User login

Daily episodes of confusion • altered behavior • chronic sleep deprivation • Dx?

THE CASE

A 60-year-old man with hypertension, gout, hyperlipidemia, and chronic sleep deprivation was referred to our neurology department for evaluation because he’d recently developed episodes of confusion and altered behavior that occurred daily. According to the patient’s wife, these episodes had started 4 weeks earlier while the patient was driving. He drove off the road while staring ahead with a “Joker-like” smile on his face. He was unable to utter more than a few words or respond to his wife, who was able to safely bring the car to a stop. The patient had spotty memory of this 40-minute episode.

Since then, he’d had similar but shorter episodes each morning, 20 to 75 minutes after taking his prescribed medications (lisinopril, simvastatin, and allopurinol). According to the patient’s wife, during these episodes, the patient would “act childish.” He would develop a voracious appetite and experience double or distorted vision, an unsteady gait, and poor muscle tone. These episodes were always followed by a long nap.

The man denied drinking, head trauma, acute illness, or taking illicit substances or any medications other than lisinopril, simvastatin, and allopurinol. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography, carotid Doppler ultrasound, and routine and 24-hour ambulatory electroencephalography (EEG) were normal.

Before the patient was referred to our neurology department, he had been prescribed a short course of the antiepileptic/mood stabilizer valproate and the wakefulness agent armodafinil, but neither medication had helped. The patient’s episodes continued daily, usually 20 to 75 minutes after taking his regular medications. When he decided to take them at night, the episodes began to occur at night.

His neurologic exam was normal. Family history was positive for a cousin with narcolepsy but negative for seizures and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Polysomnography revealed moderate OSA with minimal oxygen desaturation. Inpatient video EEG monitoring captured several of the events that the patient and his wife had described; the patient seemed “uninhibited” in his behavior. His EEG, cardiac telemetry, oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and serum glucose level remained normal.

The episodes’ sudden onset, peculiar symptoms, and duration—and the fact that they occurred after he took his usual medications—made complex partial seizures unlikely. The patient’s chronic sleep deprivation and family history of narcolepsy raised the possibility of “sleep attacks,” but the sudden onset and age of onset of his symptoms made those conditions less likely to explain the complete clinical picture. No particular hormonal disturbance could explain his presentation, and blood work was normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Because the patient’s episodes had been occurring shortly after the patient took his lisinopril, simvastatin, and allopurinol, and because his blood pressure and lipid levels were normal and his gout was asymptomatic, we decided to stop these medications. Later that day, the patient reported that he had discovered that his vial of lisinopril, which he had obtained from his regular pharmacy the day before his first episode, contained a different medication. He consulted a pharmacist, who determined that the vial contained extended release zolpidem 12.5 mg, and not his antihypertensive.

DISCUSSION

Although the true incidence of medication errors is difficult to determine, a 2006 Institute of Medicine report estimated that there are at least 1.5 million cases of preventable adverse drug events in the United States each year.1 In light of these statistics, medication errors need to be near the top of our differential diagnosis when patients suddenly develop symptoms for which there is no obvious cause.

Cause to pause? If you observe a temporal association between the onset of a patient’s symptoms and medication administration, consider possible adverse effects of the medication before ordering tests.

In this case … Our patient’s peculiar presentation correlated with regular ingestion of a high dose of zolpidem, a short-acting non-benzodiazepine gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist. Zolpidem binds to the same GABAA receptor as benzodiazepines and therefore acts as a hypnotic by increasing GABA transmission.2 Neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with zolpidem include hallucinations, amnesia, parasomnia, psychomotor impairment, and complex behaviors (eg, sleepwalking or sleep-driving).2 Higher doses may cause coma or (rarely) death.2 One case report describes a patient who heard command hallucinations and stabbed himself after ingesting a large dose of zolpidem.3

Our patient

The patient’s episodes stopped after he discontinued the zolpidem. He subsequently received a correct prescription for lisinopril, and did not experience any additional episodes.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consider medication errors and adverse drug events in the differential diagnosis for patients who develop symptoms for which there is no obvious etiology. Educate patients, as well, to question their pharmacist if a recently filled prescription doesn’t look like the pill they usually take or makes them feel different than usual when they take it.

Of course, patients should be reminded that a generic medication may not always look the same as a brand-name drug or a previous generic prescription. But it can’t hurt for the patient to ask whether that medication that “looks different” is just a different generic—or a sign of a more worrisome mix-up.

1. Institute of Medicine. Preventing medication errors. Report Brief. July 2006. Institute of Medicine Web site. Available at: http://iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2006/Preventing-Medication-Errors-Quality-Chasm-Series/medicationerrorsnew.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2015.

2. Gunja N. The clinical and forensic toxicology of Z-drugs. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:155-162.

3. Manfredi G, Kotzalidis GD, Lazanio S, et al. Command hallucinations with self-stabbing associated with zolpidem overdose. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:92-93.

THE CASE

A 60-year-old man with hypertension, gout, hyperlipidemia, and chronic sleep deprivation was referred to our neurology department for evaluation because he’d recently developed episodes of confusion and altered behavior that occurred daily. According to the patient’s wife, these episodes had started 4 weeks earlier while the patient was driving. He drove off the road while staring ahead with a “Joker-like” smile on his face. He was unable to utter more than a few words or respond to his wife, who was able to safely bring the car to a stop. The patient had spotty memory of this 40-minute episode.

Since then, he’d had similar but shorter episodes each morning, 20 to 75 minutes after taking his prescribed medications (lisinopril, simvastatin, and allopurinol). According to the patient’s wife, during these episodes, the patient would “act childish.” He would develop a voracious appetite and experience double or distorted vision, an unsteady gait, and poor muscle tone. These episodes were always followed by a long nap.

The man denied drinking, head trauma, acute illness, or taking illicit substances or any medications other than lisinopril, simvastatin, and allopurinol. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography, carotid Doppler ultrasound, and routine and 24-hour ambulatory electroencephalography (EEG) were normal.

Before the patient was referred to our neurology department, he had been prescribed a short course of the antiepileptic/mood stabilizer valproate and the wakefulness agent armodafinil, but neither medication had helped. The patient’s episodes continued daily, usually 20 to 75 minutes after taking his regular medications. When he decided to take them at night, the episodes began to occur at night.

His neurologic exam was normal. Family history was positive for a cousin with narcolepsy but negative for seizures and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Polysomnography revealed moderate OSA with minimal oxygen desaturation. Inpatient video EEG monitoring captured several of the events that the patient and his wife had described; the patient seemed “uninhibited” in his behavior. His EEG, cardiac telemetry, oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and serum glucose level remained normal.

The episodes’ sudden onset, peculiar symptoms, and duration—and the fact that they occurred after he took his usual medications—made complex partial seizures unlikely. The patient’s chronic sleep deprivation and family history of narcolepsy raised the possibility of “sleep attacks,” but the sudden onset and age of onset of his symptoms made those conditions less likely to explain the complete clinical picture. No particular hormonal disturbance could explain his presentation, and blood work was normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Because the patient’s episodes had been occurring shortly after the patient took his lisinopril, simvastatin, and allopurinol, and because his blood pressure and lipid levels were normal and his gout was asymptomatic, we decided to stop these medications. Later that day, the patient reported that he had discovered that his vial of lisinopril, which he had obtained from his regular pharmacy the day before his first episode, contained a different medication. He consulted a pharmacist, who determined that the vial contained extended release zolpidem 12.5 mg, and not his antihypertensive.

DISCUSSION

Although the true incidence of medication errors is difficult to determine, a 2006 Institute of Medicine report estimated that there are at least 1.5 million cases of preventable adverse drug events in the United States each year.1 In light of these statistics, medication errors need to be near the top of our differential diagnosis when patients suddenly develop symptoms for which there is no obvious cause.

Cause to pause? If you observe a temporal association between the onset of a patient’s symptoms and medication administration, consider possible adverse effects of the medication before ordering tests.

In this case … Our patient’s peculiar presentation correlated with regular ingestion of a high dose of zolpidem, a short-acting non-benzodiazepine gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist. Zolpidem binds to the same GABAA receptor as benzodiazepines and therefore acts as a hypnotic by increasing GABA transmission.2 Neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with zolpidem include hallucinations, amnesia, parasomnia, psychomotor impairment, and complex behaviors (eg, sleepwalking or sleep-driving).2 Higher doses may cause coma or (rarely) death.2 One case report describes a patient who heard command hallucinations and stabbed himself after ingesting a large dose of zolpidem.3

Our patient

The patient’s episodes stopped after he discontinued the zolpidem. He subsequently received a correct prescription for lisinopril, and did not experience any additional episodes.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consider medication errors and adverse drug events in the differential diagnosis for patients who develop symptoms for which there is no obvious etiology. Educate patients, as well, to question their pharmacist if a recently filled prescription doesn’t look like the pill they usually take or makes them feel different than usual when they take it.

Of course, patients should be reminded that a generic medication may not always look the same as a brand-name drug or a previous generic prescription. But it can’t hurt for the patient to ask whether that medication that “looks different” is just a different generic—or a sign of a more worrisome mix-up.

THE CASE

A 60-year-old man with hypertension, gout, hyperlipidemia, and chronic sleep deprivation was referred to our neurology department for evaluation because he’d recently developed episodes of confusion and altered behavior that occurred daily. According to the patient’s wife, these episodes had started 4 weeks earlier while the patient was driving. He drove off the road while staring ahead with a “Joker-like” smile on his face. He was unable to utter more than a few words or respond to his wife, who was able to safely bring the car to a stop. The patient had spotty memory of this 40-minute episode.

Since then, he’d had similar but shorter episodes each morning, 20 to 75 minutes after taking his prescribed medications (lisinopril, simvastatin, and allopurinol). According to the patient’s wife, during these episodes, the patient would “act childish.” He would develop a voracious appetite and experience double or distorted vision, an unsteady gait, and poor muscle tone. These episodes were always followed by a long nap.

The man denied drinking, head trauma, acute illness, or taking illicit substances or any medications other than lisinopril, simvastatin, and allopurinol. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography, carotid Doppler ultrasound, and routine and 24-hour ambulatory electroencephalography (EEG) were normal.

Before the patient was referred to our neurology department, he had been prescribed a short course of the antiepileptic/mood stabilizer valproate and the wakefulness agent armodafinil, but neither medication had helped. The patient’s episodes continued daily, usually 20 to 75 minutes after taking his regular medications. When he decided to take them at night, the episodes began to occur at night.

His neurologic exam was normal. Family history was positive for a cousin with narcolepsy but negative for seizures and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Polysomnography revealed moderate OSA with minimal oxygen desaturation. Inpatient video EEG monitoring captured several of the events that the patient and his wife had described; the patient seemed “uninhibited” in his behavior. His EEG, cardiac telemetry, oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and serum glucose level remained normal.

The episodes’ sudden onset, peculiar symptoms, and duration—and the fact that they occurred after he took his usual medications—made complex partial seizures unlikely. The patient’s chronic sleep deprivation and family history of narcolepsy raised the possibility of “sleep attacks,” but the sudden onset and age of onset of his symptoms made those conditions less likely to explain the complete clinical picture. No particular hormonal disturbance could explain his presentation, and blood work was normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Because the patient’s episodes had been occurring shortly after the patient took his lisinopril, simvastatin, and allopurinol, and because his blood pressure and lipid levels were normal and his gout was asymptomatic, we decided to stop these medications. Later that day, the patient reported that he had discovered that his vial of lisinopril, which he had obtained from his regular pharmacy the day before his first episode, contained a different medication. He consulted a pharmacist, who determined that the vial contained extended release zolpidem 12.5 mg, and not his antihypertensive.

DISCUSSION

Although the true incidence of medication errors is difficult to determine, a 2006 Institute of Medicine report estimated that there are at least 1.5 million cases of preventable adverse drug events in the United States each year.1 In light of these statistics, medication errors need to be near the top of our differential diagnosis when patients suddenly develop symptoms for which there is no obvious cause.

Cause to pause? If you observe a temporal association between the onset of a patient’s symptoms and medication administration, consider possible adverse effects of the medication before ordering tests.

In this case … Our patient’s peculiar presentation correlated with regular ingestion of a high dose of zolpidem, a short-acting non-benzodiazepine gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist. Zolpidem binds to the same GABAA receptor as benzodiazepines and therefore acts as a hypnotic by increasing GABA transmission.2 Neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with zolpidem include hallucinations, amnesia, parasomnia, psychomotor impairment, and complex behaviors (eg, sleepwalking or sleep-driving).2 Higher doses may cause coma or (rarely) death.2 One case report describes a patient who heard command hallucinations and stabbed himself after ingesting a large dose of zolpidem.3

Our patient

The patient’s episodes stopped after he discontinued the zolpidem. He subsequently received a correct prescription for lisinopril, and did not experience any additional episodes.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consider medication errors and adverse drug events in the differential diagnosis for patients who develop symptoms for which there is no obvious etiology. Educate patients, as well, to question their pharmacist if a recently filled prescription doesn’t look like the pill they usually take or makes them feel different than usual when they take it.

Of course, patients should be reminded that a generic medication may not always look the same as a brand-name drug or a previous generic prescription. But it can’t hurt for the patient to ask whether that medication that “looks different” is just a different generic—or a sign of a more worrisome mix-up.

1. Institute of Medicine. Preventing medication errors. Report Brief. July 2006. Institute of Medicine Web site. Available at: http://iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2006/Preventing-Medication-Errors-Quality-Chasm-Series/medicationerrorsnew.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2015.

2. Gunja N. The clinical and forensic toxicology of Z-drugs. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:155-162.

3. Manfredi G, Kotzalidis GD, Lazanio S, et al. Command hallucinations with self-stabbing associated with zolpidem overdose. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:92-93.

1. Institute of Medicine. Preventing medication errors. Report Brief. July 2006. Institute of Medicine Web site. Available at: http://iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2006/Preventing-Medication-Errors-Quality-Chasm-Series/medicationerrorsnew.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2015.

2. Gunja N. The clinical and forensic toxicology of Z-drugs. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:155-162.

3. Manfredi G, Kotzalidis GD, Lazanio S, et al. Command hallucinations with self-stabbing associated with zolpidem overdose. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:92-93.

Is red-yeast rice a safe and effective alternative to statins?

Yes, but perhaps not the red-yeast rice extracts available in the United States.

In patients with known coronary artery disease and dyslipidemia (secondary prevention), therapy with red-yeast rice extract containing naturally-occurring lovastatin is associated with a 30% reduction in coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and a 60% reduction in myocardial infarction (MI), similar to the effect of statin medications (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] in China).

In patients older than 65 years with hypertension and a previous MI, the rate of adverse effects from lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice is 2.1% (SOR: B, RCT in China).

In patients with previous statin intolerance, the rates of myalgias and treatment discontinuation with lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice therapy are similar to either placebo or another statin (SOR: C, low-powered RCTs).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t allow lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice products on the US market; physicians should be aware that products purchased by patients online contain variable amounts of lovastatin.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Red-yeast rice is a Chinese dietary and medicinal product of yeast (Monascus purpureus) grown on rice. It contains a wide range of biologically active compounds, including lovastatin (monacolin K). The FDA has banned the sale of red-yeast rice products with more than trace amounts of lovastatin.1

Red-yeast rice beats placebo, similar to statins

A systematic review of 22 RCTs (N=6520), primarily conducted in China using 600 to 2400 mg red-yeast rice extract daily (lovastatin content 5-20 mg), assessed outcomes in patients with known CHD and dyslipidemia.2 In one trial of 4870 patients, users of red-yeast rice had significant reductions in CHD mortality (relative risk [RR]=0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.89), incidence of MI (RR=0.39; 95% CI, 0.28-0.55), and revascularization (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.50-0.89) compared with placebo users.

However, when compared with statin therapy, red-yeast rice didn’t yield statistically significant differences in CHD mortality (2 trials, N=220; RR=0.26; 95% CI, 0.06-1.21), incidence of MI (1 trial, N=84; RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.30-3.05) or revascularization (1 trial, N=84; RR=1.14; 95% CI, 0.38-3.46).

Red-yeast rice outperforms placebo in CHD and MI—but not stroke

A secondary analysis of an RCT evaluated the impact of red-yeast rice extract (600 mg twice a day) for 4.5 years on cardiovascular events and mortality in 1530 Chinese patients 60 years of age and older with hypertension and a previous MI.3 The lovastatin content of the red-yeast rice was 5 to 6.4 mg/d.

Compared with placebo, red-yeast rice was associated with a lower incidence of CHD events (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.36-0.83), nonfatal MI (RR=0.48; 95% CI, 0.37-0.71), and all-cause mortality (RR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83) but not with a statistically significant difference in stroke (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-1.09) or cardiac revascularization (RR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-1.19).

Total adverse events in this study were similar for red-yeast rice and placebo (2.1% vs 1.2%, respectively; P>.05). They included gastrointestinal discomfort, allergic reactions, myalgias, edema, erectile dysfunction, and neuropsychological symptoms.

Red-yeast rice is similar to placebo or another statin in statin-induced myalgia

In a small community-based trial of 62 adults with dyslipidemia and a history of statin-induced myalgia, investigators randomized patients to receive either red-yeast rice extract at 1800 mg (with 3.1 mg lovastatin) or placebo twice daily for 24 weeks.4 Patients’ weekly self-reports of pain (on a 10-point scale) were skewed at baseline (1.4 in the red-yeast rice group vs 2.6 in the placebo group; P=.026) but similar at 12 weeks (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.9 with placebo; P=.30) and 24 weeks (1.2 with red-yeast rice vs 2.0 with placebo; P=.120).

An RCT of 43 adults with dyslipidemia and history of statin intolerance compared red-yeast rice extract (2400 mg, with 10 mg lovastatin) with pravastatin (20 mg) dosed twice a day.5 At the end of 12 weeks, mean self-reported pain scores (on a 10-point scale) were similar (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.1 with pravastatin; P=.82), as were discontinuation rates because of myalgia (5% with red-yeast rice vs 9% with pravastatin; P=.99).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A narrative review of alternative therapies for heart failure and hypercholesterolemia states that red yeast rice may be a cost-saving option for hypercholesterolemia in patients who can’t afford other medications (purchased mostly online, cost $8-$20/month for a dosage equivalent to lovastatin 20 mg/d).6

A ConsumerLab review of red yeast rice products available since the FDA ban in 2011 tested products marketed in the United States and found variable amounts of lovastatin.1,7 The group determined that labeling was a poor guide to lovastatin content, which ranged from 0 to 20 mg per daily dose, and that the products may not have been standardized. The group concluded that therapeutic effects weren’t predictable.

1. National Institutes of Health. Red yeast rice: An introduction. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Web site. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/redyeastrice. Accessed October 28, 2013.

2. Shang Q, Liu Z, Chen K, et al. A systematic review of xuezhikang, an extract from red yeast rice, for coronary heart disease complicated by dyslipidemia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:636547.

3. Li JJ, Lu ZL, Kou WR, et al. Beneficial impact of xuezhikang on cardiovascular events and mortality in elderly hypertensive patients with previous myocardial infarction from the China Coronary Secondary Prevention Study (CCSPS). J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:947-956.

4. Becker DJ, Gordon RY, Halbert SC, et al. Red yeast rice for dyslipidemia in statin-intolerant patients: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:830-839,

W147-W149.

5. Halbert SC, French B, Gordon RY, et al. Tolerability of red yeast rice (2,400 mg twice daily) versus pravastatin (20 mg twice daily) in patients with previous statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:198-204.

6. Morelli V, Zoorob RJ. Alternative therapies: Part II. Congestive heart failure and hypercholesterolemia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:1325-1330.

7. Consumerlab.com. Product Review: Red yeast rice supplements review. ConsumerLab Web site. Available at: https://www.consumerlab.com/reviews/Red-Yeast-Rice-Supplements-Review/Red_Yeast_Rice. Accessed January 20, 2015.

Yes, but perhaps not the red-yeast rice extracts available in the United States.

In patients with known coronary artery disease and dyslipidemia (secondary prevention), therapy with red-yeast rice extract containing naturally-occurring lovastatin is associated with a 30% reduction in coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and a 60% reduction in myocardial infarction (MI), similar to the effect of statin medications (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] in China).

In patients older than 65 years with hypertension and a previous MI, the rate of adverse effects from lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice is 2.1% (SOR: B, RCT in China).

In patients with previous statin intolerance, the rates of myalgias and treatment discontinuation with lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice therapy are similar to either placebo or another statin (SOR: C, low-powered RCTs).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t allow lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice products on the US market; physicians should be aware that products purchased by patients online contain variable amounts of lovastatin.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Red-yeast rice is a Chinese dietary and medicinal product of yeast (Monascus purpureus) grown on rice. It contains a wide range of biologically active compounds, including lovastatin (monacolin K). The FDA has banned the sale of red-yeast rice products with more than trace amounts of lovastatin.1

Red-yeast rice beats placebo, similar to statins

A systematic review of 22 RCTs (N=6520), primarily conducted in China using 600 to 2400 mg red-yeast rice extract daily (lovastatin content 5-20 mg), assessed outcomes in patients with known CHD and dyslipidemia.2 In one trial of 4870 patients, users of red-yeast rice had significant reductions in CHD mortality (relative risk [RR]=0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.89), incidence of MI (RR=0.39; 95% CI, 0.28-0.55), and revascularization (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.50-0.89) compared with placebo users.

However, when compared with statin therapy, red-yeast rice didn’t yield statistically significant differences in CHD mortality (2 trials, N=220; RR=0.26; 95% CI, 0.06-1.21), incidence of MI (1 trial, N=84; RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.30-3.05) or revascularization (1 trial, N=84; RR=1.14; 95% CI, 0.38-3.46).

Red-yeast rice outperforms placebo in CHD and MI—but not stroke

A secondary analysis of an RCT evaluated the impact of red-yeast rice extract (600 mg twice a day) for 4.5 years on cardiovascular events and mortality in 1530 Chinese patients 60 years of age and older with hypertension and a previous MI.3 The lovastatin content of the red-yeast rice was 5 to 6.4 mg/d.

Compared with placebo, red-yeast rice was associated with a lower incidence of CHD events (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.36-0.83), nonfatal MI (RR=0.48; 95% CI, 0.37-0.71), and all-cause mortality (RR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83) but not with a statistically significant difference in stroke (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-1.09) or cardiac revascularization (RR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-1.19).

Total adverse events in this study were similar for red-yeast rice and placebo (2.1% vs 1.2%, respectively; P>.05). They included gastrointestinal discomfort, allergic reactions, myalgias, edema, erectile dysfunction, and neuropsychological symptoms.

Red-yeast rice is similar to placebo or another statin in statin-induced myalgia

In a small community-based trial of 62 adults with dyslipidemia and a history of statin-induced myalgia, investigators randomized patients to receive either red-yeast rice extract at 1800 mg (with 3.1 mg lovastatin) or placebo twice daily for 24 weeks.4 Patients’ weekly self-reports of pain (on a 10-point scale) were skewed at baseline (1.4 in the red-yeast rice group vs 2.6 in the placebo group; P=.026) but similar at 12 weeks (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.9 with placebo; P=.30) and 24 weeks (1.2 with red-yeast rice vs 2.0 with placebo; P=.120).

An RCT of 43 adults with dyslipidemia and history of statin intolerance compared red-yeast rice extract (2400 mg, with 10 mg lovastatin) with pravastatin (20 mg) dosed twice a day.5 At the end of 12 weeks, mean self-reported pain scores (on a 10-point scale) were similar (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.1 with pravastatin; P=.82), as were discontinuation rates because of myalgia (5% with red-yeast rice vs 9% with pravastatin; P=.99).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A narrative review of alternative therapies for heart failure and hypercholesterolemia states that red yeast rice may be a cost-saving option for hypercholesterolemia in patients who can’t afford other medications (purchased mostly online, cost $8-$20/month for a dosage equivalent to lovastatin 20 mg/d).6

A ConsumerLab review of red yeast rice products available since the FDA ban in 2011 tested products marketed in the United States and found variable amounts of lovastatin.1,7 The group determined that labeling was a poor guide to lovastatin content, which ranged from 0 to 20 mg per daily dose, and that the products may not have been standardized. The group concluded that therapeutic effects weren’t predictable.

Yes, but perhaps not the red-yeast rice extracts available in the United States.

In patients with known coronary artery disease and dyslipidemia (secondary prevention), therapy with red-yeast rice extract containing naturally-occurring lovastatin is associated with a 30% reduction in coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and a 60% reduction in myocardial infarction (MI), similar to the effect of statin medications (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] in China).

In patients older than 65 years with hypertension and a previous MI, the rate of adverse effects from lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice is 2.1% (SOR: B, RCT in China).

In patients with previous statin intolerance, the rates of myalgias and treatment discontinuation with lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice therapy are similar to either placebo or another statin (SOR: C, low-powered RCTs).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t allow lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice products on the US market; physicians should be aware that products purchased by patients online contain variable amounts of lovastatin.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Red-yeast rice is a Chinese dietary and medicinal product of yeast (Monascus purpureus) grown on rice. It contains a wide range of biologically active compounds, including lovastatin (monacolin K). The FDA has banned the sale of red-yeast rice products with more than trace amounts of lovastatin.1

Red-yeast rice beats placebo, similar to statins

A systematic review of 22 RCTs (N=6520), primarily conducted in China using 600 to 2400 mg red-yeast rice extract daily (lovastatin content 5-20 mg), assessed outcomes in patients with known CHD and dyslipidemia.2 In one trial of 4870 patients, users of red-yeast rice had significant reductions in CHD mortality (relative risk [RR]=0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.89), incidence of MI (RR=0.39; 95% CI, 0.28-0.55), and revascularization (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.50-0.89) compared with placebo users.

However, when compared with statin therapy, red-yeast rice didn’t yield statistically significant differences in CHD mortality (2 trials, N=220; RR=0.26; 95% CI, 0.06-1.21), incidence of MI (1 trial, N=84; RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.30-3.05) or revascularization (1 trial, N=84; RR=1.14; 95% CI, 0.38-3.46).

Red-yeast rice outperforms placebo in CHD and MI—but not stroke

A secondary analysis of an RCT evaluated the impact of red-yeast rice extract (600 mg twice a day) for 4.5 years on cardiovascular events and mortality in 1530 Chinese patients 60 years of age and older with hypertension and a previous MI.3 The lovastatin content of the red-yeast rice was 5 to 6.4 mg/d.

Compared with placebo, red-yeast rice was associated with a lower incidence of CHD events (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.36-0.83), nonfatal MI (RR=0.48; 95% CI, 0.37-0.71), and all-cause mortality (RR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83) but not with a statistically significant difference in stroke (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-1.09) or cardiac revascularization (RR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-1.19).

Total adverse events in this study were similar for red-yeast rice and placebo (2.1% vs 1.2%, respectively; P>.05). They included gastrointestinal discomfort, allergic reactions, myalgias, edema, erectile dysfunction, and neuropsychological symptoms.

Red-yeast rice is similar to placebo or another statin in statin-induced myalgia

In a small community-based trial of 62 adults with dyslipidemia and a history of statin-induced myalgia, investigators randomized patients to receive either red-yeast rice extract at 1800 mg (with 3.1 mg lovastatin) or placebo twice daily for 24 weeks.4 Patients’ weekly self-reports of pain (on a 10-point scale) were skewed at baseline (1.4 in the red-yeast rice group vs 2.6 in the placebo group; P=.026) but similar at 12 weeks (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.9 with placebo; P=.30) and 24 weeks (1.2 with red-yeast rice vs 2.0 with placebo; P=.120).

An RCT of 43 adults with dyslipidemia and history of statin intolerance compared red-yeast rice extract (2400 mg, with 10 mg lovastatin) with pravastatin (20 mg) dosed twice a day.5 At the end of 12 weeks, mean self-reported pain scores (on a 10-point scale) were similar (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.1 with pravastatin; P=.82), as were discontinuation rates because of myalgia (5% with red-yeast rice vs 9% with pravastatin; P=.99).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A narrative review of alternative therapies for heart failure and hypercholesterolemia states that red yeast rice may be a cost-saving option for hypercholesterolemia in patients who can’t afford other medications (purchased mostly online, cost $8-$20/month for a dosage equivalent to lovastatin 20 mg/d).6

A ConsumerLab review of red yeast rice products available since the FDA ban in 2011 tested products marketed in the United States and found variable amounts of lovastatin.1,7 The group determined that labeling was a poor guide to lovastatin content, which ranged from 0 to 20 mg per daily dose, and that the products may not have been standardized. The group concluded that therapeutic effects weren’t predictable.

1. National Institutes of Health. Red yeast rice: An introduction. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Web site. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/redyeastrice. Accessed October 28, 2013.

2. Shang Q, Liu Z, Chen K, et al. A systematic review of xuezhikang, an extract from red yeast rice, for coronary heart disease complicated by dyslipidemia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:636547.

3. Li JJ, Lu ZL, Kou WR, et al. Beneficial impact of xuezhikang on cardiovascular events and mortality in elderly hypertensive patients with previous myocardial infarction from the China Coronary Secondary Prevention Study (CCSPS). J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:947-956.

4. Becker DJ, Gordon RY, Halbert SC, et al. Red yeast rice for dyslipidemia in statin-intolerant patients: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:830-839,

W147-W149.

5. Halbert SC, French B, Gordon RY, et al. Tolerability of red yeast rice (2,400 mg twice daily) versus pravastatin (20 mg twice daily) in patients with previous statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:198-204.

6. Morelli V, Zoorob RJ. Alternative therapies: Part II. Congestive heart failure and hypercholesterolemia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:1325-1330.

7. Consumerlab.com. Product Review: Red yeast rice supplements review. ConsumerLab Web site. Available at: https://www.consumerlab.com/reviews/Red-Yeast-Rice-Supplements-Review/Red_Yeast_Rice. Accessed January 20, 2015.

1. National Institutes of Health. Red yeast rice: An introduction. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Web site. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/redyeastrice. Accessed October 28, 2013.

2. Shang Q, Liu Z, Chen K, et al. A systematic review of xuezhikang, an extract from red yeast rice, for coronary heart disease complicated by dyslipidemia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:636547.

3. Li JJ, Lu ZL, Kou WR, et al. Beneficial impact of xuezhikang on cardiovascular events and mortality in elderly hypertensive patients with previous myocardial infarction from the China Coronary Secondary Prevention Study (CCSPS). J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:947-956.

4. Becker DJ, Gordon RY, Halbert SC, et al. Red yeast rice for dyslipidemia in statin-intolerant patients: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:830-839,

W147-W149.

5. Halbert SC, French B, Gordon RY, et al. Tolerability of red yeast rice (2,400 mg twice daily) versus pravastatin (20 mg twice daily) in patients with previous statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:198-204.

6. Morelli V, Zoorob RJ. Alternative therapies: Part II. Congestive heart failure and hypercholesterolemia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:1325-1330.

7. Consumerlab.com. Product Review: Red yeast rice supplements review. ConsumerLab Web site. Available at: https://www.consumerlab.com/reviews/Red-Yeast-Rice-Supplements-Review/Red_Yeast_Rice. Accessed January 20, 2015.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Does frenotomy help infants with tongue-tie overcome breastfeeding difficulties?

Probably not. No evidence exists for improved latching after frenotomy, and evidence concerning improvements in maternal comfort is conflicting. At best, frenotomy improves maternal nipple pain by 10% and maternal subjective sense of improvement over the short term (0 to 2 weeks) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with conflicting results for maternal nipple pain and overall feeding).

No studies have evaluated outcomes such as infant weight gain following frenotomy.

Experts don’t recommend frenotomy unless a clear association exists between ankyloglossia (tongue-tie) and breastfeeding problems. Frenotomy should be performed with anesthesia by an experienced clinician to minimize the risk of complications (SOR: C, a practice guideline.)

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Two RCTs found short-term (0-14 days) improvement in breastfeeding after frenotomy. One, which evaluated the effect of frenotomy on infants with significant ankyloglossia and breastfeeding difficulties, found short-term improvement in maternal nipple pain. Investigators randomized 58 infants (mean age 6 days) with ankyloglossia (rated 8 out of 10 on a standardized severity scale) to receive either frenotomy or no intervention.1 They used the 50-point Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire to measure maternal nipple pain at baseline, immediately after, and at 2, 4, 8, and 52 weeks.

Mothers in the intervention group reported a 10% greater reduction in nipple pain after frenotomy compared with the control group (11 points vs 6 points; P=.001). The improvement persisted at 2 weeks (graphic representation in study, P value not supplied) but not at 4 weeks or beyond.

An earlier, unblinded RCT randomized 40 infants (mean age 14 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems to frenotomy or lactation support.2 It found maternal subjective ratings of “improvement” (not quantified) by telephone interview at 24 hours (85% vs 3%; P<.01). Investigators performed frenotomy on all 19 of the unimproved control infants at 48 hours.

Frenotomy doesn’t improve breastfeeding overall

Two newer RCTs evaluating frenotomy and LATCH (Latch, Audible swallowing, nipple Type, Comfort, and Hold) scores, which include a component measuring maternal comfort, found no breastfeeding improvements. (LATCH is a validated 10-point score with moderate predictive value for identifying mothers at risk for early weaning because of sore nipples.3)

A double-blind RCT that assessed frenotomy in 57 infants (mean age 32 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems (severity of both unspecified) found no improvement in breastfeeding overall or nipple pain.4 Investigators randomized infants to frenotomy or sham frenotomy and used independent observers to measure outcomes with the LATCH score and the Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (IBFAT), a standardized method of assessing overall feeding.

They observed no significant differences in LATCH or IBFAT scores between groups. More mothers in the frenotomy group reported improved breastfeeding, but most were able to determine whether their baby had undergone frenotomy.

A single-blinded, RCT of early frenotomy in 107 younger infants with breastfeeding difficulties and mild to moderate ankyloglossia also found no improvement in LATCH scores.5 Researchers randomized infants younger than 2 weeks (blinded to researchers and unblinded to mothers) to either immediate frenotomy or standard care. They measured LATCH scores at baseline and after 5 days (by intention to treat).

Investigators found no difference in LATCH scores at 5 days postfrenotomy (pretreatment score 6.4 ± 2.3, posttreatment 6.8 ± 2.0; not significant).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2011 position statement from the Community Paediatrics Committee of the Canadian Paediatric Society notes that ankyloglossia is a relatively uncommon congenital anomaly, and associations between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems in infants have been inconsistent.6 For these reasons, the Committee doesn’t recommend frenotomy.

However, if the clinician deems surgical intervention necessary based on a clear association between significant tongue-tie and major breastfeeding problems, then frenotomy should be performed by a clinician experienced in the procedure and with appropriate analgesia. The Committee states that although ankyloglossia release appears to be a minor procedure, it may cause complications such as bleeding, infection, or injury to the Wharton’s duct.

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, a worldwide organization of physicians dedicated to the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding and human lactation, is currently revising its guidelines on neonatal ankyloglossia.7

1. Buryk M, Bloom D, Shope T. Efficacy of neonatal release of ankyloglossia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2011;128:280-288.

2. Hogan M, Westcott C, Griffiths M. Randomized, controlled trial of division of tongue-tie in infants with feeding problems. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:246-250.

3. Emond A, Ingram J, Johnson D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of early frenotomy in breastfed infants with mild-moderate tongue-tie. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F189-F195.

4. Berry J, Griffiths M, Westcott C. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of tongue-tie division and its immediate effect on breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:189-193.

5. Riordan J, Bibb D, Miller M, et al. Predicting breastfeeding duration using the LATCH breastfeeding assessment tool. J Hum Lact. 2001;17:20-23.

6. Rowan-Legg A. Ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:222.

7. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. Statements. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Web site. Available at: www.bfmed.org/Resources/Protocols.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2015.

Probably not. No evidence exists for improved latching after frenotomy, and evidence concerning improvements in maternal comfort is conflicting. At best, frenotomy improves maternal nipple pain by 10% and maternal subjective sense of improvement over the short term (0 to 2 weeks) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with conflicting results for maternal nipple pain and overall feeding).

No studies have evaluated outcomes such as infant weight gain following frenotomy.

Experts don’t recommend frenotomy unless a clear association exists between ankyloglossia (tongue-tie) and breastfeeding problems. Frenotomy should be performed with anesthesia by an experienced clinician to minimize the risk of complications (SOR: C, a practice guideline.)

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Two RCTs found short-term (0-14 days) improvement in breastfeeding after frenotomy. One, which evaluated the effect of frenotomy on infants with significant ankyloglossia and breastfeeding difficulties, found short-term improvement in maternal nipple pain. Investigators randomized 58 infants (mean age 6 days) with ankyloglossia (rated 8 out of 10 on a standardized severity scale) to receive either frenotomy or no intervention.1 They used the 50-point Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire to measure maternal nipple pain at baseline, immediately after, and at 2, 4, 8, and 52 weeks.

Mothers in the intervention group reported a 10% greater reduction in nipple pain after frenotomy compared with the control group (11 points vs 6 points; P=.001). The improvement persisted at 2 weeks (graphic representation in study, P value not supplied) but not at 4 weeks or beyond.

An earlier, unblinded RCT randomized 40 infants (mean age 14 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems to frenotomy or lactation support.2 It found maternal subjective ratings of “improvement” (not quantified) by telephone interview at 24 hours (85% vs 3%; P<.01). Investigators performed frenotomy on all 19 of the unimproved control infants at 48 hours.

Frenotomy doesn’t improve breastfeeding overall

Two newer RCTs evaluating frenotomy and LATCH (Latch, Audible swallowing, nipple Type, Comfort, and Hold) scores, which include a component measuring maternal comfort, found no breastfeeding improvements. (LATCH is a validated 10-point score with moderate predictive value for identifying mothers at risk for early weaning because of sore nipples.3)

A double-blind RCT that assessed frenotomy in 57 infants (mean age 32 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems (severity of both unspecified) found no improvement in breastfeeding overall or nipple pain.4 Investigators randomized infants to frenotomy or sham frenotomy and used independent observers to measure outcomes with the LATCH score and the Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (IBFAT), a standardized method of assessing overall feeding.

They observed no significant differences in LATCH or IBFAT scores between groups. More mothers in the frenotomy group reported improved breastfeeding, but most were able to determine whether their baby had undergone frenotomy.

A single-blinded, RCT of early frenotomy in 107 younger infants with breastfeeding difficulties and mild to moderate ankyloglossia also found no improvement in LATCH scores.5 Researchers randomized infants younger than 2 weeks (blinded to researchers and unblinded to mothers) to either immediate frenotomy or standard care. They measured LATCH scores at baseline and after 5 days (by intention to treat).

Investigators found no difference in LATCH scores at 5 days postfrenotomy (pretreatment score 6.4 ± 2.3, posttreatment 6.8 ± 2.0; not significant).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2011 position statement from the Community Paediatrics Committee of the Canadian Paediatric Society notes that ankyloglossia is a relatively uncommon congenital anomaly, and associations between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems in infants have been inconsistent.6 For these reasons, the Committee doesn’t recommend frenotomy.

However, if the clinician deems surgical intervention necessary based on a clear association between significant tongue-tie and major breastfeeding problems, then frenotomy should be performed by a clinician experienced in the procedure and with appropriate analgesia. The Committee states that although ankyloglossia release appears to be a minor procedure, it may cause complications such as bleeding, infection, or injury to the Wharton’s duct.

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, a worldwide organization of physicians dedicated to the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding and human lactation, is currently revising its guidelines on neonatal ankyloglossia.7

Probably not. No evidence exists for improved latching after frenotomy, and evidence concerning improvements in maternal comfort is conflicting. At best, frenotomy improves maternal nipple pain by 10% and maternal subjective sense of improvement over the short term (0 to 2 weeks) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with conflicting results for maternal nipple pain and overall feeding).

No studies have evaluated outcomes such as infant weight gain following frenotomy.

Experts don’t recommend frenotomy unless a clear association exists between ankyloglossia (tongue-tie) and breastfeeding problems. Frenotomy should be performed with anesthesia by an experienced clinician to minimize the risk of complications (SOR: C, a practice guideline.)

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Two RCTs found short-term (0-14 days) improvement in breastfeeding after frenotomy. One, which evaluated the effect of frenotomy on infants with significant ankyloglossia and breastfeeding difficulties, found short-term improvement in maternal nipple pain. Investigators randomized 58 infants (mean age 6 days) with ankyloglossia (rated 8 out of 10 on a standardized severity scale) to receive either frenotomy or no intervention.1 They used the 50-point Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire to measure maternal nipple pain at baseline, immediately after, and at 2, 4, 8, and 52 weeks.

Mothers in the intervention group reported a 10% greater reduction in nipple pain after frenotomy compared with the control group (11 points vs 6 points; P=.001). The improvement persisted at 2 weeks (graphic representation in study, P value not supplied) but not at 4 weeks or beyond.

An earlier, unblinded RCT randomized 40 infants (mean age 14 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems to frenotomy or lactation support.2 It found maternal subjective ratings of “improvement” (not quantified) by telephone interview at 24 hours (85% vs 3%; P<.01). Investigators performed frenotomy on all 19 of the unimproved control infants at 48 hours.

Frenotomy doesn’t improve breastfeeding overall

Two newer RCTs evaluating frenotomy and LATCH (Latch, Audible swallowing, nipple Type, Comfort, and Hold) scores, which include a component measuring maternal comfort, found no breastfeeding improvements. (LATCH is a validated 10-point score with moderate predictive value for identifying mothers at risk for early weaning because of sore nipples.3)

A double-blind RCT that assessed frenotomy in 57 infants (mean age 32 days) with ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems (severity of both unspecified) found no improvement in breastfeeding overall or nipple pain.4 Investigators randomized infants to frenotomy or sham frenotomy and used independent observers to measure outcomes with the LATCH score and the Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (IBFAT), a standardized method of assessing overall feeding.

They observed no significant differences in LATCH or IBFAT scores between groups. More mothers in the frenotomy group reported improved breastfeeding, but most were able to determine whether their baby had undergone frenotomy.

A single-blinded, RCT of early frenotomy in 107 younger infants with breastfeeding difficulties and mild to moderate ankyloglossia also found no improvement in LATCH scores.5 Researchers randomized infants younger than 2 weeks (blinded to researchers and unblinded to mothers) to either immediate frenotomy or standard care. They measured LATCH scores at baseline and after 5 days (by intention to treat).

Investigators found no difference in LATCH scores at 5 days postfrenotomy (pretreatment score 6.4 ± 2.3, posttreatment 6.8 ± 2.0; not significant).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A 2011 position statement from the Community Paediatrics Committee of the Canadian Paediatric Society notes that ankyloglossia is a relatively uncommon congenital anomaly, and associations between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding problems in infants have been inconsistent.6 For these reasons, the Committee doesn’t recommend frenotomy.

However, if the clinician deems surgical intervention necessary based on a clear association between significant tongue-tie and major breastfeeding problems, then frenotomy should be performed by a clinician experienced in the procedure and with appropriate analgesia. The Committee states that although ankyloglossia release appears to be a minor procedure, it may cause complications such as bleeding, infection, or injury to the Wharton’s duct.

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, a worldwide organization of physicians dedicated to the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding and human lactation, is currently revising its guidelines on neonatal ankyloglossia.7

1. Buryk M, Bloom D, Shope T. Efficacy of neonatal release of ankyloglossia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2011;128:280-288.

2. Hogan M, Westcott C, Griffiths M. Randomized, controlled trial of division of tongue-tie in infants with feeding problems. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:246-250.

3. Emond A, Ingram J, Johnson D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of early frenotomy in breastfed infants with mild-moderate tongue-tie. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F189-F195.

4. Berry J, Griffiths M, Westcott C. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of tongue-tie division and its immediate effect on breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:189-193.

5. Riordan J, Bibb D, Miller M, et al. Predicting breastfeeding duration using the LATCH breastfeeding assessment tool. J Hum Lact. 2001;17:20-23.

6. Rowan-Legg A. Ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:222.

7. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. Statements. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Web site. Available at: www.bfmed.org/Resources/Protocols.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2015.

1. Buryk M, Bloom D, Shope T. Efficacy of neonatal release of ankyloglossia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2011;128:280-288.

2. Hogan M, Westcott C, Griffiths M. Randomized, controlled trial of division of tongue-tie in infants with feeding problems. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:246-250.

3. Emond A, Ingram J, Johnson D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of early frenotomy in breastfed infants with mild-moderate tongue-tie. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:F189-F195.

4. Berry J, Griffiths M, Westcott C. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of tongue-tie division and its immediate effect on breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:189-193.

5. Riordan J, Bibb D, Miller M, et al. Predicting breastfeeding duration using the LATCH breastfeeding assessment tool. J Hum Lact. 2001;17:20-23.

6. Rowan-Legg A. Ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:222.

7. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. Statements. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Web site. Available at: www.bfmed.org/Resources/Protocols.aspx. Accessed January 10, 2015.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Does topical diclofenac relieve osteoarthritis pain?

Yes, at least in the short term. Topical diclofenac, with and without dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), modestly improves pain and function scores (by 4%-8%) for as long as 12 weeks in patients with osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of multiple randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Topical diclofenac modestly decreases pain scores in patients with OA of the hand in the short term (by 9% at 6 weeks) but no more than placebo at 8 weeks (SOR: B, RCT).

Both topical diclofenac with DMSO and oral diclofenac produce similar pain and function scores in patients with OA of the knee. In addition to minor skin dryness, topical diclofenac causes gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects in about a third of patients (SOR: B, RCT).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Diclofenac gel ($260-$330 per 150-mL bottle) and diclofenac with DMSO solution are the only topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) available in the United States.

Topical diclofenac with DMSO beats placebo

In a meta-analysis of 3 RCTs (697 patients, mean age 63.2, 37% male) with knee OA, topical diclofenac solution with DMSO (Pennsaid, 40 drops applied 4 times daily) demonstrated superiority to vehicle-controlled placebo at 4 to 12 weeks (mean 8.5 weeks) using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index.1 The WOMAC is a standardized patient questionnaire measuring 5 items for pain (score range 0-20), 2 for stiffness (score range 0-8), and 17 for functional limitation (score range 0-68).

Compared with placebo, topical diclofenac with DMSO resulted in 1.6 units greater reduction in pain (8% difference), 0.6 units greater reduction in stiffness (7.5% difference), and 5.5 units greater improvement in physical function (8% difference). Patients using diclofenac reported more minor skin dryness than patients using placebo (number needed to harm [NNH]=6).

Diclofenac gel is also effective, but may cause dermatitis

A pooled analysis of 3 12-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multicenter trials of 1426 patients with OA of the knee compared topical diclofenac gel (4 g applied 4 times a day) with vehicle placebo for patients older than 25 years and patients older than 65 years.2 Investigators evaluated 972 patients who suffered a symptom flare at 1, 4, 8, and 12 weeks after a one-week washout period.

Diclofenac demonstrated statistical superiority across all age groups when compared with placebo, based on pain and physical function measured on the WOMAC Index. Its effects were modest, however.

At 12 weeks, patients younger than 65 years showed pain improvement of -5.8 vs -4.7 for placebo (a 5.5% improvement on the 20-point scale) and improvement in physical function of -17.9 vs -14.2 (a 5.4% improvement on the 68-point scale). Patients older than 65 years demonstrated pain improvement of -5.3 vs -4.1 for placebo (6% improvement on the 20-point scale) and physical function improvement of -15.5 vs -11.0 for placebo (6.6% improvement on the 68-point scale).

Dermatitis was more common in the diclofenac groups, with a NNH of 30 in patients younger than 65 years and 19 in patients older than 65 years.

Diclofenac gel effectively treated hand OA for as long as 6 weeks in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 809 men and women older than 39 years. Pain scores on a 100-point visual analog scale improved when compared with placebo alone.3 At 6 weeks, topical diclofenac reduced pain scores by 45% compared with 36% for placebo (P=.023). Pain reductions also were greater in the diclofenac group at 8 weeks, although not statistically different.

Oral diclofenac works well, too, but has more GI adverse effects

An RCT of 622 patients (40-85 years of age) with symptomatic and radiographically diagnosed OA of the knee compared topical diclofenac solution (75 mg/d) with oral diclofenac (50 mg 3 times a day) and found similar efficacy at 12 weeks, with no significant difference between oral and topical preparations for pain, physical function, and stiffness measured with the WOMAC Index (P=.23, .06, .24, respectively).4 Oral diclofenac produced more adverse GI side effects than the topical solution (48% vs 35%; P=.0006).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality states that topical and oral NSAIDs reduce knee OA pain equally.5

The Guidelines of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American College of Rheumatology, European League Against Rheumatism, Osteoarthritis Research Society International, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence all state that clinicians may consider topical NSAIDs for patients with mild to moderate OA of the knee or hand, particularly in patients with few affected joints or a history of sensitivity to oral NSAIDs.6

1. Towheed TE. Pennsaid therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:567-573.

2. Baraf HS, Gloth FM, Barthel HR, et al. Safety and efficacy of topical diclofenac sodium gel for knee osteoarthritis in elderly and younger patients: pooled data from three randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, multicentre trials. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:27-40.

3. Altman RD, Dreiser RL, Fisher CL, et al. Diclofenac sodium gel in patients with primary hand osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1991-1999.

4. Tugwell PS, Wells GA, Shainhouse JZ. Equivalence study of a topical diclofenac solution (Pennsaid) compared with oral diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2002-2012.

5. Chou R, McDonagh MS, Nakamoto E, et al. Analgesics for Osteoarthritis: An Update of the 2006 Comparative Effectiveness Review. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-EHC076-EF.

6. Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:476-499

Yes, at least in the short term. Topical diclofenac, with and without dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), modestly improves pain and function scores (by 4%-8%) for as long as 12 weeks in patients with osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of multiple randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Topical diclofenac modestly decreases pain scores in patients with OA of the hand in the short term (by 9% at 6 weeks) but no more than placebo at 8 weeks (SOR: B, RCT).

Both topical diclofenac with DMSO and oral diclofenac produce similar pain and function scores in patients with OA of the knee. In addition to minor skin dryness, topical diclofenac causes gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects in about a third of patients (SOR: B, RCT).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Diclofenac gel ($260-$330 per 150-mL bottle) and diclofenac with DMSO solution are the only topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) available in the United States.

Topical diclofenac with DMSO beats placebo

In a meta-analysis of 3 RCTs (697 patients, mean age 63.2, 37% male) with knee OA, topical diclofenac solution with DMSO (Pennsaid, 40 drops applied 4 times daily) demonstrated superiority to vehicle-controlled placebo at 4 to 12 weeks (mean 8.5 weeks) using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index.1 The WOMAC is a standardized patient questionnaire measuring 5 items for pain (score range 0-20), 2 for stiffness (score range 0-8), and 17 for functional limitation (score range 0-68).

Compared with placebo, topical diclofenac with DMSO resulted in 1.6 units greater reduction in pain (8% difference), 0.6 units greater reduction in stiffness (7.5% difference), and 5.5 units greater improvement in physical function (8% difference). Patients using diclofenac reported more minor skin dryness than patients using placebo (number needed to harm [NNH]=6).

Diclofenac gel is also effective, but may cause dermatitis

A pooled analysis of 3 12-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multicenter trials of 1426 patients with OA of the knee compared topical diclofenac gel (4 g applied 4 times a day) with vehicle placebo for patients older than 25 years and patients older than 65 years.2 Investigators evaluated 972 patients who suffered a symptom flare at 1, 4, 8, and 12 weeks after a one-week washout period.

Diclofenac demonstrated statistical superiority across all age groups when compared with placebo, based on pain and physical function measured on the WOMAC Index. Its effects were modest, however.

At 12 weeks, patients younger than 65 years showed pain improvement of -5.8 vs -4.7 for placebo (a 5.5% improvement on the 20-point scale) and improvement in physical function of -17.9 vs -14.2 (a 5.4% improvement on the 68-point scale). Patients older than 65 years demonstrated pain improvement of -5.3 vs -4.1 for placebo (6% improvement on the 20-point scale) and physical function improvement of -15.5 vs -11.0 for placebo (6.6% improvement on the 68-point scale).

Dermatitis was more common in the diclofenac groups, with a NNH of 30 in patients younger than 65 years and 19 in patients older than 65 years.

Diclofenac gel effectively treated hand OA for as long as 6 weeks in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 809 men and women older than 39 years. Pain scores on a 100-point visual analog scale improved when compared with placebo alone.3 At 6 weeks, topical diclofenac reduced pain scores by 45% compared with 36% for placebo (P=.023). Pain reductions also were greater in the diclofenac group at 8 weeks, although not statistically different.

Oral diclofenac works well, too, but has more GI adverse effects

An RCT of 622 patients (40-85 years of age) with symptomatic and radiographically diagnosed OA of the knee compared topical diclofenac solution (75 mg/d) with oral diclofenac (50 mg 3 times a day) and found similar efficacy at 12 weeks, with no significant difference between oral and topical preparations for pain, physical function, and stiffness measured with the WOMAC Index (P=.23, .06, .24, respectively).4 Oral diclofenac produced more adverse GI side effects than the topical solution (48% vs 35%; P=.0006).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality states that topical and oral NSAIDs reduce knee OA pain equally.5

The Guidelines of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American College of Rheumatology, European League Against Rheumatism, Osteoarthritis Research Society International, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence all state that clinicians may consider topical NSAIDs for patients with mild to moderate OA of the knee or hand, particularly in patients with few affected joints or a history of sensitivity to oral NSAIDs.6

Yes, at least in the short term. Topical diclofenac, with and without dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), modestly improves pain and function scores (by 4%-8%) for as long as 12 weeks in patients with osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of multiple randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Topical diclofenac modestly decreases pain scores in patients with OA of the hand in the short term (by 9% at 6 weeks) but no more than placebo at 8 weeks (SOR: B, RCT).

Both topical diclofenac with DMSO and oral diclofenac produce similar pain and function scores in patients with OA of the knee. In addition to minor skin dryness, topical diclofenac causes gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects in about a third of patients (SOR: B, RCT).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Diclofenac gel ($260-$330 per 150-mL bottle) and diclofenac with DMSO solution are the only topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) available in the United States.

Topical diclofenac with DMSO beats placebo

In a meta-analysis of 3 RCTs (697 patients, mean age 63.2, 37% male) with knee OA, topical diclofenac solution with DMSO (Pennsaid, 40 drops applied 4 times daily) demonstrated superiority to vehicle-controlled placebo at 4 to 12 weeks (mean 8.5 weeks) using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index.1 The WOMAC is a standardized patient questionnaire measuring 5 items for pain (score range 0-20), 2 for stiffness (score range 0-8), and 17 for functional limitation (score range 0-68).

Compared with placebo, topical diclofenac with DMSO resulted in 1.6 units greater reduction in pain (8% difference), 0.6 units greater reduction in stiffness (7.5% difference), and 5.5 units greater improvement in physical function (8% difference). Patients using diclofenac reported more minor skin dryness than patients using placebo (number needed to harm [NNH]=6).

Diclofenac gel is also effective, but may cause dermatitis

A pooled analysis of 3 12-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multicenter trials of 1426 patients with OA of the knee compared topical diclofenac gel (4 g applied 4 times a day) with vehicle placebo for patients older than 25 years and patients older than 65 years.2 Investigators evaluated 972 patients who suffered a symptom flare at 1, 4, 8, and 12 weeks after a one-week washout period.

Diclofenac demonstrated statistical superiority across all age groups when compared with placebo, based on pain and physical function measured on the WOMAC Index. Its effects were modest, however.

At 12 weeks, patients younger than 65 years showed pain improvement of -5.8 vs -4.7 for placebo (a 5.5% improvement on the 20-point scale) and improvement in physical function of -17.9 vs -14.2 (a 5.4% improvement on the 68-point scale). Patients older than 65 years demonstrated pain improvement of -5.3 vs -4.1 for placebo (6% improvement on the 20-point scale) and physical function improvement of -15.5 vs -11.0 for placebo (6.6% improvement on the 68-point scale).

Dermatitis was more common in the diclofenac groups, with a NNH of 30 in patients younger than 65 years and 19 in patients older than 65 years.

Diclofenac gel effectively treated hand OA for as long as 6 weeks in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 809 men and women older than 39 years. Pain scores on a 100-point visual analog scale improved when compared with placebo alone.3 At 6 weeks, topical diclofenac reduced pain scores by 45% compared with 36% for placebo (P=.023). Pain reductions also were greater in the diclofenac group at 8 weeks, although not statistically different.

Oral diclofenac works well, too, but has more GI adverse effects

An RCT of 622 patients (40-85 years of age) with symptomatic and radiographically diagnosed OA of the knee compared topical diclofenac solution (75 mg/d) with oral diclofenac (50 mg 3 times a day) and found similar efficacy at 12 weeks, with no significant difference between oral and topical preparations for pain, physical function, and stiffness measured with the WOMAC Index (P=.23, .06, .24, respectively).4 Oral diclofenac produced more adverse GI side effects than the topical solution (48% vs 35%; P=.0006).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality states that topical and oral NSAIDs reduce knee OA pain equally.5

The Guidelines of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American College of Rheumatology, European League Against Rheumatism, Osteoarthritis Research Society International, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence all state that clinicians may consider topical NSAIDs for patients with mild to moderate OA of the knee or hand, particularly in patients with few affected joints or a history of sensitivity to oral NSAIDs.6

1. Towheed TE. Pennsaid therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:567-573.

2. Baraf HS, Gloth FM, Barthel HR, et al. Safety and efficacy of topical diclofenac sodium gel for knee osteoarthritis in elderly and younger patients: pooled data from three randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, multicentre trials. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:27-40.

3. Altman RD, Dreiser RL, Fisher CL, et al. Diclofenac sodium gel in patients with primary hand osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1991-1999.

4. Tugwell PS, Wells GA, Shainhouse JZ. Equivalence study of a topical diclofenac solution (Pennsaid) compared with oral diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2002-2012.

5. Chou R, McDonagh MS, Nakamoto E, et al. Analgesics for Osteoarthritis: An Update of the 2006 Comparative Effectiveness Review. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-EHC076-EF.

6. Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:476-499

1. Towheed TE. Pennsaid therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:567-573.

2. Baraf HS, Gloth FM, Barthel HR, et al. Safety and efficacy of topical diclofenac sodium gel for knee osteoarthritis in elderly and younger patients: pooled data from three randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, multicentre trials. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:27-40.

3. Altman RD, Dreiser RL, Fisher CL, et al. Diclofenac sodium gel in patients with primary hand osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1991-1999.

4. Tugwell PS, Wells GA, Shainhouse JZ. Equivalence study of a topical diclofenac solution (Pennsaid) compared with oral diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2002-2012.

5. Chou R, McDonagh MS, Nakamoto E, et al. Analgesics for Osteoarthritis: An Update of the 2006 Comparative Effectiveness Review. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-EHC076-EF.

6. Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:476-499

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the best beta-blocker for systolic heart failure?

Three beta-blockers—carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol—reduce mortality equally (by about 30% over one year) in patients with Class III or IV systolic heart failure. Insufficient evidence exists comparing equipotent doses of these medications head-to-head to recommend any one over the others (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review/meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 network meta-analysis compared beta-blockers with placebo or standard treatment by analyzing 21 randomized trials with a total of 23,122 patients.1 Investigators found that beta-blockers as a class significantly reduced mortality after a median of 12 months (odds ratio=0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64-0.80; number needed to treat [NNT]=23).

They also compared atenolol, bisoprolol, bucindolol, carvedilol, metoprolol, and nebivolol with each other and found no significant difference in risk of death, sudden cardiac death, death resulting from pump failure, or tolerability.

Three drugs are more effective and tolerable than others

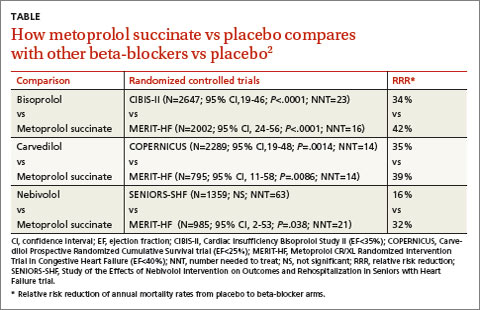

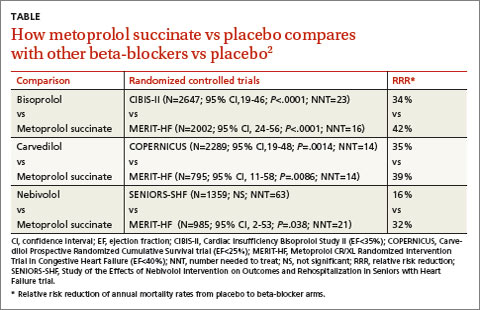

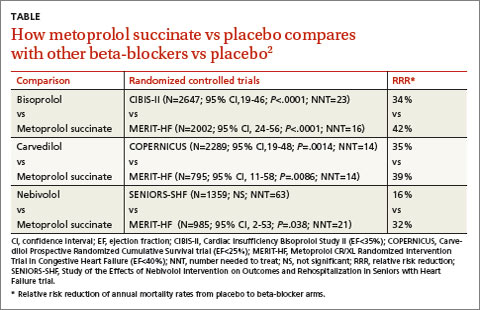

A 2013 stratified subset meta-analysis used data from landmark randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated beta-blockers vs placebo in patients with systolic heart failure to compare metoprolol succinate (MERIT-HF) vs placebo with bisoprolol (CIBIS-II), carvedilol (COPERNICUS), and nebivolol (SENIORS-SHF) vs placebo (TABLE).2

Three of the drugs—bisoprolol, carvedilol, and metoprolol succinate—showed similar reductions relative to placebo in all-cause mortality, hospitalization for heart failure, and tolerability. Investigators concluded that the 3 drugs have comparable efficacy and tolerability, whereas nebivolol is less effective and tolerable.

Carvedilol vs beta-1-selective beta-blockers

Another 2013 meta-analysis of 8 RCTs with 4563 adult patients 18 years or older with systolic heart failure compared carvedilol with the beta-1-selective beta-blockers atenolol, bisoprolol, nebivolol, and metoprolol.3 Investigators found that carvedilol significantly reduced all-cause mortality (relative risk=0.85; 95% CI, 0.78-0.93; NNT=23) compared with beta-1-selective beta-blockers.

However, 4 trials (including COMET, N=3029) compared carvedilol with short-acting metoprolol tartrate, which may have skewed results in favor of carvedilol. Moreover, 2 trials comparing carvedilol with bisoprolol and 2 trials comparing carvedilol with nebivolol found no significant difference in all-cause mortality.3

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2010 Heart Failure Society of America Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline notes that the marked beneficial effects of beta blockade with carvedilol, bisoprolol, and controlled- or extended-release metoprolol have been well-demonstrated in large-scale clinical trials of symptomatic patients with Class II to IV heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.4

The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association heart failure guideline recommends the use of one of the 3 beta-blockers proven to reduce mortality (bisoprolol, carvedilol, or sustained-release metoprolol succinate) for all patients with current or previous symptoms of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, unless contraindicated, to reduce morbidity and mortality.5

1. Chatterjee S, Biondi-Zoccai G, Abbate A, et al. Benefits of b blockers in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f55.

2. Wikstrand J, Wedel H, Castagno D, et al. The large-scale placebo-controlled beta-blocker studies in systolic heart failure revisited: results from CIBIS-II, COPERNICUS and SENIORS-SHF compared with stratified subsets from MERIT-HF. J Intern Med. 2014;275:134-143.

3. DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ, Fares H, et al. Meta-analysis of carvedilol versus beta 1 selective beta-blockers (atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, and nebivolol). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:765-769.