User login

Which Patients With Epilepsy Can Safely Drive?

HOUSTON—Seizure duration and impaired consciousness may be important factors that affect driving performance, according to a study presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “With further work, we hope to … determine whether specific seizure types or localizations present a greater driving risk, with the goal of providing improved guidance to physicians and patients with epilepsy,” researchers said.

A lack of data about driving performance during ictal and postictal periods can make it difficult for physicians to determine whether patients can safely drive.

To study driving impairment during seizures, Hal Blumenfeld, MD, PhD, Director of the Yale Clinical Neuroscience Imaging Center in New Haven, Connecticut, and colleagues asked patients to perform a driving simulation test during inpatient video EEG monitoring. Dr. Blumenfeld, the study’s lead author, is the Mark Loughridge and Michele Williams Professor of Neurology and a Professor of Neuroscience and Neurosurgery at Yale University.

The study included 20 patients who were observed in the epilepsy monitoring unit at Yale New Haven Hospital. Investigators analyzed ictal and interictal driving data captured prospectively from the driving simulator. A total of 33 seizures were analyzed. The investigators compared interictal and ictal driving performance through quantitative analysis. Variables included car velocity, steering wheel movement, braking, and crash occurrence.

Patients drove between one and 10 hours, with an average driving duration of about three hours. Patients had variable impairment during ictal and postictal periods and during subclinical epileptiform discharges. Some seizures showed obvious impairment, and others showed no change in driving performance. Seizures with driving impairment had significantly greater duration and were more likely to involve impaired consciousness than seizures without driving impairment. Seven of the seizures resulted in crashes. Seizures lasted an average of 75 seconds in patients who crashed, compared with an average of 30 seconds in patients who did not crash.

Driving simulations during inpatient video-EEG monitoring may be a useful way to determine factors that influence driving safety, the researchers concluded.

“It is going to take a lot more data to come up with a reliable way of predicting which people with epilepsy should drive and which should not,” said Dr. Blumenfeld. “We want to unearth more detail to learn if there are people with epilepsy who are driving who shouldn’t be, as well those who are not driving who can safely drive.”

HOUSTON—Seizure duration and impaired consciousness may be important factors that affect driving performance, according to a study presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “With further work, we hope to … determine whether specific seizure types or localizations present a greater driving risk, with the goal of providing improved guidance to physicians and patients with epilepsy,” researchers said.

A lack of data about driving performance during ictal and postictal periods can make it difficult for physicians to determine whether patients can safely drive.

To study driving impairment during seizures, Hal Blumenfeld, MD, PhD, Director of the Yale Clinical Neuroscience Imaging Center in New Haven, Connecticut, and colleagues asked patients to perform a driving simulation test during inpatient video EEG monitoring. Dr. Blumenfeld, the study’s lead author, is the Mark Loughridge and Michele Williams Professor of Neurology and a Professor of Neuroscience and Neurosurgery at Yale University.

The study included 20 patients who were observed in the epilepsy monitoring unit at Yale New Haven Hospital. Investigators analyzed ictal and interictal driving data captured prospectively from the driving simulator. A total of 33 seizures were analyzed. The investigators compared interictal and ictal driving performance through quantitative analysis. Variables included car velocity, steering wheel movement, braking, and crash occurrence.

Patients drove between one and 10 hours, with an average driving duration of about three hours. Patients had variable impairment during ictal and postictal periods and during subclinical epileptiform discharges. Some seizures showed obvious impairment, and others showed no change in driving performance. Seizures with driving impairment had significantly greater duration and were more likely to involve impaired consciousness than seizures without driving impairment. Seven of the seizures resulted in crashes. Seizures lasted an average of 75 seconds in patients who crashed, compared with an average of 30 seconds in patients who did not crash.

Driving simulations during inpatient video-EEG monitoring may be a useful way to determine factors that influence driving safety, the researchers concluded.

“It is going to take a lot more data to come up with a reliable way of predicting which people with epilepsy should drive and which should not,” said Dr. Blumenfeld. “We want to unearth more detail to learn if there are people with epilepsy who are driving who shouldn’t be, as well those who are not driving who can safely drive.”

HOUSTON—Seizure duration and impaired consciousness may be important factors that affect driving performance, according to a study presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “With further work, we hope to … determine whether specific seizure types or localizations present a greater driving risk, with the goal of providing improved guidance to physicians and patients with epilepsy,” researchers said.

A lack of data about driving performance during ictal and postictal periods can make it difficult for physicians to determine whether patients can safely drive.

To study driving impairment during seizures, Hal Blumenfeld, MD, PhD, Director of the Yale Clinical Neuroscience Imaging Center in New Haven, Connecticut, and colleagues asked patients to perform a driving simulation test during inpatient video EEG monitoring. Dr. Blumenfeld, the study’s lead author, is the Mark Loughridge and Michele Williams Professor of Neurology and a Professor of Neuroscience and Neurosurgery at Yale University.

The study included 20 patients who were observed in the epilepsy monitoring unit at Yale New Haven Hospital. Investigators analyzed ictal and interictal driving data captured prospectively from the driving simulator. A total of 33 seizures were analyzed. The investigators compared interictal and ictal driving performance through quantitative analysis. Variables included car velocity, steering wheel movement, braking, and crash occurrence.

Patients drove between one and 10 hours, with an average driving duration of about three hours. Patients had variable impairment during ictal and postictal periods and during subclinical epileptiform discharges. Some seizures showed obvious impairment, and others showed no change in driving performance. Seizures with driving impairment had significantly greater duration and were more likely to involve impaired consciousness than seizures without driving impairment. Seven of the seizures resulted in crashes. Seizures lasted an average of 75 seconds in patients who crashed, compared with an average of 30 seconds in patients who did not crash.

Driving simulations during inpatient video-EEG monitoring may be a useful way to determine factors that influence driving safety, the researchers concluded.

“It is going to take a lot more data to come up with a reliable way of predicting which people with epilepsy should drive and which should not,” said Dr. Blumenfeld. “We want to unearth more detail to learn if there are people with epilepsy who are driving who shouldn’t be, as well those who are not driving who can safely drive.”

What’s next for deep brain stimulation in OCD?

VIENNA – Even though deep brain stimulation has been used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder in fewer than 300 patients worldwide, the therapy has had a huge impact on understanding of the disorder, Damiaan Denys, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Indeed, the efficacy of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in the most severe, treatment-refractory cases of OCD casts doubt upon the fundamental construct clinicians have relied upon for decades to comprehend OCD: Namely, that affected patients first experience obsessions, which induce anxiety, which then stimulates compulsions, and engaging in those compulsions brings relief and reward, and then the whole cycle starts over again.

That construct may not actually be true.

“Deep brain stimulation will force us to rethink OCD,” predicted Dr. Denys, professor and head of psychiatry at the University of Amsterdam.

What does DBS change, and is there a temporal order? It varies, the psychiatrist said.

“In some patients, anxiety is the first thing that changes. In others, it starts with obsessions. Compulsions do decrease, but it’s difficult. It takes some time, and often we need supplemental cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). What changes, mainly, in my experience, is not symptoms, but something outside of OCD: namely, mood. Deep brain stimulation has a huge impact on mood. That’s an interesting finding, because it suggests the possibility that you can change a psychiatric disorder by changing symptoms that are thought of as being outside the disorder,” Dr. Denys observed.

“Another interesting thing is that deep brain stimulation changes things that are not even within psychiatry. When we ask our patients what has been the most profound impact deep brain stimulation has had on their lives, all of them say, ‘It increases my self-confidence.’ And that’s not something that is included in our scales. We assess patients using the HAM-D [Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression] and Y-BOCS [Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale] and other measures, but there are still some very important aspects we are not taking into account and that have a profound effect on symptoms. In this case, using deep brain stimulation, we improve self-confidence and thereby change a whole chain of symptoms,” he continued.

Among the 60 highly refractory OCD patients treated by DBS by Dr. Denys and his colleagues at the Amsterdam center over the past 15 years, 15% were cured as a result.

“I purposely use the word ‘cured,’ because they don’t have obsessive-compulsive symptoms, anymore, which is, of course, extraordinary,” Dr. Denys noted.

An additional 35% of patients had a good response, defined as 60%-80% improvement on the Y-BOCS. Ten percent of patients were partial responders, with a 20%-40% improvement on the Y-BOCS. And 15% were nonresponders.

Closed-loop system coming

DBS entails implantation of electrodes deep within the brain to interrupt dysfunctional brain signals in local areas and across neural networks. This dysfunctional brain activity is expressed as symptoms. To date, DBS has been used in what’s called an open-loop system: Patients report the symptoms they’re experiencing and the clinician then adjusts the electrode settings in order to quell those symptoms. This approach is about to change. The technology has improved vastly since the early days, when the electrodes had four contact points. Now they have 64 contact points, and are capable of sending and receiving electrical signals.

“The next step in deep brain stimulation will be a closed-loop system. We will remove the clinician and the patient, and attempt to use a device capable of recording what happens in the brain and then changing electrical activity in response to the recordings. Our purpose will be to block these brain signals in advance of obsessions and compulsions so patients don’t have these symptoms. It’s technically possible. It has been done in Parkinson’s, and I think it’s the next step in psychiatry,” Dr. Denys said.

Indeed, he and his coinvestigators are planning formal studies of closed-loop DBS. For him, the prospect raises three key questions: What are the neural correlates of OCD symptoms? What about the ethics of implanting a device in the brain which by itself results in different life experiences? And will closed-loop DBS have superior efficacy, compared with open-loop DBS?

“How is the mind rooted in the brain, and how is the brain expressed in the mind? It’s the most fascinating question; it’s why we all love psychiatry, and up until now, there are no answers,” he observed.

Significant progress already has been made on the neural correlates question. Dr. Denys and his colleagues have found that when OCD patients with deep brain electrodes engage in cleaning compulsions, their local field potentials in the striatal area show peaks of roughly 9 Hz in the alpha range and in the beta/low gamma range. These patterns may represent compulsive behavior and likely could be useful in steering a closed-loop system. Also, the Dutch investigators have found that 3- to 8-Hz theta oscillations in local field potentials in the striatal area may represent a neural signature for anxiety and/or obsessions.

Using a closed-loop system, he continued, investigators plan to test two quite different hypotheses about the fundamental nature of OCD. One is that obsessions, anxiety, compulsions, and relief are each separately related to different brain areas. The other hypothesis is that one central brain stimulus drives the chain of symptoms that characterize OCD, and that by identifying and blocking that primary signal, the whole pathologic process can be stopped.

Current status of procedure

While Dr. Denys focused on the near future of DBS for OCD, another speaker at the session, Sina Kohl, PhD, addressed DBS for OCD as it exists today, particularly the who, how, and where.

The “who” is the relatively rare patient with truly refractory OCD after multiple drug trials of agents in different antidepressant classes, one of which should be clomipramine, as well as a failed course of CBT provided by an expert in CBT for OCD, of which there are relatively few. In a study led by investigators at Brown University, Providence, R.I., only 2 of 325 patients with OCD were deemed truly refractory (J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014 Winter;26[1]:81-6). That sounds about right, according to Dr. Kohl, a psychologist at the University of Cologne, in Germany.

The “how” is to deliver DBS in conjunction with CBT. Response rates are higher at centers where that practice is routine, she added.

The “where” is an unsettled question. In Dr. Kohl’s meta-analysis of 25 published DBS studies, electrode placement in four different DBS target structures produced similar results: the nucleus accumbens, the anterior limb of the internal capsule, the ventral striatum, and the subthalamic nucleus. Stimulation of the inferior thalamic peduncle appeared to achieve better results, but this is a sketchy conclusion based upon two studies totaling just six patients (BMC Psychiatry. 2014 Aug 2;14:214. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0214-y).

Recently, Belgian investigators have reported particularly promising results – the best so far – for DBS targeting the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Mol Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;21[9]:1272-80).

Bilateral DBS appears to be more effective than unilateral.

Dr. Kohl and her colleagues in Cologne recently completed a study of DBS in 20 patients. She noted that it took 5 years to collect these 20 patients, underscoring the high bar that’s appropriate for resort to DBS, even though the therapy is approved for OCD by both the Food and Drug Administration and European regulatory authorities. Forty percent of the patients were DBS responders, with a mean 30% improvement in Y-BOCS scores. That’s a lower responder rate than in Dr. Denys’s and some other series, which Dr. Kohl attributed to the fact that in Germany, postimplantation CBT is not yet routine.

Asked about DBS side effects, the speakers agreed that they’re transient and fall off after initial stimulation parameters are changed.

“The most consistent and impressive side effect is that initially after surgical implantation of the electrodes and stimulation of the nucleus accumbens, patients experience 3 or 4 days of hypomania, which then disappears,” Dr. Denys said. “It causes a kind of imprinting, because even a decade later, patients ask us, ‘Could you bring back that really nice feeling?’ It’s 3 days of love, peace, and hypomania. It’s a side effect, but people like it.”

Dr. Denys and Dr. Kohl reported no financial conflicts of interest regarding their presentations.

VIENNA – Even though deep brain stimulation has been used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder in fewer than 300 patients worldwide, the therapy has had a huge impact on understanding of the disorder, Damiaan Denys, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Indeed, the efficacy of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in the most severe, treatment-refractory cases of OCD casts doubt upon the fundamental construct clinicians have relied upon for decades to comprehend OCD: Namely, that affected patients first experience obsessions, which induce anxiety, which then stimulates compulsions, and engaging in those compulsions brings relief and reward, and then the whole cycle starts over again.

That construct may not actually be true.

“Deep brain stimulation will force us to rethink OCD,” predicted Dr. Denys, professor and head of psychiatry at the University of Amsterdam.

What does DBS change, and is there a temporal order? It varies, the psychiatrist said.

“In some patients, anxiety is the first thing that changes. In others, it starts with obsessions. Compulsions do decrease, but it’s difficult. It takes some time, and often we need supplemental cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). What changes, mainly, in my experience, is not symptoms, but something outside of OCD: namely, mood. Deep brain stimulation has a huge impact on mood. That’s an interesting finding, because it suggests the possibility that you can change a psychiatric disorder by changing symptoms that are thought of as being outside the disorder,” Dr. Denys observed.

“Another interesting thing is that deep brain stimulation changes things that are not even within psychiatry. When we ask our patients what has been the most profound impact deep brain stimulation has had on their lives, all of them say, ‘It increases my self-confidence.’ And that’s not something that is included in our scales. We assess patients using the HAM-D [Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression] and Y-BOCS [Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale] and other measures, but there are still some very important aspects we are not taking into account and that have a profound effect on symptoms. In this case, using deep brain stimulation, we improve self-confidence and thereby change a whole chain of symptoms,” he continued.

Among the 60 highly refractory OCD patients treated by DBS by Dr. Denys and his colleagues at the Amsterdam center over the past 15 years, 15% were cured as a result.

“I purposely use the word ‘cured,’ because they don’t have obsessive-compulsive symptoms, anymore, which is, of course, extraordinary,” Dr. Denys noted.

An additional 35% of patients had a good response, defined as 60%-80% improvement on the Y-BOCS. Ten percent of patients were partial responders, with a 20%-40% improvement on the Y-BOCS. And 15% were nonresponders.

Closed-loop system coming

DBS entails implantation of electrodes deep within the brain to interrupt dysfunctional brain signals in local areas and across neural networks. This dysfunctional brain activity is expressed as symptoms. To date, DBS has been used in what’s called an open-loop system: Patients report the symptoms they’re experiencing and the clinician then adjusts the electrode settings in order to quell those symptoms. This approach is about to change. The technology has improved vastly since the early days, when the electrodes had four contact points. Now they have 64 contact points, and are capable of sending and receiving electrical signals.

“The next step in deep brain stimulation will be a closed-loop system. We will remove the clinician and the patient, and attempt to use a device capable of recording what happens in the brain and then changing electrical activity in response to the recordings. Our purpose will be to block these brain signals in advance of obsessions and compulsions so patients don’t have these symptoms. It’s technically possible. It has been done in Parkinson’s, and I think it’s the next step in psychiatry,” Dr. Denys said.

Indeed, he and his coinvestigators are planning formal studies of closed-loop DBS. For him, the prospect raises three key questions: What are the neural correlates of OCD symptoms? What about the ethics of implanting a device in the brain which by itself results in different life experiences? And will closed-loop DBS have superior efficacy, compared with open-loop DBS?

“How is the mind rooted in the brain, and how is the brain expressed in the mind? It’s the most fascinating question; it’s why we all love psychiatry, and up until now, there are no answers,” he observed.

Significant progress already has been made on the neural correlates question. Dr. Denys and his colleagues have found that when OCD patients with deep brain electrodes engage in cleaning compulsions, their local field potentials in the striatal area show peaks of roughly 9 Hz in the alpha range and in the beta/low gamma range. These patterns may represent compulsive behavior and likely could be useful in steering a closed-loop system. Also, the Dutch investigators have found that 3- to 8-Hz theta oscillations in local field potentials in the striatal area may represent a neural signature for anxiety and/or obsessions.

Using a closed-loop system, he continued, investigators plan to test two quite different hypotheses about the fundamental nature of OCD. One is that obsessions, anxiety, compulsions, and relief are each separately related to different brain areas. The other hypothesis is that one central brain stimulus drives the chain of symptoms that characterize OCD, and that by identifying and blocking that primary signal, the whole pathologic process can be stopped.

Current status of procedure

While Dr. Denys focused on the near future of DBS for OCD, another speaker at the session, Sina Kohl, PhD, addressed DBS for OCD as it exists today, particularly the who, how, and where.

The “who” is the relatively rare patient with truly refractory OCD after multiple drug trials of agents in different antidepressant classes, one of which should be clomipramine, as well as a failed course of CBT provided by an expert in CBT for OCD, of which there are relatively few. In a study led by investigators at Brown University, Providence, R.I., only 2 of 325 patients with OCD were deemed truly refractory (J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014 Winter;26[1]:81-6). That sounds about right, according to Dr. Kohl, a psychologist at the University of Cologne, in Germany.

The “how” is to deliver DBS in conjunction with CBT. Response rates are higher at centers where that practice is routine, she added.

The “where” is an unsettled question. In Dr. Kohl’s meta-analysis of 25 published DBS studies, electrode placement in four different DBS target structures produced similar results: the nucleus accumbens, the anterior limb of the internal capsule, the ventral striatum, and the subthalamic nucleus. Stimulation of the inferior thalamic peduncle appeared to achieve better results, but this is a sketchy conclusion based upon two studies totaling just six patients (BMC Psychiatry. 2014 Aug 2;14:214. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0214-y).

Recently, Belgian investigators have reported particularly promising results – the best so far – for DBS targeting the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Mol Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;21[9]:1272-80).

Bilateral DBS appears to be more effective than unilateral.

Dr. Kohl and her colleagues in Cologne recently completed a study of DBS in 20 patients. She noted that it took 5 years to collect these 20 patients, underscoring the high bar that’s appropriate for resort to DBS, even though the therapy is approved for OCD by both the Food and Drug Administration and European regulatory authorities. Forty percent of the patients were DBS responders, with a mean 30% improvement in Y-BOCS scores. That’s a lower responder rate than in Dr. Denys’s and some other series, which Dr. Kohl attributed to the fact that in Germany, postimplantation CBT is not yet routine.

Asked about DBS side effects, the speakers agreed that they’re transient and fall off after initial stimulation parameters are changed.

“The most consistent and impressive side effect is that initially after surgical implantation of the electrodes and stimulation of the nucleus accumbens, patients experience 3 or 4 days of hypomania, which then disappears,” Dr. Denys said. “It causes a kind of imprinting, because even a decade later, patients ask us, ‘Could you bring back that really nice feeling?’ It’s 3 days of love, peace, and hypomania. It’s a side effect, but people like it.”

Dr. Denys and Dr. Kohl reported no financial conflicts of interest regarding their presentations.

VIENNA – Even though deep brain stimulation has been used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder in fewer than 300 patients worldwide, the therapy has had a huge impact on understanding of the disorder, Damiaan Denys, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Indeed, the efficacy of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in the most severe, treatment-refractory cases of OCD casts doubt upon the fundamental construct clinicians have relied upon for decades to comprehend OCD: Namely, that affected patients first experience obsessions, which induce anxiety, which then stimulates compulsions, and engaging in those compulsions brings relief and reward, and then the whole cycle starts over again.

That construct may not actually be true.

“Deep brain stimulation will force us to rethink OCD,” predicted Dr. Denys, professor and head of psychiatry at the University of Amsterdam.

What does DBS change, and is there a temporal order? It varies, the psychiatrist said.

“In some patients, anxiety is the first thing that changes. In others, it starts with obsessions. Compulsions do decrease, but it’s difficult. It takes some time, and often we need supplemental cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). What changes, mainly, in my experience, is not symptoms, but something outside of OCD: namely, mood. Deep brain stimulation has a huge impact on mood. That’s an interesting finding, because it suggests the possibility that you can change a psychiatric disorder by changing symptoms that are thought of as being outside the disorder,” Dr. Denys observed.

“Another interesting thing is that deep brain stimulation changes things that are not even within psychiatry. When we ask our patients what has been the most profound impact deep brain stimulation has had on their lives, all of them say, ‘It increases my self-confidence.’ And that’s not something that is included in our scales. We assess patients using the HAM-D [Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression] and Y-BOCS [Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale] and other measures, but there are still some very important aspects we are not taking into account and that have a profound effect on symptoms. In this case, using deep brain stimulation, we improve self-confidence and thereby change a whole chain of symptoms,” he continued.

Among the 60 highly refractory OCD patients treated by DBS by Dr. Denys and his colleagues at the Amsterdam center over the past 15 years, 15% were cured as a result.

“I purposely use the word ‘cured,’ because they don’t have obsessive-compulsive symptoms, anymore, which is, of course, extraordinary,” Dr. Denys noted.

An additional 35% of patients had a good response, defined as 60%-80% improvement on the Y-BOCS. Ten percent of patients were partial responders, with a 20%-40% improvement on the Y-BOCS. And 15% were nonresponders.

Closed-loop system coming

DBS entails implantation of electrodes deep within the brain to interrupt dysfunctional brain signals in local areas and across neural networks. This dysfunctional brain activity is expressed as symptoms. To date, DBS has been used in what’s called an open-loop system: Patients report the symptoms they’re experiencing and the clinician then adjusts the electrode settings in order to quell those symptoms. This approach is about to change. The technology has improved vastly since the early days, when the electrodes had four contact points. Now they have 64 contact points, and are capable of sending and receiving electrical signals.

“The next step in deep brain stimulation will be a closed-loop system. We will remove the clinician and the patient, and attempt to use a device capable of recording what happens in the brain and then changing electrical activity in response to the recordings. Our purpose will be to block these brain signals in advance of obsessions and compulsions so patients don’t have these symptoms. It’s technically possible. It has been done in Parkinson’s, and I think it’s the next step in psychiatry,” Dr. Denys said.

Indeed, he and his coinvestigators are planning formal studies of closed-loop DBS. For him, the prospect raises three key questions: What are the neural correlates of OCD symptoms? What about the ethics of implanting a device in the brain which by itself results in different life experiences? And will closed-loop DBS have superior efficacy, compared with open-loop DBS?

“How is the mind rooted in the brain, and how is the brain expressed in the mind? It’s the most fascinating question; it’s why we all love psychiatry, and up until now, there are no answers,” he observed.

Significant progress already has been made on the neural correlates question. Dr. Denys and his colleagues have found that when OCD patients with deep brain electrodes engage in cleaning compulsions, their local field potentials in the striatal area show peaks of roughly 9 Hz in the alpha range and in the beta/low gamma range. These patterns may represent compulsive behavior and likely could be useful in steering a closed-loop system. Also, the Dutch investigators have found that 3- to 8-Hz theta oscillations in local field potentials in the striatal area may represent a neural signature for anxiety and/or obsessions.

Using a closed-loop system, he continued, investigators plan to test two quite different hypotheses about the fundamental nature of OCD. One is that obsessions, anxiety, compulsions, and relief are each separately related to different brain areas. The other hypothesis is that one central brain stimulus drives the chain of symptoms that characterize OCD, and that by identifying and blocking that primary signal, the whole pathologic process can be stopped.

Current status of procedure

While Dr. Denys focused on the near future of DBS for OCD, another speaker at the session, Sina Kohl, PhD, addressed DBS for OCD as it exists today, particularly the who, how, and where.

The “who” is the relatively rare patient with truly refractory OCD after multiple drug trials of agents in different antidepressant classes, one of which should be clomipramine, as well as a failed course of CBT provided by an expert in CBT for OCD, of which there are relatively few. In a study led by investigators at Brown University, Providence, R.I., only 2 of 325 patients with OCD were deemed truly refractory (J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014 Winter;26[1]:81-6). That sounds about right, according to Dr. Kohl, a psychologist at the University of Cologne, in Germany.

The “how” is to deliver DBS in conjunction with CBT. Response rates are higher at centers where that practice is routine, she added.

The “where” is an unsettled question. In Dr. Kohl’s meta-analysis of 25 published DBS studies, electrode placement in four different DBS target structures produced similar results: the nucleus accumbens, the anterior limb of the internal capsule, the ventral striatum, and the subthalamic nucleus. Stimulation of the inferior thalamic peduncle appeared to achieve better results, but this is a sketchy conclusion based upon two studies totaling just six patients (BMC Psychiatry. 2014 Aug 2;14:214. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0214-y).

Recently, Belgian investigators have reported particularly promising results – the best so far – for DBS targeting the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Mol Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;21[9]:1272-80).

Bilateral DBS appears to be more effective than unilateral.

Dr. Kohl and her colleagues in Cologne recently completed a study of DBS in 20 patients. She noted that it took 5 years to collect these 20 patients, underscoring the high bar that’s appropriate for resort to DBS, even though the therapy is approved for OCD by both the Food and Drug Administration and European regulatory authorities. Forty percent of the patients were DBS responders, with a mean 30% improvement in Y-BOCS scores. That’s a lower responder rate than in Dr. Denys’s and some other series, which Dr. Kohl attributed to the fact that in Germany, postimplantation CBT is not yet routine.

Asked about DBS side effects, the speakers agreed that they’re transient and fall off after initial stimulation parameters are changed.

“The most consistent and impressive side effect is that initially after surgical implantation of the electrodes and stimulation of the nucleus accumbens, patients experience 3 or 4 days of hypomania, which then disappears,” Dr. Denys said. “It causes a kind of imprinting, because even a decade later, patients ask us, ‘Could you bring back that really nice feeling?’ It’s 3 days of love, peace, and hypomania. It’s a side effect, but people like it.”

Dr. Denys and Dr. Kohl reported no financial conflicts of interest regarding their presentations.

Parental Feelings of Helplessness Predict Quality of Life in Children With Epilepsy

HOUSTON—The degree of helplessness that parents experience about their child’s epilepsy is significantly related to the child’s health-related quality of life, according to research presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “This relationship highlights the importance of taking into account a parent’s ability to cope … and should be an important target when developing interventions for families who have a child with epilepsy,” said Rachael McLaughlin, a research assistant in neuropsychology at Dell Children’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Program in Austin, and colleagues.

Prior studies have found that psychosocial factors can play a role in the health-related quality of life of children with epilepsy. Parents’ adaptation to their child’s epilepsy is not often taken into account, however.

Mrs. McLaughlin and her research colleagues at Dell Children’s, William Schraegle, Nancy Nussbaum, PhD, and Jeffrey Titus, PhD, conducted a study using the Illness Cognition Questionnaire–Parent Version (ICQ). The ICQ assesses parents’ thoughts of helplessness, acceptance, and perceived benefits related to the illness. They studied how parental coping relates to a child’s internalizing psychopathology and health-related quality of life in the context of epilepsy.

The researchers analyzed data from 40 patients (23 females) who were seen for a neuropsychologic evaluation at a tertiary pediatric care epilepsy clinic. Parents completed the ICQ, Quality of Life Childhood Epilepsy (QOLCE) questionnaire, and the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition. They obtained family history of internalizing psychopathology, duration of epilepsy, and maternal education level from medical records. They assessed associations between parental, demographic, epilepsy-specific, behavioral, and functional variables. The researchers then assessed whether independent variables predicted quality of life.

Patients had an average age of 12 and average epilepsy duration of about six years. QOLCE was related to parental helplessness and acceptance on the ICQ, and to internalizing and externalizing psychopathology.

A simultaneous regression model found that parental helplessness and internalizing psychopathology predicted quality of life, with parental helplessness accounting for the most variance above and beyond all other variables. Analysis of variance found that parental helplessness significantly affected QOLCE. When divided by parental helplessness, patients whose parents had high levels of helplessness had significantly lower quality of life than patients whose parents had low levels of helplessness.

—Jake Remaly

HOUSTON—The degree of helplessness that parents experience about their child’s epilepsy is significantly related to the child’s health-related quality of life, according to research presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “This relationship highlights the importance of taking into account a parent’s ability to cope … and should be an important target when developing interventions for families who have a child with epilepsy,” said Rachael McLaughlin, a research assistant in neuropsychology at Dell Children’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Program in Austin, and colleagues.

Prior studies have found that psychosocial factors can play a role in the health-related quality of life of children with epilepsy. Parents’ adaptation to their child’s epilepsy is not often taken into account, however.

Mrs. McLaughlin and her research colleagues at Dell Children’s, William Schraegle, Nancy Nussbaum, PhD, and Jeffrey Titus, PhD, conducted a study using the Illness Cognition Questionnaire–Parent Version (ICQ). The ICQ assesses parents’ thoughts of helplessness, acceptance, and perceived benefits related to the illness. They studied how parental coping relates to a child’s internalizing psychopathology and health-related quality of life in the context of epilepsy.

The researchers analyzed data from 40 patients (23 females) who were seen for a neuropsychologic evaluation at a tertiary pediatric care epilepsy clinic. Parents completed the ICQ, Quality of Life Childhood Epilepsy (QOLCE) questionnaire, and the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition. They obtained family history of internalizing psychopathology, duration of epilepsy, and maternal education level from medical records. They assessed associations between parental, demographic, epilepsy-specific, behavioral, and functional variables. The researchers then assessed whether independent variables predicted quality of life.

Patients had an average age of 12 and average epilepsy duration of about six years. QOLCE was related to parental helplessness and acceptance on the ICQ, and to internalizing and externalizing psychopathology.

A simultaneous regression model found that parental helplessness and internalizing psychopathology predicted quality of life, with parental helplessness accounting for the most variance above and beyond all other variables. Analysis of variance found that parental helplessness significantly affected QOLCE. When divided by parental helplessness, patients whose parents had high levels of helplessness had significantly lower quality of life than patients whose parents had low levels of helplessness.

—Jake Remaly

HOUSTON—The degree of helplessness that parents experience about their child’s epilepsy is significantly related to the child’s health-related quality of life, according to research presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “This relationship highlights the importance of taking into account a parent’s ability to cope … and should be an important target when developing interventions for families who have a child with epilepsy,” said Rachael McLaughlin, a research assistant in neuropsychology at Dell Children’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Program in Austin, and colleagues.

Prior studies have found that psychosocial factors can play a role in the health-related quality of life of children with epilepsy. Parents’ adaptation to their child’s epilepsy is not often taken into account, however.

Mrs. McLaughlin and her research colleagues at Dell Children’s, William Schraegle, Nancy Nussbaum, PhD, and Jeffrey Titus, PhD, conducted a study using the Illness Cognition Questionnaire–Parent Version (ICQ). The ICQ assesses parents’ thoughts of helplessness, acceptance, and perceived benefits related to the illness. They studied how parental coping relates to a child’s internalizing psychopathology and health-related quality of life in the context of epilepsy.

The researchers analyzed data from 40 patients (23 females) who were seen for a neuropsychologic evaluation at a tertiary pediatric care epilepsy clinic. Parents completed the ICQ, Quality of Life Childhood Epilepsy (QOLCE) questionnaire, and the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition. They obtained family history of internalizing psychopathology, duration of epilepsy, and maternal education level from medical records. They assessed associations between parental, demographic, epilepsy-specific, behavioral, and functional variables. The researchers then assessed whether independent variables predicted quality of life.

Patients had an average age of 12 and average epilepsy duration of about six years. QOLCE was related to parental helplessness and acceptance on the ICQ, and to internalizing and externalizing psychopathology.

A simultaneous regression model found that parental helplessness and internalizing psychopathology predicted quality of life, with parental helplessness accounting for the most variance above and beyond all other variables. Analysis of variance found that parental helplessness significantly affected QOLCE. When divided by parental helplessness, patients whose parents had high levels of helplessness had significantly lower quality of life than patients whose parents had low levels of helplessness.

—Jake Remaly

Detecting Autoimmune Neural Antibodies Is Key to Preventing Misdiagnosis

LAS VEGAS—Advances in autoimmune neurology, a rapidly evolving field, have the potential to prevent misdiagnosis of many disorders, from multiple sclerosis to neurodegenerative diseases. The key: increased detection of autoimmune and paraneoplastic neural antibodies, said Sean J. Pittock, MD, at the American Academy of Neurology’s Fall 2016 Conference. The importance of autoimmune neurology “cannot be overstated because these are reversible, treatable conditions,” Dr. Pittock said. “If you miss them, you have done your patients a disservice.”

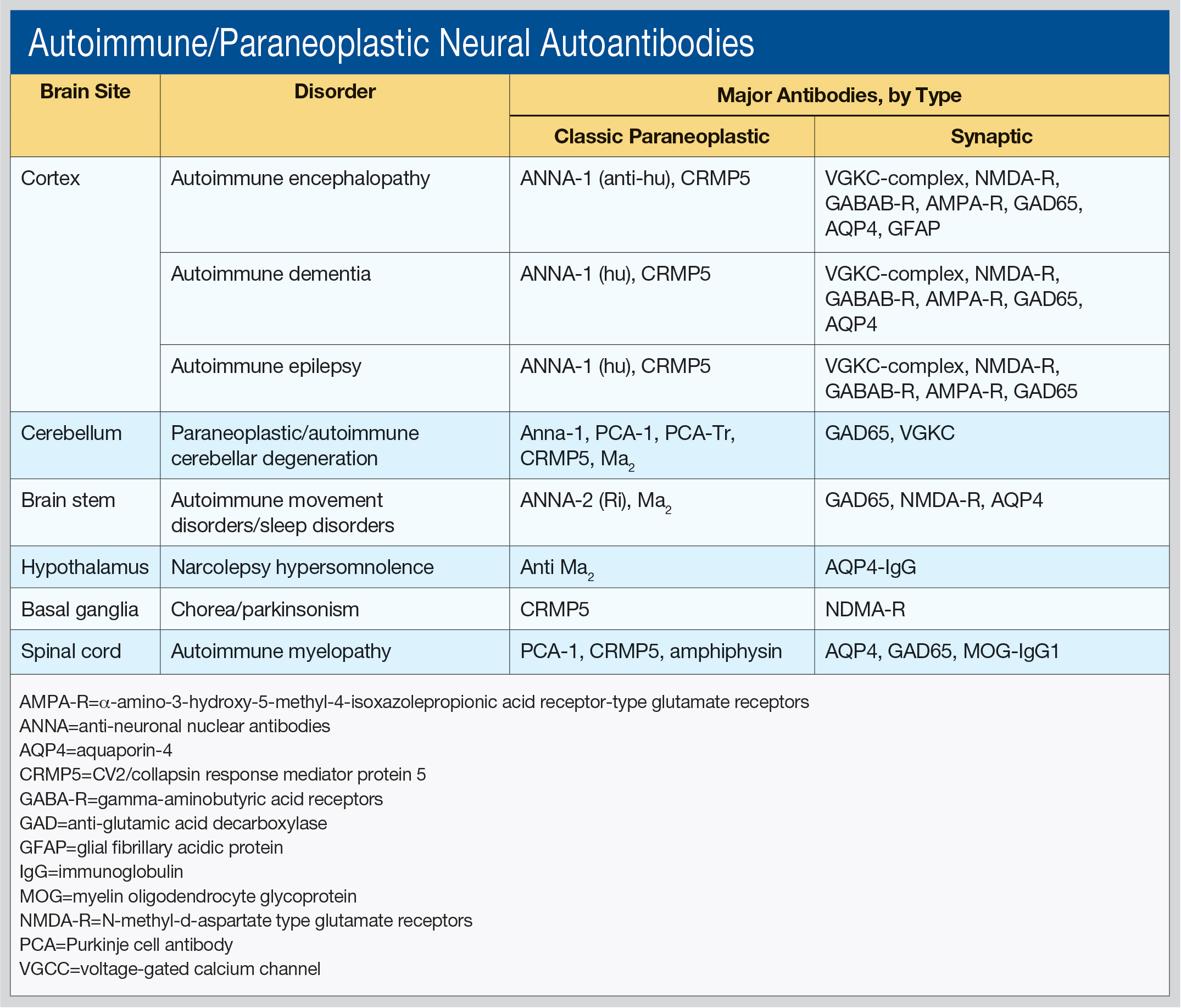

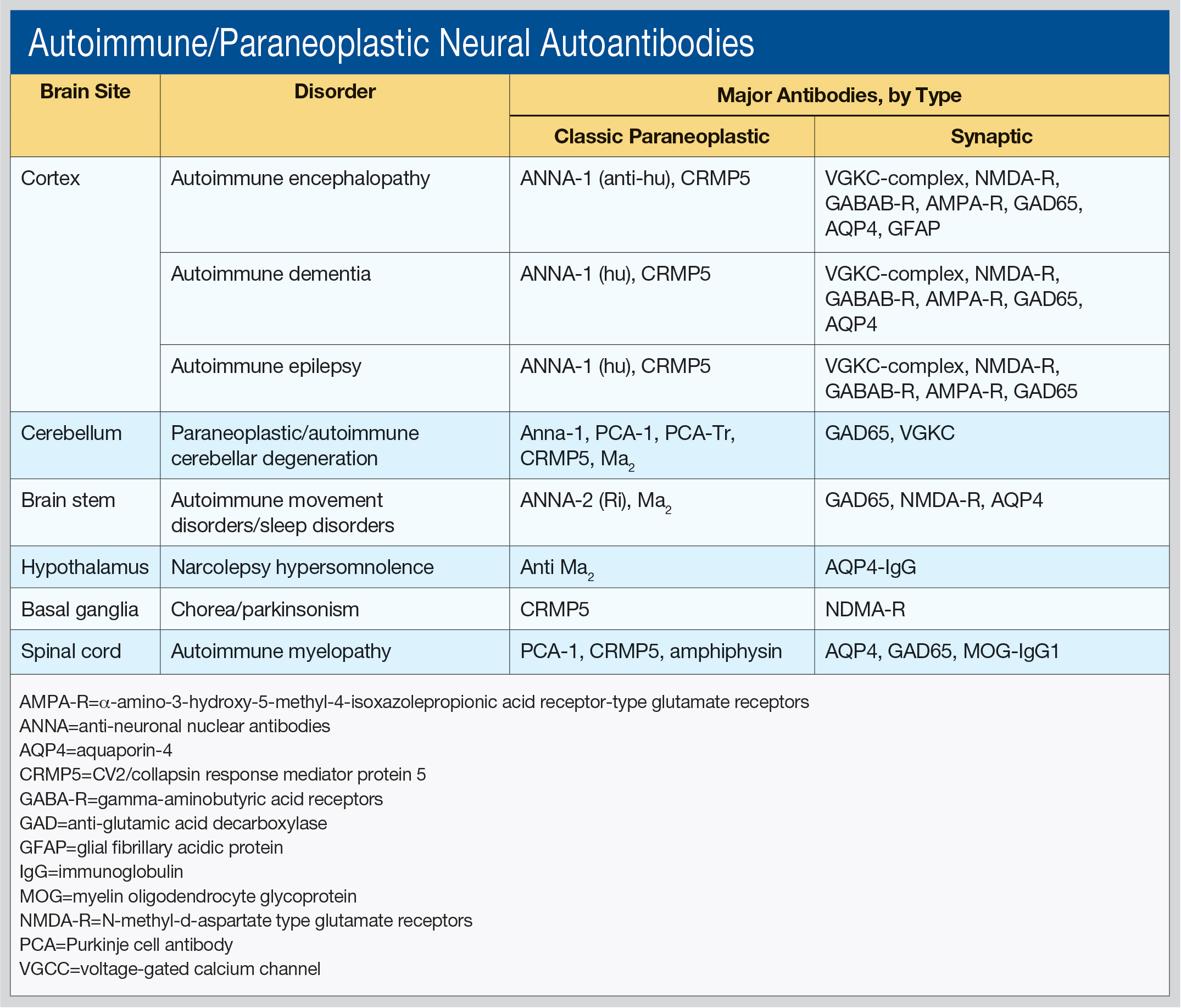

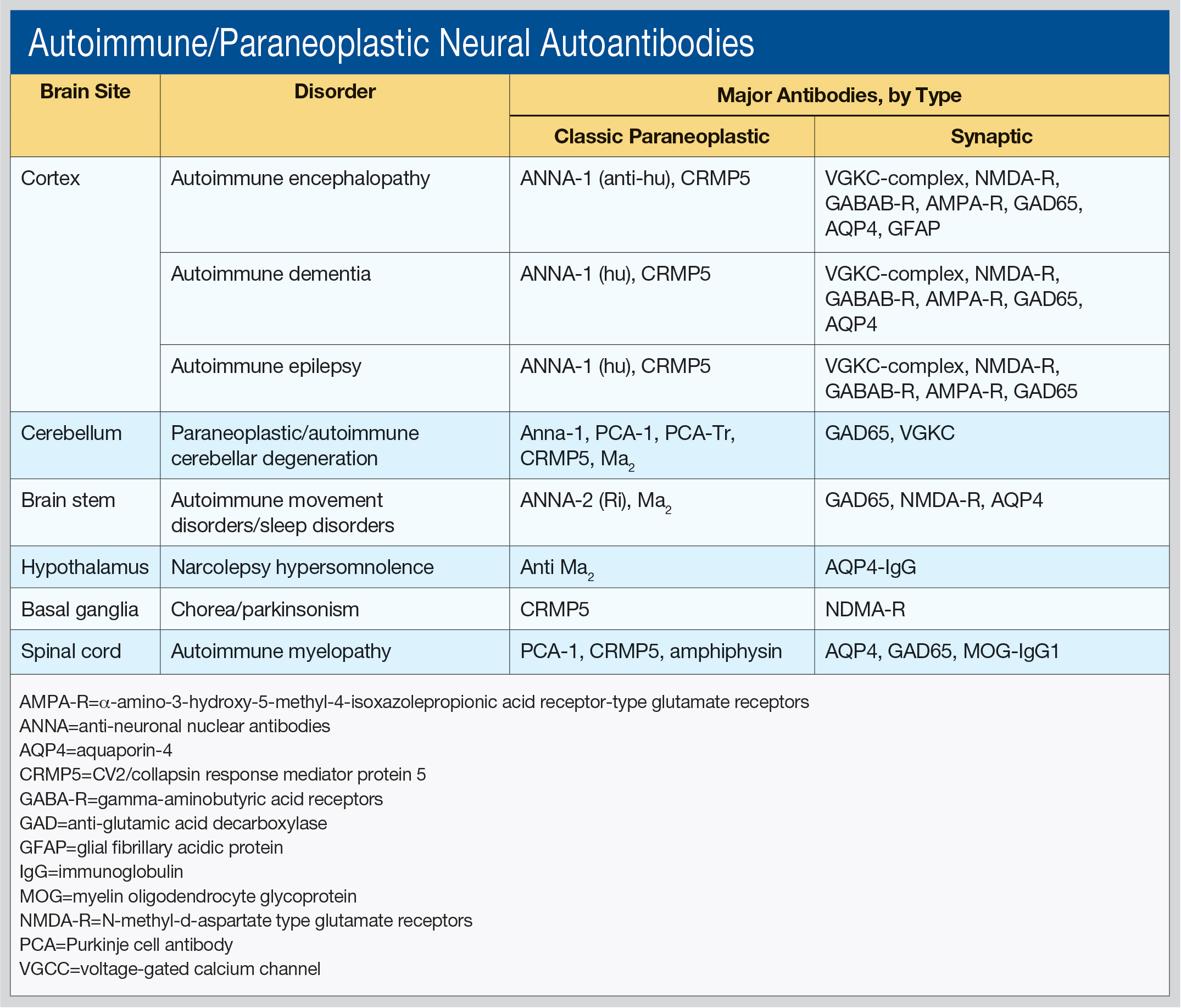

Dr. Pittock, Professor of Neurology, Director of the Neuroimmunology Laboratory, and Director of the Center for MS and Autoimmune Neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said he works primarily “in the field of discovering novel antibodies that make sense to the clinician.” He outlined these antibodies by brain site (cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and spinal cord), as well as associated disorders and type of antibodies (see table).

“Different antibodies tell you what cancers you should be looking for,” he said. The classic paraneoplastic antibodies have oncological associations with small cell and aerodigestive carcinomas, breast and gynecologic adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, and thymoma. The synaptic antibodies are associated with prostate, lung, thymic, and endometrial carcinomas, as well as with teratoma.

In his laboratory, Dr. Pittock uses a complex algorithm to test for 20 types of neural antibodies using diverse methodologies, from indirect immunofluorescence to cell-based and immunoprecipitation assays. Results are usually available within six to eight days. “We are moving towards a movement disorder evaluation, a CNS hyperexcitability evaluation, and a demyelinating disease evaluation,” he said.

“In paraneoplastic disorders, the tumors are often difficult to find,” Dr. Pittock said. “The immune system is having a dramatic impact on the tumor, and so these tumors are very small, so you may miss them.”

Dr. Pittock provided an overview of how clinicians might approach diagnosing autoimmune disorders. “For children, obviously, anaplastic diseases are rare, but if you have a patient with opsoclonus myoclonus, 50% of those children will have a cancer. For adolescents and young females, you always think about teratoma. If it is a young man, you really need to think about testicular tumors.”

The type of cancer defines what type of investigation is appropriate, he said. For example, due to low resolution, PET scans are not as useful for thymoma, teratoma, or testicular or gastrointestinal tumors. On the other hand, PET scans can help evaluate equivocal findings, such as pulmonary nodules or lymph nodes. With the exception of Medicare, however, PET scans are not generally covered by insurance. Medicare covers PET scanning under ICD-9 code V71.1, “observation for suspected malignant neoplasm,” and ICD-10, Z12, “encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm”; Z12.9, “site unspecified.”

At the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Pittock said they see five patients per week with NMDA-receptor encephalitis. To diagnose a possible autoimmune neurologic disorder, he asked that clinicians “please consider using the concept of immunotherapy as kind of a diagnostic test.” To do so, the patient should be treated acutely with IV methylprednisolone, IVIg, or plasma exchanges. If the patient improves, continue acute IV therapy and taper oral prednisone; other options include oral azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. If the patient does not improve, consider alternative acute therapy or no further therapy.

In one study that he and his colleagues conducted, 81% of patients who had failed antiepileptic drugs (AED) and were having daily seizures were treated with such a diagnostic test. Of these, 62% responded and 34% of patients became seizure-free. In contrast, Dr. Pittock said, patients treated with a third AED in a trial rarely experience meaningful improvement.

An autoimmune condition may also have a neuropsychiatric presentation. Dr. Pittock urged attendees to watch a recent film based on the 2013 book, “Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness,” by Susannah Cahalan, who went from psychosis to catatonia before a physician determined she had brain inflammation due to an autoimmune reaction.

“Many of these patients previously would have ended up in a psychiatric institution or in an ICU setting where, potentially, in the setting of intractable disease, they may have had their machine turned off, they may have died, when they have the potential to make a full recovery and, sometimes, spontaneously improve. The take-home message for this one is, if you want to investigate a patient with this, test spinal fluid.

“Autoimmune neurology is here to stay. It is a new field; it is very exciting; it has just been recognized by the American Academy of Neurology as having its own section,” Dr. Pittock said, and invited those interested to join.

Dr. Pittock has received research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

—Debra Hughes

Suggested Reading

Linnoila J, Pittock SJ. Autoantibody-associated central nervous system neurologic disorders. Semin Neurol. 2016;36(4):382-396.

Toledano M, Britton JW, McKeon A, et al. Utility of an immunotherapy trial in evaluating patients with presumed autoimmune epilepsy. Neurology. 2014;82(18):1578-1586.

LAS VEGAS—Advances in autoimmune neurology, a rapidly evolving field, have the potential to prevent misdiagnosis of many disorders, from multiple sclerosis to neurodegenerative diseases. The key: increased detection of autoimmune and paraneoplastic neural antibodies, said Sean J. Pittock, MD, at the American Academy of Neurology’s Fall 2016 Conference. The importance of autoimmune neurology “cannot be overstated because these are reversible, treatable conditions,” Dr. Pittock said. “If you miss them, you have done your patients a disservice.”

Dr. Pittock, Professor of Neurology, Director of the Neuroimmunology Laboratory, and Director of the Center for MS and Autoimmune Neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said he works primarily “in the field of discovering novel antibodies that make sense to the clinician.” He outlined these antibodies by brain site (cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and spinal cord), as well as associated disorders and type of antibodies (see table).

“Different antibodies tell you what cancers you should be looking for,” he said. The classic paraneoplastic antibodies have oncological associations with small cell and aerodigestive carcinomas, breast and gynecologic adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, and thymoma. The synaptic antibodies are associated with prostate, lung, thymic, and endometrial carcinomas, as well as with teratoma.

In his laboratory, Dr. Pittock uses a complex algorithm to test for 20 types of neural antibodies using diverse methodologies, from indirect immunofluorescence to cell-based and immunoprecipitation assays. Results are usually available within six to eight days. “We are moving towards a movement disorder evaluation, a CNS hyperexcitability evaluation, and a demyelinating disease evaluation,” he said.

“In paraneoplastic disorders, the tumors are often difficult to find,” Dr. Pittock said. “The immune system is having a dramatic impact on the tumor, and so these tumors are very small, so you may miss them.”

Dr. Pittock provided an overview of how clinicians might approach diagnosing autoimmune disorders. “For children, obviously, anaplastic diseases are rare, but if you have a patient with opsoclonus myoclonus, 50% of those children will have a cancer. For adolescents and young females, you always think about teratoma. If it is a young man, you really need to think about testicular tumors.”

The type of cancer defines what type of investigation is appropriate, he said. For example, due to low resolution, PET scans are not as useful for thymoma, teratoma, or testicular or gastrointestinal tumors. On the other hand, PET scans can help evaluate equivocal findings, such as pulmonary nodules or lymph nodes. With the exception of Medicare, however, PET scans are not generally covered by insurance. Medicare covers PET scanning under ICD-9 code V71.1, “observation for suspected malignant neoplasm,” and ICD-10, Z12, “encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm”; Z12.9, “site unspecified.”

At the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Pittock said they see five patients per week with NMDA-receptor encephalitis. To diagnose a possible autoimmune neurologic disorder, he asked that clinicians “please consider using the concept of immunotherapy as kind of a diagnostic test.” To do so, the patient should be treated acutely with IV methylprednisolone, IVIg, or plasma exchanges. If the patient improves, continue acute IV therapy and taper oral prednisone; other options include oral azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. If the patient does not improve, consider alternative acute therapy or no further therapy.

In one study that he and his colleagues conducted, 81% of patients who had failed antiepileptic drugs (AED) and were having daily seizures were treated with such a diagnostic test. Of these, 62% responded and 34% of patients became seizure-free. In contrast, Dr. Pittock said, patients treated with a third AED in a trial rarely experience meaningful improvement.

An autoimmune condition may also have a neuropsychiatric presentation. Dr. Pittock urged attendees to watch a recent film based on the 2013 book, “Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness,” by Susannah Cahalan, who went from psychosis to catatonia before a physician determined she had brain inflammation due to an autoimmune reaction.

“Many of these patients previously would have ended up in a psychiatric institution or in an ICU setting where, potentially, in the setting of intractable disease, they may have had their machine turned off, they may have died, when they have the potential to make a full recovery and, sometimes, spontaneously improve. The take-home message for this one is, if you want to investigate a patient with this, test spinal fluid.

“Autoimmune neurology is here to stay. It is a new field; it is very exciting; it has just been recognized by the American Academy of Neurology as having its own section,” Dr. Pittock said, and invited those interested to join.

Dr. Pittock has received research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

—Debra Hughes

Suggested Reading

Linnoila J, Pittock SJ. Autoantibody-associated central nervous system neurologic disorders. Semin Neurol. 2016;36(4):382-396.

Toledano M, Britton JW, McKeon A, et al. Utility of an immunotherapy trial in evaluating patients with presumed autoimmune epilepsy. Neurology. 2014;82(18):1578-1586.

LAS VEGAS—Advances in autoimmune neurology, a rapidly evolving field, have the potential to prevent misdiagnosis of many disorders, from multiple sclerosis to neurodegenerative diseases. The key: increased detection of autoimmune and paraneoplastic neural antibodies, said Sean J. Pittock, MD, at the American Academy of Neurology’s Fall 2016 Conference. The importance of autoimmune neurology “cannot be overstated because these are reversible, treatable conditions,” Dr. Pittock said. “If you miss them, you have done your patients a disservice.”

Dr. Pittock, Professor of Neurology, Director of the Neuroimmunology Laboratory, and Director of the Center for MS and Autoimmune Neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said he works primarily “in the field of discovering novel antibodies that make sense to the clinician.” He outlined these antibodies by brain site (cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and spinal cord), as well as associated disorders and type of antibodies (see table).

“Different antibodies tell you what cancers you should be looking for,” he said. The classic paraneoplastic antibodies have oncological associations with small cell and aerodigestive carcinomas, breast and gynecologic adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, and thymoma. The synaptic antibodies are associated with prostate, lung, thymic, and endometrial carcinomas, as well as with teratoma.

In his laboratory, Dr. Pittock uses a complex algorithm to test for 20 types of neural antibodies using diverse methodologies, from indirect immunofluorescence to cell-based and immunoprecipitation assays. Results are usually available within six to eight days. “We are moving towards a movement disorder evaluation, a CNS hyperexcitability evaluation, and a demyelinating disease evaluation,” he said.

“In paraneoplastic disorders, the tumors are often difficult to find,” Dr. Pittock said. “The immune system is having a dramatic impact on the tumor, and so these tumors are very small, so you may miss them.”

Dr. Pittock provided an overview of how clinicians might approach diagnosing autoimmune disorders. “For children, obviously, anaplastic diseases are rare, but if you have a patient with opsoclonus myoclonus, 50% of those children will have a cancer. For adolescents and young females, you always think about teratoma. If it is a young man, you really need to think about testicular tumors.”

The type of cancer defines what type of investigation is appropriate, he said. For example, due to low resolution, PET scans are not as useful for thymoma, teratoma, or testicular or gastrointestinal tumors. On the other hand, PET scans can help evaluate equivocal findings, such as pulmonary nodules or lymph nodes. With the exception of Medicare, however, PET scans are not generally covered by insurance. Medicare covers PET scanning under ICD-9 code V71.1, “observation for suspected malignant neoplasm,” and ICD-10, Z12, “encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm”; Z12.9, “site unspecified.”

At the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Pittock said they see five patients per week with NMDA-receptor encephalitis. To diagnose a possible autoimmune neurologic disorder, he asked that clinicians “please consider using the concept of immunotherapy as kind of a diagnostic test.” To do so, the patient should be treated acutely with IV methylprednisolone, IVIg, or plasma exchanges. If the patient improves, continue acute IV therapy and taper oral prednisone; other options include oral azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. If the patient does not improve, consider alternative acute therapy or no further therapy.

In one study that he and his colleagues conducted, 81% of patients who had failed antiepileptic drugs (AED) and were having daily seizures were treated with such a diagnostic test. Of these, 62% responded and 34% of patients became seizure-free. In contrast, Dr. Pittock said, patients treated with a third AED in a trial rarely experience meaningful improvement.

An autoimmune condition may also have a neuropsychiatric presentation. Dr. Pittock urged attendees to watch a recent film based on the 2013 book, “Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness,” by Susannah Cahalan, who went from psychosis to catatonia before a physician determined she had brain inflammation due to an autoimmune reaction.

“Many of these patients previously would have ended up in a psychiatric institution or in an ICU setting where, potentially, in the setting of intractable disease, they may have had their machine turned off, they may have died, when they have the potential to make a full recovery and, sometimes, spontaneously improve. The take-home message for this one is, if you want to investigate a patient with this, test spinal fluid.

“Autoimmune neurology is here to stay. It is a new field; it is very exciting; it has just been recognized by the American Academy of Neurology as having its own section,” Dr. Pittock said, and invited those interested to join.

Dr. Pittock has received research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

—Debra Hughes

Suggested Reading

Linnoila J, Pittock SJ. Autoantibody-associated central nervous system neurologic disorders. Semin Neurol. 2016;36(4):382-396.

Toledano M, Britton JW, McKeon A, et al. Utility of an immunotherapy trial in evaluating patients with presumed autoimmune epilepsy. Neurology. 2014;82(18):1578-1586.

Gene Mutation Linked to Early Onset of Parkinson’s Disease

A defect in a gene that produces dopamine in nigrostriatal cells appears to accelerate the onset of Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published in the February issue of Neurobiology of Aging. The effect is particularly pronounced for people younger than 50.

Auriel Willette, PhD, an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Food Science and Human Nutrition and Psychology at Iowa State University in Ames, and Joseph Webb, a graduate research assistant also at Iowa State, found on average that Caucasians with one mutated version of the gene—guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase-1 (GCH1)—had a 23% increased risk for Parkinson’s disease and developed symptoms five years earlier than those without the gene mutation.

However, young-to-middle-aged adults with the mutation had a 45% increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Researchers said that the presence of the mutated gene in older adults had minimal effect.

The Potential for Personalized Medicine

It is widely known that rigidity and loss of muscle function associated with Parkinson’s disease are linked to a depletion of dopamine in the substantia nigra. Taking a holistic approach to their study, Dr. Willette and Mr. Webb sought to better understand how the GCH1 gene affects the course of Parkinson’s disease and certain outcomes such as motor skills and anxiety.

The study is the first to look at these biological markers, as well as the first to examine how the gene’s impact on dopamine production specifically affects Caucasian populations. Previous studies have focused primarily on Chinese and Taiwanese populations, said Dr. Willette. The findings have the potential to help personalize medical care for people with a family history of Parkinson’s disease, he said, in a way similar to testing for the BRCA gene in women at risk for breast cancer.

“We want to have a more comprehensive understanding of what these genes related to Parkinson’s disease are doing at different points in someone’s lifetime,” Dr. Willette said. “Then, with genetic testing we can determine the risk for illness based on someone’s age, gender, weight, and other intervening factors.”

The Impact of Age

Data for the study were collected through the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative, a public–private partnership sponsored by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. The initiative evaluates people with the disease to develop new and better treatments. The Iowa State study included 289 treatment-naïve people recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and 233 healthy controls.

The researchers analyzed anxiety and motor function using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). They found that those with polymorphisms at rs11158026 coding for the GCH1 enzyme, regardless of age, were more anxious and struggled more with daily activities. The defective gene was not as strong of a predictor of developing Parkinson’s disease in people older than 50, however.

“As we age, we make progressively less dopamine, and this effect strongly outweighs the genetic influences from the ‘bad version’ of this gene,” said Mr. Webb. “Simply by aging, our dopamine production decreases to the point that the effects from a mutation in this gene are not noticeable in older adults, but make a big difference in younger populations.”

The researchers noted that it is also important to pay attention to blood cholesterol levels. Cholesterol is directly related to the ability to produce dopamine. High low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is an established risk factor for Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Willette said. Their study shows that carriers of the mutated GCH1 gene had higher cholesterol than noncarriers, regardless of age.

Suggested Reading

Webb J, Willette AA. Aging modifies the effect of GCH1 RS11158026 on DAT uptake and Parkinson’s disease clinical severity. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;50:39-46.

A defect in a gene that produces dopamine in nigrostriatal cells appears to accelerate the onset of Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published in the February issue of Neurobiology of Aging. The effect is particularly pronounced for people younger than 50.

Auriel Willette, PhD, an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Food Science and Human Nutrition and Psychology at Iowa State University in Ames, and Joseph Webb, a graduate research assistant also at Iowa State, found on average that Caucasians with one mutated version of the gene—guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase-1 (GCH1)—had a 23% increased risk for Parkinson’s disease and developed symptoms five years earlier than those without the gene mutation.

However, young-to-middle-aged adults with the mutation had a 45% increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Researchers said that the presence of the mutated gene in older adults had minimal effect.

The Potential for Personalized Medicine

It is widely known that rigidity and loss of muscle function associated with Parkinson’s disease are linked to a depletion of dopamine in the substantia nigra. Taking a holistic approach to their study, Dr. Willette and Mr. Webb sought to better understand how the GCH1 gene affects the course of Parkinson’s disease and certain outcomes such as motor skills and anxiety.

The study is the first to look at these biological markers, as well as the first to examine how the gene’s impact on dopamine production specifically affects Caucasian populations. Previous studies have focused primarily on Chinese and Taiwanese populations, said Dr. Willette. The findings have the potential to help personalize medical care for people with a family history of Parkinson’s disease, he said, in a way similar to testing for the BRCA gene in women at risk for breast cancer.

“We want to have a more comprehensive understanding of what these genes related to Parkinson’s disease are doing at different points in someone’s lifetime,” Dr. Willette said. “Then, with genetic testing we can determine the risk for illness based on someone’s age, gender, weight, and other intervening factors.”

The Impact of Age

Data for the study were collected through the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative, a public–private partnership sponsored by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. The initiative evaluates people with the disease to develop new and better treatments. The Iowa State study included 289 treatment-naïve people recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and 233 healthy controls.

The researchers analyzed anxiety and motor function using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). They found that those with polymorphisms at rs11158026 coding for the GCH1 enzyme, regardless of age, were more anxious and struggled more with daily activities. The defective gene was not as strong of a predictor of developing Parkinson’s disease in people older than 50, however.

“As we age, we make progressively less dopamine, and this effect strongly outweighs the genetic influences from the ‘bad version’ of this gene,” said Mr. Webb. “Simply by aging, our dopamine production decreases to the point that the effects from a mutation in this gene are not noticeable in older adults, but make a big difference in younger populations.”

The researchers noted that it is also important to pay attention to blood cholesterol levels. Cholesterol is directly related to the ability to produce dopamine. High low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is an established risk factor for Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Willette said. Their study shows that carriers of the mutated GCH1 gene had higher cholesterol than noncarriers, regardless of age.

Suggested Reading

Webb J, Willette AA. Aging modifies the effect of GCH1 RS11158026 on DAT uptake and Parkinson’s disease clinical severity. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;50:39-46.

A defect in a gene that produces dopamine in nigrostriatal cells appears to accelerate the onset of Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published in the February issue of Neurobiology of Aging. The effect is particularly pronounced for people younger than 50.

Auriel Willette, PhD, an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Food Science and Human Nutrition and Psychology at Iowa State University in Ames, and Joseph Webb, a graduate research assistant also at Iowa State, found on average that Caucasians with one mutated version of the gene—guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase-1 (GCH1)—had a 23% increased risk for Parkinson’s disease and developed symptoms five years earlier than those without the gene mutation.

However, young-to-middle-aged adults with the mutation had a 45% increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Researchers said that the presence of the mutated gene in older adults had minimal effect.

The Potential for Personalized Medicine

It is widely known that rigidity and loss of muscle function associated with Parkinson’s disease are linked to a depletion of dopamine in the substantia nigra. Taking a holistic approach to their study, Dr. Willette and Mr. Webb sought to better understand how the GCH1 gene affects the course of Parkinson’s disease and certain outcomes such as motor skills and anxiety.

The study is the first to look at these biological markers, as well as the first to examine how the gene’s impact on dopamine production specifically affects Caucasian populations. Previous studies have focused primarily on Chinese and Taiwanese populations, said Dr. Willette. The findings have the potential to help personalize medical care for people with a family history of Parkinson’s disease, he said, in a way similar to testing for the BRCA gene in women at risk for breast cancer.

“We want to have a more comprehensive understanding of what these genes related to Parkinson’s disease are doing at different points in someone’s lifetime,” Dr. Willette said. “Then, with genetic testing we can determine the risk for illness based on someone’s age, gender, weight, and other intervening factors.”

The Impact of Age

Data for the study were collected through the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative, a public–private partnership sponsored by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. The initiative evaluates people with the disease to develop new and better treatments. The Iowa State study included 289 treatment-naïve people recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and 233 healthy controls.

The researchers analyzed anxiety and motor function using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). They found that those with polymorphisms at rs11158026 coding for the GCH1 enzyme, regardless of age, were more anxious and struggled more with daily activities. The defective gene was not as strong of a predictor of developing Parkinson’s disease in people older than 50, however.

“As we age, we make progressively less dopamine, and this effect strongly outweighs the genetic influences from the ‘bad version’ of this gene,” said Mr. Webb. “Simply by aging, our dopamine production decreases to the point that the effects from a mutation in this gene are not noticeable in older adults, but make a big difference in younger populations.”

The researchers noted that it is also important to pay attention to blood cholesterol levels. Cholesterol is directly related to the ability to produce dopamine. High low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is an established risk factor for Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Willette said. Their study shows that carriers of the mutated GCH1 gene had higher cholesterol than noncarriers, regardless of age.

Suggested Reading

Webb J, Willette AA. Aging modifies the effect of GCH1 RS11158026 on DAT uptake and Parkinson’s disease clinical severity. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;50:39-46.

Why Do Seizures Sometimes Continue After Surgery?

Roughly one out of every two patients with drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy will not become completely seizure-free after temporal lobe surgery. The reasons for this remain unclear and are most likely due to multiple factors. Preoperative automated fiber quantification (AFQ), however, may predict postoperative seizure outcome in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, according to a study published online ahead of print November 15, 2016, in Brain.

“We have identified three important factors that contribute to persistent postoperative seizures: diffusion abnormalities of the ipsilateral dorsal fornix outside the future margins of resection, diffusion abnormalities of the contralateral parahippocampal white matter bundle, and insufficient resection of the uncinate fasciculus,” said lead author Simon S. Keller, MSc, PhD, and colleagues. Dr. Keller is a Lecturer in Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology at the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom. “These results may have the potential to be developed into imaging prognostic markers of postoperative outcome and provide new insights for why some patients with temporal lobe epilepsy continue to experience postoperative seizures.”

Sensitive Imaging Technology

MRI techniques such as quantitative volumetric imaging have provided limited insight into what causes recurrent seizures after temporal lobe surgery. AFQ is a diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) tractography technique that permits a comprehensive analysis of tissue characteristics along the length of white matter tract bundles. This technique may allow for a more sensitive measure of neuroanatomic white matter alterations in patients with neurologic disorders than whole-tract approaches.

Dr. Keller and colleagues conducted a comprehensive DTI study to evaluate the local tissue physical characteristics of preoperative temporal lobe white matter tracts by applying DTI and AFQ in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy who underwent surgical treatment and postoperative follow-up. The primary goal of their research was to identify preoperative diffusion markers of postoperative seizure outcome. Their secondary goal was to determine whether the extent of resection of the temporal lobe tract bundles was associated with seizure outcome.

Forty-three patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy associated with hippocampal sclerosis and 44 healthy controls were included in the study. Patients underwent preoperative imaging, amygdalohippocampectomy, and postoperative assessment using the International League Against Epilepsy seizure outcome scale. The fimbria-fornix, parahippocampal, white matter bundle, and uncinate fasciculus were reconstructed from preoperative imaging. In addition, scalar diffusion metrics were calculated along the length of each tract.

Results revealed that 51.2% of patients had a completely seizure-free outcome, and 48.8% of patients had persistent postoperative seizures. More men were rendered seizure-free, relative to women. Compared to controls, both patient groups showed strong and significant diffusion abnormalities along the length of the uncinate bilaterally, the ipsilateral parahippocampal white matter bundle, and the ipsilateral fimbria-fornix in regions located within the medial temporal lobe.

However, only patients with persistent postoperative seizures showed evidence of significant pathology of tract sections located in the ipsilateral dorsal fornix and in the contralateral parahippocampal white matter bundle. Using receiver operating characteristic curves, diffusion characteristics of these regions could project individual patient outcomes with 84% sensitivity and 89% specificity.

Pathologic changes in the dorsal fornix were observed beyond the margins of resection. In addition, contralateral parahippocampal changes may suggest a bitemporal disorder in some patients. Diffusion characteristics of the ipsilateral uncinate could potentially classify patients from controls with a sensitivity of 98%.

By coregistering the preoperative fiber maps to postoperative surgical lacuna maps, Dr. Keller and colleagues observed that the extent of the surgical uncinate resection was significantly greater in patients who were rendered seizure-free, suggesting that a smaller surgical resection of the uncinate may represent insufficient disconnection of an anterior temporal epileptogenic network.

“An important future step will be to perform a pragmatic prospective study of consecutive patients with consideration of these new findings,” said Dr. Keller and colleagues.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Keller SS, Glenn RG, Weber B, et al. Preoperative automated fibre quantification predicts postoperative seizure outcome in temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2016 Nov 15 [Epub ahead of print].

Roughly one out of every two patients with drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy will not become completely seizure-free after temporal lobe surgery. The reasons for this remain unclear and are most likely due to multiple factors. Preoperative automated fiber quantification (AFQ), however, may predict postoperative seizure outcome in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, according to a study published online ahead of print November 15, 2016, in Brain.

“We have identified three important factors that contribute to persistent postoperative seizures: diffusion abnormalities of the ipsilateral dorsal fornix outside the future margins of resection, diffusion abnormalities of the contralateral parahippocampal white matter bundle, and insufficient resection of the uncinate fasciculus,” said lead author Simon S. Keller, MSc, PhD, and colleagues. Dr. Keller is a Lecturer in Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology at the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom. “These results may have the potential to be developed into imaging prognostic markers of postoperative outcome and provide new insights for why some patients with temporal lobe epilepsy continue to experience postoperative seizures.”

Sensitive Imaging Technology

MRI techniques such as quantitative volumetric imaging have provided limited insight into what causes recurrent seizures after temporal lobe surgery. AFQ is a diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) tractography technique that permits a comprehensive analysis of tissue characteristics along the length of white matter tract bundles. This technique may allow for a more sensitive measure of neuroanatomic white matter alterations in patients with neurologic disorders than whole-tract approaches.

Dr. Keller and colleagues conducted a comprehensive DTI study to evaluate the local tissue physical characteristics of preoperative temporal lobe white matter tracts by applying DTI and AFQ in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy who underwent surgical treatment and postoperative follow-up. The primary goal of their research was to identify preoperative diffusion markers of postoperative seizure outcome. Their secondary goal was to determine whether the extent of resection of the temporal lobe tract bundles was associated with seizure outcome.

Forty-three patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy associated with hippocampal sclerosis and 44 healthy controls were included in the study. Patients underwent preoperative imaging, amygdalohippocampectomy, and postoperative assessment using the International League Against Epilepsy seizure outcome scale. The fimbria-fornix, parahippocampal, white matter bundle, and uncinate fasciculus were reconstructed from preoperative imaging. In addition, scalar diffusion metrics were calculated along the length of each tract.

Results revealed that 51.2% of patients had a completely seizure-free outcome, and 48.8% of patients had persistent postoperative seizures. More men were rendered seizure-free, relative to women. Compared to controls, both patient groups showed strong and significant diffusion abnormalities along the length of the uncinate bilaterally, the ipsilateral parahippocampal white matter bundle, and the ipsilateral fimbria-fornix in regions located within the medial temporal lobe.