User login

Esophageal variceal bleeding, portal hypertension tied to recurrent pediatric GI bleeds

Readmission to the hospital after acute GI bleeding in children is most often associated with an initial diagnosis of portal hypertension or esophageal variceal hemorrhage, based on data from a retrospective study of 9,902 patients.

Rebleeding in adults may be predicted by endoscopic characteristics of the bleeding source in some cases, but “there is still a considerable subgroup of children admitted with acute gastrointestinal bleeding and not endoscoped but in whom we do not have any measure to predict rebleeding including after discharge,” Thomas M. Attard, MD, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo., and his colleagues said.

The study included children aged 1-21 years with upper or indeterminate GI bleeding who were discharged from 49 pediatric hospitals between January 1, 2007 and September 30, 2015. Overall, 1,460 children (16%) were readmitted at least once within 30 days, with 72 readmitted twice and an average of 10 days’ time to readmission.

Readmission for recurrent bleeding was most frequently associated with an initial diagnosis of portal hypertension (20%) or esophageal variceal hemorrhage (20%). Children who had undergone endoscopy (odds ratio, 0.77) or Meckel’s scan (OR, 0.51) on initial admission were least likely to require readmission.

Children with one or two complex chronic conditions were almost twice as likely to be readmitted than were those with no complex chronic conditions, and a longer initial hospital stay and early treatment with proton pump inhibitors were associated with increased likelihood of readmission. “These may be indicative of more medically frail patients and greater severity of initial illness, respectively,” the researchers said. They found no association between increased risk of readmission and demographic factors including age, sex, race, and urban vs. rural residence (J Pediatr. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.044).

Readmission to the hospital after acute GI bleeding in children is most often associated with an initial diagnosis of portal hypertension or esophageal variceal hemorrhage, based on data from a retrospective study of 9,902 patients.

Rebleeding in adults may be predicted by endoscopic characteristics of the bleeding source in some cases, but “there is still a considerable subgroup of children admitted with acute gastrointestinal bleeding and not endoscoped but in whom we do not have any measure to predict rebleeding including after discharge,” Thomas M. Attard, MD, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo., and his colleagues said.

The study included children aged 1-21 years with upper or indeterminate GI bleeding who were discharged from 49 pediatric hospitals between January 1, 2007 and September 30, 2015. Overall, 1,460 children (16%) were readmitted at least once within 30 days, with 72 readmitted twice and an average of 10 days’ time to readmission.

Readmission for recurrent bleeding was most frequently associated with an initial diagnosis of portal hypertension (20%) or esophageal variceal hemorrhage (20%). Children who had undergone endoscopy (odds ratio, 0.77) or Meckel’s scan (OR, 0.51) on initial admission were least likely to require readmission.

Children with one or two complex chronic conditions were almost twice as likely to be readmitted than were those with no complex chronic conditions, and a longer initial hospital stay and early treatment with proton pump inhibitors were associated with increased likelihood of readmission. “These may be indicative of more medically frail patients and greater severity of initial illness, respectively,” the researchers said. They found no association between increased risk of readmission and demographic factors including age, sex, race, and urban vs. rural residence (J Pediatr. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.044).

Readmission to the hospital after acute GI bleeding in children is most often associated with an initial diagnosis of portal hypertension or esophageal variceal hemorrhage, based on data from a retrospective study of 9,902 patients.

Rebleeding in adults may be predicted by endoscopic characteristics of the bleeding source in some cases, but “there is still a considerable subgroup of children admitted with acute gastrointestinal bleeding and not endoscoped but in whom we do not have any measure to predict rebleeding including after discharge,” Thomas M. Attard, MD, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo., and his colleagues said.

The study included children aged 1-21 years with upper or indeterminate GI bleeding who were discharged from 49 pediatric hospitals between January 1, 2007 and September 30, 2015. Overall, 1,460 children (16%) were readmitted at least once within 30 days, with 72 readmitted twice and an average of 10 days’ time to readmission.

Readmission for recurrent bleeding was most frequently associated with an initial diagnosis of portal hypertension (20%) or esophageal variceal hemorrhage (20%). Children who had undergone endoscopy (odds ratio, 0.77) or Meckel’s scan (OR, 0.51) on initial admission were least likely to require readmission.

Children with one or two complex chronic conditions were almost twice as likely to be readmitted than were those with no complex chronic conditions, and a longer initial hospital stay and early treatment with proton pump inhibitors were associated with increased likelihood of readmission. “These may be indicative of more medically frail patients and greater severity of initial illness, respectively,” the researchers said. They found no association between increased risk of readmission and demographic factors including age, sex, race, and urban vs. rural residence (J Pediatr. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.044).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

ICD-10 Update: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Hair Disorders in the Skin of Color Population: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

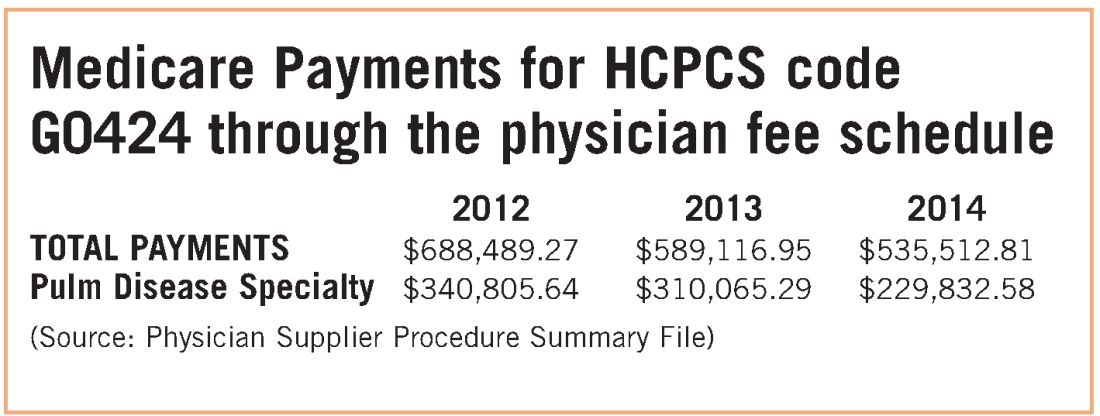

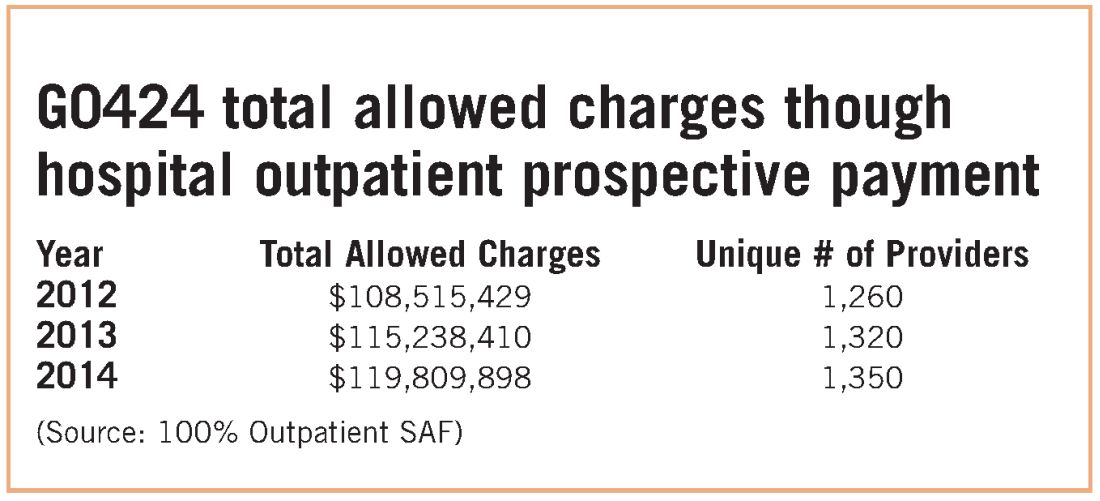

Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2015 threatens growth of pulmonary rehab

In late 2015, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) to address numerous wide-ranging budget concerns, including issues related to agriculture, pensions, the strategic petroleum reserve, along with some Medicare issues. Section 603 of BBA is now coming back to haunt pulmonary rehabilitation services.

The intent of Section 603 is reasonable – to address the phenomenon of hospitals purchasing physician practices to take advantage of payment differentials between identical or virtually identical services when comparing the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (HOPPS) and the physician fee schedule (PFS). For example, an orthopedic practice might own its own MRI and related support services. It will bill for those services under the PFS. However, if the practice sells that segment of the revenue stream (the MRI assets, etc) to a hospital, the hospital can bill Medicare for those same services under the hospital outpatient prospective payment system at an amount notably higher than the PFS payment.

To address this payment aberration, Congress instructed the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to craft a system to preclude a hospital from such behavior. If a hospital offers new or expanded outpatient services, it could NOT bill Medicare under the hospital outpatient services methodology and would be required to bill under the PFS payment methodology. Importantly, a few exemptions exist. If the new or expanded service is within 250 yards of the main hospital campus, the outpatient billing methodology is permitted. Likewise, if expansion of a current off-campus service occurs at the same location of the current off-site service, the hospital may continue to bill under the outpatient rules. Several other technical exceptions are permitted, for example construction planned prior to passage of BBA.

The implications for pulmonary rehabilitation are critical to its growth. A hospital that wishes to expand its current program and bill under the hospital outpatient methodology MUST do so by expanding at its current location. An expansion at a new location that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus triggers Section 603 provisions, and the hospital will bill at the physician fee schedule rate. Because the PFS payment rate is just over half of the payment rate for HOPPS payment, it is unlikely that a hospital would expand an existing program or establish a new one if it would be forced to bill under the lower rate.

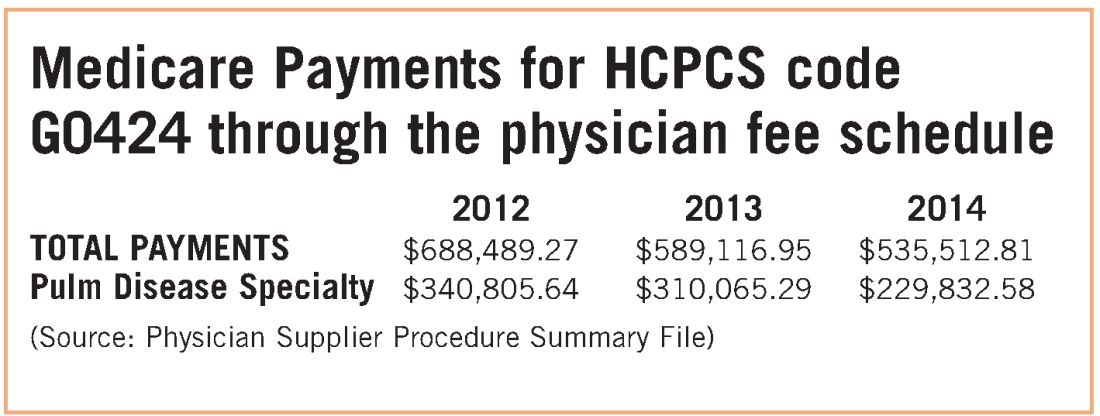

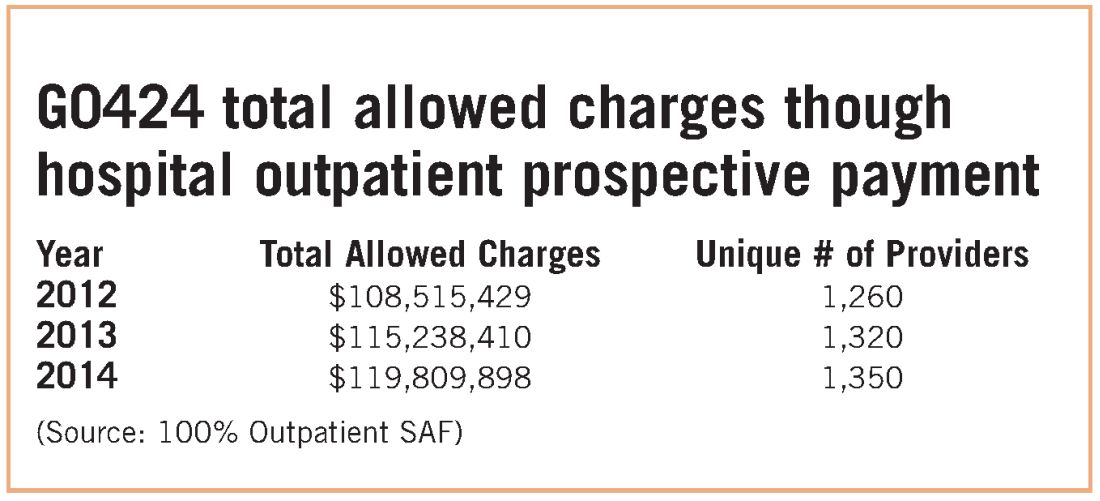

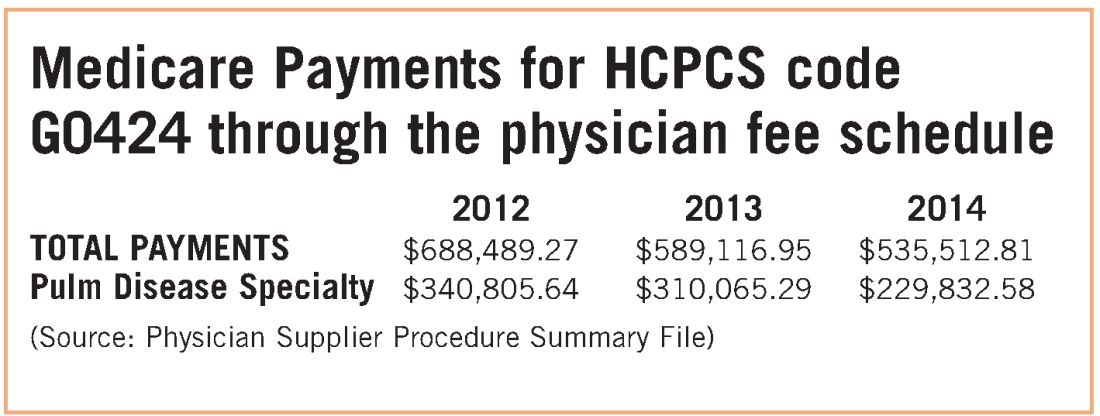

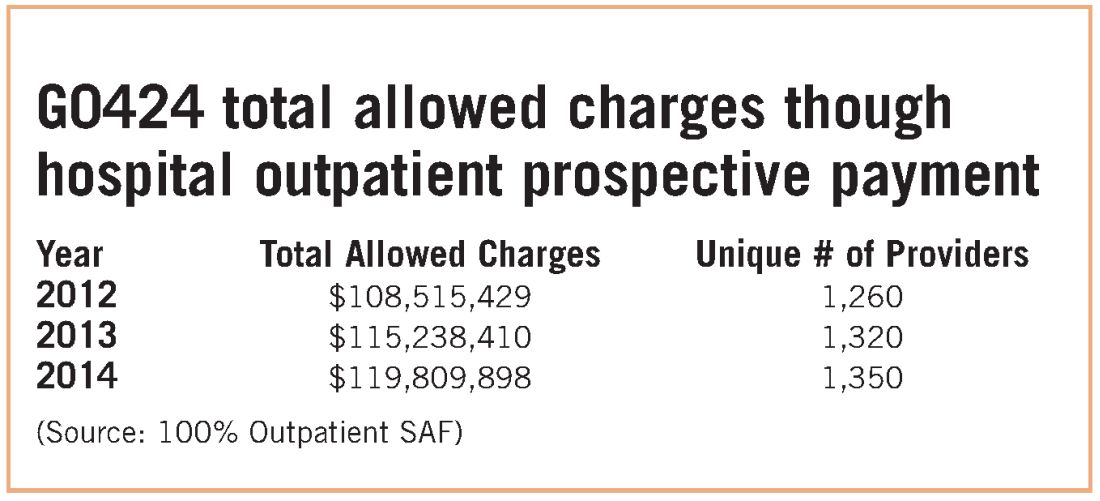

While congressional logic may be relatively understandable, for pulmonary medicine, it is based on the premise that a hospital would purchase a pulmonary practice because that practice had a lucrative pulmonary rehabilitation services cash flow. NAMDRC and other societies were able to document major flaws in the basic premise, resulting in very problematic unintended consequences. A detailed review of Medicare claims data provides strong evidence that pulmonary practices simply do not provide pulmonary rehab services.

These data strongly indicate that G0424 pulmonary practice physician office billing for the most recent year data are available ($230K), compared with hospital outpatient allowed charges ($119M), is less than two-tenths of 1% of billing through the hospital setting. To argue that hospitals are purchasing pulmonary practices for financial gain tied to pulmonary rehab services defies Medicare data, as well as financial logic. If the CMS premise was valid, one would expect the aggregate physician office billing to be much greater than $535K. In discussions with CMS, the Agency did agree that there are likely to be unintended consequences related to Section 603 implementation. The Agency also emphasizes that it does not have the statutory authority for a “carve out” exemption. CMS stated that even if it agreed with us, it simply lacked the authority to exempt pulmonary rehab services. CMS also agreed that there is growing evidence that pulmonary rehab is a underutilized service that may very well save the program money through reduced hospitalizations and rehospitalizations, but it has little choice to implement the statute as Congress so mandated.

Therefore, the only solution is a legislative one. NAMDRC and other societies are seriously considering approaching Congress for such resolution.

In late 2015, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) to address numerous wide-ranging budget concerns, including issues related to agriculture, pensions, the strategic petroleum reserve, along with some Medicare issues. Section 603 of BBA is now coming back to haunt pulmonary rehabilitation services.

The intent of Section 603 is reasonable – to address the phenomenon of hospitals purchasing physician practices to take advantage of payment differentials between identical or virtually identical services when comparing the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (HOPPS) and the physician fee schedule (PFS). For example, an orthopedic practice might own its own MRI and related support services. It will bill for those services under the PFS. However, if the practice sells that segment of the revenue stream (the MRI assets, etc) to a hospital, the hospital can bill Medicare for those same services under the hospital outpatient prospective payment system at an amount notably higher than the PFS payment.

To address this payment aberration, Congress instructed the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to craft a system to preclude a hospital from such behavior. If a hospital offers new or expanded outpatient services, it could NOT bill Medicare under the hospital outpatient services methodology and would be required to bill under the PFS payment methodology. Importantly, a few exemptions exist. If the new or expanded service is within 250 yards of the main hospital campus, the outpatient billing methodology is permitted. Likewise, if expansion of a current off-campus service occurs at the same location of the current off-site service, the hospital may continue to bill under the outpatient rules. Several other technical exceptions are permitted, for example construction planned prior to passage of BBA.

The implications for pulmonary rehabilitation are critical to its growth. A hospital that wishes to expand its current program and bill under the hospital outpatient methodology MUST do so by expanding at its current location. An expansion at a new location that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus triggers Section 603 provisions, and the hospital will bill at the physician fee schedule rate. Because the PFS payment rate is just over half of the payment rate for HOPPS payment, it is unlikely that a hospital would expand an existing program or establish a new one if it would be forced to bill under the lower rate.

While congressional logic may be relatively understandable, for pulmonary medicine, it is based on the premise that a hospital would purchase a pulmonary practice because that practice had a lucrative pulmonary rehabilitation services cash flow. NAMDRC and other societies were able to document major flaws in the basic premise, resulting in very problematic unintended consequences. A detailed review of Medicare claims data provides strong evidence that pulmonary practices simply do not provide pulmonary rehab services.

These data strongly indicate that G0424 pulmonary practice physician office billing for the most recent year data are available ($230K), compared with hospital outpatient allowed charges ($119M), is less than two-tenths of 1% of billing through the hospital setting. To argue that hospitals are purchasing pulmonary practices for financial gain tied to pulmonary rehab services defies Medicare data, as well as financial logic. If the CMS premise was valid, one would expect the aggregate physician office billing to be much greater than $535K. In discussions with CMS, the Agency did agree that there are likely to be unintended consequences related to Section 603 implementation. The Agency also emphasizes that it does not have the statutory authority for a “carve out” exemption. CMS stated that even if it agreed with us, it simply lacked the authority to exempt pulmonary rehab services. CMS also agreed that there is growing evidence that pulmonary rehab is a underutilized service that may very well save the program money through reduced hospitalizations and rehospitalizations, but it has little choice to implement the statute as Congress so mandated.

Therefore, the only solution is a legislative one. NAMDRC and other societies are seriously considering approaching Congress for such resolution.

In late 2015, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) to address numerous wide-ranging budget concerns, including issues related to agriculture, pensions, the strategic petroleum reserve, along with some Medicare issues. Section 603 of BBA is now coming back to haunt pulmonary rehabilitation services.

The intent of Section 603 is reasonable – to address the phenomenon of hospitals purchasing physician practices to take advantage of payment differentials between identical or virtually identical services when comparing the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (HOPPS) and the physician fee schedule (PFS). For example, an orthopedic practice might own its own MRI and related support services. It will bill for those services under the PFS. However, if the practice sells that segment of the revenue stream (the MRI assets, etc) to a hospital, the hospital can bill Medicare for those same services under the hospital outpatient prospective payment system at an amount notably higher than the PFS payment.

To address this payment aberration, Congress instructed the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to craft a system to preclude a hospital from such behavior. If a hospital offers new or expanded outpatient services, it could NOT bill Medicare under the hospital outpatient services methodology and would be required to bill under the PFS payment methodology. Importantly, a few exemptions exist. If the new or expanded service is within 250 yards of the main hospital campus, the outpatient billing methodology is permitted. Likewise, if expansion of a current off-campus service occurs at the same location of the current off-site service, the hospital may continue to bill under the outpatient rules. Several other technical exceptions are permitted, for example construction planned prior to passage of BBA.

The implications for pulmonary rehabilitation are critical to its growth. A hospital that wishes to expand its current program and bill under the hospital outpatient methodology MUST do so by expanding at its current location. An expansion at a new location that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus triggers Section 603 provisions, and the hospital will bill at the physician fee schedule rate. Because the PFS payment rate is just over half of the payment rate for HOPPS payment, it is unlikely that a hospital would expand an existing program or establish a new one if it would be forced to bill under the lower rate.

While congressional logic may be relatively understandable, for pulmonary medicine, it is based on the premise that a hospital would purchase a pulmonary practice because that practice had a lucrative pulmonary rehabilitation services cash flow. NAMDRC and other societies were able to document major flaws in the basic premise, resulting in very problematic unintended consequences. A detailed review of Medicare claims data provides strong evidence that pulmonary practices simply do not provide pulmonary rehab services.

These data strongly indicate that G0424 pulmonary practice physician office billing for the most recent year data are available ($230K), compared with hospital outpatient allowed charges ($119M), is less than two-tenths of 1% of billing through the hospital setting. To argue that hospitals are purchasing pulmonary practices for financial gain tied to pulmonary rehab services defies Medicare data, as well as financial logic. If the CMS premise was valid, one would expect the aggregate physician office billing to be much greater than $535K. In discussions with CMS, the Agency did agree that there are likely to be unintended consequences related to Section 603 implementation. The Agency also emphasizes that it does not have the statutory authority for a “carve out” exemption. CMS stated that even if it agreed with us, it simply lacked the authority to exempt pulmonary rehab services. CMS also agreed that there is growing evidence that pulmonary rehab is a underutilized service that may very well save the program money through reduced hospitalizations and rehospitalizations, but it has little choice to implement the statute as Congress so mandated.

Therefore, the only solution is a legislative one. NAMDRC and other societies are seriously considering approaching Congress for such resolution.

Survey: Most military family physicians wary of transgender treatments

The U.S. military now allows transgender people to serve openly, and all medical personnel are supposed to be trained in their treatment – including care related to gender transition – by June 2017.

But a new survey of 204 family physicians who work for the military shows that most aren’t willing to prescribe cross-hormone treatment to eligible adult transgender patients.

In addition, “we found that most military clinicians did not receive any formal training on transgender care during their medical education, most had not treated a patient with gender dysphoria, and most had not received sufficient training to prescribe cross-hormone therapy,” said Natasha A. Schvey, PhD, an assistant professor with the medical and clinical psychology department at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and lead author of a new study that summarizes the survey findings.

An estimated 12,800 transgender people serve in the U.S. military, and researchers believe that they make up a larger proportion of the military population than in the general population.

In October 2016, the Department of Defense ended its ban on service by transgender troops. A policy statement says: “Service members with a diagnosis from a military medical provider indicating that gender transition is medically necessary will be provided medical care and treatment for the diagnosed medical condition, in the same manner as other medical care and treatment.”

For the new study, Dr. Schvey and her associates surveyed 204 of the approximately 1,700 family physicians who serve the military (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0136). The survey respondents had all attended an annual meeting in March 2016.

Most respondents were male (62.8%) and white (85.5%); 21.7% were residents. The highest number of respondents (42.6%) worked for the U.S. Air Force.

Almost three-quarters of the respondents said that they had received no training or medical education in gender dysphoria, and 62.7% said they had never treated a transgender patient as a physician.

Just under half (47.1%) of respondents – 82 – said they would prescribe cross-hormone therapy to eligible adult patients, but only one would do so independently. The others would only do so with additional education (7.5% of all responding physicians), the help of an experienced clinician (17.2%), or both (21.8%).

The other 52.9% said they wouldn’t prescribe the hormone therapy. Eight percent of all responding physicians blamed ethical concerns, 19.5% pointed to lack of comfort, and 25.3% mentioned both, the investigators reported.

Why are so many physicians so uncomfortable?

Dr. Schvey said the survey design doesn’t allow for speculation about what the ethical concerns might be, but “the data did indicate that hours of training on transgender care were directly associated with the likelihood of prescribing cross-hormone therapy. Therefore, some of the lack of comfort may be due to lack of experience and adequate training.”

Although family physicians are generally used to treating patients with hormones for contraception and to treat perimenopausal symptoms and hypogonadism, many don’t know about dosing regimens and other information regarding their use in transgender patients, study coauthor David A. Klein, MD, assistant professor of family medicine and pediatrics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, said in an interview. And, he noted, “some are unaware that provision of cross-hormone therapy is within their scope of care.”

Going forward, “given that greater education in transgender care is associated with increased competency,” Dr. Schvey said in an interview, “it will be important to assess the training of military physicians to ensure skill and sensitivity in treating patients who identify as transgender.”

The study had no specific funding, and the authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

I first learned the term transsexual from a 1972 publication by the American Medical Association titled “Human Sexuality.” I found the textbook on my father’s bookshelf as a 10-year-old and for the first time found a word to describe my inner world.

Up until 2016, transgender individuals in the military were not given appropriate medical or psychological assistance. They were forced to seek help in secret, outside the military health care system, or to await discharge proceedings.

Although the situation has improved markedly, there is still a long way to go. We need better protocols for individuals who wish to transition while active duty, for retirees, and their family members. We need to aid them in preserving their fertility, and we need to foster an environment of openness where no soldier feels like he or she is isolated from fellow service members owing to gender identity.

Although I completed my medical training as a male, today I serve as a female physician in every respect within the Department of Defense. Last month, I graduated the Army Medical Department’s Advanced Course with honors, and now I look forward to the second half of my military career being treated like any other capable military physician. My hope is that over time all clinicians gain comfort and skill in treating transgender persons.

Jamie L. Henry, MD, is with the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md. These comments were taken from an editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0140) accompanying the report by Dr. Schvey and her associates.

I first learned the term transsexual from a 1972 publication by the American Medical Association titled “Human Sexuality.” I found the textbook on my father’s bookshelf as a 10-year-old and for the first time found a word to describe my inner world.

Up until 2016, transgender individuals in the military were not given appropriate medical or psychological assistance. They were forced to seek help in secret, outside the military health care system, or to await discharge proceedings.

Although the situation has improved markedly, there is still a long way to go. We need better protocols for individuals who wish to transition while active duty, for retirees, and their family members. We need to aid them in preserving their fertility, and we need to foster an environment of openness where no soldier feels like he or she is isolated from fellow service members owing to gender identity.

Although I completed my medical training as a male, today I serve as a female physician in every respect within the Department of Defense. Last month, I graduated the Army Medical Department’s Advanced Course with honors, and now I look forward to the second half of my military career being treated like any other capable military physician. My hope is that over time all clinicians gain comfort and skill in treating transgender persons.

Jamie L. Henry, MD, is with the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md. These comments were taken from an editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0140) accompanying the report by Dr. Schvey and her associates.

I first learned the term transsexual from a 1972 publication by the American Medical Association titled “Human Sexuality.” I found the textbook on my father’s bookshelf as a 10-year-old and for the first time found a word to describe my inner world.

Up until 2016, transgender individuals in the military were not given appropriate medical or psychological assistance. They were forced to seek help in secret, outside the military health care system, or to await discharge proceedings.

Although the situation has improved markedly, there is still a long way to go. We need better protocols for individuals who wish to transition while active duty, for retirees, and their family members. We need to aid them in preserving their fertility, and we need to foster an environment of openness where no soldier feels like he or she is isolated from fellow service members owing to gender identity.

Although I completed my medical training as a male, today I serve as a female physician in every respect within the Department of Defense. Last month, I graduated the Army Medical Department’s Advanced Course with honors, and now I look forward to the second half of my military career being treated like any other capable military physician. My hope is that over time all clinicians gain comfort and skill in treating transgender persons.

Jamie L. Henry, MD, is with the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md. These comments were taken from an editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0140) accompanying the report by Dr. Schvey and her associates.

The U.S. military now allows transgender people to serve openly, and all medical personnel are supposed to be trained in their treatment – including care related to gender transition – by June 2017.

But a new survey of 204 family physicians who work for the military shows that most aren’t willing to prescribe cross-hormone treatment to eligible adult transgender patients.

In addition, “we found that most military clinicians did not receive any formal training on transgender care during their medical education, most had not treated a patient with gender dysphoria, and most had not received sufficient training to prescribe cross-hormone therapy,” said Natasha A. Schvey, PhD, an assistant professor with the medical and clinical psychology department at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and lead author of a new study that summarizes the survey findings.

An estimated 12,800 transgender people serve in the U.S. military, and researchers believe that they make up a larger proportion of the military population than in the general population.

In October 2016, the Department of Defense ended its ban on service by transgender troops. A policy statement says: “Service members with a diagnosis from a military medical provider indicating that gender transition is medically necessary will be provided medical care and treatment for the diagnosed medical condition, in the same manner as other medical care and treatment.”

For the new study, Dr. Schvey and her associates surveyed 204 of the approximately 1,700 family physicians who serve the military (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0136). The survey respondents had all attended an annual meeting in March 2016.

Most respondents were male (62.8%) and white (85.5%); 21.7% were residents. The highest number of respondents (42.6%) worked for the U.S. Air Force.

Almost three-quarters of the respondents said that they had received no training or medical education in gender dysphoria, and 62.7% said they had never treated a transgender patient as a physician.

Just under half (47.1%) of respondents – 82 – said they would prescribe cross-hormone therapy to eligible adult patients, but only one would do so independently. The others would only do so with additional education (7.5% of all responding physicians), the help of an experienced clinician (17.2%), or both (21.8%).

The other 52.9% said they wouldn’t prescribe the hormone therapy. Eight percent of all responding physicians blamed ethical concerns, 19.5% pointed to lack of comfort, and 25.3% mentioned both, the investigators reported.

Why are so many physicians so uncomfortable?

Dr. Schvey said the survey design doesn’t allow for speculation about what the ethical concerns might be, but “the data did indicate that hours of training on transgender care were directly associated with the likelihood of prescribing cross-hormone therapy. Therefore, some of the lack of comfort may be due to lack of experience and adequate training.”

Although family physicians are generally used to treating patients with hormones for contraception and to treat perimenopausal symptoms and hypogonadism, many don’t know about dosing regimens and other information regarding their use in transgender patients, study coauthor David A. Klein, MD, assistant professor of family medicine and pediatrics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, said in an interview. And, he noted, “some are unaware that provision of cross-hormone therapy is within their scope of care.”

Going forward, “given that greater education in transgender care is associated with increased competency,” Dr. Schvey said in an interview, “it will be important to assess the training of military physicians to ensure skill and sensitivity in treating patients who identify as transgender.”

The study had no specific funding, and the authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The U.S. military now allows transgender people to serve openly, and all medical personnel are supposed to be trained in their treatment – including care related to gender transition – by June 2017.

But a new survey of 204 family physicians who work for the military shows that most aren’t willing to prescribe cross-hormone treatment to eligible adult transgender patients.

In addition, “we found that most military clinicians did not receive any formal training on transgender care during their medical education, most had not treated a patient with gender dysphoria, and most had not received sufficient training to prescribe cross-hormone therapy,” said Natasha A. Schvey, PhD, an assistant professor with the medical and clinical psychology department at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and lead author of a new study that summarizes the survey findings.

An estimated 12,800 transgender people serve in the U.S. military, and researchers believe that they make up a larger proportion of the military population than in the general population.

In October 2016, the Department of Defense ended its ban on service by transgender troops. A policy statement says: “Service members with a diagnosis from a military medical provider indicating that gender transition is medically necessary will be provided medical care and treatment for the diagnosed medical condition, in the same manner as other medical care and treatment.”

For the new study, Dr. Schvey and her associates surveyed 204 of the approximately 1,700 family physicians who serve the military (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0136). The survey respondents had all attended an annual meeting in March 2016.

Most respondents were male (62.8%) and white (85.5%); 21.7% were residents. The highest number of respondents (42.6%) worked for the U.S. Air Force.

Almost three-quarters of the respondents said that they had received no training or medical education in gender dysphoria, and 62.7% said they had never treated a transgender patient as a physician.

Just under half (47.1%) of respondents – 82 – said they would prescribe cross-hormone therapy to eligible adult patients, but only one would do so independently. The others would only do so with additional education (7.5% of all responding physicians), the help of an experienced clinician (17.2%), or both (21.8%).

The other 52.9% said they wouldn’t prescribe the hormone therapy. Eight percent of all responding physicians blamed ethical concerns, 19.5% pointed to lack of comfort, and 25.3% mentioned both, the investigators reported.

Why are so many physicians so uncomfortable?

Dr. Schvey said the survey design doesn’t allow for speculation about what the ethical concerns might be, but “the data did indicate that hours of training on transgender care were directly associated with the likelihood of prescribing cross-hormone therapy. Therefore, some of the lack of comfort may be due to lack of experience and adequate training.”

Although family physicians are generally used to treating patients with hormones for contraception and to treat perimenopausal symptoms and hypogonadism, many don’t know about dosing regimens and other information regarding their use in transgender patients, study coauthor David A. Klein, MD, assistant professor of family medicine and pediatrics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, said in an interview. And, he noted, “some are unaware that provision of cross-hormone therapy is within their scope of care.”

Going forward, “given that greater education in transgender care is associated with increased competency,” Dr. Schvey said in an interview, “it will be important to assess the training of military physicians to ensure skill and sensitivity in treating patients who identify as transgender.”

The study had no specific funding, and the authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

AKI seen in 64% of children hospitalized with diabetic ketoacidosis

A high proportion of children with type 1 diabetes who are hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) develop acute kidney injury (AKI), according to results from a study.

Researchers reviewing records from a Canadian hospital found that in a cohort of 165 children hospitalized for DKA during a 5-year period (2008-2013), 64% developed the complication. Severe forms of AKI (stage 2 or 3) were common, representing 45% and 20%, respectively, of children with AKI. Two patients in the cohort required dialysis.

“We hypothesized that, because DKA is associated with both volume depletion and conservative fluid administration upon presentation, these children are potentially at high risk for AKI, above the level of risk expected by the rare reported cases in the literature,” Dr. Hursh and his colleagues wrote (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0020).

The investigators found that lower serum bicarbonate levels and elevated heart rates were indeed associated with increased risk of severe AKI. Serum bicarbonate level of less than 10 mEq/L was associated with a fivefold increase in the odds of severe (stage 2 or 3) AKI (adjusted odds ratio, 5.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.35-20.22). Each increase of 5 bpm in initial heart rate was associated with a 22% increase in the odds of severe AKI (aOR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.07-1.39).

Dr. Hursh and his colleagues defined AKI using serum creatinine values. As baseline values prior to hospital admission were not available, the researchers used estimated normal value ranges from published studies, choosing a glomerular filtration rate of 120 mL/min per 1.73 m2 as a standard baseline value. Urine output was not used as a measure because of inconsistent records.

Of particular concern was that more than 40% of patients with AKI “did not have documented resolution of AKI prior to discharge or arrangements for follow-up in the nephrology clinic. Of note, the final AKI stage was severe for 50% of these children,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

The findings suggest that clinicians “should consider AKI as a frequent complication that accompanies pediatric DKA and should be especially alert to its presence in severe presentations of DKA,” they said. AKI is underrecognized “both because of a lack of awareness of AKI as a complication of DKA and because the serum creatinine level in pediatric patients must be interpreted in the context of the child’s age and height. It is crucial to develop or have in place systems that identify and monitor abnormal markers of renal function in this population.”

The researchers acknowledged as limitations of their study its retrospective design, the absence of baseline serum creatinine values, and the lack of urine output data for use in AKI severity grading. And prospective longitudinal studies, they wrote, “are needed to assess the effect of these AKI episodes on the trajectory of renal disease in children with diabetes.”

The researchers reported no outside funding or relevant financial disclosures.

With the lack of targeted therapies to prevent AKI or decrease its associated consequences, supportive care is the mainstay of treatment and focuses on fluid and electrolyte management, nutrition, prevention of further injury through close attention to medication dosing, and, when needed, renal replacement therapy. At first glance, these findings may not appear to be overly surprising or significant; children with volume depletion have decreased renal blood flow, leading to AKI, which corrects with fluid administration. However, the authors appropriately suggest that this issue is not a simple one and that fluid management should be carefully considered in these patients. Because of severe hyperglycemia and derangements in serum sodium concentration, children with DKA are at risk of potentially catastrophic cerebral edema, leading to recommendations for cautious administration of fluids in this high-risk population.

These findings may lead clinicians and investigators to question established practices related to aggressive fluid administration in the sickest children. While awaiting more research to determine the sweet spot for fluid management in children with AKI, it seems reasonable to give fluids to patients with AKI secondary to volume depletion while quickly shifting to more restrictive strategies in those who do not respond to volume and have decreasing urine output. This may be especially important for children with DKA, as conservative fluid management may decrease central nervous system complications.

We commend the authors for exploring AKI in a novel pediatric population, expanding our knowledge on whom kidney function should be more diligently examined, providing insights on relevant fluid strategies, and increasing awareness for a group of patients who may benefit from closer long-term nephrology follow-up.

Benjamin L. Laskin, MD , is at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Jens Goebel, MD , is at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. Dr. Laskin’s and Dr. Goebel’s comments are excerpted from an editorial accompanying the study by Hursh et al. (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0009). Dr Laskin is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. The editorialists had no other relevant financial disclosures.

With the lack of targeted therapies to prevent AKI or decrease its associated consequences, supportive care is the mainstay of treatment and focuses on fluid and electrolyte management, nutrition, prevention of further injury through close attention to medication dosing, and, when needed, renal replacement therapy. At first glance, these findings may not appear to be overly surprising or significant; children with volume depletion have decreased renal blood flow, leading to AKI, which corrects with fluid administration. However, the authors appropriately suggest that this issue is not a simple one and that fluid management should be carefully considered in these patients. Because of severe hyperglycemia and derangements in serum sodium concentration, children with DKA are at risk of potentially catastrophic cerebral edema, leading to recommendations for cautious administration of fluids in this high-risk population.

These findings may lead clinicians and investigators to question established practices related to aggressive fluid administration in the sickest children. While awaiting more research to determine the sweet spot for fluid management in children with AKI, it seems reasonable to give fluids to patients with AKI secondary to volume depletion while quickly shifting to more restrictive strategies in those who do not respond to volume and have decreasing urine output. This may be especially important for children with DKA, as conservative fluid management may decrease central nervous system complications.

We commend the authors for exploring AKI in a novel pediatric population, expanding our knowledge on whom kidney function should be more diligently examined, providing insights on relevant fluid strategies, and increasing awareness for a group of patients who may benefit from closer long-term nephrology follow-up.

Benjamin L. Laskin, MD , is at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Jens Goebel, MD , is at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. Dr. Laskin’s and Dr. Goebel’s comments are excerpted from an editorial accompanying the study by Hursh et al. (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0009). Dr Laskin is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. The editorialists had no other relevant financial disclosures.

With the lack of targeted therapies to prevent AKI or decrease its associated consequences, supportive care is the mainstay of treatment and focuses on fluid and electrolyte management, nutrition, prevention of further injury through close attention to medication dosing, and, when needed, renal replacement therapy. At first glance, these findings may not appear to be overly surprising or significant; children with volume depletion have decreased renal blood flow, leading to AKI, which corrects with fluid administration. However, the authors appropriately suggest that this issue is not a simple one and that fluid management should be carefully considered in these patients. Because of severe hyperglycemia and derangements in serum sodium concentration, children with DKA are at risk of potentially catastrophic cerebral edema, leading to recommendations for cautious administration of fluids in this high-risk population.

These findings may lead clinicians and investigators to question established practices related to aggressive fluid administration in the sickest children. While awaiting more research to determine the sweet spot for fluid management in children with AKI, it seems reasonable to give fluids to patients with AKI secondary to volume depletion while quickly shifting to more restrictive strategies in those who do not respond to volume and have decreasing urine output. This may be especially important for children with DKA, as conservative fluid management may decrease central nervous system complications.

We commend the authors for exploring AKI in a novel pediatric population, expanding our knowledge on whom kidney function should be more diligently examined, providing insights on relevant fluid strategies, and increasing awareness for a group of patients who may benefit from closer long-term nephrology follow-up.

Benjamin L. Laskin, MD , is at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Jens Goebel, MD , is at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora. Dr. Laskin’s and Dr. Goebel’s comments are excerpted from an editorial accompanying the study by Hursh et al. (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0009). Dr Laskin is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. The editorialists had no other relevant financial disclosures.

A high proportion of children with type 1 diabetes who are hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) develop acute kidney injury (AKI), according to results from a study.

Researchers reviewing records from a Canadian hospital found that in a cohort of 165 children hospitalized for DKA during a 5-year period (2008-2013), 64% developed the complication. Severe forms of AKI (stage 2 or 3) were common, representing 45% and 20%, respectively, of children with AKI. Two patients in the cohort required dialysis.

“We hypothesized that, because DKA is associated with both volume depletion and conservative fluid administration upon presentation, these children are potentially at high risk for AKI, above the level of risk expected by the rare reported cases in the literature,” Dr. Hursh and his colleagues wrote (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0020).

The investigators found that lower serum bicarbonate levels and elevated heart rates were indeed associated with increased risk of severe AKI. Serum bicarbonate level of less than 10 mEq/L was associated with a fivefold increase in the odds of severe (stage 2 or 3) AKI (adjusted odds ratio, 5.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.35-20.22). Each increase of 5 bpm in initial heart rate was associated with a 22% increase in the odds of severe AKI (aOR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.07-1.39).

Dr. Hursh and his colleagues defined AKI using serum creatinine values. As baseline values prior to hospital admission were not available, the researchers used estimated normal value ranges from published studies, choosing a glomerular filtration rate of 120 mL/min per 1.73 m2 as a standard baseline value. Urine output was not used as a measure because of inconsistent records.

Of particular concern was that more than 40% of patients with AKI “did not have documented resolution of AKI prior to discharge or arrangements for follow-up in the nephrology clinic. Of note, the final AKI stage was severe for 50% of these children,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

The findings suggest that clinicians “should consider AKI as a frequent complication that accompanies pediatric DKA and should be especially alert to its presence in severe presentations of DKA,” they said. AKI is underrecognized “both because of a lack of awareness of AKI as a complication of DKA and because the serum creatinine level in pediatric patients must be interpreted in the context of the child’s age and height. It is crucial to develop or have in place systems that identify and monitor abnormal markers of renal function in this population.”

The researchers acknowledged as limitations of their study its retrospective design, the absence of baseline serum creatinine values, and the lack of urine output data for use in AKI severity grading. And prospective longitudinal studies, they wrote, “are needed to assess the effect of these AKI episodes on the trajectory of renal disease in children with diabetes.”

The researchers reported no outside funding or relevant financial disclosures.

A high proportion of children with type 1 diabetes who are hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) develop acute kidney injury (AKI), according to results from a study.

Researchers reviewing records from a Canadian hospital found that in a cohort of 165 children hospitalized for DKA during a 5-year period (2008-2013), 64% developed the complication. Severe forms of AKI (stage 2 or 3) were common, representing 45% and 20%, respectively, of children with AKI. Two patients in the cohort required dialysis.

“We hypothesized that, because DKA is associated with both volume depletion and conservative fluid administration upon presentation, these children are potentially at high risk for AKI, above the level of risk expected by the rare reported cases in the literature,” Dr. Hursh and his colleagues wrote (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0020).

The investigators found that lower serum bicarbonate levels and elevated heart rates were indeed associated with increased risk of severe AKI. Serum bicarbonate level of less than 10 mEq/L was associated with a fivefold increase in the odds of severe (stage 2 or 3) AKI (adjusted odds ratio, 5.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.35-20.22). Each increase of 5 bpm in initial heart rate was associated with a 22% increase in the odds of severe AKI (aOR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.07-1.39).

Dr. Hursh and his colleagues defined AKI using serum creatinine values. As baseline values prior to hospital admission were not available, the researchers used estimated normal value ranges from published studies, choosing a glomerular filtration rate of 120 mL/min per 1.73 m2 as a standard baseline value. Urine output was not used as a measure because of inconsistent records.

Of particular concern was that more than 40% of patients with AKI “did not have documented resolution of AKI prior to discharge or arrangements for follow-up in the nephrology clinic. Of note, the final AKI stage was severe for 50% of these children,” the researchers wrote in their analysis.

The findings suggest that clinicians “should consider AKI as a frequent complication that accompanies pediatric DKA and should be especially alert to its presence in severe presentations of DKA,” they said. AKI is underrecognized “both because of a lack of awareness of AKI as a complication of DKA and because the serum creatinine level in pediatric patients must be interpreted in the context of the child’s age and height. It is crucial to develop or have in place systems that identify and monitor abnormal markers of renal function in this population.”

The researchers acknowledged as limitations of their study its retrospective design, the absence of baseline serum creatinine values, and the lack of urine output data for use in AKI severity grading. And prospective longitudinal studies, they wrote, “are needed to assess the effect of these AKI episodes on the trajectory of renal disease in children with diabetes.”

The researchers reported no outside funding or relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Acute kidney injury may occur in up to two-thirds of children hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis.

Major finding: In a cohort of 165 children hospitalized with DKA, 64% developed AKI. Of these, 45% had stage 2 AKI and 20% had stage 3.

Data source: A retrospective single-site cohort study of records from 165 children with DKA hospitalized from 2008 to 2013.

Disclosures: The researchers disclosed no outside funding or relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Registration is now open for CHEST Board Review 2017

Looking for in-person board review prep? Join us in Orlando, August 18 to 27, for the best live review of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine.

Register by March 31 and save $100. Registration can be done at http://boardreview.chestnet.org.

Looking for in-person board review prep? Join us in Orlando, August 18 to 27, for the best live review of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine.

Register by March 31 and save $100. Registration can be done at http://boardreview.chestnet.org.

Looking for in-person board review prep? Join us in Orlando, August 18 to 27, for the best live review of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine.

Register by March 31 and save $100. Registration can be done at http://boardreview.chestnet.org.

Replacement factors, bypassing agents safely manage fitusiran bleed events

Fitusiran appears to promote hemostasis and reduce the frequency of bleeding in patients with hemophilia. In a phase I trial of the investigational agent, breakthrough bleeds were treated effectively and safely with replacement factor or bypassing agent.

Bleed events were rare among patients achieving target antithrombin lowering of greater than 75% on fitusiran. Those that did occur were treated with factor concentrates, including recombinant Factor VIII or recombinant Factor IX, or with bypassing agents, including recombinant Factor VIIa or activated prothrombin complex–concentrates, Savita Rangarajan, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

The study included 41 patients with hemophilia A or B – 25 patients with inhibitors and 16 without inhibitors – who received either 50 mg or 80 mg of fitusiran. Early multiple ascending dose–cohorts received weekly subcutaneous dosing, and later cohorts received monthly dosing. All patients tolerated treatment well, with no serious adverse events related to the study drug. No thromboembolic events occurred, and the majority of adverse events were mild or moderate in severity, she noted.

Among patients with inhibitors, eight bleeds occurred in five patients with hemophilia A who were treated with Factor VIII, and three bleeds occurred in two patients with hemophilia B who were treated with Factor IX. Among those without inhibitors, six bleeds occurred in three patients treated with activated prothrombin complex–concentrates, and four occurred in three patients treated with recombinant Factor VIIa, said Dr. Rangarajan of Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Basingstoke, England.

The ranges of factor replacement used per injection were 7-32 IU/kg of Factor VIII and 7-43 IU/kg of Factor IX.

The ranges of bypassing agents used per injection were 14-75 U/kg of activated prothrombin complex–concentrates (mean, 2.2 administrations per bleed) and 93-133 μg/kg of recombinant Factor VIIa (mean, 1.5 administrations per bleed), she said.

Doses of the factor concentrates and bypassing agents used were at or below those recommended by the World Federation of Hemophilia.

This phase I study of fitusiran, which targets and lowers antithrombin to improve thrombin generation and promote hemostasis in patients with hemophilia, is being conducted in four parts: Part A with healthy volunteers, parts B and C with patients with moderate to severe hemophilia A or B, and part D with patients with hemophilia A or B with inhibitors.

Findings from the current exploratory analysis of the data are encouraging as they demonstrate good treatment effect in the absence of identified safety concerns, Dr. Rangarajan said, noting that fitusiran should advance to pivotal studies in 2017 and that data on bleed management from a phase I and phase II open label extension will guide protocol on bleed management in phase III.

Dr. Rangarajan has received grant or research support from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, BioMarin Pharmaceutical, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Shire.

Fitusiran appears to promote hemostasis and reduce the frequency of bleeding in patients with hemophilia. In a phase I trial of the investigational agent, breakthrough bleeds were treated effectively and safely with replacement factor or bypassing agent.

Bleed events were rare among patients achieving target antithrombin lowering of greater than 75% on fitusiran. Those that did occur were treated with factor concentrates, including recombinant Factor VIII or recombinant Factor IX, or with bypassing agents, including recombinant Factor VIIa or activated prothrombin complex–concentrates, Savita Rangarajan, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

The study included 41 patients with hemophilia A or B – 25 patients with inhibitors and 16 without inhibitors – who received either 50 mg or 80 mg of fitusiran. Early multiple ascending dose–cohorts received weekly subcutaneous dosing, and later cohorts received monthly dosing. All patients tolerated treatment well, with no serious adverse events related to the study drug. No thromboembolic events occurred, and the majority of adverse events were mild or moderate in severity, she noted.

Among patients with inhibitors, eight bleeds occurred in five patients with hemophilia A who were treated with Factor VIII, and three bleeds occurred in two patients with hemophilia B who were treated with Factor IX. Among those without inhibitors, six bleeds occurred in three patients treated with activated prothrombin complex–concentrates, and four occurred in three patients treated with recombinant Factor VIIa, said Dr. Rangarajan of Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Basingstoke, England.

The ranges of factor replacement used per injection were 7-32 IU/kg of Factor VIII and 7-43 IU/kg of Factor IX.

The ranges of bypassing agents used per injection were 14-75 U/kg of activated prothrombin complex–concentrates (mean, 2.2 administrations per bleed) and 93-133 μg/kg of recombinant Factor VIIa (mean, 1.5 administrations per bleed), she said.

Doses of the factor concentrates and bypassing agents used were at or below those recommended by the World Federation of Hemophilia.

This phase I study of fitusiran, which targets and lowers antithrombin to improve thrombin generation and promote hemostasis in patients with hemophilia, is being conducted in four parts: Part A with healthy volunteers, parts B and C with patients with moderate to severe hemophilia A or B, and part D with patients with hemophilia A or B with inhibitors.

Findings from the current exploratory analysis of the data are encouraging as they demonstrate good treatment effect in the absence of identified safety concerns, Dr. Rangarajan said, noting that fitusiran should advance to pivotal studies in 2017 and that data on bleed management from a phase I and phase II open label extension will guide protocol on bleed management in phase III.

Dr. Rangarajan has received grant or research support from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, BioMarin Pharmaceutical, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Shire.

Fitusiran appears to promote hemostasis and reduce the frequency of bleeding in patients with hemophilia. In a phase I trial of the investigational agent, breakthrough bleeds were treated effectively and safely with replacement factor or bypassing agent.

Bleed events were rare among patients achieving target antithrombin lowering of greater than 75% on fitusiran. Those that did occur were treated with factor concentrates, including recombinant Factor VIII or recombinant Factor IX, or with bypassing agents, including recombinant Factor VIIa or activated prothrombin complex–concentrates, Savita Rangarajan, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

The study included 41 patients with hemophilia A or B – 25 patients with inhibitors and 16 without inhibitors – who received either 50 mg or 80 mg of fitusiran. Early multiple ascending dose–cohorts received weekly subcutaneous dosing, and later cohorts received monthly dosing. All patients tolerated treatment well, with no serious adverse events related to the study drug. No thromboembolic events occurred, and the majority of adverse events were mild or moderate in severity, she noted.

Among patients with inhibitors, eight bleeds occurred in five patients with hemophilia A who were treated with Factor VIII, and three bleeds occurred in two patients with hemophilia B who were treated with Factor IX. Among those without inhibitors, six bleeds occurred in three patients treated with activated prothrombin complex–concentrates, and four occurred in three patients treated with recombinant Factor VIIa, said Dr. Rangarajan of Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Basingstoke, England.

The ranges of factor replacement used per injection were 7-32 IU/kg of Factor VIII and 7-43 IU/kg of Factor IX.

The ranges of bypassing agents used per injection were 14-75 U/kg of activated prothrombin complex–concentrates (mean, 2.2 administrations per bleed) and 93-133 μg/kg of recombinant Factor VIIa (mean, 1.5 administrations per bleed), she said.

Doses of the factor concentrates and bypassing agents used were at or below those recommended by the World Federation of Hemophilia.

This phase I study of fitusiran, which targets and lowers antithrombin to improve thrombin generation and promote hemostasis in patients with hemophilia, is being conducted in four parts: Part A with healthy volunteers, parts B and C with patients with moderate to severe hemophilia A or B, and part D with patients with hemophilia A or B with inhibitors.

Findings from the current exploratory analysis of the data are encouraging as they demonstrate good treatment effect in the absence of identified safety concerns, Dr. Rangarajan said, noting that fitusiran should advance to pivotal studies in 2017 and that data on bleed management from a phase I and phase II open label extension will guide protocol on bleed management in phase III.

Dr. Rangarajan has received grant or research support from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, BioMarin Pharmaceutical, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Shire.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: 21 bleeds occurred in 13 patients, and all were treated effectively and safely.

Data source: An exploratory analysis of data from a four-part phase I trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Rangarajan has received grant or research support from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, BioMarin Pharmaceutical, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Shire.

VIDEO: Rucaparib benefits HGOC with BRCA mutations

National Harbor, MD. – The PARP inhibitor rucaparib is safe and effective in patients with primary platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma who have germline or somatic BRCA mutations, according to integrated summary data from parts 1 and 2 of the phase II ARIEL2 study.

Prior analyses of ARIEL2 data included 493 patients with germline/somatic BRCA mutations and BRCA wild-type. The current analysis included the 41 patients from ARIEL2 part 1 and the 93 patients from ARIEL2 part 2 who had germline or somatic BRCA mutations, and overall response rates in these patients ranged from 52% to 86% depending on the number of prior therapies, Gottfried E. Konecny, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

The highest overall response rates were seen in platinum-sensitive vs. platinum-resistant and platinum-refractory patients, said Dr. Konecny of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Median progression-free survival was 12.7 months in the platinum-sensitive patients vs. 7.3 and 5.0 months in platinum-resistant and platinum-refractory patients, respectively, he said.

Treatment was generally safe and well tolerated. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nausea, fatigue, vomiting, and anemia; the most common grade 3/4 events included anemia, increased ALT/AST, and fatigue.

Previous findings from ARIEL2 and other studies of rucaparib led to conditional approval of the drug (pending further confirmation of the data), first for patients with germline or somatic BRCA mutations who fail at least three prior lines of chemotherapy, then for those who fail two or more prior therapies.

In this video, Dr. Konecny discusses his findings and the next steps with respect to the study of rucaparib for high-grade ovarian carcinoma.

ARIEL2 was supported by Clovis Oncology. Dr. Konecny is on the speakers’ bureau for AstraZeneca and Clovis Oncology and has received research funding or honorarium from Amgen, Merck, and Novartis.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

National Harbor, MD. – The PARP inhibitor rucaparib is safe and effective in patients with primary platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma who have germline or somatic BRCA mutations, according to integrated summary data from parts 1 and 2 of the phase II ARIEL2 study.

Prior analyses of ARIEL2 data included 493 patients with germline/somatic BRCA mutations and BRCA wild-type. The current analysis included the 41 patients from ARIEL2 part 1 and the 93 patients from ARIEL2 part 2 who had germline or somatic BRCA mutations, and overall response rates in these patients ranged from 52% to 86% depending on the number of prior therapies, Gottfried E. Konecny, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

The highest overall response rates were seen in platinum-sensitive vs. platinum-resistant and platinum-refractory patients, said Dr. Konecny of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Median progression-free survival was 12.7 months in the platinum-sensitive patients vs. 7.3 and 5.0 months in platinum-resistant and platinum-refractory patients, respectively, he said.

Treatment was generally safe and well tolerated. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nausea, fatigue, vomiting, and anemia; the most common grade 3/4 events included anemia, increased ALT/AST, and fatigue.

Previous findings from ARIEL2 and other studies of rucaparib led to conditional approval of the drug (pending further confirmation of the data), first for patients with germline or somatic BRCA mutations who fail at least three prior lines of chemotherapy, then for those who fail two or more prior therapies.

In this video, Dr. Konecny discusses his findings and the next steps with respect to the study of rucaparib for high-grade ovarian carcinoma.

ARIEL2 was supported by Clovis Oncology. Dr. Konecny is on the speakers’ bureau for AstraZeneca and Clovis Oncology and has received research funding or honorarium from Amgen, Merck, and Novartis.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

National Harbor, MD. – The PARP inhibitor rucaparib is safe and effective in patients with primary platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma who have germline or somatic BRCA mutations, according to integrated summary data from parts 1 and 2 of the phase II ARIEL2 study.

Prior analyses of ARIEL2 data included 493 patients with germline/somatic BRCA mutations and BRCA wild-type. The current analysis included the 41 patients from ARIEL2 part 1 and the 93 patients from ARIEL2 part 2 who had germline or somatic BRCA mutations, and overall response rates in these patients ranged from 52% to 86% depending on the number of prior therapies, Gottfried E. Konecny, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

The highest overall response rates were seen in platinum-sensitive vs. platinum-resistant and platinum-refractory patients, said Dr. Konecny of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Median progression-free survival was 12.7 months in the platinum-sensitive patients vs. 7.3 and 5.0 months in platinum-resistant and platinum-refractory patients, respectively, he said.

Treatment was generally safe and well tolerated. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nausea, fatigue, vomiting, and anemia; the most common grade 3/4 events included anemia, increased ALT/AST, and fatigue.

Previous findings from ARIEL2 and other studies of rucaparib led to conditional approval of the drug (pending further confirmation of the data), first for patients with germline or somatic BRCA mutations who fail at least three prior lines of chemotherapy, then for those who fail two or more prior therapies.

In this video, Dr. Konecny discusses his findings and the next steps with respect to the study of rucaparib for high-grade ovarian carcinoma.

ARIEL2 was supported by Clovis Oncology. Dr. Konecny is on the speakers’ bureau for AstraZeneca and Clovis Oncology and has received research funding or honorarium from Amgen, Merck, and Novartis.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Rare Neurological Disease Special Report

Click here to download the digital edition.

Click here to download the digital edition.

Click here to download the digital edition.