User login

HPV vaccine and adolescents: What we say really does matter

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

Vaccine coverage

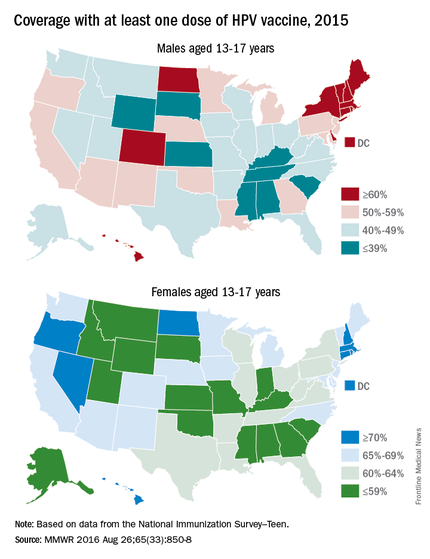

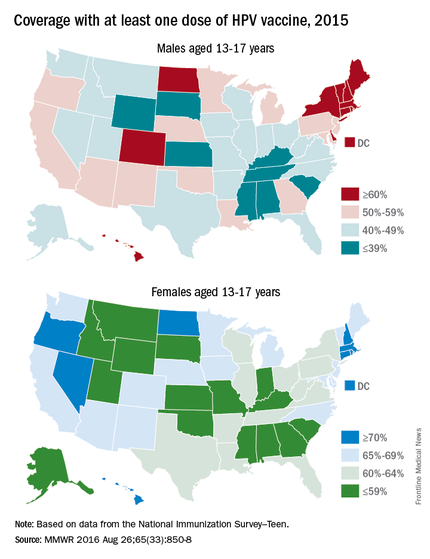

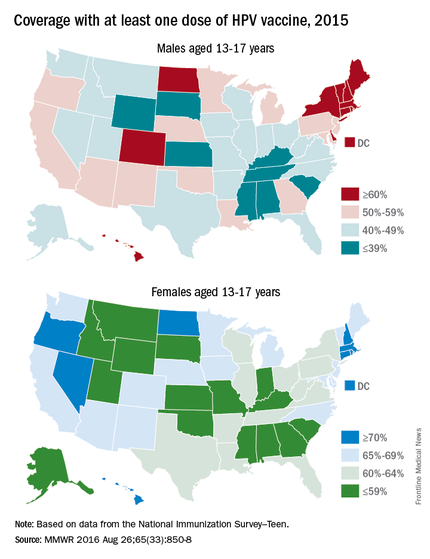

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

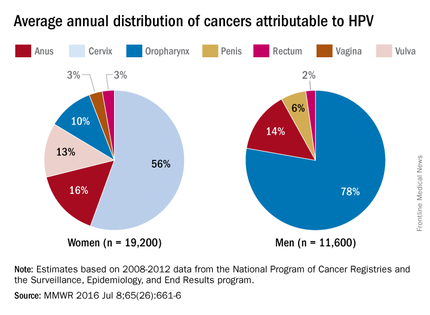

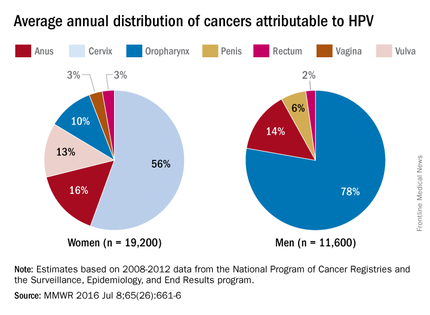

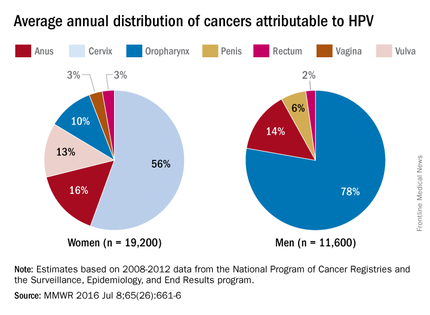

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.

One consistent reason parents indicate for not vaccinating is the lack of recommendation from their child’s health provider. Differences in age and sex recommendations also are reported. NIS-Teen 2013 demonstrated that parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to receive a provider recommendation (65% vs.42%.) Only 29% of female parents indicated they’d received a provider recommendation to have their child vaccinated with HPV by ages 11-12 years.

Mandy A. Allison, MD, and her colleagues reviewed primary care physician perspectives about HPV vaccine in a national survey among 364 pediatricians and 218 family physicians (FPs). Although 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FPs indicated they always discuss HPV vaccination, only 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FPs strongly recommend HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls; for boys it was 52% and 41%. More than half reported parental deferral. For pediatricians who almost never discussed the topic, the reasons included that the patient was not sexually active (54%), the child was young (38%), and the patient was already receiving other vaccines (35%) (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137[2]:e20152488).

Providers can be influenced by their perceptions of what value parents place on vaccines. In one study, parents were asked to put a value on specific vaccines. Providers were then asked to estimate how parents ranked the vaccines on a scale of 0-10. Providers underestimated the value placed on HPV vaccine (9.3 vs 5.2) (Vaccine 2014;32:579-84).

Improving HPV coverage: Preventing future HPV-related cancers

HPV vaccine should be recommended with as much conviction as Tdap and MCV at the 11- to 12-year visit for both girls and boys. Administration of all three should occur on the same day. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents decide to vaccinate. The mantra “same way, same day” should become synonymous with the 11- to 12-year visit. All who have contact with the patient, beginning with the front desk staff, should know the importance of HPV vaccine, and when and why it is recommended. Often, families spend more time with support staff and have discussions prior to interacting with you.

Anticipate questions about HPV. Why give the vaccine when the child is so young and not sexually active? Is my child really at risk? Is it safe? I read on the Internet. … Questions should be interpreted as a need for additional information and reassurance from you.

Remember to emphasize that HPV vaccine is important because it prevents cancer and it is most effective prior to exposure to HPV.

Additional resources to facilitate your discussions about HPV can be found at www.cdc.gov/hpv.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

Vaccine coverage

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.

One consistent reason parents indicate for not vaccinating is the lack of recommendation from their child’s health provider. Differences in age and sex recommendations also are reported. NIS-Teen 2013 demonstrated that parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to receive a provider recommendation (65% vs.42%.) Only 29% of female parents indicated they’d received a provider recommendation to have their child vaccinated with HPV by ages 11-12 years.

Mandy A. Allison, MD, and her colleagues reviewed primary care physician perspectives about HPV vaccine in a national survey among 364 pediatricians and 218 family physicians (FPs). Although 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FPs indicated they always discuss HPV vaccination, only 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FPs strongly recommend HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls; for boys it was 52% and 41%. More than half reported parental deferral. For pediatricians who almost never discussed the topic, the reasons included that the patient was not sexually active (54%), the child was young (38%), and the patient was already receiving other vaccines (35%) (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137[2]:e20152488).

Providers can be influenced by their perceptions of what value parents place on vaccines. In one study, parents were asked to put a value on specific vaccines. Providers were then asked to estimate how parents ranked the vaccines on a scale of 0-10. Providers underestimated the value placed on HPV vaccine (9.3 vs 5.2) (Vaccine 2014;32:579-84).

Improving HPV coverage: Preventing future HPV-related cancers

HPV vaccine should be recommended with as much conviction as Tdap and MCV at the 11- to 12-year visit for both girls and boys. Administration of all three should occur on the same day. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents decide to vaccinate. The mantra “same way, same day” should become synonymous with the 11- to 12-year visit. All who have contact with the patient, beginning with the front desk staff, should know the importance of HPV vaccine, and when and why it is recommended. Often, families spend more time with support staff and have discussions prior to interacting with you.

Anticipate questions about HPV. Why give the vaccine when the child is so young and not sexually active? Is my child really at risk? Is it safe? I read on the Internet. … Questions should be interpreted as a need for additional information and reassurance from you.

Remember to emphasize that HPV vaccine is important because it prevents cancer and it is most effective prior to exposure to HPV.

Additional resources to facilitate your discussions about HPV can be found at www.cdc.gov/hpv.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

Vaccine coverage

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.

One consistent reason parents indicate for not vaccinating is the lack of recommendation from their child’s health provider. Differences in age and sex recommendations also are reported. NIS-Teen 2013 demonstrated that parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to receive a provider recommendation (65% vs.42%.) Only 29% of female parents indicated they’d received a provider recommendation to have their child vaccinated with HPV by ages 11-12 years.

Mandy A. Allison, MD, and her colleagues reviewed primary care physician perspectives about HPV vaccine in a national survey among 364 pediatricians and 218 family physicians (FPs). Although 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FPs indicated they always discuss HPV vaccination, only 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FPs strongly recommend HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls; for boys it was 52% and 41%. More than half reported parental deferral. For pediatricians who almost never discussed the topic, the reasons included that the patient was not sexually active (54%), the child was young (38%), and the patient was already receiving other vaccines (35%) (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137[2]:e20152488).

Providers can be influenced by their perceptions of what value parents place on vaccines. In one study, parents were asked to put a value on specific vaccines. Providers were then asked to estimate how parents ranked the vaccines on a scale of 0-10. Providers underestimated the value placed on HPV vaccine (9.3 vs 5.2) (Vaccine 2014;32:579-84).

Improving HPV coverage: Preventing future HPV-related cancers

HPV vaccine should be recommended with as much conviction as Tdap and MCV at the 11- to 12-year visit for both girls and boys. Administration of all three should occur on the same day. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents decide to vaccinate. The mantra “same way, same day” should become synonymous with the 11- to 12-year visit. All who have contact with the patient, beginning with the front desk staff, should know the importance of HPV vaccine, and when and why it is recommended. Often, families spend more time with support staff and have discussions prior to interacting with you.

Anticipate questions about HPV. Why give the vaccine when the child is so young and not sexually active? Is my child really at risk? Is it safe? I read on the Internet. … Questions should be interpreted as a need for additional information and reassurance from you.

Remember to emphasize that HPV vaccine is important because it prevents cancer and it is most effective prior to exposure to HPV.

Additional resources to facilitate your discussions about HPV can be found at www.cdc.gov/hpv.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

CSF2RB mutation, common in Ashkenazim, linked to Crohn’s

A frameshift mutation in the CSF2RB gene that is common in Ashkenazi Jews has been linked to Crohn’s disease, according to a report in Gastroenterology.

The Ashkenazi Jewish population has a four- to sevenfold higher prevalence of Crohn’s disease than does the general population. To identify possible genetic mutations associated with the disease, researchers performed exome sequencing of samples from 1,477 Ashkenazi Jewish patients with Crohn’s disease and 2,614 Ashkenazi Jewish control subjects who didn’t have the disorder. All the study participants were enrolled at medical centers throughout North America, Europe, and Israel, noted Ling-Shiang Chuang, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in genetics and genomic sciences, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, and his associates.

They genotyped 224 frameshift mutations and identified one in the colony-stimulating factor 2–receptor beta common subunit (CSF2RB) gene that was significantly associated with Crohn’s disease. They validated this association in a replication cohort of 1,515 Ashkenazi Jewish patients with Crohn’s disease and 7,052 health Ashkenazi control subjects, observing nearly identical allele frequencies and odds ratios as in the discovery cohort.

Since the CSF2RB gene encodes for the receptor for GM-CSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) cytokines, the mutation would be expected to reduce GM-CSF signaling in monocytes obtained from carriers. The investigators found this was true when they examined monocytes taken from intestinal-tissue samples and peripheral-blood samples from affected patients.

“The present findings of a loss-of-function frameshift variant in the CSF2RB gene argue for a primary pathogenic role of decreased GM-CSF signaling in driving a subset of Crohn’s disease cases. As many as 30% of cases have increased levels of anti-GM-CSF antibodies, which can neutralize GM-CSF activity, indicating that impaired GM-CSF signaling plays a major role in Crohn’s disease,” Dr. Chuang and his associates wrote (Gastroenterol. 2016;151:710-23.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.045).

Future research may identify subgroups of Crohn’s patients in which treatments that target GM-CSF signaling may be effective, and it may also point the way to novel therapies for the broader population of patients with Crohn’s disease, they added.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium, the Genetic Research Center at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York’s Crohn’s Foundation, and several others. Dr. Chuang and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified over 200 DNA mutations (mainly single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) contributing to inflammatory bowel disease. However, their causality in IBD remains unknown. In the post-GWAS era, functional characterization and mechanistic elucidation of these SNPs is a major challenge. SNPs impacting the protein-coding genes can drastically alter protein function and play an important role in molecular pathogenesis. However, most SNPs are in noncoding genes and their impact on gene regulation and disease outcome remains largely unknown. This study reveals a frameshift mutation in the CSF2RB gene associated with Crohn’s disease in an Ashkenazi Jewish population. A frameshift mutation results in the deletion or insertion in a DNA sequence that shifts the way the sequence is transcribed into RNA. The most well described frameshift mutation in Crohn’s disease with clinical relevance is in the NOD2 gene, which results in impaired immune response to microbial stimuli. Because GWASs show association not causality, the biological consequence of the CSF2RB frameshift mutation in intestinal macrophages leads to a decrease in its response to granulocyte-monocyte stimulating factor (GM-CSF) providing a potential mechanistic role for the mutation in Crohn’s disease pathogenesis in a disease-relevant cell and site. This study will pave the way for future important studies that reveal the impact of SNPs on Crohn’s disease development, prognosis, and eventually response to therapy.

Shehzad Z. Sheikh MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine, department of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified over 200 DNA mutations (mainly single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) contributing to inflammatory bowel disease. However, their causality in IBD remains unknown. In the post-GWAS era, functional characterization and mechanistic elucidation of these SNPs is a major challenge. SNPs impacting the protein-coding genes can drastically alter protein function and play an important role in molecular pathogenesis. However, most SNPs are in noncoding genes and their impact on gene regulation and disease outcome remains largely unknown. This study reveals a frameshift mutation in the CSF2RB gene associated with Crohn’s disease in an Ashkenazi Jewish population. A frameshift mutation results in the deletion or insertion in a DNA sequence that shifts the way the sequence is transcribed into RNA. The most well described frameshift mutation in Crohn’s disease with clinical relevance is in the NOD2 gene, which results in impaired immune response to microbial stimuli. Because GWASs show association not causality, the biological consequence of the CSF2RB frameshift mutation in intestinal macrophages leads to a decrease in its response to granulocyte-monocyte stimulating factor (GM-CSF) providing a potential mechanistic role for the mutation in Crohn’s disease pathogenesis in a disease-relevant cell and site. This study will pave the way for future important studies that reveal the impact of SNPs on Crohn’s disease development, prognosis, and eventually response to therapy.

Shehzad Z. Sheikh MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine, department of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified over 200 DNA mutations (mainly single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) contributing to inflammatory bowel disease. However, their causality in IBD remains unknown. In the post-GWAS era, functional characterization and mechanistic elucidation of these SNPs is a major challenge. SNPs impacting the protein-coding genes can drastically alter protein function and play an important role in molecular pathogenesis. However, most SNPs are in noncoding genes and their impact on gene regulation and disease outcome remains largely unknown. This study reveals a frameshift mutation in the CSF2RB gene associated with Crohn’s disease in an Ashkenazi Jewish population. A frameshift mutation results in the deletion or insertion in a DNA sequence that shifts the way the sequence is transcribed into RNA. The most well described frameshift mutation in Crohn’s disease with clinical relevance is in the NOD2 gene, which results in impaired immune response to microbial stimuli. Because GWASs show association not causality, the biological consequence of the CSF2RB frameshift mutation in intestinal macrophages leads to a decrease in its response to granulocyte-monocyte stimulating factor (GM-CSF) providing a potential mechanistic role for the mutation in Crohn’s disease pathogenesis in a disease-relevant cell and site. This study will pave the way for future important studies that reveal the impact of SNPs on Crohn’s disease development, prognosis, and eventually response to therapy.

Shehzad Z. Sheikh MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine, department of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

A frameshift mutation in the CSF2RB gene that is common in Ashkenazi Jews has been linked to Crohn’s disease, according to a report in Gastroenterology.

The Ashkenazi Jewish population has a four- to sevenfold higher prevalence of Crohn’s disease than does the general population. To identify possible genetic mutations associated with the disease, researchers performed exome sequencing of samples from 1,477 Ashkenazi Jewish patients with Crohn’s disease and 2,614 Ashkenazi Jewish control subjects who didn’t have the disorder. All the study participants were enrolled at medical centers throughout North America, Europe, and Israel, noted Ling-Shiang Chuang, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in genetics and genomic sciences, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, and his associates.

They genotyped 224 frameshift mutations and identified one in the colony-stimulating factor 2–receptor beta common subunit (CSF2RB) gene that was significantly associated with Crohn’s disease. They validated this association in a replication cohort of 1,515 Ashkenazi Jewish patients with Crohn’s disease and 7,052 health Ashkenazi control subjects, observing nearly identical allele frequencies and odds ratios as in the discovery cohort.

Since the CSF2RB gene encodes for the receptor for GM-CSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) cytokines, the mutation would be expected to reduce GM-CSF signaling in monocytes obtained from carriers. The investigators found this was true when they examined monocytes taken from intestinal-tissue samples and peripheral-blood samples from affected patients.

“The present findings of a loss-of-function frameshift variant in the CSF2RB gene argue for a primary pathogenic role of decreased GM-CSF signaling in driving a subset of Crohn’s disease cases. As many as 30% of cases have increased levels of anti-GM-CSF antibodies, which can neutralize GM-CSF activity, indicating that impaired GM-CSF signaling plays a major role in Crohn’s disease,” Dr. Chuang and his associates wrote (Gastroenterol. 2016;151:710-23.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.045).

Future research may identify subgroups of Crohn’s patients in which treatments that target GM-CSF signaling may be effective, and it may also point the way to novel therapies for the broader population of patients with Crohn’s disease, they added.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium, the Genetic Research Center at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York’s Crohn’s Foundation, and several others. Dr. Chuang and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A frameshift mutation in the CSF2RB gene that is common in Ashkenazi Jews has been linked to Crohn’s disease, according to a report in Gastroenterology.

The Ashkenazi Jewish population has a four- to sevenfold higher prevalence of Crohn’s disease than does the general population. To identify possible genetic mutations associated with the disease, researchers performed exome sequencing of samples from 1,477 Ashkenazi Jewish patients with Crohn’s disease and 2,614 Ashkenazi Jewish control subjects who didn’t have the disorder. All the study participants were enrolled at medical centers throughout North America, Europe, and Israel, noted Ling-Shiang Chuang, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in genetics and genomic sciences, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, and his associates.

They genotyped 224 frameshift mutations and identified one in the colony-stimulating factor 2–receptor beta common subunit (CSF2RB) gene that was significantly associated with Crohn’s disease. They validated this association in a replication cohort of 1,515 Ashkenazi Jewish patients with Crohn’s disease and 7,052 health Ashkenazi control subjects, observing nearly identical allele frequencies and odds ratios as in the discovery cohort.

Since the CSF2RB gene encodes for the receptor for GM-CSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) cytokines, the mutation would be expected to reduce GM-CSF signaling in monocytes obtained from carriers. The investigators found this was true when they examined monocytes taken from intestinal-tissue samples and peripheral-blood samples from affected patients.

“The present findings of a loss-of-function frameshift variant in the CSF2RB gene argue for a primary pathogenic role of decreased GM-CSF signaling in driving a subset of Crohn’s disease cases. As many as 30% of cases have increased levels of anti-GM-CSF antibodies, which can neutralize GM-CSF activity, indicating that impaired GM-CSF signaling plays a major role in Crohn’s disease,” Dr. Chuang and his associates wrote (Gastroenterol. 2016;151:710-23.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.045).

Future research may identify subgroups of Crohn’s patients in which treatments that target GM-CSF signaling may be effective, and it may also point the way to novel therapies for the broader population of patients with Crohn’s disease, they added.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium, the Genetic Research Center at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York’s Crohn’s Foundation, and several others. Dr. Chuang and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: A frameshift mutation in the CSF2RB gene that is common in Ashkenazi Jews has been linked to Crohn’s disease.

Major finding: Genotyping of 224 frameshift mutations identified one in the colony-stimulating factor 2–receptor common subunit (CSF2RB) gene that was significantly associated with Crohn’s disease.

Data source: Exome sequencing and genotype analyses of samples from 1,477 Ashkenazi Jewish people with Crohn’s disease and 2,614 without it.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium, the Genetic Research Center at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York’s Crohn’s Foundation, and several others. Dr. Chuang and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Dexamethasone-associated posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

Simple interventions markedly improve hepatitis care

Several simple, inexpensive operational interventions substantially improve care for viral hepatitis, according to a report published in the Lancet.

Recent advances in treatment for chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C have the potential to halt or even reverse the progression of associated liver disease and to reduce related mortality, reported Kali Zhou, MD, of the division of gastroenterology, University of California, San Francisco, and her associates. But they can do so only if affected individuals are engaged and retained in the relatively long continuum of care, from diagnosis through viral suppression or cure.

To assess the usefulness of interventions that promote such patient engagement and retention, Dr. Zhou and her colleagues reviewed the scientific literature and performed a meta-analysis of 56 studies. They examined 15 studies on HBV care, 38 on HCV care, and 3 on both types of hepatitis (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 5. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30208-0).

Among their findings:

• Educating a single lay health worker to improve knowledge about the disease in his or her community and to promote diagnostic testing nearly tripled the testing rate (relative risk, 2.68), compared with no such intervention.

• Clinician reminders during regular office visits to consider hepatitis testing – such as prompts in the patients’ electronic medical records or stickers on their charts – nearly quadrupled the testing rate (RR, 3.70), compared with no clinician reminders.

• Providing guided referral to a hepatitis specialist for people at risk for the disorder markedly improved the rate of visits to such specialists (RR, 1.57), compared with no such referrals.

• Providing psychological counseling and motivational therapy for mental health and/or substance misuse problems along with medical care for hepatitis dramatically increased the number of patients treated (OR, 3.42) and raised the rate of treatment completion (RR, 1.14).

• Combining mental health, substance misuse, and hepatitis treatment services at one location increased the rate of treatment initiation (RR, 1.36), treatment adherence (RR, 1.22), and cure as measured by sustained virologic response rate (RR, 1.21), compared with usual care.

These interventions might be useful in augmenting hepatitis treatment programs worldwide, Dr. Zhou and her associates said.

The World Health Organization and the U.S. Fulbright Program supported the study. Dr. Zhou and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

This meta-analysis identified proven strategies that can be adopted widely and can become standard components of a package of health care services for viral hepatitis.

But it also revealed the need for additional high-quality data to guide the development of even more such strategies. Reducing the burden of hepatitis depends on helping patients navigate through diagnosis; referral to specialist care; completion of complex, long-term treatment; and linkages to related clinical services such as mental health or substance misuse counseling.

John W. Ward, MD, is director of the division of viral hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Ward made these remarks in a comment accompanying Dr. Zhou’s report (Lancet. 2016 Sep 5; doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30272-9).

This meta-analysis identified proven strategies that can be adopted widely and can become standard components of a package of health care services for viral hepatitis.

But it also revealed the need for additional high-quality data to guide the development of even more such strategies. Reducing the burden of hepatitis depends on helping patients navigate through diagnosis; referral to specialist care; completion of complex, long-term treatment; and linkages to related clinical services such as mental health or substance misuse counseling.

John W. Ward, MD, is director of the division of viral hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Ward made these remarks in a comment accompanying Dr. Zhou’s report (Lancet. 2016 Sep 5; doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30272-9).

This meta-analysis identified proven strategies that can be adopted widely and can become standard components of a package of health care services for viral hepatitis.

But it also revealed the need for additional high-quality data to guide the development of even more such strategies. Reducing the burden of hepatitis depends on helping patients navigate through diagnosis; referral to specialist care; completion of complex, long-term treatment; and linkages to related clinical services such as mental health or substance misuse counseling.

John W. Ward, MD, is director of the division of viral hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Ward made these remarks in a comment accompanying Dr. Zhou’s report (Lancet. 2016 Sep 5; doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30272-9).

Several simple, inexpensive operational interventions substantially improve care for viral hepatitis, according to a report published in the Lancet.

Recent advances in treatment for chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C have the potential to halt or even reverse the progression of associated liver disease and to reduce related mortality, reported Kali Zhou, MD, of the division of gastroenterology, University of California, San Francisco, and her associates. But they can do so only if affected individuals are engaged and retained in the relatively long continuum of care, from diagnosis through viral suppression or cure.

To assess the usefulness of interventions that promote such patient engagement and retention, Dr. Zhou and her colleagues reviewed the scientific literature and performed a meta-analysis of 56 studies. They examined 15 studies on HBV care, 38 on HCV care, and 3 on both types of hepatitis (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 5. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30208-0).

Among their findings:

• Educating a single lay health worker to improve knowledge about the disease in his or her community and to promote diagnostic testing nearly tripled the testing rate (relative risk, 2.68), compared with no such intervention.

• Clinician reminders during regular office visits to consider hepatitis testing – such as prompts in the patients’ electronic medical records or stickers on their charts – nearly quadrupled the testing rate (RR, 3.70), compared with no clinician reminders.

• Providing guided referral to a hepatitis specialist for people at risk for the disorder markedly improved the rate of visits to such specialists (RR, 1.57), compared with no such referrals.

• Providing psychological counseling and motivational therapy for mental health and/or substance misuse problems along with medical care for hepatitis dramatically increased the number of patients treated (OR, 3.42) and raised the rate of treatment completion (RR, 1.14).

• Combining mental health, substance misuse, and hepatitis treatment services at one location increased the rate of treatment initiation (RR, 1.36), treatment adherence (RR, 1.22), and cure as measured by sustained virologic response rate (RR, 1.21), compared with usual care.

These interventions might be useful in augmenting hepatitis treatment programs worldwide, Dr. Zhou and her associates said.

The World Health Organization and the U.S. Fulbright Program supported the study. Dr. Zhou and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Several simple, inexpensive operational interventions substantially improve care for viral hepatitis, according to a report published in the Lancet.

Recent advances in treatment for chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C have the potential to halt or even reverse the progression of associated liver disease and to reduce related mortality, reported Kali Zhou, MD, of the division of gastroenterology, University of California, San Francisco, and her associates. But they can do so only if affected individuals are engaged and retained in the relatively long continuum of care, from diagnosis through viral suppression or cure.

To assess the usefulness of interventions that promote such patient engagement and retention, Dr. Zhou and her colleagues reviewed the scientific literature and performed a meta-analysis of 56 studies. They examined 15 studies on HBV care, 38 on HCV care, and 3 on both types of hepatitis (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 5. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30208-0).

Among their findings:

• Educating a single lay health worker to improve knowledge about the disease in his or her community and to promote diagnostic testing nearly tripled the testing rate (relative risk, 2.68), compared with no such intervention.

• Clinician reminders during regular office visits to consider hepatitis testing – such as prompts in the patients’ electronic medical records or stickers on their charts – nearly quadrupled the testing rate (RR, 3.70), compared with no clinician reminders.

• Providing guided referral to a hepatitis specialist for people at risk for the disorder markedly improved the rate of visits to such specialists (RR, 1.57), compared with no such referrals.

• Providing psychological counseling and motivational therapy for mental health and/or substance misuse problems along with medical care for hepatitis dramatically increased the number of patients treated (OR, 3.42) and raised the rate of treatment completion (RR, 1.14).

• Combining mental health, substance misuse, and hepatitis treatment services at one location increased the rate of treatment initiation (RR, 1.36), treatment adherence (RR, 1.22), and cure as measured by sustained virologic response rate (RR, 1.21), compared with usual care.

These interventions might be useful in augmenting hepatitis treatment programs worldwide, Dr. Zhou and her associates said.

The World Health Organization and the U.S. Fulbright Program supported the study. Dr. Zhou and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Several simple, inexpensive operational interventions substantially improve care for viral hepatitis.

Major finding: Clinician reminders during regular office visits to consider hepatitis testing – such as prompts in the patients’ electronic medical records or stickers on their charts – nearly quadrupled the testing rate (relative risk, 3.70).

Data source: A meta-analysis of 56 studies worldwide assessing interventions to improve HBV and HCV care.

Disclosures: The World Health Organization and the U.S. Fulbright Program supported the study. Dr. Zhou and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A positive attitude in prostate cancer challenges: finding hope and optimism

Background Prostate cancer affects not only men with the disease, but their partners and families as well. These affects can include changes to everyday lifestyle activities, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction, and sometimes, relationships.

Objective To find out how men with prostate cancer and their female partners found spiritual lift and hope during the prostate cancer trajectory.

Methods The very personal and human nature of the question suggested that a qualitative approach with narrative inquiry would be the most appropriate. Comments were obtained from 10 men and 10 women who were not in a relationship with each other and from 10 couples (N = 40) and then subjected to narrative and thematic analysis.

Results The participants’ activities and circumstances provided their lift – rising above the everyday mundane – and their hope – optimism for the future – and helped them cope. In addition, what emerged was interesting insights on the way in which the participants associated these concepts with having a positive attitude in their life. They provided some valuable information on what constitutes being positive that will be helpful to others in similar circumstances, and to health professionals.

Limitations The information from a relatively small number of participants needs to be interpreted carefully and cannot result in strong conclusions about the nature of the results.

Conclusions Being positive during a time of illness and when dealing with the consequences of the illness, is an important element in coping. However, an understanding of the practicalities of what it means to be positive needs to be thoroughly developed and understood.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Prostate cancer affects not only men with the disease, but their partners and families as well. These affects can include changes to everyday lifestyle activities, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction, and sometimes, relationships.

Objective To find out how men with prostate cancer and their female partners found spiritual lift and hope during the prostate cancer trajectory.

Methods The very personal and human nature of the question suggested that a qualitative approach with narrative inquiry would be the most appropriate. Comments were obtained from 10 men and 10 women who were not in a relationship with each other and from 10 couples (N = 40) and then subjected to narrative and thematic analysis.

Results The participants’ activities and circumstances provided their lift – rising above the everyday mundane – and their hope – optimism for the future – and helped them cope. In addition, what emerged was interesting insights on the way in which the participants associated these concepts with having a positive attitude in their life. They provided some valuable information on what constitutes being positive that will be helpful to others in similar circumstances, and to health professionals.

Limitations The information from a relatively small number of participants needs to be interpreted carefully and cannot result in strong conclusions about the nature of the results.

Conclusions Being positive during a time of illness and when dealing with the consequences of the illness, is an important element in coping. However, an understanding of the practicalities of what it means to be positive needs to be thoroughly developed and understood.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Prostate cancer affects not only men with the disease, but their partners and families as well. These affects can include changes to everyday lifestyle activities, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction, and sometimes, relationships.

Objective To find out how men with prostate cancer and their female partners found spiritual lift and hope during the prostate cancer trajectory.

Methods The very personal and human nature of the question suggested that a qualitative approach with narrative inquiry would be the most appropriate. Comments were obtained from 10 men and 10 women who were not in a relationship with each other and from 10 couples (N = 40) and then subjected to narrative and thematic analysis.

Results The participants’ activities and circumstances provided their lift – rising above the everyday mundane – and their hope – optimism for the future – and helped them cope. In addition, what emerged was interesting insights on the way in which the participants associated these concepts with having a positive attitude in their life. They provided some valuable information on what constitutes being positive that will be helpful to others in similar circumstances, and to health professionals.

Limitations The information from a relatively small number of participants needs to be interpreted carefully and cannot result in strong conclusions about the nature of the results.

Conclusions Being positive during a time of illness and when dealing with the consequences of the illness, is an important element in coping. However, an understanding of the practicalities of what it means to be positive needs to be thoroughly developed and understood.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Evaluation of a policy of lymph node retrieval for colon cancer specimens: a quality improvement opportunity

Dental oncology in patients treated with radiation for head and neck cancer

The dentition of head and neck cancer patients is of utmost importance when they receive radiation therapy, especially because patients are living longer after a course of head and neck radiation. Good communication among the oncology team members (the radiation and medical oncologists, the maxillofacial prosthodontist/dental oncologist, otolaryngologist, reconstructive surgeon, nursing support) and the patient is essential initially, and subsequently including the general dentist as well. The aim of this primer for all those caring for patients with head and neck cancer is to underscore the important role of the dental oncologist during all phases of radiation therapy, and to provide guidelines to minimize and prevent dental complications such as radiation-induced caries and ORN.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

The dentition of head and neck cancer patients is of utmost importance when they receive radiation therapy, especially because patients are living longer after a course of head and neck radiation. Good communication among the oncology team members (the radiation and medical oncologists, the maxillofacial prosthodontist/dental oncologist, otolaryngologist, reconstructive surgeon, nursing support) and the patient is essential initially, and subsequently including the general dentist as well. The aim of this primer for all those caring for patients with head and neck cancer is to underscore the important role of the dental oncologist during all phases of radiation therapy, and to provide guidelines to minimize and prevent dental complications such as radiation-induced caries and ORN.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

The dentition of head and neck cancer patients is of utmost importance when they receive radiation therapy, especially because patients are living longer after a course of head and neck radiation. Good communication among the oncology team members (the radiation and medical oncologists, the maxillofacial prosthodontist/dental oncologist, otolaryngologist, reconstructive surgeon, nursing support) and the patient is essential initially, and subsequently including the general dentist as well. The aim of this primer for all those caring for patients with head and neck cancer is to underscore the important role of the dental oncologist during all phases of radiation therapy, and to provide guidelines to minimize and prevent dental complications such as radiation-induced caries and ORN.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Delayed or on schedule, MACRA is on its way

As 2016 winds down, we are already gearing up for the 2019 implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, or MACRA. The bipartisan 2015 legislation will replace the current sustainable growth rate as well as streamline the existing quality reporting programs and redirect us from the current volume-based Medicare payments to value- and performance-based payments. On page 394 of this issue, two community- based colleagues, JCSO Editor Dr Linda Bosserman and Dr Robin Zon, a community oncologist and chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Task Force on Clinical Pathways, discuss the ins and outs of MACRA – what it is, what it replaces, how it will work, and what we need to be doing to prepare for its implementation in 2019.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

As 2016 winds down, we are already gearing up for the 2019 implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, or MACRA. The bipartisan 2015 legislation will replace the current sustainable growth rate as well as streamline the existing quality reporting programs and redirect us from the current volume-based Medicare payments to value- and performance-based payments. On page 394 of this issue, two community- based colleagues, JCSO Editor Dr Linda Bosserman and Dr Robin Zon, a community oncologist and chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Task Force on Clinical Pathways, discuss the ins and outs of MACRA – what it is, what it replaces, how it will work, and what we need to be doing to prepare for its implementation in 2019.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

As 2016 winds down, we are already gearing up for the 2019 implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, or MACRA. The bipartisan 2015 legislation will replace the current sustainable growth rate as well as streamline the existing quality reporting programs and redirect us from the current volume-based Medicare payments to value- and performance-based payments. On page 394 of this issue, two community- based colleagues, JCSO Editor Dr Linda Bosserman and Dr Robin Zon, a community oncologist and chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Task Force on Clinical Pathways, discuss the ins and outs of MACRA – what it is, what it replaces, how it will work, and what we need to be doing to prepare for its implementation in 2019.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

What Distinguishes MS From Its Mimics?

HILTON HEAD—Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common demyelinating disease, and its mimics are rare, according to an overview provided at the 39th Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium. Given that the treatments and outcomes for MS and its mimics are so different, neurologists should take care to establish a diagnosis early, said Sid Pawate, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville.

Because of the varied clinical presentation of MS, a wide variety of conditions enter the differential diagnosis. Because of the central role that MRI plays in MS diagnosis, imaging mimics that cause white matter lesions also need to be considered, said Dr. Pawate. Typically, the white matter lesions seen in MS are periventricular, juxtacortical, and callososeptal in location. Infratentorially, cerebellar peduncles are a common site. The lesions tend to be ovoid, are 3 mm to 5 mm or larger, and appear hyperintense on T2 and FLAIR sequences. Acute lesions may show restricted diffusion or enhancement after the administration of gadolinium contrast.

Typical Presentations of MS

The three most common presentations of MS are transverse myelitis, optic neuritis, and brainstem–cerebellar dysfunction. Acute partial transverse myelitis is “the most classic” form of transverse myelitis among patients with MS, said Dr. Pawate. Acute complete transverse myelitis, on the other hand, may be postinfectious or idiopathic, or seen as part of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Similarly, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis is more suggestive of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) than MS.

The most typical presentation of MS optic neuritis is unilateral and has acute or subacute onset. Patients often have retrobulbar, “gritty” pain when they move their eye. Complete blindness is unusual, and complete recovery occurs in nearly all patients. Hyperacute onset suggests a vascular process rather than optic neuritis, said Dr. Pawate. Slow, insidious onset may indicate an infiltrative process such as neoplasm or sarcoidosis. Painless vision loss may indicate ischemic optic neuropathy, and severe blindness without recovery may result from NMOSD.

The most pathognomonic brainstem dysfunction in MS is intranuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO), especially when it is bilateral. Other brainstem symptoms typical of MS include ataxia, painless diplopia, facial numbness, and trigeminal neuralgia in a young patient. Hyperacute or insidious onset of brainstem symptoms is unlikely to indicate MS. Symptoms that localize to a vascular territory usually result from a stroke. In addition, multiple cranial neuropathy is more suggestive of infections such as Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, or carcinomic ulcers.

Unusual Presentations of MS

Certain variants of MS do not present with the typical periventricular ovoid lesions. Tumefactive MS often presents with a large (ie, larger than 2 cm), solitary demyelinating lesion. These lesions usually are biopsied. Treatment with steroids usually brings improvement. After this first manifestation, the patient’s course is typical of relapsing-remitting MS. “Rarely do patients have tumefactive lesions in the middle of their MS course,” said Dr. Pawate.

Another unusual presentation is concentric rings of demyelination, sometimes with mass effect. This variant is called Balo’s concentric sclerosis, and the patient may have typical MS lesions in addition to the rings. “Historically, Balo’s concentric sclerosis was thought to be a severe disease with a poor prognosis,” said Dr. Pawate. “With the advent of MRI, we know that these [rings] are more common than we initially thought, and more benign—not much different from any other MS lesions.”

Patients also may present with multiple large lesions and aggressive disease onset. Such patients need early treatment. “When I see something like this, I treat aggressively using plasma exchange and IV steroids,” said Dr. Pawate. This treatment may be followed by natalizumab infusions, and the patients may make a good recovery. “Historically, this aggressive MS onset was called Marburg variant and was fatal,” said Dr. Pawate.

MS Mimics

ADEM is more common in children than in adults, and imaging can distinguish it from MS. One distinguishing feature of ADEM is that the patient has many lesions that appear to be of the same age. Lesions may appear on the basal ganglia and the thalamus, which is atypical for MS. Spinal cord lesions tend to be longer in ADEM, compared with those in MS. ADEM tends to have a monophasic course, and patients usually present with encephalopathy, headaches, and vomiting. Patients often have a history of preceding vaccination or infection.

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) also can mimic MS on MRI. What distinguishes it from MS are lacunar infarcts, involvement in sites like the thalamus and basal ganglia, and gray matter involvement. CADASIL affects middle-aged adults and leads to disability and dementia.

If a patient referred for suspected MS has bilaterally symmetric confluent lesions, “think more in terms of leukodystrophies,” said Dr. Pawate. The absence of gadolinium enhancement is typical in leukodystrophies. The disorders may involve the U-fibers, the brainstem, or the cerebellum, and patients may present with cognitive decline.

Susac’s syndrome is a triad of branch retinal artery occlusion, sensorineural hearing loss, and encephalopathy. The syndrome is associated with a characteristic MRI that includes “spokes” (ie, linear lesions) and “snowballs” (ie, globular lesions) in the corpus callosum, as well as a “string of pearls” (ie, microinfarcts) in the internal capsule. In the eye, the most pathognomonic finding is hyperfluorescence of the arterial wall on fluorescein angiogram. Early treatment can produce good outcomes, but missing the diagnosis may quickly result in dementia, vision loss, and hearing loss.

Lupus can cause CNS manifestations, including cerebritis, vasculitis, and myelitis. “Primary CNS vasculitis can mimic MS on MRI sometimes, but the red flags are that the patient may have headache and infarcts on MRI, which are not seen in MS,” said Dr. Pawate. The white matter lesions in neurosarcoidosis can be similar to those in MS, but neurosarcoidosis also causes leptomeningeal enhancement and cranial nerve enhancement, which are not seen in MS.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Costello DJ, Eichler AF, Eichler FS. Leukodystrophies: classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurologist. 2009;15(6):319-328.

Kleinfeld K, Mobley B, Hedera P, et al. Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with neuroaxonal spheroids and pigmented glia: report of five cases and a new mutation. J Neurol. 2013;260(2):558-571.

Pawate S, Agarwal A, Moses H, Sriram S. The spectrum of Susac’s syndrome. Neurol Sci. 2009;30(1):59-64.

HILTON HEAD—Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common demyelinating disease, and its mimics are rare, according to an overview provided at the 39th Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium. Given that the treatments and outcomes for MS and its mimics are so different, neurologists should take care to establish a diagnosis early, said Sid Pawate, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville.

Because of the varied clinical presentation of MS, a wide variety of conditions enter the differential diagnosis. Because of the central role that MRI plays in MS diagnosis, imaging mimics that cause white matter lesions also need to be considered, said Dr. Pawate. Typically, the white matter lesions seen in MS are periventricular, juxtacortical, and callososeptal in location. Infratentorially, cerebellar peduncles are a common site. The lesions tend to be ovoid, are 3 mm to 5 mm or larger, and appear hyperintense on T2 and FLAIR sequences. Acute lesions may show restricted diffusion or enhancement after the administration of gadolinium contrast.

Typical Presentations of MS

The three most common presentations of MS are transverse myelitis, optic neuritis, and brainstem–cerebellar dysfunction. Acute partial transverse myelitis is “the most classic” form of transverse myelitis among patients with MS, said Dr. Pawate. Acute complete transverse myelitis, on the other hand, may be postinfectious or idiopathic, or seen as part of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Similarly, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis is more suggestive of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) than MS.

The most typical presentation of MS optic neuritis is unilateral and has acute or subacute onset. Patients often have retrobulbar, “gritty” pain when they move their eye. Complete blindness is unusual, and complete recovery occurs in nearly all patients. Hyperacute onset suggests a vascular process rather than optic neuritis, said Dr. Pawate. Slow, insidious onset may indicate an infiltrative process such as neoplasm or sarcoidosis. Painless vision loss may indicate ischemic optic neuropathy, and severe blindness without recovery may result from NMOSD.

The most pathognomonic brainstem dysfunction in MS is intranuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO), especially when it is bilateral. Other brainstem symptoms typical of MS include ataxia, painless diplopia, facial numbness, and trigeminal neuralgia in a young patient. Hyperacute or insidious onset of brainstem symptoms is unlikely to indicate MS. Symptoms that localize to a vascular territory usually result from a stroke. In addition, multiple cranial neuropathy is more suggestive of infections such as Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, or carcinomic ulcers.

Unusual Presentations of MS

Certain variants of MS do not present with the typical periventricular ovoid lesions. Tumefactive MS often presents with a large (ie, larger than 2 cm), solitary demyelinating lesion. These lesions usually are biopsied. Treatment with steroids usually brings improvement. After this first manifestation, the patient’s course is typical of relapsing-remitting MS. “Rarely do patients have tumefactive lesions in the middle of their MS course,” said Dr. Pawate.

Another unusual presentation is concentric rings of demyelination, sometimes with mass effect. This variant is called Balo’s concentric sclerosis, and the patient may have typical MS lesions in addition to the rings. “Historically, Balo’s concentric sclerosis was thought to be a severe disease with a poor prognosis,” said Dr. Pawate. “With the advent of MRI, we know that these [rings] are more common than we initially thought, and more benign—not much different from any other MS lesions.”

Patients also may present with multiple large lesions and aggressive disease onset. Such patients need early treatment. “When I see something like this, I treat aggressively using plasma exchange and IV steroids,” said Dr. Pawate. This treatment may be followed by natalizumab infusions, and the patients may make a good recovery. “Historically, this aggressive MS onset was called Marburg variant and was fatal,” said Dr. Pawate.

MS Mimics

ADEM is more common in children than in adults, and imaging can distinguish it from MS. One distinguishing feature of ADEM is that the patient has many lesions that appear to be of the same age. Lesions may appear on the basal ganglia and the thalamus, which is atypical for MS. Spinal cord lesions tend to be longer in ADEM, compared with those in MS. ADEM tends to have a monophasic course, and patients usually present with encephalopathy, headaches, and vomiting. Patients often have a history of preceding vaccination or infection.

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) also can mimic MS on MRI. What distinguishes it from MS are lacunar infarcts, involvement in sites like the thalamus and basal ganglia, and gray matter involvement. CADASIL affects middle-aged adults and leads to disability and dementia.

If a patient referred for suspected MS has bilaterally symmetric confluent lesions, “think more in terms of leukodystrophies,” said Dr. Pawate. The absence of gadolinium enhancement is typical in leukodystrophies. The disorders may involve the U-fibers, the brainstem, or the cerebellum, and patients may present with cognitive decline.

Susac’s syndrome is a triad of branch retinal artery occlusion, sensorineural hearing loss, and encephalopathy. The syndrome is associated with a characteristic MRI that includes “spokes” (ie, linear lesions) and “snowballs” (ie, globular lesions) in the corpus callosum, as well as a “string of pearls” (ie, microinfarcts) in the internal capsule. In the eye, the most pathognomonic finding is hyperfluorescence of the arterial wall on fluorescein angiogram. Early treatment can produce good outcomes, but missing the diagnosis may quickly result in dementia, vision loss, and hearing loss.

Lupus can cause CNS manifestations, including cerebritis, vasculitis, and myelitis. “Primary CNS vasculitis can mimic MS on MRI sometimes, but the red flags are that the patient may have headache and infarcts on MRI, which are not seen in MS,” said Dr. Pawate. The white matter lesions in neurosarcoidosis can be similar to those in MS, but neurosarcoidosis also causes leptomeningeal enhancement and cranial nerve enhancement, which are not seen in MS.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Costello DJ, Eichler AF, Eichler FS. Leukodystrophies: classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurologist. 2009;15(6):319-328.

Kleinfeld K, Mobley B, Hedera P, et al. Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with neuroaxonal spheroids and pigmented glia: report of five cases and a new mutation. J Neurol. 2013;260(2):558-571.

Pawate S, Agarwal A, Moses H, Sriram S. The spectrum of Susac’s syndrome. Neurol Sci. 2009;30(1):59-64.

HILTON HEAD—Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common demyelinating disease, and its mimics are rare, according to an overview provided at the 39th Annual Contemporary Clinical Neurology Symposium. Given that the treatments and outcomes for MS and its mimics are so different, neurologists should take care to establish a diagnosis early, said Sid Pawate, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville.

Because of the varied clinical presentation of MS, a wide variety of conditions enter the differential diagnosis. Because of the central role that MRI plays in MS diagnosis, imaging mimics that cause white matter lesions also need to be considered, said Dr. Pawate. Typically, the white matter lesions seen in MS are periventricular, juxtacortical, and callososeptal in location. Infratentorially, cerebellar peduncles are a common site. The lesions tend to be ovoid, are 3 mm to 5 mm or larger, and appear hyperintense on T2 and FLAIR sequences. Acute lesions may show restricted diffusion or enhancement after the administration of gadolinium contrast.

Typical Presentations of MS

The three most common presentations of MS are transverse myelitis, optic neuritis, and brainstem–cerebellar dysfunction. Acute partial transverse myelitis is “the most classic” form of transverse myelitis among patients with MS, said Dr. Pawate. Acute complete transverse myelitis, on the other hand, may be postinfectious or idiopathic, or seen as part of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Similarly, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis is more suggestive of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) than MS.

The most typical presentation of MS optic neuritis is unilateral and has acute or subacute onset. Patients often have retrobulbar, “gritty” pain when they move their eye. Complete blindness is unusual, and complete recovery occurs in nearly all patients. Hyperacute onset suggests a vascular process rather than optic neuritis, said Dr. Pawate. Slow, insidious onset may indicate an infiltrative process such as neoplasm or sarcoidosis. Painless vision loss may indicate ischemic optic neuropathy, and severe blindness without recovery may result from NMOSD.

The most pathognomonic brainstem dysfunction in MS is intranuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO), especially when it is bilateral. Other brainstem symptoms typical of MS include ataxia, painless diplopia, facial numbness, and trigeminal neuralgia in a young patient. Hyperacute or insidious onset of brainstem symptoms is unlikely to indicate MS. Symptoms that localize to a vascular territory usually result from a stroke. In addition, multiple cranial neuropathy is more suggestive of infections such as Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, or carcinomic ulcers.

Unusual Presentations of MS

Certain variants of MS do not present with the typical periventricular ovoid lesions. Tumefactive MS often presents with a large (ie, larger than 2 cm), solitary demyelinating lesion. These lesions usually are biopsied. Treatment with steroids usually brings improvement. After this first manifestation, the patient’s course is typical of relapsing-remitting MS. “Rarely do patients have tumefactive lesions in the middle of their MS course,” said Dr. Pawate.

Another unusual presentation is concentric rings of demyelination, sometimes with mass effect. This variant is called Balo’s concentric sclerosis, and the patient may have typical MS lesions in addition to the rings. “Historically, Balo’s concentric sclerosis was thought to be a severe disease with a poor prognosis,” said Dr. Pawate. “With the advent of MRI, we know that these [rings] are more common than we initially thought, and more benign—not much different from any other MS lesions.”

Patients also may present with multiple large lesions and aggressive disease onset. Such patients need early treatment. “When I see something like this, I treat aggressively using plasma exchange and IV steroids,” said Dr. Pawate. This treatment may be followed by natalizumab infusions, and the patients may make a good recovery. “Historically, this aggressive MS onset was called Marburg variant and was fatal,” said Dr. Pawate.

MS Mimics

ADEM is more common in children than in adults, and imaging can distinguish it from MS. One distinguishing feature of ADEM is that the patient has many lesions that appear to be of the same age. Lesions may appear on the basal ganglia and the thalamus, which is atypical for MS. Spinal cord lesions tend to be longer in ADEM, compared with those in MS. ADEM tends to have a monophasic course, and patients usually present with encephalopathy, headaches, and vomiting. Patients often have a history of preceding vaccination or infection.

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) also can mimic MS on MRI. What distinguishes it from MS are lacunar infarcts, involvement in sites like the thalamus and basal ganglia, and gray matter involvement. CADASIL affects middle-aged adults and leads to disability and dementia.

If a patient referred for suspected MS has bilaterally symmetric confluent lesions, “think more in terms of leukodystrophies,” said Dr. Pawate. The absence of gadolinium enhancement is typical in leukodystrophies. The disorders may involve the U-fibers, the brainstem, or the cerebellum, and patients may present with cognitive decline.