User login

Actinomycetoma: An Update on Diagnosis and Treatment

Mycetoma is a subcutaneous disease that can be caused by aerobic bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma). Diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations, including swelling and deformity of affected areas, as well as the presence of granulation tissue, scars, abscesses, sinus tracts, and a purulent exudate that contains the microorganisms.

The worldwide proportion of mycetomas is 60% actinomycetomas and 40% eumycetomas.1 The disease is endemic in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions, predominating between latitudes 30°N and 15°S. Most cases occur in Africa, especially Sudan, Mauritania, and Senegal; India; Yemen; and Pakistan. In the Americas, the countries with the most reported cases are Mexico and Venezuela.1

Although mycetoma is rare in developed countries, migration of patients from endemic areas makes knowledge of this condition crucial for dermatologists worldwide. We present a review of the current concepts in the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of actinomycetoma.

Epidemiology

Actinomycetoma is more common in Latin America, with Mexico having the highest incidence. At last count, there were 2631 cases reported in Mexico.2 The majority of cases of mycetoma in Mexico are actinomycetoma (98%), including Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). Eumycetoma is rare in Mexico, constituting only 2% of cases.2 Worldwide, men are affected more commonly than women, which is thought to be related to a higher occupational risk during agricultural labor.

Clinical Features

Mycetoma can affect the skin, subcutaneous tissue, bones, and occasionally the internal organs. It is characterized by swelling, deformation of the affected area, and fistulae that drain serosanguineous or purulent exudates.

In Mexico, 60% of cases of mycetoma affect the lower extremities; the feet are the most commonly affected area, followed by the trunk (back and chest), arms, forearms, legs, knees, and thighs.1 Other sites include the hands, shoulders, and abdominal wall. The head and neck area are seldom affected.3 Mycetoma lesions grow and disseminate locally. Bone lesions are possible depending on the osteophilic affinity of the etiological agent and on the interactions between the fungus and the host’s immune system. In severe advanced cases of mycetoma, the lesions may involve tendons and nerves. Dissemination via blood or lymphatics is extremely rare.4

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of actinomycetoma is suspected based on clinical features and confirmed by direct examination of exudates with Lugol iodine or saline solution. On direct microscopy, actinomycetes are recognized by the production of filaments with a width of 0.5 to 1 μm. On hematoxylin and eosin stain, the small grains of Nocardia appear eosinophilic with a blue center and pink filaments. On Gram stain, actinomycetoma grains show positive branching filaments. Culture of grains recovered from aspirated material or biopsy specimens provides specific etiologic diagnosis. Cultures should be held for at least 4 weeks. Additionally, there are some enzymatic, molecular, and serologic tests available for diagnosis.5-7 Serologic diagnosis is available in a few centers in Mexico and can be helpful in some cases for diagnosis or follow-up during treatment. Antibodies can be determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Western blot analysis, immunodiffusion, or counterimmunoelectrophoresis.8

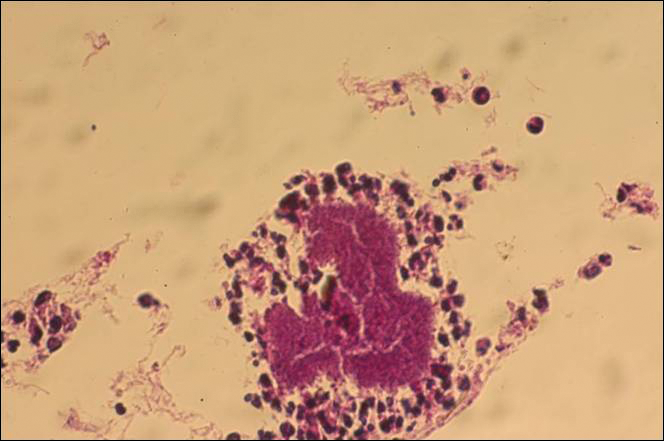

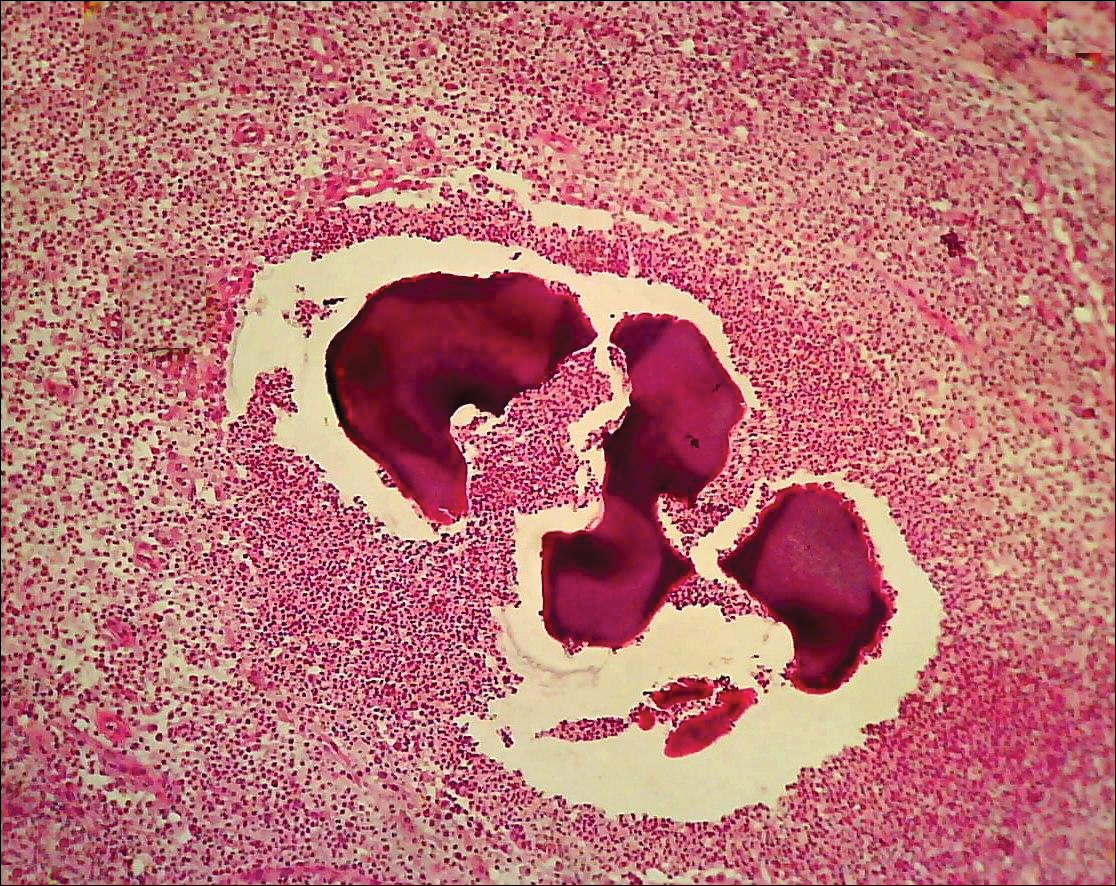

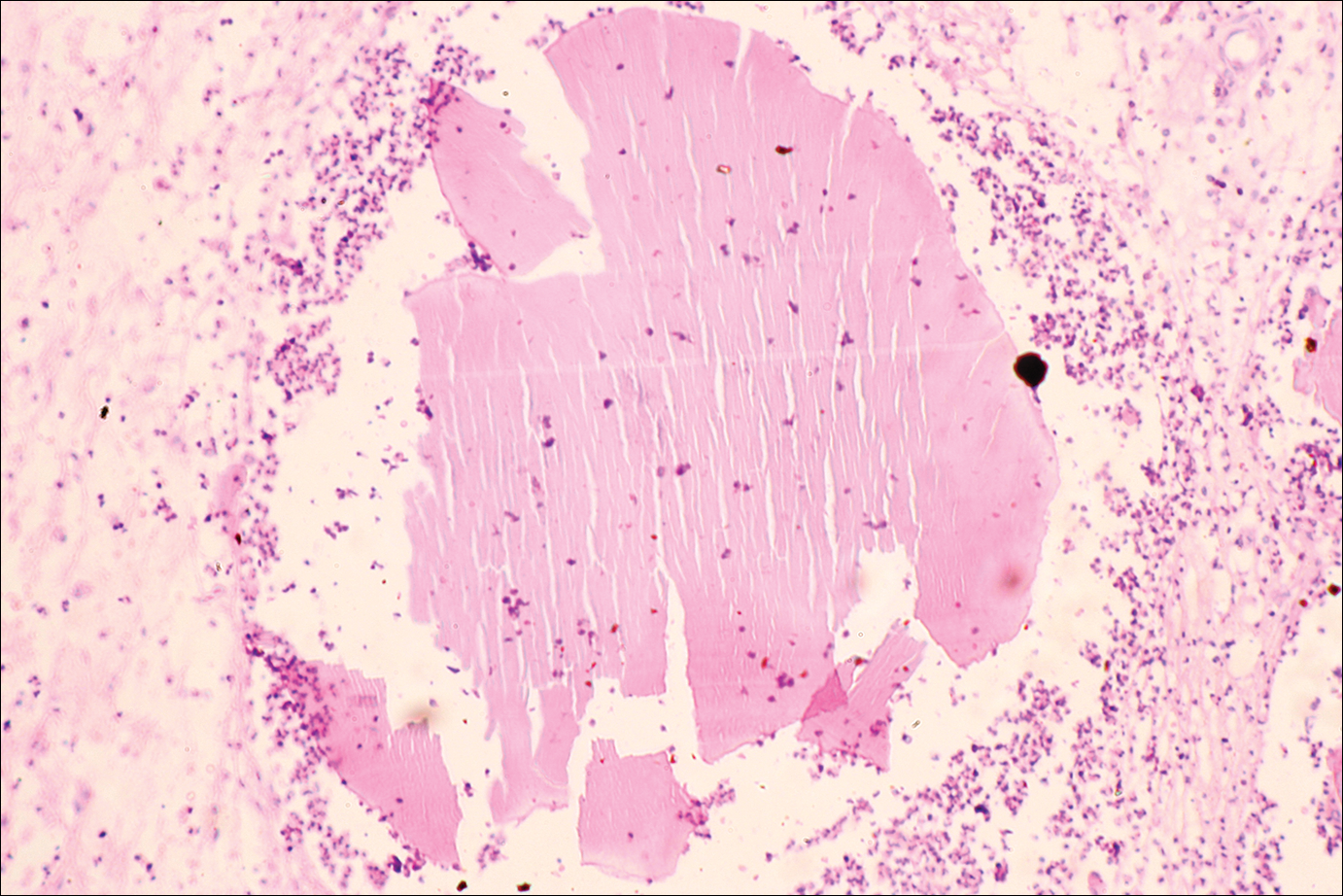

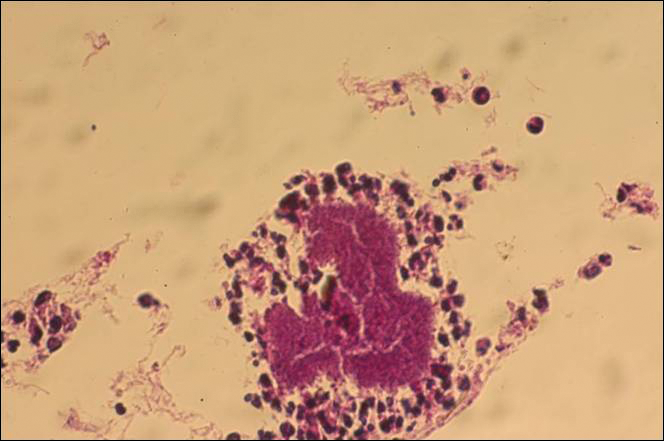

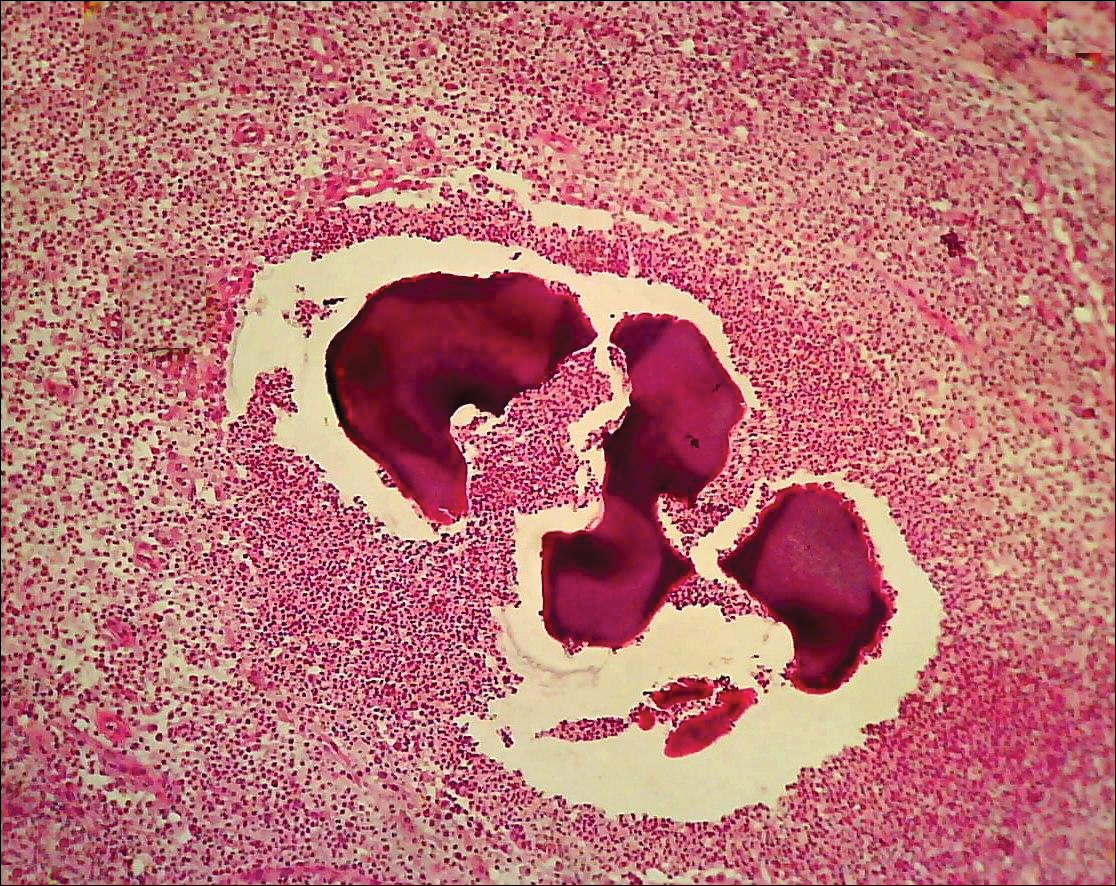

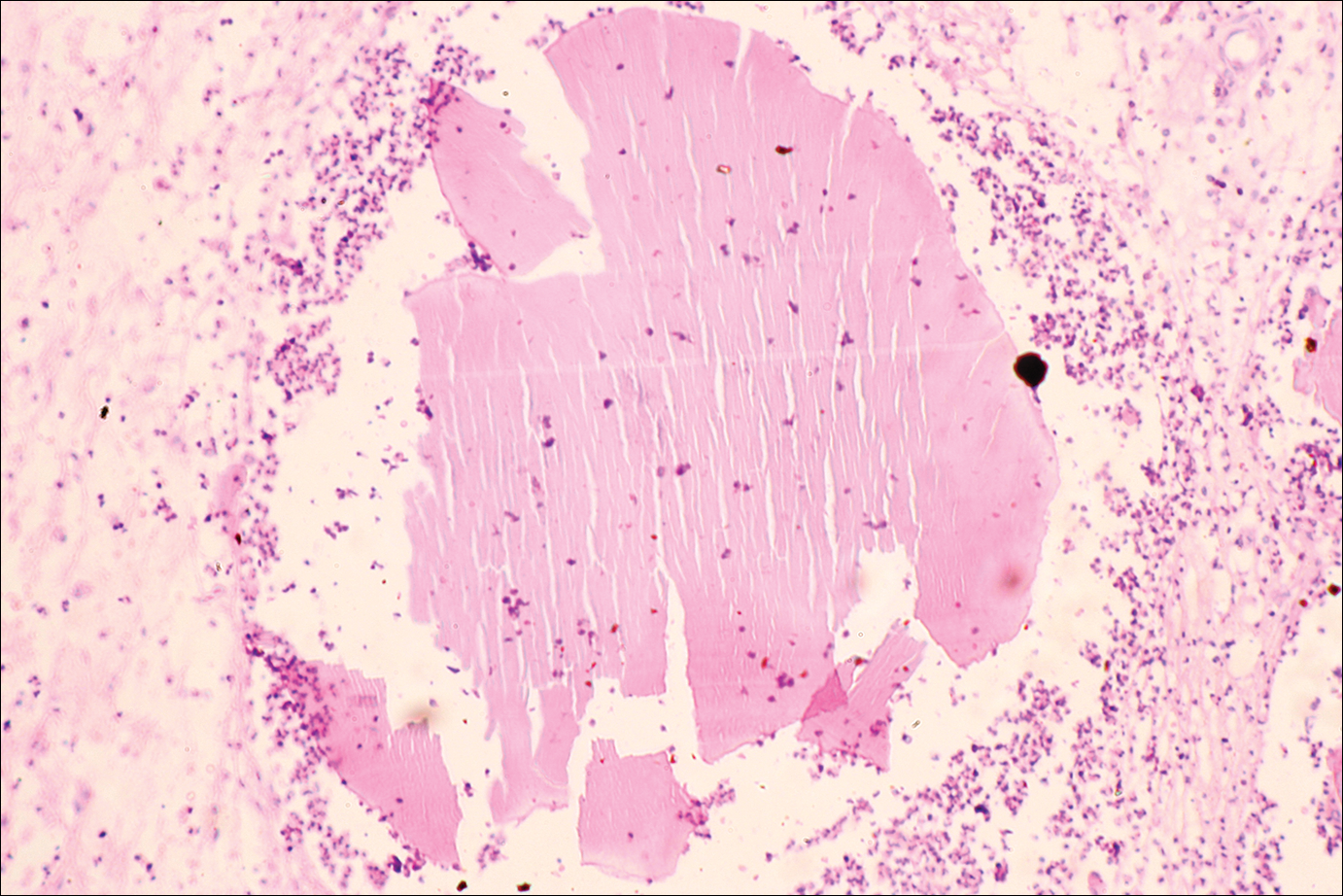

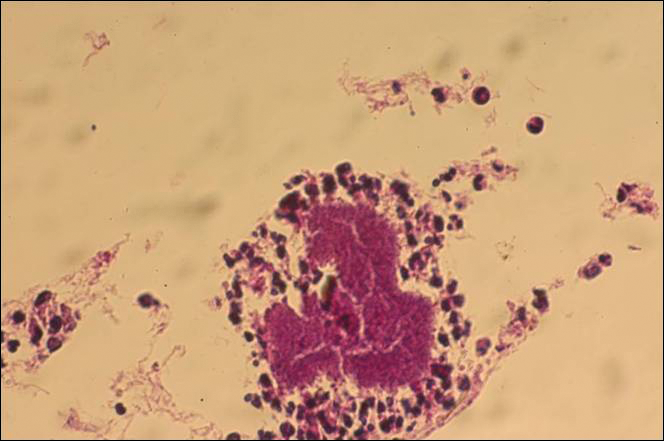

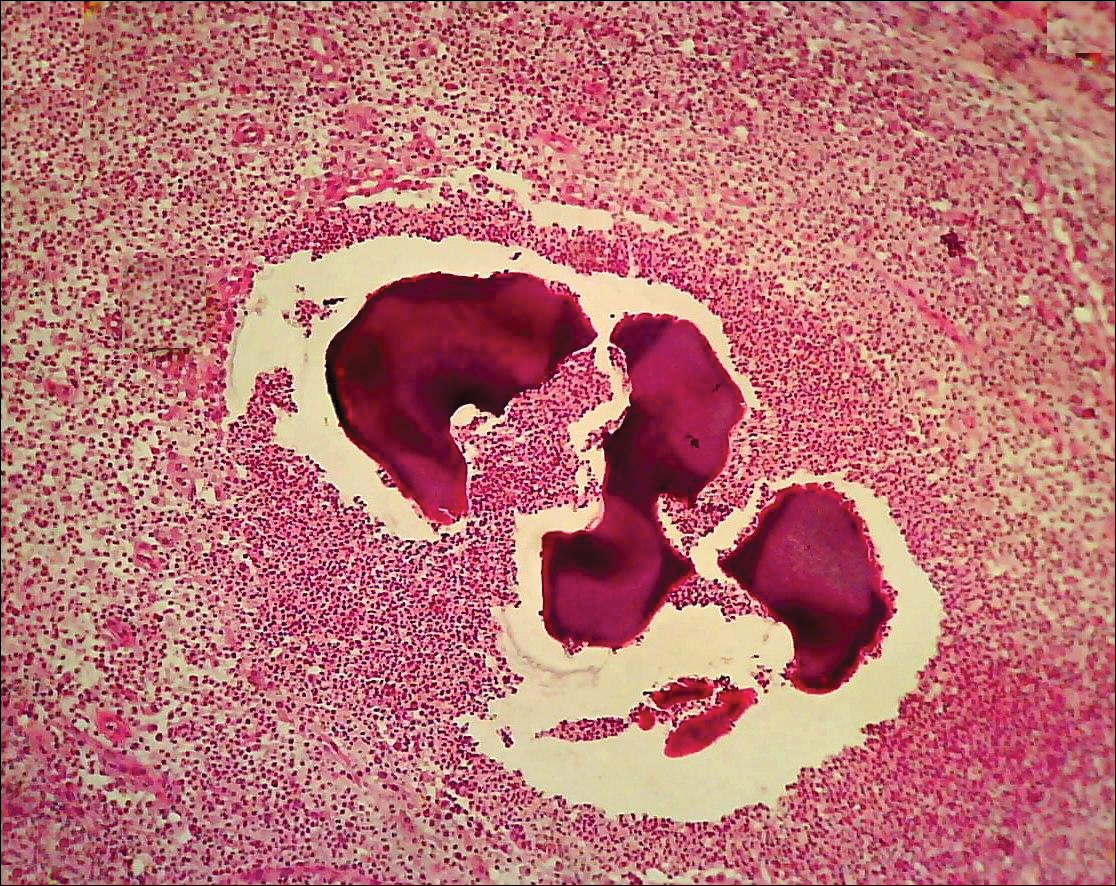

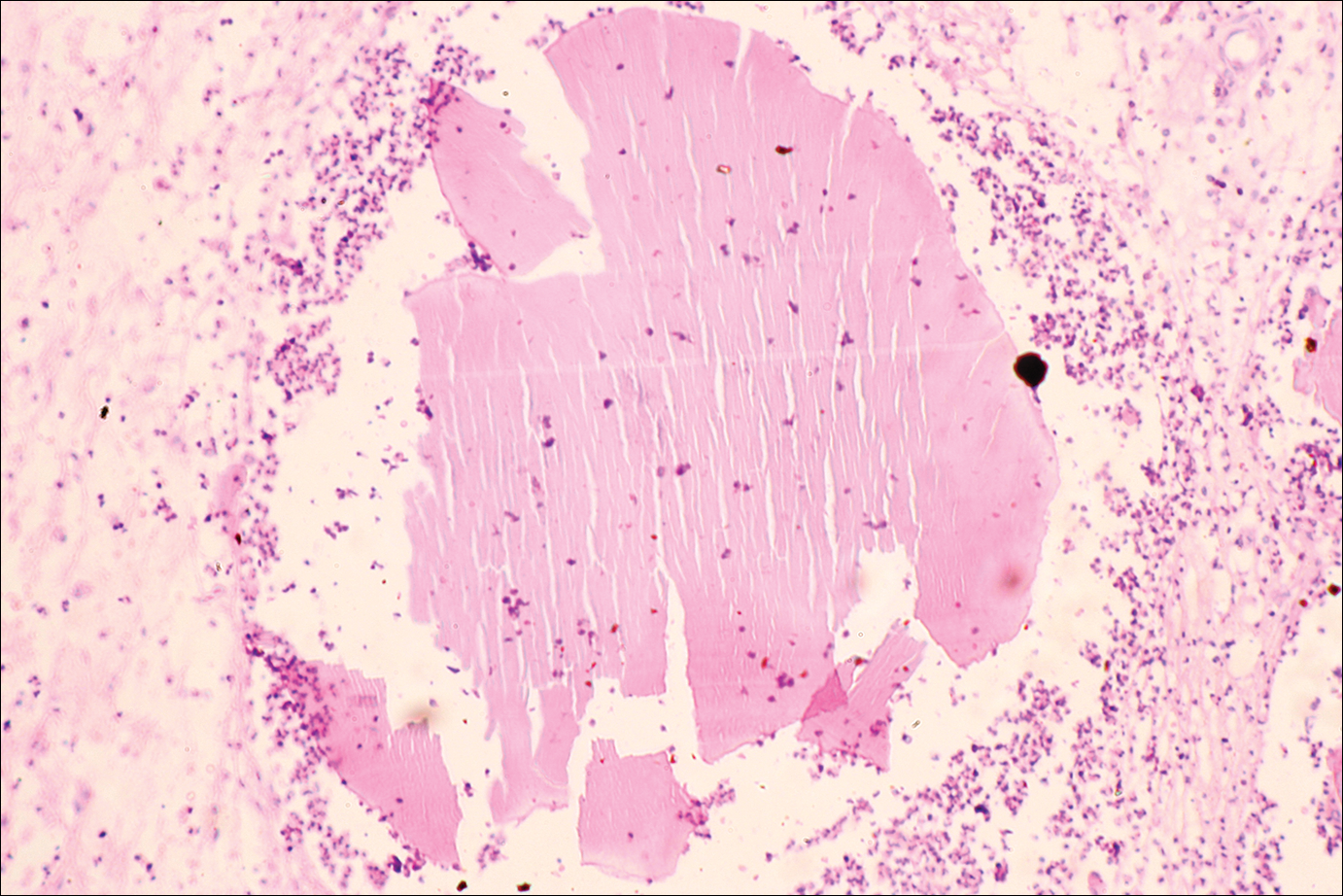

The causative agents of actinomycetoma can be isolated in Sabouraud dextrose agar. Deep wedge biopsies (or puncture aspiration) are useful in observing the diagnostic grains, which can be identified adequately with Gram stain. Grains usually are surrounded and/or infiltrated by neutrophils. The size, form, and color of grains can identify the causative agent.1 The granules of Nocardia are small (80–130 mm) and reniform or wormlike, with club structures in their periphery (Figure 1). Actinomadura madurae is characterized by large, white-yellow granules that can be seen with the naked eye (1–3 mm). On microscopic examination with hematoxylin and eosin stain, these grains are purple and exhibit peripheral pink pseudofilaments (Figure 2).2 The grains of Actinomadura pelletieri are large (1–3 mm) and red or violaceous. They fragment or break easily, giving the appearance of a broken dish (Figure 3). Streptomyces somaliensis forms round grains approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter. These grains stain poorly and are extremely hard. Cutting the grains during processing results in striation, giving them the appearance of a potato chip (Figure 4).2

Treatment of Actinomycetoma

Precise identification of the etiologic agent is essential to provide effective treatment of actinomycetoma. Without treatment, or in resistant cases, progressive osseous and visceral involvement is inevitable.9 Actinomycetoma without osseous involvement usually responds well to medical treatment.

The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma involving Nocardia brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years.10 Other treatments have included the following: (1) amikacin 15 mg/kg or 500 mg intramuscularly twice daily for 3 weeks plus dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily plus TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years (amikacin, however, is expensive and potentially toxic [nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity] and therefore is used only in resistant cases); (2) dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily or TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years plus intramuscular kanamycin 15 mg/kg once daily for 2 weeks at the beginning of treatment, alternating with rest periods to reduce the risk for nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity10; (3) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus phosphomycin 500 mg once daily; (4) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month, then the same dose every other day for 1 to 2 months monitoring for ototoxicity; and (5) TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years or rifampicin (15–20 mg/kg/d) plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month at the beginning of treatment, then the same dose every other day for 2 to 3 months until a total dose of 60 g is administered, monitoring for ototoxicity.11 Audiometric tests and creatinine levels must be performed every 5 weeks during the treatment to monitor toxicity.10

The best results for infections with A pelletieri, A madurae, and S somaliensis have been with streptomycin (1 g once daily in adults; 20 mg/kg once daily in children) until a total dose of 50 g is reached in combination with TMP-SMX or dapsone12 (Figure 5). Alternatives for A madurae infections include streptomycin plus oral clofazimine (100 mg once daily), oral rifampicin (300 mg twice daily), oral tetracycline (1 g once daily), oral isoniazid (300–600 mg once daily), or oral minocycline (100 mg twice daily; also effective for A pelletieri).

More recently, other drugs have been used such as carbapenems (eg, imipenem, meropenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases. Patients should be hospitalized to receive intravenous therapy with imipenem.2 Carbapenems are effective against gram-positive and gram-negative as well as Nocardia species.13,14 Mycetoma that is resistant, severe, or has visceral involvement can be treated with a combination of amikacin and imipenem.15,16 Meropenem is a similar drug that is available as an oral formulation. Both imipenem and meropenem are recommended in cases with bone involvement.17,18 Alternatives for resistant cases include amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 500/125 mg orally 3 times daily for 3 to 6 months or intravenous cefotaxime 1 g every 8 hours plus intramuscular amikacin 500 mg twice daily plus oral levamisole 300 mg once weekly for 4 weeks.19-23

For resistant cases associated with Nocardia species, clindamycin plus quinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, garenoxacin) at a dose of 25 mg/kg once daily for at least 3 months has been suggested in in vivo studies.23

Overall, the cure rate for actinomycetoma treated with any of the prior therapies ranges from 60% to 90%. Treatment must be modified or stopped if there is clinical or laboratory evidence of drug toxicity.13,24 Surgical treatment of actinomycetoma is contraindicated, as it may cause hematogenous dissemination.

Prognosis

Actinomycetomas of a few months’ duration and without bone involvement respond well to therapy. If no therapy is provided or if there is resistance, the functional and cosmetic prognosis is poor, mainly for the feet. There is a risk for spine involvement with mycetoma on the back and posterior head. Thoracic lesions may penetrate into the lungs. The muscular fascia impedes the penetration of abdominal lesions, but the inguinal canals can offer a path for intra-abdominal dissemination.4 Advanced cases lead to a poor general condition of patients, difficulty in using affected extremities, and in extreme cases even death.

The criteria used to guide the discontinuation of initial therapy for any mycetoma include a decrease in the volume of the lesion, closure of fistulae, 3 consecutive negative monthly cultures, imaging studies showing bone regeneration, lack of echoes and cavities on echography, and absence of grains on examination of fine-needle aspirates.11 After the initial treatment protocol is finished, most experts recommend continuing treatment with dapsone 100 to 300 mg once daily for several years to prevent recurrence.12

Prevention

Mycetoma is a disease associated with poverty. It could be prevented by improving living conditions and by regular use of shoes in rural populations.2

Conclusion

Mycetoma is a chronic infection that develops after traumatic inoculation of the skin with either true fungi or aerobic actinomycetes. The resultant infections are known as eumycetoma or actinomycetoma, respectively. The etiologic agents can be found in the so-called grains. Black grains suggest a fungal infection, minute white grains suggest Nocardia, and red grains are due to A pelletieri. Larger white grains or yellow-white grains may be fungal or actinomycotic in origin.

Specific diagnosis requires direct examination, culture, and biopsy. The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma by N brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years. Other effective treatments include aminoglycosides (eg, amikacine, streptomycin) and quinolones. More recently, some other agents have been used such as carbapenems and natural products of Streptomyces cattleya (imipenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, et al. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:372-381.

- Arenas R. Micología Medica Ilustrada. 4th ed. Mexico City, Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2011:125-146.

- McGinnis MR. Mycetoma. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:97-104.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: Clinico-pathological Monograph. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2006:20-23, 81-82.

- Estrada-Chavez GE, Vega-Memije ME, Arenas R, et al. Eumycotic mycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis successfully treated with antifungals, surgery, and topical negative pressure therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:401-403.

- Chávez G, Arenas R, Pérez-Polito A, et al. Eumycetic mycetoma due to Madurella mycetomatis. report of six cases. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1998;15:90-93.

- Vasquez del Mercado E, Arenas R, Moreno G. Sequelae and long-term consequences of systemic and subcutaneous mycoses. In: Fratamico PM, Smith JL, Brogden KA, eds. Sequelae and Long-term Consequences of Infectious Diseases. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2009:415-420.

- Mancini N, Ossi CM, Perotti M, et al. Molecular mycological diagnosis and correct antimycotic treatments. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3584-3585.

- Arenas R, Lavalle P. Micetoma (madura foot). In: Arenas R, Estrada R, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2001:51-61.

- Welsh O, Sauceda E, González J, et al. Amikacin alone and in combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of actinomycotic mycetoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:443-448.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: clinico-pathological monograph. In: Fahal AH. Evidence Based Guidelines for the Management of Mycetoma Patients. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2002:5-15.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodríguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Valle ACF, Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L. Subcutaneous mycoses—mycetoma. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2006:197-200.

- Fuentes A, Arenas R, Reyes M, et al. Actinomicetoma por Nocardia sp. Informe de cinco casos tratados con imipenem solo o combinado con amikacina. Gac Med Mex. 2006;142:247-252.

- Gombert ME, Aulicino TM, DuBouchet L, et al. Therapy of experimental cerebral nocardiosis with imipenem, amikacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and minocylina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:270-273.

- Calandra GB, Ricci FM, Wang C, et al. Safety and tolerance comparison of imipenem-cilastatin to cephalotin and cefazolin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12:125-131.

- Ameen M, Arenas R, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Efficacy of imipenem therapy for Nocardia actinomycetomas refractory to sulfonamides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:239-246.

- Ameen M, Vargas F, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Successful treatment of Nocardia actinomycetoma with meropenem and amikacin combination therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:443-445.

- Ameen M, Arenas R. Emerging therapeutic regimes for the management of mycetomas. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2077-2085.

- Vera-Cabrera L, Daw-Garza A, Said-Fernández S, et al. Therapeutic effect of a novel oxazolidinone, DA-7867 in BALB/c mice infected with Nocardia brasiliensis. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e289.

- Gómez A, Saúl A, Bonifaz A. Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in the treatment of actinomicetoma. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:218-220.

- Méndez-Tovar L, Serrano-Jaen L, Almeida-Arvizu VM. Cefotaxima mas amikacina asociadas a inmunomodulación en el tratamiento de actinomicetoma resistente a tratamiento convencional. Gac Med Mex. 1999;135:517-521.

- Chacon-Moreno BE, Welsh O, Cavazos-Rocha N, et al. Efficacy of ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin against Nocardia brasiliensis in vitro in an experimental model of actinomycetoma in BALB/c mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:295-297.

- Welsh O. Treatment of actinomycetoma. Arch Med Res. 1993;24:413-415.

Mycetoma is a subcutaneous disease that can be caused by aerobic bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma). Diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations, including swelling and deformity of affected areas, as well as the presence of granulation tissue, scars, abscesses, sinus tracts, and a purulent exudate that contains the microorganisms.

The worldwide proportion of mycetomas is 60% actinomycetomas and 40% eumycetomas.1 The disease is endemic in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions, predominating between latitudes 30°N and 15°S. Most cases occur in Africa, especially Sudan, Mauritania, and Senegal; India; Yemen; and Pakistan. In the Americas, the countries with the most reported cases are Mexico and Venezuela.1

Although mycetoma is rare in developed countries, migration of patients from endemic areas makes knowledge of this condition crucial for dermatologists worldwide. We present a review of the current concepts in the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of actinomycetoma.

Epidemiology

Actinomycetoma is more common in Latin America, with Mexico having the highest incidence. At last count, there were 2631 cases reported in Mexico.2 The majority of cases of mycetoma in Mexico are actinomycetoma (98%), including Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). Eumycetoma is rare in Mexico, constituting only 2% of cases.2 Worldwide, men are affected more commonly than women, which is thought to be related to a higher occupational risk during agricultural labor.

Clinical Features

Mycetoma can affect the skin, subcutaneous tissue, bones, and occasionally the internal organs. It is characterized by swelling, deformation of the affected area, and fistulae that drain serosanguineous or purulent exudates.

In Mexico, 60% of cases of mycetoma affect the lower extremities; the feet are the most commonly affected area, followed by the trunk (back and chest), arms, forearms, legs, knees, and thighs.1 Other sites include the hands, shoulders, and abdominal wall. The head and neck area are seldom affected.3 Mycetoma lesions grow and disseminate locally. Bone lesions are possible depending on the osteophilic affinity of the etiological agent and on the interactions between the fungus and the host’s immune system. In severe advanced cases of mycetoma, the lesions may involve tendons and nerves. Dissemination via blood or lymphatics is extremely rare.4

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of actinomycetoma is suspected based on clinical features and confirmed by direct examination of exudates with Lugol iodine or saline solution. On direct microscopy, actinomycetes are recognized by the production of filaments with a width of 0.5 to 1 μm. On hematoxylin and eosin stain, the small grains of Nocardia appear eosinophilic with a blue center and pink filaments. On Gram stain, actinomycetoma grains show positive branching filaments. Culture of grains recovered from aspirated material or biopsy specimens provides specific etiologic diagnosis. Cultures should be held for at least 4 weeks. Additionally, there are some enzymatic, molecular, and serologic tests available for diagnosis.5-7 Serologic diagnosis is available in a few centers in Mexico and can be helpful in some cases for diagnosis or follow-up during treatment. Antibodies can be determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Western blot analysis, immunodiffusion, or counterimmunoelectrophoresis.8

The causative agents of actinomycetoma can be isolated in Sabouraud dextrose agar. Deep wedge biopsies (or puncture aspiration) are useful in observing the diagnostic grains, which can be identified adequately with Gram stain. Grains usually are surrounded and/or infiltrated by neutrophils. The size, form, and color of grains can identify the causative agent.1 The granules of Nocardia are small (80–130 mm) and reniform or wormlike, with club structures in their periphery (Figure 1). Actinomadura madurae is characterized by large, white-yellow granules that can be seen with the naked eye (1–3 mm). On microscopic examination with hematoxylin and eosin stain, these grains are purple and exhibit peripheral pink pseudofilaments (Figure 2).2 The grains of Actinomadura pelletieri are large (1–3 mm) and red or violaceous. They fragment or break easily, giving the appearance of a broken dish (Figure 3). Streptomyces somaliensis forms round grains approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter. These grains stain poorly and are extremely hard. Cutting the grains during processing results in striation, giving them the appearance of a potato chip (Figure 4).2

Treatment of Actinomycetoma

Precise identification of the etiologic agent is essential to provide effective treatment of actinomycetoma. Without treatment, or in resistant cases, progressive osseous and visceral involvement is inevitable.9 Actinomycetoma without osseous involvement usually responds well to medical treatment.

The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma involving Nocardia brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years.10 Other treatments have included the following: (1) amikacin 15 mg/kg or 500 mg intramuscularly twice daily for 3 weeks plus dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily plus TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years (amikacin, however, is expensive and potentially toxic [nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity] and therefore is used only in resistant cases); (2) dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily or TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years plus intramuscular kanamycin 15 mg/kg once daily for 2 weeks at the beginning of treatment, alternating with rest periods to reduce the risk for nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity10; (3) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus phosphomycin 500 mg once daily; (4) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month, then the same dose every other day for 1 to 2 months monitoring for ototoxicity; and (5) TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years or rifampicin (15–20 mg/kg/d) plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month at the beginning of treatment, then the same dose every other day for 2 to 3 months until a total dose of 60 g is administered, monitoring for ototoxicity.11 Audiometric tests and creatinine levels must be performed every 5 weeks during the treatment to monitor toxicity.10

The best results for infections with A pelletieri, A madurae, and S somaliensis have been with streptomycin (1 g once daily in adults; 20 mg/kg once daily in children) until a total dose of 50 g is reached in combination with TMP-SMX or dapsone12 (Figure 5). Alternatives for A madurae infections include streptomycin plus oral clofazimine (100 mg once daily), oral rifampicin (300 mg twice daily), oral tetracycline (1 g once daily), oral isoniazid (300–600 mg once daily), or oral minocycline (100 mg twice daily; also effective for A pelletieri).

More recently, other drugs have been used such as carbapenems (eg, imipenem, meropenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases. Patients should be hospitalized to receive intravenous therapy with imipenem.2 Carbapenems are effective against gram-positive and gram-negative as well as Nocardia species.13,14 Mycetoma that is resistant, severe, or has visceral involvement can be treated with a combination of amikacin and imipenem.15,16 Meropenem is a similar drug that is available as an oral formulation. Both imipenem and meropenem are recommended in cases with bone involvement.17,18 Alternatives for resistant cases include amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 500/125 mg orally 3 times daily for 3 to 6 months or intravenous cefotaxime 1 g every 8 hours plus intramuscular amikacin 500 mg twice daily plus oral levamisole 300 mg once weekly for 4 weeks.19-23

For resistant cases associated with Nocardia species, clindamycin plus quinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, garenoxacin) at a dose of 25 mg/kg once daily for at least 3 months has been suggested in in vivo studies.23

Overall, the cure rate for actinomycetoma treated with any of the prior therapies ranges from 60% to 90%. Treatment must be modified or stopped if there is clinical or laboratory evidence of drug toxicity.13,24 Surgical treatment of actinomycetoma is contraindicated, as it may cause hematogenous dissemination.

Prognosis

Actinomycetomas of a few months’ duration and without bone involvement respond well to therapy. If no therapy is provided or if there is resistance, the functional and cosmetic prognosis is poor, mainly for the feet. There is a risk for spine involvement with mycetoma on the back and posterior head. Thoracic lesions may penetrate into the lungs. The muscular fascia impedes the penetration of abdominal lesions, but the inguinal canals can offer a path for intra-abdominal dissemination.4 Advanced cases lead to a poor general condition of patients, difficulty in using affected extremities, and in extreme cases even death.

The criteria used to guide the discontinuation of initial therapy for any mycetoma include a decrease in the volume of the lesion, closure of fistulae, 3 consecutive negative monthly cultures, imaging studies showing bone regeneration, lack of echoes and cavities on echography, and absence of grains on examination of fine-needle aspirates.11 After the initial treatment protocol is finished, most experts recommend continuing treatment with dapsone 100 to 300 mg once daily for several years to prevent recurrence.12

Prevention

Mycetoma is a disease associated with poverty. It could be prevented by improving living conditions and by regular use of shoes in rural populations.2

Conclusion

Mycetoma is a chronic infection that develops after traumatic inoculation of the skin with either true fungi or aerobic actinomycetes. The resultant infections are known as eumycetoma or actinomycetoma, respectively. The etiologic agents can be found in the so-called grains. Black grains suggest a fungal infection, minute white grains suggest Nocardia, and red grains are due to A pelletieri. Larger white grains or yellow-white grains may be fungal or actinomycotic in origin.

Specific diagnosis requires direct examination, culture, and biopsy. The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma by N brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years. Other effective treatments include aminoglycosides (eg, amikacine, streptomycin) and quinolones. More recently, some other agents have been used such as carbapenems and natural products of Streptomyces cattleya (imipenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases.

Mycetoma is a subcutaneous disease that can be caused by aerobic bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma). Diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations, including swelling and deformity of affected areas, as well as the presence of granulation tissue, scars, abscesses, sinus tracts, and a purulent exudate that contains the microorganisms.

The worldwide proportion of mycetomas is 60% actinomycetomas and 40% eumycetomas.1 The disease is endemic in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions, predominating between latitudes 30°N and 15°S. Most cases occur in Africa, especially Sudan, Mauritania, and Senegal; India; Yemen; and Pakistan. In the Americas, the countries with the most reported cases are Mexico and Venezuela.1

Although mycetoma is rare in developed countries, migration of patients from endemic areas makes knowledge of this condition crucial for dermatologists worldwide. We present a review of the current concepts in the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of actinomycetoma.

Epidemiology

Actinomycetoma is more common in Latin America, with Mexico having the highest incidence. At last count, there were 2631 cases reported in Mexico.2 The majority of cases of mycetoma in Mexico are actinomycetoma (98%), including Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). Eumycetoma is rare in Mexico, constituting only 2% of cases.2 Worldwide, men are affected more commonly than women, which is thought to be related to a higher occupational risk during agricultural labor.

Clinical Features

Mycetoma can affect the skin, subcutaneous tissue, bones, and occasionally the internal organs. It is characterized by swelling, deformation of the affected area, and fistulae that drain serosanguineous or purulent exudates.

In Mexico, 60% of cases of mycetoma affect the lower extremities; the feet are the most commonly affected area, followed by the trunk (back and chest), arms, forearms, legs, knees, and thighs.1 Other sites include the hands, shoulders, and abdominal wall. The head and neck area are seldom affected.3 Mycetoma lesions grow and disseminate locally. Bone lesions are possible depending on the osteophilic affinity of the etiological agent and on the interactions between the fungus and the host’s immune system. In severe advanced cases of mycetoma, the lesions may involve tendons and nerves. Dissemination via blood or lymphatics is extremely rare.4

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of actinomycetoma is suspected based on clinical features and confirmed by direct examination of exudates with Lugol iodine or saline solution. On direct microscopy, actinomycetes are recognized by the production of filaments with a width of 0.5 to 1 μm. On hematoxylin and eosin stain, the small grains of Nocardia appear eosinophilic with a blue center and pink filaments. On Gram stain, actinomycetoma grains show positive branching filaments. Culture of grains recovered from aspirated material or biopsy specimens provides specific etiologic diagnosis. Cultures should be held for at least 4 weeks. Additionally, there are some enzymatic, molecular, and serologic tests available for diagnosis.5-7 Serologic diagnosis is available in a few centers in Mexico and can be helpful in some cases for diagnosis or follow-up during treatment. Antibodies can be determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Western blot analysis, immunodiffusion, or counterimmunoelectrophoresis.8

The causative agents of actinomycetoma can be isolated in Sabouraud dextrose agar. Deep wedge biopsies (or puncture aspiration) are useful in observing the diagnostic grains, which can be identified adequately with Gram stain. Grains usually are surrounded and/or infiltrated by neutrophils. The size, form, and color of grains can identify the causative agent.1 The granules of Nocardia are small (80–130 mm) and reniform or wormlike, with club structures in their periphery (Figure 1). Actinomadura madurae is characterized by large, white-yellow granules that can be seen with the naked eye (1–3 mm). On microscopic examination with hematoxylin and eosin stain, these grains are purple and exhibit peripheral pink pseudofilaments (Figure 2).2 The grains of Actinomadura pelletieri are large (1–3 mm) and red or violaceous. They fragment or break easily, giving the appearance of a broken dish (Figure 3). Streptomyces somaliensis forms round grains approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter. These grains stain poorly and are extremely hard. Cutting the grains during processing results in striation, giving them the appearance of a potato chip (Figure 4).2

Treatment of Actinomycetoma

Precise identification of the etiologic agent is essential to provide effective treatment of actinomycetoma. Without treatment, or in resistant cases, progressive osseous and visceral involvement is inevitable.9 Actinomycetoma without osseous involvement usually responds well to medical treatment.

The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma involving Nocardia brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years.10 Other treatments have included the following: (1) amikacin 15 mg/kg or 500 mg intramuscularly twice daily for 3 weeks plus dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily plus TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years (amikacin, however, is expensive and potentially toxic [nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity] and therefore is used only in resistant cases); (2) dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily or TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg daily for 2 to 3 years plus intramuscular kanamycin 15 mg/kg once daily for 2 weeks at the beginning of treatment, alternating with rest periods to reduce the risk for nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity10; (3) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus phosphomycin 500 mg once daily; (4) dapsone 1.5 mg/kg orally twice daily plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month, then the same dose every other day for 1 to 2 months monitoring for ototoxicity; and (5) TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years or rifampicin (15–20 mg/kg/d) plus streptomycin 1 g once daily (14 mg/kg/d) for 1 month at the beginning of treatment, then the same dose every other day for 2 to 3 months until a total dose of 60 g is administered, monitoring for ototoxicity.11 Audiometric tests and creatinine levels must be performed every 5 weeks during the treatment to monitor toxicity.10

The best results for infections with A pelletieri, A madurae, and S somaliensis have been with streptomycin (1 g once daily in adults; 20 mg/kg once daily in children) until a total dose of 50 g is reached in combination with TMP-SMX or dapsone12 (Figure 5). Alternatives for A madurae infections include streptomycin plus oral clofazimine (100 mg once daily), oral rifampicin (300 mg twice daily), oral tetracycline (1 g once daily), oral isoniazid (300–600 mg once daily), or oral minocycline (100 mg twice daily; also effective for A pelletieri).

More recently, other drugs have been used such as carbapenems (eg, imipenem, meropenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases. Patients should be hospitalized to receive intravenous therapy with imipenem.2 Carbapenems are effective against gram-positive and gram-negative as well as Nocardia species.13,14 Mycetoma that is resistant, severe, or has visceral involvement can be treated with a combination of amikacin and imipenem.15,16 Meropenem is a similar drug that is available as an oral formulation. Both imipenem and meropenem are recommended in cases with bone involvement.17,18 Alternatives for resistant cases include amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 500/125 mg orally 3 times daily for 3 to 6 months or intravenous cefotaxime 1 g every 8 hours plus intramuscular amikacin 500 mg twice daily plus oral levamisole 300 mg once weekly for 4 weeks.19-23

For resistant cases associated with Nocardia species, clindamycin plus quinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, garenoxacin) at a dose of 25 mg/kg once daily for at least 3 months has been suggested in in vivo studies.23

Overall, the cure rate for actinomycetoma treated with any of the prior therapies ranges from 60% to 90%. Treatment must be modified or stopped if there is clinical or laboratory evidence of drug toxicity.13,24 Surgical treatment of actinomycetoma is contraindicated, as it may cause hematogenous dissemination.

Prognosis

Actinomycetomas of a few months’ duration and without bone involvement respond well to therapy. If no therapy is provided or if there is resistance, the functional and cosmetic prognosis is poor, mainly for the feet. There is a risk for spine involvement with mycetoma on the back and posterior head. Thoracic lesions may penetrate into the lungs. The muscular fascia impedes the penetration of abdominal lesions, but the inguinal canals can offer a path for intra-abdominal dissemination.4 Advanced cases lead to a poor general condition of patients, difficulty in using affected extremities, and in extreme cases even death.

The criteria used to guide the discontinuation of initial therapy for any mycetoma include a decrease in the volume of the lesion, closure of fistulae, 3 consecutive negative monthly cultures, imaging studies showing bone regeneration, lack of echoes and cavities on echography, and absence of grains on examination of fine-needle aspirates.11 After the initial treatment protocol is finished, most experts recommend continuing treatment with dapsone 100 to 300 mg once daily for several years to prevent recurrence.12

Prevention

Mycetoma is a disease associated with poverty. It could be prevented by improving living conditions and by regular use of shoes in rural populations.2

Conclusion

Mycetoma is a chronic infection that develops after traumatic inoculation of the skin with either true fungi or aerobic actinomycetes. The resultant infections are known as eumycetoma or actinomycetoma, respectively. The etiologic agents can be found in the so-called grains. Black grains suggest a fungal infection, minute white grains suggest Nocardia, and red grains are due to A pelletieri. Larger white grains or yellow-white grains may be fungal or actinomycotic in origin.

Specific diagnosis requires direct examination, culture, and biopsy. The treatment of choice for actinomycetoma by N brasiliensis is a combination of dapsone 100 to 200 mg once daily and TMP-SMX 80/400 to 160/800 mg once daily for 2 to 3 years. Other effective treatments include aminoglycosides (eg, amikacine, streptomycin) and quinolones. More recently, some other agents have been used such as carbapenems and natural products of Streptomyces cattleya (imipenem), which have wide-spectrum efficacy and are resistant to β-lactamases.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, et al. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:372-381.

- Arenas R. Micología Medica Ilustrada. 4th ed. Mexico City, Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2011:125-146.

- McGinnis MR. Mycetoma. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:97-104.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: Clinico-pathological Monograph. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2006:20-23, 81-82.

- Estrada-Chavez GE, Vega-Memije ME, Arenas R, et al. Eumycotic mycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis successfully treated with antifungals, surgery, and topical negative pressure therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:401-403.

- Chávez G, Arenas R, Pérez-Polito A, et al. Eumycetic mycetoma due to Madurella mycetomatis. report of six cases. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1998;15:90-93.

- Vasquez del Mercado E, Arenas R, Moreno G. Sequelae and long-term consequences of systemic and subcutaneous mycoses. In: Fratamico PM, Smith JL, Brogden KA, eds. Sequelae and Long-term Consequences of Infectious Diseases. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2009:415-420.

- Mancini N, Ossi CM, Perotti M, et al. Molecular mycological diagnosis and correct antimycotic treatments. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3584-3585.

- Arenas R, Lavalle P. Micetoma (madura foot). In: Arenas R, Estrada R, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2001:51-61.

- Welsh O, Sauceda E, González J, et al. Amikacin alone and in combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of actinomycotic mycetoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:443-448.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: clinico-pathological monograph. In: Fahal AH. Evidence Based Guidelines for the Management of Mycetoma Patients. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2002:5-15.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodríguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Valle ACF, Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L. Subcutaneous mycoses—mycetoma. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2006:197-200.

- Fuentes A, Arenas R, Reyes M, et al. Actinomicetoma por Nocardia sp. Informe de cinco casos tratados con imipenem solo o combinado con amikacina. Gac Med Mex. 2006;142:247-252.

- Gombert ME, Aulicino TM, DuBouchet L, et al. Therapy of experimental cerebral nocardiosis with imipenem, amikacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and minocylina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:270-273.

- Calandra GB, Ricci FM, Wang C, et al. Safety and tolerance comparison of imipenem-cilastatin to cephalotin and cefazolin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12:125-131.

- Ameen M, Arenas R, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Efficacy of imipenem therapy for Nocardia actinomycetomas refractory to sulfonamides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:239-246.

- Ameen M, Vargas F, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Successful treatment of Nocardia actinomycetoma with meropenem and amikacin combination therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:443-445.

- Ameen M, Arenas R. Emerging therapeutic regimes for the management of mycetomas. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2077-2085.

- Vera-Cabrera L, Daw-Garza A, Said-Fernández S, et al. Therapeutic effect of a novel oxazolidinone, DA-7867 in BALB/c mice infected with Nocardia brasiliensis. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e289.

- Gómez A, Saúl A, Bonifaz A. Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in the treatment of actinomicetoma. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:218-220.

- Méndez-Tovar L, Serrano-Jaen L, Almeida-Arvizu VM. Cefotaxima mas amikacina asociadas a inmunomodulación en el tratamiento de actinomicetoma resistente a tratamiento convencional. Gac Med Mex. 1999;135:517-521.

- Chacon-Moreno BE, Welsh O, Cavazos-Rocha N, et al. Efficacy of ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin against Nocardia brasiliensis in vitro in an experimental model of actinomycetoma in BALB/c mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:295-297.

- Welsh O. Treatment of actinomycetoma. Arch Med Res. 1993;24:413-415.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Welsh E, et al. Actinomycetoma and advances in its treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:372-381.

- Arenas R. Micología Medica Ilustrada. 4th ed. Mexico City, Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2011:125-146.

- McGinnis MR. Mycetoma. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:97-104.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: Clinico-pathological Monograph. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2006:20-23, 81-82.

- Estrada-Chavez GE, Vega-Memije ME, Arenas R, et al. Eumycotic mycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis successfully treated with antifungals, surgery, and topical negative pressure therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:401-403.

- Chávez G, Arenas R, Pérez-Polito A, et al. Eumycetic mycetoma due to Madurella mycetomatis. report of six cases. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1998;15:90-93.

- Vasquez del Mercado E, Arenas R, Moreno G. Sequelae and long-term consequences of systemic and subcutaneous mycoses. In: Fratamico PM, Smith JL, Brogden KA, eds. Sequelae and Long-term Consequences of Infectious Diseases. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2009:415-420.

- Mancini N, Ossi CM, Perotti M, et al. Molecular mycological diagnosis and correct antimycotic treatments. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3584-3585.

- Arenas R, Lavalle P. Micetoma (madura foot). In: Arenas R, Estrada R, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2001:51-61.

- Welsh O, Sauceda E, González J, et al. Amikacin alone and in combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of actinomycotic mycetoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:443-448.

- Fahal AH. Mycetoma: clinico-pathological monograph. In: Fahal AH. Evidence Based Guidelines for the Management of Mycetoma Patients. Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum Press; 2002:5-15.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodríguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Valle ACF, Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L. Subcutaneous mycoses—mycetoma. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2006:197-200.

- Fuentes A, Arenas R, Reyes M, et al. Actinomicetoma por Nocardia sp. Informe de cinco casos tratados con imipenem solo o combinado con amikacina. Gac Med Mex. 2006;142:247-252.

- Gombert ME, Aulicino TM, DuBouchet L, et al. Therapy of experimental cerebral nocardiosis with imipenem, amikacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and minocylina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:270-273.

- Calandra GB, Ricci FM, Wang C, et al. Safety and tolerance comparison of imipenem-cilastatin to cephalotin and cefazolin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12:125-131.

- Ameen M, Arenas R, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Efficacy of imipenem therapy for Nocardia actinomycetomas refractory to sulfonamides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:239-246.

- Ameen M, Vargas F, Vasquez del Mercado E, et al. Successful treatment of Nocardia actinomycetoma with meropenem and amikacin combination therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:443-445.

- Ameen M, Arenas R. Emerging therapeutic regimes for the management of mycetomas. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2077-2085.

- Vera-Cabrera L, Daw-Garza A, Said-Fernández S, et al. Therapeutic effect of a novel oxazolidinone, DA-7867 in BALB/c mice infected with Nocardia brasiliensis. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e289.

- Gómez A, Saúl A, Bonifaz A. Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid in the treatment of actinomicetoma. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:218-220.

- Méndez-Tovar L, Serrano-Jaen L, Almeida-Arvizu VM. Cefotaxima mas amikacina asociadas a inmunomodulación en el tratamiento de actinomicetoma resistente a tratamiento convencional. Gac Med Mex. 1999;135:517-521.

- Chacon-Moreno BE, Welsh O, Cavazos-Rocha N, et al. Efficacy of ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin against Nocardia brasiliensis in vitro in an experimental model of actinomycetoma in BALB/c mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:295-297.

- Welsh O. Treatment of actinomycetoma. Arch Med Res. 1993;24:413-415.

Practice Points

- Diagnosis of actinomycetoma is based on clinical manifestations including increased swelling and deformity of affected areas, presence of granulation tissue, scars, abscesses, sinus tracts, and a purulent exudate containing microorganisms.

- The feet are the most commonly affected location, followed by the trunk (back and chest), arms, forearms, legs, knees, and thighs.

- Specific diagnosis of actinomycetoma requires clinical examination as well as direct examination of culture and biopsy results.

- Overall, the cure rate for actinomycetoma ranges from 60% to 90%.

AACE: Updated lipid guidelines include ‘extreme risk’ category

according to a summary by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology.

Achieving such a low LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) level is possible with well-established medications such as a combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe and the newer, more clinically powerful agent PCSK9 inhibitors, Paul S. Jellinger, MD, chair of the guideline committee and professor of clinical medicine, University of Miami, said in an interview. The “extreme risk” category was derived largely from IMPROVE-IT and supporting meta-analyses.

The new category applies to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) who have any of the following risk factors:

• Progressive ASCVD including unstable angina after achieving an LDL-C level less than 70 mg/dL.

• Type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease stage 3 or 4, or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia.

• A history of premature ASCVD (before age 55 years in men, 65 years in women).

Heterozygous hypercholesterolemia is more common than many physicians realize, affecting as it does 1 in 250 people, Dr. Jellinger noted.

“Supporting evidence for the ‘extreme risk’ category with an LDL-C of less than 55 mg/dL was recently announced with the top line results from the FOURIER CVD outcome trial utilizing PCSK9-inhibitor therapy, which met both its primary and secondary endpoints,” he stressed.

PCSK9 inhibitors are extremely expensive, said Dr. Jellinger. “In my view, payers should not be denying patients who clearly meet the Food and Drug Administration approved indications for PCSK9 inhibitors and those within the extreme risk criteria. Yet, I have been made aware that 80% of insurance claims for PCSK9 inhibitors in these extremely high-risk and vulnerable patients are being denied.”

Inclusion in the updated AACE lipid management guidelines should strengthen PCSK9 inhibitors’ place among lipid-lowering drugs that are acceptable to insurance companies by making it clear that PCSK9 is appropriate and indicated for select patients, according to Dr. Jellinger.

Aside from creation of the extreme risk category, the AACE lipid guidelines discuss the available tools for making a global risk assessment of having a cardiac, vascular, or stroke event in the next 10 years, without favoring any one risk score. Among the systems discussed, with links, are the Framingham, MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis), Reynolds, and United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study risk scores.

The guidelines provide separate approaches to management of people at various ages. Another change from the 2012 guidelines is the establishment of acceptable and worrisome LDL-C levels in children: Acceptable is a level under 100 mg/dL, borderline is 100-129 mg/dL, and high is LDL-C at or above 130 mg/dL.

The guidelines, which will be published in full in the April issue of Endocrine Practice, are based largely on numerous clinical trials and studies, and in the end produced 87 recommendations, of which 45 are Grade A, 18 are Grade B, 15 are Grade C, and 9 are Grade D.

These are the first guidelines on lipid management from AACE since 2012. The executive summary of the guidelines is available at www.aace.com.

Dr. Jellinger reported receiving speakers honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BI-Lilly, Merck, and Novo Nordisk.

according to a summary by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology.

Achieving such a low LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) level is possible with well-established medications such as a combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe and the newer, more clinically powerful agent PCSK9 inhibitors, Paul S. Jellinger, MD, chair of the guideline committee and professor of clinical medicine, University of Miami, said in an interview. The “extreme risk” category was derived largely from IMPROVE-IT and supporting meta-analyses.

The new category applies to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) who have any of the following risk factors:

• Progressive ASCVD including unstable angina after achieving an LDL-C level less than 70 mg/dL.

• Type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease stage 3 or 4, or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia.

• A history of premature ASCVD (before age 55 years in men, 65 years in women).

Heterozygous hypercholesterolemia is more common than many physicians realize, affecting as it does 1 in 250 people, Dr. Jellinger noted.

“Supporting evidence for the ‘extreme risk’ category with an LDL-C of less than 55 mg/dL was recently announced with the top line results from the FOURIER CVD outcome trial utilizing PCSK9-inhibitor therapy, which met both its primary and secondary endpoints,” he stressed.

PCSK9 inhibitors are extremely expensive, said Dr. Jellinger. “In my view, payers should not be denying patients who clearly meet the Food and Drug Administration approved indications for PCSK9 inhibitors and those within the extreme risk criteria. Yet, I have been made aware that 80% of insurance claims for PCSK9 inhibitors in these extremely high-risk and vulnerable patients are being denied.”

Inclusion in the updated AACE lipid management guidelines should strengthen PCSK9 inhibitors’ place among lipid-lowering drugs that are acceptable to insurance companies by making it clear that PCSK9 is appropriate and indicated for select patients, according to Dr. Jellinger.

Aside from creation of the extreme risk category, the AACE lipid guidelines discuss the available tools for making a global risk assessment of having a cardiac, vascular, or stroke event in the next 10 years, without favoring any one risk score. Among the systems discussed, with links, are the Framingham, MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis), Reynolds, and United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study risk scores.

The guidelines provide separate approaches to management of people at various ages. Another change from the 2012 guidelines is the establishment of acceptable and worrisome LDL-C levels in children: Acceptable is a level under 100 mg/dL, borderline is 100-129 mg/dL, and high is LDL-C at or above 130 mg/dL.

The guidelines, which will be published in full in the April issue of Endocrine Practice, are based largely on numerous clinical trials and studies, and in the end produced 87 recommendations, of which 45 are Grade A, 18 are Grade B, 15 are Grade C, and 9 are Grade D.

These are the first guidelines on lipid management from AACE since 2012. The executive summary of the guidelines is available at www.aace.com.

Dr. Jellinger reported receiving speakers honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BI-Lilly, Merck, and Novo Nordisk.

according to a summary by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology.

Achieving such a low LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) level is possible with well-established medications such as a combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe and the newer, more clinically powerful agent PCSK9 inhibitors, Paul S. Jellinger, MD, chair of the guideline committee and professor of clinical medicine, University of Miami, said in an interview. The “extreme risk” category was derived largely from IMPROVE-IT and supporting meta-analyses.

The new category applies to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) who have any of the following risk factors:

• Progressive ASCVD including unstable angina after achieving an LDL-C level less than 70 mg/dL.

• Type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease stage 3 or 4, or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia.

• A history of premature ASCVD (before age 55 years in men, 65 years in women).

Heterozygous hypercholesterolemia is more common than many physicians realize, affecting as it does 1 in 250 people, Dr. Jellinger noted.

“Supporting evidence for the ‘extreme risk’ category with an LDL-C of less than 55 mg/dL was recently announced with the top line results from the FOURIER CVD outcome trial utilizing PCSK9-inhibitor therapy, which met both its primary and secondary endpoints,” he stressed.

PCSK9 inhibitors are extremely expensive, said Dr. Jellinger. “In my view, payers should not be denying patients who clearly meet the Food and Drug Administration approved indications for PCSK9 inhibitors and those within the extreme risk criteria. Yet, I have been made aware that 80% of insurance claims for PCSK9 inhibitors in these extremely high-risk and vulnerable patients are being denied.”

Inclusion in the updated AACE lipid management guidelines should strengthen PCSK9 inhibitors’ place among lipid-lowering drugs that are acceptable to insurance companies by making it clear that PCSK9 is appropriate and indicated for select patients, according to Dr. Jellinger.

Aside from creation of the extreme risk category, the AACE lipid guidelines discuss the available tools for making a global risk assessment of having a cardiac, vascular, or stroke event in the next 10 years, without favoring any one risk score. Among the systems discussed, with links, are the Framingham, MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis), Reynolds, and United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study risk scores.

The guidelines provide separate approaches to management of people at various ages. Another change from the 2012 guidelines is the establishment of acceptable and worrisome LDL-C levels in children: Acceptable is a level under 100 mg/dL, borderline is 100-129 mg/dL, and high is LDL-C at or above 130 mg/dL.

The guidelines, which will be published in full in the April issue of Endocrine Practice, are based largely on numerous clinical trials and studies, and in the end produced 87 recommendations, of which 45 are Grade A, 18 are Grade B, 15 are Grade C, and 9 are Grade D.

These are the first guidelines on lipid management from AACE since 2012. The executive summary of the guidelines is available at www.aace.com.

Dr. Jellinger reported receiving speakers honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BI-Lilly, Merck, and Novo Nordisk.

Bronchiolitis pathway adherence tied to shorter LOS, lower costs

and lower health care costs, according to Mersine A. Bryan, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle and her associates.

In a retrospective cohort study, researchers looked at 267 patients less than 24 months old diagnosed with bronchiolitis from December 2009 to July 2012. Levels of adherence were then categorized into low, middle, and high tertiles. Results show that adherence was highest for the inpatient quality indicators (mean score, 95) and lowest for the emergency department (ED) quality indicators (mean score, 79). The mean ED LOS was significantly shorter for cases with ED adherence scores in the highest versus the lowest tertile (90 vs. 140 minutes; P less than .05). There were no significant differences in mean inpatient LOS by inpatient adherence score tertiles. “However, the mean inpatient LOS was approximately 17 hours shorter for cases with combined ED/inpatient adherence scores in the highest, compared with the lowest tertile,” they said.

“Our study demonstrates that high adherence to evidence-based recommendations within a clinical pathway across the entire continuum of care, from the ED to the inpatient setting, is associated with lower costs and shorter LOS,” Dr. Bryan and associates concluded. “By improving adherence to evidence-based recommendations within a clinical pathway, we may be able to provide higher-value care by optimizing the quality of bronchiolitis care at lower costs and with shorter LOS.”

Read the full study in Pediatrics (doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3432).

and lower health care costs, according to Mersine A. Bryan, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle and her associates.

In a retrospective cohort study, researchers looked at 267 patients less than 24 months old diagnosed with bronchiolitis from December 2009 to July 2012. Levels of adherence were then categorized into low, middle, and high tertiles. Results show that adherence was highest for the inpatient quality indicators (mean score, 95) and lowest for the emergency department (ED) quality indicators (mean score, 79). The mean ED LOS was significantly shorter for cases with ED adherence scores in the highest versus the lowest tertile (90 vs. 140 minutes; P less than .05). There were no significant differences in mean inpatient LOS by inpatient adherence score tertiles. “However, the mean inpatient LOS was approximately 17 hours shorter for cases with combined ED/inpatient adherence scores in the highest, compared with the lowest tertile,” they said.

“Our study demonstrates that high adherence to evidence-based recommendations within a clinical pathway across the entire continuum of care, from the ED to the inpatient setting, is associated with lower costs and shorter LOS,” Dr. Bryan and associates concluded. “By improving adherence to evidence-based recommendations within a clinical pathway, we may be able to provide higher-value care by optimizing the quality of bronchiolitis care at lower costs and with shorter LOS.”

Read the full study in Pediatrics (doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3432).

and lower health care costs, according to Mersine A. Bryan, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle and her associates.

In a retrospective cohort study, researchers looked at 267 patients less than 24 months old diagnosed with bronchiolitis from December 2009 to July 2012. Levels of adherence were then categorized into low, middle, and high tertiles. Results show that adherence was highest for the inpatient quality indicators (mean score, 95) and lowest for the emergency department (ED) quality indicators (mean score, 79). The mean ED LOS was significantly shorter for cases with ED adherence scores in the highest versus the lowest tertile (90 vs. 140 minutes; P less than .05). There were no significant differences in mean inpatient LOS by inpatient adherence score tertiles. “However, the mean inpatient LOS was approximately 17 hours shorter for cases with combined ED/inpatient adherence scores in the highest, compared with the lowest tertile,” they said.

“Our study demonstrates that high adherence to evidence-based recommendations within a clinical pathway across the entire continuum of care, from the ED to the inpatient setting, is associated with lower costs and shorter LOS,” Dr. Bryan and associates concluded. “By improving adherence to evidence-based recommendations within a clinical pathway, we may be able to provide higher-value care by optimizing the quality of bronchiolitis care at lower costs and with shorter LOS.”

Read the full study in Pediatrics (doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3432).

FROM PEDIATRICS

Ultrasound guidance of early RA therapy doesn’t improve outcomes

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Rheumatologists who use musculoskeletal ultrasound to help guide a treat-to-target strategy in early rheumatoid arthritis may want to reconsider that practice in light of the results of a recent randomized trial known as the TaSER study, Michael E. Weinblatt, MD, observed at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

In TaSER, Scottish investigators randomized 111 newly diagnosed early rheumatoid arthritis patients to an intensive treat-to-target strategy guided by 28-joint Disease Activity Score with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) alone or in conjunction with musculoskeletal ultrasound assessment of disease activity in a limited joint set.

The stepped treatment escalation regimen began with methotrexate monotherapy, followed by the addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to methotrexate as triple therapy, then etanercept plus triple therapy.

The primary outcome was improvement in DAS44 at 18 months. Both groups experienced similarly robust improvements: a mean 2.69-point reduction in the ultrasound group and a 2.59-point decrease in the control arm. Nor were there any between-group differences in radiographic or MRI erosions. This was the case even though the ultrasound group received more intensive therapy (Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jun;75[6]:1043-50).

“This doesn’t mean that there’s not great value in ultrasound to evaluate disease activity, but I’m not convinced that using ultrasound to guide your treatment per se shows any advantages over a good clinical evaluation of the patient,” concluded Dr. Weinblatt, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

He reported receiving research grants from half a dozen companies and serving as a consultant to more than two dozen.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Rheumatologists who use musculoskeletal ultrasound to help guide a treat-to-target strategy in early rheumatoid arthritis may want to reconsider that practice in light of the results of a recent randomized trial known as the TaSER study, Michael E. Weinblatt, MD, observed at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

In TaSER, Scottish investigators randomized 111 newly diagnosed early rheumatoid arthritis patients to an intensive treat-to-target strategy guided by 28-joint Disease Activity Score with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) alone or in conjunction with musculoskeletal ultrasound assessment of disease activity in a limited joint set.

The stepped treatment escalation regimen began with methotrexate monotherapy, followed by the addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to methotrexate as triple therapy, then etanercept plus triple therapy.

The primary outcome was improvement in DAS44 at 18 months. Both groups experienced similarly robust improvements: a mean 2.69-point reduction in the ultrasound group and a 2.59-point decrease in the control arm. Nor were there any between-group differences in radiographic or MRI erosions. This was the case even though the ultrasound group received more intensive therapy (Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jun;75[6]:1043-50).

“This doesn’t mean that there’s not great value in ultrasound to evaluate disease activity, but I’m not convinced that using ultrasound to guide your treatment per se shows any advantages over a good clinical evaluation of the patient,” concluded Dr. Weinblatt, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

He reported receiving research grants from half a dozen companies and serving as a consultant to more than two dozen.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Rheumatologists who use musculoskeletal ultrasound to help guide a treat-to-target strategy in early rheumatoid arthritis may want to reconsider that practice in light of the results of a recent randomized trial known as the TaSER study, Michael E. Weinblatt, MD, observed at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

In TaSER, Scottish investigators randomized 111 newly diagnosed early rheumatoid arthritis patients to an intensive treat-to-target strategy guided by 28-joint Disease Activity Score with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) alone or in conjunction with musculoskeletal ultrasound assessment of disease activity in a limited joint set.

The stepped treatment escalation regimen began with methotrexate monotherapy, followed by the addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to methotrexate as triple therapy, then etanercept plus triple therapy.

The primary outcome was improvement in DAS44 at 18 months. Both groups experienced similarly robust improvements: a mean 2.69-point reduction in the ultrasound group and a 2.59-point decrease in the control arm. Nor were there any between-group differences in radiographic or MRI erosions. This was the case even though the ultrasound group received more intensive therapy (Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jun;75[6]:1043-50).

“This doesn’t mean that there’s not great value in ultrasound to evaluate disease activity, but I’m not convinced that using ultrasound to guide your treatment per se shows any advantages over a good clinical evaluation of the patient,” concluded Dr. Weinblatt, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

He reported receiving research grants from half a dozen companies and serving as a consultant to more than two dozen.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WINTER RHEUMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Fecal microbiota transplantation a decolonization treatment option

The use of fecal microbiota transplantation is an option to eradicate highly drug-resistant enteric bacteria carriage, according to results from a small pilot study conducted by French investigators.

“A rapid and dramatic emergence of highly drug-resistant enteric bacteria (HDREB), i.e., carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), is occurring worldwide,” researchers led by Benjamin Davido, MD, of the infectious diseases unit at Raymond Poincaré Teaching Hospital, Garches, France, wrote in a study published online Feb. 1 in the Journal of Hospital Infection. “Patients carrying these bacteria are at risk of developing severe infections due to these bacteria; these infections are associated with a high mortality rate, partially because of inappropriate antimicrobial treatment.”

Citing recent studies that have demonstrated the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) as an accepted therapy to prevent recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, Dr. Davido and his associates prospectively identified eight different case reports of FMT used in adults for intestinal decolonization from extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Enterobacteriaceae, VRE, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Patients on immunosuppressive agents were excluded from the study, as were those taking antibiotics at the time of FMT (J Hosp Infect. 2017 Feb. 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.02.001).

The protocol for the procedure involved insertion of a nasoduodenal tube the day before FMT in order to perform a bowel lavage with XPrep solution. FMT was performed using a frozen preparation of fecal microbiota from a universal donor who was previously screened for potential diseases. The main outcome of interest was time to successful decolonization following FMT, which was determined by at least two consecutive negative rectal swabs at a 1-week interval during a follow-up of 3 months.

The mean age of the eight patients was 70 years, their median Charlson comorbidity index score was 5, and the median duration of carriage of HDREB before FMT was 83 days. The researchers observed that 1 month after FMT, two patients were free from CRE colonization, while one more patient was free from VRE after 3 months. Five patients received antibiotic during follow-up. Among them, one patient was decolonized at 1 month, while another was decolonized at 3 months. One patient with cirrhosis and persistent VRE carriage died 3 months after FMT from ascetic fluid infection and VRE bacteremia. No other adverse events were reported.

“In a context where no other efficient strategy is available, our first results show that FMT seems to be safe, with an impact on CRE decolonization at 1 month and on VRE decolonization at 3 months,” the researchers concluded. “Of particular importance, there was no recolonization after the intervention, which is contrary to decolonization with antibiotics. However, our study has important limitations in that the sample size was very small, it was nonrandomized, and follow-up was limited to a 3-month period.” They noted that at least five trials are underway to investigate the impact of FMT on multidrug resistant organism bacterial decolonization. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

The use of fecal microbiota transplantation is an option to eradicate highly drug-resistant enteric bacteria carriage, according to results from a small pilot study conducted by French investigators.

“A rapid and dramatic emergence of highly drug-resistant enteric bacteria (HDREB), i.e., carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), is occurring worldwide,” researchers led by Benjamin Davido, MD, of the infectious diseases unit at Raymond Poincaré Teaching Hospital, Garches, France, wrote in a study published online Feb. 1 in the Journal of Hospital Infection. “Patients carrying these bacteria are at risk of developing severe infections due to these bacteria; these infections are associated with a high mortality rate, partially because of inappropriate antimicrobial treatment.”

Citing recent studies that have demonstrated the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) as an accepted therapy to prevent recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, Dr. Davido and his associates prospectively identified eight different case reports of FMT used in adults for intestinal decolonization from extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Enterobacteriaceae, VRE, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Patients on immunosuppressive agents were excluded from the study, as were those taking antibiotics at the time of FMT (J Hosp Infect. 2017 Feb. 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.02.001).

The protocol for the procedure involved insertion of a nasoduodenal tube the day before FMT in order to perform a bowel lavage with XPrep solution. FMT was performed using a frozen preparation of fecal microbiota from a universal donor who was previously screened for potential diseases. The main outcome of interest was time to successful decolonization following FMT, which was determined by at least two consecutive negative rectal swabs at a 1-week interval during a follow-up of 3 months.

The mean age of the eight patients was 70 years, their median Charlson comorbidity index score was 5, and the median duration of carriage of HDREB before FMT was 83 days. The researchers observed that 1 month after FMT, two patients were free from CRE colonization, while one more patient was free from VRE after 3 months. Five patients received antibiotic during follow-up. Among them, one patient was decolonized at 1 month, while another was decolonized at 3 months. One patient with cirrhosis and persistent VRE carriage died 3 months after FMT from ascetic fluid infection and VRE bacteremia. No other adverse events were reported.

“In a context where no other efficient strategy is available, our first results show that FMT seems to be safe, with an impact on CRE decolonization at 1 month and on VRE decolonization at 3 months,” the researchers concluded. “Of particular importance, there was no recolonization after the intervention, which is contrary to decolonization with antibiotics. However, our study has important limitations in that the sample size was very small, it was nonrandomized, and follow-up was limited to a 3-month period.” They noted that at least five trials are underway to investigate the impact of FMT on multidrug resistant organism bacterial decolonization. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

The use of fecal microbiota transplantation is an option to eradicate highly drug-resistant enteric bacteria carriage, according to results from a small pilot study conducted by French investigators.

“A rapid and dramatic emergence of highly drug-resistant enteric bacteria (HDREB), i.e., carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), is occurring worldwide,” researchers led by Benjamin Davido, MD, of the infectious diseases unit at Raymond Poincaré Teaching Hospital, Garches, France, wrote in a study published online Feb. 1 in the Journal of Hospital Infection. “Patients carrying these bacteria are at risk of developing severe infections due to these bacteria; these infections are associated with a high mortality rate, partially because of inappropriate antimicrobial treatment.”

Citing recent studies that have demonstrated the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) as an accepted therapy to prevent recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, Dr. Davido and his associates prospectively identified eight different case reports of FMT used in adults for intestinal decolonization from extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Enterobacteriaceae, VRE, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Patients on immunosuppressive agents were excluded from the study, as were those taking antibiotics at the time of FMT (J Hosp Infect. 2017 Feb. 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.02.001).

The protocol for the procedure involved insertion of a nasoduodenal tube the day before FMT in order to perform a bowel lavage with XPrep solution. FMT was performed using a frozen preparation of fecal microbiota from a universal donor who was previously screened for potential diseases. The main outcome of interest was time to successful decolonization following FMT, which was determined by at least two consecutive negative rectal swabs at a 1-week interval during a follow-up of 3 months.

The mean age of the eight patients was 70 years, their median Charlson comorbidity index score was 5, and the median duration of carriage of HDREB before FMT was 83 days. The researchers observed that 1 month after FMT, two patients were free from CRE colonization, while one more patient was free from VRE after 3 months. Five patients received antibiotic during follow-up. Among them, one patient was decolonized at 1 month, while another was decolonized at 3 months. One patient with cirrhosis and persistent VRE carriage died 3 months after FMT from ascetic fluid infection and VRE bacteremia. No other adverse events were reported.

“In a context where no other efficient strategy is available, our first results show that FMT seems to be safe, with an impact on CRE decolonization at 1 month and on VRE decolonization at 3 months,” the researchers concluded. “Of particular importance, there was no recolonization after the intervention, which is contrary to decolonization with antibiotics. However, our study has important limitations in that the sample size was very small, it was nonrandomized, and follow-up was limited to a 3-month period.” They noted that at least five trials are underway to investigate the impact of FMT on multidrug resistant organism bacterial decolonization. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF HOSPITAL INFECTION

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of eight patients who underwent fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) digestive tract decolonization, three achieved decolonization after 3 months.

Data source: A prospective study of eight cases of FMT used in adults for intestinal decolonization from drug-resistant enteric bacteria carriage.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Specific polymorphisms excluded in hemophilic arthropathy

Carriers of a hemochromatosis (HFE) gene mutation or a long (GT)n-repeat length within the HMOX1 promoter regions did not appear to have an increase in hemophilic arthropathy.

In 201 blood samples from patients with severe hemophilia A or B and 37 from patients with moderate disease, neither the presence of an HFE mutation nor a long (GT)n-repeat length was associated with an increase in joint damage. The assessment was based on Pettersson score after adjustment for disease severity, presence of inhibitors, annual joint bleeding rate (AJBR), age at Pettersson score and at clinic entrance, and birth cohort (standardized beta = 0.033 and -0.022, respectively), Lize F. van Vulpen, MD, of University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association of Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

Study subjects had a median age of 43 years, median AJBRs of 2.5 and 0.5 for severe and moderate disease, respectively, and median Pettersson scores of 22 and 4 in the groups, respectively. An HFE mutation was detected in 91 patients, and their levels of ferritin, iron, and transferrin saturation were significantly increased, but other baseline characteristic were similar in those with and without HFE mutation, and regardless of (GT)n-repeat length.

The marked heterogeneity in joint damage seen among hemophilia patients was hypothesized in this study to be associated with differences in iron handling, but the findings failed to support that hypothesis, Dr. van Vulpen concluded.

Dr. van Vulpen reported having no disclosures.

Carriers of a hemochromatosis (HFE) gene mutation or a long (GT)n-repeat length within the HMOX1 promoter regions did not appear to have an increase in hemophilic arthropathy.

In 201 blood samples from patients with severe hemophilia A or B and 37 from patients with moderate disease, neither the presence of an HFE mutation nor a long (GT)n-repeat length was associated with an increase in joint damage. The assessment was based on Pettersson score after adjustment for disease severity, presence of inhibitors, annual joint bleeding rate (AJBR), age at Pettersson score and at clinic entrance, and birth cohort (standardized beta = 0.033 and -0.022, respectively), Lize F. van Vulpen, MD, of University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association of Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

Study subjects had a median age of 43 years, median AJBRs of 2.5 and 0.5 for severe and moderate disease, respectively, and median Pettersson scores of 22 and 4 in the groups, respectively. An HFE mutation was detected in 91 patients, and their levels of ferritin, iron, and transferrin saturation were significantly increased, but other baseline characteristic were similar in those with and without HFE mutation, and regardless of (GT)n-repeat length.