User login

LISTEN NOW: Gastroenterologist, Robert Coben, MD, on GI Bleeds, Colon Cancer

ROBERT COBEN, MD, Program director of the gastroenterology fellowship program at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, discusses GI bleeds and colon cancer.

ROBERT COBEN, MD, Program director of the gastroenterology fellowship program at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, discusses GI bleeds and colon cancer.

ROBERT COBEN, MD, Program director of the gastroenterology fellowship program at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, discusses GI bleeds and colon cancer.

Early relapse signals high mortality in follicular lymphoma

Patients with follicular lymphoma who relapse within 2 years of receiving R-CHOP chemoimmunotherapy are at high risk of death, unlike those who do not relapse early, according to a report published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Survival in follicular lymphoma, the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States, has dramatically improved over time, and the median survival after first-line chemoimmunotherapy now exceeds 18 years. But researchers have noted a remarkably consistent 20% rate of early relapse across numerous forms of treatment and varied study populations. Until now, the clinical significance of early relapse and its impact on overall survival has not been explored, said Dr. Carla Casulo of the University of Rochester, New York, and her associates.

They examined this issue using data from a national cohort of patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma, focusing on 588 patients with stage II, III, or IV disease who were treated using first-line rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). A total of 19% of these patients relapsed within 24 months of diagnosis. Median follow-up was 7 years. With early disease progression, overall survival was only 68% at 2 years and only 50% at 5 years, compared with 97% and 90%, respectively, among patients who didn’t have early disease progression. Early progression was associated with markedly reduced survival, with a hazard ratio of 7.17.

To verify their findings in a separate cohort, Dr. Casulo and her associates assessed survival in 147 similar patients participating in a different study who were followed for a mean of 5.5 years. A total of 26% of this cohort had early relapse after receiving a variety of first-line chemoimmunotherapy regimens. With early disease progression, overall survival was only 64% at 2 years and only 34% at 5 years, compared with 98% and 94%, respectively, among patients who didn’t have early progression. Again, early progression was associated with markedly reduced survival, with an HR of 20.0 (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 June 29 [doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7534]).

These two studies confirm that patients with follicular lymphoma who relapse within 2 years constitute a distinct subgroup at very high risk of death. “Given their poor prognosis, consideration of aggressive second-line treatments, including possibly autologous stem-cell transplantation, seem reasonable,” the investigators said.

Patients with follicular lymphoma who relapse within 2 years of receiving R-CHOP chemoimmunotherapy are at high risk of death, unlike those who do not relapse early, according to a report published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Survival in follicular lymphoma, the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States, has dramatically improved over time, and the median survival after first-line chemoimmunotherapy now exceeds 18 years. But researchers have noted a remarkably consistent 20% rate of early relapse across numerous forms of treatment and varied study populations. Until now, the clinical significance of early relapse and its impact on overall survival has not been explored, said Dr. Carla Casulo of the University of Rochester, New York, and her associates.

They examined this issue using data from a national cohort of patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma, focusing on 588 patients with stage II, III, or IV disease who were treated using first-line rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). A total of 19% of these patients relapsed within 24 months of diagnosis. Median follow-up was 7 years. With early disease progression, overall survival was only 68% at 2 years and only 50% at 5 years, compared with 97% and 90%, respectively, among patients who didn’t have early disease progression. Early progression was associated with markedly reduced survival, with a hazard ratio of 7.17.

To verify their findings in a separate cohort, Dr. Casulo and her associates assessed survival in 147 similar patients participating in a different study who were followed for a mean of 5.5 years. A total of 26% of this cohort had early relapse after receiving a variety of first-line chemoimmunotherapy regimens. With early disease progression, overall survival was only 64% at 2 years and only 34% at 5 years, compared with 98% and 94%, respectively, among patients who didn’t have early progression. Again, early progression was associated with markedly reduced survival, with an HR of 20.0 (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 June 29 [doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7534]).

These two studies confirm that patients with follicular lymphoma who relapse within 2 years constitute a distinct subgroup at very high risk of death. “Given their poor prognosis, consideration of aggressive second-line treatments, including possibly autologous stem-cell transplantation, seem reasonable,” the investigators said.

Patients with follicular lymphoma who relapse within 2 years of receiving R-CHOP chemoimmunotherapy are at high risk of death, unlike those who do not relapse early, according to a report published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Survival in follicular lymphoma, the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States, has dramatically improved over time, and the median survival after first-line chemoimmunotherapy now exceeds 18 years. But researchers have noted a remarkably consistent 20% rate of early relapse across numerous forms of treatment and varied study populations. Until now, the clinical significance of early relapse and its impact on overall survival has not been explored, said Dr. Carla Casulo of the University of Rochester, New York, and her associates.

They examined this issue using data from a national cohort of patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma, focusing on 588 patients with stage II, III, or IV disease who were treated using first-line rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). A total of 19% of these patients relapsed within 24 months of diagnosis. Median follow-up was 7 years. With early disease progression, overall survival was only 68% at 2 years and only 50% at 5 years, compared with 97% and 90%, respectively, among patients who didn’t have early disease progression. Early progression was associated with markedly reduced survival, with a hazard ratio of 7.17.

To verify their findings in a separate cohort, Dr. Casulo and her associates assessed survival in 147 similar patients participating in a different study who were followed for a mean of 5.5 years. A total of 26% of this cohort had early relapse after receiving a variety of first-line chemoimmunotherapy regimens. With early disease progression, overall survival was only 64% at 2 years and only 34% at 5 years, compared with 98% and 94%, respectively, among patients who didn’t have early progression. Again, early progression was associated with markedly reduced survival, with an HR of 20.0 (J. Clin. Oncol. 2015 June 29 [doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7534]).

These two studies confirm that patients with follicular lymphoma who relapse within 2 years constitute a distinct subgroup at very high risk of death. “Given their poor prognosis, consideration of aggressive second-line treatments, including possibly autologous stem-cell transplantation, seem reasonable,” the investigators said.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Patients with follicular lymphoma who relapse within 2 years of receiving R-CHOP are at high risk of death, unlike those who don’t relapse early.

Major finding: In a validation cohort, overall survival was only 64% at 2 years and only 34% at 5 years among patients who relapsed early, compared with 98% and 94% among patients who didn’t relapse early (HR, 20.0).

Data source: : A secondary analysis of a study involving 588 patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma, and a validation study in an independent cohort of 147 similar patients.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Genentech and F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Casulo reported having no financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Naloxone lotion improves disabling itch in CTCL

VANCOUVER, B.C. – Naloxone lotion appears to be a safe and effective treatment for the severe chronic itching that occurs in most patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Dr. Madeleine Duvic reported at the World Congress of Dermatology.

A major unmet need exists for better treatments for pruritis in CTCL. Antihistamines are generally ineffective. Chemotherapeutic agents provide little relief. Moreover, it has been estimated that up to half of all patients with CTCL die as a result of systemic infections arising secondary to pruritic skin excoriations, according to Dr. Duvic, professor of medicine and dermatology at the University of Texas and MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Naloxone is a pure opiate antagonist with no agonist effects. Naloxone lotion is an investigational agent that has received orphan drug status for treatment of pruritis in CTCL and a fast-track evaluation designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Duvic presented a double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter, crossover study involving 15 CTCL patients with severe itching. They were assigned to apply naloxone lotion 0.5% or its vehicle four times daily for 8 days and then cross over to the other regimen for another 8 days following a washout period.

After 8 days of naloxone lotion, patients reported a mean 66% reduction in itch severity from baseline on a visual analog scale, a significantly better result than the 45% reduction on vehicle.

The study suffered from small numbers, as four patients withdrew during part 1 while on vehicle, two dropped out while on naloxone lotion, and one was excluded for a concomitant medication violation. Of the nine patients available for Physician Global Assessment, seven were rated better or much better. Seven of the nine patients also rated themselves as globally better or much better while on naloxone lotion. These ratings were numerically better than while patients were on vehicle.

Adverse events were limited to two cases of mild or moderate application-site erythema.

The study was funded by Elorac. Dr. Duvic reported having no financial conflicts. She noted that the University of Texas received a research grant to conduct the study.

VANCOUVER, B.C. – Naloxone lotion appears to be a safe and effective treatment for the severe chronic itching that occurs in most patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Dr. Madeleine Duvic reported at the World Congress of Dermatology.

A major unmet need exists for better treatments for pruritis in CTCL. Antihistamines are generally ineffective. Chemotherapeutic agents provide little relief. Moreover, it has been estimated that up to half of all patients with CTCL die as a result of systemic infections arising secondary to pruritic skin excoriations, according to Dr. Duvic, professor of medicine and dermatology at the University of Texas and MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Naloxone is a pure opiate antagonist with no agonist effects. Naloxone lotion is an investigational agent that has received orphan drug status for treatment of pruritis in CTCL and a fast-track evaluation designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Duvic presented a double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter, crossover study involving 15 CTCL patients with severe itching. They were assigned to apply naloxone lotion 0.5% or its vehicle four times daily for 8 days and then cross over to the other regimen for another 8 days following a washout period.

After 8 days of naloxone lotion, patients reported a mean 66% reduction in itch severity from baseline on a visual analog scale, a significantly better result than the 45% reduction on vehicle.

The study suffered from small numbers, as four patients withdrew during part 1 while on vehicle, two dropped out while on naloxone lotion, and one was excluded for a concomitant medication violation. Of the nine patients available for Physician Global Assessment, seven were rated better or much better. Seven of the nine patients also rated themselves as globally better or much better while on naloxone lotion. These ratings were numerically better than while patients were on vehicle.

Adverse events were limited to two cases of mild or moderate application-site erythema.

The study was funded by Elorac. Dr. Duvic reported having no financial conflicts. She noted that the University of Texas received a research grant to conduct the study.

VANCOUVER, B.C. – Naloxone lotion appears to be a safe and effective treatment for the severe chronic itching that occurs in most patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Dr. Madeleine Duvic reported at the World Congress of Dermatology.

A major unmet need exists for better treatments for pruritis in CTCL. Antihistamines are generally ineffective. Chemotherapeutic agents provide little relief. Moreover, it has been estimated that up to half of all patients with CTCL die as a result of systemic infections arising secondary to pruritic skin excoriations, according to Dr. Duvic, professor of medicine and dermatology at the University of Texas and MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Naloxone is a pure opiate antagonist with no agonist effects. Naloxone lotion is an investigational agent that has received orphan drug status for treatment of pruritis in CTCL and a fast-track evaluation designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Duvic presented a double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter, crossover study involving 15 CTCL patients with severe itching. They were assigned to apply naloxone lotion 0.5% or its vehicle four times daily for 8 days and then cross over to the other regimen for another 8 days following a washout period.

After 8 days of naloxone lotion, patients reported a mean 66% reduction in itch severity from baseline on a visual analog scale, a significantly better result than the 45% reduction on vehicle.

The study suffered from small numbers, as four patients withdrew during part 1 while on vehicle, two dropped out while on naloxone lotion, and one was excluded for a concomitant medication violation. Of the nine patients available for Physician Global Assessment, seven were rated better or much better. Seven of the nine patients also rated themselves as globally better or much better while on naloxone lotion. These ratings were numerically better than while patients were on vehicle.

Adverse events were limited to two cases of mild or moderate application-site erythema.

The study was funded by Elorac. Dr. Duvic reported having no financial conflicts. She noted that the University of Texas received a research grant to conduct the study.

AT WCD 2015

Key clinical point: Naloxone lotion shows promise for the severe pruritis that accompanies cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Major finding: Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma reported an absolute 21% greater reduction in pruritis with naloxone lotion than with its vehicle.

Data source: This was a 15-patient, multicenter, double-blind, crossover study.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Elorac. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Selecting the right contraception method for cancer patients

Patient choice, contraceptive effectiveness, and medical eligibility all need to be incorporated into the contraceptive counseling for reproductive-age women who have cancer or are in remission. Based on these principles, women can minimize the risk of an unintended pregnancy, continue to receive necessary adjuvant or preventive therapy, and maintain high levels of contraception satisfaction.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published medical eligibility criteria (MEC) to assist providers in selecting medically appropriate contraception for women with various health conditions, including cancer (MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1-6).

Certain classes of hormonal contraception are contraindicated in specific cancer types. It is important to note that the copper intrauterine device (ParaGard) is very effective (with a first-year failure rate of 0.8%) and has no cancer-related contraindications. Any contraceptive with estrogen or progesterone is relatively contraindicated in hormonally mediated cancers, including breast, endometrial, or other cancers that have estrogen (ER) or progesterone (PR) positive receptors. Combined hormonal contraception is contraindicated even in breast cancers that are ER/PR negative for the first 5 years, after which they are CDC MEC category 3 (risks likely outweigh the benefits).

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is an important cancer-related morbidity. Active cancer increases the risk of VTE by fourfold, which is further increased if the patient is on chemotherapy (Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:809-15). Estrogen is known to increase thrombotic risk, and therefore it is contraindicated in any patient at risk for VTE or with a history of a VTE. There is some debate about the use of progestin-only contraceptives in those at risk of (or with a history of) VTE. The best evidence and CDC guidelines indicate that progestin-only methods can be used in patients with cancer or with a history of VTE. Importantly, no known association exists between emergency contraception and VTE (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:1100-9).

Other cancer-specific problems that may impact contraception include thrombocytopenia, gastrointestinal side effects, and drug interactions. Thrombocytopenia may exacerbate or cause abnormal uterine bleeding. Therefore, menstrual suppression with continuous combined hormonal contraception or progestin-only methods, including the hormonal IUD and implant, may be ideal. Regarding gastrointestinal side effects, emesis and mucositis from cancer and treatment may reduce absorption of oral contraceptives, so alternatives should be considered. Antacids, analgesics, antifungals, anticonvulsants, and antiretrovirals are all known to affect hepatic metabolism and may affect oral contraceptive efficacy.

Given the possibility of chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression, there is a theoretical concern about the infectious risk of an indwelling foreign body such as an IUD or implant. The best evidence to date, however, does not support an increased risk, even in the setting of neutropenia. Chemotherapy also increases osteoporosis. Gynecologists should use caution with depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), although there is no absolute contraindication, especially for shorter durations of use.

Many breast cancer patients are prescribed tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy, but the antiestrogenic effects of tamoxifen may not prevent pregnancy (Cancer Imaging 2008;8:135-45). Therefore, it is critical for reproductive-age women taking tamoxifen to be given effective contraception. Experts have not reached a consensus on the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine systems (LNG-IUS, Mirena, or Skyla) in the setting of breast cancer.

On the one hand, patients on long-term tamoxifen may benefit from the endometrial protective effect of an LNG-IUS (Lancet 2000;356:1711-7). It is uncertain if women with an LNG-IUS in place at the time of breast cancer diagnosis should have the device removed. Placing a LNG-IUS is contraindicated in all cases of active cancer, but if the patient has no evidence of disease for more than 5 years, the CDC lists the LNG-IUS as category 3. Expert consensus is that studies are needed with LNG-IUS use in women with breast cancer and that use of the LNG-IUS in this population should be made with careful consideration of the risks and benefits (Fertil. Steril. 2008;90:17-22; Contraception 2012;86:191-8).

Physicians should consider the contraceptive needs of women who are actively being or have recently been treated for cancer, as 17% of female cancers occur in women of reproductive age. The copper IUD is a highly effective option with very few contraindications. In patients with a history of non–hormonal related cancer (and without any history of VTE), all contraceptive options can be considered, including those containing estrogen. Estrogen-containing contraceptives should be avoided in those with a history of hormonally related cancers. Those not familiar with the wide array of options should consider referring early, and family planning specialists should consider medical eligibility while counseling women about the most effective contraceptive options.

Dr. Zerden is a family planning fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He reported having no financial disclosures. E-mail Dr. Zerden at [email protected].

Patient choice, contraceptive effectiveness, and medical eligibility all need to be incorporated into the contraceptive counseling for reproductive-age women who have cancer or are in remission. Based on these principles, women can minimize the risk of an unintended pregnancy, continue to receive necessary adjuvant or preventive therapy, and maintain high levels of contraception satisfaction.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published medical eligibility criteria (MEC) to assist providers in selecting medically appropriate contraception for women with various health conditions, including cancer (MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1-6).

Certain classes of hormonal contraception are contraindicated in specific cancer types. It is important to note that the copper intrauterine device (ParaGard) is very effective (with a first-year failure rate of 0.8%) and has no cancer-related contraindications. Any contraceptive with estrogen or progesterone is relatively contraindicated in hormonally mediated cancers, including breast, endometrial, or other cancers that have estrogen (ER) or progesterone (PR) positive receptors. Combined hormonal contraception is contraindicated even in breast cancers that are ER/PR negative for the first 5 years, after which they are CDC MEC category 3 (risks likely outweigh the benefits).

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is an important cancer-related morbidity. Active cancer increases the risk of VTE by fourfold, which is further increased if the patient is on chemotherapy (Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:809-15). Estrogen is known to increase thrombotic risk, and therefore it is contraindicated in any patient at risk for VTE or with a history of a VTE. There is some debate about the use of progestin-only contraceptives in those at risk of (or with a history of) VTE. The best evidence and CDC guidelines indicate that progestin-only methods can be used in patients with cancer or with a history of VTE. Importantly, no known association exists between emergency contraception and VTE (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:1100-9).

Other cancer-specific problems that may impact contraception include thrombocytopenia, gastrointestinal side effects, and drug interactions. Thrombocytopenia may exacerbate or cause abnormal uterine bleeding. Therefore, menstrual suppression with continuous combined hormonal contraception or progestin-only methods, including the hormonal IUD and implant, may be ideal. Regarding gastrointestinal side effects, emesis and mucositis from cancer and treatment may reduce absorption of oral contraceptives, so alternatives should be considered. Antacids, analgesics, antifungals, anticonvulsants, and antiretrovirals are all known to affect hepatic metabolism and may affect oral contraceptive efficacy.

Given the possibility of chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression, there is a theoretical concern about the infectious risk of an indwelling foreign body such as an IUD or implant. The best evidence to date, however, does not support an increased risk, even in the setting of neutropenia. Chemotherapy also increases osteoporosis. Gynecologists should use caution with depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), although there is no absolute contraindication, especially for shorter durations of use.

Many breast cancer patients are prescribed tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy, but the antiestrogenic effects of tamoxifen may not prevent pregnancy (Cancer Imaging 2008;8:135-45). Therefore, it is critical for reproductive-age women taking tamoxifen to be given effective contraception. Experts have not reached a consensus on the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine systems (LNG-IUS, Mirena, or Skyla) in the setting of breast cancer.

On the one hand, patients on long-term tamoxifen may benefit from the endometrial protective effect of an LNG-IUS (Lancet 2000;356:1711-7). It is uncertain if women with an LNG-IUS in place at the time of breast cancer diagnosis should have the device removed. Placing a LNG-IUS is contraindicated in all cases of active cancer, but if the patient has no evidence of disease for more than 5 years, the CDC lists the LNG-IUS as category 3. Expert consensus is that studies are needed with LNG-IUS use in women with breast cancer and that use of the LNG-IUS in this population should be made with careful consideration of the risks and benefits (Fertil. Steril. 2008;90:17-22; Contraception 2012;86:191-8).

Physicians should consider the contraceptive needs of women who are actively being or have recently been treated for cancer, as 17% of female cancers occur in women of reproductive age. The copper IUD is a highly effective option with very few contraindications. In patients with a history of non–hormonal related cancer (and without any history of VTE), all contraceptive options can be considered, including those containing estrogen. Estrogen-containing contraceptives should be avoided in those with a history of hormonally related cancers. Those not familiar with the wide array of options should consider referring early, and family planning specialists should consider medical eligibility while counseling women about the most effective contraceptive options.

Dr. Zerden is a family planning fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He reported having no financial disclosures. E-mail Dr. Zerden at [email protected].

Patient choice, contraceptive effectiveness, and medical eligibility all need to be incorporated into the contraceptive counseling for reproductive-age women who have cancer or are in remission. Based on these principles, women can minimize the risk of an unintended pregnancy, continue to receive necessary adjuvant or preventive therapy, and maintain high levels of contraception satisfaction.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published medical eligibility criteria (MEC) to assist providers in selecting medically appropriate contraception for women with various health conditions, including cancer (MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1-6).

Certain classes of hormonal contraception are contraindicated in specific cancer types. It is important to note that the copper intrauterine device (ParaGard) is very effective (with a first-year failure rate of 0.8%) and has no cancer-related contraindications. Any contraceptive with estrogen or progesterone is relatively contraindicated in hormonally mediated cancers, including breast, endometrial, or other cancers that have estrogen (ER) or progesterone (PR) positive receptors. Combined hormonal contraception is contraindicated even in breast cancers that are ER/PR negative for the first 5 years, after which they are CDC MEC category 3 (risks likely outweigh the benefits).

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is an important cancer-related morbidity. Active cancer increases the risk of VTE by fourfold, which is further increased if the patient is on chemotherapy (Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:809-15). Estrogen is known to increase thrombotic risk, and therefore it is contraindicated in any patient at risk for VTE or with a history of a VTE. There is some debate about the use of progestin-only contraceptives in those at risk of (or with a history of) VTE. The best evidence and CDC guidelines indicate that progestin-only methods can be used in patients with cancer or with a history of VTE. Importantly, no known association exists between emergency contraception and VTE (Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115:1100-9).

Other cancer-specific problems that may impact contraception include thrombocytopenia, gastrointestinal side effects, and drug interactions. Thrombocytopenia may exacerbate or cause abnormal uterine bleeding. Therefore, menstrual suppression with continuous combined hormonal contraception or progestin-only methods, including the hormonal IUD and implant, may be ideal. Regarding gastrointestinal side effects, emesis and mucositis from cancer and treatment may reduce absorption of oral contraceptives, so alternatives should be considered. Antacids, analgesics, antifungals, anticonvulsants, and antiretrovirals are all known to affect hepatic metabolism and may affect oral contraceptive efficacy.

Given the possibility of chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression, there is a theoretical concern about the infectious risk of an indwelling foreign body such as an IUD or implant. The best evidence to date, however, does not support an increased risk, even in the setting of neutropenia. Chemotherapy also increases osteoporosis. Gynecologists should use caution with depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), although there is no absolute contraindication, especially for shorter durations of use.

Many breast cancer patients are prescribed tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy, but the antiestrogenic effects of tamoxifen may not prevent pregnancy (Cancer Imaging 2008;8:135-45). Therefore, it is critical for reproductive-age women taking tamoxifen to be given effective contraception. Experts have not reached a consensus on the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine systems (LNG-IUS, Mirena, or Skyla) in the setting of breast cancer.

On the one hand, patients on long-term tamoxifen may benefit from the endometrial protective effect of an LNG-IUS (Lancet 2000;356:1711-7). It is uncertain if women with an LNG-IUS in place at the time of breast cancer diagnosis should have the device removed. Placing a LNG-IUS is contraindicated in all cases of active cancer, but if the patient has no evidence of disease for more than 5 years, the CDC lists the LNG-IUS as category 3. Expert consensus is that studies are needed with LNG-IUS use in women with breast cancer and that use of the LNG-IUS in this population should be made with careful consideration of the risks and benefits (Fertil. Steril. 2008;90:17-22; Contraception 2012;86:191-8).

Physicians should consider the contraceptive needs of women who are actively being or have recently been treated for cancer, as 17% of female cancers occur in women of reproductive age. The copper IUD is a highly effective option with very few contraindications. In patients with a history of non–hormonal related cancer (and without any history of VTE), all contraceptive options can be considered, including those containing estrogen. Estrogen-containing contraceptives should be avoided in those with a history of hormonally related cancers. Those not familiar with the wide array of options should consider referring early, and family planning specialists should consider medical eligibility while counseling women about the most effective contraceptive options.

Dr. Zerden is a family planning fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He reported having no financial disclosures. E-mail Dr. Zerden at [email protected].

Few U.S. Stroke Patients Get Clot-Busting Treatment

(Reuters Health) - Not all U.S. stroke patients eligible for thrombolytic therapy actually receive it - and the odds of getting this therapy may depend on where they live, a large study finds.

Dr. James Burke of the University of Michigan and the VA Ann Arbor Health System and colleagues examined 844,241 hospital admissions for ischemic stroke from 2007 to 2010 among U.S. patients insured by Medicare.

They sorted patients into 3,436 different hospital service areas based on home postal code to assess regional variation in thrombolysis treatment rates.

Patients were 78 years old on average. About 57% were women, and most were white. The majority had hypertension and many also had diabetes, high cholesterol or arrhythmia.

Overall, just 3.9% of these patients received thrombolysis, the researchers report online June 2 in the journal Stroke. The treatment wasn't given at all in 20% of regions, and it was more likely to occur in places with higher population density.

In the 20 regions with the highest rates of thrombolysis, roughly 10% to 14% of patients received the treatment.

After accounting for the number of strokes in each region, the proportion of patients receiving thrombolysis ranged from 2.2% in the bottom fifth of regions to 5.9% in the top fifth.

Older patients, women and minorities were less likely to receive the treatment. Regions with the lowest proportion of college graduates also had a smaller percentage of people treated with thrombolysis.

Not every patient with stroke should receive thrombolysis. One study in Cincinnati estimated that about 6% of stroke patients would be eligible, but the new findings of higher rates in the highest-performing regions suggest that more patients could benefit if they could be transported more quickly to hospitals where thrombolysis is available, the authors say.

By boosting use of the treatment in regions where it's least likely to happen up to the level in places where the therapy is most common, researchers estimated that an additional 92,847 stroke patients might get thrombolysis, averting disability for 8,078 of them.

"Prompt recognition and reaction to warning signs and effective emergency service systems can minimize delays in pre-hospital dispatch, assessment and transport, and ultimately increase the number of stroke patients reaching the hospital and being prepared for thrombolytic therapy within the 4.5-hour time window," Dr. Maurizio Paciaroni, a stroke specialist at the University of Perugia in Italy who wasn't involved in the study, said by email.

"For a variety of reasons, only a minority of patients get to the hospital within the first couple hours of a stroke," Burke said by email. Patients might not recognize symptoms or call 911 soon enough, and even when they do seek help quickly they might not end up at a hospital that's equipped to provide thrombolysis, he added.

The best outcomes are for patients who receive thrombolysis within the first hour after the blood vessel becomes blocked, said Dr. Brian Silver, director of the Comprehensive Stroke Center at Rhode Island Hospital and researcher at Brown University.

"When patients don't receive this treatment, they are up to 50% less likely to have a better outcome," Silver, who wasn't involved with the study, said by email. "This means, for some, residual speech difficulties, paralysis, vision loss, cognitive impairment and depression."

Globally, 15 million people suffer strokes each year; five million of them die and another five million are left permanently disabled, according to the World Health Organization.

(Reuters Health) - Not all U.S. stroke patients eligible for thrombolytic therapy actually receive it - and the odds of getting this therapy may depend on where they live, a large study finds.

Dr. James Burke of the University of Michigan and the VA Ann Arbor Health System and colleagues examined 844,241 hospital admissions for ischemic stroke from 2007 to 2010 among U.S. patients insured by Medicare.

They sorted patients into 3,436 different hospital service areas based on home postal code to assess regional variation in thrombolysis treatment rates.

Patients were 78 years old on average. About 57% were women, and most were white. The majority had hypertension and many also had diabetes, high cholesterol or arrhythmia.

Overall, just 3.9% of these patients received thrombolysis, the researchers report online June 2 in the journal Stroke. The treatment wasn't given at all in 20% of regions, and it was more likely to occur in places with higher population density.

In the 20 regions with the highest rates of thrombolysis, roughly 10% to 14% of patients received the treatment.

After accounting for the number of strokes in each region, the proportion of patients receiving thrombolysis ranged from 2.2% in the bottom fifth of regions to 5.9% in the top fifth.

Older patients, women and minorities were less likely to receive the treatment. Regions with the lowest proportion of college graduates also had a smaller percentage of people treated with thrombolysis.

Not every patient with stroke should receive thrombolysis. One study in Cincinnati estimated that about 6% of stroke patients would be eligible, but the new findings of higher rates in the highest-performing regions suggest that more patients could benefit if they could be transported more quickly to hospitals where thrombolysis is available, the authors say.

By boosting use of the treatment in regions where it's least likely to happen up to the level in places where the therapy is most common, researchers estimated that an additional 92,847 stroke patients might get thrombolysis, averting disability for 8,078 of them.

"Prompt recognition and reaction to warning signs and effective emergency service systems can minimize delays in pre-hospital dispatch, assessment and transport, and ultimately increase the number of stroke patients reaching the hospital and being prepared for thrombolytic therapy within the 4.5-hour time window," Dr. Maurizio Paciaroni, a stroke specialist at the University of Perugia in Italy who wasn't involved in the study, said by email.

"For a variety of reasons, only a minority of patients get to the hospital within the first couple hours of a stroke," Burke said by email. Patients might not recognize symptoms or call 911 soon enough, and even when they do seek help quickly they might not end up at a hospital that's equipped to provide thrombolysis, he added.

The best outcomes are for patients who receive thrombolysis within the first hour after the blood vessel becomes blocked, said Dr. Brian Silver, director of the Comprehensive Stroke Center at Rhode Island Hospital and researcher at Brown University.

"When patients don't receive this treatment, they are up to 50% less likely to have a better outcome," Silver, who wasn't involved with the study, said by email. "This means, for some, residual speech difficulties, paralysis, vision loss, cognitive impairment and depression."

Globally, 15 million people suffer strokes each year; five million of them die and another five million are left permanently disabled, according to the World Health Organization.

(Reuters Health) - Not all U.S. stroke patients eligible for thrombolytic therapy actually receive it - and the odds of getting this therapy may depend on where they live, a large study finds.

Dr. James Burke of the University of Michigan and the VA Ann Arbor Health System and colleagues examined 844,241 hospital admissions for ischemic stroke from 2007 to 2010 among U.S. patients insured by Medicare.

They sorted patients into 3,436 different hospital service areas based on home postal code to assess regional variation in thrombolysis treatment rates.

Patients were 78 years old on average. About 57% were women, and most were white. The majority had hypertension and many also had diabetes, high cholesterol or arrhythmia.

Overall, just 3.9% of these patients received thrombolysis, the researchers report online June 2 in the journal Stroke. The treatment wasn't given at all in 20% of regions, and it was more likely to occur in places with higher population density.

In the 20 regions with the highest rates of thrombolysis, roughly 10% to 14% of patients received the treatment.

After accounting for the number of strokes in each region, the proportion of patients receiving thrombolysis ranged from 2.2% in the bottom fifth of regions to 5.9% in the top fifth.

Older patients, women and minorities were less likely to receive the treatment. Regions with the lowest proportion of college graduates also had a smaller percentage of people treated with thrombolysis.

Not every patient with stroke should receive thrombolysis. One study in Cincinnati estimated that about 6% of stroke patients would be eligible, but the new findings of higher rates in the highest-performing regions suggest that more patients could benefit if they could be transported more quickly to hospitals where thrombolysis is available, the authors say.

By boosting use of the treatment in regions where it's least likely to happen up to the level in places where the therapy is most common, researchers estimated that an additional 92,847 stroke patients might get thrombolysis, averting disability for 8,078 of them.

"Prompt recognition and reaction to warning signs and effective emergency service systems can minimize delays in pre-hospital dispatch, assessment and transport, and ultimately increase the number of stroke patients reaching the hospital and being prepared for thrombolytic therapy within the 4.5-hour time window," Dr. Maurizio Paciaroni, a stroke specialist at the University of Perugia in Italy who wasn't involved in the study, said by email.

"For a variety of reasons, only a minority of patients get to the hospital within the first couple hours of a stroke," Burke said by email. Patients might not recognize symptoms or call 911 soon enough, and even when they do seek help quickly they might not end up at a hospital that's equipped to provide thrombolysis, he added.

The best outcomes are for patients who receive thrombolysis within the first hour after the blood vessel becomes blocked, said Dr. Brian Silver, director of the Comprehensive Stroke Center at Rhode Island Hospital and researcher at Brown University.

"When patients don't receive this treatment, they are up to 50% less likely to have a better outcome," Silver, who wasn't involved with the study, said by email. "This means, for some, residual speech difficulties, paralysis, vision loss, cognitive impairment and depression."

Globally, 15 million people suffer strokes each year; five million of them die and another five million are left permanently disabled, according to the World Health Organization.

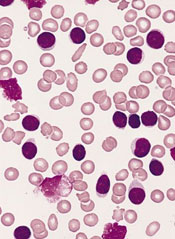

HSCT outcomes ‘encouraging’ in JAKi responders

Photo by Chad McNeeley

VIENNA—Outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) are encouraging in myelofibrosis (MF) patients who respond well to JAK inhibitors, according to researchers.

The group found that patients with the best response to JAK inhibition had a 2-year survival probability of 91% after HSCT, compared to 32% for patients with

leukemic transformation while on a JAK inhibitor.

In addition, receiving a JAK inhibitor until HSCT could prevent the return of MF-related symptoms.

Mohamed Shanavas, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, presented these findings at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S450*).

The decision to undergo HSCT is a complex one in MF, particularly for those patients who are responding to JAK inhibitors. So Dr Shanavas and his colleagues undertook a retrospective, multicenter analysis to determine if there is an association between response to JAK inhibition and HSCT outcome.

The investigators analyzed the outcomes of 100 patients who had a first HSCT for primary MF, post-essential thrombocythemia MF, or post-polycythemia vera MF. Patients had to have exposure to a JAK inhibitor but no history of leukemic transformation prior to taking a JAK inhibitor.

Response criteria

The researchers stratified patients’ JAK1/2 response according to the following criteria:

- Group A: Clinical improvement: Fifty percent or greater reduction in palpable spleen length for spleen palpable by ≥ 10 cm, or complete resolution of splenomegaly for spleen < 10 cm

- Group B: Stable disease: Spleen response not meeting the criteria of clinical improvement

- Group C: A 10% to 19% increase in blasts, new onset of anemia requiring transfusions, or intolerance to treatment due to side effects

- Group D: Progressive disease: New splenomegaly > 5 cm, 100% increase in spleen 5-10 cm, or 50% increase in spleen > 10 cm

- Group E: Leukemic transformation: Bone marrow or circulating blasts ≥ 20%.

Patient and treatment characteristics

Patients were a median age of 59 (range, 32–72). Fifty-seven had primary MF, 21 had post-essential thrombocythemia MF, and 22 had post-polycythemia vera MF. Sixty-two patients had JAK2V617F-mutated disease, 37 were wild-type, and 1 had unknown JAK status.

The majority of patients had intermediate-2 or high-risk disease according to their DIPSS scores, and 42 had a transplant comorbidity index score of 3 or greater.

Most patients (n=91) had ruxolitinib as their JAK inhibitor, 6 had momelotinib, and 3 had another inhibitor.

The median duration of JAK inhibitor therapy was 5 months (range, 1–36), and 66 patients were on treatment at the time of transplant. Thirty patients had previously discontinued JAK therapy, and the status of 4 was unknown.

In terms of their response to JAK inhibitors, 23 patients were in group A (clinical improvement), 31 in group B (stable disease), 15 in group C (increased blasts/transfusion need/intolerance), 18 in group D (progressive disease), and 13 in group E (leukemic transformation).

Fifty patients received a matched unrelated donor transplant, 36 had a matched sibling donor, and 14 had either a mismatched unrelated donor or a haploidentical transplant.

Fifty-six patients had a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen, and 44 had full intensity. Fifty percent of patients had T-cell depletion prior to transplant.

Outcomes

Patients who stopped JAK inhibitor therapy 6 or more days prior to transplant (n=20) experienced more “withdrawal symptoms”—the return of MF-related symptoms—than patients in whom the interval was less than 6 days (n=46). For the most part, withdrawal symptoms were non-severe in nature.

Two patients had fatal HSCT-related toxicity of venoocclusive disease, 4 had primary graft failure, and 4 had secondary graft failure. Forty-three percent of cytomegalovirus-seropositive patients had reactivation, 6 patients had Epstein-Barr virus reactivation, 6 had adenovirus or human polyomavirus BK infections, and 7 had invasive fungal infections.

Grade 2-4 acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) occurred in 37% of patients at day 100, and grade 3-4 occurred in 16%. Chronic GVHD of all grades occurred in 48% of patients, and extensive chronic GVHD occurred in 23%.

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years was 17%, and non-relapse mortality was 28%. Overall survival (OS) was 61%.

“We analyzed this outcome based upon the response to JAK inhibitors,” Dr Shanavas said. “Patients who were deriving clinical improvement, group A, had a superior outcome, with a probability of survival of 91% at 2 years. Patients who had leukemic transformation, group E, had an inferior OS of 32% at 2 years.”

He noted that the outcomes appeared similar in the other 3 groups, so the researchers combined them for further analysis.

“As expected,” he said, “patients who had leukemic transformation had a significantly higher relapse rate than the other groups.”

The researchers then performed a multivariate analysis and found that response to JAK inhibitors, DIPSS score prior to JAK therapy, and donor type had a significant effect on OS.

The team concluded that prior exposure to JAK inhibitors does not have a negative effect on early HSCT outcomes. And actually, patients who undergo HSCT while responding to JAK inhibitors have encouraging outcomes. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

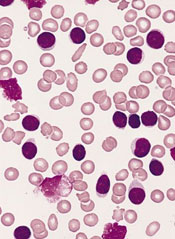

Photo by Chad McNeeley

VIENNA—Outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) are encouraging in myelofibrosis (MF) patients who respond well to JAK inhibitors, according to researchers.

The group found that patients with the best response to JAK inhibition had a 2-year survival probability of 91% after HSCT, compared to 32% for patients with

leukemic transformation while on a JAK inhibitor.

In addition, receiving a JAK inhibitor until HSCT could prevent the return of MF-related symptoms.

Mohamed Shanavas, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, presented these findings at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S450*).

The decision to undergo HSCT is a complex one in MF, particularly for those patients who are responding to JAK inhibitors. So Dr Shanavas and his colleagues undertook a retrospective, multicenter analysis to determine if there is an association between response to JAK inhibition and HSCT outcome.

The investigators analyzed the outcomes of 100 patients who had a first HSCT for primary MF, post-essential thrombocythemia MF, or post-polycythemia vera MF. Patients had to have exposure to a JAK inhibitor but no history of leukemic transformation prior to taking a JAK inhibitor.

Response criteria

The researchers stratified patients’ JAK1/2 response according to the following criteria:

- Group A: Clinical improvement: Fifty percent or greater reduction in palpable spleen length for spleen palpable by ≥ 10 cm, or complete resolution of splenomegaly for spleen < 10 cm

- Group B: Stable disease: Spleen response not meeting the criteria of clinical improvement

- Group C: A 10% to 19% increase in blasts, new onset of anemia requiring transfusions, or intolerance to treatment due to side effects

- Group D: Progressive disease: New splenomegaly > 5 cm, 100% increase in spleen 5-10 cm, or 50% increase in spleen > 10 cm

- Group E: Leukemic transformation: Bone marrow or circulating blasts ≥ 20%.

Patient and treatment characteristics

Patients were a median age of 59 (range, 32–72). Fifty-seven had primary MF, 21 had post-essential thrombocythemia MF, and 22 had post-polycythemia vera MF. Sixty-two patients had JAK2V617F-mutated disease, 37 were wild-type, and 1 had unknown JAK status.

The majority of patients had intermediate-2 or high-risk disease according to their DIPSS scores, and 42 had a transplant comorbidity index score of 3 or greater.

Most patients (n=91) had ruxolitinib as their JAK inhibitor, 6 had momelotinib, and 3 had another inhibitor.

The median duration of JAK inhibitor therapy was 5 months (range, 1–36), and 66 patients were on treatment at the time of transplant. Thirty patients had previously discontinued JAK therapy, and the status of 4 was unknown.

In terms of their response to JAK inhibitors, 23 patients were in group A (clinical improvement), 31 in group B (stable disease), 15 in group C (increased blasts/transfusion need/intolerance), 18 in group D (progressive disease), and 13 in group E (leukemic transformation).

Fifty patients received a matched unrelated donor transplant, 36 had a matched sibling donor, and 14 had either a mismatched unrelated donor or a haploidentical transplant.

Fifty-six patients had a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen, and 44 had full intensity. Fifty percent of patients had T-cell depletion prior to transplant.

Outcomes

Patients who stopped JAK inhibitor therapy 6 or more days prior to transplant (n=20) experienced more “withdrawal symptoms”—the return of MF-related symptoms—than patients in whom the interval was less than 6 days (n=46). For the most part, withdrawal symptoms were non-severe in nature.

Two patients had fatal HSCT-related toxicity of venoocclusive disease, 4 had primary graft failure, and 4 had secondary graft failure. Forty-three percent of cytomegalovirus-seropositive patients had reactivation, 6 patients had Epstein-Barr virus reactivation, 6 had adenovirus or human polyomavirus BK infections, and 7 had invasive fungal infections.

Grade 2-4 acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) occurred in 37% of patients at day 100, and grade 3-4 occurred in 16%. Chronic GVHD of all grades occurred in 48% of patients, and extensive chronic GVHD occurred in 23%.

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years was 17%, and non-relapse mortality was 28%. Overall survival (OS) was 61%.

“We analyzed this outcome based upon the response to JAK inhibitors,” Dr Shanavas said. “Patients who were deriving clinical improvement, group A, had a superior outcome, with a probability of survival of 91% at 2 years. Patients who had leukemic transformation, group E, had an inferior OS of 32% at 2 years.”

He noted that the outcomes appeared similar in the other 3 groups, so the researchers combined them for further analysis.

“As expected,” he said, “patients who had leukemic transformation had a significantly higher relapse rate than the other groups.”

The researchers then performed a multivariate analysis and found that response to JAK inhibitors, DIPSS score prior to JAK therapy, and donor type had a significant effect on OS.

The team concluded that prior exposure to JAK inhibitors does not have a negative effect on early HSCT outcomes. And actually, patients who undergo HSCT while responding to JAK inhibitors have encouraging outcomes. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

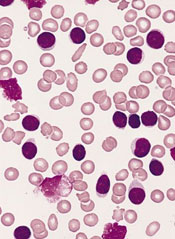

Photo by Chad McNeeley

VIENNA—Outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) are encouraging in myelofibrosis (MF) patients who respond well to JAK inhibitors, according to researchers.

The group found that patients with the best response to JAK inhibition had a 2-year survival probability of 91% after HSCT, compared to 32% for patients with

leukemic transformation while on a JAK inhibitor.

In addition, receiving a JAK inhibitor until HSCT could prevent the return of MF-related symptoms.

Mohamed Shanavas, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, presented these findings at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S450*).

The decision to undergo HSCT is a complex one in MF, particularly for those patients who are responding to JAK inhibitors. So Dr Shanavas and his colleagues undertook a retrospective, multicenter analysis to determine if there is an association between response to JAK inhibition and HSCT outcome.

The investigators analyzed the outcomes of 100 patients who had a first HSCT for primary MF, post-essential thrombocythemia MF, or post-polycythemia vera MF. Patients had to have exposure to a JAK inhibitor but no history of leukemic transformation prior to taking a JAK inhibitor.

Response criteria

The researchers stratified patients’ JAK1/2 response according to the following criteria:

- Group A: Clinical improvement: Fifty percent or greater reduction in palpable spleen length for spleen palpable by ≥ 10 cm, or complete resolution of splenomegaly for spleen < 10 cm

- Group B: Stable disease: Spleen response not meeting the criteria of clinical improvement

- Group C: A 10% to 19% increase in blasts, new onset of anemia requiring transfusions, or intolerance to treatment due to side effects

- Group D: Progressive disease: New splenomegaly > 5 cm, 100% increase in spleen 5-10 cm, or 50% increase in spleen > 10 cm

- Group E: Leukemic transformation: Bone marrow or circulating blasts ≥ 20%.

Patient and treatment characteristics

Patients were a median age of 59 (range, 32–72). Fifty-seven had primary MF, 21 had post-essential thrombocythemia MF, and 22 had post-polycythemia vera MF. Sixty-two patients had JAK2V617F-mutated disease, 37 were wild-type, and 1 had unknown JAK status.

The majority of patients had intermediate-2 or high-risk disease according to their DIPSS scores, and 42 had a transplant comorbidity index score of 3 or greater.

Most patients (n=91) had ruxolitinib as their JAK inhibitor, 6 had momelotinib, and 3 had another inhibitor.

The median duration of JAK inhibitor therapy was 5 months (range, 1–36), and 66 patients were on treatment at the time of transplant. Thirty patients had previously discontinued JAK therapy, and the status of 4 was unknown.

In terms of their response to JAK inhibitors, 23 patients were in group A (clinical improvement), 31 in group B (stable disease), 15 in group C (increased blasts/transfusion need/intolerance), 18 in group D (progressive disease), and 13 in group E (leukemic transformation).

Fifty patients received a matched unrelated donor transplant, 36 had a matched sibling donor, and 14 had either a mismatched unrelated donor or a haploidentical transplant.

Fifty-six patients had a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen, and 44 had full intensity. Fifty percent of patients had T-cell depletion prior to transplant.

Outcomes

Patients who stopped JAK inhibitor therapy 6 or more days prior to transplant (n=20) experienced more “withdrawal symptoms”—the return of MF-related symptoms—than patients in whom the interval was less than 6 days (n=46). For the most part, withdrawal symptoms were non-severe in nature.

Two patients had fatal HSCT-related toxicity of venoocclusive disease, 4 had primary graft failure, and 4 had secondary graft failure. Forty-three percent of cytomegalovirus-seropositive patients had reactivation, 6 patients had Epstein-Barr virus reactivation, 6 had adenovirus or human polyomavirus BK infections, and 7 had invasive fungal infections.

Grade 2-4 acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) occurred in 37% of patients at day 100, and grade 3-4 occurred in 16%. Chronic GVHD of all grades occurred in 48% of patients, and extensive chronic GVHD occurred in 23%.

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years was 17%, and non-relapse mortality was 28%. Overall survival (OS) was 61%.

“We analyzed this outcome based upon the response to JAK inhibitors,” Dr Shanavas said. “Patients who were deriving clinical improvement, group A, had a superior outcome, with a probability of survival of 91% at 2 years. Patients who had leukemic transformation, group E, had an inferior OS of 32% at 2 years.”

He noted that the outcomes appeared similar in the other 3 groups, so the researchers combined them for further analysis.

“As expected,” he said, “patients who had leukemic transformation had a significantly higher relapse rate than the other groups.”

The researchers then performed a multivariate analysis and found that response to JAK inhibitors, DIPSS score prior to JAK therapy, and donor type had a significant effect on OS.

The team concluded that prior exposure to JAK inhibitors does not have a negative effect on early HSCT outcomes. And actually, patients who undergo HSCT while responding to JAK inhibitors have encouraging outcomes. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Pain problems prevalent in adults with hemophilia

TORONTO—A survey of adult hemophilia patients suggests there is room for improvement in assessing and managing disease-related pain.

Roughly 85% of patients surveyed for this study, known as P-FiQ, said they had experienced acute and/or chronic pain in the past 6 months.

Although most patients had no trouble caring for themselves, the pain often had an impact on their daily lives, especially with regard to physical activity and overall mobility.

“Pain and discomfort are significant challenges for people with hemophilia,” said study investigator Michael Recht, MD, PhD, of Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland.

“These results emphasize the importance of providing comprehensive care and support beyond traditional therapy to people living with bleeding disorders.”

Dr Recht and his colleagues presented results of the P-FiQ study in 3 posters at the ISTH 2015 Congress (abstracts PO277-MON, PO297-WED, and PO298-WED).

The study included adult males with mild to severe hemophilia who had a history of joint pain or bleeding. Subjects were asked to assess pain and functional impairment using patient-reported outcome instruments.

During routine visits over the course of a year, 164 participants completed a pain history and 5 questionnaires: the EQ-5D-5L; Brief Pain Inventory Short Form, version 2; International Physical Activity Questionnaire; SF-36v2; and Hemophilia Activities List.

The patients had a median age of 34. More patients had hemophilia A (n=122) than hemophilia B (n=42), and few (n=10) had inhibitors. Sixty-one percent of patients had self-reported arthritis, bone, or joint problems.

Current patient-reported treatment regimens (n=163) were prophylaxis (42%), on-demand treatment (39%), or mostly on-demand treatment (19%). Twenty-five of the 31 patients using on-demand treatment reported using infusions ahead of activity.

Pain prevalence and management

Most participants (85.2%) said they had experienced acute and/or chronic pain over the past 6 months. Twenty-nine percent said they had experienced acute and chronic pain, 32.7% had chronic pain only, 23.5% had acute pain only, and 14.8% reported no pain.

Acute pain was most frequently described as sharp, aching, shooting, and throbbing. Chronic pain was often described as aching, nagging, throbbing, and sharp.

The most common analgesics used for acute or chronic pain were acetaminophen (69.4% and 58%, respectively), NSAIDs (40% and 52%, respectively), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (29.4% and 33%, respectively).

The most common nonanalgesic strategies used for acute or chronic pain were ice (72.9% and 37%, respectively), rest (48.2% and 34%, respectively), factor VIII/IX or bypassing agent (48.2% and 24%, respectively), elevation (34.1% and 28%, respectively), relaxation (30.6% and 23.0%, respectively), compression (27.1% and 21%, respectively), and heat (24.7% and 15%, respectively).

Impact of pain on daily life

When completing the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, most patients reported problems with mobility, performing usual activities, and pain or discomfort. However, most patients said they had no problems with self-care (78%) or anxiety/depression (58.5%).

A similar proportion of patients reported slight and moderate pain and discomfort (29.9% and 31.1%, respectively). Pain and discomfort was severe for 11% of patients and extreme for 1.2%, but 26.8% of patients reported no pain or discomfort.

When it came to mobility, patients reported slight (32.3%), moderate (19.5%), and severe (8.5%) problems, and 1.2% of patients said they were unable to get around. However, 38.4% of patients reported having no such problems.

About 44% of patients reported no problems performing usual activities, but 37.2% had slight problems, 14.6% had moderate problems, and 1.8% of patients each had severe problems or were unable to perform usual activities.

For the Brief Pain Inventory, pain severity and interference with daily activities were rated on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain/no interference and 10 being pain as bad as you can imagine/pain that completely interferes with daily life.

The overall median pain severity and pain interference were 3.0 (range, 1.3-4.8) and 2.9 (range, 0.7-5.2), respectively. The median worst pain was 6.0, least pain 2.0, average pain 3.0, and current pain 2.0. Ankles were the most frequently reported site of pain.

When completing the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, 49.3% of patients (73/148) reported no activity in the prior week.

The median SF-36v2 scores were lower for physical health domains than mental health domains, and the overall median health score was 3.0 (range, 2.0-3.0).

The median score on the Hemophilia Activities List was 76.1 (range, 59.2-95.1). And patients said hemophilia had a greater impact on their lower extremities than upper extremities.

Dr Recht and his colleagues said these results substantiate the high prevalence of pain in adults with hemophilia. And the study highlights opportunities to improve the assessment and management of pain in these patients.

Study investigators have received funding/consulting fees from—or are employees/shareholders of—Novo Nordisk, Baxter, Biogen, Bayer, OctaPharma, Pfizer, CSL Behring, Kendrion, Alexion, Grifols, OPKO Health, Sanofi, Merck, and ProMeticLife Sciences. ![]()

TORONTO—A survey of adult hemophilia patients suggests there is room for improvement in assessing and managing disease-related pain.

Roughly 85% of patients surveyed for this study, known as P-FiQ, said they had experienced acute and/or chronic pain in the past 6 months.

Although most patients had no trouble caring for themselves, the pain often had an impact on their daily lives, especially with regard to physical activity and overall mobility.

“Pain and discomfort are significant challenges for people with hemophilia,” said study investigator Michael Recht, MD, PhD, of Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland.

“These results emphasize the importance of providing comprehensive care and support beyond traditional therapy to people living with bleeding disorders.”

Dr Recht and his colleagues presented results of the P-FiQ study in 3 posters at the ISTH 2015 Congress (abstracts PO277-MON, PO297-WED, and PO298-WED).

The study included adult males with mild to severe hemophilia who had a history of joint pain or bleeding. Subjects were asked to assess pain and functional impairment using patient-reported outcome instruments.

During routine visits over the course of a year, 164 participants completed a pain history and 5 questionnaires: the EQ-5D-5L; Brief Pain Inventory Short Form, version 2; International Physical Activity Questionnaire; SF-36v2; and Hemophilia Activities List.

The patients had a median age of 34. More patients had hemophilia A (n=122) than hemophilia B (n=42), and few (n=10) had inhibitors. Sixty-one percent of patients had self-reported arthritis, bone, or joint problems.

Current patient-reported treatment regimens (n=163) were prophylaxis (42%), on-demand treatment (39%), or mostly on-demand treatment (19%). Twenty-five of the 31 patients using on-demand treatment reported using infusions ahead of activity.

Pain prevalence and management

Most participants (85.2%) said they had experienced acute and/or chronic pain over the past 6 months. Twenty-nine percent said they had experienced acute and chronic pain, 32.7% had chronic pain only, 23.5% had acute pain only, and 14.8% reported no pain.

Acute pain was most frequently described as sharp, aching, shooting, and throbbing. Chronic pain was often described as aching, nagging, throbbing, and sharp.

The most common analgesics used for acute or chronic pain were acetaminophen (69.4% and 58%, respectively), NSAIDs (40% and 52%, respectively), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (29.4% and 33%, respectively).

The most common nonanalgesic strategies used for acute or chronic pain were ice (72.9% and 37%, respectively), rest (48.2% and 34%, respectively), factor VIII/IX or bypassing agent (48.2% and 24%, respectively), elevation (34.1% and 28%, respectively), relaxation (30.6% and 23.0%, respectively), compression (27.1% and 21%, respectively), and heat (24.7% and 15%, respectively).

Impact of pain on daily life

When completing the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, most patients reported problems with mobility, performing usual activities, and pain or discomfort. However, most patients said they had no problems with self-care (78%) or anxiety/depression (58.5%).

A similar proportion of patients reported slight and moderate pain and discomfort (29.9% and 31.1%, respectively). Pain and discomfort was severe for 11% of patients and extreme for 1.2%, but 26.8% of patients reported no pain or discomfort.

When it came to mobility, patients reported slight (32.3%), moderate (19.5%), and severe (8.5%) problems, and 1.2% of patients said they were unable to get around. However, 38.4% of patients reported having no such problems.

About 44% of patients reported no problems performing usual activities, but 37.2% had slight problems, 14.6% had moderate problems, and 1.8% of patients each had severe problems or were unable to perform usual activities.

For the Brief Pain Inventory, pain severity and interference with daily activities were rated on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain/no interference and 10 being pain as bad as you can imagine/pain that completely interferes with daily life.

The overall median pain severity and pain interference were 3.0 (range, 1.3-4.8) and 2.9 (range, 0.7-5.2), respectively. The median worst pain was 6.0, least pain 2.0, average pain 3.0, and current pain 2.0. Ankles were the most frequently reported site of pain.

When completing the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, 49.3% of patients (73/148) reported no activity in the prior week.

The median SF-36v2 scores were lower for physical health domains than mental health domains, and the overall median health score was 3.0 (range, 2.0-3.0).

The median score on the Hemophilia Activities List was 76.1 (range, 59.2-95.1). And patients said hemophilia had a greater impact on their lower extremities than upper extremities.

Dr Recht and his colleagues said these results substantiate the high prevalence of pain in adults with hemophilia. And the study highlights opportunities to improve the assessment and management of pain in these patients.

Study investigators have received funding/consulting fees from—or are employees/shareholders of—Novo Nordisk, Baxter, Biogen, Bayer, OctaPharma, Pfizer, CSL Behring, Kendrion, Alexion, Grifols, OPKO Health, Sanofi, Merck, and ProMeticLife Sciences. ![]()

TORONTO—A survey of adult hemophilia patients suggests there is room for improvement in assessing and managing disease-related pain.

Roughly 85% of patients surveyed for this study, known as P-FiQ, said they had experienced acute and/or chronic pain in the past 6 months.

Although most patients had no trouble caring for themselves, the pain often had an impact on their daily lives, especially with regard to physical activity and overall mobility.

“Pain and discomfort are significant challenges for people with hemophilia,” said study investigator Michael Recht, MD, PhD, of Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland.

“These results emphasize the importance of providing comprehensive care and support beyond traditional therapy to people living with bleeding disorders.”

Dr Recht and his colleagues presented results of the P-FiQ study in 3 posters at the ISTH 2015 Congress (abstracts PO277-MON, PO297-WED, and PO298-WED).

The study included adult males with mild to severe hemophilia who had a history of joint pain or bleeding. Subjects were asked to assess pain and functional impairment using patient-reported outcome instruments.

During routine visits over the course of a year, 164 participants completed a pain history and 5 questionnaires: the EQ-5D-5L; Brief Pain Inventory Short Form, version 2; International Physical Activity Questionnaire; SF-36v2; and Hemophilia Activities List.

The patients had a median age of 34. More patients had hemophilia A (n=122) than hemophilia B (n=42), and few (n=10) had inhibitors. Sixty-one percent of patients had self-reported arthritis, bone, or joint problems.

Current patient-reported treatment regimens (n=163) were prophylaxis (42%), on-demand treatment (39%), or mostly on-demand treatment (19%). Twenty-five of the 31 patients using on-demand treatment reported using infusions ahead of activity.

Pain prevalence and management

Most participants (85.2%) said they had experienced acute and/or chronic pain over the past 6 months. Twenty-nine percent said they had experienced acute and chronic pain, 32.7% had chronic pain only, 23.5% had acute pain only, and 14.8% reported no pain.

Acute pain was most frequently described as sharp, aching, shooting, and throbbing. Chronic pain was often described as aching, nagging, throbbing, and sharp.

The most common analgesics used for acute or chronic pain were acetaminophen (69.4% and 58%, respectively), NSAIDs (40% and 52%, respectively), and hydrocodone-acetaminophen (29.4% and 33%, respectively).

The most common nonanalgesic strategies used for acute or chronic pain were ice (72.9% and 37%, respectively), rest (48.2% and 34%, respectively), factor VIII/IX or bypassing agent (48.2% and 24%, respectively), elevation (34.1% and 28%, respectively), relaxation (30.6% and 23.0%, respectively), compression (27.1% and 21%, respectively), and heat (24.7% and 15%, respectively).

Impact of pain on daily life

When completing the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, most patients reported problems with mobility, performing usual activities, and pain or discomfort. However, most patients said they had no problems with self-care (78%) or anxiety/depression (58.5%).

A similar proportion of patients reported slight and moderate pain and discomfort (29.9% and 31.1%, respectively). Pain and discomfort was severe for 11% of patients and extreme for 1.2%, but 26.8% of patients reported no pain or discomfort.

When it came to mobility, patients reported slight (32.3%), moderate (19.5%), and severe (8.5%) problems, and 1.2% of patients said they were unable to get around. However, 38.4% of patients reported having no such problems.

About 44% of patients reported no problems performing usual activities, but 37.2% had slight problems, 14.6% had moderate problems, and 1.8% of patients each had severe problems or were unable to perform usual activities.

For the Brief Pain Inventory, pain severity and interference with daily activities were rated on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain/no interference and 10 being pain as bad as you can imagine/pain that completely interferes with daily life.

The overall median pain severity and pain interference were 3.0 (range, 1.3-4.8) and 2.9 (range, 0.7-5.2), respectively. The median worst pain was 6.0, least pain 2.0, average pain 3.0, and current pain 2.0. Ankles were the most frequently reported site of pain.

When completing the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, 49.3% of patients (73/148) reported no activity in the prior week.

The median SF-36v2 scores were lower for physical health domains than mental health domains, and the overall median health score was 3.0 (range, 2.0-3.0).

The median score on the Hemophilia Activities List was 76.1 (range, 59.2-95.1). And patients said hemophilia had a greater impact on their lower extremities than upper extremities.

Dr Recht and his colleagues said these results substantiate the high prevalence of pain in adults with hemophilia. And the study highlights opportunities to improve the assessment and management of pain in these patients.

Study investigators have received funding/consulting fees from—or are employees/shareholders of—Novo Nordisk, Baxter, Biogen, Bayer, OctaPharma, Pfizer, CSL Behring, Kendrion, Alexion, Grifols, OPKO Health, Sanofi, Merck, and ProMeticLife Sciences. ![]()

PI3Kδ/γ inhibitor generates rapid responses in CLL

VIENNA—New research indicates that duvelisib, a dual inhibitor of PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ, can generate rapid partial responses in treatment-naïve patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The 18 patients in the expansion cohort of a phase 1 study of duvelisib had a median time to response of 3.7 months, according to iwCLL response criteria.

And 47% of the responses occurred by the first assessment on day 1 of cycle 3.

“One thing that does seem to be different with this drug is that you’re getting your [partial responses] a bit faster than you see with some of the other drugs,” said Susan O’Brien, MD, of UC Irvine Health in Orange, California.

“[W]hat that means in the long run is not completely clear, but there’s no question that the responses are very rapid.”

Dr O’Brien presented these findings at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S434*). The research was funded by Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing duvelisib.

Older CLL patients with comorbidities and patients with high-risk genomic alterations, such as 17p deletion and TP53 mutations, often don’t fare well on the standard chemoimmunotherapy. Duvelisib is being developed as a potential alternative for these patients and others with hematologic malignancies.

In the dose-escalation portion of this phase 1 study, duvelisib at 25 mg twice daily was well-tolerated and exhibited clinical activity in relapsed/refractory CLL, even in those patients with TP53 mutations and 17p deletion.

So investigators conducted the expansion cohort with 18 patients who received duvelisib at the same dose in 28-day cycles. Duvelisib is given continuously until patients have an adverse event or lose their response.

Patient demographics

Dr O’Brien said there was nothing unusual about the demographics of the study population, except the risk factors: 83% of the patients were over 65, “which is very different from what you would see in a chemoimmunotherapy trial.”

She noted that the patients’ median age was 74, and 56% of patients had either a 17p deletion or TP53 mutation.

“And that’s very unusual because . . . the percentage of patients with that abnormality in frontline CLL is about 5% to 10%,” she added.

Patients were a median of 3 years (range, 0–9) from their initial diagnosis, 47% had Rai stage 3 or greater disease, 44% had splenomegaly, and 11% had grade 4 cytopenia.

Response

Patients stayed on treatment for a median of 14 months (range, 1–20). Eight (44%) discontinued treatment—6 (33%) due to an adverse event, 1 withdrew consent, and 1 discontinued for other reasons.