User login

Integrated PrEP and ART prevents HIV transmission in couples

In committed couples, HIV transmission from positive partners dropped from an expected incidence of more than 5% to less than 0.5% per year when the uninfected partner used pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the first 6 months of the infected partner’s antiretroviral therapy, according to a study in PLOS Medicine.

The open-label demonstration project on which the study reports involved 1,013 heterosexual HIV-1–serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda (PLOS Med. 2016 Aug 23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002099).

“To our knowledge, this study is one of the first and one of the largest demonstration projects to provide PrEP to a priority population at risk for HIV-1 outside of a clinical trial setting, and the findings demonstrate the feasibility and impact of using PrEP as a bridging strategy to sustained HIV-1 protection by ART [antiretroviral therapy]” in serodiscordant couples, said investigators led by Jared Baeten, MD, of the department of global health at the University of Washington, Seattle. Wide-scale roll-out “could have substantial effects in reducing the global burden of new HIV-1 infections,” Dr. Baeten and his coauthors concluded.

PrEP kept uninfected partners safe until ART reliably suppressed viral loads at about 6 months. Adherence to the regimen was about 85%, which was higher than in some clinical trials, perhaps because couples were being offered “a strategy with demonstrated safety and efficacy” instead of unproven products and placebo. Couples also recognized their elevated HIV risk, the research team said.

It was good to find out that the approach works in real-world settings in Africa, Dr. Baeten and his associates said, where the majority of the 2 million people infected each year live. Follow-up was less frequent than in trials, with brief counseling sessions “equivalent to what would be expected in public health settings” and HIV tests about every 4 months over a median of about a year. “This study shows that a practical delivery approach ... can virtually eliminate HIV1- transmission,” the researchers said.

There were just two HIV transmissions in the study, both in women with self-reported and objective evidence of interrupted PrEP use. Overall, the transmission incidence was 0.2/100 person-years. The investigators estimated there would have been 40 transmissions – 5.2/100 person-years – without the intervention.

Couples were recruited by community outreach in four cities and towns – Kisumu and Thika in Kenya, and Kabwohe and Kampala in Uganda. The investigators targeted couples at high risk for transmission, including those reporting unprotected sex and infected partners with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of 50,000 copies/mL or more.

Almost all were married and living together. They reported a median of six sex acts per month, many unprotected. Partners were a median of about 30 years old, and 67% of uninfected partners were men.

The preferred ART regimen was tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), lamivudine, and efavirenz, with zidovudine and nevirapine as alternatives. PrEP was a combination emtricitabine/TDF 200 mg/300 mg once daily; it was provided at the study sites since PrEP was otherwise unavailable in Kenya and Uganda.

The National Institutes of Health, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and U.S. Agency for International Development funded the work. Gilead Sciences donated the TDF for PrEP. Dr. Baeten had no disclosures; another author reported funding from Gilead for a TDF pharmacokinetics study, and has a patent pending for a formulation different from the drug used in the study.

In committed couples, HIV transmission from positive partners dropped from an expected incidence of more than 5% to less than 0.5% per year when the uninfected partner used pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the first 6 months of the infected partner’s antiretroviral therapy, according to a study in PLOS Medicine.

The open-label demonstration project on which the study reports involved 1,013 heterosexual HIV-1–serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda (PLOS Med. 2016 Aug 23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002099).

“To our knowledge, this study is one of the first and one of the largest demonstration projects to provide PrEP to a priority population at risk for HIV-1 outside of a clinical trial setting, and the findings demonstrate the feasibility and impact of using PrEP as a bridging strategy to sustained HIV-1 protection by ART [antiretroviral therapy]” in serodiscordant couples, said investigators led by Jared Baeten, MD, of the department of global health at the University of Washington, Seattle. Wide-scale roll-out “could have substantial effects in reducing the global burden of new HIV-1 infections,” Dr. Baeten and his coauthors concluded.

PrEP kept uninfected partners safe until ART reliably suppressed viral loads at about 6 months. Adherence to the regimen was about 85%, which was higher than in some clinical trials, perhaps because couples were being offered “a strategy with demonstrated safety and efficacy” instead of unproven products and placebo. Couples also recognized their elevated HIV risk, the research team said.

It was good to find out that the approach works in real-world settings in Africa, Dr. Baeten and his associates said, where the majority of the 2 million people infected each year live. Follow-up was less frequent than in trials, with brief counseling sessions “equivalent to what would be expected in public health settings” and HIV tests about every 4 months over a median of about a year. “This study shows that a practical delivery approach ... can virtually eliminate HIV1- transmission,” the researchers said.

There were just two HIV transmissions in the study, both in women with self-reported and objective evidence of interrupted PrEP use. Overall, the transmission incidence was 0.2/100 person-years. The investigators estimated there would have been 40 transmissions – 5.2/100 person-years – without the intervention.

Couples were recruited by community outreach in four cities and towns – Kisumu and Thika in Kenya, and Kabwohe and Kampala in Uganda. The investigators targeted couples at high risk for transmission, including those reporting unprotected sex and infected partners with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of 50,000 copies/mL or more.

Almost all were married and living together. They reported a median of six sex acts per month, many unprotected. Partners were a median of about 30 years old, and 67% of uninfected partners were men.

The preferred ART regimen was tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), lamivudine, and efavirenz, with zidovudine and nevirapine as alternatives. PrEP was a combination emtricitabine/TDF 200 mg/300 mg once daily; it was provided at the study sites since PrEP was otherwise unavailable in Kenya and Uganda.

The National Institutes of Health, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and U.S. Agency for International Development funded the work. Gilead Sciences donated the TDF for PrEP. Dr. Baeten had no disclosures; another author reported funding from Gilead for a TDF pharmacokinetics study, and has a patent pending for a formulation different from the drug used in the study.

In committed couples, HIV transmission from positive partners dropped from an expected incidence of more than 5% to less than 0.5% per year when the uninfected partner used pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the first 6 months of the infected partner’s antiretroviral therapy, according to a study in PLOS Medicine.

The open-label demonstration project on which the study reports involved 1,013 heterosexual HIV-1–serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda (PLOS Med. 2016 Aug 23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002099).

“To our knowledge, this study is one of the first and one of the largest demonstration projects to provide PrEP to a priority population at risk for HIV-1 outside of a clinical trial setting, and the findings demonstrate the feasibility and impact of using PrEP as a bridging strategy to sustained HIV-1 protection by ART [antiretroviral therapy]” in serodiscordant couples, said investigators led by Jared Baeten, MD, of the department of global health at the University of Washington, Seattle. Wide-scale roll-out “could have substantial effects in reducing the global burden of new HIV-1 infections,” Dr. Baeten and his coauthors concluded.

PrEP kept uninfected partners safe until ART reliably suppressed viral loads at about 6 months. Adherence to the regimen was about 85%, which was higher than in some clinical trials, perhaps because couples were being offered “a strategy with demonstrated safety and efficacy” instead of unproven products and placebo. Couples also recognized their elevated HIV risk, the research team said.

It was good to find out that the approach works in real-world settings in Africa, Dr. Baeten and his associates said, where the majority of the 2 million people infected each year live. Follow-up was less frequent than in trials, with brief counseling sessions “equivalent to what would be expected in public health settings” and HIV tests about every 4 months over a median of about a year. “This study shows that a practical delivery approach ... can virtually eliminate HIV1- transmission,” the researchers said.

There were just two HIV transmissions in the study, both in women with self-reported and objective evidence of interrupted PrEP use. Overall, the transmission incidence was 0.2/100 person-years. The investigators estimated there would have been 40 transmissions – 5.2/100 person-years – without the intervention.

Couples were recruited by community outreach in four cities and towns – Kisumu and Thika in Kenya, and Kabwohe and Kampala in Uganda. The investigators targeted couples at high risk for transmission, including those reporting unprotected sex and infected partners with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of 50,000 copies/mL or more.

Almost all were married and living together. They reported a median of six sex acts per month, many unprotected. Partners were a median of about 30 years old, and 67% of uninfected partners were men.

The preferred ART regimen was tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), lamivudine, and efavirenz, with zidovudine and nevirapine as alternatives. PrEP was a combination emtricitabine/TDF 200 mg/300 mg once daily; it was provided at the study sites since PrEP was otherwise unavailable in Kenya and Uganda.

The National Institutes of Health, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and U.S. Agency for International Development funded the work. Gilead Sciences donated the TDF for PrEP. Dr. Baeten had no disclosures; another author reported funding from Gilead for a TDF pharmacokinetics study, and has a patent pending for a formulation different from the drug used in the study.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Key clinical point: In committed couples, HIV transmission from positive partners dropped from an expected incidence of more than 5% to less than 0.5% per year when the uninfected partner used pre-exposure prophylaxis for the first 6 months of the infected partner’s antiretroviral therapy.

Major finding: The transmission incidence was 0.2/100 person-years. The investigators estimated there would have been 40 transmissions – 5.2/100 person-years – without the intervention.

Data source: Open-label demonstration project with 1,013 heterosexual HIV-1–serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and U.S. Agency for International Development funded the work. Gilead Sciences donated the TDF for PrEP. Dr. Baeten had no disclosures; another author reported funding from Gilead for a TDF pharmacokinetics study and has a patent pending for a formulation different from the drug used in the study.

Better use of lab testing tools needed to beat HIV/AIDS

Major improvements in HIV laboratory capacity utilization are needed in low- and middle-income countries if the global UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets for HIV and AIDS diagnosis and treatment are to be met, according to a World Health Organization study.

The study, based on 3 years of WHO survey data from 127 countries (not including the United States), says achieving the 90-90-90 targets depends heavily on improved access to high-quality testing for early infant diagnosis and treatment monitoring. The availability of “cluster of differentiation 4” (CD4) and viral load testing instruments currently meets the needs of individuals living with HIV/AIDS, but the tests are not being utilized to their full potential.

“Expanding access to treatment requires high-quality HIV testing technologies, including CD4 to assess risk of disease progression, viral load testing to monitor treatment efficacy, early infant diagnosis to determine HIV-infection status in HIV-exposed children, and other monitoring capabilities within a tiered laboratory network,” wrote Vincent Habiyambere, MD, of the WHO in Geneva and his colleagues in a study published online Aug. 23 in PLOS Medicine.

Overall, 13.7% of existing CD4 testing capacity and 36.5% of existing viral load capacity were used in 2013. In addition, 7.4% of existing CD4 instruments and 10% of viral load instruments were not in use by the end of 2013 because of several factors including lack of reagents, improperly installed or destroyed equipment, and lack of staff training.

The survey results were limited by underreporting in some programs and the collection of data from the public sector only, the researchers noted. But the data suggest that “regardless of the need for point of care, it is clear that laboratory-based monitoring will remain a key component of HIV programmes now and in the future,” the authors said. “With laboratory systems in reporting countries expanding, a national laboratory strategic plan to strengthen services must be developed, implemented, and monitored by governments and their international partners.”

Read the full study in PLOS Medicine (doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002088).

Major improvements in HIV laboratory capacity utilization are needed in low- and middle-income countries if the global UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets for HIV and AIDS diagnosis and treatment are to be met, according to a World Health Organization study.

The study, based on 3 years of WHO survey data from 127 countries (not including the United States), says achieving the 90-90-90 targets depends heavily on improved access to high-quality testing for early infant diagnosis and treatment monitoring. The availability of “cluster of differentiation 4” (CD4) and viral load testing instruments currently meets the needs of individuals living with HIV/AIDS, but the tests are not being utilized to their full potential.

“Expanding access to treatment requires high-quality HIV testing technologies, including CD4 to assess risk of disease progression, viral load testing to monitor treatment efficacy, early infant diagnosis to determine HIV-infection status in HIV-exposed children, and other monitoring capabilities within a tiered laboratory network,” wrote Vincent Habiyambere, MD, of the WHO in Geneva and his colleagues in a study published online Aug. 23 in PLOS Medicine.

Overall, 13.7% of existing CD4 testing capacity and 36.5% of existing viral load capacity were used in 2013. In addition, 7.4% of existing CD4 instruments and 10% of viral load instruments were not in use by the end of 2013 because of several factors including lack of reagents, improperly installed or destroyed equipment, and lack of staff training.

The survey results were limited by underreporting in some programs and the collection of data from the public sector only, the researchers noted. But the data suggest that “regardless of the need for point of care, it is clear that laboratory-based monitoring will remain a key component of HIV programmes now and in the future,” the authors said. “With laboratory systems in reporting countries expanding, a national laboratory strategic plan to strengthen services must be developed, implemented, and monitored by governments and their international partners.”

Read the full study in PLOS Medicine (doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002088).

Major improvements in HIV laboratory capacity utilization are needed in low- and middle-income countries if the global UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets for HIV and AIDS diagnosis and treatment are to be met, according to a World Health Organization study.

The study, based on 3 years of WHO survey data from 127 countries (not including the United States), says achieving the 90-90-90 targets depends heavily on improved access to high-quality testing for early infant diagnosis and treatment monitoring. The availability of “cluster of differentiation 4” (CD4) and viral load testing instruments currently meets the needs of individuals living with HIV/AIDS, but the tests are not being utilized to their full potential.

“Expanding access to treatment requires high-quality HIV testing technologies, including CD4 to assess risk of disease progression, viral load testing to monitor treatment efficacy, early infant diagnosis to determine HIV-infection status in HIV-exposed children, and other monitoring capabilities within a tiered laboratory network,” wrote Vincent Habiyambere, MD, of the WHO in Geneva and his colleagues in a study published online Aug. 23 in PLOS Medicine.

Overall, 13.7% of existing CD4 testing capacity and 36.5% of existing viral load capacity were used in 2013. In addition, 7.4% of existing CD4 instruments and 10% of viral load instruments were not in use by the end of 2013 because of several factors including lack of reagents, improperly installed or destroyed equipment, and lack of staff training.

The survey results were limited by underreporting in some programs and the collection of data from the public sector only, the researchers noted. But the data suggest that “regardless of the need for point of care, it is clear that laboratory-based monitoring will remain a key component of HIV programmes now and in the future,” the authors said. “With laboratory systems in reporting countries expanding, a national laboratory strategic plan to strengthen services must be developed, implemented, and monitored by governments and their international partners.”

Read the full study in PLOS Medicine (doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002088).

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

AGA receives NIH funding for national FMT registry

After years of planning and behind-the-scenes discussions, the AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education is thrilled to announce that it has received NIH funding for the first-ever national registry documenting the use of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT).

The AGA Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry – which aims to begin collecting data in early 2017 – will gather clinical data from both stool donors and FMT recipients for the following purposes:

1. To assess short- and long-term safety.

2. To gather information on practice in the U.S. and assess effectiveness of the intervention.

3. To promote scientific investigation.

4. To aid practitioners and sponsors in satisfying regulatory requirements.

For more information, read the AGA press release announcing the registry. Stay tuned for additional information from the center on what this means for physicians practicing FMT and researchers studying FMT.

After years of planning and behind-the-scenes discussions, the AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education is thrilled to announce that it has received NIH funding for the first-ever national registry documenting the use of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT).

The AGA Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry – which aims to begin collecting data in early 2017 – will gather clinical data from both stool donors and FMT recipients for the following purposes:

1. To assess short- and long-term safety.

2. To gather information on practice in the U.S. and assess effectiveness of the intervention.

3. To promote scientific investigation.

4. To aid practitioners and sponsors in satisfying regulatory requirements.

For more information, read the AGA press release announcing the registry. Stay tuned for additional information from the center on what this means for physicians practicing FMT and researchers studying FMT.

After years of planning and behind-the-scenes discussions, the AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education is thrilled to announce that it has received NIH funding for the first-ever national registry documenting the use of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT).

The AGA Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry – which aims to begin collecting data in early 2017 – will gather clinical data from both stool donors and FMT recipients for the following purposes:

1. To assess short- and long-term safety.

2. To gather information on practice in the U.S. and assess effectiveness of the intervention.

3. To promote scientific investigation.

4. To aid practitioners and sponsors in satisfying regulatory requirements.

For more information, read the AGA press release announcing the registry. Stay tuned for additional information from the center on what this means for physicians practicing FMT and researchers studying FMT.

Power morcellation dropped, abdominal hysterectomy increased after FDA warning

Electric power morcellation during hysterectomy declined sharply after the Food and Drug Administration discouraged use of the technique in April 2014 and then recommended against it for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women in November 2014. At the same time, use of abdominal hysterectomy increased, according to a new analysis.

The FDA took these actions because of concern that intraoperative morcellation could inadvertently expose healthy abdominal tissue to contamination from occult uterine malignancies. But some clinicians warned that avoiding morcellation would lead to a greater number of hysterectomies via laparotomy, with an attendant increase in surgical complications.

To assess the effect of the FDA recommendations, Jason D. Wright, MD, of the division of gynecologic oncology, Columbia University, New York, and his colleagues analyzed time trends in hysterectomy and morcellation during nine 3-month periods before and after the FDA announcements. They used information from a national database that covers more than 500 hospitals across the country, including in their analysis 203,520 women aged 18-95 years (mean age, 48 years) who underwent hysterectomy during the study period.

Among the 117,653 minimally invasive hysterectomies performed, the use of electric power morcellation rose slightly during 2013, peaking at 13.7% in the fourth quarter of that year. It then declined precipitously, to a low of 2.8% by the last 3-month period assessed, which was the first quarter of 2015. Simultaneously, the use of abdominal hysterectomy increased from 27.1% of procedures in early 2013 to 31.8% by the last 3-month period assessed, the researchers reported (JAMA 2016;316:877-8).

However, despite the increase in abdominal procedures, the complication rate did not change over time. It was 8.3% during the first quarter studied and 8.4% during the last. In fact, the rate of complications during abdominal hysterectomy also declined, from 18.4% to 17.6%. Similarly, the rate of complications during minimally invasive hysterectomy dropped from 4.4% to 4.1%, and the complication rate decreased from 4.7% to 4.2% during vaginal hysterectomy.

The researchers noted that the prevalence of uterine cancer, endometrial hyperplasia, other gynecologic cancers, and uterine tumors of indeterminate behavior were unchanged during the study period among women who underwent minimally invasive hysterectomy with power morcellation.

“The FDA warnings might result in a lower prevalence of cancer among women who underwent morcellation due to greater scrutiny on patient selection. However, the high rate of abnormal pathology after the warnings highlights the difficulty in the preoperative detection of uterine pathology,” the researchers wrote. “Continued caution is needed to limit the inadvertent morcellation of uterine pathology.”

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

I read with interest “Trends in Use and Outcomes of Women Undergoing Hysterectomy With Electric Power Morcellation,” by Jason D. Wright and colleagues, published in JAMA. As expected, with the concerns raised by the FDA regarding electric power morcellation, there has been a statistically significant reduction in a laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy (59.2% to 56.2%) and an even more marked decrease in use of electric power morcellation (13.7% to 2.8%).

|

Dr. Charles E. Miller |

Interestingly, the increase in abdominal hysterectomy (27.1% to 31.8%) appears to be secondary not only to the reduction in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, but vaginal hysterectomy as well. While the decrease in vaginal hysterectomy, is, in part, likely due to the trend away from this technique, it is probably also due to the concern of cutting up a potential sarcoma during the procedure to deliver the large fibroid uterus. This would be supported by the fact that the greatest percentage drop in vaginal hysterectomy occurred in Q1-Q2 2014 at the time the FDA issued its safety concern.

In a study by Matthew Siedhoff, MD, et al. (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 May;212[5]:591.e1-8), utilizing a decision tree model, Dr. Siedhoff anticipated that severe complications would increase with conversion of a minimally invasive approach to laparotomy. While according to Wright et al., there is no increase noted in complications per se, there is no indication as to severity of complications. Thus, while overall complications have not increased, perhaps severe complications have, in fact, increased as anticipated by Siedhoff et al. Furthermore, impact on quality of life is not considered (i.e. hospitalization, convalescence at home, etc.) in this study, but is a well known difference between minimally invasive surgery and open surgery.

Charles E. Miller, MD, is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois, and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill. Dr. Miller reported that he is working on a study with Espiner Medical Ltd. to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a bag that is utilized for contained electric power morcellation. Karl Storz is sponsoring the study.

I read with interest “Trends in Use and Outcomes of Women Undergoing Hysterectomy With Electric Power Morcellation,” by Jason D. Wright and colleagues, published in JAMA. As expected, with the concerns raised by the FDA regarding electric power morcellation, there has been a statistically significant reduction in a laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy (59.2% to 56.2%) and an even more marked decrease in use of electric power morcellation (13.7% to 2.8%).

|

Dr. Charles E. Miller |

Interestingly, the increase in abdominal hysterectomy (27.1% to 31.8%) appears to be secondary not only to the reduction in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, but vaginal hysterectomy as well. While the decrease in vaginal hysterectomy, is, in part, likely due to the trend away from this technique, it is probably also due to the concern of cutting up a potential sarcoma during the procedure to deliver the large fibroid uterus. This would be supported by the fact that the greatest percentage drop in vaginal hysterectomy occurred in Q1-Q2 2014 at the time the FDA issued its safety concern.

In a study by Matthew Siedhoff, MD, et al. (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 May;212[5]:591.e1-8), utilizing a decision tree model, Dr. Siedhoff anticipated that severe complications would increase with conversion of a minimally invasive approach to laparotomy. While according to Wright et al., there is no increase noted in complications per se, there is no indication as to severity of complications. Thus, while overall complications have not increased, perhaps severe complications have, in fact, increased as anticipated by Siedhoff et al. Furthermore, impact on quality of life is not considered (i.e. hospitalization, convalescence at home, etc.) in this study, but is a well known difference between minimally invasive surgery and open surgery.

Charles E. Miller, MD, is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois, and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill. Dr. Miller reported that he is working on a study with Espiner Medical Ltd. to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a bag that is utilized for contained electric power morcellation. Karl Storz is sponsoring the study.

I read with interest “Trends in Use and Outcomes of Women Undergoing Hysterectomy With Electric Power Morcellation,” by Jason D. Wright and colleagues, published in JAMA. As expected, with the concerns raised by the FDA regarding electric power morcellation, there has been a statistically significant reduction in a laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy (59.2% to 56.2%) and an even more marked decrease in use of electric power morcellation (13.7% to 2.8%).

|

Dr. Charles E. Miller |

Interestingly, the increase in abdominal hysterectomy (27.1% to 31.8%) appears to be secondary not only to the reduction in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, but vaginal hysterectomy as well. While the decrease in vaginal hysterectomy, is, in part, likely due to the trend away from this technique, it is probably also due to the concern of cutting up a potential sarcoma during the procedure to deliver the large fibroid uterus. This would be supported by the fact that the greatest percentage drop in vaginal hysterectomy occurred in Q1-Q2 2014 at the time the FDA issued its safety concern.

In a study by Matthew Siedhoff, MD, et al. (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 May;212[5]:591.e1-8), utilizing a decision tree model, Dr. Siedhoff anticipated that severe complications would increase with conversion of a minimally invasive approach to laparotomy. While according to Wright et al., there is no increase noted in complications per se, there is no indication as to severity of complications. Thus, while overall complications have not increased, perhaps severe complications have, in fact, increased as anticipated by Siedhoff et al. Furthermore, impact on quality of life is not considered (i.e. hospitalization, convalescence at home, etc.) in this study, but is a well known difference between minimally invasive surgery and open surgery.

Charles E. Miller, MD, is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois, and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill. Dr. Miller reported that he is working on a study with Espiner Medical Ltd. to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a bag that is utilized for contained electric power morcellation. Karl Storz is sponsoring the study.

Electric power morcellation during hysterectomy declined sharply after the Food and Drug Administration discouraged use of the technique in April 2014 and then recommended against it for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women in November 2014. At the same time, use of abdominal hysterectomy increased, according to a new analysis.

The FDA took these actions because of concern that intraoperative morcellation could inadvertently expose healthy abdominal tissue to contamination from occult uterine malignancies. But some clinicians warned that avoiding morcellation would lead to a greater number of hysterectomies via laparotomy, with an attendant increase in surgical complications.

To assess the effect of the FDA recommendations, Jason D. Wright, MD, of the division of gynecologic oncology, Columbia University, New York, and his colleagues analyzed time trends in hysterectomy and morcellation during nine 3-month periods before and after the FDA announcements. They used information from a national database that covers more than 500 hospitals across the country, including in their analysis 203,520 women aged 18-95 years (mean age, 48 years) who underwent hysterectomy during the study period.

Among the 117,653 minimally invasive hysterectomies performed, the use of electric power morcellation rose slightly during 2013, peaking at 13.7% in the fourth quarter of that year. It then declined precipitously, to a low of 2.8% by the last 3-month period assessed, which was the first quarter of 2015. Simultaneously, the use of abdominal hysterectomy increased from 27.1% of procedures in early 2013 to 31.8% by the last 3-month period assessed, the researchers reported (JAMA 2016;316:877-8).

However, despite the increase in abdominal procedures, the complication rate did not change over time. It was 8.3% during the first quarter studied and 8.4% during the last. In fact, the rate of complications during abdominal hysterectomy also declined, from 18.4% to 17.6%. Similarly, the rate of complications during minimally invasive hysterectomy dropped from 4.4% to 4.1%, and the complication rate decreased from 4.7% to 4.2% during vaginal hysterectomy.

The researchers noted that the prevalence of uterine cancer, endometrial hyperplasia, other gynecologic cancers, and uterine tumors of indeterminate behavior were unchanged during the study period among women who underwent minimally invasive hysterectomy with power morcellation.

“The FDA warnings might result in a lower prevalence of cancer among women who underwent morcellation due to greater scrutiny on patient selection. However, the high rate of abnormal pathology after the warnings highlights the difficulty in the preoperative detection of uterine pathology,” the researchers wrote. “Continued caution is needed to limit the inadvertent morcellation of uterine pathology.”

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Electric power morcellation during hysterectomy declined sharply after the Food and Drug Administration discouraged use of the technique in April 2014 and then recommended against it for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women in November 2014. At the same time, use of abdominal hysterectomy increased, according to a new analysis.

The FDA took these actions because of concern that intraoperative morcellation could inadvertently expose healthy abdominal tissue to contamination from occult uterine malignancies. But some clinicians warned that avoiding morcellation would lead to a greater number of hysterectomies via laparotomy, with an attendant increase in surgical complications.

To assess the effect of the FDA recommendations, Jason D. Wright, MD, of the division of gynecologic oncology, Columbia University, New York, and his colleagues analyzed time trends in hysterectomy and morcellation during nine 3-month periods before and after the FDA announcements. They used information from a national database that covers more than 500 hospitals across the country, including in their analysis 203,520 women aged 18-95 years (mean age, 48 years) who underwent hysterectomy during the study period.

Among the 117,653 minimally invasive hysterectomies performed, the use of electric power morcellation rose slightly during 2013, peaking at 13.7% in the fourth quarter of that year. It then declined precipitously, to a low of 2.8% by the last 3-month period assessed, which was the first quarter of 2015. Simultaneously, the use of abdominal hysterectomy increased from 27.1% of procedures in early 2013 to 31.8% by the last 3-month period assessed, the researchers reported (JAMA 2016;316:877-8).

However, despite the increase in abdominal procedures, the complication rate did not change over time. It was 8.3% during the first quarter studied and 8.4% during the last. In fact, the rate of complications during abdominal hysterectomy also declined, from 18.4% to 17.6%. Similarly, the rate of complications during minimally invasive hysterectomy dropped from 4.4% to 4.1%, and the complication rate decreased from 4.7% to 4.2% during vaginal hysterectomy.

The researchers noted that the prevalence of uterine cancer, endometrial hyperplasia, other gynecologic cancers, and uterine tumors of indeterminate behavior were unchanged during the study period among women who underwent minimally invasive hysterectomy with power morcellation.

“The FDA warnings might result in a lower prevalence of cancer among women who underwent morcellation due to greater scrutiny on patient selection. However, the high rate of abnormal pathology after the warnings highlights the difficulty in the preoperative detection of uterine pathology,” the researchers wrote. “Continued caution is needed to limit the inadvertent morcellation of uterine pathology.”

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Electric power morcellation declined after the FDA recommended against using the technique during hysterectomy.

Major finding: Use of electric power morcellation peaked at 13.7% before the FDA recommendations, then declined to a low of 2.8%.

Data source: A retrospective database analysis involving 203,520 hysterectomies performed at more than 500 U.S. hospitals during 2013-2015.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute funded the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Herpes Zoster in Children

Herpes zoster (HZ) is commonly seen in immunocompromised patients but is quite uncommon in immunocompetent children. Pediatric cases have been attributed to 1 of 3 primary exposures: intrauterine exposure to the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), postuterine exposure to wild-type VZV, or exposure due to vaccination with the live-attenuated strain of the virus.1

We report a case of HZ in an immunocompetent pediatric patient soon after routine VZV vaccination. We also review the literature on the incidence, clinical characteristics, and diagnostic aids for pediatric cases of HZ.

Case Report

A 15-month-old boy who was previously healthy presented with a red vesicular rash on the right upper cheek of 3 days’ duration. The patient was otherwise asymptomatic and had no constitutional symptoms. The patient’s mother reported an uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery with no history of maternal VZV infection. There was no known exposure to other individuals with VZV or a history of a similar rash. The patient was up-to-date on his immunizations, which included the VZV vaccine at 12 months of age.

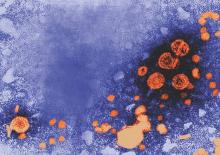

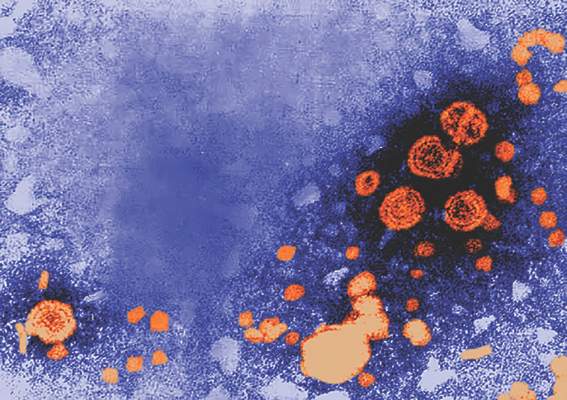

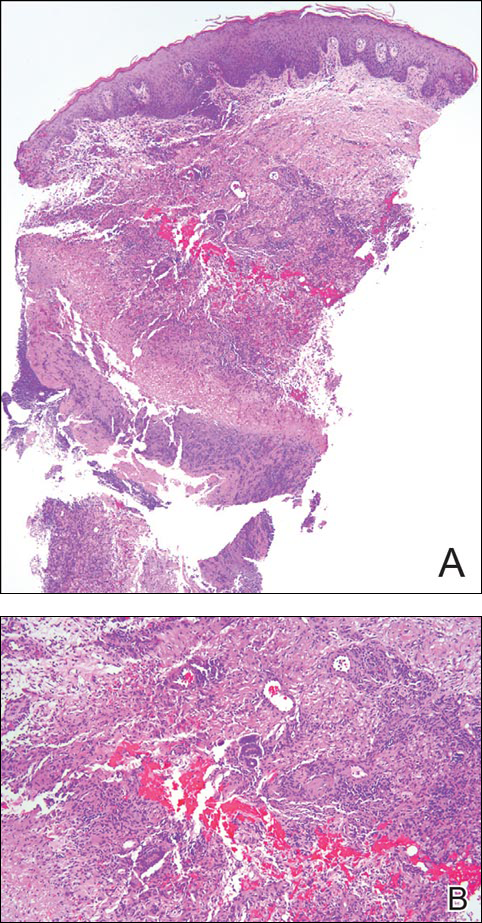

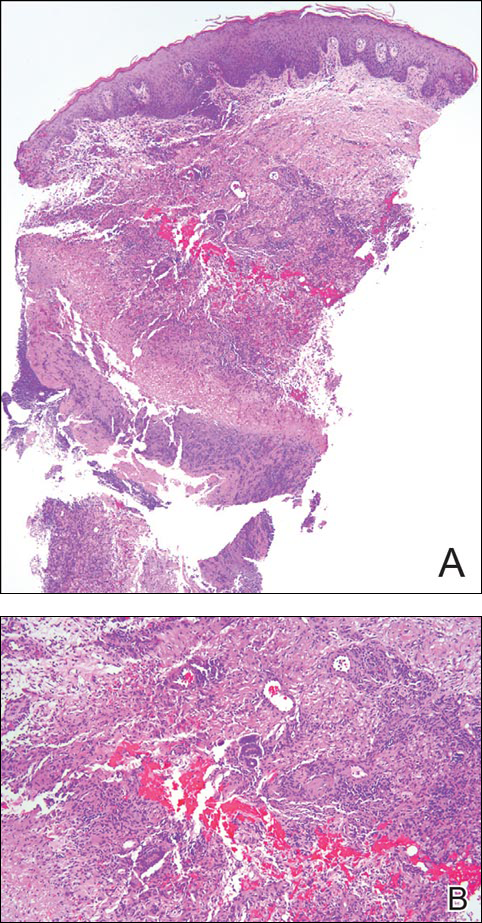

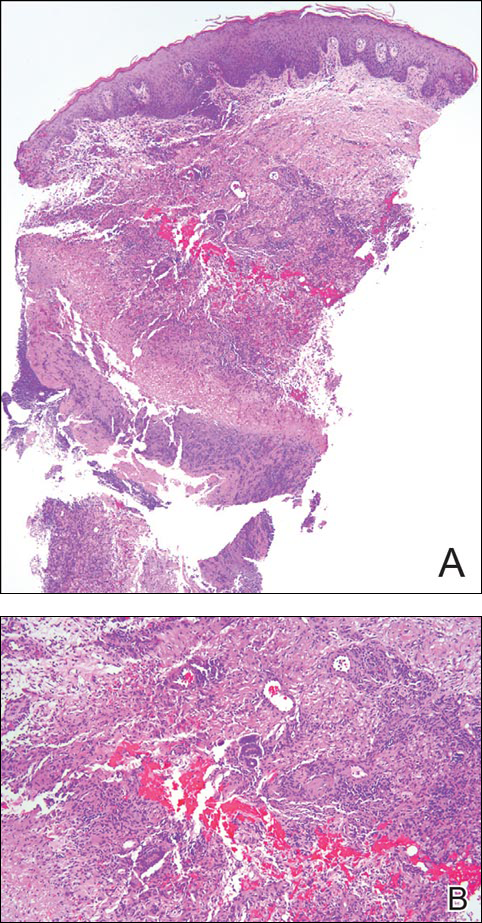

Physical examination revealed vesicles and pustules with an erythematous base on the right zygoma extending to the right lateral canthus and upper eyelid in a dermatomal distribution (Figure). No lesions were present on any other area of the body. One group of vesicles was ruptured with a polyester-tipped applicator and submitted for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis for suspected VZV infection. An ophthalmology evaluation revealed no ocular involvement.

Although no complications were noted on the ophthalmologist’s initial examination or at the follow-up visit, 1 month later the patient’s father noted a “cloudy change” to the right eye. The patient had several subsequent evaluations with ophthalmologists and was treated for HZ ophthalmicus with acyclovir over the following 10 months. The patient’s mother reported eventual clearance of the eye findings without permanent visual sequelae. She stated that the PCR results documenting VZV positivity were extremely helpful for the ophthalmologist in establishing a diagnosis and treatment plan.

Comment

Varicella-zoster virus is 1 of 8 viruses in the Herpesviridae family known to infect humans. It is known to cause 2 distinct disease states: varicella (chickenpox) due to a primary infection from the virus, and HZ (shingles) caused by a reactivation of the latent virus in the dorsal root ganglion, which then travels the neural pathway and manifests cutaneously along 1 to 2 dermatomes.1 This recurrence is possible in infants, children, and adults via 1 of 3 routes of exposure.

The overall incidence of HZ is lower in children compared to adults, and the risk dramatically increases in individuals older than 50 years. Evidence also shows that exposure to VZV before 1 year of age increases the lifetime risk for HZ.2,3 Children aged 1 to 18 years who were evaluated for HZ demonstrated a decreased incidence among those who were vaccinated versus those who were not.4,5 Interestingly, there was an increased incidence of HZ among children aged 1 to 2 years who had been vaccinated. Based on PCR analysis, it was noted that HZ was attributed to the vaccine-related strain of VZV in 92% of 1- to 2-year-old patients.4

There is some concern that the varicella vaccination program implemented in 1995 has led to increased rates of HZ. The literature presents mixed reports. Some studies showed an overall increased incidence of HZ,6,7 and 2 other studies showed no increase in the incidence of HZ.4,8 More recent studies have demonstrated that vaccination may have a protective effect against HZ.4-6,9 In a 2013 study in which HZ samples were tested by PCR analysis to determine the strains of VZV that were responsible for an HZ outbreak in children aged 1 to 18 years, the HZ incidence was 48 per 100,000 person-years in patients who were vaccinated versus 230 per 100,000 person-years in patients who were not vaccinated. Among the subset of patients who were vaccinated (n=118), 52% of the HZ lesions were from the wild-type strain.4

Clinical Characteristics

The typical presentation of HZ includes grouped vesicles or small bullae on an erythematous base that occur unilaterally within the distribution of a cranial or spinal sensory nerve, occasionally with overflow into the dermatomes above and below, typically without crossing the midline.8 The most frequent distributions in descending order are thoracic, cranial (mostly trigeminal), lumbar, and sacral. Pain in the dermatome may never occur, may precede, may occur during, or may even occur after the eruption. The initial presentation involves papules and plaques that develop blisters within hours of their development. Lesions continue to appear for several days and may coalesce. The lesions may become hemorrhagic, necrotic, or bullous, with or without adenopathy. Rarely, there can be pain without the associated skin eruption (zoster sine herpete). Lesions tend to crust by days 7 to 10.8

Herpes zoster typically affects children to a lesser extent than adults. The disease state often is milder in children with a decreased likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia.10 However, there are documented cases of severe sequelae secondary to zoster infection in pediatric patients, including but not limited to disseminated HZ,8 HZ ophthalmicus,11,12 Ramsay Hunt syndrome,8 and chronic encephalitis.8 In the adult population, ocular involvement will present in 33% to 50% of cases that involve the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve without clinical involvement of the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic nerve. Involvement of the nasociliary branch will lead to ocular pathology in an estimated 76% to 100% of adult cases.13,14 It is unknown if this rate is the same in the pediatric population, but it highlights the importance of educating patients and/or guardians about possible complications. It also demonstrates the importance of including HZ in the differential diagnosis for pediatric patients presenting with papular or vesicular skin eruptions, particularly in the area of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

Diagnosis

Herpes zoster usually is diagnosed based on its clinical presentation. Human herpesvirus 1 or 2 also may present with similar lesions and should be included in the differential diagnosis. To confirm a clinical diagnosis, additional testing may be done. A Tzanck smear historically has been the least expensive and most rapid test. Scrapings can be taken from the base of a vesicle, stained, and examined for multinucleated giant cells; however, a Tzanck smear cannot help in distinguishing herpes simplex virus from VZV. Direct fluorescent antibody testing and viral culture are less rapid but are standard tests that may help with the diagnosis. Direct fluorescent antibody testing can have a high false-negative rate, and viral cultures typically take 2 weeks for completion. These tests have largely been replaced by PCR analysis. Polymerase chain reaction has been the most sensitive test developed yet. With recent advances, real-time PCR, which can be performed within 1 hour in small hospital laboratories,15 has become more readily available and much more rapid than standard PCR. Further PCR testing can differentiate between the 2 possible infective strains (wild-type vs vaccine related).16 Real-time PCR is now commonly used as the first-line ancillary diagnostic test after physical examination.17

Conclusion

Although uncommon, HZ does occur in immunocompetent children and should be included in the differential diagnosis in children with vesicular lesions. Herpes zoster is a reactivation of VZV and initial exposure may be from the wild-type or vaccine-related strains. Clinicians must be vigilant in their evaluation of vesicular lesions in children even without known varicella exposure. Polymerase chain reaction testing can be helpful to distinguish between herpes simplex lesions and VZV. Polymerase chain reaction testing also may be of benefit to determine the strain of VZV infection.

- Myers MG, Seward JF, LaRussa PS. Varicella-zoster virus. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:1104-1105.

- Terada K, Kawano S, Yoshihiro K, et al. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) reactivation is related to the low response of VZV-specific immunity after chickenpox in infancy. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:650-652.

- Takayama N, Yamada H, Kaku H, et al. Herpes zoster in immunocompetent and immunocompromised Japanese children. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:275-279.

- Weinmann S, Chun C, Schmid DS, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children in the varicella vaccine era, 2005-2009. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1859-1868.

- Civen R, Lopez AS, Zhang J, et al. Varicella outbreak epidemiology in an active surveillance site, 1995–2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S114-S119.

- Russell ML, Dover DC, Simmonds KA, et al. Shingles in Alberta: before and after publicly funded varicella vaccination. Vaccine. 2014;32:6319-6324.

- Goldman GS, King PG. Review of the United States universal varicella vaccination program: herpes zoster incidence rates, cost-effectiveness, and vaccine efficacy based primarily on the Antelope Valley Varicella Active Surveillance Project data. Vaccine. 2013;31:1680-1694.

- Arikawa J, Asahi T, Au WY, et al. Zoster (shingles, herpes zoster). In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:372-376.

- Guris D, Jumaan AO, Mascola L, et al. Changing varicella epidemiology in active surveillance sites–United States, 1995-2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S71-S75.

- Petursson G, Helgason S, Gudmundsson S, et al. Herpes zoster in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:905-908.

- Oladokun RE, Olomukoro CN, Owa AB. Disseminated herpes zoster ophthalmicus in an immunocompetent 8-year-old boy. Clin Pract. 2013;3:e16.

- Lewkonia IK, Jackson AA. Infantile herpes zoster after intrauterine exposure to varicella. Br Med J. 1973;3:149.

- Zaal MJ, Völker-Dieben HJ, D’Amaro J. Prognostic value of Hutchinson’s sign in acute herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:187-191.

- Harding SP, Lipton JR, Wells JC. Natural history of herpes zoster ophthalmicus: predictors of postherpetic neuralgia and ocular involvement. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:353-358.

- Higashimoto Y, Ihira M, Ohta A, et al. Discriminating between varicella-zoster virus vaccine and wild-type strains by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2665-2670.

- Harbecke R, Oxman MN, Arnold, et al. A real-time PCR assay to identify and discriminate among wild-type and vaccine strains of varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in clinical specimens, and comparison with the clinical diagnoses. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1310-1322.

- Albrecht MA. Diagnosis of varicella-zoster infection. UpToDate website. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-of-varicella-zoster-virus-infection. Updated July 6, 2015. Accessed July 19, 2016.

Herpes zoster (HZ) is commonly seen in immunocompromised patients but is quite uncommon in immunocompetent children. Pediatric cases have been attributed to 1 of 3 primary exposures: intrauterine exposure to the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), postuterine exposure to wild-type VZV, or exposure due to vaccination with the live-attenuated strain of the virus.1

We report a case of HZ in an immunocompetent pediatric patient soon after routine VZV vaccination. We also review the literature on the incidence, clinical characteristics, and diagnostic aids for pediatric cases of HZ.

Case Report

A 15-month-old boy who was previously healthy presented with a red vesicular rash on the right upper cheek of 3 days’ duration. The patient was otherwise asymptomatic and had no constitutional symptoms. The patient’s mother reported an uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery with no history of maternal VZV infection. There was no known exposure to other individuals with VZV or a history of a similar rash. The patient was up-to-date on his immunizations, which included the VZV vaccine at 12 months of age.

Physical examination revealed vesicles and pustules with an erythematous base on the right zygoma extending to the right lateral canthus and upper eyelid in a dermatomal distribution (Figure). No lesions were present on any other area of the body. One group of vesicles was ruptured with a polyester-tipped applicator and submitted for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis for suspected VZV infection. An ophthalmology evaluation revealed no ocular involvement.

Although no complications were noted on the ophthalmologist’s initial examination or at the follow-up visit, 1 month later the patient’s father noted a “cloudy change” to the right eye. The patient had several subsequent evaluations with ophthalmologists and was treated for HZ ophthalmicus with acyclovir over the following 10 months. The patient’s mother reported eventual clearance of the eye findings without permanent visual sequelae. She stated that the PCR results documenting VZV positivity were extremely helpful for the ophthalmologist in establishing a diagnosis and treatment plan.

Comment

Varicella-zoster virus is 1 of 8 viruses in the Herpesviridae family known to infect humans. It is known to cause 2 distinct disease states: varicella (chickenpox) due to a primary infection from the virus, and HZ (shingles) caused by a reactivation of the latent virus in the dorsal root ganglion, which then travels the neural pathway and manifests cutaneously along 1 to 2 dermatomes.1 This recurrence is possible in infants, children, and adults via 1 of 3 routes of exposure.

The overall incidence of HZ is lower in children compared to adults, and the risk dramatically increases in individuals older than 50 years. Evidence also shows that exposure to VZV before 1 year of age increases the lifetime risk for HZ.2,3 Children aged 1 to 18 years who were evaluated for HZ demonstrated a decreased incidence among those who were vaccinated versus those who were not.4,5 Interestingly, there was an increased incidence of HZ among children aged 1 to 2 years who had been vaccinated. Based on PCR analysis, it was noted that HZ was attributed to the vaccine-related strain of VZV in 92% of 1- to 2-year-old patients.4

There is some concern that the varicella vaccination program implemented in 1995 has led to increased rates of HZ. The literature presents mixed reports. Some studies showed an overall increased incidence of HZ,6,7 and 2 other studies showed no increase in the incidence of HZ.4,8 More recent studies have demonstrated that vaccination may have a protective effect against HZ.4-6,9 In a 2013 study in which HZ samples were tested by PCR analysis to determine the strains of VZV that were responsible for an HZ outbreak in children aged 1 to 18 years, the HZ incidence was 48 per 100,000 person-years in patients who were vaccinated versus 230 per 100,000 person-years in patients who were not vaccinated. Among the subset of patients who were vaccinated (n=118), 52% of the HZ lesions were from the wild-type strain.4

Clinical Characteristics

The typical presentation of HZ includes grouped vesicles or small bullae on an erythematous base that occur unilaterally within the distribution of a cranial or spinal sensory nerve, occasionally with overflow into the dermatomes above and below, typically without crossing the midline.8 The most frequent distributions in descending order are thoracic, cranial (mostly trigeminal), lumbar, and sacral. Pain in the dermatome may never occur, may precede, may occur during, or may even occur after the eruption. The initial presentation involves papules and plaques that develop blisters within hours of their development. Lesions continue to appear for several days and may coalesce. The lesions may become hemorrhagic, necrotic, or bullous, with or without adenopathy. Rarely, there can be pain without the associated skin eruption (zoster sine herpete). Lesions tend to crust by days 7 to 10.8

Herpes zoster typically affects children to a lesser extent than adults. The disease state often is milder in children with a decreased likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia.10 However, there are documented cases of severe sequelae secondary to zoster infection in pediatric patients, including but not limited to disseminated HZ,8 HZ ophthalmicus,11,12 Ramsay Hunt syndrome,8 and chronic encephalitis.8 In the adult population, ocular involvement will present in 33% to 50% of cases that involve the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve without clinical involvement of the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic nerve. Involvement of the nasociliary branch will lead to ocular pathology in an estimated 76% to 100% of adult cases.13,14 It is unknown if this rate is the same in the pediatric population, but it highlights the importance of educating patients and/or guardians about possible complications. It also demonstrates the importance of including HZ in the differential diagnosis for pediatric patients presenting with papular or vesicular skin eruptions, particularly in the area of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

Diagnosis

Herpes zoster usually is diagnosed based on its clinical presentation. Human herpesvirus 1 or 2 also may present with similar lesions and should be included in the differential diagnosis. To confirm a clinical diagnosis, additional testing may be done. A Tzanck smear historically has been the least expensive and most rapid test. Scrapings can be taken from the base of a vesicle, stained, and examined for multinucleated giant cells; however, a Tzanck smear cannot help in distinguishing herpes simplex virus from VZV. Direct fluorescent antibody testing and viral culture are less rapid but are standard tests that may help with the diagnosis. Direct fluorescent antibody testing can have a high false-negative rate, and viral cultures typically take 2 weeks for completion. These tests have largely been replaced by PCR analysis. Polymerase chain reaction has been the most sensitive test developed yet. With recent advances, real-time PCR, which can be performed within 1 hour in small hospital laboratories,15 has become more readily available and much more rapid than standard PCR. Further PCR testing can differentiate between the 2 possible infective strains (wild-type vs vaccine related).16 Real-time PCR is now commonly used as the first-line ancillary diagnostic test after physical examination.17

Conclusion

Although uncommon, HZ does occur in immunocompetent children and should be included in the differential diagnosis in children with vesicular lesions. Herpes zoster is a reactivation of VZV and initial exposure may be from the wild-type or vaccine-related strains. Clinicians must be vigilant in their evaluation of vesicular lesions in children even without known varicella exposure. Polymerase chain reaction testing can be helpful to distinguish between herpes simplex lesions and VZV. Polymerase chain reaction testing also may be of benefit to determine the strain of VZV infection.

Herpes zoster (HZ) is commonly seen in immunocompromised patients but is quite uncommon in immunocompetent children. Pediatric cases have been attributed to 1 of 3 primary exposures: intrauterine exposure to the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), postuterine exposure to wild-type VZV, or exposure due to vaccination with the live-attenuated strain of the virus.1

We report a case of HZ in an immunocompetent pediatric patient soon after routine VZV vaccination. We also review the literature on the incidence, clinical characteristics, and diagnostic aids for pediatric cases of HZ.

Case Report

A 15-month-old boy who was previously healthy presented with a red vesicular rash on the right upper cheek of 3 days’ duration. The patient was otherwise asymptomatic and had no constitutional symptoms. The patient’s mother reported an uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery with no history of maternal VZV infection. There was no known exposure to other individuals with VZV or a history of a similar rash. The patient was up-to-date on his immunizations, which included the VZV vaccine at 12 months of age.

Physical examination revealed vesicles and pustules with an erythematous base on the right zygoma extending to the right lateral canthus and upper eyelid in a dermatomal distribution (Figure). No lesions were present on any other area of the body. One group of vesicles was ruptured with a polyester-tipped applicator and submitted for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis for suspected VZV infection. An ophthalmology evaluation revealed no ocular involvement.

Although no complications were noted on the ophthalmologist’s initial examination or at the follow-up visit, 1 month later the patient’s father noted a “cloudy change” to the right eye. The patient had several subsequent evaluations with ophthalmologists and was treated for HZ ophthalmicus with acyclovir over the following 10 months. The patient’s mother reported eventual clearance of the eye findings without permanent visual sequelae. She stated that the PCR results documenting VZV positivity were extremely helpful for the ophthalmologist in establishing a diagnosis and treatment plan.

Comment

Varicella-zoster virus is 1 of 8 viruses in the Herpesviridae family known to infect humans. It is known to cause 2 distinct disease states: varicella (chickenpox) due to a primary infection from the virus, and HZ (shingles) caused by a reactivation of the latent virus in the dorsal root ganglion, which then travels the neural pathway and manifests cutaneously along 1 to 2 dermatomes.1 This recurrence is possible in infants, children, and adults via 1 of 3 routes of exposure.

The overall incidence of HZ is lower in children compared to adults, and the risk dramatically increases in individuals older than 50 years. Evidence also shows that exposure to VZV before 1 year of age increases the lifetime risk for HZ.2,3 Children aged 1 to 18 years who were evaluated for HZ demonstrated a decreased incidence among those who were vaccinated versus those who were not.4,5 Interestingly, there was an increased incidence of HZ among children aged 1 to 2 years who had been vaccinated. Based on PCR analysis, it was noted that HZ was attributed to the vaccine-related strain of VZV in 92% of 1- to 2-year-old patients.4

There is some concern that the varicella vaccination program implemented in 1995 has led to increased rates of HZ. The literature presents mixed reports. Some studies showed an overall increased incidence of HZ,6,7 and 2 other studies showed no increase in the incidence of HZ.4,8 More recent studies have demonstrated that vaccination may have a protective effect against HZ.4-6,9 In a 2013 study in which HZ samples were tested by PCR analysis to determine the strains of VZV that were responsible for an HZ outbreak in children aged 1 to 18 years, the HZ incidence was 48 per 100,000 person-years in patients who were vaccinated versus 230 per 100,000 person-years in patients who were not vaccinated. Among the subset of patients who were vaccinated (n=118), 52% of the HZ lesions were from the wild-type strain.4

Clinical Characteristics

The typical presentation of HZ includes grouped vesicles or small bullae on an erythematous base that occur unilaterally within the distribution of a cranial or spinal sensory nerve, occasionally with overflow into the dermatomes above and below, typically without crossing the midline.8 The most frequent distributions in descending order are thoracic, cranial (mostly trigeminal), lumbar, and sacral. Pain in the dermatome may never occur, may precede, may occur during, or may even occur after the eruption. The initial presentation involves papules and plaques that develop blisters within hours of their development. Lesions continue to appear for several days and may coalesce. The lesions may become hemorrhagic, necrotic, or bullous, with or without adenopathy. Rarely, there can be pain without the associated skin eruption (zoster sine herpete). Lesions tend to crust by days 7 to 10.8

Herpes zoster typically affects children to a lesser extent than adults. The disease state often is milder in children with a decreased likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia.10 However, there are documented cases of severe sequelae secondary to zoster infection in pediatric patients, including but not limited to disseminated HZ,8 HZ ophthalmicus,11,12 Ramsay Hunt syndrome,8 and chronic encephalitis.8 In the adult population, ocular involvement will present in 33% to 50% of cases that involve the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve without clinical involvement of the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic nerve. Involvement of the nasociliary branch will lead to ocular pathology in an estimated 76% to 100% of adult cases.13,14 It is unknown if this rate is the same in the pediatric population, but it highlights the importance of educating patients and/or guardians about possible complications. It also demonstrates the importance of including HZ in the differential diagnosis for pediatric patients presenting with papular or vesicular skin eruptions, particularly in the area of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

Diagnosis

Herpes zoster usually is diagnosed based on its clinical presentation. Human herpesvirus 1 or 2 also may present with similar lesions and should be included in the differential diagnosis. To confirm a clinical diagnosis, additional testing may be done. A Tzanck smear historically has been the least expensive and most rapid test. Scrapings can be taken from the base of a vesicle, stained, and examined for multinucleated giant cells; however, a Tzanck smear cannot help in distinguishing herpes simplex virus from VZV. Direct fluorescent antibody testing and viral culture are less rapid but are standard tests that may help with the diagnosis. Direct fluorescent antibody testing can have a high false-negative rate, and viral cultures typically take 2 weeks for completion. These tests have largely been replaced by PCR analysis. Polymerase chain reaction has been the most sensitive test developed yet. With recent advances, real-time PCR, which can be performed within 1 hour in small hospital laboratories,15 has become more readily available and much more rapid than standard PCR. Further PCR testing can differentiate between the 2 possible infective strains (wild-type vs vaccine related).16 Real-time PCR is now commonly used as the first-line ancillary diagnostic test after physical examination.17

Conclusion

Although uncommon, HZ does occur in immunocompetent children and should be included in the differential diagnosis in children with vesicular lesions. Herpes zoster is a reactivation of VZV and initial exposure may be from the wild-type or vaccine-related strains. Clinicians must be vigilant in their evaluation of vesicular lesions in children even without known varicella exposure. Polymerase chain reaction testing can be helpful to distinguish between herpes simplex lesions and VZV. Polymerase chain reaction testing also may be of benefit to determine the strain of VZV infection.

- Myers MG, Seward JF, LaRussa PS. Varicella-zoster virus. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:1104-1105.

- Terada K, Kawano S, Yoshihiro K, et al. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) reactivation is related to the low response of VZV-specific immunity after chickenpox in infancy. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:650-652.

- Takayama N, Yamada H, Kaku H, et al. Herpes zoster in immunocompetent and immunocompromised Japanese children. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:275-279.

- Weinmann S, Chun C, Schmid DS, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children in the varicella vaccine era, 2005-2009. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1859-1868.

- Civen R, Lopez AS, Zhang J, et al. Varicella outbreak epidemiology in an active surveillance site, 1995–2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S114-S119.

- Russell ML, Dover DC, Simmonds KA, et al. Shingles in Alberta: before and after publicly funded varicella vaccination. Vaccine. 2014;32:6319-6324.

- Goldman GS, King PG. Review of the United States universal varicella vaccination program: herpes zoster incidence rates, cost-effectiveness, and vaccine efficacy based primarily on the Antelope Valley Varicella Active Surveillance Project data. Vaccine. 2013;31:1680-1694.

- Arikawa J, Asahi T, Au WY, et al. Zoster (shingles, herpes zoster). In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:372-376.

- Guris D, Jumaan AO, Mascola L, et al. Changing varicella epidemiology in active surveillance sites–United States, 1995-2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S71-S75.

- Petursson G, Helgason S, Gudmundsson S, et al. Herpes zoster in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:905-908.

- Oladokun RE, Olomukoro CN, Owa AB. Disseminated herpes zoster ophthalmicus in an immunocompetent 8-year-old boy. Clin Pract. 2013;3:e16.

- Lewkonia IK, Jackson AA. Infantile herpes zoster after intrauterine exposure to varicella. Br Med J. 1973;3:149.

- Zaal MJ, Völker-Dieben HJ, D’Amaro J. Prognostic value of Hutchinson’s sign in acute herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:187-191.

- Harding SP, Lipton JR, Wells JC. Natural history of herpes zoster ophthalmicus: predictors of postherpetic neuralgia and ocular involvement. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:353-358.

- Higashimoto Y, Ihira M, Ohta A, et al. Discriminating between varicella-zoster virus vaccine and wild-type strains by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2665-2670.

- Harbecke R, Oxman MN, Arnold, et al. A real-time PCR assay to identify and discriminate among wild-type and vaccine strains of varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in clinical specimens, and comparison with the clinical diagnoses. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1310-1322.

- Albrecht MA. Diagnosis of varicella-zoster infection. UpToDate website. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-of-varicella-zoster-virus-infection. Updated July 6, 2015. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- Myers MG, Seward JF, LaRussa PS. Varicella-zoster virus. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:1104-1105.

- Terada K, Kawano S, Yoshihiro K, et al. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) reactivation is related to the low response of VZV-specific immunity after chickenpox in infancy. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:650-652.

- Takayama N, Yamada H, Kaku H, et al. Herpes zoster in immunocompetent and immunocompromised Japanese children. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:275-279.

- Weinmann S, Chun C, Schmid DS, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children in the varicella vaccine era, 2005-2009. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1859-1868.

- Civen R, Lopez AS, Zhang J, et al. Varicella outbreak epidemiology in an active surveillance site, 1995–2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S114-S119.

- Russell ML, Dover DC, Simmonds KA, et al. Shingles in Alberta: before and after publicly funded varicella vaccination. Vaccine. 2014;32:6319-6324.

- Goldman GS, King PG. Review of the United States universal varicella vaccination program: herpes zoster incidence rates, cost-effectiveness, and vaccine efficacy based primarily on the Antelope Valley Varicella Active Surveillance Project data. Vaccine. 2013;31:1680-1694.

- Arikawa J, Asahi T, Au WY, et al. Zoster (shingles, herpes zoster). In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:372-376.

- Guris D, Jumaan AO, Mascola L, et al. Changing varicella epidemiology in active surveillance sites–United States, 1995-2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S71-S75.

- Petursson G, Helgason S, Gudmundsson S, et al. Herpes zoster in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:905-908.

- Oladokun RE, Olomukoro CN, Owa AB. Disseminated herpes zoster ophthalmicus in an immunocompetent 8-year-old boy. Clin Pract. 2013;3:e16.

- Lewkonia IK, Jackson AA. Infantile herpes zoster after intrauterine exposure to varicella. Br Med J. 1973;3:149.

- Zaal MJ, Völker-Dieben HJ, D’Amaro J. Prognostic value of Hutchinson’s sign in acute herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:187-191.

- Harding SP, Lipton JR, Wells JC. Natural history of herpes zoster ophthalmicus: predictors of postherpetic neuralgia and ocular involvement. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:353-358.

- Higashimoto Y, Ihira M, Ohta A, et al. Discriminating between varicella-zoster virus vaccine and wild-type strains by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2665-2670.

- Harbecke R, Oxman MN, Arnold, et al. A real-time PCR assay to identify and discriminate among wild-type and vaccine strains of varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in clinical specimens, and comparison with the clinical diagnoses. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1310-1322.

- Albrecht MA. Diagnosis of varicella-zoster infection. UpToDate website. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-of-varicella-zoster-virus-infection. Updated July 6, 2015. Accessed July 19, 2016.

Practice Points

- Herpes zoster (HZ) should be included in the differential diagnosis for children presenting with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal distribution and a history of varicella exposure.

- Clinical diagnosis of HZ and herpes simplex virus can be aided by the use of viral polymerase chain reaction testing.

- Children with HZ should be monitored for the same possible complications as adults.

SAGE-547 for depression: Cause for caution and optimism

The importance of postpartum depression, both in terms of its prevalence and the need for appropriate screening and effective treatments, has become an increasingly important area of focus for clinicians, patients, and policymakers. This derives from more than a decade of data on the significant prevalence of the condition, with roughly 10% of women meeting the criteria for major or minor depression during the first 3-6 months post partum.

Over the last 5 years, interest has centered around establishing mechanisms for appropriate perinatal depression screening, most notably the January 2016 recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that all adults should be screened for depression, including the at-risk populations of pregnant and postpartum women. In 2015, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorsed screening women for depression and anxiety symptoms at least once during the perinatal period using a validated tool. Unfortunately, we still lack data to support whether screening is effective in getting patients referred for treatment and if it leads to women accessing therapies that will actually get them well.

As we wait for that data and consider ways to best implement enhanced screening, it’s important to take stock of the available treatments for postpartum depression.

Seeking a rapid treatment

The current literature supports efficacy for nonpharmacologic therapies, such as interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, as well as several antidepressants. The efficacy of antidepressants – such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors – has been demonstrated for postpartum depression, but these agents carry the typical limitations and concerns in terms of side effects and the amount of time required to ascertain if there is benefit. While these are the same challenges seen in treating depression in general, the time to response – often 4-8 weeks – is particularly problematic for postpartum women where the impact of depression on maternal morbidity and child development is so critical.

The field has been clamoring for agents that work more quickly. One possibility in that area is ketamine, which is being studied as a rapid treatment in major depression. The National Institutes of Health also has an initiative underway called RAPID (Rapidly Acting Treatments for Treatment-Resistant Depression), aimed at identifying and testing pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments that produce a response within days rather than weeks.

Recently, considerable interest has focused on SAGE-547, manufactured by Sage Therapeutics, which is a different type of antidepressant. The so-called neurosteriod is an allosteric modulator of the GABAA (gamma-aminobutyric acid type A) receptors. The product was granted fast-track status by the Food and Drug Administration to speed its development as a possible treatment for superrefractory status epilepticus, but it also is being studied for its potential in treating severe postpartum depression.

Approximately a year ago, there was preliminary evidence from an open-label study suggesting rapid response to SAGE-547 for women who received this medicine intravenously in a controlled hospital environment. And in July 2016, the manufacturer announced in a press release unpublished positive results from a small phase II controlled trial of SAGE-547 for the treatment of severe postpartum depression.

Specifically, this was a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial for 21 women who had severe depressive symptoms with a baseline score of at least 26 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D). For some of the women, postpartum depression was not of new onset, but rather was an extension of depression that had manifested no earlier than the third trimester of pregnancy. A total of 10 women received the drug, while 11 received placebo. Both groups received continuous intravenous infusion over a 60-hour period.

Consistent with the earlier report, participants receiving the active agent had a statistically significant reduction in HAM-D scores at 24 hours, compared with women who received the placebo. Seven out of 10 women who received the active drug achieved remission from depression at 60 hours, compared with only 1 of the 11 patients who received placebo. Even though the results derived from an extremely small sample, the signal for efficacy appears promising.

Of particular interest, there appeared to be a duration of benefit at 30 days’ follow-up. The medicine was well tolerated with no discontinuations due to adverse events, which were most commonly dizziness, sedation, or somnolence. The adverse events were about the same in both the drug and placebo groups.

Next steps

These early results have generated excitement, if not a “buzz,” in the field, given the rapid onset of antidepressant benefit and the apparent duration of the effect. But readers should be mindful that to date, the findings have not been peer reviewed and are available only through a company-issued press release. It is also noteworthy that on clinicaltrials.gov, the projected enrollment was 32, but 21 women enrolled. This may speak to the great difficulty in enrolling the sample and may ultimately reflect on the generalizability of the findings.

One significant challenge with SAGE-547 is the formulation. It’s hardly feasible for severely ill postpartum women to come to the hospital for 60 hours of treatment. The manufacturer will have to produce a reformulated compound that is able to sustain the efficacy signaled in this proof of concept study.

But even more importantly, we will need to see how the drug performs in a larger, rigorous phase IIB or phase III study to know if the signal of promise really translates into a potential viable treatment option for women with severe postpartum depression. When we have results from a randomized controlled trial with a substantially larger number of patients, then we’ll know whether the excitement is justified. It would be a significant advance for the field if this were to be the case.

The field of depression, in general, has been seeking an effective, rapid treatment for some time, and the role of neurosteriods has been spoken about for more than 2 decades. If postpartum women are in fact a subgroup who respond to this class of agents, then that would be an example of truly personalized medicine. But we won’t know that until the manufacturer does an appropriate large trial, which could take 2-4 years.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information and resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has no financial relationship with SAGE Therapeutics, but he has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.