User login

Radioactive Iodine Scintiphotos of a Man With Thyroid Cancer

The contemporary management of differentiated thyroid cancer includes posttreatment monitoring for recurrence or metastasis.1 This monitoring includes clinical, biochemical, and imaging evaluation. Follow-up treatment can then be tailored based on the results of this monitoring.

Our patient was a 61-year-old man with a history of papillary thyroid carcinoma, including lymph node involvement and an extension of the primary focus into skeletal muscle (pT3N1bMX, stage IVa). The patient’s status was posttotal thyroidectomy and radioiodine ablation therapy (196.2 mCi iodine-131) in April 2009. The patient underwent follow-up thyrotropin alpha stimulated whole-body radioiodine surveillance scanning in May 2010.

Images demonstrated residual thyroid tissue/carcinoma regional to the thyroid bed, corresponding to prior posttherapy images. Whole body scintiphotos also demonstrated abnormal iodine localization that raised the possibility of distant bony metastasis in the region of the right hip (see Figures 1A and 1B). Current treatment standards for isolated bony metastases recommend repeated radioactive iodine therapy and potential external beam radiation. Imaging is required for accurate verification.1 This abnormal osseous finding was questionable on initial review, as it was present on the posterior, not anterior, view. The patient was instructed to continue hydration and return for additional delayed scintiphotos for further evaluation.

The patient returned 4 days later for delayed scintiphotos, which again demonstrated abnormal iodine localization near the right hip. However, iodine distribution was different, including now being visible on both the anterior and posterior views (see Figures 2A and 2B on the next page).

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Our Treatment

The patient had no pain in the area and, upon further questioning, reported that he returned wearing the same athletic shorts. Given that radioiodine is excreted in the urine, this atypical distribution was thought to reflect urinary contamination. When images were taken again with the shorts removed, no abnormal radioiodine activity was present (see Figures 2C and 2D). Additional findings with thyrotropin alfa stimulation included increased quantitative thyroglobulin values of 20.2 ng/mL with antithyroglobulin antibody < 20.0 U/mL. Radioiodine ablation therapy using thyrotropin alfa was repeated. Iodine localization also was not present in the hip on posttherapy imaging (not shown).

Despite advances in imaging techniques, radioiodine scanning remains an imperfect science. Artifacts and pitfalls have been identified; in part, these are related to the accumulation of iodide in organs other than the thyroid, such as the nasopharynx and stomach, as well as the apparent accumulation due to excretion in the gut and bladder.2-4 These variations can be divided into ectopic normal thyroid tissue, physiologic accumulation in nonthyroidal tissue, and contamination by physiologic secretions. Recent case reports have confirmed this classification. Abnormal radioiodine uptake has been described in vertebral hemangioma,5 liver abscess6 and hydatid cyst,7 bronchiectasis,8 bronchogenic cyst and mucinous cystadenoma (2 fluid-filled cavities),9 chronic submandibular sialadenitis,10 esophageal diverticulum,11 hiatal hernia,12 appendix,13 indwelling Hickman catheter,14 renal cyst,15 and, similar to this case, contamination of the hair.16

Contaminated clothing is not uncommon; however, a persistent abnormality from contaminated clothing on repeat follow-up is unusual and could easily be misinterpreted.2 It would be valuable for all providers to be aware of the pitfalls of imaging before embarking on an unnecessary and potentially hazardous—not to mention costly—treatment course.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Richard Cacciato, MLIS, Medical Librarian, who assisted in the literature review.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Cooper, DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al; American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19(11):1167-1214.

2. Carlisle MR, Lu C, McDougall IR. The interpretation of 131I scans in the evaluation of thyroid cancer, with an emphasis on false positive findings. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24(6):715-735.

3. Shapiro B, Rufini V, Jarwan A, et al. Artifacts, anatomical and physiological variants, and unrelated diseases that might cause false-positive whole-body 131-I scans in patients with thyroid cancer. Semin Nucl Med. 2000;30(2):115-132.

4. Mitchell G, Pratt BE, Vini L, McCready VR, Harmer CL. False positive 131I whole body scans in thyroid cancer. Br J Radiol. 2000;73(870):627-635.

5. Khan S, Dunn J, Strickland N, Al-Nahhas A. Iodine-123 uptake in vertebral haemangiomas in a patient with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2008;11(1):30-33.

6. Pena Pardo FJ, Crespo de la Jara A, Fernández Morejón FJ, Sureda González M, Forteza Vila J, Brugarolas Masllorens A. Solitary focus in the liver in a thyroid cancer patient after a whole body scan with 131 iodine. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2007;26(5):294-296.

7. Omür O, Ozbek SS, Akgün A, Yazici B, Mutlukoca N, Ozcan Z. False-positive I-131 accumulation in a hepatic hydatid cyst. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32(12):930-932.

8. Jong I, Taubman K, Schlicht S. Bronchiectasis simulating pulmonary metastases on iodine-131 scintigraphy in well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30(10):688-689.

9. Agriantonis DJ, Hall L, Wilson MA. Pitfalls of I-131 whole body scan interpretation: Bronchogenic cyst and mucinous cystadenoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33(5):325-327.

10. Ozguven M, Ilgan S, Karacalioglu AO, Arslan N, Ozturk E. Unusual patterns of I-131 accumulation. Clin Nucl Med. 2004;29(11):738-740.

11. Rashid K, Johns W, Chasse K, Walker M, Gupta SM. Esophageal diverticulum presenting as metastatic thyroid mass on iodine-131 scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31(7):405-408.

12. Ceylan Gunay E, Erdogan A. Mediastinal radioiodine uptake due to hiatal hernia: A false-positive reaction in 131I scan. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2010;29(2):95.

13. Borkar S, Grewal R, Schoder H. I-131 uptake demonstrated in the appendix on a posttreatment scan in a patient with thyroid cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33(8):551-552.

14. Groskin SA, McCrohan G. Pseudometastasis of the chest wall resulting from a Hickman catheter. J Thorac Imaging. 1994;9(3):169-171.

15. Thust S, Fernando R, Barwick T, Mohan H, Clarke SE. SPECT/CT identification of post-radioactive iodine treatment false-positive uptake in a simple renal cyst. Thyroid. 2009;19(1):75-76.

16. Sinha A, Bradley KM, Steatham J, Weaver A. Asymmetric breast uptake of radioiodine in a patient with thyroid malignancy: Metastases or not? J R Soc Med. 2008;101(6):319-320.

The contemporary management of differentiated thyroid cancer includes posttreatment monitoring for recurrence or metastasis.1 This monitoring includes clinical, biochemical, and imaging evaluation. Follow-up treatment can then be tailored based on the results of this monitoring.

Our patient was a 61-year-old man with a history of papillary thyroid carcinoma, including lymph node involvement and an extension of the primary focus into skeletal muscle (pT3N1bMX, stage IVa). The patient’s status was posttotal thyroidectomy and radioiodine ablation therapy (196.2 mCi iodine-131) in April 2009. The patient underwent follow-up thyrotropin alpha stimulated whole-body radioiodine surveillance scanning in May 2010.

Images demonstrated residual thyroid tissue/carcinoma regional to the thyroid bed, corresponding to prior posttherapy images. Whole body scintiphotos also demonstrated abnormal iodine localization that raised the possibility of distant bony metastasis in the region of the right hip (see Figures 1A and 1B). Current treatment standards for isolated bony metastases recommend repeated radioactive iodine therapy and potential external beam radiation. Imaging is required for accurate verification.1 This abnormal osseous finding was questionable on initial review, as it was present on the posterior, not anterior, view. The patient was instructed to continue hydration and return for additional delayed scintiphotos for further evaluation.

The patient returned 4 days later for delayed scintiphotos, which again demonstrated abnormal iodine localization near the right hip. However, iodine distribution was different, including now being visible on both the anterior and posterior views (see Figures 2A and 2B on the next page).

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Our Treatment

The patient had no pain in the area and, upon further questioning, reported that he returned wearing the same athletic shorts. Given that radioiodine is excreted in the urine, this atypical distribution was thought to reflect urinary contamination. When images were taken again with the shorts removed, no abnormal radioiodine activity was present (see Figures 2C and 2D). Additional findings with thyrotropin alfa stimulation included increased quantitative thyroglobulin values of 20.2 ng/mL with antithyroglobulin antibody < 20.0 U/mL. Radioiodine ablation therapy using thyrotropin alfa was repeated. Iodine localization also was not present in the hip on posttherapy imaging (not shown).

Despite advances in imaging techniques, radioiodine scanning remains an imperfect science. Artifacts and pitfalls have been identified; in part, these are related to the accumulation of iodide in organs other than the thyroid, such as the nasopharynx and stomach, as well as the apparent accumulation due to excretion in the gut and bladder.2-4 These variations can be divided into ectopic normal thyroid tissue, physiologic accumulation in nonthyroidal tissue, and contamination by physiologic secretions. Recent case reports have confirmed this classification. Abnormal radioiodine uptake has been described in vertebral hemangioma,5 liver abscess6 and hydatid cyst,7 bronchiectasis,8 bronchogenic cyst and mucinous cystadenoma (2 fluid-filled cavities),9 chronic submandibular sialadenitis,10 esophageal diverticulum,11 hiatal hernia,12 appendix,13 indwelling Hickman catheter,14 renal cyst,15 and, similar to this case, contamination of the hair.16

Contaminated clothing is not uncommon; however, a persistent abnormality from contaminated clothing on repeat follow-up is unusual and could easily be misinterpreted.2 It would be valuable for all providers to be aware of the pitfalls of imaging before embarking on an unnecessary and potentially hazardous—not to mention costly—treatment course.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Richard Cacciato, MLIS, Medical Librarian, who assisted in the literature review.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The contemporary management of differentiated thyroid cancer includes posttreatment monitoring for recurrence or metastasis.1 This monitoring includes clinical, biochemical, and imaging evaluation. Follow-up treatment can then be tailored based on the results of this monitoring.

Our patient was a 61-year-old man with a history of papillary thyroid carcinoma, including lymph node involvement and an extension of the primary focus into skeletal muscle (pT3N1bMX, stage IVa). The patient’s status was posttotal thyroidectomy and radioiodine ablation therapy (196.2 mCi iodine-131) in April 2009. The patient underwent follow-up thyrotropin alpha stimulated whole-body radioiodine surveillance scanning in May 2010.

Images demonstrated residual thyroid tissue/carcinoma regional to the thyroid bed, corresponding to prior posttherapy images. Whole body scintiphotos also demonstrated abnormal iodine localization that raised the possibility of distant bony metastasis in the region of the right hip (see Figures 1A and 1B). Current treatment standards for isolated bony metastases recommend repeated radioactive iodine therapy and potential external beam radiation. Imaging is required for accurate verification.1 This abnormal osseous finding was questionable on initial review, as it was present on the posterior, not anterior, view. The patient was instructed to continue hydration and return for additional delayed scintiphotos for further evaluation.

The patient returned 4 days later for delayed scintiphotos, which again demonstrated abnormal iodine localization near the right hip. However, iodine distribution was different, including now being visible on both the anterior and posterior views (see Figures 2A and 2B on the next page).

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

[Click through to the next page to see the answer.]

Our Treatment

The patient had no pain in the area and, upon further questioning, reported that he returned wearing the same athletic shorts. Given that radioiodine is excreted in the urine, this atypical distribution was thought to reflect urinary contamination. When images were taken again with the shorts removed, no abnormal radioiodine activity was present (see Figures 2C and 2D). Additional findings with thyrotropin alfa stimulation included increased quantitative thyroglobulin values of 20.2 ng/mL with antithyroglobulin antibody < 20.0 U/mL. Radioiodine ablation therapy using thyrotropin alfa was repeated. Iodine localization also was not present in the hip on posttherapy imaging (not shown).

Despite advances in imaging techniques, radioiodine scanning remains an imperfect science. Artifacts and pitfalls have been identified; in part, these are related to the accumulation of iodide in organs other than the thyroid, such as the nasopharynx and stomach, as well as the apparent accumulation due to excretion in the gut and bladder.2-4 These variations can be divided into ectopic normal thyroid tissue, physiologic accumulation in nonthyroidal tissue, and contamination by physiologic secretions. Recent case reports have confirmed this classification. Abnormal radioiodine uptake has been described in vertebral hemangioma,5 liver abscess6 and hydatid cyst,7 bronchiectasis,8 bronchogenic cyst and mucinous cystadenoma (2 fluid-filled cavities),9 chronic submandibular sialadenitis,10 esophageal diverticulum,11 hiatal hernia,12 appendix,13 indwelling Hickman catheter,14 renal cyst,15 and, similar to this case, contamination of the hair.16

Contaminated clothing is not uncommon; however, a persistent abnormality from contaminated clothing on repeat follow-up is unusual and could easily be misinterpreted.2 It would be valuable for all providers to be aware of the pitfalls of imaging before embarking on an unnecessary and potentially hazardous—not to mention costly—treatment course.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Richard Cacciato, MLIS, Medical Librarian, who assisted in the literature review.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Cooper, DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al; American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19(11):1167-1214.

2. Carlisle MR, Lu C, McDougall IR. The interpretation of 131I scans in the evaluation of thyroid cancer, with an emphasis on false positive findings. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24(6):715-735.

3. Shapiro B, Rufini V, Jarwan A, et al. Artifacts, anatomical and physiological variants, and unrelated diseases that might cause false-positive whole-body 131-I scans in patients with thyroid cancer. Semin Nucl Med. 2000;30(2):115-132.

4. Mitchell G, Pratt BE, Vini L, McCready VR, Harmer CL. False positive 131I whole body scans in thyroid cancer. Br J Radiol. 2000;73(870):627-635.

5. Khan S, Dunn J, Strickland N, Al-Nahhas A. Iodine-123 uptake in vertebral haemangiomas in a patient with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2008;11(1):30-33.

6. Pena Pardo FJ, Crespo de la Jara A, Fernández Morejón FJ, Sureda González M, Forteza Vila J, Brugarolas Masllorens A. Solitary focus in the liver in a thyroid cancer patient after a whole body scan with 131 iodine. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2007;26(5):294-296.

7. Omür O, Ozbek SS, Akgün A, Yazici B, Mutlukoca N, Ozcan Z. False-positive I-131 accumulation in a hepatic hydatid cyst. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32(12):930-932.

8. Jong I, Taubman K, Schlicht S. Bronchiectasis simulating pulmonary metastases on iodine-131 scintigraphy in well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30(10):688-689.

9. Agriantonis DJ, Hall L, Wilson MA. Pitfalls of I-131 whole body scan interpretation: Bronchogenic cyst and mucinous cystadenoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33(5):325-327.

10. Ozguven M, Ilgan S, Karacalioglu AO, Arslan N, Ozturk E. Unusual patterns of I-131 accumulation. Clin Nucl Med. 2004;29(11):738-740.

11. Rashid K, Johns W, Chasse K, Walker M, Gupta SM. Esophageal diverticulum presenting as metastatic thyroid mass on iodine-131 scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31(7):405-408.

12. Ceylan Gunay E, Erdogan A. Mediastinal radioiodine uptake due to hiatal hernia: A false-positive reaction in 131I scan. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2010;29(2):95.

13. Borkar S, Grewal R, Schoder H. I-131 uptake demonstrated in the appendix on a posttreatment scan in a patient with thyroid cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33(8):551-552.

14. Groskin SA, McCrohan G. Pseudometastasis of the chest wall resulting from a Hickman catheter. J Thorac Imaging. 1994;9(3):169-171.

15. Thust S, Fernando R, Barwick T, Mohan H, Clarke SE. SPECT/CT identification of post-radioactive iodine treatment false-positive uptake in a simple renal cyst. Thyroid. 2009;19(1):75-76.

16. Sinha A, Bradley KM, Steatham J, Weaver A. Asymmetric breast uptake of radioiodine in a patient with thyroid malignancy: Metastases or not? J R Soc Med. 2008;101(6):319-320.

1. Cooper, DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al; American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19(11):1167-1214.

2. Carlisle MR, Lu C, McDougall IR. The interpretation of 131I scans in the evaluation of thyroid cancer, with an emphasis on false positive findings. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24(6):715-735.

3. Shapiro B, Rufini V, Jarwan A, et al. Artifacts, anatomical and physiological variants, and unrelated diseases that might cause false-positive whole-body 131-I scans in patients with thyroid cancer. Semin Nucl Med. 2000;30(2):115-132.

4. Mitchell G, Pratt BE, Vini L, McCready VR, Harmer CL. False positive 131I whole body scans in thyroid cancer. Br J Radiol. 2000;73(870):627-635.

5. Khan S, Dunn J, Strickland N, Al-Nahhas A. Iodine-123 uptake in vertebral haemangiomas in a patient with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2008;11(1):30-33.

6. Pena Pardo FJ, Crespo de la Jara A, Fernández Morejón FJ, Sureda González M, Forteza Vila J, Brugarolas Masllorens A. Solitary focus in the liver in a thyroid cancer patient after a whole body scan with 131 iodine. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2007;26(5):294-296.

7. Omür O, Ozbek SS, Akgün A, Yazici B, Mutlukoca N, Ozcan Z. False-positive I-131 accumulation in a hepatic hydatid cyst. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32(12):930-932.

8. Jong I, Taubman K, Schlicht S. Bronchiectasis simulating pulmonary metastases on iodine-131 scintigraphy in well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30(10):688-689.

9. Agriantonis DJ, Hall L, Wilson MA. Pitfalls of I-131 whole body scan interpretation: Bronchogenic cyst and mucinous cystadenoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33(5):325-327.

10. Ozguven M, Ilgan S, Karacalioglu AO, Arslan N, Ozturk E. Unusual patterns of I-131 accumulation. Clin Nucl Med. 2004;29(11):738-740.

11. Rashid K, Johns W, Chasse K, Walker M, Gupta SM. Esophageal diverticulum presenting as metastatic thyroid mass on iodine-131 scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31(7):405-408.

12. Ceylan Gunay E, Erdogan A. Mediastinal radioiodine uptake due to hiatal hernia: A false-positive reaction in 131I scan. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2010;29(2):95.

13. Borkar S, Grewal R, Schoder H. I-131 uptake demonstrated in the appendix on a posttreatment scan in a patient with thyroid cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33(8):551-552.

14. Groskin SA, McCrohan G. Pseudometastasis of the chest wall resulting from a Hickman catheter. J Thorac Imaging. 1994;9(3):169-171.

15. Thust S, Fernando R, Barwick T, Mohan H, Clarke SE. SPECT/CT identification of post-radioactive iodine treatment false-positive uptake in a simple renal cyst. Thyroid. 2009;19(1):75-76.

16. Sinha A, Bradley KM, Steatham J, Weaver A. Asymmetric breast uptake of radioiodine in a patient with thyroid malignancy: Metastases or not? J R Soc Med. 2008;101(6):319-320.

Reorganizing a Hospital Ward

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine called for a major redesign of the US healthcare system, describing the chasm between the quality of care Americans receive and the quality of healthcare they deserve.[1] The healthcare community recognizes its ongoing quality and value gaps, but progress has been limited by outdated care models, fragmented organizational structures, and insufficient advances in system design.[2] Many healthcare organizations are searching for new care delivery models capable of producing greater value.

A major constraint in hospitals is the persistence of underperforming frontline clinical care teams.[3] Physicians typically travel from 1 unit or patient to the next in unpredictable patterns, resulting in missed opportunities to share perspectives and coordinate care with nurses, discharge planning personnel, pharmacists, therapists, and patients. This geographic fragmentation almost certainly contributes to interprofessional silos and hierarchies, nonspecific care plans, and failure to initiate or intensify therapy when indicated.[4] Modern hospital units could benefit from having a standard care model that synchronizes frontline professionals into teams routinely coordinating and progressing a shared plan of care.

EFFECTIVE CLINICAL MICROSYSTEMS REFLECTED IN THE DESIGN OF THE ACCOUNTABLE CARE UNIT

High‐value healthcare organizations deliberately design clinical microsystems.[5] An effective clinical microsystem combines several traits: (1) a small group of people who work together in a defined setting on a regular basis to provide care, (2) linked care processes and a shared information environment that includes individuals who receive that care, (3) performance outcomes, and (4) set service and care aims.[6] For the accountable care unit (ACU) to reflect the traits of an effective clinical microsystem, we designed it with analogous features: (1) unit‐based teams, (2) structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR), (3) unit‐level performance reporting, and (4) unit‐level nurse and physician coleadership. We launched the ACU on September 1, 2010 in a high‐acuity 24‐bed medical unit at Emory University Hospital, a 579‐bed tertiary academic medical center. Herein we provide a brief report of our experience implementing and refining the ACU over a 4‐year period to help others gauge feasibility and sustainability.

FEATURES OF AN ACU

Unit‐Based Teams

Design

Geographic alignment fosters mutual respect, cohesiveness, communication, timeliness, and face‐to‐face problem solving,[7, 8] and has been linked to improved patient satisfaction, decreased length of stay, and reductions in morbidity and mortality.[9, 10, 11] At our hospital, though, patients newly admitted or transferred to the hospital medicine service traditionally had been distributed to physician teams without regard to geography, typically based on physician call schedules or traditions of balancing patient volumes across colleagues. These traditional practices geographically dispersed our teams. Physicians would be forced regularly to travel to 5 to 8 different units each day to see 10 to 18 patients. Nurses might perceive this as a parade of different physician teams coming and going off the unit at unpredictable times. To temporally and spatially align physicians with unit‐based staff, specific physician teams were assigned to the ACU.

Implementation

The first step in implementing unit‐based teams was to identify the smallest number of physician teams that could be assigned to the ACU. Two internal medicine resident teams are assigned to care for all medical patients in the unit. Each resident team consists of 1 hospital medicine attending physician, 1 internal medicine resident, 3 interns (2 covering the day shift and 1 overnight every other night), and up to 2 medical students. The 2 teams alternate a 24‐hour call cycle where the on‐call team admits every patient arriving to the unit. For patients arriving to the unit from 6 pm to 7 am, the on‐call overnight intern admits the patients and hands over care to the team in the morning. The on‐call team becomes aware of an incoming patient once the patient has been assigned a bed in the home unit. Several patients per day may arrive on the unit as transfers from a medical or surgical intensive care unit, but most patients arrive as emergency room or direct admissions. On any given day it is acceptable and typical for a team to have several patients off the ACU. No specific changes were made to nurse staffing, with the unit continuing to have 1 nurse unit manager, 1 charge nurse per shift, and a nurse‐to‐patient ratio of 1 to 4.

Results

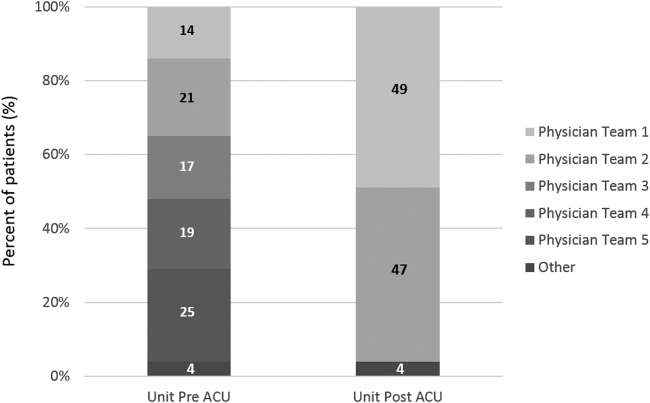

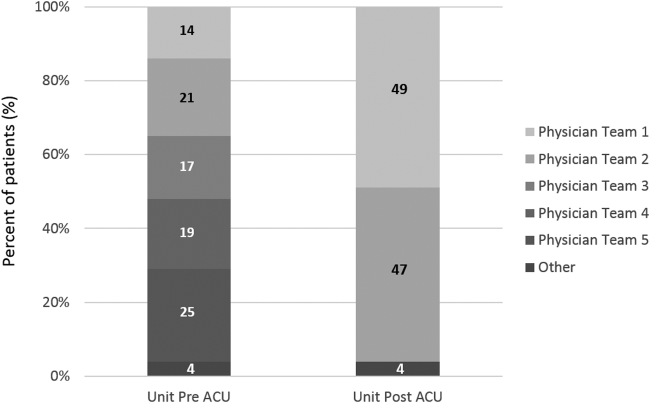

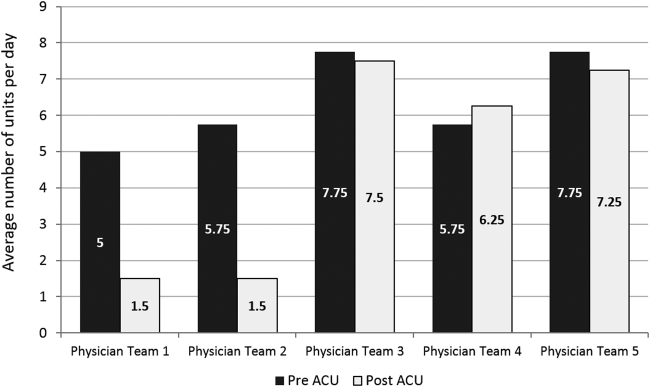

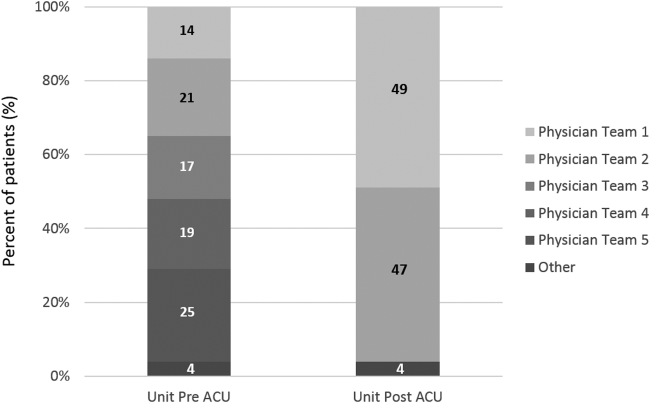

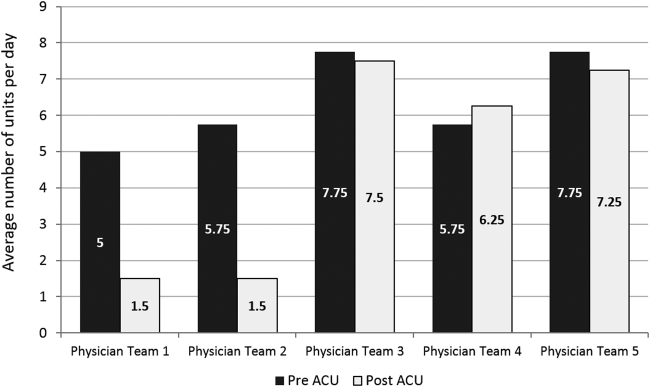

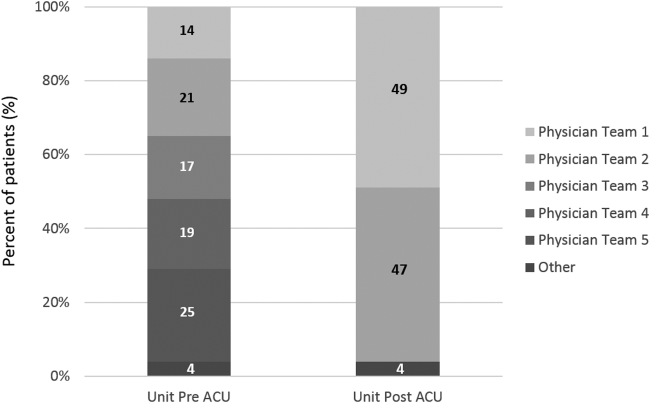

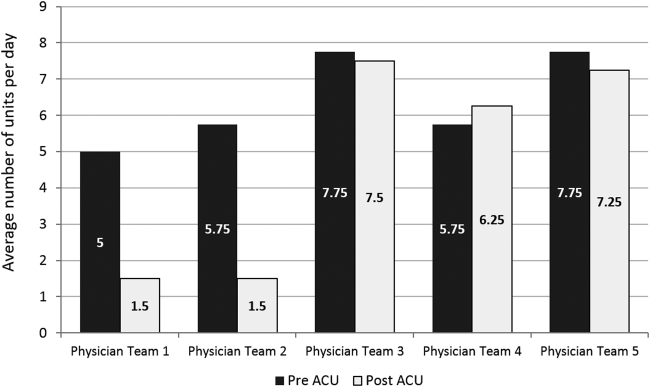

Geographic patient assignment has been successful (Figure 1). Prior to implementing the ACU, more than 5 different hospital medicine physician teams cared for patients on the unit, with no single team caring for more than 25% of them. In the ACU, all medical patients are assigned to 1 of the 2 unit‐based physician teams (physician teams 1 and 2), which regularly represents more than 95% of all patients on the unit. Over the 4 years, these 2 ACU teams have had an average of 12.9 total patient encounters per day (compared to 11.8 in the year before the ACU when these teams were not unit based). The 2 unit‐based teams have over 90% of their patients on the ACU daily. In contrast, 3 attending‐only hospital medicine teams (physician teams 3, 4, and 5) are still dispersed over 6 to 8 units every day (Figure 2), primarily due to high hospital occupancy and a relative scarcity of units eligible to become dedicated hospital medicine units.

Effects of the Change

Through unit‐based teams, the ACU achieves the first trait of an effective clinical microsystem. Although an evaluation of the cultural gains are beyond the scope of this article, the logistical advantages are self‐evident; having the fewest necessary physician teams overseeing care for nearly all patients in 1 unit and where those physician teams simultaneously have nearly all of their patients on that 1 unit, makes it possible to schedule interdisciplinary teamwork activities, such as SIBR, not otherwise feasible.

Structured Interdisciplinary Bedside Rounds

Design

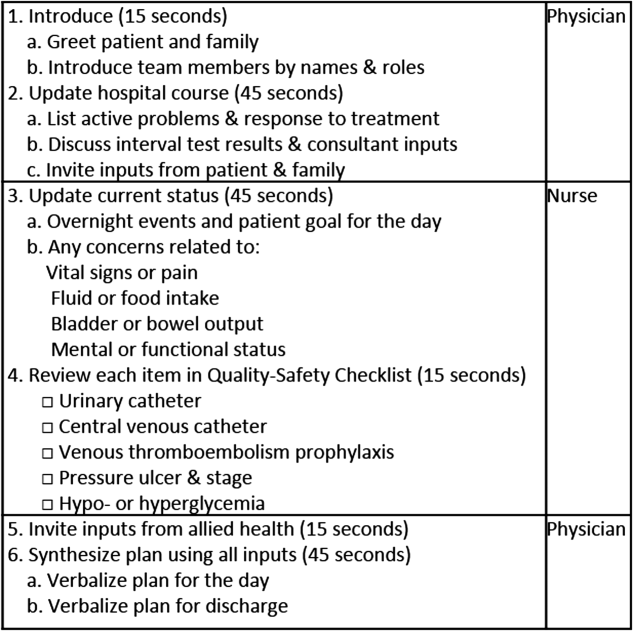

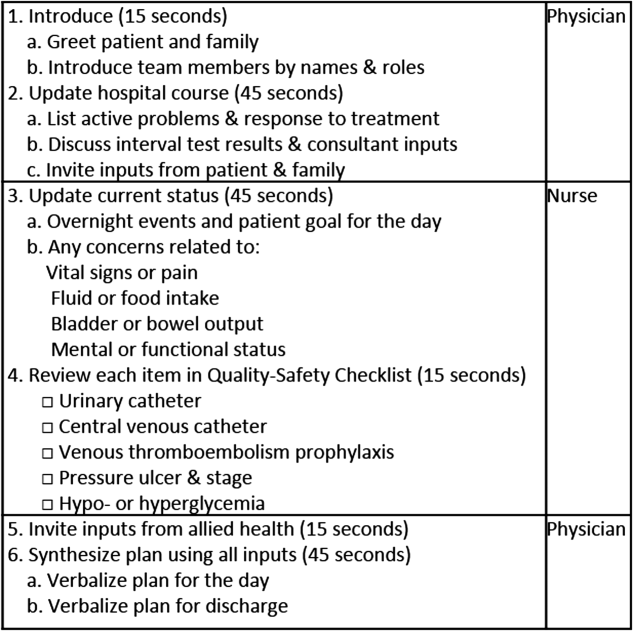

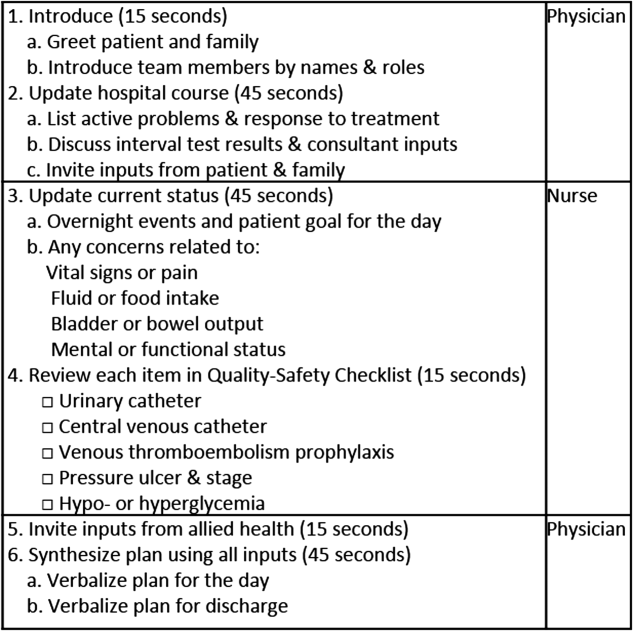

To reflect the second trait of an effective clinical microsystem, a hospital unit should routinely combine best practices for communication, including daily goals sheets,[12] safety checklists,[13] and multidisciplinary rounds.[14, 15] ACU design achieves this through SIBR, a patient‐ and family‐centered, team‐based approach to rounds that brings the nurse, physician, and available allied health professionals to the patient's bedside every day to exchange perspectives using a standard format to cross‐check information with the patient, family, and one another, and articulate a clear plan for the day. Before the SIBR hour starts, physicians and nurses have already performed independent patient assessments through usual activities such as handover, chart review, patient interviews, and physical examinations. Participants in SIBR are expected to give or receive inputs according to the standard SIBR communication protocol (Figure 3), review a quality‐safety checklist together, and ensure the plan of care is verbalized. Including the patient and family allows all parties to hear and be heard, cross‐check information for accuracy, and hold each person accountable for contributions.[16, 17]

Implementation

Each ACU staff member receives orientation to the SIBR communication protocol and is expected to be prepared and punctual for the midmorning start times. The charge nurse serves as the SIBR rounds manager, ensuring physicians waste no time searching for the next nurse and each team's eligible patients are seen in the SIBR hour. For each patient, SIBR begins when the nurse and physician are both present at the bedside. The intern begins SIBR by introducing team members before reviewing the patient's active problem list, response to treatment, and interval test results or consultant inputs. The nurse then relays the patient's goal for the day, overnight events, nursing concerns, and reviews the quality‐safety checklist. The intern then invites allied health professionals to share inputs that might impact medical decision making or discharge planning, before synthesizing all inputs into a shared plan for the day.

Throughout SIBR, the patient and family are encouraged to ask questions or correct misinformation. Although newcomers to SIBR often imagine that inviting patient inputs will disrupt efficiency, we have found teams readily learn to manage this risk, for instance discerning the core question among multiple seemingly disparate ones, or volunteering to return after the SIBR hour to explore a complex issue.

Results

Since the launch of the ACU on September 1, 2010, SIBR has been embedded as a routine on the unit with both physician teams and the nursing staff conducting it every day. Patients not considered eligible for SIBR are those whom the entire physician team has not yet evaluated, typically patients who arrived to the unit overnight. For patients who opt out due to personal preference, or for patients away from the unit for a procedure or a test, SIBR occurs without the patient so the rest of the team can still exchange inputs and formulate a plan of care. A visitor to the unit sees SIBR start punctually at 9 am and 10 am for successive teams, with each completing SIBR on eligible patients in under 60 minutes.

Effects of the Change

The second trait of an effective clinical microsystem is achieved through SIBR's routine forum for staff to share information with each other and the patient. By practicing SIBR every workday, staff are presented with multiple routine opportunities to experience an environment reflective of high‐performing frontline units.[18] We found that SIBR resembled other competencies, with a bell curve of performance. For this reason, by the start of the third year we added a SIBR certification program, a SIBR skills training program where permanent and rotating staff are evaluated through an in vivo observed structured clinical exam, typically with a charge nurse or physician as preceptor. When a nurse, medical student, intern, or resident demonstrates an ability to perform a series of specific high performance SIBR behaviors in 5 of 6 consecutive patients, they can achieve SIBR certification. In the first 2 years of this voluntary certification program, all daytime nursing staff and rotating interns have achieved this demonstration of interdisciplinary teamwork competence.

Unit‐Level Performance Reporting

Design

Hospital outcomes are determined on the clinical frontline. To be effective at managing unit outcomes, performance reports must be made available to unit leadership and staff.[5, 16] However, many hospitals still report performance at the level of the facility or service line. This limits the relevance of reports for the people who directly determine outcomes.

Implementation

For the first year, a data analyst was available to prepare and distribute unit‐level performance reports to unit leaders quarterly, including rates of in‐hospital mortality, blood stream infections, patient satisfaction, length of stay, and 30‐day readmissions. Preparation of these reports was labor intensive, requiring the analyst to acquire raw data from multiple data sources and to build the reports manually.

Results

In an analysis comparing outcomes for every patient spending at least 1 night on the unit in the year before and year after implementation, we observed reductions in in‐hospital mortality and length of stay. Unadjusted in‐hospital mortality decreased from 2.3% to 1.1% (P=0.004), with no change in referrals to hospice (5.4% to 4.5%) (P=0.176), and length‐of‐stay decreased from 5.0 to 4.5 days (P=0.001).[19] A complete report of these findings, including an analysis of concurrent control groups is beyond the scope of this article, but here we highlight an effect we observed on ACU leadership and staff from the reduction in in‐hospital mortality.

Effects of the Change

Noting the apparent mortality reduction, ACU leadership encouraged permanent staff and rotating trainees to consider an unexpected death as a never event. Although perhaps self‐evident, before the ACU we had never been organized to reflect on that concept or to use routines to do something about it. The unit considered an unexpected death one where the patient was not actively receiving comfort measures. At the monthly meet and greet, where ACU leadership bring the permanent staff and new rotating trainees together to introduce themselves by first name, the coleaders proposed that unexpected deaths in the month ahead could represent failures to recognize or respond to deterioration, to consider an alternative or under‐treated process, to transfer the patient to a higher level of care, or to deliver more timely and appropriate end‐of‐life care. It is our impression that this introspection was extraordinarily meaningful and would not have occurred without unit‐based teams, unit‐level performance data, and ACU leadership learning to utilize this rhetoric.

Unit‐Level Nurse and Physician Coleadership

Design

Effective leadership is a major driver of successful clinical microsystems.[20] The ACU is designed to be co‐led by a nurse unit manager and physician medical director. The leadership pair was charged simply with developing patient‐centered teams and ensuring the staff felt connected to the values of the organization and accountable to each other and the outcomes of the unit.

Implementation

Nursing leadership and hospital executives influenced the selection of the physician medical director, which was a way for them to demonstrate support for the care model. Over the first 4 years, the physician medical director position has been afforded a 10% to 20% reduction in clinical duties to fulfill the charge. The leadership pair sets expectations for the ACU's code of conduct, standard operating procedures (eg, SIBR), and best‐practice protocols.

Results

The leadership pair tries explicitly to role model the behaviors enumerated in the ACU's relational covenant, itself the product of a facilitated exercise they commissioned in the first year in which the entire staff drafted and signed a document listing behaviors they wished to see from each other (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). The physician medical director, along with charge nurses, coach staff and trainees wishing to achieve SIBR certification. Over the 4 years, the pair has introduced best‐practice protocols for glycemic control, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, removal of idle venous and bladder catheters, and bedside goals‐of‐care conversations.

Effects of the Change

Where there had previously been no explicit code of conduct, standard operating procedures such as SIBR, or focused efforts to optimize unit outcomes, the coleadership pair fills a management gap. These coleaders play an essential role in building momentum for the structure and processes of the ACU. The leadership pair has also become a primary resource for intraorganizational spread of the ACU model to medical and surgical wards, as well as geriatric, long‐term acute, and intensive care units.

CHALLENGES

Challenges with implementing the ACU fell into 3 primary categories: (1) performing change management required for a successful launch, (2) solving logistics of maintaining unit‐based physician teams, and (3) training physicians and nurses to perform SIBR at a high level.

For change management, the leadership pair was able to explain the rationale of the model to all staff in sufficient detail to launch the ACU. To build momentum for ACU routines and relationships, the physician leader and the nurse unit manager were both present on the unit daily for the first 100 days. As ACU operations became routine and competencies formed among clinicians, the amount of time spent by these leaders was de‐escalated.

Creating and maintaining unit‐based physician teams required shared understanding and coordination between on‐call hospital medicine physicians and the bed control office so that new admissions or transfers could be consistently assigned to unit‐based teams without adversely affecting patient flow. We found this challenge to be manageable once stakeholders accepted the rationale for the care mode and figured out how to support it.

The challenge of building high‐performance SIBR across the unit, including competence of rotating trainees new to the model, requires individualized assessment and feedback necessary for SIBR certification. We addressed this challenge by creating a SIBR train‐the‐trainer programa list of observable high‐performance SIBR behaviors coupled with a short course about giving effective feedback to learnersand found that once the ACU had several nurse and physician SIBR trainers in the staffing mix every day, the required amount of SIBR coaching expertise was available when needed.

CONCLUSION

Improving value and reliability in hospital care may require new models of care. The ACU is a hospital care model specifically designed to organize physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals into high‐functioning, unit‐based teams. It converges standard workflow, patient‐centered communication, quality‐safety checklists, best‐practice protocols, performance measurement, and progressive leadership. Our experience with the ACU suggests that hospital units can be reorganized as effective clinical microsystems where consistent unit professionals can share time and space, a sense of purpose, code of conduct, shared mental model for teamwork, an interprofessional management structure, and an important level of accountability to each other and their patients.

Disclosures: Jason Stein, MD: grant support from the US Health & Resources Services Administration to support organizational implementation of the care model described; recipient of consulting fees and royalties for licensed intellectual property to support implementation of the care model described; founder and president of nonprofit Centripital, provider of consulting services to hospital systems implementing the care model described. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. Liam Chadwick, PhD, and Diaz Clark, MS, RN: recipients of consulting fees through Centripital to support implementation of the care model described. Bryan W. Castle, MBA, RN: grant support from the US Health & Resources Services Administration to support organizational implementation of the care model described; recipient of consulting fees through Centripital to support implementation of the care model described. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

- Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

- , , . The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759–769.

- . The end of the beginning: patient safety five years after “to err is human”. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:W4‐534–545.

- , , , et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825–834.

- . The four habits of high‐value health care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2045–2047.

- , , , . Using a Malcolm Baldrige framework to understand high‐performing clinical microsystems. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(5):334–341.

- , , , . Relational coordination among nurses and other providers: impact on the quality of patient care. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(8):926–937.

- , , , et al. Unit‐based care teams and the frequency and quality of physician‐nurse communications. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(5):424–428.

- , , , et al. Reducing cardiac arrests in the acute admissions unit: a quality improvement journey. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(12):1025–1031.

- , , , et al. Evolving practice of hospital medicine and its impact on hospital throughput and efficiencies. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):649–654.

- , . Improvement projects led by unit‐based teams of nurse, physician, and quality leaders reduce infections, lower costs, improve patient satisfaction, and nurse‐physician communication. AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange. Available at: https://innovations.ahrq.gov/profiles/improvement‐projects‐led‐unit‐based‐teams‐nurse‐physician‐and‐quality‐leaders‐reduce. Accessed May 4, 2014.

- , , , , . The daily goals communication sheet: a simple and novel tool for improved communication and care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(10):608–613, 561.

- , , , et al. Implementation of a mandatory checklist of protocols and objectives improves compliance with a wide range of evidence‐based intensive care unit practices. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2775–2781.

- , , , et al. Structured interdisciplinary rounds in a medical teaching unit: improving patient safety. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):678–684.

- , , , , , . Improving teamwork: impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a hospitalist unit. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):88–93.

- , , . Integrating patient safety into the clinical microsystem. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(suppl 2):ii34–ii38.

- , , , . Collaborative‐cross checking to enhance resilience. Cogn Tech Work. 2007;9:155–162.

- , , , et al. Microsystems in health care: Part 1. Learning from high‐performing front‐line clinical units. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28(9):472–493.

- , , . Mortality reduction associated with structure process, and management redesign of a hospital medicine unit. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(suppl 2):115.

- , , , et al. Microsystems in health care: part 5. How leaders are leading. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29(6):297–308.

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine called for a major redesign of the US healthcare system, describing the chasm between the quality of care Americans receive and the quality of healthcare they deserve.[1] The healthcare community recognizes its ongoing quality and value gaps, but progress has been limited by outdated care models, fragmented organizational structures, and insufficient advances in system design.[2] Many healthcare organizations are searching for new care delivery models capable of producing greater value.

A major constraint in hospitals is the persistence of underperforming frontline clinical care teams.[3] Physicians typically travel from 1 unit or patient to the next in unpredictable patterns, resulting in missed opportunities to share perspectives and coordinate care with nurses, discharge planning personnel, pharmacists, therapists, and patients. This geographic fragmentation almost certainly contributes to interprofessional silos and hierarchies, nonspecific care plans, and failure to initiate or intensify therapy when indicated.[4] Modern hospital units could benefit from having a standard care model that synchronizes frontline professionals into teams routinely coordinating and progressing a shared plan of care.

EFFECTIVE CLINICAL MICROSYSTEMS REFLECTED IN THE DESIGN OF THE ACCOUNTABLE CARE UNIT

High‐value healthcare organizations deliberately design clinical microsystems.[5] An effective clinical microsystem combines several traits: (1) a small group of people who work together in a defined setting on a regular basis to provide care, (2) linked care processes and a shared information environment that includes individuals who receive that care, (3) performance outcomes, and (4) set service and care aims.[6] For the accountable care unit (ACU) to reflect the traits of an effective clinical microsystem, we designed it with analogous features: (1) unit‐based teams, (2) structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR), (3) unit‐level performance reporting, and (4) unit‐level nurse and physician coleadership. We launched the ACU on September 1, 2010 in a high‐acuity 24‐bed medical unit at Emory University Hospital, a 579‐bed tertiary academic medical center. Herein we provide a brief report of our experience implementing and refining the ACU over a 4‐year period to help others gauge feasibility and sustainability.

FEATURES OF AN ACU

Unit‐Based Teams

Design

Geographic alignment fosters mutual respect, cohesiveness, communication, timeliness, and face‐to‐face problem solving,[7, 8] and has been linked to improved patient satisfaction, decreased length of stay, and reductions in morbidity and mortality.[9, 10, 11] At our hospital, though, patients newly admitted or transferred to the hospital medicine service traditionally had been distributed to physician teams without regard to geography, typically based on physician call schedules or traditions of balancing patient volumes across colleagues. These traditional practices geographically dispersed our teams. Physicians would be forced regularly to travel to 5 to 8 different units each day to see 10 to 18 patients. Nurses might perceive this as a parade of different physician teams coming and going off the unit at unpredictable times. To temporally and spatially align physicians with unit‐based staff, specific physician teams were assigned to the ACU.

Implementation

The first step in implementing unit‐based teams was to identify the smallest number of physician teams that could be assigned to the ACU. Two internal medicine resident teams are assigned to care for all medical patients in the unit. Each resident team consists of 1 hospital medicine attending physician, 1 internal medicine resident, 3 interns (2 covering the day shift and 1 overnight every other night), and up to 2 medical students. The 2 teams alternate a 24‐hour call cycle where the on‐call team admits every patient arriving to the unit. For patients arriving to the unit from 6 pm to 7 am, the on‐call overnight intern admits the patients and hands over care to the team in the morning. The on‐call team becomes aware of an incoming patient once the patient has been assigned a bed in the home unit. Several patients per day may arrive on the unit as transfers from a medical or surgical intensive care unit, but most patients arrive as emergency room or direct admissions. On any given day it is acceptable and typical for a team to have several patients off the ACU. No specific changes were made to nurse staffing, with the unit continuing to have 1 nurse unit manager, 1 charge nurse per shift, and a nurse‐to‐patient ratio of 1 to 4.

Results

Geographic patient assignment has been successful (Figure 1). Prior to implementing the ACU, more than 5 different hospital medicine physician teams cared for patients on the unit, with no single team caring for more than 25% of them. In the ACU, all medical patients are assigned to 1 of the 2 unit‐based physician teams (physician teams 1 and 2), which regularly represents more than 95% of all patients on the unit. Over the 4 years, these 2 ACU teams have had an average of 12.9 total patient encounters per day (compared to 11.8 in the year before the ACU when these teams were not unit based). The 2 unit‐based teams have over 90% of their patients on the ACU daily. In contrast, 3 attending‐only hospital medicine teams (physician teams 3, 4, and 5) are still dispersed over 6 to 8 units every day (Figure 2), primarily due to high hospital occupancy and a relative scarcity of units eligible to become dedicated hospital medicine units.

Effects of the Change

Through unit‐based teams, the ACU achieves the first trait of an effective clinical microsystem. Although an evaluation of the cultural gains are beyond the scope of this article, the logistical advantages are self‐evident; having the fewest necessary physician teams overseeing care for nearly all patients in 1 unit and where those physician teams simultaneously have nearly all of their patients on that 1 unit, makes it possible to schedule interdisciplinary teamwork activities, such as SIBR, not otherwise feasible.

Structured Interdisciplinary Bedside Rounds

Design

To reflect the second trait of an effective clinical microsystem, a hospital unit should routinely combine best practices for communication, including daily goals sheets,[12] safety checklists,[13] and multidisciplinary rounds.[14, 15] ACU design achieves this through SIBR, a patient‐ and family‐centered, team‐based approach to rounds that brings the nurse, physician, and available allied health professionals to the patient's bedside every day to exchange perspectives using a standard format to cross‐check information with the patient, family, and one another, and articulate a clear plan for the day. Before the SIBR hour starts, physicians and nurses have already performed independent patient assessments through usual activities such as handover, chart review, patient interviews, and physical examinations. Participants in SIBR are expected to give or receive inputs according to the standard SIBR communication protocol (Figure 3), review a quality‐safety checklist together, and ensure the plan of care is verbalized. Including the patient and family allows all parties to hear and be heard, cross‐check information for accuracy, and hold each person accountable for contributions.[16, 17]

Implementation

Each ACU staff member receives orientation to the SIBR communication protocol and is expected to be prepared and punctual for the midmorning start times. The charge nurse serves as the SIBR rounds manager, ensuring physicians waste no time searching for the next nurse and each team's eligible patients are seen in the SIBR hour. For each patient, SIBR begins when the nurse and physician are both present at the bedside. The intern begins SIBR by introducing team members before reviewing the patient's active problem list, response to treatment, and interval test results or consultant inputs. The nurse then relays the patient's goal for the day, overnight events, nursing concerns, and reviews the quality‐safety checklist. The intern then invites allied health professionals to share inputs that might impact medical decision making or discharge planning, before synthesizing all inputs into a shared plan for the day.

Throughout SIBR, the patient and family are encouraged to ask questions or correct misinformation. Although newcomers to SIBR often imagine that inviting patient inputs will disrupt efficiency, we have found teams readily learn to manage this risk, for instance discerning the core question among multiple seemingly disparate ones, or volunteering to return after the SIBR hour to explore a complex issue.

Results

Since the launch of the ACU on September 1, 2010, SIBR has been embedded as a routine on the unit with both physician teams and the nursing staff conducting it every day. Patients not considered eligible for SIBR are those whom the entire physician team has not yet evaluated, typically patients who arrived to the unit overnight. For patients who opt out due to personal preference, or for patients away from the unit for a procedure or a test, SIBR occurs without the patient so the rest of the team can still exchange inputs and formulate a plan of care. A visitor to the unit sees SIBR start punctually at 9 am and 10 am for successive teams, with each completing SIBR on eligible patients in under 60 minutes.

Effects of the Change

The second trait of an effective clinical microsystem is achieved through SIBR's routine forum for staff to share information with each other and the patient. By practicing SIBR every workday, staff are presented with multiple routine opportunities to experience an environment reflective of high‐performing frontline units.[18] We found that SIBR resembled other competencies, with a bell curve of performance. For this reason, by the start of the third year we added a SIBR certification program, a SIBR skills training program where permanent and rotating staff are evaluated through an in vivo observed structured clinical exam, typically with a charge nurse or physician as preceptor. When a nurse, medical student, intern, or resident demonstrates an ability to perform a series of specific high performance SIBR behaviors in 5 of 6 consecutive patients, they can achieve SIBR certification. In the first 2 years of this voluntary certification program, all daytime nursing staff and rotating interns have achieved this demonstration of interdisciplinary teamwork competence.

Unit‐Level Performance Reporting

Design

Hospital outcomes are determined on the clinical frontline. To be effective at managing unit outcomes, performance reports must be made available to unit leadership and staff.[5, 16] However, many hospitals still report performance at the level of the facility or service line. This limits the relevance of reports for the people who directly determine outcomes.

Implementation

For the first year, a data analyst was available to prepare and distribute unit‐level performance reports to unit leaders quarterly, including rates of in‐hospital mortality, blood stream infections, patient satisfaction, length of stay, and 30‐day readmissions. Preparation of these reports was labor intensive, requiring the analyst to acquire raw data from multiple data sources and to build the reports manually.

Results

In an analysis comparing outcomes for every patient spending at least 1 night on the unit in the year before and year after implementation, we observed reductions in in‐hospital mortality and length of stay. Unadjusted in‐hospital mortality decreased from 2.3% to 1.1% (P=0.004), with no change in referrals to hospice (5.4% to 4.5%) (P=0.176), and length‐of‐stay decreased from 5.0 to 4.5 days (P=0.001).[19] A complete report of these findings, including an analysis of concurrent control groups is beyond the scope of this article, but here we highlight an effect we observed on ACU leadership and staff from the reduction in in‐hospital mortality.

Effects of the Change

Noting the apparent mortality reduction, ACU leadership encouraged permanent staff and rotating trainees to consider an unexpected death as a never event. Although perhaps self‐evident, before the ACU we had never been organized to reflect on that concept or to use routines to do something about it. The unit considered an unexpected death one where the patient was not actively receiving comfort measures. At the monthly meet and greet, where ACU leadership bring the permanent staff and new rotating trainees together to introduce themselves by first name, the coleaders proposed that unexpected deaths in the month ahead could represent failures to recognize or respond to deterioration, to consider an alternative or under‐treated process, to transfer the patient to a higher level of care, or to deliver more timely and appropriate end‐of‐life care. It is our impression that this introspection was extraordinarily meaningful and would not have occurred without unit‐based teams, unit‐level performance data, and ACU leadership learning to utilize this rhetoric.

Unit‐Level Nurse and Physician Coleadership

Design

Effective leadership is a major driver of successful clinical microsystems.[20] The ACU is designed to be co‐led by a nurse unit manager and physician medical director. The leadership pair was charged simply with developing patient‐centered teams and ensuring the staff felt connected to the values of the organization and accountable to each other and the outcomes of the unit.

Implementation

Nursing leadership and hospital executives influenced the selection of the physician medical director, which was a way for them to demonstrate support for the care model. Over the first 4 years, the physician medical director position has been afforded a 10% to 20% reduction in clinical duties to fulfill the charge. The leadership pair sets expectations for the ACU's code of conduct, standard operating procedures (eg, SIBR), and best‐practice protocols.

Results

The leadership pair tries explicitly to role model the behaviors enumerated in the ACU's relational covenant, itself the product of a facilitated exercise they commissioned in the first year in which the entire staff drafted and signed a document listing behaviors they wished to see from each other (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). The physician medical director, along with charge nurses, coach staff and trainees wishing to achieve SIBR certification. Over the 4 years, the pair has introduced best‐practice protocols for glycemic control, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, removal of idle venous and bladder catheters, and bedside goals‐of‐care conversations.

Effects of the Change

Where there had previously been no explicit code of conduct, standard operating procedures such as SIBR, or focused efforts to optimize unit outcomes, the coleadership pair fills a management gap. These coleaders play an essential role in building momentum for the structure and processes of the ACU. The leadership pair has also become a primary resource for intraorganizational spread of the ACU model to medical and surgical wards, as well as geriatric, long‐term acute, and intensive care units.

CHALLENGES

Challenges with implementing the ACU fell into 3 primary categories: (1) performing change management required for a successful launch, (2) solving logistics of maintaining unit‐based physician teams, and (3) training physicians and nurses to perform SIBR at a high level.

For change management, the leadership pair was able to explain the rationale of the model to all staff in sufficient detail to launch the ACU. To build momentum for ACU routines and relationships, the physician leader and the nurse unit manager were both present on the unit daily for the first 100 days. As ACU operations became routine and competencies formed among clinicians, the amount of time spent by these leaders was de‐escalated.

Creating and maintaining unit‐based physician teams required shared understanding and coordination between on‐call hospital medicine physicians and the bed control office so that new admissions or transfers could be consistently assigned to unit‐based teams without adversely affecting patient flow. We found this challenge to be manageable once stakeholders accepted the rationale for the care mode and figured out how to support it.

The challenge of building high‐performance SIBR across the unit, including competence of rotating trainees new to the model, requires individualized assessment and feedback necessary for SIBR certification. We addressed this challenge by creating a SIBR train‐the‐trainer programa list of observable high‐performance SIBR behaviors coupled with a short course about giving effective feedback to learnersand found that once the ACU had several nurse and physician SIBR trainers in the staffing mix every day, the required amount of SIBR coaching expertise was available when needed.

CONCLUSION

Improving value and reliability in hospital care may require new models of care. The ACU is a hospital care model specifically designed to organize physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals into high‐functioning, unit‐based teams. It converges standard workflow, patient‐centered communication, quality‐safety checklists, best‐practice protocols, performance measurement, and progressive leadership. Our experience with the ACU suggests that hospital units can be reorganized as effective clinical microsystems where consistent unit professionals can share time and space, a sense of purpose, code of conduct, shared mental model for teamwork, an interprofessional management structure, and an important level of accountability to each other and their patients.

Disclosures: Jason Stein, MD: grant support from the US Health & Resources Services Administration to support organizational implementation of the care model described; recipient of consulting fees and royalties for licensed intellectual property to support implementation of the care model described; founder and president of nonprofit Centripital, provider of consulting services to hospital systems implementing the care model described. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. Liam Chadwick, PhD, and Diaz Clark, MS, RN: recipients of consulting fees through Centripital to support implementation of the care model described. Bryan W. Castle, MBA, RN: grant support from the US Health & Resources Services Administration to support organizational implementation of the care model described; recipient of consulting fees through Centripital to support implementation of the care model described. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine called for a major redesign of the US healthcare system, describing the chasm between the quality of care Americans receive and the quality of healthcare they deserve.[1] The healthcare community recognizes its ongoing quality and value gaps, but progress has been limited by outdated care models, fragmented organizational structures, and insufficient advances in system design.[2] Many healthcare organizations are searching for new care delivery models capable of producing greater value.

A major constraint in hospitals is the persistence of underperforming frontline clinical care teams.[3] Physicians typically travel from 1 unit or patient to the next in unpredictable patterns, resulting in missed opportunities to share perspectives and coordinate care with nurses, discharge planning personnel, pharmacists, therapists, and patients. This geographic fragmentation almost certainly contributes to interprofessional silos and hierarchies, nonspecific care plans, and failure to initiate or intensify therapy when indicated.[4] Modern hospital units could benefit from having a standard care model that synchronizes frontline professionals into teams routinely coordinating and progressing a shared plan of care.

EFFECTIVE CLINICAL MICROSYSTEMS REFLECTED IN THE DESIGN OF THE ACCOUNTABLE CARE UNIT

High‐value healthcare organizations deliberately design clinical microsystems.[5] An effective clinical microsystem combines several traits: (1) a small group of people who work together in a defined setting on a regular basis to provide care, (2) linked care processes and a shared information environment that includes individuals who receive that care, (3) performance outcomes, and (4) set service and care aims.[6] For the accountable care unit (ACU) to reflect the traits of an effective clinical microsystem, we designed it with analogous features: (1) unit‐based teams, (2) structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR), (3) unit‐level performance reporting, and (4) unit‐level nurse and physician coleadership. We launched the ACU on September 1, 2010 in a high‐acuity 24‐bed medical unit at Emory University Hospital, a 579‐bed tertiary academic medical center. Herein we provide a brief report of our experience implementing and refining the ACU over a 4‐year period to help others gauge feasibility and sustainability.

FEATURES OF AN ACU

Unit‐Based Teams

Design

Geographic alignment fosters mutual respect, cohesiveness, communication, timeliness, and face‐to‐face problem solving,[7, 8] and has been linked to improved patient satisfaction, decreased length of stay, and reductions in morbidity and mortality.[9, 10, 11] At our hospital, though, patients newly admitted or transferred to the hospital medicine service traditionally had been distributed to physician teams without regard to geography, typically based on physician call schedules or traditions of balancing patient volumes across colleagues. These traditional practices geographically dispersed our teams. Physicians would be forced regularly to travel to 5 to 8 different units each day to see 10 to 18 patients. Nurses might perceive this as a parade of different physician teams coming and going off the unit at unpredictable times. To temporally and spatially align physicians with unit‐based staff, specific physician teams were assigned to the ACU.

Implementation

The first step in implementing unit‐based teams was to identify the smallest number of physician teams that could be assigned to the ACU. Two internal medicine resident teams are assigned to care for all medical patients in the unit. Each resident team consists of 1 hospital medicine attending physician, 1 internal medicine resident, 3 interns (2 covering the day shift and 1 overnight every other night), and up to 2 medical students. The 2 teams alternate a 24‐hour call cycle where the on‐call team admits every patient arriving to the unit. For patients arriving to the unit from 6 pm to 7 am, the on‐call overnight intern admits the patients and hands over care to the team in the morning. The on‐call team becomes aware of an incoming patient once the patient has been assigned a bed in the home unit. Several patients per day may arrive on the unit as transfers from a medical or surgical intensive care unit, but most patients arrive as emergency room or direct admissions. On any given day it is acceptable and typical for a team to have several patients off the ACU. No specific changes were made to nurse staffing, with the unit continuing to have 1 nurse unit manager, 1 charge nurse per shift, and a nurse‐to‐patient ratio of 1 to 4.

Results

Geographic patient assignment has been successful (Figure 1). Prior to implementing the ACU, more than 5 different hospital medicine physician teams cared for patients on the unit, with no single team caring for more than 25% of them. In the ACU, all medical patients are assigned to 1 of the 2 unit‐based physician teams (physician teams 1 and 2), which regularly represents more than 95% of all patients on the unit. Over the 4 years, these 2 ACU teams have had an average of 12.9 total patient encounters per day (compared to 11.8 in the year before the ACU when these teams were not unit based). The 2 unit‐based teams have over 90% of their patients on the ACU daily. In contrast, 3 attending‐only hospital medicine teams (physician teams 3, 4, and 5) are still dispersed over 6 to 8 units every day (Figure 2), primarily due to high hospital occupancy and a relative scarcity of units eligible to become dedicated hospital medicine units.

Effects of the Change

Through unit‐based teams, the ACU achieves the first trait of an effective clinical microsystem. Although an evaluation of the cultural gains are beyond the scope of this article, the logistical advantages are self‐evident; having the fewest necessary physician teams overseeing care for nearly all patients in 1 unit and where those physician teams simultaneously have nearly all of their patients on that 1 unit, makes it possible to schedule interdisciplinary teamwork activities, such as SIBR, not otherwise feasible.

Structured Interdisciplinary Bedside Rounds

Design

To reflect the second trait of an effective clinical microsystem, a hospital unit should routinely combine best practices for communication, including daily goals sheets,[12] safety checklists,[13] and multidisciplinary rounds.[14, 15] ACU design achieves this through SIBR, a patient‐ and family‐centered, team‐based approach to rounds that brings the nurse, physician, and available allied health professionals to the patient's bedside every day to exchange perspectives using a standard format to cross‐check information with the patient, family, and one another, and articulate a clear plan for the day. Before the SIBR hour starts, physicians and nurses have already performed independent patient assessments through usual activities such as handover, chart review, patient interviews, and physical examinations. Participants in SIBR are expected to give or receive inputs according to the standard SIBR communication protocol (Figure 3), review a quality‐safety checklist together, and ensure the plan of care is verbalized. Including the patient and family allows all parties to hear and be heard, cross‐check information for accuracy, and hold each person accountable for contributions.[16, 17]

Implementation

Each ACU staff member receives orientation to the SIBR communication protocol and is expected to be prepared and punctual for the midmorning start times. The charge nurse serves as the SIBR rounds manager, ensuring physicians waste no time searching for the next nurse and each team's eligible patients are seen in the SIBR hour. For each patient, SIBR begins when the nurse and physician are both present at the bedside. The intern begins SIBR by introducing team members before reviewing the patient's active problem list, response to treatment, and interval test results or consultant inputs. The nurse then relays the patient's goal for the day, overnight events, nursing concerns, and reviews the quality‐safety checklist. The intern then invites allied health professionals to share inputs that might impact medical decision making or discharge planning, before synthesizing all inputs into a shared plan for the day.

Throughout SIBR, the patient and family are encouraged to ask questions or correct misinformation. Although newcomers to SIBR often imagine that inviting patient inputs will disrupt efficiency, we have found teams readily learn to manage this risk, for instance discerning the core question among multiple seemingly disparate ones, or volunteering to return after the SIBR hour to explore a complex issue.

Results

Since the launch of the ACU on September 1, 2010, SIBR has been embedded as a routine on the unit with both physician teams and the nursing staff conducting it every day. Patients not considered eligible for SIBR are those whom the entire physician team has not yet evaluated, typically patients who arrived to the unit overnight. For patients who opt out due to personal preference, or for patients away from the unit for a procedure or a test, SIBR occurs without the patient so the rest of the team can still exchange inputs and formulate a plan of care. A visitor to the unit sees SIBR start punctually at 9 am and 10 am for successive teams, with each completing SIBR on eligible patients in under 60 minutes.

Effects of the Change

The second trait of an effective clinical microsystem is achieved through SIBR's routine forum for staff to share information with each other and the patient. By practicing SIBR every workday, staff are presented with multiple routine opportunities to experience an environment reflective of high‐performing frontline units.[18] We found that SIBR resembled other competencies, with a bell curve of performance. For this reason, by the start of the third year we added a SIBR certification program, a SIBR skills training program where permanent and rotating staff are evaluated through an in vivo observed structured clinical exam, typically with a charge nurse or physician as preceptor. When a nurse, medical student, intern, or resident demonstrates an ability to perform a series of specific high performance SIBR behaviors in 5 of 6 consecutive patients, they can achieve SIBR certification. In the first 2 years of this voluntary certification program, all daytime nursing staff and rotating interns have achieved this demonstration of interdisciplinary teamwork competence.

Unit‐Level Performance Reporting

Design

Hospital outcomes are determined on the clinical frontline. To be effective at managing unit outcomes, performance reports must be made available to unit leadership and staff.[5, 16] However, many hospitals still report performance at the level of the facility or service line. This limits the relevance of reports for the people who directly determine outcomes.

Implementation

For the first year, a data analyst was available to prepare and distribute unit‐level performance reports to unit leaders quarterly, including rates of in‐hospital mortality, blood stream infections, patient satisfaction, length of stay, and 30‐day readmissions. Preparation of these reports was labor intensive, requiring the analyst to acquire raw data from multiple data sources and to build the reports manually.

Results

In an analysis comparing outcomes for every patient spending at least 1 night on the unit in the year before and year after implementation, we observed reductions in in‐hospital mortality and length of stay. Unadjusted in‐hospital mortality decreased from 2.3% to 1.1% (P=0.004), with no change in referrals to hospice (5.4% to 4.5%) (P=0.176), and length‐of‐stay decreased from 5.0 to 4.5 days (P=0.001).[19] A complete report of these findings, including an analysis of concurrent control groups is beyond the scope of this article, but here we highlight an effect we observed on ACU leadership and staff from the reduction in in‐hospital mortality.

Effects of the Change

Noting the apparent mortality reduction, ACU leadership encouraged permanent staff and rotating trainees to consider an unexpected death as a never event. Although perhaps self‐evident, before the ACU we had never been organized to reflect on that concept or to use routines to do something about it. The unit considered an unexpected death one where the patient was not actively receiving comfort measures. At the monthly meet and greet, where ACU leadership bring the permanent staff and new rotating trainees together to introduce themselves by first name, the coleaders proposed that unexpected deaths in the month ahead could represent failures to recognize or respond to deterioration, to consider an alternative or under‐treated process, to transfer the patient to a higher level of care, or to deliver more timely and appropriate end‐of‐life care. It is our impression that this introspection was extraordinarily meaningful and would not have occurred without unit‐based teams, unit‐level performance data, and ACU leadership learning to utilize this rhetoric.

Unit‐Level Nurse and Physician Coleadership

Design

Effective leadership is a major driver of successful clinical microsystems.[20] The ACU is designed to be co‐led by a nurse unit manager and physician medical director. The leadership pair was charged simply with developing patient‐centered teams and ensuring the staff felt connected to the values of the organization and accountable to each other and the outcomes of the unit.

Implementation

Nursing leadership and hospital executives influenced the selection of the physician medical director, which was a way for them to demonstrate support for the care model. Over the first 4 years, the physician medical director position has been afforded a 10% to 20% reduction in clinical duties to fulfill the charge. The leadership pair sets expectations for the ACU's code of conduct, standard operating procedures (eg, SIBR), and best‐practice protocols.

Results

The leadership pair tries explicitly to role model the behaviors enumerated in the ACU's relational covenant, itself the product of a facilitated exercise they commissioned in the first year in which the entire staff drafted and signed a document listing behaviors they wished to see from each other (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). The physician medical director, along with charge nurses, coach staff and trainees wishing to achieve SIBR certification. Over the 4 years, the pair has introduced best‐practice protocols for glycemic control, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, removal of idle venous and bladder catheters, and bedside goals‐of‐care conversations.

Effects of the Change