User login

Hyperkeratotic Lesions in a Patient With Hepatitis C Virus

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Acral Erythema

Histopathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen from the right leg revealed an erosion with parakeratosis containing neutrophils and marked spongiosis favoring the upper layer of the epidermis with focal individual necrotic keratinocytes. In addition, there was a lymphocytic and neutrophilic exocytosis with edema of the papillary dermal papillae, mild papillary dermal fibrosis, and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils. Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).

The patient was prescribed clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% and oral zinc sulfate 220 mg twice daily but was initially noncompliant with the topical corticosteroid regimen. He did, however, initiate zinc supplementation, which was later increased to 220 mg 3 times daily. At 3-month follow-up, the lesions had nearly completely cleared (Figure) and the serum zinc level was within reference range at 81 μg/dL.

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatosis that was first described in 1996 by el Darouti and Abu el Ela1 in a series of 7 Egyptian patients. Since then, most of the cases have reported concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Necrolytic acral erythema classically presents with symmetric, well-defined, hyperkeratotic plaques in an acral distribution, typically on the dorsal aspect of the feet.2,3 Lesions may involve the dorsal aspect of the toes and the lower legs, with less common involvement of the elbows, hands, and buttocks. Patients often report pruritus and/or burning.3

Abdallah et al4 proposed several stages of NAE development with erythematous papules with dusky eroded centers progressing to marginated, erythematous to violaceous, lichenified plaques. Over time, these lesions tend to thin with progressive hyperpigmentation.

Histologically, early findings of NAE include acanthosis with epidermal spongiosis and upper dermal perivascular dermatitis. Over time, lesions may exhibit psoriasiform hyperplasia with papillomatosis and parakeratosis, epidermal pallor, subcorneal pustules, vascular ectasia, papillary dermal inflammation, and necrotic keratinocytes. Minimal to moderate acanthosis with an inflammatory infiltrate may be observed later in disease progression.5

The differential diagnosis of NAE includes many benign inflammatory skin diseases. Given the acral/extensor distribution of hyperkeratotic lesions and psoriasiform pattern on histopathology, NAE initially may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis. Unlike psoriasis, however, NAE rarely involves palmoplantar skin or nails4 and may respond dramatically to treatment with zinc supplementation.6,7 Necrolytic acral erythema also may be confused with other necrolytic erythemas, including necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and pellagra. A deficiency of biotin or essential fatty acids also may mimic NAE. Necrolytic acral erythema can be distinguished from these entities based on its characteristic appearance and distribution, along with comorbid HCV infection.2-4

Several reports of NAE have revealed an associated zinc deficiency.2,8 The underlying pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in NAE has not been elucidated but is thought to be related to HCV infection.2 Clinical improvement has been reported with zinc supplementation in patients with NAE at dosages of 220 mg twice daily, even in those with initial serum zinc levels within reference range.6,7 Our patient was observed to have a low serum zinc level that dramatically improved with oral supplementation.

The recognition of this uncommon entity is critical for dermatologists and dermatopathologists, as NAE has been proposed as an early cutaneous marker of HCV and may prompt the initial diagnosis of HCV.1-10 The severity of NAE has even been linked to HCV severity.1,8 Treatment of HCV has cleared NAE in several cases,4,10 implicating the virus in its pathogenesis. A proper workup for liver dysfunction and follow-up with an appropriate health care provider for HCV treatment is crucial. Our patient was encouraged to follow up with the hepatology department, as he had not been evaluated in several years.

- el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-256.

- Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:15.

- Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;83:309-314.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100:354-355.

- Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:755-757.

- Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-87.

- Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, et al. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S108-S110.

- Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921.

- Hivnor CM, Yan AC, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: response to combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S121-S124.

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Acral Erythema

Histopathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen from the right leg revealed an erosion with parakeratosis containing neutrophils and marked spongiosis favoring the upper layer of the epidermis with focal individual necrotic keratinocytes. In addition, there was a lymphocytic and neutrophilic exocytosis with edema of the papillary dermal papillae, mild papillary dermal fibrosis, and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils. Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).

The patient was prescribed clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% and oral zinc sulfate 220 mg twice daily but was initially noncompliant with the topical corticosteroid regimen. He did, however, initiate zinc supplementation, which was later increased to 220 mg 3 times daily. At 3-month follow-up, the lesions had nearly completely cleared (Figure) and the serum zinc level was within reference range at 81 μg/dL.

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatosis that was first described in 1996 by el Darouti and Abu el Ela1 in a series of 7 Egyptian patients. Since then, most of the cases have reported concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Necrolytic acral erythema classically presents with symmetric, well-defined, hyperkeratotic plaques in an acral distribution, typically on the dorsal aspect of the feet.2,3 Lesions may involve the dorsal aspect of the toes and the lower legs, with less common involvement of the elbows, hands, and buttocks. Patients often report pruritus and/or burning.3

Abdallah et al4 proposed several stages of NAE development with erythematous papules with dusky eroded centers progressing to marginated, erythematous to violaceous, lichenified plaques. Over time, these lesions tend to thin with progressive hyperpigmentation.

Histologically, early findings of NAE include acanthosis with epidermal spongiosis and upper dermal perivascular dermatitis. Over time, lesions may exhibit psoriasiform hyperplasia with papillomatosis and parakeratosis, epidermal pallor, subcorneal pustules, vascular ectasia, papillary dermal inflammation, and necrotic keratinocytes. Minimal to moderate acanthosis with an inflammatory infiltrate may be observed later in disease progression.5

The differential diagnosis of NAE includes many benign inflammatory skin diseases. Given the acral/extensor distribution of hyperkeratotic lesions and psoriasiform pattern on histopathology, NAE initially may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis. Unlike psoriasis, however, NAE rarely involves palmoplantar skin or nails4 and may respond dramatically to treatment with zinc supplementation.6,7 Necrolytic acral erythema also may be confused with other necrolytic erythemas, including necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and pellagra. A deficiency of biotin or essential fatty acids also may mimic NAE. Necrolytic acral erythema can be distinguished from these entities based on its characteristic appearance and distribution, along with comorbid HCV infection.2-4

Several reports of NAE have revealed an associated zinc deficiency.2,8 The underlying pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in NAE has not been elucidated but is thought to be related to HCV infection.2 Clinical improvement has been reported with zinc supplementation in patients with NAE at dosages of 220 mg twice daily, even in those with initial serum zinc levels within reference range.6,7 Our patient was observed to have a low serum zinc level that dramatically improved with oral supplementation.

The recognition of this uncommon entity is critical for dermatologists and dermatopathologists, as NAE has been proposed as an early cutaneous marker of HCV and may prompt the initial diagnosis of HCV.1-10 The severity of NAE has even been linked to HCV severity.1,8 Treatment of HCV has cleared NAE in several cases,4,10 implicating the virus in its pathogenesis. A proper workup for liver dysfunction and follow-up with an appropriate health care provider for HCV treatment is crucial. Our patient was encouraged to follow up with the hepatology department, as he had not been evaluated in several years.

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Acral Erythema

Histopathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen from the right leg revealed an erosion with parakeratosis containing neutrophils and marked spongiosis favoring the upper layer of the epidermis with focal individual necrotic keratinocytes. In addition, there was a lymphocytic and neutrophilic exocytosis with edema of the papillary dermal papillae, mild papillary dermal fibrosis, and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils. Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).

The patient was prescribed clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% and oral zinc sulfate 220 mg twice daily but was initially noncompliant with the topical corticosteroid regimen. He did, however, initiate zinc supplementation, which was later increased to 220 mg 3 times daily. At 3-month follow-up, the lesions had nearly completely cleared (Figure) and the serum zinc level was within reference range at 81 μg/dL.

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatosis that was first described in 1996 by el Darouti and Abu el Ela1 in a series of 7 Egyptian patients. Since then, most of the cases have reported concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Necrolytic acral erythema classically presents with symmetric, well-defined, hyperkeratotic plaques in an acral distribution, typically on the dorsal aspect of the feet.2,3 Lesions may involve the dorsal aspect of the toes and the lower legs, with less common involvement of the elbows, hands, and buttocks. Patients often report pruritus and/or burning.3

Abdallah et al4 proposed several stages of NAE development with erythematous papules with dusky eroded centers progressing to marginated, erythematous to violaceous, lichenified plaques. Over time, these lesions tend to thin with progressive hyperpigmentation.

Histologically, early findings of NAE include acanthosis with epidermal spongiosis and upper dermal perivascular dermatitis. Over time, lesions may exhibit psoriasiform hyperplasia with papillomatosis and parakeratosis, epidermal pallor, subcorneal pustules, vascular ectasia, papillary dermal inflammation, and necrotic keratinocytes. Minimal to moderate acanthosis with an inflammatory infiltrate may be observed later in disease progression.5

The differential diagnosis of NAE includes many benign inflammatory skin diseases. Given the acral/extensor distribution of hyperkeratotic lesions and psoriasiform pattern on histopathology, NAE initially may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis. Unlike psoriasis, however, NAE rarely involves palmoplantar skin or nails4 and may respond dramatically to treatment with zinc supplementation.6,7 Necrolytic acral erythema also may be confused with other necrolytic erythemas, including necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and pellagra. A deficiency of biotin or essential fatty acids also may mimic NAE. Necrolytic acral erythema can be distinguished from these entities based on its characteristic appearance and distribution, along with comorbid HCV infection.2-4

Several reports of NAE have revealed an associated zinc deficiency.2,8 The underlying pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in NAE has not been elucidated but is thought to be related to HCV infection.2 Clinical improvement has been reported with zinc supplementation in patients with NAE at dosages of 220 mg twice daily, even in those with initial serum zinc levels within reference range.6,7 Our patient was observed to have a low serum zinc level that dramatically improved with oral supplementation.

The recognition of this uncommon entity is critical for dermatologists and dermatopathologists, as NAE has been proposed as an early cutaneous marker of HCV and may prompt the initial diagnosis of HCV.1-10 The severity of NAE has even been linked to HCV severity.1,8 Treatment of HCV has cleared NAE in several cases,4,10 implicating the virus in its pathogenesis. A proper workup for liver dysfunction and follow-up with an appropriate health care provider for HCV treatment is crucial. Our patient was encouraged to follow up with the hepatology department, as he had not been evaluated in several years.

- el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-256.

- Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:15.

- Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;83:309-314.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100:354-355.

- Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:755-757.

- Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-87.

- Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, et al. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S108-S110.

- Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921.

- Hivnor CM, Yan AC, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: response to combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S121-S124.

- el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-256.

- Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:15.

- Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;83:309-314.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100:354-355.

- Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:755-757.

- Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-87.

- Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, et al. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S108-S110.

- Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921.

- Hivnor CM, Yan AC, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: response to combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S121-S124.

The Arthroscopic Superior Capsular Reconstruction

Rotator cuff tears are very common, and 250,000 to 500,000 rotator cuff repairs are performed in the United States each year.1,2 In most cases, a complete repair of even large or massive tears can be achieved. However, a subset of patients exist in whom the glenohumeral joint has minimal degenerative changes and the rotator cuff tendon is either irreparable or very poor quality and unlikely to heal (ie, failed previous cuff repair). Some authors have advocated for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) in these patients despite the lack of glenohumeral arthritis. However, due to the permanent destruction of the glenohumeral articular surfaces, complication rates, and concerns about implant longevity with RSA, we believe the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) is a viable alternative in patients in whom joint preservation is appropriate based on age limitations and/or activity requirements.3

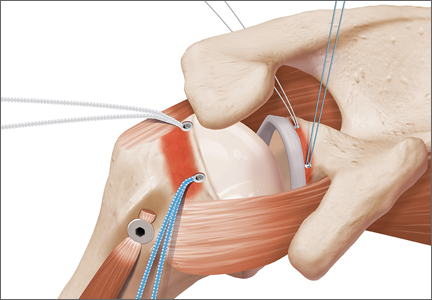

The SCR was first described by Mihata and colleagues4 as a means to reconstruct the superior capsule in shoulders with large, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Originally described using a fascia lata autograft, our technique has been adapted to incorporate a dermal allograft, which limits donor site morbidity and operative time. In most cases, the dermal allograft is fixed to the normal anatomic attachments of the superior glenoid just medial to the superior labrum, laterally to the greater tuberosity, and posteriorly with side-to-side sutures to the remaining rotator cuff. If there is a robust band of “comma” tissue anteriorly, we fix the anterior margin of the dermal graft to this with side-to-side sutures. The comma tissue represents the medial sling of the biceps tendon and connects the upper subscapularis tendon to the anterior supraspinatus. In most cases, this tissue is intact after repair of the subscapularis tendon.

Technique

The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The arm is positioned in 20° to 30° of abduction and 20° to 30° of forward flexion. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. The subscapularis is visualized and repaired if torn. A biceps tenodesis is performed in most cases, as there is often a tear of the subscapularis, tear or instability of the biceps tendon, and/or a compromised attachment of the biceps root.

Attention is turned to the subacromial space. Posterior viewing and lateral working portals are established. A 10-mm flexible cannula (PassPort; Arthrex) is placed in the lateral portal to aid with suture management and graft passage. A limited subacromial decompression is performed that preserves the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff is carefully dissected and freed from the internal deltoid fascia. The scapular spine is identified to visualize the raphé between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The infraspinatus is mobilized and repaired as much as possible.

If we think that the tear might be reparable by gaining added excursion from a posterior interval slide, or if it is clearly not reparable but the remaining rim of rotator cuff obscures clear visualization of the superior glenoid, we perform a posterior interval slide. If the additional excursion that is achieved by the posterior slide is adequate for a complete repair, we proceed with the repair. However, if the tear is not reparable even after the posterior interval slide, we have found that the exposure and preparation of the superior glenoid is greatly improved after the posterior slide. After fixation of the dermal graft, we typically perform a partial side-to-side repair of the supraspinatus to the infraspinatus over the top of the graft.

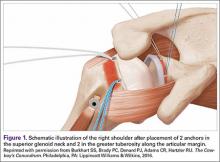

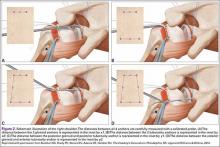

The bone beds of the greater tuberosity and just medial to the superior glenoid labrum are prepared with a shaver and motorized burr. Two anchors (3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak; Arthrex) are placed in the superior glenoid neck at about the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions approximately 5 mm medial to the superior labrum. Note: the placement medial to the labrum is chosen because this is the normal origin of the superior capsule and because of the angle of approach, these percutaneous portals are often more medial than typical portals for placing anchors during SLAP (superior labral anterior to posterior) repair. Next, 2 threaded anchors (4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock; Arthrex) preloaded with suture tape are placed in the greater tuberosity along the articular margin (Figure 1). However, if a biceps tenodesis with an interference screw is placed at the top of the bicipital groove, this anchor preloaded with suture tape can also serve as the anteromedial anchor in the greater tuberosity footprint. The distances between all 4 anchors are carefully measured with a calibrated probe (Figures 2A-2D).

We use a 3.0-mm acellular dermal allograft (ArthroFlex; Arthrex) to reconstruct the superior capsule. The positions of the 4 anchors are carefully marked on the dermal allograft. We routinely add an additional 5 mm of tissue to the medial, anterior, and posterior margins to decrease the risk of suture cut out. An additional 10 mm of tissue is added laterally to cover the greater tuberosity. The final contoured graft is typically trapezoidal in shape.

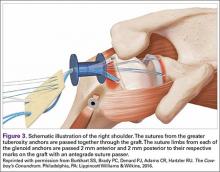

The sutures from the 4 anchors are then sequentially retrieved through the lateral cannula. The sutures from the greater tuberosity anchors are passed through their respective holes in the graft. However, the suture limbs from each of the glenoid anchors are individually passed 2 mm anterior and 2 mm posterior to their respective marks on the graft with an antegrade suture passer (Figure 3). It is important to have an assistant apply tension to each of the sutures after they are passed through the graft to decrease the chance of crossing and tangling the sutures.

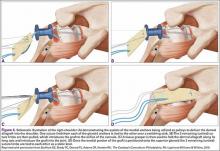

The eyelets of the medial anchors are utilized as pulleys to deliver the dermal allograft into the shoulder. One suture limb from each of the glenoid anchors is tied to the other over a switching stick (Figure 4A). The 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are then pulled, which introduces the graft to the orifice of the cannula (Figure 4B). A tissue grasper is then used to fold the dermal allograft along its long axis and introduce the graft into the joint (Figure 4C). Once the medial portion of the graft is positioned onto the superior glenoid the 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are tied to each other as a static knot in the subacromial space (Figure 4D).

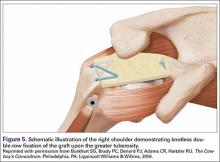

The redundancy in the suture tapes can be removed by sequentially sliding a retriever down each suture and tensioning the suture as the nose of the instrument pushes the dermal graft down to the tuberosity bone bed. The suture tapes are crisscrossed and secured laterally with 2 additional knotless threaded anchors (Figure 5). One may also place cinch stitches at the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the graft that are incorporated into the lateral anchors. These sutures can be useful for pulling the graft back out of the subacromial space in the event of any suture tangles, and can be used for controlling the lateral aspect of the graft during lateral anchor placement.

At this point in the procedure, additional glenoid anchors can be placed both anterior and posterior to the superior glenoid anchors if additional glenoid fixation is desired. Finally, 2 to 3 side-to-side sutures are placed posteriorly attaching the anterior aspect of the infraspinatus to the posterior aspect of the dermal allograft (Figures 6A-6C). If rotator interval tissue (comma tissue) is present, anterior side-to-side sutures may be placed. However, we do not recommend placing anterior side-to-side sutures directly from the dermal allograft to the subscapularis as this may deform the graft, over- constrain the shoulder, and restrict motion.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the superior capsule has been shown to restore the normal restraint to superior translation of the humeral head and reestablish a stable fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.5 It should be mentioned that we do not perform the SCR in patients with advanced glenohumeral arthritis. The short-term results of this novel procedure have been encouraging, including our own series of patients, in which most patients have had a significant reduction in pain, improvement in function, and very few complications (P. J. Denard, MD, S. S. Burkhart, MD, P. C. Brady, MD, J. Tokish, MD, C. R. Adams, MD, unpublished data, May 2016).

The early success of this procedure suggests that a robust superior capsule is necessary, in addition to functional muscle-tendon units, to restore the stable fulcrum and force couples that are necessary for normal shoulder function. Perhaps we have not paid enough attention to the integrity of the superior capsule in the past. In cases of revision cuff repair, we pay special attention to the quality of the capsular layer deep to the cuff tendon. If the capsule is poor quality, we sometimes reconstruct the capsule with a dermal allograft (SCR) and then do a rotator cuff repair (partial or complete) over the top of the SCR to maintain the normal anatomic deep to superficial layering of the capsule and rotator cuff.

We are very conservative with our postoperative rehabilitation program after a SCR. We know that the rate of stiffness with a conservative program after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, even in the revision setting, is very low.6 Furthermore, both basic science on healing of soft tissue to bone and radiographic analysis of healing after postoperative rotator cuff repairs support a slow rehabilitation program.7,8 A canine model specifically evaluating acellular dermal allografts in the shoulder suggests that these grafts undergo significant remodeling and become weaker before they get stronger.9 We would rather err on the side of healing of the SCR with potentially a slight increase in the rate of shoulder stiffness than to regain early motion at the expense of graft failure. Therefore, we have the patient wear a sling with no shoulder motion for 6 weeks. Passive motion is started at 6 weeks postoperative and strengthening is delayed until 12 to 16 weeks postoperative.

1. Orr SB, Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, et al. Aligned multilayered electrospun scaffolds for rotator cuff tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:117-126.

2. Austin L, Black EM, Lombardi NJ, Pepe MD, Lazarus M. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. A prospective study on cost savings, surgical time, and outcomes. Ortho J Sports Med. 2015;3(2 Suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967115S00156.

3. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214-1219.

4. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

5. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

6. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, Vadala AP, Arrigoni P, Burkhart SS. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):880-890.

7. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological evaluation of repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):586-594.

8. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):34-42.

9. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

Rotator cuff tears are very common, and 250,000 to 500,000 rotator cuff repairs are performed in the United States each year.1,2 In most cases, a complete repair of even large or massive tears can be achieved. However, a subset of patients exist in whom the glenohumeral joint has minimal degenerative changes and the rotator cuff tendon is either irreparable or very poor quality and unlikely to heal (ie, failed previous cuff repair). Some authors have advocated for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) in these patients despite the lack of glenohumeral arthritis. However, due to the permanent destruction of the glenohumeral articular surfaces, complication rates, and concerns about implant longevity with RSA, we believe the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) is a viable alternative in patients in whom joint preservation is appropriate based on age limitations and/or activity requirements.3

The SCR was first described by Mihata and colleagues4 as a means to reconstruct the superior capsule in shoulders with large, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Originally described using a fascia lata autograft, our technique has been adapted to incorporate a dermal allograft, which limits donor site morbidity and operative time. In most cases, the dermal allograft is fixed to the normal anatomic attachments of the superior glenoid just medial to the superior labrum, laterally to the greater tuberosity, and posteriorly with side-to-side sutures to the remaining rotator cuff. If there is a robust band of “comma” tissue anteriorly, we fix the anterior margin of the dermal graft to this with side-to-side sutures. The comma tissue represents the medial sling of the biceps tendon and connects the upper subscapularis tendon to the anterior supraspinatus. In most cases, this tissue is intact after repair of the subscapularis tendon.

Technique

The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The arm is positioned in 20° to 30° of abduction and 20° to 30° of forward flexion. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. The subscapularis is visualized and repaired if torn. A biceps tenodesis is performed in most cases, as there is often a tear of the subscapularis, tear or instability of the biceps tendon, and/or a compromised attachment of the biceps root.

Attention is turned to the subacromial space. Posterior viewing and lateral working portals are established. A 10-mm flexible cannula (PassPort; Arthrex) is placed in the lateral portal to aid with suture management and graft passage. A limited subacromial decompression is performed that preserves the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff is carefully dissected and freed from the internal deltoid fascia. The scapular spine is identified to visualize the raphé between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The infraspinatus is mobilized and repaired as much as possible.

If we think that the tear might be reparable by gaining added excursion from a posterior interval slide, or if it is clearly not reparable but the remaining rim of rotator cuff obscures clear visualization of the superior glenoid, we perform a posterior interval slide. If the additional excursion that is achieved by the posterior slide is adequate for a complete repair, we proceed with the repair. However, if the tear is not reparable even after the posterior interval slide, we have found that the exposure and preparation of the superior glenoid is greatly improved after the posterior slide. After fixation of the dermal graft, we typically perform a partial side-to-side repair of the supraspinatus to the infraspinatus over the top of the graft.

The bone beds of the greater tuberosity and just medial to the superior glenoid labrum are prepared with a shaver and motorized burr. Two anchors (3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak; Arthrex) are placed in the superior glenoid neck at about the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions approximately 5 mm medial to the superior labrum. Note: the placement medial to the labrum is chosen because this is the normal origin of the superior capsule and because of the angle of approach, these percutaneous portals are often more medial than typical portals for placing anchors during SLAP (superior labral anterior to posterior) repair. Next, 2 threaded anchors (4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock; Arthrex) preloaded with suture tape are placed in the greater tuberosity along the articular margin (Figure 1). However, if a biceps tenodesis with an interference screw is placed at the top of the bicipital groove, this anchor preloaded with suture tape can also serve as the anteromedial anchor in the greater tuberosity footprint. The distances between all 4 anchors are carefully measured with a calibrated probe (Figures 2A-2D).

We use a 3.0-mm acellular dermal allograft (ArthroFlex; Arthrex) to reconstruct the superior capsule. The positions of the 4 anchors are carefully marked on the dermal allograft. We routinely add an additional 5 mm of tissue to the medial, anterior, and posterior margins to decrease the risk of suture cut out. An additional 10 mm of tissue is added laterally to cover the greater tuberosity. The final contoured graft is typically trapezoidal in shape.

The sutures from the 4 anchors are then sequentially retrieved through the lateral cannula. The sutures from the greater tuberosity anchors are passed through their respective holes in the graft. However, the suture limbs from each of the glenoid anchors are individually passed 2 mm anterior and 2 mm posterior to their respective marks on the graft with an antegrade suture passer (Figure 3). It is important to have an assistant apply tension to each of the sutures after they are passed through the graft to decrease the chance of crossing and tangling the sutures.

The eyelets of the medial anchors are utilized as pulleys to deliver the dermal allograft into the shoulder. One suture limb from each of the glenoid anchors is tied to the other over a switching stick (Figure 4A). The 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are then pulled, which introduces the graft to the orifice of the cannula (Figure 4B). A tissue grasper is then used to fold the dermal allograft along its long axis and introduce the graft into the joint (Figure 4C). Once the medial portion of the graft is positioned onto the superior glenoid the 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are tied to each other as a static knot in the subacromial space (Figure 4D).

The redundancy in the suture tapes can be removed by sequentially sliding a retriever down each suture and tensioning the suture as the nose of the instrument pushes the dermal graft down to the tuberosity bone bed. The suture tapes are crisscrossed and secured laterally with 2 additional knotless threaded anchors (Figure 5). One may also place cinch stitches at the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the graft that are incorporated into the lateral anchors. These sutures can be useful for pulling the graft back out of the subacromial space in the event of any suture tangles, and can be used for controlling the lateral aspect of the graft during lateral anchor placement.

At this point in the procedure, additional glenoid anchors can be placed both anterior and posterior to the superior glenoid anchors if additional glenoid fixation is desired. Finally, 2 to 3 side-to-side sutures are placed posteriorly attaching the anterior aspect of the infraspinatus to the posterior aspect of the dermal allograft (Figures 6A-6C). If rotator interval tissue (comma tissue) is present, anterior side-to-side sutures may be placed. However, we do not recommend placing anterior side-to-side sutures directly from the dermal allograft to the subscapularis as this may deform the graft, over- constrain the shoulder, and restrict motion.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the superior capsule has been shown to restore the normal restraint to superior translation of the humeral head and reestablish a stable fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.5 It should be mentioned that we do not perform the SCR in patients with advanced glenohumeral arthritis. The short-term results of this novel procedure have been encouraging, including our own series of patients, in which most patients have had a significant reduction in pain, improvement in function, and very few complications (P. J. Denard, MD, S. S. Burkhart, MD, P. C. Brady, MD, J. Tokish, MD, C. R. Adams, MD, unpublished data, May 2016).

The early success of this procedure suggests that a robust superior capsule is necessary, in addition to functional muscle-tendon units, to restore the stable fulcrum and force couples that are necessary for normal shoulder function. Perhaps we have not paid enough attention to the integrity of the superior capsule in the past. In cases of revision cuff repair, we pay special attention to the quality of the capsular layer deep to the cuff tendon. If the capsule is poor quality, we sometimes reconstruct the capsule with a dermal allograft (SCR) and then do a rotator cuff repair (partial or complete) over the top of the SCR to maintain the normal anatomic deep to superficial layering of the capsule and rotator cuff.

We are very conservative with our postoperative rehabilitation program after a SCR. We know that the rate of stiffness with a conservative program after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, even in the revision setting, is very low.6 Furthermore, both basic science on healing of soft tissue to bone and radiographic analysis of healing after postoperative rotator cuff repairs support a slow rehabilitation program.7,8 A canine model specifically evaluating acellular dermal allografts in the shoulder suggests that these grafts undergo significant remodeling and become weaker before they get stronger.9 We would rather err on the side of healing of the SCR with potentially a slight increase in the rate of shoulder stiffness than to regain early motion at the expense of graft failure. Therefore, we have the patient wear a sling with no shoulder motion for 6 weeks. Passive motion is started at 6 weeks postoperative and strengthening is delayed until 12 to 16 weeks postoperative.

Rotator cuff tears are very common, and 250,000 to 500,000 rotator cuff repairs are performed in the United States each year.1,2 In most cases, a complete repair of even large or massive tears can be achieved. However, a subset of patients exist in whom the glenohumeral joint has minimal degenerative changes and the rotator cuff tendon is either irreparable or very poor quality and unlikely to heal (ie, failed previous cuff repair). Some authors have advocated for reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) in these patients despite the lack of glenohumeral arthritis. However, due to the permanent destruction of the glenohumeral articular surfaces, complication rates, and concerns about implant longevity with RSA, we believe the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) is a viable alternative in patients in whom joint preservation is appropriate based on age limitations and/or activity requirements.3

The SCR was first described by Mihata and colleagues4 as a means to reconstruct the superior capsule in shoulders with large, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Originally described using a fascia lata autograft, our technique has been adapted to incorporate a dermal allograft, which limits donor site morbidity and operative time. In most cases, the dermal allograft is fixed to the normal anatomic attachments of the superior glenoid just medial to the superior labrum, laterally to the greater tuberosity, and posteriorly with side-to-side sutures to the remaining rotator cuff. If there is a robust band of “comma” tissue anteriorly, we fix the anterior margin of the dermal graft to this with side-to-side sutures. The comma tissue represents the medial sling of the biceps tendon and connects the upper subscapularis tendon to the anterior supraspinatus. In most cases, this tissue is intact after repair of the subscapularis tendon.

Technique

The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The arm is positioned in 20° to 30° of abduction and 20° to 30° of forward flexion. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. The subscapularis is visualized and repaired if torn. A biceps tenodesis is performed in most cases, as there is often a tear of the subscapularis, tear or instability of the biceps tendon, and/or a compromised attachment of the biceps root.

Attention is turned to the subacromial space. Posterior viewing and lateral working portals are established. A 10-mm flexible cannula (PassPort; Arthrex) is placed in the lateral portal to aid with suture management and graft passage. A limited subacromial decompression is performed that preserves the coracoacromial arch. The rotator cuff is carefully dissected and freed from the internal deltoid fascia. The scapular spine is identified to visualize the raphé between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The infraspinatus is mobilized and repaired as much as possible.

If we think that the tear might be reparable by gaining added excursion from a posterior interval slide, or if it is clearly not reparable but the remaining rim of rotator cuff obscures clear visualization of the superior glenoid, we perform a posterior interval slide. If the additional excursion that is achieved by the posterior slide is adequate for a complete repair, we proceed with the repair. However, if the tear is not reparable even after the posterior interval slide, we have found that the exposure and preparation of the superior glenoid is greatly improved after the posterior slide. After fixation of the dermal graft, we typically perform a partial side-to-side repair of the supraspinatus to the infraspinatus over the top of the graft.

The bone beds of the greater tuberosity and just medial to the superior glenoid labrum are prepared with a shaver and motorized burr. Two anchors (3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak; Arthrex) are placed in the superior glenoid neck at about the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock positions approximately 5 mm medial to the superior labrum. Note: the placement medial to the labrum is chosen because this is the normal origin of the superior capsule and because of the angle of approach, these percutaneous portals are often more medial than typical portals for placing anchors during SLAP (superior labral anterior to posterior) repair. Next, 2 threaded anchors (4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock; Arthrex) preloaded with suture tape are placed in the greater tuberosity along the articular margin (Figure 1). However, if a biceps tenodesis with an interference screw is placed at the top of the bicipital groove, this anchor preloaded with suture tape can also serve as the anteromedial anchor in the greater tuberosity footprint. The distances between all 4 anchors are carefully measured with a calibrated probe (Figures 2A-2D).

We use a 3.0-mm acellular dermal allograft (ArthroFlex; Arthrex) to reconstruct the superior capsule. The positions of the 4 anchors are carefully marked on the dermal allograft. We routinely add an additional 5 mm of tissue to the medial, anterior, and posterior margins to decrease the risk of suture cut out. An additional 10 mm of tissue is added laterally to cover the greater tuberosity. The final contoured graft is typically trapezoidal in shape.

The sutures from the 4 anchors are then sequentially retrieved through the lateral cannula. The sutures from the greater tuberosity anchors are passed through their respective holes in the graft. However, the suture limbs from each of the glenoid anchors are individually passed 2 mm anterior and 2 mm posterior to their respective marks on the graft with an antegrade suture passer (Figure 3). It is important to have an assistant apply tension to each of the sutures after they are passed through the graft to decrease the chance of crossing and tangling the sutures.

The eyelets of the medial anchors are utilized as pulleys to deliver the dermal allograft into the shoulder. One suture limb from each of the glenoid anchors is tied to the other over a switching stick (Figure 4A). The 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are then pulled, which introduces the graft to the orifice of the cannula (Figure 4B). A tissue grasper is then used to fold the dermal allograft along its long axis and introduce the graft into the joint (Figure 4C). Once the medial portion of the graft is positioned onto the superior glenoid the 2 remaining (untied) suture limbs are tied to each other as a static knot in the subacromial space (Figure 4D).

The redundancy in the suture tapes can be removed by sequentially sliding a retriever down each suture and tensioning the suture as the nose of the instrument pushes the dermal graft down to the tuberosity bone bed. The suture tapes are crisscrossed and secured laterally with 2 additional knotless threaded anchors (Figure 5). One may also place cinch stitches at the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the graft that are incorporated into the lateral anchors. These sutures can be useful for pulling the graft back out of the subacromial space in the event of any suture tangles, and can be used for controlling the lateral aspect of the graft during lateral anchor placement.

At this point in the procedure, additional glenoid anchors can be placed both anterior and posterior to the superior glenoid anchors if additional glenoid fixation is desired. Finally, 2 to 3 side-to-side sutures are placed posteriorly attaching the anterior aspect of the infraspinatus to the posterior aspect of the dermal allograft (Figures 6A-6C). If rotator interval tissue (comma tissue) is present, anterior side-to-side sutures may be placed. However, we do not recommend placing anterior side-to-side sutures directly from the dermal allograft to the subscapularis as this may deform the graft, over- constrain the shoulder, and restrict motion.

Discussion

Reconstruction of the superior capsule has been shown to restore the normal restraint to superior translation of the humeral head and reestablish a stable fulcrum at the glenohumeral joint.5 It should be mentioned that we do not perform the SCR in patients with advanced glenohumeral arthritis. The short-term results of this novel procedure have been encouraging, including our own series of patients, in which most patients have had a significant reduction in pain, improvement in function, and very few complications (P. J. Denard, MD, S. S. Burkhart, MD, P. C. Brady, MD, J. Tokish, MD, C. R. Adams, MD, unpublished data, May 2016).

The early success of this procedure suggests that a robust superior capsule is necessary, in addition to functional muscle-tendon units, to restore the stable fulcrum and force couples that are necessary for normal shoulder function. Perhaps we have not paid enough attention to the integrity of the superior capsule in the past. In cases of revision cuff repair, we pay special attention to the quality of the capsular layer deep to the cuff tendon. If the capsule is poor quality, we sometimes reconstruct the capsule with a dermal allograft (SCR) and then do a rotator cuff repair (partial or complete) over the top of the SCR to maintain the normal anatomic deep to superficial layering of the capsule and rotator cuff.

We are very conservative with our postoperative rehabilitation program after a SCR. We know that the rate of stiffness with a conservative program after an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, even in the revision setting, is very low.6 Furthermore, both basic science on healing of soft tissue to bone and radiographic analysis of healing after postoperative rotator cuff repairs support a slow rehabilitation program.7,8 A canine model specifically evaluating acellular dermal allografts in the shoulder suggests that these grafts undergo significant remodeling and become weaker before they get stronger.9 We would rather err on the side of healing of the SCR with potentially a slight increase in the rate of shoulder stiffness than to regain early motion at the expense of graft failure. Therefore, we have the patient wear a sling with no shoulder motion for 6 weeks. Passive motion is started at 6 weeks postoperative and strengthening is delayed until 12 to 16 weeks postoperative.

1. Orr SB, Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, et al. Aligned multilayered electrospun scaffolds for rotator cuff tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:117-126.

2. Austin L, Black EM, Lombardi NJ, Pepe MD, Lazarus M. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. A prospective study on cost savings, surgical time, and outcomes. Ortho J Sports Med. 2015;3(2 Suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967115S00156.

3. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214-1219.

4. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

5. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

6. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, Vadala AP, Arrigoni P, Burkhart SS. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):880-890.

7. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological evaluation of repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):586-594.

8. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):34-42.

9. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

1. Orr SB, Chainani A, Hippensteel KJ, et al. Aligned multilayered electrospun scaffolds for rotator cuff tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015;24:117-126.

2. Austin L, Black EM, Lombardi NJ, Pepe MD, Lazarus M. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. A prospective study on cost savings, surgical time, and outcomes. Ortho J Sports Med. 2015;3(2 Suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967115S00156.

3. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(9):1214-1219.

4. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

5. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

6. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, Vadala AP, Arrigoni P, Burkhart SS. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):880-890.

7. Sonnabend DH, Howlett CR, Young AA. Histological evaluation of repair of the rotator cuff in a primate model. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):586-594.

8. Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: aggressive versus limited early passive exercises. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):34-42.

9. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JS Jr, An KN, Steinmann SP. Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(7):700-709.

Escitalopram falls short in patients with heart failure and depression

Using escitalopram for patients with chronic heart failure and depression for more than 18 months neither significantly reduces mortality or hospitalization, nor improves depression, a study published June 28 involving 372 patients shows.

“To our knowledge, this study was the first to investigate the composite all-cause mortality and hospitalization in a population with heart failure treated with escitalopram,” wrote Dr. Christiane E. Angermann and her associates.

They said the only other randomized trial evaluating selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in patients with heart failure was the Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure study, which found that sertraline did not improve depression or cardiovascular status. But the treatment duration in that study was only 12 weeks, reported Dr. Angermann of the Cardiology and Comprehensive Heart Failure Center, Würzburg, Germany.

The current study, called the Effects of Selective Serotonin Re-Uptake Inhibition on Morbidity, Mortality, and Mood in Depressed Heart Failure Patients, was a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial conducted at 16 tertiary medical centers in Germany. Three hundred seventy-two patients (185 in the escitalopram group and 187 in the placebo group) were randomized and given at least one dose of the study medication. The study was supposed to last for 24 months, but the investigators stopped it early.

Primary outcome of death or hospitalization occurred in 116 (63%) patients and 119 (64%) patients, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.76-1.27; P = .92).

Read more of the study and findings on the JAMA website (doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7635).

Using escitalopram for patients with chronic heart failure and depression for more than 18 months neither significantly reduces mortality or hospitalization, nor improves depression, a study published June 28 involving 372 patients shows.

“To our knowledge, this study was the first to investigate the composite all-cause mortality and hospitalization in a population with heart failure treated with escitalopram,” wrote Dr. Christiane E. Angermann and her associates.

They said the only other randomized trial evaluating selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in patients with heart failure was the Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure study, which found that sertraline did not improve depression or cardiovascular status. But the treatment duration in that study was only 12 weeks, reported Dr. Angermann of the Cardiology and Comprehensive Heart Failure Center, Würzburg, Germany.

The current study, called the Effects of Selective Serotonin Re-Uptake Inhibition on Morbidity, Mortality, and Mood in Depressed Heart Failure Patients, was a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial conducted at 16 tertiary medical centers in Germany. Three hundred seventy-two patients (185 in the escitalopram group and 187 in the placebo group) were randomized and given at least one dose of the study medication. The study was supposed to last for 24 months, but the investigators stopped it early.

Primary outcome of death or hospitalization occurred in 116 (63%) patients and 119 (64%) patients, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.76-1.27; P = .92).

Read more of the study and findings on the JAMA website (doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7635).

Using escitalopram for patients with chronic heart failure and depression for more than 18 months neither significantly reduces mortality or hospitalization, nor improves depression, a study published June 28 involving 372 patients shows.

“To our knowledge, this study was the first to investigate the composite all-cause mortality and hospitalization in a population with heart failure treated with escitalopram,” wrote Dr. Christiane E. Angermann and her associates.

They said the only other randomized trial evaluating selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in patients with heart failure was the Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure study, which found that sertraline did not improve depression or cardiovascular status. But the treatment duration in that study was only 12 weeks, reported Dr. Angermann of the Cardiology and Comprehensive Heart Failure Center, Würzburg, Germany.

The current study, called the Effects of Selective Serotonin Re-Uptake Inhibition on Morbidity, Mortality, and Mood in Depressed Heart Failure Patients, was a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial conducted at 16 tertiary medical centers in Germany. Three hundred seventy-two patients (185 in the escitalopram group and 187 in the placebo group) were randomized and given at least one dose of the study medication. The study was supposed to last for 24 months, but the investigators stopped it early.

Primary outcome of death or hospitalization occurred in 116 (63%) patients and 119 (64%) patients, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.76-1.27; P = .92).

Read more of the study and findings on the JAMA website (doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7635).

FROM JAMA

Product News: 07 2016

Carmex Grant

Carma Labs Inc, the maker of Carmex lip balms, announced a $10,000 grant program to support an entrepreneur with an Unstoppable Dream. Participants can enter through Facebook or Instagram by posting a 30-second video depicting their aspiration related to a business or product. All entries must include the hashtags #InPursuitOf and #Contest to be considered. Entries can be submitted through July 15, and a winner will be selected and announced in August. For more information, visit www.mycarmex.com.

Juvéderm Volbella XC

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval to market Juvéderm Volbella XC for lip augmentation and for correction of perioral lines in adults older than 21 years. Juvéderm Volbella XC increases lip fullness and softens the appearance of lines around the mouth. It is formulated with Vycross, a proprietary filler technology that contributes to the product’s smoothness. Juvéderm Volbella XC has been customized with a lower hyaluronic acid concentration (15 mg/mL), while still providing the long-lasting results of other Juvéderm products. It will be available to patients in the United States in October 2016. For more information, visit www.juvederm.com.

Teflaro

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of a supplemental new drug application for Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) to expand the label to include the treatment of children aged 2 months to less than 18 years with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) including infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) caused by Staphylococcus pneumoniae and other designated susceptible bacteria. Teflaro is a bactericidal cephalosporin with activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Teflaro is already approved for ABSSSI and CABP in adult patients. For more information, visit www.teflaro.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Carmex Grant

Carma Labs Inc, the maker of Carmex lip balms, announced a $10,000 grant program to support an entrepreneur with an Unstoppable Dream. Participants can enter through Facebook or Instagram by posting a 30-second video depicting their aspiration related to a business or product. All entries must include the hashtags #InPursuitOf and #Contest to be considered. Entries can be submitted through July 15, and a winner will be selected and announced in August. For more information, visit www.mycarmex.com.

Juvéderm Volbella XC

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval to market Juvéderm Volbella XC for lip augmentation and for correction of perioral lines in adults older than 21 years. Juvéderm Volbella XC increases lip fullness and softens the appearance of lines around the mouth. It is formulated with Vycross, a proprietary filler technology that contributes to the product’s smoothness. Juvéderm Volbella XC has been customized with a lower hyaluronic acid concentration (15 mg/mL), while still providing the long-lasting results of other Juvéderm products. It will be available to patients in the United States in October 2016. For more information, visit www.juvederm.com.

Teflaro

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of a supplemental new drug application for Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) to expand the label to include the treatment of children aged 2 months to less than 18 years with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) including infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) caused by Staphylococcus pneumoniae and other designated susceptible bacteria. Teflaro is a bactericidal cephalosporin with activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Teflaro is already approved for ABSSSI and CABP in adult patients. For more information, visit www.teflaro.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Carmex Grant

Carma Labs Inc, the maker of Carmex lip balms, announced a $10,000 grant program to support an entrepreneur with an Unstoppable Dream. Participants can enter through Facebook or Instagram by posting a 30-second video depicting their aspiration related to a business or product. All entries must include the hashtags #InPursuitOf and #Contest to be considered. Entries can be submitted through July 15, and a winner will be selected and announced in August. For more information, visit www.mycarmex.com.

Juvéderm Volbella XC

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval to market Juvéderm Volbella XC for lip augmentation and for correction of perioral lines in adults older than 21 years. Juvéderm Volbella XC increases lip fullness and softens the appearance of lines around the mouth. It is formulated with Vycross, a proprietary filler technology that contributes to the product’s smoothness. Juvéderm Volbella XC has been customized with a lower hyaluronic acid concentration (15 mg/mL), while still providing the long-lasting results of other Juvéderm products. It will be available to patients in the United States in October 2016. For more information, visit www.juvederm.com.

Teflaro

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of a supplemental new drug application for Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) to expand the label to include the treatment of children aged 2 months to less than 18 years with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) including infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) caused by Staphylococcus pneumoniae and other designated susceptible bacteria. Teflaro is a bactericidal cephalosporin with activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Teflaro is already approved for ABSSSI and CABP in adult patients. For more information, visit www.teflaro.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Clinical Guidelines: Update in acne treatment

Acne affects 85% of teenagers but can frequently persist into adulthood. It causes significant physical and psychological effects for patients including facial scarring, depression, and decreased self-esteem. The initial approach to acne is determined according to presenting severity, emphasizing topical treatment for milder disease and the addition of oral therapy as disease becomes more severe.

Treatment of mild acne can begin with either benzoyl peroxide (BP) or a topical retinoid (TR). Another option for slightly more severe acne is to start with the initially suggested treatment for moderately severe acne, which is topical combination therapy with BP plus a topical antibiotic; TR plus BP; or TR plus BP in combination with a topical antibiotic. Combination therapy can be given either with separate application of the different medicines or by using fixed combination products that include the separate components in one formulation.

BP is an antibacterial agent, with mild comedolytic properties, and it often is added to topical antibiotic therapy to increase effectiveness and reduce the development of resistance. BP is available in strengths from 2.5% to 10% and in a variety of formulations, which can be used as leave-on or wash-off agents. Common side effects include dose dependent skin irritation and bleaching of fabric.

Topical antibiotics, including clindamycin and erythromycin, work through both their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory affects. Monotherapy with topical antibiotics is no longer recommended; instead they should be used in combination with BP to prevent bacterial resistance. The preferred topical antibiotic is clindamycin 1% solution or gel. Clindamycin is available in a combination with BP, which may enhance compliance with the treatment regimen.

Topical retinoids are vitamin A derivatives that are the core of treatment. They are effective for all forms of acne and should always be used in the treatment of comedonal acne. There are currently three active agents available: tretinoin (0.025%-0.1% in cream, gel, or microsphere gel vehicles), adapalene (0.1% and 0.3% cream or 0.1% lotion), and tazarotene (0.05% and 0.1% cream, gel, or foam). Combination products are available containing clindamycin and BP. The main side effects of retinoids include dryness, peeling, erythema, and skin irritation. Reducing the frequency of application or potency used may be helpful for limiting these side effects. Topical retinoids increase the risk of photosensitivity, so patients should be counseled on daily sunscreen use, and their use is contraindicated in pregnancy.

Dapsone is an alternative topical treatment for mild acne. Topical dapsone is primarily effective in reducing inflammatory lesions, and seems to be more beneficial for female patients. Dapsone can be combined with topical retinoids if comedonal lesions are present.

Moderate acne can be treated with either topical combination therapy as described above, or systemic antibiotics plus a TR and BP, with or without the addition of a topical antibiotic as well. Female patients may also consider combined oral contraceptives or spironolactone for the treatment of moderate acne.

Systemic antibiotics have been used in the treatment of acne vulgaris for many years, and they are indicated for use in moderate to severe acne. They should always be used in combination with topical therapies, specifically a retinoid or BP. Generally, systemic antibiotics should be used for the shortest possible duration, often 3 months, to prevent the development of bacterial resistance. Tetracyclines and macrolides have the strongest evidence for efficacy. Doxycycline and minocycline are considered equally effective and are the preferred first-line oral antibiotics. Azithromycin has been studied in a variety of pulse dose regimens, and is a good alternative for patients who are not candidates for tetracyclines.

Combined oral contraceptive pills (COCs) are another option for the treatment of acne in female patients. COCs improve acne through their antiandrogenic effects. Spironolactone also has antiandrogen properties, and while it is not FDA approved for the treatment of acne, the AAD guidelines support selective use in women. Spironolactone has been studied at doses from 50 to 200 mg daily and has shown clinically significant improvement in acne. Side effects include diuresis, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, and rare hyperkalemia.

Severe acne is treated with an oral antibiotic plus topical combination therapy, or oral isotretinoin, with the addition where appropriate of COCs or oral spironolactone.

Oral isotretinoin, an isomer of retinoic acid, is approved by the FDA for the treatment of severe recalcitrant acne. It causes decreased sebum production, acne lesions, and scarring. It can also be considered in the treatment of moderate acne that is resistant to other treatments, relapses quickly, or produces significant scarring or psychosocial distress. Serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and transaminases can rise during treatment, and should be monitored. Because of the risk of teratogenic effects, the FDA has mandated that all patients receiving isotretinoin must participate in the iPLEDGE risk management program, which requires abstinence or two forms of birth control. While isotretinoin requires monitoring and carries the possibility of significant side effects, it is an effective treatment option for patients with severe recalcitrant acne.

The bottom line

Acne is commonly treated by primary care physicians. A clear approach of graded treatment based on severity of disease yields improvement in outcomes. Mild acne should be treated with benzoyl peroxide, retinoids or a combinations of topical treatments. Systemic antibiotics should be combined with topical therapies for moderate to severe acne. Female patients may also consider using combined oral contraceptives and spironolactone. Oral isotretinoin is an effective option for severe acne, but requires close monitoring.

References

Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74[5]:945-73.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. Epub 2016 Feb 17).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Marriott is an attending family physician at Capital Health Primary Care in Hamilton, N.J.

Acne affects 85% of teenagers but can frequently persist into adulthood. It causes significant physical and psychological effects for patients including facial scarring, depression, and decreased self-esteem. The initial approach to acne is determined according to presenting severity, emphasizing topical treatment for milder disease and the addition of oral therapy as disease becomes more severe.

Treatment of mild acne can begin with either benzoyl peroxide (BP) or a topical retinoid (TR). Another option for slightly more severe acne is to start with the initially suggested treatment for moderately severe acne, which is topical combination therapy with BP plus a topical antibiotic; TR plus BP; or TR plus BP in combination with a topical antibiotic. Combination therapy can be given either with separate application of the different medicines or by using fixed combination products that include the separate components in one formulation.

BP is an antibacterial agent, with mild comedolytic properties, and it often is added to topical antibiotic therapy to increase effectiveness and reduce the development of resistance. BP is available in strengths from 2.5% to 10% and in a variety of formulations, which can be used as leave-on or wash-off agents. Common side effects include dose dependent skin irritation and bleaching of fabric.

Topical antibiotics, including clindamycin and erythromycin, work through both their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory affects. Monotherapy with topical antibiotics is no longer recommended; instead they should be used in combination with BP to prevent bacterial resistance. The preferred topical antibiotic is clindamycin 1% solution or gel. Clindamycin is available in a combination with BP, which may enhance compliance with the treatment regimen.

Topical retinoids are vitamin A derivatives that are the core of treatment. They are effective for all forms of acne and should always be used in the treatment of comedonal acne. There are currently three active agents available: tretinoin (0.025%-0.1% in cream, gel, or microsphere gel vehicles), adapalene (0.1% and 0.3% cream or 0.1% lotion), and tazarotene (0.05% and 0.1% cream, gel, or foam). Combination products are available containing clindamycin and BP. The main side effects of retinoids include dryness, peeling, erythema, and skin irritation. Reducing the frequency of application or potency used may be helpful for limiting these side effects. Topical retinoids increase the risk of photosensitivity, so patients should be counseled on daily sunscreen use, and their use is contraindicated in pregnancy.

Dapsone is an alternative topical treatment for mild acne. Topical dapsone is primarily effective in reducing inflammatory lesions, and seems to be more beneficial for female patients. Dapsone can be combined with topical retinoids if comedonal lesions are present.

Moderate acne can be treated with either topical combination therapy as described above, or systemic antibiotics plus a TR and BP, with or without the addition of a topical antibiotic as well. Female patients may also consider combined oral contraceptives or spironolactone for the treatment of moderate acne.

Systemic antibiotics have been used in the treatment of acne vulgaris for many years, and they are indicated for use in moderate to severe acne. They should always be used in combination with topical therapies, specifically a retinoid or BP. Generally, systemic antibiotics should be used for the shortest possible duration, often 3 months, to prevent the development of bacterial resistance. Tetracyclines and macrolides have the strongest evidence for efficacy. Doxycycline and minocycline are considered equally effective and are the preferred first-line oral antibiotics. Azithromycin has been studied in a variety of pulse dose regimens, and is a good alternative for patients who are not candidates for tetracyclines.

Combined oral contraceptive pills (COCs) are another option for the treatment of acne in female patients. COCs improve acne through their antiandrogenic effects. Spironolactone also has antiandrogen properties, and while it is not FDA approved for the treatment of acne, the AAD guidelines support selective use in women. Spironolactone has been studied at doses from 50 to 200 mg daily and has shown clinically significant improvement in acne. Side effects include diuresis, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, and rare hyperkalemia.

Severe acne is treated with an oral antibiotic plus topical combination therapy, or oral isotretinoin, with the addition where appropriate of COCs or oral spironolactone.

Oral isotretinoin, an isomer of retinoic acid, is approved by the FDA for the treatment of severe recalcitrant acne. It causes decreased sebum production, acne lesions, and scarring. It can also be considered in the treatment of moderate acne that is resistant to other treatments, relapses quickly, or produces significant scarring or psychosocial distress. Serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and transaminases can rise during treatment, and should be monitored. Because of the risk of teratogenic effects, the FDA has mandated that all patients receiving isotretinoin must participate in the iPLEDGE risk management program, which requires abstinence or two forms of birth control. While isotretinoin requires monitoring and carries the possibility of significant side effects, it is an effective treatment option for patients with severe recalcitrant acne.

The bottom line

Acne is commonly treated by primary care physicians. A clear approach of graded treatment based on severity of disease yields improvement in outcomes. Mild acne should be treated with benzoyl peroxide, retinoids or a combinations of topical treatments. Systemic antibiotics should be combined with topical therapies for moderate to severe acne. Female patients may also consider using combined oral contraceptives and spironolactone. Oral isotretinoin is an effective option for severe acne, but requires close monitoring.

References

Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74[5]:945-73.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. Epub 2016 Feb 17).

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Marriott is an attending family physician at Capital Health Primary Care in Hamilton, N.J.

Acne affects 85% of teenagers but can frequently persist into adulthood. It causes significant physical and psychological effects for patients including facial scarring, depression, and decreased self-esteem. The initial approach to acne is determined according to presenting severity, emphasizing topical treatment for milder disease and the addition of oral therapy as disease becomes more severe.

Treatment of mild acne can begin with either benzoyl peroxide (BP) or a topical retinoid (TR). Another option for slightly more severe acne is to start with the initially suggested treatment for moderately severe acne, which is topical combination therapy with BP plus a topical antibiotic; TR plus BP; or TR plus BP in combination with a topical antibiotic. Combination therapy can be given either with separate application of the different medicines or by using fixed combination products that include the separate components in one formulation.

BP is an antibacterial agent, with mild comedolytic properties, and it often is added to topical antibiotic therapy to increase effectiveness and reduce the development of resistance. BP is available in strengths from 2.5% to 10% and in a variety of formulations, which can be used as leave-on or wash-off agents. Common side effects include dose dependent skin irritation and bleaching of fabric.