User login

Robert Hauser, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Jonathan Eskenazi, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Wouter Schievink, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Bluish Gray Hyperpigmentation on the Face and Neck

The Diagnosis: Erythema Dyschromicum Perstans

Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), also referred to as ashy dermatosis, was first described by Ramirez1 in 1957 who labeled the patients los cenicientos (the ashen ones). It preferentially affects women in the second decade of life; however, patients of all ages can be affected, with reported cases occurring in children as young as 2 years of age.2 Most patients have Fitzpatrick skin type IV, mainly Amerindian, Hispanic South Asian, and Southwest Asian; however, there are cases reported worldwide.3 A genetic predisposition is proposed, as major histocompatibility complex genes associated with HLA-DR4⁎0407 are frequent in Mexican patients with ashy dermatosis and in the Amerindian population.4

The etiology of EDP is unknown. Various contributing factors have been reported including alimentary, occupational, and climatic factors,5,6 yet none have been conclusively demonstrated. High expression of CD36 (thrombospondin receptor not found in normal skin) in spinous and granular layers, CD94 (cytotoxic cell marker) in the basal cell layer and in the inflammatory dermal infiltrate,7 and focal keratinocytic expression of intercellular adhesion molecule I (CD54) in the active lesions of EDP, as well as the absence of these findings in normal skin, suggests an immunologic role in the development of the disease.8

Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents clinically with blue-gray hyperpigmented macules varying in size and shape and developing symmetrically in both sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of the face, neck, trunk, arms, and sometimes the dorsal hands (Figures 1 and 2). Notable sparing of the palms, soles, scalp, and mucous membranes occurs.

Occasionally, in the early active stage of the disease, elevated erythematous borders are noted surrounding the hyperpigmented macules. Eventually a hypopigmented halo develops after a prolonged duration of disease.9 The eruption typically is chronic and asymptomatic, though some cases may be pruritic.10

Histopathologically, the early lesions of EDP with an erythematous active border reveal lichenoid dermatitis with basal vacuolar change and occasional Civatte bodies. A mild to moderate perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate admixed with melanophages can be seen in the papillary dermis (Figure 3). In older lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate is sparse, and pigment incontinence consistent with postinflammatory pigmentation is prominent, though melanophages extending deep into the reticular dermis may aid in distinguishing EDP from other causes of postinflammatory pigment alteration.7,11

Erythema dyschromicum perstans and lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) may be indistinguishable histopathologically and may both be variants of lichen planus actinicus. Lichen planus pigmentosus often differs from EDP in that it presents with brown-black macules and patches often on the face and flexural areas. A subset of cases of LPP also may have mucous membrane involvement. The erythematous border that characterizes the active lesion of EDP is characteristically absent in LPP. In addition, pruritus often is reported with LPP. Direct immunofluorescence is not a beneficial tool in distinguishing the entities.12

Other differential diagnoses of predominantly facial hyperpigmentation include a lichenoid drug eruption; drug-induced hyperpigmentation (deposition disorder); postinflammatory hyperpigmentation following atopic dermatitis; contact dermatitis or photosensitivity reaction; early pinta; and cutaneous findings of systemic diseases manifesting with diffuse hyperpigmentation such as lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, hemochromatosis, and Addison disease. A detailed history including medication use, thorough clinical examination, and careful histopathologic evaluation will help distinguish these conditions.

Chrysiasis is a rare bluish to slate gray discoloration of the skin that predominantly occurs in sun-exposed areas. It is caused by chronic use of gold salts, which have been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. UV light may contribute to induce the uptake of gold and subsequently stimulate tyrosinase activity.13 Histologic features of chrysiasis include dermal and perivascular gold deposition within the macrophages and endothelial cells as well as extracellular granules. It demonstrates an orange-red birefringence on fluorescent microscopy.14,15

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is a well-recognized side effect of this drug. It is dose dependent and appears as a blue-black pigmentation that most frequently affects the shins, ankles, and arms.16 Three distinct types were documented: abnormal discoloration of the skin that has been linked to deposition of pigmented metabolites of minocycline producing blue-black pigmentation at the site of scarring or prior inflammation (type 1); blue-gray pigmentation affecting normal skin, mainly the legs (type 2); and elevated levels of melanin on the sun-exposed areas producing dirty skin syndrome (type 3).17,18

Topical and systemic corticosteroids, UV light therapy, oral dapsone, griseofulvin, retinoids, and clofazimine are reported as treatment options for ashy dermatosis, though results typically are disappointing.7

- Ramirez CO. Los cenicientos: problema clinica. In: Memoria del Primer Congresso Centroamericano de Dermatologica, December 5-8, 1957. San Salvador, El Salvador; 1957:122-130.

- Lee SJ, Chung KY. Erythema dyschromicum perstans in early childhood. J Dermatol. 1999;26:119-121.

- Homez-Chacin, Barroso C. On the etiopathogenic of the erythema dyschromicum perstans: possibility of a melanosis neurocutaneous. Dermatol Venez. 1996;4:149-151.

- Correa MC, Memije EV, Vargas-Alarcon G, et al. HLA-DR association with the genetic susceptibility to develop ashy dermatosis in Mexican Mestizo patients [published online November 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:617-620.

- Jablonska S. Ingestion of ammonium nitrate as a possible cause of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Dermatologica. 1975;150:287-291.

- Stevenson JR, Miura M. Erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:196-199.

- Baranda L, Torres-Alvarez B, Cortes-Franco R, et al. Involvement of cell adhesion and activation molecules in the pathogenesis of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatitis). the effect of clofazimine therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:325-329.

- Vasquez-Ochoa LA, Isaza-Guzman DM, Orozco-Mora B, et al. Immunopathologic study of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:937-941.

- Convit J, Kerdel-Vegas F, Roderiguez G. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: a hiltherto undescribed skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1961;36:457-462.

- Ono S, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Ashy dermatosis with prior pruritic and scaling skin lesions. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1103-1104.

- Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato SS, et al. Circumscribed dermal melaninoses: classification, light, histochemical, and electron microscopic studies on three patients with the erythema dyschromicum perstans type. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:25-32.

- Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:90-94.

- Ahmed SV, Sajjan R. Chrysiasis: a gold "curse!" [published online May 21, 2009]. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009.

- Fiscus V, Hankinson A, Alweis R. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.24063.

- Cox AJ, Marich KW. Gold in the dermis following gold therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:655-657.

- al-Talib RK, Wright DH, Theaker JM. Orange-red birefringence of gold particles in paraffin wax embedded sections: an aid to the diagnosis of chrysiasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:176-178.

- Meyer AJ, Nahass GT. Hyperpigmented patches on the dorsa of the feet. minocycline pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1447-1450.

- Bayne-Poorman M, Shubrook J. Bluish pigmentation of face and sclera. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:519-522.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Dyschromicum Perstans

Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), also referred to as ashy dermatosis, was first described by Ramirez1 in 1957 who labeled the patients los cenicientos (the ashen ones). It preferentially affects women in the second decade of life; however, patients of all ages can be affected, with reported cases occurring in children as young as 2 years of age.2 Most patients have Fitzpatrick skin type IV, mainly Amerindian, Hispanic South Asian, and Southwest Asian; however, there are cases reported worldwide.3 A genetic predisposition is proposed, as major histocompatibility complex genes associated with HLA-DR4⁎0407 are frequent in Mexican patients with ashy dermatosis and in the Amerindian population.4

The etiology of EDP is unknown. Various contributing factors have been reported including alimentary, occupational, and climatic factors,5,6 yet none have been conclusively demonstrated. High expression of CD36 (thrombospondin receptor not found in normal skin) in spinous and granular layers, CD94 (cytotoxic cell marker) in the basal cell layer and in the inflammatory dermal infiltrate,7 and focal keratinocytic expression of intercellular adhesion molecule I (CD54) in the active lesions of EDP, as well as the absence of these findings in normal skin, suggests an immunologic role in the development of the disease.8

Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents clinically with blue-gray hyperpigmented macules varying in size and shape and developing symmetrically in both sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of the face, neck, trunk, arms, and sometimes the dorsal hands (Figures 1 and 2). Notable sparing of the palms, soles, scalp, and mucous membranes occurs.

Occasionally, in the early active stage of the disease, elevated erythematous borders are noted surrounding the hyperpigmented macules. Eventually a hypopigmented halo develops after a prolonged duration of disease.9 The eruption typically is chronic and asymptomatic, though some cases may be pruritic.10

Histopathologically, the early lesions of EDP with an erythematous active border reveal lichenoid dermatitis with basal vacuolar change and occasional Civatte bodies. A mild to moderate perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate admixed with melanophages can be seen in the papillary dermis (Figure 3). In older lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate is sparse, and pigment incontinence consistent with postinflammatory pigmentation is prominent, though melanophages extending deep into the reticular dermis may aid in distinguishing EDP from other causes of postinflammatory pigment alteration.7,11

Erythema dyschromicum perstans and lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) may be indistinguishable histopathologically and may both be variants of lichen planus actinicus. Lichen planus pigmentosus often differs from EDP in that it presents with brown-black macules and patches often on the face and flexural areas. A subset of cases of LPP also may have mucous membrane involvement. The erythematous border that characterizes the active lesion of EDP is characteristically absent in LPP. In addition, pruritus often is reported with LPP. Direct immunofluorescence is not a beneficial tool in distinguishing the entities.12

Other differential diagnoses of predominantly facial hyperpigmentation include a lichenoid drug eruption; drug-induced hyperpigmentation (deposition disorder); postinflammatory hyperpigmentation following atopic dermatitis; contact dermatitis or photosensitivity reaction; early pinta; and cutaneous findings of systemic diseases manifesting with diffuse hyperpigmentation such as lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, hemochromatosis, and Addison disease. A detailed history including medication use, thorough clinical examination, and careful histopathologic evaluation will help distinguish these conditions.

Chrysiasis is a rare bluish to slate gray discoloration of the skin that predominantly occurs in sun-exposed areas. It is caused by chronic use of gold salts, which have been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. UV light may contribute to induce the uptake of gold and subsequently stimulate tyrosinase activity.13 Histologic features of chrysiasis include dermal and perivascular gold deposition within the macrophages and endothelial cells as well as extracellular granules. It demonstrates an orange-red birefringence on fluorescent microscopy.14,15

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is a well-recognized side effect of this drug. It is dose dependent and appears as a blue-black pigmentation that most frequently affects the shins, ankles, and arms.16 Three distinct types were documented: abnormal discoloration of the skin that has been linked to deposition of pigmented metabolites of minocycline producing blue-black pigmentation at the site of scarring or prior inflammation (type 1); blue-gray pigmentation affecting normal skin, mainly the legs (type 2); and elevated levels of melanin on the sun-exposed areas producing dirty skin syndrome (type 3).17,18

Topical and systemic corticosteroids, UV light therapy, oral dapsone, griseofulvin, retinoids, and clofazimine are reported as treatment options for ashy dermatosis, though results typically are disappointing.7

The Diagnosis: Erythema Dyschromicum Perstans

Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), also referred to as ashy dermatosis, was first described by Ramirez1 in 1957 who labeled the patients los cenicientos (the ashen ones). It preferentially affects women in the second decade of life; however, patients of all ages can be affected, with reported cases occurring in children as young as 2 years of age.2 Most patients have Fitzpatrick skin type IV, mainly Amerindian, Hispanic South Asian, and Southwest Asian; however, there are cases reported worldwide.3 A genetic predisposition is proposed, as major histocompatibility complex genes associated with HLA-DR4⁎0407 are frequent in Mexican patients with ashy dermatosis and in the Amerindian population.4

The etiology of EDP is unknown. Various contributing factors have been reported including alimentary, occupational, and climatic factors,5,6 yet none have been conclusively demonstrated. High expression of CD36 (thrombospondin receptor not found in normal skin) in spinous and granular layers, CD94 (cytotoxic cell marker) in the basal cell layer and in the inflammatory dermal infiltrate,7 and focal keratinocytic expression of intercellular adhesion molecule I (CD54) in the active lesions of EDP, as well as the absence of these findings in normal skin, suggests an immunologic role in the development of the disease.8

Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents clinically with blue-gray hyperpigmented macules varying in size and shape and developing symmetrically in both sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of the face, neck, trunk, arms, and sometimes the dorsal hands (Figures 1 and 2). Notable sparing of the palms, soles, scalp, and mucous membranes occurs.

Occasionally, in the early active stage of the disease, elevated erythematous borders are noted surrounding the hyperpigmented macules. Eventually a hypopigmented halo develops after a prolonged duration of disease.9 The eruption typically is chronic and asymptomatic, though some cases may be pruritic.10

Histopathologically, the early lesions of EDP with an erythematous active border reveal lichenoid dermatitis with basal vacuolar change and occasional Civatte bodies. A mild to moderate perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate admixed with melanophages can be seen in the papillary dermis (Figure 3). In older lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate is sparse, and pigment incontinence consistent with postinflammatory pigmentation is prominent, though melanophages extending deep into the reticular dermis may aid in distinguishing EDP from other causes of postinflammatory pigment alteration.7,11

Erythema dyschromicum perstans and lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) may be indistinguishable histopathologically and may both be variants of lichen planus actinicus. Lichen planus pigmentosus often differs from EDP in that it presents with brown-black macules and patches often on the face and flexural areas. A subset of cases of LPP also may have mucous membrane involvement. The erythematous border that characterizes the active lesion of EDP is characteristically absent in LPP. In addition, pruritus often is reported with LPP. Direct immunofluorescence is not a beneficial tool in distinguishing the entities.12

Other differential diagnoses of predominantly facial hyperpigmentation include a lichenoid drug eruption; drug-induced hyperpigmentation (deposition disorder); postinflammatory hyperpigmentation following atopic dermatitis; contact dermatitis or photosensitivity reaction; early pinta; and cutaneous findings of systemic diseases manifesting with diffuse hyperpigmentation such as lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, hemochromatosis, and Addison disease. A detailed history including medication use, thorough clinical examination, and careful histopathologic evaluation will help distinguish these conditions.

Chrysiasis is a rare bluish to slate gray discoloration of the skin that predominantly occurs in sun-exposed areas. It is caused by chronic use of gold salts, which have been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. UV light may contribute to induce the uptake of gold and subsequently stimulate tyrosinase activity.13 Histologic features of chrysiasis include dermal and perivascular gold deposition within the macrophages and endothelial cells as well as extracellular granules. It demonstrates an orange-red birefringence on fluorescent microscopy.14,15

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is a well-recognized side effect of this drug. It is dose dependent and appears as a blue-black pigmentation that most frequently affects the shins, ankles, and arms.16 Three distinct types were documented: abnormal discoloration of the skin that has been linked to deposition of pigmented metabolites of minocycline producing blue-black pigmentation at the site of scarring or prior inflammation (type 1); blue-gray pigmentation affecting normal skin, mainly the legs (type 2); and elevated levels of melanin on the sun-exposed areas producing dirty skin syndrome (type 3).17,18

Topical and systemic corticosteroids, UV light therapy, oral dapsone, griseofulvin, retinoids, and clofazimine are reported as treatment options for ashy dermatosis, though results typically are disappointing.7

- Ramirez CO. Los cenicientos: problema clinica. In: Memoria del Primer Congresso Centroamericano de Dermatologica, December 5-8, 1957. San Salvador, El Salvador; 1957:122-130.

- Lee SJ, Chung KY. Erythema dyschromicum perstans in early childhood. J Dermatol. 1999;26:119-121.

- Homez-Chacin, Barroso C. On the etiopathogenic of the erythema dyschromicum perstans: possibility of a melanosis neurocutaneous. Dermatol Venez. 1996;4:149-151.

- Correa MC, Memije EV, Vargas-Alarcon G, et al. HLA-DR association with the genetic susceptibility to develop ashy dermatosis in Mexican Mestizo patients [published online November 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:617-620.

- Jablonska S. Ingestion of ammonium nitrate as a possible cause of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Dermatologica. 1975;150:287-291.

- Stevenson JR, Miura M. Erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:196-199.

- Baranda L, Torres-Alvarez B, Cortes-Franco R, et al. Involvement of cell adhesion and activation molecules in the pathogenesis of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatitis). the effect of clofazimine therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:325-329.

- Vasquez-Ochoa LA, Isaza-Guzman DM, Orozco-Mora B, et al. Immunopathologic study of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:937-941.

- Convit J, Kerdel-Vegas F, Roderiguez G. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: a hiltherto undescribed skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1961;36:457-462.

- Ono S, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Ashy dermatosis with prior pruritic and scaling skin lesions. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1103-1104.

- Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato SS, et al. Circumscribed dermal melaninoses: classification, light, histochemical, and electron microscopic studies on three patients with the erythema dyschromicum perstans type. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:25-32.

- Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:90-94.

- Ahmed SV, Sajjan R. Chrysiasis: a gold "curse!" [published online May 21, 2009]. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009.

- Fiscus V, Hankinson A, Alweis R. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.24063.

- Cox AJ, Marich KW. Gold in the dermis following gold therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:655-657.

- al-Talib RK, Wright DH, Theaker JM. Orange-red birefringence of gold particles in paraffin wax embedded sections: an aid to the diagnosis of chrysiasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:176-178.

- Meyer AJ, Nahass GT. Hyperpigmented patches on the dorsa of the feet. minocycline pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1447-1450.

- Bayne-Poorman M, Shubrook J. Bluish pigmentation of face and sclera. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:519-522.

- Ramirez CO. Los cenicientos: problema clinica. In: Memoria del Primer Congresso Centroamericano de Dermatologica, December 5-8, 1957. San Salvador, El Salvador; 1957:122-130.

- Lee SJ, Chung KY. Erythema dyschromicum perstans in early childhood. J Dermatol. 1999;26:119-121.

- Homez-Chacin, Barroso C. On the etiopathogenic of the erythema dyschromicum perstans: possibility of a melanosis neurocutaneous. Dermatol Venez. 1996;4:149-151.

- Correa MC, Memije EV, Vargas-Alarcon G, et al. HLA-DR association with the genetic susceptibility to develop ashy dermatosis in Mexican Mestizo patients [published online November 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:617-620.

- Jablonska S. Ingestion of ammonium nitrate as a possible cause of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Dermatologica. 1975;150:287-291.

- Stevenson JR, Miura M. Erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:196-199.

- Baranda L, Torres-Alvarez B, Cortes-Franco R, et al. Involvement of cell adhesion and activation molecules in the pathogenesis of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatitis). the effect of clofazimine therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:325-329.

- Vasquez-Ochoa LA, Isaza-Guzman DM, Orozco-Mora B, et al. Immunopathologic study of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:937-941.

- Convit J, Kerdel-Vegas F, Roderiguez G. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: a hiltherto undescribed skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1961;36:457-462.

- Ono S, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Ashy dermatosis with prior pruritic and scaling skin lesions. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1103-1104.

- Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato SS, et al. Circumscribed dermal melaninoses: classification, light, histochemical, and electron microscopic studies on three patients with the erythema dyschromicum perstans type. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:25-32.

- Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:90-94.

- Ahmed SV, Sajjan R. Chrysiasis: a gold "curse!" [published online May 21, 2009]. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009.

- Fiscus V, Hankinson A, Alweis R. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.24063.

- Cox AJ, Marich KW. Gold in the dermis following gold therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:655-657.

- al-Talib RK, Wright DH, Theaker JM. Orange-red birefringence of gold particles in paraffin wax embedded sections: an aid to the diagnosis of chrysiasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:176-178.

- Meyer AJ, Nahass GT. Hyperpigmented patches on the dorsa of the feet. minocycline pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1447-1450.

- Bayne-Poorman M, Shubrook J. Bluish pigmentation of face and sclera. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:519-522.

A middle-aged woman with Fitzpatrick skin type IV was evaluated for progressive hyperpigmentation of several months' duration involving the neck, jawline, both sides of the face, and forehead. The lesions were mildly pruritic. She denied contact with any new substance and there was no history of an eruption preceding the hyperpigmentation. Medical history included chronic anemia that was managed with iron supplementation. On physical examination, blue-gray nonscaly macules and patches were observed distributed symmetrically on the neck, jawline, sides of the face, and forehead. Microscopic examination of 2 shave biopsies revealed subtle vacuolar interface dermatitis with mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and dermal melanophages (inset).

Trump administration floats 18% budget cut to HHS

The Department of Health & Human Services would see an 18% funding cut under the first budget proposal from the Trump administration.

The proposal, submitted to Congress March 16, would cut $15.1 billion from fiscal 2017 levels, funding the agency at $69 billion for fiscal year 2018. More than a third of the cuts come from the National Institutes of Health.

The NIH’s overall budget would drop to $25.9 billion in FY 2018, down $5.8 billion from this year (fiscal 2017). The proposal includes “a major reorganization of NIH’s institutes and centers to help focus resources on the highest priority research and training activities, including: eliminating the Fogarty International Center, consolidating the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality within the NIH, and other consolidations and structural changes across NIH organizations and activities,” according to summary documents from the Office of Management and Budget.

The proposed cuts also account for the funds that are to be appropriated for the 21st Century Cures Act, which was supposed to add $4.8 billion in new appropriated funding, including funds dedicated to the Cancer Moonshot and the BRAIN Initiative.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also would be reformed, getting a new $500 million block grant “to increase state flexibility and focus on the leading public health challenges specific to each state.” It also creates a new Federal Emergency Response Fund to respond to public health outbreaks such as the Zika virus.

Another area receiving a boost under the proposal is the funding for the Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control program at the CMS, which would receive $751 million in fiscal 2018, about 10% more than it did in fiscal 2017. The budget document notes that the “return on investment for the HCFAC account was $5 returned for every $1 expended from 2014-2016.”

Other cuts highlighted by the proposal include elimination of $403 million in health professions and nursing training programs, “which lack evidence that they significantly improve the nation’s health workforce,” and a $4.2 billion cut from the elimination of discretionary programs within the Office of Community Services.

The Department of Health & Human Services would see an 18% funding cut under the first budget proposal from the Trump administration.

The proposal, submitted to Congress March 16, would cut $15.1 billion from fiscal 2017 levels, funding the agency at $69 billion for fiscal year 2018. More than a third of the cuts come from the National Institutes of Health.

The NIH’s overall budget would drop to $25.9 billion in FY 2018, down $5.8 billion from this year (fiscal 2017). The proposal includes “a major reorganization of NIH’s institutes and centers to help focus resources on the highest priority research and training activities, including: eliminating the Fogarty International Center, consolidating the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality within the NIH, and other consolidations and structural changes across NIH organizations and activities,” according to summary documents from the Office of Management and Budget.

The proposed cuts also account for the funds that are to be appropriated for the 21st Century Cures Act, which was supposed to add $4.8 billion in new appropriated funding, including funds dedicated to the Cancer Moonshot and the BRAIN Initiative.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also would be reformed, getting a new $500 million block grant “to increase state flexibility and focus on the leading public health challenges specific to each state.” It also creates a new Federal Emergency Response Fund to respond to public health outbreaks such as the Zika virus.

Another area receiving a boost under the proposal is the funding for the Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control program at the CMS, which would receive $751 million in fiscal 2018, about 10% more than it did in fiscal 2017. The budget document notes that the “return on investment for the HCFAC account was $5 returned for every $1 expended from 2014-2016.”

Other cuts highlighted by the proposal include elimination of $403 million in health professions and nursing training programs, “which lack evidence that they significantly improve the nation’s health workforce,” and a $4.2 billion cut from the elimination of discretionary programs within the Office of Community Services.

The Department of Health & Human Services would see an 18% funding cut under the first budget proposal from the Trump administration.

The proposal, submitted to Congress March 16, would cut $15.1 billion from fiscal 2017 levels, funding the agency at $69 billion for fiscal year 2018. More than a third of the cuts come from the National Institutes of Health.

The NIH’s overall budget would drop to $25.9 billion in FY 2018, down $5.8 billion from this year (fiscal 2017). The proposal includes “a major reorganization of NIH’s institutes and centers to help focus resources on the highest priority research and training activities, including: eliminating the Fogarty International Center, consolidating the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality within the NIH, and other consolidations and structural changes across NIH organizations and activities,” according to summary documents from the Office of Management and Budget.

The proposed cuts also account for the funds that are to be appropriated for the 21st Century Cures Act, which was supposed to add $4.8 billion in new appropriated funding, including funds dedicated to the Cancer Moonshot and the BRAIN Initiative.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also would be reformed, getting a new $500 million block grant “to increase state flexibility and focus on the leading public health challenges specific to each state.” It also creates a new Federal Emergency Response Fund to respond to public health outbreaks such as the Zika virus.

Another area receiving a boost under the proposal is the funding for the Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control program at the CMS, which would receive $751 million in fiscal 2018, about 10% more than it did in fiscal 2017. The budget document notes that the “return on investment for the HCFAC account was $5 returned for every $1 expended from 2014-2016.”

Other cuts highlighted by the proposal include elimination of $403 million in health professions and nursing training programs, “which lack evidence that they significantly improve the nation’s health workforce,” and a $4.2 billion cut from the elimination of discretionary programs within the Office of Community Services.

HCV ‘cure’ within the VA appears likely

The number of Veterans Affairs patients with hepatitis C who have achieved a sustained virologic response to antiviral therapy has escalated so rapidly and reached such a height that the disease may well be eradicated in that health care system within a few years, according to a report in Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

The potential public health benefits are substantial, “considering that HCV infection is the most common cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer in the VA and the United States, that the benefits of SVR are long-lasting, and that HCV clearance reduces the risk of liver cancer by 76% and all-cause mortality by 50%,” said Andrew M. Moon, MD, of the division of general internal medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, and his associates.

An estimated 124,662 VA patients currently are infected, and curing them “would substantially reduce the burden of HCV within the entire country and prevent tens of thousands of deaths,” they noted.

The VA dramatically increased the number of patients who were offered treatment in recent years, because it was able to allocate nearly $700 million to offset the high costs of highly effective direct antiviral agents, which in turn made these better-tolerated drugs more widely available at clinics across the country. The VA also removed all treatment prioritization criteria, allowing all patients, not just those with severe disease, to receive highly effective direct antiviral agents. This is “in stark contrast to most health care systems, state Medicaid programs, and insurance carriers in the U.S., which still restrict access ... based on severity of liver disease,” the investigators said (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 March 8. doi: 10.1111/apt.14021).

To examine the impact of these changes, Dr. Moon and his associates performed a retrospective cohort study, analyzing the electronic medical records of all 105,369 HCV treatment regimens given to 78,947 VA patients (mean age, 56 years) during a 17-year period. They found that annual treatment rates more than doubled from 2,726 to 6,679 patients when pegylated interferon was introduced, declined for a while and then rose modestly to 4,900 patients when boceprevir and telaprevir were introduced, declined again to an all-time low of 2,609 and then rebounded to 9,180 patients when sofosbuvir and simeprevir were introduced, and finally skyrocketed to 31,028 patients when ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir were introduced.

Correspondingly, SVR rates rose from less than 25% at the beginning of the study period to a “remarkable” 90.5% at the end. The improvement in SVR rates was even more pronounced among traditionally “hard to treat” cases, such as patients with concomitant cirrhosis (from 11.0% to 87.0%), decompensated cirrhosis (from 14.6% to 85.2%), highly refractory infection (from 16.4% to 89.3%), and genotype-1 infection (from 1.3% to 91.7%). “The number of patients achieving SVR increased 21-fold from 1,313 in 2010 to an estimated 28,084 in 2015,” Dr. Moon and his associates said.

“We believe that our findings based on the VA health care system might be relevant and informative for other comprehensive health care systems,” providing proof-of-concept that similar results can be achieved if aggressive screening; affordable, tolerable treatment; and open access to all patients are implemented.

The number of Veterans Affairs patients with hepatitis C who have achieved a sustained virologic response to antiviral therapy has escalated so rapidly and reached such a height that the disease may well be eradicated in that health care system within a few years, according to a report in Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

The potential public health benefits are substantial, “considering that HCV infection is the most common cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer in the VA and the United States, that the benefits of SVR are long-lasting, and that HCV clearance reduces the risk of liver cancer by 76% and all-cause mortality by 50%,” said Andrew M. Moon, MD, of the division of general internal medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, and his associates.

An estimated 124,662 VA patients currently are infected, and curing them “would substantially reduce the burden of HCV within the entire country and prevent tens of thousands of deaths,” they noted.

The VA dramatically increased the number of patients who were offered treatment in recent years, because it was able to allocate nearly $700 million to offset the high costs of highly effective direct antiviral agents, which in turn made these better-tolerated drugs more widely available at clinics across the country. The VA also removed all treatment prioritization criteria, allowing all patients, not just those with severe disease, to receive highly effective direct antiviral agents. This is “in stark contrast to most health care systems, state Medicaid programs, and insurance carriers in the U.S., which still restrict access ... based on severity of liver disease,” the investigators said (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 March 8. doi: 10.1111/apt.14021).

To examine the impact of these changes, Dr. Moon and his associates performed a retrospective cohort study, analyzing the electronic medical records of all 105,369 HCV treatment regimens given to 78,947 VA patients (mean age, 56 years) during a 17-year period. They found that annual treatment rates more than doubled from 2,726 to 6,679 patients when pegylated interferon was introduced, declined for a while and then rose modestly to 4,900 patients when boceprevir and telaprevir were introduced, declined again to an all-time low of 2,609 and then rebounded to 9,180 patients when sofosbuvir and simeprevir were introduced, and finally skyrocketed to 31,028 patients when ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir were introduced.

Correspondingly, SVR rates rose from less than 25% at the beginning of the study period to a “remarkable” 90.5% at the end. The improvement in SVR rates was even more pronounced among traditionally “hard to treat” cases, such as patients with concomitant cirrhosis (from 11.0% to 87.0%), decompensated cirrhosis (from 14.6% to 85.2%), highly refractory infection (from 16.4% to 89.3%), and genotype-1 infection (from 1.3% to 91.7%). “The number of patients achieving SVR increased 21-fold from 1,313 in 2010 to an estimated 28,084 in 2015,” Dr. Moon and his associates said.

“We believe that our findings based on the VA health care system might be relevant and informative for other comprehensive health care systems,” providing proof-of-concept that similar results can be achieved if aggressive screening; affordable, tolerable treatment; and open access to all patients are implemented.

The number of Veterans Affairs patients with hepatitis C who have achieved a sustained virologic response to antiviral therapy has escalated so rapidly and reached such a height that the disease may well be eradicated in that health care system within a few years, according to a report in Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

The potential public health benefits are substantial, “considering that HCV infection is the most common cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer in the VA and the United States, that the benefits of SVR are long-lasting, and that HCV clearance reduces the risk of liver cancer by 76% and all-cause mortality by 50%,” said Andrew M. Moon, MD, of the division of general internal medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, and his associates.

An estimated 124,662 VA patients currently are infected, and curing them “would substantially reduce the burden of HCV within the entire country and prevent tens of thousands of deaths,” they noted.

The VA dramatically increased the number of patients who were offered treatment in recent years, because it was able to allocate nearly $700 million to offset the high costs of highly effective direct antiviral agents, which in turn made these better-tolerated drugs more widely available at clinics across the country. The VA also removed all treatment prioritization criteria, allowing all patients, not just those with severe disease, to receive highly effective direct antiviral agents. This is “in stark contrast to most health care systems, state Medicaid programs, and insurance carriers in the U.S., which still restrict access ... based on severity of liver disease,” the investigators said (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 March 8. doi: 10.1111/apt.14021).

To examine the impact of these changes, Dr. Moon and his associates performed a retrospective cohort study, analyzing the electronic medical records of all 105,369 HCV treatment regimens given to 78,947 VA patients (mean age, 56 years) during a 17-year period. They found that annual treatment rates more than doubled from 2,726 to 6,679 patients when pegylated interferon was introduced, declined for a while and then rose modestly to 4,900 patients when boceprevir and telaprevir were introduced, declined again to an all-time low of 2,609 and then rebounded to 9,180 patients when sofosbuvir and simeprevir were introduced, and finally skyrocketed to 31,028 patients when ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir were introduced.

Correspondingly, SVR rates rose from less than 25% at the beginning of the study period to a “remarkable” 90.5% at the end. The improvement in SVR rates was even more pronounced among traditionally “hard to treat” cases, such as patients with concomitant cirrhosis (from 11.0% to 87.0%), decompensated cirrhosis (from 14.6% to 85.2%), highly refractory infection (from 16.4% to 89.3%), and genotype-1 infection (from 1.3% to 91.7%). “The number of patients achieving SVR increased 21-fold from 1,313 in 2010 to an estimated 28,084 in 2015,” Dr. Moon and his associates said.

“We believe that our findings based on the VA health care system might be relevant and informative for other comprehensive health care systems,” providing proof-of-concept that similar results can be achieved if aggressive screening; affordable, tolerable treatment; and open access to all patients are implemented.

FROM ALIMENTARY PHARMACOLOGY AND THERAPEUTICS

Key clinical point: The number of VA patients with hepatitis C virus who have achieved a sustained virologic response has escalated so rapidly and so high that the disease may be eradicated in that health care system within a few years.

Major finding: SVR rates rose from less than 25% at the beginning of the study period to a “remarkable” 90.5% at the end; the number of patients achieving SVR increased 21-fold from 1,313 in 2010 to an estimated 28,084 in 2015.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study examining all 105,369 antiviral regimens administered within the VA in 1999-2016.

Disclosures: The VA Office of Research and Development funded the study. Dr. Moon and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Alan Finkel, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Lars Edvinsson, MD, PhD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Parental reasons for HPV nonvaccination are shifting

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Parents are now less concerned about whether their daughters are sexually active when weighing whether to vaccinate against human papillomavirus (HPV), compared with just a few years ago.

This shift in parental attitudes can inform physician guidance and shift the HPV vaccination discussion, Anna Beavis, MD, a clinical fellow in gynecologic oncology at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

About 90% of cervical cancer is preventable with the HPV vaccine, but “U.S. vaccination rates are still suboptimal,” putting the United States far behind many other developed countries, Dr. Beavis said.

It’s been shown that the physician recommendation is one of the strongest predictors of whether an adolescent will be immunized against HPV, yet many providers remain reluctant to raise the issue, she said. Discomfort about discussing adolescent sexuality with the teen and with parents has been cited by physicians as a primary barrier.

To evaluate why parents of adolescent girls would opt out of HPV vaccination and to identify whether the reasons had changed over time, Dr. Beavis and her colleagues formulated a study that compared parent responses to a nationwide survey about HPV vaccination given in 2014 to those in 2010.

The study drew from the National Immunization Survey–Teen, a random digit-dialing survey administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Only data pertaining to girls aged 13-17 years was included in the analysis, and for the sake of accuracy, only provider-verified responses were used.

Of the 49,345 responses that could be provider verified during the period from 2010 to 2014, 54% had received at least one HPV vaccination. Of the remaining responses, 55% of the parents said they had no intention of vaccinating their daughters.

During this period, vaccination rates have climbed slowly, from a little less than half in 2010 to about 60% in 2014 (test of trend, P less than .001), according to Dr. Beavis.

However, the reasons parents gave for declining vaccination has shifted over time, she said. The primary reason given in 2010 was concern about safety or side effects, followed by the sense that the vaccine was not necessary. These remained the top two reasons in 2014, though they had swapped places.

In 2010, the third most common reason parents gave for declining the HPV vaccination was that their daughters were not sexually active. By 2014, this reason had slid to the bottom of the top five reasons, and now was given by fewer than 10% of parents (test of trend, P less than .01).

This is important information for physicians, Dr. Beavis said in a video interview. If a physician has been reluctant to start the HPV discussion for fear of stepping into awkward territory with parents of teen girls, they should know that it’s significantly less likely that issues of sexuality will be on the parental radar when talking about HPV vaccination.

Looking deeper into the data, the investigators found that white race, younger patient age, and living above the poverty level were risk factors for nonvaccination. This means, Dr. Beavis said, that physicians should consider “developing a targeted HPV message” for families at higher risk of nonvaccination.

“This vaccine message should focus on cancer prevention, necessity, and the safety of the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Beavis said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Parents are now less concerned about whether their daughters are sexually active when weighing whether to vaccinate against human papillomavirus (HPV), compared with just a few years ago.

This shift in parental attitudes can inform physician guidance and shift the HPV vaccination discussion, Anna Beavis, MD, a clinical fellow in gynecologic oncology at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

About 90% of cervical cancer is preventable with the HPV vaccine, but “U.S. vaccination rates are still suboptimal,” putting the United States far behind many other developed countries, Dr. Beavis said.

It’s been shown that the physician recommendation is one of the strongest predictors of whether an adolescent will be immunized against HPV, yet many providers remain reluctant to raise the issue, she said. Discomfort about discussing adolescent sexuality with the teen and with parents has been cited by physicians as a primary barrier.

To evaluate why parents of adolescent girls would opt out of HPV vaccination and to identify whether the reasons had changed over time, Dr. Beavis and her colleagues formulated a study that compared parent responses to a nationwide survey about HPV vaccination given in 2014 to those in 2010.

The study drew from the National Immunization Survey–Teen, a random digit-dialing survey administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Only data pertaining to girls aged 13-17 years was included in the analysis, and for the sake of accuracy, only provider-verified responses were used.

Of the 49,345 responses that could be provider verified during the period from 2010 to 2014, 54% had received at least one HPV vaccination. Of the remaining responses, 55% of the parents said they had no intention of vaccinating their daughters.

During this period, vaccination rates have climbed slowly, from a little less than half in 2010 to about 60% in 2014 (test of trend, P less than .001), according to Dr. Beavis.

However, the reasons parents gave for declining vaccination has shifted over time, she said. The primary reason given in 2010 was concern about safety or side effects, followed by the sense that the vaccine was not necessary. These remained the top two reasons in 2014, though they had swapped places.

In 2010, the third most common reason parents gave for declining the HPV vaccination was that their daughters were not sexually active. By 2014, this reason had slid to the bottom of the top five reasons, and now was given by fewer than 10% of parents (test of trend, P less than .01).

This is important information for physicians, Dr. Beavis said in a video interview. If a physician has been reluctant to start the HPV discussion for fear of stepping into awkward territory with parents of teen girls, they should know that it’s significantly less likely that issues of sexuality will be on the parental radar when talking about HPV vaccination.

Looking deeper into the data, the investigators found that white race, younger patient age, and living above the poverty level were risk factors for nonvaccination. This means, Dr. Beavis said, that physicians should consider “developing a targeted HPV message” for families at higher risk of nonvaccination.

“This vaccine message should focus on cancer prevention, necessity, and the safety of the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Beavis said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Parents are now less concerned about whether their daughters are sexually active when weighing whether to vaccinate against human papillomavirus (HPV), compared with just a few years ago.

This shift in parental attitudes can inform physician guidance and shift the HPV vaccination discussion, Anna Beavis, MD, a clinical fellow in gynecologic oncology at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

About 90% of cervical cancer is preventable with the HPV vaccine, but “U.S. vaccination rates are still suboptimal,” putting the United States far behind many other developed countries, Dr. Beavis said.

It’s been shown that the physician recommendation is one of the strongest predictors of whether an adolescent will be immunized against HPV, yet many providers remain reluctant to raise the issue, she said. Discomfort about discussing adolescent sexuality with the teen and with parents has been cited by physicians as a primary barrier.

To evaluate why parents of adolescent girls would opt out of HPV vaccination and to identify whether the reasons had changed over time, Dr. Beavis and her colleagues formulated a study that compared parent responses to a nationwide survey about HPV vaccination given in 2014 to those in 2010.

The study drew from the National Immunization Survey–Teen, a random digit-dialing survey administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Only data pertaining to girls aged 13-17 years was included in the analysis, and for the sake of accuracy, only provider-verified responses were used.

Of the 49,345 responses that could be provider verified during the period from 2010 to 2014, 54% had received at least one HPV vaccination. Of the remaining responses, 55% of the parents said they had no intention of vaccinating their daughters.

During this period, vaccination rates have climbed slowly, from a little less than half in 2010 to about 60% in 2014 (test of trend, P less than .001), according to Dr. Beavis.

However, the reasons parents gave for declining vaccination has shifted over time, she said. The primary reason given in 2010 was concern about safety or side effects, followed by the sense that the vaccine was not necessary. These remained the top two reasons in 2014, though they had swapped places.

In 2010, the third most common reason parents gave for declining the HPV vaccination was that their daughters were not sexually active. By 2014, this reason had slid to the bottom of the top five reasons, and now was given by fewer than 10% of parents (test of trend, P less than .01).

This is important information for physicians, Dr. Beavis said in a video interview. If a physician has been reluctant to start the HPV discussion for fear of stepping into awkward territory with parents of teen girls, they should know that it’s significantly less likely that issues of sexuality will be on the parental radar when talking about HPV vaccination.

Looking deeper into the data, the investigators found that white race, younger patient age, and living above the poverty level were risk factors for nonvaccination. This means, Dr. Beavis said, that physicians should consider “developing a targeted HPV message” for families at higher risk of nonvaccination.

“This vaccine message should focus on cancer prevention, necessity, and the safety of the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Beavis said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING ON WOMEN’S CANCER

Postoperative Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was hospitalized for heart disease resulting in an aortic valve replacement and multiple-vessel bypass grafting. He experienced a stormy septic postoperative course during which he developed numerous palpable purplish plaques (Figure 1). The lesions were bilateral and more heavily involved the lower legs and buttocks. The head and neck remained free of skin lesions. Additionally, the patient reported a bilateral burning sensation from the knees to the feet.

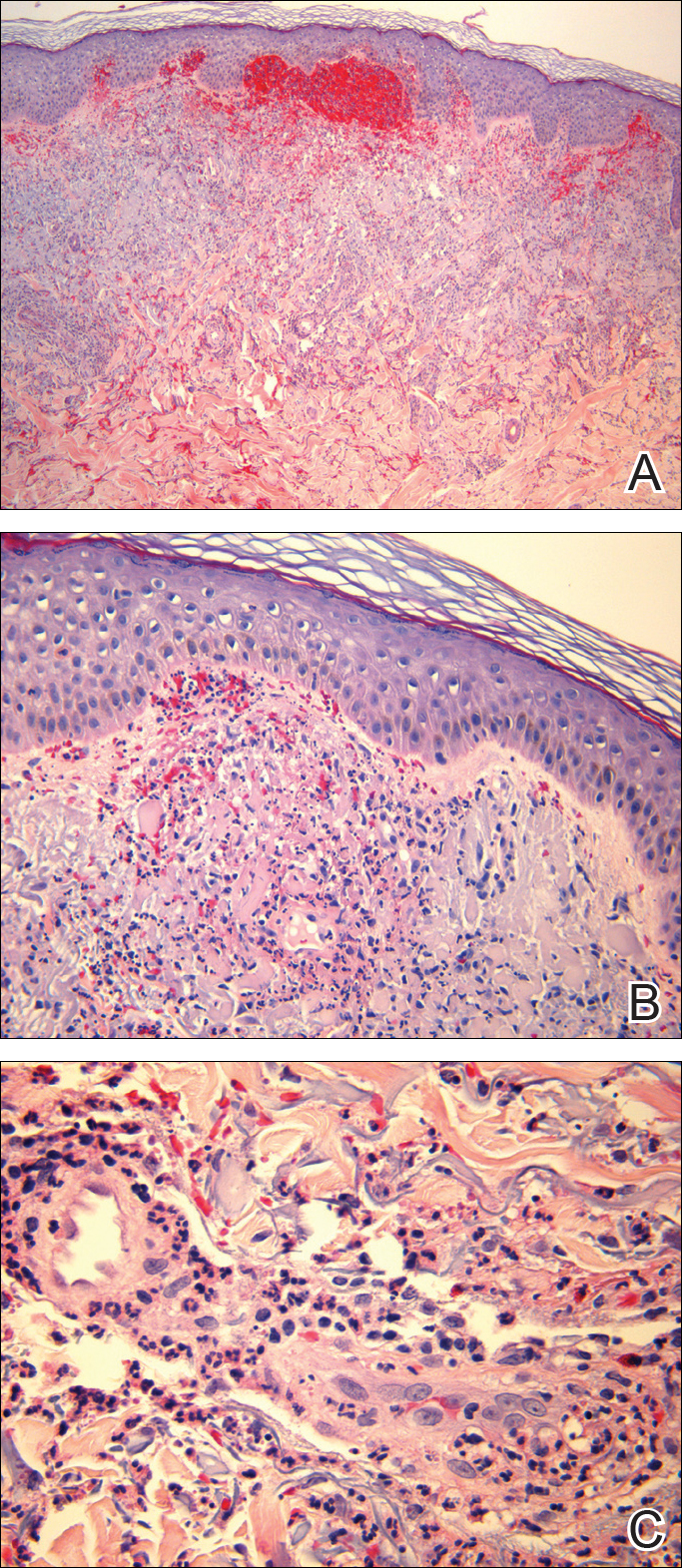

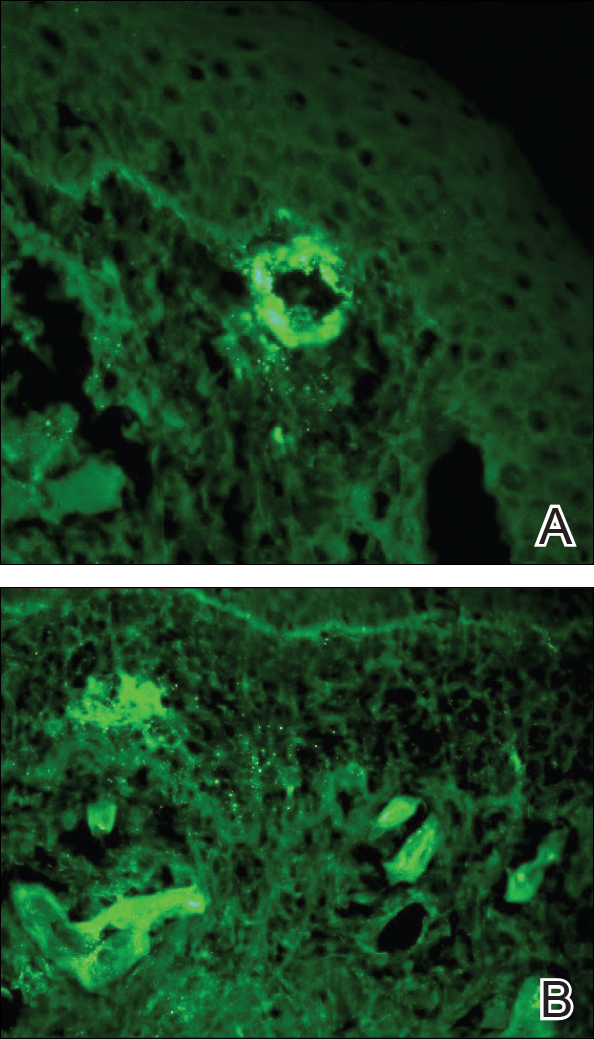

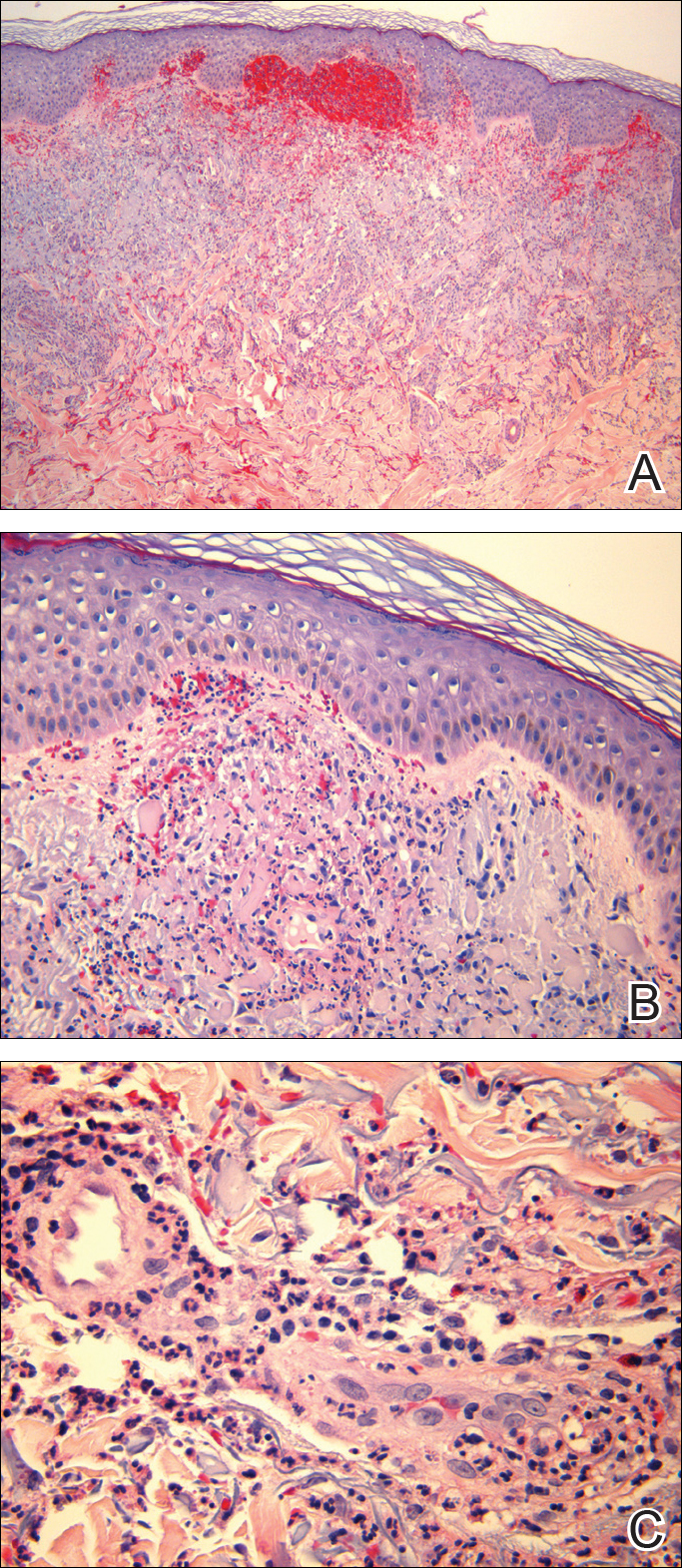

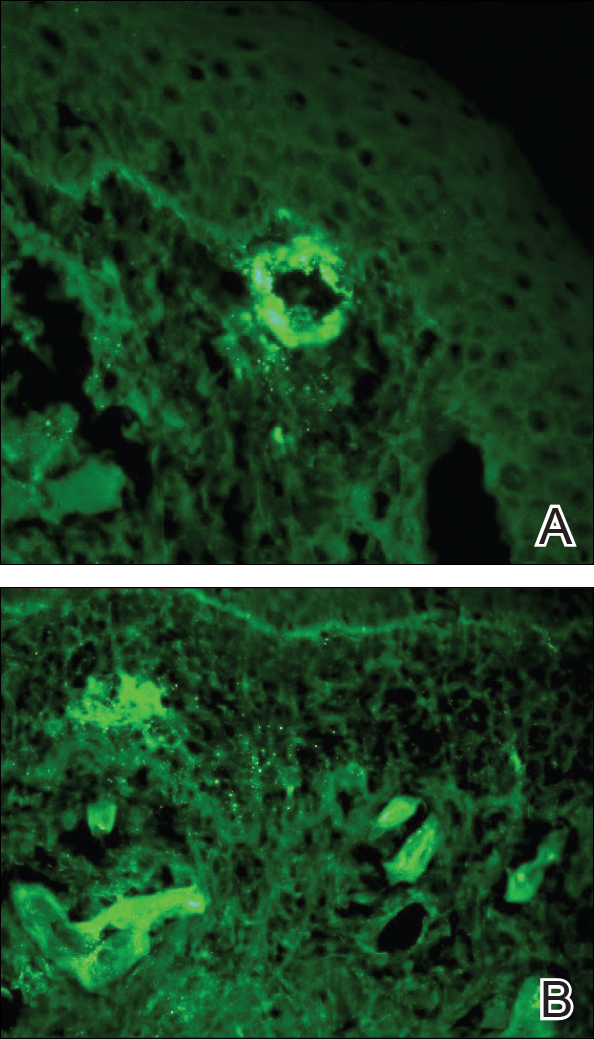

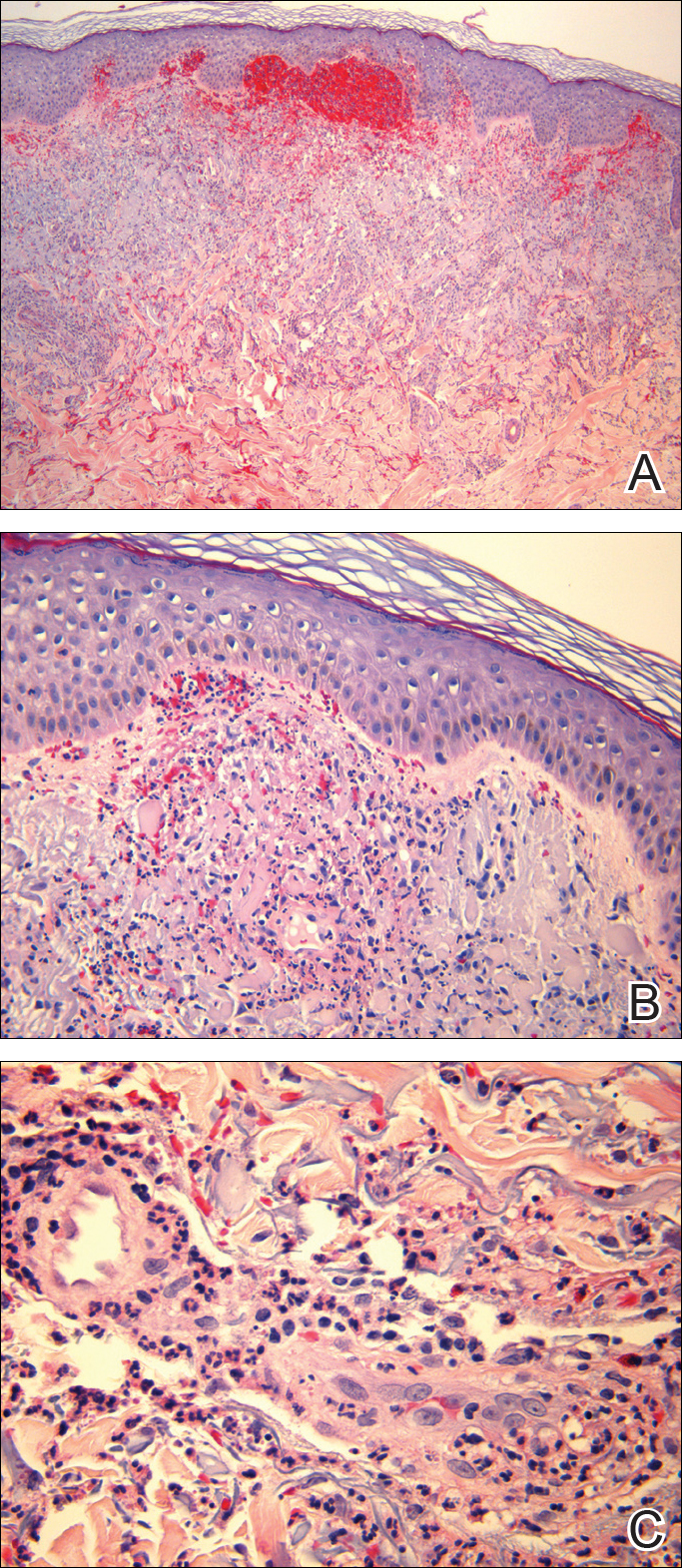

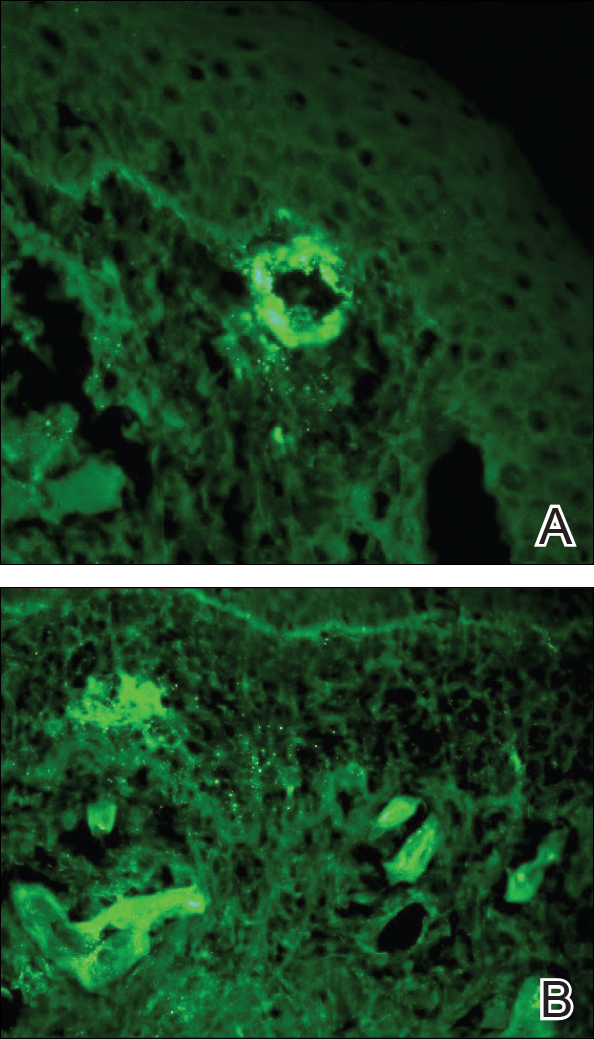

Punch biopsies of lesions from the right upper arm were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed neutrophilic-predominant small vessel vasculitis (Figure 2A) with the upper dermal location more heavily involved, as demonstrated by involvement of a superficial vascular plexus (Figures 2B and 2C) that was consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The diagnosis later was confirmed with immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA deposition around the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3). No IgG, IgM, C3, C5b-9 complement complex, or fibrinogen deposition was seen. Additionally, periodic acid-Schiff staining failed to show microorganisms, thrombi, or intravascular hyaline material.

At our initial consultation, we observed an ill-appearing afebrile man with purplish plaques. Our impression was that he had vasculitis and not warfarin necrosis, which had been suspected by the cardiovascular team. The burning sensation noted by the patient lent credence to our vasculitic diagnosis. Proteinuria and hematuria were present; however, the values for blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate all remained within reference range. His signs and symptoms responded dramatically to prednisone. He remains on 1 mg of prednisone daily and a nephrologist continues to monitor renal function as an outpatient.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving small vessels. The small vessel vasculitis is associated with IgA antigen-antibody complex deposition in areas throughout the body. Palpable purpura typically is seen on the skin, which characteristically involves dependent areas such as the legs and the buttocks. Lesions normally are present bilaterally in a symmetric distribution. Initially, the lesions develop as erythematous macules that progress to purple, nonblanching, palpable, and purpuric plaques.1 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly involves the skin; however, other locations for the immune complexes include the gastrointestinal tract, joints, and kidneys.2 The cause for the body's immunogenic deposition response is unknown in a majority of cases.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly is seen in the pediatric population with a predilection for males.3 The incidence in the pediatric population is 13.5 to 20 per 100,000 children per year; HSP is more rare in adults.4-6 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often is a self-limiting disease that requires only supportive treatment. The signs and symptoms last 4 to 6 weeks in most patients and resolve completely in 94% of children and 89% of adults.7 Renal involvement carries a worse prognosis. Adult patients have a higher incidence of renal involvement, renal insufficiency, and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3,8-10 In a study by Hung et al8 of 65 children and 22 adult HSP patients, 12 adults presented with renal involvement in which hematuria or proteinuria were present. Of them, 6 progressed to renal insufficiency (defined as having a plasma creatinine concentration>1.2 mg/dL).8 Fogazzi et al11 reported similar findings; 8 of 16 patients affected with HSP progressed to renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances ranging from 31 to 60 mL/min, and 3 patients required chronic dialysis. Pillebout et al9 evaluated 250 adults with HSP and 32% reached renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances of less than 50 mL/min, with 11% of patients developing end-stage renal disease. The degree of hematuria and/or proteinuria has been shown to be an effective prognostic indicator.9,10 Coppo et al10 found a similar prognosis among children and adults with HSP-related nephritis.

Our patient described the burning sensation as occurring bilaterally from the knees down to the feet, which provided an additional clue that small vessel vasculitis was involved, as occluded blood vessels can cause ischemia to nerves and perivascular involvement can affect nearby neural structures. Sais et al12 demonstrated that paresthesia in the setting of HSP was a risk factor for systemic involvement. Of note, our patient's paresthesia lasted only several days.

The cause of HSP is not always as evident in the adult population as in the pediatric population. Early diagnosis of HSP in adults may allow for the proper instatement of treatment to deter long-term renal complications. Follow-up with urinalysis is recommended because a small percentage of patients have a late progression to renal failure.13,14

Because the dermatologists involved in this case knew where and what types of biopsies to perform, a correct diagnosis was obtained quickly, allowing for the correct therapeutic intervention. After the diagnosis of HSP is made in an adult, nephrology should be consulted early in the treatment course.

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Helander SD, De Castro FR, Gibson LE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous vascular IgA deposits and the relationship to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:125-129.

- Garcia-Porrua C, Calvino MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149-156.

- Stewart M, Savage JM, Bell B, et al. Long term renal prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an unselected childhood population. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:113-115.

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2004;25:455-464.

- Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, et al. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360:1197-1202.

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:859-864.

- Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162-168.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.

- Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long-term prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in adults and children. Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology collaborative study on Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

- Fogazzi GB, Pasquali S, Moriggi M, et al. Long-term outcome of Schönlein-Henoch nephritis in the adult. Clin Nephrol. 1989;31:60-66.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucgla A. Prognostic factors in leukocytoclastic vasculitis. a clinicopathologic study of 160 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:309-315.

- Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:405-408.

- Narchi H. Risk of long-term renal impairment and duration of follow up recommended for Henoch-Schönlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:916-920.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was hospitalized for heart disease resulting in an aortic valve replacement and multiple-vessel bypass grafting. He experienced a stormy septic postoperative course during which he developed numerous palpable purplish plaques (Figure 1). The lesions were bilateral and more heavily involved the lower legs and buttocks. The head and neck remained free of skin lesions. Additionally, the patient reported a bilateral burning sensation from the knees to the feet.

Punch biopsies of lesions from the right upper arm were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed neutrophilic-predominant small vessel vasculitis (Figure 2A) with the upper dermal location more heavily involved, as demonstrated by involvement of a superficial vascular plexus (Figures 2B and 2C) that was consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The diagnosis later was confirmed with immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA deposition around the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3). No IgG, IgM, C3, C5b-9 complement complex, or fibrinogen deposition was seen. Additionally, periodic acid-Schiff staining failed to show microorganisms, thrombi, or intravascular hyaline material.

At our initial consultation, we observed an ill-appearing afebrile man with purplish plaques. Our impression was that he had vasculitis and not warfarin necrosis, which had been suspected by the cardiovascular team. The burning sensation noted by the patient lent credence to our vasculitic diagnosis. Proteinuria and hematuria were present; however, the values for blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate all remained within reference range. His signs and symptoms responded dramatically to prednisone. He remains on 1 mg of prednisone daily and a nephrologist continues to monitor renal function as an outpatient.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving small vessels. The small vessel vasculitis is associated with IgA antigen-antibody complex deposition in areas throughout the body. Palpable purpura typically is seen on the skin, which characteristically involves dependent areas such as the legs and the buttocks. Lesions normally are present bilaterally in a symmetric distribution. Initially, the lesions develop as erythematous macules that progress to purple, nonblanching, palpable, and purpuric plaques.1 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly involves the skin; however, other locations for the immune complexes include the gastrointestinal tract, joints, and kidneys.2 The cause for the body's immunogenic deposition response is unknown in a majority of cases.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly is seen in the pediatric population with a predilection for males.3 The incidence in the pediatric population is 13.5 to 20 per 100,000 children per year; HSP is more rare in adults.4-6 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often is a self-limiting disease that requires only supportive treatment. The signs and symptoms last 4 to 6 weeks in most patients and resolve completely in 94% of children and 89% of adults.7 Renal involvement carries a worse prognosis. Adult patients have a higher incidence of renal involvement, renal insufficiency, and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3,8-10 In a study by Hung et al8 of 65 children and 22 adult HSP patients, 12 adults presented with renal involvement in which hematuria or proteinuria were present. Of them, 6 progressed to renal insufficiency (defined as having a plasma creatinine concentration>1.2 mg/dL).8 Fogazzi et al11 reported similar findings; 8 of 16 patients affected with HSP progressed to renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances ranging from 31 to 60 mL/min, and 3 patients required chronic dialysis. Pillebout et al9 evaluated 250 adults with HSP and 32% reached renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances of less than 50 mL/min, with 11% of patients developing end-stage renal disease. The degree of hematuria and/or proteinuria has been shown to be an effective prognostic indicator.9,10 Coppo et al10 found a similar prognosis among children and adults with HSP-related nephritis.

Our patient described the burning sensation as occurring bilaterally from the knees down to the feet, which provided an additional clue that small vessel vasculitis was involved, as occluded blood vessels can cause ischemia to nerves and perivascular involvement can affect nearby neural structures. Sais et al12 demonstrated that paresthesia in the setting of HSP was a risk factor for systemic involvement. Of note, our patient's paresthesia lasted only several days.

The cause of HSP is not always as evident in the adult population as in the pediatric population. Early diagnosis of HSP in adults may allow for the proper instatement of treatment to deter long-term renal complications. Follow-up with urinalysis is recommended because a small percentage of patients have a late progression to renal failure.13,14

Because the dermatologists involved in this case knew where and what types of biopsies to perform, a correct diagnosis was obtained quickly, allowing for the correct therapeutic intervention. After the diagnosis of HSP is made in an adult, nephrology should be consulted early in the treatment course.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was hospitalized for heart disease resulting in an aortic valve replacement and multiple-vessel bypass grafting. He experienced a stormy septic postoperative course during which he developed numerous palpable purplish plaques (Figure 1). The lesions were bilateral and more heavily involved the lower legs and buttocks. The head and neck remained free of skin lesions. Additionally, the patient reported a bilateral burning sensation from the knees to the feet.

Punch biopsies of lesions from the right upper arm were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed neutrophilic-predominant small vessel vasculitis (Figure 2A) with the upper dermal location more heavily involved, as demonstrated by involvement of a superficial vascular plexus (Figures 2B and 2C) that was consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The diagnosis later was confirmed with immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA deposition around the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3). No IgG, IgM, C3, C5b-9 complement complex, or fibrinogen deposition was seen. Additionally, periodic acid-Schiff staining failed to show microorganisms, thrombi, or intravascular hyaline material.

At our initial consultation, we observed an ill-appearing afebrile man with purplish plaques. Our impression was that he had vasculitis and not warfarin necrosis, which had been suspected by the cardiovascular team. The burning sensation noted by the patient lent credence to our vasculitic diagnosis. Proteinuria and hematuria were present; however, the values for blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate all remained within reference range. His signs and symptoms responded dramatically to prednisone. He remains on 1 mg of prednisone daily and a nephrologist continues to monitor renal function as an outpatient.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving small vessels. The small vessel vasculitis is associated with IgA antigen-antibody complex deposition in areas throughout the body. Palpable purpura typically is seen on the skin, which characteristically involves dependent areas such as the legs and the buttocks. Lesions normally are present bilaterally in a symmetric distribution. Initially, the lesions develop as erythematous macules that progress to purple, nonblanching, palpable, and purpuric plaques.1 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly involves the skin; however, other locations for the immune complexes include the gastrointestinal tract, joints, and kidneys.2 The cause for the body's immunogenic deposition response is unknown in a majority of cases.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly is seen in the pediatric population with a predilection for males.3 The incidence in the pediatric population is 13.5 to 20 per 100,000 children per year; HSP is more rare in adults.4-6 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often is a self-limiting disease that requires only supportive treatment. The signs and symptoms last 4 to 6 weeks in most patients and resolve completely in 94% of children and 89% of adults.7 Renal involvement carries a worse prognosis. Adult patients have a higher incidence of renal involvement, renal insufficiency, and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3,8-10 In a study by Hung et al8 of 65 children and 22 adult HSP patients, 12 adults presented with renal involvement in which hematuria or proteinuria were present. Of them, 6 progressed to renal insufficiency (defined as having a plasma creatinine concentration>1.2 mg/dL).8 Fogazzi et al11 reported similar findings; 8 of 16 patients affected with HSP progressed to renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances ranging from 31 to 60 mL/min, and 3 patients required chronic dialysis. Pillebout et al9 evaluated 250 adults with HSP and 32% reached renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances of less than 50 mL/min, with 11% of patients developing end-stage renal disease. The degree of hematuria and/or proteinuria has been shown to be an effective prognostic indicator.9,10 Coppo et al10 found a similar prognosis among children and adults with HSP-related nephritis.

Our patient described the burning sensation as occurring bilaterally from the knees down to the feet, which provided an additional clue that small vessel vasculitis was involved, as occluded blood vessels can cause ischemia to nerves and perivascular involvement can affect nearby neural structures. Sais et al12 demonstrated that paresthesia in the setting of HSP was a risk factor for systemic involvement. Of note, our patient's paresthesia lasted only several days.

The cause of HSP is not always as evident in the adult population as in the pediatric population. Early diagnosis of HSP in adults may allow for the proper instatement of treatment to deter long-term renal complications. Follow-up with urinalysis is recommended because a small percentage of patients have a late progression to renal failure.13,14

Because the dermatologists involved in this case knew where and what types of biopsies to perform, a correct diagnosis was obtained quickly, allowing for the correct therapeutic intervention. After the diagnosis of HSP is made in an adult, nephrology should be consulted early in the treatment course.

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Helander SD, De Castro FR, Gibson LE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous vascular IgA deposits and the relationship to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:125-129.

- Garcia-Porrua C, Calvino MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149-156.

- Stewart M, Savage JM, Bell B, et al. Long term renal prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an unselected childhood population. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:113-115.

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2004;25:455-464.

- Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, et al. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360:1197-1202.

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:859-864.

- Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162-168.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.

- Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long-term prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in adults and children. Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology collaborative study on Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

- Fogazzi GB, Pasquali S, Moriggi M, et al. Long-term outcome of Schönlein-Henoch nephritis in the adult. Clin Nephrol. 1989;31:60-66.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucgla A. Prognostic factors in leukocytoclastic vasculitis. a clinicopathologic study of 160 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:309-315.

- Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:405-408.

- Narchi H. Risk of long-term renal impairment and duration of follow up recommended for Henoch-Schönlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:916-920.

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Helander SD, De Castro FR, Gibson LE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous vascular IgA deposits and the relationship to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:125-129.

- Garcia-Porrua C, Calvino MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149-156.

- Stewart M, Savage JM, Bell B, et al. Long term renal prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an unselected childhood population. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:113-115.

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2004;25:455-464.

- Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, et al. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360:1197-1202.

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:859-864.

- Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162-168.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.

- Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long-term prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in adults and children. Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology collaborative study on Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

- Fogazzi GB, Pasquali S, Moriggi M, et al. Long-term outcome of Schönlein-Henoch nephritis in the adult. Clin Nephrol. 1989;31:60-66.