User login

Cardiovascular disease: Innovations in devices and techniques

Supplement Editor:

Maan A. Fares, MD

Contents

Cardiovascular disease: Innovations in devices and techniques

Maan A. Fares

Transcatheter mitral valve replacement: A frontier in cardiac intervention

Amar Krishnaswamy, Stephanie Mick, Jose Navia, A. Marc Gillinov, E. Murrat Tuzcu, and Samir R. Kapadia

Bioresorbable stents: The future of Interventional cardiology?

Stephen G. Ellis and Haris Riaz

Leadless cardiac pacing: What primary care providers and non-EP cardiologists should know

Erich L. Kiehl and Daniel J. Cantillon

PCSK9 inhibition: A promise fulfilled?

Khendi White, Chaitra Mohan, and Michael Rocco

Fibromuscular dysplasia: Advances in understanding and management

Ellen K. Brinza and Heather L. Gornik

Supplement Editor:

Maan A. Fares, MD

Contents

Cardiovascular disease: Innovations in devices and techniques

Maan A. Fares

Transcatheter mitral valve replacement: A frontier in cardiac intervention

Amar Krishnaswamy, Stephanie Mick, Jose Navia, A. Marc Gillinov, E. Murrat Tuzcu, and Samir R. Kapadia

Bioresorbable stents: The future of Interventional cardiology?

Stephen G. Ellis and Haris Riaz

Leadless cardiac pacing: What primary care providers and non-EP cardiologists should know

Erich L. Kiehl and Daniel J. Cantillon

PCSK9 inhibition: A promise fulfilled?

Khendi White, Chaitra Mohan, and Michael Rocco

Fibromuscular dysplasia: Advances in understanding and management

Ellen K. Brinza and Heather L. Gornik

Supplement Editor:

Maan A. Fares, MD

Contents

Cardiovascular disease: Innovations in devices and techniques

Maan A. Fares

Transcatheter mitral valve replacement: A frontier in cardiac intervention

Amar Krishnaswamy, Stephanie Mick, Jose Navia, A. Marc Gillinov, E. Murrat Tuzcu, and Samir R. Kapadia

Bioresorbable stents: The future of Interventional cardiology?

Stephen G. Ellis and Haris Riaz

Leadless cardiac pacing: What primary care providers and non-EP cardiologists should know

Erich L. Kiehl and Daniel J. Cantillon

PCSK9 inhibition: A promise fulfilled?

Khendi White, Chaitra Mohan, and Michael Rocco

Fibromuscular dysplasia: Advances in understanding and management

Ellen K. Brinza and Heather L. Gornik

Why ustekinumab dosing differs in Crohn’s disease

ORLANDO – Preclinical studies and years of clinical experience using the monoclonal antibody ustekinumab (Stelara, Janssen Biotech) in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis offer important clues to any gastroenterologist perplexed by the official Food and Drug Administration indication, dosing frequency, and intensity for Crohn’s disease. Phase II and phase III findings also reveal where the monoclonal antibody may offer particular advantages, compared with other agents.

“Ustekinumab landed in your lap in September. You’re probably all trying to figure out how to get the ID formulation paid for with insurance,” William J. Sanborn, MD, professor and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego, said at the Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases meeting. “But this is now the reality that you have this in your Crohn’s practice.”

The FDA approved ustekinumab to treat adults with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease who 1) failed or were intolerant to immune modulators or corticosteroids but did not fail tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers or 2) failed or were intolerant to one or more TNF blockers. Dr. Sanborn and colleagues observed a significant induction of clinical response in a subgroup of patients who previously failed a TNF blocker in an early efficacy study (Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1130-41). “This is where the idea of initially focusing on TNF failures came from,” he added at the meeting sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

Induction dosing in Crohn’s disease is intravenous versus subcutaneous in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, in part because of the same study. “It looked like relatively better bioavailability and relatively better effect with intravenous dosing,” Dr. Sanborn said. “In Crohn’s disease, it’s a completely different animal.”

Official induction dosing is approximately 6 mg/kg in three fixed doses according to patient weight in Crohn’s disease. The 6-mg/kg dose yielded the most consistent response, compared with 1-mg/kg or 3-mg/kg doses in a subsequent phase IIb study (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1519-28).

The most consistent induction results at weeks 6 and 8 were observed with 6 mg/kg ustekinumab versus 1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg.

Dr. Sanborn and coinvestigators also saw “numeric differences in drug versus placebo for remission at 6 and 8 weeks “but it was not that clear from the phase II trial what the remission efficacy was, so that needed more exploration to really understand.”

Another distinction for ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease is the approved maintenance dosing of 90 mg subcutaneously every 8 weeks versus a 12-week interval recommended for psoriasis. “Why so much more in Crohn’s disease, and is that necessary?” Dr. Sanborn asked.

Based on changes in C-reactive protein levels and a “rapid drop” in Crohn’s Disease Activity Index scores by 4 weeks, “clearly efficacy was there for induction,” he said. Ustekinumab has a “quick onset – analogous to the TNF blockers.”

“These were quite encouraging data, and paved the way to move on to phase III [studies],” Dr. Sanborn said. The preclinical studies up to this point focused on patients with Crohn’s disease who previously failed TNF blockers. However, “in clinical practice, we would be interested to know if it would work in anti-TNF naive or nonfailures as well.”

So two subsequent studies assessed safety and efficacy in a TNF blocker–failure population (UNITI-1 trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar;22 Suppl 1:S1) and a non-TNF failure population of patients who did fail previous conventional therapy such as steroids or immunomodulators (UNITI-2 trial).

Clinical response and remission steadily rose following induction up to a significant difference versus placebo at 8 weeks in the non–TNF failure population. “Remember, in the phase IIa study, the remission rates were not as clear-cut, so this really nails down this as a good drug in both patient populations,” Dr. Sanborn said.

To evaluate long-term maintenance, investigators rerandomized all participants in the UNITI-1 and UNITI-2 studies. They saw a 15% gain in clinical remission out to week 44, compared with placebo. Dr. Sanborn noted that ustekinumab has a relatively long half-life, so the difference in patients switched to placebo may not have been as striking. “In practice it’s important to know the on-time and off-time of this agent, and I think the clinical trials make that clear.”

The trials also show that 12-week dosing works, Dr. Sanborn said. “You see about 20% gain for every 8-week dosing. You get extra 5% or 10% extra on all outcome measures at 8 weeks, compared to 12 weeks dosing, with no difference in safety signals.” He added, “So more intensive dosing of 90 mg every 8 weeks is what ended up getting approved in the United States.”

Safety profile

So what does all the preclinical evidence suggest about safety of ustekinumab? The UNITI trials combined included more than 1,000 patients, and there were no deaths, Dr. Sanborn said. “Usually with TNF blockers in 1,000 patients you would see a few deaths.”

Patient withdrawals from the preclinical studies were also relatively low, Dr. Sanborn reported. “With ustekinumab monotherapy, drug withdrawal is only 3% or 4%, so it seems to be different from TNF blockers in that sense [too].”

In addition, the rates of adverse events were similar between placebo (83.5%) and ustekinumab’s combined every 8 week and every 12 week dosing groups through 44 weeks (81.0%), Dr. Sanborn said. The rates of serious adverse events were likewise similar, 15.0% and 11.0%, respectively. Reported malignancy included two cases of basal cell skin cancers, one in the placebo group and one in the every-8-week dosing group, he added.

“So all those black box warnings you’re used to worrying about with TNF blockers – serious infections, about opportunistic infections, malignancy – there is no black box warning with this agent around that.”

Dr. Sanborn noted that the FDA labeling reports infections. “We know Crohn’s disease patients are [also] getting azathioprine, steroids, methotrexate, so you will see some infections, but there wasn’t a consistent opportunistic infection signal.”

One case of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome is included on the labeling. Dr. Sanborn also put this in perspective: “With all the experience in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and the clinical trials [in IBD], there is just one case. So the relationship is not very clear.”

“The safety signals with ustekinumab are really very good. It seems to be an extremely safe agent – we really don’t see much in terms of infections,” Brian Feagan, MD, an internist and gastroenterologist at the University of Western Ontario in London, said in a separate presentation at the conference. “We don’t have a lot of long-term experience with ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease, but we have a lot of experience in psoriasis, and it’s a safe drug.”

“Ustekinumab may be our first really valid monotherapy, with less immunogenicity,” Dr. Feagan said.

ORLANDO – Preclinical studies and years of clinical experience using the monoclonal antibody ustekinumab (Stelara, Janssen Biotech) in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis offer important clues to any gastroenterologist perplexed by the official Food and Drug Administration indication, dosing frequency, and intensity for Crohn’s disease. Phase II and phase III findings also reveal where the monoclonal antibody may offer particular advantages, compared with other agents.

“Ustekinumab landed in your lap in September. You’re probably all trying to figure out how to get the ID formulation paid for with insurance,” William J. Sanborn, MD, professor and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego, said at the Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases meeting. “But this is now the reality that you have this in your Crohn’s practice.”

The FDA approved ustekinumab to treat adults with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease who 1) failed or were intolerant to immune modulators or corticosteroids but did not fail tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers or 2) failed or were intolerant to one or more TNF blockers. Dr. Sanborn and colleagues observed a significant induction of clinical response in a subgroup of patients who previously failed a TNF blocker in an early efficacy study (Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1130-41). “This is where the idea of initially focusing on TNF failures came from,” he added at the meeting sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

Induction dosing in Crohn’s disease is intravenous versus subcutaneous in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, in part because of the same study. “It looked like relatively better bioavailability and relatively better effect with intravenous dosing,” Dr. Sanborn said. “In Crohn’s disease, it’s a completely different animal.”

Official induction dosing is approximately 6 mg/kg in three fixed doses according to patient weight in Crohn’s disease. The 6-mg/kg dose yielded the most consistent response, compared with 1-mg/kg or 3-mg/kg doses in a subsequent phase IIb study (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1519-28).

The most consistent induction results at weeks 6 and 8 were observed with 6 mg/kg ustekinumab versus 1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg.

Dr. Sanborn and coinvestigators also saw “numeric differences in drug versus placebo for remission at 6 and 8 weeks “but it was not that clear from the phase II trial what the remission efficacy was, so that needed more exploration to really understand.”

Another distinction for ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease is the approved maintenance dosing of 90 mg subcutaneously every 8 weeks versus a 12-week interval recommended for psoriasis. “Why so much more in Crohn’s disease, and is that necessary?” Dr. Sanborn asked.

Based on changes in C-reactive protein levels and a “rapid drop” in Crohn’s Disease Activity Index scores by 4 weeks, “clearly efficacy was there for induction,” he said. Ustekinumab has a “quick onset – analogous to the TNF blockers.”

“These were quite encouraging data, and paved the way to move on to phase III [studies],” Dr. Sanborn said. The preclinical studies up to this point focused on patients with Crohn’s disease who previously failed TNF blockers. However, “in clinical practice, we would be interested to know if it would work in anti-TNF naive or nonfailures as well.”

So two subsequent studies assessed safety and efficacy in a TNF blocker–failure population (UNITI-1 trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar;22 Suppl 1:S1) and a non-TNF failure population of patients who did fail previous conventional therapy such as steroids or immunomodulators (UNITI-2 trial).

Clinical response and remission steadily rose following induction up to a significant difference versus placebo at 8 weeks in the non–TNF failure population. “Remember, in the phase IIa study, the remission rates were not as clear-cut, so this really nails down this as a good drug in both patient populations,” Dr. Sanborn said.

To evaluate long-term maintenance, investigators rerandomized all participants in the UNITI-1 and UNITI-2 studies. They saw a 15% gain in clinical remission out to week 44, compared with placebo. Dr. Sanborn noted that ustekinumab has a relatively long half-life, so the difference in patients switched to placebo may not have been as striking. “In practice it’s important to know the on-time and off-time of this agent, and I think the clinical trials make that clear.”

The trials also show that 12-week dosing works, Dr. Sanborn said. “You see about 20% gain for every 8-week dosing. You get extra 5% or 10% extra on all outcome measures at 8 weeks, compared to 12 weeks dosing, with no difference in safety signals.” He added, “So more intensive dosing of 90 mg every 8 weeks is what ended up getting approved in the United States.”

Safety profile

So what does all the preclinical evidence suggest about safety of ustekinumab? The UNITI trials combined included more than 1,000 patients, and there were no deaths, Dr. Sanborn said. “Usually with TNF blockers in 1,000 patients you would see a few deaths.”

Patient withdrawals from the preclinical studies were also relatively low, Dr. Sanborn reported. “With ustekinumab monotherapy, drug withdrawal is only 3% or 4%, so it seems to be different from TNF blockers in that sense [too].”

In addition, the rates of adverse events were similar between placebo (83.5%) and ustekinumab’s combined every 8 week and every 12 week dosing groups through 44 weeks (81.0%), Dr. Sanborn said. The rates of serious adverse events were likewise similar, 15.0% and 11.0%, respectively. Reported malignancy included two cases of basal cell skin cancers, one in the placebo group and one in the every-8-week dosing group, he added.

“So all those black box warnings you’re used to worrying about with TNF blockers – serious infections, about opportunistic infections, malignancy – there is no black box warning with this agent around that.”

Dr. Sanborn noted that the FDA labeling reports infections. “We know Crohn’s disease patients are [also] getting azathioprine, steroids, methotrexate, so you will see some infections, but there wasn’t a consistent opportunistic infection signal.”

One case of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome is included on the labeling. Dr. Sanborn also put this in perspective: “With all the experience in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and the clinical trials [in IBD], there is just one case. So the relationship is not very clear.”

“The safety signals with ustekinumab are really very good. It seems to be an extremely safe agent – we really don’t see much in terms of infections,” Brian Feagan, MD, an internist and gastroenterologist at the University of Western Ontario in London, said in a separate presentation at the conference. “We don’t have a lot of long-term experience with ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease, but we have a lot of experience in psoriasis, and it’s a safe drug.”

“Ustekinumab may be our first really valid monotherapy, with less immunogenicity,” Dr. Feagan said.

ORLANDO – Preclinical studies and years of clinical experience using the monoclonal antibody ustekinumab (Stelara, Janssen Biotech) in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis offer important clues to any gastroenterologist perplexed by the official Food and Drug Administration indication, dosing frequency, and intensity for Crohn’s disease. Phase II and phase III findings also reveal where the monoclonal antibody may offer particular advantages, compared with other agents.

“Ustekinumab landed in your lap in September. You’re probably all trying to figure out how to get the ID formulation paid for with insurance,” William J. Sanborn, MD, professor and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego, said at the Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases meeting. “But this is now the reality that you have this in your Crohn’s practice.”

The FDA approved ustekinumab to treat adults with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease who 1) failed or were intolerant to immune modulators or corticosteroids but did not fail tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers or 2) failed or were intolerant to one or more TNF blockers. Dr. Sanborn and colleagues observed a significant induction of clinical response in a subgroup of patients who previously failed a TNF blocker in an early efficacy study (Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1130-41). “This is where the idea of initially focusing on TNF failures came from,” he added at the meeting sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

Induction dosing in Crohn’s disease is intravenous versus subcutaneous in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, in part because of the same study. “It looked like relatively better bioavailability and relatively better effect with intravenous dosing,” Dr. Sanborn said. “In Crohn’s disease, it’s a completely different animal.”

Official induction dosing is approximately 6 mg/kg in three fixed doses according to patient weight in Crohn’s disease. The 6-mg/kg dose yielded the most consistent response, compared with 1-mg/kg or 3-mg/kg doses in a subsequent phase IIb study (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1519-28).

The most consistent induction results at weeks 6 and 8 were observed with 6 mg/kg ustekinumab versus 1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg.

Dr. Sanborn and coinvestigators also saw “numeric differences in drug versus placebo for remission at 6 and 8 weeks “but it was not that clear from the phase II trial what the remission efficacy was, so that needed more exploration to really understand.”

Another distinction for ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease is the approved maintenance dosing of 90 mg subcutaneously every 8 weeks versus a 12-week interval recommended for psoriasis. “Why so much more in Crohn’s disease, and is that necessary?” Dr. Sanborn asked.

Based on changes in C-reactive protein levels and a “rapid drop” in Crohn’s Disease Activity Index scores by 4 weeks, “clearly efficacy was there for induction,” he said. Ustekinumab has a “quick onset – analogous to the TNF blockers.”

“These were quite encouraging data, and paved the way to move on to phase III [studies],” Dr. Sanborn said. The preclinical studies up to this point focused on patients with Crohn’s disease who previously failed TNF blockers. However, “in clinical practice, we would be interested to know if it would work in anti-TNF naive or nonfailures as well.”

So two subsequent studies assessed safety and efficacy in a TNF blocker–failure population (UNITI-1 trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar;22 Suppl 1:S1) and a non-TNF failure population of patients who did fail previous conventional therapy such as steroids or immunomodulators (UNITI-2 trial).

Clinical response and remission steadily rose following induction up to a significant difference versus placebo at 8 weeks in the non–TNF failure population. “Remember, in the phase IIa study, the remission rates were not as clear-cut, so this really nails down this as a good drug in both patient populations,” Dr. Sanborn said.

To evaluate long-term maintenance, investigators rerandomized all participants in the UNITI-1 and UNITI-2 studies. They saw a 15% gain in clinical remission out to week 44, compared with placebo. Dr. Sanborn noted that ustekinumab has a relatively long half-life, so the difference in patients switched to placebo may not have been as striking. “In practice it’s important to know the on-time and off-time of this agent, and I think the clinical trials make that clear.”

The trials also show that 12-week dosing works, Dr. Sanborn said. “You see about 20% gain for every 8-week dosing. You get extra 5% or 10% extra on all outcome measures at 8 weeks, compared to 12 weeks dosing, with no difference in safety signals.” He added, “So more intensive dosing of 90 mg every 8 weeks is what ended up getting approved in the United States.”

Safety profile

So what does all the preclinical evidence suggest about safety of ustekinumab? The UNITI trials combined included more than 1,000 patients, and there were no deaths, Dr. Sanborn said. “Usually with TNF blockers in 1,000 patients you would see a few deaths.”

Patient withdrawals from the preclinical studies were also relatively low, Dr. Sanborn reported. “With ustekinumab monotherapy, drug withdrawal is only 3% or 4%, so it seems to be different from TNF blockers in that sense [too].”

In addition, the rates of adverse events were similar between placebo (83.5%) and ustekinumab’s combined every 8 week and every 12 week dosing groups through 44 weeks (81.0%), Dr. Sanborn said. The rates of serious adverse events were likewise similar, 15.0% and 11.0%, respectively. Reported malignancy included two cases of basal cell skin cancers, one in the placebo group and one in the every-8-week dosing group, he added.

“So all those black box warnings you’re used to worrying about with TNF blockers – serious infections, about opportunistic infections, malignancy – there is no black box warning with this agent around that.”

Dr. Sanborn noted that the FDA labeling reports infections. “We know Crohn’s disease patients are [also] getting azathioprine, steroids, methotrexate, so you will see some infections, but there wasn’t a consistent opportunistic infection signal.”

One case of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome is included on the labeling. Dr. Sanborn also put this in perspective: “With all the experience in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and the clinical trials [in IBD], there is just one case. So the relationship is not very clear.”

“The safety signals with ustekinumab are really very good. It seems to be an extremely safe agent – we really don’t see much in terms of infections,” Brian Feagan, MD, an internist and gastroenterologist at the University of Western Ontario in London, said in a separate presentation at the conference. “We don’t have a lot of long-term experience with ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease, but we have a lot of experience in psoriasis, and it’s a safe drug.”

“Ustekinumab may be our first really valid monotherapy, with less immunogenicity,” Dr. Feagan said.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AIBD 2016

Clinical Guidelines: Hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is pneumonia that presents at least 48 hours after admission to the hospital. In contrast, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), is pneumonia that clinically presents 48 hours after endotracheal intubation. Together, these are some of the most common hospital-acquired infections in the United States and pose a considerable burden on hospitals nationwide.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) recently updated their management guidelines for HAP and VAP with a goal of striking a balance between providing appropriate early antibiotic coverage and avoiding unnecessary treatment that can lead to adverse effects such as Clostridium difficile infections and development of antibiotic resistance.1 This update eliminated the concept of Healthcare Associated Pneumonia (HCAP), often used for patients in skilled care facilities, because newer evidence has shown that patients who had met these criteria did not have a higher incidence of multidrug resistant pathogens; rather, they have microbial etiologies and sensitivities that are similar to adults with community acquired pneumonia (CAP).

Hospital-acquired pneumonia

Reasons to cover for MRSA in HAP:

Risk factors:

• IV antibiotic treatment within 90 days

• Treatment in a unit where the prevalence of MRSA is greater than 20% or unknown

• Prior detection of MRSA by culture or nonculture screening (weaker risk factor)

High risk of mortality: • Septic shock

• Need for ventilator support

MRSA should be covered with use of either vancomycin or linezolid in these cases.

In addition, patients with HAP should be covered for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacilli. For patients with risk factors for pseudomonas or other gram-negative infection or a high risk for mortality, then two antipseudomonal antibiotics from different classes are recommended, such as piperacillin-tazobactam/tobramycin or cefepime/amikacin.

Use two antipseudomonal antibiotics in HAP if the patient has these risk factors:

Pseudomonas risk factors:

• IV antibiotic treatment within 90 days

• Structural lung disease increasing the risk of gram-negative infection (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis)

• High-quality gram stain from respiratory specimen showing predominant and numerous gram-negative bacilli

High risk of mortality:

• Septic shock

• Need for ventilator support

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

General management of VAP is similar to HAP in that empiric treatment should be tailored to the local distribution and susceptibilities of pathogens based on each hospital’s antibiogram. All regimens should cover for S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and other gram-negative bacilli based on the risk of mortality associated with the need for ventilator support. MSSA should be covered for VAP unless the patient has methicillin-resistant risk factors (see below).

MRSA should be covered for VAP if:

• Patient has had IV antibiotic use within past 90 days

• Hospital unit has greater than 10%-20% of S. aureus isolates are MRSA or MRSA prevalence unknown

Only one antipseudomonal agent should be used unless there are one of the following characteristics present, as described below.

Use two antipseudomonal agents in VAP if:

• Prior IV antibiotic use within 90 days

• Septic shock at time of VAP

• Acute respiratory distress syndrome preceding VAP

• 5 or more days of hospitalization prior to the occurrence of VAP

• Acute renal replacement therapy prior to VAP onset

• Greater than 10% of gram-negative isolates are resistant to an agent being considered for monotherapy

• Local antibiotic susceptibility rates unknown

In both HAP and VAP, antibiotics should be de-escalated to those with a narrower spectrum after initial empiric therapy, ideally within 72 hours and based on sputum or blood culture results. The guidelines support obtaining noninvasive sputum cultures in patients with VAP (endotracheal aspirates) and HAP (spontaneous expectoration, induced sputum, or nasotracheal suctioning in a patient who is unable to cooperate to produce a sputum sample). Patients who are improving clinically may be switched to appropriate oral therapy based on the susceptibility of an identified organism. Another key change is that of the standard duration of therapy. Previously, patients were treated for up to 2-3 weeks with antibiotics. The new IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend that patients should be treated with 7 days of antibiotics rather than a longer course.

The bottom line

Empiric therapy for HAP and VAP should be tailored to each hospital’s local pathogen distribution and antimicrobial susceptibilities, as detailed in an antibiogram. In HAP and VAP, empiric antibiotics should cover for S. aureus, but it only needs to target MRSA if risk factors are present, prevalence is greater than 20% or unknown, and – if HAP – a high risk of mortality. P. aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacilli should also be covered in empiric regimens. Dual antipseudomonal antibiotics is only recommended to be used in HAP if there are specific pseudomonal risk factors or a high risk of mortality. They should be used in VAP if there are multidrug-resistant risk factors present or there is a high/unknown prevalence of resistant organisms. All antibiotic regimens should be deescalated rather than maintained, and both HAP and VAP patients ought to be treated for 7 days.

References

1. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63(5):557-82.

2. Beardsley JR, Williamson JC, Johnson JW, Ohl CA, Karchmer TB, Bowton DL. Using local microbiologic data to develop institution-specific guidelines for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2006 Sep;130(3):787-93.

Dr. Botti is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program department of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia. Dr. Mills is assistant residency program director and assistant professor in the department of family and community medicine and department of physiology at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is pneumonia that presents at least 48 hours after admission to the hospital. In contrast, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), is pneumonia that clinically presents 48 hours after endotracheal intubation. Together, these are some of the most common hospital-acquired infections in the United States and pose a considerable burden on hospitals nationwide.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) recently updated their management guidelines for HAP and VAP with a goal of striking a balance between providing appropriate early antibiotic coverage and avoiding unnecessary treatment that can lead to adverse effects such as Clostridium difficile infections and development of antibiotic resistance.1 This update eliminated the concept of Healthcare Associated Pneumonia (HCAP), often used for patients in skilled care facilities, because newer evidence has shown that patients who had met these criteria did not have a higher incidence of multidrug resistant pathogens; rather, they have microbial etiologies and sensitivities that are similar to adults with community acquired pneumonia (CAP).

Hospital-acquired pneumonia

Reasons to cover for MRSA in HAP:

Risk factors:

• IV antibiotic treatment within 90 days

• Treatment in a unit where the prevalence of MRSA is greater than 20% or unknown

• Prior detection of MRSA by culture or nonculture screening (weaker risk factor)

High risk of mortality: • Septic shock

• Need for ventilator support

MRSA should be covered with use of either vancomycin or linezolid in these cases.

In addition, patients with HAP should be covered for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacilli. For patients with risk factors for pseudomonas or other gram-negative infection or a high risk for mortality, then two antipseudomonal antibiotics from different classes are recommended, such as piperacillin-tazobactam/tobramycin or cefepime/amikacin.

Use two antipseudomonal antibiotics in HAP if the patient has these risk factors:

Pseudomonas risk factors:

• IV antibiotic treatment within 90 days

• Structural lung disease increasing the risk of gram-negative infection (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis)

• High-quality gram stain from respiratory specimen showing predominant and numerous gram-negative bacilli

High risk of mortality:

• Septic shock

• Need for ventilator support

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

General management of VAP is similar to HAP in that empiric treatment should be tailored to the local distribution and susceptibilities of pathogens based on each hospital’s antibiogram. All regimens should cover for S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and other gram-negative bacilli based on the risk of mortality associated with the need for ventilator support. MSSA should be covered for VAP unless the patient has methicillin-resistant risk factors (see below).

MRSA should be covered for VAP if:

• Patient has had IV antibiotic use within past 90 days

• Hospital unit has greater than 10%-20% of S. aureus isolates are MRSA or MRSA prevalence unknown

Only one antipseudomonal agent should be used unless there are one of the following characteristics present, as described below.

Use two antipseudomonal agents in VAP if:

• Prior IV antibiotic use within 90 days

• Septic shock at time of VAP

• Acute respiratory distress syndrome preceding VAP

• 5 or more days of hospitalization prior to the occurrence of VAP

• Acute renal replacement therapy prior to VAP onset

• Greater than 10% of gram-negative isolates are resistant to an agent being considered for monotherapy

• Local antibiotic susceptibility rates unknown

In both HAP and VAP, antibiotics should be de-escalated to those with a narrower spectrum after initial empiric therapy, ideally within 72 hours and based on sputum or blood culture results. The guidelines support obtaining noninvasive sputum cultures in patients with VAP (endotracheal aspirates) and HAP (spontaneous expectoration, induced sputum, or nasotracheal suctioning in a patient who is unable to cooperate to produce a sputum sample). Patients who are improving clinically may be switched to appropriate oral therapy based on the susceptibility of an identified organism. Another key change is that of the standard duration of therapy. Previously, patients were treated for up to 2-3 weeks with antibiotics. The new IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend that patients should be treated with 7 days of antibiotics rather than a longer course.

The bottom line

Empiric therapy for HAP and VAP should be tailored to each hospital’s local pathogen distribution and antimicrobial susceptibilities, as detailed in an antibiogram. In HAP and VAP, empiric antibiotics should cover for S. aureus, but it only needs to target MRSA if risk factors are present, prevalence is greater than 20% or unknown, and – if HAP – a high risk of mortality. P. aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacilli should also be covered in empiric regimens. Dual antipseudomonal antibiotics is only recommended to be used in HAP if there are specific pseudomonal risk factors or a high risk of mortality. They should be used in VAP if there are multidrug-resistant risk factors present or there is a high/unknown prevalence of resistant organisms. All antibiotic regimens should be deescalated rather than maintained, and both HAP and VAP patients ought to be treated for 7 days.

References

1. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63(5):557-82.

2. Beardsley JR, Williamson JC, Johnson JW, Ohl CA, Karchmer TB, Bowton DL. Using local microbiologic data to develop institution-specific guidelines for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2006 Sep;130(3):787-93.

Dr. Botti is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program department of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia. Dr. Mills is assistant residency program director and assistant professor in the department of family and community medicine and department of physiology at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is pneumonia that presents at least 48 hours after admission to the hospital. In contrast, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), is pneumonia that clinically presents 48 hours after endotracheal intubation. Together, these are some of the most common hospital-acquired infections in the United States and pose a considerable burden on hospitals nationwide.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS) recently updated their management guidelines for HAP and VAP with a goal of striking a balance between providing appropriate early antibiotic coverage and avoiding unnecessary treatment that can lead to adverse effects such as Clostridium difficile infections and development of antibiotic resistance.1 This update eliminated the concept of Healthcare Associated Pneumonia (HCAP), often used for patients in skilled care facilities, because newer evidence has shown that patients who had met these criteria did not have a higher incidence of multidrug resistant pathogens; rather, they have microbial etiologies and sensitivities that are similar to adults with community acquired pneumonia (CAP).

Hospital-acquired pneumonia

Reasons to cover for MRSA in HAP:

Risk factors:

• IV antibiotic treatment within 90 days

• Treatment in a unit where the prevalence of MRSA is greater than 20% or unknown

• Prior detection of MRSA by culture or nonculture screening (weaker risk factor)

High risk of mortality: • Septic shock

• Need for ventilator support

MRSA should be covered with use of either vancomycin or linezolid in these cases.

In addition, patients with HAP should be covered for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacilli. For patients with risk factors for pseudomonas or other gram-negative infection or a high risk for mortality, then two antipseudomonal antibiotics from different classes are recommended, such as piperacillin-tazobactam/tobramycin or cefepime/amikacin.

Use two antipseudomonal antibiotics in HAP if the patient has these risk factors:

Pseudomonas risk factors:

• IV antibiotic treatment within 90 days

• Structural lung disease increasing the risk of gram-negative infection (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis)

• High-quality gram stain from respiratory specimen showing predominant and numerous gram-negative bacilli

High risk of mortality:

• Septic shock

• Need for ventilator support

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

General management of VAP is similar to HAP in that empiric treatment should be tailored to the local distribution and susceptibilities of pathogens based on each hospital’s antibiogram. All regimens should cover for S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and other gram-negative bacilli based on the risk of mortality associated with the need for ventilator support. MSSA should be covered for VAP unless the patient has methicillin-resistant risk factors (see below).

MRSA should be covered for VAP if:

• Patient has had IV antibiotic use within past 90 days

• Hospital unit has greater than 10%-20% of S. aureus isolates are MRSA or MRSA prevalence unknown

Only one antipseudomonal agent should be used unless there are one of the following characteristics present, as described below.

Use two antipseudomonal agents in VAP if:

• Prior IV antibiotic use within 90 days

• Septic shock at time of VAP

• Acute respiratory distress syndrome preceding VAP

• 5 or more days of hospitalization prior to the occurrence of VAP

• Acute renal replacement therapy prior to VAP onset

• Greater than 10% of gram-negative isolates are resistant to an agent being considered for monotherapy

• Local antibiotic susceptibility rates unknown

In both HAP and VAP, antibiotics should be de-escalated to those with a narrower spectrum after initial empiric therapy, ideally within 72 hours and based on sputum or blood culture results. The guidelines support obtaining noninvasive sputum cultures in patients with VAP (endotracheal aspirates) and HAP (spontaneous expectoration, induced sputum, or nasotracheal suctioning in a patient who is unable to cooperate to produce a sputum sample). Patients who are improving clinically may be switched to appropriate oral therapy based on the susceptibility of an identified organism. Another key change is that of the standard duration of therapy. Previously, patients were treated for up to 2-3 weeks with antibiotics. The new IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend that patients should be treated with 7 days of antibiotics rather than a longer course.

The bottom line

Empiric therapy for HAP and VAP should be tailored to each hospital’s local pathogen distribution and antimicrobial susceptibilities, as detailed in an antibiogram. In HAP and VAP, empiric antibiotics should cover for S. aureus, but it only needs to target MRSA if risk factors are present, prevalence is greater than 20% or unknown, and – if HAP – a high risk of mortality. P. aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacilli should also be covered in empiric regimens. Dual antipseudomonal antibiotics is only recommended to be used in HAP if there are specific pseudomonal risk factors or a high risk of mortality. They should be used in VAP if there are multidrug-resistant risk factors present or there is a high/unknown prevalence of resistant organisms. All antibiotic regimens should be deescalated rather than maintained, and both HAP and VAP patients ought to be treated for 7 days.

References

1. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63(5):557-82.

2. Beardsley JR, Williamson JC, Johnson JW, Ohl CA, Karchmer TB, Bowton DL. Using local microbiologic data to develop institution-specific guidelines for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2006 Sep;130(3):787-93.

Dr. Botti is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program department of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia. Dr. Mills is assistant residency program director and assistant professor in the department of family and community medicine and department of physiology at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Neurosurgical Subspecialty Bedside Guide Improves Nursing Confidence

The VA Portland Healthcare System (VAPHCS) is a 277-bed facility that serves more than 85,000 inpatient and 880,000 outpatient visits each year from veterans in Oregon and southwestern Washington. The VAPHCS consists of a main tertiary care VAMC with an acute medical and surgical facility that includes 30 beds serving qualifying veterans. Supported surgical specialties include urology, general surgery, vascular surgery, otolaryngology, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, cardiothoracic surgery, transplant surgery, and neurological surgery. Neurosurgical patients account for about 12% to 13% of annual surgical patients. The VAPHCS also is partnered with Oregon Health & Science University in the training of health care professionals, such as physicians and nurses.

The expectation at the VAPHCS is that medical-surgical nurses care for 4 to 5 concurrent patients, often from different surgical services. Caring for patients with different medical and surgical needs, variable ambulatory, swallowing, and elimination functions, and different physician teams can become confusing; even within a single surgical service, postoperative care due to procedure complexity, specificity of care orders, and the real possibility of medical catastrophe can seem overwhelming. Therefore, subspecialty nursing training poses a challenge that requires technical in-service and didactic education and allocation of resources.

Despite systems level subspecialty nursing training, medical emergencies identified at the bedside can be mismanaged.1 Errors in care can be due to an incomplete knowledge of the patient’s procedure and misunderstanding of positioning and activity limitations.

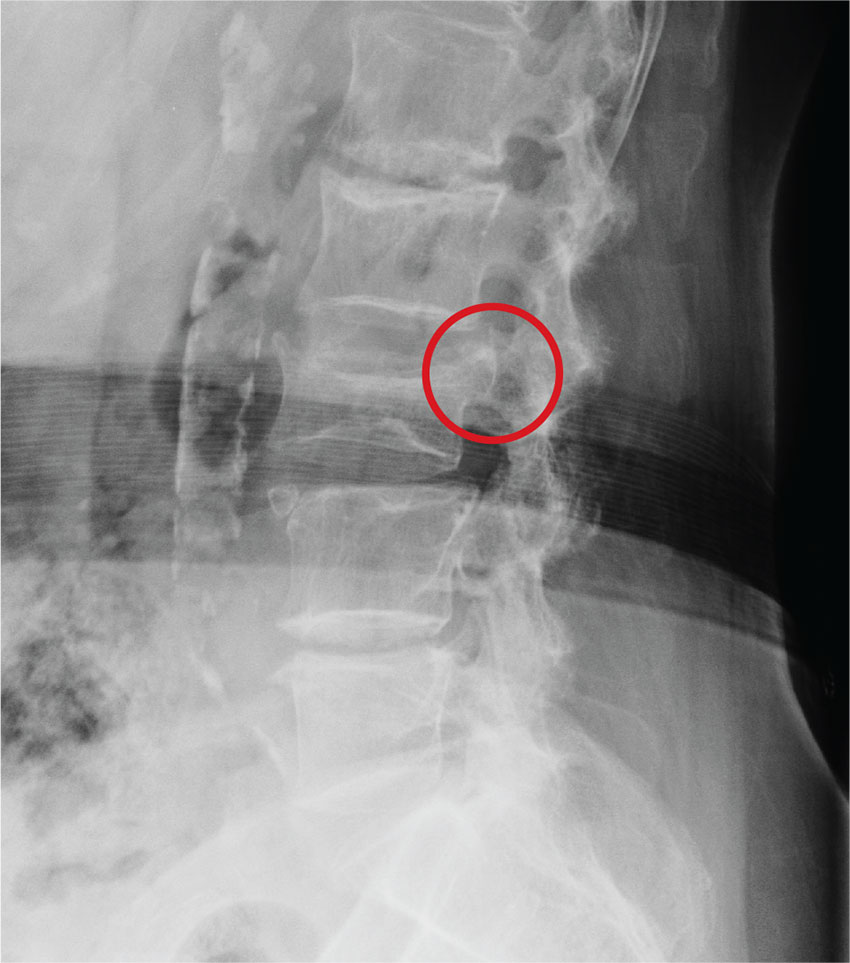

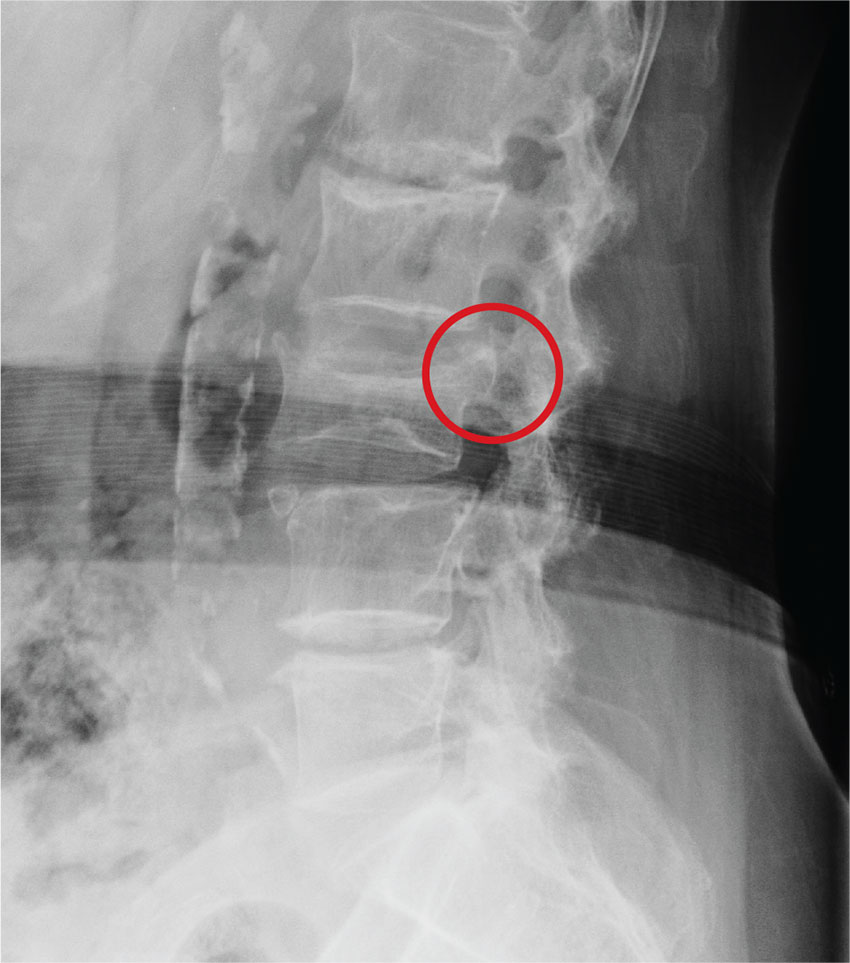

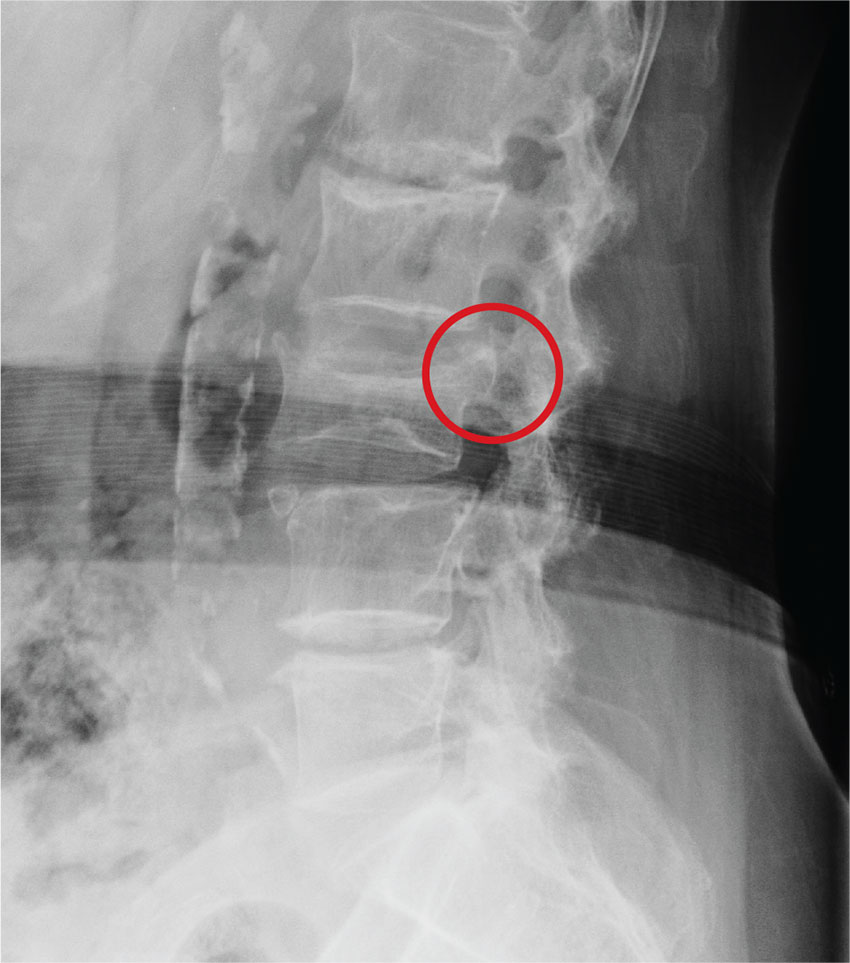

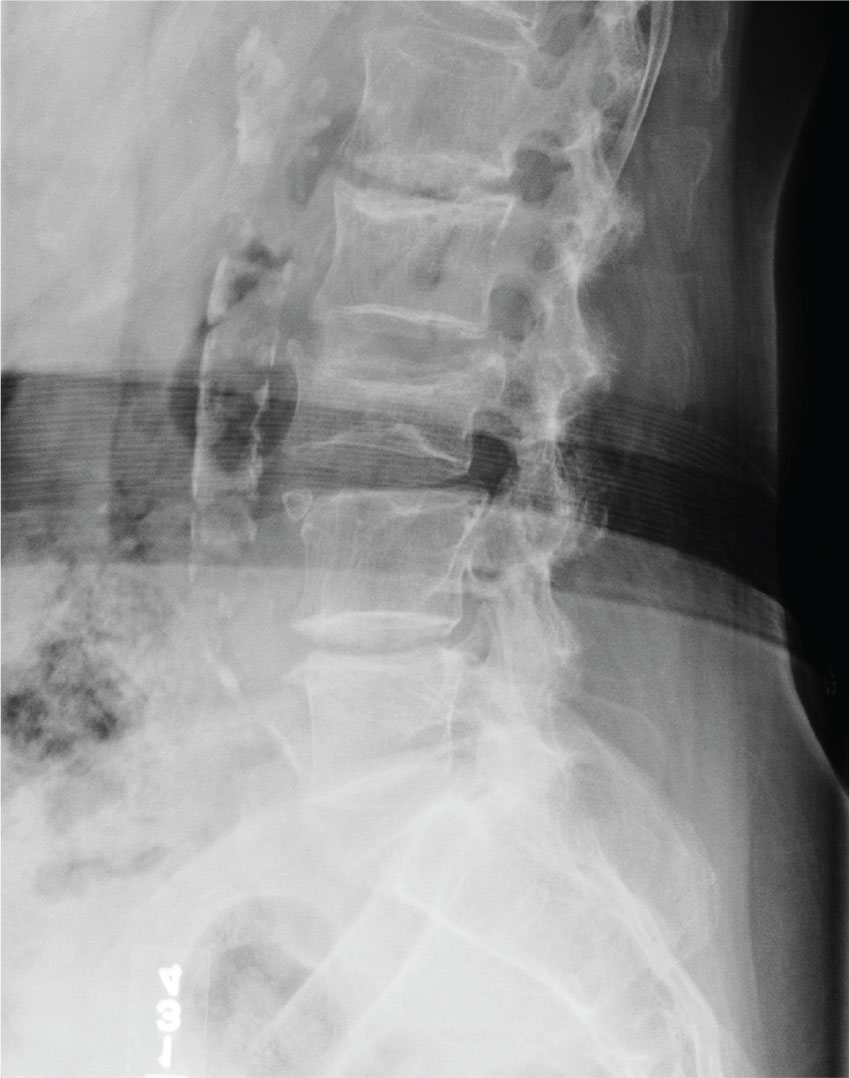

To encourage medical-surgical nurses to become more engaged and confident in subspecialty patient care, the authors developed a bedside neurosurgical nursing guide to allow for independent procedure related education. The comprehensive guide summarized the clinical course for postoperative neurosurgical patients undergoing cranial and spinal surgeries. This guide included appropriate surgery-related images, procedure overviews, management decisions, potential postoperative complications, and wound care directions. The guide was distributed to medical-surgical nurses caring for neurosurgical patients. The authors hypothesized that the guide would enable nurses to better predict adverse outcomes and respond appropriately and would improve confidence in patient care.

Methods

For educational purposes, a bedside neurosurgical nursing guide (text and graphics) was created for the 16 surgical subspecialty nurses at the VAPHCS. The guide detailed the most common cranial and spinal neurosurgical procedures performed at VAPHCS and was written based on a typical postoperative course for each procedure by the chief neurosurgery resident at VAPHCS with collaboration from the attending neurosurgeons (Figure).

A quality improvement (QI) project was undertaken to assess nursing confidence with neurosurgical patients’ care pre- and postfamiliarity with the bedside neurosurgical nursing guide. A literature search revealed no validated survey assessing nursing confidence, so one was created using the Likert scale. Specifically, an anonymous 6-question survey was completed by all 16 surgical nurses prior to familiarization with the guide. Responses were recorded as scores of 1 to 5 for questions 1, 3, and 4, with a response of 1 indicative of no comfort or confidence and a response of 5 indicative of the highest level of comfort or confidence. Responses were recorded as either true or false for questions 2 and 6, and never, occasionally, frequently, or always for question 5.

The guide was made available to nurses for 6 months without encouragement to use it. After 6 months, a 3-week period of familiarization with and education about the availability of the guide was instituted at morning nursing reports; the total availability of the guide to nursing staff was 6 months 3 weeks. After this period the same 6-question survey was distributed, and data were collected.

Survey responses were categorized into 2 groups. Responses to questions 1, 3, and 4 were categorized as group 1, and responses to questions 4 and 5 were categorized as group 2. Responses (never and occasionally) to question 5, were categorized as group 1 and responses (frequently and always) as group 2 (Table). Responses to questions 2 and 6 were grouped 1 for true and 2 for false. Nurses participating in this study ranged in age from 22 to 57 years, education level ranged from registered nurse to a bachelor of science in nursing, and years of experience ranged from < 1 year to 27 years.

Statistics were calculated using chi-square analysis with Yates correction online calculator. For the chi-square analysis, the prefamiliarization data for groups 1 and 2 were used as the expected values, and the postfamiliarization data were used for the observed values. In this manner, differences were discerned between the before and after questionnaire responses. The VAPHCS institutional review board determined that the study was not human research and exempt from review.

Findings

Anonymous survey responses were collected from all 16 surgical subspecialty nurses both prior and after familiarization with the nursing guide.The response rate was 100% with only a few incomplete responses excluded from the analysis. Three questions in the prefamiliarization questionnaire had no appropriate response, and 1 question in the postfamiliarization survey had no appropriate response.

Improvement was statistically significant in responses for questions 1, 3, 5, and 6 (P = .026, .008, .004, and .033, respectively). No significant differences were found for questions 2 and 4 (P = .974 and .116, respectively). It is possible that there was no significant difference in question 2 because prefamiliarization responses were already favorable. Even if nurses did not feel comfortable taking care of neurosurgical patients (as assessed in question 1), they noted confidence improvement by working on the ward and through informal assimilation of knowledge and skill, which would have accumulated naturally over 1 year.

Prior to familiarization with the guide, 7 nurses did not feel confident in assessing the need to contact a physician (question 4). After familiarization with the nursing guide, favorable responses increased from 9 to 14 nurses. Results trended toward but did not reach statistical significance, likely due to the small sample size.

Ultimately, in the 16 surgical subspecialty nurses surveyed, familiarization with the nursing guide was shown to improve comfort in taking care of neurosurgical patients and increase confidence in patient care skills. At the end of the QI project (6 months, 3 weeks), all nurses knew where to locate the bedside neurosurgical nursing guide and were familiar with it and its use. The guide remains accessible to the medical-surgical nurses and continues to be used.

Discussion

Nursing confidence has an undervalued effect on patient care.2 Confidence, or a belief in one’s own ability, varies directly with competence. Systematic quantification of nursing competence has been extensively studied using self-report questionnaires and clinical simulations.2,3 Competency can be quantified and normalized using formal assessment; however, confidence is somewhat intangible. Nursing confidence is a situation-dependent subjective feeling of security and is derived from an internalized assessment of skills that are commensurate with patient needs. Nursing confidence is further influenced by an intuited value within the care team, adequate knowledge of the patient’s condition, and procedures and protocols.4

A similar but less specific definition deconstructs nursing confidence as “significance of a professional network of coworkers” and the “importance of confirmation of professional role and competence.”5 The professional network of coworkers is invaluable as it underlies the essence of patient-centered care. The adaptive leadership framework is integral to the modern delivery of patient care, and via this framework frontline clinical staff, including nurses, are empowered.6,7

The second portion of Haavardsholm and Nåden’s definition, “importance of confirmation of professional role and competence” describes the association of the most easily augmented correlate of confidence: competency.5 Nursing competency is supplemented continuously with in-service training and recertification processes; however, despite this, demands placed on nurses can be technologically advanced and extremely varied. Nursing competency is known to directly correlate with increasing education, as nurses holding a master’s degree have been shown to outperform those with a bachelor of nursing degree.3

Increased formal education as well as increased work experience (> 5 years) are correlated with increased critical thinking ability.4,5 The critical thinking ability of health care providers can be fortified by clinical simulation, which leads to statistically significant improvement in clinical competency.2,3

A literature review of Medline and the National Library of Medicine PubMed online databases for search terms (nurs*, confidence, bedside, guide) was performed but did not result in original research assessing nurse confidence related to bedside guides. In this population, nurses were anonymously compared against their own historical data obviating any effect of education or experience on survey measures.

Nursing Self-Confidence

Evidence suggests that nursing confidence is a complex manifestation of the security felt within the care team and the comfort of one’s own professional abilities.4 Patients’ trust in the team caring for them is based on the confidence exuded by the team.8 In this way, nursing confidence can affect the patient-care team profoundly. Value is maximized when a nurse’s self-confidence engenders patient confidence and trust. Due to the varied patient load and complexity of subspecialty nursing care, it is hypothesized that bedside manuals/guidelines can be used to educate the subspecialty nurses on specific patient-related issues.

Nursing practice competence and confidence is vital to providing care for patients with complex postsurgical health care needs. Patient safety and outcome are paramount. This can be intimidating for newly qualified surgical subspecialty nurses who have not yet had experience with or adequate exposure to patients with complex postsurgical needs. Surgical nursing continuing education places an emphasis on adaptation to ever-changing specialized surgical procedures and postoperative patient care. Nevertheless, it is difficult for surgical subspecialty nurses to learn and retain all the possible complexities of individual cases and to confidently, appropriately, and safely care for patients especially when adverse events arise.

Recognizing that leadership is personal and not dependent on hierarchy, surgical subspecialty nurses may be better suited to specific bedside training and counseling.6,9 A key factor influencing nursing confidence is communication and collaboration with physicians.9 The role of the physician at VA medical facilities is no longer to be a commanding figure with complete medical autonomy; rather, a unified team of specialized practitioners collaboratively facilitate and deliver patient care.

There is no specific research detailing the use of bedside nursing guides in caring for postoperative patients. However, at VAPHCS, nurses created supplemental material regarding postoperative acute care of vascular surgery patients, which was found to be subjectively helpful in elevating nursing confidence. To the authors’ knowledge, no such supplemental information/guide exists for other specialty surgical services.

The surgical nursing guide created here detailed visuals of many common neurosurgical procedures performed at VAPHCS and included a prioritized checklist, which the 16 surgical subspecialty nurses could reference postoperatively. The authors hypothesized that this would enhance the nurses’ ability to efficiently manage specific situations while bridging communication gaps between surgical teams and nurses. The survey results agree with previous reports that suggested that the application of an adaptive leadership framework would empower nurses to deliver excellent patient-centered care, care that can be augmented with subspecialty nursing guides.7,10

Based on these results the authors propose that subspecialty surgical services consider use of a practical nursing guide for all surgical subspecialty nurses to reference, improve familiarity with procedures, and provide guidance to manage adverse events. Since implementing this reader-friendly paradigm within neurosurgical care, a nurse driven expansion has now included other subspecialty services at the VAPHCS with success.

Limitations

Survey responses have inherent bias and sampling error rates. The sample size for this survey was small. Data were grouped for data analysis. Competency and patient outcomes were not measured.

Future Directions

Despite specific surgical specialty postoperative patient care training, an overall lack of confidence can persist. A physician-created neurosurgical nursing guide that detailed the most common neurosurgical procedures, expected postoperative care, and potential emergencies was shown to improve nursing confidence. Collaborative (physician and nursing leaders) QI projects, such as described here; development of specific surgical specialty initiatives designed to improve confidence and quality; and nurse-physician communication and teamwork could lead to improved patient satisfaction and outcome.

The costs associated with developing and using bedside nursing guides are relatively low, and efficiency can be considered high. Competency improvement could be measured by creating a specialty-specific case scenario question bank. Effects on patient satisfaction and outcome could be measured by a patient satisfaction survey. Improvements in beside catastrophe management could be prospectively tracked; for example, rates of mismanagement of mobility status, emergent transfers to the intensive care unit, or poor wound care could be compared pre- and postfamiliarization with a subspecialty guide.

Conclusion

Familiarization with the VAPHCS neurosurgical nursing guide had a positive impact on the confidence of medical-surgical nurses caring for neurosurgical patients. Medical-surgical nurses were more comfortable taking care of neurosurgical patients; they felt the guide helped improve skills and noted improved knowledge regarding involvement of physician oversight. Although objective parameters were not assessed, improvement in nursing confidence in general leads to improved overall nurse-physician communication and patient management. A further study might target objective parameters associated with guide usage, such as changes in the number of emergencies or calls to physicians regarding management.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andy Rekito, MS, for illustrative assistance.

1. Pusateri ME, Prior MM, Kiely SC. The role of the non-ICU staff nurse on a medical emergency team: perceptions and understanding. Am J Nurs. 2011;111(5):22-29, quiz 30-31.

2. Bambini D, Washburn J, Perkins R. Outcomes of clinical simulation for novice nursing students: communication, confidence, clinical judgment. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2009;30(2):79-82.

3. Chang MJ, Chang YJ, Kuo SH, Yang YH, Chou FH. Relationships between critical thinking ability and nursing competence in clinical nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(21-22):3224-3232.

4. Perry P. Concept analysis: confidence/self-confidence. Nurs Forum. 2011;46(4):218-230.

5. Haavardsholm I, Nåden D. The concept of confidence—the nurse’s perception. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2009;18(5):483-491.

6. Bailey DE Jr, Docherty SL, Adams JA, et al. Studying the clinical encounter with the Adaptive Leadership framework. J Healthc Leadersh. 2012;2012(4):83-91.

7. Hall C, McCutcheon H, Deuter K, Matricciani L. Evaluating and improving a model of nursing care delivery: a process of partnership. Collegian. 2012;19(4):203-210.

8. Williams AM, Irurita VF. Therapeutic and non-therapeutic interpersonal interactions: the patient’s perspective. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(7):806-815.

9. Carryer J. Collaboration between doctors and nurses. J Prim Health Care. 2011;3(1):77-79.

10. Chadwick MM. Creating order out of chaos: a leadership approach. AORN J. 2010;91(1):154-170.

The VA Portland Healthcare System (VAPHCS) is a 277-bed facility that serves more than 85,000 inpatient and 880,000 outpatient visits each year from veterans in Oregon and southwestern Washington. The VAPHCS consists of a main tertiary care VAMC with an acute medical and surgical facility that includes 30 beds serving qualifying veterans. Supported surgical specialties include urology, general surgery, vascular surgery, otolaryngology, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, cardiothoracic surgery, transplant surgery, and neurological surgery. Neurosurgical patients account for about 12% to 13% of annual surgical patients. The VAPHCS also is partnered with Oregon Health & Science University in the training of health care professionals, such as physicians and nurses.

The expectation at the VAPHCS is that medical-surgical nurses care for 4 to 5 concurrent patients, often from different surgical services. Caring for patients with different medical and surgical needs, variable ambulatory, swallowing, and elimination functions, and different physician teams can become confusing; even within a single surgical service, postoperative care due to procedure complexity, specificity of care orders, and the real possibility of medical catastrophe can seem overwhelming. Therefore, subspecialty nursing training poses a challenge that requires technical in-service and didactic education and allocation of resources.

Despite systems level subspecialty nursing training, medical emergencies identified at the bedside can be mismanaged.1 Errors in care can be due to an incomplete knowledge of the patient’s procedure and misunderstanding of positioning and activity limitations.

To encourage medical-surgical nurses to become more engaged and confident in subspecialty patient care, the authors developed a bedside neurosurgical nursing guide to allow for independent procedure related education. The comprehensive guide summarized the clinical course for postoperative neurosurgical patients undergoing cranial and spinal surgeries. This guide included appropriate surgery-related images, procedure overviews, management decisions, potential postoperative complications, and wound care directions. The guide was distributed to medical-surgical nurses caring for neurosurgical patients. The authors hypothesized that the guide would enable nurses to better predict adverse outcomes and respond appropriately and would improve confidence in patient care.

Methods

For educational purposes, a bedside neurosurgical nursing guide (text and graphics) was created for the 16 surgical subspecialty nurses at the VAPHCS. The guide detailed the most common cranial and spinal neurosurgical procedures performed at VAPHCS and was written based on a typical postoperative course for each procedure by the chief neurosurgery resident at VAPHCS with collaboration from the attending neurosurgeons (Figure).

A quality improvement (QI) project was undertaken to assess nursing confidence with neurosurgical patients’ care pre- and postfamiliarity with the bedside neurosurgical nursing guide. A literature search revealed no validated survey assessing nursing confidence, so one was created using the Likert scale. Specifically, an anonymous 6-question survey was completed by all 16 surgical nurses prior to familiarization with the guide. Responses were recorded as scores of 1 to 5 for questions 1, 3, and 4, with a response of 1 indicative of no comfort or confidence and a response of 5 indicative of the highest level of comfort or confidence. Responses were recorded as either true or false for questions 2 and 6, and never, occasionally, frequently, or always for question 5.

The guide was made available to nurses for 6 months without encouragement to use it. After 6 months, a 3-week period of familiarization with and education about the availability of the guide was instituted at morning nursing reports; the total availability of the guide to nursing staff was 6 months 3 weeks. After this period the same 6-question survey was distributed, and data were collected.

Survey responses were categorized into 2 groups. Responses to questions 1, 3, and 4 were categorized as group 1, and responses to questions 4 and 5 were categorized as group 2. Responses (never and occasionally) to question 5, were categorized as group 1 and responses (frequently and always) as group 2 (Table). Responses to questions 2 and 6 were grouped 1 for true and 2 for false. Nurses participating in this study ranged in age from 22 to 57 years, education level ranged from registered nurse to a bachelor of science in nursing, and years of experience ranged from < 1 year to 27 years.

Statistics were calculated using chi-square analysis with Yates correction online calculator. For the chi-square analysis, the prefamiliarization data for groups 1 and 2 were used as the expected values, and the postfamiliarization data were used for the observed values. In this manner, differences were discerned between the before and after questionnaire responses. The VAPHCS institutional review board determined that the study was not human research and exempt from review.

Findings

Anonymous survey responses were collected from all 16 surgical subspecialty nurses both prior and after familiarization with the nursing guide.The response rate was 100% with only a few incomplete responses excluded from the analysis. Three questions in the prefamiliarization questionnaire had no appropriate response, and 1 question in the postfamiliarization survey had no appropriate response.

Improvement was statistically significant in responses for questions 1, 3, 5, and 6 (P = .026, .008, .004, and .033, respectively). No significant differences were found for questions 2 and 4 (P = .974 and .116, respectively). It is possible that there was no significant difference in question 2 because prefamiliarization responses were already favorable. Even if nurses did not feel comfortable taking care of neurosurgical patients (as assessed in question 1), they noted confidence improvement by working on the ward and through informal assimilation of knowledge and skill, which would have accumulated naturally over 1 year.

Prior to familiarization with the guide, 7 nurses did not feel confident in assessing the need to contact a physician (question 4). After familiarization with the nursing guide, favorable responses increased from 9 to 14 nurses. Results trended toward but did not reach statistical significance, likely due to the small sample size.

Ultimately, in the 16 surgical subspecialty nurses surveyed, familiarization with the nursing guide was shown to improve comfort in taking care of neurosurgical patients and increase confidence in patient care skills. At the end of the QI project (6 months, 3 weeks), all nurses knew where to locate the bedside neurosurgical nursing guide and were familiar with it and its use. The guide remains accessible to the medical-surgical nurses and continues to be used.

Discussion

Nursing confidence has an undervalued effect on patient care.2 Confidence, or a belief in one’s own ability, varies directly with competence. Systematic quantification of nursing competence has been extensively studied using self-report questionnaires and clinical simulations.2,3 Competency can be quantified and normalized using formal assessment; however, confidence is somewhat intangible. Nursing confidence is a situation-dependent subjective feeling of security and is derived from an internalized assessment of skills that are commensurate with patient needs. Nursing confidence is further influenced by an intuited value within the care team, adequate knowledge of the patient’s condition, and procedures and protocols.4

A similar but less specific definition deconstructs nursing confidence as “significance of a professional network of coworkers” and the “importance of confirmation of professional role and competence.”5 The professional network of coworkers is invaluable as it underlies the essence of patient-centered care. The adaptive leadership framework is integral to the modern delivery of patient care, and via this framework frontline clinical staff, including nurses, are empowered.6,7

The second portion of Haavardsholm and Nåden’s definition, “importance of confirmation of professional role and competence” describes the association of the most easily augmented correlate of confidence: competency.5 Nursing competency is supplemented continuously with in-service training and recertification processes; however, despite this, demands placed on nurses can be technologically advanced and extremely varied. Nursing competency is known to directly correlate with increasing education, as nurses holding a master’s degree have been shown to outperform those with a bachelor of nursing degree.3

Increased formal education as well as increased work experience (> 5 years) are correlated with increased critical thinking ability.4,5 The critical thinking ability of health care providers can be fortified by clinical simulation, which leads to statistically significant improvement in clinical competency.2,3

A literature review of Medline and the National Library of Medicine PubMed online databases for search terms (nurs*, confidence, bedside, guide) was performed but did not result in original research assessing nurse confidence related to bedside guides. In this population, nurses were anonymously compared against their own historical data obviating any effect of education or experience on survey measures.

Nursing Self-Confidence

Evidence suggests that nursing confidence is a complex manifestation of the security felt within the care team and the comfort of one’s own professional abilities.4 Patients’ trust in the team caring for them is based on the confidence exuded by the team.8 In this way, nursing confidence can affect the patient-care team profoundly. Value is maximized when a nurse’s self-confidence engenders patient confidence and trust. Due to the varied patient load and complexity of subspecialty nursing care, it is hypothesized that bedside manuals/guidelines can be used to educate the subspecialty nurses on specific patient-related issues.

Nursing practice competence and confidence is vital to providing care for patients with complex postsurgical health care needs. Patient safety and outcome are paramount. This can be intimidating for newly qualified surgical subspecialty nurses who have not yet had experience with or adequate exposure to patients with complex postsurgical needs. Surgical nursing continuing education places an emphasis on adaptation to ever-changing specialized surgical procedures and postoperative patient care. Nevertheless, it is difficult for surgical subspecialty nurses to learn and retain all the possible complexities of individual cases and to confidently, appropriately, and safely care for patients especially when adverse events arise.

Recognizing that leadership is personal and not dependent on hierarchy, surgical subspecialty nurses may be better suited to specific bedside training and counseling.6,9 A key factor influencing nursing confidence is communication and collaboration with physicians.9 The role of the physician at VA medical facilities is no longer to be a commanding figure with complete medical autonomy; rather, a unified team of specialized practitioners collaboratively facilitate and deliver patient care.

There is no specific research detailing the use of bedside nursing guides in caring for postoperative patients. However, at VAPHCS, nurses created supplemental material regarding postoperative acute care of vascular surgery patients, which was found to be subjectively helpful in elevating nursing confidence. To the authors’ knowledge, no such supplemental information/guide exists for other specialty surgical services.

The surgical nursing guide created here detailed visuals of many common neurosurgical procedures performed at VAPHCS and included a prioritized checklist, which the 16 surgical subspecialty nurses could reference postoperatively. The authors hypothesized that this would enhance the nurses’ ability to efficiently manage specific situations while bridging communication gaps between surgical teams and nurses. The survey results agree with previous reports that suggested that the application of an adaptive leadership framework would empower nurses to deliver excellent patient-centered care, care that can be augmented with subspecialty nursing guides.7,10

Based on these results the authors propose that subspecialty surgical services consider use of a practical nursing guide for all surgical subspecialty nurses to reference, improve familiarity with procedures, and provide guidance to manage adverse events. Since implementing this reader-friendly paradigm within neurosurgical care, a nurse driven expansion has now included other subspecialty services at the VAPHCS with success.

Limitations

Survey responses have inherent bias and sampling error rates. The sample size for this survey was small. Data were grouped for data analysis. Competency and patient outcomes were not measured.

Future Directions

Despite specific surgical specialty postoperative patient care training, an overall lack of confidence can persist. A physician-created neurosurgical nursing guide that detailed the most common neurosurgical procedures, expected postoperative care, and potential emergencies was shown to improve nursing confidence. Collaborative (physician and nursing leaders) QI projects, such as described here; development of specific surgical specialty initiatives designed to improve confidence and quality; and nurse-physician communication and teamwork could lead to improved patient satisfaction and outcome.

The costs associated with developing and using bedside nursing guides are relatively low, and efficiency can be considered high. Competency improvement could be measured by creating a specialty-specific case scenario question bank. Effects on patient satisfaction and outcome could be measured by a patient satisfaction survey. Improvements in beside catastrophe management could be prospectively tracked; for example, rates of mismanagement of mobility status, emergent transfers to the intensive care unit, or poor wound care could be compared pre- and postfamiliarization with a subspecialty guide.

Conclusion

Familiarization with the VAPHCS neurosurgical nursing guide had a positive impact on the confidence of medical-surgical nurses caring for neurosurgical patients. Medical-surgical nurses were more comfortable taking care of neurosurgical patients; they felt the guide helped improve skills and noted improved knowledge regarding involvement of physician oversight. Although objective parameters were not assessed, improvement in nursing confidence in general leads to improved overall nurse-physician communication and patient management. A further study might target objective parameters associated with guide usage, such as changes in the number of emergencies or calls to physicians regarding management.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andy Rekito, MS, for illustrative assistance.

The VA Portland Healthcare System (VAPHCS) is a 277-bed facility that serves more than 85,000 inpatient and 880,000 outpatient visits each year from veterans in Oregon and southwestern Washington. The VAPHCS consists of a main tertiary care VAMC with an acute medical and surgical facility that includes 30 beds serving qualifying veterans. Supported surgical specialties include urology, general surgery, vascular surgery, otolaryngology, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, cardiothoracic surgery, transplant surgery, and neurological surgery. Neurosurgical patients account for about 12% to 13% of annual surgical patients. The VAPHCS also is partnered with Oregon Health & Science University in the training of health care professionals, such as physicians and nurses.

The expectation at the VAPHCS is that medical-surgical nurses care for 4 to 5 concurrent patients, often from different surgical services. Caring for patients with different medical and surgical needs, variable ambulatory, swallowing, and elimination functions, and different physician teams can become confusing; even within a single surgical service, postoperative care due to procedure complexity, specificity of care orders, and the real possibility of medical catastrophe can seem overwhelming. Therefore, subspecialty nursing training poses a challenge that requires technical in-service and didactic education and allocation of resources.

Despite systems level subspecialty nursing training, medical emergencies identified at the bedside can be mismanaged.1 Errors in care can be due to an incomplete knowledge of the patient’s procedure and misunderstanding of positioning and activity limitations.

To encourage medical-surgical nurses to become more engaged and confident in subspecialty patient care, the authors developed a bedside neurosurgical nursing guide to allow for independent procedure related education. The comprehensive guide summarized the clinical course for postoperative neurosurgical patients undergoing cranial and spinal surgeries. This guide included appropriate surgery-related images, procedure overviews, management decisions, potential postoperative complications, and wound care directions. The guide was distributed to medical-surgical nurses caring for neurosurgical patients. The authors hypothesized that the guide would enable nurses to better predict adverse outcomes and respond appropriately and would improve confidence in patient care.

Methods

For educational purposes, a bedside neurosurgical nursing guide (text and graphics) was created for the 16 surgical subspecialty nurses at the VAPHCS. The guide detailed the most common cranial and spinal neurosurgical procedures performed at VAPHCS and was written based on a typical postoperative course for each procedure by the chief neurosurgery resident at VAPHCS with collaboration from the attending neurosurgeons (Figure).