User login

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Self-tanners

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on self-tanners. Consideration must be given to:

- Anthelios 50 Mineral Tinted

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- St. Tropez Self Tan products

PZ Cussons Beauty LLP

“It helps to produce an even and natural-looking skin tone.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Sun-Free Self-Tanning Formula

Kiehl’s

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Sunless Tanning Towelette

Sun Bum

“This product is easy to use. Make sure to use it in conjunction with a broad-spectrum sunscreen.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, skin-lightening products, and athlete’s foot treatments will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on self-tanners. Consideration must be given to:

- Anthelios 50 Mineral Tinted

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- St. Tropez Self Tan products

PZ Cussons Beauty LLP

“It helps to produce an even and natural-looking skin tone.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Sun-Free Self-Tanning Formula

Kiehl’s

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Sunless Tanning Towelette

Sun Bum

“This product is easy to use. Make sure to use it in conjunction with a broad-spectrum sunscreen.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, skin-lightening products, and athlete’s foot treatments will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on self-tanners. Consideration must be given to:

- Anthelios 50 Mineral Tinted

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- St. Tropez Self Tan products

PZ Cussons Beauty LLP

“It helps to produce an even and natural-looking skin tone.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Sun-Free Self-Tanning Formula

Kiehl’s

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Sunless Tanning Towelette

Sun Bum

“This product is easy to use. Make sure to use it in conjunction with a broad-spectrum sunscreen.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, skin-lightening products, and athlete’s foot treatments will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Sonovaginography bests negative ‘sliding sign’ in predicting deep infiltrating endometriosis

ORLANDO – Direct visualization with sonovaginography had greater success in predicting rectal/rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis than did negative transvaginal ultrasound uterine “sliding sign,” according to the findings of a prospective study of 189 women.

“Both performed quite well,” but sonovaginography was superior for predicting rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis on all measures, including accuracy – 92% vs. 88%, said Bassem Gerges, MBBS, an ob.gyn. at the University of Sydney, Kingswood.

Dr. Gerges and his colleagues evaluated 189 women of reproductive age who were scheduled for operative laparoscopy at a tertiary referral center for women. The patients had a history of chronic pelvic pain and/or endometriosis and presented between 2009 and 2013.

The women first had transvaginal ultrasound to determine if their uterine sliding sign was positive or negative, followed by sonovaginography to assess the posterior pelvic compartment for rectal or rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis. All patients then underwent laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis.

Laparoscopy revealed pouch of Douglas obliteration in 47 of the 189 women and rectal and/or rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis in 43 women.

The sensitivity of sonovaginography to predict deep infiltrating endometriosis was 88%, compared with 74% for the sliding-sign approach. Specificity was the same with the two methods at 93%. The positive predictive value was 79% vs. 74%, respectively, and the negative predictive value was 97% vs. 93%.

“These findings can help clinicians with preoperative planning,” Dr. Gerges said at the meeting, which was sponsored by AAGL.

Dr. Gerges and his colleagues also identified 11 false-negative cases in which the sliding sign was positive but laparoscopy confirmed rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis.

Previous research suggests that, in women with suspected endometriosis, a negative transvaginal ultrasound uterine sliding sign can predict rectal or rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41[6]:692-5, J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:315-21). A negative sliding sign indicates the presence of uterorectal adhesions and whether the pouch of Douglas might be obliterated. The current study, however, suggested that sonovaginography might be the better method.

Dr. Gerges reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Direct visualization with sonovaginography had greater success in predicting rectal/rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis than did negative transvaginal ultrasound uterine “sliding sign,” according to the findings of a prospective study of 189 women.

“Both performed quite well,” but sonovaginography was superior for predicting rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis on all measures, including accuracy – 92% vs. 88%, said Bassem Gerges, MBBS, an ob.gyn. at the University of Sydney, Kingswood.

Dr. Gerges and his colleagues evaluated 189 women of reproductive age who were scheduled for operative laparoscopy at a tertiary referral center for women. The patients had a history of chronic pelvic pain and/or endometriosis and presented between 2009 and 2013.

The women first had transvaginal ultrasound to determine if their uterine sliding sign was positive or negative, followed by sonovaginography to assess the posterior pelvic compartment for rectal or rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis. All patients then underwent laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis.

Laparoscopy revealed pouch of Douglas obliteration in 47 of the 189 women and rectal and/or rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis in 43 women.

The sensitivity of sonovaginography to predict deep infiltrating endometriosis was 88%, compared with 74% for the sliding-sign approach. Specificity was the same with the two methods at 93%. The positive predictive value was 79% vs. 74%, respectively, and the negative predictive value was 97% vs. 93%.

“These findings can help clinicians with preoperative planning,” Dr. Gerges said at the meeting, which was sponsored by AAGL.

Dr. Gerges and his colleagues also identified 11 false-negative cases in which the sliding sign was positive but laparoscopy confirmed rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis.

Previous research suggests that, in women with suspected endometriosis, a negative transvaginal ultrasound uterine sliding sign can predict rectal or rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41[6]:692-5, J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:315-21). A negative sliding sign indicates the presence of uterorectal adhesions and whether the pouch of Douglas might be obliterated. The current study, however, suggested that sonovaginography might be the better method.

Dr. Gerges reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Direct visualization with sonovaginography had greater success in predicting rectal/rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis than did negative transvaginal ultrasound uterine “sliding sign,” according to the findings of a prospective study of 189 women.

“Both performed quite well,” but sonovaginography was superior for predicting rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis on all measures, including accuracy – 92% vs. 88%, said Bassem Gerges, MBBS, an ob.gyn. at the University of Sydney, Kingswood.

Dr. Gerges and his colleagues evaluated 189 women of reproductive age who were scheduled for operative laparoscopy at a tertiary referral center for women. The patients had a history of chronic pelvic pain and/or endometriosis and presented between 2009 and 2013.

The women first had transvaginal ultrasound to determine if their uterine sliding sign was positive or negative, followed by sonovaginography to assess the posterior pelvic compartment for rectal or rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis. All patients then underwent laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis.

Laparoscopy revealed pouch of Douglas obliteration in 47 of the 189 women and rectal and/or rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis in 43 women.

The sensitivity of sonovaginography to predict deep infiltrating endometriosis was 88%, compared with 74% for the sliding-sign approach. Specificity was the same with the two methods at 93%. The positive predictive value was 79% vs. 74%, respectively, and the negative predictive value was 97% vs. 93%.

“These findings can help clinicians with preoperative planning,” Dr. Gerges said at the meeting, which was sponsored by AAGL.

Dr. Gerges and his colleagues also identified 11 false-negative cases in which the sliding sign was positive but laparoscopy confirmed rectal deep infiltrating endometriosis.

Previous research suggests that, in women with suspected endometriosis, a negative transvaginal ultrasound uterine sliding sign can predict rectal or rectosigmoid deep infiltrating endometriosis (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41[6]:692-5, J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:315-21). A negative sliding sign indicates the presence of uterorectal adhesions and whether the pouch of Douglas might be obliterated. The current study, however, suggested that sonovaginography might be the better method.

Dr. Gerges reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Plasma energy ablation yields pregnancy rates similar to cystectomy

ORLANDO – The first study to directly compare plasma energy treatment of ovarian endometriomas to cystectomy demonstrates similar postintervention pregnancy rates, suggesting that plasma energy ablation may be a comparable treatment option.

Researchers evaluated 104 women seeking pregnancy after 1 year or more of infertility. Women presented with unilateral or bilateral ovarian endometriomas larger than 3 cm between January 2009 and June 2014. Clinicians treated 64 patients with plasma energy ablation and another 40 with cystectomy and followed them to compare pregnancy rates.

After at least 1 year of follow-up, pregnancy rates were 68% following plasma energy ablation, compared with 80% after cystectomy. Of the 76 pregnancies, 24 were due to spontaneous conception, including 40% of pregnancies in the plasma energy group and 18% in the cystectomy group. Even after adjustment for multiple factors, the type of intervention had no statistically significant impact on achieving a subsequent pregnancy.

“Ablation using plasma energy may be considered a valuable tool that allows a high pregnancy rate,” Basma Darwish, MD, an ob.gyn. at Rouen (France) University Hospital, said at the meeting, which was sponsored by AAGL.

These similar outcomes were observed despite a higher prevalence of risk predictors for infertility in the plasma energy group at baseline. For instance, women in this cohort were significantly older and had significantly higher revised American Fertility Society (rAFS) classification scores, as well as higher rates of pouch of Douglas obliteration, deep endometriosis, and colorectal localizations.

“Endometrial ablation using plasma energy allows good postoperative [pregnancy] rates, that is well known,” Dr. Darwish said, but the technique has not been directly compared with cystectomy outcomes.

Pregnancy rates remained similar in both groups at 24 and 36 months. The probability of pregnancy was 61% in the plasma energy group versus 69% in the cystectomy group at 24 months. At 36 months, these rates changed to 84% and 78%, respectively.

A unique property of plasma energy ablation is “very limited thermal spread, both in depth and laterally,” Dr. Darwish said.

A lack of randomization is a potential limitation of the study. “Each surgeon chose the technique he or she was best at, which may have explained our good outcomes.” Dr. Darwish said. Strengths of the study include a prospective design and follow-up to 5 years. In addition, the six centers involved in the study included both private and public hospitals, “so it’s a good reflection of what happens in real life.”

The investigators plan to conduct a randomized controlled trial to confirm these findings.

ORLANDO – The first study to directly compare plasma energy treatment of ovarian endometriomas to cystectomy demonstrates similar postintervention pregnancy rates, suggesting that plasma energy ablation may be a comparable treatment option.

Researchers evaluated 104 women seeking pregnancy after 1 year or more of infertility. Women presented with unilateral or bilateral ovarian endometriomas larger than 3 cm between January 2009 and June 2014. Clinicians treated 64 patients with plasma energy ablation and another 40 with cystectomy and followed them to compare pregnancy rates.

After at least 1 year of follow-up, pregnancy rates were 68% following plasma energy ablation, compared with 80% after cystectomy. Of the 76 pregnancies, 24 were due to spontaneous conception, including 40% of pregnancies in the plasma energy group and 18% in the cystectomy group. Even after adjustment for multiple factors, the type of intervention had no statistically significant impact on achieving a subsequent pregnancy.

“Ablation using plasma energy may be considered a valuable tool that allows a high pregnancy rate,” Basma Darwish, MD, an ob.gyn. at Rouen (France) University Hospital, said at the meeting, which was sponsored by AAGL.

These similar outcomes were observed despite a higher prevalence of risk predictors for infertility in the plasma energy group at baseline. For instance, women in this cohort were significantly older and had significantly higher revised American Fertility Society (rAFS) classification scores, as well as higher rates of pouch of Douglas obliteration, deep endometriosis, and colorectal localizations.

“Endometrial ablation using plasma energy allows good postoperative [pregnancy] rates, that is well known,” Dr. Darwish said, but the technique has not been directly compared with cystectomy outcomes.

Pregnancy rates remained similar in both groups at 24 and 36 months. The probability of pregnancy was 61% in the plasma energy group versus 69% in the cystectomy group at 24 months. At 36 months, these rates changed to 84% and 78%, respectively.

A unique property of plasma energy ablation is “very limited thermal spread, both in depth and laterally,” Dr. Darwish said.

A lack of randomization is a potential limitation of the study. “Each surgeon chose the technique he or she was best at, which may have explained our good outcomes.” Dr. Darwish said. Strengths of the study include a prospective design and follow-up to 5 years. In addition, the six centers involved in the study included both private and public hospitals, “so it’s a good reflection of what happens in real life.”

The investigators plan to conduct a randomized controlled trial to confirm these findings.

ORLANDO – The first study to directly compare plasma energy treatment of ovarian endometriomas to cystectomy demonstrates similar postintervention pregnancy rates, suggesting that plasma energy ablation may be a comparable treatment option.

Researchers evaluated 104 women seeking pregnancy after 1 year or more of infertility. Women presented with unilateral or bilateral ovarian endometriomas larger than 3 cm between January 2009 and June 2014. Clinicians treated 64 patients with plasma energy ablation and another 40 with cystectomy and followed them to compare pregnancy rates.

After at least 1 year of follow-up, pregnancy rates were 68% following plasma energy ablation, compared with 80% after cystectomy. Of the 76 pregnancies, 24 were due to spontaneous conception, including 40% of pregnancies in the plasma energy group and 18% in the cystectomy group. Even after adjustment for multiple factors, the type of intervention had no statistically significant impact on achieving a subsequent pregnancy.

“Ablation using plasma energy may be considered a valuable tool that allows a high pregnancy rate,” Basma Darwish, MD, an ob.gyn. at Rouen (France) University Hospital, said at the meeting, which was sponsored by AAGL.

These similar outcomes were observed despite a higher prevalence of risk predictors for infertility in the plasma energy group at baseline. For instance, women in this cohort were significantly older and had significantly higher revised American Fertility Society (rAFS) classification scores, as well as higher rates of pouch of Douglas obliteration, deep endometriosis, and colorectal localizations.

“Endometrial ablation using plasma energy allows good postoperative [pregnancy] rates, that is well known,” Dr. Darwish said, but the technique has not been directly compared with cystectomy outcomes.

Pregnancy rates remained similar in both groups at 24 and 36 months. The probability of pregnancy was 61% in the plasma energy group versus 69% in the cystectomy group at 24 months. At 36 months, these rates changed to 84% and 78%, respectively.

A unique property of plasma energy ablation is “very limited thermal spread, both in depth and laterally,” Dr. Darwish said.

A lack of randomization is a potential limitation of the study. “Each surgeon chose the technique he or she was best at, which may have explained our good outcomes.” Dr. Darwish said. Strengths of the study include a prospective design and follow-up to 5 years. In addition, the six centers involved in the study included both private and public hospitals, “so it’s a good reflection of what happens in real life.”

The investigators plan to conduct a randomized controlled trial to confirm these findings.

AT THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

An Update on Management of Syndesmosis Injury: A National US Database Study

Acute ankle injuries are common problems treated by orthopedic surgeons. In the United States, nearly 2 million ankle sprains occur each year,1 and ankle fractures account for 9% to 18% of all fractures treated in emergency departments.2,3 Ankle injuries that involve the syndesmotic ligaments may result in instability and require specific treatment beyond fixation of the malleolar fractures.

The usual mechanism of syndesmotic injury is external rotation of the ankle with hyperdorsiflexion of a pronated or supinated foot.4,5 Syndesmotic injuries are estimated to occur in up to 10% of ankle sprains6 and up to 23% of all ankle fractures.7 Overall US incidence of syndesmotic injury is estimated at 6445 injuries per year.8 Syndesmotic injury occurs in 39% to 45% of supination-external rotation IV ankle fractures.9,10 Pronation-external rotation ankle fractures have the highest rate of syndesmotic injury. Syndesmotic injury may be less common in other types of malleolar fracture, but the exact incidence has not been reliably reported.

Traditionally, isolated nondisplaced syndesmotic injuries are treated nonoperatively, and syndesmotic injuries with concomitant malleolar fractures are treated surgically. Various options are available for syndesmotic fixation. The gold standard is syndesmotic screw placement from the lateral aspect of the fibula through the tibia. Fixation may be achieved with screws in a variety of configurations and formats. However, fixation with two 4.5-mm screws is stronger.11,12 Functional outcomes are similar, regardless of screw material,13-16 number of cortices,17 or number of screws.18 Disadvantages specific to screw fixation include altered ankle biomechanics,19,20 potential for screw breakage,21 and need for implant removal.3Alternatively, suture button fixation is said to be equally as effective as screw fixation in achieving syndesmotic reduction, and their functional outcomes are similar.22,23 The initial cost of suture button fixation is higher than that of screw fixation, but the difference may be offset by potential elimination of a second surgery for syndesmotic screw removal.24 Soft-tissue irritation caused by the suture material and local osteolysis are reported complications of suture button fixation.25-27

Regardless of fixation method used, achieving anatomical reduction of the syndesmosis is considered the most important factor in optimizing functional outcomes.28-31 However, achieving and verifying anatomical reduction of the syndesmosis during surgery can be quite challenging.30,32-34 Various methods of lowering the malreduction risk, including direct visualization of the tibiofibular joint during reduction30,35 and intraoperative 3-dimensional imaging,33,36 have been proposed.

In the study reported here, we used a US insurance database to determine the incidence and rate of syndesmotic stabilization within various ankle injuries and fracture patterns.

Materials and Methods

All data for this study were obtained from a publicly available for-fee healthcare database, the PearlDiver Patient Records Database, which includes procedural volumes and demographic information for patients with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses and procedures or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Data for the study were derived from 2 databases within PearlDiver: a private-payer database, which has its largest contribution (>30 million individual patient records for 2007-2011) from United HealthCare, and a Medicare database (>50 million patient records for 2007-2011). Access to the database was granted by PearlDiver Technologies for the purpose of academic research. The database was stored on a password-protected server maintained by PearlDiver.

We searched the database for cases of ankle fracture fixation, including fixation of isolated lateral malleolus (CPT 27792), bimalleolar (CPT 27814), and trimalleolar (CPTs 27822 and 27823) fractures. CPT 27829 was used to search for syndesmotic fixation, and CPT 20680 for implant removal. These codes were used individually and in combination.

Overall procedural volume data are reported as number of patients with the given CPT(s) in the database output and as incidence, calculated as number of patients with the CPT of interest normalized to total number of patients in the database for that particular subgroup. Results of age group and sex analyses are reported as number of patients reported in the database output and as percentage of patients who had the CPT procedure of interest that year. As United HealthCare is the largest contributor to the private-payer portion of the database and is represented most prominently in the southern region, data for the regional analysis are presented only as incidence. This incidence was calculated as number of patients in a particular region and year normalized to total number of patients in the database for that region or year. The regions were Midwest (IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI), Northeast (CT, MA, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT), South (AL, AR, DC, DE, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MI, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV), and West (AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NM, NV, OR, UT, WA, WY).

Chi-square linear-by-linear association analysis was used to determine the statistical significance of time trends in procedural volume, sex, age group, and region. For all statistical comparisons, P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

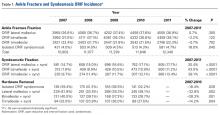

Number of open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) procedures increased for all ankle fracture types over the period 2007 to 2011 (Table 1).

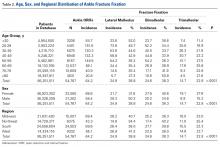

ORIF was performed for an ankle injury in 54,767 patients during the period 2007 to 2011, resulting in a cumulative incidence of 64.2 per 1000 patients (Table 2).

More ankle ORIF procedures were performed in females (33,565) than in males (21,202); incidence of ankle ORIF procedures was higher in females (68.6/1000 patients) than in males (58.4/1000 patients) (Table 2); percentages of bimalleolar and trimalleolar fractures were higher in females (bi, 40.6%; tri, 27.8%) than in males (bi, 34.6%; tri, 15.2%); and percentage of lateral malleolus fractures was higher in males (50.2%) than in females (31.6%).

Incidence of ankle ORIF procedures was similar in the South (69.6/1000 patients), Midwest (69.4/100 patients), and West (65.1/1000 patients) but lower in the Northeast (43.3/1000 patients) (Table 2). Lateral malleolus fractures were the most common ankle fractures in the Midwest (40.7%) and West (41.3%), followed by bimalleolar fractures (Midwest, 36.3%; West 36.0%) and trimalleolar fractures (Midwest, 23.0%; West, 22.7%). Bimalleolar fractures were most common in the Northeast (40.2%) and South (39.8%), followed by lateral malleolus fractures (Northeast, 34.4%; South, 38.0%) and trimalleolar fractures (Northeast, 25.4%; South, 22.3%).

Discussion

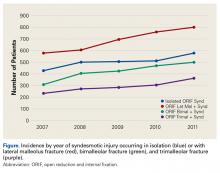

The present study found no significant change in number of lateral malleolus, bimalleolar, and trimalleolar ankle fracture ORIF procedures performed over the period 2007 to 2011. However, over the same period, incidence of syndesmosis fixation increased significantly in patients with isolated syndesmotic injuries and in patients with concomitant ankle fracture and syndesmotic injury. The largest percentage change was found in the bimalleolar ORIF group, which showed nearly a doubling of syndesmotic fixation over the 4-year study period, followed by a 38.1% increase in syndesmotic fixation in the trimalleolar ORIF group. Both groups had a syndesmotic fixation percentage change about twice that seen in the isolated lateral malleolus group.

There are several explanations for these trends. First, bimalleolar and trimalleolar fractures are more severe ankle fractures that tend to result from a more forceful mechanism, allowing for a higher rate of syndesmotic injury. Second, these trends likely do not reflect a true increase in the rate of syndesmosis injury but, rather, increased recognition of syndesmotic injury. Third, the data likely reflect a well-established approach to ankle fracture fixation and an increase in thinking that syndesmotic injuries should be stabilized in the setting of ankle fixation.

Incidence of syndesmotic injury as indicated by stabilization procedures can be compared with the data of Vosseller and colleagues,8 who reported an incidence of 6445 syndesmotic injuries per year in the United States. Our data showed fewer syndesmotic injuries, which may be related to use of CPT codes rather than ICD-9 codes for database searches, such that only operative syndesmotic injuries are represented in our data. Population differences between the 2 studies could also account for some of the differences in syndesmotic injury incidence.

We also found a significant change in the rate of hardware removal after syndesmosis ORIF. Across all treatment groups, incidence of screw removal decreased—a trend likely reflecting a change in attitude about the need for routine screw removal. Studies have shown that patients have favorable outcomes in the setting of syndesmotic screw loosening and screw breakage.37 Some authors have suggested that screw breakage or removal could be advantageous, as it allows the syndesmosis to settle into a more anatomical position after imperfect reduction.38 In addition, the trend of decreased syndesmotic screw removal could also have resulted from increased suture button fixation, which may less frequently require implant removal. Regardless, the overall trend is that routine syndesmotic implant removal has become less common.

This study had several limitations. First are the many limitations inherent to all studies that use large administrative databases, such as PearlDiver. The power of analysis depends on data quality; potential sources of error include accuracy of billing codes and physicians’ miscoding or noncoding. Although we tried to accurately represent a large population of interest through use of this database, we cannot be sure that the database represents a true cross-section of the United States. In addition, as we could not determine the method of syndesmotic fixation—the same CPT code is used for both suture button fixation and screw fixation—we could not establish trends for the rate of each method. More research is needed to establish these trends, and this research likely will require analysis of data from a large trauma center or from multiple centers.

Potential regional differences are another limitation. In the PearlDiver database, the South and Midwest are highly represented, the Northeast and West much less so. The South, Midwest, and West (but not the Northeast) had similar overall incidence and subgroup incidence of ankle ORIF. However, any regional differences in the rate of syndesmotic fixation could have skewed our data.

Ankle fractures and associated syndesmotic injuries remain a common problem. Although the prevalence of ankle fracture fixation has been relatively constant, the rate of syndesmosis stabilization has increased significantly. Young adults have the highest incidence of ankle fracture and associated syndesmotic fixation, but more ankle fractures occur in the large and growing elderly population. Increased awareness of syndesmotic injury likely has contributed to the recent rise in syndesmosis fixation seen in the present study. Given this trend, we recommend further analysis of outcome data and to establish treatment guidelines.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E472-E477. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, Zacchilli MA, Belmont PJ Jr. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(13):2279-2284.

2. Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: a review. Injury. 2006;37(8):691-697.

3. Miller AN, Paul O, Boraiah S, Parker RJ, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Functional outcomes after syndesmotic screw fixation and removal. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):12-16.

4. Edwards GS Jr, DeLee JC. Ankle diastasis without fracture. Foot Ankle. 1984;4(6):305-312.

5. Norkus SA, Floyd RT. The anatomy and mechanisms of syndesmotic ankle sprains. J Athl Train. 2001;36(1):68-73.

6. Brosky T, Nyland J, Nitz A, Caborn DN. The ankle ligaments: consideration of syndesmotic injury and implications for rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21(4):197-205.

7. Purvis GD. Displaced, unstable ankle fractures: classification, incidence, and management of a consecutive series. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(165):91-98.

8. Vosseller JT, Karl JW, Greisberg JK. Incidence of syndesmotic injury. Orthopedics. 2014;37(3):e226-e229.

9. Stark E, Tornetta P 3rd, Creevy WR. Syndesmotic instability in Weber B ankle fractures: a clinical evaluation. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(9):643-646.

10. Tornetta P 3rd, Axelrad TW, Sibai TA, Creevy WR. Treatment of the stress positive ligamentous SE4 ankle fracture: incidence of syndesmotic injury and clinical decision making. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(11):659-661.

11. Xenos JS, Hopkinson WJ, Mulligan ME, Olson EJ, Popovic NA. The tibiofibular syndesmosis. Evaluation of the ligamentous structures, methods of fixation, and radiographic assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(6):847-856.

12. Ebraheim NA, Lu J, Yang H, Mekhail AO, Yeasting RA. Radiographic and CT evaluation of tibiofibular syndesmotic diastasis: a cadaver study. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18(11):693-698.

13. Ahmad J, Raikin SM, Pour AE, Haytmanek C. Bioabsorbable screw fixation of the syndesmosis in unstable ankle injuries. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(2):99-105.

14. Hovis WD, Kaiser BW, Watson JT, Bucholz RW. Treatment of syndesmotic disruptions of the ankle with bioabsorbable screw fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(1):26-31.

15. Kaukonen JP, Lamberg T, Korkala O, Pajarinen J. Fixation of syndesmotic ruptures in 38 patients with a malleolar fracture: a randomized study comparing a metallic and a bioabsorbable screw. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(6):392-395.

16. Thordarson DB, Samuelson M, Shepherd LE, Merkle PF, Lee J. Bioabsorbable versus stainless steel screw fixation of the syndesmosis in pronation-lateral rotation ankle fractures: a prospective randomized trial. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22(4):335-338.

17. Moore JA Jr, Shank JR, Morgan SJ, Smith WR. Syndesmosis fixation: a comparison of three and four cortices of screw fixation without hardware removal. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(8):567-572.

18. Høiness P, Strømsøe K. Tricortical versus quadricortical syndesmosis fixation in ankle fractures: a prospective, randomized study comparing two methods of syndesmosis fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(6):331-337.

19. Huber T, Schmoelz W, Bölderl A. Motion of the fibula relative to the tibia and its alterations with syndesmosis screws: a cadaver study. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;18(3):203-209.

20. Needleman RL, Skrade DA, Stiehl JB. Effect of the syndesmotic screw on ankle motion. Foot Ankle. 1989;10(1):17-24.

21. Mendelsohn ES, Hoshino CM, Harris TG, Zinar DM. The effect of obesity on early failure after operative syndesmosis injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(4):201-206.

22. Schepers T. Acute distal tibiofibular syndesmosis injury: a systematic review of suture-button versus syndesmotic screw repair. Int Orthop. 2012;36(6):1199-1206.

23. Cottom JM, Hyer CF, Philbin TM, Berlet GC. Transosseous fixation of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis: comparison of an interosseous suture and Endobutton to traditional screw fixation in 50 cases. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48(6):620-630.

24. Thornes B, Shannon F, Guiney AM, Hession P, Masterson E. Suture-button syndesmosis fixation: accelerated rehabilitation and improved outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(431):207-212.

25. Willmott HJ, Singh B, David LA. Outcome and complications of treatment of ankle diastasis with tightrope fixation. Injury. 2009;40(11):1204-1206.

26. Qamar F, Kadakia A, Venkateswaran B. An anatomical way of treating ankle syndesmotic injuries. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(6):762-765.

27. Degroot H, Al-Omari AA, El Ghazaly SA. Outcomes of suture button repair of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(3):250-256.

28. Ramsey PL, Hamilton W. Changes in tibiotalar area of contact caused by lateral talar shift. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(3):356-357.

29. Weening B, Bhandari M. Predictors of functional outcome following transsyndesmotic screw fixation of ankle fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(2):102-108.

30. Sagi HC, Shah AR, Sanders RW. The functional consequence of syndesmotic joint malreduction at a minimum 2-year follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(7):439-443.

31. Naqvi GA, Cunningham P, Lynch B, Galvin R, Awan N. Fixation of ankle syndesmotic injuries: comparison of tightrope fixation and syndesmotic screw fixation for accuracy of syndesmotic reduction. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(12):2828-2835.

32. Marmor M, Hansen E, Han HK, Buckley J, Matityahu A. Limitations of standard fluoroscopy in detecting rotational malreduction of the syndesmosis in an ankle fracture model. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(6):616-622.

33. Franke J, von Recum J, Suda AJ, Grützner PA, Wendl K. Intraoperative three-dimensional imaging in the treatment of acute unstable syndesmotic injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(15):1386-1390.

34. Gardner MJ, Demetrakopoulos D, Briggs SM, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Malreduction of the tibiofibular syndesmosis in ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(10):788-792.

35. Miller AN, Carroll EA, Parker RJ, Boraiah S, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Direct visualization for syndesmotic stabilization of ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(5):419-426.

36. Ruan Z, Luo C, Shi Z, Zhang B, Zeng B, Zhang C. Intraoperative reduction of distal tibiofibular joint aided by three-dimensional fluoroscopy. Technol Health Care. 2011;19(3):161-166.

37. Hamid N, Loeffler BJ, Braddy W, Kellam JF, Cohen BE, Bosse MJ. Outcome after fixation of ankle fractures with an injury to the syndesmosis: the effect of the syndesmosis screw. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(8):1069-1073.

38. Song DJ, Lanzi JT, Groth AT, et al. The effect of syndesmosis screw removal on the reduction of the distal tibiofibular joint: a prospective radiographic study. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(6):543-548.

Acute ankle injuries are common problems treated by orthopedic surgeons. In the United States, nearly 2 million ankle sprains occur each year,1 and ankle fractures account for 9% to 18% of all fractures treated in emergency departments.2,3 Ankle injuries that involve the syndesmotic ligaments may result in instability and require specific treatment beyond fixation of the malleolar fractures.

The usual mechanism of syndesmotic injury is external rotation of the ankle with hyperdorsiflexion of a pronated or supinated foot.4,5 Syndesmotic injuries are estimated to occur in up to 10% of ankle sprains6 and up to 23% of all ankle fractures.7 Overall US incidence of syndesmotic injury is estimated at 6445 injuries per year.8 Syndesmotic injury occurs in 39% to 45% of supination-external rotation IV ankle fractures.9,10 Pronation-external rotation ankle fractures have the highest rate of syndesmotic injury. Syndesmotic injury may be less common in other types of malleolar fracture, but the exact incidence has not been reliably reported.

Traditionally, isolated nondisplaced syndesmotic injuries are treated nonoperatively, and syndesmotic injuries with concomitant malleolar fractures are treated surgically. Various options are available for syndesmotic fixation. The gold standard is syndesmotic screw placement from the lateral aspect of the fibula through the tibia. Fixation may be achieved with screws in a variety of configurations and formats. However, fixation with two 4.5-mm screws is stronger.11,12 Functional outcomes are similar, regardless of screw material,13-16 number of cortices,17 or number of screws.18 Disadvantages specific to screw fixation include altered ankle biomechanics,19,20 potential for screw breakage,21 and need for implant removal.3Alternatively, suture button fixation is said to be equally as effective as screw fixation in achieving syndesmotic reduction, and their functional outcomes are similar.22,23 The initial cost of suture button fixation is higher than that of screw fixation, but the difference may be offset by potential elimination of a second surgery for syndesmotic screw removal.24 Soft-tissue irritation caused by the suture material and local osteolysis are reported complications of suture button fixation.25-27

Regardless of fixation method used, achieving anatomical reduction of the syndesmosis is considered the most important factor in optimizing functional outcomes.28-31 However, achieving and verifying anatomical reduction of the syndesmosis during surgery can be quite challenging.30,32-34 Various methods of lowering the malreduction risk, including direct visualization of the tibiofibular joint during reduction30,35 and intraoperative 3-dimensional imaging,33,36 have been proposed.

In the study reported here, we used a US insurance database to determine the incidence and rate of syndesmotic stabilization within various ankle injuries and fracture patterns.

Materials and Methods

All data for this study were obtained from a publicly available for-fee healthcare database, the PearlDiver Patient Records Database, which includes procedural volumes and demographic information for patients with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses and procedures or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Data for the study were derived from 2 databases within PearlDiver: a private-payer database, which has its largest contribution (>30 million individual patient records for 2007-2011) from United HealthCare, and a Medicare database (>50 million patient records for 2007-2011). Access to the database was granted by PearlDiver Technologies for the purpose of academic research. The database was stored on a password-protected server maintained by PearlDiver.

We searched the database for cases of ankle fracture fixation, including fixation of isolated lateral malleolus (CPT 27792), bimalleolar (CPT 27814), and trimalleolar (CPTs 27822 and 27823) fractures. CPT 27829 was used to search for syndesmotic fixation, and CPT 20680 for implant removal. These codes were used individually and in combination.

Overall procedural volume data are reported as number of patients with the given CPT(s) in the database output and as incidence, calculated as number of patients with the CPT of interest normalized to total number of patients in the database for that particular subgroup. Results of age group and sex analyses are reported as number of patients reported in the database output and as percentage of patients who had the CPT procedure of interest that year. As United HealthCare is the largest contributor to the private-payer portion of the database and is represented most prominently in the southern region, data for the regional analysis are presented only as incidence. This incidence was calculated as number of patients in a particular region and year normalized to total number of patients in the database for that region or year. The regions were Midwest (IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI), Northeast (CT, MA, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT), South (AL, AR, DC, DE, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MI, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV), and West (AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NM, NV, OR, UT, WA, WY).

Chi-square linear-by-linear association analysis was used to determine the statistical significance of time trends in procedural volume, sex, age group, and region. For all statistical comparisons, P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Number of open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) procedures increased for all ankle fracture types over the period 2007 to 2011 (Table 1).

ORIF was performed for an ankle injury in 54,767 patients during the period 2007 to 2011, resulting in a cumulative incidence of 64.2 per 1000 patients (Table 2).

More ankle ORIF procedures were performed in females (33,565) than in males (21,202); incidence of ankle ORIF procedures was higher in females (68.6/1000 patients) than in males (58.4/1000 patients) (Table 2); percentages of bimalleolar and trimalleolar fractures were higher in females (bi, 40.6%; tri, 27.8%) than in males (bi, 34.6%; tri, 15.2%); and percentage of lateral malleolus fractures was higher in males (50.2%) than in females (31.6%).

Incidence of ankle ORIF procedures was similar in the South (69.6/1000 patients), Midwest (69.4/100 patients), and West (65.1/1000 patients) but lower in the Northeast (43.3/1000 patients) (Table 2). Lateral malleolus fractures were the most common ankle fractures in the Midwest (40.7%) and West (41.3%), followed by bimalleolar fractures (Midwest, 36.3%; West 36.0%) and trimalleolar fractures (Midwest, 23.0%; West, 22.7%). Bimalleolar fractures were most common in the Northeast (40.2%) and South (39.8%), followed by lateral malleolus fractures (Northeast, 34.4%; South, 38.0%) and trimalleolar fractures (Northeast, 25.4%; South, 22.3%).

Discussion

The present study found no significant change in number of lateral malleolus, bimalleolar, and trimalleolar ankle fracture ORIF procedures performed over the period 2007 to 2011. However, over the same period, incidence of syndesmosis fixation increased significantly in patients with isolated syndesmotic injuries and in patients with concomitant ankle fracture and syndesmotic injury. The largest percentage change was found in the bimalleolar ORIF group, which showed nearly a doubling of syndesmotic fixation over the 4-year study period, followed by a 38.1% increase in syndesmotic fixation in the trimalleolar ORIF group. Both groups had a syndesmotic fixation percentage change about twice that seen in the isolated lateral malleolus group.

There are several explanations for these trends. First, bimalleolar and trimalleolar fractures are more severe ankle fractures that tend to result from a more forceful mechanism, allowing for a higher rate of syndesmotic injury. Second, these trends likely do not reflect a true increase in the rate of syndesmosis injury but, rather, increased recognition of syndesmotic injury. Third, the data likely reflect a well-established approach to ankle fracture fixation and an increase in thinking that syndesmotic injuries should be stabilized in the setting of ankle fixation.

Incidence of syndesmotic injury as indicated by stabilization procedures can be compared with the data of Vosseller and colleagues,8 who reported an incidence of 6445 syndesmotic injuries per year in the United States. Our data showed fewer syndesmotic injuries, which may be related to use of CPT codes rather than ICD-9 codes for database searches, such that only operative syndesmotic injuries are represented in our data. Population differences between the 2 studies could also account for some of the differences in syndesmotic injury incidence.

We also found a significant change in the rate of hardware removal after syndesmosis ORIF. Across all treatment groups, incidence of screw removal decreased—a trend likely reflecting a change in attitude about the need for routine screw removal. Studies have shown that patients have favorable outcomes in the setting of syndesmotic screw loosening and screw breakage.37 Some authors have suggested that screw breakage or removal could be advantageous, as it allows the syndesmosis to settle into a more anatomical position after imperfect reduction.38 In addition, the trend of decreased syndesmotic screw removal could also have resulted from increased suture button fixation, which may less frequently require implant removal. Regardless, the overall trend is that routine syndesmotic implant removal has become less common.

This study had several limitations. First are the many limitations inherent to all studies that use large administrative databases, such as PearlDiver. The power of analysis depends on data quality; potential sources of error include accuracy of billing codes and physicians’ miscoding or noncoding. Although we tried to accurately represent a large population of interest through use of this database, we cannot be sure that the database represents a true cross-section of the United States. In addition, as we could not determine the method of syndesmotic fixation—the same CPT code is used for both suture button fixation and screw fixation—we could not establish trends for the rate of each method. More research is needed to establish these trends, and this research likely will require analysis of data from a large trauma center or from multiple centers.

Potential regional differences are another limitation. In the PearlDiver database, the South and Midwest are highly represented, the Northeast and West much less so. The South, Midwest, and West (but not the Northeast) had similar overall incidence and subgroup incidence of ankle ORIF. However, any regional differences in the rate of syndesmotic fixation could have skewed our data.

Ankle fractures and associated syndesmotic injuries remain a common problem. Although the prevalence of ankle fracture fixation has been relatively constant, the rate of syndesmosis stabilization has increased significantly. Young adults have the highest incidence of ankle fracture and associated syndesmotic fixation, but more ankle fractures occur in the large and growing elderly population. Increased awareness of syndesmotic injury likely has contributed to the recent rise in syndesmosis fixation seen in the present study. Given this trend, we recommend further analysis of outcome data and to establish treatment guidelines.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E472-E477. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Acute ankle injuries are common problems treated by orthopedic surgeons. In the United States, nearly 2 million ankle sprains occur each year,1 and ankle fractures account for 9% to 18% of all fractures treated in emergency departments.2,3 Ankle injuries that involve the syndesmotic ligaments may result in instability and require specific treatment beyond fixation of the malleolar fractures.

The usual mechanism of syndesmotic injury is external rotation of the ankle with hyperdorsiflexion of a pronated or supinated foot.4,5 Syndesmotic injuries are estimated to occur in up to 10% of ankle sprains6 and up to 23% of all ankle fractures.7 Overall US incidence of syndesmotic injury is estimated at 6445 injuries per year.8 Syndesmotic injury occurs in 39% to 45% of supination-external rotation IV ankle fractures.9,10 Pronation-external rotation ankle fractures have the highest rate of syndesmotic injury. Syndesmotic injury may be less common in other types of malleolar fracture, but the exact incidence has not been reliably reported.

Traditionally, isolated nondisplaced syndesmotic injuries are treated nonoperatively, and syndesmotic injuries with concomitant malleolar fractures are treated surgically. Various options are available for syndesmotic fixation. The gold standard is syndesmotic screw placement from the lateral aspect of the fibula through the tibia. Fixation may be achieved with screws in a variety of configurations and formats. However, fixation with two 4.5-mm screws is stronger.11,12 Functional outcomes are similar, regardless of screw material,13-16 number of cortices,17 or number of screws.18 Disadvantages specific to screw fixation include altered ankle biomechanics,19,20 potential for screw breakage,21 and need for implant removal.3Alternatively, suture button fixation is said to be equally as effective as screw fixation in achieving syndesmotic reduction, and their functional outcomes are similar.22,23 The initial cost of suture button fixation is higher than that of screw fixation, but the difference may be offset by potential elimination of a second surgery for syndesmotic screw removal.24 Soft-tissue irritation caused by the suture material and local osteolysis are reported complications of suture button fixation.25-27

Regardless of fixation method used, achieving anatomical reduction of the syndesmosis is considered the most important factor in optimizing functional outcomes.28-31 However, achieving and verifying anatomical reduction of the syndesmosis during surgery can be quite challenging.30,32-34 Various methods of lowering the malreduction risk, including direct visualization of the tibiofibular joint during reduction30,35 and intraoperative 3-dimensional imaging,33,36 have been proposed.

In the study reported here, we used a US insurance database to determine the incidence and rate of syndesmotic stabilization within various ankle injuries and fracture patterns.

Materials and Methods

All data for this study were obtained from a publicly available for-fee healthcare database, the PearlDiver Patient Records Database, which includes procedural volumes and demographic information for patients with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses and procedures or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Data for the study were derived from 2 databases within PearlDiver: a private-payer database, which has its largest contribution (>30 million individual patient records for 2007-2011) from United HealthCare, and a Medicare database (>50 million patient records for 2007-2011). Access to the database was granted by PearlDiver Technologies for the purpose of academic research. The database was stored on a password-protected server maintained by PearlDiver.

We searched the database for cases of ankle fracture fixation, including fixation of isolated lateral malleolus (CPT 27792), bimalleolar (CPT 27814), and trimalleolar (CPTs 27822 and 27823) fractures. CPT 27829 was used to search for syndesmotic fixation, and CPT 20680 for implant removal. These codes were used individually and in combination.

Overall procedural volume data are reported as number of patients with the given CPT(s) in the database output and as incidence, calculated as number of patients with the CPT of interest normalized to total number of patients in the database for that particular subgroup. Results of age group and sex analyses are reported as number of patients reported in the database output and as percentage of patients who had the CPT procedure of interest that year. As United HealthCare is the largest contributor to the private-payer portion of the database and is represented most prominently in the southern region, data for the regional analysis are presented only as incidence. This incidence was calculated as number of patients in a particular region and year normalized to total number of patients in the database for that region or year. The regions were Midwest (IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI), Northeast (CT, MA, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT), South (AL, AR, DC, DE, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MI, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV), and West (AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NM, NV, OR, UT, WA, WY).

Chi-square linear-by-linear association analysis was used to determine the statistical significance of time trends in procedural volume, sex, age group, and region. For all statistical comparisons, P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Number of open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) procedures increased for all ankle fracture types over the period 2007 to 2011 (Table 1).

ORIF was performed for an ankle injury in 54,767 patients during the period 2007 to 2011, resulting in a cumulative incidence of 64.2 per 1000 patients (Table 2).

More ankle ORIF procedures were performed in females (33,565) than in males (21,202); incidence of ankle ORIF procedures was higher in females (68.6/1000 patients) than in males (58.4/1000 patients) (Table 2); percentages of bimalleolar and trimalleolar fractures were higher in females (bi, 40.6%; tri, 27.8%) than in males (bi, 34.6%; tri, 15.2%); and percentage of lateral malleolus fractures was higher in males (50.2%) than in females (31.6%).

Incidence of ankle ORIF procedures was similar in the South (69.6/1000 patients), Midwest (69.4/100 patients), and West (65.1/1000 patients) but lower in the Northeast (43.3/1000 patients) (Table 2). Lateral malleolus fractures were the most common ankle fractures in the Midwest (40.7%) and West (41.3%), followed by bimalleolar fractures (Midwest, 36.3%; West 36.0%) and trimalleolar fractures (Midwest, 23.0%; West, 22.7%). Bimalleolar fractures were most common in the Northeast (40.2%) and South (39.8%), followed by lateral malleolus fractures (Northeast, 34.4%; South, 38.0%) and trimalleolar fractures (Northeast, 25.4%; South, 22.3%).

Discussion

The present study found no significant change in number of lateral malleolus, bimalleolar, and trimalleolar ankle fracture ORIF procedures performed over the period 2007 to 2011. However, over the same period, incidence of syndesmosis fixation increased significantly in patients with isolated syndesmotic injuries and in patients with concomitant ankle fracture and syndesmotic injury. The largest percentage change was found in the bimalleolar ORIF group, which showed nearly a doubling of syndesmotic fixation over the 4-year study period, followed by a 38.1% increase in syndesmotic fixation in the trimalleolar ORIF group. Both groups had a syndesmotic fixation percentage change about twice that seen in the isolated lateral malleolus group.

There are several explanations for these trends. First, bimalleolar and trimalleolar fractures are more severe ankle fractures that tend to result from a more forceful mechanism, allowing for a higher rate of syndesmotic injury. Second, these trends likely do not reflect a true increase in the rate of syndesmosis injury but, rather, increased recognition of syndesmotic injury. Third, the data likely reflect a well-established approach to ankle fracture fixation and an increase in thinking that syndesmotic injuries should be stabilized in the setting of ankle fixation.

Incidence of syndesmotic injury as indicated by stabilization procedures can be compared with the data of Vosseller and colleagues,8 who reported an incidence of 6445 syndesmotic injuries per year in the United States. Our data showed fewer syndesmotic injuries, which may be related to use of CPT codes rather than ICD-9 codes for database searches, such that only operative syndesmotic injuries are represented in our data. Population differences between the 2 studies could also account for some of the differences in syndesmotic injury incidence.

We also found a significant change in the rate of hardware removal after syndesmosis ORIF. Across all treatment groups, incidence of screw removal decreased—a trend likely reflecting a change in attitude about the need for routine screw removal. Studies have shown that patients have favorable outcomes in the setting of syndesmotic screw loosening and screw breakage.37 Some authors have suggested that screw breakage or removal could be advantageous, as it allows the syndesmosis to settle into a more anatomical position after imperfect reduction.38 In addition, the trend of decreased syndesmotic screw removal could also have resulted from increased suture button fixation, which may less frequently require implant removal. Regardless, the overall trend is that routine syndesmotic implant removal has become less common.

This study had several limitations. First are the many limitations inherent to all studies that use large administrative databases, such as PearlDiver. The power of analysis depends on data quality; potential sources of error include accuracy of billing codes and physicians’ miscoding or noncoding. Although we tried to accurately represent a large population of interest through use of this database, we cannot be sure that the database represents a true cross-section of the United States. In addition, as we could not determine the method of syndesmotic fixation—the same CPT code is used for both suture button fixation and screw fixation—we could not establish trends for the rate of each method. More research is needed to establish these trends, and this research likely will require analysis of data from a large trauma center or from multiple centers.

Potential regional differences are another limitation. In the PearlDiver database, the South and Midwest are highly represented, the Northeast and West much less so. The South, Midwest, and West (but not the Northeast) had similar overall incidence and subgroup incidence of ankle ORIF. However, any regional differences in the rate of syndesmotic fixation could have skewed our data.

Ankle fractures and associated syndesmotic injuries remain a common problem. Although the prevalence of ankle fracture fixation has been relatively constant, the rate of syndesmosis stabilization has increased significantly. Young adults have the highest incidence of ankle fracture and associated syndesmotic fixation, but more ankle fractures occur in the large and growing elderly population. Increased awareness of syndesmotic injury likely has contributed to the recent rise in syndesmosis fixation seen in the present study. Given this trend, we recommend further analysis of outcome data and to establish treatment guidelines.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E472-E477. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, Zacchilli MA, Belmont PJ Jr. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(13):2279-2284.

2. Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: a review. Injury. 2006;37(8):691-697.

3. Miller AN, Paul O, Boraiah S, Parker RJ, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Functional outcomes after syndesmotic screw fixation and removal. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):12-16.

4. Edwards GS Jr, DeLee JC. Ankle diastasis without fracture. Foot Ankle. 1984;4(6):305-312.

5. Norkus SA, Floyd RT. The anatomy and mechanisms of syndesmotic ankle sprains. J Athl Train. 2001;36(1):68-73.

6. Brosky T, Nyland J, Nitz A, Caborn DN. The ankle ligaments: consideration of syndesmotic injury and implications for rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21(4):197-205.

7. Purvis GD. Displaced, unstable ankle fractures: classification, incidence, and management of a consecutive series. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(165):91-98.

8. Vosseller JT, Karl JW, Greisberg JK. Incidence of syndesmotic injury. Orthopedics. 2014;37(3):e226-e229.

9. Stark E, Tornetta P 3rd, Creevy WR. Syndesmotic instability in Weber B ankle fractures: a clinical evaluation. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(9):643-646.

10. Tornetta P 3rd, Axelrad TW, Sibai TA, Creevy WR. Treatment of the stress positive ligamentous SE4 ankle fracture: incidence of syndesmotic injury and clinical decision making. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(11):659-661.

11. Xenos JS, Hopkinson WJ, Mulligan ME, Olson EJ, Popovic NA. The tibiofibular syndesmosis. Evaluation of the ligamentous structures, methods of fixation, and radiographic assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(6):847-856.

12. Ebraheim NA, Lu J, Yang H, Mekhail AO, Yeasting RA. Radiographic and CT evaluation of tibiofibular syndesmotic diastasis: a cadaver study. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18(11):693-698.

13. Ahmad J, Raikin SM, Pour AE, Haytmanek C. Bioabsorbable screw fixation of the syndesmosis in unstable ankle injuries. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(2):99-105.

14. Hovis WD, Kaiser BW, Watson JT, Bucholz RW. Treatment of syndesmotic disruptions of the ankle with bioabsorbable screw fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(1):26-31.

15. Kaukonen JP, Lamberg T, Korkala O, Pajarinen J. Fixation of syndesmotic ruptures in 38 patients with a malleolar fracture: a randomized study comparing a metallic and a bioabsorbable screw. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(6):392-395.

16. Thordarson DB, Samuelson M, Shepherd LE, Merkle PF, Lee J. Bioabsorbable versus stainless steel screw fixation of the syndesmosis in pronation-lateral rotation ankle fractures: a prospective randomized trial. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22(4):335-338.

17. Moore JA Jr, Shank JR, Morgan SJ, Smith WR. Syndesmosis fixation: a comparison of three and four cortices of screw fixation without hardware removal. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(8):567-572.

18. Høiness P, Strømsøe K. Tricortical versus quadricortical syndesmosis fixation in ankle fractures: a prospective, randomized study comparing two methods of syndesmosis fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(6):331-337.

19. Huber T, Schmoelz W, Bölderl A. Motion of the fibula relative to the tibia and its alterations with syndesmosis screws: a cadaver study. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;18(3):203-209.

20. Needleman RL, Skrade DA, Stiehl JB. Effect of the syndesmotic screw on ankle motion. Foot Ankle. 1989;10(1):17-24.

21. Mendelsohn ES, Hoshino CM, Harris TG, Zinar DM. The effect of obesity on early failure after operative syndesmosis injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(4):201-206.

22. Schepers T. Acute distal tibiofibular syndesmosis injury: a systematic review of suture-button versus syndesmotic screw repair. Int Orthop. 2012;36(6):1199-1206.

23. Cottom JM, Hyer CF, Philbin TM, Berlet GC. Transosseous fixation of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis: comparison of an interosseous suture and Endobutton to traditional screw fixation in 50 cases. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48(6):620-630.

24. Thornes B, Shannon F, Guiney AM, Hession P, Masterson E. Suture-button syndesmosis fixation: accelerated rehabilitation and improved outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(431):207-212.

25. Willmott HJ, Singh B, David LA. Outcome and complications of treatment of ankle diastasis with tightrope fixation. Injury. 2009;40(11):1204-1206.

26. Qamar F, Kadakia A, Venkateswaran B. An anatomical way of treating ankle syndesmotic injuries. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(6):762-765.

27. Degroot H, Al-Omari AA, El Ghazaly SA. Outcomes of suture button repair of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(3):250-256.

28. Ramsey PL, Hamilton W. Changes in tibiotalar area of contact caused by lateral talar shift. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(3):356-357.

29. Weening B, Bhandari M. Predictors of functional outcome following transsyndesmotic screw fixation of ankle fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(2):102-108.

30. Sagi HC, Shah AR, Sanders RW. The functional consequence of syndesmotic joint malreduction at a minimum 2-year follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(7):439-443.

31. Naqvi GA, Cunningham P, Lynch B, Galvin R, Awan N. Fixation of ankle syndesmotic injuries: comparison of tightrope fixation and syndesmotic screw fixation for accuracy of syndesmotic reduction. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(12):2828-2835.

32. Marmor M, Hansen E, Han HK, Buckley J, Matityahu A. Limitations of standard fluoroscopy in detecting rotational malreduction of the syndesmosis in an ankle fracture model. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(6):616-622.

33. Franke J, von Recum J, Suda AJ, Grützner PA, Wendl K. Intraoperative three-dimensional imaging in the treatment of acute unstable syndesmotic injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(15):1386-1390.

34. Gardner MJ, Demetrakopoulos D, Briggs SM, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Malreduction of the tibiofibular syndesmosis in ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(10):788-792.

35. Miller AN, Carroll EA, Parker RJ, Boraiah S, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Direct visualization for syndesmotic stabilization of ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(5):419-426.

36. Ruan Z, Luo C, Shi Z, Zhang B, Zeng B, Zhang C. Intraoperative reduction of distal tibiofibular joint aided by three-dimensional fluoroscopy. Technol Health Care. 2011;19(3):161-166.

37. Hamid N, Loeffler BJ, Braddy W, Kellam JF, Cohen BE, Bosse MJ. Outcome after fixation of ankle fractures with an injury to the syndesmosis: the effect of the syndesmosis screw. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(8):1069-1073.

38. Song DJ, Lanzi JT, Groth AT, et al. The effect of syndesmosis screw removal on the reduction of the distal tibiofibular joint: a prospective radiographic study. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(6):543-548.

1. Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, Zacchilli MA, Belmont PJ Jr. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(13):2279-2284.

2. Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: a review. Injury. 2006;37(8):691-697.

3. Miller AN, Paul O, Boraiah S, Parker RJ, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Functional outcomes after syndesmotic screw fixation and removal. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(1):12-16.

4. Edwards GS Jr, DeLee JC. Ankle diastasis without fracture. Foot Ankle. 1984;4(6):305-312.

5. Norkus SA, Floyd RT. The anatomy and mechanisms of syndesmotic ankle sprains. J Athl Train. 2001;36(1):68-73.

6. Brosky T, Nyland J, Nitz A, Caborn DN. The ankle ligaments: consideration of syndesmotic injury and implications for rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21(4):197-205.

7. Purvis GD. Displaced, unstable ankle fractures: classification, incidence, and management of a consecutive series. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(165):91-98.

8. Vosseller JT, Karl JW, Greisberg JK. Incidence of syndesmotic injury. Orthopedics. 2014;37(3):e226-e229.

9. Stark E, Tornetta P 3rd, Creevy WR. Syndesmotic instability in Weber B ankle fractures: a clinical evaluation. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(9):643-646.

10. Tornetta P 3rd, Axelrad TW, Sibai TA, Creevy WR. Treatment of the stress positive ligamentous SE4 ankle fracture: incidence of syndesmotic injury and clinical decision making. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(11):659-661.

11. Xenos JS, Hopkinson WJ, Mulligan ME, Olson EJ, Popovic NA. The tibiofibular syndesmosis. Evaluation of the ligamentous structures, methods of fixation, and radiographic assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(6):847-856.

12. Ebraheim NA, Lu J, Yang H, Mekhail AO, Yeasting RA. Radiographic and CT evaluation of tibiofibular syndesmotic diastasis: a cadaver study. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18(11):693-698.

13. Ahmad J, Raikin SM, Pour AE, Haytmanek C. Bioabsorbable screw fixation of the syndesmosis in unstable ankle injuries. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(2):99-105.

14. Hovis WD, Kaiser BW, Watson JT, Bucholz RW. Treatment of syndesmotic disruptions of the ankle with bioabsorbable screw fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(1):26-31.

15. Kaukonen JP, Lamberg T, Korkala O, Pajarinen J. Fixation of syndesmotic ruptures in 38 patients with a malleolar fracture: a randomized study comparing a metallic and a bioabsorbable screw. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(6):392-395.

16. Thordarson DB, Samuelson M, Shepherd LE, Merkle PF, Lee J. Bioabsorbable versus stainless steel screw fixation of the syndesmosis in pronation-lateral rotation ankle fractures: a prospective randomized trial. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22(4):335-338.

17. Moore JA Jr, Shank JR, Morgan SJ, Smith WR. Syndesmosis fixation: a comparison of three and four cortices of screw fixation without hardware removal. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(8):567-572.

18. Høiness P, Strømsøe K. Tricortical versus quadricortical syndesmosis fixation in ankle fractures: a prospective, randomized study comparing two methods of syndesmosis fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(6):331-337.

19. Huber T, Schmoelz W, Bölderl A. Motion of the fibula relative to the tibia and its alterations with syndesmosis screws: a cadaver study. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;18(3):203-209.

20. Needleman RL, Skrade DA, Stiehl JB. Effect of the syndesmotic screw on ankle motion. Foot Ankle. 1989;10(1):17-24.

21. Mendelsohn ES, Hoshino CM, Harris TG, Zinar DM. The effect of obesity on early failure after operative syndesmosis injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(4):201-206.

22. Schepers T. Acute distal tibiofibular syndesmosis injury: a systematic review of suture-button versus syndesmotic screw repair. Int Orthop. 2012;36(6):1199-1206.

23. Cottom JM, Hyer CF, Philbin TM, Berlet GC. Transosseous fixation of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis: comparison of an interosseous suture and Endobutton to traditional screw fixation in 50 cases. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48(6):620-630.

24. Thornes B, Shannon F, Guiney AM, Hession P, Masterson E. Suture-button syndesmosis fixation: accelerated rehabilitation and improved outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(431):207-212.

25. Willmott HJ, Singh B, David LA. Outcome and complications of treatment of ankle diastasis with tightrope fixation. Injury. 2009;40(11):1204-1206.

26. Qamar F, Kadakia A, Venkateswaran B. An anatomical way of treating ankle syndesmotic injuries. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(6):762-765.

27. Degroot H, Al-Omari AA, El Ghazaly SA. Outcomes of suture button repair of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(3):250-256.

28. Ramsey PL, Hamilton W. Changes in tibiotalar area of contact caused by lateral talar shift. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(3):356-357.

29. Weening B, Bhandari M. Predictors of functional outcome following transsyndesmotic screw fixation of ankle fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(2):102-108.

30. Sagi HC, Shah AR, Sanders RW. The functional consequence of syndesmotic joint malreduction at a minimum 2-year follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(7):439-443.

31. Naqvi GA, Cunningham P, Lynch B, Galvin R, Awan N. Fixation of ankle syndesmotic injuries: comparison of tightrope fixation and syndesmotic screw fixation for accuracy of syndesmotic reduction. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(12):2828-2835.

32. Marmor M, Hansen E, Han HK, Buckley J, Matityahu A. Limitations of standard fluoroscopy in detecting rotational malreduction of the syndesmosis in an ankle fracture model. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(6):616-622.

33. Franke J, von Recum J, Suda AJ, Grützner PA, Wendl K. Intraoperative three-dimensional imaging in the treatment of acute unstable syndesmotic injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(15):1386-1390.

34. Gardner MJ, Demetrakopoulos D, Briggs SM, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Malreduction of the tibiofibular syndesmosis in ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(10):788-792.

35. Miller AN, Carroll EA, Parker RJ, Boraiah S, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. Direct visualization for syndesmotic stabilization of ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(5):419-426.

36. Ruan Z, Luo C, Shi Z, Zhang B, Zeng B, Zhang C. Intraoperative reduction of distal tibiofibular joint aided by three-dimensional fluoroscopy. Technol Health Care. 2011;19(3):161-166.

37. Hamid N, Loeffler BJ, Braddy W, Kellam JF, Cohen BE, Bosse MJ. Outcome after fixation of ankle fractures with an injury to the syndesmosis: the effect of the syndesmosis screw. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(8):1069-1073.

38. Song DJ, Lanzi JT, Groth AT, et al. The effect of syndesmosis screw removal on the reduction of the distal tibiofibular joint: a prospective radiographic study. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(6):543-548.

Topical Imiquimod Clears Invasive Melanoma

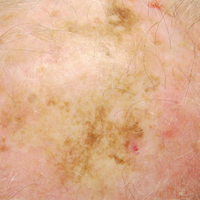

Malignant melanoma has continually shown a pattern of increased incidence and mortality over the last 50 years, especially in fair-skinned individuals. In fact, malignant melanoma has the highest mortality rate of all skin cancers in white individuals. Currently, wide local surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment of primary cutaneous melanomas.1 The margins vary in size according to the Breslow thickness (or depth) of the involved tumor. As such, advancements in melanoma treatment continue to be studied. We present the case of a patient with invasive melanoma that was cleared with topical imiquimod.

Case Report

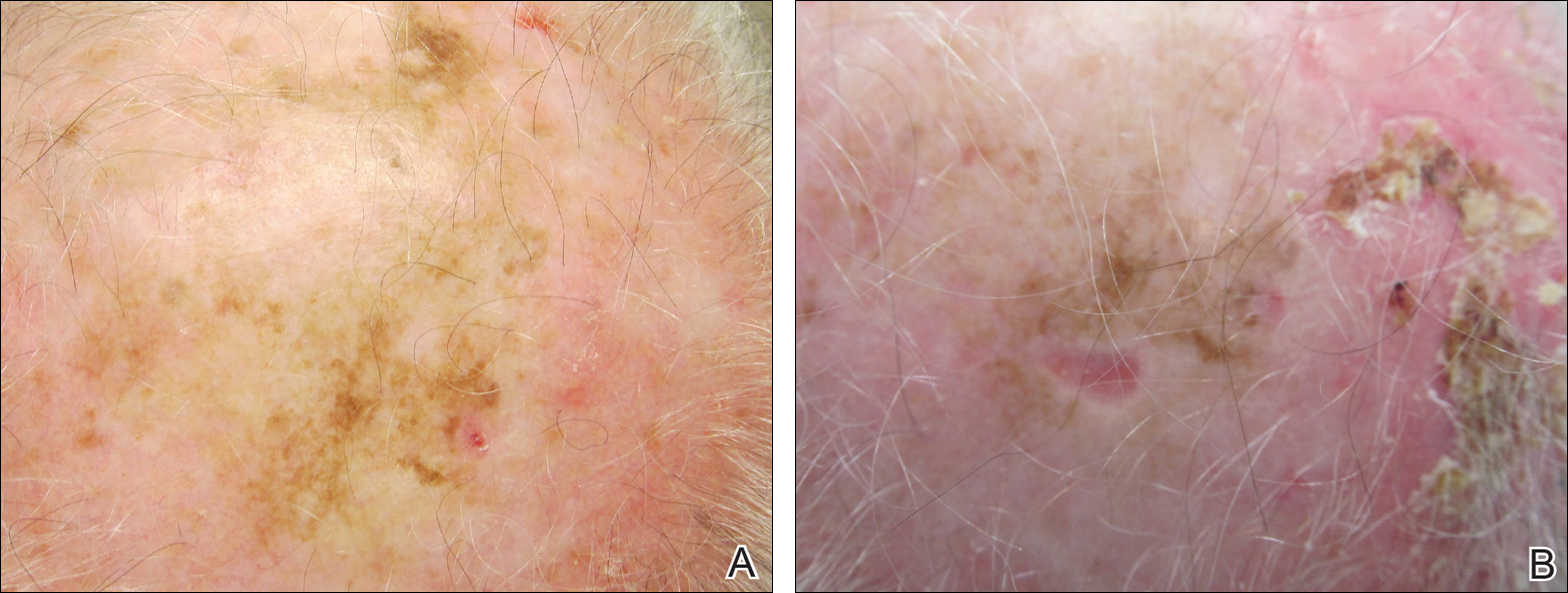

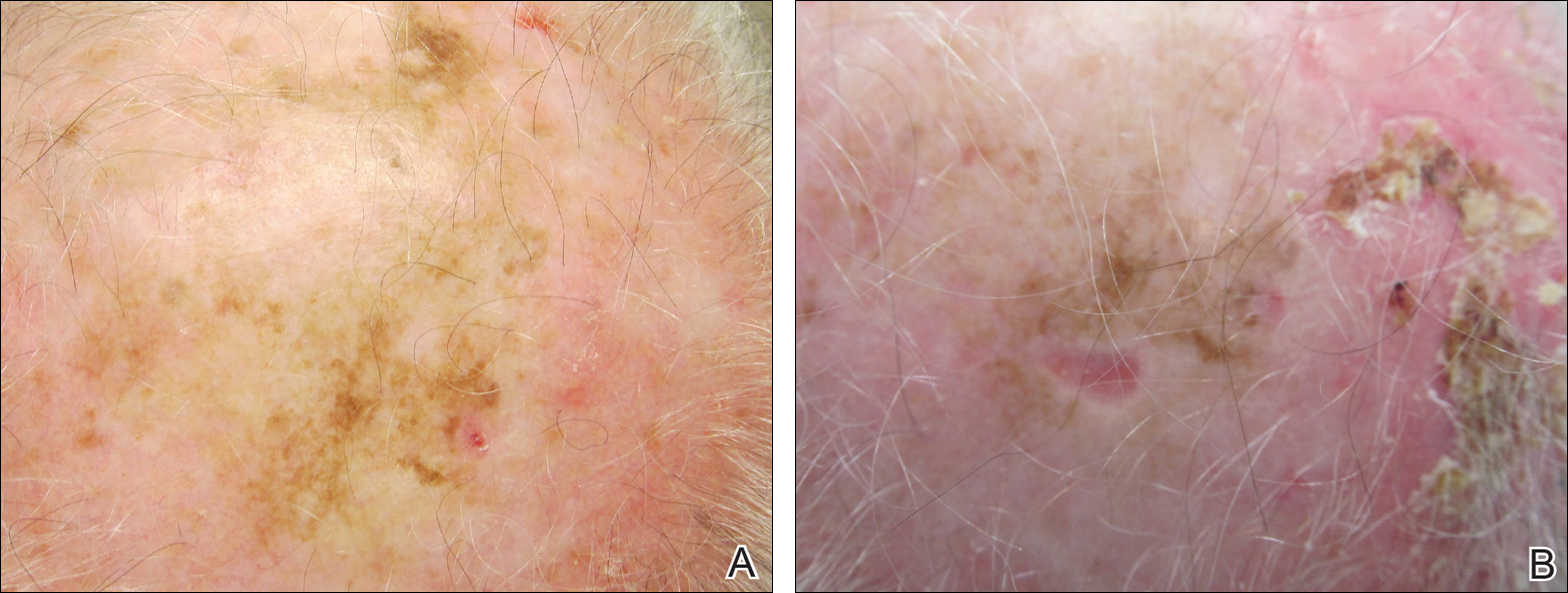

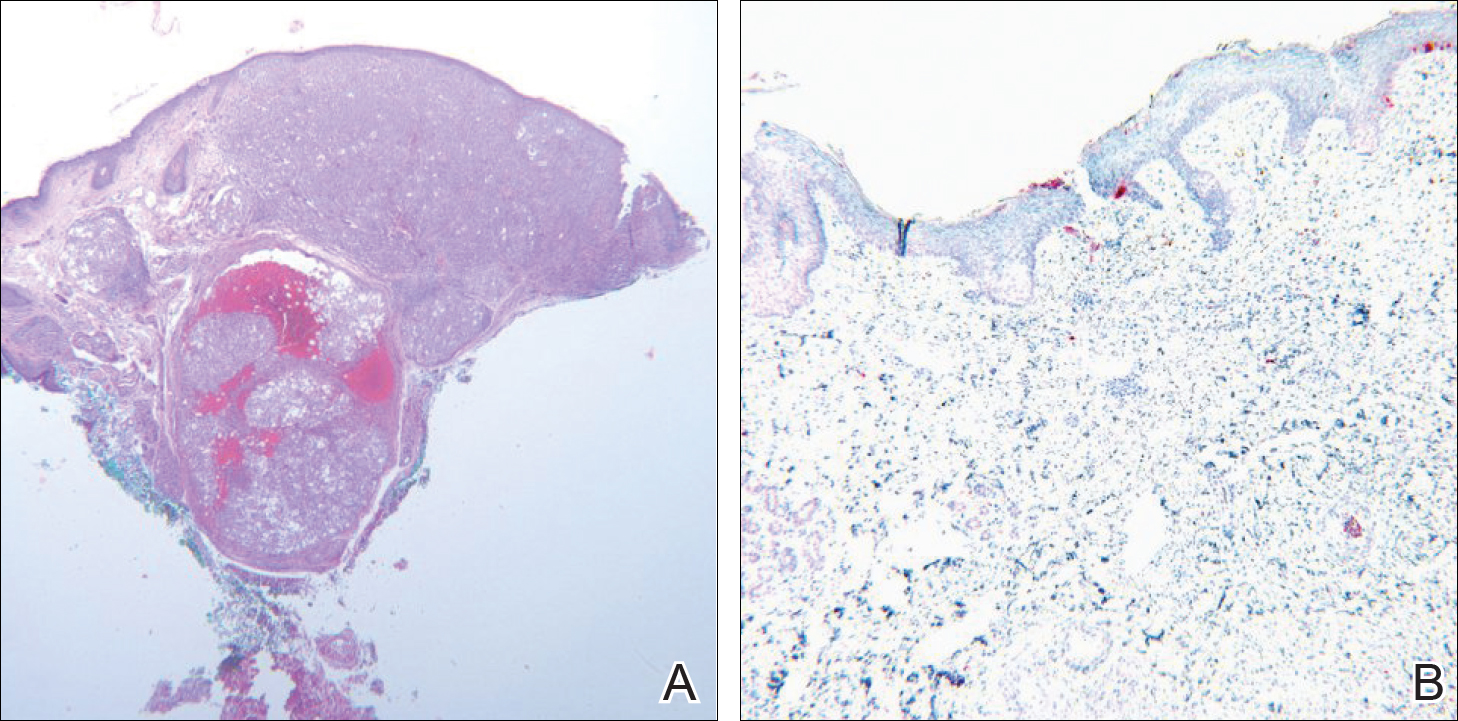

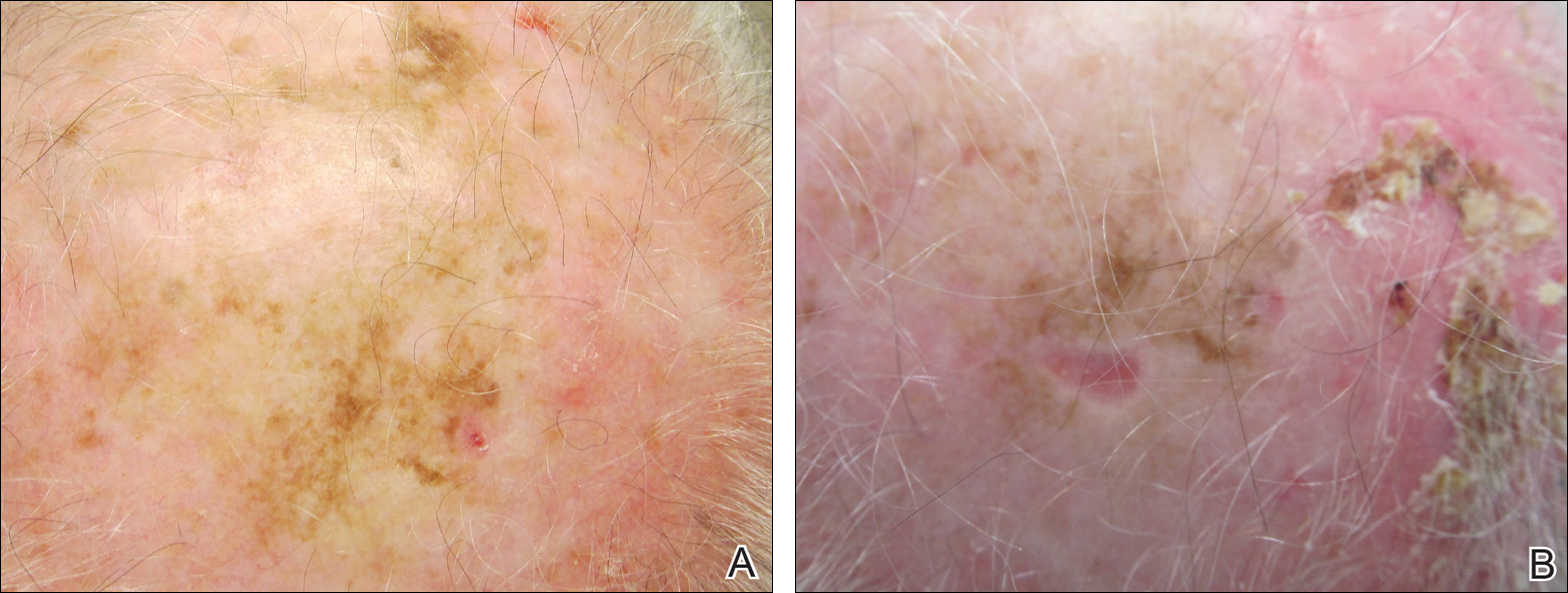

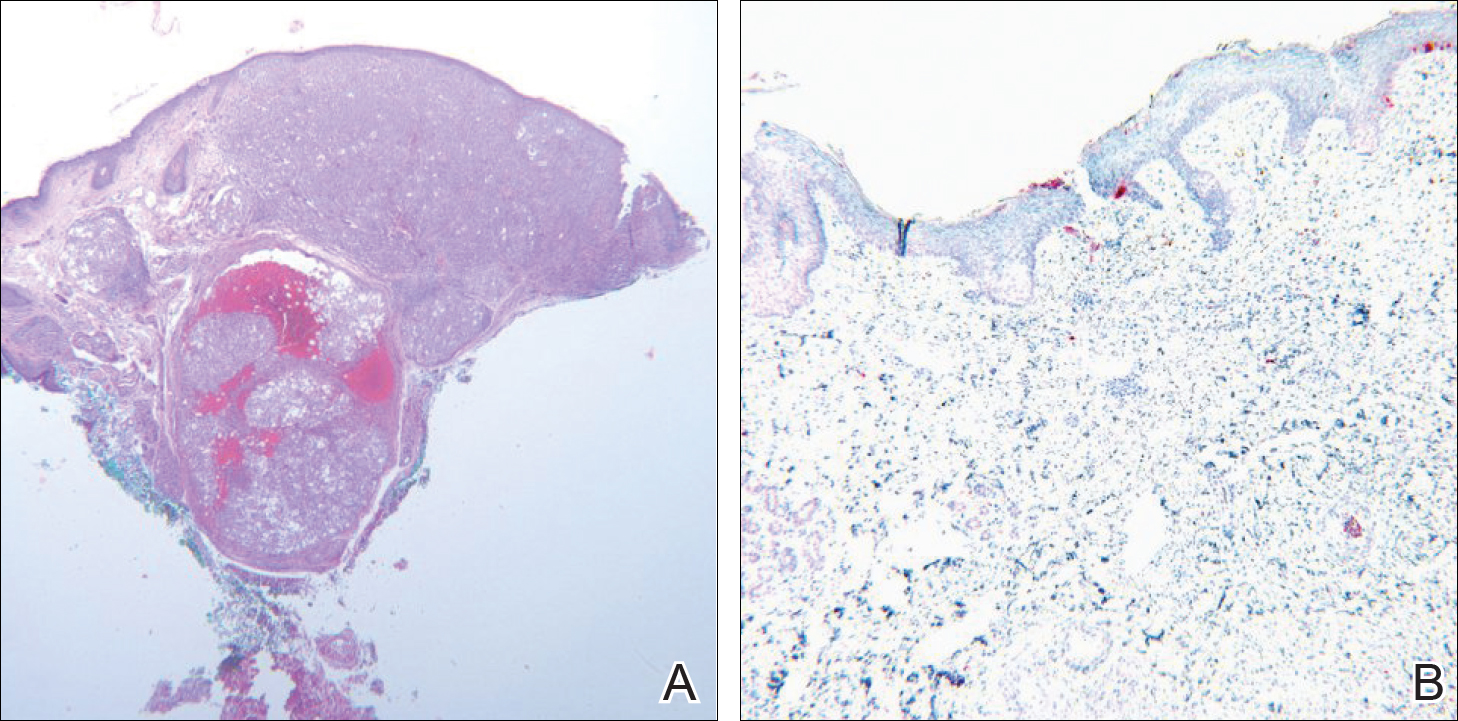

A 71-year-old man presented with biopsy-proven malignant melanoma on the right posterior scalp that was diagnosed a few weeks prior. The melanoma was invasive with a depth of 0.73 mm. The patient also had an approximately 8-cm, irregular, patchy area of hyperpigmentation involving almost the entire crown of the head (Figure 1A). The biopsy site used for melanoma diagnosis was on the right posterior aspect of the hyperpigmented area where a symptomatic pigmented papule was located. To determine if the rest of this macule represented an extension of the proven malignancy, surveillance biopsies were taken at the 12 o'clock (anterior aspect), 3 o'clock, 6 o'clock, and 9 o'clock positions on the head. All of the biopsies came back as lentigo simplex, which presented a clinical problem in that the boundaries of the invasive melanoma merged with the lentigo simplex and were not clinically apparent. Because an exact boundary could not be visualized, the entire area was treated with imiquimod cream 5% once nightly at bedtime for 4 weeks prior to excision of the original biopsy site. There was a notable decrease in hyperpigmentation in the treated area after 4 weeks of therapy (Figure 1B). The original biopsy site was then excised with a 0.6-cm margin and a complex linear repair was performed. Histologic examination of the excised specimen showed no residual melanoma.

Comment

Although surgical excision is the recommended treatment of cutaneous melanoma,1 in some cases the defect following an excision can be quite large or even disfiguring. To minimize the size of the excision site, other treatment modalities should be studied. Imiquimod is an immunomodulating agent that exerts antitumor and antiviral effects. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved imiquimod for treatment of genital warts, actinic keratoses, and superficial basal cell carcinoma.2 The most common side effects of topical imiquimod involve application-site reactions such as erythema, swelling, and crusting of the treated area. Ulceration of the skin also is possible. A small percentage of individuals have experienced systemic flulike symptoms after using topical imiquimod. Topical imiquimod has been used off label to treat noninvasive forms of melanoma. The topical therapy has been reported to clear melanoma in situ and lentigo maligna.2,3 In addition, imiquimod has been used as a palliative therapy for cutaneous metastatic melanoma.4,5 In another case of a primary melanoma that responded to topical imiquimod, clinical and histological clearance of a recurrent oral mucosa melanoma was obtained.6