User login

Guidelines can predict infertility in child cancer survivors

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Guidelines developed almost 20 years ago can accurately predict infertility in girls with cancer, according to research published in The Lancet Oncology.

Researchers found the criteria in these guidelines can help healthcare professionals select which girls should be given the option of ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

The team noted that taking the initial samples of ovarian tissue involves a surgical technique that is still relatively experimental.

So it is crucial to accurately predict which patients are most likely to benefit from the procedure and when it can be safely performed.

The guidelines, known as the Edinburgh selection criteria, were instituted in 1996 to help healthcare professionals decide which girls should be given the option of cryopreservation, based on their age, type of cancer treatment, and their chance of cure.

Specifically, patients were required to meet the following criteria:

- Age younger than 35 years

- No previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy if 15 years or older at diagnosis, but mild, non-gonadotoxic chemotherapy was acceptable if a patient was younger than 15

- A realistic chance of surviving for 5 years

- A high risk of premature ovarian insufficiency (>50%)

- Informed consent (from parents and the patient, if possible)

- Negative serology results for HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B

- Not pregnant and no existing children.

Testing the guidelines

To validate the selection criteria, W. Hamish B. Wallace, MD, of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh, UK, and his colleagues analyzed 410 female cancer patients who were younger than 18 years at their time of diagnosis.

The patients were treated between January 1, 1996, and June 30, 2012, at the Edinburgh Children’s Cancer Centre, which serves the southeast region of Scotland.

In all, 34 patients (8%) met the Edinburgh selection criteria and were given the option of ovarian tissue cryopreservation before starting cancer treatment. Thirteen patients declined, 21 consented, and 20 had a successful procedure.

The researchers were able to assess ovarian function in 14 of the 20 patients with successful cryopreservation and 6 of the 13 patients who declined the procedure.

Of the 14 evaluable patients who underwent cryopreservation, 6 developed premature ovarian insufficiency at a median age of 13.4 years (range, 12.5–14.6), but 1 of these patients also had a natural pregnancy.

One patient each among the 6 evaluable patients who declined cryopreservation and the 141 evaluable patients who were not offered cryopreservation developed premature ovarian insufficiency.

So, overall, the probability of ovarian insufficiency was significantly higher for patients who met the Edinburgh selection criteria than for those who did not. The 15-year probability was 35% and 1%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The researchers said these results validate the use of the selection criteria, as they can accurately identify patients who will likely develop premature ovarian insufficiency.

“Advances in life-saving treatments mean that more and more young people with cancer are surviving the disease,” Dr Wallace said. “Here, we have an opportunity to help young women to have families of their own when they grow up, if they so choose.” ![]()

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Guidelines developed almost 20 years ago can accurately predict infertility in girls with cancer, according to research published in The Lancet Oncology.

Researchers found the criteria in these guidelines can help healthcare professionals select which girls should be given the option of ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

The team noted that taking the initial samples of ovarian tissue involves a surgical technique that is still relatively experimental.

So it is crucial to accurately predict which patients are most likely to benefit from the procedure and when it can be safely performed.

The guidelines, known as the Edinburgh selection criteria, were instituted in 1996 to help healthcare professionals decide which girls should be given the option of cryopreservation, based on their age, type of cancer treatment, and their chance of cure.

Specifically, patients were required to meet the following criteria:

- Age younger than 35 years

- No previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy if 15 years or older at diagnosis, but mild, non-gonadotoxic chemotherapy was acceptable if a patient was younger than 15

- A realistic chance of surviving for 5 years

- A high risk of premature ovarian insufficiency (>50%)

- Informed consent (from parents and the patient, if possible)

- Negative serology results for HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B

- Not pregnant and no existing children.

Testing the guidelines

To validate the selection criteria, W. Hamish B. Wallace, MD, of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh, UK, and his colleagues analyzed 410 female cancer patients who were younger than 18 years at their time of diagnosis.

The patients were treated between January 1, 1996, and June 30, 2012, at the Edinburgh Children’s Cancer Centre, which serves the southeast region of Scotland.

In all, 34 patients (8%) met the Edinburgh selection criteria and were given the option of ovarian tissue cryopreservation before starting cancer treatment. Thirteen patients declined, 21 consented, and 20 had a successful procedure.

The researchers were able to assess ovarian function in 14 of the 20 patients with successful cryopreservation and 6 of the 13 patients who declined the procedure.

Of the 14 evaluable patients who underwent cryopreservation, 6 developed premature ovarian insufficiency at a median age of 13.4 years (range, 12.5–14.6), but 1 of these patients also had a natural pregnancy.

One patient each among the 6 evaluable patients who declined cryopreservation and the 141 evaluable patients who were not offered cryopreservation developed premature ovarian insufficiency.

So, overall, the probability of ovarian insufficiency was significantly higher for patients who met the Edinburgh selection criteria than for those who did not. The 15-year probability was 35% and 1%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The researchers said these results validate the use of the selection criteria, as they can accurately identify patients who will likely develop premature ovarian insufficiency.

“Advances in life-saving treatments mean that more and more young people with cancer are surviving the disease,” Dr Wallace said. “Here, we have an opportunity to help young women to have families of their own when they grow up, if they so choose.” ![]()

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Guidelines developed almost 20 years ago can accurately predict infertility in girls with cancer, according to research published in The Lancet Oncology.

Researchers found the criteria in these guidelines can help healthcare professionals select which girls should be given the option of ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

The team noted that taking the initial samples of ovarian tissue involves a surgical technique that is still relatively experimental.

So it is crucial to accurately predict which patients are most likely to benefit from the procedure and when it can be safely performed.

The guidelines, known as the Edinburgh selection criteria, were instituted in 1996 to help healthcare professionals decide which girls should be given the option of cryopreservation, based on their age, type of cancer treatment, and their chance of cure.

Specifically, patients were required to meet the following criteria:

- Age younger than 35 years

- No previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy if 15 years or older at diagnosis, but mild, non-gonadotoxic chemotherapy was acceptable if a patient was younger than 15

- A realistic chance of surviving for 5 years

- A high risk of premature ovarian insufficiency (>50%)

- Informed consent (from parents and the patient, if possible)

- Negative serology results for HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B

- Not pregnant and no existing children.

Testing the guidelines

To validate the selection criteria, W. Hamish B. Wallace, MD, of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh, UK, and his colleagues analyzed 410 female cancer patients who were younger than 18 years at their time of diagnosis.

The patients were treated between January 1, 1996, and June 30, 2012, at the Edinburgh Children’s Cancer Centre, which serves the southeast region of Scotland.

In all, 34 patients (8%) met the Edinburgh selection criteria and were given the option of ovarian tissue cryopreservation before starting cancer treatment. Thirteen patients declined, 21 consented, and 20 had a successful procedure.

The researchers were able to assess ovarian function in 14 of the 20 patients with successful cryopreservation and 6 of the 13 patients who declined the procedure.

Of the 14 evaluable patients who underwent cryopreservation, 6 developed premature ovarian insufficiency at a median age of 13.4 years (range, 12.5–14.6), but 1 of these patients also had a natural pregnancy.

One patient each among the 6 evaluable patients who declined cryopreservation and the 141 evaluable patients who were not offered cryopreservation developed premature ovarian insufficiency.

So, overall, the probability of ovarian insufficiency was significantly higher for patients who met the Edinburgh selection criteria than for those who did not. The 15-year probability was 35% and 1%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The researchers said these results validate the use of the selection criteria, as they can accurately identify patients who will likely develop premature ovarian insufficiency.

“Advances in life-saving treatments mean that more and more young people with cancer are surviving the disease,” Dr Wallace said. “Here, we have an opportunity to help young women to have families of their own when they grow up, if they so choose.” ![]()

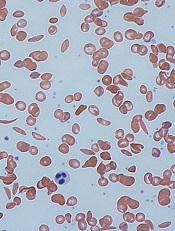

Team explains resistance to retinoic acid

Credit: Armin Kübelbeck

Preclinical experiments may have revealed why some cancer patients do not respond to retinoic acid.

Investigators found that a protein known as AEG-1 blocks the effects of retinoic acid in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and liver cancer.

They also noted that AEG-1 is overexpressed in nearly every cancer type, so these findings could impact the care of countless cancer patients.

The team reported their findings in Cancer Research.

The group’s experiments revealed that AEG-1 binds to retinoid X receptors (RXR), which help regulate cell growth and development. RXR is typically activated by retinoic acid, but the overexpressed AEG-1 proteins found in cancer cells block these signals and help promote tumor growth.

“Our findings are the first to show that AEG-1 interacts with the retinoid X receptor,” said study author Devanand Sarkar, MBBS, PhD, of Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center in Richmond.

Specifically, he and his colleagues found that AEG-1 protected hepatocellular carcinoma cells and AML cells from retinoid- and rexinoid-induced cell death.

But in nude mouse models, blocking the production of AEG-1 allowed all-trans retinoic acid to kill hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

The investigators therefore believe that targeting AEG-1 could sensitize AML patients and those with hepatocellular carcinoma to retinoid- and rexinoid-based therapies.

“This research has immediate clinical relevance, such that physicians could begin screening cancer patients for AEG-1 expression levels in order to determine whether retinoic acid should be prescribed,” Dr Sarkar added.

He and his colleagues have been studying AEG-1 for years. They were the first to create a mouse model demonstrating the role of AEG-1 in liver cancer, and they have been working to develop targeted therapies that block AEG-1 production.

The present study expanded their knowledge of the molecular interactions of AEG-1.

“We are continuing to test combination therapies involving AEG-1 inhibition and retinoic acid in animal models, and the initial results are promising,” Dr Sarkar said. “If we continue to see these results in more complex experiments, we hope to eventually propose a phase 1 clinical trial in patients with liver cancer.” ![]()

Credit: Armin Kübelbeck

Preclinical experiments may have revealed why some cancer patients do not respond to retinoic acid.

Investigators found that a protein known as AEG-1 blocks the effects of retinoic acid in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and liver cancer.

They also noted that AEG-1 is overexpressed in nearly every cancer type, so these findings could impact the care of countless cancer patients.

The team reported their findings in Cancer Research.

The group’s experiments revealed that AEG-1 binds to retinoid X receptors (RXR), which help regulate cell growth and development. RXR is typically activated by retinoic acid, but the overexpressed AEG-1 proteins found in cancer cells block these signals and help promote tumor growth.

“Our findings are the first to show that AEG-1 interacts with the retinoid X receptor,” said study author Devanand Sarkar, MBBS, PhD, of Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center in Richmond.

Specifically, he and his colleagues found that AEG-1 protected hepatocellular carcinoma cells and AML cells from retinoid- and rexinoid-induced cell death.

But in nude mouse models, blocking the production of AEG-1 allowed all-trans retinoic acid to kill hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

The investigators therefore believe that targeting AEG-1 could sensitize AML patients and those with hepatocellular carcinoma to retinoid- and rexinoid-based therapies.

“This research has immediate clinical relevance, such that physicians could begin screening cancer patients for AEG-1 expression levels in order to determine whether retinoic acid should be prescribed,” Dr Sarkar added.

He and his colleagues have been studying AEG-1 for years. They were the first to create a mouse model demonstrating the role of AEG-1 in liver cancer, and they have been working to develop targeted therapies that block AEG-1 production.

The present study expanded their knowledge of the molecular interactions of AEG-1.

“We are continuing to test combination therapies involving AEG-1 inhibition and retinoic acid in animal models, and the initial results are promising,” Dr Sarkar said. “If we continue to see these results in more complex experiments, we hope to eventually propose a phase 1 clinical trial in patients with liver cancer.” ![]()

Credit: Armin Kübelbeck

Preclinical experiments may have revealed why some cancer patients do not respond to retinoic acid.

Investigators found that a protein known as AEG-1 blocks the effects of retinoic acid in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and liver cancer.

They also noted that AEG-1 is overexpressed in nearly every cancer type, so these findings could impact the care of countless cancer patients.

The team reported their findings in Cancer Research.

The group’s experiments revealed that AEG-1 binds to retinoid X receptors (RXR), which help regulate cell growth and development. RXR is typically activated by retinoic acid, but the overexpressed AEG-1 proteins found in cancer cells block these signals and help promote tumor growth.

“Our findings are the first to show that AEG-1 interacts with the retinoid X receptor,” said study author Devanand Sarkar, MBBS, PhD, of Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center in Richmond.

Specifically, he and his colleagues found that AEG-1 protected hepatocellular carcinoma cells and AML cells from retinoid- and rexinoid-induced cell death.

But in nude mouse models, blocking the production of AEG-1 allowed all-trans retinoic acid to kill hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

The investigators therefore believe that targeting AEG-1 could sensitize AML patients and those with hepatocellular carcinoma to retinoid- and rexinoid-based therapies.

“This research has immediate clinical relevance, such that physicians could begin screening cancer patients for AEG-1 expression levels in order to determine whether retinoic acid should be prescribed,” Dr Sarkar added.

He and his colleagues have been studying AEG-1 for years. They were the first to create a mouse model demonstrating the role of AEG-1 in liver cancer, and they have been working to develop targeted therapies that block AEG-1 production.

The present study expanded their knowledge of the molecular interactions of AEG-1.

“We are continuing to test combination therapies involving AEG-1 inhibition and retinoic acid in animal models, and the initial results are promising,” Dr Sarkar said. “If we continue to see these results in more complex experiments, we hope to eventually propose a phase 1 clinical trial in patients with liver cancer.” ![]()

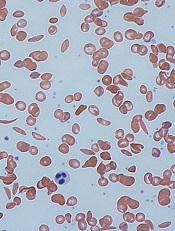

Discovery could help halt malaria transmission

Credit: Swiss TPH

Malaria parasites exploit the epigenetic regulator HP1 to promote their survival and transmission between human hosts, a new study suggests.

It appears that Plasmodium falciparum uses HP1 to control the expression of surface antigens and escape the body’s immune responses. This prolongs the parasite’s survival and enables its transmission.

Researchers believe this discovery paves the way for new strategies to prevent malaria transmission.

Till Voss, PhD, of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel, and his colleagues detailed the discovery in Cell Host & Microbe.

The team knew that HP1 induces heritable condensation of chromosomal regions. As a result, genes located within these regions are not expressed.

Since this conformation is reversible, HP1-controlled genes can become activated without requiring changes in the underlying DNA sequence.

With this in mind, the researchers engineered a mutant P falciparum parasite in which HP1 expression can be shut down. And the team observed that, in HP1-depleted parasites, all of the 60 var genes became highly active.

Each var gene encodes a distinct variant of the virulence factor PfEMP1, which is displayed on the surface of the parasite-infected red blood cell. PfEMP1 is a major target of the immune system in infected humans.

Individual parasites normally express only 1 of the 60 var/PfEMP1 proteins, while keeping all other members silenced. By switching to another var/PfEMP1 variant, the parasite is able to escape existing immune responses raised against previous variants.

Dr Voss and his colleagues found that HP1 protects the PfEMP1 antigenic repertoire from being exposed to the immune system all at once.

“This finding is a major step forward in understanding the complex mechanisms responsible for antigenic variation,” Dr Voss said. “Furthermore, the tools generated in our study may be relevant for future research on malaria vaccines and immunity.”

The researchers also found that parasites lacking HP1 fail to copy their genomes and are therefore unable to proliferate. Initially, this led the team to believe that all the parasites they had cultured were dead.

However, more than 50% of these parasites turned out to be fully viable and differentiated into gametocytes, the sexual form of the malaria parasite. Gametocytes are the only form of the parasite capable of infecting a mosquito and are a prerequisite to transmit malaria between humans.

“Such a high sexual conversion rate is unprecedented,” Dr Voss said. “Usually, only around 1% of parasites undergo this switch.”

Further experiments revealed that a master transcription factor triggering sexual differentiation—AP2-G—is expressed at much higher levels in parasites lacking HP1. Under normal conditions, HP1 silences the expression of AP2-G and therefore prevents sexual conversion in most parasites.

“The switch from parasite proliferation to gametocyte differentiation is controlled epigenetically by an HP1-dependent mechanism,” Dr Voss said.

“With this knowledge in hand, and with the identification of another epigenetic regulator involved in the same process [also published in Cell Host & Microbe], we are now able to specifically track the sexual conversion pathway in molecular detail.”

This may enable the development of new drugs to prevent sexual conversion and, consequently, malaria transmission. ![]()

Credit: Swiss TPH

Malaria parasites exploit the epigenetic regulator HP1 to promote their survival and transmission between human hosts, a new study suggests.

It appears that Plasmodium falciparum uses HP1 to control the expression of surface antigens and escape the body’s immune responses. This prolongs the parasite’s survival and enables its transmission.

Researchers believe this discovery paves the way for new strategies to prevent malaria transmission.

Till Voss, PhD, of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel, and his colleagues detailed the discovery in Cell Host & Microbe.

The team knew that HP1 induces heritable condensation of chromosomal regions. As a result, genes located within these regions are not expressed.

Since this conformation is reversible, HP1-controlled genes can become activated without requiring changes in the underlying DNA sequence.

With this in mind, the researchers engineered a mutant P falciparum parasite in which HP1 expression can be shut down. And the team observed that, in HP1-depleted parasites, all of the 60 var genes became highly active.

Each var gene encodes a distinct variant of the virulence factor PfEMP1, which is displayed on the surface of the parasite-infected red blood cell. PfEMP1 is a major target of the immune system in infected humans.

Individual parasites normally express only 1 of the 60 var/PfEMP1 proteins, while keeping all other members silenced. By switching to another var/PfEMP1 variant, the parasite is able to escape existing immune responses raised against previous variants.

Dr Voss and his colleagues found that HP1 protects the PfEMP1 antigenic repertoire from being exposed to the immune system all at once.

“This finding is a major step forward in understanding the complex mechanisms responsible for antigenic variation,” Dr Voss said. “Furthermore, the tools generated in our study may be relevant for future research on malaria vaccines and immunity.”

The researchers also found that parasites lacking HP1 fail to copy their genomes and are therefore unable to proliferate. Initially, this led the team to believe that all the parasites they had cultured were dead.

However, more than 50% of these parasites turned out to be fully viable and differentiated into gametocytes, the sexual form of the malaria parasite. Gametocytes are the only form of the parasite capable of infecting a mosquito and are a prerequisite to transmit malaria between humans.

“Such a high sexual conversion rate is unprecedented,” Dr Voss said. “Usually, only around 1% of parasites undergo this switch.”

Further experiments revealed that a master transcription factor triggering sexual differentiation—AP2-G—is expressed at much higher levels in parasites lacking HP1. Under normal conditions, HP1 silences the expression of AP2-G and therefore prevents sexual conversion in most parasites.

“The switch from parasite proliferation to gametocyte differentiation is controlled epigenetically by an HP1-dependent mechanism,” Dr Voss said.

“With this knowledge in hand, and with the identification of another epigenetic regulator involved in the same process [also published in Cell Host & Microbe], we are now able to specifically track the sexual conversion pathway in molecular detail.”

This may enable the development of new drugs to prevent sexual conversion and, consequently, malaria transmission. ![]()

Credit: Swiss TPH

Malaria parasites exploit the epigenetic regulator HP1 to promote their survival and transmission between human hosts, a new study suggests.

It appears that Plasmodium falciparum uses HP1 to control the expression of surface antigens and escape the body’s immune responses. This prolongs the parasite’s survival and enables its transmission.

Researchers believe this discovery paves the way for new strategies to prevent malaria transmission.

Till Voss, PhD, of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel, and his colleagues detailed the discovery in Cell Host & Microbe.

The team knew that HP1 induces heritable condensation of chromosomal regions. As a result, genes located within these regions are not expressed.

Since this conformation is reversible, HP1-controlled genes can become activated without requiring changes in the underlying DNA sequence.

With this in mind, the researchers engineered a mutant P falciparum parasite in which HP1 expression can be shut down. And the team observed that, in HP1-depleted parasites, all of the 60 var genes became highly active.

Each var gene encodes a distinct variant of the virulence factor PfEMP1, which is displayed on the surface of the parasite-infected red blood cell. PfEMP1 is a major target of the immune system in infected humans.

Individual parasites normally express only 1 of the 60 var/PfEMP1 proteins, while keeping all other members silenced. By switching to another var/PfEMP1 variant, the parasite is able to escape existing immune responses raised against previous variants.

Dr Voss and his colleagues found that HP1 protects the PfEMP1 antigenic repertoire from being exposed to the immune system all at once.

“This finding is a major step forward in understanding the complex mechanisms responsible for antigenic variation,” Dr Voss said. “Furthermore, the tools generated in our study may be relevant for future research on malaria vaccines and immunity.”

The researchers also found that parasites lacking HP1 fail to copy their genomes and are therefore unable to proliferate. Initially, this led the team to believe that all the parasites they had cultured were dead.

However, more than 50% of these parasites turned out to be fully viable and differentiated into gametocytes, the sexual form of the malaria parasite. Gametocytes are the only form of the parasite capable of infecting a mosquito and are a prerequisite to transmit malaria between humans.

“Such a high sexual conversion rate is unprecedented,” Dr Voss said. “Usually, only around 1% of parasites undergo this switch.”

Further experiments revealed that a master transcription factor triggering sexual differentiation—AP2-G—is expressed at much higher levels in parasites lacking HP1. Under normal conditions, HP1 silences the expression of AP2-G and therefore prevents sexual conversion in most parasites.

“The switch from parasite proliferation to gametocyte differentiation is controlled epigenetically by an HP1-dependent mechanism,” Dr Voss said.

“With this knowledge in hand, and with the identification of another epigenetic regulator involved in the same process [also published in Cell Host & Microbe], we are now able to specifically track the sexual conversion pathway in molecular detail.”

This may enable the development of new drugs to prevent sexual conversion and, consequently, malaria transmission. ![]()

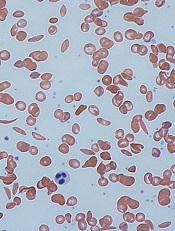

Protein appears essential for NK cell survival

Credit: Walter and Eliza Hall

Institute of Medical Research

New research suggests the Mcl-1 protein is crucial for the survival of natural killer (NK) cells and, therefore, innate immune responses.

Researchers deleted Mcl-1 from NK cells in mice and observed a loss of the cells from all tissues.

This made the mice more receptive to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants and resistant to toxic shock following a sepsis challenge, but it also made the mice susceptible to melanoma metastases.

The researchers believe their findings, published in Nature Communications, will help to determine how NK cells can be manipulated to treat a range of disorders.

They said Mcl-1 could be a target for boosting or depleting NK cell populations when necessary.

The researchers first discovered that Mcl-1 is highly expressed in NK cells. And Mcl-1 is regulated by IL-15 in a dose-dependent manner via STAT5 phosphorylation and subsequent binding to the 3′-UTR of Mcl-1.

“We showed Mcl-1 levels inside the cell increase in response to [IL-15],” said study author Nick Huntington, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Victoria, Australia.

“We previously knew IL-15 boosted production and survival of natural killer cells, and we have shown that IL-15 does this by initiating a cascade of signals that tell the natural killer cell to produce Mcl-1 to keep it alive.”

To further explore this phenomenon, the researchers deleted Mcl-1 from NK cells in mice and observed depletion of the cells in all tissues. The team said this was the result of a failure to antagonize pro-apoptotic proteins in the outer mitochondrial membrane.

Additional experiments showed that the mice needed the NK cells to fight off invading melanoma cells that had spread past the original cancer site.

“Without natural killer cells, the body was unable to destroy melanoma metastases that had spread throughout the body, and the cancers overwhelmed the lungs,” Dr Huntington said.

However, the loss of NK cells also made mice more receptive to allogeneic stem cell transplants and resistant to toxic shock after polymicrobial sepsis challenge.

“Natural killer cells led the response that caused rejection of donor stem cells in bone marrow transplantations,” Dr Huntington said. “They also produced inflammatory signals that can result in toxic shock syndrome, a potentially fatal illness caused by bacterial toxins that causes a whole-body inflammatory reaction.”

The researchers said these results clearly show a non-redundant pathway linking IL-15 to Mcl-1 in the maintenance of NK cells and innate immune responses.

Dr Huntington said the discovery provides a solid lead to look for ways of boosting or depleting NK cells when necessary.

“Now that we know the critical importance of Mcl-1 in the survival of natural killer cells,” he said, “we are investigating how we might manipulate this protein, or other proteins in the pathway, to treat disease.” ![]()

Credit: Walter and Eliza Hall

Institute of Medical Research

New research suggests the Mcl-1 protein is crucial for the survival of natural killer (NK) cells and, therefore, innate immune responses.

Researchers deleted Mcl-1 from NK cells in mice and observed a loss of the cells from all tissues.

This made the mice more receptive to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants and resistant to toxic shock following a sepsis challenge, but it also made the mice susceptible to melanoma metastases.

The researchers believe their findings, published in Nature Communications, will help to determine how NK cells can be manipulated to treat a range of disorders.

They said Mcl-1 could be a target for boosting or depleting NK cell populations when necessary.

The researchers first discovered that Mcl-1 is highly expressed in NK cells. And Mcl-1 is regulated by IL-15 in a dose-dependent manner via STAT5 phosphorylation and subsequent binding to the 3′-UTR of Mcl-1.

“We showed Mcl-1 levels inside the cell increase in response to [IL-15],” said study author Nick Huntington, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Victoria, Australia.

“We previously knew IL-15 boosted production and survival of natural killer cells, and we have shown that IL-15 does this by initiating a cascade of signals that tell the natural killer cell to produce Mcl-1 to keep it alive.”

To further explore this phenomenon, the researchers deleted Mcl-1 from NK cells in mice and observed depletion of the cells in all tissues. The team said this was the result of a failure to antagonize pro-apoptotic proteins in the outer mitochondrial membrane.

Additional experiments showed that the mice needed the NK cells to fight off invading melanoma cells that had spread past the original cancer site.

“Without natural killer cells, the body was unable to destroy melanoma metastases that had spread throughout the body, and the cancers overwhelmed the lungs,” Dr Huntington said.

However, the loss of NK cells also made mice more receptive to allogeneic stem cell transplants and resistant to toxic shock after polymicrobial sepsis challenge.

“Natural killer cells led the response that caused rejection of donor stem cells in bone marrow transplantations,” Dr Huntington said. “They also produced inflammatory signals that can result in toxic shock syndrome, a potentially fatal illness caused by bacterial toxins that causes a whole-body inflammatory reaction.”

The researchers said these results clearly show a non-redundant pathway linking IL-15 to Mcl-1 in the maintenance of NK cells and innate immune responses.

Dr Huntington said the discovery provides a solid lead to look for ways of boosting or depleting NK cells when necessary.

“Now that we know the critical importance of Mcl-1 in the survival of natural killer cells,” he said, “we are investigating how we might manipulate this protein, or other proteins in the pathway, to treat disease.” ![]()

Credit: Walter and Eliza Hall

Institute of Medical Research

New research suggests the Mcl-1 protein is crucial for the survival of natural killer (NK) cells and, therefore, innate immune responses.

Researchers deleted Mcl-1 from NK cells in mice and observed a loss of the cells from all tissues.

This made the mice more receptive to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants and resistant to toxic shock following a sepsis challenge, but it also made the mice susceptible to melanoma metastases.

The researchers believe their findings, published in Nature Communications, will help to determine how NK cells can be manipulated to treat a range of disorders.

They said Mcl-1 could be a target for boosting or depleting NK cell populations when necessary.

The researchers first discovered that Mcl-1 is highly expressed in NK cells. And Mcl-1 is regulated by IL-15 in a dose-dependent manner via STAT5 phosphorylation and subsequent binding to the 3′-UTR of Mcl-1.

“We showed Mcl-1 levels inside the cell increase in response to [IL-15],” said study author Nick Huntington, PhD, of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Victoria, Australia.

“We previously knew IL-15 boosted production and survival of natural killer cells, and we have shown that IL-15 does this by initiating a cascade of signals that tell the natural killer cell to produce Mcl-1 to keep it alive.”

To further explore this phenomenon, the researchers deleted Mcl-1 from NK cells in mice and observed depletion of the cells in all tissues. The team said this was the result of a failure to antagonize pro-apoptotic proteins in the outer mitochondrial membrane.

Additional experiments showed that the mice needed the NK cells to fight off invading melanoma cells that had spread past the original cancer site.

“Without natural killer cells, the body was unable to destroy melanoma metastases that had spread throughout the body, and the cancers overwhelmed the lungs,” Dr Huntington said.

However, the loss of NK cells also made mice more receptive to allogeneic stem cell transplants and resistant to toxic shock after polymicrobial sepsis challenge.

“Natural killer cells led the response that caused rejection of donor stem cells in bone marrow transplantations,” Dr Huntington said. “They also produced inflammatory signals that can result in toxic shock syndrome, a potentially fatal illness caused by bacterial toxins that causes a whole-body inflammatory reaction.”

The researchers said these results clearly show a non-redundant pathway linking IL-15 to Mcl-1 in the maintenance of NK cells and innate immune responses.

Dr Huntington said the discovery provides a solid lead to look for ways of boosting or depleting NK cells when necessary.

“Now that we know the critical importance of Mcl-1 in the survival of natural killer cells,” he said, “we are investigating how we might manipulate this protein, or other proteins in the pathway, to treat disease.” ![]()

Evidence-based guideline update: vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology

In Children with Epilepsy, Is Using Adjunctive Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) Therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction Better Than Not Using Adjunctive VNS therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction?

Conclusion

Based on data from 14 Class III studies, VNS is possibly effective in achieving >50% seizure frequency reduction (responder rate). In the pooled analysis of 481 children, the responder rate was 55% (95% confidence interval [CI] 51%–59%), but there was significant heterogeneity in the data. Two of the 16 studies were not included in the analysis because either they did not provide information about responder rate or they included a significant number (>20%) of adults in their population. The pooled seizure freedom rate was 7% (95% CI 5%–10%).

Recommendation

VNS may be considered as adjunctive treatment for children with partial or generalized epilepsy (Level C).

Clinical Context

VNS may be considered a possibly effective option after a child with medication-resistant epilepsy has been declared a poor surgical candidate or has had unsuccessful surgery.

In Patients with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (LGS), Is Using Adjunctive VNS Therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction Better Than Not Using Adjunctive VNS Therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction?

Conclusion

Based on data from 4 Class III studies, VNS is possibly effective in achieving >50% seizure frequency reduction in patients with LGS. The pooled analysis of 113 patients with LGS (including data from articles with multiple seizure types where LGS data were parsed out) yielded a 55% (95% CI 46%–64%) responder rate.

Recommendation

VNS may be considered in patients with LGS (Level C).

Clinical Context

The responder rate for patients with LGS does not appear to differ from that of the general population of patients with medication-resistant epilepsy.

In Patients with Epilepsy, Is Using VNS Associated with Mood Improvement?

Conclusion

Based on data from 2 Class III studies, VNS is possibly effective for mood improvement in adults with epilepsy.

Recommendation

In adult patients receiving VNS for epilepsy, improvement in mood may be an additional benefit (Level C).

Clinical Context

Depression is a common comorbidity for people with epilepsy. VNS may provide an additional benefit by improving mood in some patients; however, the potential for mood improvement should be considered a secondary rather than a primary reason for VNS implantation. The evidence does not clearly support an independent effect on mood in this complex population.

In Patients with Epilepsy, Is VNS Use Associated with Reduced Seizure Frequency Over Time?

Conclusion

Based on data from 2 Class III studies, VNS is possibly associated with an increase in ≥50% seizure frequency reduction rates of 7% from 1 to 5 years postimplantation.

Recommendation

VNS may be considered progressively effective in patients over multiple years of exposure (Level C).

Clinical Context

The loss of medication efficacy over time is a challenging aspect of epilepsy management. The evidence of maintained efficacy in the long term and the trend toward improvement over time make VNS an option.

In Patients Undergoing VNS Therapy, Does Rapid Stimulation (Usual VNS Settings Are 7 Seconds "On" and 30 Seconds "Off") Improve Seizure Frequency More Often Than Standard Stimulation Settings (30 Seconds "On" and 300 Seconds "Off")?

Conclusion

These 3 Class III studies were underpowered to detect a difference in efficacy between rapid stimulation (7 seconds "on," 30 seconds "off") used either after standard stimulation (30 seconds "on," 300 seconds "off") was unsuccessful or as an initial treatment setting.

Recommendation

Optimal VNS settings are still unknown, and the evidence is insufficient to support a recommendation for the use of standard stimulation vs. rapid stimulation to reduce seizure occurrence (Level U).

Clinical Context

Rapid cycling increases the duty cycle and hastens the need for battery replacement; therefore, when used, the efficacy of rapid cycling should be carefully assessed.

In Patients Undergoing VNS Therapy, Does Using Additional Magnet-Activated Stimulation Trains for Auras or at Seizure Onset Interrupt Seizures Relative to Not Using Additional Magnet-Induced Stimulation Trains for Auras or at Seizure Onset?

Conclusion

Based on data from 2 Class III studies, seizure abortion with magnet-activated stimulation is possibly associated with overall response to VNS therapy. Based on 3 Class III studies, magnet-activated stimulation may be expected to abort seizures one-fourth to two-thirds of the time when used during seizure auras (one Class III study omitted because it was not generalizable).

Recommendation

Patients may be counseled that VNS magnet activation may be associated with seizure abortion when used at the time of seizure auras (Level C) and that seizure abortion with magnet use may be associated with overall response to VNS treatment (Level C).

In Patients Undergoing VNS Therapy, Have New Safety Concerns Emerged Since the Last Assessment?

Clinical Context

Current physician attention to intraoperative rhythm disturbances from VNS use need not be changed. The paroxysmal nature of epilepsy poses a challenge for identifying a cardiac rhythm disturbance as device-related rather than as an additional seizure manifestation. Video electroencephalogram (EEG) and electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring of new-onset events that might be cardiac-related would be warranted to exclude this possibility in what is likely to be a small number of patients. Reduced sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) rates over time is an important finding associated with VNS therapy; in a cohort of 1,819 individuals followed 3,176.3 person-years from VNS implantation, the SUDEP rate was 5.5 per 1,000 over the first 2 years but only 1.7 per 1,000 thereafter. The clinical importance of the effect of VNS on sleep apnea and treatment is unclear, but caution regarding VNS use in this setting is suggested.

In Children Undergoing VNS Therapy, Do Adverse Events (AEs) Differ from Those in Adults?

Clinical Context

Children may have greater risk for wound infection than adults due to behaviors more common in children. Extra vigilance in monitoring for occurrence of site infection in children should be undertaken.

Definitions:

Classification of Evidence for Therapeutic Intervention

Class I: A randomized, controlled clinical trial of the intervention of interest with masked or objective outcome assessment, in a representative population. Relevant baseline characteristics are presented and substantially equivalent among treatment groups or there is appropriate statistical adjustment for differences.

The following are also required:

- Concealed allocation

- Primary outcome(s) clearly defined

- Exclusion/inclusion criteria clearly defined

- Adequate accounting for dropouts (with at least 80% of enrolled subjects completing the study) and crossovers with numbers sufficiently low to have minimal potential for bias.

- For noninferiority or equivalence trials claiming to prove efficacy for one or both drugs, the following are also required*

- The authors explicitly state the clinically meaningful difference to be excluded by defining the threshold for equivalence or noninferiority.

- The standard treatment used in the study is substantially similar to that used in previous studies establishing efficacy of the standard treatment (e.g., for a drug, the mode of administration, dose and dosage adjustments are similar to those previously shown to be effective).

- The inclusion and exclusion criteria for patient selection and the outcomes of patients on the standard treatment are comparable to those of previous studies establishing efficacy of the standard treatment.

- The interpretation of the results of the study is based upon a per protocol analysis that takes into account dropouts or crossovers.

Class II: A randomized controlled clinical trial of the intervention of interest in a representative population with masked or objective outcome assessment that lacks one criteria a–e above or a prospective matched cohort study with masked or objective outcome assessment in a representative population that meets b–e above. Relevant baseline characteristics are presented and substantially equivalent among treatment groups or there is appropriate statistical adjustment for differences.

Class III: All other controlled trials (including well-defined natural history controls or patients serving as own controls) in a representative population, where outcome is independently assessed, or independently derived by objective outcome measurement.**

Class IV: Studies not meeting Class I, II, or III criteria including consensus or expert opinion.

*Note that numbers 1-3 in Class Ie are required for Class II in equivalence trials. If any one of the three is missing, the class is automatically downgraded to Class III.

**Objective outcome measurement: an outcome measure that is unlikely to be affected by an observer's (patient, treating physician, investigator) expectation or bias (e.g., blood tests, administrative outcome data).

Classification of Recommendations

Level A = Established as effective, ineffective or harmful (or established as useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. (Level A rating requires at least two consistent Class I studies.*)

Level B = Probably effective, ineffective or harmful (or probably useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. (Level B rating requires at least one Class I study or two consistent Class II studies.)

Level C = Possibly effective, ineffective or harmful (or possibly useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. (Level C rating requires at least one Class II study or two consistent Class III studies.)

Level U = Data inadequate or conflicting; given current knowledge, treatment (test, predictor) is unproven.

*In exceptional cases, one convincing Class I study may suffice for an "A" recommendation if 1) all criteria are met, 2) the magnitude of effect is large (relative rate improved outcome >5 and the lower limit of the confidence interval is >2).

In Children with Epilepsy, Is Using Adjunctive Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) Therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction Better Than Not Using Adjunctive VNS therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction?

Conclusion

Based on data from 14 Class III studies, VNS is possibly effective in achieving >50% seizure frequency reduction (responder rate). In the pooled analysis of 481 children, the responder rate was 55% (95% confidence interval [CI] 51%–59%), but there was significant heterogeneity in the data. Two of the 16 studies were not included in the analysis because either they did not provide information about responder rate or they included a significant number (>20%) of adults in their population. The pooled seizure freedom rate was 7% (95% CI 5%–10%).

Recommendation

VNS may be considered as adjunctive treatment for children with partial or generalized epilepsy (Level C).

Clinical Context

VNS may be considered a possibly effective option after a child with medication-resistant epilepsy has been declared a poor surgical candidate or has had unsuccessful surgery.

In Patients with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (LGS), Is Using Adjunctive VNS Therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction Better Than Not Using Adjunctive VNS Therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction?

Conclusion

Based on data from 4 Class III studies, VNS is possibly effective in achieving >50% seizure frequency reduction in patients with LGS. The pooled analysis of 113 patients with LGS (including data from articles with multiple seizure types where LGS data were parsed out) yielded a 55% (95% CI 46%–64%) responder rate.

Recommendation

VNS may be considered in patients with LGS (Level C).

Clinical Context

The responder rate for patients with LGS does not appear to differ from that of the general population of patients with medication-resistant epilepsy.

In Patients with Epilepsy, Is Using VNS Associated with Mood Improvement?

Conclusion

Based on data from 2 Class III studies, VNS is possibly effective for mood improvement in adults with epilepsy.

Recommendation

In adult patients receiving VNS for epilepsy, improvement in mood may be an additional benefit (Level C).

Clinical Context

Depression is a common comorbidity for people with epilepsy. VNS may provide an additional benefit by improving mood in some patients; however, the potential for mood improvement should be considered a secondary rather than a primary reason for VNS implantation. The evidence does not clearly support an independent effect on mood in this complex population.

In Patients with Epilepsy, Is VNS Use Associated with Reduced Seizure Frequency Over Time?

Conclusion

Based on data from 2 Class III studies, VNS is possibly associated with an increase in ≥50% seizure frequency reduction rates of 7% from 1 to 5 years postimplantation.

Recommendation

VNS may be considered progressively effective in patients over multiple years of exposure (Level C).

Clinical Context

The loss of medication efficacy over time is a challenging aspect of epilepsy management. The evidence of maintained efficacy in the long term and the trend toward improvement over time make VNS an option.

In Patients Undergoing VNS Therapy, Does Rapid Stimulation (Usual VNS Settings Are 7 Seconds "On" and 30 Seconds "Off") Improve Seizure Frequency More Often Than Standard Stimulation Settings (30 Seconds "On" and 300 Seconds "Off")?

Conclusion

These 3 Class III studies were underpowered to detect a difference in efficacy between rapid stimulation (7 seconds "on," 30 seconds "off") used either after standard stimulation (30 seconds "on," 300 seconds "off") was unsuccessful or as an initial treatment setting.

Recommendation

Optimal VNS settings are still unknown, and the evidence is insufficient to support a recommendation for the use of standard stimulation vs. rapid stimulation to reduce seizure occurrence (Level U).

Clinical Context

Rapid cycling increases the duty cycle and hastens the need for battery replacement; therefore, when used, the efficacy of rapid cycling should be carefully assessed.

In Patients Undergoing VNS Therapy, Does Using Additional Magnet-Activated Stimulation Trains for Auras or at Seizure Onset Interrupt Seizures Relative to Not Using Additional Magnet-Induced Stimulation Trains for Auras or at Seizure Onset?

Conclusion

Based on data from 2 Class III studies, seizure abortion with magnet-activated stimulation is possibly associated with overall response to VNS therapy. Based on 3 Class III studies, magnet-activated stimulation may be expected to abort seizures one-fourth to two-thirds of the time when used during seizure auras (one Class III study omitted because it was not generalizable).

Recommendation

Patients may be counseled that VNS magnet activation may be associated with seizure abortion when used at the time of seizure auras (Level C) and that seizure abortion with magnet use may be associated with overall response to VNS treatment (Level C).

In Patients Undergoing VNS Therapy, Have New Safety Concerns Emerged Since the Last Assessment?

Clinical Context

Current physician attention to intraoperative rhythm disturbances from VNS use need not be changed. The paroxysmal nature of epilepsy poses a challenge for identifying a cardiac rhythm disturbance as device-related rather than as an additional seizure manifestation. Video electroencephalogram (EEG) and electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring of new-onset events that might be cardiac-related would be warranted to exclude this possibility in what is likely to be a small number of patients. Reduced sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) rates over time is an important finding associated with VNS therapy; in a cohort of 1,819 individuals followed 3,176.3 person-years from VNS implantation, the SUDEP rate was 5.5 per 1,000 over the first 2 years but only 1.7 per 1,000 thereafter. The clinical importance of the effect of VNS on sleep apnea and treatment is unclear, but caution regarding VNS use in this setting is suggested.

In Children Undergoing VNS Therapy, Do Adverse Events (AEs) Differ from Those in Adults?

Clinical Context

Children may have greater risk for wound infection than adults due to behaviors more common in children. Extra vigilance in monitoring for occurrence of site infection in children should be undertaken.

Definitions:

Classification of Evidence for Therapeutic Intervention

Class I: A randomized, controlled clinical trial of the intervention of interest with masked or objective outcome assessment, in a representative population. Relevant baseline characteristics are presented and substantially equivalent among treatment groups or there is appropriate statistical adjustment for differences.

The following are also required:

- Concealed allocation

- Primary outcome(s) clearly defined

- Exclusion/inclusion criteria clearly defined

- Adequate accounting for dropouts (with at least 80% of enrolled subjects completing the study) and crossovers with numbers sufficiently low to have minimal potential for bias.

- For noninferiority or equivalence trials claiming to prove efficacy for one or both drugs, the following are also required*

- The authors explicitly state the clinically meaningful difference to be excluded by defining the threshold for equivalence or noninferiority.

- The standard treatment used in the study is substantially similar to that used in previous studies establishing efficacy of the standard treatment (e.g., for a drug, the mode of administration, dose and dosage adjustments are similar to those previously shown to be effective).

- The inclusion and exclusion criteria for patient selection and the outcomes of patients on the standard treatment are comparable to those of previous studies establishing efficacy of the standard treatment.

- The interpretation of the results of the study is based upon a per protocol analysis that takes into account dropouts or crossovers.

Class II: A randomized controlled clinical trial of the intervention of interest in a representative population with masked or objective outcome assessment that lacks one criteria a–e above or a prospective matched cohort study with masked or objective outcome assessment in a representative population that meets b–e above. Relevant baseline characteristics are presented and substantially equivalent among treatment groups or there is appropriate statistical adjustment for differences.

Class III: All other controlled trials (including well-defined natural history controls or patients serving as own controls) in a representative population, where outcome is independently assessed, or independently derived by objective outcome measurement.**

Class IV: Studies not meeting Class I, II, or III criteria including consensus or expert opinion.

*Note that numbers 1-3 in Class Ie are required for Class II in equivalence trials. If any one of the three is missing, the class is automatically downgraded to Class III.

**Objective outcome measurement: an outcome measure that is unlikely to be affected by an observer's (patient, treating physician, investigator) expectation or bias (e.g., blood tests, administrative outcome data).

Classification of Recommendations

Level A = Established as effective, ineffective or harmful (or established as useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. (Level A rating requires at least two consistent Class I studies.*)

Level B = Probably effective, ineffective or harmful (or probably useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. (Level B rating requires at least one Class I study or two consistent Class II studies.)

Level C = Possibly effective, ineffective or harmful (or possibly useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. (Level C rating requires at least one Class II study or two consistent Class III studies.)

Level U = Data inadequate or conflicting; given current knowledge, treatment (test, predictor) is unproven.

*In exceptional cases, one convincing Class I study may suffice for an "A" recommendation if 1) all criteria are met, 2) the magnitude of effect is large (relative rate improved outcome >5 and the lower limit of the confidence interval is >2).

In Children with Epilepsy, Is Using Adjunctive Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) Therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction Better Than Not Using Adjunctive VNS therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction?

Conclusion

Based on data from 14 Class III studies, VNS is possibly effective in achieving >50% seizure frequency reduction (responder rate). In the pooled analysis of 481 children, the responder rate was 55% (95% confidence interval [CI] 51%–59%), but there was significant heterogeneity in the data. Two of the 16 studies were not included in the analysis because either they did not provide information about responder rate or they included a significant number (>20%) of adults in their population. The pooled seizure freedom rate was 7% (95% CI 5%–10%).

Recommendation

VNS may be considered as adjunctive treatment for children with partial or generalized epilepsy (Level C).

Clinical Context

VNS may be considered a possibly effective option after a child with medication-resistant epilepsy has been declared a poor surgical candidate or has had unsuccessful surgery.

In Patients with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (LGS), Is Using Adjunctive VNS Therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction Better Than Not Using Adjunctive VNS Therapy for Seizure Frequency Reduction?

Conclusion

Based on data from 4 Class III studies, VNS is possibly effective in achieving >50% seizure frequency reduction in patients with LGS. The pooled analysis of 113 patients with LGS (including data from articles with multiple seizure types where LGS data were parsed out) yielded a 55% (95% CI 46%–64%) responder rate.

Recommendation

VNS may be considered in patients with LGS (Level C).

Clinical Context

The responder rate for patients with LGS does not appear to differ from that of the general population of patients with medication-resistant epilepsy.

In Patients with Epilepsy, Is Using VNS Associated with Mood Improvement?

Conclusion

Based on data from 2 Class III studies, VNS is possibly effective for mood improvement in adults with epilepsy.

Recommendation

In adult patients receiving VNS for epilepsy, improvement in mood may be an additional benefit (Level C).

Clinical Context

Depression is a common comorbidity for people with epilepsy. VNS may provide an additional benefit by improving mood in some patients; however, the potential for mood improvement should be considered a secondary rather than a primary reason for VNS implantation. The evidence does not clearly support an independent effect on mood in this complex population.

In Patients with Epilepsy, Is VNS Use Associated with Reduced Seizure Frequency Over Time?

Conclusion

Based on data from 2 Class III studies, VNS is possibly associated with an increase in ≥50% seizure frequency reduction rates of 7% from 1 to 5 years postimplantation.

Recommendation

VNS may be considered progressively effective in patients over multiple years of exposure (Level C).

Clinical Context

The loss of medication efficacy over time is a challenging aspect of epilepsy management. The evidence of maintained efficacy in the long term and the trend toward improvement over time make VNS an option.

In Patients Undergoing VNS Therapy, Does Rapid Stimulation (Usual VNS Settings Are 7 Seconds "On" and 30 Seconds "Off") Improve Seizure Frequency More Often Than Standard Stimulation Settings (30 Seconds "On" and 300 Seconds "Off")?

Conclusion

These 3 Class III studies were underpowered to detect a difference in efficacy between rapid stimulation (7 seconds "on," 30 seconds "off") used either after standard stimulation (30 seconds "on," 300 seconds "off") was unsuccessful or as an initial treatment setting.

Recommendation

Optimal VNS settings are still unknown, and the evidence is insufficient to support a recommendation for the use of standard stimulation vs. rapid stimulation to reduce seizure occurrence (Level U).

Clinical Context

Rapid cycling increases the duty cycle and hastens the need for battery replacement; therefore, when used, the efficacy of rapid cycling should be carefully assessed.

In Patients Undergoing VNS Therapy, Does Using Additional Magnet-Activated Stimulation Trains for Auras or at Seizure Onset Interrupt Seizures Relative to Not Using Additional Magnet-Induced Stimulation Trains for Auras or at Seizure Onset?

Conclusion

Based on data from 2 Class III studies, seizure abortion with magnet-activated stimulation is possibly associated with overall response to VNS therapy. Based on 3 Class III studies, magnet-activated stimulation may be expected to abort seizures one-fourth to two-thirds of the time when used during seizure auras (one Class III study omitted because it was not generalizable).

Recommendation

Patients may be counseled that VNS magnet activation may be associated with seizure abortion when used at the time of seizure auras (Level C) and that seizure abortion with magnet use may be associated with overall response to VNS treatment (Level C).

In Patients Undergoing VNS Therapy, Have New Safety Concerns Emerged Since the Last Assessment?

Clinical Context

Current physician attention to intraoperative rhythm disturbances from VNS use need not be changed. The paroxysmal nature of epilepsy poses a challenge for identifying a cardiac rhythm disturbance as device-related rather than as an additional seizure manifestation. Video electroencephalogram (EEG) and electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring of new-onset events that might be cardiac-related would be warranted to exclude this possibility in what is likely to be a small number of patients. Reduced sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) rates over time is an important finding associated with VNS therapy; in a cohort of 1,819 individuals followed 3,176.3 person-years from VNS implantation, the SUDEP rate was 5.5 per 1,000 over the first 2 years but only 1.7 per 1,000 thereafter. The clinical importance of the effect of VNS on sleep apnea and treatment is unclear, but caution regarding VNS use in this setting is suggested.

In Children Undergoing VNS Therapy, Do Adverse Events (AEs) Differ from Those in Adults?

Clinical Context

Children may have greater risk for wound infection than adults due to behaviors more common in children. Extra vigilance in monitoring for occurrence of site infection in children should be undertaken.

Definitions:

Classification of Evidence for Therapeutic Intervention

Class I: A randomized, controlled clinical trial of the intervention of interest with masked or objective outcome assessment, in a representative population. Relevant baseline characteristics are presented and substantially equivalent among treatment groups or there is appropriate statistical adjustment for differences.

The following are also required:

- Concealed allocation

- Primary outcome(s) clearly defined

- Exclusion/inclusion criteria clearly defined

- Adequate accounting for dropouts (with at least 80% of enrolled subjects completing the study) and crossovers with numbers sufficiently low to have minimal potential for bias.

- For noninferiority or equivalence trials claiming to prove efficacy for one or both drugs, the following are also required*

- The authors explicitly state the clinically meaningful difference to be excluded by defining the threshold for equivalence or noninferiority.

- The standard treatment used in the study is substantially similar to that used in previous studies establishing efficacy of the standard treatment (e.g., for a drug, the mode of administration, dose and dosage adjustments are similar to those previously shown to be effective).

- The inclusion and exclusion criteria for patient selection and the outcomes of patients on the standard treatment are comparable to those of previous studies establishing efficacy of the standard treatment.

- The interpretation of the results of the study is based upon a per protocol analysis that takes into account dropouts or crossovers.

Class II: A randomized controlled clinical trial of the intervention of interest in a representative population with masked or objective outcome assessment that lacks one criteria a–e above or a prospective matched cohort study with masked or objective outcome assessment in a representative population that meets b–e above. Relevant baseline characteristics are presented and substantially equivalent among treatment groups or there is appropriate statistical adjustment for differences.

Class III: All other controlled trials (including well-defined natural history controls or patients serving as own controls) in a representative population, where outcome is independently assessed, or independently derived by objective outcome measurement.**

Class IV: Studies not meeting Class I, II, or III criteria including consensus or expert opinion.

*Note that numbers 1-3 in Class Ie are required for Class II in equivalence trials. If any one of the three is missing, the class is automatically downgraded to Class III.

**Objective outcome measurement: an outcome measure that is unlikely to be affected by an observer's (patient, treating physician, investigator) expectation or bias (e.g., blood tests, administrative outcome data).

Classification of Recommendations

Level A = Established as effective, ineffective or harmful (or established as useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. (Level A rating requires at least two consistent Class I studies.*)

Level B = Probably effective, ineffective or harmful (or probably useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. (Level B rating requires at least one Class I study or two consistent Class II studies.)

Level C = Possibly effective, ineffective or harmful (or possibly useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. (Level C rating requires at least one Class II study or two consistent Class III studies.)

Level U = Data inadequate or conflicting; given current knowledge, treatment (test, predictor) is unproven.

*In exceptional cases, one convincing Class I study may suffice for an "A" recommendation if 1) all criteria are met, 2) the magnitude of effect is large (relative rate improved outcome >5 and the lower limit of the confidence interval is >2).

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the evidence since the 1999 assessment regarding efficacy and safety of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for epilepsy, currently approved as adjunctive therapy for partial-onset seizures in patients >12 years.

METHODS: We reviewed the literature and identified relevant published studies. We classified these studies according to the American Academy of Neurology evidence-based methodology.

Guidelines are copyright © 2014 American Academy of Neurology. All rights reserved. The summary is provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Sunshine Act – a reminder

Last year, when the Physician Payment Sunshine Act became law, I recommended that all physicians involved in any sort of financial relationship with the pharmaceutical industry review the data reported about them prior to public posting of the information. Since that posting is due to occur at the end of this month, a reminder is in order.

Under a new bureaucracy created by the Affordable Care Act – formally called the Open Payments program – all manufacturers of drugs, devices, and medical supplies covered by federal health care programs must report any financial interactions with physicians and teaching hospitals to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Reportable interactions include consulting; food; ownership or investment interest; direct compensation for speakers at education programs; and research. Compensation for conducting clinical trials must be reported, but will not be posted on the website until the product receives approval from the Food and Drug Administration or until 4 years after the payment, whichever is earlier. Payments for trials involving a new indication for an approved drug will be posted immediately.

There are a number of specific exclusions, such as certified and accredited continuing medical education activities funded by manufacturers, and product samples for patient use. Medical students and residents are excluded entirely.

Under the law, you are allowed to review your data and seek corrections before it is published. Publication is scheduled to occur on Sept. 30, so if you have not yet done this, there is no time to waste. Although you will have an additional 2 years to pursue corrections after the online content goes live, any erroneous information will remain on the site until corrections can be made, so the best time to find and fix errors is now.

If you don’t see drug reps, accept sponsored lunches, or give sponsored talks, don’t assume that you won’t be on the website. Check anyway; you might be indirectly involved in a compensation situation that you were not aware of, or you may have been reported in error.

To review your data, register at the CMS Enterprise Portal, and request access to the Open Payments system.

Once you are satisfied that your interactions have been reported accurately, the question of what effect the law will have on research, continuing education, and private practice remains. The short answer is that no one knows. Much will depend on how the public interprets the data – if they take notice at all.

Sunshine laws have been in effect for several years in six states: California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and West Virginia; plus the District of Columbia. (Maine repealed its law in 2011.) Observers disagree on their impact. Studies in Maine and West Virginia showed no significant public reaction or changes in prescribing patterns, according to a 2012 article in Archives of Internal Medicine (Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:819-21).

Potential effects on physician-patient interactions are equally unclear. Do patients think less of doctors who accept the occasional industry-sponsored lunch for their employees? Do they think more of doctors who speak at meetings or conduct industry-sponsored clinical research? There are no objective data, as far as I know.

My guess is that attorneys, activists, and the occasional reporter will data-mine the website on a regular basis, and perhaps use their findings as ammunition in any agenda that they might be pushing, but few patients will ever bother to visit. Nevertheless, you should review each year’s reportage to ensure the accuracy of anything posted about you.

The data must be reported to CMS by March 31 each year, so you will need to set aside time each April or May to review it. If you have many or complex industry relationships, you should probably contact each company in January or February and ask to see the data before it is submitted. Then, review it again once CMS gets it, to be sure nothing was changed. A free app is available to help physicians track payments and other reportable industry interactions; search for "Open Payments" at your favorite app store.

Maintaining accurate financial records has always been important, but it will be even more so now, to effectively dispute any inconsistencies. While the extra work may turn out to have been unnecessary, it is still a prudent precaution, given the possible consequences of any increased government or public scrutiny that may (or may not) result.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Skin & Allergy News.

Last year, when the Physician Payment Sunshine Act became law, I recommended that all physicians involved in any sort of financial relationship with the pharmaceutical industry review the data reported about them prior to public posting of the information. Since that posting is due to occur at the end of this month, a reminder is in order.

Under a new bureaucracy created by the Affordable Care Act – formally called the Open Payments program – all manufacturers of drugs, devices, and medical supplies covered by federal health care programs must report any financial interactions with physicians and teaching hospitals to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Reportable interactions include consulting; food; ownership or investment interest; direct compensation for speakers at education programs; and research. Compensation for conducting clinical trials must be reported, but will not be posted on the website until the product receives approval from the Food and Drug Administration or until 4 years after the payment, whichever is earlier. Payments for trials involving a new indication for an approved drug will be posted immediately.

There are a number of specific exclusions, such as certified and accredited continuing medical education activities funded by manufacturers, and product samples for patient use. Medical students and residents are excluded entirely.

Under the law, you are allowed to review your data and seek corrections before it is published. Publication is scheduled to occur on Sept. 30, so if you have not yet done this, there is no time to waste. Although you will have an additional 2 years to pursue corrections after the online content goes live, any erroneous information will remain on the site until corrections can be made, so the best time to find and fix errors is now.

If you don’t see drug reps, accept sponsored lunches, or give sponsored talks, don’t assume that you won’t be on the website. Check anyway; you might be indirectly involved in a compensation situation that you were not aware of, or you may have been reported in error.

To review your data, register at the CMS Enterprise Portal, and request access to the Open Payments system.

Once you are satisfied that your interactions have been reported accurately, the question of what effect the law will have on research, continuing education, and private practice remains. The short answer is that no one knows. Much will depend on how the public interprets the data – if they take notice at all.

Sunshine laws have been in effect for several years in six states: California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and West Virginia; plus the District of Columbia. (Maine repealed its law in 2011.) Observers disagree on their impact. Studies in Maine and West Virginia showed no significant public reaction or changes in prescribing patterns, according to a 2012 article in Archives of Internal Medicine (Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:819-21).

Potential effects on physician-patient interactions are equally unclear. Do patients think less of doctors who accept the occasional industry-sponsored lunch for their employees? Do they think more of doctors who speak at meetings or conduct industry-sponsored clinical research? There are no objective data, as far as I know.

My guess is that attorneys, activists, and the occasional reporter will data-mine the website on a regular basis, and perhaps use their findings as ammunition in any agenda that they might be pushing, but few patients will ever bother to visit. Nevertheless, you should review each year’s reportage to ensure the accuracy of anything posted about you.

The data must be reported to CMS by March 31 each year, so you will need to set aside time each April or May to review it. If you have many or complex industry relationships, you should probably contact each company in January or February and ask to see the data before it is submitted. Then, review it again once CMS gets it, to be sure nothing was changed. A free app is available to help physicians track payments and other reportable industry interactions; search for "Open Payments" at your favorite app store.

Maintaining accurate financial records has always been important, but it will be even more so now, to effectively dispute any inconsistencies. While the extra work may turn out to have been unnecessary, it is still a prudent precaution, given the possible consequences of any increased government or public scrutiny that may (or may not) result.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Skin & Allergy News.