User login

The Daily Safety Brief in a Safety Net Hospital: Development and Outcomes

From the MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the process for the creation and development of the Daily Safety Brief (DSB) in our safety net hospital.

- Methods: We developed the DSB, a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. The average call length with 25 departments reporting is just 9.5 minutes.

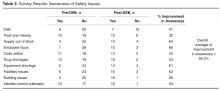

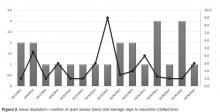

- Results: Survey results reveal an overall average improvement in awareness among DSB participants about hospital safety issues. Average days to issue resolution is currently 2.3 days, with open issues tracked and reported on daily.

- Conclusion: The DSB has improved real-time communication and awareness about safety issues in our organization.

As health care organizations strive to ensure a culture of safety for patients and staff, they must also be able to demonstrate reliability in that culture. The concept of highly reliable organizations originated in aviation and military fields due to the high-stakes environment and need for rapid and effective communication across departments. High reliability in health care organizations is described by the Joint Commission as consistent excellence in quality and safety for every patient, every time [1].

Highly reliable organizations put systems in place that makes them resilient with methods that lead to consistent accomplishment of goals and strategies to avoid potentially catastrophic errors [2]. An integral component to success in all high reliability organizations is a method of “Plan-of-the-Day” meetings to keep staff apprised of critical updates throughout the health system impacting care delivery [3]. Leaders at MetroHealth Medical Center believed that a daily safety briefing would help support the hospital’s journey to high reliability. We developed the Daily Safety Brief (DSB), a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis [4]. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. This article will describe the development and implementation of the DSB in our hospital.

Setting

MetroHealth Medical Center is an academic medical center in Cleveland, OH, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University. Metrohealth is a public safety net hospital with 731 licensed beds and a total of 1,160,773 patient visits in 2014, with 27,933 inpatient stays and 106,000 emergency department (ED) visits. The staff includes 507 physicians, 374 resident physicians, and 1222 nurses.

Program Development

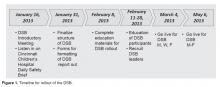

As Metrohealth was contemplating the DSB, a group of senior leaders, including the chief medical officer, visited the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, which had a DSB process in place. Following that visit, a larger group of physicians and administrators from intake points, procedural areas, and ancillary departments were invited to listen in live to Cincinnati’s DSB. This turned out to be a pivotal step in gaining buy-in. The initial concerns from participants were that this would be another scheduled meeting in an already busy day. What we learned from listening in was that the DSB was conducted in a manner that was succinct and professional. Issues were identified without accusations or unrelated agendas. Following the call, participants discussed how impressed they were and clearly saw the value of the information that was shared. They began to brainstorm about what they could report that would be relevant to the audience.

It was determined that a leader and 2 facilitators would be assigned to each call. The role of the DSB leader is to trigger individual department report outs and to ensure follow-up on unresolved safety issues from the previous DSB. Leaders are recruited by senior leadership and need to be familiar with the effects that issues can have across the health care system. Leaders need to be able to ask pertinent questions, have the credibility to raise concerns, and have access to senior administration when they need to bypass usual administrative channels.

The role of the facilitators, who are all members of the Center for Quality, is to connect to the conference bridge line, to keep the DSB leader on task, and to record all departmental data and pertinent details of the DSB. The facilitators maintain the daily DSB document, which outlines the order in which departments are called to report and identifies for the leader any open items identified in the previous day’s DSB.

The Daily Safety Brief

Rollout

The DSB began 3 days per week on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 0830. The time was moved to 0800 since participants found the later time difficult as it fell in the middle of an hour, potentially conflicting with other meetings and preparation for the daily bed huddle. We recognized that many meetings began right at the start of the DSB. The CEO requested that all 0800 meetings begin with a call in to listen to the DSB. After 2 months, the frequency was increased to 5 days per week, Monday through Friday. The hospital trialed a weekend DSB, however, feedback from participants found this extremely difficult to attend due to leaner weekend staffing models and found that information shared was not impactful. In particular, items were identified on the weekend daily safety briefs but the staff needed to resolve those items were generally not available until Monday.

Refinements

Coaching occurred to help people be more succinct in sharing information that would impact other areas. Information that was relevant only internally to their department was streamlined. The participants were counseled to identify items that had potential impact on other departments or where other departments had resources that might improve operations.

After a year, participating departments requested the addition of the logistics and construction departments to the DSB. The addition of the logistics department offered the opportunity for clinical departments to communicate what equipment was needed to start the day and created the opportunity for logistics to close the feedback loop by giving an estimate on expected time of arrival of equipment. The addition of the construction department helped communicate issues that may impact the organization, and helps to coordinate care to minimally impact patients and operations.

Examples of Safety Improvements

The DSB keeps the departmental leadership aware of problems developing in all areas of the hospital. Upcoming safety risks are identified early so that plans can be put in place to ameliorate them. The expectation of the DSB leader is that a problem that isn’t readily solved during the DSB must be taken to senior administration for resolution. As an example, an issue involving delays in the purchase of a required neonatal ventilator was taken directly to the CEO by the DSB leader, resulting in completion of the purchase within days. Importantly, the requirement to report at the DSB leads to a preoccupation with risk and reporting and leads to transparency among interdependent departments.

Another issue effectively addressed by the DSB was when we received notification of a required mandatory power shutdown for an extended period of time. The local power company informed our facilities management department director that they discovered issues requiring urgent replacement of the transformer within 2 weeks. Facilities management reported this in the morning DSB. The DSB leader requested all stakeholders to stay on the call following completion of the DSB, and plans were set in motion to plan for the shutdown of power. The team agreed to conference call again at noon the same day to continue planning, and the affected building was prepared for the shutdown by the following day.

Another benefit of the DSB is illustrated by our inpatient psychiatry unit, which reports an acuity measure each day on a scale of 1 to 10. The MetroHealth Police Department utilizes the report to adjust their rounding schedule, with increased presence on days with high acuity, which has led to an improvement in morale among psychiatry unit staff.

Challenges and Solutions

Since these reports are available to a wide audience in the organization, it is important to assure the reporters that no repercussions will ensue from any information that they provide. Senior leadership was enlisted to communicate with their departments that no repercussions would occur from reporting. As an example, some managers reported to the DSB development team privately that their supervisors were concerned about reporting of staff shortages on the DSB. As the shortages had patient care implications and affected other clinical departments, the DSB development team met with the involved supervisors to address the need for open reporting. In fact, repeated reporting of shortages in one support department on the DSB resulted in that issue being taken to high levels of administration leading to an increase in their staffing levels.

Scheduling can be a challenge for DSB participants. Holding the DSB at 0800 has led some departments to delegate the reporting or information gathering. For the individual reporting departments, creating a reporting workflow was a challenge. The departments needed to ensure that their DSB report was ready to go by 0800. This timeline forced departments to improve their own interdepartmental communication structure. An unexpected benefit of this requirement is that some departments have created a morning huddle to share information, which has reportedly improved communication and morale. The ambulatory network created a separate shared database for clinics to post concerns meeting DSB reporting criteria. One designated staff member would access this collective information when preparing for the DSB report. While most departments have a senior manager providing their report, this is not a requirement. In many departments, that reporter varies from day to day, although consistently it is someone with some administrative or leadership role in the department.

Conference call technology presented the solution to the problem of acquiring a meeting space for a large group. The DSB is broadcast from one physical location, where the facilitators and leader convene. While this conference room is open to anyone who wants to attend in person, most departments choose to participate through the conference line. The DSB conference call is open to anyone in the organization to access. Typically 35 to 40 phones are accessing the line each DSB. Challenges included callers not muting their phones, creating distracting background noise, and callers placing their phones on hold, which prompted the hospital hold message to play continuously. Multiple repeated reminders via email and at the start of the DSB has rectified this issue for the most part, with occasional reminders made when the issue recurs.

Data Management

Initially, an Excel file was created with columns for each reporting department as well as each item they were asked to report on. This “running” file became cumbersome. Retrieving information on past issues was not automated. Therefore, we enlisted the help of a data analyst to create an Access database. When it was complete, this new database allowed us to save information by individual dates, query number of days to issue resolution, and create reports noting unresolved issues for the leader to reference. Many data points can be queried in the access database. Real-time reports are available at all times and updated with every data entry. The database is able to identify departments not on the daily call and trend information, ie, how many listeners were on the DSB, number of falls, forensic patients in house, number of patients awaiting admission from the ED, number of ambulatory visits scheduled each day, equipment needed, number of cardiac arrest calls, and number of neonatal resuscitations.

At the conclusion of the call, the DSB report is completed and posted to a shared website on the hospital intranet for the entire hospital to access and read. Feedback from participant indicated that they found it cumbersome to access this. The communications department was enlisted to enable easy access and staff can now access the DSB report from the front page of the hospital intranet.

Outcomes

Since initiation of our DSB, we have tracked the average number of minutes spent on each call. When calls began, the average time on the call was 12.4 minutes. With the evolution of the DSB and coaching managers in various departments, the average time on the call is now 9.5 minutes in 2015, despite additional reporting departments joining the DSB.

Summary

The DSB has become an important tool in creating and moving towards a culture of safety and high reliability within the MetroHealth System. Over time, processes have become organized and engrained in all departments. This format has allowed issues to be brought forward timely where immediate attention can be given to achieve resolution in a nonthreatening manner, improving transparency. The fluidity of the DSB allows it to be enhanced and modified as improvements and opportunities are identified in the organization. The DSB has provided opportunities to create situational awareness which allows a look forward to prevention and creates a proactive environment. The results of these efforts has made MetroHealth a safer place for patients, visitors, and employees.

Corresponding author: Anne M. Aulisio, MSN, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Available at www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org.

2. Gamble M. 5 traits of high reliability organizations: how to hardwire each in your organization. Becker’s Hospital Review 29 Apr 2013. Accessed at www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/5-traits-of-high-reliability-organizations-how-to-hardwire-each-in-your-organization.html.

3. Stockmeier C, Clapper C. Daily check-in for safety: from best practice to common practice. Patient Safety Qual Healthcare 2011:23. Accessed at psqh.com/daily-check-in-for-safety-from-best-practice-to-common-practice.

4. Creating situational awareness: a systems approach. In: Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events. Medical surge capacity: workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32859/.

5. TeamSTEPPS. Available at www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/index.html.

From the MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the process for the creation and development of the Daily Safety Brief (DSB) in our safety net hospital.

- Methods: We developed the DSB, a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. The average call length with 25 departments reporting is just 9.5 minutes.

- Results: Survey results reveal an overall average improvement in awareness among DSB participants about hospital safety issues. Average days to issue resolution is currently 2.3 days, with open issues tracked and reported on daily.

- Conclusion: The DSB has improved real-time communication and awareness about safety issues in our organization.

As health care organizations strive to ensure a culture of safety for patients and staff, they must also be able to demonstrate reliability in that culture. The concept of highly reliable organizations originated in aviation and military fields due to the high-stakes environment and need for rapid and effective communication across departments. High reliability in health care organizations is described by the Joint Commission as consistent excellence in quality and safety for every patient, every time [1].

Highly reliable organizations put systems in place that makes them resilient with methods that lead to consistent accomplishment of goals and strategies to avoid potentially catastrophic errors [2]. An integral component to success in all high reliability organizations is a method of “Plan-of-the-Day” meetings to keep staff apprised of critical updates throughout the health system impacting care delivery [3]. Leaders at MetroHealth Medical Center believed that a daily safety briefing would help support the hospital’s journey to high reliability. We developed the Daily Safety Brief (DSB), a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis [4]. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. This article will describe the development and implementation of the DSB in our hospital.

Setting

MetroHealth Medical Center is an academic medical center in Cleveland, OH, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University. Metrohealth is a public safety net hospital with 731 licensed beds and a total of 1,160,773 patient visits in 2014, with 27,933 inpatient stays and 106,000 emergency department (ED) visits. The staff includes 507 physicians, 374 resident physicians, and 1222 nurses.

Program Development

As Metrohealth was contemplating the DSB, a group of senior leaders, including the chief medical officer, visited the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, which had a DSB process in place. Following that visit, a larger group of physicians and administrators from intake points, procedural areas, and ancillary departments were invited to listen in live to Cincinnati’s DSB. This turned out to be a pivotal step in gaining buy-in. The initial concerns from participants were that this would be another scheduled meeting in an already busy day. What we learned from listening in was that the DSB was conducted in a manner that was succinct and professional. Issues were identified without accusations or unrelated agendas. Following the call, participants discussed how impressed they were and clearly saw the value of the information that was shared. They began to brainstorm about what they could report that would be relevant to the audience.

It was determined that a leader and 2 facilitators would be assigned to each call. The role of the DSB leader is to trigger individual department report outs and to ensure follow-up on unresolved safety issues from the previous DSB. Leaders are recruited by senior leadership and need to be familiar with the effects that issues can have across the health care system. Leaders need to be able to ask pertinent questions, have the credibility to raise concerns, and have access to senior administration when they need to bypass usual administrative channels.

The role of the facilitators, who are all members of the Center for Quality, is to connect to the conference bridge line, to keep the DSB leader on task, and to record all departmental data and pertinent details of the DSB. The facilitators maintain the daily DSB document, which outlines the order in which departments are called to report and identifies for the leader any open items identified in the previous day’s DSB.

The Daily Safety Brief

Rollout

The DSB began 3 days per week on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 0830. The time was moved to 0800 since participants found the later time difficult as it fell in the middle of an hour, potentially conflicting with other meetings and preparation for the daily bed huddle. We recognized that many meetings began right at the start of the DSB. The CEO requested that all 0800 meetings begin with a call in to listen to the DSB. After 2 months, the frequency was increased to 5 days per week, Monday through Friday. The hospital trialed a weekend DSB, however, feedback from participants found this extremely difficult to attend due to leaner weekend staffing models and found that information shared was not impactful. In particular, items were identified on the weekend daily safety briefs but the staff needed to resolve those items were generally not available until Monday.

Refinements

Coaching occurred to help people be more succinct in sharing information that would impact other areas. Information that was relevant only internally to their department was streamlined. The participants were counseled to identify items that had potential impact on other departments or where other departments had resources that might improve operations.

After a year, participating departments requested the addition of the logistics and construction departments to the DSB. The addition of the logistics department offered the opportunity for clinical departments to communicate what equipment was needed to start the day and created the opportunity for logistics to close the feedback loop by giving an estimate on expected time of arrival of equipment. The addition of the construction department helped communicate issues that may impact the organization, and helps to coordinate care to minimally impact patients and operations.

Examples of Safety Improvements

The DSB keeps the departmental leadership aware of problems developing in all areas of the hospital. Upcoming safety risks are identified early so that plans can be put in place to ameliorate them. The expectation of the DSB leader is that a problem that isn’t readily solved during the DSB must be taken to senior administration for resolution. As an example, an issue involving delays in the purchase of a required neonatal ventilator was taken directly to the CEO by the DSB leader, resulting in completion of the purchase within days. Importantly, the requirement to report at the DSB leads to a preoccupation with risk and reporting and leads to transparency among interdependent departments.

Another issue effectively addressed by the DSB was when we received notification of a required mandatory power shutdown for an extended period of time. The local power company informed our facilities management department director that they discovered issues requiring urgent replacement of the transformer within 2 weeks. Facilities management reported this in the morning DSB. The DSB leader requested all stakeholders to stay on the call following completion of the DSB, and plans were set in motion to plan for the shutdown of power. The team agreed to conference call again at noon the same day to continue planning, and the affected building was prepared for the shutdown by the following day.

Another benefit of the DSB is illustrated by our inpatient psychiatry unit, which reports an acuity measure each day on a scale of 1 to 10. The MetroHealth Police Department utilizes the report to adjust their rounding schedule, with increased presence on days with high acuity, which has led to an improvement in morale among psychiatry unit staff.

Challenges and Solutions

Since these reports are available to a wide audience in the organization, it is important to assure the reporters that no repercussions will ensue from any information that they provide. Senior leadership was enlisted to communicate with their departments that no repercussions would occur from reporting. As an example, some managers reported to the DSB development team privately that their supervisors were concerned about reporting of staff shortages on the DSB. As the shortages had patient care implications and affected other clinical departments, the DSB development team met with the involved supervisors to address the need for open reporting. In fact, repeated reporting of shortages in one support department on the DSB resulted in that issue being taken to high levels of administration leading to an increase in their staffing levels.

Scheduling can be a challenge for DSB participants. Holding the DSB at 0800 has led some departments to delegate the reporting or information gathering. For the individual reporting departments, creating a reporting workflow was a challenge. The departments needed to ensure that their DSB report was ready to go by 0800. This timeline forced departments to improve their own interdepartmental communication structure. An unexpected benefit of this requirement is that some departments have created a morning huddle to share information, which has reportedly improved communication and morale. The ambulatory network created a separate shared database for clinics to post concerns meeting DSB reporting criteria. One designated staff member would access this collective information when preparing for the DSB report. While most departments have a senior manager providing their report, this is not a requirement. In many departments, that reporter varies from day to day, although consistently it is someone with some administrative or leadership role in the department.

Conference call technology presented the solution to the problem of acquiring a meeting space for a large group. The DSB is broadcast from one physical location, where the facilitators and leader convene. While this conference room is open to anyone who wants to attend in person, most departments choose to participate through the conference line. The DSB conference call is open to anyone in the organization to access. Typically 35 to 40 phones are accessing the line each DSB. Challenges included callers not muting their phones, creating distracting background noise, and callers placing their phones on hold, which prompted the hospital hold message to play continuously. Multiple repeated reminders via email and at the start of the DSB has rectified this issue for the most part, with occasional reminders made when the issue recurs.

Data Management

Initially, an Excel file was created with columns for each reporting department as well as each item they were asked to report on. This “running” file became cumbersome. Retrieving information on past issues was not automated. Therefore, we enlisted the help of a data analyst to create an Access database. When it was complete, this new database allowed us to save information by individual dates, query number of days to issue resolution, and create reports noting unresolved issues for the leader to reference. Many data points can be queried in the access database. Real-time reports are available at all times and updated with every data entry. The database is able to identify departments not on the daily call and trend information, ie, how many listeners were on the DSB, number of falls, forensic patients in house, number of patients awaiting admission from the ED, number of ambulatory visits scheduled each day, equipment needed, number of cardiac arrest calls, and number of neonatal resuscitations.

At the conclusion of the call, the DSB report is completed and posted to a shared website on the hospital intranet for the entire hospital to access and read. Feedback from participant indicated that they found it cumbersome to access this. The communications department was enlisted to enable easy access and staff can now access the DSB report from the front page of the hospital intranet.

Outcomes

Since initiation of our DSB, we have tracked the average number of minutes spent on each call. When calls began, the average time on the call was 12.4 minutes. With the evolution of the DSB and coaching managers in various departments, the average time on the call is now 9.5 minutes in 2015, despite additional reporting departments joining the DSB.

Summary

The DSB has become an important tool in creating and moving towards a culture of safety and high reliability within the MetroHealth System. Over time, processes have become organized and engrained in all departments. This format has allowed issues to be brought forward timely where immediate attention can be given to achieve resolution in a nonthreatening manner, improving transparency. The fluidity of the DSB allows it to be enhanced and modified as improvements and opportunities are identified in the organization. The DSB has provided opportunities to create situational awareness which allows a look forward to prevention and creates a proactive environment. The results of these efforts has made MetroHealth a safer place for patients, visitors, and employees.

Corresponding author: Anne M. Aulisio, MSN, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the process for the creation and development of the Daily Safety Brief (DSB) in our safety net hospital.

- Methods: We developed the DSB, a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. The average call length with 25 departments reporting is just 9.5 minutes.

- Results: Survey results reveal an overall average improvement in awareness among DSB participants about hospital safety issues. Average days to issue resolution is currently 2.3 days, with open issues tracked and reported on daily.

- Conclusion: The DSB has improved real-time communication and awareness about safety issues in our organization.

As health care organizations strive to ensure a culture of safety for patients and staff, they must also be able to demonstrate reliability in that culture. The concept of highly reliable organizations originated in aviation and military fields due to the high-stakes environment and need for rapid and effective communication across departments. High reliability in health care organizations is described by the Joint Commission as consistent excellence in quality and safety for every patient, every time [1].

Highly reliable organizations put systems in place that makes them resilient with methods that lead to consistent accomplishment of goals and strategies to avoid potentially catastrophic errors [2]. An integral component to success in all high reliability organizations is a method of “Plan-of-the-Day” meetings to keep staff apprised of critical updates throughout the health system impacting care delivery [3]. Leaders at MetroHealth Medical Center believed that a daily safety briefing would help support the hospital’s journey to high reliability. We developed the Daily Safety Brief (DSB), a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis [4]. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. This article will describe the development and implementation of the DSB in our hospital.

Setting

MetroHealth Medical Center is an academic medical center in Cleveland, OH, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University. Metrohealth is a public safety net hospital with 731 licensed beds and a total of 1,160,773 patient visits in 2014, with 27,933 inpatient stays and 106,000 emergency department (ED) visits. The staff includes 507 physicians, 374 resident physicians, and 1222 nurses.

Program Development

As Metrohealth was contemplating the DSB, a group of senior leaders, including the chief medical officer, visited the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, which had a DSB process in place. Following that visit, a larger group of physicians and administrators from intake points, procedural areas, and ancillary departments were invited to listen in live to Cincinnati’s DSB. This turned out to be a pivotal step in gaining buy-in. The initial concerns from participants were that this would be another scheduled meeting in an already busy day. What we learned from listening in was that the DSB was conducted in a manner that was succinct and professional. Issues were identified without accusations or unrelated agendas. Following the call, participants discussed how impressed they were and clearly saw the value of the information that was shared. They began to brainstorm about what they could report that would be relevant to the audience.

It was determined that a leader and 2 facilitators would be assigned to each call. The role of the DSB leader is to trigger individual department report outs and to ensure follow-up on unresolved safety issues from the previous DSB. Leaders are recruited by senior leadership and need to be familiar with the effects that issues can have across the health care system. Leaders need to be able to ask pertinent questions, have the credibility to raise concerns, and have access to senior administration when they need to bypass usual administrative channels.

The role of the facilitators, who are all members of the Center for Quality, is to connect to the conference bridge line, to keep the DSB leader on task, and to record all departmental data and pertinent details of the DSB. The facilitators maintain the daily DSB document, which outlines the order in which departments are called to report and identifies for the leader any open items identified in the previous day’s DSB.

The Daily Safety Brief

Rollout

The DSB began 3 days per week on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 0830. The time was moved to 0800 since participants found the later time difficult as it fell in the middle of an hour, potentially conflicting with other meetings and preparation for the daily bed huddle. We recognized that many meetings began right at the start of the DSB. The CEO requested that all 0800 meetings begin with a call in to listen to the DSB. After 2 months, the frequency was increased to 5 days per week, Monday through Friday. The hospital trialed a weekend DSB, however, feedback from participants found this extremely difficult to attend due to leaner weekend staffing models and found that information shared was not impactful. In particular, items were identified on the weekend daily safety briefs but the staff needed to resolve those items were generally not available until Monday.

Refinements

Coaching occurred to help people be more succinct in sharing information that would impact other areas. Information that was relevant only internally to their department was streamlined. The participants were counseled to identify items that had potential impact on other departments or where other departments had resources that might improve operations.

After a year, participating departments requested the addition of the logistics and construction departments to the DSB. The addition of the logistics department offered the opportunity for clinical departments to communicate what equipment was needed to start the day and created the opportunity for logistics to close the feedback loop by giving an estimate on expected time of arrival of equipment. The addition of the construction department helped communicate issues that may impact the organization, and helps to coordinate care to minimally impact patients and operations.

Examples of Safety Improvements

The DSB keeps the departmental leadership aware of problems developing in all areas of the hospital. Upcoming safety risks are identified early so that plans can be put in place to ameliorate them. The expectation of the DSB leader is that a problem that isn’t readily solved during the DSB must be taken to senior administration for resolution. As an example, an issue involving delays in the purchase of a required neonatal ventilator was taken directly to the CEO by the DSB leader, resulting in completion of the purchase within days. Importantly, the requirement to report at the DSB leads to a preoccupation with risk and reporting and leads to transparency among interdependent departments.

Another issue effectively addressed by the DSB was when we received notification of a required mandatory power shutdown for an extended period of time. The local power company informed our facilities management department director that they discovered issues requiring urgent replacement of the transformer within 2 weeks. Facilities management reported this in the morning DSB. The DSB leader requested all stakeholders to stay on the call following completion of the DSB, and plans were set in motion to plan for the shutdown of power. The team agreed to conference call again at noon the same day to continue planning, and the affected building was prepared for the shutdown by the following day.

Another benefit of the DSB is illustrated by our inpatient psychiatry unit, which reports an acuity measure each day on a scale of 1 to 10. The MetroHealth Police Department utilizes the report to adjust their rounding schedule, with increased presence on days with high acuity, which has led to an improvement in morale among psychiatry unit staff.

Challenges and Solutions

Since these reports are available to a wide audience in the organization, it is important to assure the reporters that no repercussions will ensue from any information that they provide. Senior leadership was enlisted to communicate with their departments that no repercussions would occur from reporting. As an example, some managers reported to the DSB development team privately that their supervisors were concerned about reporting of staff shortages on the DSB. As the shortages had patient care implications and affected other clinical departments, the DSB development team met with the involved supervisors to address the need for open reporting. In fact, repeated reporting of shortages in one support department on the DSB resulted in that issue being taken to high levels of administration leading to an increase in their staffing levels.

Scheduling can be a challenge for DSB participants. Holding the DSB at 0800 has led some departments to delegate the reporting or information gathering. For the individual reporting departments, creating a reporting workflow was a challenge. The departments needed to ensure that their DSB report was ready to go by 0800. This timeline forced departments to improve their own interdepartmental communication structure. An unexpected benefit of this requirement is that some departments have created a morning huddle to share information, which has reportedly improved communication and morale. The ambulatory network created a separate shared database for clinics to post concerns meeting DSB reporting criteria. One designated staff member would access this collective information when preparing for the DSB report. While most departments have a senior manager providing their report, this is not a requirement. In many departments, that reporter varies from day to day, although consistently it is someone with some administrative or leadership role in the department.

Conference call technology presented the solution to the problem of acquiring a meeting space for a large group. The DSB is broadcast from one physical location, where the facilitators and leader convene. While this conference room is open to anyone who wants to attend in person, most departments choose to participate through the conference line. The DSB conference call is open to anyone in the organization to access. Typically 35 to 40 phones are accessing the line each DSB. Challenges included callers not muting their phones, creating distracting background noise, and callers placing their phones on hold, which prompted the hospital hold message to play continuously. Multiple repeated reminders via email and at the start of the DSB has rectified this issue for the most part, with occasional reminders made when the issue recurs.

Data Management

Initially, an Excel file was created with columns for each reporting department as well as each item they were asked to report on. This “running” file became cumbersome. Retrieving information on past issues was not automated. Therefore, we enlisted the help of a data analyst to create an Access database. When it was complete, this new database allowed us to save information by individual dates, query number of days to issue resolution, and create reports noting unresolved issues for the leader to reference. Many data points can be queried in the access database. Real-time reports are available at all times and updated with every data entry. The database is able to identify departments not on the daily call and trend information, ie, how many listeners were on the DSB, number of falls, forensic patients in house, number of patients awaiting admission from the ED, number of ambulatory visits scheduled each day, equipment needed, number of cardiac arrest calls, and number of neonatal resuscitations.

At the conclusion of the call, the DSB report is completed and posted to a shared website on the hospital intranet for the entire hospital to access and read. Feedback from participant indicated that they found it cumbersome to access this. The communications department was enlisted to enable easy access and staff can now access the DSB report from the front page of the hospital intranet.

Outcomes

Since initiation of our DSB, we have tracked the average number of minutes spent on each call. When calls began, the average time on the call was 12.4 minutes. With the evolution of the DSB and coaching managers in various departments, the average time on the call is now 9.5 minutes in 2015, despite additional reporting departments joining the DSB.

Summary

The DSB has become an important tool in creating and moving towards a culture of safety and high reliability within the MetroHealth System. Over time, processes have become organized and engrained in all departments. This format has allowed issues to be brought forward timely where immediate attention can be given to achieve resolution in a nonthreatening manner, improving transparency. The fluidity of the DSB allows it to be enhanced and modified as improvements and opportunities are identified in the organization. The DSB has provided opportunities to create situational awareness which allows a look forward to prevention and creates a proactive environment. The results of these efforts has made MetroHealth a safer place for patients, visitors, and employees.

Corresponding author: Anne M. Aulisio, MSN, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Available at www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org.

2. Gamble M. 5 traits of high reliability organizations: how to hardwire each in your organization. Becker’s Hospital Review 29 Apr 2013. Accessed at www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/5-traits-of-high-reliability-organizations-how-to-hardwire-each-in-your-organization.html.

3. Stockmeier C, Clapper C. Daily check-in for safety: from best practice to common practice. Patient Safety Qual Healthcare 2011:23. Accessed at psqh.com/daily-check-in-for-safety-from-best-practice-to-common-practice.

4. Creating situational awareness: a systems approach. In: Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events. Medical surge capacity: workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32859/.

5. TeamSTEPPS. Available at www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/index.html.

1. Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Available at www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org.

2. Gamble M. 5 traits of high reliability organizations: how to hardwire each in your organization. Becker’s Hospital Review 29 Apr 2013. Accessed at www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/5-traits-of-high-reliability-organizations-how-to-hardwire-each-in-your-organization.html.

3. Stockmeier C, Clapper C. Daily check-in for safety: from best practice to common practice. Patient Safety Qual Healthcare 2011:23. Accessed at psqh.com/daily-check-in-for-safety-from-best-practice-to-common-practice.

4. Creating situational awareness: a systems approach. In: Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events. Medical surge capacity: workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32859/.

5. TeamSTEPPS. Available at www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/index.html.

High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation May Lead to Increased Risk of Falls

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the effectiveness of high-dose vitamin D versus low-dose vitamin D in reducing the risk of functional decline in older adults.

Design. Double-blind randomized controlled trial.

Setting and participants. This single-center study was conducted at the University of Zurich. Home-dwelling adults aged 70 and over were recruited through newspaper advertisement in Zurich from December 2009 to May 2010. Inclusion criteria included maintenance of mobility with or without a walking aid, having the ability to use public transportation to attend clinic visits, and scoring at least 27 on the Mini-Mental State Examination. Exclusion criteria include supplemental vitamin D use exceeding 800 IU per day and unwillingness to discontinue additional calcium and vitamin D supplementation, current cancer, malabsorption syndrome, heavy alcohol consumption, uncontrolled hypocalcemia, severe visual or hearing impairment, use of medications affecting calcium metabolism, diseases causing hypercalcemia, planned travel to sunny locations for longer than 2 months per year, maximum calcium supplement dose of 250 mg/day, use of medications affecting serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) level, body mass index ≥ 40, diseases predisposing to falls, hypercalcemia, kidney disease with creatinine clearance < 15, or kidney stone within 10 years prior to enrollment.

Intervention. Participants were randomized to receive either monthly supplementation of 24,000 IU of vitamin D3 per month (low-dose group), 60,000 IU of vitamin D3 once per month (high-dose group), or 24,000 IU of vitamin D3 plus 300 µg of calcifediol once per month. It was hypothesized that higher monthly doses of vitamin D or in combination with calcifediol, which is a liver metabolite approximately 2 to 3 times more potent than vitamin D3, will increase levels of 25(OH)D and reduce the risk of functional decline.

Main outcome measures. Lower extremity function using the Short Physical Performance Battery and 25(OH)D levels at 6 and 12 months. Study nurses called participants monthly to assess falls, adverse events, and adherence to study medications.

Main results. A total of 200 participants were enrolled. Average age was 78 years (SD = 5) and 67% were female; all had a history of falls in the previous year and average baseline 25(OH)D levels ranged from 18.4 to 20.9 ng/mL in the three groups. Adherence to the study medication exceeded 94% throughout the study trial in all treatment groups.

At 6 and 12 months, 25(OH)D levels increased by an average of 12.7 and 11.7 ng/mL in the low-dose group, an average of 18.3 and 19.2 ng/mL in the high-dose group, and an average of 27.6 and 25.8 ng/mL in the calcifediol-added group. The mean changes in physical performance score indicating lower extremity function did not differ significantly among treatment groups (P = 0.26), but for one measure—the 5 successive chair stands—the 2 high-dose groups had less improvement when compared with the low-dose group. At 12 months, 66.9% of the high-dose group and 66.1% in the group with calcifediol fell during the study period, which was more than the low-dose group (47.9%, P = 0.048). The mean number of falls was also higher among the high-dose and calcifediol groups when compared with the low-dose group.

Conclusion. Higher doses of vitamin D were not better than lower doses of vitamin D in improving lower extremity function and were associated with higher risk of falls.

Commentary

Vitamin D deficiency is common among older adults and is associated with sarcopenia, functional decline, falls, and fractures [1,2]. Prior meta-analysis has supported that supplementation with vitamin D may lead to improved outcomes in fracture prevention [3]. However, the US Preventive Services Task Force, using more recent evidence reviews and an updated meta-analysis [4], found evidence lacking regarding the benefit of supplementation with vitamin D in community-dwelling postmenopausal women at doses > 400 IU, found no benefit in this group for doses ≤ 400, and found evidence lacking for supplementation in men or premenopausal women at any dose [5]. At the same time, the USPSTF also recommends exercise or physical therapy and vitamin D supplementation (800 IU daily) to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults ≥ 65 years at increased risk for falls [6]. This is consistent with the Institute of Medicine’s recommendation of 800 IU per day for older adults [7].

The current study attempted to elucidate the potential impact of high-dose vitamin D supplementation, hypothesizing that higher doses will achieve improvement in vitamin D levels and better outcomes in terms of lower extremity function and falls. However, the investigators found that rather than lowering risk of falls, higher-dose vitamin D was associated with elevated risk of falls without the benefit of improving lower extremity function. This is not the first study that has demonstrated that higher doses of vitamin D supplementation may be associated with harm. A prior randomized controlled trial utilizing a different dosing strategy of annual high- dose vitamin D supplementation also found that higher doses were associated with increased risks of falls [8]. Nonetheless, it helps support the notion that in vitamin D supplementation, more is not necessarily better.

The study is not without its drawbacks. The sample size was relatively small and the trial may have been underpowered to detect whether there may be certain patients for whom high-dose vitamin D supplementation may have a role. Also, the study was based in Zurich, which has a relatively uniform population, and study results may not be generalizable to populations in other countries.

Applications for Clinical Practice

The study lends support to the current recommendation of the Institute of Medicine—800 IU a day—for fall prevention, which is equivalent in dose to the 24,000 IU per month utilized in the trial. One of the questions not answered by the study is whether high-dose supplementation for adults who have severe deficiency in vitamin D is beneficial or harmful when compared with lower-dose supplementation. In clinical practice, clinicians often check an initial level of vitamin D and aim for a target level with supplementation. Among those patients with extremely low baseline levels, a lower-dose regimen of 800 IU a day may not yield a normalized level of vitamin D. Further studies are needed to elucidate whether there may be a role for higher-dose supplementation in these individuals. Nonetheless, it is clear that the current evidence does not support the routine use of high-dose vitamin D supplementation; it does not lead to better lower extremity function and may cause harm.

—William Hung, MD, MPH

1. Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P; Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels as determinants of loss of muscle strength and muscle mass (sarcopenia): the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:5766–72.

2. Cauley JA, Lacroix AZ, Wu L, et al. Serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D concentrations and risk for hip fractures. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:242–50.

3. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, et al. Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2005;293:2257–64.

4. Chung M, Lee J, Terasawa T, et al. Vitamin D with or without calcium supplementation for prevention of cancer and fractures: an updated meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:827–38.

5. Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:691–6.

6. Moyer VA et al. Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults: U.S. Prevention Services Task Force Recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:197–204.

7. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

8. Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:1815.

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the effectiveness of high-dose vitamin D versus low-dose vitamin D in reducing the risk of functional decline in older adults.

Design. Double-blind randomized controlled trial.

Setting and participants. This single-center study was conducted at the University of Zurich. Home-dwelling adults aged 70 and over were recruited through newspaper advertisement in Zurich from December 2009 to May 2010. Inclusion criteria included maintenance of mobility with or without a walking aid, having the ability to use public transportation to attend clinic visits, and scoring at least 27 on the Mini-Mental State Examination. Exclusion criteria include supplemental vitamin D use exceeding 800 IU per day and unwillingness to discontinue additional calcium and vitamin D supplementation, current cancer, malabsorption syndrome, heavy alcohol consumption, uncontrolled hypocalcemia, severe visual or hearing impairment, use of medications affecting calcium metabolism, diseases causing hypercalcemia, planned travel to sunny locations for longer than 2 months per year, maximum calcium supplement dose of 250 mg/day, use of medications affecting serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) level, body mass index ≥ 40, diseases predisposing to falls, hypercalcemia, kidney disease with creatinine clearance < 15, or kidney stone within 10 years prior to enrollment.

Intervention. Participants were randomized to receive either monthly supplementation of 24,000 IU of vitamin D3 per month (low-dose group), 60,000 IU of vitamin D3 once per month (high-dose group), or 24,000 IU of vitamin D3 plus 300 µg of calcifediol once per month. It was hypothesized that higher monthly doses of vitamin D or in combination with calcifediol, which is a liver metabolite approximately 2 to 3 times more potent than vitamin D3, will increase levels of 25(OH)D and reduce the risk of functional decline.

Main outcome measures. Lower extremity function using the Short Physical Performance Battery and 25(OH)D levels at 6 and 12 months. Study nurses called participants monthly to assess falls, adverse events, and adherence to study medications.

Main results. A total of 200 participants were enrolled. Average age was 78 years (SD = 5) and 67% were female; all had a history of falls in the previous year and average baseline 25(OH)D levels ranged from 18.4 to 20.9 ng/mL in the three groups. Adherence to the study medication exceeded 94% throughout the study trial in all treatment groups.

At 6 and 12 months, 25(OH)D levels increased by an average of 12.7 and 11.7 ng/mL in the low-dose group, an average of 18.3 and 19.2 ng/mL in the high-dose group, and an average of 27.6 and 25.8 ng/mL in the calcifediol-added group. The mean changes in physical performance score indicating lower extremity function did not differ significantly among treatment groups (P = 0.26), but for one measure—the 5 successive chair stands—the 2 high-dose groups had less improvement when compared with the low-dose group. At 12 months, 66.9% of the high-dose group and 66.1% in the group with calcifediol fell during the study period, which was more than the low-dose group (47.9%, P = 0.048). The mean number of falls was also higher among the high-dose and calcifediol groups when compared with the low-dose group.

Conclusion. Higher doses of vitamin D were not better than lower doses of vitamin D in improving lower extremity function and were associated with higher risk of falls.

Commentary

Vitamin D deficiency is common among older adults and is associated with sarcopenia, functional decline, falls, and fractures [1,2]. Prior meta-analysis has supported that supplementation with vitamin D may lead to improved outcomes in fracture prevention [3]. However, the US Preventive Services Task Force, using more recent evidence reviews and an updated meta-analysis [4], found evidence lacking regarding the benefit of supplementation with vitamin D in community-dwelling postmenopausal women at doses > 400 IU, found no benefit in this group for doses ≤ 400, and found evidence lacking for supplementation in men or premenopausal women at any dose [5]. At the same time, the USPSTF also recommends exercise or physical therapy and vitamin D supplementation (800 IU daily) to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults ≥ 65 years at increased risk for falls [6]. This is consistent with the Institute of Medicine’s recommendation of 800 IU per day for older adults [7].

The current study attempted to elucidate the potential impact of high-dose vitamin D supplementation, hypothesizing that higher doses will achieve improvement in vitamin D levels and better outcomes in terms of lower extremity function and falls. However, the investigators found that rather than lowering risk of falls, higher-dose vitamin D was associated with elevated risk of falls without the benefit of improving lower extremity function. This is not the first study that has demonstrated that higher doses of vitamin D supplementation may be associated with harm. A prior randomized controlled trial utilizing a different dosing strategy of annual high- dose vitamin D supplementation also found that higher doses were associated with increased risks of falls [8]. Nonetheless, it helps support the notion that in vitamin D supplementation, more is not necessarily better.

The study is not without its drawbacks. The sample size was relatively small and the trial may have been underpowered to detect whether there may be certain patients for whom high-dose vitamin D supplementation may have a role. Also, the study was based in Zurich, which has a relatively uniform population, and study results may not be generalizable to populations in other countries.

Applications for Clinical Practice

The study lends support to the current recommendation of the Institute of Medicine—800 IU a day—for fall prevention, which is equivalent in dose to the 24,000 IU per month utilized in the trial. One of the questions not answered by the study is whether high-dose supplementation for adults who have severe deficiency in vitamin D is beneficial or harmful when compared with lower-dose supplementation. In clinical practice, clinicians often check an initial level of vitamin D and aim for a target level with supplementation. Among those patients with extremely low baseline levels, a lower-dose regimen of 800 IU a day may not yield a normalized level of vitamin D. Further studies are needed to elucidate whether there may be a role for higher-dose supplementation in these individuals. Nonetheless, it is clear that the current evidence does not support the routine use of high-dose vitamin D supplementation; it does not lead to better lower extremity function and may cause harm.

—William Hung, MD, MPH

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the effectiveness of high-dose vitamin D versus low-dose vitamin D in reducing the risk of functional decline in older adults.

Design. Double-blind randomized controlled trial.

Setting and participants. This single-center study was conducted at the University of Zurich. Home-dwelling adults aged 70 and over were recruited through newspaper advertisement in Zurich from December 2009 to May 2010. Inclusion criteria included maintenance of mobility with or without a walking aid, having the ability to use public transportation to attend clinic visits, and scoring at least 27 on the Mini-Mental State Examination. Exclusion criteria include supplemental vitamin D use exceeding 800 IU per day and unwillingness to discontinue additional calcium and vitamin D supplementation, current cancer, malabsorption syndrome, heavy alcohol consumption, uncontrolled hypocalcemia, severe visual or hearing impairment, use of medications affecting calcium metabolism, diseases causing hypercalcemia, planned travel to sunny locations for longer than 2 months per year, maximum calcium supplement dose of 250 mg/day, use of medications affecting serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) level, body mass index ≥ 40, diseases predisposing to falls, hypercalcemia, kidney disease with creatinine clearance < 15, or kidney stone within 10 years prior to enrollment.

Intervention. Participants were randomized to receive either monthly supplementation of 24,000 IU of vitamin D3 per month (low-dose group), 60,000 IU of vitamin D3 once per month (high-dose group), or 24,000 IU of vitamin D3 plus 300 µg of calcifediol once per month. It was hypothesized that higher monthly doses of vitamin D or in combination with calcifediol, which is a liver metabolite approximately 2 to 3 times more potent than vitamin D3, will increase levels of 25(OH)D and reduce the risk of functional decline.

Main outcome measures. Lower extremity function using the Short Physical Performance Battery and 25(OH)D levels at 6 and 12 months. Study nurses called participants monthly to assess falls, adverse events, and adherence to study medications.

Main results. A total of 200 participants were enrolled. Average age was 78 years (SD = 5) and 67% were female; all had a history of falls in the previous year and average baseline 25(OH)D levels ranged from 18.4 to 20.9 ng/mL in the three groups. Adherence to the study medication exceeded 94% throughout the study trial in all treatment groups.

At 6 and 12 months, 25(OH)D levels increased by an average of 12.7 and 11.7 ng/mL in the low-dose group, an average of 18.3 and 19.2 ng/mL in the high-dose group, and an average of 27.6 and 25.8 ng/mL in the calcifediol-added group. The mean changes in physical performance score indicating lower extremity function did not differ significantly among treatment groups (P = 0.26), but for one measure—the 5 successive chair stands—the 2 high-dose groups had less improvement when compared with the low-dose group. At 12 months, 66.9% of the high-dose group and 66.1% in the group with calcifediol fell during the study period, which was more than the low-dose group (47.9%, P = 0.048). The mean number of falls was also higher among the high-dose and calcifediol groups when compared with the low-dose group.

Conclusion. Higher doses of vitamin D were not better than lower doses of vitamin D in improving lower extremity function and were associated with higher risk of falls.

Commentary

Vitamin D deficiency is common among older adults and is associated with sarcopenia, functional decline, falls, and fractures [1,2]. Prior meta-analysis has supported that supplementation with vitamin D may lead to improved outcomes in fracture prevention [3]. However, the US Preventive Services Task Force, using more recent evidence reviews and an updated meta-analysis [4], found evidence lacking regarding the benefit of supplementation with vitamin D in community-dwelling postmenopausal women at doses > 400 IU, found no benefit in this group for doses ≤ 400, and found evidence lacking for supplementation in men or premenopausal women at any dose [5]. At the same time, the USPSTF also recommends exercise or physical therapy and vitamin D supplementation (800 IU daily) to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults ≥ 65 years at increased risk for falls [6]. This is consistent with the Institute of Medicine’s recommendation of 800 IU per day for older adults [7].

The current study attempted to elucidate the potential impact of high-dose vitamin D supplementation, hypothesizing that higher doses will achieve improvement in vitamin D levels and better outcomes in terms of lower extremity function and falls. However, the investigators found that rather than lowering risk of falls, higher-dose vitamin D was associated with elevated risk of falls without the benefit of improving lower extremity function. This is not the first study that has demonstrated that higher doses of vitamin D supplementation may be associated with harm. A prior randomized controlled trial utilizing a different dosing strategy of annual high- dose vitamin D supplementation also found that higher doses were associated with increased risks of falls [8]. Nonetheless, it helps support the notion that in vitamin D supplementation, more is not necessarily better.

The study is not without its drawbacks. The sample size was relatively small and the trial may have been underpowered to detect whether there may be certain patients for whom high-dose vitamin D supplementation may have a role. Also, the study was based in Zurich, which has a relatively uniform population, and study results may not be generalizable to populations in other countries.

Applications for Clinical Practice

The study lends support to the current recommendation of the Institute of Medicine—800 IU a day—for fall prevention, which is equivalent in dose to the 24,000 IU per month utilized in the trial. One of the questions not answered by the study is whether high-dose supplementation for adults who have severe deficiency in vitamin D is beneficial or harmful when compared with lower-dose supplementation. In clinical practice, clinicians often check an initial level of vitamin D and aim for a target level with supplementation. Among those patients with extremely low baseline levels, a lower-dose regimen of 800 IU a day may not yield a normalized level of vitamin D. Further studies are needed to elucidate whether there may be a role for higher-dose supplementation in these individuals. Nonetheless, it is clear that the current evidence does not support the routine use of high-dose vitamin D supplementation; it does not lead to better lower extremity function and may cause harm.

—William Hung, MD, MPH

1. Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P; Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels as determinants of loss of muscle strength and muscle mass (sarcopenia): the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:5766–72.

2. Cauley JA, Lacroix AZ, Wu L, et al. Serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D concentrations and risk for hip fractures. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:242–50.

3. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, et al. Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2005;293:2257–64.

4. Chung M, Lee J, Terasawa T, et al. Vitamin D with or without calcium supplementation for prevention of cancer and fractures: an updated meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:827–38.

5. Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:691–6.

6. Moyer VA et al. Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults: U.S. Prevention Services Task Force Recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:197–204.

7. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

8. Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:1815.

1. Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P; Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels as determinants of loss of muscle strength and muscle mass (sarcopenia): the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:5766–72.

2. Cauley JA, Lacroix AZ, Wu L, et al. Serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D concentrations and risk for hip fractures. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:242–50.

3. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, et al. Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2005;293:2257–64.

4. Chung M, Lee J, Terasawa T, et al. Vitamin D with or without calcium supplementation for prevention of cancer and fractures: an updated meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:827–38.

5. Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:691–6.

6. Moyer VA et al. Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults: U.S. Prevention Services Task Force Recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:197–204.

7. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

8. Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:1815.

The Role of Health Literacy and Patient Activation in Predicting Patient Health Information Seeking and Sharing

Study Overview

Objective. To assess how patients look for patient-obtained medication information (POMI) to prepare for a clinical appointment, whether they share those findings with their provider, and how health literacy and patient activation relate to a patient’s perception of the physician’s reaction to POMI.

Design. Cross-sectional survey-based study.

Setting and participants. The study took place over 1 week at 2 academic medical centers located in Las Vegas, Nevada, and Washington, DC. At a central waiting area at each facility, patients aged 18 and older waiting for their clinical appointment were invited to complete a survey, either on a computer tablet or with paper and pencil, before and after their appointment.

Measures and analysis. The pre-survey included demographic measures (age, gender, education, and ethnicity), the reason for the visit (routine care, sick visit, follow-up after survey, and follow-up after emergency room visit), and an item to assess self-report of perceived general health (from poor to excellent). Health literacy was assessed by a self-report measure that included subscales for the 3 dimensions of health literacy: functional, communicative, and critical health literacy [1]; together, these capture the ability of patients to retain health knowledge, gather and communicate health concepts, and apply health information. Patient activation was scored using the Patient Activation Measure (13 Likert-style items, total scale range 0–100); patient activation combines a patient’s self-reported knowledge, skill, and confidence for self-management of general health or a chronic condition [2]. Information seeking was measured by time spent (did not look for information, 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, or more than 3 hours), and information channels used to look for POMI (eg, magazines/newspapers, internet website or search engine) were presented dichotomously (yes/no).

The post-survey first asked whether the participant shared information with their provider (yes/no). If the participant said yes, 4 items assessed their perception of the provider’s response, including amount of time spent discussing POMI, how seriously the provider considered the information, and overall reaction (scored as a mean, each item measured from 1–5, with 5 indicating the most positive reactions). For hypothesis testing, logistic regression models were used to test the effects of the independent variables. To explore the relationship between health literacy/patient activation and physician response, correlations were calculated.

Main results. Over 400 patients were asked to participate, and of these a total of 243 (60.75%) patients were eligible, consented, and completed surveys. Participants were predominantly white (57.6%), female (63%), had some college education or higher (80.2%), and had a clinical appointment for routine care (69.3%). The mean age was 47.04 years (SD, 15.78), the mean health status was 3.20 (SD, 0.94), and the mean Patient Activation Measure was 72.43 (SD, 16.00).

More than half of participants (58.26%) who responded to the item about information seeking indicated seeking POMI prior to their clinical appointment. Of these, the majority (88.7%) reported using the internet, particularly WebMD, as an information channel. Significant predictors of information seeking included age (P = 0.01, OR = 0.973), communicative health literacy (P = 0.01, or = 1.975), and critical health literacy (P = 0.05, OR = 1.518). Lower age, higher communicative health literacy, and higher critical health literacy increased the likelihood of the patient seeking POMI prior to the clinical appointment. Other assessed predictors were not significant, including gender, functional health literacy, patient activation, reason for visit, and reported health status.

58.2% of the 141 information-seeking patients talked to their health care provider about the information they found. However, no predictor variables included in a logistic regression analysis were significant, including age, gender, reason for visit, reported health status, functional health literacy, communicative health literacy, critical health literacy, and patient activation. For the research question (how do health literacy and patient activation relate to a patient’s perception of the physician’s reaction to POMI), the mean score on the 4-item measure was 4.08 (SD, 0.90), indicating a generally positive response; most reported the physician response was good or higher. Patient activation correlated positively with perceived physician response (r = 0.245, P = 0.03).

Conclusion. The lack of data to predict who will introduce POMI at the medical visit is disconcerting. Providers might consider directly asking or passively surveying what outside information sources the patient has engaged with, regardless of whether patient introduces the information or does not introduce it.

Commentary

Patient engagement plays an important role in health care [3]. Activated patients often have skills and confidence to engage in their health care and with their provider, which often contributes to better health outcomes and care experiences [2,4] as well as lower health care costs [5]. Health information is needed to make informed decisions, manage health, and practice healthy behaviors [6], and patients are increasingly taking an active role in seeking out medical or health information outside of the clinical encounter in order to make shared health decisions with their provider [7]. Indeed, one of the Healthy People 2020 goals is to “Use health communication strategies and health information technology to improve population health outcomes and health care quality, and to achieve health equity” [8].

However, seeking POMI requires health literacy skills and supportive relationships, particularly when navigating the many channels and complexities of publicly available health information [8]. This is especially true on the internet, where there is often varying accuracy and clarity of information presented. According to 2011 data from the Pew Research Center [9], 74% of adults in the United States use the internet, and of those adults 80% have looked online for health information; 34% have read another person’s commentary or experience about health or medical issues on an online news group, website, or blog; 25% have watched an online video about health or medical issues; and 24% have consulted online reviews of particular drugs or medical treatments.

A general strength of this study was the cross-sectional design, which allowed for surveying patients around attitudes, motivations, and behaviors immediately before and after their clinical encounter. According to the authors, this study design was aimed to extend knowledge around information seeking and provider discussions that have occurred distally and relied on patient long-term recall. Additionally, this study surveyed a variety of patients (not limited to either primary or specialist appointments) at 2 different academic medical centers, and gave patients a choice to either take the survey on a computer tablet or traditional paper and pencil. Further, the authors assessed the reliability of scales used and included a number of predictor variables in the logistic regression models for hypothesis testing.

The authors acknowledged several limitations, including the use of convenience sampling and self-reported data with volunteer participants, which can result in self-selection bias and social desirability bias. As study participants were self-selecting, low health literacy patients may have been more likely to not volunteer to take the survey, which might explain the relatively high mean scores on the health literacy measures. Further, participants were mostly white, female, college-educated, health literate, and scheduled for a routine visit, which limits the generalizability of the study findings and the ability to identify significant predictors.