, weight management, and healthy eating. Exercise is recommended 5 days/week for more than 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity, to achieve a more than 60% age-related heart rate. The diet recommended reduced saturated fat to less than 7% of calories, reduced cholesterol intake to 200 mg/day, increased fiber to 10-25 g/day, increased plant sterols/stanol esters to 2 g/day, caloric restriction, reduced simple carbohydrates and sugars, increased intake of unsaturated fats, elimination of trans fats, increased marine-based omega-3 ethyl esters, and restriction of alcohol to 20-30 g/day.

For patients with comorbidities and with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or more, consideration should be given to weight-loss medication in addition to lifestyle intervention. The currently approved medications for long-term weight loss include lorcaserin and phentermine/topiramate ER. In the FDA registration studies, the lorcaserin group had an average weight loss of 5.8% after 1 year vs. 2.2% in the placebo group. Phentermine/topiramate ER had an average weight loss of 10% at 1 year vs. 1.2% in the placebo group. These medications are FDA approved as adjuncts to lifestyle modification for the treatment of overweight patients with a BMI greater than 27 kg/m2 with comorbidities and for obese patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 regardless of comorbidities. Both medications improve blood pressure, triglycerides, and insulin sensitivity and prevent the progression to diabetes in patients with diabetes. Bariatric surgery should be considered for those with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or morewith comorbidities, especially if they have failed using other methods.

Once goals are reached, reassess the patient to evaluate for more interventions, if needed. If the targets for improvement in complications were not reached, then the weight loss therapy should become more intense.

Bottom line

The AACE recommendations recognize obesity as a disease and have formulated guidelines using a "complications-centric model." Patients should be assessed for obesity and related complications. Lifestyle counseling should be provided for all overweight and obese individuals, with the addition of weight loss medications for individuals with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or more who have obesity-related comorbidities, and the consideration of bariatric surgery for those with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more with comorbidities.

Reference

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ Comprehensive Diabetes Management Algorithm 2013 Consensus Statement. Published May/June 2013, Endocrine Practice, Vol. 19 (Suppl. 2).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. Dr. McDonald is a second-year resident in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington Memorial Hospital.

Borderline personality disorder is a heritable brain disease

The prevailing view among many psychiatrists and mental health professionals is that borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a “psychological” condition. BPD often is conceptualized as a behavioral consequence of childhood trauma; treatment approaches have emphasized intensive psychotherapeutic modalities, less so biologic interventions. You might not be aware that a large body of research over the past decade provides strong evidence that BPD is a neurobiological illness—a finding that would drastically alter how the disorder should be conceptualized and managed.

Neuropathology underpins the personality disorder

Foremost, BPD must be regarded as a serious, disabling brain disorder, not simply an aberration of personality. In DSM-5, symptoms of BPD are listed as: feelings of abandonment; unstable and intense interpersonal relationships; unstable sense of self; impulsivity; suicidal or self-mutilating behavior; affective instability (dysphoria, irritability, anxiety); chronic feelings of emptiness; intense anger episodes; and transient paranoid or dissociative symptoms. Clearly, these clusters of psychopathological and behavioral symptoms reflect a pervasive brain disorder associated with abnormal neurobiology and neural circuitry that might, at times, stubbornly defy therapeutic intervention.

No wonder that 42 published studies report that, compared with healthy controls, people who have BPD display extensive cortical and subcortical abnormalities in brain structure and function.1 These anomalous patterns have been detected across all 4 available neuroimaging techniques.

Magnetic resonance imaging. MRI studies have revealed the following abnormalities in BPD:

• hypoplasia of the hippocampus, caudate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

• variations in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and subiculum

• smaller-than-normal orbitofrontal cortex (by 24%, compared with healthy controls) and the mid-temporal and left cingulate gyrii (by 26%)

• larger-than-normal volume of the right inferior parietal cortex and the right parahippocampal gyrus

• loss of gray matter in the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices

• an enlarged third cerebral ventricle

• in women, reduced size of the medial temporal lobe and amygdala

• in men, a decreased concentration of gray matter in the anterior cingulate

• reversal of normal right-greater-than-left asymmetry of the orbitofrontal cortex gray matter, reflecting loss of gray matter on the right side

• a lower concentration of gray matter in the rostral/subgenual anterior cingulate cortex

• a smaller frontal lobe.

In an analysis of MRI studies,2 correlation was found between structural brain abnormalities and specific symptoms of BPD, such as impulsivity, suicidality, and aggression. These findings might someday guide personalized interventions—for example, using neurostimulation techniques such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep brain stimulation—to modulate the activity of a given region of the brain (depending on which symptom is most prominent or disabling).

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In BPD, MRS studies reveal:

• compared with controls, a higher glutamate level in the anterior cingulate cortex

• reduced levels of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA; found in neurons) and creatinine in the left amygdala

• a reduction (on average, 19%) in the NAA concentration in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging. From fMRI studies, there is evidence in BPD of:

• greater activation of the amygdala and prolonged return to baseline

• increased functional connectivity in the left frontopolar cortex and left insula

• decreased connectivity in the left cuneus and left inferior parietal and the right middle temporal lobes

• marked frontal hypometabolism

• hypermetabolism in the motor cortex, medial and anterior cingulate, and occipital and temporal poles

• lower connectivity between the amygdala during a neutral stimulus

• higher connectivity between the amygdala during fear stimulus

• higher connectivity between the amygdala during fear stimulus

• deactivation of the opioid system in the left nucleus accumbens, hypothalamus, and hippocampus

• hyperactivation of the left medial prefrontal cortex during social exclusion

• more mistakes made in differentiating an emotional and a neutral facial expression.

Diffusion tensor imaging. DTI white-matter integrity studies of BPD show:

• a bilateral decrease in fractional anisotropy (FA) in frontal, uncinated, and occipitalfrontal fasciculi

• a decrease in FA in the genu and rostrum of the corpus callosum

• a decrease in inter-hemispheric connectivity between right and left anterior cigulate cortices.

Genetic Studies

There is substantial scientific evidence that BPD is highly heritable—a finding that suggests that brain abnormalities of this disorder are a consequence of genes involved in brain development (similar to what is known about schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism).

A systematic review of the heritability of BPD examined 59 published studies that were categorized into 12 family studies, 18 twin studies, 24 association studies, and 5 gene-environment interaction studies.3 The authors concluded that BPD has a strong genetic component, although there also is evidence of gene-environment (G.E) interactions (ie, how nature and nurture influence each other).

The G.E interaction model appears to be consistent with the theory that expression of plasticity genes is modified by childhood experiences and environment, such as physical or sexual abuse. Some studies have found evidence of hypermethylation in BPD, which can exert epigenetic effects. Childhood abuse might, therefore, disrupt certain neuroplasticity genes, culminating in morphological, neurochemical, metabolic, and white-matter aberrations—leading to pathological behavioral patterns identified as BPD.

The neuropsychiatric basis of BPD must guide treatment

There is no such thing as a purely psychological disorder: Invariably, it is an abnormality of brain circuits that disrupts normal development of emotions, thought, behavior, and social cognition. BPD is an exemplar of such neuropsychiatric illness, and treatment should support psychotherapeutic approaches to mend the mind at the same time it moves aggressively to repair the brain.

1. McKenzie CE, Nasrallah HA. Neuroimaging abnormalities in borderline personality disorder: MRI, MRS, fMRI and DTI findings. Poster presented at: 52nd Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 8-12, 2013; Hollywood, FL.

2. McKenzie CE, Nasrallah HA. Clinical symptoms of borderline personality disorder are associated with cortical and subcortical abnormalities on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Poster presented at: 26th Annual Meeting of the U.S. Psychiatric and Mental Health Congress; September 31-October 3, 2013; Las Vegas, NV.

3. Amad A, Ramoz N, Thomas P, et al. Genetics of borderline personality disorder: systematic review and proposal of an integrative model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;40C:6-19.

The prevailing view among many psychiatrists and mental health professionals is that borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a “psychological” condition. BPD often is conceptualized as a behavioral consequence of childhood trauma; treatment approaches have emphasized intensive psychotherapeutic modalities, less so biologic interventions. You might not be aware that a large body of research over the past decade provides strong evidence that BPD is a neurobiological illness—a finding that would drastically alter how the disorder should be conceptualized and managed.

Neuropathology underpins the personality disorder

Foremost, BPD must be regarded as a serious, disabling brain disorder, not simply an aberration of personality. In DSM-5, symptoms of BPD are listed as: feelings of abandonment; unstable and intense interpersonal relationships; unstable sense of self; impulsivity; suicidal or self-mutilating behavior; affective instability (dysphoria, irritability, anxiety); chronic feelings of emptiness; intense anger episodes; and transient paranoid or dissociative symptoms. Clearly, these clusters of psychopathological and behavioral symptoms reflect a pervasive brain disorder associated with abnormal neurobiology and neural circuitry that might, at times, stubbornly defy therapeutic intervention.

No wonder that 42 published studies report that, compared with healthy controls, people who have BPD display extensive cortical and subcortical abnormalities in brain structure and function.1 These anomalous patterns have been detected across all 4 available neuroimaging techniques.

Magnetic resonance imaging. MRI studies have revealed the following abnormalities in BPD:

• hypoplasia of the hippocampus, caudate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

• variations in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and subiculum

• smaller-than-normal orbitofrontal cortex (by 24%, compared with healthy controls) and the mid-temporal and left cingulate gyrii (by 26%)

• larger-than-normal volume of the right inferior parietal cortex and the right parahippocampal gyrus

• loss of gray matter in the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices

• an enlarged third cerebral ventricle

• in women, reduced size of the medial temporal lobe and amygdala

• in men, a decreased concentration of gray matter in the anterior cingulate

• reversal of normal right-greater-than-left asymmetry of the orbitofrontal cortex gray matter, reflecting loss of gray matter on the right side

• a lower concentration of gray matter in the rostral/subgenual anterior cingulate cortex

• a smaller frontal lobe.

In an analysis of MRI studies,2 correlation was found between structural brain abnormalities and specific symptoms of BPD, such as impulsivity, suicidality, and aggression. These findings might someday guide personalized interventions—for example, using neurostimulation techniques such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep brain stimulation—to modulate the activity of a given region of the brain (depending on which symptom is most prominent or disabling).

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In BPD, MRS studies reveal:

• compared with controls, a higher glutamate level in the anterior cingulate cortex

• reduced levels of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA; found in neurons) and creatinine in the left amygdala

• a reduction (on average, 19%) in the NAA concentration in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging. From fMRI studies, there is evidence in BPD of:

• greater activation of the amygdala and prolonged return to baseline

• increased functional connectivity in the left frontopolar cortex and left insula

• decreased connectivity in the left cuneus and left inferior parietal and the right middle temporal lobes

• marked frontal hypometabolism

• hypermetabolism in the motor cortex, medial and anterior cingulate, and occipital and temporal poles

• lower connectivity between the amygdala during a neutral stimulus

• higher connectivity between the amygdala during fear stimulus

• higher connectivity between the amygdala during fear stimulus

• deactivation of the opioid system in the left nucleus accumbens, hypothalamus, and hippocampus

• hyperactivation of the left medial prefrontal cortex during social exclusion

• more mistakes made in differentiating an emotional and a neutral facial expression.

Diffusion tensor imaging. DTI white-matter integrity studies of BPD show:

• a bilateral decrease in fractional anisotropy (FA) in frontal, uncinated, and occipitalfrontal fasciculi

• a decrease in FA in the genu and rostrum of the corpus callosum

• a decrease in inter-hemispheric connectivity between right and left anterior cigulate cortices.

Genetic Studies

There is substantial scientific evidence that BPD is highly heritable—a finding that suggests that brain abnormalities of this disorder are a consequence of genes involved in brain development (similar to what is known about schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism).

A systematic review of the heritability of BPD examined 59 published studies that were categorized into 12 family studies, 18 twin studies, 24 association studies, and 5 gene-environment interaction studies.3 The authors concluded that BPD has a strong genetic component, although there also is evidence of gene-environment (G.E) interactions (ie, how nature and nurture influence each other).

The G.E interaction model appears to be consistent with the theory that expression of plasticity genes is modified by childhood experiences and environment, such as physical or sexual abuse. Some studies have found evidence of hypermethylation in BPD, which can exert epigenetic effects. Childhood abuse might, therefore, disrupt certain neuroplasticity genes, culminating in morphological, neurochemical, metabolic, and white-matter aberrations—leading to pathological behavioral patterns identified as BPD.

The neuropsychiatric basis of BPD must guide treatment

There is no such thing as a purely psychological disorder: Invariably, it is an abnormality of brain circuits that disrupts normal development of emotions, thought, behavior, and social cognition. BPD is an exemplar of such neuropsychiatric illness, and treatment should support psychotherapeutic approaches to mend the mind at the same time it moves aggressively to repair the brain.

The prevailing view among many psychiatrists and mental health professionals is that borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a “psychological” condition. BPD often is conceptualized as a behavioral consequence of childhood trauma; treatment approaches have emphasized intensive psychotherapeutic modalities, less so biologic interventions. You might not be aware that a large body of research over the past decade provides strong evidence that BPD is a neurobiological illness—a finding that would drastically alter how the disorder should be conceptualized and managed.

Neuropathology underpins the personality disorder

Foremost, BPD must be regarded as a serious, disabling brain disorder, not simply an aberration of personality. In DSM-5, symptoms of BPD are listed as: feelings of abandonment; unstable and intense interpersonal relationships; unstable sense of self; impulsivity; suicidal or self-mutilating behavior; affective instability (dysphoria, irritability, anxiety); chronic feelings of emptiness; intense anger episodes; and transient paranoid or dissociative symptoms. Clearly, these clusters of psychopathological and behavioral symptoms reflect a pervasive brain disorder associated with abnormal neurobiology and neural circuitry that might, at times, stubbornly defy therapeutic intervention.

No wonder that 42 published studies report that, compared with healthy controls, people who have BPD display extensive cortical and subcortical abnormalities in brain structure and function.1 These anomalous patterns have been detected across all 4 available neuroimaging techniques.

Magnetic resonance imaging. MRI studies have revealed the following abnormalities in BPD:

• hypoplasia of the hippocampus, caudate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

• variations in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and subiculum

• smaller-than-normal orbitofrontal cortex (by 24%, compared with healthy controls) and the mid-temporal and left cingulate gyrii (by 26%)

• larger-than-normal volume of the right inferior parietal cortex and the right parahippocampal gyrus

• loss of gray matter in the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices

• an enlarged third cerebral ventricle

• in women, reduced size of the medial temporal lobe and amygdala

• in men, a decreased concentration of gray matter in the anterior cingulate

• reversal of normal right-greater-than-left asymmetry of the orbitofrontal cortex gray matter, reflecting loss of gray matter on the right side

• a lower concentration of gray matter in the rostral/subgenual anterior cingulate cortex

• a smaller frontal lobe.

In an analysis of MRI studies,2 correlation was found between structural brain abnormalities and specific symptoms of BPD, such as impulsivity, suicidality, and aggression. These findings might someday guide personalized interventions—for example, using neurostimulation techniques such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep brain stimulation—to modulate the activity of a given region of the brain (depending on which symptom is most prominent or disabling).

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In BPD, MRS studies reveal:

• compared with controls, a higher glutamate level in the anterior cingulate cortex

• reduced levels of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA; found in neurons) and creatinine in the left amygdala

• a reduction (on average, 19%) in the NAA concentration in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging. From fMRI studies, there is evidence in BPD of:

• greater activation of the amygdala and prolonged return to baseline

• increased functional connectivity in the left frontopolar cortex and left insula

• decreased connectivity in the left cuneus and left inferior parietal and the right middle temporal lobes

• marked frontal hypometabolism

• hypermetabolism in the motor cortex, medial and anterior cingulate, and occipital and temporal poles

• lower connectivity between the amygdala during a neutral stimulus

• higher connectivity between the amygdala during fear stimulus

• higher connectivity between the amygdala during fear stimulus

• deactivation of the opioid system in the left nucleus accumbens, hypothalamus, and hippocampus

• hyperactivation of the left medial prefrontal cortex during social exclusion

• more mistakes made in differentiating an emotional and a neutral facial expression.

Diffusion tensor imaging. DTI white-matter integrity studies of BPD show:

• a bilateral decrease in fractional anisotropy (FA) in frontal, uncinated, and occipitalfrontal fasciculi

• a decrease in FA in the genu and rostrum of the corpus callosum

• a decrease in inter-hemispheric connectivity between right and left anterior cigulate cortices.

Genetic Studies

There is substantial scientific evidence that BPD is highly heritable—a finding that suggests that brain abnormalities of this disorder are a consequence of genes involved in brain development (similar to what is known about schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism).

A systematic review of the heritability of BPD examined 59 published studies that were categorized into 12 family studies, 18 twin studies, 24 association studies, and 5 gene-environment interaction studies.3 The authors concluded that BPD has a strong genetic component, although there also is evidence of gene-environment (G.E) interactions (ie, how nature and nurture influence each other).

The G.E interaction model appears to be consistent with the theory that expression of plasticity genes is modified by childhood experiences and environment, such as physical or sexual abuse. Some studies have found evidence of hypermethylation in BPD, which can exert epigenetic effects. Childhood abuse might, therefore, disrupt certain neuroplasticity genes, culminating in morphological, neurochemical, metabolic, and white-matter aberrations—leading to pathological behavioral patterns identified as BPD.

The neuropsychiatric basis of BPD must guide treatment

There is no such thing as a purely psychological disorder: Invariably, it is an abnormality of brain circuits that disrupts normal development of emotions, thought, behavior, and social cognition. BPD is an exemplar of such neuropsychiatric illness, and treatment should support psychotherapeutic approaches to mend the mind at the same time it moves aggressively to repair the brain.

1. McKenzie CE, Nasrallah HA. Neuroimaging abnormalities in borderline personality disorder: MRI, MRS, fMRI and DTI findings. Poster presented at: 52nd Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 8-12, 2013; Hollywood, FL.

2. McKenzie CE, Nasrallah HA. Clinical symptoms of borderline personality disorder are associated with cortical and subcortical abnormalities on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Poster presented at: 26th Annual Meeting of the U.S. Psychiatric and Mental Health Congress; September 31-October 3, 2013; Las Vegas, NV.

3. Amad A, Ramoz N, Thomas P, et al. Genetics of borderline personality disorder: systematic review and proposal of an integrative model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;40C:6-19.

1. McKenzie CE, Nasrallah HA. Neuroimaging abnormalities in borderline personality disorder: MRI, MRS, fMRI and DTI findings. Poster presented at: 52nd Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 8-12, 2013; Hollywood, FL.

2. McKenzie CE, Nasrallah HA. Clinical symptoms of borderline personality disorder are associated with cortical and subcortical abnormalities on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Poster presented at: 26th Annual Meeting of the U.S. Psychiatric and Mental Health Congress; September 31-October 3, 2013; Las Vegas, NV.

3. Amad A, Ramoz N, Thomas P, et al. Genetics of borderline personality disorder: systematic review and proposal of an integrative model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;40C:6-19.

Video glasses can curb patient anxiety

Credit: CDC

SAN DIEGO—Watching videos through special glasses can calm patients undergoing a biopsy or other minimally invasive treatment, according to research presented at the Society of Interventional Radiology’s 39th Annual Scientific Meeting.

Researchers have explored strategies other than medication to reduce anxiety in these patients, including having patients listen to music or undergo hypnosis. But these methods have had modest benefits.

“Our study—the first of its kind for interventional radiology treatments—puts a spin on using modern technology to provide a safe, potentially cost-effective strategy of reducing anxiety, which can help and improve patient care,” said David L. Waldman, MD, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

“Whether they were watching a children’s movie or a nature show, patients wearing video glasses were successful at tuning out their surroundings. It’s an effective distraction technique that helps focus the individual’s attention away from the treatment.”

The study involved 49 patients (33 men and 16 women, ages 18-87) who were undergoing an outpatient interventional radiology treatment, such as a biopsy or placement of a catheter in the arm or chest to receive medication for treating cancer or infection.

Twenty-five of the patients donned video glasses prior to undergoing the treatment, and 24 did not. The video viewers chose from 20 videos, none of which were violent.

All of the patients filled out a standard 20-question test called the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Form Y before and after the procedure to assess their level of anxiety.

Patients who wore the video glasses were 18.1% less anxious after the treatment than they were before, while those who didn’t wear video glasses were 7.5% less anxious afterward.

And the presence of the video glasses did not bother either the patient or the doctor, Dr Waldman said.

The glasses had no significant effect on blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, pain, procedure time, or the amount of sedation or pain medication used.

“Patients told us the video glasses really helped calm them down and took their mind off the treatment, and we now offer video glasses to help distract patients from medical treatment going on mere inches away,” Dr Waldman said. “It is really comforting for patients, especially the ones who tend to be more nervous.

Dr Waldman and his colleagues presented these results at the meeting as abstract 126. ![]()

Credit: CDC

SAN DIEGO—Watching videos through special glasses can calm patients undergoing a biopsy or other minimally invasive treatment, according to research presented at the Society of Interventional Radiology’s 39th Annual Scientific Meeting.

Researchers have explored strategies other than medication to reduce anxiety in these patients, including having patients listen to music or undergo hypnosis. But these methods have had modest benefits.

“Our study—the first of its kind for interventional radiology treatments—puts a spin on using modern technology to provide a safe, potentially cost-effective strategy of reducing anxiety, which can help and improve patient care,” said David L. Waldman, MD, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

“Whether they were watching a children’s movie or a nature show, patients wearing video glasses were successful at tuning out their surroundings. It’s an effective distraction technique that helps focus the individual’s attention away from the treatment.”

The study involved 49 patients (33 men and 16 women, ages 18-87) who were undergoing an outpatient interventional radiology treatment, such as a biopsy or placement of a catheter in the arm or chest to receive medication for treating cancer or infection.

Twenty-five of the patients donned video glasses prior to undergoing the treatment, and 24 did not. The video viewers chose from 20 videos, none of which were violent.

All of the patients filled out a standard 20-question test called the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Form Y before and after the procedure to assess their level of anxiety.

Patients who wore the video glasses were 18.1% less anxious after the treatment than they were before, while those who didn’t wear video glasses were 7.5% less anxious afterward.

And the presence of the video glasses did not bother either the patient or the doctor, Dr Waldman said.

The glasses had no significant effect on blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, pain, procedure time, or the amount of sedation or pain medication used.

“Patients told us the video glasses really helped calm them down and took their mind off the treatment, and we now offer video glasses to help distract patients from medical treatment going on mere inches away,” Dr Waldman said. “It is really comforting for patients, especially the ones who tend to be more nervous.

Dr Waldman and his colleagues presented these results at the meeting as abstract 126. ![]()

Credit: CDC

SAN DIEGO—Watching videos through special glasses can calm patients undergoing a biopsy or other minimally invasive treatment, according to research presented at the Society of Interventional Radiology’s 39th Annual Scientific Meeting.

Researchers have explored strategies other than medication to reduce anxiety in these patients, including having patients listen to music or undergo hypnosis. But these methods have had modest benefits.

“Our study—the first of its kind for interventional radiology treatments—puts a spin on using modern technology to provide a safe, potentially cost-effective strategy of reducing anxiety, which can help and improve patient care,” said David L. Waldman, MD, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

“Whether they were watching a children’s movie or a nature show, patients wearing video glasses were successful at tuning out their surroundings. It’s an effective distraction technique that helps focus the individual’s attention away from the treatment.”

The study involved 49 patients (33 men and 16 women, ages 18-87) who were undergoing an outpatient interventional radiology treatment, such as a biopsy or placement of a catheter in the arm or chest to receive medication for treating cancer or infection.

Twenty-five of the patients donned video glasses prior to undergoing the treatment, and 24 did not. The video viewers chose from 20 videos, none of which were violent.

All of the patients filled out a standard 20-question test called the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Form Y before and after the procedure to assess their level of anxiety.

Patients who wore the video glasses were 18.1% less anxious after the treatment than they were before, while those who didn’t wear video glasses were 7.5% less anxious afterward.

And the presence of the video glasses did not bother either the patient or the doctor, Dr Waldman said.

The glasses had no significant effect on blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, pain, procedure time, or the amount of sedation or pain medication used.

“Patients told us the video glasses really helped calm them down and took their mind off the treatment, and we now offer video glasses to help distract patients from medical treatment going on mere inches away,” Dr Waldman said. “It is really comforting for patients, especially the ones who tend to be more nervous.

Dr Waldman and his colleagues presented these results at the meeting as abstract 126. ![]()

Vorinostat demonstrates antitumor activity in FL

Single-agent treatment with the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat can be effective in certain patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

In the phase 2 study, vorinostat prompted a 49% overall response rate among 39 patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL).

However, none of the 4 patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) achieved a response.

Michinori Ogura, MD, PhD, of Nagoya Daini Red Cross Hospital in Japan, and his colleagues set out to analyze the effects of vorinostat in 56 patients with indolent NHL. Six patients were excluded from the final analysis, as their diseases could not be classified.

Thirty-nine patients had FL, 4 had extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) of MALT type, 4 had MCL, 2 had small B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (NOS), and 1 had small lymphocytic lymphoma.

The median age was 60 years (range, 33-75), and the median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-4). These therapies included rituximab (n=40), alkylating agents (n=7), purine analogs (n=5), and radioimmunotherapy (n=3).

The patients received vorinostat for a median of 8 months. The planned dosage was 200 mg twice daily for 14 consecutive days in a 21-day cycle.

At the first data cutoff point (1 year from the last patient’s enrollment), 18 patients remained on treatment. Thirty-eight had discontinued due to disease progression (n=25), drug-related adverse events (n=9), or withdrawn consent (n=4).

The overall response rate was 49% among FL patients. Ten percent (n=4) achieved a complete response, 8% (n=3) achieved an unconfirmed complete response, and 31% (n=12) achieved a partial response.

None of the patients with MCL responded, but 3 of the 7 (43%) patients with other indolent NHLs achieved a response.

That included 2 patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS and 1 with extranodal MZL of MALT type. One of the patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS achieved a complete response.

Approximately 81% of all 56 patients remained alive at 2 years after the last patients had enrolled (the second data cutoff point).

At that point, the median overall survival had not been reached. And the median progression-free survival was 26 months among the FL patients who responded.

There were no treatment-related deaths. The most common drug-related events (in all 56 patients) were thrombocytopenia (93%), diarrhea (68%), neutropenia (68%), decreased appetite (63%), nausea (61%), leukopenia (55%), and fatigue (52%).

Eighty percent of patients (n=45) experienced grade 3/4 adverse events, the most common of which were thrombocytopenia (23% grade 3; 25% grade 4) and neutropenia (36% grade 3; 5% grade 4).

However, all of the patients with thrombocytopenia or neutropenia recovered after they received adequate supportive care and their vorinostat dose was reduced or treatment was interrupted or discontinued.

Taking these results together, the researchers concluded that vorinostat offers sustained antitumor activity and has an acceptable safety profile for patients with relapsed or refractory FL. The team noted, however, that because this was a single-arm study with limited data, a comparative study is needed. ![]()

Single-agent treatment with the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat can be effective in certain patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

In the phase 2 study, vorinostat prompted a 49% overall response rate among 39 patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL).

However, none of the 4 patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) achieved a response.

Michinori Ogura, MD, PhD, of Nagoya Daini Red Cross Hospital in Japan, and his colleagues set out to analyze the effects of vorinostat in 56 patients with indolent NHL. Six patients were excluded from the final analysis, as their diseases could not be classified.

Thirty-nine patients had FL, 4 had extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) of MALT type, 4 had MCL, 2 had small B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (NOS), and 1 had small lymphocytic lymphoma.

The median age was 60 years (range, 33-75), and the median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-4). These therapies included rituximab (n=40), alkylating agents (n=7), purine analogs (n=5), and radioimmunotherapy (n=3).

The patients received vorinostat for a median of 8 months. The planned dosage was 200 mg twice daily for 14 consecutive days in a 21-day cycle.

At the first data cutoff point (1 year from the last patient’s enrollment), 18 patients remained on treatment. Thirty-eight had discontinued due to disease progression (n=25), drug-related adverse events (n=9), or withdrawn consent (n=4).

The overall response rate was 49% among FL patients. Ten percent (n=4) achieved a complete response, 8% (n=3) achieved an unconfirmed complete response, and 31% (n=12) achieved a partial response.

None of the patients with MCL responded, but 3 of the 7 (43%) patients with other indolent NHLs achieved a response.

That included 2 patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS and 1 with extranodal MZL of MALT type. One of the patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS achieved a complete response.

Approximately 81% of all 56 patients remained alive at 2 years after the last patients had enrolled (the second data cutoff point).

At that point, the median overall survival had not been reached. And the median progression-free survival was 26 months among the FL patients who responded.

There were no treatment-related deaths. The most common drug-related events (in all 56 patients) were thrombocytopenia (93%), diarrhea (68%), neutropenia (68%), decreased appetite (63%), nausea (61%), leukopenia (55%), and fatigue (52%).

Eighty percent of patients (n=45) experienced grade 3/4 adverse events, the most common of which were thrombocytopenia (23% grade 3; 25% grade 4) and neutropenia (36% grade 3; 5% grade 4).

However, all of the patients with thrombocytopenia or neutropenia recovered after they received adequate supportive care and their vorinostat dose was reduced or treatment was interrupted or discontinued.

Taking these results together, the researchers concluded that vorinostat offers sustained antitumor activity and has an acceptable safety profile for patients with relapsed or refractory FL. The team noted, however, that because this was a single-arm study with limited data, a comparative study is needed. ![]()

Single-agent treatment with the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat can be effective in certain patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

In the phase 2 study, vorinostat prompted a 49% overall response rate among 39 patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL).

However, none of the 4 patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) achieved a response.

Michinori Ogura, MD, PhD, of Nagoya Daini Red Cross Hospital in Japan, and his colleagues set out to analyze the effects of vorinostat in 56 patients with indolent NHL. Six patients were excluded from the final analysis, as their diseases could not be classified.

Thirty-nine patients had FL, 4 had extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) of MALT type, 4 had MCL, 2 had small B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (NOS), and 1 had small lymphocytic lymphoma.

The median age was 60 years (range, 33-75), and the median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-4). These therapies included rituximab (n=40), alkylating agents (n=7), purine analogs (n=5), and radioimmunotherapy (n=3).

The patients received vorinostat for a median of 8 months. The planned dosage was 200 mg twice daily for 14 consecutive days in a 21-day cycle.

At the first data cutoff point (1 year from the last patient’s enrollment), 18 patients remained on treatment. Thirty-eight had discontinued due to disease progression (n=25), drug-related adverse events (n=9), or withdrawn consent (n=4).

The overall response rate was 49% among FL patients. Ten percent (n=4) achieved a complete response, 8% (n=3) achieved an unconfirmed complete response, and 31% (n=12) achieved a partial response.

None of the patients with MCL responded, but 3 of the 7 (43%) patients with other indolent NHLs achieved a response.

That included 2 patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS and 1 with extranodal MZL of MALT type. One of the patients with small B-cell lymphoma NOS achieved a complete response.

Approximately 81% of all 56 patients remained alive at 2 years after the last patients had enrolled (the second data cutoff point).

At that point, the median overall survival had not been reached. And the median progression-free survival was 26 months among the FL patients who responded.

There were no treatment-related deaths. The most common drug-related events (in all 56 patients) were thrombocytopenia (93%), diarrhea (68%), neutropenia (68%), decreased appetite (63%), nausea (61%), leukopenia (55%), and fatigue (52%).

Eighty percent of patients (n=45) experienced grade 3/4 adverse events, the most common of which were thrombocytopenia (23% grade 3; 25% grade 4) and neutropenia (36% grade 3; 5% grade 4).

However, all of the patients with thrombocytopenia or neutropenia recovered after they received adequate supportive care and their vorinostat dose was reduced or treatment was interrupted or discontinued.

Taking these results together, the researchers concluded that vorinostat offers sustained antitumor activity and has an acceptable safety profile for patients with relapsed or refractory FL. The team noted, however, that because this was a single-arm study with limited data, a comparative study is needed. ![]()

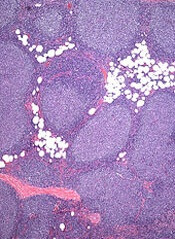

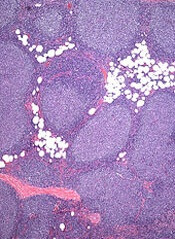

Immunotherapy shows promise in CBCL

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Credit: Leszek Woźniak

& Krzysztof W. Zieliński

An immunotherapeutic agent can confer clinical benefit in patients with relapsed cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), results of a small phase 2 study suggest.

The therapy, TG1042, is human adenovirus type 5 engineered to express interferon-gamma.

Repeat injections of TG1042 elicited responses in 11 of 12 evaluable patients, with complete responses in 7.

All 13 of the patients enrolled on the study experienced an adverse event that may have been related to TG1042, but most were grade 1 or 2 in severity.

“Intralesional TG1042 therapy is well-tolerated and results in lasting tumor regressions,” said study author Reinhard Dummer, MD, of the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

He and his colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE. The study was sponsored by Transgene SA, makers of TG1042.

The trial consisted of 13 patients with primary CBCL, including primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma other than leg type, and T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma.

Patients were required to have either relapsed or active disease after at least 1 first-line treatment.

The patients received intralesional injections of TG1042 at 5 x 1010 viral particles per lesion. They could receive injections in up to 6 lesions, which were treated simultaneously on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 4-week cycle.

Patients did not receive treatment during the fourth week. At the end of the cycle, the researchers evaluated tumors for response.

If patients’ disease did not progress, they could receive an additional cycle, up to a maximum of 4. If patients responded to treatment and their lesions disappeared, they were eligible to receive a second series of injections in untreated lesions.

Of the 13 patients treated, 12 were evaluable for response. Eleven of the patients (85%) achieved an objective response—7 complete responses and 4 partial responses. One patient had stable disease.

All reviewed skin biopsies showed that lesions improved after treatment, with a decrease of the lymphoid infiltrate.

The median time to first objective response was 3.2 months (rage, 1-17.5 months). Among complete responders, the median time to response was 4.3 months (range, 1.4-17.5 months).

The median time to progression was 23.5 months (range, 6.5-26.4+ months).

All 13 patients were included in the safety evaluation, and all experienced 1 or more adverse events that were considered possibly or probably related to the treatment.

One patient discontinued treatment due to influenza-like illness, pyrexia, headache, and skin blisters that were possibly related to TG1042.

Another patient had grade 3 increased lipase, but this was thought to be unrelated to TG1042. And it resolved without treatment.

All other adverse events were grade 1 or 2 in nature. They included fatigue, headache, pyrexia, chills, influenza-like illness, injection site irritation, injection site erythema, and injection site pain.

All of these reactions resolved after treatment discontinuation. ![]()

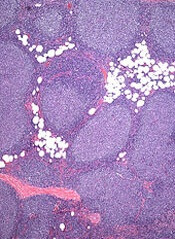

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Credit: Leszek Woźniak

& Krzysztof W. Zieliński

An immunotherapeutic agent can confer clinical benefit in patients with relapsed cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), results of a small phase 2 study suggest.

The therapy, TG1042, is human adenovirus type 5 engineered to express interferon-gamma.

Repeat injections of TG1042 elicited responses in 11 of 12 evaluable patients, with complete responses in 7.

All 13 of the patients enrolled on the study experienced an adverse event that may have been related to TG1042, but most were grade 1 or 2 in severity.

“Intralesional TG1042 therapy is well-tolerated and results in lasting tumor regressions,” said study author Reinhard Dummer, MD, of the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

He and his colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE. The study was sponsored by Transgene SA, makers of TG1042.

The trial consisted of 13 patients with primary CBCL, including primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma other than leg type, and T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma.

Patients were required to have either relapsed or active disease after at least 1 first-line treatment.

The patients received intralesional injections of TG1042 at 5 x 1010 viral particles per lesion. They could receive injections in up to 6 lesions, which were treated simultaneously on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 4-week cycle.

Patients did not receive treatment during the fourth week. At the end of the cycle, the researchers evaluated tumors for response.

If patients’ disease did not progress, they could receive an additional cycle, up to a maximum of 4. If patients responded to treatment and their lesions disappeared, they were eligible to receive a second series of injections in untreated lesions.

Of the 13 patients treated, 12 were evaluable for response. Eleven of the patients (85%) achieved an objective response—7 complete responses and 4 partial responses. One patient had stable disease.

All reviewed skin biopsies showed that lesions improved after treatment, with a decrease of the lymphoid infiltrate.

The median time to first objective response was 3.2 months (rage, 1-17.5 months). Among complete responders, the median time to response was 4.3 months (range, 1.4-17.5 months).

The median time to progression was 23.5 months (range, 6.5-26.4+ months).

All 13 patients were included in the safety evaluation, and all experienced 1 or more adverse events that were considered possibly or probably related to the treatment.

One patient discontinued treatment due to influenza-like illness, pyrexia, headache, and skin blisters that were possibly related to TG1042.

Another patient had grade 3 increased lipase, but this was thought to be unrelated to TG1042. And it resolved without treatment.

All other adverse events were grade 1 or 2 in nature. They included fatigue, headache, pyrexia, chills, influenza-like illness, injection site irritation, injection site erythema, and injection site pain.

All of these reactions resolved after treatment discontinuation. ![]()

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Credit: Leszek Woźniak

& Krzysztof W. Zieliński

An immunotherapeutic agent can confer clinical benefit in patients with relapsed cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), results of a small phase 2 study suggest.

The therapy, TG1042, is human adenovirus type 5 engineered to express interferon-gamma.

Repeat injections of TG1042 elicited responses in 11 of 12 evaluable patients, with complete responses in 7.

All 13 of the patients enrolled on the study experienced an adverse event that may have been related to TG1042, but most were grade 1 or 2 in severity.

“Intralesional TG1042 therapy is well-tolerated and results in lasting tumor regressions,” said study author Reinhard Dummer, MD, of the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

He and his colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE. The study was sponsored by Transgene SA, makers of TG1042.