User login

Apply for These 2017 Research Grants Before They Close

Round out 2016 by preparing for a 2017 AGA Research Foundation grant. Eight grants are currently open for both established and young investigators, but all will close in January 2017. Make sure you’re prepared to submit your application before the deadline.

Complete information about these and other research awards is available on gastro.org. All recipients will be acknowledged at the Research Recognition Celebration at Digestive Disease Week® 2017 (www.ddw.org) in Chicago, IL.

Jan 6. 2017

- The AGA-Elsevier Gut Microbiome Pilot Research Award will provide $25,000 to support pilot research projects pertaining to the gut microbiome.

- The AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award is a 1-year grant providing young investigators, instructors, research associates, or equivalents $25,000 to support pilot research projects in gastroenterology- or hepatology-related areas.

- The AGA-Medtronic Research & Development Pilot Award in Technology grants $31,000 for 1 year to investigators to support the research and development of novel devices or technologies that will potentially impact the diagnosis or treatment of digestive disease.

Jan. 13, 2017

- The AGA-Rome Foundation Functional GI and Motility Disorders Pilot Research Award offers $50,000 for 1 year to early-stage investigators, established investigators, postdoctoral research fellows and combined research and clinical fellows to support pilot research projects pertaining to functional GI and motility disorders.

- The AGA Microbiome Junior Investigator Research Award is a 2-year award of $60,000 for junior investigators engaged in basic, translational, clinical, or health services research related to the gut microbiome.

- The AGA-Pfizer Pilot Research Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease is a 1-year, $30,000 award offered to established and young investigators to support pilot research projects related to IBD.

Jan. 20, 2017

- The AGA-June & Donald O. Castell, MD, Esophageal Clinical Research Award is a 1-year, $25,000 grant that provides research or salary support for junior faculty involved in clinical research in esophageal diseases.

- The AGA-Caroline Craig Augustyn & Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer is a 1-year, $40,000 award designed to support a young investigator, instructor, research associate or equivalent who currently holds a federal or nonfederal career development award devoted to conducting research related to digestive cancer.

Round out 2016 by preparing for a 2017 AGA Research Foundation grant. Eight grants are currently open for both established and young investigators, but all will close in January 2017. Make sure you’re prepared to submit your application before the deadline.

Complete information about these and other research awards is available on gastro.org. All recipients will be acknowledged at the Research Recognition Celebration at Digestive Disease Week® 2017 (www.ddw.org) in Chicago, IL.

Jan 6. 2017

- The AGA-Elsevier Gut Microbiome Pilot Research Award will provide $25,000 to support pilot research projects pertaining to the gut microbiome.

- The AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award is a 1-year grant providing young investigators, instructors, research associates, or equivalents $25,000 to support pilot research projects in gastroenterology- or hepatology-related areas.

- The AGA-Medtronic Research & Development Pilot Award in Technology grants $31,000 for 1 year to investigators to support the research and development of novel devices or technologies that will potentially impact the diagnosis or treatment of digestive disease.

Jan. 13, 2017

- The AGA-Rome Foundation Functional GI and Motility Disorders Pilot Research Award offers $50,000 for 1 year to early-stage investigators, established investigators, postdoctoral research fellows and combined research and clinical fellows to support pilot research projects pertaining to functional GI and motility disorders.

- The AGA Microbiome Junior Investigator Research Award is a 2-year award of $60,000 for junior investigators engaged in basic, translational, clinical, or health services research related to the gut microbiome.

- The AGA-Pfizer Pilot Research Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease is a 1-year, $30,000 award offered to established and young investigators to support pilot research projects related to IBD.

Jan. 20, 2017

- The AGA-June & Donald O. Castell, MD, Esophageal Clinical Research Award is a 1-year, $25,000 grant that provides research or salary support for junior faculty involved in clinical research in esophageal diseases.

- The AGA-Caroline Craig Augustyn & Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer is a 1-year, $40,000 award designed to support a young investigator, instructor, research associate or equivalent who currently holds a federal or nonfederal career development award devoted to conducting research related to digestive cancer.

Round out 2016 by preparing for a 2017 AGA Research Foundation grant. Eight grants are currently open for both established and young investigators, but all will close in January 2017. Make sure you’re prepared to submit your application before the deadline.

Complete information about these and other research awards is available on gastro.org. All recipients will be acknowledged at the Research Recognition Celebration at Digestive Disease Week® 2017 (www.ddw.org) in Chicago, IL.

Jan 6. 2017

- The AGA-Elsevier Gut Microbiome Pilot Research Award will provide $25,000 to support pilot research projects pertaining to the gut microbiome.

- The AGA-Elsevier Pilot Research Award is a 1-year grant providing young investigators, instructors, research associates, or equivalents $25,000 to support pilot research projects in gastroenterology- or hepatology-related areas.

- The AGA-Medtronic Research & Development Pilot Award in Technology grants $31,000 for 1 year to investigators to support the research and development of novel devices or technologies that will potentially impact the diagnosis or treatment of digestive disease.

Jan. 13, 2017

- The AGA-Rome Foundation Functional GI and Motility Disorders Pilot Research Award offers $50,000 for 1 year to early-stage investigators, established investigators, postdoctoral research fellows and combined research and clinical fellows to support pilot research projects pertaining to functional GI and motility disorders.

- The AGA Microbiome Junior Investigator Research Award is a 2-year award of $60,000 for junior investigators engaged in basic, translational, clinical, or health services research related to the gut microbiome.

- The AGA-Pfizer Pilot Research Award in Inflammatory Bowel Disease is a 1-year, $30,000 award offered to established and young investigators to support pilot research projects related to IBD.

Jan. 20, 2017

- The AGA-June & Donald O. Castell, MD, Esophageal Clinical Research Award is a 1-year, $25,000 grant that provides research or salary support for junior faculty involved in clinical research in esophageal diseases.

- The AGA-Caroline Craig Augustyn & Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer is a 1-year, $40,000 award designed to support a young investigator, instructor, research associate or equivalent who currently holds a federal or nonfederal career development award devoted to conducting research related to digestive cancer.

Memorial and honorary gifts: A special tribute

Did you know you can honor a family member, friend, or colleague whose life has been touched by GI research or celebrate a special occasion such as a birthday while supporting the work of our mission through a gift to the AGA Research Foundation? Your gift will honor a loved one or yourself and support the AGA Research Awards Program, while giving you a tax benefit:

- Giving now or later. Any charitable gift can be made in honor or memory of someone.

- A gift today. An outright gift will help fund the AGA Research Awards Program. Your gift will assist in furthering basic digestive disease research, which can ultimately advance research into all digestive diseases. The financial benefits include an income tax deduction and possible elimination of capital gains tax. A cash gift of $25,000 or more qualifies for membership in the AGA Legacy Society, which recognizes the foundation’s most generous individual donors.

- A gift through your will or living trust. You can include a bequest in your will or living trust stating that a specific asset, certain dollar amount, or more commonly a percentage of your estate will pass to the AGA Research Foundation at your death in honor of your loved one. A gift of $50,000 or more in your will qualifies for membership in the AGA Legacy Society.

- Named DDW Sessions. A named DDW session is established with a minimum gift of $125,000 over the course of 5 years or through an irrevocable planned gift. Gifts of cash, appreciated securities, life insurance, or property are gift vehicles that may be used to establish a named session. Donors will be eligible for naming recognition of a DDW AGA Institute Council session for 10 years. A gift at that level will qualifies for membership in the AGA Legacy Society.

Your next step

An honorary gift is a wonderful way to acknowledge someone’s vision for the future. To learn more about ways to recognize your honoree, visit our website at www.gastro.org/contribute or contact Harmony Excellent at 301-272-1602 or [email protected].

Did you know you can honor a family member, friend, or colleague whose life has been touched by GI research or celebrate a special occasion such as a birthday while supporting the work of our mission through a gift to the AGA Research Foundation? Your gift will honor a loved one or yourself and support the AGA Research Awards Program, while giving you a tax benefit:

- Giving now or later. Any charitable gift can be made in honor or memory of someone.

- A gift today. An outright gift will help fund the AGA Research Awards Program. Your gift will assist in furthering basic digestive disease research, which can ultimately advance research into all digestive diseases. The financial benefits include an income tax deduction and possible elimination of capital gains tax. A cash gift of $25,000 or more qualifies for membership in the AGA Legacy Society, which recognizes the foundation’s most generous individual donors.

- A gift through your will or living trust. You can include a bequest in your will or living trust stating that a specific asset, certain dollar amount, or more commonly a percentage of your estate will pass to the AGA Research Foundation at your death in honor of your loved one. A gift of $50,000 or more in your will qualifies for membership in the AGA Legacy Society.

- Named DDW Sessions. A named DDW session is established with a minimum gift of $125,000 over the course of 5 years or through an irrevocable planned gift. Gifts of cash, appreciated securities, life insurance, or property are gift vehicles that may be used to establish a named session. Donors will be eligible for naming recognition of a DDW AGA Institute Council session for 10 years. A gift at that level will qualifies for membership in the AGA Legacy Society.

Your next step

An honorary gift is a wonderful way to acknowledge someone’s vision for the future. To learn more about ways to recognize your honoree, visit our website at www.gastro.org/contribute or contact Harmony Excellent at 301-272-1602 or [email protected].

Did you know you can honor a family member, friend, or colleague whose life has been touched by GI research or celebrate a special occasion such as a birthday while supporting the work of our mission through a gift to the AGA Research Foundation? Your gift will honor a loved one or yourself and support the AGA Research Awards Program, while giving you a tax benefit:

- Giving now or later. Any charitable gift can be made in honor or memory of someone.

- A gift today. An outright gift will help fund the AGA Research Awards Program. Your gift will assist in furthering basic digestive disease research, which can ultimately advance research into all digestive diseases. The financial benefits include an income tax deduction and possible elimination of capital gains tax. A cash gift of $25,000 or more qualifies for membership in the AGA Legacy Society, which recognizes the foundation’s most generous individual donors.

- A gift through your will or living trust. You can include a bequest in your will or living trust stating that a specific asset, certain dollar amount, or more commonly a percentage of your estate will pass to the AGA Research Foundation at your death in honor of your loved one. A gift of $50,000 or more in your will qualifies for membership in the AGA Legacy Society.

- Named DDW Sessions. A named DDW session is established with a minimum gift of $125,000 over the course of 5 years or through an irrevocable planned gift. Gifts of cash, appreciated securities, life insurance, or property are gift vehicles that may be used to establish a named session. Donors will be eligible for naming recognition of a DDW AGA Institute Council session for 10 years. A gift at that level will qualifies for membership in the AGA Legacy Society.

Your next step

An honorary gift is a wonderful way to acknowledge someone’s vision for the future. To learn more about ways to recognize your honoree, visit our website at www.gastro.org/contribute or contact Harmony Excellent at 301-272-1602 or [email protected].

Elizabeth A. Thiele, MD, PhD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Child, adolescent autism patients visiting EDs in higher numbers

NEW YORK – Emergency departments are seeing more pediatric and adolescent patients with autism spectrum disorder, and are struggling to meet their needs, experts say.

At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, researchers presented results from studies attempting to quantify and better understand the uptick in ED visits, while clinicians shared strategies aimed at improving care in a setting that, nearly all agreed, presents unique obstacles for treating children with ASD.

Bright lights, excess noise, frequently changing care staff, and a lack of training in nonverbal communication strategies were among the problems the clinicians highlighted.

“There’s been a huge increase in recent years in the number of children with ASD that are coming into the ED because of either behavioral crises or general pediatric medical concerns that require us to intervene,” said Eron Y. Friedlaender, MD, MPH, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). “Yet, we struggle to offer kids with challenging behaviors or communication vulnerabilities the same standard of care that we’re used to offering.”

John J. McGonigle, PhD, head of the autism center at the University of Pittsburgh, noted that incidents tied to safety issues, such as disruptive behavior, aggression, and self-injury, were occurring among young ASD patients in the ED. In 2015, he said, Pennsylvania’s statewide patient safety data reporting system reviewed hospital records from 2004 to 2014 and recorded 138 events in the ED involving patients with ASD, 86 of them involving children and adolescents.

Dr. McGonigle said that such incidents, often accompanied by use of restraints, can be reduced through better training, and that ED practitioners and staff can be shown how to help calm patients and to provide the kind of simple, clear communication required to diagnose and treat them effectively. He showed excerpts from a training video produced at his institution to illustrate those strategies.

Patients with ASD should be moved away from bright fluorescent lights, and excess medical equipment and noise – ideally to a sensory room, Dr. McGonigle said – and given toys or other comforting activities appropriate to their interests. The number of people in and out of a patient’s room should be limited, and providers always should knock first on a door and wait for an answer, and introduce themselves by name, whether or not the child is able to respond.

Clinicians should recruit caregivers to help question patients, keep questions to a yes-no format, and not insist on eye contact. A “first-then” approach should be used to explain any intervention, describing the intervention and then an age-appropriate reward to follow. Interventions, even noninvasive ones, can be modeled or demonstrated first on caregivers.

Psychiatric crises are an important driver of ED visits among ASD patients, but crisis behavior should not be assumed to have a psychiatric cause, Dr. McGonigle stressed. Behavior mimicking a psychiatric episode “could be triggered by stomachache, ear infection, bowel obstruction, [urinary tract infection], hyper- or hypoglycemia.”

Communicating about pain is particularly challenging in patients with ASD, Dr. McGonigle said. The usual pain scales used in the pediatric ED rely on representations of facial expressions. These should be replaced by demonstrations using toys, tablet computers, or drawings to identify sources of pain, with a caregiver present to help.

Finding barriers to care

Dr. Friedlaender described a pilot study she and her colleagues conducted in her institution’s sedation unit that was designed to help them understand the barriers to optimal care for ASD patients, and to find ways around them. Many of the studies the investigators consulted “came from the dental literature, where there is a significant number of special-needs kids who need support during procedural care. [Dentists] were among the first to publish on how to make this a reasonable experience.”

One key insight gleaned from this literature, Dr. Friedlaender said, was that a simple screening question – whether the child could sit still for a haircut – proved sensitive in indicating a need for accommodation.

The CHOP researchers created a three-question universal screening tool that schedulers asked of all caregivers when a child presented to the ED. In addition to asking whether the child could sit still, schedulers asked whether he or she had a behavioral diagnosis or special communication needs. Of 458 families who completed the screening, 96 answered positively to at least one of the questions, and 79, or 17% of the cohort, indicated a behavioral diagnosis.

Such information previously had been missed, Dr. Friedlaender said, because “many families didn’t consider autism part of a medical history – if we didn’t ask about it, they didn’t share it.”

Her group also conducted a study on the effectiveness of self-reported pain scales in 43 verbal ASD children aged 6-17 who had undergone surgical procedures. Dr. Friedlaender said she suspected that it was impractical to ask children with ASD to use only pictures of facial expressions to indicate their pain.

The subjects were asked to circle images of faces with expressions corresponding to their pain. They also were asked to locate their pain by drawing it on tablet computers, and given poker chips to represent their degree of pain, with one chip the least and four the most. Caregivers were recruited to assist with questioning and interpreting responses.

All children in the study were able to describe and locate their pain. “We learned that there isn’t one universal pain tool that works for all kids,” Dr. Friedlaender said, “but that facial expressions and body language don’t often match pain scores” in ASD children. The study also revealed that parent or caregiver mediation is helpful in discerning the location and intensity of pain.

Why ED use is high

Other research presented at AACAP sought to grasp the scope of, and reasons behind, the increase in ASD youth seen in hospital emergency departments.

Michael J. Murray, MD, of Pennsylvania State University in Hershey, found using commercial insurance data from large employers showing that ED visits increased from 3% in 2005 to nearly 16% in 2013 among youth diagnosed with ASD, while a non-ASD comparison cohort saw a far more consistent rate of ED visits across the same time period, of about 3%. Adolescents with ASD were nearly five times more likely to have had an ED visit than were non-ASD adolescents (95% confidence interval, 4.678-4.875).

Dr. Murray said in an interview that the ASD cohort identified in his study “was smaller than it should have been,” compared with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention prevalence data. One likely reason is that not all the insurers had to cover ASD in the first years of the study period. Dr. Murray said he thinks a new study using public insurance data might provide a fuller picture.

Dr. Murray and colleagues’ study, which looked at youth aged 12-21, revealed that being older increased the likelihood of an ED visit. “We think it may have to do with the whole transition out of school,” he said. “This is the first generation with ASD that’s accustomed to having good school-based supports.” The transition to adulthood “is a really important time, and that’s when we’re pulling away from them.”

Sarah Lytle, MD, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, presented a literature review of ASD youth in the ED from 2006 through 2015. Dr. Lytle found that children with ASD were more likely to visit the ED than were those without ASD. In addition, the review showed a higher proportion of ED visits for psychiatric problems (13% of visits vs. 2% for non-ASD youth). Youth with ASD were more likely to be admitted to a psychiatric unit or medically boarded in the ED, she found. They also were more likely to have public insurance.

Dr. Lytle’s study drew from a dozen published studies in different age groups (subjects ranged from 0 to 24 years across studies). Though it was difficult to draw conclusions related to which saw the highest ED use, one study found the risk of ED use higher in adolescents, compared with younger children, she said. “One thing I see clinically is that when kids hit the age of 12, pediatric psychiatric units often won’t take them,” she said, as children are physically bigger and may be harder to manage. “And then they’re cycled into the ED,” she said.

Creating the ‘ASD care pathway’

Clinicians from New York shared their experiences designing and implementing an autism care pathway within the state’s only pediatric psychiatric emergency department.

At NYU Health and Hospitals/Bellevue, a public hospital, clinicians found themselves struggling to manage ASD patients, who comprise between 10% and 20% of children seen. “Most of our staff, and even our child psychiatrists, had previously had very little experience working with kids with autism, and that was true for most of our child psychiatrists as well,” said Ruth S. Gerson, MD, who oversees the hospital’s Children’s Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program.

The ASD patients “were in crisis all the time, and having constant behavioral outbursts,” said Beryl J. Filton, PhD. The team responded by developing an autism-specific care pathway for the ED and inpatient units, with a 4-hour training course for all staff members.

The pathway begins with a tip sheet for providers conducting the initial evaluation in the ED. Providers “ask questions specific to symptoms of autism: Does the child have words? How much do they understand? Do they communicate in other ways that are nonverbal? Then we talk about the child’s warning signs, triggers, preferred activities and rewards,” Dr. Filton said. This allows providers to gather information up front that can be used during the ED stay.

Picture books and visual communication boards are used to create a visual schedule for patients, so that they know what to expect, and staff have been trained to communicate through gesturing, modeling, and physical guidance, she said. “First-then” verbal and visual prompts are used before any intervention, including noninvasive interventions, and patients are put on a schedule of rewards as regular as every 15 minutes. They also are engaged in scheduled “motor breaks,” or brief periods of physical activity.

Dr. Filton, like the other providers, emphasized the importance of decreasing excess stimulation around patients with ASD and communicating coping options to them nonverbally. “We talk a lot with staff when patients are getting agitated about giving space and waiting,” she said. “One important thing to recognize is that these patients can take longer after an episode of agitation to return to baseline. So we talk with staff about being on high alert for even a couple hours after an agitated episode to keep demands low and rewards high.”

Many of the strategies and principles that have worked at Bellevue can be generalized to other settings, Dr. Filton said. “Using more than verbal communication, gesturing, visual supports cuing patients, and having reward systems” are effective anywhere for managing patients with autism, she said. The main challenge, she added, is achieving consistency, “making sure all the staff know the same information about the patient.”

Dr. Gerson said some of her team’s challenges come from being part of a public institution serving a low-income community with fragmented health care delivery. “A number of families that are coming in in crisis may not have known that their child had autism,” she said. “We see many who have never been formally diagnosed – even teenagers. Or the child has the diagnosis, but no one helped the family get the services they’re legally eligible for,” she said. “And then the family comes in to the ED and says: ‘We need you to fix all this.’ ”

What ED providers can do, she said, is use the improved assessment tools, and communication and coping strategies outlined in the pathway to “focus on determining the immediate crisis – whether there is change from the child’s usual behaviors, and what’s the pattern of that change.” While youth with ASD have higher rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders, “statistically that’s less likely to be the case in the ED than the stuff that plagues all of us: stomachaches, toothaches, constipation, or psychosocial stressors, such as changes at home or at school.”

One of the goals in creating the ASD care pathway, Dr. Gerson said, was to avoid unnecessary hospitalizations. “We’ve changed our assessment, and really drilled down to determine what hospitalization can and cannot accomplish,” so that only the children likely to benefit stay.

“At the same time, we have to make sure that when we discharge, we’re not leaving families with nothing, that we’re setting them up to receive services and resources to stabilize and support them in the community.”

NEW YORK – Emergency departments are seeing more pediatric and adolescent patients with autism spectrum disorder, and are struggling to meet their needs, experts say.

At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, researchers presented results from studies attempting to quantify and better understand the uptick in ED visits, while clinicians shared strategies aimed at improving care in a setting that, nearly all agreed, presents unique obstacles for treating children with ASD.

Bright lights, excess noise, frequently changing care staff, and a lack of training in nonverbal communication strategies were among the problems the clinicians highlighted.

“There’s been a huge increase in recent years in the number of children with ASD that are coming into the ED because of either behavioral crises or general pediatric medical concerns that require us to intervene,” said Eron Y. Friedlaender, MD, MPH, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). “Yet, we struggle to offer kids with challenging behaviors or communication vulnerabilities the same standard of care that we’re used to offering.”

John J. McGonigle, PhD, head of the autism center at the University of Pittsburgh, noted that incidents tied to safety issues, such as disruptive behavior, aggression, and self-injury, were occurring among young ASD patients in the ED. In 2015, he said, Pennsylvania’s statewide patient safety data reporting system reviewed hospital records from 2004 to 2014 and recorded 138 events in the ED involving patients with ASD, 86 of them involving children and adolescents.

Dr. McGonigle said that such incidents, often accompanied by use of restraints, can be reduced through better training, and that ED practitioners and staff can be shown how to help calm patients and to provide the kind of simple, clear communication required to diagnose and treat them effectively. He showed excerpts from a training video produced at his institution to illustrate those strategies.

Patients with ASD should be moved away from bright fluorescent lights, and excess medical equipment and noise – ideally to a sensory room, Dr. McGonigle said – and given toys or other comforting activities appropriate to their interests. The number of people in and out of a patient’s room should be limited, and providers always should knock first on a door and wait for an answer, and introduce themselves by name, whether or not the child is able to respond.

Clinicians should recruit caregivers to help question patients, keep questions to a yes-no format, and not insist on eye contact. A “first-then” approach should be used to explain any intervention, describing the intervention and then an age-appropriate reward to follow. Interventions, even noninvasive ones, can be modeled or demonstrated first on caregivers.

Psychiatric crises are an important driver of ED visits among ASD patients, but crisis behavior should not be assumed to have a psychiatric cause, Dr. McGonigle stressed. Behavior mimicking a psychiatric episode “could be triggered by stomachache, ear infection, bowel obstruction, [urinary tract infection], hyper- or hypoglycemia.”

Communicating about pain is particularly challenging in patients with ASD, Dr. McGonigle said. The usual pain scales used in the pediatric ED rely on representations of facial expressions. These should be replaced by demonstrations using toys, tablet computers, or drawings to identify sources of pain, with a caregiver present to help.

Finding barriers to care

Dr. Friedlaender described a pilot study she and her colleagues conducted in her institution’s sedation unit that was designed to help them understand the barriers to optimal care for ASD patients, and to find ways around them. Many of the studies the investigators consulted “came from the dental literature, where there is a significant number of special-needs kids who need support during procedural care. [Dentists] were among the first to publish on how to make this a reasonable experience.”

One key insight gleaned from this literature, Dr. Friedlaender said, was that a simple screening question – whether the child could sit still for a haircut – proved sensitive in indicating a need for accommodation.

The CHOP researchers created a three-question universal screening tool that schedulers asked of all caregivers when a child presented to the ED. In addition to asking whether the child could sit still, schedulers asked whether he or she had a behavioral diagnosis or special communication needs. Of 458 families who completed the screening, 96 answered positively to at least one of the questions, and 79, or 17% of the cohort, indicated a behavioral diagnosis.

Such information previously had been missed, Dr. Friedlaender said, because “many families didn’t consider autism part of a medical history – if we didn’t ask about it, they didn’t share it.”

Her group also conducted a study on the effectiveness of self-reported pain scales in 43 verbal ASD children aged 6-17 who had undergone surgical procedures. Dr. Friedlaender said she suspected that it was impractical to ask children with ASD to use only pictures of facial expressions to indicate their pain.

The subjects were asked to circle images of faces with expressions corresponding to their pain. They also were asked to locate their pain by drawing it on tablet computers, and given poker chips to represent their degree of pain, with one chip the least and four the most. Caregivers were recruited to assist with questioning and interpreting responses.

All children in the study were able to describe and locate their pain. “We learned that there isn’t one universal pain tool that works for all kids,” Dr. Friedlaender said, “but that facial expressions and body language don’t often match pain scores” in ASD children. The study also revealed that parent or caregiver mediation is helpful in discerning the location and intensity of pain.

Why ED use is high

Other research presented at AACAP sought to grasp the scope of, and reasons behind, the increase in ASD youth seen in hospital emergency departments.

Michael J. Murray, MD, of Pennsylvania State University in Hershey, found using commercial insurance data from large employers showing that ED visits increased from 3% in 2005 to nearly 16% in 2013 among youth diagnosed with ASD, while a non-ASD comparison cohort saw a far more consistent rate of ED visits across the same time period, of about 3%. Adolescents with ASD were nearly five times more likely to have had an ED visit than were non-ASD adolescents (95% confidence interval, 4.678-4.875).

Dr. Murray said in an interview that the ASD cohort identified in his study “was smaller than it should have been,” compared with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention prevalence data. One likely reason is that not all the insurers had to cover ASD in the first years of the study period. Dr. Murray said he thinks a new study using public insurance data might provide a fuller picture.

Dr. Murray and colleagues’ study, which looked at youth aged 12-21, revealed that being older increased the likelihood of an ED visit. “We think it may have to do with the whole transition out of school,” he said. “This is the first generation with ASD that’s accustomed to having good school-based supports.” The transition to adulthood “is a really important time, and that’s when we’re pulling away from them.”

Sarah Lytle, MD, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, presented a literature review of ASD youth in the ED from 2006 through 2015. Dr. Lytle found that children with ASD were more likely to visit the ED than were those without ASD. In addition, the review showed a higher proportion of ED visits for psychiatric problems (13% of visits vs. 2% for non-ASD youth). Youth with ASD were more likely to be admitted to a psychiatric unit or medically boarded in the ED, she found. They also were more likely to have public insurance.

Dr. Lytle’s study drew from a dozen published studies in different age groups (subjects ranged from 0 to 24 years across studies). Though it was difficult to draw conclusions related to which saw the highest ED use, one study found the risk of ED use higher in adolescents, compared with younger children, she said. “One thing I see clinically is that when kids hit the age of 12, pediatric psychiatric units often won’t take them,” she said, as children are physically bigger and may be harder to manage. “And then they’re cycled into the ED,” she said.

Creating the ‘ASD care pathway’

Clinicians from New York shared their experiences designing and implementing an autism care pathway within the state’s only pediatric psychiatric emergency department.

At NYU Health and Hospitals/Bellevue, a public hospital, clinicians found themselves struggling to manage ASD patients, who comprise between 10% and 20% of children seen. “Most of our staff, and even our child psychiatrists, had previously had very little experience working with kids with autism, and that was true for most of our child psychiatrists as well,” said Ruth S. Gerson, MD, who oversees the hospital’s Children’s Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program.

The ASD patients “were in crisis all the time, and having constant behavioral outbursts,” said Beryl J. Filton, PhD. The team responded by developing an autism-specific care pathway for the ED and inpatient units, with a 4-hour training course for all staff members.

The pathway begins with a tip sheet for providers conducting the initial evaluation in the ED. Providers “ask questions specific to symptoms of autism: Does the child have words? How much do they understand? Do they communicate in other ways that are nonverbal? Then we talk about the child’s warning signs, triggers, preferred activities and rewards,” Dr. Filton said. This allows providers to gather information up front that can be used during the ED stay.

Picture books and visual communication boards are used to create a visual schedule for patients, so that they know what to expect, and staff have been trained to communicate through gesturing, modeling, and physical guidance, she said. “First-then” verbal and visual prompts are used before any intervention, including noninvasive interventions, and patients are put on a schedule of rewards as regular as every 15 minutes. They also are engaged in scheduled “motor breaks,” or brief periods of physical activity.

Dr. Filton, like the other providers, emphasized the importance of decreasing excess stimulation around patients with ASD and communicating coping options to them nonverbally. “We talk a lot with staff when patients are getting agitated about giving space and waiting,” she said. “One important thing to recognize is that these patients can take longer after an episode of agitation to return to baseline. So we talk with staff about being on high alert for even a couple hours after an agitated episode to keep demands low and rewards high.”

Many of the strategies and principles that have worked at Bellevue can be generalized to other settings, Dr. Filton said. “Using more than verbal communication, gesturing, visual supports cuing patients, and having reward systems” are effective anywhere for managing patients with autism, she said. The main challenge, she added, is achieving consistency, “making sure all the staff know the same information about the patient.”

Dr. Gerson said some of her team’s challenges come from being part of a public institution serving a low-income community with fragmented health care delivery. “A number of families that are coming in in crisis may not have known that their child had autism,” she said. “We see many who have never been formally diagnosed – even teenagers. Or the child has the diagnosis, but no one helped the family get the services they’re legally eligible for,” she said. “And then the family comes in to the ED and says: ‘We need you to fix all this.’ ”

What ED providers can do, she said, is use the improved assessment tools, and communication and coping strategies outlined in the pathway to “focus on determining the immediate crisis – whether there is change from the child’s usual behaviors, and what’s the pattern of that change.” While youth with ASD have higher rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders, “statistically that’s less likely to be the case in the ED than the stuff that plagues all of us: stomachaches, toothaches, constipation, or psychosocial stressors, such as changes at home or at school.”

One of the goals in creating the ASD care pathway, Dr. Gerson said, was to avoid unnecessary hospitalizations. “We’ve changed our assessment, and really drilled down to determine what hospitalization can and cannot accomplish,” so that only the children likely to benefit stay.

“At the same time, we have to make sure that when we discharge, we’re not leaving families with nothing, that we’re setting them up to receive services and resources to stabilize and support them in the community.”

NEW YORK – Emergency departments are seeing more pediatric and adolescent patients with autism spectrum disorder, and are struggling to meet their needs, experts say.

At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, researchers presented results from studies attempting to quantify and better understand the uptick in ED visits, while clinicians shared strategies aimed at improving care in a setting that, nearly all agreed, presents unique obstacles for treating children with ASD.

Bright lights, excess noise, frequently changing care staff, and a lack of training in nonverbal communication strategies were among the problems the clinicians highlighted.

“There’s been a huge increase in recent years in the number of children with ASD that are coming into the ED because of either behavioral crises or general pediatric medical concerns that require us to intervene,” said Eron Y. Friedlaender, MD, MPH, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). “Yet, we struggle to offer kids with challenging behaviors or communication vulnerabilities the same standard of care that we’re used to offering.”

John J. McGonigle, PhD, head of the autism center at the University of Pittsburgh, noted that incidents tied to safety issues, such as disruptive behavior, aggression, and self-injury, were occurring among young ASD patients in the ED. In 2015, he said, Pennsylvania’s statewide patient safety data reporting system reviewed hospital records from 2004 to 2014 and recorded 138 events in the ED involving patients with ASD, 86 of them involving children and adolescents.

Dr. McGonigle said that such incidents, often accompanied by use of restraints, can be reduced through better training, and that ED practitioners and staff can be shown how to help calm patients and to provide the kind of simple, clear communication required to diagnose and treat them effectively. He showed excerpts from a training video produced at his institution to illustrate those strategies.

Patients with ASD should be moved away from bright fluorescent lights, and excess medical equipment and noise – ideally to a sensory room, Dr. McGonigle said – and given toys or other comforting activities appropriate to their interests. The number of people in and out of a patient’s room should be limited, and providers always should knock first on a door and wait for an answer, and introduce themselves by name, whether or not the child is able to respond.

Clinicians should recruit caregivers to help question patients, keep questions to a yes-no format, and not insist on eye contact. A “first-then” approach should be used to explain any intervention, describing the intervention and then an age-appropriate reward to follow. Interventions, even noninvasive ones, can be modeled or demonstrated first on caregivers.

Psychiatric crises are an important driver of ED visits among ASD patients, but crisis behavior should not be assumed to have a psychiatric cause, Dr. McGonigle stressed. Behavior mimicking a psychiatric episode “could be triggered by stomachache, ear infection, bowel obstruction, [urinary tract infection], hyper- or hypoglycemia.”

Communicating about pain is particularly challenging in patients with ASD, Dr. McGonigle said. The usual pain scales used in the pediatric ED rely on representations of facial expressions. These should be replaced by demonstrations using toys, tablet computers, or drawings to identify sources of pain, with a caregiver present to help.

Finding barriers to care

Dr. Friedlaender described a pilot study she and her colleagues conducted in her institution’s sedation unit that was designed to help them understand the barriers to optimal care for ASD patients, and to find ways around them. Many of the studies the investigators consulted “came from the dental literature, where there is a significant number of special-needs kids who need support during procedural care. [Dentists] were among the first to publish on how to make this a reasonable experience.”

One key insight gleaned from this literature, Dr. Friedlaender said, was that a simple screening question – whether the child could sit still for a haircut – proved sensitive in indicating a need for accommodation.

The CHOP researchers created a three-question universal screening tool that schedulers asked of all caregivers when a child presented to the ED. In addition to asking whether the child could sit still, schedulers asked whether he or she had a behavioral diagnosis or special communication needs. Of 458 families who completed the screening, 96 answered positively to at least one of the questions, and 79, or 17% of the cohort, indicated a behavioral diagnosis.

Such information previously had been missed, Dr. Friedlaender said, because “many families didn’t consider autism part of a medical history – if we didn’t ask about it, they didn’t share it.”

Her group also conducted a study on the effectiveness of self-reported pain scales in 43 verbal ASD children aged 6-17 who had undergone surgical procedures. Dr. Friedlaender said she suspected that it was impractical to ask children with ASD to use only pictures of facial expressions to indicate their pain.

The subjects were asked to circle images of faces with expressions corresponding to their pain. They also were asked to locate their pain by drawing it on tablet computers, and given poker chips to represent their degree of pain, with one chip the least and four the most. Caregivers were recruited to assist with questioning and interpreting responses.

All children in the study were able to describe and locate their pain. “We learned that there isn’t one universal pain tool that works for all kids,” Dr. Friedlaender said, “but that facial expressions and body language don’t often match pain scores” in ASD children. The study also revealed that parent or caregiver mediation is helpful in discerning the location and intensity of pain.

Why ED use is high

Other research presented at AACAP sought to grasp the scope of, and reasons behind, the increase in ASD youth seen in hospital emergency departments.

Michael J. Murray, MD, of Pennsylvania State University in Hershey, found using commercial insurance data from large employers showing that ED visits increased from 3% in 2005 to nearly 16% in 2013 among youth diagnosed with ASD, while a non-ASD comparison cohort saw a far more consistent rate of ED visits across the same time period, of about 3%. Adolescents with ASD were nearly five times more likely to have had an ED visit than were non-ASD adolescents (95% confidence interval, 4.678-4.875).

Dr. Murray said in an interview that the ASD cohort identified in his study “was smaller than it should have been,” compared with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention prevalence data. One likely reason is that not all the insurers had to cover ASD in the first years of the study period. Dr. Murray said he thinks a new study using public insurance data might provide a fuller picture.

Dr. Murray and colleagues’ study, which looked at youth aged 12-21, revealed that being older increased the likelihood of an ED visit. “We think it may have to do with the whole transition out of school,” he said. “This is the first generation with ASD that’s accustomed to having good school-based supports.” The transition to adulthood “is a really important time, and that’s when we’re pulling away from them.”

Sarah Lytle, MD, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, presented a literature review of ASD youth in the ED from 2006 through 2015. Dr. Lytle found that children with ASD were more likely to visit the ED than were those without ASD. In addition, the review showed a higher proportion of ED visits for psychiatric problems (13% of visits vs. 2% for non-ASD youth). Youth with ASD were more likely to be admitted to a psychiatric unit or medically boarded in the ED, she found. They also were more likely to have public insurance.

Dr. Lytle’s study drew from a dozen published studies in different age groups (subjects ranged from 0 to 24 years across studies). Though it was difficult to draw conclusions related to which saw the highest ED use, one study found the risk of ED use higher in adolescents, compared with younger children, she said. “One thing I see clinically is that when kids hit the age of 12, pediatric psychiatric units often won’t take them,” she said, as children are physically bigger and may be harder to manage. “And then they’re cycled into the ED,” she said.

Creating the ‘ASD care pathway’

Clinicians from New York shared their experiences designing and implementing an autism care pathway within the state’s only pediatric psychiatric emergency department.

At NYU Health and Hospitals/Bellevue, a public hospital, clinicians found themselves struggling to manage ASD patients, who comprise between 10% and 20% of children seen. “Most of our staff, and even our child psychiatrists, had previously had very little experience working with kids with autism, and that was true for most of our child psychiatrists as well,” said Ruth S. Gerson, MD, who oversees the hospital’s Children’s Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program.

The ASD patients “were in crisis all the time, and having constant behavioral outbursts,” said Beryl J. Filton, PhD. The team responded by developing an autism-specific care pathway for the ED and inpatient units, with a 4-hour training course for all staff members.

The pathway begins with a tip sheet for providers conducting the initial evaluation in the ED. Providers “ask questions specific to symptoms of autism: Does the child have words? How much do they understand? Do they communicate in other ways that are nonverbal? Then we talk about the child’s warning signs, triggers, preferred activities and rewards,” Dr. Filton said. This allows providers to gather information up front that can be used during the ED stay.

Picture books and visual communication boards are used to create a visual schedule for patients, so that they know what to expect, and staff have been trained to communicate through gesturing, modeling, and physical guidance, she said. “First-then” verbal and visual prompts are used before any intervention, including noninvasive interventions, and patients are put on a schedule of rewards as regular as every 15 minutes. They also are engaged in scheduled “motor breaks,” or brief periods of physical activity.

Dr. Filton, like the other providers, emphasized the importance of decreasing excess stimulation around patients with ASD and communicating coping options to them nonverbally. “We talk a lot with staff when patients are getting agitated about giving space and waiting,” she said. “One important thing to recognize is that these patients can take longer after an episode of agitation to return to baseline. So we talk with staff about being on high alert for even a couple hours after an agitated episode to keep demands low and rewards high.”

Many of the strategies and principles that have worked at Bellevue can be generalized to other settings, Dr. Filton said. “Using more than verbal communication, gesturing, visual supports cuing patients, and having reward systems” are effective anywhere for managing patients with autism, she said. The main challenge, she added, is achieving consistency, “making sure all the staff know the same information about the patient.”

Dr. Gerson said some of her team’s challenges come from being part of a public institution serving a low-income community with fragmented health care delivery. “A number of families that are coming in in crisis may not have known that their child had autism,” she said. “We see many who have never been formally diagnosed – even teenagers. Or the child has the diagnosis, but no one helped the family get the services they’re legally eligible for,” she said. “And then the family comes in to the ED and says: ‘We need you to fix all this.’ ”

What ED providers can do, she said, is use the improved assessment tools, and communication and coping strategies outlined in the pathway to “focus on determining the immediate crisis – whether there is change from the child’s usual behaviors, and what’s the pattern of that change.” While youth with ASD have higher rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders, “statistically that’s less likely to be the case in the ED than the stuff that plagues all of us: stomachaches, toothaches, constipation, or psychosocial stressors, such as changes at home or at school.”

One of the goals in creating the ASD care pathway, Dr. Gerson said, was to avoid unnecessary hospitalizations. “We’ve changed our assessment, and really drilled down to determine what hospitalization can and cannot accomplish,” so that only the children likely to benefit stay.

“At the same time, we have to make sure that when we discharge, we’re not leaving families with nothing, that we’re setting them up to receive services and resources to stabilize and support them in the community.”

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AACAP 2016

Potential Operating Room Fire Hazard of Bone Cement

Approximately 600 cases of operating room (OR) fires are reported annually.1 The incidence of OR fires in the United States equals that of wrong-site surgeries, and 20% of cases have associated morbidity.1,2 The estimated mortality rate is 1 to 2 cases per year.3-5 The most commonly involved anatomical regions are the airway (33%) and the face (28%).4 Most surgical fires are reported in anesthetized patients with open oxygen delivery systems during head, neck, and upper chest surgeries; electrosurgical instruments are the ignition source in 90% of these cases.6 Despite extensive fire safety education and training, complete elimination of OR fires still has not been achieved.

Each fire requires an ignition source, a fuel source, and an oxidizer.7 In the OR, the 2 most common oxidizers are oxygen and nitrous oxide. Head and neck surgeries have a high concentration of these gases near the working field and therefore a higher risk and incidence of fires. Furthermore, surgical drapes and equipment (eg, closed or semi-closed breathing systems, masks) may potentiate this risk by reducing ventilation in areas where gases can accumulate and ignite. Ignition sources provide the energy that starts fires; common sources are electrocautery, lasers, fiber-optic light cords, drills/burrs, and defibrillator paddles. Fires are propagated by fuel sources, which encompass any flammable material, including tracheal tubes, sponges, alcohol-based solutions, hair, gastrointestinal tract gases, gloves, and packaging materials.8 Of note, alcohol-based skin-preparation agents emit flammable vapors that can ignite.9-14 Before draping or exposure to an ignition source, chlorhexidine gluconate-based preparations must be allowed to dry for at least 3 minutes after application to hairless skin and up to 1 hour after application to hair.15 Inadequate drying poses a risk of fire.10We present the case of an OR fire ignited by electrocautery near freshly applied bone cement. No patient information is disclosed in this report.

Case Report

Our patient was evaluated in clinic and scheduled for total knee arthroplasty (TKA). All preoperative safety checklists and time-out procedures were followed and documented at the start of surgery. The TKA was performed with a standard medial patellar arthrotomy. Tourniquet control was used after Esmarch exsanguination. The surgery proceeded uneventfully until just after the bone cement was applied to the tibial surface. The surgeon was using a Bovie to resect residual lateral meniscus tissue when a fire instantaneously erupted within the joint space. Fortunately, the surgeon quickly suffocated the fire with a dry towel. The ignited bone cement was removed, and the patient was examined. There was no injury to surrounding tissue or joint space. Surgery was resumed with application of new bone cement to the tibial surface. The artificial joint was then successfully implanted and the case completed without further incident. The patient was discharged from the hospital and followed up as an outpatient without any postoperative complications.

Discussion

Bone cement, which is commonly used in artificial joint anchoring, craniofacial reconstruction, and vertebroplasty, has liquid and powder components. The liquid monomer methyl methacrylate (MMA) is colorless and flammable and has a distinct odor.16 Exposure to heat or light can prematurely polymerize MMA, requiring the addition of hydroquinone to inhibit the reaction.16 The powder polymethylmethacrylate affords excellent structural support, radiopacity, and facility of use.17 Dibenzoyl peroxide and N,N-dimethyl-p-toluidine are added to the powder to facilitate the polymerization reaction at room temperature (ie, cold curing of cement). Premature application of unpolymerized cement increases the risk of fire from the volatile liquid component.

In the OR, bone cement is prepared by mixing together its powder and liquid components.18 The reaction is exothermic polymerization. The liquid is highly volatile and flammable in both liquid and vapor states.16,19 The vapors are denser than air and can concentrate in poorly ventilated areas. The OR and the application site must be adequately ventilated to eliminate any pockets of vapor accumulation.16 A vacuum mixer can be used to minimize fume exposure, enhance cement strength, and reduce fire risk while combining the 2 components.

MMA’s flash point, the temperature at which the fumes could ignite in the presence of an ignition source, is 10.5ºC. The auto-ignition point, the temperature at which MMA spontaneously combusts, is 421ºC.20 The OR is usually warmer than the flash point temperature, but the electrocautery tip can generate up to 1200ºC of heat.21 Therefore, bone cement is a potential fire hazard, and use of Bovies or other ignition sources in its vicinity must be avoided.

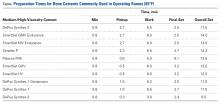

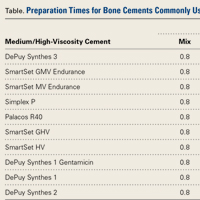

The Table lists the recommended times for preparing various bone cement products.22,23Mix time is the time needed to combine the liquid and powder into a homogenous putty.

For OR fires, the standard guidelines for rapid containment and safety apply. These guidelines are detailed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists.8 Briefly, delivery of all airway gases to the patient is discontinued. Any burning material is removed and extinguished by the OR staff.1 Carbon dioxide fire extinguishers are used to put out any patient fires and minimize the risk of thermal injury. (Water-mist fire extinguishers can contaminate surgical wounds and present an electric shock hazard with surgical devices and should be avoided.24) If a fire occurs in a patient’s airway, the tracheal tube is removed, and airway patency is maintained with use of other invasive or noninvasive techniques. Often, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation without supplemental oxygen is used until the fire is controlled and the patient is safe. Once the patient fire is controlled, ventilation is restarted, and the patient is evacuated from the OR and away from any other hazards, as required. Last, the patient is physically examined for any injuries and treated.24 Specific to TKA, the procedure is resumed after removal of all bone cement, inspection of the operative site, and treatment of any fire-related injuries.

We have reported the case of an OR fire during TKA. Appropriate selection and use of bone cement products, proper assessment of set time, and avoidance of electrocautery near cement application sites may dramatically reduce associated fire risks.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E512-E514. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Hart SR, Yajnik A, Ashford J, Springer R, Harvey S. Operating room fire safety. Ochsner J. 2011;11(1):37-42.

2. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Operating Room Fires; Caplan RA, Barker SJ, Connis RT, et al. Practice advisory for the prevention and management of operating room fires. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):786-801.

3. Bruley M. Surgical fires: perioperative communication is essential to prevent this rare but devastating complication. Qual Saf HealthCare. 2004;13(6):467-471.

4. Daane SP, Toth BA. Fire in the operating room: principles and prevention. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(5):73e-75e.

5. Rinder CS. Fire safety in the operating room. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2008;21(6):790-795.

6. Mathias JM. Fast action, team coordination critical when surgical fires occur. OR Manager. 2013;29(11):9-10.

7. Culp WC Jr, Kimbrough BA, Luna S. Flammability of surgical drapes and materials in varying concentrations of oxygen. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(4):770-776.

8. Apfelbaum JL, Caplan RA, Barker SJ, et al; American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Operating Room Fires. Practice advisory for the prevention and management of operating room fires: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Operating Room Fires. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):271-290.

9. Barker SJ, Polson JS. Fire in the operating room: a case report and laboratory study. Anesth Analg. 2001;93(4):960-965.

10. Fire hazard created by the misuse of DuraPrep solution. Health Devices. 1998;27(11):400-402.

11. Hurt TL, Schweich PJ. Do not get burned: preventing iatrogenic fires and burns in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(4):255-259.

12. Prasad R, Quezado Z, St Andre A, O’Grady NP. Fires in the operating room and intensive care unit: awareness is the key to prevention. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(1):172-174.

13. Shah SC. Correspondence: operating room flash fire. Anesth Analg. 1974;53(2):288.

14. Tooher R, Maddern GJ, Simpson J. Surgical fires and alcohol-based skin preparations. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(5):382-385.

15. Using ChloraPrep™ products and the skin prep portfolio. http://www.carefusion.com/medical-products/infection-prevention/skin-preparation/using-chloraprep.aspx. Accessed October 7, 2016.16. DePuy CMW. DePuy Orthopaedic Gentamicin Bone Cements. Blackpool, United Kingdom: DePuy International Ltd; 2008.

17. Dall’Oca C, Maluta T, Cavani F, et al. The biocompatibility of porous vs non-porous bone cements: a new methodological approach. Eur J Histochem. 2014;58(2):2255.

18. Zimmer Biomet. Bone Cement: Biomet Cement and Cementing Systems. http://www.biomet.com/wps/portal/internet/Biomet/Healthcare-Professionals/products/orthopedics. 2014. Accessed October 7, 2016.

19. Sigma-Aldrich. Methyl methacrylate. http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/aldrich/w400201?lang=en®ion=US. Accessed October 7, 2016.

20. DePuy Synthes. Unmedicated bone cements MSDS. Blackpool, United Kingdom: DePuy International Ltd. http://msdsdigital.com/unmedicated-bone-cements-msds. Accessed October 7, 2016.

21. Mir MR, Sun GS, Wang CM. Electrocautery. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2111163-overview#showall. Accessed October 7, 2016.

22. DePuy Synthes. Bone cement time setting.

23. Berry DJ, Lieberman JR, eds. Surgery of the Hip. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2011.

24. ECRI Institute. Surgical Fire Prevention. https://www.ecri.org/Accident_Investigation/Pages/Surgical-Fire-Prevention.aspx. 2014. Accessed October 7, 2016.

Approximately 600 cases of operating room (OR) fires are reported annually.1 The incidence of OR fires in the United States equals that of wrong-site surgeries, and 20% of cases have associated morbidity.1,2 The estimated mortality rate is 1 to 2 cases per year.3-5 The most commonly involved anatomical regions are the airway (33%) and the face (28%).4 Most surgical fires are reported in anesthetized patients with open oxygen delivery systems during head, neck, and upper chest surgeries; electrosurgical instruments are the ignition source in 90% of these cases.6 Despite extensive fire safety education and training, complete elimination of OR fires still has not been achieved.

Each fire requires an ignition source, a fuel source, and an oxidizer.7 In the OR, the 2 most common oxidizers are oxygen and nitrous oxide. Head and neck surgeries have a high concentration of these gases near the working field and therefore a higher risk and incidence of fires. Furthermore, surgical drapes and equipment (eg, closed or semi-closed breathing systems, masks) may potentiate this risk by reducing ventilation in areas where gases can accumulate and ignite. Ignition sources provide the energy that starts fires; common sources are electrocautery, lasers, fiber-optic light cords, drills/burrs, and defibrillator paddles. Fires are propagated by fuel sources, which encompass any flammable material, including tracheal tubes, sponges, alcohol-based solutions, hair, gastrointestinal tract gases, gloves, and packaging materials.8 Of note, alcohol-based skin-preparation agents emit flammable vapors that can ignite.9-14 Before draping or exposure to an ignition source, chlorhexidine gluconate-based preparations must be allowed to dry for at least 3 minutes after application to hairless skin and up to 1 hour after application to hair.15 Inadequate drying poses a risk of fire.10We present the case of an OR fire ignited by electrocautery near freshly applied bone cement. No patient information is disclosed in this report.

Case Report

Our patient was evaluated in clinic and scheduled for total knee arthroplasty (TKA). All preoperative safety checklists and time-out procedures were followed and documented at the start of surgery. The TKA was performed with a standard medial patellar arthrotomy. Tourniquet control was used after Esmarch exsanguination. The surgery proceeded uneventfully until just after the bone cement was applied to the tibial surface. The surgeon was using a Bovie to resect residual lateral meniscus tissue when a fire instantaneously erupted within the joint space. Fortunately, the surgeon quickly suffocated the fire with a dry towel. The ignited bone cement was removed, and the patient was examined. There was no injury to surrounding tissue or joint space. Surgery was resumed with application of new bone cement to the tibial surface. The artificial joint was then successfully implanted and the case completed without further incident. The patient was discharged from the hospital and followed up as an outpatient without any postoperative complications.

Discussion

Bone cement, which is commonly used in artificial joint anchoring, craniofacial reconstruction, and vertebroplasty, has liquid and powder components. The liquid monomer methyl methacrylate (MMA) is colorless and flammable and has a distinct odor.16 Exposure to heat or light can prematurely polymerize MMA, requiring the addition of hydroquinone to inhibit the reaction.16 The powder polymethylmethacrylate affords excellent structural support, radiopacity, and facility of use.17 Dibenzoyl peroxide and N,N-dimethyl-p-toluidine are added to the powder to facilitate the polymerization reaction at room temperature (ie, cold curing of cement). Premature application of unpolymerized cement increases the risk of fire from the volatile liquid component.

In the OR, bone cement is prepared by mixing together its powder and liquid components.18 The reaction is exothermic polymerization. The liquid is highly volatile and flammable in both liquid and vapor states.16,19 The vapors are denser than air and can concentrate in poorly ventilated areas. The OR and the application site must be adequately ventilated to eliminate any pockets of vapor accumulation.16 A vacuum mixer can be used to minimize fume exposure, enhance cement strength, and reduce fire risk while combining the 2 components.

MMA’s flash point, the temperature at which the fumes could ignite in the presence of an ignition source, is 10.5ºC. The auto-ignition point, the temperature at which MMA spontaneously combusts, is 421ºC.20 The OR is usually warmer than the flash point temperature, but the electrocautery tip can generate up to 1200ºC of heat.21 Therefore, bone cement is a potential fire hazard, and use of Bovies or other ignition sources in its vicinity must be avoided.

The Table lists the recommended times for preparing various bone cement products.22,23Mix time is the time needed to combine the liquid and powder into a homogenous putty.

For OR fires, the standard guidelines for rapid containment and safety apply. These guidelines are detailed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists.8 Briefly, delivery of all airway gases to the patient is discontinued. Any burning material is removed and extinguished by the OR staff.1 Carbon dioxide fire extinguishers are used to put out any patient fires and minimize the risk of thermal injury. (Water-mist fire extinguishers can contaminate surgical wounds and present an electric shock hazard with surgical devices and should be avoided.24) If a fire occurs in a patient’s airway, the tracheal tube is removed, and airway patency is maintained with use of other invasive or noninvasive techniques. Often, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation without supplemental oxygen is used until the fire is controlled and the patient is safe. Once the patient fire is controlled, ventilation is restarted, and the patient is evacuated from the OR and away from any other hazards, as required. Last, the patient is physically examined for any injuries and treated.24 Specific to TKA, the procedure is resumed after removal of all bone cement, inspection of the operative site, and treatment of any fire-related injuries.

We have reported the case of an OR fire during TKA. Appropriate selection and use of bone cement products, proper assessment of set time, and avoidance of electrocautery near cement application sites may dramatically reduce associated fire risks.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E512-E514. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Approximately 600 cases of operating room (OR) fires are reported annually.1 The incidence of OR fires in the United States equals that of wrong-site surgeries, and 20% of cases have associated morbidity.1,2 The estimated mortality rate is 1 to 2 cases per year.3-5 The most commonly involved anatomical regions are the airway (33%) and the face (28%).4 Most surgical fires are reported in anesthetized patients with open oxygen delivery systems during head, neck, and upper chest surgeries; electrosurgical instruments are the ignition source in 90% of these cases.6 Despite extensive fire safety education and training, complete elimination of OR fires still has not been achieved.

Each fire requires an ignition source, a fuel source, and an oxidizer.7 In the OR, the 2 most common oxidizers are oxygen and nitrous oxide. Head and neck surgeries have a high concentration of these gases near the working field and therefore a higher risk and incidence of fires. Furthermore, surgical drapes and equipment (eg, closed or semi-closed breathing systems, masks) may potentiate this risk by reducing ventilation in areas where gases can accumulate and ignite. Ignition sources provide the energy that starts fires; common sources are electrocautery, lasers, fiber-optic light cords, drills/burrs, and defibrillator paddles. Fires are propagated by fuel sources, which encompass any flammable material, including tracheal tubes, sponges, alcohol-based solutions, hair, gastrointestinal tract gases, gloves, and packaging materials.8 Of note, alcohol-based skin-preparation agents emit flammable vapors that can ignite.9-14 Before draping or exposure to an ignition source, chlorhexidine gluconate-based preparations must be allowed to dry for at least 3 minutes after application to hairless skin and up to 1 hour after application to hair.15 Inadequate drying poses a risk of fire.10We present the case of an OR fire ignited by electrocautery near freshly applied bone cement. No patient information is disclosed in this report.

Case Report

Our patient was evaluated in clinic and scheduled for total knee arthroplasty (TKA). All preoperative safety checklists and time-out procedures were followed and documented at the start of surgery. The TKA was performed with a standard medial patellar arthrotomy. Tourniquet control was used after Esmarch exsanguination. The surgery proceeded uneventfully until just after the bone cement was applied to the tibial surface. The surgeon was using a Bovie to resect residual lateral meniscus tissue when a fire instantaneously erupted within the joint space. Fortunately, the surgeon quickly suffocated the fire with a dry towel. The ignited bone cement was removed, and the patient was examined. There was no injury to surrounding tissue or joint space. Surgery was resumed with application of new bone cement to the tibial surface. The artificial joint was then successfully implanted and the case completed without further incident. The patient was discharged from the hospital and followed up as an outpatient without any postoperative complications.

Discussion

Bone cement, which is commonly used in artificial joint anchoring, craniofacial reconstruction, and vertebroplasty, has liquid and powder components. The liquid monomer methyl methacrylate (MMA) is colorless and flammable and has a distinct odor.16 Exposure to heat or light can prematurely polymerize MMA, requiring the addition of hydroquinone to inhibit the reaction.16 The powder polymethylmethacrylate affords excellent structural support, radiopacity, and facility of use.17 Dibenzoyl peroxide and N,N-dimethyl-p-toluidine are added to the powder to facilitate the polymerization reaction at room temperature (ie, cold curing of cement). Premature application of unpolymerized cement increases the risk of fire from the volatile liquid component.

In the OR, bone cement is prepared by mixing together its powder and liquid components.18 The reaction is exothermic polymerization. The liquid is highly volatile and flammable in both liquid and vapor states.16,19 The vapors are denser than air and can concentrate in poorly ventilated areas. The OR and the application site must be adequately ventilated to eliminate any pockets of vapor accumulation.16 A vacuum mixer can be used to minimize fume exposure, enhance cement strength, and reduce fire risk while combining the 2 components.

MMA’s flash point, the temperature at which the fumes could ignite in the presence of an ignition source, is 10.5ºC. The auto-ignition point, the temperature at which MMA spontaneously combusts, is 421ºC.20 The OR is usually warmer than the flash point temperature, but the electrocautery tip can generate up to 1200ºC of heat.21 Therefore, bone cement is a potential fire hazard, and use of Bovies or other ignition sources in its vicinity must be avoided.

The Table lists the recommended times for preparing various bone cement products.22,23Mix time is the time needed to combine the liquid and powder into a homogenous putty.

For OR fires, the standard guidelines for rapid containment and safety apply. These guidelines are detailed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists.8 Briefly, delivery of all airway gases to the patient is discontinued. Any burning material is removed and extinguished by the OR staff.1 Carbon dioxide fire extinguishers are used to put out any patient fires and minimize the risk of thermal injury. (Water-mist fire extinguishers can contaminate surgical wounds and present an electric shock hazard with surgical devices and should be avoided.24) If a fire occurs in a patient’s airway, the tracheal tube is removed, and airway patency is maintained with use of other invasive or noninvasive techniques. Often, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation without supplemental oxygen is used until the fire is controlled and the patient is safe. Once the patient fire is controlled, ventilation is restarted, and the patient is evacuated from the OR and away from any other hazards, as required. Last, the patient is physically examined for any injuries and treated.24 Specific to TKA, the procedure is resumed after removal of all bone cement, inspection of the operative site, and treatment of any fire-related injuries.

We have reported the case of an OR fire during TKA. Appropriate selection and use of bone cement products, proper assessment of set time, and avoidance of electrocautery near cement application sites may dramatically reduce associated fire risks.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E512-E514. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Hart SR, Yajnik A, Ashford J, Springer R, Harvey S. Operating room fire safety. Ochsner J. 2011;11(1):37-42.

2. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Operating Room Fires; Caplan RA, Barker SJ, Connis RT, et al. Practice advisory for the prevention and management of operating room fires. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):786-801.

3. Bruley M. Surgical fires: perioperative communication is essential to prevent this rare but devastating complication. Qual Saf HealthCare. 2004;13(6):467-471.

4. Daane SP, Toth BA. Fire in the operating room: principles and prevention. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(5):73e-75e.

5. Rinder CS. Fire safety in the operating room. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2008;21(6):790-795.

6. Mathias JM. Fast action, team coordination critical when surgical fires occur. OR Manager. 2013;29(11):9-10.

7. Culp WC Jr, Kimbrough BA, Luna S. Flammability of surgical drapes and materials in varying concentrations of oxygen. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(4):770-776.

8. Apfelbaum JL, Caplan RA, Barker SJ, et al; American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Operating Room Fires. Practice advisory for the prevention and management of operating room fires: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Operating Room Fires. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):271-290.

9. Barker SJ, Polson JS. Fire in the operating room: a case report and laboratory study. Anesth Analg. 2001;93(4):960-965.

10. Fire hazard created by the misuse of DuraPrep solution. Health Devices. 1998;27(11):400-402.

11. Hurt TL, Schweich PJ. Do not get burned: preventing iatrogenic fires and burns in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(4):255-259.

12. Prasad R, Quezado Z, St Andre A, O’Grady NP. Fires in the operating room and intensive care unit: awareness is the key to prevention. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(1):172-174.

13. Shah SC. Correspondence: operating room flash fire. Anesth Analg. 1974;53(2):288.

14. Tooher R, Maddern GJ, Simpson J. Surgical fires and alcohol-based skin preparations. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(5):382-385.