User login

Abdominal distention • loss of appetite • elevated creatinine • Dx?

THE CASE

A 21-year-old male college student sought care at our urology clinic for a 2-year history of progressive abdominal distention and loss of appetite due to abdominal pressure. On physical examination, his abdomen was distended and tense, but without any tenderness on palpation or any costovertebral angle tenderness. He had no abdominal or flank pain, and wasn’t in acute distress. His blood pressure was normal.

Initial lab test results were significant for elevated creatinine at 2.7 mg/dL (normal: 0.7-1.3 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at 31.1 mg/dL (normal: 6-20 mg/dL). Results of a complete blood count (CBC) were within normal ranges, including a white blood cell (WBC) count of 7900, hemoglobin level of 15.1 g/dL, and platelet count of 217,000/mcL. A urinalysis showed only a mild increase in the WBC count.

THE DIAGNOSIS

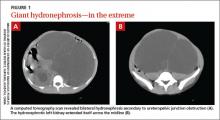

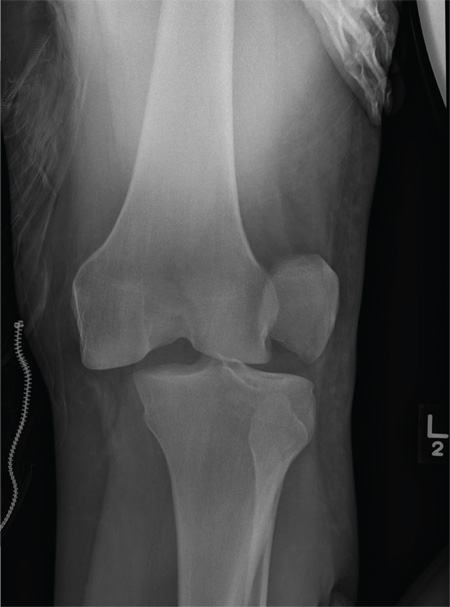

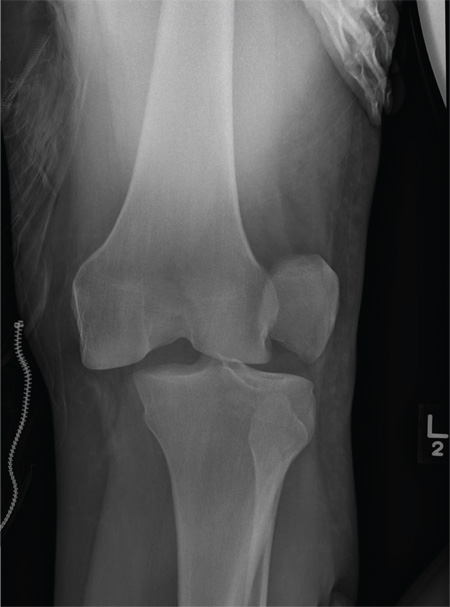

We performed a computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s abdomen, which revealed bilateral hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). The patient’s right kidney was mildly to moderately enlarged, but the left kidney was massive (FIGURE 1A). The hydronephrotic left kidney had extended itself across the midline (FIGURE 1B), pushed the ipsilateral diaphragm upward, and displaced the bladder downward.

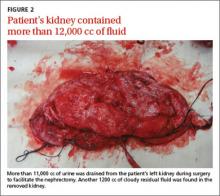

The patient underwent right-sided ureteral stent placement for temporary drainage and a complete left-sided nephrectomy. During the surgery, the left kidney was first aspirated, and more than 11,000 cc of clear urine was drained. (Aspiration reduced the kidney size, allowing the surgeon to make a smaller incision.) The removed kidney contained an additional 1200 cc of cloudy residual fluid (FIGURE 2). UPJO was confirmed by the pathological examination of the excised organ.

DISCUSSION

UPJO is the most common etiology for congenital hydronephrosis.1 Because it can cause little to no pain, hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Frequently, an abdominal mass is the initial clinical presentation.

When the hydronephrotic fluid exceeds 1000 cc, the condition is referred to as giant hydronephrosis.2 Although several cases of giant hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO have been reported in the medical literature,3-5 the volume of the hydronephrotic fluid in these cases rarely exceeded 10,000 cc. We believe our patient may be the most severe case of hydronephrosis secondary to bilateral UPJO, with 12,200 cc of fluid. His condition reached this late stage only because his right kidney retained adequate function.

Diagnosis of hydronephrosis is straightforward with an abdominal ultrasound and/or CT scan. Widespread use of abdominal ultrasound as a screening tool has significantly increased the diagnosis of asymptomatic hydronephrosis, and many cases are secondary to UPJO.6 The true incidence of UPJO is unknown, but it is more prevalent in males than in females, and in 10% to 40% of cases, the condition is bilateral.7 Congenital UPJO typically results from intrinsic pathology of the ureter. The diseased segment is often fibrotic, strictured, and aperistaltic.8

Treatment choice depends on whether renal function can be preserved

Treatment of hydronephrosis is straightforward; when there is little or no salvageable renal function (<10%), a simple nephrectomy is indicated, as was the case for our patient. Nephrectomy can be accomplished by either an open or laparoscopic approach.

When there is salvageable renal function, treatment options include pyeloplasty and pyelotomy. Traditionally, open dismembered pyeloplasty has been the gold standard. However, with advances in endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques, there has been a shift toward minimally invasive procedures. Laparoscopic pyeloplasty—with or without robotic assistance—and endoscopic pyelotomy—with either a percutaneous or retrograde approach—are now typically performed. Ureteral stenting should only be used as a temporary measure.

Our patient. Four weeks after the nephrectomy, our patient underwent a right side pyeloplasty, which was successful. He had an uneventful recovery from both procedures. His renal function stabilized and other than routine follow-up, he required no additional treatment.

THE TAKEAWAY

Most cases of hydronephrosis in young people are due to congenital abnormalities, and UPJO is the leading cause. However, the condition can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Whenever a patient presents with an asymptomatic abdominal mass, hydronephrosis should be part of the differential diagnosis. Treatment options include nephrectomy when there is no salvageable kidney function or pyeloplasty and pyelotomy when some kidney function can be preserved.

1. Brown T, Mandell J, Lebowitz RL. Neonatal hydronephrosis in the era ultrasonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:959-963.

2. Stirling WC. Massive hydronephrosis complicated by hydroureter: Report of 3 cases. J Urol. 1939;42:520.

3. Chiang PH, Chen MT, Chou YH, et al. Giant hydronephrosis: report of 4 cases with review of the literature. J Formos Med Assoc. 1990;89:811-817.

4. Aguiar MFM, Oliveira APS, Silva SC, et al. Giant hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Gazzetta Medica Italiana-Archivio per le Scienze Mediche. 2009;168:207.

5. Sepulveda L, Rodriguesa F. Giant hydronephrosis - a late diagnosis of ureteropelvic junction obstruction. World J Nephrol Urol. 2013;2:33.

6. Bernstein GT, Mandell J, Lebowitz RL, et al. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction in neonate. J Urol. 1988;140:1216-1221.

7. Johnston JH, Evans JP, Glassberg KI, et al. Pelvic hydronephrosis in children: a review of 219 personal cases. J Urol. 1977;117:97-101.

8. Gosling JA, Dixon JS. Functional obstruction of the ureter and renal pelvis. A histological and electron microscopic study. Br J Urol. 1978;50:145-152.

THE CASE

A 21-year-old male college student sought care at our urology clinic for a 2-year history of progressive abdominal distention and loss of appetite due to abdominal pressure. On physical examination, his abdomen was distended and tense, but without any tenderness on palpation or any costovertebral angle tenderness. He had no abdominal or flank pain, and wasn’t in acute distress. His blood pressure was normal.

Initial lab test results were significant for elevated creatinine at 2.7 mg/dL (normal: 0.7-1.3 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at 31.1 mg/dL (normal: 6-20 mg/dL). Results of a complete blood count (CBC) were within normal ranges, including a white blood cell (WBC) count of 7900, hemoglobin level of 15.1 g/dL, and platelet count of 217,000/mcL. A urinalysis showed only a mild increase in the WBC count.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We performed a computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s abdomen, which revealed bilateral hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). The patient’s right kidney was mildly to moderately enlarged, but the left kidney was massive (FIGURE 1A). The hydronephrotic left kidney had extended itself across the midline (FIGURE 1B), pushed the ipsilateral diaphragm upward, and displaced the bladder downward.

The patient underwent right-sided ureteral stent placement for temporary drainage and a complete left-sided nephrectomy. During the surgery, the left kidney was first aspirated, and more than 11,000 cc of clear urine was drained. (Aspiration reduced the kidney size, allowing the surgeon to make a smaller incision.) The removed kidney contained an additional 1200 cc of cloudy residual fluid (FIGURE 2). UPJO was confirmed by the pathological examination of the excised organ.

DISCUSSION

UPJO is the most common etiology for congenital hydronephrosis.1 Because it can cause little to no pain, hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Frequently, an abdominal mass is the initial clinical presentation.

When the hydronephrotic fluid exceeds 1000 cc, the condition is referred to as giant hydronephrosis.2 Although several cases of giant hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO have been reported in the medical literature,3-5 the volume of the hydronephrotic fluid in these cases rarely exceeded 10,000 cc. We believe our patient may be the most severe case of hydronephrosis secondary to bilateral UPJO, with 12,200 cc of fluid. His condition reached this late stage only because his right kidney retained adequate function.

Diagnosis of hydronephrosis is straightforward with an abdominal ultrasound and/or CT scan. Widespread use of abdominal ultrasound as a screening tool has significantly increased the diagnosis of asymptomatic hydronephrosis, and many cases are secondary to UPJO.6 The true incidence of UPJO is unknown, but it is more prevalent in males than in females, and in 10% to 40% of cases, the condition is bilateral.7 Congenital UPJO typically results from intrinsic pathology of the ureter. The diseased segment is often fibrotic, strictured, and aperistaltic.8

Treatment choice depends on whether renal function can be preserved

Treatment of hydronephrosis is straightforward; when there is little or no salvageable renal function (<10%), a simple nephrectomy is indicated, as was the case for our patient. Nephrectomy can be accomplished by either an open or laparoscopic approach.

When there is salvageable renal function, treatment options include pyeloplasty and pyelotomy. Traditionally, open dismembered pyeloplasty has been the gold standard. However, with advances in endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques, there has been a shift toward minimally invasive procedures. Laparoscopic pyeloplasty—with or without robotic assistance—and endoscopic pyelotomy—with either a percutaneous or retrograde approach—are now typically performed. Ureteral stenting should only be used as a temporary measure.

Our patient. Four weeks after the nephrectomy, our patient underwent a right side pyeloplasty, which was successful. He had an uneventful recovery from both procedures. His renal function stabilized and other than routine follow-up, he required no additional treatment.

THE TAKEAWAY

Most cases of hydronephrosis in young people are due to congenital abnormalities, and UPJO is the leading cause. However, the condition can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Whenever a patient presents with an asymptomatic abdominal mass, hydronephrosis should be part of the differential diagnosis. Treatment options include nephrectomy when there is no salvageable kidney function or pyeloplasty and pyelotomy when some kidney function can be preserved.

THE CASE

A 21-year-old male college student sought care at our urology clinic for a 2-year history of progressive abdominal distention and loss of appetite due to abdominal pressure. On physical examination, his abdomen was distended and tense, but without any tenderness on palpation or any costovertebral angle tenderness. He had no abdominal or flank pain, and wasn’t in acute distress. His blood pressure was normal.

Initial lab test results were significant for elevated creatinine at 2.7 mg/dL (normal: 0.7-1.3 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at 31.1 mg/dL (normal: 6-20 mg/dL). Results of a complete blood count (CBC) were within normal ranges, including a white blood cell (WBC) count of 7900, hemoglobin level of 15.1 g/dL, and platelet count of 217,000/mcL. A urinalysis showed only a mild increase in the WBC count.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We performed a computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s abdomen, which revealed bilateral hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). The patient’s right kidney was mildly to moderately enlarged, but the left kidney was massive (FIGURE 1A). The hydronephrotic left kidney had extended itself across the midline (FIGURE 1B), pushed the ipsilateral diaphragm upward, and displaced the bladder downward.

The patient underwent right-sided ureteral stent placement for temporary drainage and a complete left-sided nephrectomy. During the surgery, the left kidney was first aspirated, and more than 11,000 cc of clear urine was drained. (Aspiration reduced the kidney size, allowing the surgeon to make a smaller incision.) The removed kidney contained an additional 1200 cc of cloudy residual fluid (FIGURE 2). UPJO was confirmed by the pathological examination of the excised organ.

DISCUSSION

UPJO is the most common etiology for congenital hydronephrosis.1 Because it can cause little to no pain, hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Frequently, an abdominal mass is the initial clinical presentation.

When the hydronephrotic fluid exceeds 1000 cc, the condition is referred to as giant hydronephrosis.2 Although several cases of giant hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO have been reported in the medical literature,3-5 the volume of the hydronephrotic fluid in these cases rarely exceeded 10,000 cc. We believe our patient may be the most severe case of hydronephrosis secondary to bilateral UPJO, with 12,200 cc of fluid. His condition reached this late stage only because his right kidney retained adequate function.

Diagnosis of hydronephrosis is straightforward with an abdominal ultrasound and/or CT scan. Widespread use of abdominal ultrasound as a screening tool has significantly increased the diagnosis of asymptomatic hydronephrosis, and many cases are secondary to UPJO.6 The true incidence of UPJO is unknown, but it is more prevalent in males than in females, and in 10% to 40% of cases, the condition is bilateral.7 Congenital UPJO typically results from intrinsic pathology of the ureter. The diseased segment is often fibrotic, strictured, and aperistaltic.8

Treatment choice depends on whether renal function can be preserved

Treatment of hydronephrosis is straightforward; when there is little or no salvageable renal function (<10%), a simple nephrectomy is indicated, as was the case for our patient. Nephrectomy can be accomplished by either an open or laparoscopic approach.

When there is salvageable renal function, treatment options include pyeloplasty and pyelotomy. Traditionally, open dismembered pyeloplasty has been the gold standard. However, with advances in endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques, there has been a shift toward minimally invasive procedures. Laparoscopic pyeloplasty—with or without robotic assistance—and endoscopic pyelotomy—with either a percutaneous or retrograde approach—are now typically performed. Ureteral stenting should only be used as a temporary measure.

Our patient. Four weeks after the nephrectomy, our patient underwent a right side pyeloplasty, which was successful. He had an uneventful recovery from both procedures. His renal function stabilized and other than routine follow-up, he required no additional treatment.

THE TAKEAWAY

Most cases of hydronephrosis in young people are due to congenital abnormalities, and UPJO is the leading cause. However, the condition can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Whenever a patient presents with an asymptomatic abdominal mass, hydronephrosis should be part of the differential diagnosis. Treatment options include nephrectomy when there is no salvageable kidney function or pyeloplasty and pyelotomy when some kidney function can be preserved.

1. Brown T, Mandell J, Lebowitz RL. Neonatal hydronephrosis in the era ultrasonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:959-963.

2. Stirling WC. Massive hydronephrosis complicated by hydroureter: Report of 3 cases. J Urol. 1939;42:520.

3. Chiang PH, Chen MT, Chou YH, et al. Giant hydronephrosis: report of 4 cases with review of the literature. J Formos Med Assoc. 1990;89:811-817.

4. Aguiar MFM, Oliveira APS, Silva SC, et al. Giant hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Gazzetta Medica Italiana-Archivio per le Scienze Mediche. 2009;168:207.

5. Sepulveda L, Rodriguesa F. Giant hydronephrosis - a late diagnosis of ureteropelvic junction obstruction. World J Nephrol Urol. 2013;2:33.

6. Bernstein GT, Mandell J, Lebowitz RL, et al. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction in neonate. J Urol. 1988;140:1216-1221.

7. Johnston JH, Evans JP, Glassberg KI, et al. Pelvic hydronephrosis in children: a review of 219 personal cases. J Urol. 1977;117:97-101.

8. Gosling JA, Dixon JS. Functional obstruction of the ureter and renal pelvis. A histological and electron microscopic study. Br J Urol. 1978;50:145-152.

1. Brown T, Mandell J, Lebowitz RL. Neonatal hydronephrosis in the era ultrasonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:959-963.

2. Stirling WC. Massive hydronephrosis complicated by hydroureter: Report of 3 cases. J Urol. 1939;42:520.

3. Chiang PH, Chen MT, Chou YH, et al. Giant hydronephrosis: report of 4 cases with review of the literature. J Formos Med Assoc. 1990;89:811-817.

4. Aguiar MFM, Oliveira APS, Silva SC, et al. Giant hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Gazzetta Medica Italiana-Archivio per le Scienze Mediche. 2009;168:207.

5. Sepulveda L, Rodriguesa F. Giant hydronephrosis - a late diagnosis of ureteropelvic junction obstruction. World J Nephrol Urol. 2013;2:33.

6. Bernstein GT, Mandell J, Lebowitz RL, et al. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction in neonate. J Urol. 1988;140:1216-1221.

7. Johnston JH, Evans JP, Glassberg KI, et al. Pelvic hydronephrosis in children: a review of 219 personal cases. J Urol. 1977;117:97-101.

8. Gosling JA, Dixon JS. Functional obstruction of the ureter and renal pelvis. A histological and electron microscopic study. Br J Urol. 1978;50:145-152.

Novel Rapid Response Team Can Decrease Non-ICU Cardiopulmonary Arrests, Mortality

Clinical question: Can novel configured rapid response teams (RRTs) improve non-ICU cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) and overall hospital mortality rate?

Background: RRTs are primarily executed in hospital settings to avert non-ICU CPA through early detection and intervention. Prevailing evidence has not shown consistent clear benefit of RRTs in this regard.

Study design: A parallel-controlled, before-after design.

Setting: Two urban university hospitals with approximately 500 medical/surgical beds.

Synopsis: Researchers compared annual non-ICU CPA rates from two university hospitals with newly configured RRTs (implemented in November 2007) from July 2005 through June 2011 and found a decline in the incidence of non-ICU CPA to 1.1 from 2.7 per 1000 discharges (P<0.0001) while comparing pre- (2005/2006 to 2006/2007) to post- RRT implementation (2007-2011), respectively. Post-implementation, the overall hospital mortality dropped to 1.74% from 2.12% (P<0.001). With year-over-year, the RRT activation was found to be inversely related to Code Blue activations (r=-0.68, P<0.001), while the case mix index coefficients were still high.

The study lacks internal validation and may carry bias by including just one pre-implementation year (2006) data. It demonstrates that the rounding of unit manager (charge nurse) on “at risk” patients might avert decompensation; however, there was no determination of their decision-making process, with regard to RRT activation. No comparison was done with other RRT configurations.

Bottom line: Novel configured RRTs may improve non-ICU CPA and overall hospital mortality rate.

Citation: Davis DP, Aguilar SA, Graham PG, et al. A novel configuration of a traditional rapid response team decreases non-intensive care unit arrests and overall hospital mortality. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):352-357.

Clinical question: Can novel configured rapid response teams (RRTs) improve non-ICU cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) and overall hospital mortality rate?

Background: RRTs are primarily executed in hospital settings to avert non-ICU CPA through early detection and intervention. Prevailing evidence has not shown consistent clear benefit of RRTs in this regard.

Study design: A parallel-controlled, before-after design.

Setting: Two urban university hospitals with approximately 500 medical/surgical beds.

Synopsis: Researchers compared annual non-ICU CPA rates from two university hospitals with newly configured RRTs (implemented in November 2007) from July 2005 through June 2011 and found a decline in the incidence of non-ICU CPA to 1.1 from 2.7 per 1000 discharges (P<0.0001) while comparing pre- (2005/2006 to 2006/2007) to post- RRT implementation (2007-2011), respectively. Post-implementation, the overall hospital mortality dropped to 1.74% from 2.12% (P<0.001). With year-over-year, the RRT activation was found to be inversely related to Code Blue activations (r=-0.68, P<0.001), while the case mix index coefficients were still high.

The study lacks internal validation and may carry bias by including just one pre-implementation year (2006) data. It demonstrates that the rounding of unit manager (charge nurse) on “at risk” patients might avert decompensation; however, there was no determination of their decision-making process, with regard to RRT activation. No comparison was done with other RRT configurations.

Bottom line: Novel configured RRTs may improve non-ICU CPA and overall hospital mortality rate.

Citation: Davis DP, Aguilar SA, Graham PG, et al. A novel configuration of a traditional rapid response team decreases non-intensive care unit arrests and overall hospital mortality. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):352-357.

Clinical question: Can novel configured rapid response teams (RRTs) improve non-ICU cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) and overall hospital mortality rate?

Background: RRTs are primarily executed in hospital settings to avert non-ICU CPA through early detection and intervention. Prevailing evidence has not shown consistent clear benefit of RRTs in this regard.

Study design: A parallel-controlled, before-after design.

Setting: Two urban university hospitals with approximately 500 medical/surgical beds.

Synopsis: Researchers compared annual non-ICU CPA rates from two university hospitals with newly configured RRTs (implemented in November 2007) from July 2005 through June 2011 and found a decline in the incidence of non-ICU CPA to 1.1 from 2.7 per 1000 discharges (P<0.0001) while comparing pre- (2005/2006 to 2006/2007) to post- RRT implementation (2007-2011), respectively. Post-implementation, the overall hospital mortality dropped to 1.74% from 2.12% (P<0.001). With year-over-year, the RRT activation was found to be inversely related to Code Blue activations (r=-0.68, P<0.001), while the case mix index coefficients were still high.

The study lacks internal validation and may carry bias by including just one pre-implementation year (2006) data. It demonstrates that the rounding of unit manager (charge nurse) on “at risk” patients might avert decompensation; however, there was no determination of their decision-making process, with regard to RRT activation. No comparison was done with other RRT configurations.

Bottom line: Novel configured RRTs may improve non-ICU CPA and overall hospital mortality rate.

Citation: Davis DP, Aguilar SA, Graham PG, et al. A novel configuration of a traditional rapid response team decreases non-intensive care unit arrests and overall hospital mortality. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):352-357.

The art & science of prescribing

› To increase adherence, give patients treatment options, ensure that they participate in discussions of treatment, and empower them to reach "informed collaboration" as opposed to informed consent. A

› Ask patients to tell you in their own words what they understand about the treatment they have chosen. A

› At each follow-up visit, anticipate nonadherence, ask nonjudgmental questions about missed medication doses and sexual adverse effects, and offer simple solutions. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Medication nonadherence is a major—and remediable—contributor to poor outcomes, leading to approximately 125,000 preventable deaths,1 worsening of acute and chronic conditions, and billions of dollars in avoidable costs related to increased hospitalizations and emergency visits each year.2,3 Nonadherence rates are 20% to 30% among patients being treated for cancer and acute illness3 and 50% to 60% for chronic conditions, with an average of 50% of all patients taking their medication incorrectly—or not at all.2,4,5

What’s more, nonadherence disrupts the physician-patient relationship6—a serious problem, given that feeling understood is often the most critical component of recovery.7-9

With that in mind, the words used to describe the problem have changed. Compliance and noncompliance, the older labels, were based on the assumptions that patients are passive recipients of medical advice that they should follow without question and that they are to blame for not doing so. Adherence and nonadherence, on the other hand, emphasize mutual agreement and the patient’s freedom to follow the doctor’s recommendations or not, without blame if he or she decides not to do so.10

Many systemic approaches have been tried to maximize adherence, including disease management (eg, Web-based assessment tools, clinical guidelines, and call center-based triage), smart phone apps11 (for reminders and monitoring), and paying for or subsidizing the cost of drugs for those who can’t afford them. All have met with limited success.12 Based on a thorough review of the literature, we suggest a different approach.

Evidence-based efforts by clinicians are the key to effective prescribing and maximal adherence. In the text and table that follow, we summarize physician and patient factors that influence adherence and present optimal prescribing guidelines.

Listen carefully, then respond

Whether patients are seeing a primary care physician or a specialist, they want their doctors to spend more time with them and to give them more comprehensive information about their condition.13-15 The interaction should begin with the physician listening carefully to the patient before responding, but all too often this is not the case.

Family physicians have been found to interrupt patients 23 seconds after asking a question.16 To improve communication, listen quietly until the patient finishes presenting his or her complaints and agenda for the visit. Then ask, “Is there anything else that’s important for me to know?”17

Be more forthcoming

It is equally important for physicians to respond fully, but this is often not the case. A study involving internists found that in patient encounters lasting 20 minutes, physicians devoted little more than one minute, on average, to explaining the patient’s medical condition. The research showed that many physicians greatly overestimated the time they spent doing so.13

Studies have also shown that clinicians tell patients the name of the drug they’re prescribing 74% of the time and state its purpose 87% of the time, but discuss potential adverse effects and duration of treatment a mere 34% of the time. More than 4 in 10 patients are not told the frequency or timing of doses or the number of tablets to take.18

To improve communication, take the following steps when it’s your turn to talk:

Avoid medical jargon. Technical language (eg, edema) and medical shorthand (eg, history) is a significant barrier to patient understanding. In one study of more than 800 pediatrician visits, such speech was found to be detrimental more than half of the time. Although many mothers were confused by the terms, they rarely asked for clarification.19

It has been suggested that doctors and patients have engaged in a “communication conspiracy.”20 In one study, even after obstetricians and gynecologists had identified terms that they knew their patients did not understand, they continued to use them, and in only 15% of visits where unfamiliar terms were used did the patients admit that they did not understand them.21 Part of the problem may be that patients believe they must be seen as undemanding and compliant if they are to receive optimal attention from their physicians.22

Compounding the problem is the fact that clinicians’ use of highly technical language doubles when they are pressured for time,20 suggesting that this behavior could become more widespread as the demand for greater efficiency on the part of physicians increases.

Simplify the treatment regimen. It also helps to keep treatment regimens as straightforward as possible. Prescribing multiple medications simultaneously or giving patients a more complicated regimen decreases adherence. In one study, adherence rates of 84% were achieved when the regimen called for once-a-day dosing, but dropped to 59% when patients were instructed to take their medication 3 times a day.23

Ask the patient to summarize. Using simple terms and clear, succinct explanations promotes understanding, but asking the patient to summarize what you’ve just said is an ideal way to find out just how much he or she grasped. “What will you tell your family about your diagnosis and treatment?” you might ask, or “Tell me what you plan to do to ensure that you follow the prescribed regimen.”

This is particularly important when patients are not native English speakers or when the news is bad. Patients find it particularly tough to understand difficult messages, such as a poor prognosis,24 and are often unaware of their poor comprehension. This was underscored by a study of emergency department (ED) patients, in which 78% demonstrated deficient comprehension in at least one domain (eg, post-ED care, diagnosis, cause) but only 20% recognized their lack of understanding.25

Asking patients if they have any other questions is a crucial step in ensuring complete understanding.21,26

Take steps to maximize patient recall

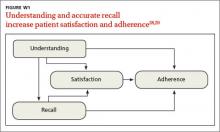

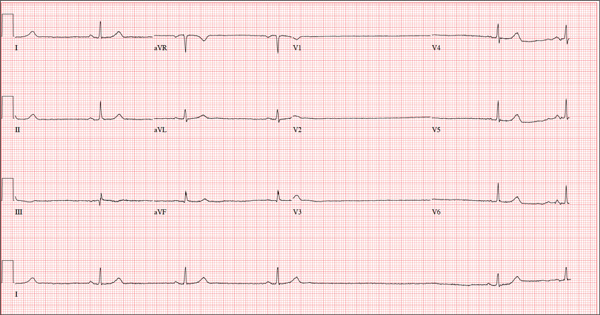

Even when patients understand what they’ve heard, research suggests they may not retain it. Overall, 40% to 80% of medical information is forgotten immediately, and almost half of what is retained is incorrect.27,28 This is a serious problem, as understanding and accurate recall increase patient satisfaction and the likelihood of adherence to treatment (FIGURE W1).28,29

There are 3 basic explanations for poor recall: factors related to the clinician, such as the use of difficult medical terminology; the mode of communication (eg, spoken vs written); and factors related to the patient, such as a low level of education or learning disability.29-32

Being as specific as possible and spending more time explaining the diagnosis and treatment has been shown to enhance patient recall. In an experiment in which patients read advice on how to develop self-control over their eating, the use of simple language and specific instructions, rather than general rules, increased recall.33 Providing generic information by whatever means does little to improve recall and might even inhibit it.

Linking advice to the patient’s chief complaint, thereby creating a “teachable moment,” is also helpful.34 For example, you might tell a patient with a kidney infection that “Your backache is also because of the kidney infection. Both the backache and the burning during urination should be better about 3 days after you start these pills.”

Watch your affect. How relaxed or worried you appear also influences patient recall. In a recent study, 40 women at risk for breast cancer viewed videotapes of an oncologist presenting mammogram results. Compared to women whose results were conveyed by a physician who appeared relaxed, those who had the same findings presented by a physician who seemed worried perceived their clinical situation to be more severe, developed higher anxiety, and recalled significantly less of what they were told.35

Use multiple means of communication. In a comparison study, patients who received verbal lists of actions for managing fever and sore mouth accompanied by pictographs—images that represented the information presented—had a correct recall rate of 85%; those who received the verbal information alone had a recall rate of only 14%.36,37

A review of recall in cancer patients also found that tailoring communication to the individual—providing an audiotape of the consultation, for instance, or having the patient bring a list of questions and addressing them one by one—is most effective.36 Another study assessed the retention of pediatric patients and their parents when they received either a verbal report alone or a verbal report plus written information or visuals. The researchers concluded that children and their parents should receive verbal reports only when such reports are supplemented with written information or visuals.37

The large body of research on learning and memory has proven useful in designing educational materials for those with poor reading skills. When images were used to convey meaning to 21 adults in a job training program—all with less than fifth grade reading skills—they had on average 85% correct recall immediately after the training and 71% recall 4 weeks later. Although the impact on symptom management and patient quality of life has yet to be studied, these findings suggest that pictures can help people with low literacy recall and retain complex information.38

Overall, while written or recorded instructions appear to improve recall in most situations,39 images have been shown to have the greatest impact.36,37,40

Is the patient ready to adhere to treatment?

No matter how well or by what means you communicate, some patients are not ready for change. Patients in the “precontemplation” stage of change—who may not even recognize the need for change, let alone consider it—can benefit from supportive education and motivational interviewing, while those in the “contemplation” stage need support and convincing to reach the “preparation” stage. It is only in the “action” stage, however, that a patient is ready to collaborate with his or her physician in agreeing on and adhering to treatment.40

Comorbid depression is a common condition, particularly in those with chronic illness, and one of the strongest predictors of nonadherence.1,41 Thus, depression screening for all patients who are chronically or severely ill or nonadherent is strongly recommended, followed by treatment when appropriate.41

“Informed collaboration” is critical

Research shows that if both physician and patient agree on the individual’s medical problem, it will be improved or resolved at follow-up in about half of all cases. In contrast, when the physician alone sees the patient’s condition as a problem, just over a quarter of cases improve, regardless of the severity.42 Compounding this difficulty is the finding that patients fail to report up to two-thirds of their most important health problems.43 When physicians identify them, discord and denial typically result.42

Thus, concordance (we prefer the term “informed collaboration”)—an overt agreement reached after a discussion in which the physician shares expert knowledge, then listens to and respects the feelings and beliefs of the patient with regard to how, when, or whether he or she will take the recommended treatment44—is crucial.42,43,45,46

One way to reach informed collaboration is to give patients problem lists or letters summarizing their health problems in simple and specific terms after each visit, in hopes that the written communication will encourage discussion and a physician-patient partnership in addressing them.43 In a recent study of 967 psychiatric outpatients, adherence was significantly higher among those who cited concordance between their preferences and their treatment and felt that they had participated in decision making.47

Problems can arise at any time

Even after a patient starts out fully adhering to his medication regimen, several issues can derail treatment. Inability to afford the medication is one potential problem.48 Adverse effects are another major reason for discontinuation. Sexual dysfunction, caused by a number of drugs, is embarrassing to many patients and frequently goes unaddressed.49 Thus, a patient may stop taking the medication without saying why—seemingly for no apparent reason. The best approach is to ask specifically why it was discontinued, including direct questions about sexual adverse effects.

Prescribing recommendations

We believe that the outcome of treatment is being determined from the moment a patient steps into your office. Thus, we’ve compiled an evidence-based checklist (TABLE)24,33,40,41,47,49,50 with broad areas for discussion that constitute the art and science of prescribing. These fall into 3 main areas: 1) what to say before you write a prescription; 2) how to get patient buy-in (informed collaboration, rather than informed consent) when you’re ready to write the prescription; and 3) what to address to boost the likelihood of continued adherence at follow-up visits.

It is clear that allowing adequate patient participation and arriving at concordance and overt agreement lead to better clinical outcomes.51 The sequential steps we recommend may take a few extra minutes up front, but without them, nonadherence is highly likely. While physicians are supportive of shared decision making in theory, they are often less confident that this is achieved in practice.52,53

It may help to keep in mind that every step need not be carried out by the physician. Using other members of the health care team, such as a nurse, medical assistant, or health coach, to provide patient education and support and take the patient through a number of the steps that are included in a physician visit has become increasingly necessary—and is easily accommodated in this case.

As the physician, you bear the final responsibility to ensure that the critical elements—particularly the overt agreement—are addressed. Ultimately supporting your patient's decision and reinforcing it will ensure continued adherence.

CORRESPONDENCE

Swati Shivale, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, 750 Adams Street, Syracuse, NY 13210; [email protected]

1. Martin LR, Summer LW, Haskard KB, et al. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manage. 2005;1:189-199.

2. Jha AK, Aubert R, Yao J, et al. Greater adherence to diabetes drugs is linked to less hospital use and could save nearly $5 billion annually. Health Aff. 2012;8:1836-1846.

3. DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–209.

4. Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:304-314.

5. Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manage Healthcare Policy. 2014;7:35-44.

6. Ansell B. Not getting to goal: the clinical costs of noncompliance. J Managed Care Pharm. 2008;14(Suppl):6-b.

7. Van Kleef GA, van den Berg H, Heerdink MW. The persuasive power of emotions: effects of emotional expressions on attitude formation and change. J Appl Psychol. 2014. Nov 17 [Epub ahead of print].

8. Wright JM, Lee C, Chambers GK. Real-world effectiveness of antihypertensive drugs. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;162:190–191.

9. Dunbar J, Agras W. Compliance with medical instructions. In: Ferguson J, Taylor C, eds. The Comprehensive Handbook of Behavioral Medicine. New York, NY: Springer; 1980:115–145.

10. Horne R, Weinman J, Barber N, et al. Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine taking. Report for the National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO). December 2005. University of Leeds, School of Healthcare. Available at: http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1412-076_V01.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2015.

11. Dayer L, Heldenbrand S, Anderson P, et al. Smartphone medication adherence apps: potential benefits to patients and providers. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013; 53:172-181.

12. Jaarsma T, van der Wal ML, Lesman-Leegte I, et al. Effect of moderate or intensive disease management program on outcome in patients with heart failure: coordinating study evaluating outcomes of advising and counseling in heart failure (COACH). Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:316-324.

13. Waitzkin H. Doctor-patient communication. Clinical implications of social scientific research. JAMA. 1984;252:2441–2446.

14. Freeman GK, Horder JP, Howie JGR, et al. Evolving general practice consultation in Britain: issues of length and context. BMJ. 2002;324:880-882.

15. Beisecker AE, Beisecker TD. Patient information-seeking behaviors when communicating with doctors. Med Care. 1990;28:19-28.

16. Marvel M, Epstein R, Flowers K, et al. Soliciting the patient’s agenda: have we improved? JAMA. 1999; 281:283-287.

17. Barrier P, Li T, Jensen N. Two words to improve physician-patient communication: what else? Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:211-214.

18. Tarn D, Heritage J, Paterniti D, et al. Physician communications when prescribing new medications. Arch Internal Med. 2006;166:1855-1862.

19. Korsch BM, Gozzi EK, Francis V. Gaps in doctor-patient communication, doctor-patient interaction and patient satisfaction. Pediatrics. 1968;42:855-871.

20. Lipton HL, Svarstad BL. Parental expectations of a multi-disciplinary clinic for children with developmental disabilities. J Health Soc Behav. 1974;15:157-166.

21. McKinlay JB. Who is really ignorant--physician or patient? J Health Soc Behav. 1975;16:3-11.

22. Nehring V, Geach B. Patients’ evaluation of their care: why they don’t complain. Nurs Outlook. 1973; 21:317-321.

23. De las Cuevas C, Peñate W, de Rivera L. To what extent is treatment adherence of psychiatric patients influenced by their participation in shared decision making? Patient Preference Adherence. 2014;8:1547–1553.

24. Tuckett D, Boulton M, Olson C, et al. Meetings Between Experts–An Approach to Sharing Ideas in Medical Consultations. London, UK: Tavistock Publications; 1985.

25. Engel K, Heisler M, Smith D, et al. Patient comprehension of emergency department care and instructions: are patients aware of when they do not understand? Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:454-461.

26. Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:785-795.

27. McGuire LC. Remembering what the doctor said: organization and older adults’ memory for medical information. Exp Aging Res. 1996;22:403-428.

28. Anderson JL, Dodman S, Kopelman M, et al. Patient information recall in a rheumatology clinic. Rheumatol Rehab. 1979;18:18-22.

29. Ley P. Communicating with Patients. New York, NY: Croom Helm; 1988.

30. Ley P. Primacy, rated importance, and the recall of medical statements. J Health Soc Beh. 1972;13:311-317.

31. Ley P, Bradshaw PW, Eaves D, et al. A method for increasing patients’ recall of information presented by doctors. Psychol Med. 1973;3:217-220.

32. Kessels R. Patients’ memory for medical information. J Royal Soc Med. 2003;96:219-222.

33. Bradshaw PW, Ley P, Kincey JA. Recall of medical advice: comprehensibility and specificity. Br J Clin Psychol. 1975;14:55-82.

34. Flocke S, Stange K. Direct observation and patient recall of health behavior advice. Prev Med. 2004;38:34-349.

35. Shapiro DE, Boggs SR, Melamed BG, et al. The effect of varied physician affect on recall, anxiety, and perceptions in women at risk for breast cancer: an analogue study. Health Psychol. 1992;11:61-66.

36. van der Meulen N, Jansen J, van Dulmen S, et al. Interventions to improve recall of medical information in cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2008;17:857-868.

37. Houts PS, Bachrach R, Witmer JT, et al. Using pictographs to enhance recall of spoken medical instructions. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;35:83-88.

38. Watson P, McKinstry B. A systematic review of interventions to improve recall of medical advice in healthcare consultations. J Royal Soc Med. 2009;102:235-243.

39. Houts PS, Witmer JT, Egeth HE, et al. Using pictographs to enhance recall of spoken medical instructions II. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43:231-242.

40. Prochaska J, Norcross J, DiClemente C. Changing for Good. New York, NY: Avon; 1995.

41. DiMatteo M, Lepper H, Croghan T. Depression is a risk factor for non-compliance in medical treatment: a meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression in patient adherence. Arch Int Med. 2000;160: 2101-2107.

42. Starfield B, Wray C, Hess K, et al. The influence of patientpractitioner agreement on outcome of care. Am J Pub Health. 1981;71:127–131.

43. Scheitel SM, Boland BJ, Wollan PC, et al. Patient-physician agreement about medical diagnoses and cardiovascular risk factors in the ambulatory general medical examination. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71: 1131-1137.

44. Bell JS, Airaksinen MS, Lyles A, et al. Concordance is not synonymous with compliance or adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:710-711.

45. Staiger T, Jarvik J, Deyo R, et al. Patient-physician agreement as a predictor of outcomes in patients with back pain. J Gen Int Med. 2005;20:935-937.

46. Stewart M, Brown J, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796-804.

47. Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manage Care. 2009;15:e22–e33.

48. Kedenge SV, Kangwana BP, Waweru EW, et al. Understanding the impact of subsidizing artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) in the retail sector–results from focus group discussions in rural Kenya. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54371.

49. Santini I, De Lauretis I, Roncone R, et al. Psychotropic-associated sexual dysfunctions: a survey of clinical pharmacology and medication-associated practice. Clin Ter. 2014;165:e243-e252.

50. Ibrahim S, Hossam M, Belal D. Study of non-compliance among chronic hemodialysis patients and its impact on patients’ outcomes. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2015;26:243-249.

51. Légaré F, Stacey D, Turcotte S, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(9):CD006732.

52. Cox K, Stevenson F, Britten N, et al. A Systematic Review of Communication between Patients and Healthcare Professionals about Medicine Taking and Prescribing. London, UK: GKT Concordance Unit Kings College; 2004.

53. Edwards A, Elwyn G. Involving patients in decision making and communicating risk: a longitudinal evaluation of doctors’ attitudes and confidence during a randomized trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10:431-437.

› To increase adherence, give patients treatment options, ensure that they participate in discussions of treatment, and empower them to reach "informed collaboration" as opposed to informed consent. A

› Ask patients to tell you in their own words what they understand about the treatment they have chosen. A

› At each follow-up visit, anticipate nonadherence, ask nonjudgmental questions about missed medication doses and sexual adverse effects, and offer simple solutions. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Medication nonadherence is a major—and remediable—contributor to poor outcomes, leading to approximately 125,000 preventable deaths,1 worsening of acute and chronic conditions, and billions of dollars in avoidable costs related to increased hospitalizations and emergency visits each year.2,3 Nonadherence rates are 20% to 30% among patients being treated for cancer and acute illness3 and 50% to 60% for chronic conditions, with an average of 50% of all patients taking their medication incorrectly—or not at all.2,4,5

What’s more, nonadherence disrupts the physician-patient relationship6—a serious problem, given that feeling understood is often the most critical component of recovery.7-9

With that in mind, the words used to describe the problem have changed. Compliance and noncompliance, the older labels, were based on the assumptions that patients are passive recipients of medical advice that they should follow without question and that they are to blame for not doing so. Adherence and nonadherence, on the other hand, emphasize mutual agreement and the patient’s freedom to follow the doctor’s recommendations or not, without blame if he or she decides not to do so.10

Many systemic approaches have been tried to maximize adherence, including disease management (eg, Web-based assessment tools, clinical guidelines, and call center-based triage), smart phone apps11 (for reminders and monitoring), and paying for or subsidizing the cost of drugs for those who can’t afford them. All have met with limited success.12 Based on a thorough review of the literature, we suggest a different approach.

Evidence-based efforts by clinicians are the key to effective prescribing and maximal adherence. In the text and table that follow, we summarize physician and patient factors that influence adherence and present optimal prescribing guidelines.

Listen carefully, then respond

Whether patients are seeing a primary care physician or a specialist, they want their doctors to spend more time with them and to give them more comprehensive information about their condition.13-15 The interaction should begin with the physician listening carefully to the patient before responding, but all too often this is not the case.

Family physicians have been found to interrupt patients 23 seconds after asking a question.16 To improve communication, listen quietly until the patient finishes presenting his or her complaints and agenda for the visit. Then ask, “Is there anything else that’s important for me to know?”17

Be more forthcoming

It is equally important for physicians to respond fully, but this is often not the case. A study involving internists found that in patient encounters lasting 20 minutes, physicians devoted little more than one minute, on average, to explaining the patient’s medical condition. The research showed that many physicians greatly overestimated the time they spent doing so.13

Studies have also shown that clinicians tell patients the name of the drug they’re prescribing 74% of the time and state its purpose 87% of the time, but discuss potential adverse effects and duration of treatment a mere 34% of the time. More than 4 in 10 patients are not told the frequency or timing of doses or the number of tablets to take.18

To improve communication, take the following steps when it’s your turn to talk:

Avoid medical jargon. Technical language (eg, edema) and medical shorthand (eg, history) is a significant barrier to patient understanding. In one study of more than 800 pediatrician visits, such speech was found to be detrimental more than half of the time. Although many mothers were confused by the terms, they rarely asked for clarification.19

It has been suggested that doctors and patients have engaged in a “communication conspiracy.”20 In one study, even after obstetricians and gynecologists had identified terms that they knew their patients did not understand, they continued to use them, and in only 15% of visits where unfamiliar terms were used did the patients admit that they did not understand them.21 Part of the problem may be that patients believe they must be seen as undemanding and compliant if they are to receive optimal attention from their physicians.22

Compounding the problem is the fact that clinicians’ use of highly technical language doubles when they are pressured for time,20 suggesting that this behavior could become more widespread as the demand for greater efficiency on the part of physicians increases.

Simplify the treatment regimen. It also helps to keep treatment regimens as straightforward as possible. Prescribing multiple medications simultaneously or giving patients a more complicated regimen decreases adherence. In one study, adherence rates of 84% were achieved when the regimen called for once-a-day dosing, but dropped to 59% when patients were instructed to take their medication 3 times a day.23

Ask the patient to summarize. Using simple terms and clear, succinct explanations promotes understanding, but asking the patient to summarize what you’ve just said is an ideal way to find out just how much he or she grasped. “What will you tell your family about your diagnosis and treatment?” you might ask, or “Tell me what you plan to do to ensure that you follow the prescribed regimen.”

This is particularly important when patients are not native English speakers or when the news is bad. Patients find it particularly tough to understand difficult messages, such as a poor prognosis,24 and are often unaware of their poor comprehension. This was underscored by a study of emergency department (ED) patients, in which 78% demonstrated deficient comprehension in at least one domain (eg, post-ED care, diagnosis, cause) but only 20% recognized their lack of understanding.25

Asking patients if they have any other questions is a crucial step in ensuring complete understanding.21,26

Take steps to maximize patient recall

Even when patients understand what they’ve heard, research suggests they may not retain it. Overall, 40% to 80% of medical information is forgotten immediately, and almost half of what is retained is incorrect.27,28 This is a serious problem, as understanding and accurate recall increase patient satisfaction and the likelihood of adherence to treatment (FIGURE W1).28,29

There are 3 basic explanations for poor recall: factors related to the clinician, such as the use of difficult medical terminology; the mode of communication (eg, spoken vs written); and factors related to the patient, such as a low level of education or learning disability.29-32

Being as specific as possible and spending more time explaining the diagnosis and treatment has been shown to enhance patient recall. In an experiment in which patients read advice on how to develop self-control over their eating, the use of simple language and specific instructions, rather than general rules, increased recall.33 Providing generic information by whatever means does little to improve recall and might even inhibit it.

Linking advice to the patient’s chief complaint, thereby creating a “teachable moment,” is also helpful.34 For example, you might tell a patient with a kidney infection that “Your backache is also because of the kidney infection. Both the backache and the burning during urination should be better about 3 days after you start these pills.”

Watch your affect. How relaxed or worried you appear also influences patient recall. In a recent study, 40 women at risk for breast cancer viewed videotapes of an oncologist presenting mammogram results. Compared to women whose results were conveyed by a physician who appeared relaxed, those who had the same findings presented by a physician who seemed worried perceived their clinical situation to be more severe, developed higher anxiety, and recalled significantly less of what they were told.35

Use multiple means of communication. In a comparison study, patients who received verbal lists of actions for managing fever and sore mouth accompanied by pictographs—images that represented the information presented—had a correct recall rate of 85%; those who received the verbal information alone had a recall rate of only 14%.36,37

A review of recall in cancer patients also found that tailoring communication to the individual—providing an audiotape of the consultation, for instance, or having the patient bring a list of questions and addressing them one by one—is most effective.36 Another study assessed the retention of pediatric patients and their parents when they received either a verbal report alone or a verbal report plus written information or visuals. The researchers concluded that children and their parents should receive verbal reports only when such reports are supplemented with written information or visuals.37

The large body of research on learning and memory has proven useful in designing educational materials for those with poor reading skills. When images were used to convey meaning to 21 adults in a job training program—all with less than fifth grade reading skills—they had on average 85% correct recall immediately after the training and 71% recall 4 weeks later. Although the impact on symptom management and patient quality of life has yet to be studied, these findings suggest that pictures can help people with low literacy recall and retain complex information.38

Overall, while written or recorded instructions appear to improve recall in most situations,39 images have been shown to have the greatest impact.36,37,40

Is the patient ready to adhere to treatment?

No matter how well or by what means you communicate, some patients are not ready for change. Patients in the “precontemplation” stage of change—who may not even recognize the need for change, let alone consider it—can benefit from supportive education and motivational interviewing, while those in the “contemplation” stage need support and convincing to reach the “preparation” stage. It is only in the “action” stage, however, that a patient is ready to collaborate with his or her physician in agreeing on and adhering to treatment.40

Comorbid depression is a common condition, particularly in those with chronic illness, and one of the strongest predictors of nonadherence.1,41 Thus, depression screening for all patients who are chronically or severely ill or nonadherent is strongly recommended, followed by treatment when appropriate.41

“Informed collaboration” is critical

Research shows that if both physician and patient agree on the individual’s medical problem, it will be improved or resolved at follow-up in about half of all cases. In contrast, when the physician alone sees the patient’s condition as a problem, just over a quarter of cases improve, regardless of the severity.42 Compounding this difficulty is the finding that patients fail to report up to two-thirds of their most important health problems.43 When physicians identify them, discord and denial typically result.42

Thus, concordance (we prefer the term “informed collaboration”)—an overt agreement reached after a discussion in which the physician shares expert knowledge, then listens to and respects the feelings and beliefs of the patient with regard to how, when, or whether he or she will take the recommended treatment44—is crucial.42,43,45,46

One way to reach informed collaboration is to give patients problem lists or letters summarizing their health problems in simple and specific terms after each visit, in hopes that the written communication will encourage discussion and a physician-patient partnership in addressing them.43 In a recent study of 967 psychiatric outpatients, adherence was significantly higher among those who cited concordance between their preferences and their treatment and felt that they had participated in decision making.47

Problems can arise at any time

Even after a patient starts out fully adhering to his medication regimen, several issues can derail treatment. Inability to afford the medication is one potential problem.48 Adverse effects are another major reason for discontinuation. Sexual dysfunction, caused by a number of drugs, is embarrassing to many patients and frequently goes unaddressed.49 Thus, a patient may stop taking the medication without saying why—seemingly for no apparent reason. The best approach is to ask specifically why it was discontinued, including direct questions about sexual adverse effects.

Prescribing recommendations

We believe that the outcome of treatment is being determined from the moment a patient steps into your office. Thus, we’ve compiled an evidence-based checklist (TABLE)24,33,40,41,47,49,50 with broad areas for discussion that constitute the art and science of prescribing. These fall into 3 main areas: 1) what to say before you write a prescription; 2) how to get patient buy-in (informed collaboration, rather than informed consent) when you’re ready to write the prescription; and 3) what to address to boost the likelihood of continued adherence at follow-up visits.

It is clear that allowing adequate patient participation and arriving at concordance and overt agreement lead to better clinical outcomes.51 The sequential steps we recommend may take a few extra minutes up front, but without them, nonadherence is highly likely. While physicians are supportive of shared decision making in theory, they are often less confident that this is achieved in practice.52,53

It may help to keep in mind that every step need not be carried out by the physician. Using other members of the health care team, such as a nurse, medical assistant, or health coach, to provide patient education and support and take the patient through a number of the steps that are included in a physician visit has become increasingly necessary—and is easily accommodated in this case.

As the physician, you bear the final responsibility to ensure that the critical elements—particularly the overt agreement—are addressed. Ultimately supporting your patient's decision and reinforcing it will ensure continued adherence.

CORRESPONDENCE

Swati Shivale, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, 750 Adams Street, Syracuse, NY 13210; [email protected]

› To increase adherence, give patients treatment options, ensure that they participate in discussions of treatment, and empower them to reach "informed collaboration" as opposed to informed consent. A

› Ask patients to tell you in their own words what they understand about the treatment they have chosen. A

› At each follow-up visit, anticipate nonadherence, ask nonjudgmental questions about missed medication doses and sexual adverse effects, and offer simple solutions. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Medication nonadherence is a major—and remediable—contributor to poor outcomes, leading to approximately 125,000 preventable deaths,1 worsening of acute and chronic conditions, and billions of dollars in avoidable costs related to increased hospitalizations and emergency visits each year.2,3 Nonadherence rates are 20% to 30% among patients being treated for cancer and acute illness3 and 50% to 60% for chronic conditions, with an average of 50% of all patients taking their medication incorrectly—or not at all.2,4,5

What’s more, nonadherence disrupts the physician-patient relationship6—a serious problem, given that feeling understood is often the most critical component of recovery.7-9

With that in mind, the words used to describe the problem have changed. Compliance and noncompliance, the older labels, were based on the assumptions that patients are passive recipients of medical advice that they should follow without question and that they are to blame for not doing so. Adherence and nonadherence, on the other hand, emphasize mutual agreement and the patient’s freedom to follow the doctor’s recommendations or not, without blame if he or she decides not to do so.10

Many systemic approaches have been tried to maximize adherence, including disease management (eg, Web-based assessment tools, clinical guidelines, and call center-based triage), smart phone apps11 (for reminders and monitoring), and paying for or subsidizing the cost of drugs for those who can’t afford them. All have met with limited success.12 Based on a thorough review of the literature, we suggest a different approach.

Evidence-based efforts by clinicians are the key to effective prescribing and maximal adherence. In the text and table that follow, we summarize physician and patient factors that influence adherence and present optimal prescribing guidelines.

Listen carefully, then respond

Whether patients are seeing a primary care physician or a specialist, they want their doctors to spend more time with them and to give them more comprehensive information about their condition.13-15 The interaction should begin with the physician listening carefully to the patient before responding, but all too often this is not the case.

Family physicians have been found to interrupt patients 23 seconds after asking a question.16 To improve communication, listen quietly until the patient finishes presenting his or her complaints and agenda for the visit. Then ask, “Is there anything else that’s important for me to know?”17

Be more forthcoming

It is equally important for physicians to respond fully, but this is often not the case. A study involving internists found that in patient encounters lasting 20 minutes, physicians devoted little more than one minute, on average, to explaining the patient’s medical condition. The research showed that many physicians greatly overestimated the time they spent doing so.13

Studies have also shown that clinicians tell patients the name of the drug they’re prescribing 74% of the time and state its purpose 87% of the time, but discuss potential adverse effects and duration of treatment a mere 34% of the time. More than 4 in 10 patients are not told the frequency or timing of doses or the number of tablets to take.18

To improve communication, take the following steps when it’s your turn to talk:

Avoid medical jargon. Technical language (eg, edema) and medical shorthand (eg, history) is a significant barrier to patient understanding. In one study of more than 800 pediatrician visits, such speech was found to be detrimental more than half of the time. Although many mothers were confused by the terms, they rarely asked for clarification.19

It has been suggested that doctors and patients have engaged in a “communication conspiracy.”20 In one study, even after obstetricians and gynecologists had identified terms that they knew their patients did not understand, they continued to use them, and in only 15% of visits where unfamiliar terms were used did the patients admit that they did not understand them.21 Part of the problem may be that patients believe they must be seen as undemanding and compliant if they are to receive optimal attention from their physicians.22

Compounding the problem is the fact that clinicians’ use of highly technical language doubles when they are pressured for time,20 suggesting that this behavior could become more widespread as the demand for greater efficiency on the part of physicians increases.

Simplify the treatment regimen. It also helps to keep treatment regimens as straightforward as possible. Prescribing multiple medications simultaneously or giving patients a more complicated regimen decreases adherence. In one study, adherence rates of 84% were achieved when the regimen called for once-a-day dosing, but dropped to 59% when patients were instructed to take their medication 3 times a day.23

Ask the patient to summarize. Using simple terms and clear, succinct explanations promotes understanding, but asking the patient to summarize what you’ve just said is an ideal way to find out just how much he or she grasped. “What will you tell your family about your diagnosis and treatment?” you might ask, or “Tell me what you plan to do to ensure that you follow the prescribed regimen.”

This is particularly important when patients are not native English speakers or when the news is bad. Patients find it particularly tough to understand difficult messages, such as a poor prognosis,24 and are often unaware of their poor comprehension. This was underscored by a study of emergency department (ED) patients, in which 78% demonstrated deficient comprehension in at least one domain (eg, post-ED care, diagnosis, cause) but only 20% recognized their lack of understanding.25

Asking patients if they have any other questions is a crucial step in ensuring complete understanding.21,26

Take steps to maximize patient recall

Even when patients understand what they’ve heard, research suggests they may not retain it. Overall, 40% to 80% of medical information is forgotten immediately, and almost half of what is retained is incorrect.27,28 This is a serious problem, as understanding and accurate recall increase patient satisfaction and the likelihood of adherence to treatment (FIGURE W1).28,29

There are 3 basic explanations for poor recall: factors related to the clinician, such as the use of difficult medical terminology; the mode of communication (eg, spoken vs written); and factors related to the patient, such as a low level of education or learning disability.29-32

Being as specific as possible and spending more time explaining the diagnosis and treatment has been shown to enhance patient recall. In an experiment in which patients read advice on how to develop self-control over their eating, the use of simple language and specific instructions, rather than general rules, increased recall.33 Providing generic information by whatever means does little to improve recall and might even inhibit it.

Linking advice to the patient’s chief complaint, thereby creating a “teachable moment,” is also helpful.34 For example, you might tell a patient with a kidney infection that “Your backache is also because of the kidney infection. Both the backache and the burning during urination should be better about 3 days after you start these pills.”

Watch your affect. How relaxed or worried you appear also influences patient recall. In a recent study, 40 women at risk for breast cancer viewed videotapes of an oncologist presenting mammogram results. Compared to women whose results were conveyed by a physician who appeared relaxed, those who had the same findings presented by a physician who seemed worried perceived their clinical situation to be more severe, developed higher anxiety, and recalled significantly less of what they were told.35

Use multiple means of communication. In a comparison study, patients who received verbal lists of actions for managing fever and sore mouth accompanied by pictographs—images that represented the information presented—had a correct recall rate of 85%; those who received the verbal information alone had a recall rate of only 14%.36,37

A review of recall in cancer patients also found that tailoring communication to the individual—providing an audiotape of the consultation, for instance, or having the patient bring a list of questions and addressing them one by one—is most effective.36 Another study assessed the retention of pediatric patients and their parents when they received either a verbal report alone or a verbal report plus written information or visuals. The researchers concluded that children and their parents should receive verbal reports only when such reports are supplemented with written information or visuals.37

The large body of research on learning and memory has proven useful in designing educational materials for those with poor reading skills. When images were used to convey meaning to 21 adults in a job training program—all with less than fifth grade reading skills—they had on average 85% correct recall immediately after the training and 71% recall 4 weeks later. Although the impact on symptom management and patient quality of life has yet to be studied, these findings suggest that pictures can help people with low literacy recall and retain complex information.38

Overall, while written or recorded instructions appear to improve recall in most situations,39 images have been shown to have the greatest impact.36,37,40

Is the patient ready to adhere to treatment?

No matter how well or by what means you communicate, some patients are not ready for change. Patients in the “precontemplation” stage of change—who may not even recognize the need for change, let alone consider it—can benefit from supportive education and motivational interviewing, while those in the “contemplation” stage need support and convincing to reach the “preparation” stage. It is only in the “action” stage, however, that a patient is ready to collaborate with his or her physician in agreeing on and adhering to treatment.40

Comorbid depression is a common condition, particularly in those with chronic illness, and one of the strongest predictors of nonadherence.1,41 Thus, depression screening for all patients who are chronically or severely ill or nonadherent is strongly recommended, followed by treatment when appropriate.41

“Informed collaboration” is critical

Research shows that if both physician and patient agree on the individual’s medical problem, it will be improved or resolved at follow-up in about half of all cases. In contrast, when the physician alone sees the patient’s condition as a problem, just over a quarter of cases improve, regardless of the severity.42 Compounding this difficulty is the finding that patients fail to report up to two-thirds of their most important health problems.43 When physicians identify them, discord and denial typically result.42

Thus, concordance (we prefer the term “informed collaboration”)—an overt agreement reached after a discussion in which the physician shares expert knowledge, then listens to and respects the feelings and beliefs of the patient with regard to how, when, or whether he or she will take the recommended treatment44—is crucial.42,43,45,46

One way to reach informed collaboration is to give patients problem lists or letters summarizing their health problems in simple and specific terms after each visit, in hopes that the written communication will encourage discussion and a physician-patient partnership in addressing them.43 In a recent study of 967 psychiatric outpatients, adherence was significantly higher among those who cited concordance between their preferences and their treatment and felt that they had participated in decision making.47

Problems can arise at any time

Even after a patient starts out fully adhering to his medication regimen, several issues can derail treatment. Inability to afford the medication is one potential problem.48 Adverse effects are another major reason for discontinuation. Sexual dysfunction, caused by a number of drugs, is embarrassing to many patients and frequently goes unaddressed.49 Thus, a patient may stop taking the medication without saying why—seemingly for no apparent reason. The best approach is to ask specifically why it was discontinued, including direct questions about sexual adverse effects.

Prescribing recommendations

We believe that the outcome of treatment is being determined from the moment a patient steps into your office. Thus, we’ve compiled an evidence-based checklist (TABLE)24,33,40,41,47,49,50 with broad areas for discussion that constitute the art and science of prescribing. These fall into 3 main areas: 1) what to say before you write a prescription; 2) how to get patient buy-in (informed collaboration, rather than informed consent) when you’re ready to write the prescription; and 3) what to address to boost the likelihood of continued adherence at follow-up visits.

It is clear that allowing adequate patient participation and arriving at concordance and overt agreement lead to better clinical outcomes.51 The sequential steps we recommend may take a few extra minutes up front, but without them, nonadherence is highly likely. While physicians are supportive of shared decision making in theory, they are often less confident that this is achieved in practice.52,53

It may help to keep in mind that every step need not be carried out by the physician. Using other members of the health care team, such as a nurse, medical assistant, or health coach, to provide patient education and support and take the patient through a number of the steps that are included in a physician visit has become increasingly necessary—and is easily accommodated in this case.

As the physician, you bear the final responsibility to ensure that the critical elements—particularly the overt agreement—are addressed. Ultimately supporting your patient's decision and reinforcing it will ensure continued adherence.

CORRESPONDENCE

Swati Shivale, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, 750 Adams Street, Syracuse, NY 13210; [email protected]

1. Martin LR, Summer LW, Haskard KB, et al. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manage. 2005;1:189-199.

2. Jha AK, Aubert R, Yao J, et al. Greater adherence to diabetes drugs is linked to less hospital use and could save nearly $5 billion annually. Health Aff. 2012;8:1836-1846.

3. DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–209.

4. Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:304-314.

5. Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manage Healthcare Policy. 2014;7:35-44.

6. Ansell B. Not getting to goal: the clinical costs of noncompliance. J Managed Care Pharm. 2008;14(Suppl):6-b.

7. Van Kleef GA, van den Berg H, Heerdink MW. The persuasive power of emotions: effects of emotional expressions on attitude formation and change. J Appl Psychol. 2014. Nov 17 [Epub ahead of print].

8. Wright JM, Lee C, Chambers GK. Real-world effectiveness of antihypertensive drugs. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;162:190–191.

9. Dunbar J, Agras W. Compliance with medical instructions. In: Ferguson J, Taylor C, eds. The Comprehensive Handbook of Behavioral Medicine. New York, NY: Springer; 1980:115–145.

10. Horne R, Weinman J, Barber N, et al. Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine taking. Report for the National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO). December 2005. University of Leeds, School of Healthcare. Available at: http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1412-076_V01.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2015.

11. Dayer L, Heldenbrand S, Anderson P, et al. Smartphone medication adherence apps: potential benefits to patients and providers. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013; 53:172-181.