User login

Listen Now: Highlights of the October 2015 Issue of The Hospitalist

This month's issue features Dr. Michael Murphy of ScribeAmerica on the value of scribes in hospital medicine, and Dr. Greg Maynard on Choosing Wisely and hospitalists.

[audio mp3="http://www.the-hospitalist.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2015-October-Hospitalist-Highlights.mp3"][/audio]

This month's issue features Dr. Michael Murphy of ScribeAmerica on the value of scribes in hospital medicine, and Dr. Greg Maynard on Choosing Wisely and hospitalists.

[audio mp3="http://www.the-hospitalist.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2015-October-Hospitalist-Highlights.mp3"][/audio]

This month's issue features Dr. Michael Murphy of ScribeAmerica on the value of scribes in hospital medicine, and Dr. Greg Maynard on Choosing Wisely and hospitalists.

[audio mp3="http://www.the-hospitalist.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2015-October-Hospitalist-Highlights.mp3"][/audio]

Use of Medical Scribes Spurs Debate About Costs, Difficulties of Electronic Health Records

The hospitalists at six Illinois hospitals, physicians who are provided by Best Practices Inpatient Care, were grappling with some issues that might sound familiar to hospitalists around the country. The issues revolved around the electronic health record (EHR).

First, “it’s a pain,” says Jeffry Kreamer, MD, chief executive officer of Best Practices. The Long Grove, Ill.-based practice also wanted EHRs to include notes that were standardized, not limited by a template.

The big issue, however, was job satisfaction.

“Our docs are very smart people. If they would have wanted to do a clerical-type job, they would have done a clerical-type job,” Dr. Kreamer says. “They want to be doctors. They don’t want to be keyboardists.

“It makes no sense to take your most experienced asset, which is our physician, and then deploy them for a clerical task which can be done for a much lower cost.”

That’s where medical scribes come in. Scribes work as assistants to physicians and are responsible for entering information into the medical record with physician oversight. Scribes have a history that goes back a decade in emergency medicine, a setting in which doctors traditionally spend much more time in face-to-face contact with patients than they do in documenting the encounter.

Although scribe use in the emergency medicine and hospital medicine settings is growing, with supporters praising programs for boosting volume and allowing physicians to focus on patient care, not all attempts at using the scribe model of care have worked well. Some suggest scribes are a crutch for cumbersome EHRs and excessive administrative work that most doctors would prefer not to deal with.

Dr. Kreamer, however, says the majority of his scribe programs are tapping into a growing segment of the medical industry. There are now more than 15,000 scribes represented by the American College of Medical Scribe Specialists, and the numbers are increasing along a steep curve. There are still far more scribes working in EDs than alongside hospitalists, but as their track record in the inpatient setting lengthens, the number of inpatient scribes is likely to continue to grow.

Dr. Kreamer sensed that scribes would work as well in the inpatient setting as in the ED—maybe even better. He got in touch with the head of ScribeAmerica, the company that provides most of the scribes that work in U.S. hospitals.

ScribeAmerica had been providing scribes to hospitals for use in the inpatient setting, but in a limited way. With Dr. Kreamer’s input, the company developed a more elaborate plan to provide medical scribes for hospitalist programs.

Dr. Kreamer says scribes save his groups’ hospitalists a little more than 10 minutes per chart, or about three hours of productivity per day on a typical 18-patient census. There’s also less physician fatigue, and documentation is better, he adds.

Michael Murphy, MD, an emergency medicine physician by training and co-founder of ScribeAmerica, was introduced to the scribe concept when he was an undergraduate in California. He was asked to start a scribe program by a friend who was a physician and an attorney.

“The overwhelming benefit that I saw was that, A) Physicians were super-happy when they had a scribe,” says Dr. Murphy, now CEO of ScribeAmerica. “B) The patients were happy. The docs sat down and did different things,” allowing more interaction.

“We saw that huge benefit and said, ‘Why don’t we start this on a national level?’”

In 2004, ScribeAmerica was launched. It expanded to 32 hospitals through 2009. Since then, its client base has exploded to 610 hospitals.

Success Story

An early adopter of hospital medicine scribes was Rochester General. Researchers there performed a 10-month study evaluating length of stay of patients who were admitted using a “patient-centered admission team,” (PCAT), which included a scribe, a physician, a clinical pharmacist, two nurses, and a patient care technician.1 The team has a dedicated workspace near the ED and follows a standardized admission process—part of which involves the scribe entering history and exam findings into the system as the physician explains to the patient what he has found during the exam.

The process also involves the physician simultaneously completing orders while the pharmacist receives pertinent information from the patient, along with other pre-determined steps.

Researchers compared about 2,200 admissions done using this PCAT process and about 6,000 that didn’t use the process; results showed the average length of stay for the PCAT patients was 0.18 days less than the non-PCAT group.1

An analysis of lllinois hospitals in Dr. Kreamer’s Best Practices group found the use of scribes led to a dramatic increase in the case mix index (CMI), a measure of the level of complexity of care that relates to the reimbursements hospitals receive. In the first year using scribes, the CMI increased by 0.26, helping to boost revenue by tens of thousands of dollars, Dr. Murphy says.

The reason for the increase is that when scribes document in real time, the accuracy and detail on the care provided increase, Dr. Murphy says. With fewer omissions and clearer notes, CMIs show a greater level of care complexity. At a tertiary hospital in the Midwest, the CMI was 1.1 but should have been 1.7, Dr. Murphy explains.

“These physicians are so busy and don’t really have an incentive to document,” Dr. Murphy adds. “They’re just surprised and shocked that, how could they be so inefficient, but they are.”

Scribes are typically pre-professionals, he says, who eventually become the next generation of doctors, nurses, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. They receive three to four weeks of a mix of online, classroom, and hands-on clinical training. They also have a monthly continuing scribe education requirement.

Their schedules tend to match the schedules of the physicians with whom they work. Some are paid hourly, and some are salaried, he says.

Since the first hospitalist program was added to ScribeAmerica’s rolls, the number has grown to 40 programs.

“What a lot of hospitalist programs are doing is they’re saying, ‘Look, you can’t document for three hours by yourself. We just can’t afford that, because that means we have to have two to three extra docs on staff just to allow you to do what you’re doing,’” Dr. Murphy says, noting that scribes allow hospitalists “to document in sequence while you’re seeing the patients.”

Imperfect Solution

The use of scribes has not been a slam-dunk for every hospitalist program that has considered them, though. At TeamHealth, the national management firm that provides both emergency physicians and hospitalists, medical scribes have been used for years in EDs, and to great effect, says Jasen Gundersen, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, president of the acute care service division.

TeamHealth uses scribes from PhysAssist, which it now owns, along with a few other scribe providers.

“If we can allow our providers to spend more time with their patients and less time on paperwork and documentation, we can not only allow them to see more patients but spend more quality time at the bedside and less at the computer screen,” Dr. Gundersen says.

But when TeamHealth ran numbers to explore scribes in its hospitalist programs, they found that it likely doesn’t make sense in most markets.

“We have investigated several programs and pilots but have not been able to demonstrate a significant uptick in productivity to justify the costs of the scribes,” Dr. Gundersen explains. “That does not mean that scribes is not a workable model; it just requires a better review and adjustment of workflow. Our ED colleagues have had more time to deal with these adjustments and are able to demonstrate the necessary productivity changes.”

Scribes also would mean a fundamental shift in the function of a typical TeamHealth hospitalist, he says. Most studies show that hospitalists can spend less than a quarter of their time on direct patient care, and Dr. Gundersen says TeamHealth is actively working on new pilots and programs for implementing scribes.

“There is an appetite from our physicians looking for the efficiency that we just haven’t seen before,” he says. “I think that is where we are going to see the program’s success. It must be embraced and driven from the providers.

“We are also facing physician shortages in several markets. Scribes have the potential to extend the current provider workforce and improve quality of life for our doctors.”

A well-run scribe program, he says, has the potential “to bring the provider back to the bedside and with the patient where they belong.”

Shifting Savings?

Kendall Rogers, MD, CPE, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Health IT Committee and associate professor and chief of the hospital medicine division at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, says he checked with colleagues at SHM and did not get much feedback on the use of scribes. His own center, he says, has “not even considered scribes.”

“I have not given it a lot of thought, though my initial impressions are if the EHR was better designed, there would be no need for scribes,” he says. “My hope would be to put our efforts there first. I think scribes are merely a coping mechanism for poorly designed documentation processes within existing EHRs.”

There are also some broader concerns about the potential effect of scribes on EHRs. In a recent op-ed in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a Texas physician sounded concerns that the use of scribes could stunt the evolution of better EHRs, since scribes can be used as a kind of workaround, lessening the demands for EHR improvements.2

“Use of medical scribes to relieve physicians from using EHRs may limit this process by increasing physician acceptance of and satisfaction with an inferior product,” wrote George Gellert, MD, MPH, MPA, regional medical informatics officer at CHRISTUS Santa Rosa Health System in San Antonio.

Dr. Gellert wrote that while The Joint Commission prohibits scribes from performing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), an “unintended functional creep” could arise.

“Even physicians who understand that prohibition may, under pressure of a busy practice, ask a scribe to enter verbal orders,” he wrote, adding that this is something that can’t be monitored by the Joint Commission.

Dr. Murphy says those concerns are unfounded. In a response letter not yet published, he wrote, “Can you honestly believe that the small minority of providers who find EHR acceptable due to scribes are what is preventing EHR companies from making improvements? No, it is as a result of system and technology limitations.”

On scribes being used beyond their scope, Dr. Murphy says there will always be “‘bad actors’ willing to act outside of accepted industry norms; however, that does not mean that TJC [The Joint Commission] does not have control over the industry.”

SHM has not taken a position on the value or potential value of scribes in the inpatient setting.

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- Bansal A, Bejerano RL, Cashimere CK, Polashenski WA, Jr. Reducing length of stay by using standardized admission process: retrospective analysis of 11,249 patients [abstract]. Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting 2015. Accessed September 10, 2015.

- Gellert GA, Ramirez R, Webster SL. The rise of the medical scribe industry: implications for the advancement of electronic health records JAMA. 2015;313(13):1315-1316.

The hospitalists at six Illinois hospitals, physicians who are provided by Best Practices Inpatient Care, were grappling with some issues that might sound familiar to hospitalists around the country. The issues revolved around the electronic health record (EHR).

First, “it’s a pain,” says Jeffry Kreamer, MD, chief executive officer of Best Practices. The Long Grove, Ill.-based practice also wanted EHRs to include notes that were standardized, not limited by a template.

The big issue, however, was job satisfaction.

“Our docs are very smart people. If they would have wanted to do a clerical-type job, they would have done a clerical-type job,” Dr. Kreamer says. “They want to be doctors. They don’t want to be keyboardists.

“It makes no sense to take your most experienced asset, which is our physician, and then deploy them for a clerical task which can be done for a much lower cost.”

That’s where medical scribes come in. Scribes work as assistants to physicians and are responsible for entering information into the medical record with physician oversight. Scribes have a history that goes back a decade in emergency medicine, a setting in which doctors traditionally spend much more time in face-to-face contact with patients than they do in documenting the encounter.

Although scribe use in the emergency medicine and hospital medicine settings is growing, with supporters praising programs for boosting volume and allowing physicians to focus on patient care, not all attempts at using the scribe model of care have worked well. Some suggest scribes are a crutch for cumbersome EHRs and excessive administrative work that most doctors would prefer not to deal with.

Dr. Kreamer, however, says the majority of his scribe programs are tapping into a growing segment of the medical industry. There are now more than 15,000 scribes represented by the American College of Medical Scribe Specialists, and the numbers are increasing along a steep curve. There are still far more scribes working in EDs than alongside hospitalists, but as their track record in the inpatient setting lengthens, the number of inpatient scribes is likely to continue to grow.

Dr. Kreamer sensed that scribes would work as well in the inpatient setting as in the ED—maybe even better. He got in touch with the head of ScribeAmerica, the company that provides most of the scribes that work in U.S. hospitals.

ScribeAmerica had been providing scribes to hospitals for use in the inpatient setting, but in a limited way. With Dr. Kreamer’s input, the company developed a more elaborate plan to provide medical scribes for hospitalist programs.

Dr. Kreamer says scribes save his groups’ hospitalists a little more than 10 minutes per chart, or about three hours of productivity per day on a typical 18-patient census. There’s also less physician fatigue, and documentation is better, he adds.

Michael Murphy, MD, an emergency medicine physician by training and co-founder of ScribeAmerica, was introduced to the scribe concept when he was an undergraduate in California. He was asked to start a scribe program by a friend who was a physician and an attorney.

“The overwhelming benefit that I saw was that, A) Physicians were super-happy when they had a scribe,” says Dr. Murphy, now CEO of ScribeAmerica. “B) The patients were happy. The docs sat down and did different things,” allowing more interaction.

“We saw that huge benefit and said, ‘Why don’t we start this on a national level?’”

In 2004, ScribeAmerica was launched. It expanded to 32 hospitals through 2009. Since then, its client base has exploded to 610 hospitals.

Success Story

An early adopter of hospital medicine scribes was Rochester General. Researchers there performed a 10-month study evaluating length of stay of patients who were admitted using a “patient-centered admission team,” (PCAT), which included a scribe, a physician, a clinical pharmacist, two nurses, and a patient care technician.1 The team has a dedicated workspace near the ED and follows a standardized admission process—part of which involves the scribe entering history and exam findings into the system as the physician explains to the patient what he has found during the exam.

The process also involves the physician simultaneously completing orders while the pharmacist receives pertinent information from the patient, along with other pre-determined steps.

Researchers compared about 2,200 admissions done using this PCAT process and about 6,000 that didn’t use the process; results showed the average length of stay for the PCAT patients was 0.18 days less than the non-PCAT group.1

An analysis of lllinois hospitals in Dr. Kreamer’s Best Practices group found the use of scribes led to a dramatic increase in the case mix index (CMI), a measure of the level of complexity of care that relates to the reimbursements hospitals receive. In the first year using scribes, the CMI increased by 0.26, helping to boost revenue by tens of thousands of dollars, Dr. Murphy says.

The reason for the increase is that when scribes document in real time, the accuracy and detail on the care provided increase, Dr. Murphy says. With fewer omissions and clearer notes, CMIs show a greater level of care complexity. At a tertiary hospital in the Midwest, the CMI was 1.1 but should have been 1.7, Dr. Murphy explains.

“These physicians are so busy and don’t really have an incentive to document,” Dr. Murphy adds. “They’re just surprised and shocked that, how could they be so inefficient, but they are.”

Scribes are typically pre-professionals, he says, who eventually become the next generation of doctors, nurses, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. They receive three to four weeks of a mix of online, classroom, and hands-on clinical training. They also have a monthly continuing scribe education requirement.

Their schedules tend to match the schedules of the physicians with whom they work. Some are paid hourly, and some are salaried, he says.

Since the first hospitalist program was added to ScribeAmerica’s rolls, the number has grown to 40 programs.

“What a lot of hospitalist programs are doing is they’re saying, ‘Look, you can’t document for three hours by yourself. We just can’t afford that, because that means we have to have two to three extra docs on staff just to allow you to do what you’re doing,’” Dr. Murphy says, noting that scribes allow hospitalists “to document in sequence while you’re seeing the patients.”

Imperfect Solution

The use of scribes has not been a slam-dunk for every hospitalist program that has considered them, though. At TeamHealth, the national management firm that provides both emergency physicians and hospitalists, medical scribes have been used for years in EDs, and to great effect, says Jasen Gundersen, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, president of the acute care service division.

TeamHealth uses scribes from PhysAssist, which it now owns, along with a few other scribe providers.

“If we can allow our providers to spend more time with their patients and less time on paperwork and documentation, we can not only allow them to see more patients but spend more quality time at the bedside and less at the computer screen,” Dr. Gundersen says.

But when TeamHealth ran numbers to explore scribes in its hospitalist programs, they found that it likely doesn’t make sense in most markets.

“We have investigated several programs and pilots but have not been able to demonstrate a significant uptick in productivity to justify the costs of the scribes,” Dr. Gundersen explains. “That does not mean that scribes is not a workable model; it just requires a better review and adjustment of workflow. Our ED colleagues have had more time to deal with these adjustments and are able to demonstrate the necessary productivity changes.”

Scribes also would mean a fundamental shift in the function of a typical TeamHealth hospitalist, he says. Most studies show that hospitalists can spend less than a quarter of their time on direct patient care, and Dr. Gundersen says TeamHealth is actively working on new pilots and programs for implementing scribes.

“There is an appetite from our physicians looking for the efficiency that we just haven’t seen before,” he says. “I think that is where we are going to see the program’s success. It must be embraced and driven from the providers.

“We are also facing physician shortages in several markets. Scribes have the potential to extend the current provider workforce and improve quality of life for our doctors.”

A well-run scribe program, he says, has the potential “to bring the provider back to the bedside and with the patient where they belong.”

Shifting Savings?

Kendall Rogers, MD, CPE, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Health IT Committee and associate professor and chief of the hospital medicine division at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, says he checked with colleagues at SHM and did not get much feedback on the use of scribes. His own center, he says, has “not even considered scribes.”

“I have not given it a lot of thought, though my initial impressions are if the EHR was better designed, there would be no need for scribes,” he says. “My hope would be to put our efforts there first. I think scribes are merely a coping mechanism for poorly designed documentation processes within existing EHRs.”

There are also some broader concerns about the potential effect of scribes on EHRs. In a recent op-ed in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a Texas physician sounded concerns that the use of scribes could stunt the evolution of better EHRs, since scribes can be used as a kind of workaround, lessening the demands for EHR improvements.2

“Use of medical scribes to relieve physicians from using EHRs may limit this process by increasing physician acceptance of and satisfaction with an inferior product,” wrote George Gellert, MD, MPH, MPA, regional medical informatics officer at CHRISTUS Santa Rosa Health System in San Antonio.

Dr. Gellert wrote that while The Joint Commission prohibits scribes from performing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), an “unintended functional creep” could arise.

“Even physicians who understand that prohibition may, under pressure of a busy practice, ask a scribe to enter verbal orders,” he wrote, adding that this is something that can’t be monitored by the Joint Commission.

Dr. Murphy says those concerns are unfounded. In a response letter not yet published, he wrote, “Can you honestly believe that the small minority of providers who find EHR acceptable due to scribes are what is preventing EHR companies from making improvements? No, it is as a result of system and technology limitations.”

On scribes being used beyond their scope, Dr. Murphy says there will always be “‘bad actors’ willing to act outside of accepted industry norms; however, that does not mean that TJC [The Joint Commission] does not have control over the industry.”

SHM has not taken a position on the value or potential value of scribes in the inpatient setting.

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- Bansal A, Bejerano RL, Cashimere CK, Polashenski WA, Jr. Reducing length of stay by using standardized admission process: retrospective analysis of 11,249 patients [abstract]. Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting 2015. Accessed September 10, 2015.

- Gellert GA, Ramirez R, Webster SL. The rise of the medical scribe industry: implications for the advancement of electronic health records JAMA. 2015;313(13):1315-1316.

The hospitalists at six Illinois hospitals, physicians who are provided by Best Practices Inpatient Care, were grappling with some issues that might sound familiar to hospitalists around the country. The issues revolved around the electronic health record (EHR).

First, “it’s a pain,” says Jeffry Kreamer, MD, chief executive officer of Best Practices. The Long Grove, Ill.-based practice also wanted EHRs to include notes that were standardized, not limited by a template.

The big issue, however, was job satisfaction.

“Our docs are very smart people. If they would have wanted to do a clerical-type job, they would have done a clerical-type job,” Dr. Kreamer says. “They want to be doctors. They don’t want to be keyboardists.

“It makes no sense to take your most experienced asset, which is our physician, and then deploy them for a clerical task which can be done for a much lower cost.”

That’s where medical scribes come in. Scribes work as assistants to physicians and are responsible for entering information into the medical record with physician oversight. Scribes have a history that goes back a decade in emergency medicine, a setting in which doctors traditionally spend much more time in face-to-face contact with patients than they do in documenting the encounter.

Although scribe use in the emergency medicine and hospital medicine settings is growing, with supporters praising programs for boosting volume and allowing physicians to focus on patient care, not all attempts at using the scribe model of care have worked well. Some suggest scribes are a crutch for cumbersome EHRs and excessive administrative work that most doctors would prefer not to deal with.

Dr. Kreamer, however, says the majority of his scribe programs are tapping into a growing segment of the medical industry. There are now more than 15,000 scribes represented by the American College of Medical Scribe Specialists, and the numbers are increasing along a steep curve. There are still far more scribes working in EDs than alongside hospitalists, but as their track record in the inpatient setting lengthens, the number of inpatient scribes is likely to continue to grow.

Dr. Kreamer sensed that scribes would work as well in the inpatient setting as in the ED—maybe even better. He got in touch with the head of ScribeAmerica, the company that provides most of the scribes that work in U.S. hospitals.

ScribeAmerica had been providing scribes to hospitals for use in the inpatient setting, but in a limited way. With Dr. Kreamer’s input, the company developed a more elaborate plan to provide medical scribes for hospitalist programs.

Dr. Kreamer says scribes save his groups’ hospitalists a little more than 10 minutes per chart, or about three hours of productivity per day on a typical 18-patient census. There’s also less physician fatigue, and documentation is better, he adds.

Michael Murphy, MD, an emergency medicine physician by training and co-founder of ScribeAmerica, was introduced to the scribe concept when he was an undergraduate in California. He was asked to start a scribe program by a friend who was a physician and an attorney.

“The overwhelming benefit that I saw was that, A) Physicians were super-happy when they had a scribe,” says Dr. Murphy, now CEO of ScribeAmerica. “B) The patients were happy. The docs sat down and did different things,” allowing more interaction.

“We saw that huge benefit and said, ‘Why don’t we start this on a national level?’”

In 2004, ScribeAmerica was launched. It expanded to 32 hospitals through 2009. Since then, its client base has exploded to 610 hospitals.

Success Story

An early adopter of hospital medicine scribes was Rochester General. Researchers there performed a 10-month study evaluating length of stay of patients who were admitted using a “patient-centered admission team,” (PCAT), which included a scribe, a physician, a clinical pharmacist, two nurses, and a patient care technician.1 The team has a dedicated workspace near the ED and follows a standardized admission process—part of which involves the scribe entering history and exam findings into the system as the physician explains to the patient what he has found during the exam.

The process also involves the physician simultaneously completing orders while the pharmacist receives pertinent information from the patient, along with other pre-determined steps.

Researchers compared about 2,200 admissions done using this PCAT process and about 6,000 that didn’t use the process; results showed the average length of stay for the PCAT patients was 0.18 days less than the non-PCAT group.1

An analysis of lllinois hospitals in Dr. Kreamer’s Best Practices group found the use of scribes led to a dramatic increase in the case mix index (CMI), a measure of the level of complexity of care that relates to the reimbursements hospitals receive. In the first year using scribes, the CMI increased by 0.26, helping to boost revenue by tens of thousands of dollars, Dr. Murphy says.

The reason for the increase is that when scribes document in real time, the accuracy and detail on the care provided increase, Dr. Murphy says. With fewer omissions and clearer notes, CMIs show a greater level of care complexity. At a tertiary hospital in the Midwest, the CMI was 1.1 but should have been 1.7, Dr. Murphy explains.

“These physicians are so busy and don’t really have an incentive to document,” Dr. Murphy adds. “They’re just surprised and shocked that, how could they be so inefficient, but they are.”

Scribes are typically pre-professionals, he says, who eventually become the next generation of doctors, nurses, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. They receive three to four weeks of a mix of online, classroom, and hands-on clinical training. They also have a monthly continuing scribe education requirement.

Their schedules tend to match the schedules of the physicians with whom they work. Some are paid hourly, and some are salaried, he says.

Since the first hospitalist program was added to ScribeAmerica’s rolls, the number has grown to 40 programs.

“What a lot of hospitalist programs are doing is they’re saying, ‘Look, you can’t document for three hours by yourself. We just can’t afford that, because that means we have to have two to three extra docs on staff just to allow you to do what you’re doing,’” Dr. Murphy says, noting that scribes allow hospitalists “to document in sequence while you’re seeing the patients.”

Imperfect Solution

The use of scribes has not been a slam-dunk for every hospitalist program that has considered them, though. At TeamHealth, the national management firm that provides both emergency physicians and hospitalists, medical scribes have been used for years in EDs, and to great effect, says Jasen Gundersen, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, president of the acute care service division.

TeamHealth uses scribes from PhysAssist, which it now owns, along with a few other scribe providers.

“If we can allow our providers to spend more time with their patients and less time on paperwork and documentation, we can not only allow them to see more patients but spend more quality time at the bedside and less at the computer screen,” Dr. Gundersen says.

But when TeamHealth ran numbers to explore scribes in its hospitalist programs, they found that it likely doesn’t make sense in most markets.

“We have investigated several programs and pilots but have not been able to demonstrate a significant uptick in productivity to justify the costs of the scribes,” Dr. Gundersen explains. “That does not mean that scribes is not a workable model; it just requires a better review and adjustment of workflow. Our ED colleagues have had more time to deal with these adjustments and are able to demonstrate the necessary productivity changes.”

Scribes also would mean a fundamental shift in the function of a typical TeamHealth hospitalist, he says. Most studies show that hospitalists can spend less than a quarter of their time on direct patient care, and Dr. Gundersen says TeamHealth is actively working on new pilots and programs for implementing scribes.

“There is an appetite from our physicians looking for the efficiency that we just haven’t seen before,” he says. “I think that is where we are going to see the program’s success. It must be embraced and driven from the providers.

“We are also facing physician shortages in several markets. Scribes have the potential to extend the current provider workforce and improve quality of life for our doctors.”

A well-run scribe program, he says, has the potential “to bring the provider back to the bedside and with the patient where they belong.”

Shifting Savings?

Kendall Rogers, MD, CPE, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Health IT Committee and associate professor and chief of the hospital medicine division at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, says he checked with colleagues at SHM and did not get much feedback on the use of scribes. His own center, he says, has “not even considered scribes.”

“I have not given it a lot of thought, though my initial impressions are if the EHR was better designed, there would be no need for scribes,” he says. “My hope would be to put our efforts there first. I think scribes are merely a coping mechanism for poorly designed documentation processes within existing EHRs.”

There are also some broader concerns about the potential effect of scribes on EHRs. In a recent op-ed in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a Texas physician sounded concerns that the use of scribes could stunt the evolution of better EHRs, since scribes can be used as a kind of workaround, lessening the demands for EHR improvements.2

“Use of medical scribes to relieve physicians from using EHRs may limit this process by increasing physician acceptance of and satisfaction with an inferior product,” wrote George Gellert, MD, MPH, MPA, regional medical informatics officer at CHRISTUS Santa Rosa Health System in San Antonio.

Dr. Gellert wrote that while The Joint Commission prohibits scribes from performing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), an “unintended functional creep” could arise.

“Even physicians who understand that prohibition may, under pressure of a busy practice, ask a scribe to enter verbal orders,” he wrote, adding that this is something that can’t be monitored by the Joint Commission.

Dr. Murphy says those concerns are unfounded. In a response letter not yet published, he wrote, “Can you honestly believe that the small minority of providers who find EHR acceptable due to scribes are what is preventing EHR companies from making improvements? No, it is as a result of system and technology limitations.”

On scribes being used beyond their scope, Dr. Murphy says there will always be “‘bad actors’ willing to act outside of accepted industry norms; however, that does not mean that TJC [The Joint Commission] does not have control over the industry.”

SHM has not taken a position on the value or potential value of scribes in the inpatient setting.

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- Bansal A, Bejerano RL, Cashimere CK, Polashenski WA, Jr. Reducing length of stay by using standardized admission process: retrospective analysis of 11,249 patients [abstract]. Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting 2015. Accessed September 10, 2015.

- Gellert GA, Ramirez R, Webster SL. The rise of the medical scribe industry: implications for the advancement of electronic health records JAMA. 2015;313(13):1315-1316.

10 Things Geriatricians Want Hospitalists to Know

How many octogenarians do you treat in a year? Nonagenarians? Centenarians? How much have their numbers increased over the last two decades? In the wake of the fabled “silver tsunami,” more than 40% of adult inpatients are aged 65 years or older. By 2030, more than 70 million Americans will have joined the ranks of senior citizens.

Members of this group often have multiple chronic conditions that may require hospitalization as many as 10 times per year.1 Others appear in the ED after falls or suffering from cardiovascular conditions or infection.2

The Hospitalist surveyed seasoned geriatricians for their advice on treating this highly specialized and rapidly growing population, and compiled a list of 10 things these specialists believe hospitalists should know.

1 All physicians should be educated in the basics of geriatric care.

Wayne McCormick, MD, MPH, a geriatrician on the Inpatient Palliative and Supportive Care Consultation Team at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, notes that with the explosion of the aging population in the U.S., it is impossible to train enough geriatricians to care for every elderly hospital inpatient, so hospitalists need to increase their knowledge base of geriatric issues.

“To ensure that elderly patients receive good care suited to their specific needs, there need to be 10 times as many geriatrics-savvy internal medicine physicians as board-certified geriatricians,”Dr. McCormick says. “That way, elderly patients can find good primary, if not specialized, geriatric care.”

Dr. McCormick recommends the resources of the American Geriatrics Society, which includes fellowships on geriatric issues, conferences, and educational material on its website.

2 Sometimes the disease is not the most important focus—maintaining the patient’s function is.

Kenneth Covinsky, MD, MPH, division of geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco, says that, many times, geriatric patients are “admitted for pneumonia or heart failure, and, during their stay, the condition improves; however, the person who came in walking and able to perform activities of daily living on their own leaves unable to function.”

It is easy to see how hospital stays work against maintaining function in the elderly. An important part of maintaining function is encouraging mobility, but, according to Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, FACP, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University and associate chief of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, this does not happen enough.

“Most older adults spend the majority of their days in the hospital in bed, even when they are able to walk independently,” she says. “This is a major risk factor for functional decline.”

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and director of the Acute Care for the Elderly Service of The University of Colorado Hospital in Denver, explains that his institution has addressed this issue using a dedicated order set for geriatric patients admitted anywhere in the hospital. The order set guides clinicians toward encouraging mobility.

“The order set defaults to ambulation three times a day with nursing supervision,” he says. “In fact, it does not include an option for bed rest. Therefore, a physician would have to manually enter a bed rest order, making supervised exercise the path of least resistance.”

3 Follow the Choosing Wisely guidelines set forth by the American Geriatrics Society.

Susan Parks, MD, associate professor and director, division of geriatric medicine and palliative care, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, points to the 10 recommendations developed by the American Geriatrics Society for the care of geriatric patients as an excellent reference for hospitalists treating the elderly.

“Taking care when prescribing medications for the elderly, guarding against the dangers of polypharmacy, and avoiding restraints in cases of delirium not only prevent costly overtreatment but can help maintain the patient’s level of function,” Dr. Parks says.

4 An interdisciplinary approach is most effective for geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks also advocates for team-based care, with hospitalists working collaboratively to bring multiple perspectives to treating the patient.

“The team not only works together to develop a treatment plan but leverages their diverse perspectives to align their treatment plan with the patient’s and family’s needs and individual goals for care,” she says. “This becomes increasingly important as geriatric patients approach the end of life.”

5 Guard against delirium.

Delirium is one of the most common occurrences among geriatric patients.

“While more and more frontline providers are familiar with delirium, most hospital units and the systems of care delivery are not designed to prevent delirium or treat it once it has developed,” Dr. Mattison says. “For instance, while we know the importance of proper sleep and ensuring patients are allowed uninterrupted sleep at night, we still frequently wake patients multiple times per night. Multiple clinical providers have different jobs to do during the night—the aide will wake the patient to check vital signs, the nurse will later wake the patient to dispense a necessary medication, the phlebotomist will wake the patient to draw blood.”

These practices, common in hospitals, are contributing to the prevalence of delirium among geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks warns that dementia patients are at an “especially high risk for delirium and must be observed more closely.

“Because of its transitory nature, delirium is easy for a physician to miss,” she adds. “In fact, another benefit of the team-based approach is that the more physicians [there are] who evaluate a geriatric patient, the greater the chances [are] that delirium will be caught.”

6 Beware the dangers of polypharmacy and medications that pose risks to older adults.

Polypharmacy in the elderly has been associated with significant negative consequences, including increases in healthcare costs, adverse events, and falls, and decreases in nutrition and overall functional status.3

According to Dr. Parks, polypharmacy is a major contributor to delirium; to avoid it, medication lists should be pared down when possible, and the Beers Criteria list should always be consulted when prescribing a new medication. Beyond lists, electronic medical records can provide interventions that can offer embedded medication decision support.

Dr. Mattison says her hospitalist team is fortunate, because the systems Beth Israel Deaconess has in place help improve medication safety for the elderly.

“[We] have a proprietary system that has allowed us to customize alerts and embed decision support,” she explains. “We have selected drug warnings drawn from lists of potentially inappropriate medications for elders [and] embedded decision support screens to guide ordering providers, making it easier to ensure the right drug in the right dose is ordered for the right patient at the right time.”

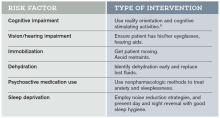

Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) Interventions

Hospital Elder Life Programs (HELP) are integrated units of care designed to prevent delirium by employing clinically proven interventions in the presence of specific delirium risk factors.5

7 Think in terms of syndromes, rather than independent causes.

“When an elderly patient presents with conditions such as post-operative delirium, incontinence, or an increased risk for falls, there are usually multiple contributing factors rather than a unique cause,” Dr. McCormick says. “Syndromatic thinking enables you to identify multiple potential factors and treat all of them, hoping that in aggregate the treatments will improve the patient’s condition.”

8 Focus care on the patient as a whole, and on individual goals for treatment.

Dr. Covinsky urges hospitalists to treat not just the disease but the whole patient.

“Guidelines might recommend treating high blood pressure aggressively, but if the medications make a patient dizzy to the point of falling and risking a hip fracture, that treatment is not best for the patient as a whole,” he says.

He points out that each elderly patient has different levels of physical and cognitive impairment as well as psychosocial needs. Will they be returning home, and if so, what activities will they need to perform? How much support from caregivers will there be?

“It is essential that physicians understand at what level a patient was functioning when they entered, what happened at the time of hospitalization, and what their functioning needs will be when they go home.” Dr. Covinsky says.

9 Mobilize community supports to help the transition from the hospital to home, nursing facility, or hospice.

A corollary to treating the whole patient is the quality of transitional care. If you understand what a patient will experience when they leave the hospital, you will be better able to smooth out those transitions. Dr. McCormick encourages hospitalists to “learn about how nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices work.

“Many hospitalists function in more than one setting,” he adds. “In addition to their practice in a hospital, they may be medical directors of nursing homes or hospices. These physicians are key agents of change who can offer guidance to hospitalists in ensuring flawless transitions between hospital and post-discharge living, which is often a predictor of successful post-hospitalization functioning.”

10 Become familiar with models of care for the elderly.

Dr. Covinsky points to the success elderly models of care have achieved in coordinating care and maintaining physical and cognitive function. ACE units, distinct areas of a hospital designed with the unique challenges of the elderly in mind, promote physical and cognitive function and help reduce the risk of delirium (see “The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Unit: Successful Geriatric Care,” below).

Despite their demonstrated success, these models are not yet the standard of care for geriatric patients in most institutions. Hospitalists have the opportunity to be catalysts for the adoption of these effective approaches to geriatric care.4,5

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Freudenheim M. Preparing more care of elderly. The New York Times. June 28, 2010. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Folz-Gray D. Most common causes of hospital admissions for older adults. AARP Bulletin. March 1, 2012. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):10.

- Inouye SK. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP): resources for implementation. American Geriatrics Society website. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Flood KL, Allen KR. ACE units improve complex patient management. Today’s Geriatric Medicine. September 2013. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- University of Rochester Medical Center. The ACE model of care. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Hung WW, Ross JS, Farber J, Siu AL. Evaluation of the Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) Service. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):990-996.

How many octogenarians do you treat in a year? Nonagenarians? Centenarians? How much have their numbers increased over the last two decades? In the wake of the fabled “silver tsunami,” more than 40% of adult inpatients are aged 65 years or older. By 2030, more than 70 million Americans will have joined the ranks of senior citizens.

Members of this group often have multiple chronic conditions that may require hospitalization as many as 10 times per year.1 Others appear in the ED after falls or suffering from cardiovascular conditions or infection.2

The Hospitalist surveyed seasoned geriatricians for their advice on treating this highly specialized and rapidly growing population, and compiled a list of 10 things these specialists believe hospitalists should know.

1 All physicians should be educated in the basics of geriatric care.

Wayne McCormick, MD, MPH, a geriatrician on the Inpatient Palliative and Supportive Care Consultation Team at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, notes that with the explosion of the aging population in the U.S., it is impossible to train enough geriatricians to care for every elderly hospital inpatient, so hospitalists need to increase their knowledge base of geriatric issues.

“To ensure that elderly patients receive good care suited to their specific needs, there need to be 10 times as many geriatrics-savvy internal medicine physicians as board-certified geriatricians,”Dr. McCormick says. “That way, elderly patients can find good primary, if not specialized, geriatric care.”

Dr. McCormick recommends the resources of the American Geriatrics Society, which includes fellowships on geriatric issues, conferences, and educational material on its website.

2 Sometimes the disease is not the most important focus—maintaining the patient’s function is.

Kenneth Covinsky, MD, MPH, division of geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco, says that, many times, geriatric patients are “admitted for pneumonia or heart failure, and, during their stay, the condition improves; however, the person who came in walking and able to perform activities of daily living on their own leaves unable to function.”

It is easy to see how hospital stays work against maintaining function in the elderly. An important part of maintaining function is encouraging mobility, but, according to Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, FACP, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University and associate chief of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, this does not happen enough.

“Most older adults spend the majority of their days in the hospital in bed, even when they are able to walk independently,” she says. “This is a major risk factor for functional decline.”

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and director of the Acute Care for the Elderly Service of The University of Colorado Hospital in Denver, explains that his institution has addressed this issue using a dedicated order set for geriatric patients admitted anywhere in the hospital. The order set guides clinicians toward encouraging mobility.

“The order set defaults to ambulation three times a day with nursing supervision,” he says. “In fact, it does not include an option for bed rest. Therefore, a physician would have to manually enter a bed rest order, making supervised exercise the path of least resistance.”

3 Follow the Choosing Wisely guidelines set forth by the American Geriatrics Society.

Susan Parks, MD, associate professor and director, division of geriatric medicine and palliative care, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, points to the 10 recommendations developed by the American Geriatrics Society for the care of geriatric patients as an excellent reference for hospitalists treating the elderly.

“Taking care when prescribing medications for the elderly, guarding against the dangers of polypharmacy, and avoiding restraints in cases of delirium not only prevent costly overtreatment but can help maintain the patient’s level of function,” Dr. Parks says.

4 An interdisciplinary approach is most effective for geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks also advocates for team-based care, with hospitalists working collaboratively to bring multiple perspectives to treating the patient.

“The team not only works together to develop a treatment plan but leverages their diverse perspectives to align their treatment plan with the patient’s and family’s needs and individual goals for care,” she says. “This becomes increasingly important as geriatric patients approach the end of life.”

5 Guard against delirium.

Delirium is one of the most common occurrences among geriatric patients.

“While more and more frontline providers are familiar with delirium, most hospital units and the systems of care delivery are not designed to prevent delirium or treat it once it has developed,” Dr. Mattison says. “For instance, while we know the importance of proper sleep and ensuring patients are allowed uninterrupted sleep at night, we still frequently wake patients multiple times per night. Multiple clinical providers have different jobs to do during the night—the aide will wake the patient to check vital signs, the nurse will later wake the patient to dispense a necessary medication, the phlebotomist will wake the patient to draw blood.”

These practices, common in hospitals, are contributing to the prevalence of delirium among geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks warns that dementia patients are at an “especially high risk for delirium and must be observed more closely.

“Because of its transitory nature, delirium is easy for a physician to miss,” she adds. “In fact, another benefit of the team-based approach is that the more physicians [there are] who evaluate a geriatric patient, the greater the chances [are] that delirium will be caught.”

6 Beware the dangers of polypharmacy and medications that pose risks to older adults.

Polypharmacy in the elderly has been associated with significant negative consequences, including increases in healthcare costs, adverse events, and falls, and decreases in nutrition and overall functional status.3

According to Dr. Parks, polypharmacy is a major contributor to delirium; to avoid it, medication lists should be pared down when possible, and the Beers Criteria list should always be consulted when prescribing a new medication. Beyond lists, electronic medical records can provide interventions that can offer embedded medication decision support.

Dr. Mattison says her hospitalist team is fortunate, because the systems Beth Israel Deaconess has in place help improve medication safety for the elderly.

“[We] have a proprietary system that has allowed us to customize alerts and embed decision support,” she explains. “We have selected drug warnings drawn from lists of potentially inappropriate medications for elders [and] embedded decision support screens to guide ordering providers, making it easier to ensure the right drug in the right dose is ordered for the right patient at the right time.”

Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) Interventions

Hospital Elder Life Programs (HELP) are integrated units of care designed to prevent delirium by employing clinically proven interventions in the presence of specific delirium risk factors.5

7 Think in terms of syndromes, rather than independent causes.

“When an elderly patient presents with conditions such as post-operative delirium, incontinence, or an increased risk for falls, there are usually multiple contributing factors rather than a unique cause,” Dr. McCormick says. “Syndromatic thinking enables you to identify multiple potential factors and treat all of them, hoping that in aggregate the treatments will improve the patient’s condition.”

8 Focus care on the patient as a whole, and on individual goals for treatment.

Dr. Covinsky urges hospitalists to treat not just the disease but the whole patient.

“Guidelines might recommend treating high blood pressure aggressively, but if the medications make a patient dizzy to the point of falling and risking a hip fracture, that treatment is not best for the patient as a whole,” he says.

He points out that each elderly patient has different levels of physical and cognitive impairment as well as psychosocial needs. Will they be returning home, and if so, what activities will they need to perform? How much support from caregivers will there be?

“It is essential that physicians understand at what level a patient was functioning when they entered, what happened at the time of hospitalization, and what their functioning needs will be when they go home.” Dr. Covinsky says.

9 Mobilize community supports to help the transition from the hospital to home, nursing facility, or hospice.

A corollary to treating the whole patient is the quality of transitional care. If you understand what a patient will experience when they leave the hospital, you will be better able to smooth out those transitions. Dr. McCormick encourages hospitalists to “learn about how nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices work.

“Many hospitalists function in more than one setting,” he adds. “In addition to their practice in a hospital, they may be medical directors of nursing homes or hospices. These physicians are key agents of change who can offer guidance to hospitalists in ensuring flawless transitions between hospital and post-discharge living, which is often a predictor of successful post-hospitalization functioning.”

10 Become familiar with models of care for the elderly.

Dr. Covinsky points to the success elderly models of care have achieved in coordinating care and maintaining physical and cognitive function. ACE units, distinct areas of a hospital designed with the unique challenges of the elderly in mind, promote physical and cognitive function and help reduce the risk of delirium (see “The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Unit: Successful Geriatric Care,” below).

Despite their demonstrated success, these models are not yet the standard of care for geriatric patients in most institutions. Hospitalists have the opportunity to be catalysts for the adoption of these effective approaches to geriatric care.4,5

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Freudenheim M. Preparing more care of elderly. The New York Times. June 28, 2010. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Folz-Gray D. Most common causes of hospital admissions for older adults. AARP Bulletin. March 1, 2012. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):10.

- Inouye SK. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP): resources for implementation. American Geriatrics Society website. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Flood KL, Allen KR. ACE units improve complex patient management. Today’s Geriatric Medicine. September 2013. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- University of Rochester Medical Center. The ACE model of care. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Hung WW, Ross JS, Farber J, Siu AL. Evaluation of the Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) Service. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):990-996.

How many octogenarians do you treat in a year? Nonagenarians? Centenarians? How much have their numbers increased over the last two decades? In the wake of the fabled “silver tsunami,” more than 40% of adult inpatients are aged 65 years or older. By 2030, more than 70 million Americans will have joined the ranks of senior citizens.

Members of this group often have multiple chronic conditions that may require hospitalization as many as 10 times per year.1 Others appear in the ED after falls or suffering from cardiovascular conditions or infection.2

The Hospitalist surveyed seasoned geriatricians for their advice on treating this highly specialized and rapidly growing population, and compiled a list of 10 things these specialists believe hospitalists should know.

1 All physicians should be educated in the basics of geriatric care.

Wayne McCormick, MD, MPH, a geriatrician on the Inpatient Palliative and Supportive Care Consultation Team at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, notes that with the explosion of the aging population in the U.S., it is impossible to train enough geriatricians to care for every elderly hospital inpatient, so hospitalists need to increase their knowledge base of geriatric issues.

“To ensure that elderly patients receive good care suited to their specific needs, there need to be 10 times as many geriatrics-savvy internal medicine physicians as board-certified geriatricians,”Dr. McCormick says. “That way, elderly patients can find good primary, if not specialized, geriatric care.”

Dr. McCormick recommends the resources of the American Geriatrics Society, which includes fellowships on geriatric issues, conferences, and educational material on its website.

2 Sometimes the disease is not the most important focus—maintaining the patient’s function is.

Kenneth Covinsky, MD, MPH, division of geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco, says that, many times, geriatric patients are “admitted for pneumonia or heart failure, and, during their stay, the condition improves; however, the person who came in walking and able to perform activities of daily living on their own leaves unable to function.”

It is easy to see how hospital stays work against maintaining function in the elderly. An important part of maintaining function is encouraging mobility, but, according to Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, FACP, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University and associate chief of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, this does not happen enough.

“Most older adults spend the majority of their days in the hospital in bed, even when they are able to walk independently,” she says. “This is a major risk factor for functional decline.”

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and director of the Acute Care for the Elderly Service of The University of Colorado Hospital in Denver, explains that his institution has addressed this issue using a dedicated order set for geriatric patients admitted anywhere in the hospital. The order set guides clinicians toward encouraging mobility.

“The order set defaults to ambulation three times a day with nursing supervision,” he says. “In fact, it does not include an option for bed rest. Therefore, a physician would have to manually enter a bed rest order, making supervised exercise the path of least resistance.”

3 Follow the Choosing Wisely guidelines set forth by the American Geriatrics Society.

Susan Parks, MD, associate professor and director, division of geriatric medicine and palliative care, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, points to the 10 recommendations developed by the American Geriatrics Society for the care of geriatric patients as an excellent reference for hospitalists treating the elderly.

“Taking care when prescribing medications for the elderly, guarding against the dangers of polypharmacy, and avoiding restraints in cases of delirium not only prevent costly overtreatment but can help maintain the patient’s level of function,” Dr. Parks says.

4 An interdisciplinary approach is most effective for geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks also advocates for team-based care, with hospitalists working collaboratively to bring multiple perspectives to treating the patient.

“The team not only works together to develop a treatment plan but leverages their diverse perspectives to align their treatment plan with the patient’s and family’s needs and individual goals for care,” she says. “This becomes increasingly important as geriatric patients approach the end of life.”

5 Guard against delirium.

Delirium is one of the most common occurrences among geriatric patients.

“While more and more frontline providers are familiar with delirium, most hospital units and the systems of care delivery are not designed to prevent delirium or treat it once it has developed,” Dr. Mattison says. “For instance, while we know the importance of proper sleep and ensuring patients are allowed uninterrupted sleep at night, we still frequently wake patients multiple times per night. Multiple clinical providers have different jobs to do during the night—the aide will wake the patient to check vital signs, the nurse will later wake the patient to dispense a necessary medication, the phlebotomist will wake the patient to draw blood.”

These practices, common in hospitals, are contributing to the prevalence of delirium among geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks warns that dementia patients are at an “especially high risk for delirium and must be observed more closely.

“Because of its transitory nature, delirium is easy for a physician to miss,” she adds. “In fact, another benefit of the team-based approach is that the more physicians [there are] who evaluate a geriatric patient, the greater the chances [are] that delirium will be caught.”

6 Beware the dangers of polypharmacy and medications that pose risks to older adults.

Polypharmacy in the elderly has been associated with significant negative consequences, including increases in healthcare costs, adverse events, and falls, and decreases in nutrition and overall functional status.3

According to Dr. Parks, polypharmacy is a major contributor to delirium; to avoid it, medication lists should be pared down when possible, and the Beers Criteria list should always be consulted when prescribing a new medication. Beyond lists, electronic medical records can provide interventions that can offer embedded medication decision support.

Dr. Mattison says her hospitalist team is fortunate, because the systems Beth Israel Deaconess has in place help improve medication safety for the elderly.

“[We] have a proprietary system that has allowed us to customize alerts and embed decision support,” she explains. “We have selected drug warnings drawn from lists of potentially inappropriate medications for elders [and] embedded decision support screens to guide ordering providers, making it easier to ensure the right drug in the right dose is ordered for the right patient at the right time.”

Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) Interventions

Hospital Elder Life Programs (HELP) are integrated units of care designed to prevent delirium by employing clinically proven interventions in the presence of specific delirium risk factors.5

7 Think in terms of syndromes, rather than independent causes.

“When an elderly patient presents with conditions such as post-operative delirium, incontinence, or an increased risk for falls, there are usually multiple contributing factors rather than a unique cause,” Dr. McCormick says. “Syndromatic thinking enables you to identify multiple potential factors and treat all of them, hoping that in aggregate the treatments will improve the patient’s condition.”

8 Focus care on the patient as a whole, and on individual goals for treatment.

Dr. Covinsky urges hospitalists to treat not just the disease but the whole patient.

“Guidelines might recommend treating high blood pressure aggressively, but if the medications make a patient dizzy to the point of falling and risking a hip fracture, that treatment is not best for the patient as a whole,” he says.

He points out that each elderly patient has different levels of physical and cognitive impairment as well as psychosocial needs. Will they be returning home, and if so, what activities will they need to perform? How much support from caregivers will there be?

“It is essential that physicians understand at what level a patient was functioning when they entered, what happened at the time of hospitalization, and what their functioning needs will be when they go home.” Dr. Covinsky says.

9 Mobilize community supports to help the transition from the hospital to home, nursing facility, or hospice.

A corollary to treating the whole patient is the quality of transitional care. If you understand what a patient will experience when they leave the hospital, you will be better able to smooth out those transitions. Dr. McCormick encourages hospitalists to “learn about how nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospices work.

“Many hospitalists function in more than one setting,” he adds. “In addition to their practice in a hospital, they may be medical directors of nursing homes or hospices. These physicians are key agents of change who can offer guidance to hospitalists in ensuring flawless transitions between hospital and post-discharge living, which is often a predictor of successful post-hospitalization functioning.”

10 Become familiar with models of care for the elderly.

Dr. Covinsky points to the success elderly models of care have achieved in coordinating care and maintaining physical and cognitive function. ACE units, distinct areas of a hospital designed with the unique challenges of the elderly in mind, promote physical and cognitive function and help reduce the risk of delirium (see “The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Unit: Successful Geriatric Care,” below).

Despite their demonstrated success, these models are not yet the standard of care for geriatric patients in most institutions. Hospitalists have the opportunity to be catalysts for the adoption of these effective approaches to geriatric care.4,5

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Freudenheim M. Preparing more care of elderly. The New York Times. June 28, 2010. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Folz-Gray D. Most common causes of hospital admissions for older adults. AARP Bulletin. March 1, 2012. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Maher RL, Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):10.

- Inouye SK. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP): resources for implementation. American Geriatrics Society website. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Flood KL, Allen KR. ACE units improve complex patient management. Today’s Geriatric Medicine. September 2013. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- University of Rochester Medical Center. The ACE model of care. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- Hung WW, Ross JS, Farber J, Siu AL. Evaluation of the Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) Service. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):990-996.

Hospitalists Support Medicare’s Plan to Reimburse Advance Care Planning

On July 8, following on the heels of the sustainable growth rate repeal, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released a proposed update to the 2016 Physician Fee Schedule that would reimburse physicians and other qualified providers for conversations with patients and patient families about end-of-life care.

It is yet another move toward higher quality patient-centered care, CMS said in a news release on its website the day the proposed rule change was published. The comment period, which spanned 90 days, closes Nov. 1. The final rule will take effect Jan. 1, 2016.

Although CMS specifically cites the recommendation made by the American Medical Association to make advance care planning a separate, payable service, many physician groups, including the Society of Hospital Medicine, have championed and continue to actively advocate for reimbursement for end-of-life conversations with patients and their families.

“We think that palliative care and hospice services are underutilized, so we support anything we can do to make sure there is more appropriate use of these services,” says Ronald A. Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, a founding member of SHM, a longtime SHM Public Policy Committee member, and a current member of its board of directors. “We think it’s important to encourage providers to take the time to have those discussions, and one way is getting reimbursement for that time.”

When CMS considered reimbursement for advance care planning last year but did not propose a rule, SHM wrote a letter in December 2014 to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) acting administrator Marilynn Tavenner urging the agency to consider adopting the two codes for complex advance care planning developed by the AMA’s CPT Editorial Panel.1 In May 2015, SHM joined 65 other medical specialty and professional societies in signing a letter to HHS Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell asking for these codes to be formalized in CY 2016.2

In the more recent letter, the authors mention peer-reviewed research demonstrating that advance care planning leads to “better care, higher patient and family satisfaction, fewer unwanted hospitalizations and lower rates of caregiver distress, depression and lost productivity.” SHM also cites a 2014 Institute of Medicine report, Dying in America, in which advance care planning is listed as one of five key recommendations.3

—Dr. Greeno

Pending final rule adoption, the codes 99487 and 99498 will become payable starting in January 2016.

“We (hospitalists) are in this position pretty much every day, working with people in late life and at the end of life, cycling in and out of the hospital with end-stage chronic diseases,” says Howard Epstein, MD, FHM, CHIE, executive vice president and chief medical officer at PreferredOne Health Plans in Minnesota and a hospice and palliative medicine-certified hospitalist. “I’ll be quite honest: I don’t think reimbursement is going to pay for the time and expertise for these procedures; it’s more offsetting the costs of doing the right thing for patients and families.”

What reimbursement does is lend credibility to the goals of care and advance care planning discussions patients and providers are already having, Dr. Epstein says.

“Having a specific CPT code for this legitimizes it,” he says, “like the field of palliative medicine when it became a board-certified specialty; these kinds of things really matter. They say, ‘This is our procedure.’”

It also enables providers to take the time to have these conversations with patients and families. In a post on the SHM blog in July 2015, Dr. Epstein, also a member of the SHM board of directors, cites a New England Journal of Medicine study indicating that most of the 2.5 million deaths each year in the U.S. are due to progressive health conditions and another that found that a quarter of elderly Americans lack the ability to make critical decisions at the end of life.4,5 The proposed rule, he says, reflects a change in our culture.

“As our society ages, and more and more people go through the experience with loved ones, they are demanding this care,” Dr. Epstein says.

But simply providing reimbursement is not enough, nor should the onus fall squarely on physicians, Dr. Epstein says. Rather, he believes physicians should take advantage of resources provided by SHM, hospital systems, and other organizations that offer training in advance care planning, and all members of a patient care and support team should be well versed in how to have these conversations.

The rule comes just over five years after attempts to include advance care planning in health reform efforts failed, and SHM plans to continue to advocate for national consistency in applying the measure and to work to ensure there are no limits to the timing of advance care planning conversations or where they take place.

“It was just a matter of time. It was bound to happen,” Dr. Greeno says of the rule. “We held out during the discussions of death panels and things like that. There are always lots of political issues with misinformation on both sides. We’ve tried to really communicate how and why we are supportive, and the benefits for our patients and our healthcare system, which is always our goal.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Kealey BT. Re: Medicare Program; Revisions to Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule, Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule, Access to Identifiable Data for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation Models and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2015; Final Rule (CMS-1612-FC). Letter to Administrator Marilyn Tavenner, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services. December 8, 2014. Accessed September 14, 2015.

- Letter to The Honorable Sylvia Mathews Burwell, Secretary of Health and Human Services. May 12, 2015. Accessed September 14, 2015.

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. September 17, 2014. Accessed September 14, 2015.

- Wolf SM, Berlinger N, Jennings B. Forty years of work on end-of-life care - from patient’s rights to systemic reform. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):678-682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1410321.

- Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211-1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901.

On July 8, following on the heels of the sustainable growth rate repeal, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released a proposed update to the 2016 Physician Fee Schedule that would reimburse physicians and other qualified providers for conversations with patients and patient families about end-of-life care.

It is yet another move toward higher quality patient-centered care, CMS said in a news release on its website the day the proposed rule change was published. The comment period, which spanned 90 days, closes Nov. 1. The final rule will take effect Jan. 1, 2016.

Although CMS specifically cites the recommendation made by the American Medical Association to make advance care planning a separate, payable service, many physician groups, including the Society of Hospital Medicine, have championed and continue to actively advocate for reimbursement for end-of-life conversations with patients and their families.

“We think that palliative care and hospice services are underutilized, so we support anything we can do to make sure there is more appropriate use of these services,” says Ronald A. Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, a founding member of SHM, a longtime SHM Public Policy Committee member, and a current member of its board of directors. “We think it’s important to encourage providers to take the time to have those discussions, and one way is getting reimbursement for that time.”

When CMS considered reimbursement for advance care planning last year but did not propose a rule, SHM wrote a letter in December 2014 to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) acting administrator Marilynn Tavenner urging the agency to consider adopting the two codes for complex advance care planning developed by the AMA’s CPT Editorial Panel.1 In May 2015, SHM joined 65 other medical specialty and professional societies in signing a letter to HHS Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell asking for these codes to be formalized in CY 2016.2

In the more recent letter, the authors mention peer-reviewed research demonstrating that advance care planning leads to “better care, higher patient and family satisfaction, fewer unwanted hospitalizations and lower rates of caregiver distress, depression and lost productivity.” SHM also cites a 2014 Institute of Medicine report, Dying in America, in which advance care planning is listed as one of five key recommendations.3

—Dr. Greeno

Pending final rule adoption, the codes 99487 and 99498 will become payable starting in January 2016.