User login

Shrink Rap News: Belgian prison case signals warning for American correctional psychiatrists

I struggled to decide where to begin this week’s column in the wake of news that a Belgian inmate had been granted his request for physician-assisted suicide. Beyond stifling an instinctive “oh my god” response, I felt an immediate regret that I predicted something like this would happen eventually when I wrote about state laws regarding assisted suicide for a previous column. I just didn’t expect it to happen quite so soon, or to involve a prison inmate.

According to an Associated Press story published in the Washington Post, inmate Frank Van Den Bleeken had served almost 30 years for the rape and murder of an unspecified number of women, and had requested euthanasia on the basis of having a mental condition deemed incurable by the Belgian courts. The story didn’t specify exactly what that condition was, or why it was untreatable, but the inmate alleged that he couldn’t live with the knowledge that he would be a danger to society again upon release. I’m surprised at this newly developed sense of conscience, since it apparently wasn’t enough to prevent him from committing the crimes in the first place. If his incurable condition was sociopathy, then some intervention must have worked to lead to this remarkable development of empathy. Setting skepticism aside, the case does raise serious concerns for psychiatrists working in jails and prisons.

Adopted in 2002, the Belgian law defines euthanasia as “intentionally terminating life by someone other than the person concerned, at the latter’s request.” The individual making the request must do so competently and without external pressure if his condition is “constant and medically futile,” leading to “unbearable physical or mental suffering that cannot be alleviated.” A physician cannot be compelled to perform the killing but must notify the patient of the refusal and must forward the patient’s medical record to another physician of the patient’s choosing.

It seems we’ve arrived at a strange mirror-inverse world of medicine in correctional health care now. Given that the World Health Organization has proscribed the force feeding of prisoners, a correctional physician may not only be forbidden from intervening to save a life, he may also be called upon to intentionally end one. If there were ever a situation that calls for scrupulous medical integrity, this is it.

I’m not shocked by the thought that an inmate might request suicide. Most prisoners are young, are male, and have active substance use disorders – three commonly accepted risk factors for suicide – even before walking into the facility. What concerns me more is the thought that in all likelihood, requests for assisted suicide by prisoners are going to be considered less carefully than those by noncriminals. Given the horrific nature of some offenses, it would be easy to imagine a court turning a semiblind eye to other factors influencing a request to die. It would be easy to view suicide as a rational choice for someone serving a life term, rather than as a product of a treatable psychiatric condition. Courts might also be unwilling to examine the underlying conditions of confinement or an institutional culture that would lead one to accept death as a viable alternative to life in a threatening or inhumane environment. Prisoners are also less likely to have outside supports or involved family members to provide more factual context to the decision to seek physician-assisted suicide, or to challenge the competence of the petitioner. The institution itself might be unwilling to acknowledge inadequate health care services, or lack of palliative care, for terminally ill prisoners.

Belgium and the Netherlands have expanded physician-assisted suicide processes far beyond anything presently contemplated here in the United States, but petitions for assisted suicide have been increasing there year after year, and an increasing number of American states have been considering this legislation. As the Van Den Bleeken case illustrates, only the professional integrity of physicians may stand between poorly considered laws and a select group of vulnerable human beings.

Dr. Hanson is a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

I struggled to decide where to begin this week’s column in the wake of news that a Belgian inmate had been granted his request for physician-assisted suicide. Beyond stifling an instinctive “oh my god” response, I felt an immediate regret that I predicted something like this would happen eventually when I wrote about state laws regarding assisted suicide for a previous column. I just didn’t expect it to happen quite so soon, or to involve a prison inmate.

According to an Associated Press story published in the Washington Post, inmate Frank Van Den Bleeken had served almost 30 years for the rape and murder of an unspecified number of women, and had requested euthanasia on the basis of having a mental condition deemed incurable by the Belgian courts. The story didn’t specify exactly what that condition was, or why it was untreatable, but the inmate alleged that he couldn’t live with the knowledge that he would be a danger to society again upon release. I’m surprised at this newly developed sense of conscience, since it apparently wasn’t enough to prevent him from committing the crimes in the first place. If his incurable condition was sociopathy, then some intervention must have worked to lead to this remarkable development of empathy. Setting skepticism aside, the case does raise serious concerns for psychiatrists working in jails and prisons.

Adopted in 2002, the Belgian law defines euthanasia as “intentionally terminating life by someone other than the person concerned, at the latter’s request.” The individual making the request must do so competently and without external pressure if his condition is “constant and medically futile,” leading to “unbearable physical or mental suffering that cannot be alleviated.” A physician cannot be compelled to perform the killing but must notify the patient of the refusal and must forward the patient’s medical record to another physician of the patient’s choosing.

It seems we’ve arrived at a strange mirror-inverse world of medicine in correctional health care now. Given that the World Health Organization has proscribed the force feeding of prisoners, a correctional physician may not only be forbidden from intervening to save a life, he may also be called upon to intentionally end one. If there were ever a situation that calls for scrupulous medical integrity, this is it.

I’m not shocked by the thought that an inmate might request suicide. Most prisoners are young, are male, and have active substance use disorders – three commonly accepted risk factors for suicide – even before walking into the facility. What concerns me more is the thought that in all likelihood, requests for assisted suicide by prisoners are going to be considered less carefully than those by noncriminals. Given the horrific nature of some offenses, it would be easy to imagine a court turning a semiblind eye to other factors influencing a request to die. It would be easy to view suicide as a rational choice for someone serving a life term, rather than as a product of a treatable psychiatric condition. Courts might also be unwilling to examine the underlying conditions of confinement or an institutional culture that would lead one to accept death as a viable alternative to life in a threatening or inhumane environment. Prisoners are also less likely to have outside supports or involved family members to provide more factual context to the decision to seek physician-assisted suicide, or to challenge the competence of the petitioner. The institution itself might be unwilling to acknowledge inadequate health care services, or lack of palliative care, for terminally ill prisoners.

Belgium and the Netherlands have expanded physician-assisted suicide processes far beyond anything presently contemplated here in the United States, but petitions for assisted suicide have been increasing there year after year, and an increasing number of American states have been considering this legislation. As the Van Den Bleeken case illustrates, only the professional integrity of physicians may stand between poorly considered laws and a select group of vulnerable human beings.

Dr. Hanson is a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

I struggled to decide where to begin this week’s column in the wake of news that a Belgian inmate had been granted his request for physician-assisted suicide. Beyond stifling an instinctive “oh my god” response, I felt an immediate regret that I predicted something like this would happen eventually when I wrote about state laws regarding assisted suicide for a previous column. I just didn’t expect it to happen quite so soon, or to involve a prison inmate.

According to an Associated Press story published in the Washington Post, inmate Frank Van Den Bleeken had served almost 30 years for the rape and murder of an unspecified number of women, and had requested euthanasia on the basis of having a mental condition deemed incurable by the Belgian courts. The story didn’t specify exactly what that condition was, or why it was untreatable, but the inmate alleged that he couldn’t live with the knowledge that he would be a danger to society again upon release. I’m surprised at this newly developed sense of conscience, since it apparently wasn’t enough to prevent him from committing the crimes in the first place. If his incurable condition was sociopathy, then some intervention must have worked to lead to this remarkable development of empathy. Setting skepticism aside, the case does raise serious concerns for psychiatrists working in jails and prisons.

Adopted in 2002, the Belgian law defines euthanasia as “intentionally terminating life by someone other than the person concerned, at the latter’s request.” The individual making the request must do so competently and without external pressure if his condition is “constant and medically futile,” leading to “unbearable physical or mental suffering that cannot be alleviated.” A physician cannot be compelled to perform the killing but must notify the patient of the refusal and must forward the patient’s medical record to another physician of the patient’s choosing.

It seems we’ve arrived at a strange mirror-inverse world of medicine in correctional health care now. Given that the World Health Organization has proscribed the force feeding of prisoners, a correctional physician may not only be forbidden from intervening to save a life, he may also be called upon to intentionally end one. If there were ever a situation that calls for scrupulous medical integrity, this is it.

I’m not shocked by the thought that an inmate might request suicide. Most prisoners are young, are male, and have active substance use disorders – three commonly accepted risk factors for suicide – even before walking into the facility. What concerns me more is the thought that in all likelihood, requests for assisted suicide by prisoners are going to be considered less carefully than those by noncriminals. Given the horrific nature of some offenses, it would be easy to imagine a court turning a semiblind eye to other factors influencing a request to die. It would be easy to view suicide as a rational choice for someone serving a life term, rather than as a product of a treatable psychiatric condition. Courts might also be unwilling to examine the underlying conditions of confinement or an institutional culture that would lead one to accept death as a viable alternative to life in a threatening or inhumane environment. Prisoners are also less likely to have outside supports or involved family members to provide more factual context to the decision to seek physician-assisted suicide, or to challenge the competence of the petitioner. The institution itself might be unwilling to acknowledge inadequate health care services, or lack of palliative care, for terminally ill prisoners.

Belgium and the Netherlands have expanded physician-assisted suicide processes far beyond anything presently contemplated here in the United States, but petitions for assisted suicide have been increasing there year after year, and an increasing number of American states have been considering this legislation. As the Van Den Bleeken case illustrates, only the professional integrity of physicians may stand between poorly considered laws and a select group of vulnerable human beings.

Dr. Hanson is a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work. The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

AUDIO: Franchiser hopes to put dermatology ‘back in the hands of the dermatologist’

Dermatology has yet to conquer the cosmetic corner of the specialty. That’s according to Dr. Leslie S. Baumann of the Miami-based Skin Type Solutions, who explains a new franchise model she says will help “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.”

In this interview, Dr. Baumann, who writes the Cosmeceutical Critique column for Skin & Allergy News, explains her new franchise method for selling skin care products in the dermatologist’s office, and why she thinks it will “disrupt” business as usual in the retail skin care marketplace, including for online retailers.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” will be published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy,Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Dermatology has yet to conquer the cosmetic corner of the specialty. That’s according to Dr. Leslie S. Baumann of the Miami-based Skin Type Solutions, who explains a new franchise model she says will help “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.”

In this interview, Dr. Baumann, who writes the Cosmeceutical Critique column for Skin & Allergy News, explains her new franchise method for selling skin care products in the dermatologist’s office, and why she thinks it will “disrupt” business as usual in the retail skin care marketplace, including for online retailers.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” will be published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy,Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Dermatology has yet to conquer the cosmetic corner of the specialty. That’s according to Dr. Leslie S. Baumann of the Miami-based Skin Type Solutions, who explains a new franchise model she says will help “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.”

In this interview, Dr. Baumann, who writes the Cosmeceutical Critique column for Skin & Allergy News, explains her new franchise method for selling skin care products in the dermatologist’s office, and why she thinks it will “disrupt” business as usual in the retail skin care marketplace, including for online retailers.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” will be published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy,Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Master Class: Office evaluation for incontinence

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

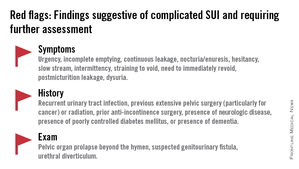

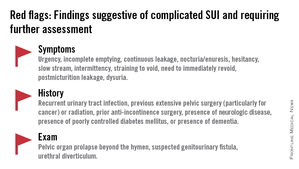

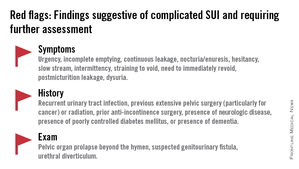

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Gemcitabine: Best Alone or in Combination?

Gemcitabine (GEM) is the standard treatment for patients with locally advanced/metastatic pancreatic cancer (LA/MPC). Many studies have focused on finding combinations that might extend the efficacy of GEM. However, most studies have not found an improvement in overall survival (OS) for patients using GEM combination therapy, say researchers from Beijing Friendship Hospital in China. That is until recently, when researchers found that compared with GEM monotherapy, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel plus GEM significantly improved OS (8.5 months vs 6.7 months; P < .001) and progression-free survival (5.5 months vs 3.7 months; P < .001).

Other research has found that combining GEM with platinum, fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan, biotherapy, and others, for example, marginally but significantly affects OS, again compared with GEM monotherapy (P = .001). The combinations were associated with increased toxicity.

According to the researchers, the use of targeted therapies in cancer treatment is a “significant focus” of cancer research and has brought great clinical benefits in treating a variety of solid tumors. Studies that combined drugs to target epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which is overexpressed in pancreatic tumors and associated with poor prognosis, had mixed results for patients with LA/MPC. This prompted researchers in this study to conduct a systematic survey of 10 randomized controlled trials: 3 phase 2 trials and 7 phase 3 trials. Of 3,899 patients, 1,989 received GEM + targeted agents and 1,910 received GEM as monotherapy or combined with placebo (PLC). In a subgroup of GEM + antiangiogenic agents, 733 patients received GEM + axitinib or bevacizumab and cilengitide, and 693 received GEM ± PLC.

No significant difference was seen in the OS rate between the GEM + targeted agents and GEM ± PLC groups (P = .85), and only a marginal difference was found in the 1-year survival rate (P = .05). In the subgroup analysis, the researchers found a significant increase in objective response rate with GEM + antiangiogenic agents vs GEM ± PLC (95% CI, 0.42-0.98; P = .04). However, they found no significant difference in OS, 1-year survival, or progression-free survival between those 2 groups.

The researchers advise further research concentrated on clarifying the “concrete targets” involved in the occurrence and progression of pancreatic cancer. They add that personalized therapy based on a patient’s stratification, tumor stage, and genetic background should also be considered.

Source

Li Q, Yuan Z, Yan H, Wen Z, Zhang R, Cao B. Clin Ther. 2014;36(7):1054-1063.

doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.066.

Gemcitabine (GEM) is the standard treatment for patients with locally advanced/metastatic pancreatic cancer (LA/MPC). Many studies have focused on finding combinations that might extend the efficacy of GEM. However, most studies have not found an improvement in overall survival (OS) for patients using GEM combination therapy, say researchers from Beijing Friendship Hospital in China. That is until recently, when researchers found that compared with GEM monotherapy, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel plus GEM significantly improved OS (8.5 months vs 6.7 months; P < .001) and progression-free survival (5.5 months vs 3.7 months; P < .001).

Other research has found that combining GEM with platinum, fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan, biotherapy, and others, for example, marginally but significantly affects OS, again compared with GEM monotherapy (P = .001). The combinations were associated with increased toxicity.

According to the researchers, the use of targeted therapies in cancer treatment is a “significant focus” of cancer research and has brought great clinical benefits in treating a variety of solid tumors. Studies that combined drugs to target epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which is overexpressed in pancreatic tumors and associated with poor prognosis, had mixed results for patients with LA/MPC. This prompted researchers in this study to conduct a systematic survey of 10 randomized controlled trials: 3 phase 2 trials and 7 phase 3 trials. Of 3,899 patients, 1,989 received GEM + targeted agents and 1,910 received GEM as monotherapy or combined with placebo (PLC). In a subgroup of GEM + antiangiogenic agents, 733 patients received GEM + axitinib or bevacizumab and cilengitide, and 693 received GEM ± PLC.

No significant difference was seen in the OS rate between the GEM + targeted agents and GEM ± PLC groups (P = .85), and only a marginal difference was found in the 1-year survival rate (P = .05). In the subgroup analysis, the researchers found a significant increase in objective response rate with GEM + antiangiogenic agents vs GEM ± PLC (95% CI, 0.42-0.98; P = .04). However, they found no significant difference in OS, 1-year survival, or progression-free survival between those 2 groups.

The researchers advise further research concentrated on clarifying the “concrete targets” involved in the occurrence and progression of pancreatic cancer. They add that personalized therapy based on a patient’s stratification, tumor stage, and genetic background should also be considered.

Source

Li Q, Yuan Z, Yan H, Wen Z, Zhang R, Cao B. Clin Ther. 2014;36(7):1054-1063.

doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.066.

Gemcitabine (GEM) is the standard treatment for patients with locally advanced/metastatic pancreatic cancer (LA/MPC). Many studies have focused on finding combinations that might extend the efficacy of GEM. However, most studies have not found an improvement in overall survival (OS) for patients using GEM combination therapy, say researchers from Beijing Friendship Hospital in China. That is until recently, when researchers found that compared with GEM monotherapy, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel plus GEM significantly improved OS (8.5 months vs 6.7 months; P < .001) and progression-free survival (5.5 months vs 3.7 months; P < .001).

Other research has found that combining GEM with platinum, fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan, biotherapy, and others, for example, marginally but significantly affects OS, again compared with GEM monotherapy (P = .001). The combinations were associated with increased toxicity.

According to the researchers, the use of targeted therapies in cancer treatment is a “significant focus” of cancer research and has brought great clinical benefits in treating a variety of solid tumors. Studies that combined drugs to target epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which is overexpressed in pancreatic tumors and associated with poor prognosis, had mixed results for patients with LA/MPC. This prompted researchers in this study to conduct a systematic survey of 10 randomized controlled trials: 3 phase 2 trials and 7 phase 3 trials. Of 3,899 patients, 1,989 received GEM + targeted agents and 1,910 received GEM as monotherapy or combined with placebo (PLC). In a subgroup of GEM + antiangiogenic agents, 733 patients received GEM + axitinib or bevacizumab and cilengitide, and 693 received GEM ± PLC.

No significant difference was seen in the OS rate between the GEM + targeted agents and GEM ± PLC groups (P = .85), and only a marginal difference was found in the 1-year survival rate (P = .05). In the subgroup analysis, the researchers found a significant increase in objective response rate with GEM + antiangiogenic agents vs GEM ± PLC (95% CI, 0.42-0.98; P = .04). However, they found no significant difference in OS, 1-year survival, or progression-free survival between those 2 groups.

The researchers advise further research concentrated on clarifying the “concrete targets” involved in the occurrence and progression of pancreatic cancer. They add that personalized therapy based on a patient’s stratification, tumor stage, and genetic background should also be considered.

Source

Li Q, Yuan Z, Yan H, Wen Z, Zhang R, Cao B. Clin Ther. 2014;36(7):1054-1063.

doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.066.

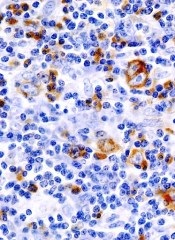

Dendritic cells promote Myc-driven lymphoma

Studies have shown that dendritic cells (DCs) can contribute to tumor growth and help shield the tumor from the immune system in colon, stomach, breast, and prostate cancer.

Now, researchers have found evidence suggesting this phenomenon also occurs in Myc-driven lymphomas.

The team has also identified the molecular mechanism that induces the immune cells to promote tumor growth.

They reported these findings in Nature Communications.

Uta Höpken, PhD, of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, Germany, and her colleagues investigated how DCs drive tumor in mouse models of Eµ-Myc lymphoma.

The team began by depleting DCs in these mice and found that tumor growth was delayed—the first clue that DCs are indeed associated with lymphoma growth.

Next, the researchers found that, after contact with lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly secrete immunomodulatory cytokines and growth factors. The cytokine secretion takes place in the spleen and lymph nodes.

Dr Höpken and her colleagues previously demonstrated that various forms of lymphoma cells settle in the lymph nodes and in the spleen, where they create their own survival niche. This process is regulated by selective cytokines and growth factors the researchers identified a few years ago.

“In these niches, almost everything is already there that the lymphoma cells as malignant B cells need to survive, including blood vessels and connective tissue cells [stromal cells],” Dr Höpken said. “The survival substances secreted by the DCs optimize the niche so that the tumors can grow better.”

This also means the DCs prevent the T lymphocytes from exercising their defensive function. Normally, healthy B or T cells settle in the respective B- or T-cell niches of the spleen and the lymph nodes to be made fit for immune defense.

“What is paradoxical is that the mouse lymphoma cells we studied—malignant B cells—found their survival niche in the T-cell zones of the lymph nodes and the spleen and not in the B-cell zones,” Dr Höpken said.

After making contact with the lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly upregulate C/EBPβ, a transcription factor that promotes the production of cytokines that mediate inflammation.

The researchers found that C/EBPβ regulates DCs. Without it, the cells could not secrete inflammatory cytokines. C/EBPβ also indirectly blocks apoptosis in the lymphoma cells, allowing the cancer cells to grow unchecked.

The team pointed out that, even if their model of Eµ-Myc lymphoma is not entirely comparable to B-cell lymphomas in humans, it shows that lymphoma cells and DCs interact—a previously unknown molecular mechanism.

Furthermore, these findings may have clinical applications. The researchers noted that the immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide induces downregulation of C/EBPβ, which is secreted by cancer cells.

So Dr Höpken and her colleagues believe it might be appropriate to approve the use of lenalidomide for patients with Myc B-cell lymphoma, as an addition to their existing treatment, to strengthen their immune defense. ![]()

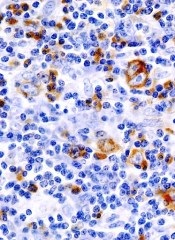

Studies have shown that dendritic cells (DCs) can contribute to tumor growth and help shield the tumor from the immune system in colon, stomach, breast, and prostate cancer.

Now, researchers have found evidence suggesting this phenomenon also occurs in Myc-driven lymphomas.

The team has also identified the molecular mechanism that induces the immune cells to promote tumor growth.

They reported these findings in Nature Communications.

Uta Höpken, PhD, of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, Germany, and her colleagues investigated how DCs drive tumor in mouse models of Eµ-Myc lymphoma.

The team began by depleting DCs in these mice and found that tumor growth was delayed—the first clue that DCs are indeed associated with lymphoma growth.

Next, the researchers found that, after contact with lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly secrete immunomodulatory cytokines and growth factors. The cytokine secretion takes place in the spleen and lymph nodes.

Dr Höpken and her colleagues previously demonstrated that various forms of lymphoma cells settle in the lymph nodes and in the spleen, where they create their own survival niche. This process is regulated by selective cytokines and growth factors the researchers identified a few years ago.

“In these niches, almost everything is already there that the lymphoma cells as malignant B cells need to survive, including blood vessels and connective tissue cells [stromal cells],” Dr Höpken said. “The survival substances secreted by the DCs optimize the niche so that the tumors can grow better.”

This also means the DCs prevent the T lymphocytes from exercising their defensive function. Normally, healthy B or T cells settle in the respective B- or T-cell niches of the spleen and the lymph nodes to be made fit for immune defense.

“What is paradoxical is that the mouse lymphoma cells we studied—malignant B cells—found their survival niche in the T-cell zones of the lymph nodes and the spleen and not in the B-cell zones,” Dr Höpken said.

After making contact with the lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly upregulate C/EBPβ, a transcription factor that promotes the production of cytokines that mediate inflammation.

The researchers found that C/EBPβ regulates DCs. Without it, the cells could not secrete inflammatory cytokines. C/EBPβ also indirectly blocks apoptosis in the lymphoma cells, allowing the cancer cells to grow unchecked.

The team pointed out that, even if their model of Eµ-Myc lymphoma is not entirely comparable to B-cell lymphomas in humans, it shows that lymphoma cells and DCs interact—a previously unknown molecular mechanism.

Furthermore, these findings may have clinical applications. The researchers noted that the immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide induces downregulation of C/EBPβ, which is secreted by cancer cells.

So Dr Höpken and her colleagues believe it might be appropriate to approve the use of lenalidomide for patients with Myc B-cell lymphoma, as an addition to their existing treatment, to strengthen their immune defense. ![]()

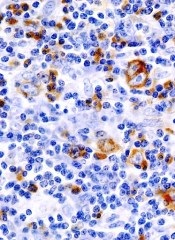

Studies have shown that dendritic cells (DCs) can contribute to tumor growth and help shield the tumor from the immune system in colon, stomach, breast, and prostate cancer.

Now, researchers have found evidence suggesting this phenomenon also occurs in Myc-driven lymphomas.

The team has also identified the molecular mechanism that induces the immune cells to promote tumor growth.

They reported these findings in Nature Communications.

Uta Höpken, PhD, of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, Germany, and her colleagues investigated how DCs drive tumor in mouse models of Eµ-Myc lymphoma.

The team began by depleting DCs in these mice and found that tumor growth was delayed—the first clue that DCs are indeed associated with lymphoma growth.

Next, the researchers found that, after contact with lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly secrete immunomodulatory cytokines and growth factors. The cytokine secretion takes place in the spleen and lymph nodes.

Dr Höpken and her colleagues previously demonstrated that various forms of lymphoma cells settle in the lymph nodes and in the spleen, where they create their own survival niche. This process is regulated by selective cytokines and growth factors the researchers identified a few years ago.

“In these niches, almost everything is already there that the lymphoma cells as malignant B cells need to survive, including blood vessels and connective tissue cells [stromal cells],” Dr Höpken said. “The survival substances secreted by the DCs optimize the niche so that the tumors can grow better.”

This also means the DCs prevent the T lymphocytes from exercising their defensive function. Normally, healthy B or T cells settle in the respective B- or T-cell niches of the spleen and the lymph nodes to be made fit for immune defense.

“What is paradoxical is that the mouse lymphoma cells we studied—malignant B cells—found their survival niche in the T-cell zones of the lymph nodes and the spleen and not in the B-cell zones,” Dr Höpken said.

After making contact with the lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly upregulate C/EBPβ, a transcription factor that promotes the production of cytokines that mediate inflammation.

The researchers found that C/EBPβ regulates DCs. Without it, the cells could not secrete inflammatory cytokines. C/EBPβ also indirectly blocks apoptosis in the lymphoma cells, allowing the cancer cells to grow unchecked.

The team pointed out that, even if their model of Eµ-Myc lymphoma is not entirely comparable to B-cell lymphomas in humans, it shows that lymphoma cells and DCs interact—a previously unknown molecular mechanism.

Furthermore, these findings may have clinical applications. The researchers noted that the immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide induces downregulation of C/EBPβ, which is secreted by cancer cells.

So Dr Höpken and her colleagues believe it might be appropriate to approve the use of lenalidomide for patients with Myc B-cell lymphoma, as an addition to their existing treatment, to strengthen their immune defense. ![]()

Product appears safe, effective in rel/ref ALL

Credit: Bill Branson

Eryaspase, a product consisting of L-asparaginase encapsulated in red blood cells, may be safer and more effective than native E coli L-asparaginase, results of a phase 2/3 study suggest.

In patients with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), eryaspase given in combination with chemotherapy produced a higher complete response rate and fewer allergic reactions than native E coli L-asparaginase in combination with chemotherapy.

Eryaspase was also well-tolerated in patients who had previously experienced allergic reactions to L-asparaginase.

ERYTECH Pharma, the company developing eryaspase, recently announced these results from the GRASPIVOTALL trial.

The study included 80 children and adults with relapsed or refractory ALL, who were randomized to 1 of 3 treatment arms.

In the first 2 arms, researchers compared eryaspase to native E coli L-asparaginase, both in combination with standard chemotherapy (COOPRALL), in patients without prior allergies to L-asparaginase. In the third arm, the team evaluated eryaspase for patients who have experienced allergic reactions related to asparaginase in their first-line treatment.

The primary endpoint of the study consisted of 2 objectives: (a) superior safety, expressed as a significant reduction of the incidence of allergic reactions with eryaspase compared to native L-asparaginase, and (b) noninferior duration of asparaginase activity above the threshold of 100 IU/L during the induction phase in the nonallergic patients. Both endpoints needed to be met for the study to be considered positive.

The main secondary efficacy endpoints included complete response, minimal residual disease, event-free survival, and overall survival.

At 1 year of follow-up, both primary endpoints were met. There was a significant reduction of allergic reactions in the eryaspase arm compared to the native L-asparaginase arm—0% (0/26) and 42.9% (12/28), respectively (P<0.001).

And there was a significant increase in the duration of circulating asparaginase activity in the eryaspase arm compared to the native L-asparaginase arm. Asparaginase levels were maintained above 100 IU/L for an average of 20.5 days with up to 2 injections during the first month of treatment with eryaspase, compared to 9.2 days in the native L-asparaginase arm, with up to 8 injections of L-asparaginase (P<0.001).

In addition, the complete response rate was higher with eryaspase. At the end of the induction phase, 71.4% of patients (n=15) in the eryaspase arm had a complete response, compared to 42.3% of patients (n=11) in the native L-asparaginase arm.

Finally, the study showed that eryaspase is well-tolerated by patients with previous allergies to L-asparaginase. Two of the 26 patients with prior allergies to L-asparaginase experienced mild allergic reactions to eryaspase.

“The results of this study are an important step forward for the treatment of ALL patients that are at risk to receive L-asparaginase, which remains an important unmet medical need,” said Yves Betrand, MD, of the Institute for Pediatric Hematology and Oncology in Lyon, France.

“The virtual absence of allergic reactions, also in patients with prior allergies to L-asparaginase, is very encouraging.”

The analysis of additional secondary and exploratory endpoints for this study is ongoing. ERYTECH said results will be available later this year and are set to be presented at an upcoming scientific conference.

Based on the results of this and earlier studies of eryaspase, ERYTECH intends to submit its application for European Marketing Authorization in the first half of 2015.

The company also plans to accelerate the product’s development in ALL in the US and to launch phase 2 clinical trials in additional oncology indications with high unmet medical need. A phase 2b study of eryaspase in acute myeloid leukemia is already underway, with more than half of the patients enrolled. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

Eryaspase, a product consisting of L-asparaginase encapsulated in red blood cells, may be safer and more effective than native E coli L-asparaginase, results of a phase 2/3 study suggest.

In patients with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), eryaspase given in combination with chemotherapy produced a higher complete response rate and fewer allergic reactions than native E coli L-asparaginase in combination with chemotherapy.

Eryaspase was also well-tolerated in patients who had previously experienced allergic reactions to L-asparaginase.

ERYTECH Pharma, the company developing eryaspase, recently announced these results from the GRASPIVOTALL trial.

The study included 80 children and adults with relapsed or refractory ALL, who were randomized to 1 of 3 treatment arms.

In the first 2 arms, researchers compared eryaspase to native E coli L-asparaginase, both in combination with standard chemotherapy (COOPRALL), in patients without prior allergies to L-asparaginase. In the third arm, the team evaluated eryaspase for patients who have experienced allergic reactions related to asparaginase in their first-line treatment.

The primary endpoint of the study consisted of 2 objectives: (a) superior safety, expressed as a significant reduction of the incidence of allergic reactions with eryaspase compared to native L-asparaginase, and (b) noninferior duration of asparaginase activity above the threshold of 100 IU/L during the induction phase in the nonallergic patients. Both endpoints needed to be met for the study to be considered positive.

The main secondary efficacy endpoints included complete response, minimal residual disease, event-free survival, and overall survival.

At 1 year of follow-up, both primary endpoints were met. There was a significant reduction of allergic reactions in the eryaspase arm compared to the native L-asparaginase arm—0% (0/26) and 42.9% (12/28), respectively (P<0.001).

And there was a significant increase in the duration of circulating asparaginase activity in the eryaspase arm compared to the native L-asparaginase arm. Asparaginase levels were maintained above 100 IU/L for an average of 20.5 days with up to 2 injections during the first month of treatment with eryaspase, compared to 9.2 days in the native L-asparaginase arm, with up to 8 injections of L-asparaginase (P<0.001).

In addition, the complete response rate was higher with eryaspase. At the end of the induction phase, 71.4% of patients (n=15) in the eryaspase arm had a complete response, compared to 42.3% of patients (n=11) in the native L-asparaginase arm.

Finally, the study showed that eryaspase is well-tolerated by patients with previous allergies to L-asparaginase. Two of the 26 patients with prior allergies to L-asparaginase experienced mild allergic reactions to eryaspase.

“The results of this study are an important step forward for the treatment of ALL patients that are at risk to receive L-asparaginase, which remains an important unmet medical need,” said Yves Betrand, MD, of the Institute for Pediatric Hematology and Oncology in Lyon, France.

“The virtual absence of allergic reactions, also in patients with prior allergies to L-asparaginase, is very encouraging.”

The analysis of additional secondary and exploratory endpoints for this study is ongoing. ERYTECH said results will be available later this year and are set to be presented at an upcoming scientific conference.

Based on the results of this and earlier studies of eryaspase, ERYTECH intends to submit its application for European Marketing Authorization in the first half of 2015.

The company also plans to accelerate the product’s development in ALL in the US and to launch phase 2 clinical trials in additional oncology indications with high unmet medical need. A phase 2b study of eryaspase in acute myeloid leukemia is already underway, with more than half of the patients enrolled. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

Eryaspase, a product consisting of L-asparaginase encapsulated in red blood cells, may be safer and more effective than native E coli L-asparaginase, results of a phase 2/3 study suggest.

In patients with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), eryaspase given in combination with chemotherapy produced a higher complete response rate and fewer allergic reactions than native E coli L-asparaginase in combination with chemotherapy.

Eryaspase was also well-tolerated in patients who had previously experienced allergic reactions to L-asparaginase.

ERYTECH Pharma, the company developing eryaspase, recently announced these results from the GRASPIVOTALL trial.

The study included 80 children and adults with relapsed or refractory ALL, who were randomized to 1 of 3 treatment arms.

In the first 2 arms, researchers compared eryaspase to native E coli L-asparaginase, both in combination with standard chemotherapy (COOPRALL), in patients without prior allergies to L-asparaginase. In the third arm, the team evaluated eryaspase for patients who have experienced allergic reactions related to asparaginase in their first-line treatment.