User login

Clinical Segment 6: Don’t back away from reality of patients with serious mental illness

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

People in this video: Whitney McKnight, cohost and producer of Mental Health Consult; Dr. Lorenzo Norris, editorial board member of Clinical Psychiatry News and cohost of Mental Health Consult, and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, assistant dean of student affairs, and the medical director of psychiatric and behavioral services at George Washington University Hospital, Washington; Dr. Lillian Beard, pediatrician with Children’s National Hospital Network, Washington, and a Pediatric News editorial board member; Dr. David Pickar, adjunct professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

Dr. Pickar: Psychosis is the hallmark of serious mental illness, whether it's schizophrenia, severe bipolar, or psychosis otherwise. It is one of the great tragedies of our medical system, and I'll come back to the primary doc who's out there. I want to talk to you about this. It is a tragedy. Whitney knows, I put together a little documentary, The Realities of Serious Mental Illness. I just couldn't stand the lack of information.

They're very quick to report the violence, and I know a lot about the violence. I worry about it all the time. There's a huge debate between civil liberties and safety that's going on in serious mental illness. Regardless, knowing about it is enormously important for all docs. More patients with serious mental illness, by far, are in jails than they are in mental hospitals. There is nothing for them. You talk about collaborative care.

Whitney: On the team in the primary care setting, who's treating what?

Dr. Pickar: I'm talking now myself. A family member brings in an 18-year-old to evaluate. Okay? I'm glad to see it. Of course, I've been around a while. I spent decades as a scientist in schizophrenia. I just close my eyes and hope that I'm not seeing a first break for a seriously mental ill patient. Not that we can't treat it. Not that we can't help, but I know what's entailed. Not unlike seeing an oncology presentation. We're there. We're docs. You don't give up on it, but you know what's ahead for that family.

What's fascinating is many of the first breaks occur, not necessarily quietly, but can be a little insidious. They can be brought to the primary care. It is not uncommon. “My 16-year-old's not doing well. I can't get him up.” But really, what's going on? The primary care doc needs to have a consciousness of that. Let me just say this: First things about serious mental illness, particularly in schizophrenia, 1% of the population has it. That makes it a very common disorder.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

People in this video: Whitney McKnight, cohost and producer of Mental Health Consult; Dr. Lorenzo Norris, editorial board member of Clinical Psychiatry News and cohost of Mental Health Consult, and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, assistant dean of student affairs, and the medical director of psychiatric and behavioral services at George Washington University Hospital, Washington; Dr. Lillian Beard, pediatrician with Children’s National Hospital Network, Washington, and a Pediatric News editorial board member; Dr. David Pickar, adjunct professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

Dr. Pickar: Psychosis is the hallmark of serious mental illness, whether it's schizophrenia, severe bipolar, or psychosis otherwise. It is one of the great tragedies of our medical system, and I'll come back to the primary doc who's out there. I want to talk to you about this. It is a tragedy. Whitney knows, I put together a little documentary, The Realities of Serious Mental Illness. I just couldn't stand the lack of information.

They're very quick to report the violence, and I know a lot about the violence. I worry about it all the time. There's a huge debate between civil liberties and safety that's going on in serious mental illness. Regardless, knowing about it is enormously important for all docs. More patients with serious mental illness, by far, are in jails than they are in mental hospitals. There is nothing for them. You talk about collaborative care.

Whitney: On the team in the primary care setting, who's treating what?

Dr. Pickar: I'm talking now myself. A family member brings in an 18-year-old to evaluate. Okay? I'm glad to see it. Of course, I've been around a while. I spent decades as a scientist in schizophrenia. I just close my eyes and hope that I'm not seeing a first break for a seriously mental ill patient. Not that we can't treat it. Not that we can't help, but I know what's entailed. Not unlike seeing an oncology presentation. We're there. We're docs. You don't give up on it, but you know what's ahead for that family.

What's fascinating is many of the first breaks occur, not necessarily quietly, but can be a little insidious. They can be brought to the primary care. It is not uncommon. “My 16-year-old's not doing well. I can't get him up.” But really, what's going on? The primary care doc needs to have a consciousness of that. Let me just say this: First things about serious mental illness, particularly in schizophrenia, 1% of the population has it. That makes it a very common disorder.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

People in this video: Whitney McKnight, cohost and producer of Mental Health Consult; Dr. Lorenzo Norris, editorial board member of Clinical Psychiatry News and cohost of Mental Health Consult, and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, assistant dean of student affairs, and the medical director of psychiatric and behavioral services at George Washington University Hospital, Washington; Dr. Lillian Beard, pediatrician with Children’s National Hospital Network, Washington, and a Pediatric News editorial board member; Dr. David Pickar, adjunct professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

Dr. Pickar: Psychosis is the hallmark of serious mental illness, whether it's schizophrenia, severe bipolar, or psychosis otherwise. It is one of the great tragedies of our medical system, and I'll come back to the primary doc who's out there. I want to talk to you about this. It is a tragedy. Whitney knows, I put together a little documentary, The Realities of Serious Mental Illness. I just couldn't stand the lack of information.

They're very quick to report the violence, and I know a lot about the violence. I worry about it all the time. There's a huge debate between civil liberties and safety that's going on in serious mental illness. Regardless, knowing about it is enormously important for all docs. More patients with serious mental illness, by far, are in jails than they are in mental hospitals. There is nothing for them. You talk about collaborative care.

Whitney: On the team in the primary care setting, who's treating what?

Dr. Pickar: I'm talking now myself. A family member brings in an 18-year-old to evaluate. Okay? I'm glad to see it. Of course, I've been around a while. I spent decades as a scientist in schizophrenia. I just close my eyes and hope that I'm not seeing a first break for a seriously mental ill patient. Not that we can't treat it. Not that we can't help, but I know what's entailed. Not unlike seeing an oncology presentation. We're there. We're docs. You don't give up on it, but you know what's ahead for that family.

What's fascinating is many of the first breaks occur, not necessarily quietly, but can be a little insidious. They can be brought to the primary care. It is not uncommon. “My 16-year-old's not doing well. I can't get him up.” But really, what's going on? The primary care doc needs to have a consciousness of that. Let me just say this: First things about serious mental illness, particularly in schizophrenia, 1% of the population has it. That makes it a very common disorder.

PROMIS physical function domain outperforms in cervical spine patients

SAN DIEGO – The Neck Disability Index–10 did not perform as well as the Neck Disability Index–5 in assessing patient-reported outcomes in cervical spine patients – and neither was as good as the PROMIS physical function domain delivered by computerized adaptive testing.

Those are the key findings from an analysis of data from more than 500 cervical spine patients treated at University of Utah Health Care in Salt Lake City.

“Previous studies by us and others have shown problems with the NDI [Neck Disability Index] as it is commonly administered” in 10 questions, lead study author Dr. Darrel S. Brodke said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the Cervical Spine Research Society. “It has a very poor floor effect, meaning that it does not differentiate between minimally disabled patients, and the scores cannot be appropriately handled with the kinds of statistics that we normally use – though because few of us know this, we still use it as a standard parametric measure.”

In what he said is the first study of its kind, Dr. Brodke, professor of orthopedics at the University of Utah, and his associates set out to compare the psychometric performance of the National Institutes of Health–funded PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) physical function (PF) domain, administered by computerized adaptive testing, with the standard NDI-10, the NDI-5, and the 36-Item Short Form physical function domain (SF-36 PFD).

In all, 566 patients completed the NDI and PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing assessments, while 490 also completed the SF-36 PFD.

On average, the NDI-10 took the longest to complete (10 questions in a mean of 183 seconds), followed by the SF-36 PFD (5 questions in a mean of 123 seconds), the NDI-5 (5 questions in a mean of 99 seconds), and the PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing (between 4 and 12 questions in a mean of 62 seconds).

The psychometric properties of the PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing were superior to the other outcome measurement tools studied, Dr. Brodke reported. Specifically, the ceiling and floor effects were “excellent” for the PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing (1.94% and 4.06%, respectively), while the ceiling effects were “fine” for the NDI-10 (4.77%), NDI-5 (7.60%), and SF-36 PFD (11.84%), he said.

However, the floor effects of these three instruments were poor (45.58%, 48.59% and 21.55%, respectively). “The NDI-10 also has the additional challenge of extremely poor raw score to measure correlation,” the researchers noted in their abstract.

“The legacy scale scores significantly predicted the PROMIS PF CAT scores (P less than .0001), with fair correlation for the PF CAT and NDI-10 (0.53) and good correlation of PF CAT and SF-36 PFD (0.62), allowing use of conversion equations to predict scores, which were generated,” the investigators explained.

PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing “does much better than the NDI or the SF-36 physical function domain at characterizing patients’ physical function, with much better coverage,” Dr. Brodke said. “Not only this, but it is also much faster to fill out, so less burdensome to the patient and the clinic.”

One limitation of the study is that the researchers did not measure the responsiveness aspect of PROMIS performance. “We did not have enough pre- and posttreatment scores to do this measurement yet,” Dr. Brodke said. “The other thing is that minimum clinically important difference [MCID] is not yet worked out for PROMIS in this patient population, though we can infer an MCID as one-half of a standard deviation. More to come in future studies.”

Dr. Brodke reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The Neck Disability Index–10 did not perform as well as the Neck Disability Index–5 in assessing patient-reported outcomes in cervical spine patients – and neither was as good as the PROMIS physical function domain delivered by computerized adaptive testing.

Those are the key findings from an analysis of data from more than 500 cervical spine patients treated at University of Utah Health Care in Salt Lake City.

“Previous studies by us and others have shown problems with the NDI [Neck Disability Index] as it is commonly administered” in 10 questions, lead study author Dr. Darrel S. Brodke said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the Cervical Spine Research Society. “It has a very poor floor effect, meaning that it does not differentiate between minimally disabled patients, and the scores cannot be appropriately handled with the kinds of statistics that we normally use – though because few of us know this, we still use it as a standard parametric measure.”

In what he said is the first study of its kind, Dr. Brodke, professor of orthopedics at the University of Utah, and his associates set out to compare the psychometric performance of the National Institutes of Health–funded PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) physical function (PF) domain, administered by computerized adaptive testing, with the standard NDI-10, the NDI-5, and the 36-Item Short Form physical function domain (SF-36 PFD).

In all, 566 patients completed the NDI and PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing assessments, while 490 also completed the SF-36 PFD.

On average, the NDI-10 took the longest to complete (10 questions in a mean of 183 seconds), followed by the SF-36 PFD (5 questions in a mean of 123 seconds), the NDI-5 (5 questions in a mean of 99 seconds), and the PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing (between 4 and 12 questions in a mean of 62 seconds).

The psychometric properties of the PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing were superior to the other outcome measurement tools studied, Dr. Brodke reported. Specifically, the ceiling and floor effects were “excellent” for the PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing (1.94% and 4.06%, respectively), while the ceiling effects were “fine” for the NDI-10 (4.77%), NDI-5 (7.60%), and SF-36 PFD (11.84%), he said.

However, the floor effects of these three instruments were poor (45.58%, 48.59% and 21.55%, respectively). “The NDI-10 also has the additional challenge of extremely poor raw score to measure correlation,” the researchers noted in their abstract.

“The legacy scale scores significantly predicted the PROMIS PF CAT scores (P less than .0001), with fair correlation for the PF CAT and NDI-10 (0.53) and good correlation of PF CAT and SF-36 PFD (0.62), allowing use of conversion equations to predict scores, which were generated,” the investigators explained.

PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing “does much better than the NDI or the SF-36 physical function domain at characterizing patients’ physical function, with much better coverage,” Dr. Brodke said. “Not only this, but it is also much faster to fill out, so less burdensome to the patient and the clinic.”

One limitation of the study is that the researchers did not measure the responsiveness aspect of PROMIS performance. “We did not have enough pre- and posttreatment scores to do this measurement yet,” Dr. Brodke said. “The other thing is that minimum clinically important difference [MCID] is not yet worked out for PROMIS in this patient population, though we can infer an MCID as one-half of a standard deviation. More to come in future studies.”

Dr. Brodke reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The Neck Disability Index–10 did not perform as well as the Neck Disability Index–5 in assessing patient-reported outcomes in cervical spine patients – and neither was as good as the PROMIS physical function domain delivered by computerized adaptive testing.

Those are the key findings from an analysis of data from more than 500 cervical spine patients treated at University of Utah Health Care in Salt Lake City.

“Previous studies by us and others have shown problems with the NDI [Neck Disability Index] as it is commonly administered” in 10 questions, lead study author Dr. Darrel S. Brodke said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the Cervical Spine Research Society. “It has a very poor floor effect, meaning that it does not differentiate between minimally disabled patients, and the scores cannot be appropriately handled with the kinds of statistics that we normally use – though because few of us know this, we still use it as a standard parametric measure.”

In what he said is the first study of its kind, Dr. Brodke, professor of orthopedics at the University of Utah, and his associates set out to compare the psychometric performance of the National Institutes of Health–funded PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) physical function (PF) domain, administered by computerized adaptive testing, with the standard NDI-10, the NDI-5, and the 36-Item Short Form physical function domain (SF-36 PFD).

In all, 566 patients completed the NDI and PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing assessments, while 490 also completed the SF-36 PFD.

On average, the NDI-10 took the longest to complete (10 questions in a mean of 183 seconds), followed by the SF-36 PFD (5 questions in a mean of 123 seconds), the NDI-5 (5 questions in a mean of 99 seconds), and the PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing (between 4 and 12 questions in a mean of 62 seconds).

The psychometric properties of the PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing were superior to the other outcome measurement tools studied, Dr. Brodke reported. Specifically, the ceiling and floor effects were “excellent” for the PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing (1.94% and 4.06%, respectively), while the ceiling effects were “fine” for the NDI-10 (4.77%), NDI-5 (7.60%), and SF-36 PFD (11.84%), he said.

However, the floor effects of these three instruments were poor (45.58%, 48.59% and 21.55%, respectively). “The NDI-10 also has the additional challenge of extremely poor raw score to measure correlation,” the researchers noted in their abstract.

“The legacy scale scores significantly predicted the PROMIS PF CAT scores (P less than .0001), with fair correlation for the PF CAT and NDI-10 (0.53) and good correlation of PF CAT and SF-36 PFD (0.62), allowing use of conversion equations to predict scores, which were generated,” the investigators explained.

PROMIS PF computerized adaptive testing “does much better than the NDI or the SF-36 physical function domain at characterizing patients’ physical function, with much better coverage,” Dr. Brodke said. “Not only this, but it is also much faster to fill out, so less burdensome to the patient and the clinic.”

One limitation of the study is that the researchers did not measure the responsiveness aspect of PROMIS performance. “We did not have enough pre- and posttreatment scores to do this measurement yet,” Dr. Brodke said. “The other thing is that minimum clinically important difference [MCID] is not yet worked out for PROMIS in this patient population, though we can infer an MCID as one-half of a standard deviation. More to come in future studies.”

Dr. Brodke reported having no financial disclosures.

AT CSRS 2015

Key clinical point: In the elective cervical spine surgery population, the PROMIS physical function domain as delivered by computerized adaptive testing outperforms other commonly used tools to measure patient-reported outcomes.

Major finding: The ceiling and floor effects were “excellent” for the PROMIS PF (1.94% and 4.06%, respectively), while the ceiling effects were “fine” for the Neck Disability Index–10 (4.77%), the Neck Disability Index–5 (7.60%), and the 36-Item Short Form physical function domain (11.84%). However, the floor effects of these three instruments were poor (45.58%, 48.59%, and 21.55%, respectively).

Data source: A study of the psychometric performance of the PROMIS physical function domain, administered by computerized adaptive testing, comparing the standard NDI-10, NDI-5, and SF-36 physical function domain.

Disclosures: Dr. Brodke reported having no financial disclosures.

Practicality rules my medical literature–reading strategy

Keeping up on medical literature is never easy. Time is limited between work and family. It’s often hard to know what to read. Most journals are a combination of research and practical information.

I’m not an academic and never will be. I have nothing against my colleagues who are, but it’s just not my personality type. I’m a happy-to-see-patients-all-day type of doctor.

I try to stick with reading things that have an immediate impact on how I practice: review articles, information about new diagnostic procedures and treatments, and news about the economics of medicine. That’s about it. If I can’t use it now or in the immediate future, it’s not relevant to my practice. My patients want to know what I can do for them today, not in 5-10 years. There’s enough to keep up on that’s relevant to current practice as it is.

Research in medicine is obviously crucial, since what we do is based on it. There is a lot of interesting and potentially game-changing research out there. But medical literature is full of small studies that show promise for something only to be shot down when larger investigations are done. It’s not practical or even good medicine to make treatment decisions based on small-scale preliminary data and anecdotal reports.

Even the oft-cited “green journal” – Neurology – isn’t on my reading list. I admit that it has its share of practical knowledge, but the last time I read it, the majority of pages were devoted to research that was promising, though not imminently applicable to patient care. That’s not for me.

Time is always at a premium in modern life. There’s no shortage of journals and interesting research to peruse, and so I try to stay with what’s practical for both me and my patients. I’ll leave the research to those who are good at it, and do my best to support the people who come to my office every day.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Keeping up on medical literature is never easy. Time is limited between work and family. It’s often hard to know what to read. Most journals are a combination of research and practical information.

I’m not an academic and never will be. I have nothing against my colleagues who are, but it’s just not my personality type. I’m a happy-to-see-patients-all-day type of doctor.

I try to stick with reading things that have an immediate impact on how I practice: review articles, information about new diagnostic procedures and treatments, and news about the economics of medicine. That’s about it. If I can’t use it now or in the immediate future, it’s not relevant to my practice. My patients want to know what I can do for them today, not in 5-10 years. There’s enough to keep up on that’s relevant to current practice as it is.

Research in medicine is obviously crucial, since what we do is based on it. There is a lot of interesting and potentially game-changing research out there. But medical literature is full of small studies that show promise for something only to be shot down when larger investigations are done. It’s not practical or even good medicine to make treatment decisions based on small-scale preliminary data and anecdotal reports.

Even the oft-cited “green journal” – Neurology – isn’t on my reading list. I admit that it has its share of practical knowledge, but the last time I read it, the majority of pages were devoted to research that was promising, though not imminently applicable to patient care. That’s not for me.

Time is always at a premium in modern life. There’s no shortage of journals and interesting research to peruse, and so I try to stay with what’s practical for both me and my patients. I’ll leave the research to those who are good at it, and do my best to support the people who come to my office every day.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Keeping up on medical literature is never easy. Time is limited between work and family. It’s often hard to know what to read. Most journals are a combination of research and practical information.

I’m not an academic and never will be. I have nothing against my colleagues who are, but it’s just not my personality type. I’m a happy-to-see-patients-all-day type of doctor.

I try to stick with reading things that have an immediate impact on how I practice: review articles, information about new diagnostic procedures and treatments, and news about the economics of medicine. That’s about it. If I can’t use it now or in the immediate future, it’s not relevant to my practice. My patients want to know what I can do for them today, not in 5-10 years. There’s enough to keep up on that’s relevant to current practice as it is.

Research in medicine is obviously crucial, since what we do is based on it. There is a lot of interesting and potentially game-changing research out there. But medical literature is full of small studies that show promise for something only to be shot down when larger investigations are done. It’s not practical or even good medicine to make treatment decisions based on small-scale preliminary data and anecdotal reports.

Even the oft-cited “green journal” – Neurology – isn’t on my reading list. I admit that it has its share of practical knowledge, but the last time I read it, the majority of pages were devoted to research that was promising, though not imminently applicable to patient care. That’s not for me.

Time is always at a premium in modern life. There’s no shortage of journals and interesting research to peruse, and so I try to stay with what’s practical for both me and my patients. I’ll leave the research to those who are good at it, and do my best to support the people who come to my office every day.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Help save a life through GI research

An appeal from Martin Brotman, M.D., AGAF, Chair, AGA Research Foundation

Past Senior Vice President, Education, Research, and Philanthropy, CPMC Sutter Health

This holiday season is a good time to reflect on our many blessings and thank those who have helped make our lives and careers worthwhile, successful, and prosperous. What better way than to pass on something to those who will ensure that gastroenterology will advance in decades to come?

Progress in this lifesaving work is made possible by the generosity of many supporters, like you, who understand the devastating physical, emotional, and financial costs of digestive diseases. We simply cannot allow a slowdown in the pace of GI research, and we cannot afford to lose talent when research offers so much promise for the future.

What can you do to ensure the progress continues?

Show your support and give back.

Help close the gap in research funding and save lives. Make your tax-deductible donation online at www.gastro.org/donateonline.

The foundation funds promising young investigators who might not receive funding otherwise at crucial times in their early careers. The research of these individuals, while important to the field, if left unfunded, could end prematurely. That’s something the field can’t afford, and that’s why I’ve supported the AGA Research Foundation over the years through my donations. We must maintain a robust pipeline of research that will help safeguard the success of clinical medicine. I urge you to support the future of GI with a generous donation to the AGA Research Foundation endowment fund. Your donation of $250, $500, $1,000, $2,500, or any amount you can give today will keep giving for years to come.

May 2016 will mark the end of my tenure as chair of the AGA Research Foundation. I am proud of our accomplishments over these past years, and, while I will no longer occupy the chair at the head of the table, I will continue to be involved in the foundation’s important work. I am hoping that my last year at the helm of the foundation will be our most successful yet. A gift from you will be a vote of confidence in our work and will send a message that you share in our hopes for the future of digestive disease research.

Thank you in advance for support and best wishes for a happy, healthy holiday season and prosperous New Year.

Three easy ways to give

Online: www.gastro.org/contribute

Through the mail:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Over the phone: 301-222-4002

All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of U.S. law.

An appeal from Martin Brotman, M.D., AGAF, Chair, AGA Research Foundation

Past Senior Vice President, Education, Research, and Philanthropy, CPMC Sutter Health

This holiday season is a good time to reflect on our many blessings and thank those who have helped make our lives and careers worthwhile, successful, and prosperous. What better way than to pass on something to those who will ensure that gastroenterology will advance in decades to come?

Progress in this lifesaving work is made possible by the generosity of many supporters, like you, who understand the devastating physical, emotional, and financial costs of digestive diseases. We simply cannot allow a slowdown in the pace of GI research, and we cannot afford to lose talent when research offers so much promise for the future.

What can you do to ensure the progress continues?

Show your support and give back.

Help close the gap in research funding and save lives. Make your tax-deductible donation online at www.gastro.org/donateonline.

The foundation funds promising young investigators who might not receive funding otherwise at crucial times in their early careers. The research of these individuals, while important to the field, if left unfunded, could end prematurely. That’s something the field can’t afford, and that’s why I’ve supported the AGA Research Foundation over the years through my donations. We must maintain a robust pipeline of research that will help safeguard the success of clinical medicine. I urge you to support the future of GI with a generous donation to the AGA Research Foundation endowment fund. Your donation of $250, $500, $1,000, $2,500, or any amount you can give today will keep giving for years to come.

May 2016 will mark the end of my tenure as chair of the AGA Research Foundation. I am proud of our accomplishments over these past years, and, while I will no longer occupy the chair at the head of the table, I will continue to be involved in the foundation’s important work. I am hoping that my last year at the helm of the foundation will be our most successful yet. A gift from you will be a vote of confidence in our work and will send a message that you share in our hopes for the future of digestive disease research.

Thank you in advance for support and best wishes for a happy, healthy holiday season and prosperous New Year.

Three easy ways to give

Online: www.gastro.org/contribute

Through the mail:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Over the phone: 301-222-4002

All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of U.S. law.

An appeal from Martin Brotman, M.D., AGAF, Chair, AGA Research Foundation

Past Senior Vice President, Education, Research, and Philanthropy, CPMC Sutter Health

This holiday season is a good time to reflect on our many blessings and thank those who have helped make our lives and careers worthwhile, successful, and prosperous. What better way than to pass on something to those who will ensure that gastroenterology will advance in decades to come?

Progress in this lifesaving work is made possible by the generosity of many supporters, like you, who understand the devastating physical, emotional, and financial costs of digestive diseases. We simply cannot allow a slowdown in the pace of GI research, and we cannot afford to lose talent when research offers so much promise for the future.

What can you do to ensure the progress continues?

Show your support and give back.

Help close the gap in research funding and save lives. Make your tax-deductible donation online at www.gastro.org/donateonline.

The foundation funds promising young investigators who might not receive funding otherwise at crucial times in their early careers. The research of these individuals, while important to the field, if left unfunded, could end prematurely. That’s something the field can’t afford, and that’s why I’ve supported the AGA Research Foundation over the years through my donations. We must maintain a robust pipeline of research that will help safeguard the success of clinical medicine. I urge you to support the future of GI with a generous donation to the AGA Research Foundation endowment fund. Your donation of $250, $500, $1,000, $2,500, or any amount you can give today will keep giving for years to come.

May 2016 will mark the end of my tenure as chair of the AGA Research Foundation. I am proud of our accomplishments over these past years, and, while I will no longer occupy the chair at the head of the table, I will continue to be involved in the foundation’s important work. I am hoping that my last year at the helm of the foundation will be our most successful yet. A gift from you will be a vote of confidence in our work and will send a message that you share in our hopes for the future of digestive disease research.

Thank you in advance for support and best wishes for a happy, healthy holiday season and prosperous New Year.

Three easy ways to give

Online: www.gastro.org/contribute

Through the mail:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Over the phone: 301-222-4002

All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of U.S. law.

Purpura Fulminans in the Setting of Escherichia coli Septicemia

To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans is a severe and rapidly fatal thrombotic disorder that can occur in association with either hereditary or acquired deficiencies of the natural anticoagulants protein C and protein S.1 It most commonly results from the acute inflammatory response and subsequent disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) seen in severe bacterial septicemia. Excessive bleeding, retiform purpura, and skin necrosis may develop as a result of the coagulopathies of typical DIC.1Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus frequently are implicated as pathogens, but Escherichia coli–associated purpura fulminans in adults is rare.2,3 We report a case of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of end-stage liver disease secondary to alcoholic liver cirrhosis diagnosed 13 years prior complicated by ascites and esophageal varices presented to a primary care clinic for evaluation of a recent-onset nontender lesion on the left buttock. She was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 62/48 mmHg. The patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin 250 mg twice daily and hydrocodone/acetominophen 5 mg/325 mg twice daily as needed for pain management and was discharged. Six hours later, the patient presented to the emergency department with new onset symptoms of confusion and dark-colored spots on the abdomen and lower legs, which her family members noted had developed shortly after the patient took ciprofloxacin. In the emergency department, the patient was noted to be hypotensive and febrile with a severe metabolic acidosis. She was intubated for respiratory failure and received intravenous fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and vasopressors. Blood cultures were obtained, and the dermatology department was consulted.

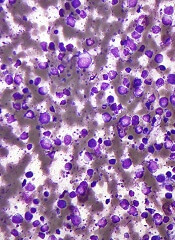

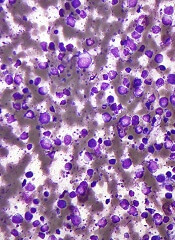

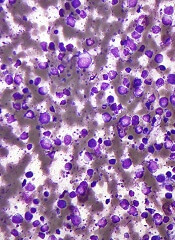

On physical examination, extensive purpuric, reticulated, and stellate plaques with central necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae were noted on the abdomen (Figure, A) and bilateral lower legs (Figure, B) extending onto the thighs. The patient was coagulopathic with persistent sanguineous oozing at intravenous sites and bilateral nares. A small erythematous ulcer with overlying black eschar was noted on the left medial buttock.

Laboratory test results showed new-onset thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time/international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time, and low fibrinogen levels, which confirmed a diagnosis of acute DIC. Blood cultures were positive for gram-negative rods in 4 out of 4 bottles within 12 hours of being drawn. Further testing identified the microorganism as E coli, and antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed it was sensitive to most antibiotics.

The patient was clinically diagnosed with purpura fulminans secondary to severe E coli septicemia and DIC. This life-threatening disorder is considered a medical emergency with a high mortality rate. Laboratory findings supporting DIC include the presence of schistocytes on a peripheral blood smear, thrombocytopenia, positive plasma protamine paracoagulation test, low fibrinogen levels, and positive fibrin degradation products. Reported cases of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia are rare, and meningococcemia is the most common presentation.2,3 Bacterial components (eg, lipopolysaccharides found in the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria) may contribute to the progression of septicemia. Increased levels of endotoxin lipopolysaccharide can lead to septic shock and organ dysfunction.4 However, the release of lipooligosaccharides is associated with the development of meningococcal septicemia, and the lipopolysaccharide levels are directly correlated with prognosis in patients without meningitis.5-7

Human activated protein C concentrate (and its precursor, protein C concentrate) replacement therapy has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with meningococcemia-associated–purpura fulminans and severe sepsis, respectively.8 Heparin may be considered in the treatment of patients with purpura fulminans in addition to the replacement of any missing clotting factors or blood products.9 The international guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock include early quantitative resuscitation of the patient during the first 6 hours after recognition of sepsis, performing blood cultures before antibiotic therapy, and administering broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy within 1 hour of recognition of septic shock.10 The elapsed time from triage to the actual administration of appropriate antimicrobials are primary determinants of patient mortality.11 Therefore, physicians must act quickly to stabilize the patient.

Gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative diplococci are common infectious agents implicated in purpura fulminans. Escherichia coli rarely has been identified as the inciting agent for purpura fulminans in adults. The increasing frequency of E coli strains that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases—enzymes that mediate resistance to extended-spectrum (third generation) cephalosporins (eg, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) and monobactams (eg, aztreonam)—complicates matters further when deciding on appropriate antibiotics. Patients who have infections from extended-spectrum β-lactamase strains will require more potent carbapenems (eg, meropenem, imipenem) for treatment of infections. Despite undergoing treatment for septicemia, our patient went into cardiac arrest within 24 hours of presentation to the emergency department and died a few hours later. Physicians should consider E coli as an inciting agent of purpura fulminans and consider appropriate empiric antibiotics with gram-negative coverage to include E coli.

- Madden RM, Gill JC, Marlar RA. Protein C and protein S levels in two patients with acquired purpura fulminans. Br J Haematol. 1990;75:112-117.

- Nolan J, Sinclair R. Review of management of purpura fulminans and two case reports. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:581-586.

- Huemer GM, Bonatti H, Dunst KM. Purpura fulminans due to E. coli septicemia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:82.

- Pugin J. Recognition of bacteria and bacterial products by host immune cells in sepsis. In: Vincent JL, ed. Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1997:11-12.

- Brandtzaeg P, Oktedalen O, Kierulf P, et al. Elevated VIP and endotoxin plasma levels in human gram-negative septic shock. Regul Pept. 1989;24:37-44.

- Brandtzaeg P, Kierulf P, Gaustad P, et al. Plasma endotoxin as a predictor of multiple organ failure and death in systemic meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:195-204.

- Brandtzaeg P, Ovstebøo R, Kierulf P. Compartmentalization of lipopolysaccharide production correlates with clinical presentation in meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:650-652.

- Hodgson A, Ryan T, Moriarty J, et al. Plasma exchange as a source of protein C for acute onset protein C pathway failure. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:905-908.

- Feinstein DI. Diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation: the role of heparin therapy. Blood. 1982;60:284-287.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines committee including the pediatric subgroup. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637.

- Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA, et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1045-1053.

To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans is a severe and rapidly fatal thrombotic disorder that can occur in association with either hereditary or acquired deficiencies of the natural anticoagulants protein C and protein S.1 It most commonly results from the acute inflammatory response and subsequent disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) seen in severe bacterial septicemia. Excessive bleeding, retiform purpura, and skin necrosis may develop as a result of the coagulopathies of typical DIC.1Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus frequently are implicated as pathogens, but Escherichia coli–associated purpura fulminans in adults is rare.2,3 We report a case of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of end-stage liver disease secondary to alcoholic liver cirrhosis diagnosed 13 years prior complicated by ascites and esophageal varices presented to a primary care clinic for evaluation of a recent-onset nontender lesion on the left buttock. She was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 62/48 mmHg. The patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin 250 mg twice daily and hydrocodone/acetominophen 5 mg/325 mg twice daily as needed for pain management and was discharged. Six hours later, the patient presented to the emergency department with new onset symptoms of confusion and dark-colored spots on the abdomen and lower legs, which her family members noted had developed shortly after the patient took ciprofloxacin. In the emergency department, the patient was noted to be hypotensive and febrile with a severe metabolic acidosis. She was intubated for respiratory failure and received intravenous fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and vasopressors. Blood cultures were obtained, and the dermatology department was consulted.

On physical examination, extensive purpuric, reticulated, and stellate plaques with central necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae were noted on the abdomen (Figure, A) and bilateral lower legs (Figure, B) extending onto the thighs. The patient was coagulopathic with persistent sanguineous oozing at intravenous sites and bilateral nares. A small erythematous ulcer with overlying black eschar was noted on the left medial buttock.

Laboratory test results showed new-onset thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time/international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time, and low fibrinogen levels, which confirmed a diagnosis of acute DIC. Blood cultures were positive for gram-negative rods in 4 out of 4 bottles within 12 hours of being drawn. Further testing identified the microorganism as E coli, and antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed it was sensitive to most antibiotics.

The patient was clinically diagnosed with purpura fulminans secondary to severe E coli septicemia and DIC. This life-threatening disorder is considered a medical emergency with a high mortality rate. Laboratory findings supporting DIC include the presence of schistocytes on a peripheral blood smear, thrombocytopenia, positive plasma protamine paracoagulation test, low fibrinogen levels, and positive fibrin degradation products. Reported cases of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia are rare, and meningococcemia is the most common presentation.2,3 Bacterial components (eg, lipopolysaccharides found in the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria) may contribute to the progression of septicemia. Increased levels of endotoxin lipopolysaccharide can lead to septic shock and organ dysfunction.4 However, the release of lipooligosaccharides is associated with the development of meningococcal septicemia, and the lipopolysaccharide levels are directly correlated with prognosis in patients without meningitis.5-7

Human activated protein C concentrate (and its precursor, protein C concentrate) replacement therapy has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with meningococcemia-associated–purpura fulminans and severe sepsis, respectively.8 Heparin may be considered in the treatment of patients with purpura fulminans in addition to the replacement of any missing clotting factors or blood products.9 The international guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock include early quantitative resuscitation of the patient during the first 6 hours after recognition of sepsis, performing blood cultures before antibiotic therapy, and administering broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy within 1 hour of recognition of septic shock.10 The elapsed time from triage to the actual administration of appropriate antimicrobials are primary determinants of patient mortality.11 Therefore, physicians must act quickly to stabilize the patient.

Gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative diplococci are common infectious agents implicated in purpura fulminans. Escherichia coli rarely has been identified as the inciting agent for purpura fulminans in adults. The increasing frequency of E coli strains that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases—enzymes that mediate resistance to extended-spectrum (third generation) cephalosporins (eg, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) and monobactams (eg, aztreonam)—complicates matters further when deciding on appropriate antibiotics. Patients who have infections from extended-spectrum β-lactamase strains will require more potent carbapenems (eg, meropenem, imipenem) for treatment of infections. Despite undergoing treatment for septicemia, our patient went into cardiac arrest within 24 hours of presentation to the emergency department and died a few hours later. Physicians should consider E coli as an inciting agent of purpura fulminans and consider appropriate empiric antibiotics with gram-negative coverage to include E coli.

To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans is a severe and rapidly fatal thrombotic disorder that can occur in association with either hereditary or acquired deficiencies of the natural anticoagulants protein C and protein S.1 It most commonly results from the acute inflammatory response and subsequent disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) seen in severe bacterial septicemia. Excessive bleeding, retiform purpura, and skin necrosis may develop as a result of the coagulopathies of typical DIC.1Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus frequently are implicated as pathogens, but Escherichia coli–associated purpura fulminans in adults is rare.2,3 We report a case of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of end-stage liver disease secondary to alcoholic liver cirrhosis diagnosed 13 years prior complicated by ascites and esophageal varices presented to a primary care clinic for evaluation of a recent-onset nontender lesion on the left buttock. She was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 62/48 mmHg. The patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin 250 mg twice daily and hydrocodone/acetominophen 5 mg/325 mg twice daily as needed for pain management and was discharged. Six hours later, the patient presented to the emergency department with new onset symptoms of confusion and dark-colored spots on the abdomen and lower legs, which her family members noted had developed shortly after the patient took ciprofloxacin. In the emergency department, the patient was noted to be hypotensive and febrile with a severe metabolic acidosis. She was intubated for respiratory failure and received intravenous fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and vasopressors. Blood cultures were obtained, and the dermatology department was consulted.

On physical examination, extensive purpuric, reticulated, and stellate plaques with central necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae were noted on the abdomen (Figure, A) and bilateral lower legs (Figure, B) extending onto the thighs. The patient was coagulopathic with persistent sanguineous oozing at intravenous sites and bilateral nares. A small erythematous ulcer with overlying black eschar was noted on the left medial buttock.

Laboratory test results showed new-onset thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time/international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time, and low fibrinogen levels, which confirmed a diagnosis of acute DIC. Blood cultures were positive for gram-negative rods in 4 out of 4 bottles within 12 hours of being drawn. Further testing identified the microorganism as E coli, and antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed it was sensitive to most antibiotics.

The patient was clinically diagnosed with purpura fulminans secondary to severe E coli septicemia and DIC. This life-threatening disorder is considered a medical emergency with a high mortality rate. Laboratory findings supporting DIC include the presence of schistocytes on a peripheral blood smear, thrombocytopenia, positive plasma protamine paracoagulation test, low fibrinogen levels, and positive fibrin degradation products. Reported cases of purpura fulminans in the setting of E coli septicemia are rare, and meningococcemia is the most common presentation.2,3 Bacterial components (eg, lipopolysaccharides found in the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria) may contribute to the progression of septicemia. Increased levels of endotoxin lipopolysaccharide can lead to septic shock and organ dysfunction.4 However, the release of lipooligosaccharides is associated with the development of meningococcal septicemia, and the lipopolysaccharide levels are directly correlated with prognosis in patients without meningitis.5-7

Human activated protein C concentrate (and its precursor, protein C concentrate) replacement therapy has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with meningococcemia-associated–purpura fulminans and severe sepsis, respectively.8 Heparin may be considered in the treatment of patients with purpura fulminans in addition to the replacement of any missing clotting factors or blood products.9 The international guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock include early quantitative resuscitation of the patient during the first 6 hours after recognition of sepsis, performing blood cultures before antibiotic therapy, and administering broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy within 1 hour of recognition of septic shock.10 The elapsed time from triage to the actual administration of appropriate antimicrobials are primary determinants of patient mortality.11 Therefore, physicians must act quickly to stabilize the patient.

Gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative diplococci are common infectious agents implicated in purpura fulminans. Escherichia coli rarely has been identified as the inciting agent for purpura fulminans in adults. The increasing frequency of E coli strains that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases—enzymes that mediate resistance to extended-spectrum (third generation) cephalosporins (eg, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) and monobactams (eg, aztreonam)—complicates matters further when deciding on appropriate antibiotics. Patients who have infections from extended-spectrum β-lactamase strains will require more potent carbapenems (eg, meropenem, imipenem) for treatment of infections. Despite undergoing treatment for septicemia, our patient went into cardiac arrest within 24 hours of presentation to the emergency department and died a few hours later. Physicians should consider E coli as an inciting agent of purpura fulminans and consider appropriate empiric antibiotics with gram-negative coverage to include E coli.

- Madden RM, Gill JC, Marlar RA. Protein C and protein S levels in two patients with acquired purpura fulminans. Br J Haematol. 1990;75:112-117.

- Nolan J, Sinclair R. Review of management of purpura fulminans and two case reports. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:581-586.

- Huemer GM, Bonatti H, Dunst KM. Purpura fulminans due to E. coli septicemia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:82.

- Pugin J. Recognition of bacteria and bacterial products by host immune cells in sepsis. In: Vincent JL, ed. Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1997:11-12.

- Brandtzaeg P, Oktedalen O, Kierulf P, et al. Elevated VIP and endotoxin plasma levels in human gram-negative septic shock. Regul Pept. 1989;24:37-44.

- Brandtzaeg P, Kierulf P, Gaustad P, et al. Plasma endotoxin as a predictor of multiple organ failure and death in systemic meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:195-204.

- Brandtzaeg P, Ovstebøo R, Kierulf P. Compartmentalization of lipopolysaccharide production correlates with clinical presentation in meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:650-652.

- Hodgson A, Ryan T, Moriarty J, et al. Plasma exchange as a source of protein C for acute onset protein C pathway failure. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:905-908.

- Feinstein DI. Diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation: the role of heparin therapy. Blood. 1982;60:284-287.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines committee including the pediatric subgroup. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637.

- Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA, et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1045-1053.

- Madden RM, Gill JC, Marlar RA. Protein C and protein S levels in two patients with acquired purpura fulminans. Br J Haematol. 1990;75:112-117.

- Nolan J, Sinclair R. Review of management of purpura fulminans and two case reports. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:581-586.

- Huemer GM, Bonatti H, Dunst KM. Purpura fulminans due to E. coli septicemia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:82.

- Pugin J. Recognition of bacteria and bacterial products by host immune cells in sepsis. In: Vincent JL, ed. Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1997:11-12.

- Brandtzaeg P, Oktedalen O, Kierulf P, et al. Elevated VIP and endotoxin plasma levels in human gram-negative septic shock. Regul Pept. 1989;24:37-44.

- Brandtzaeg P, Kierulf P, Gaustad P, et al. Plasma endotoxin as a predictor of multiple organ failure and death in systemic meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:195-204.

- Brandtzaeg P, Ovstebøo R, Kierulf P. Compartmentalization of lipopolysaccharide production correlates with clinical presentation in meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:650-652.

- Hodgson A, Ryan T, Moriarty J, et al. Plasma exchange as a source of protein C for acute onset protein C pathway failure. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:905-908.

- Feinstein DI. Diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation: the role of heparin therapy. Blood. 1982;60:284-287.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines committee including the pediatric subgroup. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637.

- Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA, et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1045-1053.

Team Hospitalist Advisory Board Accepting Applications for 2016-2018 Terms

The Hospitalist, the official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine, is always on the lookout for creative individuals dedicated to the field of hospital medicine to assist with editorial ideas and occasional writing.

Team Hospitalist is a voluntary, editorial advisory board made up of physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and administrators working in hospitalist groups all across the United States. Now in its eighth year, the 12-member group meets monthly to discuss hot topics in hospital medicine. Members are featured in the magazine and publish news articles at our website. Two-year terms will be seated during the SHM annual meeting this March in San Diego.

If interested in joining the team, send a cover letter of interest and CV to publication editor Jason Carris. Deadline to apply is Jan. 19, 2016.

The Hospitalist, the official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine, is always on the lookout for creative individuals dedicated to the field of hospital medicine to assist with editorial ideas and occasional writing.

Team Hospitalist is a voluntary, editorial advisory board made up of physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and administrators working in hospitalist groups all across the United States. Now in its eighth year, the 12-member group meets monthly to discuss hot topics in hospital medicine. Members are featured in the magazine and publish news articles at our website. Two-year terms will be seated during the SHM annual meeting this March in San Diego.

If interested in joining the team, send a cover letter of interest and CV to publication editor Jason Carris. Deadline to apply is Jan. 19, 2016.

The Hospitalist, the official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine, is always on the lookout for creative individuals dedicated to the field of hospital medicine to assist with editorial ideas and occasional writing.

Team Hospitalist is a voluntary, editorial advisory board made up of physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and administrators working in hospitalist groups all across the United States. Now in its eighth year, the 12-member group meets monthly to discuss hot topics in hospital medicine. Members are featured in the magazine and publish news articles at our website. Two-year terms will be seated during the SHM annual meeting this March in San Diego.

If interested in joining the team, send a cover letter of interest and CV to publication editor Jason Carris. Deadline to apply is Jan. 19, 2016.

AHA: Ezetimibe reduces ischemic stroke risk

ORLANDO – The combination of ezetimibe/simvastatin significantly reduced the risk of nonhemorrhagic stroke compared with simvastatin alone, with a particularly striking benefit seen in patients with prior history of stroke, in a new analysis from the landmark IMPROVE-IT trial.

“We believe these data support the use of intensive lipid lowering therapy, which includes ezetimibe to prevent ischemic stroke,” Dr. Stephen D. Wiviott said in reporting the findings at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented a prespecified secondary analysis from IMPROVE-IT, a double-blind study in which 18,144 patients on background optimal medical management were randomized post–acute coronary syndrome to simvastatin/ezetimibe at 40/10 mg/day (Vytorin) or simvastatin (Zocor) at 40 mg/day. At a median of 6 years of follow-up, the primary composite cardiovascular outcome was significantly reduced by 6% in the dual-therapy group compared with statin monotherapy, with a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 50, as previously reported (N Engl J Med. 2015 Jun 18;372[25]:2387-97).

The impetus for the prespecified stroke analysis was that up until IMPROVE-IT, no LDL cholesterol–lowering therapy other than statins had ever been shown to protect against stroke. The Cholesterol Trialists’ Collaboration meta-analysis, involving roughly 173,000 subjects, previously showed that statin therapy reduces ischemic stroke risk by 20% per 1 mmol/L of LDL lowering (Lancet. 2012 Aug 11;380[9841]:581-90). The question was, could add-on ezetimibe decrease stroke risk even further?

Stroke occurred in 641 patients during follow-up. As adjudicated by independent neurologists, 82% of the strokes were nonhemorrhagic, 16% were hemorrhagic, and 2% were unknown. The 14% relative risk reduction in overall stroke with simvastatin/ezetimibe compared with simvastatin, with rates of 4.2% versus 4.8%, just missed achieving statistical significance (P = .052). A significant 21% reduction in nonhemorrhagic strokes was seen with dual therapy, where the incidence during follow-up was 3.4%, compared with 4.1% with simvastatin alone, but this effect was dampened by a numeric albeit statistically nonsignificant absolute 0.2% increase in hemorrhagic strokes in the simvastatin/ezetimibe group.

Far more impressive was the stroke-prevention benefit of simvastatin/ezetimibe among the 1,071 subjects with prior stroke or TIA at baseline. Their nonhemorrhagic stroke rate during follow-up was 10.2% with simvastatin/ezetimibe versus 18.8% with simvastatin alone, for a 40% relative risk reduction favoring dual lipid-lowering therapy and an NNT of about 20. Again, there was no significant difference in hemorrhagic stroke between the two treatment arms, noted Dr. Wiviott of Brigham and Womens Hospital, Boston.

The stroke-prevention benefit achieved by adding ezetimibe to simvastatin was seen regardless of patient age, gender, renal function, baseline LDL cholesterol level, or other prespecified subcategories.

IMPROVE-IT was sponsored by Merck. Dr. Wiviott reported receiving research grants from Merck, AstraZeneca, and Eisai and serving as a consultant to nine pharmaceutical companies.

ORLANDO – The combination of ezetimibe/simvastatin significantly reduced the risk of nonhemorrhagic stroke compared with simvastatin alone, with a particularly striking benefit seen in patients with prior history of stroke, in a new analysis from the landmark IMPROVE-IT trial.

“We believe these data support the use of intensive lipid lowering therapy, which includes ezetimibe to prevent ischemic stroke,” Dr. Stephen D. Wiviott said in reporting the findings at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented a prespecified secondary analysis from IMPROVE-IT, a double-blind study in which 18,144 patients on background optimal medical management were randomized post–acute coronary syndrome to simvastatin/ezetimibe at 40/10 mg/day (Vytorin) or simvastatin (Zocor) at 40 mg/day. At a median of 6 years of follow-up, the primary composite cardiovascular outcome was significantly reduced by 6% in the dual-therapy group compared with statin monotherapy, with a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 50, as previously reported (N Engl J Med. 2015 Jun 18;372[25]:2387-97).

The impetus for the prespecified stroke analysis was that up until IMPROVE-IT, no LDL cholesterol–lowering therapy other than statins had ever been shown to protect against stroke. The Cholesterol Trialists’ Collaboration meta-analysis, involving roughly 173,000 subjects, previously showed that statin therapy reduces ischemic stroke risk by 20% per 1 mmol/L of LDL lowering (Lancet. 2012 Aug 11;380[9841]:581-90). The question was, could add-on ezetimibe decrease stroke risk even further?

Stroke occurred in 641 patients during follow-up. As adjudicated by independent neurologists, 82% of the strokes were nonhemorrhagic, 16% were hemorrhagic, and 2% were unknown. The 14% relative risk reduction in overall stroke with simvastatin/ezetimibe compared with simvastatin, with rates of 4.2% versus 4.8%, just missed achieving statistical significance (P = .052). A significant 21% reduction in nonhemorrhagic strokes was seen with dual therapy, where the incidence during follow-up was 3.4%, compared with 4.1% with simvastatin alone, but this effect was dampened by a numeric albeit statistically nonsignificant absolute 0.2% increase in hemorrhagic strokes in the simvastatin/ezetimibe group.

Far more impressive was the stroke-prevention benefit of simvastatin/ezetimibe among the 1,071 subjects with prior stroke or TIA at baseline. Their nonhemorrhagic stroke rate during follow-up was 10.2% with simvastatin/ezetimibe versus 18.8% with simvastatin alone, for a 40% relative risk reduction favoring dual lipid-lowering therapy and an NNT of about 20. Again, there was no significant difference in hemorrhagic stroke between the two treatment arms, noted Dr. Wiviott of Brigham and Womens Hospital, Boston.

The stroke-prevention benefit achieved by adding ezetimibe to simvastatin was seen regardless of patient age, gender, renal function, baseline LDL cholesterol level, or other prespecified subcategories.

IMPROVE-IT was sponsored by Merck. Dr. Wiviott reported receiving research grants from Merck, AstraZeneca, and Eisai and serving as a consultant to nine pharmaceutical companies.

ORLANDO – The combination of ezetimibe/simvastatin significantly reduced the risk of nonhemorrhagic stroke compared with simvastatin alone, with a particularly striking benefit seen in patients with prior history of stroke, in a new analysis from the landmark IMPROVE-IT trial.

“We believe these data support the use of intensive lipid lowering therapy, which includes ezetimibe to prevent ischemic stroke,” Dr. Stephen D. Wiviott said in reporting the findings at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented a prespecified secondary analysis from IMPROVE-IT, a double-blind study in which 18,144 patients on background optimal medical management were randomized post–acute coronary syndrome to simvastatin/ezetimibe at 40/10 mg/day (Vytorin) or simvastatin (Zocor) at 40 mg/day. At a median of 6 years of follow-up, the primary composite cardiovascular outcome was significantly reduced by 6% in the dual-therapy group compared with statin monotherapy, with a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 50, as previously reported (N Engl J Med. 2015 Jun 18;372[25]:2387-97).

The impetus for the prespecified stroke analysis was that up until IMPROVE-IT, no LDL cholesterol–lowering therapy other than statins had ever been shown to protect against stroke. The Cholesterol Trialists’ Collaboration meta-analysis, involving roughly 173,000 subjects, previously showed that statin therapy reduces ischemic stroke risk by 20% per 1 mmol/L of LDL lowering (Lancet. 2012 Aug 11;380[9841]:581-90). The question was, could add-on ezetimibe decrease stroke risk even further?

Stroke occurred in 641 patients during follow-up. As adjudicated by independent neurologists, 82% of the strokes were nonhemorrhagic, 16% were hemorrhagic, and 2% were unknown. The 14% relative risk reduction in overall stroke with simvastatin/ezetimibe compared with simvastatin, with rates of 4.2% versus 4.8%, just missed achieving statistical significance (P = .052). A significant 21% reduction in nonhemorrhagic strokes was seen with dual therapy, where the incidence during follow-up was 3.4%, compared with 4.1% with simvastatin alone, but this effect was dampened by a numeric albeit statistically nonsignificant absolute 0.2% increase in hemorrhagic strokes in the simvastatin/ezetimibe group.

Far more impressive was the stroke-prevention benefit of simvastatin/ezetimibe among the 1,071 subjects with prior stroke or TIA at baseline. Their nonhemorrhagic stroke rate during follow-up was 10.2% with simvastatin/ezetimibe versus 18.8% with simvastatin alone, for a 40% relative risk reduction favoring dual lipid-lowering therapy and an NNT of about 20. Again, there was no significant difference in hemorrhagic stroke between the two treatment arms, noted Dr. Wiviott of Brigham and Womens Hospital, Boston.

The stroke-prevention benefit achieved by adding ezetimibe to simvastatin was seen regardless of patient age, gender, renal function, baseline LDL cholesterol level, or other prespecified subcategories.

IMPROVE-IT was sponsored by Merck. Dr. Wiviott reported receiving research grants from Merck, AstraZeneca, and Eisai and serving as a consultant to nine pharmaceutical companies.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Intensive lipid-lowering therapy that incorporates ezetimibe provides enhanced protection against ischemic stroke.

Major finding: In patients with a baseline history of stroke who were on simvastatin/ezetimibe after an acute coronary syndrome, the risk of nonhemorrhagic stroke during 6 years of follow-up was reduced by 40%, compared with lipid-lowering via simvastatin alone.

Data source: A prespecified secondary analysis of stroke incidence during a median 6 years of follow-up in the double-blind, randomized, 18,144-patient IMPROVE-IT trial.

Disclosures: Merck sponsored the study. The presenter reported receiving a research grant from Merck and serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Delayed Adjuvant Chemotherapy Significantly Affects Breast Cancer Recovery

In an observational, population-based, investigational study published in JAMA online, researchers from University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and the Cancer Prevention Institute of California in Fremont hypothesized that prolonged time to chemotherapy (TTC) would be associated with adverse outcomes. Data from the California Cancer Registry were used to study 24,843 patients with stage I to stage III invasive breast cancer who were diagnosed between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2010.

The use of adjuvant chemotherapy has had a significant effect in decreasing the risk of reoccurrence and in improving survival rates among patients with early-stage breast cancer, said the researchers. Delaying adjuvant chemotherapy beyond the typical start of 30 to 40 days of surgery could decrease the benefits provided by cytotoxic systemic therapies.

Related: Extending Therapy for Breast Cancer

Researchers gathered patient information, including demographic characteristics (age, race, marital status, insurance type), other variables related to the cancer diagnosis and treatment, and data on patient’s tumor estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2) status. The participants were categorized into subgroups according to breast cancer subtype and TTC categories of ≤ 30 days, 31 to 60 days, 61 to 90 days, or ≥ 90 days. Ninety-one or more days from surgery to the first diagnosis of adjuvant chemotherapy was considered a delay.

After evaluating all the factors associated with a delay in adjuvant chemotherapy administration, the researchers observed that compared with stage I patients those with stage II and stage III were less likely to have delays in chemotherapy administration. It was also found that patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) were less likely to have delays compared with patients with hormone-receptor positive tumors. Other factors associated with delays in TTC included low socioeconomic status (SES), breast reconstruction, nonprivate insurance, and ethnicity.

Related: Gene Expression Signatures in Breast Cancer: A Surgical Oncologist’s Perspective

Data from the analysis also showed that patients who received chemotherapy ≥ 91 days after surgery had worse overall survival (OS) along with patients with hormone-receptor positive and TNBC who were treated within the same time frame. Older age, advanced-stage breast cancer, ethnicity, lower SES, and type of insurance coverage also contributed to worse OS.

Related: Advances in Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer

As a result of the analysis, the researchers suggest all breast cancer patients who are candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy should receive treatment within 9 days of surgery or 120 days from diagnosis. Better understanding and removing socioeconomic barriers to access of care should also be a priority for health care providers.

Source: Chavez-MacGregor M, Clarke CA, Lichtensztajin DY, et al. Delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015; doi: 10.10 01/jamaoncol. 2015.3856 [Published online December 10, 2015].

In an observational, population-based, investigational study published in JAMA online, researchers from University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and the Cancer Prevention Institute of California in Fremont hypothesized that prolonged time to chemotherapy (TTC) would be associated with adverse outcomes. Data from the California Cancer Registry were used to study 24,843 patients with stage I to stage III invasive breast cancer who were diagnosed between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2010.

The use of adjuvant chemotherapy has had a significant effect in decreasing the risk of reoccurrence and in improving survival rates among patients with early-stage breast cancer, said the researchers. Delaying adjuvant chemotherapy beyond the typical start of 30 to 40 days of surgery could decrease the benefits provided by cytotoxic systemic therapies.

Related: Extending Therapy for Breast Cancer

Researchers gathered patient information, including demographic characteristics (age, race, marital status, insurance type), other variables related to the cancer diagnosis and treatment, and data on patient’s tumor estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2) status. The participants were categorized into subgroups according to breast cancer subtype and TTC categories of ≤ 30 days, 31 to 60 days, 61 to 90 days, or ≥ 90 days. Ninety-one or more days from surgery to the first diagnosis of adjuvant chemotherapy was considered a delay.

After evaluating all the factors associated with a delay in adjuvant chemotherapy administration, the researchers observed that compared with stage I patients those with stage II and stage III were less likely to have delays in chemotherapy administration. It was also found that patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) were less likely to have delays compared with patients with hormone-receptor positive tumors. Other factors associated with delays in TTC included low socioeconomic status (SES), breast reconstruction, nonprivate insurance, and ethnicity.

Related: Gene Expression Signatures in Breast Cancer: A Surgical Oncologist’s Perspective

Data from the analysis also showed that patients who received chemotherapy ≥ 91 days after surgery had worse overall survival (OS) along with patients with hormone-receptor positive and TNBC who were treated within the same time frame. Older age, advanced-stage breast cancer, ethnicity, lower SES, and type of insurance coverage also contributed to worse OS.

Related: Advances in Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer

As a result of the analysis, the researchers suggest all breast cancer patients who are candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy should receive treatment within 9 days of surgery or 120 days from diagnosis. Better understanding and removing socioeconomic barriers to access of care should also be a priority for health care providers.

Source: Chavez-MacGregor M, Clarke CA, Lichtensztajin DY, et al. Delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015; doi: 10.10 01/jamaoncol. 2015.3856 [Published online December 10, 2015].

In an observational, population-based, investigational study published in JAMA online, researchers from University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and the Cancer Prevention Institute of California in Fremont hypothesized that prolonged time to chemotherapy (TTC) would be associated with adverse outcomes. Data from the California Cancer Registry were used to study 24,843 patients with stage I to stage III invasive breast cancer who were diagnosed between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2010.

The use of adjuvant chemotherapy has had a significant effect in decreasing the risk of reoccurrence and in improving survival rates among patients with early-stage breast cancer, said the researchers. Delaying adjuvant chemotherapy beyond the typical start of 30 to 40 days of surgery could decrease the benefits provided by cytotoxic systemic therapies.

Related: Extending Therapy for Breast Cancer

Researchers gathered patient information, including demographic characteristics (age, race, marital status, insurance type), other variables related to the cancer diagnosis and treatment, and data on patient’s tumor estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2) status. The participants were categorized into subgroups according to breast cancer subtype and TTC categories of ≤ 30 days, 31 to 60 days, 61 to 90 days, or ≥ 90 days. Ninety-one or more days from surgery to the first diagnosis of adjuvant chemotherapy was considered a delay.

After evaluating all the factors associated with a delay in adjuvant chemotherapy administration, the researchers observed that compared with stage I patients those with stage II and stage III were less likely to have delays in chemotherapy administration. It was also found that patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) were less likely to have delays compared with patients with hormone-receptor positive tumors. Other factors associated with delays in TTC included low socioeconomic status (SES), breast reconstruction, nonprivate insurance, and ethnicity.

Related: Gene Expression Signatures in Breast Cancer: A Surgical Oncologist’s Perspective