User login

Predicting risk of death in childhood cancer survivors

Logan Tuttle

Factors other than cancer treatment or chronic health conditions can influence the risk of death among survivors of childhood cancers, according to a study published in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

The researchers found an increased risk of death among cancer survivors who rarely exercised, were underweight, visited the doctor 5 or more times a year, considered themselves in “fair” or “poor” health, and had concerns about their future health.

Cheryl Cox, PhD, of the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and her colleagues conducted this research using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.

The team compared 7162 childhood cancer survivors to 445 subjects who survived childhood cancer but ultimately died from causes other than cancer or non-health-related events (such as accidents).

The researchers matched subjects according to their primary diagnosis, age at the time of baseline questionnaire, and the time from diagnosis to baseline questionnaire.

Among the 445 subjects who died, the median age at death was 37.6 years. Malignant neoplasms (42%), cardiac conditions (20%), and pulmonary conditions (7%) caused the most deaths.

Subjects who died were slightly older than living subjects and more often of black race (vs white, Hispanic, or “other”). They were less likely to have a post-high school education or to be married. And they were more likely to have a household income below $20,000 or have an existing grade 3 or 4 chronic health condition.

When the researchers adjusted their analyses for sociodemographic characteristics, exposure to chemotherapy and/or radiation, and the number and severity of chronic health conditions, they identified a number of factors associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality.

One of these factors was a lack of exercise—specifically, not exercising at all (odds ratio [OR]=1.72, P<0.001) or exercising 1 to 2 days a week (OR=1.65, P=0.004), compared to exercising 3 or more days a week.

On the other hand, being overweight or obese did not significantly increase a subject’s risk of death, but being underweight did (OR=2.58, P<0.001).

As one might expect, increased use of medical care was associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Subjects who reported 5 to 6 doctor visits per year had twice the risk of death as subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=2.07, P<0.001). And subjects who reported more than 20 annual doctor visits had a nearly 4-fold greater risk of death than subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=3.87, P<0.001).

Similarly, subjects had an increased risk of mortality if they described their general health as being “poor” or “fair” (OR=1.98, P<0.001). And being “concerned” or “very concerned” about future health was associated with an increased risk of mortality as well (OR=1.54, P=0.01)

On the other hand, smoking did not have a significant impact on the risk of death, and alcohol consumption appeared to have a positive impact on life expectancy.

Subjects who reported consuming 5 or more drinks per month had a lower risk of mortality than subjects who said they did not consume alcohol at all (OR=0.75, P=0.05).

Dr Cox and her colleagues said this research has revealed novel predictors of mortality not associated with a cancer survivor’s primary disease, treatment, or late effects. And continued observation could point to interventions for reducing the risk of death in these patients. ![]()

Logan Tuttle

Factors other than cancer treatment or chronic health conditions can influence the risk of death among survivors of childhood cancers, according to a study published in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

The researchers found an increased risk of death among cancer survivors who rarely exercised, were underweight, visited the doctor 5 or more times a year, considered themselves in “fair” or “poor” health, and had concerns about their future health.

Cheryl Cox, PhD, of the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and her colleagues conducted this research using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.

The team compared 7162 childhood cancer survivors to 445 subjects who survived childhood cancer but ultimately died from causes other than cancer or non-health-related events (such as accidents).

The researchers matched subjects according to their primary diagnosis, age at the time of baseline questionnaire, and the time from diagnosis to baseline questionnaire.

Among the 445 subjects who died, the median age at death was 37.6 years. Malignant neoplasms (42%), cardiac conditions (20%), and pulmonary conditions (7%) caused the most deaths.

Subjects who died were slightly older than living subjects and more often of black race (vs white, Hispanic, or “other”). They were less likely to have a post-high school education or to be married. And they were more likely to have a household income below $20,000 or have an existing grade 3 or 4 chronic health condition.

When the researchers adjusted their analyses for sociodemographic characteristics, exposure to chemotherapy and/or radiation, and the number and severity of chronic health conditions, they identified a number of factors associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality.

One of these factors was a lack of exercise—specifically, not exercising at all (odds ratio [OR]=1.72, P<0.001) or exercising 1 to 2 days a week (OR=1.65, P=0.004), compared to exercising 3 or more days a week.

On the other hand, being overweight or obese did not significantly increase a subject’s risk of death, but being underweight did (OR=2.58, P<0.001).

As one might expect, increased use of medical care was associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Subjects who reported 5 to 6 doctor visits per year had twice the risk of death as subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=2.07, P<0.001). And subjects who reported more than 20 annual doctor visits had a nearly 4-fold greater risk of death than subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=3.87, P<0.001).

Similarly, subjects had an increased risk of mortality if they described their general health as being “poor” or “fair” (OR=1.98, P<0.001). And being “concerned” or “very concerned” about future health was associated with an increased risk of mortality as well (OR=1.54, P=0.01)

On the other hand, smoking did not have a significant impact on the risk of death, and alcohol consumption appeared to have a positive impact on life expectancy.

Subjects who reported consuming 5 or more drinks per month had a lower risk of mortality than subjects who said they did not consume alcohol at all (OR=0.75, P=0.05).

Dr Cox and her colleagues said this research has revealed novel predictors of mortality not associated with a cancer survivor’s primary disease, treatment, or late effects. And continued observation could point to interventions for reducing the risk of death in these patients. ![]()

Logan Tuttle

Factors other than cancer treatment or chronic health conditions can influence the risk of death among survivors of childhood cancers, according to a study published in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

The researchers found an increased risk of death among cancer survivors who rarely exercised, were underweight, visited the doctor 5 or more times a year, considered themselves in “fair” or “poor” health, and had concerns about their future health.

Cheryl Cox, PhD, of the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and her colleagues conducted this research using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.

The team compared 7162 childhood cancer survivors to 445 subjects who survived childhood cancer but ultimately died from causes other than cancer or non-health-related events (such as accidents).

The researchers matched subjects according to their primary diagnosis, age at the time of baseline questionnaire, and the time from diagnosis to baseline questionnaire.

Among the 445 subjects who died, the median age at death was 37.6 years. Malignant neoplasms (42%), cardiac conditions (20%), and pulmonary conditions (7%) caused the most deaths.

Subjects who died were slightly older than living subjects and more often of black race (vs white, Hispanic, or “other”). They were less likely to have a post-high school education or to be married. And they were more likely to have a household income below $20,000 or have an existing grade 3 or 4 chronic health condition.

When the researchers adjusted their analyses for sociodemographic characteristics, exposure to chemotherapy and/or radiation, and the number and severity of chronic health conditions, they identified a number of factors associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality.

One of these factors was a lack of exercise—specifically, not exercising at all (odds ratio [OR]=1.72, P<0.001) or exercising 1 to 2 days a week (OR=1.65, P=0.004), compared to exercising 3 or more days a week.

On the other hand, being overweight or obese did not significantly increase a subject’s risk of death, but being underweight did (OR=2.58, P<0.001).

As one might expect, increased use of medical care was associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Subjects who reported 5 to 6 doctor visits per year had twice the risk of death as subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=2.07, P<0.001). And subjects who reported more than 20 annual doctor visits had a nearly 4-fold greater risk of death than subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=3.87, P<0.001).

Similarly, subjects had an increased risk of mortality if they described their general health as being “poor” or “fair” (OR=1.98, P<0.001). And being “concerned” or “very concerned” about future health was associated with an increased risk of mortality as well (OR=1.54, P=0.01)

On the other hand, smoking did not have a significant impact on the risk of death, and alcohol consumption appeared to have a positive impact on life expectancy.

Subjects who reported consuming 5 or more drinks per month had a lower risk of mortality than subjects who said they did not consume alcohol at all (OR=0.75, P=0.05).

Dr Cox and her colleagues said this research has revealed novel predictors of mortality not associated with a cancer survivor’s primary disease, treatment, or late effects. And continued observation could point to interventions for reducing the risk of death in these patients. ![]()

Molecule can increase Hb in anemic cancer patients

SAN DIEGO—Results of a pilot study suggest an experimental molecule can increase hemoglobin levels in patients with hematologic malignancies who are suffering from anemia.

The molecule, lexaptepid pegol (NOX-H94), is a pegylated L-stereoisomer RNA aptamer that binds and neutralizes hepcidin.

In this phase 2 study, 5 of 12 patients who received lexaptepid pegol experienced a hemoglobin increase of 1 g/dL or greater and qualified as responders.

Researchers presented these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 as abstract 3847. The study was supported by NOXXON Pharma AG, the Berlin, Germany-based company developing lexaptepid pegol.

“Our concept is to treat anemia by inhibiting the activity of hepcidin,” said study investigator Kai Riecke, MD, of NOXXON Pharma.

“Hepcidin regulates iron in the blood. The problem is that, in quite a few tumors, hepcidin reduces iron in the circulation, and, over a long period of time, that leads to iron-restricted anemia.”

So Dr Riecke and his colleagues tested their antihepcidin molecule, lexaptepid pegol, in anemic cancer patients. The team enrolled patients with hemoglobin levels less than 10 g/dL who had been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The patients had a median age of 64 years (range, 35-77). At baseline, the mean hemoglobin was 9.5 ± 0.2 g/dL, the mean serum ferritin was 1067 ± 297 μg/L, the mean serum iron was 34 ± 6 μg/dL, and the mean transferrin saturation was 16.7 ± 3.4%.

The patients received twice-weekly intravenous infusions of lexaptepid pegol for 4 weeks, and the researchers observed patients for 1 month after treatment. Patients were not allowed to receive erythropoiesis-stimulating agents or iron products during the study period.

The results showed increases in hemoglobin of 1 g/dL or greater, which qualified as a response, in 5 of the 12 patients (42%). Three patients achieved a response within 2 weeks of treatment initiation. All 5 patients maintained the increase in hemoglobin throughout the follow-up period.

There was no clear difference in response among the different malignancies, Dr Reike said. But he also noted that, as the study included a small number of patients, it wasn’t really possible for the researchers to make a fair comparison.

In addition to increasing hemoglobin levels, lexaptepid pegol decreased the mean serum ferritin from 1067 μg/L to 815 μg/L in the entire cohort of patients (P=0.014) and from 772 μg/L to 462 μg/L in responders (but this was not significant).

Reticulocyte hemoglobin increased from 22.7 pg to 24.9 pg (P=0.019) in responding patients, but there was no increase in non-responders. (Data for this measurement were only available for 3 of the responders—but all 7 of the non-responders—due to differences in measurement capabilities at the different research sites).

“During the treatment, we saw a very nice increase in reticulocyte hemoglobin, which shows, in these patients, the red blood cells were able to take up iron and build up more hemoglobin,” Dr Riecke said.

The researchers also observed an increase in the mean reticulocyte index in responding patients, from 0.9 to 1.2, although the increase was not significant.

“So this shows that, not only do you have an increase in hemoglobin within each reticulocyte, but you have an increase in the number of reticulocytes—something that we didn’t really expect in the beginning,” Dr Riecke said. “And this may be a sign that the efficacy of erythropoiesis is improved.”

Additionally, responding patients experienced a decrease in soluble transferrin receptor levels, from 10.0 mg/L to 8.6 mg/L, although this was not significant. Soluble transferrin receptor levels remained unchanged in non-responders. (Data for this measurement were only available for 3 of the responders and 4 of the non-responders.)

“The decrease in soluble transferrin receptor levels is a sign that, in the beginning, the cells were very iron-hungry, and then their hunger was satisfied—at least to a certain extent—during the treatment with our drug,” Dr Reike said. “This is a sign that, by reducing hepcidin, more iron is being released into the circulation, and this iron can effectively be used for erythropoiesis.”

Dr Reike added that, although the researchers did observe some adverse effects in the patients, none of these could be clearly attributed to lexaptepid pegol.

Some of the patients did have low blood pressure shortly after treatment, but that may have been influenced by factors other than treatment, he said. Furthermore, in the phase 1 study of lexaptepid pegol in healthy subjects, the only adverse effect that occurred in the treatment arm (and not in the placebo arm) was headache.

Based on these results, NOXXON is now planning—and recruiting for—a study of lexaptepid pegol in dialysis patients. ![]()

SAN DIEGO—Results of a pilot study suggest an experimental molecule can increase hemoglobin levels in patients with hematologic malignancies who are suffering from anemia.

The molecule, lexaptepid pegol (NOX-H94), is a pegylated L-stereoisomer RNA aptamer that binds and neutralizes hepcidin.

In this phase 2 study, 5 of 12 patients who received lexaptepid pegol experienced a hemoglobin increase of 1 g/dL or greater and qualified as responders.

Researchers presented these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 as abstract 3847. The study was supported by NOXXON Pharma AG, the Berlin, Germany-based company developing lexaptepid pegol.

“Our concept is to treat anemia by inhibiting the activity of hepcidin,” said study investigator Kai Riecke, MD, of NOXXON Pharma.

“Hepcidin regulates iron in the blood. The problem is that, in quite a few tumors, hepcidin reduces iron in the circulation, and, over a long period of time, that leads to iron-restricted anemia.”

So Dr Riecke and his colleagues tested their antihepcidin molecule, lexaptepid pegol, in anemic cancer patients. The team enrolled patients with hemoglobin levels less than 10 g/dL who had been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The patients had a median age of 64 years (range, 35-77). At baseline, the mean hemoglobin was 9.5 ± 0.2 g/dL, the mean serum ferritin was 1067 ± 297 μg/L, the mean serum iron was 34 ± 6 μg/dL, and the mean transferrin saturation was 16.7 ± 3.4%.

The patients received twice-weekly intravenous infusions of lexaptepid pegol for 4 weeks, and the researchers observed patients for 1 month after treatment. Patients were not allowed to receive erythropoiesis-stimulating agents or iron products during the study period.

The results showed increases in hemoglobin of 1 g/dL or greater, which qualified as a response, in 5 of the 12 patients (42%). Three patients achieved a response within 2 weeks of treatment initiation. All 5 patients maintained the increase in hemoglobin throughout the follow-up period.

There was no clear difference in response among the different malignancies, Dr Reike said. But he also noted that, as the study included a small number of patients, it wasn’t really possible for the researchers to make a fair comparison.

In addition to increasing hemoglobin levels, lexaptepid pegol decreased the mean serum ferritin from 1067 μg/L to 815 μg/L in the entire cohort of patients (P=0.014) and from 772 μg/L to 462 μg/L in responders (but this was not significant).

Reticulocyte hemoglobin increased from 22.7 pg to 24.9 pg (P=0.019) in responding patients, but there was no increase in non-responders. (Data for this measurement were only available for 3 of the responders—but all 7 of the non-responders—due to differences in measurement capabilities at the different research sites).

“During the treatment, we saw a very nice increase in reticulocyte hemoglobin, which shows, in these patients, the red blood cells were able to take up iron and build up more hemoglobin,” Dr Riecke said.

The researchers also observed an increase in the mean reticulocyte index in responding patients, from 0.9 to 1.2, although the increase was not significant.

“So this shows that, not only do you have an increase in hemoglobin within each reticulocyte, but you have an increase in the number of reticulocytes—something that we didn’t really expect in the beginning,” Dr Riecke said. “And this may be a sign that the efficacy of erythropoiesis is improved.”

Additionally, responding patients experienced a decrease in soluble transferrin receptor levels, from 10.0 mg/L to 8.6 mg/L, although this was not significant. Soluble transferrin receptor levels remained unchanged in non-responders. (Data for this measurement were only available for 3 of the responders and 4 of the non-responders.)

“The decrease in soluble transferrin receptor levels is a sign that, in the beginning, the cells were very iron-hungry, and then their hunger was satisfied—at least to a certain extent—during the treatment with our drug,” Dr Reike said. “This is a sign that, by reducing hepcidin, more iron is being released into the circulation, and this iron can effectively be used for erythropoiesis.”

Dr Reike added that, although the researchers did observe some adverse effects in the patients, none of these could be clearly attributed to lexaptepid pegol.

Some of the patients did have low blood pressure shortly after treatment, but that may have been influenced by factors other than treatment, he said. Furthermore, in the phase 1 study of lexaptepid pegol in healthy subjects, the only adverse effect that occurred in the treatment arm (and not in the placebo arm) was headache.

Based on these results, NOXXON is now planning—and recruiting for—a study of lexaptepid pegol in dialysis patients. ![]()

SAN DIEGO—Results of a pilot study suggest an experimental molecule can increase hemoglobin levels in patients with hematologic malignancies who are suffering from anemia.

The molecule, lexaptepid pegol (NOX-H94), is a pegylated L-stereoisomer RNA aptamer that binds and neutralizes hepcidin.

In this phase 2 study, 5 of 12 patients who received lexaptepid pegol experienced a hemoglobin increase of 1 g/dL or greater and qualified as responders.

Researchers presented these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 as abstract 3847. The study was supported by NOXXON Pharma AG, the Berlin, Germany-based company developing lexaptepid pegol.

“Our concept is to treat anemia by inhibiting the activity of hepcidin,” said study investigator Kai Riecke, MD, of NOXXON Pharma.

“Hepcidin regulates iron in the blood. The problem is that, in quite a few tumors, hepcidin reduces iron in the circulation, and, over a long period of time, that leads to iron-restricted anemia.”

So Dr Riecke and his colleagues tested their antihepcidin molecule, lexaptepid pegol, in anemic cancer patients. The team enrolled patients with hemoglobin levels less than 10 g/dL who had been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The patients had a median age of 64 years (range, 35-77). At baseline, the mean hemoglobin was 9.5 ± 0.2 g/dL, the mean serum ferritin was 1067 ± 297 μg/L, the mean serum iron was 34 ± 6 μg/dL, and the mean transferrin saturation was 16.7 ± 3.4%.

The patients received twice-weekly intravenous infusions of lexaptepid pegol for 4 weeks, and the researchers observed patients for 1 month after treatment. Patients were not allowed to receive erythropoiesis-stimulating agents or iron products during the study period.

The results showed increases in hemoglobin of 1 g/dL or greater, which qualified as a response, in 5 of the 12 patients (42%). Three patients achieved a response within 2 weeks of treatment initiation. All 5 patients maintained the increase in hemoglobin throughout the follow-up period.

There was no clear difference in response among the different malignancies, Dr Reike said. But he also noted that, as the study included a small number of patients, it wasn’t really possible for the researchers to make a fair comparison.

In addition to increasing hemoglobin levels, lexaptepid pegol decreased the mean serum ferritin from 1067 μg/L to 815 μg/L in the entire cohort of patients (P=0.014) and from 772 μg/L to 462 μg/L in responders (but this was not significant).

Reticulocyte hemoglobin increased from 22.7 pg to 24.9 pg (P=0.019) in responding patients, but there was no increase in non-responders. (Data for this measurement were only available for 3 of the responders—but all 7 of the non-responders—due to differences in measurement capabilities at the different research sites).

“During the treatment, we saw a very nice increase in reticulocyte hemoglobin, which shows, in these patients, the red blood cells were able to take up iron and build up more hemoglobin,” Dr Riecke said.

The researchers also observed an increase in the mean reticulocyte index in responding patients, from 0.9 to 1.2, although the increase was not significant.

“So this shows that, not only do you have an increase in hemoglobin within each reticulocyte, but you have an increase in the number of reticulocytes—something that we didn’t really expect in the beginning,” Dr Riecke said. “And this may be a sign that the efficacy of erythropoiesis is improved.”

Additionally, responding patients experienced a decrease in soluble transferrin receptor levels, from 10.0 mg/L to 8.6 mg/L, although this was not significant. Soluble transferrin receptor levels remained unchanged in non-responders. (Data for this measurement were only available for 3 of the responders and 4 of the non-responders.)

“The decrease in soluble transferrin receptor levels is a sign that, in the beginning, the cells were very iron-hungry, and then their hunger was satisfied—at least to a certain extent—during the treatment with our drug,” Dr Reike said. “This is a sign that, by reducing hepcidin, more iron is being released into the circulation, and this iron can effectively be used for erythropoiesis.”

Dr Reike added that, although the researchers did observe some adverse effects in the patients, none of these could be clearly attributed to lexaptepid pegol.

Some of the patients did have low blood pressure shortly after treatment, but that may have been influenced by factors other than treatment, he said. Furthermore, in the phase 1 study of lexaptepid pegol in healthy subjects, the only adverse effect that occurred in the treatment arm (and not in the placebo arm) was headache.

Based on these results, NOXXON is now planning—and recruiting for—a study of lexaptepid pegol in dialysis patients. ![]()

Study reveals how cells keep from bursting

The Scripps Research Institute

Researchers have identified a protein that regulates cells’ volume to keep them from swelling excessively, according to a paper published in Cell.

The identification of this protein, dubbed SWELL1, solves a decades-long mystery of cell biology and could prompt further discoveries about its roles in health and disease, the researchers said.

“Knowing the identity of this protein and its gene opens up a broad new avenue of research,” said study author Ardem Patapoutian, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

Unraveling the mystery

Dr Patapoutian and his colleagues noted that water passes through the membrane of most cells with relative ease and tends to flow in a direction that evens out the concentration of dissolved molecules, or solutes.

“Any decrease in the solute concentration outside a cell or an increase within the cell will make the cell swell with water,” explained study author Zhaozhu Qiu, PhD, a member of the Patapoutian lab.

For decades, experiments have demonstrated the existence of a key relief valve for this swelling: an unidentified ion channel in the cell membrane called the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC).

VRAC opens in response to cell swelling and permits an outflow of chloride ions and other negatively charged molecules, which water molecules follow, thus reducing the swelling.

“For the past 30 years, scientists have known that there is this VRAC channel, and yet they haven’t known its molecular identity,” Dr Patapoutian said.

Finding the proteins that make VRAC and their genes was a goal that had eluded researchers because of the technical hurdles involved.

However, Dr Patapoutian and his colleagues were able to set up a rapid, high-throughput screening test based on fluorescence. They engineered human cells to produce a fluorescent protein whose glow would be quenched when the cells became swollen and VRAC channels opened.

The team cultured large arrays of the cells and, using RNA interference, blocked the activity of a different gene for each clump of cells. The idea was to watch for the groups of cells that continued to glow, indicating that the gene inactivation had disrupted VRAC.

In this way, with several rounds of tests, the researchers sifted through the human genome and ultimately found 1 gene whose disruption reliably terminated VRAC activity.

It was a gene that had been discovered in 2003 and catalogued as “LRRC8.” Although it appeared to code for a cell-membrane-spanning protein—as one would expect for an ion channel—almost nothing else was known about it. The team renamed it SWELL1.

Potential roles in disease

Investigating further, the researchers found that SWELL1 does localize to the cell membrane as an ion channel protein would. Experiments showed that certain mutations of SWELL1 alter the VRAC channel’s ion-passing properties, indicating that SWELL1 is a central feature of the ion channel itself.

“It is at least a major part of the VRAC channel for which cell biologists have been searching all this time,” Dr Patapoutian said.

The researchers now plan to study SWELL1 further, in particular, examining what happens to lab mice that lack the protein in various cell types.

Curiously, the gene for SWELL1 was first noted by scientists because a mutant, dysfunctional form of it causes agammaglobulinemia—a lack of B cells that leaves a person unusually vulnerable to infections. That suggests SWELL1 is somehow required for normal B-cell development.

“There also have been suggestions from prior studies that this volume-sensitive ion channel is involved in stroke because of the brain-tissue swelling associated with stroke and that it may be involved as well in the secretion of insulin by pancreatic cells,” Dr Patapoutian said.

“So there are lots of hints out there about its relevance to disease. We just have to go and figure it all out now.” ![]()

The Scripps Research Institute

Researchers have identified a protein that regulates cells’ volume to keep them from swelling excessively, according to a paper published in Cell.

The identification of this protein, dubbed SWELL1, solves a decades-long mystery of cell biology and could prompt further discoveries about its roles in health and disease, the researchers said.

“Knowing the identity of this protein and its gene opens up a broad new avenue of research,” said study author Ardem Patapoutian, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

Unraveling the mystery

Dr Patapoutian and his colleagues noted that water passes through the membrane of most cells with relative ease and tends to flow in a direction that evens out the concentration of dissolved molecules, or solutes.

“Any decrease in the solute concentration outside a cell or an increase within the cell will make the cell swell with water,” explained study author Zhaozhu Qiu, PhD, a member of the Patapoutian lab.

For decades, experiments have demonstrated the existence of a key relief valve for this swelling: an unidentified ion channel in the cell membrane called the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC).

VRAC opens in response to cell swelling and permits an outflow of chloride ions and other negatively charged molecules, which water molecules follow, thus reducing the swelling.

“For the past 30 years, scientists have known that there is this VRAC channel, and yet they haven’t known its molecular identity,” Dr Patapoutian said.

Finding the proteins that make VRAC and their genes was a goal that had eluded researchers because of the technical hurdles involved.

However, Dr Patapoutian and his colleagues were able to set up a rapid, high-throughput screening test based on fluorescence. They engineered human cells to produce a fluorescent protein whose glow would be quenched when the cells became swollen and VRAC channels opened.

The team cultured large arrays of the cells and, using RNA interference, blocked the activity of a different gene for each clump of cells. The idea was to watch for the groups of cells that continued to glow, indicating that the gene inactivation had disrupted VRAC.

In this way, with several rounds of tests, the researchers sifted through the human genome and ultimately found 1 gene whose disruption reliably terminated VRAC activity.

It was a gene that had been discovered in 2003 and catalogued as “LRRC8.” Although it appeared to code for a cell-membrane-spanning protein—as one would expect for an ion channel—almost nothing else was known about it. The team renamed it SWELL1.

Potential roles in disease

Investigating further, the researchers found that SWELL1 does localize to the cell membrane as an ion channel protein would. Experiments showed that certain mutations of SWELL1 alter the VRAC channel’s ion-passing properties, indicating that SWELL1 is a central feature of the ion channel itself.

“It is at least a major part of the VRAC channel for which cell biologists have been searching all this time,” Dr Patapoutian said.

The researchers now plan to study SWELL1 further, in particular, examining what happens to lab mice that lack the protein in various cell types.

Curiously, the gene for SWELL1 was first noted by scientists because a mutant, dysfunctional form of it causes agammaglobulinemia—a lack of B cells that leaves a person unusually vulnerable to infections. That suggests SWELL1 is somehow required for normal B-cell development.

“There also have been suggestions from prior studies that this volume-sensitive ion channel is involved in stroke because of the brain-tissue swelling associated with stroke and that it may be involved as well in the secretion of insulin by pancreatic cells,” Dr Patapoutian said.

“So there are lots of hints out there about its relevance to disease. We just have to go and figure it all out now.” ![]()

The Scripps Research Institute

Researchers have identified a protein that regulates cells’ volume to keep them from swelling excessively, according to a paper published in Cell.

The identification of this protein, dubbed SWELL1, solves a decades-long mystery of cell biology and could prompt further discoveries about its roles in health and disease, the researchers said.

“Knowing the identity of this protein and its gene opens up a broad new avenue of research,” said study author Ardem Patapoutian, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

Unraveling the mystery

Dr Patapoutian and his colleagues noted that water passes through the membrane of most cells with relative ease and tends to flow in a direction that evens out the concentration of dissolved molecules, or solutes.

“Any decrease in the solute concentration outside a cell or an increase within the cell will make the cell swell with water,” explained study author Zhaozhu Qiu, PhD, a member of the Patapoutian lab.

For decades, experiments have demonstrated the existence of a key relief valve for this swelling: an unidentified ion channel in the cell membrane called the volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC).

VRAC opens in response to cell swelling and permits an outflow of chloride ions and other negatively charged molecules, which water molecules follow, thus reducing the swelling.

“For the past 30 years, scientists have known that there is this VRAC channel, and yet they haven’t known its molecular identity,” Dr Patapoutian said.

Finding the proteins that make VRAC and their genes was a goal that had eluded researchers because of the technical hurdles involved.

However, Dr Patapoutian and his colleagues were able to set up a rapid, high-throughput screening test based on fluorescence. They engineered human cells to produce a fluorescent protein whose glow would be quenched when the cells became swollen and VRAC channels opened.

The team cultured large arrays of the cells and, using RNA interference, blocked the activity of a different gene for each clump of cells. The idea was to watch for the groups of cells that continued to glow, indicating that the gene inactivation had disrupted VRAC.

In this way, with several rounds of tests, the researchers sifted through the human genome and ultimately found 1 gene whose disruption reliably terminated VRAC activity.

It was a gene that had been discovered in 2003 and catalogued as “LRRC8.” Although it appeared to code for a cell-membrane-spanning protein—as one would expect for an ion channel—almost nothing else was known about it. The team renamed it SWELL1.

Potential roles in disease

Investigating further, the researchers found that SWELL1 does localize to the cell membrane as an ion channel protein would. Experiments showed that certain mutations of SWELL1 alter the VRAC channel’s ion-passing properties, indicating that SWELL1 is a central feature of the ion channel itself.

“It is at least a major part of the VRAC channel for which cell biologists have been searching all this time,” Dr Patapoutian said.

The researchers now plan to study SWELL1 further, in particular, examining what happens to lab mice that lack the protein in various cell types.

Curiously, the gene for SWELL1 was first noted by scientists because a mutant, dysfunctional form of it causes agammaglobulinemia—a lack of B cells that leaves a person unusually vulnerable to infections. That suggests SWELL1 is somehow required for normal B-cell development.

“There also have been suggestions from prior studies that this volume-sensitive ion channel is involved in stroke because of the brain-tissue swelling associated with stroke and that it may be involved as well in the secretion of insulin by pancreatic cells,” Dr Patapoutian said.

“So there are lots of hints out there about its relevance to disease. We just have to go and figure it all out now.” ![]()

FDA panel considers human studies of modified oocytes for preventing disease

GAITHERSBURG, MD. – The first human studies evaluating the use of genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases could enroll women with diseases that are the most severe, tend to present in early childhood, and are relatively common for a mitochondrial disease, according to panelists at a meeting convened by the Food and Drug Administration to discuss the design of such trials and related issues.

At a meeting on Feb. 25 and 26, members of the FDA Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee mentioned two mitochondrial diseases in particular, Leigh’s disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes), that could be included in initial clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of what the FDA refers to as "mitochondrial manipulation technologies."

This controversial approach, which is being developed to prevent maternal transmission of debilitating and often fatal mitochondrial diseases, entails removing the mitochondrial DNA from an affected woman’s oocyte or embryo and replacing it via assisted reproductive technologies with the mitochondrial DNA from the egg of a healthy donor.

The approach has been studied in animal and in vitro studies, but not yet in humans. However, researchers at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), Portland, say they are ready to start a clinical trial based on their results in macaque monkeys.

The FDA called the 2-day meeting to discuss potential clinical trials and to focus on the scientific, technologic, and clinical aspects of the technologies, but not to address public policy or ethical issues. In briefing documents posted before the meeting, the agency acknowledged that there are ethical and policy issues related to genetic modification of eggs and embryos, which can affect regulatory decisions, but added that these issues were "outside the scope" of this meeting.

Regarding clinical trial design and execution, panelists recommended that studies should closely monitor the fetus through gestation, and after birth and long-term follow-up, should include future generations, if female offspring are included. Several panelists supported including only male embryos to minimize the risk of a female passing on damaged DNA to future generations, while others said this would result in a lost opportunity to study the transgenerational risks of the technology.

Other recommendations included avoiding the enrollment of people at high risk of having a baby with a birth defect, or with comorbidities that could affect birth outcome, which would make it more difficult to evaluate the risks of the technologies. The use of controls, panelists said, was problematic, because of the variability in when and how mitochondrial diseases present and because of the relatively small populations of patients affected by these diseases. Historical controls could be used, but larger patient registries are needed, they said.

Panelists also recommended screening egg donors for mitochondrial diseases, and providing informed consent to children born to mothers in the trials when they turn age 18.

It is clear that there is a "deft group of creative, innovative investigators" who can perform these techniques, "which is a good start, but there are so many things we don’t know" that must be evaluated further in animal studies, said panelist Dr. David Keefe, who referred to thalidomide and diethylstilbestrol (DES) as historical examples of therapies that were thought to be promising but proved to have devastating effects.

Another concern Dr. Keefe raised was the possibility that a woman whose risk of having a baby without the inherited defect might be as high as 95% and that she might choose mitochondrial manipulation over preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

"A woman could be led down the primrose path towards a procedure that’s experimental and miss the opportunity to pursue a relatively well-established procedure," said Dr. Keefe, the Stanley H. Kaplan Professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, New York University.

Another panelist, Dr. Katharine Wenstrom, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Brown University, Providence, R.I., said that based on her experience with women with genetic diseases, these women "are very vulnerable, and my concern would be how to [provide] consent [for] somebody for whom a pregnancy would be very dangerous and [who] might not consider a pregnancy, but then given the opportunity to have this technique, might agree to a pregnancy that could actually be life threatening."

She also said that she was concerned about whether the technique could deplete mitochondria, which has been associated with several forms of cancer, and about the "inability to ensure that the technique has not inflicted some new abnormality" on the child.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, Ph.D., whose research group at the Oregon Stem Cell Center at OHSU has tested the technology in macaque monkeys, said that their research cohort currently includes four subjects born through mitochondrial manipulation that are almost adults. To date, they have been healthy, with normal blood test results, and are no different from controls, showing that mitochondrial DNA in oocytes can be replaced.

The next step in their research is to recruit families who are carriers of early-onset mitochondrial DNA diseases who have had at least one affected child, recruit healthy egg donors, and then perform the procedure, followed by preimplantation genetic diagnosis of the embryo and/or prenatal diagnosis to "ensure complete mitochondrial DNA replacement and chromosomal normalcy," he said.

The panel was also asked to discuss the use of mitochondrial manipulation as a treatment for infertility. However, members considered this indication a far different type of application than preventing mitochondrial disease, which would have different inclusion criteria, controls, and risk-benefit evaluations, and several panelists raised particular concerns about the use of this technology for infertility.

"The idea we’re going to do anything to infertility patients involving mitochondria I think should be off the table," Dr. Keefe said, noting that there is "a very, very slippery slope when you’re dealing with human reproduction" in the United States, where licensure of infertility clinics is not required.

The controversies of this area of research, which some critics point out would result in a child with three genetically related parents, were not off limits to the open public hearing speakers, including Marcy Darnovsky, Ph.D., executive director of the Center for Genetics and Society.

"We want to avoid waking up in a world" where researchers, infertility clinics, governments, insurance companies, "or parents decide that they are going to try to engineer children with specific traits and even possibly [put] in motion a regime of high-tech consumer eugenics," she said.

GAITHERSBURG, MD. – The first human studies evaluating the use of genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases could enroll women with diseases that are the most severe, tend to present in early childhood, and are relatively common for a mitochondrial disease, according to panelists at a meeting convened by the Food and Drug Administration to discuss the design of such trials and related issues.

At a meeting on Feb. 25 and 26, members of the FDA Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee mentioned two mitochondrial diseases in particular, Leigh’s disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes), that could be included in initial clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of what the FDA refers to as "mitochondrial manipulation technologies."

This controversial approach, which is being developed to prevent maternal transmission of debilitating and often fatal mitochondrial diseases, entails removing the mitochondrial DNA from an affected woman’s oocyte or embryo and replacing it via assisted reproductive technologies with the mitochondrial DNA from the egg of a healthy donor.

The approach has been studied in animal and in vitro studies, but not yet in humans. However, researchers at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), Portland, say they are ready to start a clinical trial based on their results in macaque monkeys.

The FDA called the 2-day meeting to discuss potential clinical trials and to focus on the scientific, technologic, and clinical aspects of the technologies, but not to address public policy or ethical issues. In briefing documents posted before the meeting, the agency acknowledged that there are ethical and policy issues related to genetic modification of eggs and embryos, which can affect regulatory decisions, but added that these issues were "outside the scope" of this meeting.

Regarding clinical trial design and execution, panelists recommended that studies should closely monitor the fetus through gestation, and after birth and long-term follow-up, should include future generations, if female offspring are included. Several panelists supported including only male embryos to minimize the risk of a female passing on damaged DNA to future generations, while others said this would result in a lost opportunity to study the transgenerational risks of the technology.

Other recommendations included avoiding the enrollment of people at high risk of having a baby with a birth defect, or with comorbidities that could affect birth outcome, which would make it more difficult to evaluate the risks of the technologies. The use of controls, panelists said, was problematic, because of the variability in when and how mitochondrial diseases present and because of the relatively small populations of patients affected by these diseases. Historical controls could be used, but larger patient registries are needed, they said.

Panelists also recommended screening egg donors for mitochondrial diseases, and providing informed consent to children born to mothers in the trials when they turn age 18.

It is clear that there is a "deft group of creative, innovative investigators" who can perform these techniques, "which is a good start, but there are so many things we don’t know" that must be evaluated further in animal studies, said panelist Dr. David Keefe, who referred to thalidomide and diethylstilbestrol (DES) as historical examples of therapies that were thought to be promising but proved to have devastating effects.

Another concern Dr. Keefe raised was the possibility that a woman whose risk of having a baby without the inherited defect might be as high as 95% and that she might choose mitochondrial manipulation over preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

"A woman could be led down the primrose path towards a procedure that’s experimental and miss the opportunity to pursue a relatively well-established procedure," said Dr. Keefe, the Stanley H. Kaplan Professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, New York University.

Another panelist, Dr. Katharine Wenstrom, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Brown University, Providence, R.I., said that based on her experience with women with genetic diseases, these women "are very vulnerable, and my concern would be how to [provide] consent [for] somebody for whom a pregnancy would be very dangerous and [who] might not consider a pregnancy, but then given the opportunity to have this technique, might agree to a pregnancy that could actually be life threatening."

She also said that she was concerned about whether the technique could deplete mitochondria, which has been associated with several forms of cancer, and about the "inability to ensure that the technique has not inflicted some new abnormality" on the child.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, Ph.D., whose research group at the Oregon Stem Cell Center at OHSU has tested the technology in macaque monkeys, said that their research cohort currently includes four subjects born through mitochondrial manipulation that are almost adults. To date, they have been healthy, with normal blood test results, and are no different from controls, showing that mitochondrial DNA in oocytes can be replaced.

The next step in their research is to recruit families who are carriers of early-onset mitochondrial DNA diseases who have had at least one affected child, recruit healthy egg donors, and then perform the procedure, followed by preimplantation genetic diagnosis of the embryo and/or prenatal diagnosis to "ensure complete mitochondrial DNA replacement and chromosomal normalcy," he said.

The panel was also asked to discuss the use of mitochondrial manipulation as a treatment for infertility. However, members considered this indication a far different type of application than preventing mitochondrial disease, which would have different inclusion criteria, controls, and risk-benefit evaluations, and several panelists raised particular concerns about the use of this technology for infertility.

"The idea we’re going to do anything to infertility patients involving mitochondria I think should be off the table," Dr. Keefe said, noting that there is "a very, very slippery slope when you’re dealing with human reproduction" in the United States, where licensure of infertility clinics is not required.

The controversies of this area of research, which some critics point out would result in a child with three genetically related parents, were not off limits to the open public hearing speakers, including Marcy Darnovsky, Ph.D., executive director of the Center for Genetics and Society.

"We want to avoid waking up in a world" where researchers, infertility clinics, governments, insurance companies, "or parents decide that they are going to try to engineer children with specific traits and even possibly [put] in motion a regime of high-tech consumer eugenics," she said.

GAITHERSBURG, MD. – The first human studies evaluating the use of genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases could enroll women with diseases that are the most severe, tend to present in early childhood, and are relatively common for a mitochondrial disease, according to panelists at a meeting convened by the Food and Drug Administration to discuss the design of such trials and related issues.

At a meeting on Feb. 25 and 26, members of the FDA Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee mentioned two mitochondrial diseases in particular, Leigh’s disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes), that could be included in initial clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of what the FDA refers to as "mitochondrial manipulation technologies."

This controversial approach, which is being developed to prevent maternal transmission of debilitating and often fatal mitochondrial diseases, entails removing the mitochondrial DNA from an affected woman’s oocyte or embryo and replacing it via assisted reproductive technologies with the mitochondrial DNA from the egg of a healthy donor.

The approach has been studied in animal and in vitro studies, but not yet in humans. However, researchers at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), Portland, say they are ready to start a clinical trial based on their results in macaque monkeys.

The FDA called the 2-day meeting to discuss potential clinical trials and to focus on the scientific, technologic, and clinical aspects of the technologies, but not to address public policy or ethical issues. In briefing documents posted before the meeting, the agency acknowledged that there are ethical and policy issues related to genetic modification of eggs and embryos, which can affect regulatory decisions, but added that these issues were "outside the scope" of this meeting.

Regarding clinical trial design and execution, panelists recommended that studies should closely monitor the fetus through gestation, and after birth and long-term follow-up, should include future generations, if female offspring are included. Several panelists supported including only male embryos to minimize the risk of a female passing on damaged DNA to future generations, while others said this would result in a lost opportunity to study the transgenerational risks of the technology.

Other recommendations included avoiding the enrollment of people at high risk of having a baby with a birth defect, or with comorbidities that could affect birth outcome, which would make it more difficult to evaluate the risks of the technologies. The use of controls, panelists said, was problematic, because of the variability in when and how mitochondrial diseases present and because of the relatively small populations of patients affected by these diseases. Historical controls could be used, but larger patient registries are needed, they said.

Panelists also recommended screening egg donors for mitochondrial diseases, and providing informed consent to children born to mothers in the trials when they turn age 18.

It is clear that there is a "deft group of creative, innovative investigators" who can perform these techniques, "which is a good start, but there are so many things we don’t know" that must be evaluated further in animal studies, said panelist Dr. David Keefe, who referred to thalidomide and diethylstilbestrol (DES) as historical examples of therapies that were thought to be promising but proved to have devastating effects.

Another concern Dr. Keefe raised was the possibility that a woman whose risk of having a baby without the inherited defect might be as high as 95% and that she might choose mitochondrial manipulation over preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

"A woman could be led down the primrose path towards a procedure that’s experimental and miss the opportunity to pursue a relatively well-established procedure," said Dr. Keefe, the Stanley H. Kaplan Professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, New York University.

Another panelist, Dr. Katharine Wenstrom, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Brown University, Providence, R.I., said that based on her experience with women with genetic diseases, these women "are very vulnerable, and my concern would be how to [provide] consent [for] somebody for whom a pregnancy would be very dangerous and [who] might not consider a pregnancy, but then given the opportunity to have this technique, might agree to a pregnancy that could actually be life threatening."

She also said that she was concerned about whether the technique could deplete mitochondria, which has been associated with several forms of cancer, and about the "inability to ensure that the technique has not inflicted some new abnormality" on the child.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, Ph.D., whose research group at the Oregon Stem Cell Center at OHSU has tested the technology in macaque monkeys, said that their research cohort currently includes four subjects born through mitochondrial manipulation that are almost adults. To date, they have been healthy, with normal blood test results, and are no different from controls, showing that mitochondrial DNA in oocytes can be replaced.

The next step in their research is to recruit families who are carriers of early-onset mitochondrial DNA diseases who have had at least one affected child, recruit healthy egg donors, and then perform the procedure, followed by preimplantation genetic diagnosis of the embryo and/or prenatal diagnosis to "ensure complete mitochondrial DNA replacement and chromosomal normalcy," he said.

The panel was also asked to discuss the use of mitochondrial manipulation as a treatment for infertility. However, members considered this indication a far different type of application than preventing mitochondrial disease, which would have different inclusion criteria, controls, and risk-benefit evaluations, and several panelists raised particular concerns about the use of this technology for infertility.

"The idea we’re going to do anything to infertility patients involving mitochondria I think should be off the table," Dr. Keefe said, noting that there is "a very, very slippery slope when you’re dealing with human reproduction" in the United States, where licensure of infertility clinics is not required.

The controversies of this area of research, which some critics point out would result in a child with three genetically related parents, were not off limits to the open public hearing speakers, including Marcy Darnovsky, Ph.D., executive director of the Center for Genetics and Society.

"We want to avoid waking up in a world" where researchers, infertility clinics, governments, insurance companies, "or parents decide that they are going to try to engineer children with specific traits and even possibly [put] in motion a regime of high-tech consumer eugenics," she said.

AT AN FDA ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING

VIDEO: Oocyte modification might prevent mitochondrial diseases

Clinical trials using genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases in humans may be soon become a reality. But the potentially promising approach to prevent conditions such as Leigh disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes) is not without controversy.

In an interview, Dr. Salvatore DiMauro, the Lucy G. Moses Professor of Neurology at Columbia University Medical Center, outlined the impact that mitochondrial DNA–related diseases have on women’s and children’s lives, and he explained why genetically modified oocytes may offer new hope for those affected by these diseases.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Clinical trials using genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases in humans may be soon become a reality. But the potentially promising approach to prevent conditions such as Leigh disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes) is not without controversy.

In an interview, Dr. Salvatore DiMauro, the Lucy G. Moses Professor of Neurology at Columbia University Medical Center, outlined the impact that mitochondrial DNA–related diseases have on women’s and children’s lives, and he explained why genetically modified oocytes may offer new hope for those affected by these diseases.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Clinical trials using genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases in humans may be soon become a reality. But the potentially promising approach to prevent conditions such as Leigh disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes) is not without controversy.

In an interview, Dr. Salvatore DiMauro, the Lucy G. Moses Professor of Neurology at Columbia University Medical Center, outlined the impact that mitochondrial DNA–related diseases have on women’s and children’s lives, and he explained why genetically modified oocytes may offer new hope for those affected by these diseases.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT AN FDA ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING

Clostridium difficile: Not just for adults

The true prevalence and meaning of Clostridium difficile detection in children remains an issue despite a known high prevalence of asymptomatic colonization in children during the first 3 years of life. Distinguishing C. difficile disease from colonization is difficult. Endoscopy can identify some severe C. difficile disease, but what about mild to moderate C. difficile infection?

A passive Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance study (Pediatrics 2014;133:651-8) helps in understanding C. difficile prevalence by documenting the relatively high prevalence of community-acquired C. difficile often associated with use of common oral antibiotics and possibly because of the emergence of the NAP1 strain, which is also emerging in adults. But distinguishing infection from colonization remains an issue. The data have implications for everyday pediatric care.

Methods

Children aged 1-17 years from 10 U.S. states were studied during 2011-2012. C. difficile "cases" were defined via a positive toxin or a molecular test ordered as part of standard care. Standard of care testing for other selected gastrointestinal pathogens and data from medical records were collected. Within 3-6 months of the C. difficile–positive test, a convenience sample of families (about 9%) underwent a telephone interview.

Factors in C. difficile detection

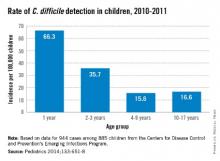

C. difficile was detected in 944 stools from 885 children with no gender difference. The highest rates per 100,000 by race were in whites (23.9) vs. nonwhites (17.4), and in 12- to 23-month-olds (66.3). Overall, 71% of detections were categorized from charted data as community acquired. Only 17% were associated with outpatient health care and 12% with inpatient care.

Antibiotic use in the 14 days before a C. difficile–positive stool was 33% among all cases with no age group differences. Cephalosporins (41%) and amoxicillin/clavulanate (28%) were most common. Among 84 cases also later interviewed by phone, antibiotic use was more frequent (73%); penicillins (39%) and cephalosporins (44%) were the antibiotics most commonly used in this subset of patients. Indications were most often otitis, sinusitis, or upper respiratory infection. In the phone interviews, outpatient office visits were a more frequent (97%) health care exposure than in the overall case population.

Signs and symptoms were mild and similar in all age groups. Diarrhea was not present in 28%. Coinfection with another enteric pathogen was identified in 3% of 535 tested samples: bacterial (n = 12), protozoal (n = 4), and viral (n = 1) – and more common in 2- to 9-year-olds (P = .03). Peripheral WBC counts were abnormal (greater than 15, 000/mm3) in only 7%. There was radiographic evidence of ileus in three and pseudomembranous colitis developed in five cases. Cases were defined as severe in 8% with no age preponderance. There were no deaths.

Infection vs. colonization?

The authors reason that similar clinical presentations and symptom severity at all ages means that detection of C. difficile "likely represents infection" but not colonization. They explain that they expect milder symptoms in the youngest cases if they were only colonized. Is this reasonable?

One could counterargue that in the absence of testing for the most common diarrheagenic pathogen in the United States (norovirus), that diarrhea in at least some of these C. difficile–positive children was likely caused by undetected norovirus. That could partially explain why symptoms were not significantly different by age. One viral coinfection in nearly 500 diarrhea stools (even preselected by C. difficile positivity) seems low. Even if norovirus is not the wildcard here, the similar "disease" at all ages could suggest that something other than C. difficile is the cause. Norovirus and other viral agents testing of samples that were cultured for C. difficile could increase understanding of coinfection rates. Another issue is that 28% of C. difficile children did not have diarrhea, raising concern that these were colonized children.

The authors state that high antibiotic use (73% in phone interviewees) might have contributed to the high C. difficile detection rates. This seems logical, but the phone-derived data came from only about 8% of the total population. The original charted data from the entire population showed 33% antibiotic use. The charted data may have been more reliable because it was collected at the time of the C. difficile–positive stool, not 3-6 months later. Nevertheless, it seems apparent that common outpatient antibiotics could be a factor. If the data were compared with antibiotic use rates for C. difficile–negative children of the same ages, the conclusion would be more powerful.

Children less than 1year of age were not included because up to 73% (Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1989;8:390-3) of infants have been reported as asymptomatically colonized. In similar studies, colonized infants were frequent (25% between 6 days and 6 months) up to about 3 years of age when rates dropped off to less than 3%, similar to adults. Inclusion of children in the second and third year of life likely means that not all detections were infections. But there is no way to definitively distinguish infection from colonization in this study.

A further step in filling the knowledge gap on C. difficile would be prospective surveillance with improved definitions of infection vs. colonization and a more complete search for potential concurrent causes of diarrhea. Undoubtedly, many of these C. difficile–positive children had true infection, but it also seems likely that some were colonized, particularly in the second and third year of life. It would be interesting to compare results from healthy controls vs. those with diarrhea using new multiplex molecular assays to gain a better understanding of what proportion of all children have detectable C. difficile with and without other pathogens.

Bottom line

NAP1 C. difficile is emerging in children. C. difficile detection, whether infected or colonized, in this many children is new. These data suggest that our best contributions to reducing the spread of C. difficile are the use of amoxicillin without clavulanate as first line – if antibiotics are needed for acute otitis media and for acute sinusitis – while we refrain from antibiotics for viral upper respiratory infections. As the old knight told Indiana Jones, "Choose wisely."

Factors associated with C. difficile detection in children

1. White race. Question more frequent health care and antibiotic exposure.

2. Age 12 to 23 months. Question whether the population is mix of colonized and infected children. This needs more study.

3. Amoxicillin/clavulanate or oral cephalosporin use for common outpatient infection. Is narrower spectrum, amoxicillin alone better?

4. A recent outpatient health care visit may be a cofactor with #1 and #3.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Dr. Harrison said he has no relevant financial disclosures. E-mail him at [email protected].

The true prevalence and meaning of Clostridium difficile detection in children remains an issue despite a known high prevalence of asymptomatic colonization in children during the first 3 years of life. Distinguishing C. difficile disease from colonization is difficult. Endoscopy can identify some severe C. difficile disease, but what about mild to moderate C. difficile infection?

A passive Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance study (Pediatrics 2014;133:651-8) helps in understanding C. difficile prevalence by documenting the relatively high prevalence of community-acquired C. difficile often associated with use of common oral antibiotics and possibly because of the emergence of the NAP1 strain, which is also emerging in adults. But distinguishing infection from colonization remains an issue. The data have implications for everyday pediatric care.

Methods

Children aged 1-17 years from 10 U.S. states were studied during 2011-2012. C. difficile "cases" were defined via a positive toxin or a molecular test ordered as part of standard care. Standard of care testing for other selected gastrointestinal pathogens and data from medical records were collected. Within 3-6 months of the C. difficile–positive test, a convenience sample of families (about 9%) underwent a telephone interview.

Factors in C. difficile detection

C. difficile was detected in 944 stools from 885 children with no gender difference. The highest rates per 100,000 by race were in whites (23.9) vs. nonwhites (17.4), and in 12- to 23-month-olds (66.3). Overall, 71% of detections were categorized from charted data as community acquired. Only 17% were associated with outpatient health care and 12% with inpatient care.

Antibiotic use in the 14 days before a C. difficile–positive stool was 33% among all cases with no age group differences. Cephalosporins (41%) and amoxicillin/clavulanate (28%) were most common. Among 84 cases also later interviewed by phone, antibiotic use was more frequent (73%); penicillins (39%) and cephalosporins (44%) were the antibiotics most commonly used in this subset of patients. Indications were most often otitis, sinusitis, or upper respiratory infection. In the phone interviews, outpatient office visits were a more frequent (97%) health care exposure than in the overall case population.

Signs and symptoms were mild and similar in all age groups. Diarrhea was not present in 28%. Coinfection with another enteric pathogen was identified in 3% of 535 tested samples: bacterial (n = 12), protozoal (n = 4), and viral (n = 1) – and more common in 2- to 9-year-olds (P = .03). Peripheral WBC counts were abnormal (greater than 15, 000/mm3) in only 7%. There was radiographic evidence of ileus in three and pseudomembranous colitis developed in five cases. Cases were defined as severe in 8% with no age preponderance. There were no deaths.

Infection vs. colonization?

The authors reason that similar clinical presentations and symptom severity at all ages means that detection of C. difficile "likely represents infection" but not colonization. They explain that they expect milder symptoms in the youngest cases if they were only colonized. Is this reasonable?

One could counterargue that in the absence of testing for the most common diarrheagenic pathogen in the United States (norovirus), that diarrhea in at least some of these C. difficile–positive children was likely caused by undetected norovirus. That could partially explain why symptoms were not significantly different by age. One viral coinfection in nearly 500 diarrhea stools (even preselected by C. difficile positivity) seems low. Even if norovirus is not the wildcard here, the similar "disease" at all ages could suggest that something other than C. difficile is the cause. Norovirus and other viral agents testing of samples that were cultured for C. difficile could increase understanding of coinfection rates. Another issue is that 28% of C. difficile children did not have diarrhea, raising concern that these were colonized children.

The authors state that high antibiotic use (73% in phone interviewees) might have contributed to the high C. difficile detection rates. This seems logical, but the phone-derived data came from only about 8% of the total population. The original charted data from the entire population showed 33% antibiotic use. The charted data may have been more reliable because it was collected at the time of the C. difficile–positive stool, not 3-6 months later. Nevertheless, it seems apparent that common outpatient antibiotics could be a factor. If the data were compared with antibiotic use rates for C. difficile–negative children of the same ages, the conclusion would be more powerful.

Children less than 1year of age were not included because up to 73% (Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1989;8:390-3) of infants have been reported as asymptomatically colonized. In similar studies, colonized infants were frequent (25% between 6 days and 6 months) up to about 3 years of age when rates dropped off to less than 3%, similar to adults. Inclusion of children in the second and third year of life likely means that not all detections were infections. But there is no way to definitively distinguish infection from colonization in this study.

A further step in filling the knowledge gap on C. difficile would be prospective surveillance with improved definitions of infection vs. colonization and a more complete search for potential concurrent causes of diarrhea. Undoubtedly, many of these C. difficile–positive children had true infection, but it also seems likely that some were colonized, particularly in the second and third year of life. It would be interesting to compare results from healthy controls vs. those with diarrhea using new multiplex molecular assays to gain a better understanding of what proportion of all children have detectable C. difficile with and without other pathogens.

Bottom line

NAP1 C. difficile is emerging in children. C. difficile detection, whether infected or colonized, in this many children is new. These data suggest that our best contributions to reducing the spread of C. difficile are the use of amoxicillin without clavulanate as first line – if antibiotics are needed for acute otitis media and for acute sinusitis – while we refrain from antibiotics for viral upper respiratory infections. As the old knight told Indiana Jones, "Choose wisely."

Factors associated with C. difficile detection in children

1. White race. Question more frequent health care and antibiotic exposure.

2. Age 12 to 23 months. Question whether the population is mix of colonized and infected children. This needs more study.

3. Amoxicillin/clavulanate or oral cephalosporin use for common outpatient infection. Is narrower spectrum, amoxicillin alone better?

4. A recent outpatient health care visit may be a cofactor with #1 and #3.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Dr. Harrison said he has no relevant financial disclosures. E-mail him at [email protected].

The true prevalence and meaning of Clostridium difficile detection in children remains an issue despite a known high prevalence of asymptomatic colonization in children during the first 3 years of life. Distinguishing C. difficile disease from colonization is difficult. Endoscopy can identify some severe C. difficile disease, but what about mild to moderate C. difficile infection?

A passive Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance study (Pediatrics 2014;133:651-8) helps in understanding C. difficile prevalence by documenting the relatively high prevalence of community-acquired C. difficile often associated with use of common oral antibiotics and possibly because of the emergence of the NAP1 strain, which is also emerging in adults. But distinguishing infection from colonization remains an issue. The data have implications for everyday pediatric care.

Methods

Children aged 1-17 years from 10 U.S. states were studied during 2011-2012. C. difficile "cases" were defined via a positive toxin or a molecular test ordered as part of standard care. Standard of care testing for other selected gastrointestinal pathogens and data from medical records were collected. Within 3-6 months of the C. difficile–positive test, a convenience sample of families (about 9%) underwent a telephone interview.

Factors in C. difficile detection

C. difficile was detected in 944 stools from 885 children with no gender difference. The highest rates per 100,000 by race were in whites (23.9) vs. nonwhites (17.4), and in 12- to 23-month-olds (66.3). Overall, 71% of detections were categorized from charted data as community acquired. Only 17% were associated with outpatient health care and 12% with inpatient care.

Antibiotic use in the 14 days before a C. difficile–positive stool was 33% among all cases with no age group differences. Cephalosporins (41%) and amoxicillin/clavulanate (28%) were most common. Among 84 cases also later interviewed by phone, antibiotic use was more frequent (73%); penicillins (39%) and cephalosporins (44%) were the antibiotics most commonly used in this subset of patients. Indications were most often otitis, sinusitis, or upper respiratory infection. In the phone interviews, outpatient office visits were a more frequent (97%) health care exposure than in the overall case population.

Signs and symptoms were mild and similar in all age groups. Diarrhea was not present in 28%. Coinfection with another enteric pathogen was identified in 3% of 535 tested samples: bacterial (n = 12), protozoal (n = 4), and viral (n = 1) – and more common in 2- to 9-year-olds (P = .03). Peripheral WBC counts were abnormal (greater than 15, 000/mm3) in only 7%. There was radiographic evidence of ileus in three and pseudomembranous colitis developed in five cases. Cases were defined as severe in 8% with no age preponderance. There were no deaths.

Infection vs. colonization?

The authors reason that similar clinical presentations and symptom severity at all ages means that detection of C. difficile "likely represents infection" but not colonization. They explain that they expect milder symptoms in the youngest cases if they were only colonized. Is this reasonable?