User login

Prescriber’s guide to using 3 new antidepressants: Vilazodone, levomilnacipran, vortioxetine

With a prevalence >17%, depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the United States and the second leading cause of disability worldwide.1,2 For decades, primary care and mental health providers have used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as first-line treatment for depression—yet the remission rate after the first trial of an antidepressant is <30%, and continues to decline after a first antidepressant failure.3

That is why clinicians continue to seek effective treatments for depression—ones that will provide quick and sustainable remission—and why scientists and pharmaceutical manufacturers have been competing to develop more effective antidepressant medications.

In the past 4 years, the FDA has approved 3 antidepressants—vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine—with the hope of increasing options for patients who suffer from major depression. These 3 antidepressants differ in their mechanisms of action from other available antidepressants, and all have been shown to have acceptable safety and tolerability profiles.

In this article, we review these novel antidepressants and present some clinical pearls for their use. We also present our observations that each agent appears to show particular advantage in a certain subpopulation of depressed patients who often do not respond, or who do not adequately respond, to other antidepressants.

Vilazodone

Vilazodone was approved by the FDA in 2011 (Table 1). The drug increases serotonin bioavailability in synapses through a strong dual action:

• blocking serotonin reuptake through the serotonin transporter

• partial agonism of the 5-HT1A presynaptic receptor.

Vilazodone also has a moderate effect on the 5-HT4 receptor and on dopamine and norepinephrine uptake inhibition.

The unique presynaptic 5-HT1A partial agonism of vilazodone is similar to that of buspirone, in which both drugs initially inhibit serotonin synthesis and neuronal firing.4 Researchers therefore expected that vilazodone would be more suitable for patients who have depression and a comorbid anxiety disorder; current FDA approval, however, is for depression only.

Adverse effects. The 5-HT4 receptor on which vilazodone acts is present in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and contributes to regulating symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)5; not surprisingly, the most frequent adverse effects of vilazodone are GI in nature (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting).

Headache is the most common non- GI side effect of vilazodone. Depressed patients who took vilazodone had no significant weight gain and did not report adverse sexual effects, compared with subjects given placebo.6

The following case—a patient with depression, significant anxiety, and IBS— exemplifies the type of patient for whom we find vilazodone most useful.

CASE Ms. A, age 19, is a college student with a history of major depressive disorder, social anxiety, and panic attacks for 2 years and IBS for 3 years. She was taking lubiprostone for IBS, with incomplete relief of GI symptoms. Because the family history included depression in Ms. A’s mother and sister, and both were doing well on escitalopram, we began a trial of that drug, 10 mg/d, that was quickly titrated to 20 mg/d.

Ms. A did not respond to 20 mg of escitalopram combined with psychotherapy.

We then started vilazodone, 10 mg/d after breakfast, for the first week, and reduced escitalopram to 10 mg/d. During Week 2, escitalopram was discontinued and vilazodone was increased to 20 mg/d. During Week 3, vilazodone was titrated to 40 mg/d.

Ms. A tolerated vilazodone well. Her depressive symptoms improved at the end of Week 2.

Unlike her experience with escitalopram, Ms. A’s anxiety symptoms—tenseness, racing thoughts, and panic attacks—all diminished when she switched to vilazodone. Notably, her IBS symptoms also were relieved, and she discontinued lubiprostone.

Ms. A’s depression remained in remission for 2 years, except for a brief period one summer, when she thought she “could do without any medication.” She tapered the vilazodone, week by week, to 10 mg/d, but her anxiety and bowel symptoms resurfaced to a degree that she resumed the 40-mg/d dosage.

Levomilnacipran

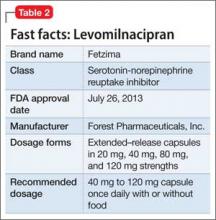

This drug is a 2013 addition to the small serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) family of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, and duloxetine7 (Table 2). Levomilnacipran is the enantiomer of milnacipran, approved in Europe for depression but only for fibromyalgia pain and peripheral neuropathy in the United States.8 (Levomilnacipran is not FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia pain.)

Levomilnacipran is unique because it is more of an NSRI, so to speak, than an SNRI: That is, the drug’s uptake inhibition of norepinephrine is more potent than its serotonin inhibition. Theoretically, levomilnacipran should help improve cognitive functions linked to the action of norepinephrine, such as concentration and motivation, and in turn, improve social function. The FDA also has approved levomilnacipran for treating functional impairment in depression.9

Adverse effects. The norepinephrine uptake inhibition of levomilnacipran might be responsible for observed increases in heart rate and blood pressure in some patients, and dose-dependent urinary hesitancy and erectile dysfunction in others. The drug has no significant effect on weight in depressed patients, compared with placebo.

Continue to: The benefits of levomilnacipran

The following case illustrates the benefits of levomilnacipran in a depressed patient who suffers from chronic pain and impaired social function.

CASE Mrs. C, age 44, was referred by her outpatient psychologist and her primary care provider for management of refractory depression. She did not respond to an SSRI, an SNRI, or augmentation with bupropion and aripiprazole.

Mrs. C was on disability leave from work because of depression and cervical spine pain that might have been related to repetitive movement as a telephone customer service representative. She complained of loss of motivation, fatigue, and high anxiety about returning to work because of the many unhappy customers she felt she had to soothe.

Levomilnacipran was started at 20 mg/d for 2 days, then titrated to 40 mg/d for 5 days, 80 mg/d for 1 week, and 120 mg/d thereafter. Her previous antidepressants, fluoxetine and bupropion, were discontinued while levomilnacipran was titrated.

Mrs. C continued to receive weekly psychotherapy and physical therapy and to take tizanidine, a muscle relaxant, and over-the-counter medications for pain. Her Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score declined from 13 when levomilnacipran was started to 5 at the next visit, 6 weeks later.

Within 4 months of initiating levomilnacipran, Mrs. C returned to work with a series of cue cards to use when speaking with irate or unhappy customers. At that point, her cervical spine pain was barely noticeable and no longer interfered with function.

Vortioxetine

This agent has a novel multimodal mechanism of action (Table 3). It is an SSRI as well as a 5-HT1A full agonist and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Vortioxetine also has an inhibitory effect on 5-HT7 and 5-HT1D receptors and partial agonism of 5-HT1B receptors.

The downstream effect of this multimodal action is an increase in dopamine, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine activity in the prefrontal cortex.10 These downstream effects are thought to help restore some cognitive deficits associated with depression.11

Vortioxetine is the only antidepressant among the 3 discussed in this article that was studied over a long period to ensure that short-term benefits continue beyond the 6- to 8-week acute Phase-III studies. A high remission rate (61%) was observed in patients who were treated on an open-label basis with vortioxetine, 10 mg/d, then randomized to maintenance with vortioxetine or placebo.12

Older patients. Vortioxetine is unique among these 3 antidepressants in that it is the only one studied separately in geriatric patients: In an 8-week Phase-III trial, 452 geriatric patients age 64 to 88 were randomized to 5 mg/d of vortioxetine or placebo.13 Vortioxetine was significantly more effective than placebo at Week 6.

Vortioxetine also is the only antidepressant investigated for an effect on cognitive deficits: In a Phase-III double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 602 patients with major depressive disorder, using duloxetine as active reference, vortioxetine was found to have a significant effect on Digit Symbol Substitution Test scores, compared with placebo, independent of its antidepressant effect (ie, patients who did not show any antidepressant benefit still showed an improvement in attention, speed processing, memory, and executive function).14

We have found, therefore, that vortioxetine is helpful for depressed patients who have cognitive deficits, especially geriatric patients.

CASE Mrs. B, age 84, married, has a 4-year history of depression. She has taken several antidepressants with little consistent relief.

A brief psychiatric hospitalization 2 years ago temporarily reduced the severity of Mrs. B’s depression; gradually, she relapsed. She felt hopeless and resisted another psychiatric evaluation. Mrs. B’s family includes several clinicians, who wondered if she was developing cognitive deficits that were interfering with her recovery.

At initial evaluation, Mrs. B failed to recall 2 of 3 objects but performed the clock drawing test perfectly—qualifying her for a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment in addition to major depression. Her PHQ-9 score at baseline was 22.

On the assumption that the severity of her depression was contributing to cognitive deficits, vortioxetine, 5 mg/d, was initiated for 2 weeks and then titrated to 10 mg/d.

At 4 weeks’ follow-up, Mrs. B passed the Mini-Cog test; her PHQ-9 score fell to 8. She has remained asymptomatic for 6 months at the 10-mg/d dosage; her lowest PHQ-9 score was 5.

Adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are mild or moderate GI in nature. Weight gain and adverse sexual effects were not significantly different among patients receiving vortioxetine than among patients given placebo.

A note about the safety of these agents

All 3 of these antidepressants carry the standard black-box warning about the elevated risk of suicide in patients taking an antidepressant. None of them are approved for patients age <18.

Continue to: Suicidal ideation was reported

Suicidal ideation was reported in 11.2% of patients taking vortioxetine, compared with 12.5% of those given placebo15; 24% of patients taking levomilnacipran reported suicidal ideation, compared with 22% of those who took placebo.16 In a long-term study of 599 patients taking vilazodone, 4 given placebo exhibited suicidal behavior, compared with 2 who took vilazodone.17

Drug-drug interactions are an important consideration when vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine are prescribed in combination with other medications. See the following discussion.

Vilazodone should be taken with food because it has 72% bioavailability after a meal.18 The drug is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P (CYP) 3A4 and CYP3A5; it does not affect CYP substrates or, it’s likely, produce significant changes to other medications metabolized by the CYP pathway.

Conversely, the dosage of vilazodone should be reduced to 20 mg/d if it is co- administered with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor (eg, ketoconazole). The dosage should be increased as much as 2-fold when vilazodone is used concomitantly used with a strong CYP3A4 inducer (eg, carbamazepine) for >14 days. The maximum daily dosage should not exceed 80 mg/d.

Levomilnacipran. Unlike vilazodone and vortioxetine, levomilnacipran is affected by renal function.19 Concomitant medications, however, including those that influence CYP renal transporters (particularly CYP3A4, which metabolizes levomilnacipran), do not show an impact on the blood level of levomilnacipran.

No dosage adjustment is needed for patients who have mild renal impairment, but the maintenance dosage of levomilnacipran for patients who have moderate or severe renal impairment should not exceed 80 mg/d in 1 dose, and 60 mg/d in 1 dose, respectively.20

Vortioxetine. Seventy percent of a dose of vortioxetine is absorbed independent of food; the drug has a half-life of 66 hours. Vortioxetine is metabolized primarily by the CYP450 enzyme system, including 2D6, and, to a lesser extent, by CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19.21

Vortioxetine has minimal effect on P450 substrates in in vitro studies, which was confirmed in 4 other in vivo studies.21-23 In studies of hormonal contraception, bupropion, and omeprazole, vortioxetine did not produce significant changes in the blood level of the other medications. The blood level of vortioxetine increased by 128% when taken with the CYP2D6 inhibitor bupropion,24 but the blood level did not markedly change with other inhibitors because the drug utilizes uses several CYP pathways. Use caution, therefore, when adding bupropion to vortioxetine because the combination elevates the risk of nausea, diarrhea, and headache.

With each agent, specific benefit

Vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine each add distinct benefit to the clinician’s toolbox of treatments for major depressive disorder. Although all antidepressants to some extent alleviate anxiety and pain and reverse cognitive decline associated with depression, our experience suggests using vilazodone for anxious depressed patients; levomilnacipran for depressed patients who experience pain; and vortioxetine for depressed patients who suffer cognitive decline and for geriatric patients.

Bottom Line

The FDA has approved 3 antidepressants in the past 4 years: vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine. The hope is that these agents will bolster treatment options for major depression—perhaps especially so, as we have seen, in the anxious depressed (vilazodone), the depressed in pain (levomilnacipran), and the depressed with cognitive decline, or geriatric patients (vortioxetine).

Related Resources

• Kalia R, Mittal M, Preskorn S. Vilazodone for major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):84-86,88.

• Lincoln J, Wehler C. Vortioxetine for major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):67-70.

• Macaluso M, Kazanchi H, Malhotra V. Levomilnacipran for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):50-52,54,55.

• McIntyre RS, Lophaven S, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vortioxetine on cognitive function in depressed adults. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(10):1557-1567.

• Thase ME, Chen D, Edwards J, et al. Efficacy of vilazodone on anxiety symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(6):351-356.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban Lubiprostone • Amitiza

Buspirone • BuSpar Milnacipran • Savella

Carbamazepine • Tegretol, Equetro Omeprazole • Prilosec

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq Tizanidine • Zanaflex

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Venlafaxine • Effexor

Escitalopram • Lexapro Vilazodone • Viibryd

Fluoxetine • Prozac Vortioxetine • Brintellix

Ketoconazole • Nizoral

1. Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) Surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(1):3-21.

2. Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547.

3. Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(6):449-459.

4. Khan A. Vilazodone, a novel dual-acting serotonergic antidepressant for managing major depression. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(11):1753-1764.

5. Khan A, Sambunaris A, Edwards J, et al. Vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: efficacy across symptoms and severity of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(2):86-92.

6. Robinson DS, Kajdasz DK, Gallipoli S, et al. A 1-year, open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):643-646.

7. Saraceni MM, Venci JV, Gandhi MA. Levomilnacipran (Fetzima): a new serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Pharm Pract. 2013;27(4):389-395.

8. Deardorff WJ, Grossberg GT. A review of the clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability of the antidepressants vilazodone, levomilnacipran and vortioxetine. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(17):2525-2542.

9. Citrome L. Levomilnacipran for major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved antidepressant—what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(11):1089-1104.

10. Mørk A, Pehrson A, Brennum LT, et al. Pharmacological effects of Lu AA21004: a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340(3):666-675.

11. Pehrson AL, Leiser SC, Gulinello M, et al. Treatment of cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder-a review of the preclinical evidence for efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and the multimodal-acting antidepressant vortioxetine [published online August 5, 2014]. Eur J Pharmacol. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.044.

12. Baldwin DS, Hansen T, Florea I. Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in the long-term open-label treatment of major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(10):1717-1724.

13. Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(4):215-523.

14. Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6): 900-909.

15. Boulenger JP, Loft H, Olsen CK. Efficacy and safety of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), 15 and 20 mg/day: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced study in the acute treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(3):138-149.

16. Mago R, Forero G, Greenberg WM, et al. Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):761-771.

17. Khan A, Sambunaris A, Edwards J, et al. Vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: efficacy across symptoms and severity of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(2):86-92.

18. Boinpally R, Gad N, Gupta S, et al. Influence of CYP3A4 induction/inhibition on the pharmacokinetics of vilazodone in healthy subjects. Clin Ther. 2014; 36(11):1638-1649.

19. Chen L, Boinpally R, Greenberg WM, et al. Effect of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of levomilnacipran following a single oral dose of a levomilnacipran extended-release capsule in human participants. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34(5):351-359.

20. Asnis GM, Bose A, Gommoll CP, et al. Efficacy and safety of levomilnacipran sustained release 40 mg, 80 mg, or 120 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(3):242-248.

21. Hvenegaard MG, Bang-Andersen B, Pedersen H, et al. Identification of the cytochrome P450 and other enzymes involved in the in vitro oxidative metabolism of a novel antidepressant, Lu AA21004. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012; 40(7):1357-1365.

22. Chen G, Lee R, Højer AM, et al. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions involving vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), a multimodal antidepressant. Clin Drug Investig. 2013; 33(10):727-736.

23. Areberg J, Søgaard B, Højer AM. The clinical pharmacokinetics of Lu AA21004 and its major metabolite in healthy young volunteers. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;111(3):198-205.

24. Areberg J, Petersen KB, Chen G, et al. Population pharmacokinetic meta-analysis of vortioxetine in healthy individuals. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;115(6):552-559.

With a prevalence >17%, depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the United States and the second leading cause of disability worldwide.1,2 For decades, primary care and mental health providers have used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as first-line treatment for depression—yet the remission rate after the first trial of an antidepressant is <30%, and continues to decline after a first antidepressant failure.3

That is why clinicians continue to seek effective treatments for depression—ones that will provide quick and sustainable remission—and why scientists and pharmaceutical manufacturers have been competing to develop more effective antidepressant medications.

In the past 4 years, the FDA has approved 3 antidepressants—vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine—with the hope of increasing options for patients who suffer from major depression. These 3 antidepressants differ in their mechanisms of action from other available antidepressants, and all have been shown to have acceptable safety and tolerability profiles.

In this article, we review these novel antidepressants and present some clinical pearls for their use. We also present our observations that each agent appears to show particular advantage in a certain subpopulation of depressed patients who often do not respond, or who do not adequately respond, to other antidepressants.

Vilazodone

Vilazodone was approved by the FDA in 2011 (Table 1). The drug increases serotonin bioavailability in synapses through a strong dual action:

• blocking serotonin reuptake through the serotonin transporter

• partial agonism of the 5-HT1A presynaptic receptor.

Vilazodone also has a moderate effect on the 5-HT4 receptor and on dopamine and norepinephrine uptake inhibition.

The unique presynaptic 5-HT1A partial agonism of vilazodone is similar to that of buspirone, in which both drugs initially inhibit serotonin synthesis and neuronal firing.4 Researchers therefore expected that vilazodone would be more suitable for patients who have depression and a comorbid anxiety disorder; current FDA approval, however, is for depression only.

Adverse effects. The 5-HT4 receptor on which vilazodone acts is present in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and contributes to regulating symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)5; not surprisingly, the most frequent adverse effects of vilazodone are GI in nature (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting).

Headache is the most common non- GI side effect of vilazodone. Depressed patients who took vilazodone had no significant weight gain and did not report adverse sexual effects, compared with subjects given placebo.6

The following case—a patient with depression, significant anxiety, and IBS— exemplifies the type of patient for whom we find vilazodone most useful.

CASE Ms. A, age 19, is a college student with a history of major depressive disorder, social anxiety, and panic attacks for 2 years and IBS for 3 years. She was taking lubiprostone for IBS, with incomplete relief of GI symptoms. Because the family history included depression in Ms. A’s mother and sister, and both were doing well on escitalopram, we began a trial of that drug, 10 mg/d, that was quickly titrated to 20 mg/d.

Ms. A did not respond to 20 mg of escitalopram combined with psychotherapy.

We then started vilazodone, 10 mg/d after breakfast, for the first week, and reduced escitalopram to 10 mg/d. During Week 2, escitalopram was discontinued and vilazodone was increased to 20 mg/d. During Week 3, vilazodone was titrated to 40 mg/d.

Ms. A tolerated vilazodone well. Her depressive symptoms improved at the end of Week 2.

Unlike her experience with escitalopram, Ms. A’s anxiety symptoms—tenseness, racing thoughts, and panic attacks—all diminished when she switched to vilazodone. Notably, her IBS symptoms also were relieved, and she discontinued lubiprostone.

Ms. A’s depression remained in remission for 2 years, except for a brief period one summer, when she thought she “could do without any medication.” She tapered the vilazodone, week by week, to 10 mg/d, but her anxiety and bowel symptoms resurfaced to a degree that she resumed the 40-mg/d dosage.

Levomilnacipran

This drug is a 2013 addition to the small serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) family of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, and duloxetine7 (Table 2). Levomilnacipran is the enantiomer of milnacipran, approved in Europe for depression but only for fibromyalgia pain and peripheral neuropathy in the United States.8 (Levomilnacipran is not FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia pain.)

Levomilnacipran is unique because it is more of an NSRI, so to speak, than an SNRI: That is, the drug’s uptake inhibition of norepinephrine is more potent than its serotonin inhibition. Theoretically, levomilnacipran should help improve cognitive functions linked to the action of norepinephrine, such as concentration and motivation, and in turn, improve social function. The FDA also has approved levomilnacipran for treating functional impairment in depression.9

Adverse effects. The norepinephrine uptake inhibition of levomilnacipran might be responsible for observed increases in heart rate and blood pressure in some patients, and dose-dependent urinary hesitancy and erectile dysfunction in others. The drug has no significant effect on weight in depressed patients, compared with placebo.

Continue to: The benefits of levomilnacipran

The following case illustrates the benefits of levomilnacipran in a depressed patient who suffers from chronic pain and impaired social function.

CASE Mrs. C, age 44, was referred by her outpatient psychologist and her primary care provider for management of refractory depression. She did not respond to an SSRI, an SNRI, or augmentation with bupropion and aripiprazole.

Mrs. C was on disability leave from work because of depression and cervical spine pain that might have been related to repetitive movement as a telephone customer service representative. She complained of loss of motivation, fatigue, and high anxiety about returning to work because of the many unhappy customers she felt she had to soothe.

Levomilnacipran was started at 20 mg/d for 2 days, then titrated to 40 mg/d for 5 days, 80 mg/d for 1 week, and 120 mg/d thereafter. Her previous antidepressants, fluoxetine and bupropion, were discontinued while levomilnacipran was titrated.

Mrs. C continued to receive weekly psychotherapy and physical therapy and to take tizanidine, a muscle relaxant, and over-the-counter medications for pain. Her Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score declined from 13 when levomilnacipran was started to 5 at the next visit, 6 weeks later.

Within 4 months of initiating levomilnacipran, Mrs. C returned to work with a series of cue cards to use when speaking with irate or unhappy customers. At that point, her cervical spine pain was barely noticeable and no longer interfered with function.

Vortioxetine

This agent has a novel multimodal mechanism of action (Table 3). It is an SSRI as well as a 5-HT1A full agonist and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Vortioxetine also has an inhibitory effect on 5-HT7 and 5-HT1D receptors and partial agonism of 5-HT1B receptors.

The downstream effect of this multimodal action is an increase in dopamine, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine activity in the prefrontal cortex.10 These downstream effects are thought to help restore some cognitive deficits associated with depression.11

Vortioxetine is the only antidepressant among the 3 discussed in this article that was studied over a long period to ensure that short-term benefits continue beyond the 6- to 8-week acute Phase-III studies. A high remission rate (61%) was observed in patients who were treated on an open-label basis with vortioxetine, 10 mg/d, then randomized to maintenance with vortioxetine or placebo.12

Older patients. Vortioxetine is unique among these 3 antidepressants in that it is the only one studied separately in geriatric patients: In an 8-week Phase-III trial, 452 geriatric patients age 64 to 88 were randomized to 5 mg/d of vortioxetine or placebo.13 Vortioxetine was significantly more effective than placebo at Week 6.

Vortioxetine also is the only antidepressant investigated for an effect on cognitive deficits: In a Phase-III double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 602 patients with major depressive disorder, using duloxetine as active reference, vortioxetine was found to have a significant effect on Digit Symbol Substitution Test scores, compared with placebo, independent of its antidepressant effect (ie, patients who did not show any antidepressant benefit still showed an improvement in attention, speed processing, memory, and executive function).14

We have found, therefore, that vortioxetine is helpful for depressed patients who have cognitive deficits, especially geriatric patients.

CASE Mrs. B, age 84, married, has a 4-year history of depression. She has taken several antidepressants with little consistent relief.

A brief psychiatric hospitalization 2 years ago temporarily reduced the severity of Mrs. B’s depression; gradually, she relapsed. She felt hopeless and resisted another psychiatric evaluation. Mrs. B’s family includes several clinicians, who wondered if she was developing cognitive deficits that were interfering with her recovery.

At initial evaluation, Mrs. B failed to recall 2 of 3 objects but performed the clock drawing test perfectly—qualifying her for a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment in addition to major depression. Her PHQ-9 score at baseline was 22.

On the assumption that the severity of her depression was contributing to cognitive deficits, vortioxetine, 5 mg/d, was initiated for 2 weeks and then titrated to 10 mg/d.

At 4 weeks’ follow-up, Mrs. B passed the Mini-Cog test; her PHQ-9 score fell to 8. She has remained asymptomatic for 6 months at the 10-mg/d dosage; her lowest PHQ-9 score was 5.

Adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are mild or moderate GI in nature. Weight gain and adverse sexual effects were not significantly different among patients receiving vortioxetine than among patients given placebo.

A note about the safety of these agents

All 3 of these antidepressants carry the standard black-box warning about the elevated risk of suicide in patients taking an antidepressant. None of them are approved for patients age <18.

Continue to: Suicidal ideation was reported

Suicidal ideation was reported in 11.2% of patients taking vortioxetine, compared with 12.5% of those given placebo15; 24% of patients taking levomilnacipran reported suicidal ideation, compared with 22% of those who took placebo.16 In a long-term study of 599 patients taking vilazodone, 4 given placebo exhibited suicidal behavior, compared with 2 who took vilazodone.17

Drug-drug interactions are an important consideration when vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine are prescribed in combination with other medications. See the following discussion.

Vilazodone should be taken with food because it has 72% bioavailability after a meal.18 The drug is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P (CYP) 3A4 and CYP3A5; it does not affect CYP substrates or, it’s likely, produce significant changes to other medications metabolized by the CYP pathway.

Conversely, the dosage of vilazodone should be reduced to 20 mg/d if it is co- administered with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor (eg, ketoconazole). The dosage should be increased as much as 2-fold when vilazodone is used concomitantly used with a strong CYP3A4 inducer (eg, carbamazepine) for >14 days. The maximum daily dosage should not exceed 80 mg/d.

Levomilnacipran. Unlike vilazodone and vortioxetine, levomilnacipran is affected by renal function.19 Concomitant medications, however, including those that influence CYP renal transporters (particularly CYP3A4, which metabolizes levomilnacipran), do not show an impact on the blood level of levomilnacipran.

No dosage adjustment is needed for patients who have mild renal impairment, but the maintenance dosage of levomilnacipran for patients who have moderate or severe renal impairment should not exceed 80 mg/d in 1 dose, and 60 mg/d in 1 dose, respectively.20

Vortioxetine. Seventy percent of a dose of vortioxetine is absorbed independent of food; the drug has a half-life of 66 hours. Vortioxetine is metabolized primarily by the CYP450 enzyme system, including 2D6, and, to a lesser extent, by CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19.21

Vortioxetine has minimal effect on P450 substrates in in vitro studies, which was confirmed in 4 other in vivo studies.21-23 In studies of hormonal contraception, bupropion, and omeprazole, vortioxetine did not produce significant changes in the blood level of the other medications. The blood level of vortioxetine increased by 128% when taken with the CYP2D6 inhibitor bupropion,24 but the blood level did not markedly change with other inhibitors because the drug utilizes uses several CYP pathways. Use caution, therefore, when adding bupropion to vortioxetine because the combination elevates the risk of nausea, diarrhea, and headache.

With each agent, specific benefit

Vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine each add distinct benefit to the clinician’s toolbox of treatments for major depressive disorder. Although all antidepressants to some extent alleviate anxiety and pain and reverse cognitive decline associated with depression, our experience suggests using vilazodone for anxious depressed patients; levomilnacipran for depressed patients who experience pain; and vortioxetine for depressed patients who suffer cognitive decline and for geriatric patients.

Bottom Line

The FDA has approved 3 antidepressants in the past 4 years: vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine. The hope is that these agents will bolster treatment options for major depression—perhaps especially so, as we have seen, in the anxious depressed (vilazodone), the depressed in pain (levomilnacipran), and the depressed with cognitive decline, or geriatric patients (vortioxetine).

Related Resources

• Kalia R, Mittal M, Preskorn S. Vilazodone for major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):84-86,88.

• Lincoln J, Wehler C. Vortioxetine for major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):67-70.

• Macaluso M, Kazanchi H, Malhotra V. Levomilnacipran for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):50-52,54,55.

• McIntyre RS, Lophaven S, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vortioxetine on cognitive function in depressed adults. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(10):1557-1567.

• Thase ME, Chen D, Edwards J, et al. Efficacy of vilazodone on anxiety symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(6):351-356.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban Lubiprostone • Amitiza

Buspirone • BuSpar Milnacipran • Savella

Carbamazepine • Tegretol, Equetro Omeprazole • Prilosec

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq Tizanidine • Zanaflex

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Venlafaxine • Effexor

Escitalopram • Lexapro Vilazodone • Viibryd

Fluoxetine • Prozac Vortioxetine • Brintellix

Ketoconazole • Nizoral

With a prevalence >17%, depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the United States and the second leading cause of disability worldwide.1,2 For decades, primary care and mental health providers have used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as first-line treatment for depression—yet the remission rate after the first trial of an antidepressant is <30%, and continues to decline after a first antidepressant failure.3

That is why clinicians continue to seek effective treatments for depression—ones that will provide quick and sustainable remission—and why scientists and pharmaceutical manufacturers have been competing to develop more effective antidepressant medications.

In the past 4 years, the FDA has approved 3 antidepressants—vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine—with the hope of increasing options for patients who suffer from major depression. These 3 antidepressants differ in their mechanisms of action from other available antidepressants, and all have been shown to have acceptable safety and tolerability profiles.

In this article, we review these novel antidepressants and present some clinical pearls for their use. We also present our observations that each agent appears to show particular advantage in a certain subpopulation of depressed patients who often do not respond, or who do not adequately respond, to other antidepressants.

Vilazodone

Vilazodone was approved by the FDA in 2011 (Table 1). The drug increases serotonin bioavailability in synapses through a strong dual action:

• blocking serotonin reuptake through the serotonin transporter

• partial agonism of the 5-HT1A presynaptic receptor.

Vilazodone also has a moderate effect on the 5-HT4 receptor and on dopamine and norepinephrine uptake inhibition.

The unique presynaptic 5-HT1A partial agonism of vilazodone is similar to that of buspirone, in which both drugs initially inhibit serotonin synthesis and neuronal firing.4 Researchers therefore expected that vilazodone would be more suitable for patients who have depression and a comorbid anxiety disorder; current FDA approval, however, is for depression only.

Adverse effects. The 5-HT4 receptor on which vilazodone acts is present in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and contributes to regulating symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)5; not surprisingly, the most frequent adverse effects of vilazodone are GI in nature (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting).

Headache is the most common non- GI side effect of vilazodone. Depressed patients who took vilazodone had no significant weight gain and did not report adverse sexual effects, compared with subjects given placebo.6

The following case—a patient with depression, significant anxiety, and IBS— exemplifies the type of patient for whom we find vilazodone most useful.

CASE Ms. A, age 19, is a college student with a history of major depressive disorder, social anxiety, and panic attacks for 2 years and IBS for 3 years. She was taking lubiprostone for IBS, with incomplete relief of GI symptoms. Because the family history included depression in Ms. A’s mother and sister, and both were doing well on escitalopram, we began a trial of that drug, 10 mg/d, that was quickly titrated to 20 mg/d.

Ms. A did not respond to 20 mg of escitalopram combined with psychotherapy.

We then started vilazodone, 10 mg/d after breakfast, for the first week, and reduced escitalopram to 10 mg/d. During Week 2, escitalopram was discontinued and vilazodone was increased to 20 mg/d. During Week 3, vilazodone was titrated to 40 mg/d.

Ms. A tolerated vilazodone well. Her depressive symptoms improved at the end of Week 2.

Unlike her experience with escitalopram, Ms. A’s anxiety symptoms—tenseness, racing thoughts, and panic attacks—all diminished when she switched to vilazodone. Notably, her IBS symptoms also were relieved, and she discontinued lubiprostone.

Ms. A’s depression remained in remission for 2 years, except for a brief period one summer, when she thought she “could do without any medication.” She tapered the vilazodone, week by week, to 10 mg/d, but her anxiety and bowel symptoms resurfaced to a degree that she resumed the 40-mg/d dosage.

Levomilnacipran

This drug is a 2013 addition to the small serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) family of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, and duloxetine7 (Table 2). Levomilnacipran is the enantiomer of milnacipran, approved in Europe for depression but only for fibromyalgia pain and peripheral neuropathy in the United States.8 (Levomilnacipran is not FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia pain.)

Levomilnacipran is unique because it is more of an NSRI, so to speak, than an SNRI: That is, the drug’s uptake inhibition of norepinephrine is more potent than its serotonin inhibition. Theoretically, levomilnacipran should help improve cognitive functions linked to the action of norepinephrine, such as concentration and motivation, and in turn, improve social function. The FDA also has approved levomilnacipran for treating functional impairment in depression.9

Adverse effects. The norepinephrine uptake inhibition of levomilnacipran might be responsible for observed increases in heart rate and blood pressure in some patients, and dose-dependent urinary hesitancy and erectile dysfunction in others. The drug has no significant effect on weight in depressed patients, compared with placebo.

Continue to: The benefits of levomilnacipran

The following case illustrates the benefits of levomilnacipran in a depressed patient who suffers from chronic pain and impaired social function.

CASE Mrs. C, age 44, was referred by her outpatient psychologist and her primary care provider for management of refractory depression. She did not respond to an SSRI, an SNRI, or augmentation with bupropion and aripiprazole.

Mrs. C was on disability leave from work because of depression and cervical spine pain that might have been related to repetitive movement as a telephone customer service representative. She complained of loss of motivation, fatigue, and high anxiety about returning to work because of the many unhappy customers she felt she had to soothe.

Levomilnacipran was started at 20 mg/d for 2 days, then titrated to 40 mg/d for 5 days, 80 mg/d for 1 week, and 120 mg/d thereafter. Her previous antidepressants, fluoxetine and bupropion, were discontinued while levomilnacipran was titrated.

Mrs. C continued to receive weekly psychotherapy and physical therapy and to take tizanidine, a muscle relaxant, and over-the-counter medications for pain. Her Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score declined from 13 when levomilnacipran was started to 5 at the next visit, 6 weeks later.

Within 4 months of initiating levomilnacipran, Mrs. C returned to work with a series of cue cards to use when speaking with irate or unhappy customers. At that point, her cervical spine pain was barely noticeable and no longer interfered with function.

Vortioxetine

This agent has a novel multimodal mechanism of action (Table 3). It is an SSRI as well as a 5-HT1A full agonist and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Vortioxetine also has an inhibitory effect on 5-HT7 and 5-HT1D receptors and partial agonism of 5-HT1B receptors.

The downstream effect of this multimodal action is an increase in dopamine, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine activity in the prefrontal cortex.10 These downstream effects are thought to help restore some cognitive deficits associated with depression.11

Vortioxetine is the only antidepressant among the 3 discussed in this article that was studied over a long period to ensure that short-term benefits continue beyond the 6- to 8-week acute Phase-III studies. A high remission rate (61%) was observed in patients who were treated on an open-label basis with vortioxetine, 10 mg/d, then randomized to maintenance with vortioxetine or placebo.12

Older patients. Vortioxetine is unique among these 3 antidepressants in that it is the only one studied separately in geriatric patients: In an 8-week Phase-III trial, 452 geriatric patients age 64 to 88 were randomized to 5 mg/d of vortioxetine or placebo.13 Vortioxetine was significantly more effective than placebo at Week 6.

Vortioxetine also is the only antidepressant investigated for an effect on cognitive deficits: In a Phase-III double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 602 patients with major depressive disorder, using duloxetine as active reference, vortioxetine was found to have a significant effect on Digit Symbol Substitution Test scores, compared with placebo, independent of its antidepressant effect (ie, patients who did not show any antidepressant benefit still showed an improvement in attention, speed processing, memory, and executive function).14

We have found, therefore, that vortioxetine is helpful for depressed patients who have cognitive deficits, especially geriatric patients.

CASE Mrs. B, age 84, married, has a 4-year history of depression. She has taken several antidepressants with little consistent relief.

A brief psychiatric hospitalization 2 years ago temporarily reduced the severity of Mrs. B’s depression; gradually, she relapsed. She felt hopeless and resisted another psychiatric evaluation. Mrs. B’s family includes several clinicians, who wondered if she was developing cognitive deficits that were interfering with her recovery.

At initial evaluation, Mrs. B failed to recall 2 of 3 objects but performed the clock drawing test perfectly—qualifying her for a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment in addition to major depression. Her PHQ-9 score at baseline was 22.

On the assumption that the severity of her depression was contributing to cognitive deficits, vortioxetine, 5 mg/d, was initiated for 2 weeks and then titrated to 10 mg/d.

At 4 weeks’ follow-up, Mrs. B passed the Mini-Cog test; her PHQ-9 score fell to 8. She has remained asymptomatic for 6 months at the 10-mg/d dosage; her lowest PHQ-9 score was 5.

Adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are mild or moderate GI in nature. Weight gain and adverse sexual effects were not significantly different among patients receiving vortioxetine than among patients given placebo.

A note about the safety of these agents

All 3 of these antidepressants carry the standard black-box warning about the elevated risk of suicide in patients taking an antidepressant. None of them are approved for patients age <18.

Continue to: Suicidal ideation was reported

Suicidal ideation was reported in 11.2% of patients taking vortioxetine, compared with 12.5% of those given placebo15; 24% of patients taking levomilnacipran reported suicidal ideation, compared with 22% of those who took placebo.16 In a long-term study of 599 patients taking vilazodone, 4 given placebo exhibited suicidal behavior, compared with 2 who took vilazodone.17

Drug-drug interactions are an important consideration when vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine are prescribed in combination with other medications. See the following discussion.

Vilazodone should be taken with food because it has 72% bioavailability after a meal.18 The drug is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P (CYP) 3A4 and CYP3A5; it does not affect CYP substrates or, it’s likely, produce significant changes to other medications metabolized by the CYP pathway.

Conversely, the dosage of vilazodone should be reduced to 20 mg/d if it is co- administered with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor (eg, ketoconazole). The dosage should be increased as much as 2-fold when vilazodone is used concomitantly used with a strong CYP3A4 inducer (eg, carbamazepine) for >14 days. The maximum daily dosage should not exceed 80 mg/d.

Levomilnacipran. Unlike vilazodone and vortioxetine, levomilnacipran is affected by renal function.19 Concomitant medications, however, including those that influence CYP renal transporters (particularly CYP3A4, which metabolizes levomilnacipran), do not show an impact on the blood level of levomilnacipran.

No dosage adjustment is needed for patients who have mild renal impairment, but the maintenance dosage of levomilnacipran for patients who have moderate or severe renal impairment should not exceed 80 mg/d in 1 dose, and 60 mg/d in 1 dose, respectively.20

Vortioxetine. Seventy percent of a dose of vortioxetine is absorbed independent of food; the drug has a half-life of 66 hours. Vortioxetine is metabolized primarily by the CYP450 enzyme system, including 2D6, and, to a lesser extent, by CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19.21

Vortioxetine has minimal effect on P450 substrates in in vitro studies, which was confirmed in 4 other in vivo studies.21-23 In studies of hormonal contraception, bupropion, and omeprazole, vortioxetine did not produce significant changes in the blood level of the other medications. The blood level of vortioxetine increased by 128% when taken with the CYP2D6 inhibitor bupropion,24 but the blood level did not markedly change with other inhibitors because the drug utilizes uses several CYP pathways. Use caution, therefore, when adding bupropion to vortioxetine because the combination elevates the risk of nausea, diarrhea, and headache.

With each agent, specific benefit

Vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine each add distinct benefit to the clinician’s toolbox of treatments for major depressive disorder. Although all antidepressants to some extent alleviate anxiety and pain and reverse cognitive decline associated with depression, our experience suggests using vilazodone for anxious depressed patients; levomilnacipran for depressed patients who experience pain; and vortioxetine for depressed patients who suffer cognitive decline and for geriatric patients.

Bottom Line

The FDA has approved 3 antidepressants in the past 4 years: vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine. The hope is that these agents will bolster treatment options for major depression—perhaps especially so, as we have seen, in the anxious depressed (vilazodone), the depressed in pain (levomilnacipran), and the depressed with cognitive decline, or geriatric patients (vortioxetine).

Related Resources

• Kalia R, Mittal M, Preskorn S. Vilazodone for major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):84-86,88.

• Lincoln J, Wehler C. Vortioxetine for major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):67-70.

• Macaluso M, Kazanchi H, Malhotra V. Levomilnacipran for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):50-52,54,55.

• McIntyre RS, Lophaven S, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vortioxetine on cognitive function in depressed adults. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(10):1557-1567.

• Thase ME, Chen D, Edwards J, et al. Efficacy of vilazodone on anxiety symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(6):351-356.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban Lubiprostone • Amitiza

Buspirone • BuSpar Milnacipran • Savella

Carbamazepine • Tegretol, Equetro Omeprazole • Prilosec

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq Tizanidine • Zanaflex

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Venlafaxine • Effexor

Escitalopram • Lexapro Vilazodone • Viibryd

Fluoxetine • Prozac Vortioxetine • Brintellix

Ketoconazole • Nizoral

1. Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) Surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(1):3-21.

2. Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547.

3. Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(6):449-459.

4. Khan A. Vilazodone, a novel dual-acting serotonergic antidepressant for managing major depression. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(11):1753-1764.

5. Khan A, Sambunaris A, Edwards J, et al. Vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: efficacy across symptoms and severity of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(2):86-92.

6. Robinson DS, Kajdasz DK, Gallipoli S, et al. A 1-year, open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):643-646.

7. Saraceni MM, Venci JV, Gandhi MA. Levomilnacipran (Fetzima): a new serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Pharm Pract. 2013;27(4):389-395.

8. Deardorff WJ, Grossberg GT. A review of the clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability of the antidepressants vilazodone, levomilnacipran and vortioxetine. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(17):2525-2542.

9. Citrome L. Levomilnacipran for major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved antidepressant—what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(11):1089-1104.

10. Mørk A, Pehrson A, Brennum LT, et al. Pharmacological effects of Lu AA21004: a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340(3):666-675.

11. Pehrson AL, Leiser SC, Gulinello M, et al. Treatment of cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder-a review of the preclinical evidence for efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and the multimodal-acting antidepressant vortioxetine [published online August 5, 2014]. Eur J Pharmacol. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.044.

12. Baldwin DS, Hansen T, Florea I. Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in the long-term open-label treatment of major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(10):1717-1724.

13. Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(4):215-523.

14. Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6): 900-909.

15. Boulenger JP, Loft H, Olsen CK. Efficacy and safety of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), 15 and 20 mg/day: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced study in the acute treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(3):138-149.

16. Mago R, Forero G, Greenberg WM, et al. Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):761-771.

17. Khan A, Sambunaris A, Edwards J, et al. Vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: efficacy across symptoms and severity of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(2):86-92.

18. Boinpally R, Gad N, Gupta S, et al. Influence of CYP3A4 induction/inhibition on the pharmacokinetics of vilazodone in healthy subjects. Clin Ther. 2014; 36(11):1638-1649.

19. Chen L, Boinpally R, Greenberg WM, et al. Effect of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of levomilnacipran following a single oral dose of a levomilnacipran extended-release capsule in human participants. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34(5):351-359.

20. Asnis GM, Bose A, Gommoll CP, et al. Efficacy and safety of levomilnacipran sustained release 40 mg, 80 mg, or 120 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(3):242-248.

21. Hvenegaard MG, Bang-Andersen B, Pedersen H, et al. Identification of the cytochrome P450 and other enzymes involved in the in vitro oxidative metabolism of a novel antidepressant, Lu AA21004. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012; 40(7):1357-1365.

22. Chen G, Lee R, Højer AM, et al. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions involving vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), a multimodal antidepressant. Clin Drug Investig. 2013; 33(10):727-736.

23. Areberg J, Søgaard B, Højer AM. The clinical pharmacokinetics of Lu AA21004 and its major metabolite in healthy young volunteers. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;111(3):198-205.

24. Areberg J, Petersen KB, Chen G, et al. Population pharmacokinetic meta-analysis of vortioxetine in healthy individuals. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;115(6):552-559.

1. Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) Surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(1):3-21.

2. Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547.

3. Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(6):449-459.

4. Khan A. Vilazodone, a novel dual-acting serotonergic antidepressant for managing major depression. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(11):1753-1764.

5. Khan A, Sambunaris A, Edwards J, et al. Vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: efficacy across symptoms and severity of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(2):86-92.

6. Robinson DS, Kajdasz DK, Gallipoli S, et al. A 1-year, open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):643-646.

7. Saraceni MM, Venci JV, Gandhi MA. Levomilnacipran (Fetzima): a new serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Pharm Pract. 2013;27(4):389-395.

8. Deardorff WJ, Grossberg GT. A review of the clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability of the antidepressants vilazodone, levomilnacipran and vortioxetine. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(17):2525-2542.

9. Citrome L. Levomilnacipran for major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved antidepressant—what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(11):1089-1104.

10. Mørk A, Pehrson A, Brennum LT, et al. Pharmacological effects of Lu AA21004: a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340(3):666-675.

11. Pehrson AL, Leiser SC, Gulinello M, et al. Treatment of cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder-a review of the preclinical evidence for efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and the multimodal-acting antidepressant vortioxetine [published online August 5, 2014]. Eur J Pharmacol. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.044.

12. Baldwin DS, Hansen T, Florea I. Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in the long-term open-label treatment of major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(10):1717-1724.

13. Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(4):215-523.

14. Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6): 900-909.

15. Boulenger JP, Loft H, Olsen CK. Efficacy and safety of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), 15 and 20 mg/day: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced study in the acute treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(3):138-149.

16. Mago R, Forero G, Greenberg WM, et al. Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):761-771.

17. Khan A, Sambunaris A, Edwards J, et al. Vilazodone in the treatment of major depressive disorder: efficacy across symptoms and severity of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(2):86-92.

18. Boinpally R, Gad N, Gupta S, et al. Influence of CYP3A4 induction/inhibition on the pharmacokinetics of vilazodone in healthy subjects. Clin Ther. 2014; 36(11):1638-1649.

19. Chen L, Boinpally R, Greenberg WM, et al. Effect of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of levomilnacipran following a single oral dose of a levomilnacipran extended-release capsule in human participants. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34(5):351-359.

20. Asnis GM, Bose A, Gommoll CP, et al. Efficacy and safety of levomilnacipran sustained release 40 mg, 80 mg, or 120 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(3):242-248.

21. Hvenegaard MG, Bang-Andersen B, Pedersen H, et al. Identification of the cytochrome P450 and other enzymes involved in the in vitro oxidative metabolism of a novel antidepressant, Lu AA21004. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012; 40(7):1357-1365.

22. Chen G, Lee R, Højer AM, et al. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions involving vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), a multimodal antidepressant. Clin Drug Investig. 2013; 33(10):727-736.

23. Areberg J, Søgaard B, Højer AM. The clinical pharmacokinetics of Lu AA21004 and its major metabolite in healthy young volunteers. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;111(3):198-205.

24. Areberg J, Petersen KB, Chen G, et al. Population pharmacokinetic meta-analysis of vortioxetine in healthy individuals. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;115(6):552-559.

Court allows generic colchicine to enter market

After a 5-year monopoly on the sale of colchicine put the gout medication out of reach for many patients, a federal judge in January denied an injunction request by Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A. to halt the distribution of colchicine products by Hikma Pharmaceuticals PLC.

The availability of a generic colchicine will introduce competition into the marketplace and drive down costs, said Dr. E. William St.Clair, president of the American College of Rheumatology and chief of the division of rheumatology and immunology at Duke University, Durham, N.C. The ACR issued a friend-of-the-court brief to the federal district court in support of a generic colchicine product entering the market.

“With the steep price increase in colchicine, many patients with gout were now unable to afford chronic colchicine therapy,” Dr. St.Clair said in an interview. “Improving access to colchicine by making it more affordable will increase patient compliance and reduce the suffering and disability associated with repeated gout flares.”

The debate over colchicine and the right to market the medication has a lengthy history. The drug has been prescribed to treat gout for decades, predating the law that requires drugs to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration. In 2009, the FDA approved a brand name colchicine product (Colcrys) by Mutual Pharmaceutical Company/URL Pharmacy Inc. – now Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A. – after the company conducted clinical trials on dosing regimens and performed drug interaction studies. The FDA’s approval of Colcrys came with exclusive marketing rights for gout for 3 years and for familial Mediterranean fever for 7 years.

Mutual Pharmaceutical Company then sued other manufacturers of colchicine, claiming the drug makers were falsely implying that their products were FDA approved. Shortly later, the FDA ordered companies marketing single-ingredient oral colchicine to remove their unapproved products from the market. Physicians and patients meanwhile saw the price of colchicine increase from about 10 cents per tablet to $5 per tablet.

In September 2014, the FDA granted approval for Hikma to market and sell Mitigare, a colchicine capsule for the prophylactic treatment of gout. Hikma had also planned to launch an authorized generic of Mitigare. Before Mitigare could fully launch, Takeda obtained a temporary restraining order against the sale of colchicine products by Hikma, citing Takeda’s patents for acute gout treatment. Takeda simultaneously sued the FDA in a separate proceeding. Takeda said the FDA’s approval of Hikma’s colchicine product was legally impermissible.

In its brief to the federal court, the ACR argued the public interest would be severely disserved by the barring of Hikma’s colchicine product.

“The unfortunate reality is that nearly 30% of patients in the United States take risky and potentially dangerous steps to save money on prescription medicines, with many choosing to skip doses, or not fill their prescriptions altogether,” the ACR said in its brief. “Takeda’s monopoly and the associated price increase for colchicine has resulted in precisely the sorts of risky behavior described.”

A lower court denied Takeda’s preliminary injunction request and the decision was upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on Jan. 9. Pending the outcome of further litigation, the federal court ruled that both Takeda and Hikma are free to immediately offer colchicine products for prophylactic use. Also on Jan. 9, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia denied Takeda’s request to overturn the FDA’s approval of Mitigare.

In an interview, a Takeda spokeswoman said the company will continue its patent infringement litigation against Hikma and its U.S. subsidiary, West-Ward Pharmaceuticals, along with its lawsuit against the FDA. The company offered no comment on the judge’s decision to deny the injunction.

West-Ward, meanwhile, launched its authorized generic to Mitigare following the judge’s Jan. 9 decision, and Mitigare’s entry to the market was resumed.

“We immediately sought to launch a generic of Mitigare to ensure that adult patients in need of treatment for the prophylaxis of gout flares had access to a lower-cost, alternative colchicine capsule product,” said Spiro Gavaris, vice president of sales and marketing for West-Ward Pharmaceuticals. “We understood that in recent years, some patients may have lost access to, or became frustrated with, colchicine when there was one brand product at a significantly higher price point. With our launch of the authorized generic of Mitigare capsules, doctors can now choose to prescribe Mitigare for the prophylaxis of gout flares in adults, thereby providing these patients with a lower cost generic medication.”

Days after the decision, Takeda announced that it also would be offering access to a generic colchicine. In a statement, the company said it would partner with Prasco Laboratories to distribute Colchicine Tablets, USP, an authorized generic version of Colcrys. The product is being marketed under the Prasco label and became available in U.S. pharmacies in mid-January.

“At Takeda, we remain committed to providing patients with therapies that are safe, efficacious and meet high quality standards,” Douglas Cole, Takeda Pharmaceuticals President, said in a statement. “This new partnership will help enhance patient access to an important gout medicine by supplying Prasco with Colchicine Tablets, USP, manufactured under the same rigorous standards and processes as Colcrys.”

Prices for the Mitigare authorized generic and the Colcrys authorized generic have not been publicly announced. In an interview, West-Ward said it could not comment on exact savings to patients as savings will vary between insurance plans and pharmacy distribution channels.

“Our goal is to provide the most aggressive discounts on generic colchicine in the market with the intent for those discounts to be passed on to adult patients in need of treatment for the prophylaxis of gout flares,” Mr. Gavaris said.

At this article’s deadline, Takeda and Prasco had not responded to a question about the price of the generic Colcrys.

While rheumatologists expressed relief that generic colchicine products have finally become available, they also voiced concerns about potential barriers to access.

“I am proud of what the ACR did here and would hope that it serves as a model for future efforts by professional medical organizations to get into the (often legal) trenches and truly help their patients get affordable care. … [They] put their mouth where the money is and stood up for patients,” said Dr. Christopher M. Burns, a rheumatologist at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, N.H.

“I hope that this will, in fact, reduce the pricing for colchicine, and that it will not allow payers to add an onerous out-of-pocket cost for the drug far in excess of the cost if paid without utilizing pharmacy benefits,” said Dr. Norman B. Gaylis, a rheumatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla.

Dr. St.Clair added that the future availability and cost of generic colchicine is not certain given common supply-and-demand problems that can arise with generic drugs.

“We have observed critical shortages of several generic medications during the past several years that have drastically affected medical therapy for many common conditions,” he said in an interview. “We will need to keep a close eye on the supply of generic colchicine to ensure it keeps up with the demand. The FDA and the pharmaceutical industry has an obligation to ensure that patients have access to these critical generic drugs.”

On Twitter @legal_med

After a 5-year monopoly on the sale of colchicine put the gout medication out of reach for many patients, a federal judge in January denied an injunction request by Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A. to halt the distribution of colchicine products by Hikma Pharmaceuticals PLC.

The availability of a generic colchicine will introduce competition into the marketplace and drive down costs, said Dr. E. William St.Clair, president of the American College of Rheumatology and chief of the division of rheumatology and immunology at Duke University, Durham, N.C. The ACR issued a friend-of-the-court brief to the federal district court in support of a generic colchicine product entering the market.

“With the steep price increase in colchicine, many patients with gout were now unable to afford chronic colchicine therapy,” Dr. St.Clair said in an interview. “Improving access to colchicine by making it more affordable will increase patient compliance and reduce the suffering and disability associated with repeated gout flares.”

The debate over colchicine and the right to market the medication has a lengthy history. The drug has been prescribed to treat gout for decades, predating the law that requires drugs to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration. In 2009, the FDA approved a brand name colchicine product (Colcrys) by Mutual Pharmaceutical Company/URL Pharmacy Inc. – now Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A. – after the company conducted clinical trials on dosing regimens and performed drug interaction studies. The FDA’s approval of Colcrys came with exclusive marketing rights for gout for 3 years and for familial Mediterranean fever for 7 years.

Mutual Pharmaceutical Company then sued other manufacturers of colchicine, claiming the drug makers were falsely implying that their products were FDA approved. Shortly later, the FDA ordered companies marketing single-ingredient oral colchicine to remove their unapproved products from the market. Physicians and patients meanwhile saw the price of colchicine increase from about 10 cents per tablet to $5 per tablet.

In September 2014, the FDA granted approval for Hikma to market and sell Mitigare, a colchicine capsule for the prophylactic treatment of gout. Hikma had also planned to launch an authorized generic of Mitigare. Before Mitigare could fully launch, Takeda obtained a temporary restraining order against the sale of colchicine products by Hikma, citing Takeda’s patents for acute gout treatment. Takeda simultaneously sued the FDA in a separate proceeding. Takeda said the FDA’s approval of Hikma’s colchicine product was legally impermissible.

In its brief to the federal court, the ACR argued the public interest would be severely disserved by the barring of Hikma’s colchicine product.

“The unfortunate reality is that nearly 30% of patients in the United States take risky and potentially dangerous steps to save money on prescription medicines, with many choosing to skip doses, or not fill their prescriptions altogether,” the ACR said in its brief. “Takeda’s monopoly and the associated price increase for colchicine has resulted in precisely the sorts of risky behavior described.”

A lower court denied Takeda’s preliminary injunction request and the decision was upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on Jan. 9. Pending the outcome of further litigation, the federal court ruled that both Takeda and Hikma are free to immediately offer colchicine products for prophylactic use. Also on Jan. 9, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia denied Takeda’s request to overturn the FDA’s approval of Mitigare.

In an interview, a Takeda spokeswoman said the company will continue its patent infringement litigation against Hikma and its U.S. subsidiary, West-Ward Pharmaceuticals, along with its lawsuit against the FDA. The company offered no comment on the judge’s decision to deny the injunction.

West-Ward, meanwhile, launched its authorized generic to Mitigare following the judge’s Jan. 9 decision, and Mitigare’s entry to the market was resumed.

“We immediately sought to launch a generic of Mitigare to ensure that adult patients in need of treatment for the prophylaxis of gout flares had access to a lower-cost, alternative colchicine capsule product,” said Spiro Gavaris, vice president of sales and marketing for West-Ward Pharmaceuticals. “We understood that in recent years, some patients may have lost access to, or became frustrated with, colchicine when there was one brand product at a significantly higher price point. With our launch of the authorized generic of Mitigare capsules, doctors can now choose to prescribe Mitigare for the prophylaxis of gout flares in adults, thereby providing these patients with a lower cost generic medication.”

Days after the decision, Takeda announced that it also would be offering access to a generic colchicine. In a statement, the company said it would partner with Prasco Laboratories to distribute Colchicine Tablets, USP, an authorized generic version of Colcrys. The product is being marketed under the Prasco label and became available in U.S. pharmacies in mid-January.

“At Takeda, we remain committed to providing patients with therapies that are safe, efficacious and meet high quality standards,” Douglas Cole, Takeda Pharmaceuticals President, said in a statement. “This new partnership will help enhance patient access to an important gout medicine by supplying Prasco with Colchicine Tablets, USP, manufactured under the same rigorous standards and processes as Colcrys.”

Prices for the Mitigare authorized generic and the Colcrys authorized generic have not been publicly announced. In an interview, West-Ward said it could not comment on exact savings to patients as savings will vary between insurance plans and pharmacy distribution channels.

“Our goal is to provide the most aggressive discounts on generic colchicine in the market with the intent for those discounts to be passed on to adult patients in need of treatment for the prophylaxis of gout flares,” Mr. Gavaris said.

At this article’s deadline, Takeda and Prasco had not responded to a question about the price of the generic Colcrys.

While rheumatologists expressed relief that generic colchicine products have finally become available, they also voiced concerns about potential barriers to access.

“I am proud of what the ACR did here and would hope that it serves as a model for future efforts by professional medical organizations to get into the (often legal) trenches and truly help their patients get affordable care. … [They] put their mouth where the money is and stood up for patients,” said Dr. Christopher M. Burns, a rheumatologist at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, N.H.

“I hope that this will, in fact, reduce the pricing for colchicine, and that it will not allow payers to add an onerous out-of-pocket cost for the drug far in excess of the cost if paid without utilizing pharmacy benefits,” said Dr. Norman B. Gaylis, a rheumatologist in private practice in Aventura, Fla.

Dr. St.Clair added that the future availability and cost of generic colchicine is not certain given common supply-and-demand problems that can arise with generic drugs.

“We have observed critical shortages of several generic medications during the past several years that have drastically affected medical therapy for many common conditions,” he said in an interview. “We will need to keep a close eye on the supply of generic colchicine to ensure it keeps up with the demand. The FDA and the pharmaceutical industry has an obligation to ensure that patients have access to these critical generic drugs.”

On Twitter @legal_med

After a 5-year monopoly on the sale of colchicine put the gout medication out of reach for many patients, a federal judge in January denied an injunction request by Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A. to halt the distribution of colchicine products by Hikma Pharmaceuticals PLC.

The availability of a generic colchicine will introduce competition into the marketplace and drive down costs, said Dr. E. William St.Clair, president of the American College of Rheumatology and chief of the division of rheumatology and immunology at Duke University, Durham, N.C. The ACR issued a friend-of-the-court brief to the federal district court in support of a generic colchicine product entering the market.