User login

New and Noteworthy Information—October 2016

Resective surgery for epilepsy is cost-effective in the medium term, according to a study published online ahead of print September 5 in Epilepsia. A prospective cohort of adult patients with surgically remediable and medically intractable partial epilepsy was followed for more than five years in 15 French centers. During the second year of follow-up, the proportion of patients who had been completely seizure-free for the previous 12 months was 69.0% among participants who underwent surgery and 12.3% in the medical group. The respective rates of seizure freedom were 76.8% and 21% during the fifth year. Direct costs became significantly lower in the surgical group during the third year after surgery as a result of decreased antiepileptic drug use. Surgery became cost-effective between nine and 10 years after surgery.

The NIH Toolbox Cognitive Battery can assess important dimensions of cognition in persons with intellectual disabilities, and several tests may be useful for tracking response to interventions, according to a study published September 6 in the Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. In separate pilot studies of patients with fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome, and idiopathic intellectual disabilities, researchers used the web-based NIH Toolbox Cognitive Battery to measure processing speed, executive function, episodic memory, word and letter reading, receptive vocabulary, and working memory. The test's feasibility was good to excellent for people above mental age 4 for all tests except list sorting. Test-retest stability was good to excellent. More extensive psychometric studies are needed to determine the battery's true utility as a set of outcome measures, said the researchers.

Graded aerobic treadmill testing is a safe, tolerable, and clinically valuable tool that can assist in the evaluation and management of pediatric sports-related concussion, according to a study published online ahead of print September 13 in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics. Researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of 106 pediatric patients with sports-related concussion who were referred to a multidisciplinary pediatric concussion program and underwent graded aerobic treadmill testing between October 9, 2014, and February 11, 2016. Treadmill testing confirmed physiologic recovery in 96.9% of 65 patients tested, allowing successful return to play in 93.8% of patients. Of the 41 patients with physiologic post-concussion disorder who had complete follow-up and were treated with tailored submaximal exercise, 90.2% were classified as clinically improved and 80.5% successfully returned to sporting activities.

Exposure to MRI during the first trimester of pregnancy, compared with nonexposure, is not associated with increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, according to a study published September 6 in JAMA. Gadolinium MRI, however, was associated with an increased risk of rheumatologic, inflammatory, or infiltrative skin conditions, and stillbirth or neonatal death. The study included 1,424,105 deliveries. Researchers compared first-trimester MRI exposure to no MRI exposure. The adjusted relative risk of stillbirth, congenital anomalies, neoplasm, or vision or hearing loss for first-trimester MRI was not significantly higher, compared with no MRI exposure. Comparing gadolinium MRI with no MRI, the adjusted hazard ratio of any rheumatologic, inflammatory, or infiltrative skin condition for first-trimester MRI was 1.36, for an adjusted risk difference of 45.3 per 1,000 person-years.

In women in the United Kingdom, higher BMI is associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke, but decreased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, according to a study published online ahead of print September 7 in Neurology. Researchers recruited 1.3 million previously stroke-free women from the UK between 1996 and 2001 and followed them by record linkage for hospital admissions and deaths. Increased BMI was associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, but a decreased risk of hemorrhagic stroke. The BMI-associated trends for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke were significantly different, but were not significantly different for intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Published data from prospective studies showed consistently greater BMI-associated relative risks for ischemic stroke than hemorrhagic stroke, with most evidence before this study coming from Asian populations.

Data confirm the relevance of complement biomarkers in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease, according to a study published September 6 in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. Results also indicate the value of multiparameter models for disease prediction and stratification. Researchers studied 292 people to measure five complement proteins and four activation products in plasma from donors with MCI, those with Alzheimer's disease, and healthy controls. Only clusterin differed significantly between control and Alzheimer's disease plasma. Overall, a model combining clusterin with relevant covariables was highly predictive of disease. Clusterin, factor I, and terminal complement complex were significantly different between individuals with MCI who had converted to dementia one year later compared with nonconverters. A model combining these three analytes with informative covariables was highly predictive of conversion.

Prenatal exposure to levetiracetam or topiramate may not impair a child's thinking skills, according to a study published online ahead of print August 31 in Neurology. For this cross-sectional observational study, researchers followed women enrolled in the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. The women received monotherapy levetiracetam, topiramate, or valproate, or took no therapy. Physicians conducted assessor-blinded neuropsychologic assessments of the women's children between ages 5 and 9. In the adjusted analyses, prenatal exposure to levetiracetam and topiramate were not found to be associated with reductions in children's cognitive abilities, and adverse outcomes were not associated with increasing dose. Increasing the dose of valproate was associated with poorer full-scale IQ, verbal abilities, nonverbal abilities, and expressive language ability. The evidence base for newer antiepileptic drugs is limited, said the authors.

At six months, decompressive craniectomy in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and refractory intracranial hypertension results in lower mortality and higher rates of vegetative state and severe disability, compared with medical care, according to a study published online ahead of print September 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers randomly assigned 408 patients, ages 10 to 65, with TBI and refractory elevated intracranial pressure to undergo decompressive craniectomy or receive ongoing medical care. At six months, approximately 27% of patients who received a craniectomy had died, compared with 49% of patients who received medical management. Patients who survived after a craniectomy were more likely to be dependent on others for care. At 12 months, mortality was 30% among surgical patients and 52% among medical patients.

Contralaterally controlled functional electrical stimulation (CCFES) improves hand dexterity after stroke more than cyclic neuromuscular electrical stimulation (cNMES) does, according to a study published online ahead of print September 8 in Stroke. Researchers enrolled 80 patients with stroke and chronic moderate to severe upper extremity hemiparesis in the study. Participants were randomized to receive 10 sessions per week of CCFES- or cNMES-assisted hand-opening exercise at home, along with 20 sessions of functional task practice in the laboratory for 12 weeks. At six months post treatment, the CCFES group had an improvement of 4.6 on the Box and Block Test, compared with an improvement of 1.8 for the cNMES group. Fugl-Meyer performance and Arm Motor Abilities Test performance did not differ between groups, however.

Antipsychotic use is associated with higher risk of pneumonia, regardless of the choice of drug, according to a study published online ahead of print June 11 in Chest. Researchers investigated whether incident antipsychotic use or specific antipsychotics are related to higher risk of hospitalization or death due to pneumonia in the MEDALZ cohort. The cohort includes all persons who received a clinically verified diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in Finland from 2005 to 2011. A matched comparison cohort without Alzheimer's disease was used to compare the magnitude of risk. Antipsychotic use was associated with higher risk of pneumonia in the Alzheimer's disease cohort and with somewhat higher risk in the comparison cohort. No major differences were observed between the most commonly used antipsychotics.

The FDA has allowed the marketing of two Trevo clot-retrieval devices as an initial therapy to reduce paralysis, speech difficulties, and other disabilities following ischemic stroke. The agency evaluated data from a clinical trial comparing 96 randomly selected patients treated with the Trevo device and t-PA and medical management with 249 patients who received only t-PA and medical management. Twenty-nine percent of patients treated with the Trevo device were functionally independent at three months after stroke, compared with 19% of patients who were not treated with the Trevo device. These devices should be used within six hours of symptom onset and only following treatment with a clot-dissolving drug, which needs to be given within three hours of symptom onset, said the FDA. Concentric Medical, headquartered in Mountain View, California, markets Trevo.

Class I evidence suggests that for boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, daily use of deflazacort or prednisone is effective in preserving muscle strength over a 12-week period, according to a study published online ahead of print August 26 in Neurology. This phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study evaluated the muscle strength of 196 boys ages 5 to 15 with Duchenne muscular dystrophy during a 52-week period. Participants received deflazacort, prednisone, or placebo for 12 weeks. At week 13, patients continued active treatment or switched from placebo to active treatment. All treatment groups demonstrated significant improvement in muscle strength, compared with placebo, at 12 weeks. Participants taking prednisone had significantly more weight gain than other participants at 12 weeks and at 52 weeks.

The FDA has granted tentative approval to Supernus Pharmaceuticals's Supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) requesting a label expansion for Trokendi XR (topiramate) to include prophylaxis of migraine headache in adults. The approval of the sNDA is tentative because the FDA has determined that the drug meets all of the required quality, safety, and efficacy standards for approval, but is subject to the pediatric exclusivity, which expires on March 28, 2017. Final approval may not be made effective until this exclusivity period has expired. The FDA also has granted final approval to expand the label for Trokendi XR for monotherapy treatment of partial onset seizures to include adults and pediatric patients age six and older, rather than age 10 and older. Supernus Pharmaceuticals is headquartered in Rockville, Maryland.

—Kimberly Williams

Resective surgery for epilepsy is cost-effective in the medium term, according to a study published online ahead of print September 5 in Epilepsia. A prospective cohort of adult patients with surgically remediable and medically intractable partial epilepsy was followed for more than five years in 15 French centers. During the second year of follow-up, the proportion of patients who had been completely seizure-free for the previous 12 months was 69.0% among participants who underwent surgery and 12.3% in the medical group. The respective rates of seizure freedom were 76.8% and 21% during the fifth year. Direct costs became significantly lower in the surgical group during the third year after surgery as a result of decreased antiepileptic drug use. Surgery became cost-effective between nine and 10 years after surgery.

The NIH Toolbox Cognitive Battery can assess important dimensions of cognition in persons with intellectual disabilities, and several tests may be useful for tracking response to interventions, according to a study published September 6 in the Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. In separate pilot studies of patients with fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome, and idiopathic intellectual disabilities, researchers used the web-based NIH Toolbox Cognitive Battery to measure processing speed, executive function, episodic memory, word and letter reading, receptive vocabulary, and working memory. The test's feasibility was good to excellent for people above mental age 4 for all tests except list sorting. Test-retest stability was good to excellent. More extensive psychometric studies are needed to determine the battery's true utility as a set of outcome measures, said the researchers.

Graded aerobic treadmill testing is a safe, tolerable, and clinically valuable tool that can assist in the evaluation and management of pediatric sports-related concussion, according to a study published online ahead of print September 13 in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics. Researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of 106 pediatric patients with sports-related concussion who were referred to a multidisciplinary pediatric concussion program and underwent graded aerobic treadmill testing between October 9, 2014, and February 11, 2016. Treadmill testing confirmed physiologic recovery in 96.9% of 65 patients tested, allowing successful return to play in 93.8% of patients. Of the 41 patients with physiologic post-concussion disorder who had complete follow-up and were treated with tailored submaximal exercise, 90.2% were classified as clinically improved and 80.5% successfully returned to sporting activities.

Exposure to MRI during the first trimester of pregnancy, compared with nonexposure, is not associated with increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, according to a study published September 6 in JAMA. Gadolinium MRI, however, was associated with an increased risk of rheumatologic, inflammatory, or infiltrative skin conditions, and stillbirth or neonatal death. The study included 1,424,105 deliveries. Researchers compared first-trimester MRI exposure to no MRI exposure. The adjusted relative risk of stillbirth, congenital anomalies, neoplasm, or vision or hearing loss for first-trimester MRI was not significantly higher, compared with no MRI exposure. Comparing gadolinium MRI with no MRI, the adjusted hazard ratio of any rheumatologic, inflammatory, or infiltrative skin condition for first-trimester MRI was 1.36, for an adjusted risk difference of 45.3 per 1,000 person-years.

In women in the United Kingdom, higher BMI is associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke, but decreased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, according to a study published online ahead of print September 7 in Neurology. Researchers recruited 1.3 million previously stroke-free women from the UK between 1996 and 2001 and followed them by record linkage for hospital admissions and deaths. Increased BMI was associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, but a decreased risk of hemorrhagic stroke. The BMI-associated trends for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke were significantly different, but were not significantly different for intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Published data from prospective studies showed consistently greater BMI-associated relative risks for ischemic stroke than hemorrhagic stroke, with most evidence before this study coming from Asian populations.

Data confirm the relevance of complement biomarkers in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease, according to a study published September 6 in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. Results also indicate the value of multiparameter models for disease prediction and stratification. Researchers studied 292 people to measure five complement proteins and four activation products in plasma from donors with MCI, those with Alzheimer's disease, and healthy controls. Only clusterin differed significantly between control and Alzheimer's disease plasma. Overall, a model combining clusterin with relevant covariables was highly predictive of disease. Clusterin, factor I, and terminal complement complex were significantly different between individuals with MCI who had converted to dementia one year later compared with nonconverters. A model combining these three analytes with informative covariables was highly predictive of conversion.

Prenatal exposure to levetiracetam or topiramate may not impair a child's thinking skills, according to a study published online ahead of print August 31 in Neurology. For this cross-sectional observational study, researchers followed women enrolled in the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. The women received monotherapy levetiracetam, topiramate, or valproate, or took no therapy. Physicians conducted assessor-blinded neuropsychologic assessments of the women's children between ages 5 and 9. In the adjusted analyses, prenatal exposure to levetiracetam and topiramate were not found to be associated with reductions in children's cognitive abilities, and adverse outcomes were not associated with increasing dose. Increasing the dose of valproate was associated with poorer full-scale IQ, verbal abilities, nonverbal abilities, and expressive language ability. The evidence base for newer antiepileptic drugs is limited, said the authors.

At six months, decompressive craniectomy in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and refractory intracranial hypertension results in lower mortality and higher rates of vegetative state and severe disability, compared with medical care, according to a study published online ahead of print September 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers randomly assigned 408 patients, ages 10 to 65, with TBI and refractory elevated intracranial pressure to undergo decompressive craniectomy or receive ongoing medical care. At six months, approximately 27% of patients who received a craniectomy had died, compared with 49% of patients who received medical management. Patients who survived after a craniectomy were more likely to be dependent on others for care. At 12 months, mortality was 30% among surgical patients and 52% among medical patients.

Contralaterally controlled functional electrical stimulation (CCFES) improves hand dexterity after stroke more than cyclic neuromuscular electrical stimulation (cNMES) does, according to a study published online ahead of print September 8 in Stroke. Researchers enrolled 80 patients with stroke and chronic moderate to severe upper extremity hemiparesis in the study. Participants were randomized to receive 10 sessions per week of CCFES- or cNMES-assisted hand-opening exercise at home, along with 20 sessions of functional task practice in the laboratory for 12 weeks. At six months post treatment, the CCFES group had an improvement of 4.6 on the Box and Block Test, compared with an improvement of 1.8 for the cNMES group. Fugl-Meyer performance and Arm Motor Abilities Test performance did not differ between groups, however.

Antipsychotic use is associated with higher risk of pneumonia, regardless of the choice of drug, according to a study published online ahead of print June 11 in Chest. Researchers investigated whether incident antipsychotic use or specific antipsychotics are related to higher risk of hospitalization or death due to pneumonia in the MEDALZ cohort. The cohort includes all persons who received a clinically verified diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in Finland from 2005 to 2011. A matched comparison cohort without Alzheimer's disease was used to compare the magnitude of risk. Antipsychotic use was associated with higher risk of pneumonia in the Alzheimer's disease cohort and with somewhat higher risk in the comparison cohort. No major differences were observed between the most commonly used antipsychotics.

The FDA has allowed the marketing of two Trevo clot-retrieval devices as an initial therapy to reduce paralysis, speech difficulties, and other disabilities following ischemic stroke. The agency evaluated data from a clinical trial comparing 96 randomly selected patients treated with the Trevo device and t-PA and medical management with 249 patients who received only t-PA and medical management. Twenty-nine percent of patients treated with the Trevo device were functionally independent at three months after stroke, compared with 19% of patients who were not treated with the Trevo device. These devices should be used within six hours of symptom onset and only following treatment with a clot-dissolving drug, which needs to be given within three hours of symptom onset, said the FDA. Concentric Medical, headquartered in Mountain View, California, markets Trevo.

Class I evidence suggests that for boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, daily use of deflazacort or prednisone is effective in preserving muscle strength over a 12-week period, according to a study published online ahead of print August 26 in Neurology. This phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study evaluated the muscle strength of 196 boys ages 5 to 15 with Duchenne muscular dystrophy during a 52-week period. Participants received deflazacort, prednisone, or placebo for 12 weeks. At week 13, patients continued active treatment or switched from placebo to active treatment. All treatment groups demonstrated significant improvement in muscle strength, compared with placebo, at 12 weeks. Participants taking prednisone had significantly more weight gain than other participants at 12 weeks and at 52 weeks.

The FDA has granted tentative approval to Supernus Pharmaceuticals's Supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) requesting a label expansion for Trokendi XR (topiramate) to include prophylaxis of migraine headache in adults. The approval of the sNDA is tentative because the FDA has determined that the drug meets all of the required quality, safety, and efficacy standards for approval, but is subject to the pediatric exclusivity, which expires on March 28, 2017. Final approval may not be made effective until this exclusivity period has expired. The FDA also has granted final approval to expand the label for Trokendi XR for monotherapy treatment of partial onset seizures to include adults and pediatric patients age six and older, rather than age 10 and older. Supernus Pharmaceuticals is headquartered in Rockville, Maryland.

—Kimberly Williams

Resective surgery for epilepsy is cost-effective in the medium term, according to a study published online ahead of print September 5 in Epilepsia. A prospective cohort of adult patients with surgically remediable and medically intractable partial epilepsy was followed for more than five years in 15 French centers. During the second year of follow-up, the proportion of patients who had been completely seizure-free for the previous 12 months was 69.0% among participants who underwent surgery and 12.3% in the medical group. The respective rates of seizure freedom were 76.8% and 21% during the fifth year. Direct costs became significantly lower in the surgical group during the third year after surgery as a result of decreased antiepileptic drug use. Surgery became cost-effective between nine and 10 years after surgery.

The NIH Toolbox Cognitive Battery can assess important dimensions of cognition in persons with intellectual disabilities, and several tests may be useful for tracking response to interventions, according to a study published September 6 in the Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. In separate pilot studies of patients with fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome, and idiopathic intellectual disabilities, researchers used the web-based NIH Toolbox Cognitive Battery to measure processing speed, executive function, episodic memory, word and letter reading, receptive vocabulary, and working memory. The test's feasibility was good to excellent for people above mental age 4 for all tests except list sorting. Test-retest stability was good to excellent. More extensive psychometric studies are needed to determine the battery's true utility as a set of outcome measures, said the researchers.

Graded aerobic treadmill testing is a safe, tolerable, and clinically valuable tool that can assist in the evaluation and management of pediatric sports-related concussion, according to a study published online ahead of print September 13 in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics. Researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of 106 pediatric patients with sports-related concussion who were referred to a multidisciplinary pediatric concussion program and underwent graded aerobic treadmill testing between October 9, 2014, and February 11, 2016. Treadmill testing confirmed physiologic recovery in 96.9% of 65 patients tested, allowing successful return to play in 93.8% of patients. Of the 41 patients with physiologic post-concussion disorder who had complete follow-up and were treated with tailored submaximal exercise, 90.2% were classified as clinically improved and 80.5% successfully returned to sporting activities.

Exposure to MRI during the first trimester of pregnancy, compared with nonexposure, is not associated with increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, according to a study published September 6 in JAMA. Gadolinium MRI, however, was associated with an increased risk of rheumatologic, inflammatory, or infiltrative skin conditions, and stillbirth or neonatal death. The study included 1,424,105 deliveries. Researchers compared first-trimester MRI exposure to no MRI exposure. The adjusted relative risk of stillbirth, congenital anomalies, neoplasm, or vision or hearing loss for first-trimester MRI was not significantly higher, compared with no MRI exposure. Comparing gadolinium MRI with no MRI, the adjusted hazard ratio of any rheumatologic, inflammatory, or infiltrative skin condition for first-trimester MRI was 1.36, for an adjusted risk difference of 45.3 per 1,000 person-years.

In women in the United Kingdom, higher BMI is associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke, but decreased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, according to a study published online ahead of print September 7 in Neurology. Researchers recruited 1.3 million previously stroke-free women from the UK between 1996 and 2001 and followed them by record linkage for hospital admissions and deaths. Increased BMI was associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, but a decreased risk of hemorrhagic stroke. The BMI-associated trends for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke were significantly different, but were not significantly different for intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Published data from prospective studies showed consistently greater BMI-associated relative risks for ischemic stroke than hemorrhagic stroke, with most evidence before this study coming from Asian populations.

Data confirm the relevance of complement biomarkers in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease, according to a study published September 6 in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. Results also indicate the value of multiparameter models for disease prediction and stratification. Researchers studied 292 people to measure five complement proteins and four activation products in plasma from donors with MCI, those with Alzheimer's disease, and healthy controls. Only clusterin differed significantly between control and Alzheimer's disease plasma. Overall, a model combining clusterin with relevant covariables was highly predictive of disease. Clusterin, factor I, and terminal complement complex were significantly different between individuals with MCI who had converted to dementia one year later compared with nonconverters. A model combining these three analytes with informative covariables was highly predictive of conversion.

Prenatal exposure to levetiracetam or topiramate may not impair a child's thinking skills, according to a study published online ahead of print August 31 in Neurology. For this cross-sectional observational study, researchers followed women enrolled in the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. The women received monotherapy levetiracetam, topiramate, or valproate, or took no therapy. Physicians conducted assessor-blinded neuropsychologic assessments of the women's children between ages 5 and 9. In the adjusted analyses, prenatal exposure to levetiracetam and topiramate were not found to be associated with reductions in children's cognitive abilities, and adverse outcomes were not associated with increasing dose. Increasing the dose of valproate was associated with poorer full-scale IQ, verbal abilities, nonverbal abilities, and expressive language ability. The evidence base for newer antiepileptic drugs is limited, said the authors.

At six months, decompressive craniectomy in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and refractory intracranial hypertension results in lower mortality and higher rates of vegetative state and severe disability, compared with medical care, according to a study published online ahead of print September 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers randomly assigned 408 patients, ages 10 to 65, with TBI and refractory elevated intracranial pressure to undergo decompressive craniectomy or receive ongoing medical care. At six months, approximately 27% of patients who received a craniectomy had died, compared with 49% of patients who received medical management. Patients who survived after a craniectomy were more likely to be dependent on others for care. At 12 months, mortality was 30% among surgical patients and 52% among medical patients.

Contralaterally controlled functional electrical stimulation (CCFES) improves hand dexterity after stroke more than cyclic neuromuscular electrical stimulation (cNMES) does, according to a study published online ahead of print September 8 in Stroke. Researchers enrolled 80 patients with stroke and chronic moderate to severe upper extremity hemiparesis in the study. Participants were randomized to receive 10 sessions per week of CCFES- or cNMES-assisted hand-opening exercise at home, along with 20 sessions of functional task practice in the laboratory for 12 weeks. At six months post treatment, the CCFES group had an improvement of 4.6 on the Box and Block Test, compared with an improvement of 1.8 for the cNMES group. Fugl-Meyer performance and Arm Motor Abilities Test performance did not differ between groups, however.

Antipsychotic use is associated with higher risk of pneumonia, regardless of the choice of drug, according to a study published online ahead of print June 11 in Chest. Researchers investigated whether incident antipsychotic use or specific antipsychotics are related to higher risk of hospitalization or death due to pneumonia in the MEDALZ cohort. The cohort includes all persons who received a clinically verified diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in Finland from 2005 to 2011. A matched comparison cohort without Alzheimer's disease was used to compare the magnitude of risk. Antipsychotic use was associated with higher risk of pneumonia in the Alzheimer's disease cohort and with somewhat higher risk in the comparison cohort. No major differences were observed between the most commonly used antipsychotics.

The FDA has allowed the marketing of two Trevo clot-retrieval devices as an initial therapy to reduce paralysis, speech difficulties, and other disabilities following ischemic stroke. The agency evaluated data from a clinical trial comparing 96 randomly selected patients treated with the Trevo device and t-PA and medical management with 249 patients who received only t-PA and medical management. Twenty-nine percent of patients treated with the Trevo device were functionally independent at three months after stroke, compared with 19% of patients who were not treated with the Trevo device. These devices should be used within six hours of symptom onset and only following treatment with a clot-dissolving drug, which needs to be given within three hours of symptom onset, said the FDA. Concentric Medical, headquartered in Mountain View, California, markets Trevo.

Class I evidence suggests that for boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, daily use of deflazacort or prednisone is effective in preserving muscle strength over a 12-week period, according to a study published online ahead of print August 26 in Neurology. This phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study evaluated the muscle strength of 196 boys ages 5 to 15 with Duchenne muscular dystrophy during a 52-week period. Participants received deflazacort, prednisone, or placebo for 12 weeks. At week 13, patients continued active treatment or switched from placebo to active treatment. All treatment groups demonstrated significant improvement in muscle strength, compared with placebo, at 12 weeks. Participants taking prednisone had significantly more weight gain than other participants at 12 weeks and at 52 weeks.

The FDA has granted tentative approval to Supernus Pharmaceuticals's Supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) requesting a label expansion for Trokendi XR (topiramate) to include prophylaxis of migraine headache in adults. The approval of the sNDA is tentative because the FDA has determined that the drug meets all of the required quality, safety, and efficacy standards for approval, but is subject to the pediatric exclusivity, which expires on March 28, 2017. Final approval may not be made effective until this exclusivity period has expired. The FDA also has granted final approval to expand the label for Trokendi XR for monotherapy treatment of partial onset seizures to include adults and pediatric patients age six and older, rather than age 10 and older. Supernus Pharmaceuticals is headquartered in Rockville, Maryland.

—Kimberly Williams

Product News: October 2016

Carmex Comfort Care

Carma Labs Inc introduces Carmex Comfort Care lip balm, a natural lip care product formulated with colloidal oatmeal and cold-pressed fruit oil to deliver soothing, long-lasting moisture and hydration. Colloidal oatmeal also possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that benefit sensitive drug skin, especially on the lips. For more information, visit www.mycarmex.com.

Erelzi

Sandoz Inc, a Novartis Division, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Erelzi (etanercept-szzs) for all indications included in the reference product label: rheumatoid arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Erelzi is the second approved biosimilar from Sandoz. For more information, visit www.erelzi.com.

Loprox Cream

Medimetriks Pharmaceuticals, Inc, announces the launch of Loprox (ciclopirox) Cream 0.77% and the Loprox Cream Kit. Loprox Cream is a broad-spectrum therapy that treats 5 different skin infections from 6 different pathogens. It is indicated for the topical treatment of tinea pedis, tinea cruris, and tinea corporis due to Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Epidermophyton floccosum, and Microsporum canis; candidiasis due to Candia albicans; and tinea (pityriasis) versicolor due to Malassezia furfur. Loprox Cream works quickly, usually within the first week (2 weeks for tinea versicolor), providing patients needed relief of pruritus and other symptoms. The Loprox Cream Kit includes Loprox Cream and Rehyla Hair + Body Cleanser for patient convenience. The cleanser hydrates and conditions and is gentle for daily use on the scalp and body. For more information, visit www.medimetriks.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Carmex Comfort Care

Carma Labs Inc introduces Carmex Comfort Care lip balm, a natural lip care product formulated with colloidal oatmeal and cold-pressed fruit oil to deliver soothing, long-lasting moisture and hydration. Colloidal oatmeal also possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that benefit sensitive drug skin, especially on the lips. For more information, visit www.mycarmex.com.

Erelzi

Sandoz Inc, a Novartis Division, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Erelzi (etanercept-szzs) for all indications included in the reference product label: rheumatoid arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Erelzi is the second approved biosimilar from Sandoz. For more information, visit www.erelzi.com.

Loprox Cream

Medimetriks Pharmaceuticals, Inc, announces the launch of Loprox (ciclopirox) Cream 0.77% and the Loprox Cream Kit. Loprox Cream is a broad-spectrum therapy that treats 5 different skin infections from 6 different pathogens. It is indicated for the topical treatment of tinea pedis, tinea cruris, and tinea corporis due to Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Epidermophyton floccosum, and Microsporum canis; candidiasis due to Candia albicans; and tinea (pityriasis) versicolor due to Malassezia furfur. Loprox Cream works quickly, usually within the first week (2 weeks for tinea versicolor), providing patients needed relief of pruritus and other symptoms. The Loprox Cream Kit includes Loprox Cream and Rehyla Hair + Body Cleanser for patient convenience. The cleanser hydrates and conditions and is gentle for daily use on the scalp and body. For more information, visit www.medimetriks.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Carmex Comfort Care

Carma Labs Inc introduces Carmex Comfort Care lip balm, a natural lip care product formulated with colloidal oatmeal and cold-pressed fruit oil to deliver soothing, long-lasting moisture and hydration. Colloidal oatmeal also possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that benefit sensitive drug skin, especially on the lips. For more information, visit www.mycarmex.com.

Erelzi

Sandoz Inc, a Novartis Division, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Erelzi (etanercept-szzs) for all indications included in the reference product label: rheumatoid arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Erelzi is the second approved biosimilar from Sandoz. For more information, visit www.erelzi.com.

Loprox Cream

Medimetriks Pharmaceuticals, Inc, announces the launch of Loprox (ciclopirox) Cream 0.77% and the Loprox Cream Kit. Loprox Cream is a broad-spectrum therapy that treats 5 different skin infections from 6 different pathogens. It is indicated for the topical treatment of tinea pedis, tinea cruris, and tinea corporis due to Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Epidermophyton floccosum, and Microsporum canis; candidiasis due to Candia albicans; and tinea (pityriasis) versicolor due to Malassezia furfur. Loprox Cream works quickly, usually within the first week (2 weeks for tinea versicolor), providing patients needed relief of pruritus and other symptoms. The Loprox Cream Kit includes Loprox Cream and Rehyla Hair + Body Cleanser for patient convenience. The cleanser hydrates and conditions and is gentle for daily use on the scalp and body. For more information, visit www.medimetriks.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Complementary medicine impedes children’s flu vaccination

Children treated with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies were significantly less likely to receive the annual influenza vaccine than those who didn’t use alternative medicine, based on data from 9,000 children aged 4-17 years in the Child Complementary and Alternative Medicine File of the 2012 National Health Interview Survey.

“CAM has been implicated as lending support to antivaccine/vaccine-hesitant viewpoints via criticism of vaccination, public health, and conventional medicine from adults using CAM, as well as from CAM practitioners and practitioners-in-training,” wrote William K. Bleser, Ph.D., and his colleagues at Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

No significant differences in vaccination rates were noted for children who had used three other categories of nonconventional care: biologically based therapies (such as herbal supplements), mind-body therapies (such as yoga), and multivitamins.

“There is an opportunity for U.S. public health, policy, and conventional medical professionals and educators to improve vaccine uptake and child health by better engaging both CAM and conventional medicine practitioners-in-training, parents of children using particular domains of CAM, and the CAM practitioners advising them,” the researchers said.

Find the full article in Pediatrics (2016. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4664).

Children treated with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies were significantly less likely to receive the annual influenza vaccine than those who didn’t use alternative medicine, based on data from 9,000 children aged 4-17 years in the Child Complementary and Alternative Medicine File of the 2012 National Health Interview Survey.

“CAM has been implicated as lending support to antivaccine/vaccine-hesitant viewpoints via criticism of vaccination, public health, and conventional medicine from adults using CAM, as well as from CAM practitioners and practitioners-in-training,” wrote William K. Bleser, Ph.D., and his colleagues at Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

No significant differences in vaccination rates were noted for children who had used three other categories of nonconventional care: biologically based therapies (such as herbal supplements), mind-body therapies (such as yoga), and multivitamins.

“There is an opportunity for U.S. public health, policy, and conventional medical professionals and educators to improve vaccine uptake and child health by better engaging both CAM and conventional medicine practitioners-in-training, parents of children using particular domains of CAM, and the CAM practitioners advising them,” the researchers said.

Find the full article in Pediatrics (2016. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4664).

Children treated with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies were significantly less likely to receive the annual influenza vaccine than those who didn’t use alternative medicine, based on data from 9,000 children aged 4-17 years in the Child Complementary and Alternative Medicine File of the 2012 National Health Interview Survey.

“CAM has been implicated as lending support to antivaccine/vaccine-hesitant viewpoints via criticism of vaccination, public health, and conventional medicine from adults using CAM, as well as from CAM practitioners and practitioners-in-training,” wrote William K. Bleser, Ph.D., and his colleagues at Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

No significant differences in vaccination rates were noted for children who had used three other categories of nonconventional care: biologically based therapies (such as herbal supplements), mind-body therapies (such as yoga), and multivitamins.

“There is an opportunity for U.S. public health, policy, and conventional medical professionals and educators to improve vaccine uptake and child health by better engaging both CAM and conventional medicine practitioners-in-training, parents of children using particular domains of CAM, and the CAM practitioners advising them,” the researchers said.

Find the full article in Pediatrics (2016. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4664).

What Makes Feedback Productive?

When my youngest daughter returns home from acting or dancing rehearsals, she talks about “notes” that she or the company received that day. Discussing them with her, I appreciate that giving notes to performers after rehearsal or even after a show is standard theater practice. The notes may be from the assistant stage director commenting on lines that were missed, mangled, or perfected. They also could be from the director concerning stage position or behaviors, or they may be about character development or a clarification about the emotions in a particular scene. They are written out as specific references to a certain line or segment of the script. Some directors write them on sticky memos so that they can actually be added to the actor’s script. Others keep their notes on index cards that can be sorted and handed out to the designated performer. My daughter works hard during the first part of the rehearsal process to get as few notes as possible, but at the end of the rehearsal process or during the run of the show, she likes getting notes as a reflection of how she is being perceived and to facilitate fine-tuning her performance.

Giving written notes in our offices to our colleagues, trainees, and staff after a day’s work is not likely to be productive; however, there are parts of this process that dermatologists can utilize. The notes give feedback that is timely and specific. They can be given to individuals or to the entire troupe. I also noticed that my daughter appeared to have a positive relationship with the note givers and looked for their feedback to improve her performance. When residents are on a procedural rotation with me, I endeavor to give them feedback every day about some part of their surgical technique to help them finesse their skills. I am not, however, as rigorous about giving feedback concerning other aspects of the practice, and so this editorial serves the purpose of reminding me that giving feedback is an important skill that we can and should use on a daily basis.

There are many guides for giving feedback. The Center for Creative Leadership developed a feedback technique called Situation-Behavior-Impact (S-B-I).1 Similar to performance notes, it is simple, direct, and timely. Step 1: Capture the situation (S). Step 2: Describe the behavior (B). Step 3: Deliver the impact (I). For example, I have given the following feedback to many fellows when they are working with the resident: (S) “This morning when you two were finishing the repair, (B) you were talking about the lack of efficiency of the clinic in another hospital. (I) It made me uncomfortable because I believe the patient is the center of attention, and yet this was not a conversation that included him. I also worried that he would become nervous or anxious to hear about problems in a medical facility.” Another conversation could go: (S) “This morning with the patient with the eyelid tumor, (B) you told the patient that you would send the eye surgeon a photo so she could be prepared for the repair, and (I) I noticed the patient’s hands immediately relaxed.”

These are straightforward examples. There are more complicated situations that seem to require longer analysis; however, if we acquire the habit of immediate and specific feedback, there will be less need for more difficult conversations. Situation-Behavior-Impact is about behavior; it is not judgmental of the person, and it leaves room for the recipient to think about what happened without being defensive and to take action to create productive behaviors and improve performance. The Center for Creative Leadership recommends that feedback be framed as an observation, which further diminishes the development of a defensive rejection of the information.1

Feedback is such an important loop for all of us professionally and personally because it is the mechanism that gives us the opportunity to improve our performance, so why don’t we always hear it in a constructive thought-provoking way? Stone and Heen2 point out 3 triggers that escalate rejection of feedback: truth, relationship, and identity. They also can be described as immediate reactions: “You are wrong about your assessment,” “I don’t like you anyway,” and “You’re messing with who I am.” For those of you who want to up your game in any of your professional or personal arenas, Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well2 will open you up to seek out and take in feedback. Feedback-seeking behavior has been linked to higher job satisfaction, greater creativity on the job, and faster adaptation to change, while negative feedback has been linked to improved job performance.3 Interestingly, it also helps in our personal lives; a husband’s openness to influence and

In an effort to decrease resistance to hearing feedback, there are proponents of the sandwich technique in which a positive comment is made, then the negative feedback is given, followed by another positive comment. In my experience, this technique does not work. First, you have to give some thought to the appropriate items to bring to the discussion, so the conversation might be delayed long enough to obscure the memory of the details involved in the situations. Second, if you employ it often, the receiver tenses up with the first positive comment, knowing a negative comment will ensue, and so he/she is primed to reject the feedback before it is even offered. Finally, it confuses the priorities for the conversation. However, working over time to give more positive feedback than negative feedback (an average of 4–5 to 1) allows for the development of trust and mutual respect and quiets the urge to immediately reject the negative messages. In my experience, positive feedback is especially effective in creating engagement as well as validating and promoting desirable behaviors. Physicians may have to work deliberately to offer positive feedback because it is more natural for us to diagnose problems than to identify good health.

What impresses me most about the theater culture surrounding notes is that giving and receiving feedback is an expected element of the artistic process. As practitioners, wouldn’t we as well as our patients benefit if the culture of medicine also expected that we were giving each other feedback on a daily basis?

- Weitzel SR. Feedback That Works: How to Build and Deliver Your Message. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership; 2000.

- Stone D, Heen S. Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2015:16-30.

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behavior: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47:232-241.

- Carrère S, Buehlman KT, Gottman JM, et al. Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. J Fam Psychol. 2000;14:42-58.

When my youngest daughter returns home from acting or dancing rehearsals, she talks about “notes” that she or the company received that day. Discussing them with her, I appreciate that giving notes to performers after rehearsal or even after a show is standard theater practice. The notes may be from the assistant stage director commenting on lines that were missed, mangled, or perfected. They also could be from the director concerning stage position or behaviors, or they may be about character development or a clarification about the emotions in a particular scene. They are written out as specific references to a certain line or segment of the script. Some directors write them on sticky memos so that they can actually be added to the actor’s script. Others keep their notes on index cards that can be sorted and handed out to the designated performer. My daughter works hard during the first part of the rehearsal process to get as few notes as possible, but at the end of the rehearsal process or during the run of the show, she likes getting notes as a reflection of how she is being perceived and to facilitate fine-tuning her performance.

Giving written notes in our offices to our colleagues, trainees, and staff after a day’s work is not likely to be productive; however, there are parts of this process that dermatologists can utilize. The notes give feedback that is timely and specific. They can be given to individuals or to the entire troupe. I also noticed that my daughter appeared to have a positive relationship with the note givers and looked for their feedback to improve her performance. When residents are on a procedural rotation with me, I endeavor to give them feedback every day about some part of their surgical technique to help them finesse their skills. I am not, however, as rigorous about giving feedback concerning other aspects of the practice, and so this editorial serves the purpose of reminding me that giving feedback is an important skill that we can and should use on a daily basis.

There are many guides for giving feedback. The Center for Creative Leadership developed a feedback technique called Situation-Behavior-Impact (S-B-I).1 Similar to performance notes, it is simple, direct, and timely. Step 1: Capture the situation (S). Step 2: Describe the behavior (B). Step 3: Deliver the impact (I). For example, I have given the following feedback to many fellows when they are working with the resident: (S) “This morning when you two were finishing the repair, (B) you were talking about the lack of efficiency of the clinic in another hospital. (I) It made me uncomfortable because I believe the patient is the center of attention, and yet this was not a conversation that included him. I also worried that he would become nervous or anxious to hear about problems in a medical facility.” Another conversation could go: (S) “This morning with the patient with the eyelid tumor, (B) you told the patient that you would send the eye surgeon a photo so she could be prepared for the repair, and (I) I noticed the patient’s hands immediately relaxed.”

These are straightforward examples. There are more complicated situations that seem to require longer analysis; however, if we acquire the habit of immediate and specific feedback, there will be less need for more difficult conversations. Situation-Behavior-Impact is about behavior; it is not judgmental of the person, and it leaves room for the recipient to think about what happened without being defensive and to take action to create productive behaviors and improve performance. The Center for Creative Leadership recommends that feedback be framed as an observation, which further diminishes the development of a defensive rejection of the information.1

Feedback is such an important loop for all of us professionally and personally because it is the mechanism that gives us the opportunity to improve our performance, so why don’t we always hear it in a constructive thought-provoking way? Stone and Heen2 point out 3 triggers that escalate rejection of feedback: truth, relationship, and identity. They also can be described as immediate reactions: “You are wrong about your assessment,” “I don’t like you anyway,” and “You’re messing with who I am.” For those of you who want to up your game in any of your professional or personal arenas, Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well2 will open you up to seek out and take in feedback. Feedback-seeking behavior has been linked to higher job satisfaction, greater creativity on the job, and faster adaptation to change, while negative feedback has been linked to improved job performance.3 Interestingly, it also helps in our personal lives; a husband’s openness to influence and

In an effort to decrease resistance to hearing feedback, there are proponents of the sandwich technique in which a positive comment is made, then the negative feedback is given, followed by another positive comment. In my experience, this technique does not work. First, you have to give some thought to the appropriate items to bring to the discussion, so the conversation might be delayed long enough to obscure the memory of the details involved in the situations. Second, if you employ it often, the receiver tenses up with the first positive comment, knowing a negative comment will ensue, and so he/she is primed to reject the feedback before it is even offered. Finally, it confuses the priorities for the conversation. However, working over time to give more positive feedback than negative feedback (an average of 4–5 to 1) allows for the development of trust and mutual respect and quiets the urge to immediately reject the negative messages. In my experience, positive feedback is especially effective in creating engagement as well as validating and promoting desirable behaviors. Physicians may have to work deliberately to offer positive feedback because it is more natural for us to diagnose problems than to identify good health.

What impresses me most about the theater culture surrounding notes is that giving and receiving feedback is an expected element of the artistic process. As practitioners, wouldn’t we as well as our patients benefit if the culture of medicine also expected that we were giving each other feedback on a daily basis?

When my youngest daughter returns home from acting or dancing rehearsals, she talks about “notes” that she or the company received that day. Discussing them with her, I appreciate that giving notes to performers after rehearsal or even after a show is standard theater practice. The notes may be from the assistant stage director commenting on lines that were missed, mangled, or perfected. They also could be from the director concerning stage position or behaviors, or they may be about character development or a clarification about the emotions in a particular scene. They are written out as specific references to a certain line or segment of the script. Some directors write them on sticky memos so that they can actually be added to the actor’s script. Others keep their notes on index cards that can be sorted and handed out to the designated performer. My daughter works hard during the first part of the rehearsal process to get as few notes as possible, but at the end of the rehearsal process or during the run of the show, she likes getting notes as a reflection of how she is being perceived and to facilitate fine-tuning her performance.

Giving written notes in our offices to our colleagues, trainees, and staff after a day’s work is not likely to be productive; however, there are parts of this process that dermatologists can utilize. The notes give feedback that is timely and specific. They can be given to individuals or to the entire troupe. I also noticed that my daughter appeared to have a positive relationship with the note givers and looked for their feedback to improve her performance. When residents are on a procedural rotation with me, I endeavor to give them feedback every day about some part of their surgical technique to help them finesse their skills. I am not, however, as rigorous about giving feedback concerning other aspects of the practice, and so this editorial serves the purpose of reminding me that giving feedback is an important skill that we can and should use on a daily basis.

There are many guides for giving feedback. The Center for Creative Leadership developed a feedback technique called Situation-Behavior-Impact (S-B-I).1 Similar to performance notes, it is simple, direct, and timely. Step 1: Capture the situation (S). Step 2: Describe the behavior (B). Step 3: Deliver the impact (I). For example, I have given the following feedback to many fellows when they are working with the resident: (S) “This morning when you two were finishing the repair, (B) you were talking about the lack of efficiency of the clinic in another hospital. (I) It made me uncomfortable because I believe the patient is the center of attention, and yet this was not a conversation that included him. I also worried that he would become nervous or anxious to hear about problems in a medical facility.” Another conversation could go: (S) “This morning with the patient with the eyelid tumor, (B) you told the patient that you would send the eye surgeon a photo so she could be prepared for the repair, and (I) I noticed the patient’s hands immediately relaxed.”

These are straightforward examples. There are more complicated situations that seem to require longer analysis; however, if we acquire the habit of immediate and specific feedback, there will be less need for more difficult conversations. Situation-Behavior-Impact is about behavior; it is not judgmental of the person, and it leaves room for the recipient to think about what happened without being defensive and to take action to create productive behaviors and improve performance. The Center for Creative Leadership recommends that feedback be framed as an observation, which further diminishes the development of a defensive rejection of the information.1

Feedback is such an important loop for all of us professionally and personally because it is the mechanism that gives us the opportunity to improve our performance, so why don’t we always hear it in a constructive thought-provoking way? Stone and Heen2 point out 3 triggers that escalate rejection of feedback: truth, relationship, and identity. They also can be described as immediate reactions: “You are wrong about your assessment,” “I don’t like you anyway,” and “You’re messing with who I am.” For those of you who want to up your game in any of your professional or personal arenas, Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well2 will open you up to seek out and take in feedback. Feedback-seeking behavior has been linked to higher job satisfaction, greater creativity on the job, and faster adaptation to change, while negative feedback has been linked to improved job performance.3 Interestingly, it also helps in our personal lives; a husband’s openness to influence and

In an effort to decrease resistance to hearing feedback, there are proponents of the sandwich technique in which a positive comment is made, then the negative feedback is given, followed by another positive comment. In my experience, this technique does not work. First, you have to give some thought to the appropriate items to bring to the discussion, so the conversation might be delayed long enough to obscure the memory of the details involved in the situations. Second, if you employ it often, the receiver tenses up with the first positive comment, knowing a negative comment will ensue, and so he/she is primed to reject the feedback before it is even offered. Finally, it confuses the priorities for the conversation. However, working over time to give more positive feedback than negative feedback (an average of 4–5 to 1) allows for the development of trust and mutual respect and quiets the urge to immediately reject the negative messages. In my experience, positive feedback is especially effective in creating engagement as well as validating and promoting desirable behaviors. Physicians may have to work deliberately to offer positive feedback because it is more natural for us to diagnose problems than to identify good health.

What impresses me most about the theater culture surrounding notes is that giving and receiving feedback is an expected element of the artistic process. As practitioners, wouldn’t we as well as our patients benefit if the culture of medicine also expected that we were giving each other feedback on a daily basis?

- Weitzel SR. Feedback That Works: How to Build and Deliver Your Message. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership; 2000.

- Stone D, Heen S. Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2015:16-30.

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behavior: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47:232-241.

- Carrère S, Buehlman KT, Gottman JM, et al. Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. J Fam Psychol. 2000;14:42-58.

- Weitzel SR. Feedback That Works: How to Build and Deliver Your Message. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership; 2000.

- Stone D, Heen S. Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2015:16-30.

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behavior: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47:232-241.

- Carrère S, Buehlman KT, Gottman JM, et al. Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. J Fam Psychol. 2000;14:42-58.

Walk the Talk: VA Mental Health Care Professionals’ Role in Promoting Physical Activity

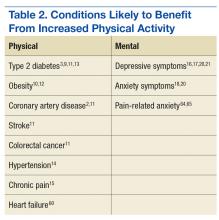

Physical activity is a key determinant of health. Low levels of activity are associated with onset of and poorer outcomes of many chronic health conditions (eg, obesity, coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic pain, hypertension1-4) and with higher rates of mental health conditions (eg, depression, anxiety5-8).

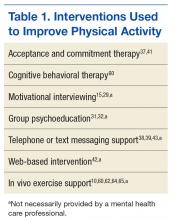

Behavioral interventions (Table 1) can increase activity and improve physical health and mental health (Table 2).9-21 However, only 20% of adults in the U.S. meet federal recommendations for physical activity.22 The situation is particularly grim in the veteran population. Littman and colleagues found that veterans were less likely than nonveterans were to meet physical activity standards, and VA patients were even less likely than were non-VA veterans to meet the recommendations.23

Given that exercise can positively affect physical and mental health and that VA mental health care professionals (MHCPs) have training in motivational enhancement and behavior modification, these clinicians are well positioned to intervene. The question arises, though: How can VA MHCPs do more to effectively promote physical activity in veterans?

Addressing Physical Activity

There are numerous ways in which VA MHCPs can address physical activity with their patients. Several studies have demonstrated that physical activity interventions provided within primary care–mental health integration programs resulted in increased physical activity.28,29 The number of VA health care providers (HCPs) offering such programs is increasing, which could mean that behavioral health support for physical activity promotion could become easier for veterans to access.30

In addition, National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention initiatives have led to an expansion of programs, such as the VA MOVE! Weight Management Program.31 Often cofacilitated by dieticians and MHCPs, MOVE! includes nutrition education, behavior modification, and physical activity promotion.32 Preliminary research suggests that MOVE! helps veterans lose weight and improve their health-related quality of life.33-36

Further, psychological and behavioral interventions can specifically target exercise and have been shown to increase physical activity, improve mood symptoms, and reduce health risk factors.9-21,37 However, little is known about the extent of exercise promotion in VA outpatient mental health services. For instance, some HCPs may educate patients about the benefits of physical activity, while others may facilitate physical activity scheduling, address barriers, and monitor, reinforce, and problem-solve physical activity goals.

Research also has supported the efficacy of technology-based interventions in physical activity promotion by MHCPs. These interventions include phone counseling, text messaging or smartphone application monitoring systems (including the MOVE! Coach mobile app), DVD-based approaches, and web-based interventions.38-42 However, these interventions may be most effective when complemented with face-to-face support (eg, psychotherapy, nutrition/exercise classes).43 Although MHCPs can promote physical activity in various ways, intensive focus on this target is not standard practice in many mental health care settings.

Barriers to Physical Activity

Despite physical activity promotion efforts, patients struggle to implement and maintain physical activity recommendations.22,44,45 For many patients, exercise is a new or long abandoned activity, and instruction on how to exercise properly is needed.46 Lack of financial resources may limit access to a gym, trainer, or physical therapist.47 Some patients avoid exercise because of body image concerns, and many think they lack the self-discipline and time for exercise.46,48,49

Additional barriers to physical activity are pain, fatigue, and other physical symptoms.50-52 Obese patients may find physical activity less enjoyable and more uncomfortable.53 Some patients fear exercise will exacerbate medical problems or have negative physical consequences.51,52

Psychiatric symptoms and medication adverse effects are commonly reported barriers.54 Some patients with anxiety avoid physical activity because the resulting physiologic sensations (eg, rapid heart rate, sweating) are similar to anxiety symptoms.55 Patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are less likely to exercise, secondary to PTSD-related avoidance, even though they were physically active before their trauma.56-58 Some patients with depression avoid exercise and other activities because their symptoms (eg, fatigue, anhedonia) make it difficult for them to take action. Many patients put off exercise while waiting for relief of mental health symptoms, even though evidence suggests that physical activity may help improve those symptoms.5,6

These barriers often render ineffective the approach of simply recommending exercise or encouraging patients to exercise. Counseling alone may not be sufficient to effect meaningful change in exercise habits. Many effective physical activity interventions have both a counseling and exercise components,59-61 and research suggests that such interventions may be most effective when they include a form of experiential exercise.10

Clinician-Assisted Experiential Exercise

Exercise interventions may involve information dissemination, counseling, an experiential exercise program, or a combination of these activities. Research has yet to determine precisely which components are most effective. Given the barriers to adhering to exercise recommendations, however, exercise interventions that include an experiential component may be more likely to affect behavior change.

According to Sime, exercise therapy is the “practice of combining a program of exercise with traditional psychotherapy.”62 Sime outlined a 10-session approach to exercise therapy and suggested that walking with patients while engaging in psychotherapy can reduce barriers to change. This approach may be effective for several reasons. First, it models the recommendation to engage in activity despite not feeling well and often improves mood. Second, the experiential nature of the intervention gives the patient an immediate opportunity to physically feel the benefits of activity. Third, the experiential component is similar to experiential exercise interventions, which have been shown to improve chronic health problems, such as obesity, and it parallels in vivo exposure, which is highly effective in treating anxiety.10,63

Exposure to exercise also has been effective in treating chronic pain in patients who fear physical activity because they anticipate pain or reinjury. In patients with chronic low back pain, in vivo exposure reduced anxiety more than an education-only session did, and the result was improved participation in relevant daily activities.64 Results were sustained at the 6-month follow-up but only for patients who received in vivo exposure.65 Similarly, in vivo exposure to feared movements increased physical activity and reduced pain-related fear, catastrophizing, and disability in patients with chronic low back pain.65 These findings have implications for other chronic health problems. Particularly for patients who fear and avoid exercise, psychoeducation about exercise and opportunities to experience exercise in session may increase physical activity outside of therapy.10

Obstacles to Exercise Promotion

Mental health care providers may be reluctant to use experiential exercise interventions for a variety of reasons. Some fear that they or their patients might sustain an injury or an exacerbation of physical symptoms. In addition, some MHCPs have liability and safety concerns surrounding meetings with patients outside the office. And obtaining medical clearance requires extra time and energy.

Some MHCPs think that this type of experiential activity might cross a professional boundary. Others may wonder whether providing experiential exercise as part of mental health services is sufficiently evidence based or is a breach of standards of practice. Similarly, some MHCPs who use manual-based interventions are hesitant to stray from an evidence-based protocol and include experiential exercise in psychotherapy. Further, some MHCPs do not feel competent to provide such an intervention, given that it is not typically covered in their mental health care training, and they think that providing opportunities for experiential exercise falls outside their MHCP role. Last, some MHCPs are uncomfortable exercising on their own and thus may be particularly uncomfortable exercising in front of patients.

Promoting Physical Activity

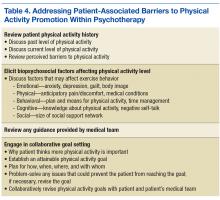

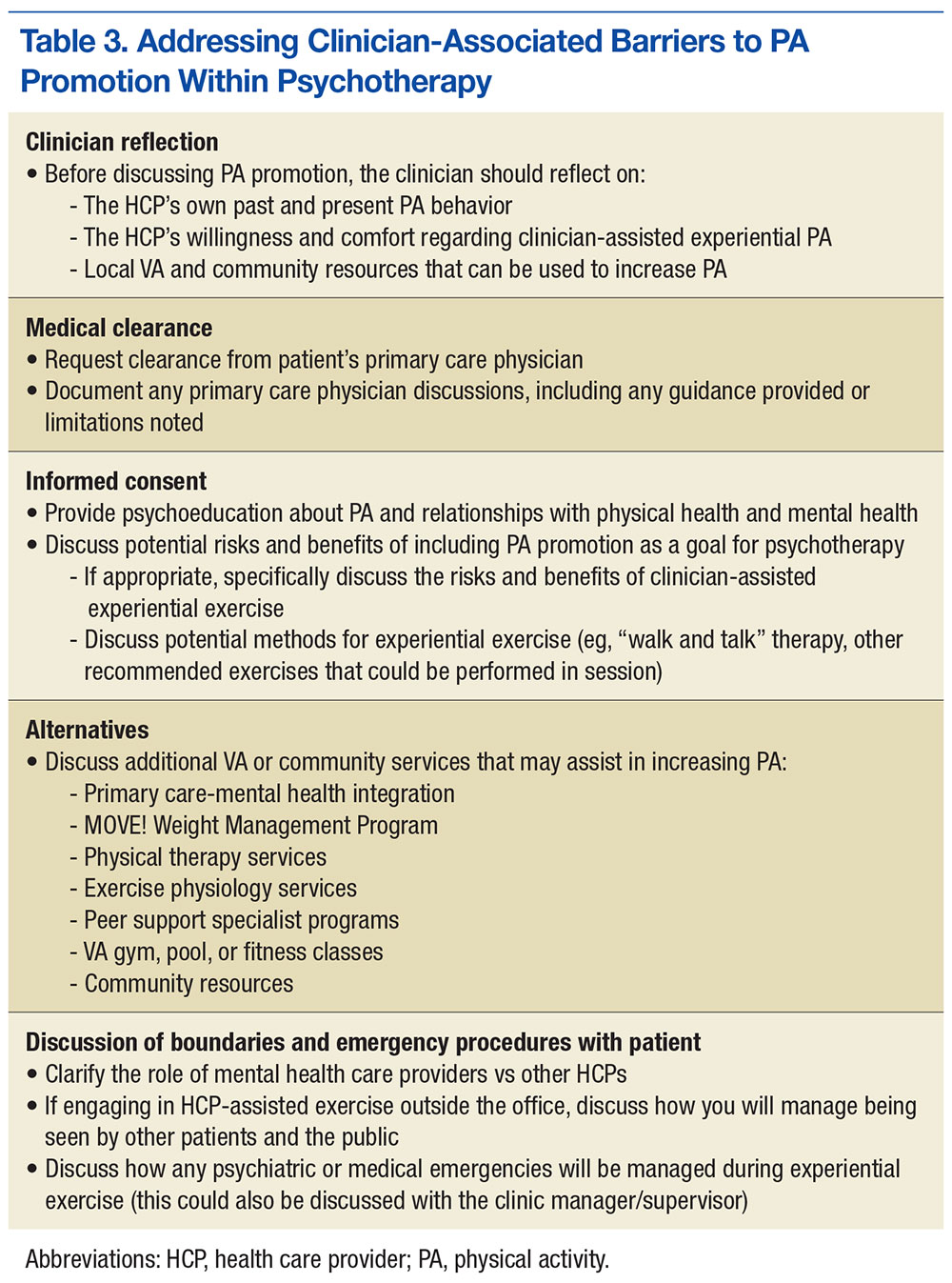

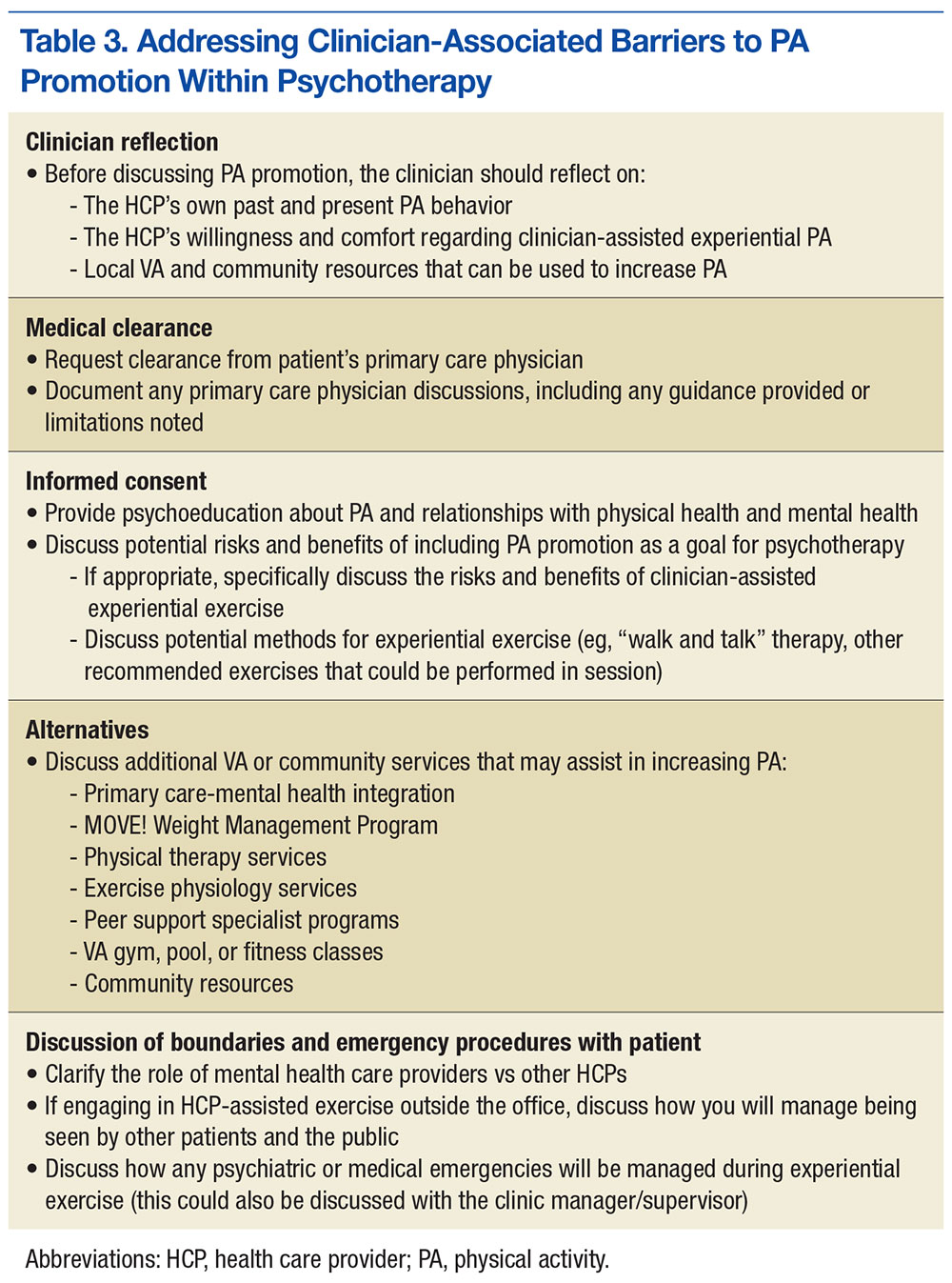

Although significant, barriers to promotion of physical activity can be effectively reduced by taking the steps outlined in Table 3. First, MHCPs must reflect on their own past and present physical activity and on their readiness to provide clinician-assisted experiential exercise. In addition, MHCPs should explore nearby alternative resources for physical activity, share their findings with patients, and encourage patients to use these resources. Next, medical clearance for increased physical activity can be obtained from patients’ primary care physicians, and any physical activity recommendations or limitations can be reviewed and documented. Mental health care providers should then obtain patients’ informed consent, which involves discussing the potential risks and benefits of increased exercise and, if appropriate, collaborate with patients to reach an agreement to focus on physical activity as an important aspect of their work together. Any additional risks and benefits of clinician-assisted experiential exercise can be discussed, and the ways in which physical activity can be used in session (eg, “walk and talk therapy”; other exercises recommended by the medical team) can be reviewed. Further, MHCPs can clarify their role and discuss how clear boundaries will be maintained within the therapeutic relationship. Alternative VA and community services that can help increase physical activity should also be discussed.

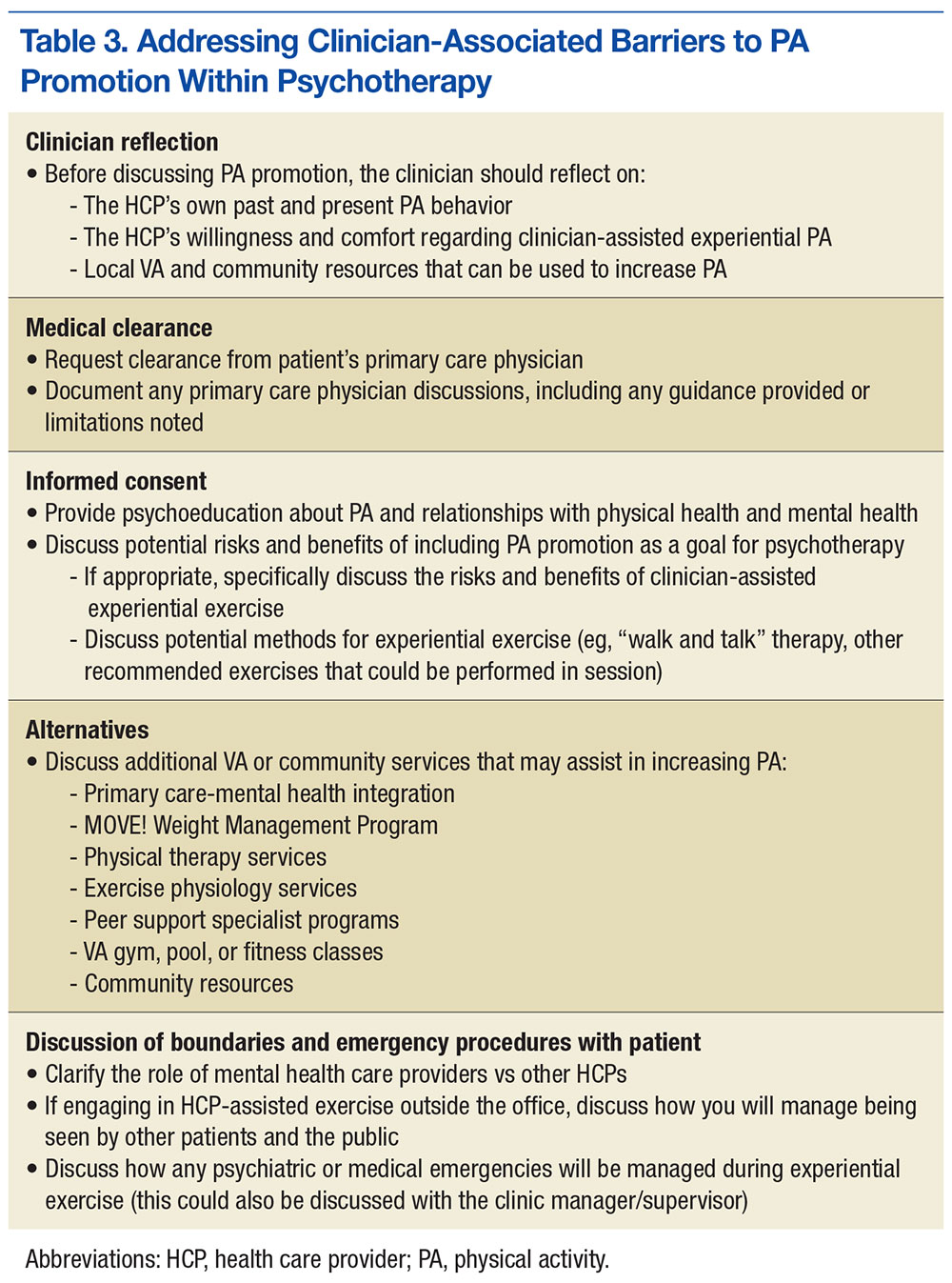

Once these steps are complete, MHCPs can address patient’s barriers to physical activity (Table 4). A discussion of the patient’s physical activity history is a good starting point. Biopsychosocial factors that can affect the ability to engage in and follow through with physical activity can then be explored, and HCPs and patients can set specific attainable physical activity goals. For instance, MHCPs can specify whether in-session clinic-assisted experiential exercise will be used and, if so, in what capacity. Last, physical activity goals can be revised periodically and revisited with the medical team.

Alternate Promotions

Mental health care providers also should consider involving other HCPs. Physical therapists and exercise physiologists are in a unique position to provide experiential exercise training. Some VA facilities include experiential exercise in their MOVE! program—veterans exercise together in the VA’s physical therapy gym while being monitored by a physical therapist.

Peer support specialists (PSPs) also are in a unique position to effectively provide experiential physical activity interventions at VA facilities. These PSPs are veterans who have physical or mental health problems but are far enough along in recovery to provide helpful services to other veterans with similar challenges.66 Recent organizational efforts have increased the presence of PSPs in VA clinics. Peer support specialists use aspects of their recovery to help other veterans, provide supportive counseling, and facilitate activity groups, such as walking, hiking, golfing, and photography groups. Further, PSPs may not have to deal with MHCPs’ concerns regarding scope of practice and clinical boundaries vis-à-vis exercise interventions.

Other VA and community programs provide ways for veterans to engage in experiential physical activities. Some VA facilities have pools and gyms that provide open hours for veterans; some even offer free HCP guidance. Clinics also occasionally provide transportation to community gyms that offer veterans discounted memberships. Team Red, White, and Blue (https://www.teamrwb.org), Veterans Expeditions, (http://www.vetexpeditions.com) and other community organizations promote veterans’ physical activity by organizing events, such as endurance races, fly fishing, and mountaineering. By staying up-to-date on local community services, MHCPs can facilitate opportunities for experiential exercise alongside the psychotherapy services they provide.

Although valuable resources exist, veterans nevertheless encounter obstacles to exercise. For instance, many VA HCPs do not include physical therapy as a standard part of the MOVE! program. Others offer physical therapy not as an integrated service but as a separate, optional service, and attendance requires more initiative. Often, veterans are referred for physical therapy only if they have sustained an injury. Even when physical therapy or exercise physiology services are offered, many veterans have difficulty following through. Reasons include anxiety, time constraints, difficulty managing multiple appointments, and negative beliefs about exercise and physical therapy (eg, it will make me hurt, physical therapy is only for people recovering from an injury). Last, some veterans are reluctant to engage in peer-led or non-VA exercise programs.

Future Research