User login

PILOT Program Offers Pulmonary Fibrosis Grand Rounds and Other Medical Education Resources

The Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation and the France Foundation are partnering to provide Grand Rounds, podcasts and other continuing medical education resources and activities for clinicians and patients/caregivers. This global initiative, known as “PILOT”, is designed to provide comprehensive continuing medical education supporting the diagnosis and management of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation and the France Foundation are partnering to provide Grand Rounds, podcasts and other continuing medical education resources and activities for clinicians and patients/caregivers. This global initiative, known as “PILOT”, is designed to provide comprehensive continuing medical education supporting the diagnosis and management of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation and the France Foundation are partnering to provide Grand Rounds, podcasts and other continuing medical education resources and activities for clinicians and patients/caregivers. This global initiative, known as “PILOT”, is designed to provide comprehensive continuing medical education supporting the diagnosis and management of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

3rd World Congress on Cutaneous Lymphomas to Take Place October 26-28

Columbia University will be the setting for the 3rd World Congress on Cutaneous Lymphomas, Oct. 26-28, sponsored by the International Society of Cutaneous Lymphoma in collaboration with the US Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force. The event is being organized by the Department of Dermatology at Columbia University.

This year, the Congress will be accompanied by a two-day patient conference where news from the World Congress will be summarized and presented to patients. The patient conference will take place Oct. 29-30 and is being organized by the Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation.

Columbia University will be the setting for the 3rd World Congress on Cutaneous Lymphomas, Oct. 26-28, sponsored by the International Society of Cutaneous Lymphoma in collaboration with the US Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force. The event is being organized by the Department of Dermatology at Columbia University.

This year, the Congress will be accompanied by a two-day patient conference where news from the World Congress will be summarized and presented to patients. The patient conference will take place Oct. 29-30 and is being organized by the Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation.

Columbia University will be the setting for the 3rd World Congress on Cutaneous Lymphomas, Oct. 26-28, sponsored by the International Society of Cutaneous Lymphoma in collaboration with the US Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force. The event is being organized by the Department of Dermatology at Columbia University.

This year, the Congress will be accompanied by a two-day patient conference where news from the World Congress will be summarized and presented to patients. The patient conference will take place Oct. 29-30 and is being organized by the Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation.

New Clinical Recommendations Published for Alpha-1 Diagnosis and Treatment

New clinical practice guidelines on how to properly diagnose and treat Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (Alpha-1) in adults have been published in the Journal of the COPD Foundation. The guidelines have been endorsed by the Alpha-1 Foundation Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee.

Based on the latest evidence and six years of work, the guidelines recommend best practices on testing for Alpha-1, managing Alpha-1 lung and liver disease, and when augmentation therapy should be prescribed, among other recommendations. They are intended to update and simplify a 2003 document from the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society.

“We believe the Summary of Recommendations of these guidelines is the most efficient tool that busy physicians have ever had to follow best practices in detection, diagnosis, and treatment of Alpha-1 in adults,” said Robert Sandhaus, MD, PhD, who co-chaired the Guidelines committee. “The Alpha-1 community has long needed more accessible guidelines based on the latest scientific literature.

The new clinical guidelines were published in the July issue of Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases: The Journal of the COPD Foundation. They recommend that anyone with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease should be tested for Alpha-1, regardless of age or ethnicity; that anyone with unexplained chronic liver disease should be tested for Alpha-1; and that parents, siblings, and children as well as extended family members of Alphas, or others with an abnormal alpha-1 gene, should receive genetic counseling and be offered testing for Alpha-1.

New clinical practice guidelines on how to properly diagnose and treat Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (Alpha-1) in adults have been published in the Journal of the COPD Foundation. The guidelines have been endorsed by the Alpha-1 Foundation Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee.

Based on the latest evidence and six years of work, the guidelines recommend best practices on testing for Alpha-1, managing Alpha-1 lung and liver disease, and when augmentation therapy should be prescribed, among other recommendations. They are intended to update and simplify a 2003 document from the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society.

“We believe the Summary of Recommendations of these guidelines is the most efficient tool that busy physicians have ever had to follow best practices in detection, diagnosis, and treatment of Alpha-1 in adults,” said Robert Sandhaus, MD, PhD, who co-chaired the Guidelines committee. “The Alpha-1 community has long needed more accessible guidelines based on the latest scientific literature.

The new clinical guidelines were published in the July issue of Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases: The Journal of the COPD Foundation. They recommend that anyone with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease should be tested for Alpha-1, regardless of age or ethnicity; that anyone with unexplained chronic liver disease should be tested for Alpha-1; and that parents, siblings, and children as well as extended family members of Alphas, or others with an abnormal alpha-1 gene, should receive genetic counseling and be offered testing for Alpha-1.

New clinical practice guidelines on how to properly diagnose and treat Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (Alpha-1) in adults have been published in the Journal of the COPD Foundation. The guidelines have been endorsed by the Alpha-1 Foundation Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee.

Based on the latest evidence and six years of work, the guidelines recommend best practices on testing for Alpha-1, managing Alpha-1 lung and liver disease, and when augmentation therapy should be prescribed, among other recommendations. They are intended to update and simplify a 2003 document from the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society.

“We believe the Summary of Recommendations of these guidelines is the most efficient tool that busy physicians have ever had to follow best practices in detection, diagnosis, and treatment of Alpha-1 in adults,” said Robert Sandhaus, MD, PhD, who co-chaired the Guidelines committee. “The Alpha-1 community has long needed more accessible guidelines based on the latest scientific literature.

The new clinical guidelines were published in the July issue of Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases: The Journal of the COPD Foundation. They recommend that anyone with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease should be tested for Alpha-1, regardless of age or ethnicity; that anyone with unexplained chronic liver disease should be tested for Alpha-1; and that parents, siblings, and children as well as extended family members of Alphas, or others with an abnormal alpha-1 gene, should receive genetic counseling and be offered testing for Alpha-1.

NORD Issues Statement as US Senate Postpones Vote on Cures Legislation

NORD President and CEO Peter L. Saltonstall expressed disappointment “on behalf of the one in 10 Americans with rare diseases, most of whom are still waiting for a cure” at the US Senate’s decision to postpone a vote on the Senate Innovations for Healthier Americans Initiative until at least September.

“This vital package includes billions of dollars to spur medical innovation that would help the rare disease community,” Mr. Saltonstall said in a statement released by NORD, including needed funding for medical research at NIH and to accelerate product review at FDA, as well as for special initiatives such as the Cancer Moonshot headed by Vice President Joe Biden.

“Most pressing,” Mr. Saltonstall added, “is the reauthorization of the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher program, currently set to expire at the end of September.” NORD has been a strong and consistent advocate for that program, which encourages the development of therapies for rare pediatric diseases.

NORD President and CEO Peter L. Saltonstall expressed disappointment “on behalf of the one in 10 Americans with rare diseases, most of whom are still waiting for a cure” at the US Senate’s decision to postpone a vote on the Senate Innovations for Healthier Americans Initiative until at least September.

“This vital package includes billions of dollars to spur medical innovation that would help the rare disease community,” Mr. Saltonstall said in a statement released by NORD, including needed funding for medical research at NIH and to accelerate product review at FDA, as well as for special initiatives such as the Cancer Moonshot headed by Vice President Joe Biden.

“Most pressing,” Mr. Saltonstall added, “is the reauthorization of the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher program, currently set to expire at the end of September.” NORD has been a strong and consistent advocate for that program, which encourages the development of therapies for rare pediatric diseases.

NORD President and CEO Peter L. Saltonstall expressed disappointment “on behalf of the one in 10 Americans with rare diseases, most of whom are still waiting for a cure” at the US Senate’s decision to postpone a vote on the Senate Innovations for Healthier Americans Initiative until at least September.

“This vital package includes billions of dollars to spur medical innovation that would help the rare disease community,” Mr. Saltonstall said in a statement released by NORD, including needed funding for medical research at NIH and to accelerate product review at FDA, as well as for special initiatives such as the Cancer Moonshot headed by Vice President Joe Biden.

“Most pressing,” Mr. Saltonstall added, “is the reauthorization of the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher program, currently set to expire at the end of September.” NORD has been a strong and consistent advocate for that program, which encourages the development of therapies for rare pediatric diseases.

NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Summit to Feature Speakers from FDA, NIH, and ACMG

FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, will deliver the keynote address on the opening morning of the annual NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Summit, which is scheduled for October 17–18 in Arlington, Virginia. Dr. Califf will be among more than 20 FDA speakers and several from NIH at the event, which draws together patient advocates as well as government, industry, and academic professionals working with rare diseases.

David Flannery, MD, Medical Director of the American College of Medical Genetics, will talk about “Telemedicine and Rare Diseases,” and will present a live telemedicine demo. In a session on genetic innovation, moderator Nora Yang, PhD, MBA, from the NIH, and panelists from GeneDx, Intellia Therapeutics, Spark Therapeutics, and the FDA will discuss gene-editing, gene-sequencing and gene therapy.

Other topics to be addressed include the crucial role of data in advancing diagnosis and clinical drug development, focus on pediatric diseases, and the challenge of access and reimbursement.

The Summit will include a poster session. Poster abstracts may be submitted by students as well as professionals. August 19th is the deadline for abstracts. Read more about poster submissions.

FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, will deliver the keynote address on the opening morning of the annual NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Summit, which is scheduled for October 17–18 in Arlington, Virginia. Dr. Califf will be among more than 20 FDA speakers and several from NIH at the event, which draws together patient advocates as well as government, industry, and academic professionals working with rare diseases.

David Flannery, MD, Medical Director of the American College of Medical Genetics, will talk about “Telemedicine and Rare Diseases,” and will present a live telemedicine demo. In a session on genetic innovation, moderator Nora Yang, PhD, MBA, from the NIH, and panelists from GeneDx, Intellia Therapeutics, Spark Therapeutics, and the FDA will discuss gene-editing, gene-sequencing and gene therapy.

Other topics to be addressed include the crucial role of data in advancing diagnosis and clinical drug development, focus on pediatric diseases, and the challenge of access and reimbursement.

The Summit will include a poster session. Poster abstracts may be submitted by students as well as professionals. August 19th is the deadline for abstracts. Read more about poster submissions.

FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, will deliver the keynote address on the opening morning of the annual NORD Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Summit, which is scheduled for October 17–18 in Arlington, Virginia. Dr. Califf will be among more than 20 FDA speakers and several from NIH at the event, which draws together patient advocates as well as government, industry, and academic professionals working with rare diseases.

David Flannery, MD, Medical Director of the American College of Medical Genetics, will talk about “Telemedicine and Rare Diseases,” and will present a live telemedicine demo. In a session on genetic innovation, moderator Nora Yang, PhD, MBA, from the NIH, and panelists from GeneDx, Intellia Therapeutics, Spark Therapeutics, and the FDA will discuss gene-editing, gene-sequencing and gene therapy.

Other topics to be addressed include the crucial role of data in advancing diagnosis and clinical drug development, focus on pediatric diseases, and the challenge of access and reimbursement.

The Summit will include a poster session. Poster abstracts may be submitted by students as well as professionals. August 19th is the deadline for abstracts. Read more about poster submissions.

ACC encourages adoption of international standards for stronger data exchange

Use of Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) standards and profiles generates the necessary technical framework to exchange health care data, while maintaining the syntactic and semantic components needed to accommodate a diverse range of health information consumers, according to a new policy statement by the American College of Cardiology.

Systems developed in accordance with IHE better communicate, are easier to implement, and enable health care providers to use information more effectively, wrote lead author John R. Windle, MD, of the University of Nebraska, Omaha. The policy statement was joined by the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, among other medical societies (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 15 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.017).

“The ACC believes that meaningful interoperability of data, agnostic of proprietary vendor formatting, is crucial for optimal patient care as well as the many associated activities necessary to support a robust and transparent health care delivery system,” the ACC policy states. “IHE serves a unique role and fills a critical gap in pursuit of this goal.”

IHE is a nonprofit international organization established in 1998 that develops standards-based frameworks for sharing information within care sites and across networks. The organization leverages existing data standards to facilitate communication of information among health care information systems and joins users of health care information technology (HIT) in a recurring four-step process, according to the IHE website. The process includes defining critical-use cases for information sharing, creating detailed specifications for communication among systems to address the critical-use cases, implementing these specifications throughout the industry, and selecting and optimizing established standards. Industry experts then implement these specifications, called “IHE profiles,” into “HIT systems,” and IHE tests the systems at planned and supervised events called “connectathons.”

IHE is divided into 12 clinical domains, each of which includes integration profiles. The profiles identify actors, transactions, and information content necessary to address use cases within certain practice areas. The work is compiled into IHE technical frameworks – detailed documents that serve as implementation guides. All documents and artifacts are freely available on the IHE website. Within the cardiology domain, 14 profiles have completed the development cycle and have been tested and validated at a connectathon testing event.

Through its policy statement, the ACC is promoting adoption of IHE by several means, including:

• Engaging support from health care system executives by encouraging specification of support for IHE integration profiles in all requests for proposals.

• Encouraging end users to request support for IHE integration profiles.

• Lobbying the Department of Health and Human Services Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to support the IHE technical frameworks in the EHR Incentive Program and beyond.

• Collaborating with other organizations such as the American Heart Association and the Joint Commission.

The ACC policy notes that health providers should not underestimate the complexity of true interoperability, but stresses that IHE is key to a stronger platform for data exchange.

“Developing meaningful interoperability across the diverse and complex field of health care will require leadership from medical societies as well as federal and state organizations in the form of policies and financial incentives that will steer industry to develop and implement the infrastructure and systems that consumers require,” Dr. Windle and his colleagues wrote. “Although we cannot overemphasize the enormity of this process, IHE will allow the rapid dissemination of best practices through efforts in standardization.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Use of Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) standards and profiles generates the necessary technical framework to exchange health care data, while maintaining the syntactic and semantic components needed to accommodate a diverse range of health information consumers, according to a new policy statement by the American College of Cardiology.

Systems developed in accordance with IHE better communicate, are easier to implement, and enable health care providers to use information more effectively, wrote lead author John R. Windle, MD, of the University of Nebraska, Omaha. The policy statement was joined by the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, among other medical societies (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 15 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.017).

“The ACC believes that meaningful interoperability of data, agnostic of proprietary vendor formatting, is crucial for optimal patient care as well as the many associated activities necessary to support a robust and transparent health care delivery system,” the ACC policy states. “IHE serves a unique role and fills a critical gap in pursuit of this goal.”

IHE is a nonprofit international organization established in 1998 that develops standards-based frameworks for sharing information within care sites and across networks. The organization leverages existing data standards to facilitate communication of information among health care information systems and joins users of health care information technology (HIT) in a recurring four-step process, according to the IHE website. The process includes defining critical-use cases for information sharing, creating detailed specifications for communication among systems to address the critical-use cases, implementing these specifications throughout the industry, and selecting and optimizing established standards. Industry experts then implement these specifications, called “IHE profiles,” into “HIT systems,” and IHE tests the systems at planned and supervised events called “connectathons.”

IHE is divided into 12 clinical domains, each of which includes integration profiles. The profiles identify actors, transactions, and information content necessary to address use cases within certain practice areas. The work is compiled into IHE technical frameworks – detailed documents that serve as implementation guides. All documents and artifacts are freely available on the IHE website. Within the cardiology domain, 14 profiles have completed the development cycle and have been tested and validated at a connectathon testing event.

Through its policy statement, the ACC is promoting adoption of IHE by several means, including:

• Engaging support from health care system executives by encouraging specification of support for IHE integration profiles in all requests for proposals.

• Encouraging end users to request support for IHE integration profiles.

• Lobbying the Department of Health and Human Services Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to support the IHE technical frameworks in the EHR Incentive Program and beyond.

• Collaborating with other organizations such as the American Heart Association and the Joint Commission.

The ACC policy notes that health providers should not underestimate the complexity of true interoperability, but stresses that IHE is key to a stronger platform for data exchange.

“Developing meaningful interoperability across the diverse and complex field of health care will require leadership from medical societies as well as federal and state organizations in the form of policies and financial incentives that will steer industry to develop and implement the infrastructure and systems that consumers require,” Dr. Windle and his colleagues wrote. “Although we cannot overemphasize the enormity of this process, IHE will allow the rapid dissemination of best practices through efforts in standardization.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Use of Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) standards and profiles generates the necessary technical framework to exchange health care data, while maintaining the syntactic and semantic components needed to accommodate a diverse range of health information consumers, according to a new policy statement by the American College of Cardiology.

Systems developed in accordance with IHE better communicate, are easier to implement, and enable health care providers to use information more effectively, wrote lead author John R. Windle, MD, of the University of Nebraska, Omaha. The policy statement was joined by the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, among other medical societies (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 15 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.017).

“The ACC believes that meaningful interoperability of data, agnostic of proprietary vendor formatting, is crucial for optimal patient care as well as the many associated activities necessary to support a robust and transparent health care delivery system,” the ACC policy states. “IHE serves a unique role and fills a critical gap in pursuit of this goal.”

IHE is a nonprofit international organization established in 1998 that develops standards-based frameworks for sharing information within care sites and across networks. The organization leverages existing data standards to facilitate communication of information among health care information systems and joins users of health care information technology (HIT) in a recurring four-step process, according to the IHE website. The process includes defining critical-use cases for information sharing, creating detailed specifications for communication among systems to address the critical-use cases, implementing these specifications throughout the industry, and selecting and optimizing established standards. Industry experts then implement these specifications, called “IHE profiles,” into “HIT systems,” and IHE tests the systems at planned and supervised events called “connectathons.”

IHE is divided into 12 clinical domains, each of which includes integration profiles. The profiles identify actors, transactions, and information content necessary to address use cases within certain practice areas. The work is compiled into IHE technical frameworks – detailed documents that serve as implementation guides. All documents and artifacts are freely available on the IHE website. Within the cardiology domain, 14 profiles have completed the development cycle and have been tested and validated at a connectathon testing event.

Through its policy statement, the ACC is promoting adoption of IHE by several means, including:

• Engaging support from health care system executives by encouraging specification of support for IHE integration profiles in all requests for proposals.

• Encouraging end users to request support for IHE integration profiles.

• Lobbying the Department of Health and Human Services Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to support the IHE technical frameworks in the EHR Incentive Program and beyond.

• Collaborating with other organizations such as the American Heart Association and the Joint Commission.

The ACC policy notes that health providers should not underestimate the complexity of true interoperability, but stresses that IHE is key to a stronger platform for data exchange.

“Developing meaningful interoperability across the diverse and complex field of health care will require leadership from medical societies as well as federal and state organizations in the form of policies and financial incentives that will steer industry to develop and implement the infrastructure and systems that consumers require,” Dr. Windle and his colleagues wrote. “Although we cannot overemphasize the enormity of this process, IHE will allow the rapid dissemination of best practices through efforts in standardization.”

On Twitter @legal_med

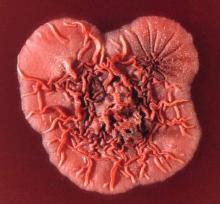

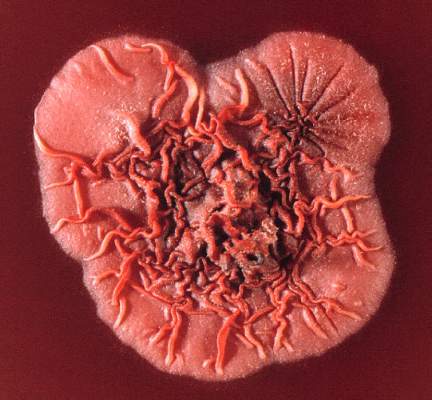

PCR assay quicker but less sensitive at penicilliosis diagnosis

A real-time PCR assay was effective at rapidly diagnosing penicilliosis caused by Talaromyces marneffei, according to Thuy Le, MD, and her associates.

Sensitivity of the assay was better when samples were collected from plasma prior to antifungal therapy. In a group of 27 HIV-infected patients from whom samples were collected prior to antifungal therapy, the assay detected the T. marneffei MP1 gene in 19 samples, while in a group of 23 HIV-infected patients from whom samples were collected within 48 hours of antifungal therapy, the assay successfully detected the MP1 gene in 12 samples.

In an additional sample of 20 HIV-infected patients without penicilliosis, the assay found no signals of the T. marneffei MP1 gene in any of the tested plasma samples, giving a specificity of 100%. All testing was completed within 5-6 hours, significantly less than the 5 days needed for Bactec system testing.

“This real-time PCR assay should not replace the need for conventional microbiology methods in diagnosing penicilliosis. However, in conjunction with culturing, it can be used as a rapid rule-in test that can make a significant difference in patient management by allowing antifungal therapy to begin sooner, particularly in patients without skin lesions, and has the potential to improve the outcomes of T. marneffei–infected patients,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Mycoses (doi: 10.1111/myc.12530).

A real-time PCR assay was effective at rapidly diagnosing penicilliosis caused by Talaromyces marneffei, according to Thuy Le, MD, and her associates.

Sensitivity of the assay was better when samples were collected from plasma prior to antifungal therapy. In a group of 27 HIV-infected patients from whom samples were collected prior to antifungal therapy, the assay detected the T. marneffei MP1 gene in 19 samples, while in a group of 23 HIV-infected patients from whom samples were collected within 48 hours of antifungal therapy, the assay successfully detected the MP1 gene in 12 samples.

In an additional sample of 20 HIV-infected patients without penicilliosis, the assay found no signals of the T. marneffei MP1 gene in any of the tested plasma samples, giving a specificity of 100%. All testing was completed within 5-6 hours, significantly less than the 5 days needed for Bactec system testing.

“This real-time PCR assay should not replace the need for conventional microbiology methods in diagnosing penicilliosis. However, in conjunction with culturing, it can be used as a rapid rule-in test that can make a significant difference in patient management by allowing antifungal therapy to begin sooner, particularly in patients without skin lesions, and has the potential to improve the outcomes of T. marneffei–infected patients,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Mycoses (doi: 10.1111/myc.12530).

A real-time PCR assay was effective at rapidly diagnosing penicilliosis caused by Talaromyces marneffei, according to Thuy Le, MD, and her associates.

Sensitivity of the assay was better when samples were collected from plasma prior to antifungal therapy. In a group of 27 HIV-infected patients from whom samples were collected prior to antifungal therapy, the assay detected the T. marneffei MP1 gene in 19 samples, while in a group of 23 HIV-infected patients from whom samples were collected within 48 hours of antifungal therapy, the assay successfully detected the MP1 gene in 12 samples.

In an additional sample of 20 HIV-infected patients without penicilliosis, the assay found no signals of the T. marneffei MP1 gene in any of the tested plasma samples, giving a specificity of 100%. All testing was completed within 5-6 hours, significantly less than the 5 days needed for Bactec system testing.

“This real-time PCR assay should not replace the need for conventional microbiology methods in diagnosing penicilliosis. However, in conjunction with culturing, it can be used as a rapid rule-in test that can make a significant difference in patient management by allowing antifungal therapy to begin sooner, particularly in patients without skin lesions, and has the potential to improve the outcomes of T. marneffei–infected patients,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Mycoses (doi: 10.1111/myc.12530).

FROM MYCOSES

The role of lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer, Part 1

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers present at an early stage with excellent overall survival – approximately 85% – in clinical stage I disease. Since 1988, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of endometrial cancer has required surgical staging reflecting increasing data on the prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and the treatment implications for node positive cancers.

Indeed, lymph nodes represent the most common location for extrauterine spread in endometrial cancer. The lymphatic drainage from the uterus is to both the pelvic and the para-aortic lymph nodes. Lymphatic channels from the uterus can drain directly from the fundus via the infundibulopelvic ligament to the aortic lymph node chain, thereby bypassing the pelvic lymph nodes. As a result, there is a 2%-3% risk of isolated aortic metastasis with negative pelvic lymph nodes.

The extent of lymph node evaluation required for staging is debatable. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend complete hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and additional procedures based on preoperative and intraoperative findings. During surgery, the surgeon should evaluate all peritoneal surfaces and the retroperitoneal lymphatic chains for abnormalities. All suspicious lymph nodes should be removed, but the extent of lymphadenectomy should be based on the NCCN guidelines.1 The NCCN offers the option for use of sentinel lymph node evaluation with adherence to specific staging algorithms for this technology.

Proponents of lymphadenectomy cite the need for accurate staging to guide adjuvant therapies, to provide prognostic information, and to eradicate metastatic lymph nodes with possible therapeutic benefit. However, criticisms of lymphadenectomy include a lack of randomized studies demonstrating a therapeutic benefit and the morbidity of lymphedema with its corresponding quality of life and cost implications. As a result, practices regarding lymph node evaluation vary widely.

There is conflicting data on whether there is a therapeutic benefit to performing lymphadenectomy. Retrospective studies have shown a benefit, but this was not seen in two prospective trials. There appears to be clear benefit for debulking of clinically enlarged nodal metastasis,2,3 and likely benefit to resection of microscopic metastasis, particularly with combined pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.4,5,6,7,8

The ASTEC trial by Kitchener et al and an Italian collaborative trial by Benedetti et al, however, both evaluated the role of lymph node dissection in predominantly low-risk endometrial cancer and found no benefit.9,10 Both studies documented no difference in overall survival, but increased morbidity with lymphadenectomy. No prospective trials have evaluated the role of lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.

Universal use of complete lymphadenectomy in all patients with endometrial cancer would subject a large percent of low risk patients to undo surgical risk. The two most commonly utilized strategies are risk factor based lymphadenectomy and sentinel lymph node evaluation.

Tumors are considered low risk if they are less than 2cm in size, grade 1 or 2, and superficially invasive (less than 50% myometrial invasion).11 The risk of lymph node metastasis in these patients was exceedingly low with no lymph node metastasis detect in more than 400 women who prospectively underwent this evaluation, thus lymphadenectomy can be safely avoided. Utilizing risk factor based lymphadenectomy does require the availability of reliable frozen section pathology evaluation, which may be a limitation for some institutions.

A key argument against routine use of systematic lymphadenectomy is the concern for postoperative complications and lymphedema. The estimated incidence of lymphedema following lymphadenectomy is 20%-30%.12 However, there are challenges in studying lymphedema that likely limit our understanding of the true incidence. The ASTEC trial and Italian cooperative trial have demonstrated that there is an eight-fold increased risk of lymphedema in women who undergo lymphadenectomy, compared with those who do not.13 The development of lymphedema requires ongoing treatment with associated costs of care. Thus, the selective lymphadenectomy or sentinel nodes have the ability to reduce healthcare costs.14 Sentinel lymph nodes will be covered in Part Two of this article.

References

1. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014 Feb;12(2):248-80.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Dec;99(3):689-95.

3. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003 Sep-Oct;13(5):664-72.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 1995 Jan;56(1):29-33.

5. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jun 1;23(16):3668-75.

6. Lancet. 2010 Apr 3;375(9721):1165-72.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 1998 Dec;71(3):340-3.

8. Cancer. 2006 Oct 15;107(8):1823-30.

9. Lancet. 2009 Jan 10;373(9658):125-36.

10. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Dec 3;100(23):1707-16.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Apr;109(1):11-8.

12. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Aug;124(2 Pt 1):307-15.

13. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 21;(9):CD007585.

14. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Dec;135(3):518-24.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers present at an early stage with excellent overall survival – approximately 85% – in clinical stage I disease. Since 1988, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of endometrial cancer has required surgical staging reflecting increasing data on the prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and the treatment implications for node positive cancers.

Indeed, lymph nodes represent the most common location for extrauterine spread in endometrial cancer. The lymphatic drainage from the uterus is to both the pelvic and the para-aortic lymph nodes. Lymphatic channels from the uterus can drain directly from the fundus via the infundibulopelvic ligament to the aortic lymph node chain, thereby bypassing the pelvic lymph nodes. As a result, there is a 2%-3% risk of isolated aortic metastasis with negative pelvic lymph nodes.

The extent of lymph node evaluation required for staging is debatable. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend complete hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and additional procedures based on preoperative and intraoperative findings. During surgery, the surgeon should evaluate all peritoneal surfaces and the retroperitoneal lymphatic chains for abnormalities. All suspicious lymph nodes should be removed, but the extent of lymphadenectomy should be based on the NCCN guidelines.1 The NCCN offers the option for use of sentinel lymph node evaluation with adherence to specific staging algorithms for this technology.

Proponents of lymphadenectomy cite the need for accurate staging to guide adjuvant therapies, to provide prognostic information, and to eradicate metastatic lymph nodes with possible therapeutic benefit. However, criticisms of lymphadenectomy include a lack of randomized studies demonstrating a therapeutic benefit and the morbidity of lymphedema with its corresponding quality of life and cost implications. As a result, practices regarding lymph node evaluation vary widely.

There is conflicting data on whether there is a therapeutic benefit to performing lymphadenectomy. Retrospective studies have shown a benefit, but this was not seen in two prospective trials. There appears to be clear benefit for debulking of clinically enlarged nodal metastasis,2,3 and likely benefit to resection of microscopic metastasis, particularly with combined pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.4,5,6,7,8

The ASTEC trial by Kitchener et al and an Italian collaborative trial by Benedetti et al, however, both evaluated the role of lymph node dissection in predominantly low-risk endometrial cancer and found no benefit.9,10 Both studies documented no difference in overall survival, but increased morbidity with lymphadenectomy. No prospective trials have evaluated the role of lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.

Universal use of complete lymphadenectomy in all patients with endometrial cancer would subject a large percent of low risk patients to undo surgical risk. The two most commonly utilized strategies are risk factor based lymphadenectomy and sentinel lymph node evaluation.

Tumors are considered low risk if they are less than 2cm in size, grade 1 or 2, and superficially invasive (less than 50% myometrial invasion).11 The risk of lymph node metastasis in these patients was exceedingly low with no lymph node metastasis detect in more than 400 women who prospectively underwent this evaluation, thus lymphadenectomy can be safely avoided. Utilizing risk factor based lymphadenectomy does require the availability of reliable frozen section pathology evaluation, which may be a limitation for some institutions.

A key argument against routine use of systematic lymphadenectomy is the concern for postoperative complications and lymphedema. The estimated incidence of lymphedema following lymphadenectomy is 20%-30%.12 However, there are challenges in studying lymphedema that likely limit our understanding of the true incidence. The ASTEC trial and Italian cooperative trial have demonstrated that there is an eight-fold increased risk of lymphedema in women who undergo lymphadenectomy, compared with those who do not.13 The development of lymphedema requires ongoing treatment with associated costs of care. Thus, the selective lymphadenectomy or sentinel nodes have the ability to reduce healthcare costs.14 Sentinel lymph nodes will be covered in Part Two of this article.

References

1. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014 Feb;12(2):248-80.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Dec;99(3):689-95.

3. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003 Sep-Oct;13(5):664-72.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 1995 Jan;56(1):29-33.

5. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jun 1;23(16):3668-75.

6. Lancet. 2010 Apr 3;375(9721):1165-72.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 1998 Dec;71(3):340-3.

8. Cancer. 2006 Oct 15;107(8):1823-30.

9. Lancet. 2009 Jan 10;373(9658):125-36.

10. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Dec 3;100(23):1707-16.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Apr;109(1):11-8.

12. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Aug;124(2 Pt 1):307-15.

13. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 21;(9):CD007585.

14. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Dec;135(3):518-24.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers present at an early stage with excellent overall survival – approximately 85% – in clinical stage I disease. Since 1988, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of endometrial cancer has required surgical staging reflecting increasing data on the prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and the treatment implications for node positive cancers.

Indeed, lymph nodes represent the most common location for extrauterine spread in endometrial cancer. The lymphatic drainage from the uterus is to both the pelvic and the para-aortic lymph nodes. Lymphatic channels from the uterus can drain directly from the fundus via the infundibulopelvic ligament to the aortic lymph node chain, thereby bypassing the pelvic lymph nodes. As a result, there is a 2%-3% risk of isolated aortic metastasis with negative pelvic lymph nodes.

The extent of lymph node evaluation required for staging is debatable. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend complete hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and additional procedures based on preoperative and intraoperative findings. During surgery, the surgeon should evaluate all peritoneal surfaces and the retroperitoneal lymphatic chains for abnormalities. All suspicious lymph nodes should be removed, but the extent of lymphadenectomy should be based on the NCCN guidelines.1 The NCCN offers the option for use of sentinel lymph node evaluation with adherence to specific staging algorithms for this technology.

Proponents of lymphadenectomy cite the need for accurate staging to guide adjuvant therapies, to provide prognostic information, and to eradicate metastatic lymph nodes with possible therapeutic benefit. However, criticisms of lymphadenectomy include a lack of randomized studies demonstrating a therapeutic benefit and the morbidity of lymphedema with its corresponding quality of life and cost implications. As a result, practices regarding lymph node evaluation vary widely.

There is conflicting data on whether there is a therapeutic benefit to performing lymphadenectomy. Retrospective studies have shown a benefit, but this was not seen in two prospective trials. There appears to be clear benefit for debulking of clinically enlarged nodal metastasis,2,3 and likely benefit to resection of microscopic metastasis, particularly with combined pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.4,5,6,7,8

The ASTEC trial by Kitchener et al and an Italian collaborative trial by Benedetti et al, however, both evaluated the role of lymph node dissection in predominantly low-risk endometrial cancer and found no benefit.9,10 Both studies documented no difference in overall survival, but increased morbidity with lymphadenectomy. No prospective trials have evaluated the role of lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.

Universal use of complete lymphadenectomy in all patients with endometrial cancer would subject a large percent of low risk patients to undo surgical risk. The two most commonly utilized strategies are risk factor based lymphadenectomy and sentinel lymph node evaluation.

Tumors are considered low risk if they are less than 2cm in size, grade 1 or 2, and superficially invasive (less than 50% myometrial invasion).11 The risk of lymph node metastasis in these patients was exceedingly low with no lymph node metastasis detect in more than 400 women who prospectively underwent this evaluation, thus lymphadenectomy can be safely avoided. Utilizing risk factor based lymphadenectomy does require the availability of reliable frozen section pathology evaluation, which may be a limitation for some institutions.

A key argument against routine use of systematic lymphadenectomy is the concern for postoperative complications and lymphedema. The estimated incidence of lymphedema following lymphadenectomy is 20%-30%.12 However, there are challenges in studying lymphedema that likely limit our understanding of the true incidence. The ASTEC trial and Italian cooperative trial have demonstrated that there is an eight-fold increased risk of lymphedema in women who undergo lymphadenectomy, compared with those who do not.13 The development of lymphedema requires ongoing treatment with associated costs of care. Thus, the selective lymphadenectomy or sentinel nodes have the ability to reduce healthcare costs.14 Sentinel lymph nodes will be covered in Part Two of this article.

References

1. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014 Feb;12(2):248-80.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Dec;99(3):689-95.

3. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003 Sep-Oct;13(5):664-72.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 1995 Jan;56(1):29-33.

5. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jun 1;23(16):3668-75.

6. Lancet. 2010 Apr 3;375(9721):1165-72.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 1998 Dec;71(3):340-3.

8. Cancer. 2006 Oct 15;107(8):1823-30.

9. Lancet. 2009 Jan 10;373(9658):125-36.

10. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Dec 3;100(23):1707-16.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Apr;109(1):11-8.

12. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Aug;124(2 Pt 1):307-15.

13. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 21;(9):CD007585.

14. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Dec;135(3):518-24.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

FBI questions legality of telemedicine compact laws

The FBI is raising concerns that language in the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact violates federal regulations over criminal background checks. The government pushback could mean implementation delays of telemedicine legislation that 17 states have enacted.

In a letter to the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, an FBI attorney wrote that the state’s compact law does not meet federal rules that allow the sharing of information with states for purposes of criminal background checks. In addition, no federal statutory authority exists for the FBI to share criminal files with a “private” entity such as the interstate commission, wrote Christopher B. Chaney, an attorney in the FBI Office of the General Counsel in Clarksburg, W.Va. The FBI sent a letter expressing the same concerns to the Montana Department of Justice regarding Montana’s compact law.

The Minnesota Board of Medical Practice has requested that the FBI reverse its findings, writing in an Aug. 3 letter that the agency does not appear to fully understand how the compact works. The board is scheduled to begin issuing licenses via the compact in January 2017, said Ruth Martinez, the board’s executive director.

“We believe it’s an erroneous conclusion that they’ve drawn,” Ms. Martinez said in an interview. “We are very actively engaged in rule-writing and in preparing technology and so forth to be ready to issue licenses, and we feel very confident that this determination will be overturned.”

The Montana Board of Medical Examiners meanwhile is aware of the FBI’s letter and is closely monitoring the situation in Minnesota before taking action, said Ian Marquand, executive officer for the Montana Board of Medical Examiners.

“We are still digesting this and are anxious to see what happens with the Minnesota situation,” Mr. Marquand said in an interview. “That may provide the road map.”

The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact is aimed at making it easier for telemedicine physicians to gain licenses in multiple states. Under the model legislation, developed by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), physicians designate a member state as the state of principal licensure and select the other states in which they wish to be licensed. The state of principal licensure then verifies the physician’s eligibility and provides credential information to the interstate commission, which collects applicable fees and transmits the doctor’s information to the other states. Upon receipt in the additional states, the physician would be granted a license.

In July 2015, the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration awarded the FSMB a grant to support establishment of the commission and aid with the compact’s infrastructure.

There is nothing unique about Minnesota’s compact law, Ms. Martinez said. The statute is based on the same model legislation that passed in 16 other states. She believes that Minnesota’s law is merely one of the first to be reviewed by the FBI. Both Minnesota and Montana officials had requested that their respective state departments of justice determine if the compact laws met public law standards pertaining to criminal history records.

Ms. Martinez said that she hopes that the board’s letter to the FBI will help explain how the compact process works and prevent further federal rejections in other jurisdictions. She notes for example that the FBI incorrectly characterizes the interstate commission as a “private” entity in its letter, when the commission is a corporate body and a joint agency of the member states. The FBI also misunderstands how the commission interacts with the individual state licensing boards and the process of licensure, according to the board’s reply letter. It is not the commission that will be using FBI data, but the member states that will be utilizing the information in the course of verification, writes Rick Masters, special counsel to the National Center for Interstate Compacts.

The Federation of State Medical Boards is closely watching the matter and supports the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice, said Lisa A. Robin FSMB’s chief advocacy officer.

“The FSMB, along with the Council of State Governments (CSG), agrees with and supports the Minnesota board’s position in this matter,” Ms. Robin said in an emailed statement. “The compact’s statutory language does not alter state-based responsibility for the administration of criminal background checks, nor does it seek to extend this responsibility beyond individual state medical boards.”

At press time, the FBI’s Mr. Chaney had not responded to a message seeking comment.

On Twitter @legal_med

The FBI is raising concerns that language in the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact violates federal regulations over criminal background checks. The government pushback could mean implementation delays of telemedicine legislation that 17 states have enacted.

In a letter to the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, an FBI attorney wrote that the state’s compact law does not meet federal rules that allow the sharing of information with states for purposes of criminal background checks. In addition, no federal statutory authority exists for the FBI to share criminal files with a “private” entity such as the interstate commission, wrote Christopher B. Chaney, an attorney in the FBI Office of the General Counsel in Clarksburg, W.Va. The FBI sent a letter expressing the same concerns to the Montana Department of Justice regarding Montana’s compact law.

The Minnesota Board of Medical Practice has requested that the FBI reverse its findings, writing in an Aug. 3 letter that the agency does not appear to fully understand how the compact works. The board is scheduled to begin issuing licenses via the compact in January 2017, said Ruth Martinez, the board’s executive director.

“We believe it’s an erroneous conclusion that they’ve drawn,” Ms. Martinez said in an interview. “We are very actively engaged in rule-writing and in preparing technology and so forth to be ready to issue licenses, and we feel very confident that this determination will be overturned.”

The Montana Board of Medical Examiners meanwhile is aware of the FBI’s letter and is closely monitoring the situation in Minnesota before taking action, said Ian Marquand, executive officer for the Montana Board of Medical Examiners.

“We are still digesting this and are anxious to see what happens with the Minnesota situation,” Mr. Marquand said in an interview. “That may provide the road map.”

The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact is aimed at making it easier for telemedicine physicians to gain licenses in multiple states. Under the model legislation, developed by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), physicians designate a member state as the state of principal licensure and select the other states in which they wish to be licensed. The state of principal licensure then verifies the physician’s eligibility and provides credential information to the interstate commission, which collects applicable fees and transmits the doctor’s information to the other states. Upon receipt in the additional states, the physician would be granted a license.

In July 2015, the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration awarded the FSMB a grant to support establishment of the commission and aid with the compact’s infrastructure.

There is nothing unique about Minnesota’s compact law, Ms. Martinez said. The statute is based on the same model legislation that passed in 16 other states. She believes that Minnesota’s law is merely one of the first to be reviewed by the FBI. Both Minnesota and Montana officials had requested that their respective state departments of justice determine if the compact laws met public law standards pertaining to criminal history records.

Ms. Martinez said that she hopes that the board’s letter to the FBI will help explain how the compact process works and prevent further federal rejections in other jurisdictions. She notes for example that the FBI incorrectly characterizes the interstate commission as a “private” entity in its letter, when the commission is a corporate body and a joint agency of the member states. The FBI also misunderstands how the commission interacts with the individual state licensing boards and the process of licensure, according to the board’s reply letter. It is not the commission that will be using FBI data, but the member states that will be utilizing the information in the course of verification, writes Rick Masters, special counsel to the National Center for Interstate Compacts.

The Federation of State Medical Boards is closely watching the matter and supports the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice, said Lisa A. Robin FSMB’s chief advocacy officer.

“The FSMB, along with the Council of State Governments (CSG), agrees with and supports the Minnesota board’s position in this matter,” Ms. Robin said in an emailed statement. “The compact’s statutory language does not alter state-based responsibility for the administration of criminal background checks, nor does it seek to extend this responsibility beyond individual state medical boards.”

At press time, the FBI’s Mr. Chaney had not responded to a message seeking comment.

On Twitter @legal_med

The FBI is raising concerns that language in the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact violates federal regulations over criminal background checks. The government pushback could mean implementation delays of telemedicine legislation that 17 states have enacted.

In a letter to the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, an FBI attorney wrote that the state’s compact law does not meet federal rules that allow the sharing of information with states for purposes of criminal background checks. In addition, no federal statutory authority exists for the FBI to share criminal files with a “private” entity such as the interstate commission, wrote Christopher B. Chaney, an attorney in the FBI Office of the General Counsel in Clarksburg, W.Va. The FBI sent a letter expressing the same concerns to the Montana Department of Justice regarding Montana’s compact law.

The Minnesota Board of Medical Practice has requested that the FBI reverse its findings, writing in an Aug. 3 letter that the agency does not appear to fully understand how the compact works. The board is scheduled to begin issuing licenses via the compact in January 2017, said Ruth Martinez, the board’s executive director.

“We believe it’s an erroneous conclusion that they’ve drawn,” Ms. Martinez said in an interview. “We are very actively engaged in rule-writing and in preparing technology and so forth to be ready to issue licenses, and we feel very confident that this determination will be overturned.”

The Montana Board of Medical Examiners meanwhile is aware of the FBI’s letter and is closely monitoring the situation in Minnesota before taking action, said Ian Marquand, executive officer for the Montana Board of Medical Examiners.

“We are still digesting this and are anxious to see what happens with the Minnesota situation,” Mr. Marquand said in an interview. “That may provide the road map.”

The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact is aimed at making it easier for telemedicine physicians to gain licenses in multiple states. Under the model legislation, developed by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), physicians designate a member state as the state of principal licensure and select the other states in which they wish to be licensed. The state of principal licensure then verifies the physician’s eligibility and provides credential information to the interstate commission, which collects applicable fees and transmits the doctor’s information to the other states. Upon receipt in the additional states, the physician would be granted a license.

In July 2015, the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration awarded the FSMB a grant to support establishment of the commission and aid with the compact’s infrastructure.

There is nothing unique about Minnesota’s compact law, Ms. Martinez said. The statute is based on the same model legislation that passed in 16 other states. She believes that Minnesota’s law is merely one of the first to be reviewed by the FBI. Both Minnesota and Montana officials had requested that their respective state departments of justice determine if the compact laws met public law standards pertaining to criminal history records.

Ms. Martinez said that she hopes that the board’s letter to the FBI will help explain how the compact process works and prevent further federal rejections in other jurisdictions. She notes for example that the FBI incorrectly characterizes the interstate commission as a “private” entity in its letter, when the commission is a corporate body and a joint agency of the member states. The FBI also misunderstands how the commission interacts with the individual state licensing boards and the process of licensure, according to the board’s reply letter. It is not the commission that will be using FBI data, but the member states that will be utilizing the information in the course of verification, writes Rick Masters, special counsel to the National Center for Interstate Compacts.

The Federation of State Medical Boards is closely watching the matter and supports the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice, said Lisa A. Robin FSMB’s chief advocacy officer.

“The FSMB, along with the Council of State Governments (CSG), agrees with and supports the Minnesota board’s position in this matter,” Ms. Robin said in an emailed statement. “The compact’s statutory language does not alter state-based responsibility for the administration of criminal background checks, nor does it seek to extend this responsibility beyond individual state medical boards.”

At press time, the FBI’s Mr. Chaney had not responded to a message seeking comment.

On Twitter @legal_med

You oughta be in pictures - And maybe you are

The 2016 Vascular Annual Meeting photos are now available in our Flickr albums.

Since there were thousands and thousands of photos (we couldn’t even count them) chances are that if you attended VAM you are in at least one of them. If you won an award, your acceptance photo should be in the collection. All photos are large and high res, perfect for enlarging, printing and framing.

The photos are arranged by day, and within each day, by session.

Browse the photos here on Flickr, relive the memories, and be sure to type your name in the caption when you find your charming face.

The 2016 Vascular Annual Meeting photos are now available in our Flickr albums.

Since there were thousands and thousands of photos (we couldn’t even count them) chances are that if you attended VAM you are in at least one of them. If you won an award, your acceptance photo should be in the collection. All photos are large and high res, perfect for enlarging, printing and framing.

The photos are arranged by day, and within each day, by session.

Browse the photos here on Flickr, relive the memories, and be sure to type your name in the caption when you find your charming face.

The 2016 Vascular Annual Meeting photos are now available in our Flickr albums.

Since there were thousands and thousands of photos (we couldn’t even count them) chances are that if you attended VAM you are in at least one of them. If you won an award, your acceptance photo should be in the collection. All photos are large and high res, perfect for enlarging, printing and framing.

The photos are arranged by day, and within each day, by session.

Browse the photos here on Flickr, relive the memories, and be sure to type your name in the caption when you find your charming face.