User login

New Sepsis Definition, Bedside Screening to Identify Patients at High-Mortality Risk

Clinical question: What are the best criteria to identify sepsis and septic shock?

Bottom line: An international task force of experts has updated the definitions of sepsis and septic shock and created a new bedside scoring tool to identify patients with suspected infection who may be at high risk for poor outcomes. Based on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, the new quickSOFA states that meeting 2 of 3 clinical criteria (respiratory rate of 22 per minute or greater, systolic blood pressure of 100 mg Hg or less, and altered mental status) identifies patients at high risk of poor outcomes from sepsis. This score will need to be validated further in multiple health care settings before it can be widely accepted in clinical practice. (LOE = 5)

References: Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315(8):801-810.

Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315(8):762-774.

Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315(8):775-787.

Study design: Other

Funding source: Foundation

Allocation: Uncertain

Setting: Inpatient (ward only)

Synopsis: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria are present in many hospitalized patients, even those without infections or life-threatening illnesses. The use of these criteria to identify sepsis may lead to misdiagnosis. Funded by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, an international task force consisting of 19 critical care, infectious disease, surgical, and pulmonary specialists convened to update the definitions of sepsis and septic shock and identify clinical criteria that can be used to recognize patients at high risk for mortality. Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies followed by a Delphi consensus process to determine appropriate criteria for identifying septic shock. Furthermore, they validated and confirmed the ability of different clinical criteria, including the SIRS criteria and the SOFA score, to predict poor outcomes in patients with suspected infection.

Per the task force's recommendations, sepsis should be defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Septic shock is a subset of sepsis in which there is an increased risk of mortality due to profound circulatory and cellular metabolism abnormalities. Sepsis can be identified by an increase in the SOFA score of 2 points or more. This is associated with an in-hospital mortality exceeding 10%. Septic shock can be identified by a vasopressor requirement to maintain a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg or greater and a serum lactate level greater than 18 mg/dL (> 2 mmol/L) after adequate fluid resuscitation. This combination of clinical criteria is associated with a hospital mortality rate of 40%.

Using a derivation and validation cohort of approximately 75,000 patients, the group also developed a new bedside clinical measure termed quickSOFA, or qSOFA, which consists of a respiratory rate of 22 per minute or greater, altered mental status, and systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg or less. Patients with suspected infection who are not in the intensive care unit and have at least 2 of these 3 criteria are at higher risk of poor outcomes from sepsis (area under receiver operating characteristics curve = 0.81).

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: What are the best criteria to identify sepsis and septic shock?

Bottom line: An international task force of experts has updated the definitions of sepsis and septic shock and created a new bedside scoring tool to identify patients with suspected infection who may be at high risk for poor outcomes. Based on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, the new quickSOFA states that meeting 2 of 3 clinical criteria (respiratory rate of 22 per minute or greater, systolic blood pressure of 100 mg Hg or less, and altered mental status) identifies patients at high risk of poor outcomes from sepsis. This score will need to be validated further in multiple health care settings before it can be widely accepted in clinical practice. (LOE = 5)

References: Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315(8):801-810.

Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315(8):762-774.

Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315(8):775-787.

Study design: Other

Funding source: Foundation

Allocation: Uncertain

Setting: Inpatient (ward only)

Synopsis: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria are present in many hospitalized patients, even those without infections or life-threatening illnesses. The use of these criteria to identify sepsis may lead to misdiagnosis. Funded by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, an international task force consisting of 19 critical care, infectious disease, surgical, and pulmonary specialists convened to update the definitions of sepsis and septic shock and identify clinical criteria that can be used to recognize patients at high risk for mortality. Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies followed by a Delphi consensus process to determine appropriate criteria for identifying septic shock. Furthermore, they validated and confirmed the ability of different clinical criteria, including the SIRS criteria and the SOFA score, to predict poor outcomes in patients with suspected infection.

Per the task force's recommendations, sepsis should be defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Septic shock is a subset of sepsis in which there is an increased risk of mortality due to profound circulatory and cellular metabolism abnormalities. Sepsis can be identified by an increase in the SOFA score of 2 points or more. This is associated with an in-hospital mortality exceeding 10%. Septic shock can be identified by a vasopressor requirement to maintain a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg or greater and a serum lactate level greater than 18 mg/dL (> 2 mmol/L) after adequate fluid resuscitation. This combination of clinical criteria is associated with a hospital mortality rate of 40%.

Using a derivation and validation cohort of approximately 75,000 patients, the group also developed a new bedside clinical measure termed quickSOFA, or qSOFA, which consists of a respiratory rate of 22 per minute or greater, altered mental status, and systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg or less. Patients with suspected infection who are not in the intensive care unit and have at least 2 of these 3 criteria are at higher risk of poor outcomes from sepsis (area under receiver operating characteristics curve = 0.81).

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: What are the best criteria to identify sepsis and septic shock?

Bottom line: An international task force of experts has updated the definitions of sepsis and septic shock and created a new bedside scoring tool to identify patients with suspected infection who may be at high risk for poor outcomes. Based on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, the new quickSOFA states that meeting 2 of 3 clinical criteria (respiratory rate of 22 per minute or greater, systolic blood pressure of 100 mg Hg or less, and altered mental status) identifies patients at high risk of poor outcomes from sepsis. This score will need to be validated further in multiple health care settings before it can be widely accepted in clinical practice. (LOE = 5)

References: Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315(8):801-810.

Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315(8):762-774.

Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315(8):775-787.

Study design: Other

Funding source: Foundation

Allocation: Uncertain

Setting: Inpatient (ward only)

Synopsis: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria are present in many hospitalized patients, even those without infections or life-threatening illnesses. The use of these criteria to identify sepsis may lead to misdiagnosis. Funded by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, an international task force consisting of 19 critical care, infectious disease, surgical, and pulmonary specialists convened to update the definitions of sepsis and septic shock and identify clinical criteria that can be used to recognize patients at high risk for mortality. Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies followed by a Delphi consensus process to determine appropriate criteria for identifying septic shock. Furthermore, they validated and confirmed the ability of different clinical criteria, including the SIRS criteria and the SOFA score, to predict poor outcomes in patients with suspected infection.

Per the task force's recommendations, sepsis should be defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Septic shock is a subset of sepsis in which there is an increased risk of mortality due to profound circulatory and cellular metabolism abnormalities. Sepsis can be identified by an increase in the SOFA score of 2 points or more. This is associated with an in-hospital mortality exceeding 10%. Septic shock can be identified by a vasopressor requirement to maintain a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg or greater and a serum lactate level greater than 18 mg/dL (> 2 mmol/L) after adequate fluid resuscitation. This combination of clinical criteria is associated with a hospital mortality rate of 40%.

Using a derivation and validation cohort of approximately 75,000 patients, the group also developed a new bedside clinical measure termed quickSOFA, or qSOFA, which consists of a respiratory rate of 22 per minute or greater, altered mental status, and systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg or less. Patients with suspected infection who are not in the intensive care unit and have at least 2 of these 3 criteria are at higher risk of poor outcomes from sepsis (area under receiver operating characteristics curve = 0.81).

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Research Reaffirms Management of Hospitalized Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Clinical question: What is the best antibiotic strategy to improve outcomes in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia?

Bottom line: For patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), start antibiotics early, use either fluoroquinolone monotherapy or beta-lactam/macrolide combination therapy, and switch to oral antibiotics as soon as patients are hemodynamically stable and can take oral medications. Although the evidence is mostly of low quality, this review reaffirms what we already do. (LOE = 2a)

Reference: Lee JS, Giesler DL, Gellad WF, Fine MJ. Antibiotic therapy for adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA 2016;315(6):593-602.

Study design: Systematic review

Funding source: Unknown/not stated

Allocation: Uncertain

Setting: Inpatient (ward only)

Synopsis: These investigators searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane databases to identify studies that evaluated outcomes for patients hospitalized with CAP with regard to optimal timing of antibiotic initiation, initial antibiotic selection, and criteria for transition from intravenous to oral antibiotic therapy. Two authors independently reviewed studies for inclusion and assessed study quality.

Of 8 low-quality observational studies, 4 showed a significant association between initiating antibiotic therapy within 4 hours to 8 hours of hospital arrival and reduced mortality. When comparing 2 different antibiotic strategies, 6 of 8 observational studies showed mortality benefit with the use of beta-lactams plus macrolides as compared with beta-lactam monotherapy, though the 2 recent high-quality randomized trials had conflicting results. All three observational studies that compared fluoroquinolones with beta-lactam monotherapy for the treatment of CAP showed an association with fluoroquinolone use and decreased mortality.

Finally, one high-quality trial showed that transitioning patients to oral antibiotics once they meet clinical criteria for stability (stable vital signs, lack of confusion, ability to tolerate oral medications) leads to a shorter length of stay.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: What is the best antibiotic strategy to improve outcomes in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia?

Bottom line: For patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), start antibiotics early, use either fluoroquinolone monotherapy or beta-lactam/macrolide combination therapy, and switch to oral antibiotics as soon as patients are hemodynamically stable and can take oral medications. Although the evidence is mostly of low quality, this review reaffirms what we already do. (LOE = 2a)

Reference: Lee JS, Giesler DL, Gellad WF, Fine MJ. Antibiotic therapy for adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA 2016;315(6):593-602.

Study design: Systematic review

Funding source: Unknown/not stated

Allocation: Uncertain

Setting: Inpatient (ward only)

Synopsis: These investigators searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane databases to identify studies that evaluated outcomes for patients hospitalized with CAP with regard to optimal timing of antibiotic initiation, initial antibiotic selection, and criteria for transition from intravenous to oral antibiotic therapy. Two authors independently reviewed studies for inclusion and assessed study quality.

Of 8 low-quality observational studies, 4 showed a significant association between initiating antibiotic therapy within 4 hours to 8 hours of hospital arrival and reduced mortality. When comparing 2 different antibiotic strategies, 6 of 8 observational studies showed mortality benefit with the use of beta-lactams plus macrolides as compared with beta-lactam monotherapy, though the 2 recent high-quality randomized trials had conflicting results. All three observational studies that compared fluoroquinolones with beta-lactam monotherapy for the treatment of CAP showed an association with fluoroquinolone use and decreased mortality.

Finally, one high-quality trial showed that transitioning patients to oral antibiotics once they meet clinical criteria for stability (stable vital signs, lack of confusion, ability to tolerate oral medications) leads to a shorter length of stay.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: What is the best antibiotic strategy to improve outcomes in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia?

Bottom line: For patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), start antibiotics early, use either fluoroquinolone monotherapy or beta-lactam/macrolide combination therapy, and switch to oral antibiotics as soon as patients are hemodynamically stable and can take oral medications. Although the evidence is mostly of low quality, this review reaffirms what we already do. (LOE = 2a)

Reference: Lee JS, Giesler DL, Gellad WF, Fine MJ. Antibiotic therapy for adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA 2016;315(6):593-602.

Study design: Systematic review

Funding source: Unknown/not stated

Allocation: Uncertain

Setting: Inpatient (ward only)

Synopsis: These investigators searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane databases to identify studies that evaluated outcomes for patients hospitalized with CAP with regard to optimal timing of antibiotic initiation, initial antibiotic selection, and criteria for transition from intravenous to oral antibiotic therapy. Two authors independently reviewed studies for inclusion and assessed study quality.

Of 8 low-quality observational studies, 4 showed a significant association between initiating antibiotic therapy within 4 hours to 8 hours of hospital arrival and reduced mortality. When comparing 2 different antibiotic strategies, 6 of 8 observational studies showed mortality benefit with the use of beta-lactams plus macrolides as compared with beta-lactam monotherapy, though the 2 recent high-quality randomized trials had conflicting results. All three observational studies that compared fluoroquinolones with beta-lactam monotherapy for the treatment of CAP showed an association with fluoroquinolone use and decreased mortality.

Finally, one high-quality trial showed that transitioning patients to oral antibiotics once they meet clinical criteria for stability (stable vital signs, lack of confusion, ability to tolerate oral medications) leads to a shorter length of stay.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Similarities seen in rate and rhythm control for postsurgical AF

CHICAGO – Rate and rhythm control proved equally effective for treatment of new-onset post–cardiac surgery atrial fibrillation in a randomized trial that was far and away the largest ever to examine the best way to address this common and costly arrhythmia, Dr. A. Marc Gillinov said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Thus, either strategy is acceptable. That being said, rate control gets the edge as the initial treatment strategy because it avoids the considerable toxicities accompanying amiodarone for rhythm control, most of which arise only after patients have been discharged from the hospital. In contrast, when rate control doesn’t work, it becomes evident while the patient is still in the hospital, according to Dr. Gillinov, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic .

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common complication of cardiac surgery, with an incidence variously reported at 20%-50%. It results in lengthier hospital stays, greater cost of care, and increased risks of mortality, stroke, heart failure, and infection. Postoperative AF adds an estimated $1 billion per year to health care costs in the United States.

While current ACC/AHA/Heart Rhythm Society joint guidelines recommend rate control with a beta-blocker as first-line therapy for patients with this postoperative complication, with a class I, level-of-evidence A rating, upon closer inspection the evidence cited mainly involves extrapolation from studies looking at how to prevent postoperative AF. Because no persuasive evidence existed as to how best to treat this common and economically and medically costly condition, Dr. Gillinov and his coinvestigators in the National Institutes of Health–funded Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network carried out a randomized trial 10-fold larger than anything prior.

The 23-site study included 2,109 patients enrolled prior to cardiac surgery, of whom 40% underwent isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) while the other 60% had valve surgery, either alone or with CABG. These proportions reflect current cardiac surgery treatment patterns nationally. Overall, 33% of the cardiac surgery patients experienced postoperative AF. The incidence was 28% in patients who underwent isolated CABG but rose with increasing surgical complexity to nearly 50% in patients who had combined CABG and valve operations. The average time to onset of postoperative AF was 2.4 days.

A total of 523 patients with postoperative AF were randomized to rate or rhythm control. Rate control most often entailed use of a beta-blocker, while amiodarone was prescribed for rhythm control.

The primary endpoint in the trial was a measure of health care resource utilization: total days in hospital during a 60-day period starting from the time of randomization. This endpoint was a draw: a median of 5.1 days with rate control and 5.0 days with rhythm control.

At hospital discharge, 89.9% of patients in the rate control group and 93.5% in the rhythm control group had a stable heart rhythm without AF. From discharge to 60 days, 84.2% of patients in the rate control group and a similar 86.9% of the rhythm control group remained free of AF.

Rates of serious adverse events were similar in the two groups: 24.8 per 100 patient-months in the rate control arm and 26.4 per 100 patient-months in the rhythm control arm. Three patients in the rate control arm died during the 60-day study period, and two died in the rhythm control group.

Of note, roughly one-quarter of patients in each study arm crossed over to the other arm. In the rate control group, this was typically due to drug ineffectiveness, while in the rhythm control arm the switch was most often made in response to amiodarone side effects.

Roughly 43% of patients in each group were placed on anticoagulation with warfarin for 60 days according to study protocol, which called for such action if a patient remained in AF 48 hours after randomization.

There were five strokes, one case of transient ischemic attack, and four noncerebral thromboembolisms. Also, 21 bleeding events occurred, 17 of which were classified as serious; 90% of the bleeding events happened in patients on warfarin.

“I found the results very striking and very reassuring,” said discussant Hugh G. Calkins. “To me, the clinical message is clearly that rate control is the preference.”

It was troubling, however, to see that 10 thromboembolic events occurred in 523 patients over the course of just 60 days. “Should we be anticoagulating these postsurgical atrial fibrillation patients a lot more frequently?” asked Dr. Calkins, professor of medicine and of pediatrics and director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Gillinov replied that he and his colleagues in the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network consider that to be the key remaining question regarding postoperative AF. They are now planning a clinical trial aimed at finding the optimal balance between stroke protection via anticoagulation and bleeding risk.

The National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded the work. Dr. Gillinov reported serving as a consultant to five surgical device companies, none of which played any role in the study.

Simultaneously with Dr. Gillinov’s presentation at ACC 16, the study results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602002).

CHICAGO – Rate and rhythm control proved equally effective for treatment of new-onset post–cardiac surgery atrial fibrillation in a randomized trial that was far and away the largest ever to examine the best way to address this common and costly arrhythmia, Dr. A. Marc Gillinov said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Thus, either strategy is acceptable. That being said, rate control gets the edge as the initial treatment strategy because it avoids the considerable toxicities accompanying amiodarone for rhythm control, most of which arise only after patients have been discharged from the hospital. In contrast, when rate control doesn’t work, it becomes evident while the patient is still in the hospital, according to Dr. Gillinov, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic .

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common complication of cardiac surgery, with an incidence variously reported at 20%-50%. It results in lengthier hospital stays, greater cost of care, and increased risks of mortality, stroke, heart failure, and infection. Postoperative AF adds an estimated $1 billion per year to health care costs in the United States.

While current ACC/AHA/Heart Rhythm Society joint guidelines recommend rate control with a beta-blocker as first-line therapy for patients with this postoperative complication, with a class I, level-of-evidence A rating, upon closer inspection the evidence cited mainly involves extrapolation from studies looking at how to prevent postoperative AF. Because no persuasive evidence existed as to how best to treat this common and economically and medically costly condition, Dr. Gillinov and his coinvestigators in the National Institutes of Health–funded Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network carried out a randomized trial 10-fold larger than anything prior.

The 23-site study included 2,109 patients enrolled prior to cardiac surgery, of whom 40% underwent isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) while the other 60% had valve surgery, either alone or with CABG. These proportions reflect current cardiac surgery treatment patterns nationally. Overall, 33% of the cardiac surgery patients experienced postoperative AF. The incidence was 28% in patients who underwent isolated CABG but rose with increasing surgical complexity to nearly 50% in patients who had combined CABG and valve operations. The average time to onset of postoperative AF was 2.4 days.

A total of 523 patients with postoperative AF were randomized to rate or rhythm control. Rate control most often entailed use of a beta-blocker, while amiodarone was prescribed for rhythm control.

The primary endpoint in the trial was a measure of health care resource utilization: total days in hospital during a 60-day period starting from the time of randomization. This endpoint was a draw: a median of 5.1 days with rate control and 5.0 days with rhythm control.

At hospital discharge, 89.9% of patients in the rate control group and 93.5% in the rhythm control group had a stable heart rhythm without AF. From discharge to 60 days, 84.2% of patients in the rate control group and a similar 86.9% of the rhythm control group remained free of AF.

Rates of serious adverse events were similar in the two groups: 24.8 per 100 patient-months in the rate control arm and 26.4 per 100 patient-months in the rhythm control arm. Three patients in the rate control arm died during the 60-day study period, and two died in the rhythm control group.

Of note, roughly one-quarter of patients in each study arm crossed over to the other arm. In the rate control group, this was typically due to drug ineffectiveness, while in the rhythm control arm the switch was most often made in response to amiodarone side effects.

Roughly 43% of patients in each group were placed on anticoagulation with warfarin for 60 days according to study protocol, which called for such action if a patient remained in AF 48 hours after randomization.

There were five strokes, one case of transient ischemic attack, and four noncerebral thromboembolisms. Also, 21 bleeding events occurred, 17 of which were classified as serious; 90% of the bleeding events happened in patients on warfarin.

“I found the results very striking and very reassuring,” said discussant Hugh G. Calkins. “To me, the clinical message is clearly that rate control is the preference.”

It was troubling, however, to see that 10 thromboembolic events occurred in 523 patients over the course of just 60 days. “Should we be anticoagulating these postsurgical atrial fibrillation patients a lot more frequently?” asked Dr. Calkins, professor of medicine and of pediatrics and director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Gillinov replied that he and his colleagues in the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network consider that to be the key remaining question regarding postoperative AF. They are now planning a clinical trial aimed at finding the optimal balance between stroke protection via anticoagulation and bleeding risk.

The National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded the work. Dr. Gillinov reported serving as a consultant to five surgical device companies, none of which played any role in the study.

Simultaneously with Dr. Gillinov’s presentation at ACC 16, the study results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602002).

CHICAGO – Rate and rhythm control proved equally effective for treatment of new-onset post–cardiac surgery atrial fibrillation in a randomized trial that was far and away the largest ever to examine the best way to address this common and costly arrhythmia, Dr. A. Marc Gillinov said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Thus, either strategy is acceptable. That being said, rate control gets the edge as the initial treatment strategy because it avoids the considerable toxicities accompanying amiodarone for rhythm control, most of which arise only after patients have been discharged from the hospital. In contrast, when rate control doesn’t work, it becomes evident while the patient is still in the hospital, according to Dr. Gillinov, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic .

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common complication of cardiac surgery, with an incidence variously reported at 20%-50%. It results in lengthier hospital stays, greater cost of care, and increased risks of mortality, stroke, heart failure, and infection. Postoperative AF adds an estimated $1 billion per year to health care costs in the United States.

While current ACC/AHA/Heart Rhythm Society joint guidelines recommend rate control with a beta-blocker as first-line therapy for patients with this postoperative complication, with a class I, level-of-evidence A rating, upon closer inspection the evidence cited mainly involves extrapolation from studies looking at how to prevent postoperative AF. Because no persuasive evidence existed as to how best to treat this common and economically and medically costly condition, Dr. Gillinov and his coinvestigators in the National Institutes of Health–funded Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network carried out a randomized trial 10-fold larger than anything prior.

The 23-site study included 2,109 patients enrolled prior to cardiac surgery, of whom 40% underwent isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) while the other 60% had valve surgery, either alone or with CABG. These proportions reflect current cardiac surgery treatment patterns nationally. Overall, 33% of the cardiac surgery patients experienced postoperative AF. The incidence was 28% in patients who underwent isolated CABG but rose with increasing surgical complexity to nearly 50% in patients who had combined CABG and valve operations. The average time to onset of postoperative AF was 2.4 days.

A total of 523 patients with postoperative AF were randomized to rate or rhythm control. Rate control most often entailed use of a beta-blocker, while amiodarone was prescribed for rhythm control.

The primary endpoint in the trial was a measure of health care resource utilization: total days in hospital during a 60-day period starting from the time of randomization. This endpoint was a draw: a median of 5.1 days with rate control and 5.0 days with rhythm control.

At hospital discharge, 89.9% of patients in the rate control group and 93.5% in the rhythm control group had a stable heart rhythm without AF. From discharge to 60 days, 84.2% of patients in the rate control group and a similar 86.9% of the rhythm control group remained free of AF.

Rates of serious adverse events were similar in the two groups: 24.8 per 100 patient-months in the rate control arm and 26.4 per 100 patient-months in the rhythm control arm. Three patients in the rate control arm died during the 60-day study period, and two died in the rhythm control group.

Of note, roughly one-quarter of patients in each study arm crossed over to the other arm. In the rate control group, this was typically due to drug ineffectiveness, while in the rhythm control arm the switch was most often made in response to amiodarone side effects.

Roughly 43% of patients in each group were placed on anticoagulation with warfarin for 60 days according to study protocol, which called for such action if a patient remained in AF 48 hours after randomization.

There were five strokes, one case of transient ischemic attack, and four noncerebral thromboembolisms. Also, 21 bleeding events occurred, 17 of which were classified as serious; 90% of the bleeding events happened in patients on warfarin.

“I found the results very striking and very reassuring,” said discussant Hugh G. Calkins. “To me, the clinical message is clearly that rate control is the preference.”

It was troubling, however, to see that 10 thromboembolic events occurred in 523 patients over the course of just 60 days. “Should we be anticoagulating these postsurgical atrial fibrillation patients a lot more frequently?” asked Dr. Calkins, professor of medicine and of pediatrics and director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Gillinov replied that he and his colleagues in the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network consider that to be the key remaining question regarding postoperative AF. They are now planning a clinical trial aimed at finding the optimal balance between stroke protection via anticoagulation and bleeding risk.

The National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded the work. Dr. Gillinov reported serving as a consultant to five surgical device companies, none of which played any role in the study.

Simultaneously with Dr. Gillinov’s presentation at ACC 16, the study results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602002).

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: Rate control offers the advantage of simplicity over a rhythm control strategy in new-onset atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery.

Major finding: Rate and rhythm control strategies for treatment of new-onset atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery resulted in equal numbers of hospital days, similar serious complication rates, and low rates of persistent atrial fibrillation at 60 days of follow-up.

Data source: A randomized clinical trial of 523 patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery at 23 U.S. and Canadian academic medical centers.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and carried out through the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network. The presenter reported having no relevant financial interests.

Treatments for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

From the Center for Narcolepsy, Sleep and Health Research, Department of Biobehavioral Health Science, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the efficacy of current treatment options for adults with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: OSA, characterized by repetitive ≥ 10-second interruptions (apnea) or reductions (hypopnea) in airflow, is initiated by partial or complete collapse in the upper airway despite respiratory effort. When left untreated, OSA is associated with comorbid conditions, such as cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. The current “gold standard” treatment for OSA is continuous positive air pressure (CPAP), which pneumatically stabilizes the upper airways. CPAP has proven efficacy and potential cost savings via decreases in health comorbidities and/or motor-vehicle crashes. However, CPAP treatment is not well-tolerated due to various side effects, and adherence among OSA subjects can be as low as 50% in certain populations. Other treatment options for OSA include improving CPAP tolerability, increasing CPAP adherence through patient interventions, weight loss/exercise, positional therapy, nasal expiratory positive airway pressure, oral pressure therapy, oral appliances, surgery, hypoglossal nerve stimulation, drug treatment, and combining 2 or more of the aforementioned treatments. Despite the many options available to treat OSA, none of them are as efficacious as CPAP. However, many of these treatments are tolerable, and adherence rates are higher than those of the CPAP, making them a more viable treatment option for long-term use.

- Conclusion: Patients need to weigh the benefits and risks of available treatments for OSA. More large randomized controlled studies on treatments or combination of treatments for OSA are needed that measure parameters such as treatment adherence, apnea-hypopnea index, oxygen desaturation, subjective sleepiness, quality of life, and adverse events.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), characterized by repetitive ≥ 10-second interruptions (apnea) or reductions (hypopnea) in airflow (measured as events/hour, called the apnea-hypopnea index [AHI]), is initiated by partial or complete collapse in the upper airway despite respiratory effort [1]. Current estimates of the prevalence of OSA (AHI ≥ 5 and Epworth Sleepiness Scale > 10) in American men and women (aged 30–70 years) are 14% and 5%, respectively, with prevalence rates increasing due to increasing rates of obesity, a risk factor for developing OSA [2]. Hypoxemia/hypercapnia, fragmented sleep, as well as exaggerated fluctuations in heart rhythm, blood pressure, and intrathoracic pressure are some of the acute physiological effects of untreated OSA [1]. These acute effects can develop into long-term sequelae, such as hypertension and other cardiovascular comorbidities [2,3], decrements in cognitive function [4,5], poor mood, reduced quality of life [6,7], and premature death [8,9]. In economic terms, health care cost estimates of OSA and its associated comorbidities rival that of diabetes [10]. Additionally, in the year 2000, more than 800,000 drivers were involved OSA-related motor-vehicle collisions, of which more than 1400 fatalities occurred [11].

Front-line treatment of OSA relies on mechanically stabilizing the upper airway with a column of air via continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment. Though CPAP is the “gold standard” treatment for OSA with proven efficacy and potential cost savings via decreases in health comorbidities and/or motor-vehicle crashes [10–12], CPAP treatment is not well-tolerated due to various side effects [13–15]. Adherence among OSA subjects can be as low as 50% in certain populations [16–18]. Improved strategies for current and innovative treatments have emerged in the last few years and are the subject of this review.

Improved CPAP Treatment

As stated previously, CPAP pneumatically splints the upper airway, thus preventing it from collapsing during sleep. However, CPAP is not well-tolerated. Modifications to standard CPAP to increase adherence have been met with disappointing results. Humidification with heated tubing delivering heated moistened air did not increase compliance compared to standard CPAP [19]. CPAP was also compared with auto-adjusting CPAP (APAP), where respiration is monitored and the minimum pressure of air is applied to splint the upper airway open. In a meta-analysis, APAP only had very small effect on compliance [20]. Lastly, reduction in pressure during expiration was investigated, and a meta-analysis showed no effect [21,22]. However, recent advances in CPAP delivery give hope to increasing compliance. The S9CPAP machine (Resmed, San Diego, CA), which combines a humidification system and an APAP, showed increased compliance compared to standard CPAP. Compliance increased by an average of 30 minutes per night, and variance of daily usage decreased (eg, patients used it more day-to-day) [23]. However, a randomized blinded study needs to be conducted to corroborate these results.

Promoting CPAP Adherence Through Patient Interventions

Educational, supportive, and behavioral interventions have been used to increase CPAP adherence and have been thoroughly reviewed via meta-analysis [24]. Briefly, 30 studies of various interventions were included and demonstrated that educational, supportive, or behavioral interventions increased CPAP usage in OSA-naive patients. Behavioral interventions increased CPAP usage by over an hour, but the evidence was of “low-quality.” Educational and supportive interventions also increased CPAP usage, with the former having “moderate-quality” evidence [24]. However, whether increased CPAP usage had an effect on symptoms and quality of life was statistically unclear, and the authors recommended further assessment [24]. Three more studies on interventions to increase CPAP usage have been conducted since the aforementioned review. In a randomized controlled study, investigators had OSA patients participate in a 30-minute group social cognitive therapy session (eg, increasing perceived self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and social support) to increase CPAP adherence. Compared to a social interaction control group, there was no increase in adherence rates [25]. In another smaller randomized controlled study that used a social cognition model of behavioral therapy, there were small increases of CPAP usage. At 3 months, the social cognitive intervention increased CPAP usage by an average of 23 minutes per night, increased the number of individuals using their CPAP machine for more than 4 hours compared to standard care group, and decreased symptom of sleepiness [26]. And lastly, a preliminary study looked at increasing adherence rates by utilizing easily accessible alternative care providers, such as nurses and respiratory therapists, for the management of OSA [27]. Though this study had no control group, it did show that good adherence and a decrease in symptoms of sleepiness could be achieved with non-physician management of OSA [27]. A randomized controlled study will be needed to validate the use of alternative care providers.

Interventions have shown some success in increasing adherence rates, but the question remains on who should receive those interventions. Predicting which OSA patients are in most need of an intervention has been studied. A recent study used a 19-question assessment tool called the Index of Nonadherence to PAP to screen for nonadherers (OSA patients who used CPAP for less than 4 hours a night, after 1 month of OSA diagnosis). The assessment tool was 87% sensitive and 63% specific at determining those OSA patients who would not adhere to CPAP treatment [28]. Another study investigated the reliability and validity of a self-rating scale measuring the side effects of CPAP and their consequences on adherence [15]. The investigators showed that the scale was able to reliably discriminate between those who adhered to CPAP treatment and those that did not [15]. Both of these scales can be used to screen OSA patients that need interventions to increase CPAP adherence. Lastly, a recent systematic review showed that a user’s CPAP experience was not defined by the user but by the user’s health care provider, who framed CPAP as “problematic” [29]. The authors argue that users of CPAP are “primed” to reflect negatively on their CPAP experience [29]. Interventions can be used to change the way OSA patients think or feel about their CPAP machines.

When OSA Patients Do Not Adhere to CPAP Treatment

With adherence rates as low as 50% [16–18], those who fail to tolerate CPAP are unlikely to be referred for additional treatment [30]. Those who do tolerate treatment dislike the side effects of CPAP and show an interest in other treatment options [14]. Other treatment options have been shown to decrease the severity of OSA.

Weight Loss and Exercise

OSA prevalence is correlated with body mass index (BMI), and the increasing rates of OSA has been attributed to the increasing rates of obesity in the United States [2]. A meta-analysis of 3 randomized controlled studies of weight loss induced by dieting or lifestyle change showed that weight loss decreased OSA severity. The effect was the greatest for OSA patients who lost more than 10 kg or had severe OSA at baseline [31]. A recent randomized controlled study involving OSA patients with type 2 diabetes investigated if either a weight loss intervention or a diabetes support and education intervention would be able to decrease OSA severity [32]. The weight loss intervention significantly decreased OSA severity, which was largely but not entirely attributed to weight loss. The participants regained 50% of their weight 4 years after the intervention and still had significantly less severe OSA compared to control intervention group. The downside to this intervention is the intensity of the regimen to which the subjects had to adapt: portion-controlled diets with liquid meals and snack bars for the first 4 months and moderate-intensity physical activity for a minimum of 3 hours a week for the first year. After that, patients were still required to follow through with the intervention for 3 years, which included one on-site visit per month and a second contact by phone, mail, or email [32]. One study looked at weight loss and sleep position (supine vs. lateral). The study showed a decrease in AHI in OSA patients that lost weight, and the biggest decrease was in AHI in the lateral sleeping position [33]. Another study looked at the more invasive procedure of bariatric surgery to decrease weight and OSA. At the 1-year follow-up, patients had significantly decreased their BMI and AHI [34]. Two more randomized controlled studies investigated if exercise or fitness level might be beneficial to OSA patients independent of weight loss. Exercise improved AHI even though there was not a significant decrease in weight between the exercise and stretching control group [35]. However, an increase in fitness level did not have any additive effect on the decrease of AHI when weight change was taken into account [36]. The difference in results might be attributed to the latter study using older type 2 diabetic patients and moderate physical activity, while the former studied incorporated moderate-intensity aerobic activity and resistance training for younger patients [35,36]. There is evidence that a sedentary lifestyle increases diurnal leg fluid volume that can shift to the neck during sleep and might play a role in pathogenesis of OSA [37]. Decreasing a sedentary lifestyle by exercising might therefore be beneficial to OSA patients. Given the increasing rates of obesity [2], implementing weight loss as a solution to OSA is viable, especially considering that OSA is not the only comorbid disease of obesity [38].

Positional Therapy

It has been known for some time that sleeping in a supine position doubles a patient’s AHI compared to sleeping in the lateral position [39]. A more recent analysis showed that 60% of patients were “supine predominant OSA;” these patients had supine AHI that was twice that of non-supine AHI [40]. Moreover, a drug-induced sleep endoscopy study showed that the upper airway collapses at multiple levels sleeping in the supine position as opposed to at a single level sleeping in the lateral position [41]. Another study showed that lateral sleeping position improved passive airway anatomy and decreased collapsibility [42]. Many studies have shown that patients who wear a device that alerts the sleeper that he or she is in a supine position (referred to as positional therapy) significantly decreases AHI, but long-term compliance is still an issue, and new and improved devices are needed [43]. Three new studies bolster the effectiveness of positional therapy [44–46]. In all 3 studies, sleeping in the supine position went down to 0% (no change in sleep efficiency [the ratio of total time spent sleeping to the total time spent in bed]), AHI decreased to less than 6, and sleep quality and daytime sleepiness increased and decreased, respectively [44–46]. Compliance was as low as 76% [44] and as high as 93% [46]. For those who cannot tolerate CPAP, positional therapy could be a substitute for decreasing severity of OSA. However, “phenotyping” OSA patients as “supine predominant OSA” would need to be implemented to guarantee efficacy of positional therapy.

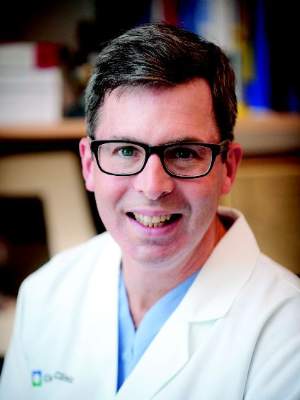

Nasal Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure

Oral Pressure Therapy

Retro-palatal collapse occurs in OSA and can be prevented by applying negative pressure to the upper airway [49]. The oral pressure therapy (OPT) device applies gentle suction anteriorly and superiorly to displace the tongue and soft palate and breathing occurs via nasopharyngeal airway [12]. A recent systematic review [49] of OPT revealed that successful OPT treatment rate was 25% to 37% if using standard and stringent definitions of treatment success. Although OPT decreased AHI, residual AHI still remained high due to positional apneas and collapse of upper airway at other levels besides retro-palatal. The authors of this systematic review recommend more rigorous and controlled studies with defined “treatment success” [49]. The advantage of OPT is that adherence was good; patients used the device on average 6 hours a night. There were no severe or serious adverse events with OPT, however oral tissue discomfort or irritation, dental discomfort, and dry mouth were reported [50].

Oral Appliances

Similar to OPT, oral appliances (OAs) attempt to prevent upper airway collapse. OAs either stabilize the tongue, advance the mandible, or lift the soft palate to increase the volumes of the upper airways to avert OSA [16, 51]. The OAs, like the mandibular advancement device, for example, have the added benefit of being fitted specifically for the OSA patient. The mandible for a patient can be advanced to alleviate obstructive apneas, but can also be pulled back if the OA is too uncomfortable or painful. However, there is still dispute on how exactly to titrate these OAs [52]. A meta-analysis recently published looked at all clinical trials of OAs through September 2015. After meeting strict exclusion/inclusion criteria, 17 studies looking at OAs were included in the meta-analysis. There were robust decreases in AHI and in symptoms of sleepiness in OSA patients that used OAs compared to control groups. However, due to the strict inclusion/exclusion criteria of the meta-analysis, all the studies except one used mandibular advancement appliances; one study used a tongue-retaining appliance. The authors concluded that there is sufficient evidence for OAs to be effective in patients with mild-to-moderate OSA [51]. Since the meta-analysis, 6 new studies have been published about OAs. In 4 of the studies (all using mandibular advancement), OAs significantly decreased AHI by 50% or more in the majority of OSA patients [53–56]. The other 2 studies looked at long-term efficacy and compliance. In both studies, there were drastic decreases in AHI when OAs were applied [57, 58]. In one study, about 40% of OSA patients stopped using the OAs. When the change in AHI was stratified between users and non-users, the users group was significantly higher that the non-user group, suggesting that the non-user group were not compliant due to less of an effect of the OA on AHI [57]. In the second study, OSA patients using OAs for a median of 16.5 years were evaluated for long-term efficacy of the OAs. At the short-term follow-up, AHI decreased by more than 50% with use of an OA. However, at the long-term follow-up, the OA lost any effect on AHI. One reason for this is that the OSA patients’ AHI without the OA at the long-term follow-up nearly doubled compared to AHI without OA at the short-term follow-up. The authors conclude that OSA patients using OAs for the long-term might undergo deteriorations in treatment efficacy of OAs, and that regular follow-up appointments with sleep apnea recordings should be implemented [58].

A similarity in all these studies is that adherence was higher for OAs compared to CPAP [51]. The caveat is that most studies have relied on self-reports for adherence rates [12]. However, there were 3 studies that implemented a sensor that measured adherence and compared those results to self-reported OA adherence. All 3 studies showed a strong relationship between self-reports and sensor adherence; patients were honest about adherence to OAs [59–61]. Studies have also been conducted to predict compliance with OAs: higher therapeutic CPAP pressure, age, OSA severity [62], decreased snoring [63], and lower BMI [64, 65] predicted compliance, while dry mouth [63], oropharyngeal crowding [65], and sleeping in a supine position [66] predicted noncompliance. Though adherence rates are high, OAs do not decrease AHI as much as CPAP [67], and a recent study showed that long-term adherence rates might not be different to CPAP adherence rates [68]. OAs, due to their higher adherence rates, are a potential second choice over CPAP. However, they are less efficacious than CPAP at decreasing AHI. That may not be as important since a recent meta-analysis comparing the effects of CPAP or OAs on blood pressure showed that both treatments significantly decreased blood pressure [69]. More studies need to be conducted over long-term efficacy of OAs compared with CPAP.

Surgeries to Treat OSA

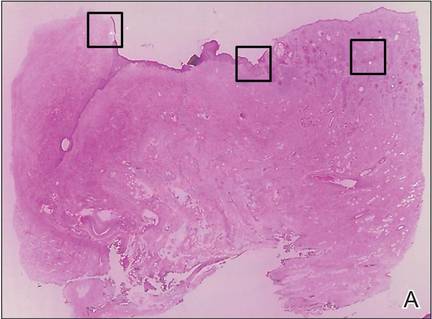

Surgery as a treatment option has been extensively reviewed and meta-analyzed [70–78]. Surgery for the treatment of OSA includes tongue suspension [70,74], maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) [72,73,78], pharyngeal surgeries (eg, uvulopharyngopalatoplasty [UPPP]) [73], laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty (LAUP) [73], radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [73], tracheostomy [71], nasal surgery [75], and glossectomy [77], as well as multi-level and multi-phased procedures [70,74,76,77]. Most studies done on surgeries were case studies, with a minority of investigations that were randomized and controlled. Glossectomy, as part of a multi-level surgical approach, decreased AHI and symptoms of sleepiness, but glossectomy as a stand-alone surgical procedure did not improve AHI [77]. Significant improvements in AHI and sleepiness symptoms were seen in a majority of OSA patients who underwent MMA [72,73,78] and tracheostomy, although tracheostomy was performed for the morbidly obese or those who have failed other traditional surgical treatments [71]. Stand-alone tongue suspension and nasal surgery did not decrease AHI in the majority of patients, though nasal surgery did decrease subjective sleepiness [70,72,74,75]. However, tongue suspension combined with UPPP had better outcomes [70]. LAUP showed inconsistent results with the majority of studies showing no change in AHI, while UPPP and RFA seemed to improved AHI, although some studies showed no change [73]. Multi-level or multi-phase surgeries also showed improvements on OSA severity, but whether these surgeries are better than stand-alone remains to be investigated [73,76]. Morbidity and adverse events, like infection or pain, are common in all of these surgical events [70–78], but there are significant differences between the procedures. For example, MMA had fewer adverse events reported compared to UPPP [73]. More recently, glossectomy via transoral robotic surgery with UPPP [79] or epiglottoplasty [80] has been investigated; there were decreases in AHI, but response rates were between 64% to 73%. Although it seems surgical procedures to treat OSA are plausible, most studies were not rigorous enough to say this with any certainty.

Hypoglossal Nerve Stimulation

OSA subjects experience upper airway obstruction due to loss of genioglossus muscle activity during sleep. Without tongue activation, the negative pressure of breathing causes the upper airways to collapse [81]. Transcutaneous, intraoral, and intramuscular devices used to electrically activate the tongue have been developed and tested; however, although these devices decreased AHI they also induced arousals and sleep fragmentation caused by the electrical stimulus [82–86]. A new method had to be developed that would not be felt by the OSA patient.

In all trials to date, there were significant decreases in AHI as long as 3 years post implantation [87–93]. There were significant improvements in symptoms of sleepiness, mood, quality of life, and sleep quality [87,88,90–94]. When OSA patients had their neurostimulators turned off for 5 days to a week, AHI returned back to baseline levels [89,92]. However, all the trials excluded morbidly obese individuals [87–93] because investigations showed that HNS had no therapeutic effect with elevated BMI [88,90]. The drawbacks of HNS are that it is surgically invasive and minor adverse events have been reported: procedural-related events (eg, numbness/pain/swelling/infection at incision site, temporary tongue weakness) that resolved with time, pain medication, and/or antibiotic treatment, or therapy-related events (eg, tongue abrasions cause by tongue movement over teeth, discomfort associated with stimulation) that resolved after acclimation. Serious adverse events occurred infrequently, such as infection at incision site requiring device removal or subsequent surgery to reposition or replace electrode cuff or malfunctioning neurostimulator [87,88,90]. HNS durability at 18 and 36 months was still very effective, with decreased AHI and increase quality of life and sleep being sustained; adverse events were uncommon this long after implantation [91,93]. Although surgery is required and adverse events are reported, the long-term significant improvement of OSA makes this a very viable treatment option over CPAP. However, increasing prevalence rates of OSA are correlated to increasing obesity rates [2], which may limit the usefulness of HNS since a BMI of more than 40 might preclude individuals to this treatment.

Pharmacologic Treatment

There are no approved pharmacologic treatments for OSA. A recent Cochrane review and meta-analysis assessed clinical trials of various drugs treating OSA. These drugs targeted 5 strategies at alleviating OSA: increasing ventilatory drive (progestogens, theophylline, and acetazolamide), increasing upper airway tone (serotonergics and cholinergics), decreasing rapid eye movement sleep (antidepressants and clonidine), increasing arousal threshold (eszopiclone), and/or increasing the cross-sectional area or reducing the surface tension of the upper airway through topical therapy (fluticasone and lubricant). The review concluded that “some of the drugs may be helpful; however, their tolerability needs to be considered in long-term trials.” Some of these drugs had little or no effect on AHI, and if they did have an effect on AHI, side effects outweighed the benefit [95]. Since then, more investigations of other drugs targeted at the previously aforementioned strategies or via new strategies have been published.

Dronabinol (synthetic Δ9-THC), a nonselective cannabinoid type 1 and type 2 receptor agonist, significantly reduced AHI and improved subjective sleepiness and alertness in a single-blind dose-escalation (2.5, 5, or 10 mg) proof-of-concept study [96,97]. Dronabinol most likely increases upper airway tone though inhibition of vagal afferents [98,99]. There were no serious adverse events associated with dronabinol. Minor adverse events included somnolence and increased appetite. Increased appetite might lead to increased weight and contradict any beneficial effects of dronabinol; however, in the 3-week treatment period no weight gain was observed [97]. This might have been due to drug administration occurring before going to sleep with no opportunity to eat. A larger randomized controlled study will be needed to establish the safety and efficacy of dronabinol.

The sedative zopiclone was used to increase arousal threshold without effecting genioglossus activity [100]. Eszopiclone, a drug in the same class, has been used in the past with unfavorable results [95]. Zopiclone was used in a small double-blind randomized controlled cross-over study. Zopiclone significantly increased respiratory arousal threshold without effecting genioglossus activity or the upper airway’s response to negative pressure. Thus, there was a trend in the zopiclone treatment to increase sleep efficiency. However, zopiclone had no effect on AHI, and increased oxygen desaturation [100]. Similar to eszopiclone, the results for zopiclone are not promising.

A new strategy to treat OSA is to modify pharmacologically “loop gain,” a dimensionless value quantifying the stability of the ventilatory control system. A high loop gain signifies instability in the ventilatory control system and predisposes an OSA person to recurrent apneas [101–103]. Three studies used drugs that inhibit carbonic anhydrase to stabilize the ventilatory control system [104–106]. Two studies used acetazolamide, which decreased loop gain in OSA patients [104,105]. Acetazolamide only decreased AHI in non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, and there was a slight correlation between decrease in loop gain and total AHI [105]. Acetazolamide also decreased ventilatory response to spontaneous arousal, thus promoting ventilatory stability [104]. In the last study, zonisamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor that also causes weight loss, was investigated in OSA patients. Sleep apnea alleviation, measured in terms of absolute elimination of sleep apnea by mechanical or pharmacologic treatment, was 61% and 13% for CPAP and zonisamide, respectively, compared with placebo. In other words, zonisamide decreased AHI but not to the extent of CPAP [106]. Zonisamide also decreased arousals and marginally, but significantly, decreased weight compared to the CPAP group. Although carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have promise as an alternative treatment, long-term use is poorly tolerated [101] and further studies need to be completed.

OSA has been linked with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), with studies suggesting OSA precipitates GERD [107] or GERD precipitates OSA [108]. A meta-analysis was recently published looking at studies that used proton pump inhibitors (PPI) to treat GERD and the effects it would have on OSA [109]. The meta-analysis only included 2 randomized trials and 4 prospective cohort studies. Two of the cohort studies showed a significant decrease, and one cohort showed no difference in apnea indices; and all 4 of the cohort studies showed no difference in AHI. In one trial, the frequency of apnea attacks as recorded by diaries significantly decreased. In 3 cohort studies and one trial, symptoms of sleepiness significantly decreased [109]. A study that was not included in the meta-analysis showed that 3 months of PPI treatment decreased AHI but did not alter sleep efficiency [110]. Larger randomized controlled studies need to be conducted on the effects of PPIs on OSA, especially since PPIs are well tolerated with only weak observational associations between PPI therapy and fractures, pneumonia, mortality, and nutritional deficiencies [111].

The drugs mentioned above have potential for treating OSA in patients intolerant to CPAP. The efficacy and side effects of the drugs will need to be studied for long-term use. However, development of pharmacologic treatments has been hampered by incomplete knowledge of the relevant sleep-dependent peripheral and central neural mechanisms controlling ventilatory drive and upper airway muscles. More importantly, additional basic science research needs to focus on the neurobiological and neurophysiological mechanisms underlying OSA to develop new pharmacotherapies or treatment strategies, or to modify previous treatment strategies.

Treatment Combinations and Phenotyping

It has been recently suggested that combining 2 or more of the above treatments might lead to greater decreases in AHI and greater improvements in subjective sleepiness [112,113]. In fact, one such treatment combination has occurred [114]. Both OA or positional therapy decrease AHI. However, the combination of an OA and positional therapy led to further significant decreases in AHI compared to when those treatments were used alone [114]. To correctly combine treatments, the patient will have to be “phenotyped” via polysomnography to discern the specific pathophysiology of the patient’s OSA. There are published reports of methods to phenotype patients according to their sleep positon, ventilation parameters, loop gain, arousal threshold, and upper airway gain, and if apneic events occur in REM or NREM sleep [40,115]. Defining these traits for individual OSA patients can lead to better efficacy and compliance of combination treatments for OSA. Combination treatment coupled with phenotyping are needed to try to reduce AHI to levels achieved with CPAP.

Conclusion

CPAP is the gold standard treatment because it substantially decreases the severity of OSA just by placing a mask over one’s face before going to sleep. However, it is not tolerable to continually have air forced into your upper airways, and new CPAP devices that heat and humidify the air, and auto titrate the pressure, have been developed to increase adherence rates, but with limited success. For all the treatments listed, a majority do not decrease the severity of OSA to levels achieved with CPAP. However, adherence rates are higher and therefore might, in the long-term, be a better option than CPAP. Some treatments involve invasive surgery to open or stabilize the upper airways, or to implant a stimulator, some treatments involve oral drugs with side effects, and some treatments involve placing appliances on your nose or in your mouth. And some treatments can be combined and individually tailored to the OSA patient via “phenotyping.” For all treatments, the benefits and risks need to be weighed by each patient. More importantly, more large randomized controlled studies on treatments or combination of treatments for OSA are needed using parameters such as treatment adherence, AHI, oxygen desaturation, subjective sleepiness, quality of life, and adverse events (both minor and major) to gauge treatment success in the short-term and long-term. Only then can OSA patients in partnership with their health care provider choose the best treatment option.

Corresponding author: Michael W. Calik, PhD, 845 S. Damen Ave (M/C 802), College of Nursing, Room 740, Chicago, IL 60612, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. In collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Center on Sleep Disorders Research (National Institutes of Health). Circulation 2008;118:1080–111.

2. Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, et al. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 2013;177:1006–14.

3. Shamsuzzaman AS, Gersh BJ, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea: implications for cardiac and vascular disease. JAMA 2003;290:1906–14.

4. Kim HC, Young T, Matthews CG, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and neuropsychological deficits. A population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156:1813–9.

5. Yaffe K, Laffan AM, Harrison SL, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. JAMA 2011;306:613–9.

6. Baldwin CM, Griffith KA, Nieto FJ, et al. The association of sleep-disordered breathing and sleep symptoms with quality of life in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep 2001;24:96–105.

7. Peppard PE, Szklo-Coxe M, Hla KM, Young T. Longitudinal association of sleep-related breathing disorder and depression. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1709–15.

8. Marshall NS, Wong KK, Liu PY, et al. Sleep apnea as an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality: the Busselton Health Study. Sleep 2008;31:1079–85.

9. Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin sleep cohort. Sleep 2008;31:1071–8.

10. AlGhanim N, Comondore VR, Fleetham J, et al. The economic impact of obstructive sleep apnea. Lung 2008;186:7–12.

11. Sassani A, Findley LJ, Kryger M, et al. Reducing motor-vehicle collisions, costs, and fatalities by treating obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 2004;27:453–8.

12. Weaver TE, Calik MW, Farabi SS, et al. Innovative treatments for adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Nat Sci Sleep 2014;6:137–47.

13. Isetta V, Negrin MA, Monasterio C, et al. A Bayesian cost-effectiveness analysis of a telemedicine-based strategy for the management of sleep apnoea: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2015;70:1054–61.

14. Tsuda H, Moritsuchi Y, Higuchi Y, Tsuda T. Oral health under use of continuous positive airway pressure and interest in alternative therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: a questionnaire-based survey. Gerodontology 2015 Feb 10.

15. Brostrom A, Arestedt KF, Nilsen P, et al. The side-effects to CPAP treatment inventory: the development and initial validation of a new tool for the measurement of side-effects to CPAP treatment. J Sleep Res 2010;19:603–11.

16. Weaver TE, Grunstein RR. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008 Feb 15;5:173–8.

17. Hedner J, Grote L, Zou D. Pharmacological treatment of sleep apnea: current situation and future strategies. Sleep Med Rev 2008;12:33–47.

18. Smith I, Lasserson TJ, Wright J. Drug therapy for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006(2):CD003002.

19. Ruhle KH, Franke KJ, Domanski U, Nilius G. Quality of life, compliance, sleep and nasopharyngeal side effects during CPAP therapy with and without controlled heated humidification. Sleep Breath 2011;15:479–85.

20. Xu T, Li T, Wei D, et al. Effect of automatic versus fixed continuous positive airway pressure for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: an up-to-date meta-analysis. Sleep Breath 2012;16:1017–26.

21. Smith I, Lasserson TJ. Pressure modification for improving usage of continuous positive airway pressure machines in adults with obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009 (4):CD003531.

22. Dungan GC, 2nd, Marshall NS, Hoyos CM, et al. A randomized crossover trial of the effect of a novel method of pressure control (SensAwake) in automatic continuous positive airway pressure therapy to treat sleep disordered breathing. J Clin Sleep Med 2011;7:261–7.

23. Wimms AJ, Richards GN, Benjafield AV. Assessment of the impact on compliance of a new CPAP system in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2013;17:69–76.

24. Wozniak DR, Lasserson TJ, Smith I. Educational, supportive and behavioural interventions to improve usage of continuous positive airway pressure machines in adults with obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;1:CD007736.

25. Bartlett D, Wong K, Richards D, et al. Increasing adherence to obstructive sleep apnea treatment with a group social cognitive therapy treatment intervention: a randomized trial. Sleep 2013;36:1647–54.

26. Deng T, Wang Y, Sun M, Chen B. Stage-matched intervention for adherence to CPAP in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Breath 2013;17:791–801.

27. Pendharkar SR, Dechant A, Bischak DP, et al. An observational study of the effectiveness of alternative care providers in the management of obstructive sleep apnoea. J Sleep Res 2015 Oct 27.

28. Sawyer AM, King TS, Hanlon A, et al. Risk assessment for CPAP nonadherence in adults with newly diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea: preliminary testing of the Index for Nonadherence to PAP (I-NAP). Sleep Breath 2014;18:875–83.

29. Ward K, Hoare KJ, Gott M. What is known about the experiences of using CPAP for OSA from the users’ perspective? A systematic integrative literature review. Sleep Med Rev 2014;18:357–66.

30. Russell JO, Gales J, Bae C, Kominsky A. Referral patterns and positive airway pressure adherence upon diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;153:881–7.

31. Hemmingsson E. Does medically induced weight loss improve obstructive sleep apnoea in the obese: review of randomized trials. Clin Obes 2011;1:26–30.

32. Kuna ST, Reboussin DM, Borradaile KE, et al. Long-term effect of weight loss on obstructive sleep apnea severity in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Sleep 2013;36:641–9A.

33. Kulkas A, Leppanen T, Sahlman J, et al. Weight loss alters severity of individual nocturnal respiratory events depending on sleeping position. Physiol Meas 2014;35:2037–52.

34. Bae EK, Lee YJ, Yun CH, Heo Y. Effects of surgical weight loss for treating obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2014;18:901–5.

35. Kline CE, Crowley EP, Ewing GB, et al. The effect of exercise training on obstructive sleep apnea and sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep 2011;34:1631–40.

36. Kline CE, Reboussin DM, Foster GD, et al. The effect of changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and weight on obstructive sleep apnea severity in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes. Sleep 2016;39:317–25.

37. Vena D, Yadollahi A, Bradley TD. Modelling fluid accumulation in the neck using simple baseline fluid metrics: implications for sleep apnea. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2014;2014:266–9.

38. Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 2009;373:1083–96.

39. Cartwright RD. Effect of sleep position on sleep apnea severity. Sleep 1984;7:110–4.

40. Joosten SA, Hamza K, Sands S, et al. Phenotypes of patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnoea as confirmed by cluster analysis. Respirology 2012;17:99–107.

41. Lee CH, Kim DK, Kim SY, et al. Changes in site of obstruction in obstructive sleep apnea patients according to sleep position: a DISE study. Laryngoscope 2015;125:248–54.

42. Joosten SA, Edwards BA, Wellman A, et al. The effect of body position on physiological factors that contribute to obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2015;38:1469–78.

43. Ravesloot MJ, van Maanen JP, Dun L, de Vries N. The undervalued potential of positional therapy in position-dependent snoring and obstructive sleep apnea-a review of the literature. Sleep Breath 2013;17:39–49.

44. Eijsvogel MM, Ubbink R, Dekker J, et al. Sleep position trainer versus tennis ball technique in positional obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11:139–47.

45. Jackson M, Collins A, Berlowitz D, et al. Efficacy of sleep position modification to treat positional obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2015;16:545–52.

46. van Maanen JP, Meester KA, Dun LN, et al. The sleep position trainer: a new treatment for positional obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep Breath 2013;17:771–9.

47. Morrell MJ, Arabi Y, Zahn B, Badr MS. Progressive retropalatal narrowing preceding obstructive apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:1974–81.

48. Riaz M, Certal V, Nigam G, et al. Nasal expiratory positive airway pressure devices (Provent) for OSA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Disorders 2015;2015:15.

49. Nigam G, Pathak C, Riaz M. Effectiveness of oral pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic analysis. Sleep Breath 2015 Oct 19.

50. Colrain IM, Black J, Siegel LC, et al. A multicenter evaluation of oral pressure therapy for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2013;14:830–7.

51. Zhu Y, Long H, Jian F, et al. The effectiveness of oral appliances for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: A meta-analysis. J Dent 2015;43:1394–402.

52. Dieltjens M, Vanderveken OM, Heyning PH, Braem MJ. Current opinions and clinical practice in the titration of oral appliances in the treatment of sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med Rev 2012;16:177–85.

53. Cantore S, Ballini A, Farronato D, et al. Evaluation of an oral appliance in patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome intolerant to continuous positive airway pressure use: Preliminary results. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2015 Dec 18.

54. Gjerde K, Lehmann S, Berge ME, et al. Oral appliance treatment in moderate and severe obstructive sleep apnoea patients non-adherent to CPAP. J Oral Rehabil 2015 Dec 27.

55. Jaiswal M, Srivastava GN, Pratap CB, et al. Effect of oral appliance for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Orthod Milwaukee 2015;26:67–71.

56. Vecchierini MF, Attali V, Collet JM, et al. A custom-made mandibular repositioning device for obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome: the ORCADES study. Sleep Med 2015 Jun 29.

57. Haviv Y, Bachar G, Aframian DJ, et al. A 2-year mean follow-up of oral appliance therapy for severe obstructive sleep apnea: a cohort study. Oral Dis 2015;21:386–92.

58. Marklund M. Long-term efficacy of an oral appliance in early treated patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2015 Nov 2.

59. Dieltjens M, Braem MJ, Vroegop AV, et al. Objectively measured vs self-reported compliance during oral appliance therapy for sleep-disordered breathing. Chest 2013;144:1495–502.

60. Smith YK, Verrett RG. Evaluation of a novel device for measuring patient compliance with oral appliances in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. J Prosthodont 2014;23:31–8.

61. Vanderveken OM, Dieltjens M, Wouters K, et al. Objective measurement of compliance during oral appliance therapy for sleep-disordered breathing. Thorax 2013;68:91–6.

62. Sutherland K, Phillips CL, Davies A, et al. CPAP pressure for prediction of oral appliance treatment response in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10:943–9.

63. Dieltjens M, Verbruggen AE, Braem MJ, et al. Determinants of objective compliance during oral appliance therapy in patients with sleep-related disordered breathing: a prospective clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015:894–900.

64. Suzuki K, Nakata S, Tagaya M, et al. Prediction of oral appliance treatment outcome in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: a preliminary study. B-ENT 2014;10:185–91.