User login

Computer Navigation Systems in Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review

Could ‘Rx: Pet therapy’ come back to bite you?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

My patient, Ms. A, asked me to write a letter to her landlord (who has a “no pets” policy) stating that she needed to keep her dog in her apartment for “therapeutic” purposes—to provide comfort and reduce her posttraumatic stress (PTSD) and anxiety. I hesitated. Could my written statement make me liable if her dog bit someone?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

Studies showing that animals can help outpatients manage psychiatric conditions have received a lot of publicity lately. As a result, more patients are asking physicians to provide documentation to support having pets in their apartments or letting their pets accompany them on planes and buses and at restaurants and shopping malls.

But sometimes, animals hurt people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that dogs bite 4.5 million Americans each year and that one-fifth of dog bites cause injury that requires medical attention; in 2012, more than 27,000 dog-bite victims needed reconstructive surgery.1 If Dr. B writes a letter to support letting Ms. A keep a dog in her apartment, how likely is Dr. B to incur professional liability?

To answer this question, let’s examine:

• the history and background of “pet therapy”

• types of assistance animals

• potential liability for owners, landlords, and clinicians.

History and background

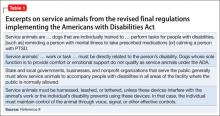

Using animals to improve hospitalized patients’ mental well-being dates back to the 18th century.2 In the late 1980s, medical publications began to document systematically how service dogs whose primary role was to help physically disabled individuals to navigate independently also provided social and emotional benefits.3-7 Since the 1990s, accessibility mandates in Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Table 18) have led to the gradual acceptance of service animals in public places where their presence was previously frowned upon or prohibited.9,10

If service dogs help people with physical problems feel better, it only makes sense that dogs and other animals might lessen emotional ailments, too.11-13 Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud both recognized that involving pets in treatment reduced patients’ depression and anxiety,14 but credit for formally introducing animals into therapy usually goes to psychologist Boris Levinson, whose 1969 book described how his dog Jingles helped troubled children communicate.15 Over the past decade, using animals— trained and untrained—for psychological assistance has become an increasingly popular therapeutic maneuver for diverse mental disorders, including autism, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.16-19

Terminology

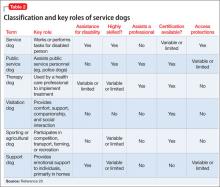

Because animals can provide many types of assistance and support, a variety of terms are used to refer to them: service animals, companion animals, therapy pets, and so on. In certain situations (including the one described by Dr. B), carefully delineating animals’ roles and functions can reduce confusion and misinterpretation by patients, health care professionals, policy makers, and regulators.

Parenti et al20 have proposed a “taxonomy” for assistance dogs based on variables that include:

• performing task related to a disability

• the skill level required of the dog

• who uses the dog

• applicable training standards

• legal protections for the dog and its handler.

Table 220 summarizes this classification system and key variables that differentiate types of assistance dogs.

Certification

Health care facilities often require that visiting dogs have some form of “certification” that they are well behaved, and the ADA and many state statutes require that service dogs and some other animals be “certified” to perform their roles. Yet no federal or state statutes lay out explicit training standards or requirements for certification. Therapy Dogs International21 and Pet Partners22 are 2 organizations that provide certifications accepted by many agencies and organizations.

Assistance Dogs International, an assistance animal advocacy group, has proposed “minimum standards” for training and deployment of service dogs. These include responding to basic obedience commands from the client in public and at home, being able to perform at least 3 tasks to mitigate the client’s disability, teaching the client about dog training and health care, and scheduled follow-ups for skill maintenance. Dogs also should be spayed or neutered, properly vaccinated, nonaggressive, clean, and continent in public places.23

Liability laws

Most U.S. jurisdictions make owners liable for animal-caused injuries, including injuries caused by service dogs.24 In many states (eg, Minnesota25), an owner can be liable for dog-bite injury even if the owner did nothing wrong and had no reason to suspect from prior behavior that the dog might bite someone. Other jurisdictions require evidence of owner negligence, or they allow liability only when bites occur off the owner’s premises26 or if the owner let the dog run loose.27 Many homeowners’ insurance policies include liability coverage for dog bites, and a few companies offer a special canine liability policy.

Landlords often try to bar tenants from having a dog, partly to avoid liability for dog bites. Most states have case law stating that, if a tenant’s apparently friendly dog bites someone, the landlord is not liable for the injury28,29; landlords can be liable only if they know about a dangerous dog and do nothing about it.30 In a recent decision, however, the Kentucky Supreme Court made landlords statutory owners with potential liability for dog bites if they give tenants permission to have dogs “on or about” the rental premises.31

Clinicians and liability

Asking tenants to provide documentation about their need for therapeutic pets has become standard operating procedure for landlords in many states, so Ms. A’s request to Dr. B sounds reasonable. But could Dr. B’s written statement lead to liability if Ms. A’s dog bit and injured someone else?

The best answer is, “It’s conceivable, but really unlikely.” Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, an author and attorney who develops and implements risk management services for psychiatrists, has not seen any claims or case reports on litigation blaming mental health clinicians for injury caused by emotional support pets after the clinicians had written a letter for housing purposes (oral and written communications, April 7-13, 2014).

Dr. B might wonder whether writing a letter for Ms. A would imply that he had evaluated the dog and Ms. A’s ability to control it. Psychiatrists don’t usually discuss—let alone evaluate—the temperament or behavior of their patients’ pets; even if they did they aren’t experts on pet training. Recognizing this, Dr. B’s letter could include a statement to the effect that he was not vouching for the dog’s behavior, but only for how the dog would help Ms. A.

Dr. B also might talk with Ms. A about her need for the dog and whether she had obtained appropriate certification, as discussed above. The ADA provisions pertaining to use and presence of service animals do not apply to dogs that are merely patients’ pets, notwithstanding the genuine emotional benefits that a dog’s companionship might provide. Stating that a patient needs an animal to treat an illness might be fraud if the doctor knew the pet was just a buddy.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can expect that more and more patients will ask them for letters to support having pets accompany them at home or in public. Although liability seems unlikely, cautious psychiatrists can state in such letters that they have not evaluated the animal in question, only the potential benefits that the patient might derive from it.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing articles.

1. Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/ dog-bites/index.html. Updated October 25, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

2. Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010:17-32.

3. Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988;122(1):39-45.

4. Mader B, Hart LA, Bergin B. Social acknowledgments for children with disabilities: effects of service dogs. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1529-1534.

5. Allen K, Blascovich J. The value of service dogs for people with severe ambulatory disabilities. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275(13):1001-1006.

6. Camp MM. The use of service dogs as an adaptive strategy: a qualitative study. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(5):509-517.

7. Allen K, Shykoff BE, Izzo JL Jr. Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):815-820.

8. ADA requirements: service animals. United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section Web site. http://www.ada.gov/service_ animals_2010.htm. Published September 15, 2010. Accessed April 22, 2014.

9. Eames E, Eames T. Interpreting legal mandates. Assistance dogs in medical facilities. Nurs Manage. 1997;28(6):49-51.

10. Houghtalen RP, Doody J. After the ADA: service dogs on inpatient psychiatric units. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):211-217.

11. Wenthold N, Savage TA. Ethical issues with service animals. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):68-74.

12. DiSalvo H, Haiduven D, Johnson N, et al. Who let the dogs out? Infection control did: utility of dogs in health care settings and infection control aspects. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:301-307.

13. Collins DM, Fitzgerald SG, Sachs-Ericsson N, et al. Psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1(1-2):41-48.

14. Coren S. Foreward. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010: xv-xviii.

15. Levinson BM, Mallon GP. Pet-oriented child psychotherapy. 2nd ed. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 1997.

16. Esnayra J. Help from man’s best friend. Psychiatric service dogs are helping consumers deal with the symptoms of mental illness. Behav Healthc. 2007;27(7):30-32.

17. Barak Y, Savorai O, Mavashev S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy for elderly schizophrenic patients: a one year controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):439-442.

18. Burrows KE, Adams CL, Millman ST. Factors affecting behavior and welfare of service dogs for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2008;11(1):42-62.

19. Yount RA, Olmert MD, Lee MR. Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:63-69.

20. Parenti L, Foreman A, Meade BJ, et al. A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):745-756.

21. Testing Requirements. Therapy Dogs International. http:// www.tdi-dog.org/images/TestingBrochure.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2014.

22. How to become a registered therapy animal team. Pet Partners. http://www.petpartners.org/TAPinfo. Accessed April 22, 2014.

23. ADI Guide to Assistance Dog Laws. Assistance Dogs International. http://www.assistancedogsinternational. org/access-and-laws/adi-guide-to-assistance-dog-laws. Accessed April 22, 2014.

24. Id Stat §56-704.

25. Seim v Garavalia, 306 NW2d 806 (Minn 1981).

26. ME Rev Stat title 7, §3961.

27. Chadbourne v Kappaz, 2001 779 A2d 293 (DC App).

28. Stokes v Lyddy, 2002 75 (Conn App 252).

29. Georgianna v Gizzy, 483 NYS2d 892 (NY 1984).

30. Linebaugh v Hyndman, 516 A2d 638 (NJ 1986).

31. Benningfield v Zinsmeister, 367 SW3d 561 (Ky 2012).

Dear Dr. Mossman,

My patient, Ms. A, asked me to write a letter to her landlord (who has a “no pets” policy) stating that she needed to keep her dog in her apartment for “therapeutic” purposes—to provide comfort and reduce her posttraumatic stress (PTSD) and anxiety. I hesitated. Could my written statement make me liable if her dog bit someone?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

Studies showing that animals can help outpatients manage psychiatric conditions have received a lot of publicity lately. As a result, more patients are asking physicians to provide documentation to support having pets in their apartments or letting their pets accompany them on planes and buses and at restaurants and shopping malls.

But sometimes, animals hurt people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that dogs bite 4.5 million Americans each year and that one-fifth of dog bites cause injury that requires medical attention; in 2012, more than 27,000 dog-bite victims needed reconstructive surgery.1 If Dr. B writes a letter to support letting Ms. A keep a dog in her apartment, how likely is Dr. B to incur professional liability?

To answer this question, let’s examine:

• the history and background of “pet therapy”

• types of assistance animals

• potential liability for owners, landlords, and clinicians.

History and background

Using animals to improve hospitalized patients’ mental well-being dates back to the 18th century.2 In the late 1980s, medical publications began to document systematically how service dogs whose primary role was to help physically disabled individuals to navigate independently also provided social and emotional benefits.3-7 Since the 1990s, accessibility mandates in Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Table 18) have led to the gradual acceptance of service animals in public places where their presence was previously frowned upon or prohibited.9,10

If service dogs help people with physical problems feel better, it only makes sense that dogs and other animals might lessen emotional ailments, too.11-13 Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud both recognized that involving pets in treatment reduced patients’ depression and anxiety,14 but credit for formally introducing animals into therapy usually goes to psychologist Boris Levinson, whose 1969 book described how his dog Jingles helped troubled children communicate.15 Over the past decade, using animals— trained and untrained—for psychological assistance has become an increasingly popular therapeutic maneuver for diverse mental disorders, including autism, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.16-19

Terminology

Because animals can provide many types of assistance and support, a variety of terms are used to refer to them: service animals, companion animals, therapy pets, and so on. In certain situations (including the one described by Dr. B), carefully delineating animals’ roles and functions can reduce confusion and misinterpretation by patients, health care professionals, policy makers, and regulators.

Parenti et al20 have proposed a “taxonomy” for assistance dogs based on variables that include:

• performing task related to a disability

• the skill level required of the dog

• who uses the dog

• applicable training standards

• legal protections for the dog and its handler.

Table 220 summarizes this classification system and key variables that differentiate types of assistance dogs.

Certification

Health care facilities often require that visiting dogs have some form of “certification” that they are well behaved, and the ADA and many state statutes require that service dogs and some other animals be “certified” to perform their roles. Yet no federal or state statutes lay out explicit training standards or requirements for certification. Therapy Dogs International21 and Pet Partners22 are 2 organizations that provide certifications accepted by many agencies and organizations.

Assistance Dogs International, an assistance animal advocacy group, has proposed “minimum standards” for training and deployment of service dogs. These include responding to basic obedience commands from the client in public and at home, being able to perform at least 3 tasks to mitigate the client’s disability, teaching the client about dog training and health care, and scheduled follow-ups for skill maintenance. Dogs also should be spayed or neutered, properly vaccinated, nonaggressive, clean, and continent in public places.23

Liability laws

Most U.S. jurisdictions make owners liable for animal-caused injuries, including injuries caused by service dogs.24 In many states (eg, Minnesota25), an owner can be liable for dog-bite injury even if the owner did nothing wrong and had no reason to suspect from prior behavior that the dog might bite someone. Other jurisdictions require evidence of owner negligence, or they allow liability only when bites occur off the owner’s premises26 or if the owner let the dog run loose.27 Many homeowners’ insurance policies include liability coverage for dog bites, and a few companies offer a special canine liability policy.

Landlords often try to bar tenants from having a dog, partly to avoid liability for dog bites. Most states have case law stating that, if a tenant’s apparently friendly dog bites someone, the landlord is not liable for the injury28,29; landlords can be liable only if they know about a dangerous dog and do nothing about it.30 In a recent decision, however, the Kentucky Supreme Court made landlords statutory owners with potential liability for dog bites if they give tenants permission to have dogs “on or about” the rental premises.31

Clinicians and liability

Asking tenants to provide documentation about their need for therapeutic pets has become standard operating procedure for landlords in many states, so Ms. A’s request to Dr. B sounds reasonable. But could Dr. B’s written statement lead to liability if Ms. A’s dog bit and injured someone else?

The best answer is, “It’s conceivable, but really unlikely.” Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, an author and attorney who develops and implements risk management services for psychiatrists, has not seen any claims or case reports on litigation blaming mental health clinicians for injury caused by emotional support pets after the clinicians had written a letter for housing purposes (oral and written communications, April 7-13, 2014).

Dr. B might wonder whether writing a letter for Ms. A would imply that he had evaluated the dog and Ms. A’s ability to control it. Psychiatrists don’t usually discuss—let alone evaluate—the temperament or behavior of their patients’ pets; even if they did they aren’t experts on pet training. Recognizing this, Dr. B’s letter could include a statement to the effect that he was not vouching for the dog’s behavior, but only for how the dog would help Ms. A.

Dr. B also might talk with Ms. A about her need for the dog and whether she had obtained appropriate certification, as discussed above. The ADA provisions pertaining to use and presence of service animals do not apply to dogs that are merely patients’ pets, notwithstanding the genuine emotional benefits that a dog’s companionship might provide. Stating that a patient needs an animal to treat an illness might be fraud if the doctor knew the pet was just a buddy.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can expect that more and more patients will ask them for letters to support having pets accompany them at home or in public. Although liability seems unlikely, cautious psychiatrists can state in such letters that they have not evaluated the animal in question, only the potential benefits that the patient might derive from it.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing articles.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

My patient, Ms. A, asked me to write a letter to her landlord (who has a “no pets” policy) stating that she needed to keep her dog in her apartment for “therapeutic” purposes—to provide comfort and reduce her posttraumatic stress (PTSD) and anxiety. I hesitated. Could my written statement make me liable if her dog bit someone?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

Studies showing that animals can help outpatients manage psychiatric conditions have received a lot of publicity lately. As a result, more patients are asking physicians to provide documentation to support having pets in their apartments or letting their pets accompany them on planes and buses and at restaurants and shopping malls.

But sometimes, animals hurt people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that dogs bite 4.5 million Americans each year and that one-fifth of dog bites cause injury that requires medical attention; in 2012, more than 27,000 dog-bite victims needed reconstructive surgery.1 If Dr. B writes a letter to support letting Ms. A keep a dog in her apartment, how likely is Dr. B to incur professional liability?

To answer this question, let’s examine:

• the history and background of “pet therapy”

• types of assistance animals

• potential liability for owners, landlords, and clinicians.

History and background

Using animals to improve hospitalized patients’ mental well-being dates back to the 18th century.2 In the late 1980s, medical publications began to document systematically how service dogs whose primary role was to help physically disabled individuals to navigate independently also provided social and emotional benefits.3-7 Since the 1990s, accessibility mandates in Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Table 18) have led to the gradual acceptance of service animals in public places where their presence was previously frowned upon or prohibited.9,10

If service dogs help people with physical problems feel better, it only makes sense that dogs and other animals might lessen emotional ailments, too.11-13 Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud both recognized that involving pets in treatment reduced patients’ depression and anxiety,14 but credit for formally introducing animals into therapy usually goes to psychologist Boris Levinson, whose 1969 book described how his dog Jingles helped troubled children communicate.15 Over the past decade, using animals— trained and untrained—for psychological assistance has become an increasingly popular therapeutic maneuver for diverse mental disorders, including autism, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.16-19

Terminology

Because animals can provide many types of assistance and support, a variety of terms are used to refer to them: service animals, companion animals, therapy pets, and so on. In certain situations (including the one described by Dr. B), carefully delineating animals’ roles and functions can reduce confusion and misinterpretation by patients, health care professionals, policy makers, and regulators.

Parenti et al20 have proposed a “taxonomy” for assistance dogs based on variables that include:

• performing task related to a disability

• the skill level required of the dog

• who uses the dog

• applicable training standards

• legal protections for the dog and its handler.

Table 220 summarizes this classification system and key variables that differentiate types of assistance dogs.

Certification

Health care facilities often require that visiting dogs have some form of “certification” that they are well behaved, and the ADA and many state statutes require that service dogs and some other animals be “certified” to perform their roles. Yet no federal or state statutes lay out explicit training standards or requirements for certification. Therapy Dogs International21 and Pet Partners22 are 2 organizations that provide certifications accepted by many agencies and organizations.

Assistance Dogs International, an assistance animal advocacy group, has proposed “minimum standards” for training and deployment of service dogs. These include responding to basic obedience commands from the client in public and at home, being able to perform at least 3 tasks to mitigate the client’s disability, teaching the client about dog training and health care, and scheduled follow-ups for skill maintenance. Dogs also should be spayed or neutered, properly vaccinated, nonaggressive, clean, and continent in public places.23

Liability laws

Most U.S. jurisdictions make owners liable for animal-caused injuries, including injuries caused by service dogs.24 In many states (eg, Minnesota25), an owner can be liable for dog-bite injury even if the owner did nothing wrong and had no reason to suspect from prior behavior that the dog might bite someone. Other jurisdictions require evidence of owner negligence, or they allow liability only when bites occur off the owner’s premises26 or if the owner let the dog run loose.27 Many homeowners’ insurance policies include liability coverage for dog bites, and a few companies offer a special canine liability policy.

Landlords often try to bar tenants from having a dog, partly to avoid liability for dog bites. Most states have case law stating that, if a tenant’s apparently friendly dog bites someone, the landlord is not liable for the injury28,29; landlords can be liable only if they know about a dangerous dog and do nothing about it.30 In a recent decision, however, the Kentucky Supreme Court made landlords statutory owners with potential liability for dog bites if they give tenants permission to have dogs “on or about” the rental premises.31

Clinicians and liability

Asking tenants to provide documentation about their need for therapeutic pets has become standard operating procedure for landlords in many states, so Ms. A’s request to Dr. B sounds reasonable. But could Dr. B’s written statement lead to liability if Ms. A’s dog bit and injured someone else?

The best answer is, “It’s conceivable, but really unlikely.” Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD, an author and attorney who develops and implements risk management services for psychiatrists, has not seen any claims or case reports on litigation blaming mental health clinicians for injury caused by emotional support pets after the clinicians had written a letter for housing purposes (oral and written communications, April 7-13, 2014).

Dr. B might wonder whether writing a letter for Ms. A would imply that he had evaluated the dog and Ms. A’s ability to control it. Psychiatrists don’t usually discuss—let alone evaluate—the temperament or behavior of their patients’ pets; even if they did they aren’t experts on pet training. Recognizing this, Dr. B’s letter could include a statement to the effect that he was not vouching for the dog’s behavior, but only for how the dog would help Ms. A.

Dr. B also might talk with Ms. A about her need for the dog and whether she had obtained appropriate certification, as discussed above. The ADA provisions pertaining to use and presence of service animals do not apply to dogs that are merely patients’ pets, notwithstanding the genuine emotional benefits that a dog’s companionship might provide. Stating that a patient needs an animal to treat an illness might be fraud if the doctor knew the pet was just a buddy.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists can expect that more and more patients will ask them for letters to support having pets accompany them at home or in public. Although liability seems unlikely, cautious psychiatrists can state in such letters that they have not evaluated the animal in question, only the potential benefits that the patient might derive from it.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing articles.

1. Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/ dog-bites/index.html. Updated October 25, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

2. Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010:17-32.

3. Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988;122(1):39-45.

4. Mader B, Hart LA, Bergin B. Social acknowledgments for children with disabilities: effects of service dogs. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1529-1534.

5. Allen K, Blascovich J. The value of service dogs for people with severe ambulatory disabilities. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275(13):1001-1006.

6. Camp MM. The use of service dogs as an adaptive strategy: a qualitative study. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(5):509-517.

7. Allen K, Shykoff BE, Izzo JL Jr. Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):815-820.

8. ADA requirements: service animals. United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section Web site. http://www.ada.gov/service_ animals_2010.htm. Published September 15, 2010. Accessed April 22, 2014.

9. Eames E, Eames T. Interpreting legal mandates. Assistance dogs in medical facilities. Nurs Manage. 1997;28(6):49-51.

10. Houghtalen RP, Doody J. After the ADA: service dogs on inpatient psychiatric units. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):211-217.

11. Wenthold N, Savage TA. Ethical issues with service animals. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):68-74.

12. DiSalvo H, Haiduven D, Johnson N, et al. Who let the dogs out? Infection control did: utility of dogs in health care settings and infection control aspects. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:301-307.

13. Collins DM, Fitzgerald SG, Sachs-Ericsson N, et al. Psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1(1-2):41-48.

14. Coren S. Foreward. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010: xv-xviii.

15. Levinson BM, Mallon GP. Pet-oriented child psychotherapy. 2nd ed. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 1997.

16. Esnayra J. Help from man’s best friend. Psychiatric service dogs are helping consumers deal with the symptoms of mental illness. Behav Healthc. 2007;27(7):30-32.

17. Barak Y, Savorai O, Mavashev S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy for elderly schizophrenic patients: a one year controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):439-442.

18. Burrows KE, Adams CL, Millman ST. Factors affecting behavior and welfare of service dogs for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2008;11(1):42-62.

19. Yount RA, Olmert MD, Lee MR. Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:63-69.

20. Parenti L, Foreman A, Meade BJ, et al. A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):745-756.

21. Testing Requirements. Therapy Dogs International. http:// www.tdi-dog.org/images/TestingBrochure.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2014.

22. How to become a registered therapy animal team. Pet Partners. http://www.petpartners.org/TAPinfo. Accessed April 22, 2014.

23. ADI Guide to Assistance Dog Laws. Assistance Dogs International. http://www.assistancedogsinternational. org/access-and-laws/adi-guide-to-assistance-dog-laws. Accessed April 22, 2014.

24. Id Stat §56-704.

25. Seim v Garavalia, 306 NW2d 806 (Minn 1981).

26. ME Rev Stat title 7, §3961.

27. Chadbourne v Kappaz, 2001 779 A2d 293 (DC App).

28. Stokes v Lyddy, 2002 75 (Conn App 252).

29. Georgianna v Gizzy, 483 NYS2d 892 (NY 1984).

30. Linebaugh v Hyndman, 516 A2d 638 (NJ 1986).

31. Benningfield v Zinsmeister, 367 SW3d 561 (Ky 2012).

1. Dog Bites. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/ dog-bites/index.html. Updated October 25, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2014.

2. Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in historical perspective. In Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010:17-32.

3. Eddy J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgments of people in wheelchairs. J Psychol. 1988;122(1):39-45.

4. Mader B, Hart LA, Bergin B. Social acknowledgments for children with disabilities: effects of service dogs. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1529-1534.

5. Allen K, Blascovich J. The value of service dogs for people with severe ambulatory disabilities. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275(13):1001-1006.

6. Camp MM. The use of service dogs as an adaptive strategy: a qualitative study. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(5):509-517.

7. Allen K, Shykoff BE, Izzo JL Jr. Pet ownership, but not ace inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):815-820.

8. ADA requirements: service animals. United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section Web site. http://www.ada.gov/service_ animals_2010.htm. Published September 15, 2010. Accessed April 22, 2014.

9. Eames E, Eames T. Interpreting legal mandates. Assistance dogs in medical facilities. Nurs Manage. 1997;28(6):49-51.

10. Houghtalen RP, Doody J. After the ADA: service dogs on inpatient psychiatric units. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):211-217.

11. Wenthold N, Savage TA. Ethical issues with service animals. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(2):68-74.

12. DiSalvo H, Haiduven D, Johnson N, et al. Who let the dogs out? Infection control did: utility of dogs in health care settings and infection control aspects. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:301-307.

13. Collins DM, Fitzgerald SG, Sachs-Ericsson N, et al. Psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2006;1(1-2):41-48.

14. Coren S. Foreward. In: Fine AH, ed. Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2010: xv-xviii.

15. Levinson BM, Mallon GP. Pet-oriented child psychotherapy. 2nd ed. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 1997.

16. Esnayra J. Help from man’s best friend. Psychiatric service dogs are helping consumers deal with the symptoms of mental illness. Behav Healthc. 2007;27(7):30-32.

17. Barak Y, Savorai O, Mavashev S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy for elderly schizophrenic patients: a one year controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):439-442.

18. Burrows KE, Adams CL, Millman ST. Factors affecting behavior and welfare of service dogs for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2008;11(1):42-62.

19. Yount RA, Olmert MD, Lee MR. Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members. US Army Med Dep J. 2012:63-69.

20. Parenti L, Foreman A, Meade BJ, et al. A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):745-756.

21. Testing Requirements. Therapy Dogs International. http:// www.tdi-dog.org/images/TestingBrochure.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2014.

22. How to become a registered therapy animal team. Pet Partners. http://www.petpartners.org/TAPinfo. Accessed April 22, 2014.

23. ADI Guide to Assistance Dog Laws. Assistance Dogs International. http://www.assistancedogsinternational. org/access-and-laws/adi-guide-to-assistance-dog-laws. Accessed April 22, 2014.

24. Id Stat §56-704.

25. Seim v Garavalia, 306 NW2d 806 (Minn 1981).

26. ME Rev Stat title 7, §3961.

27. Chadbourne v Kappaz, 2001 779 A2d 293 (DC App).

28. Stokes v Lyddy, 2002 75 (Conn App 252).

29. Georgianna v Gizzy, 483 NYS2d 892 (NY 1984).

30. Linebaugh v Hyndman, 516 A2d 638 (NJ 1986).

31. Benningfield v Zinsmeister, 367 SW3d 561 (Ky 2012).

Delaying clopidogrel can increase risk of MI, death

Credit: CDC

Patients who delay filling a prescription of clopidogrel after coronary stenting may increase their risk of recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) and death, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Researchers analyzed records of more than 15,000 patients who received drug-eluting or bare metal stents.

Roughly 30% of patients in each group failed to fill their prescription of the anticoagulant clopidogrel within 3 days of hospital discharge.

And this roughly doubled the patients’ risk of death and recurrent MI, regardless of their stent type.

“It is very important that patients take clopidogrel after having a coronary stent implanted to prevent blood clots forming within the stent,” said study author Nicholas Cruden, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh in the UK.

He and his colleagues analyzed hospital administrative, community pharmacy, and cardiac revascularization data from all patients who received a coronary stent in British Columbia between 2004 and 2006, with follow-up out to 2 years.

Of the 15,629 patients, 3599 had received at least 1 drug-eluting stent (DES), and 12,030 had received a bare metal stent (BMS). Thirty percent (n=1064) of patients in the DES group, and 31% (n=3758) of patients in the BMS group failed to fill their prescription for clopidogrel within 3 days of hospital discharge.

And a delay of more than 3 days was predictive of mortality and recurrent MI, regardless of the stent type. The hazard ratios (HRs) for mortality were 2.4 for the DES group and 2.2 for the BMS group. The HRs for recurrent MI were 2.0 and 1.8, respectively.

The excess risk associated with a delay in filling the prescription was greatest in the immediate period after hospital discharge—up to 30 days. In all patients, the HRs were 5.5 for mortality and 3.1 for recurrent MI.

Delaying filling the prescription for more than 3 days remained an independent predictor of death and MI beyond 30 days from hospital discharge. The HRs were 2.1 and 2.0, respectively, for patients in the DES group and 2.0 and 1.8, respectively, for patients in the BMS group.

“This study highlights the importance of ensuring patients have access to medications as soon as they leave the hospital,” Dr Cruden said. “Even a delay of a day or 2 was associated with worse outcomes.”

Discharging patients from the hospital with enough medicine for the highest-risk period (the first month or so) could help, he added. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Patients who delay filling a prescription of clopidogrel after coronary stenting may increase their risk of recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) and death, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Researchers analyzed records of more than 15,000 patients who received drug-eluting or bare metal stents.

Roughly 30% of patients in each group failed to fill their prescription of the anticoagulant clopidogrel within 3 days of hospital discharge.

And this roughly doubled the patients’ risk of death and recurrent MI, regardless of their stent type.

“It is very important that patients take clopidogrel after having a coronary stent implanted to prevent blood clots forming within the stent,” said study author Nicholas Cruden, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh in the UK.

He and his colleagues analyzed hospital administrative, community pharmacy, and cardiac revascularization data from all patients who received a coronary stent in British Columbia between 2004 and 2006, with follow-up out to 2 years.

Of the 15,629 patients, 3599 had received at least 1 drug-eluting stent (DES), and 12,030 had received a bare metal stent (BMS). Thirty percent (n=1064) of patients in the DES group, and 31% (n=3758) of patients in the BMS group failed to fill their prescription for clopidogrel within 3 days of hospital discharge.

And a delay of more than 3 days was predictive of mortality and recurrent MI, regardless of the stent type. The hazard ratios (HRs) for mortality were 2.4 for the DES group and 2.2 for the BMS group. The HRs for recurrent MI were 2.0 and 1.8, respectively.

The excess risk associated with a delay in filling the prescription was greatest in the immediate period after hospital discharge—up to 30 days. In all patients, the HRs were 5.5 for mortality and 3.1 for recurrent MI.

Delaying filling the prescription for more than 3 days remained an independent predictor of death and MI beyond 30 days from hospital discharge. The HRs were 2.1 and 2.0, respectively, for patients in the DES group and 2.0 and 1.8, respectively, for patients in the BMS group.

“This study highlights the importance of ensuring patients have access to medications as soon as they leave the hospital,” Dr Cruden said. “Even a delay of a day or 2 was associated with worse outcomes.”

Discharging patients from the hospital with enough medicine for the highest-risk period (the first month or so) could help, he added. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Patients who delay filling a prescription of clopidogrel after coronary stenting may increase their risk of recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) and death, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Researchers analyzed records of more than 15,000 patients who received drug-eluting or bare metal stents.

Roughly 30% of patients in each group failed to fill their prescription of the anticoagulant clopidogrel within 3 days of hospital discharge.

And this roughly doubled the patients’ risk of death and recurrent MI, regardless of their stent type.

“It is very important that patients take clopidogrel after having a coronary stent implanted to prevent blood clots forming within the stent,” said study author Nicholas Cruden, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh in the UK.

He and his colleagues analyzed hospital administrative, community pharmacy, and cardiac revascularization data from all patients who received a coronary stent in British Columbia between 2004 and 2006, with follow-up out to 2 years.

Of the 15,629 patients, 3599 had received at least 1 drug-eluting stent (DES), and 12,030 had received a bare metal stent (BMS). Thirty percent (n=1064) of patients in the DES group, and 31% (n=3758) of patients in the BMS group failed to fill their prescription for clopidogrel within 3 days of hospital discharge.

And a delay of more than 3 days was predictive of mortality and recurrent MI, regardless of the stent type. The hazard ratios (HRs) for mortality were 2.4 for the DES group and 2.2 for the BMS group. The HRs for recurrent MI were 2.0 and 1.8, respectively.

The excess risk associated with a delay in filling the prescription was greatest in the immediate period after hospital discharge—up to 30 days. In all patients, the HRs were 5.5 for mortality and 3.1 for recurrent MI.

Delaying filling the prescription for more than 3 days remained an independent predictor of death and MI beyond 30 days from hospital discharge. The HRs were 2.1 and 2.0, respectively, for patients in the DES group and 2.0 and 1.8, respectively, for patients in the BMS group.

“This study highlights the importance of ensuring patients have access to medications as soon as they leave the hospital,” Dr Cruden said. “Even a delay of a day or 2 was associated with worse outcomes.”

Discharging patients from the hospital with enough medicine for the highest-risk period (the first month or so) could help, he added. ![]()

Low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia prevention: Ready for prime time, but as a “re-run” or as a “new series”?

In November 2013, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published the results of its Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy.1 The Task Force aimed to help clinicians become familiar with the state of research in hypertension during pregnancy as well as to assist us in standardizing management approaches to such patients.

The Task Force reported that, worldwide, hypertensive disorders complicate approximately 10% of pregnancies. In addition, in the United States, the past 20 years have brought a 25% increase in the incidence of preeclampsia. According to past ACOG President James N. Martin, Jr, MD, in the last 10 years, the pathophysiology of preeclampsia has become better understood, but the etiology remains unclear and evidence that has emerged to guide therapy has not translated into clinical practice.1

Related articles:

The latest guidance from ACOG on hypertension in pregnancy. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD (Audiocast, January 2014)

Update on Obstetrics. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD (January 2014)

The Task Force document contained 60 recommendations for the prevention, prediction, and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, HELLP syndrome, and preeclampsia superimposed on an underlying hypertensive disorder (see box below). One recommendation was that women at high risk for preeclampsia, particularly those with a history of preeclampsia that required delivery before 34 weeks, could possibly benefit from taking aspirin (60–81 mg) daily starting at the end of the first trimester. They further noted that this benefit could include prevention of recurrent severe preeclampsia, or at least a reduction in recurrence risk.

The ACOG Task Force made its recommendation based on results of a meta-analysis of low-dose aspirin trials, involving more than 30,000 patients,2 suggesting a small decrease in the risk of preeclampsia and associated morbidity. More precise risk reduction estimates were difficult to make due to the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. And the Task Force further stated that this (low-dose aspirin) approach had no demonstrable acute adverse fetal effects, although long-term adverse effects could not be entirely excluded based on the current data.

Unfortunately, according to the ACOG document, the strength of the evidence supporting their recommendation was “moderate” and the strength of the recommendation was “qualified” so, not exactly a resounding endorsement of this approach, but a recommendation nonetheless.

OBSTETRIC PRACTICE CHANGERS 2014

Hypertension and pregnancy and preventing the first cesarean delivery

John T. Repke, MD, author of this Guest Editorial, recently sat down with Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, fellow OBG Management Board of Editors Member and author of this month’s "Update on Operative Vaginal Delivery." Their discussion focused on individual takeaways from ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy guidelines and the recent joint ACOG−Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine report on emerging clinical and scientific advances in safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery.

From their conversation:

Dr. Repke: About 60 recommendations came out of ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy document; only six had high-quality supporting evidence, and I think most practitioners already did them. Many really were based on either moderate- or low-quality evidence, with qualified recommendations. I think this has led to confusion.

Dr. Norwitz, how do you answer when a clinician asks you, “Is this gestational hypertension or is this preeclampsia?”

Click here to access the audiocast with full transcript.

Data suggest aspirin for high-risk women could be reasonable

A recent study by Henderson and colleagues presented a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the potential for low-dose aspirin to prevent morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia.3 The design was a meta-analysis of 28 studies: two large, multisite, randomized clinical trials (RCTs); 13 smaller RCTs of high-risk women, of which eight were deemed “good quality”; and six RCTs and two observational studies of average-risk women, of which seven were deemed to be good quality.

The results essentially supported the notion that low-dose aspirin had a beneficial effect with respect to prevention of preeclampsia and perinatal morbidity in women at high risk for preeclampsia. Additionally, no harmful effects were identified, although the authors acknowledged potential rare or long-term harm could not be excluded.

Questions remain

While somewhat gratifying, the results of the USPSTF systematic review still leave many questions. First, the dose of aspirin used in the studies analyzed ranged from 50 mg/d to 150 mg/d. In the United States, “low-dose” aspirin is usually prescribed at 81 mg/d, so the applicability of this review’s findings to US clinical practice is not exact. Second, the authors acknowledged that the putative positive effects observed could be secondary to so-called “small study effects,” and that when only the larger studies were analyzed the effects were less impressive.

Related article: A stepwise approach to managing eclampsia and other hypertensive emergencies. Baha M. Sibai (October 2013)

In my opinion, both the USPSTF study and the recommendations from the ACOG Task Force provide some reassurance for clinicians that the use of daily, low-dose aspirin by women at high risk for preeclampsia probably does afford some benefit, and seems to be a safe approach—as we have known from the initial Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) trial published in 1993 on low-risk women4 and the follow-up MFMU study on high-risk women.5

The need for additional studies is clear, however. The idea that preeclampsia is the same in every patient would seem to make no more sense than thinking all cancer is the same, with the same risk factors, the same epidemiology and pathophysiology, and the same response to similar treatments. Fundamentally, we need to further explore the different pathways through which preeclampsia develops in women and then apply the strategy best suited to treating (or preventing) their form of the disease—a personalized medicine approach.

In the meantime, most patients who have delivered at 34 weeks or less because of preeclampsia and who are contemplating another pregnancy are really not interested in hearing us tell them that we cannot do anything to prevent recurrent preeclampsia because we are awaiting further studies. At least the ACOG recommendations and the results of the USPSTF’s systematic review provide us with a reasonable, although perhaps not yet optimal, therapeutic option.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations to improve outcomes in women who have eclampsia. Baha M. Sibai (November 2011)

The bottom line

In my own practice, I discuss the option of initiating low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) as early as 12 weeks’ gestation for patients who had either prior early-onset preeclampsia requiring delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation or preeclampsia during more than one pregnancy.

QUICK POLL

Do you offer low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention?

When faced with a patient with prior preeclampsia in more than one pregnancy or with preeclampsia that resulted in delivery prior to 34 weeks, do you offer low-dose aspirin as an option for preventing preeclampsia?

Visit the Quick Poll on the right column of the OBGManagement.com home page to register your answer and see how your colleagues voted.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

- ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131.

- Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Heher S, King JF. Antiplatelet agents for preventing preeclampsia and its complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD004659.

- Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O’Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: A systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [published online ahead of print April 8, 2014]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M13-2844.

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy, nulliparous pregnant women. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(17):1213–1218.

- Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):701–705.

In November 2013, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published the results of its Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy.1 The Task Force aimed to help clinicians become familiar with the state of research in hypertension during pregnancy as well as to assist us in standardizing management approaches to such patients.

The Task Force reported that, worldwide, hypertensive disorders complicate approximately 10% of pregnancies. In addition, in the United States, the past 20 years have brought a 25% increase in the incidence of preeclampsia. According to past ACOG President James N. Martin, Jr, MD, in the last 10 years, the pathophysiology of preeclampsia has become better understood, but the etiology remains unclear and evidence that has emerged to guide therapy has not translated into clinical practice.1

Related articles:

The latest guidance from ACOG on hypertension in pregnancy. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD (Audiocast, January 2014)

Update on Obstetrics. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD (January 2014)

The Task Force document contained 60 recommendations for the prevention, prediction, and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, HELLP syndrome, and preeclampsia superimposed on an underlying hypertensive disorder (see box below). One recommendation was that women at high risk for preeclampsia, particularly those with a history of preeclampsia that required delivery before 34 weeks, could possibly benefit from taking aspirin (60–81 mg) daily starting at the end of the first trimester. They further noted that this benefit could include prevention of recurrent severe preeclampsia, or at least a reduction in recurrence risk.

The ACOG Task Force made its recommendation based on results of a meta-analysis of low-dose aspirin trials, involving more than 30,000 patients,2 suggesting a small decrease in the risk of preeclampsia and associated morbidity. More precise risk reduction estimates were difficult to make due to the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. And the Task Force further stated that this (low-dose aspirin) approach had no demonstrable acute adverse fetal effects, although long-term adverse effects could not be entirely excluded based on the current data.

Unfortunately, according to the ACOG document, the strength of the evidence supporting their recommendation was “moderate” and the strength of the recommendation was “qualified” so, not exactly a resounding endorsement of this approach, but a recommendation nonetheless.

OBSTETRIC PRACTICE CHANGERS 2014

Hypertension and pregnancy and preventing the first cesarean delivery

John T. Repke, MD, author of this Guest Editorial, recently sat down with Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, fellow OBG Management Board of Editors Member and author of this month’s "Update on Operative Vaginal Delivery." Their discussion focused on individual takeaways from ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy guidelines and the recent joint ACOG−Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine report on emerging clinical and scientific advances in safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery.

From their conversation:

Dr. Repke: About 60 recommendations came out of ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy document; only six had high-quality supporting evidence, and I think most practitioners already did them. Many really were based on either moderate- or low-quality evidence, with qualified recommendations. I think this has led to confusion.

Dr. Norwitz, how do you answer when a clinician asks you, “Is this gestational hypertension or is this preeclampsia?”

Click here to access the audiocast with full transcript.

Data suggest aspirin for high-risk women could be reasonable

A recent study by Henderson and colleagues presented a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the potential for low-dose aspirin to prevent morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia.3 The design was a meta-analysis of 28 studies: two large, multisite, randomized clinical trials (RCTs); 13 smaller RCTs of high-risk women, of which eight were deemed “good quality”; and six RCTs and two observational studies of average-risk women, of which seven were deemed to be good quality.

The results essentially supported the notion that low-dose aspirin had a beneficial effect with respect to prevention of preeclampsia and perinatal morbidity in women at high risk for preeclampsia. Additionally, no harmful effects were identified, although the authors acknowledged potential rare or long-term harm could not be excluded.

Questions remain

While somewhat gratifying, the results of the USPSTF systematic review still leave many questions. First, the dose of aspirin used in the studies analyzed ranged from 50 mg/d to 150 mg/d. In the United States, “low-dose” aspirin is usually prescribed at 81 mg/d, so the applicability of this review’s findings to US clinical practice is not exact. Second, the authors acknowledged that the putative positive effects observed could be secondary to so-called “small study effects,” and that when only the larger studies were analyzed the effects were less impressive.

Related article: A stepwise approach to managing eclampsia and other hypertensive emergencies. Baha M. Sibai (October 2013)

In my opinion, both the USPSTF study and the recommendations from the ACOG Task Force provide some reassurance for clinicians that the use of daily, low-dose aspirin by women at high risk for preeclampsia probably does afford some benefit, and seems to be a safe approach—as we have known from the initial Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) trial published in 1993 on low-risk women4 and the follow-up MFMU study on high-risk women.5

The need for additional studies is clear, however. The idea that preeclampsia is the same in every patient would seem to make no more sense than thinking all cancer is the same, with the same risk factors, the same epidemiology and pathophysiology, and the same response to similar treatments. Fundamentally, we need to further explore the different pathways through which preeclampsia develops in women and then apply the strategy best suited to treating (or preventing) their form of the disease—a personalized medicine approach.

In the meantime, most patients who have delivered at 34 weeks or less because of preeclampsia and who are contemplating another pregnancy are really not interested in hearing us tell them that we cannot do anything to prevent recurrent preeclampsia because we are awaiting further studies. At least the ACOG recommendations and the results of the USPSTF’s systematic review provide us with a reasonable, although perhaps not yet optimal, therapeutic option.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations to improve outcomes in women who have eclampsia. Baha M. Sibai (November 2011)

The bottom line

In my own practice, I discuss the option of initiating low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) as early as 12 weeks’ gestation for patients who had either prior early-onset preeclampsia requiring delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation or preeclampsia during more than one pregnancy.

QUICK POLL

Do you offer low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention?

When faced with a patient with prior preeclampsia in more than one pregnancy or with preeclampsia that resulted in delivery prior to 34 weeks, do you offer low-dose aspirin as an option for preventing preeclampsia?

Visit the Quick Poll on the right column of the OBGManagement.com home page to register your answer and see how your colleagues voted.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

In November 2013, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published the results of its Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy.1 The Task Force aimed to help clinicians become familiar with the state of research in hypertension during pregnancy as well as to assist us in standardizing management approaches to such patients.

The Task Force reported that, worldwide, hypertensive disorders complicate approximately 10% of pregnancies. In addition, in the United States, the past 20 years have brought a 25% increase in the incidence of preeclampsia. According to past ACOG President James N. Martin, Jr, MD, in the last 10 years, the pathophysiology of preeclampsia has become better understood, but the etiology remains unclear and evidence that has emerged to guide therapy has not translated into clinical practice.1

Related articles:

The latest guidance from ACOG on hypertension in pregnancy. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD (Audiocast, January 2014)

Update on Obstetrics. Jaimey E. Pauli, MD, and John T. Repke, MD (January 2014)

The Task Force document contained 60 recommendations for the prevention, prediction, and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, HELLP syndrome, and preeclampsia superimposed on an underlying hypertensive disorder (see box below). One recommendation was that women at high risk for preeclampsia, particularly those with a history of preeclampsia that required delivery before 34 weeks, could possibly benefit from taking aspirin (60–81 mg) daily starting at the end of the first trimester. They further noted that this benefit could include prevention of recurrent severe preeclampsia, or at least a reduction in recurrence risk.

The ACOG Task Force made its recommendation based on results of a meta-analysis of low-dose aspirin trials, involving more than 30,000 patients,2 suggesting a small decrease in the risk of preeclampsia and associated morbidity. More precise risk reduction estimates were difficult to make due to the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. And the Task Force further stated that this (low-dose aspirin) approach had no demonstrable acute adverse fetal effects, although long-term adverse effects could not be entirely excluded based on the current data.

Unfortunately, according to the ACOG document, the strength of the evidence supporting their recommendation was “moderate” and the strength of the recommendation was “qualified” so, not exactly a resounding endorsement of this approach, but a recommendation nonetheless.

OBSTETRIC PRACTICE CHANGERS 2014

Hypertension and pregnancy and preventing the first cesarean delivery

John T. Repke, MD, author of this Guest Editorial, recently sat down with Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, fellow OBG Management Board of Editors Member and author of this month’s "Update on Operative Vaginal Delivery." Their discussion focused on individual takeaways from ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy guidelines and the recent joint ACOG−Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine report on emerging clinical and scientific advances in safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery.

From their conversation:

Dr. Repke: About 60 recommendations came out of ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy document; only six had high-quality supporting evidence, and I think most practitioners already did them. Many really were based on either moderate- or low-quality evidence, with qualified recommendations. I think this has led to confusion.

Dr. Norwitz, how do you answer when a clinician asks you, “Is this gestational hypertension or is this preeclampsia?”

Click here to access the audiocast with full transcript.

Data suggest aspirin for high-risk women could be reasonable

A recent study by Henderson and colleagues presented a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the potential for low-dose aspirin to prevent morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia.3 The design was a meta-analysis of 28 studies: two large, multisite, randomized clinical trials (RCTs); 13 smaller RCTs of high-risk women, of which eight were deemed “good quality”; and six RCTs and two observational studies of average-risk women, of which seven were deemed to be good quality.

The results essentially supported the notion that low-dose aspirin had a beneficial effect with respect to prevention of preeclampsia and perinatal morbidity in women at high risk for preeclampsia. Additionally, no harmful effects were identified, although the authors acknowledged potential rare or long-term harm could not be excluded.

Questions remain

While somewhat gratifying, the results of the USPSTF systematic review still leave many questions. First, the dose of aspirin used in the studies analyzed ranged from 50 mg/d to 150 mg/d. In the United States, “low-dose” aspirin is usually prescribed at 81 mg/d, so the applicability of this review’s findings to US clinical practice is not exact. Second, the authors acknowledged that the putative positive effects observed could be secondary to so-called “small study effects,” and that when only the larger studies were analyzed the effects were less impressive.

Related article: A stepwise approach to managing eclampsia and other hypertensive emergencies. Baha M. Sibai (October 2013)

In my opinion, both the USPSTF study and the recommendations from the ACOG Task Force provide some reassurance for clinicians that the use of daily, low-dose aspirin by women at high risk for preeclampsia probably does afford some benefit, and seems to be a safe approach—as we have known from the initial Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) trial published in 1993 on low-risk women4 and the follow-up MFMU study on high-risk women.5

The need for additional studies is clear, however. The idea that preeclampsia is the same in every patient would seem to make no more sense than thinking all cancer is the same, with the same risk factors, the same epidemiology and pathophysiology, and the same response to similar treatments. Fundamentally, we need to further explore the different pathways through which preeclampsia develops in women and then apply the strategy best suited to treating (or preventing) their form of the disease—a personalized medicine approach.

In the meantime, most patients who have delivered at 34 weeks or less because of preeclampsia and who are contemplating another pregnancy are really not interested in hearing us tell them that we cannot do anything to prevent recurrent preeclampsia because we are awaiting further studies. At least the ACOG recommendations and the results of the USPSTF’s systematic review provide us with a reasonable, although perhaps not yet optimal, therapeutic option.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations to improve outcomes in women who have eclampsia. Baha M. Sibai (November 2011)

The bottom line

In my own practice, I discuss the option of initiating low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) as early as 12 weeks’ gestation for patients who had either prior early-onset preeclampsia requiring delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation or preeclampsia during more than one pregnancy.

QUICK POLL

Do you offer low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention?

When faced with a patient with prior preeclampsia in more than one pregnancy or with preeclampsia that resulted in delivery prior to 34 weeks, do you offer low-dose aspirin as an option for preventing preeclampsia?

Visit the Quick Poll on the right column of the OBGManagement.com home page to register your answer and see how your colleagues voted.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

- ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131.

- Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Heher S, King JF. Antiplatelet agents for preventing preeclampsia and its complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD004659.

- Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O’Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: A systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [published online ahead of print April 8, 2014]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M13-2844.

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy, nulliparous pregnant women. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(17):1213–1218.

- Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):701–705.

- ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131.

- Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Heher S, King JF. Antiplatelet agents for preventing preeclampsia and its complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD004659.

- Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O’Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: A systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [published online ahead of print April 8, 2014]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M13-2844.

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy, nulliparous pregnant women. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(17):1213–1218.

- Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):701–705.

Have you read Dr. Errol R. Norwitz's Update on Operative Vaginal Delivery? Click here to access.

Woman loses both legs after salpingectomy: $64.3M award

Woman loses both legs after salpingectomy: $64.3M award

Due to an ectopic pregnancy, a 29-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic salpingectomy in October 2009. A resident supervised by Dr. A (gynecologist) performed the surgery. Although the patient reported abdominal pain and was febrile, Dr. B (gynecologist) discharged her on postsurgical day 2.

The next day, she returned to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal swelling and pain. Dr. C (ED physician), Dr. D (gynecologist), and Dr. E (general surgeon) examined her. Dr. D began conservative treatment for bowel obstruction. Two days later she was in septic shock. Dr. E repaired a 5-mm injury to the sigmoid colon and created a colostomy. The patient was placed in a medically induced coma for 3 weeks. She experienced cardiac arrest 3 times during her 73-day ICU stay. She underwent skin grafts, and suffered hearing loss as a result of antibiotic treatment. Due to gangrene, both legs were amputated below the knee.

At the trial’s conclusion in January 2014, the colostomy had not been reversed. She has difficulty caring for her daughter and has not worked since the initial operation.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The resident, who injured the colon and did not detect the injury during surgery, was improperly supervised by Dr. A. Hospital staff did not communicate the patient’s problem reports to the physicians. Dr. B should not have discharged her after surgery; based on her reported symptoms, additional testing was warranted. Drs. C, D, and E did not react to the patient’s pain reports in a timely manner, nor treat the resulting sepsis aggressively enough, leading to gangrene.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The patient’s colon injury was diagnosed and treated in a timely manner, but her condition deteriorated rapidly. The physicians acted responsibly based on the available information; a computed tomography scan did not show the colon injury. The injury likely occurred after the procedure due to an underlying bowel condition and is a known risk of the procedure. The colostomy can be reversed. Their efforts saved her life.

VERDICT The patient and Dr. E negotiated a $2.3 million settlement. A $62 million New York verdict was returned. The jury found the hospital 40% liable; Dr. A 30% liable; Dr. B 20% liable; and Dr. D 10% liable. Claims were dropped against the resident and Dr. C.

Related article: Oophorectomy or salpingectomy—which makes more sense? William H. Parker, MD (March 2014)

PARENTS REQUESTED EARLIER CESAREAN: CHILD HAS CP

A woman was in labor for 2 full days before her ObGyn performed a cesarean delivery. The child was born with abnormal Apgar scores and had seizures. Imaging studies revealed brain damage. She received a diagnosis of cerebral palsy.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The parents first requested cesarean delivery early on the second day, but the ObGyn allowed labor to progress. When the fetal heart-rate monitor showed signs of fetal distress 3 hours later, the parents made a second request; the ObGyn continued with vaginal delivery. The child was ultimately born by cesarean delivery. Her brain damage was caused by lack of oxygen from failure to perform an earlier cesarean delivery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT A $4.25 million Massachusetts settlement was reached.

BLADDER INJURED DURING CESAREAN DELIVERY

A 33-year-old woman gave birth via cesarean delivery performed by her ObGyn. During the procedure, the patient’s bladder was lacerated and the injury was immediately repaired. The patient reports occasional urinary incontinence and pain.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn should have anticipated that the bladder would be shifted because of the patient’s previous cesarean delivery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The injury is a known risk of the procedure. The patient had developed adhesions that caused the bladder to become displaced. She does not suffer permanent residual effects from the injury.

VERDICT A $125,000 New York verdict was returned.

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for improving maternal outcomes of cesarean delivery. Baha M. Sibai (March 2012)

PARENTS REQUESTED SPECIFIC GENETIC TESTING, BUT CHILD IS BORN WITH RARE CHROMOSOMAL CONDITION: $50M VERDICT

Parents sought prenatal genetic testing to determine if their fetus had a specific genetic condition because the father carries a rare chromosomal abnormality called an unbalanced chromosome translocation. This defect can only be identified if the laboratory is told precisely where to look for the specific translocation; it is not detected on routine prenatal genetic testing. After testing, the parents were told that the fetus did not have the chromosomal abnormality.

The child was born with the condition for which testing was sought, resulting in severe physical and cognitive impairments and multiple physical abnormalities. He will require 24-hour care for life.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Testing failed to identify the condition; the couple had decided to terminate the pregnancy if the child was affected. Due to budget cuts in the maternal-fetal medicine clinic, the medical center borrowed a genetic counselor from another hospital one day a week. The parents told the genetic counselor of the family’s history of the defect and explained that the laboratory’s procedures require the referring center to obtain and share the necessary detailed information with the lab. The lab was apparently notified that the couple had a family history of the defect, but the genetic counselor did not transmit specific information to the lab, and lab personnel did not appropriately follow-up.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The medical center blamed the laboratory: the lab’s standard procedures state that the lab should call the referring center to obtain the necessary detailed information if it was not provided; the lab employee who handled the specimen did not do so. The lab claimed that the genetic counselor did not transmit the specific information to the lab.

The laboratory disputed the child’s need for 24/7 care, maintaining that he could live in a group home with only occasional nursing care.

VERDICT A $50 million Washington verdict was returned against the medical center and laboratory; each defendant will pay $25 million.

Related article: Noninvasive prenatal testing: Where we are and where we’re going. Lee P. Shulman, MD (Commentary; May 2014)

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS AFTER SURGERY

A 57-year-old woman underwent surgery to repair vaginal vault prolapse, rectocele, and enterocele, performed by her gynecologist. Several days after discharge, the patient returned to the hospital with an infection in her leg that had evolved into necrotizing fasciitis. She underwent five fasciotomies and was hospitalized for 3 weeks.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist should have administered prophylactic antibiotics before, during, and after surgery. The patient has massive scarring of her leg.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The infection was not a result of failing to administer antibiotics. The patient failed to seek timely treatment of symptoms that developed after surgery.

VERDICT A $400,000 New York verdict was returned but reduced because the jury found the patient 49% at fault.

OXYTOCIN BLAMED FOR CHILD’S CP

A mother had bariatric surgery 12 months before becoming pregnant, and she smoked during pregnancy. She developed placental insufficiency and labor was induced shortly after she reached 37 weeks’ gestation.