User login

Subgroup benefits from long-term DAPT

Photo courtesy of AstraZeneca

CHICAGO—Long-term use of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) can benefit patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) and peripheral artery disease (PAD), according to data presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 65th Annual Scientific Session.

The data were from a subanalysis of the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial, in which researchers evaluated long-term use of aspirin, with or without the antiplatelet agent ticagrelor, in patients with a history of MI and at least 1 additional risk factor for thrombotic cardiovascular (CV) events.

The analysis suggested that, in stable patients with a history of MI, concomitant PAD is associated with a higher risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE).

However, long-term DAPT with ticagrelor and aspirin can reduce the incidence of MACE in these patients, when compared to aspirin plus a placebo.

These results were presented as abstract 907-04 and simultaneously published in the Journal of American College of Cardiology. The trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company developing ticagrelor.

Patients in the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial were randomized to receive aspirin plus twice-daily doses of ticagrelor at 90 mg, ticagrelor at 60 mg, or placebo.

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was the incidence of MACE, which was defined as a composite of CV death, MI, or stroke.

The subanalysis showed that the 1143 patients with a prior MI and PAD had a higher incidence of MACE at 3 years than patients without PAD—19.3% and 8.4%, respectively (P<0.001).

The increased risk of MACE in patients with PAD persisted after the researchers adjusted for differences in patient characteristics at baseline. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.60 (95% CI 1.20-2.13, P=0.0013).

Patients with PAD had a higher risk of CV death (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.16-2.94, P=0.0102), stroke (HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.26–4.25, P=0.0071), and mortality (HR 2.05, 95% CI 1.43-2.94, P<0.001) than patients without PAD.

Patients who received DAPT (ticagrelor at either dose plus aspirin) had a lower risk of MACE at 3 years than patients who received placebo plus aspirin. This was true for patients with PAD (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.55-1.01) and without it (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.77-0.96, P-interaction=0.41).

However, because of their higher absolute risk of MACE, patients with PAD had a greater absolute risk reduction (4.1%) than patients without PAD.

The risk of TIMI major bleeding was not significantly higher in patients with PAD than in those without it (HR 1.57, 95% CI 0.47-5.22, P=0.46).

For patients with PAD, TIMI major bleeding occurred more frequently with ticagrelor at 90 mg plus aspirin than with placebo plus aspirin (HR 1.46, 95% CI 0.39-5.43, P=0.57) and with ticagrelor at 60 mg plus aspirin than with placebo plus aspirin (HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.29-4.70, P=0.82), though the differences were not significant.

“Patients with prior MI and PAD are at further heightened risk of ischemic events relative to patients with prior MI and no PAD, even when accounting for other risk factors,” said study investigator Marc Bonaca, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Because of their heightened ischemic risk, patients in the subgroup analysis with a prior MI and PAD appear to have a higher absolute risk reduction with ticagrelor than those without. These findings may be helpful to clinicians in identifying patients with prior MI who they feel could benefit from prolonged therapy with ticagrelor.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of AstraZeneca

CHICAGO—Long-term use of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) can benefit patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) and peripheral artery disease (PAD), according to data presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 65th Annual Scientific Session.

The data were from a subanalysis of the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial, in which researchers evaluated long-term use of aspirin, with or without the antiplatelet agent ticagrelor, in patients with a history of MI and at least 1 additional risk factor for thrombotic cardiovascular (CV) events.

The analysis suggested that, in stable patients with a history of MI, concomitant PAD is associated with a higher risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE).

However, long-term DAPT with ticagrelor and aspirin can reduce the incidence of MACE in these patients, when compared to aspirin plus a placebo.

These results were presented as abstract 907-04 and simultaneously published in the Journal of American College of Cardiology. The trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company developing ticagrelor.

Patients in the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial were randomized to receive aspirin plus twice-daily doses of ticagrelor at 90 mg, ticagrelor at 60 mg, or placebo.

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was the incidence of MACE, which was defined as a composite of CV death, MI, or stroke.

The subanalysis showed that the 1143 patients with a prior MI and PAD had a higher incidence of MACE at 3 years than patients without PAD—19.3% and 8.4%, respectively (P<0.001).

The increased risk of MACE in patients with PAD persisted after the researchers adjusted for differences in patient characteristics at baseline. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.60 (95% CI 1.20-2.13, P=0.0013).

Patients with PAD had a higher risk of CV death (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.16-2.94, P=0.0102), stroke (HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.26–4.25, P=0.0071), and mortality (HR 2.05, 95% CI 1.43-2.94, P<0.001) than patients without PAD.

Patients who received DAPT (ticagrelor at either dose plus aspirin) had a lower risk of MACE at 3 years than patients who received placebo plus aspirin. This was true for patients with PAD (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.55-1.01) and without it (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.77-0.96, P-interaction=0.41).

However, because of their higher absolute risk of MACE, patients with PAD had a greater absolute risk reduction (4.1%) than patients without PAD.

The risk of TIMI major bleeding was not significantly higher in patients with PAD than in those without it (HR 1.57, 95% CI 0.47-5.22, P=0.46).

For patients with PAD, TIMI major bleeding occurred more frequently with ticagrelor at 90 mg plus aspirin than with placebo plus aspirin (HR 1.46, 95% CI 0.39-5.43, P=0.57) and with ticagrelor at 60 mg plus aspirin than with placebo plus aspirin (HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.29-4.70, P=0.82), though the differences were not significant.

“Patients with prior MI and PAD are at further heightened risk of ischemic events relative to patients with prior MI and no PAD, even when accounting for other risk factors,” said study investigator Marc Bonaca, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Because of their heightened ischemic risk, patients in the subgroup analysis with a prior MI and PAD appear to have a higher absolute risk reduction with ticagrelor than those without. These findings may be helpful to clinicians in identifying patients with prior MI who they feel could benefit from prolonged therapy with ticagrelor.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of AstraZeneca

CHICAGO—Long-term use of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) can benefit patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) and peripheral artery disease (PAD), according to data presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 65th Annual Scientific Session.

The data were from a subanalysis of the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial, in which researchers evaluated long-term use of aspirin, with or without the antiplatelet agent ticagrelor, in patients with a history of MI and at least 1 additional risk factor for thrombotic cardiovascular (CV) events.

The analysis suggested that, in stable patients with a history of MI, concomitant PAD is associated with a higher risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE).

However, long-term DAPT with ticagrelor and aspirin can reduce the incidence of MACE in these patients, when compared to aspirin plus a placebo.

These results were presented as abstract 907-04 and simultaneously published in the Journal of American College of Cardiology. The trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company developing ticagrelor.

Patients in the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial were randomized to receive aspirin plus twice-daily doses of ticagrelor at 90 mg, ticagrelor at 60 mg, or placebo.

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was the incidence of MACE, which was defined as a composite of CV death, MI, or stroke.

The subanalysis showed that the 1143 patients with a prior MI and PAD had a higher incidence of MACE at 3 years than patients without PAD—19.3% and 8.4%, respectively (P<0.001).

The increased risk of MACE in patients with PAD persisted after the researchers adjusted for differences in patient characteristics at baseline. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.60 (95% CI 1.20-2.13, P=0.0013).

Patients with PAD had a higher risk of CV death (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.16-2.94, P=0.0102), stroke (HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.26–4.25, P=0.0071), and mortality (HR 2.05, 95% CI 1.43-2.94, P<0.001) than patients without PAD.

Patients who received DAPT (ticagrelor at either dose plus aspirin) had a lower risk of MACE at 3 years than patients who received placebo plus aspirin. This was true for patients with PAD (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.55-1.01) and without it (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.77-0.96, P-interaction=0.41).

However, because of their higher absolute risk of MACE, patients with PAD had a greater absolute risk reduction (4.1%) than patients without PAD.

The risk of TIMI major bleeding was not significantly higher in patients with PAD than in those without it (HR 1.57, 95% CI 0.47-5.22, P=0.46).

For patients with PAD, TIMI major bleeding occurred more frequently with ticagrelor at 90 mg plus aspirin than with placebo plus aspirin (HR 1.46, 95% CI 0.39-5.43, P=0.57) and with ticagrelor at 60 mg plus aspirin than with placebo plus aspirin (HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.29-4.70, P=0.82), though the differences were not significant.

“Patients with prior MI and PAD are at further heightened risk of ischemic events relative to patients with prior MI and no PAD, even when accounting for other risk factors,” said study investigator Marc Bonaca, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Because of their heightened ischemic risk, patients in the subgroup analysis with a prior MI and PAD appear to have a higher absolute risk reduction with ticagrelor than those without. These findings may be helpful to clinicians in identifying patients with prior MI who they feel could benefit from prolonged therapy with ticagrelor.” ![]()

Combos produce similar 10-year OS, PFS in HL

Photo by Bill Branson

Long-term results of the HD2000 trial reveal similar survival rates in patients with previously untreated, aggressive Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who received 3 different combination treatment regimens.

At 10 years of follow-up, there was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS) whether patients received ABVD, BEACOPP, or CEC.

However, patients who received ABVD were significantly less likely than those who received BEACOPP or CEC to develop second malignancies.

Francesco Merli, MD, of Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) in Italy, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The trial enrolled 307 patients with advanced-stage HL. Patients were randomized to receive 1 of 3 treatment regimens:

- Six cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine)

- Four escalated plus 2 standard cycles of BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone)

- Six cycles of CEC (cyclophosphamide, lomustine, vindesine, melphalan, prednisone, epidoxorubicin, vincristine, procarbazine, vinblastine, and bleomycin).

Some patients also received radiotherapy, but there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients receiving radiotherapy across the treatment arms—46% in the ABVD arm, 44% in the BEACOPP arm, and 43% in the CEC arm (P=0.871).

Results

At the end of all therapy, the complete response rate was 84% with ABVD, 91% with BEACOPP, and 83% with CEC.

There were 84 patients who did not achieve a complete response, and salvage data were available for 73 of these patients. Three patients (4%) died before salvage therapy could begin, 26 (36%) received conventional chemotherapy, 40 (55%) received a hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and 4 (5%) received radiotherapy.

The median follow-up was 120 months (range, 4 to 169 months), and 295 patients were evaluable.

In a previous analysis, at a median follow-up of 42 months, patients who received BEACOPP had superior PFS compared to patients who received ABVD.

However, in the current analysis, there was no significant difference in PFS between the 3 treatment arms. The 10-year PFS was 69% in the ABVD arm, 75% in the BEACOPP arm, and 76% in the CEC arm (P=0.471).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in OS between the treatment arms. The 10-year OS was 85% in the ABVD arm, 84% in the BEACOPP arm, and 86% in the CEC arm (P=0.892).

There were a total of 13 second malignancies—1 in the ABVD arm and 6 each in the BEACOPP and CEC arms.

The cumulative risk of developing a second malignancy at 10 years was 0.9% in the ABVD arm, 6.6% in the BEACOPP arm, and 6% in the CEC arm. So the risk with either BEACOPP or CEC was significantly higher than with ABVD (P=0.027 and 0.02, respectively).

The researchers said these results suggest BEACOPP provides better disease control than ABVD, but this benefit is counterbalanced by a higher rate of late major events with BEACOPP, particularly second malignancies, which resulted in patient deaths.

So the team concluded that BEACOPP is a viable treatment option for advanced HL, but it should not be considered the standard for all patients because 70% of these patients may be cured with ABVD and limited radiotherapy. A careful assessment of the risk-benefit ratio of the initial treatment choice is warranted. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Long-term results of the HD2000 trial reveal similar survival rates in patients with previously untreated, aggressive Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who received 3 different combination treatment regimens.

At 10 years of follow-up, there was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS) whether patients received ABVD, BEACOPP, or CEC.

However, patients who received ABVD were significantly less likely than those who received BEACOPP or CEC to develop second malignancies.

Francesco Merli, MD, of Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) in Italy, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The trial enrolled 307 patients with advanced-stage HL. Patients were randomized to receive 1 of 3 treatment regimens:

- Six cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine)

- Four escalated plus 2 standard cycles of BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone)

- Six cycles of CEC (cyclophosphamide, lomustine, vindesine, melphalan, prednisone, epidoxorubicin, vincristine, procarbazine, vinblastine, and bleomycin).

Some patients also received radiotherapy, but there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients receiving radiotherapy across the treatment arms—46% in the ABVD arm, 44% in the BEACOPP arm, and 43% in the CEC arm (P=0.871).

Results

At the end of all therapy, the complete response rate was 84% with ABVD, 91% with BEACOPP, and 83% with CEC.

There were 84 patients who did not achieve a complete response, and salvage data were available for 73 of these patients. Three patients (4%) died before salvage therapy could begin, 26 (36%) received conventional chemotherapy, 40 (55%) received a hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and 4 (5%) received radiotherapy.

The median follow-up was 120 months (range, 4 to 169 months), and 295 patients were evaluable.

In a previous analysis, at a median follow-up of 42 months, patients who received BEACOPP had superior PFS compared to patients who received ABVD.

However, in the current analysis, there was no significant difference in PFS between the 3 treatment arms. The 10-year PFS was 69% in the ABVD arm, 75% in the BEACOPP arm, and 76% in the CEC arm (P=0.471).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in OS between the treatment arms. The 10-year OS was 85% in the ABVD arm, 84% in the BEACOPP arm, and 86% in the CEC arm (P=0.892).

There were a total of 13 second malignancies—1 in the ABVD arm and 6 each in the BEACOPP and CEC arms.

The cumulative risk of developing a second malignancy at 10 years was 0.9% in the ABVD arm, 6.6% in the BEACOPP arm, and 6% in the CEC arm. So the risk with either BEACOPP or CEC was significantly higher than with ABVD (P=0.027 and 0.02, respectively).

The researchers said these results suggest BEACOPP provides better disease control than ABVD, but this benefit is counterbalanced by a higher rate of late major events with BEACOPP, particularly second malignancies, which resulted in patient deaths.

So the team concluded that BEACOPP is a viable treatment option for advanced HL, but it should not be considered the standard for all patients because 70% of these patients may be cured with ABVD and limited radiotherapy. A careful assessment of the risk-benefit ratio of the initial treatment choice is warranted. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Long-term results of the HD2000 trial reveal similar survival rates in patients with previously untreated, aggressive Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who received 3 different combination treatment regimens.

At 10 years of follow-up, there was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS) whether patients received ABVD, BEACOPP, or CEC.

However, patients who received ABVD were significantly less likely than those who received BEACOPP or CEC to develop second malignancies.

Francesco Merli, MD, of Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) in Italy, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The trial enrolled 307 patients with advanced-stage HL. Patients were randomized to receive 1 of 3 treatment regimens:

- Six cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine)

- Four escalated plus 2 standard cycles of BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone)

- Six cycles of CEC (cyclophosphamide, lomustine, vindesine, melphalan, prednisone, epidoxorubicin, vincristine, procarbazine, vinblastine, and bleomycin).

Some patients also received radiotherapy, but there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients receiving radiotherapy across the treatment arms—46% in the ABVD arm, 44% in the BEACOPP arm, and 43% in the CEC arm (P=0.871).

Results

At the end of all therapy, the complete response rate was 84% with ABVD, 91% with BEACOPP, and 83% with CEC.

There were 84 patients who did not achieve a complete response, and salvage data were available for 73 of these patients. Three patients (4%) died before salvage therapy could begin, 26 (36%) received conventional chemotherapy, 40 (55%) received a hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and 4 (5%) received radiotherapy.

The median follow-up was 120 months (range, 4 to 169 months), and 295 patients were evaluable.

In a previous analysis, at a median follow-up of 42 months, patients who received BEACOPP had superior PFS compared to patients who received ABVD.

However, in the current analysis, there was no significant difference in PFS between the 3 treatment arms. The 10-year PFS was 69% in the ABVD arm, 75% in the BEACOPP arm, and 76% in the CEC arm (P=0.471).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in OS between the treatment arms. The 10-year OS was 85% in the ABVD arm, 84% in the BEACOPP arm, and 86% in the CEC arm (P=0.892).

There were a total of 13 second malignancies—1 in the ABVD arm and 6 each in the BEACOPP and CEC arms.

The cumulative risk of developing a second malignancy at 10 years was 0.9% in the ABVD arm, 6.6% in the BEACOPP arm, and 6% in the CEC arm. So the risk with either BEACOPP or CEC was significantly higher than with ABVD (P=0.027 and 0.02, respectively).

The researchers said these results suggest BEACOPP provides better disease control than ABVD, but this benefit is counterbalanced by a higher rate of late major events with BEACOPP, particularly second malignancies, which resulted in patient deaths.

So the team concluded that BEACOPP is a viable treatment option for advanced HL, but it should not be considered the standard for all patients because 70% of these patients may be cured with ABVD and limited radiotherapy. A careful assessment of the risk-benefit ratio of the initial treatment choice is warranted. ![]()

Drug can reverse anticoagulant effect in emergencies

Photo by Piotr Bodzek

CHICAGO—Updated results from the RE-VERSE AD trial suggest idarucizumab, a humanized antibody fragment, can reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in emergency settings.

In this ongoing phase 3 trial, idarucizumab has normalized diluted thrombin time (dTT) and ecarin clotting time (ECT) in a majority of patients with uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding and patients who required emergency surgery or an invasive procedure.

In addition, researchers said there have been no safety concerns related to idarucizumab in this trial.

These results were presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 65th Annual Scientific Session (abstract 1130M-05). The study was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that developed idarucizumab and dabigatran.

“The data from this new RE-VERSE AD interim analysis, of the first 123 patients, support earlier findings that show idarucizumab reverses the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran, including reversal in critically ill, high-risk patients in emergency care,” said Charles Pollack, MD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr Pollack and his colleagues presented data on 123 patients—66 with uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding complications (Group A) and 57 patients requiring emergency surgery or an invasive procedure (Group B).

All of these patients received 5 g of idarucizumab. The primary endpoint of the study is the degree to which idarucizumab reversed the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran within 4 hours, measured by dTT and ECT.

Overall, 94 patients were evaluable for dTT and 112 for ECT. So 97% of evaluable patients (91/94) achieved full reversal of dTT, and 87% (97/112) achieved full reversal of ECT.

Among evaluable patients in Group A (n=48), the median subjective investigator-reported time to cessation of bleeding was 9.8 hours. For 92% of patients (44/48), bleeding stopped within 72 hours of idarucizumab administration.

Among evaluable patients in Group B (n=52), the mean time to surgery was 1.7 hours after receiving idarucizumab. Normal hemostasis during surgery was reported in 92% of patients (48/52).

Thromboembolic events occurred in 5 patients after idarucizumab administration—1 each at 48 hours, 7 days, 9 days, 13 days, and 24 days. None of these patients were receiving antithrombotic therapy at the time of their event.

However, most patients in both groups restarted anticoagulation after receiving idarucizumab—47 of 66 patients in Group A and 49 of 57 patients in Group B.

There were a total of 26 deaths—13 in each group. All of the deaths appeared to be related to the original reason for emergency admission to the hospital and/or to comorbidities. ![]()

Photo by Piotr Bodzek

CHICAGO—Updated results from the RE-VERSE AD trial suggest idarucizumab, a humanized antibody fragment, can reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in emergency settings.

In this ongoing phase 3 trial, idarucizumab has normalized diluted thrombin time (dTT) and ecarin clotting time (ECT) in a majority of patients with uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding and patients who required emergency surgery or an invasive procedure.

In addition, researchers said there have been no safety concerns related to idarucizumab in this trial.

These results were presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 65th Annual Scientific Session (abstract 1130M-05). The study was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that developed idarucizumab and dabigatran.

“The data from this new RE-VERSE AD interim analysis, of the first 123 patients, support earlier findings that show idarucizumab reverses the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran, including reversal in critically ill, high-risk patients in emergency care,” said Charles Pollack, MD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr Pollack and his colleagues presented data on 123 patients—66 with uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding complications (Group A) and 57 patients requiring emergency surgery or an invasive procedure (Group B).

All of these patients received 5 g of idarucizumab. The primary endpoint of the study is the degree to which idarucizumab reversed the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran within 4 hours, measured by dTT and ECT.

Overall, 94 patients were evaluable for dTT and 112 for ECT. So 97% of evaluable patients (91/94) achieved full reversal of dTT, and 87% (97/112) achieved full reversal of ECT.

Among evaluable patients in Group A (n=48), the median subjective investigator-reported time to cessation of bleeding was 9.8 hours. For 92% of patients (44/48), bleeding stopped within 72 hours of idarucizumab administration.

Among evaluable patients in Group B (n=52), the mean time to surgery was 1.7 hours after receiving idarucizumab. Normal hemostasis during surgery was reported in 92% of patients (48/52).

Thromboembolic events occurred in 5 patients after idarucizumab administration—1 each at 48 hours, 7 days, 9 days, 13 days, and 24 days. None of these patients were receiving antithrombotic therapy at the time of their event.

However, most patients in both groups restarted anticoagulation after receiving idarucizumab—47 of 66 patients in Group A and 49 of 57 patients in Group B.

There were a total of 26 deaths—13 in each group. All of the deaths appeared to be related to the original reason for emergency admission to the hospital and/or to comorbidities. ![]()

Photo by Piotr Bodzek

CHICAGO—Updated results from the RE-VERSE AD trial suggest idarucizumab, a humanized antibody fragment, can reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in emergency settings.

In this ongoing phase 3 trial, idarucizumab has normalized diluted thrombin time (dTT) and ecarin clotting time (ECT) in a majority of patients with uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding and patients who required emergency surgery or an invasive procedure.

In addition, researchers said there have been no safety concerns related to idarucizumab in this trial.

These results were presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 65th Annual Scientific Session (abstract 1130M-05). The study was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that developed idarucizumab and dabigatran.

“The data from this new RE-VERSE AD interim analysis, of the first 123 patients, support earlier findings that show idarucizumab reverses the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran, including reversal in critically ill, high-risk patients in emergency care,” said Charles Pollack, MD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr Pollack and his colleagues presented data on 123 patients—66 with uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding complications (Group A) and 57 patients requiring emergency surgery or an invasive procedure (Group B).

All of these patients received 5 g of idarucizumab. The primary endpoint of the study is the degree to which idarucizumab reversed the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran within 4 hours, measured by dTT and ECT.

Overall, 94 patients were evaluable for dTT and 112 for ECT. So 97% of evaluable patients (91/94) achieved full reversal of dTT, and 87% (97/112) achieved full reversal of ECT.

Among evaluable patients in Group A (n=48), the median subjective investigator-reported time to cessation of bleeding was 9.8 hours. For 92% of patients (44/48), bleeding stopped within 72 hours of idarucizumab administration.

Among evaluable patients in Group B (n=52), the mean time to surgery was 1.7 hours after receiving idarucizumab. Normal hemostasis during surgery was reported in 92% of patients (48/52).

Thromboembolic events occurred in 5 patients after idarucizumab administration—1 each at 48 hours, 7 days, 9 days, 13 days, and 24 days. None of these patients were receiving antithrombotic therapy at the time of their event.

However, most patients in both groups restarted anticoagulation after receiving idarucizumab—47 of 66 patients in Group A and 49 of 57 patients in Group B.

There were a total of 26 deaths—13 in each group. All of the deaths appeared to be related to the original reason for emergency admission to the hospital and/or to comorbidities. ![]()

VIDEO: How to recognize and treat nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

PHILADELPHIA – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is on the rise worldwide, but many clinicians are unaware of how to recognize this potentially fatal condition, in part because it can be difficult to separate from common comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes.

In an interview at the Digestive Diseases: New Advances 2016 meeting, held by Global Academy for Medical Education and Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, Dr. Zobair M. Younossi, chairman of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital, discussed what clinicians should know in order to screen for and treat this disease.

Dr. Younossi said he is a consultant to Conatus Pharmaceuticals, Enterome Bioscience, and Gilead, and on the advisory boards of Janssen, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

PHILADELPHIA – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is on the rise worldwide, but many clinicians are unaware of how to recognize this potentially fatal condition, in part because it can be difficult to separate from common comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes.

In an interview at the Digestive Diseases: New Advances 2016 meeting, held by Global Academy for Medical Education and Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, Dr. Zobair M. Younossi, chairman of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital, discussed what clinicians should know in order to screen for and treat this disease.

Dr. Younossi said he is a consultant to Conatus Pharmaceuticals, Enterome Bioscience, and Gilead, and on the advisory boards of Janssen, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

PHILADELPHIA – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is on the rise worldwide, but many clinicians are unaware of how to recognize this potentially fatal condition, in part because it can be difficult to separate from common comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes.

In an interview at the Digestive Diseases: New Advances 2016 meeting, held by Global Academy for Medical Education and Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, Dr. Zobair M. Younossi, chairman of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital, discussed what clinicians should know in order to screen for and treat this disease.

Dr. Younossi said he is a consultant to Conatus Pharmaceuticals, Enterome Bioscience, and Gilead, and on the advisory boards of Janssen, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT DIGESTIVE DISEASES: NEW ADVANCES 2016

Adding chemo to radiation boosts survival from low-grade gliomas

Adding a chemotherapy combination to radiation therapy for initial treatment of low-grade gliomas significantly improved overall survival and progression-free survival, regardless of the tumor type, investigators report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Grade 2 glioma patients who received radiation plus the combination of procarbazine, lomustine (also called CCNU), and vincristine (PCV) had a longer median overall survival than those who received radiation alone (13.3 vs. 7.8 years; hazard ratio for death, 0.59; P = .003). Of those who received radiation plus chemotherapy, the progression-free survival rate at 10 years was 51%, compared with 21% for the group who received radiation alone, Dr. Jan Buckner and his colleagues report (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1344-55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500925).

“The magnitude of treatment benefit from combined chemotherapy plus radiation therapy is substantial, but the toxic effects are greater than those observed with radiation therapy alone,” wrote Dr. Buckner, professor of oncology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and associates. Patients who received radiation plus PCV had more toxic side effects from their therapy, though most effects were grade 1 and 2.

For this study, 254 patients were randomized, with 128 assigned to radiotherapy alone, and 126 assigned to radiotherapy plus PCV. A total of 126 patients in the radiotherapy arm were included in the analysis, with one patient not receiving the intervention and 14 patients lost to follow-up at some point during the 10 years of the study. In the radiotherapy plus PCV arm, 125 patients were eligible for evaluation, and all of those patients were included in the analysis. Twenty-six patients in this arm were lost to follow-up, and 72 patients discontinued the intervention in this arm (this figure included four patients who died).

Tumor types included in the study were grade 2 astrocytoma, oligoastrocytoma, or oligodendroglioma.

Patients were included if they were between 18 and 39 years of age and had received a subtotal resection or biopsy of their tumor, or if they were 40 years of age or older and had any resection or biopsy of their tumor. Exclusion criteria included previous radiation to the head or neck, any previous chemotherapy, significant pulmonary disease, and a 5-year history of other cancers except cervical cancer in situ and non-melanoma skin cancer. Tumors could not have spread to noncontiguous leptomeninges, and patients could not have gliomatosis cerebri. Patients had to have a Karnofsky performance score of 60 or higher, and a neurological function score of 3 or less.

Dr. Buckner and his collaborators also assessed tumors for IDH1 mutational status by performing immunostaining with the mutation-specific monoclonal antibody IDH1 R132H; appropriate tissue was available for testing in slightly less than half of the patients in each study arm. The mutation was present in 35/57 patients (61%) in the radiotherapy-only arm, and 36/56 patients (64%) in the radiotherapy plus PCV arm. Patients with oligodendroglioma were most likely to have IDH1 R132H mutations. Sample sizes were too small to determine the effect of other IDH mutations or co-deletion of chromosome arms 1p and 19q.

In multivariable analysis, the presence of the IDH1 R132H mutation was identified as an independent prognostic factor for better overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), regardless of the treatment administered. Those with the mutation still benefited significantly from receiving radiotherapy plus PCV rather than radiotherapy alone (P = .02 for OS, P less than .001 for PFS).

Exploratory analysis that broke down OS and PFS by cancer type showed that “the superiority of radiation therapy plus chemotherapy over radiation therapy alone was seen with all histologic diagnoses, although the difference did not reach significance among patients with astrocytoma,” wrote Dr. Buckner and his collaborators.

When all patients lost to follow-up in both groups were assessed as having died, the sensitivity analysis still showed benefit for radiotherapy plus PCV (HR for death, compared with radiotherapy alone, 0.72; P = .03).

The value of the long-term follow-up, wrote Dr. Buckner and his colleagues, was that “The separation of the progression-free survival curves of the two treatment groups did not begin until 2 to 3 years after randomization, although approximately 25% of the patients in each group had disease progression by then.”

Dr. Buckner and his collaborators emphasized that the patient-physician team should consider all factors in making treatment decisions, saying, “Patients and their physicians will have to weigh whether the longer survival justified the more toxic therapeutic approach.“

On Twitter @karioakes

Adding a chemotherapy combination to radiation therapy for initial treatment of low-grade gliomas significantly improved overall survival and progression-free survival, regardless of the tumor type, investigators report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Grade 2 glioma patients who received radiation plus the combination of procarbazine, lomustine (also called CCNU), and vincristine (PCV) had a longer median overall survival than those who received radiation alone (13.3 vs. 7.8 years; hazard ratio for death, 0.59; P = .003). Of those who received radiation plus chemotherapy, the progression-free survival rate at 10 years was 51%, compared with 21% for the group who received radiation alone, Dr. Jan Buckner and his colleagues report (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1344-55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500925).

“The magnitude of treatment benefit from combined chemotherapy plus radiation therapy is substantial, but the toxic effects are greater than those observed with radiation therapy alone,” wrote Dr. Buckner, professor of oncology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and associates. Patients who received radiation plus PCV had more toxic side effects from their therapy, though most effects were grade 1 and 2.

For this study, 254 patients were randomized, with 128 assigned to radiotherapy alone, and 126 assigned to radiotherapy plus PCV. A total of 126 patients in the radiotherapy arm were included in the analysis, with one patient not receiving the intervention and 14 patients lost to follow-up at some point during the 10 years of the study. In the radiotherapy plus PCV arm, 125 patients were eligible for evaluation, and all of those patients were included in the analysis. Twenty-six patients in this arm were lost to follow-up, and 72 patients discontinued the intervention in this arm (this figure included four patients who died).

Tumor types included in the study were grade 2 astrocytoma, oligoastrocytoma, or oligodendroglioma.

Patients were included if they were between 18 and 39 years of age and had received a subtotal resection or biopsy of their tumor, or if they were 40 years of age or older and had any resection or biopsy of their tumor. Exclusion criteria included previous radiation to the head or neck, any previous chemotherapy, significant pulmonary disease, and a 5-year history of other cancers except cervical cancer in situ and non-melanoma skin cancer. Tumors could not have spread to noncontiguous leptomeninges, and patients could not have gliomatosis cerebri. Patients had to have a Karnofsky performance score of 60 or higher, and a neurological function score of 3 or less.

Dr. Buckner and his collaborators also assessed tumors for IDH1 mutational status by performing immunostaining with the mutation-specific monoclonal antibody IDH1 R132H; appropriate tissue was available for testing in slightly less than half of the patients in each study arm. The mutation was present in 35/57 patients (61%) in the radiotherapy-only arm, and 36/56 patients (64%) in the radiotherapy plus PCV arm. Patients with oligodendroglioma were most likely to have IDH1 R132H mutations. Sample sizes were too small to determine the effect of other IDH mutations or co-deletion of chromosome arms 1p and 19q.

In multivariable analysis, the presence of the IDH1 R132H mutation was identified as an independent prognostic factor for better overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), regardless of the treatment administered. Those with the mutation still benefited significantly from receiving radiotherapy plus PCV rather than radiotherapy alone (P = .02 for OS, P less than .001 for PFS).

Exploratory analysis that broke down OS and PFS by cancer type showed that “the superiority of radiation therapy plus chemotherapy over radiation therapy alone was seen with all histologic diagnoses, although the difference did not reach significance among patients with astrocytoma,” wrote Dr. Buckner and his collaborators.

When all patients lost to follow-up in both groups were assessed as having died, the sensitivity analysis still showed benefit for radiotherapy plus PCV (HR for death, compared with radiotherapy alone, 0.72; P = .03).

The value of the long-term follow-up, wrote Dr. Buckner and his colleagues, was that “The separation of the progression-free survival curves of the two treatment groups did not begin until 2 to 3 years after randomization, although approximately 25% of the patients in each group had disease progression by then.”

Dr. Buckner and his collaborators emphasized that the patient-physician team should consider all factors in making treatment decisions, saying, “Patients and their physicians will have to weigh whether the longer survival justified the more toxic therapeutic approach.“

On Twitter @karioakes

Adding a chemotherapy combination to radiation therapy for initial treatment of low-grade gliomas significantly improved overall survival and progression-free survival, regardless of the tumor type, investigators report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Grade 2 glioma patients who received radiation plus the combination of procarbazine, lomustine (also called CCNU), and vincristine (PCV) had a longer median overall survival than those who received radiation alone (13.3 vs. 7.8 years; hazard ratio for death, 0.59; P = .003). Of those who received radiation plus chemotherapy, the progression-free survival rate at 10 years was 51%, compared with 21% for the group who received radiation alone, Dr. Jan Buckner and his colleagues report (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1344-55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500925).

“The magnitude of treatment benefit from combined chemotherapy plus radiation therapy is substantial, but the toxic effects are greater than those observed with radiation therapy alone,” wrote Dr. Buckner, professor of oncology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and associates. Patients who received radiation plus PCV had more toxic side effects from their therapy, though most effects were grade 1 and 2.

For this study, 254 patients were randomized, with 128 assigned to radiotherapy alone, and 126 assigned to radiotherapy plus PCV. A total of 126 patients in the radiotherapy arm were included in the analysis, with one patient not receiving the intervention and 14 patients lost to follow-up at some point during the 10 years of the study. In the radiotherapy plus PCV arm, 125 patients were eligible for evaluation, and all of those patients were included in the analysis. Twenty-six patients in this arm were lost to follow-up, and 72 patients discontinued the intervention in this arm (this figure included four patients who died).

Tumor types included in the study were grade 2 astrocytoma, oligoastrocytoma, or oligodendroglioma.

Patients were included if they were between 18 and 39 years of age and had received a subtotal resection or biopsy of their tumor, or if they were 40 years of age or older and had any resection or biopsy of their tumor. Exclusion criteria included previous radiation to the head or neck, any previous chemotherapy, significant pulmonary disease, and a 5-year history of other cancers except cervical cancer in situ and non-melanoma skin cancer. Tumors could not have spread to noncontiguous leptomeninges, and patients could not have gliomatosis cerebri. Patients had to have a Karnofsky performance score of 60 or higher, and a neurological function score of 3 or less.

Dr. Buckner and his collaborators also assessed tumors for IDH1 mutational status by performing immunostaining with the mutation-specific monoclonal antibody IDH1 R132H; appropriate tissue was available for testing in slightly less than half of the patients in each study arm. The mutation was present in 35/57 patients (61%) in the radiotherapy-only arm, and 36/56 patients (64%) in the radiotherapy plus PCV arm. Patients with oligodendroglioma were most likely to have IDH1 R132H mutations. Sample sizes were too small to determine the effect of other IDH mutations or co-deletion of chromosome arms 1p and 19q.

In multivariable analysis, the presence of the IDH1 R132H mutation was identified as an independent prognostic factor for better overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), regardless of the treatment administered. Those with the mutation still benefited significantly from receiving radiotherapy plus PCV rather than radiotherapy alone (P = .02 for OS, P less than .001 for PFS).

Exploratory analysis that broke down OS and PFS by cancer type showed that “the superiority of radiation therapy plus chemotherapy over radiation therapy alone was seen with all histologic diagnoses, although the difference did not reach significance among patients with astrocytoma,” wrote Dr. Buckner and his collaborators.

When all patients lost to follow-up in both groups were assessed as having died, the sensitivity analysis still showed benefit for radiotherapy plus PCV (HR for death, compared with radiotherapy alone, 0.72; P = .03).

The value of the long-term follow-up, wrote Dr. Buckner and his colleagues, was that “The separation of the progression-free survival curves of the two treatment groups did not begin until 2 to 3 years after randomization, although approximately 25% of the patients in each group had disease progression by then.”

Dr. Buckner and his collaborators emphasized that the patient-physician team should consider all factors in making treatment decisions, saying, “Patients and their physicians will have to weigh whether the longer survival justified the more toxic therapeutic approach.“

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Adding chemotherapy to radiotherapy improved progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with low-grade glioma.

Major finding: Median overall survival was 13.3 years for those receiving radiotherapy plus chemotherapy, compared with 7.8 years for radiotherapy alone (hazard ratio for death, 0.59; P = .003).

Data source: Longitudinal study of 254 patients with grade 2 gliomas receiving radiation therapy alone or radiation therapy plus procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and did not receive funding from commercial sources. Dr. Bell and Dr. Chakravarti reported a planned patent application related to this work. Dr. Buckner, Dr. Gilbert, Dr. Mehta, and Dr. Suh reported support from pharmaceutical companies outside the scope of this study.

Morning cortisol rules out adrenal insufficiency

BOSTON – A random morning serum cortisol above 11.1 mcg/dL safely rules out adrenal insufficiency in both inpatients and outpatients, according to a review of 3,300 adrenal insufficiency work-ups at the Edinburgh Centre for Endocrinology and Diabetes.

The finding could help eliminate the cost and hassle of unnecessary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation tests; the investigators estimated that the cut point would eliminate almost half of them without any ill effects. “You can be very confident that patients aren’t insufficient if they are above that line,” with more than 99% sensitivity. If they are below it, “they may be normal, and they may be abnormal.” Below 1.8 mcg/dL, adrenal insufficiency is almost certain, but between the cutoffs, ACTH stimulation is necessary, said lead investigator Dr. Scott Mackenzie, a trainee at the center.

In short, “basal serum cortisol as a screening test ... offers a convenient and accessible means of identifying patients who require further assessment,” he said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Similar cut points have been suggested by previous studies, but the Scottish investigation is the first to validate its findings both inside and outside of the hospital.

The team arrived at the 11.1 mcg/dL morning cortisol cut point by comparing basal cortisol levels and synacthen results in 1,628 outpatients. They predefined a sensitivity of more than 99% for adrenal sufficiency to avoid missing anyone with true disease. The cut point’s predictive power was then validated in 875 outpatients and 797 inpatients. Morning basal cortisol levels proved superior to afternoon levels.

The investigators were thinking about cost-effectiveness, but they also wanted to increase screening. “We may be able to reduce the number of adrenal insufficiency cases we are missing because [primary care is] reluctant to send people to the clinic for synacthen tests” due to the cost and inconvenience. As with many locations in the United States, “our practice is to do [ACTH on] everyone.” If there was “a quick and easy 9 a.m. blood test” instead, it would help, Dr. Mackenzie said.

Adrenal insufficiency was on the differential for a wide variety of reasons, including hypogonadism, pituitary issues, prolactinemia, fatigue, hypoglycemia, postural hypotension, and hyponatremia. Most of the patients were middle aged, and they were about evenly split between men and women.

There was no outside funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

BOSTON – A random morning serum cortisol above 11.1 mcg/dL safely rules out adrenal insufficiency in both inpatients and outpatients, according to a review of 3,300 adrenal insufficiency work-ups at the Edinburgh Centre for Endocrinology and Diabetes.

The finding could help eliminate the cost and hassle of unnecessary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation tests; the investigators estimated that the cut point would eliminate almost half of them without any ill effects. “You can be very confident that patients aren’t insufficient if they are above that line,” with more than 99% sensitivity. If they are below it, “they may be normal, and they may be abnormal.” Below 1.8 mcg/dL, adrenal insufficiency is almost certain, but between the cutoffs, ACTH stimulation is necessary, said lead investigator Dr. Scott Mackenzie, a trainee at the center.

In short, “basal serum cortisol as a screening test ... offers a convenient and accessible means of identifying patients who require further assessment,” he said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Similar cut points have been suggested by previous studies, but the Scottish investigation is the first to validate its findings both inside and outside of the hospital.

The team arrived at the 11.1 mcg/dL morning cortisol cut point by comparing basal cortisol levels and synacthen results in 1,628 outpatients. They predefined a sensitivity of more than 99% for adrenal sufficiency to avoid missing anyone with true disease. The cut point’s predictive power was then validated in 875 outpatients and 797 inpatients. Morning basal cortisol levels proved superior to afternoon levels.

The investigators were thinking about cost-effectiveness, but they also wanted to increase screening. “We may be able to reduce the number of adrenal insufficiency cases we are missing because [primary care is] reluctant to send people to the clinic for synacthen tests” due to the cost and inconvenience. As with many locations in the United States, “our practice is to do [ACTH on] everyone.” If there was “a quick and easy 9 a.m. blood test” instead, it would help, Dr. Mackenzie said.

Adrenal insufficiency was on the differential for a wide variety of reasons, including hypogonadism, pituitary issues, prolactinemia, fatigue, hypoglycemia, postural hypotension, and hyponatremia. Most of the patients were middle aged, and they were about evenly split between men and women.

There was no outside funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

BOSTON – A random morning serum cortisol above 11.1 mcg/dL safely rules out adrenal insufficiency in both inpatients and outpatients, according to a review of 3,300 adrenal insufficiency work-ups at the Edinburgh Centre for Endocrinology and Diabetes.

The finding could help eliminate the cost and hassle of unnecessary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation tests; the investigators estimated that the cut point would eliminate almost half of them without any ill effects. “You can be very confident that patients aren’t insufficient if they are above that line,” with more than 99% sensitivity. If they are below it, “they may be normal, and they may be abnormal.” Below 1.8 mcg/dL, adrenal insufficiency is almost certain, but between the cutoffs, ACTH stimulation is necessary, said lead investigator Dr. Scott Mackenzie, a trainee at the center.

In short, “basal serum cortisol as a screening test ... offers a convenient and accessible means of identifying patients who require further assessment,” he said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Similar cut points have been suggested by previous studies, but the Scottish investigation is the first to validate its findings both inside and outside of the hospital.

The team arrived at the 11.1 mcg/dL morning cortisol cut point by comparing basal cortisol levels and synacthen results in 1,628 outpatients. They predefined a sensitivity of more than 99% for adrenal sufficiency to avoid missing anyone with true disease. The cut point’s predictive power was then validated in 875 outpatients and 797 inpatients. Morning basal cortisol levels proved superior to afternoon levels.

The investigators were thinking about cost-effectiveness, but they also wanted to increase screening. “We may be able to reduce the number of adrenal insufficiency cases we are missing because [primary care is] reluctant to send people to the clinic for synacthen tests” due to the cost and inconvenience. As with many locations in the United States, “our practice is to do [ACTH on] everyone.” If there was “a quick and easy 9 a.m. blood test” instead, it would help, Dr. Mackenzie said.

Adrenal insufficiency was on the differential for a wide variety of reasons, including hypogonadism, pituitary issues, prolactinemia, fatigue, hypoglycemia, postural hypotension, and hyponatremia. Most of the patients were middle aged, and they were about evenly split between men and women.

There was no outside funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

AT ENDO 2016

Key clinical point: Skip ACTH stimulation if morning serum cortisol is above 11.1 mcg/dL.

Major finding: A morning serum cortisol above 11.1 mcg/dL is a test of adrenal function with 99% sensitivity.

Data source: Review of 3,300 adrenal insufficiency work-ups.

Disclosures: There was no outside funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

Fetal malformation risk not increased after exposure to lamotrigine

A new analysis of registry data from European countries does not support a risk of orofacial cleft and clubfoot with exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy, in contrast to signals from previous studies of the antiepileptic drug.

First author Helen Dolk, Dr.P.H., professor of epidemiology and health services research and the head of the center for maternal, fetal, and infant research at the University of Ulster in Coleraine, Northern Ireland, and her colleagues analyzed data from 10.1 million births exposed to antiepileptic drugs including lamotrigine (Lamictal) as a monotherapy during the first trimester between 1995 and 2011. The births were recorded in 21 population-based registries from 16 European countries. The outcomes of interest were major congenital malformations in general, as well as orofacial clefts and clubfoot (Neurology. 2016 April 6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002540).

Assessment of all antiepileptic drug-exposed congenital malformation registrations revealed that 12% of pregnant registrants were exposed to lamotrigine monotherapy, with an additional 7% exposed to lamotrigine as part of polytherapy. A total of 77.1% of pregnant women exposed to lamotrigine monotherapy had records indicative of a diagnosis of epilepsy. The proportion of lamotrigine monotherapy exposures was observed to have increased over the study period, likely based on a movement away from the traditional use of valproate because of teratogenic concerns.

A total of 147 lamotrigine monotherapy-exposed babies with congenital malformations not attributable to chromosomal irregularities were identified from the total sample. The odds ratio for having a child with orofacial clefts after exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy was 1.31 (95% confidence interval, 0.73-2.33). Based on these data, the authors said they estimated exposure to lamotrigine would result in orofacial clefts in fewer than 1 in every 550 exposed babies.

The odds ratio for having a child with clubfoot after exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy was 1.83 (95% CI, 1.01-3.31). Although the study results confirmed the statistically significant signal for an overall excess of clubfoot risk found in a previous study conducted by this research team that analyzed births during 1995-2005, the investigators could not reproduce this result in an independent study population of 6.3 million births during 2005-2011(odds ratio, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.66-3.08). There were no significant differences in the risk for developing any other congenital malformations associated with lamotrigine monotherapy, the investigators said.

The authors said their results were in accord with those from several previous studies that did not detect an increased risk of orofacial clefts. In addition, they said statistically significant independent evidence of a clubfoot excess was not detected in the current study, despite findings from their previous study suggesting an increased risk.

The EUROCAT Central Database was funded by the EU Public Health Programme. GlaxoSmithKline, which markets lamotrigine, provided a grant for additional funding of this study. Dr. Dolk and her coauthors reported that their institutions received funding from GlaxoSmithKline for data or staff time contributed to this study.

A new analysis of registry data from European countries does not support a risk of orofacial cleft and clubfoot with exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy, in contrast to signals from previous studies of the antiepileptic drug.

First author Helen Dolk, Dr.P.H., professor of epidemiology and health services research and the head of the center for maternal, fetal, and infant research at the University of Ulster in Coleraine, Northern Ireland, and her colleagues analyzed data from 10.1 million births exposed to antiepileptic drugs including lamotrigine (Lamictal) as a monotherapy during the first trimester between 1995 and 2011. The births were recorded in 21 population-based registries from 16 European countries. The outcomes of interest were major congenital malformations in general, as well as orofacial clefts and clubfoot (Neurology. 2016 April 6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002540).

Assessment of all antiepileptic drug-exposed congenital malformation registrations revealed that 12% of pregnant registrants were exposed to lamotrigine monotherapy, with an additional 7% exposed to lamotrigine as part of polytherapy. A total of 77.1% of pregnant women exposed to lamotrigine monotherapy had records indicative of a diagnosis of epilepsy. The proportion of lamotrigine monotherapy exposures was observed to have increased over the study period, likely based on a movement away from the traditional use of valproate because of teratogenic concerns.

A total of 147 lamotrigine monotherapy-exposed babies with congenital malformations not attributable to chromosomal irregularities were identified from the total sample. The odds ratio for having a child with orofacial clefts after exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy was 1.31 (95% confidence interval, 0.73-2.33). Based on these data, the authors said they estimated exposure to lamotrigine would result in orofacial clefts in fewer than 1 in every 550 exposed babies.

The odds ratio for having a child with clubfoot after exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy was 1.83 (95% CI, 1.01-3.31). Although the study results confirmed the statistically significant signal for an overall excess of clubfoot risk found in a previous study conducted by this research team that analyzed births during 1995-2005, the investigators could not reproduce this result in an independent study population of 6.3 million births during 2005-2011(odds ratio, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.66-3.08). There were no significant differences in the risk for developing any other congenital malformations associated with lamotrigine monotherapy, the investigators said.

The authors said their results were in accord with those from several previous studies that did not detect an increased risk of orofacial clefts. In addition, they said statistically significant independent evidence of a clubfoot excess was not detected in the current study, despite findings from their previous study suggesting an increased risk.

The EUROCAT Central Database was funded by the EU Public Health Programme. GlaxoSmithKline, which markets lamotrigine, provided a grant for additional funding of this study. Dr. Dolk and her coauthors reported that their institutions received funding from GlaxoSmithKline for data or staff time contributed to this study.

A new analysis of registry data from European countries does not support a risk of orofacial cleft and clubfoot with exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy, in contrast to signals from previous studies of the antiepileptic drug.

First author Helen Dolk, Dr.P.H., professor of epidemiology and health services research and the head of the center for maternal, fetal, and infant research at the University of Ulster in Coleraine, Northern Ireland, and her colleagues analyzed data from 10.1 million births exposed to antiepileptic drugs including lamotrigine (Lamictal) as a monotherapy during the first trimester between 1995 and 2011. The births were recorded in 21 population-based registries from 16 European countries. The outcomes of interest were major congenital malformations in general, as well as orofacial clefts and clubfoot (Neurology. 2016 April 6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002540).

Assessment of all antiepileptic drug-exposed congenital malformation registrations revealed that 12% of pregnant registrants were exposed to lamotrigine monotherapy, with an additional 7% exposed to lamotrigine as part of polytherapy. A total of 77.1% of pregnant women exposed to lamotrigine monotherapy had records indicative of a diagnosis of epilepsy. The proportion of lamotrigine monotherapy exposures was observed to have increased over the study period, likely based on a movement away from the traditional use of valproate because of teratogenic concerns.

A total of 147 lamotrigine monotherapy-exposed babies with congenital malformations not attributable to chromosomal irregularities were identified from the total sample. The odds ratio for having a child with orofacial clefts after exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy was 1.31 (95% confidence interval, 0.73-2.33). Based on these data, the authors said they estimated exposure to lamotrigine would result in orofacial clefts in fewer than 1 in every 550 exposed babies.

The odds ratio for having a child with clubfoot after exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy was 1.83 (95% CI, 1.01-3.31). Although the study results confirmed the statistically significant signal for an overall excess of clubfoot risk found in a previous study conducted by this research team that analyzed births during 1995-2005, the investigators could not reproduce this result in an independent study population of 6.3 million births during 2005-2011(odds ratio, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.66-3.08). There were no significant differences in the risk for developing any other congenital malformations associated with lamotrigine monotherapy, the investigators said.

The authors said their results were in accord with those from several previous studies that did not detect an increased risk of orofacial clefts. In addition, they said statistically significant independent evidence of a clubfoot excess was not detected in the current study, despite findings from their previous study suggesting an increased risk.

The EUROCAT Central Database was funded by the EU Public Health Programme. GlaxoSmithKline, which markets lamotrigine, provided a grant for additional funding of this study. Dr. Dolk and her coauthors reported that their institutions received funding from GlaxoSmithKline for data or staff time contributed to this study.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point:Babies born to mothers exposed to lamotrigine monotherapy do not show evidence for an increased incidence of orofacial clefts or clubfoot.

Major finding: The odds ratios for having a child with orofacial clefts or clubfoot after exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy were 1.31 and 1.83, respectively.

Data source: A 16-year, observational study comparing the rate of lamotrigine exposure among births with orofacial clefts or clubfoot in 10.1 million births recorded in 21 population-based registries from 16 European countries.

Disclosures: The EUROCAT Central Database was funded by the EU Public Health Programme. GlaxoSmithKline, which markets lamotrigine, provided a grant for additional funding of this study. Dr. Dolk and her coauthors reported that their institutions received funding from GlaxoSmithKline for data or staff time contributed to this study.

Phase III dupilumab data show significant improvements in atopic dermatitis

Treatment with dupilumab resulted in significant clinical improvements in adults with inadequately controlled moderate to-severe atopic dermatitis, in two phase III studies evaluating the biologic agent, according to Regeneron and Sanofi.

The phase III results of the two 16-week studies, SOLO 1 and SOLO 2, in nearly 1,400 adults with baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scores of 3 (moderate disease) or 4 (severe), were announced by Regeneron and Sanofi. The companies are codeveloping dupilumab, which inhibits signaling of interleukin-4 and IL-13, “two key cytokines required for the T helper 2 (Th2) immune response,” according to Regeneron.

In the studies, patients were randomized to treatment with 300 mg subcutaneously of dupilumab once a week or every 2 weeks (after a 600-mg loading dose) or placebo, for 16 weeks.

At 16 weeks, significantly more of those in the two treatment groups achieved clearing or near clearing of skin lesions – a primary endpoint – compared with placebo: In SOLO 1 and SOLO 2, respectively, an IGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) was achieved by 37% and 36% of those treated with 300 mg weekly, and 38% and 36% of those treated every 2 weeks, compared with 10% and 8.5% of those on placebo (P less than .0001).

Improvement from baseline in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score in the SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 studies, respectively, were 72% and 69% of those treated with 300 mg weekly and 72% and 67% of those treated every 2 weeks, compared with 38% and 31% of those on placebo (P less than .0001).

The rates of adverse events ranged from 65% to 73% for those on dupilumab, and from 65% to 72% for those on placebo. The rates of serious adverse events were 1%-3% among those on dupilumab and 5%-6% for placebo; serious and severe infections were more common among those on placebo. Compared with placebo, injection site reactions were higher among those on dupilumab (10%-20% vs. 7%-8%). Conjunctivitis was more common among dupilumab-treated patients (7%-12% vs. 2% for placebo). One patient stopped treatment because of conjunctivitis.

The phase III results, which were announced in an April 1 press release, will be presented at a future medical meeting, and the companies plan to file for approval with the Food and Drug Administration in the third quarter of 2016.

Treatment with dupilumab resulted in significant clinical improvements in adults with inadequately controlled moderate to-severe atopic dermatitis, in two phase III studies evaluating the biologic agent, according to Regeneron and Sanofi.

The phase III results of the two 16-week studies, SOLO 1 and SOLO 2, in nearly 1,400 adults with baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scores of 3 (moderate disease) or 4 (severe), were announced by Regeneron and Sanofi. The companies are codeveloping dupilumab, which inhibits signaling of interleukin-4 and IL-13, “two key cytokines required for the T helper 2 (Th2) immune response,” according to Regeneron.

In the studies, patients were randomized to treatment with 300 mg subcutaneously of dupilumab once a week or every 2 weeks (after a 600-mg loading dose) or placebo, for 16 weeks.

At 16 weeks, significantly more of those in the two treatment groups achieved clearing or near clearing of skin lesions – a primary endpoint – compared with placebo: In SOLO 1 and SOLO 2, respectively, an IGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) was achieved by 37% and 36% of those treated with 300 mg weekly, and 38% and 36% of those treated every 2 weeks, compared with 10% and 8.5% of those on placebo (P less than .0001).

Improvement from baseline in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score in the SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 studies, respectively, were 72% and 69% of those treated with 300 mg weekly and 72% and 67% of those treated every 2 weeks, compared with 38% and 31% of those on placebo (P less than .0001).

The rates of adverse events ranged from 65% to 73% for those on dupilumab, and from 65% to 72% for those on placebo. The rates of serious adverse events were 1%-3% among those on dupilumab and 5%-6% for placebo; serious and severe infections were more common among those on placebo. Compared with placebo, injection site reactions were higher among those on dupilumab (10%-20% vs. 7%-8%). Conjunctivitis was more common among dupilumab-treated patients (7%-12% vs. 2% for placebo). One patient stopped treatment because of conjunctivitis.

The phase III results, which were announced in an April 1 press release, will be presented at a future medical meeting, and the companies plan to file for approval with the Food and Drug Administration in the third quarter of 2016.

Treatment with dupilumab resulted in significant clinical improvements in adults with inadequately controlled moderate to-severe atopic dermatitis, in two phase III studies evaluating the biologic agent, according to Regeneron and Sanofi.

The phase III results of the two 16-week studies, SOLO 1 and SOLO 2, in nearly 1,400 adults with baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scores of 3 (moderate disease) or 4 (severe), were announced by Regeneron and Sanofi. The companies are codeveloping dupilumab, which inhibits signaling of interleukin-4 and IL-13, “two key cytokines required for the T helper 2 (Th2) immune response,” according to Regeneron.

In the studies, patients were randomized to treatment with 300 mg subcutaneously of dupilumab once a week or every 2 weeks (after a 600-mg loading dose) or placebo, for 16 weeks.

At 16 weeks, significantly more of those in the two treatment groups achieved clearing or near clearing of skin lesions – a primary endpoint – compared with placebo: In SOLO 1 and SOLO 2, respectively, an IGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) was achieved by 37% and 36% of those treated with 300 mg weekly, and 38% and 36% of those treated every 2 weeks, compared with 10% and 8.5% of those on placebo (P less than .0001).

Improvement from baseline in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score in the SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 studies, respectively, were 72% and 69% of those treated with 300 mg weekly and 72% and 67% of those treated every 2 weeks, compared with 38% and 31% of those on placebo (P less than .0001).

The rates of adverse events ranged from 65% to 73% for those on dupilumab, and from 65% to 72% for those on placebo. The rates of serious adverse events were 1%-3% among those on dupilumab and 5%-6% for placebo; serious and severe infections were more common among those on placebo. Compared with placebo, injection site reactions were higher among those on dupilumab (10%-20% vs. 7%-8%). Conjunctivitis was more common among dupilumab-treated patients (7%-12% vs. 2% for placebo). One patient stopped treatment because of conjunctivitis.

The phase III results, which were announced in an April 1 press release, will be presented at a future medical meeting, and the companies plan to file for approval with the Food and Drug Administration in the third quarter of 2016.

Intralymphatic Histiocytosis Associated With an Orthopedic Metal Implant

To the Editor:

|

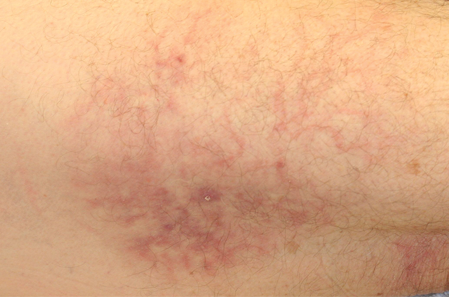

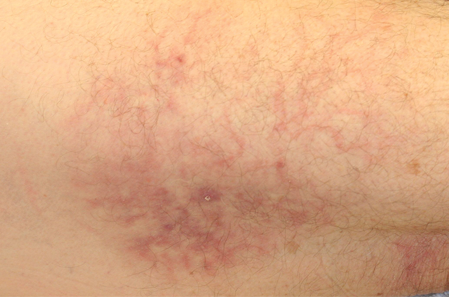

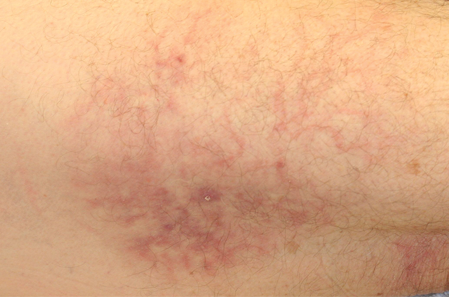

| Figure 1. A 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh. |

|

|

|

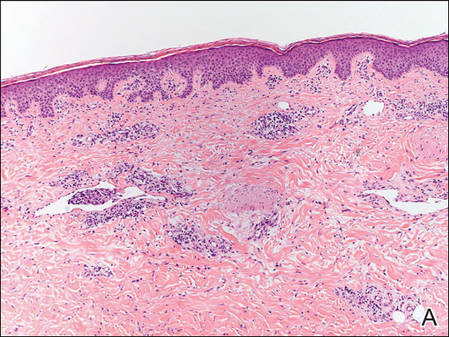

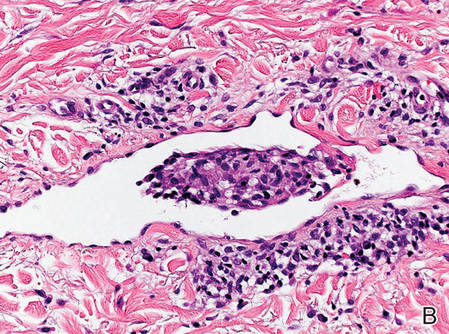

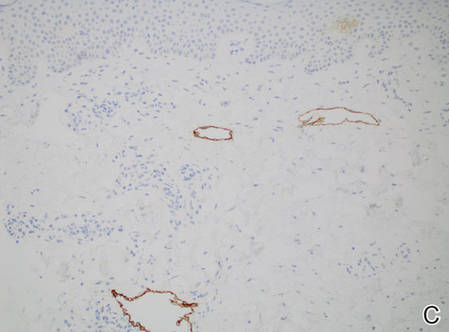

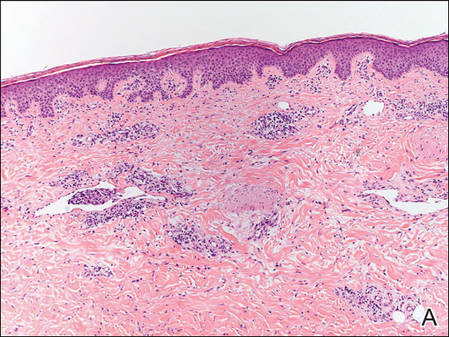

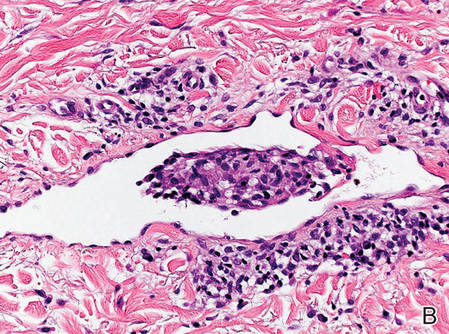

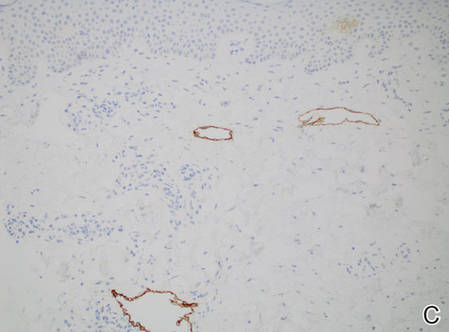

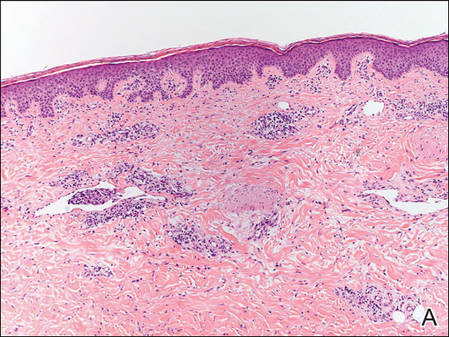

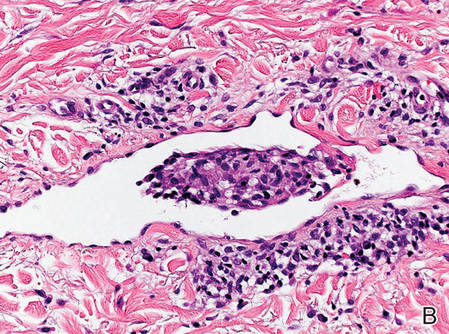

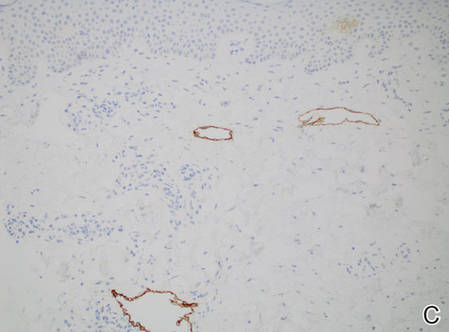

Figure 2. Histopathology revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis with adjacent features of chronic lymphedema (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) as well as a collection of histiocytes in a dilated lymphatic channel (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). D2-40 staining demonstrated ectatic lymphatic vessels in the upper dermins (C)(original magnification ×20).

|

A 70-year-old white man presented with an asymptomatic patch on the lateral aspect of the right thigh of 15 months’ duration. The patient believed the patch correlated with a hip replacement 3 years prior; however, it was 6 inches inferior to the incision site. Physical examination revealed a 30-cm pink and violaceous, asymmetric, reticulated patch (Figure 1). The patch was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids as well as a short course of oral prednisone. The patient’s medical history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Histopathologic examination revealed widely dilated vascular channels containing collections of histiocytes in the superficial dermis. In addition, adjacent features of chronic lymphedema were present, namely interstitial fibroplasia with dilated lymphatic vessels and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with intralymphatic histiocytosis, a rare disease most commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Our patient did not have a history or clinical symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous condition reported by O’Grady et al1 in 1994. This condition has been most frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis2; however, there has been an emerging association in patients with orthopedic metal implants, with and without a concomitant diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Cases associated with metal implants are rare.2-7

The condition presents as asymptomatic red, brown, or violaceous patches, plaques, papules, or nodules that are ill defined and tend to demonstrate a livedo reticularis–like pattern. The lesions typically are overlying or in close proximity to a joint. Histopathologic findings include dilated vascular structures in the reticular dermis, some with empty lumina and others containing collections of mononuclear histiocytes. There also may be an inflammatory infiltrate in the adjacent dermis composed of a mix of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and/or histiocytes. Endothelial cells lining the dilated lumina express immunoreactivity for CD31, CD34, D2-40, Lyve-1, and Prox-1. Intravascular histiocytes are positive for CD68 and CD31.6

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains undefined. Some hypothesize that intralymphatic histiocytosis could be the early stage of reactive angioendotheliomatosis, as these conditions share clinical and histological features.8 Reactive angioendotheliomatosis also is a rare condition that may present as erythematous to violaceous patches or plaques. The lesions are commonly found on the limbs and may be associated with constitutional symptoms. Histologic findings of reactive angioendotheliomatosis include a proliferation of epithelioid, round, or spindle-shaped cells within the lumina of dermal blood vessels, which show positivity for CD31 and CD34.9 Others suggest the lesions of intralymphatic histiocytosis arise from lymphangiectasia; obstruction of lymphatic drainage due to congenital abnormalities; or acquired damage from infection, trauma, surgery, or radiation.2 Due to the common association with rheumatoid arthritis and orthopedic implants, it is likely that lymphatic stasis secondary to chronic inflammation plays a notable role.

Therapies such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, local radiotherapy, cyclophosphamide, pentoxifylline, and arthrocentesis have been attempted without evidence of efficacy.2 Although intralymphatic histiocytosis is chronic and resistant to therapy, patients can be reassured that the condition runs a benign course.

1. O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

2. Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

3. Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

4. Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

5. Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

6. Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

7. Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.