User login

Study: Two antithrombotic drugs better than 3

BARCELONA—A new study suggests a combination of 2 antithrombotic drugs is as effective as, but safer than, a 3-drug combination for patients with atrial fibrillation who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

The combinations were similarly effective in preventing thromboembolic events, unplanned revascularization, or death.

But the 2-drug combination—dabigatran plus clopidogrel/ticagrelor—reduced the risk of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding when compared to the 3-drug combination—warfarin plus aspirin and clopidogrel/ticagrelor.

These results were presented at ESC Congress 2017 (abstract 1920) and published in NEJM. The trial, known as RE-DUAL PCI, was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, makers of dabigatran.

“When we treat patients who have atrial fibrillation and need a stent, we need to strike a difficult balance between risk of clotting and risk of bleeding,” said study author Christopher Cannon, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Our study finds that patients who received 2 anticlotting medications—including one of a newer class of drug—had fewer bleeding events without being more at risk for a stroke or other cardiac events.”

Patients and treatment

The RE-DUAL PCI trial included 2725 patients with atrial fibrillation who had undergone PCI. Patients were randomized to receive the 3-drug combination or the 2-drug combination. The 2-drug combination included 2 different doses of dabigatran—110 mg or 150 mg twice daily.

The researchers compared the 100-mg dual-therapy group (n=981) to the entire triple-therapy group (n=981), and they compared the 150-mg dual-therapy group (n=763) to a corresponding triple-therapy group (n=764).

The corresponding triple-therapy group only included patients who had been eligible for the 150-mg dual-therapy group, meaning this group did not include elderly patients outside the US.

Results

The primary endpoint was the first major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding event.

The incidence of this endpoint was 15.4% in the 110-mg dual-therapy group and 26.9% in the triple-therapy group (hazard ratio [HR]=0.52, P<0.001 for non-inferiority, P<0.001 for superiority).

The incidence was 20.2% in the 150-mg dual-therapy group and 25.7% in the corresponding triple-therapy group (HR=0.72, P<0.001 for non-inferiority).

A main secondary endpoint was a composite efficacy endpoint of thromboembolic events (myocardial infarction, stroke, or systemic embolism), unplanned revascularization (PCI or coronary-artery bypass grafting), or death.

The incidence of this endpoint was 15.2% in the 110-mg dual-therapy group and 13.4% in the triple-therapy group (HR=1.13, P=0.30). And it was 11.8% in the 150-mg dual-therapy group and 12.8% in the corresponding triple-therapy group (HR=0.89, P=0.44).

The incidence was 13.7% in the 2 dual-therapy groups combined and 13.4% in the triple-therapy group (HR=1.04. P=0.005 for non-inferiority).

Serious adverse events during treatment occurred in 42.7% of the patients in the 110-mg dual-therapy group, 39.6% in the 150-mg dual-therapy group, and 41.8% in the triple-therapy group.

Fatal serious adverse events occurred during treatment in 3.9%, 3.2%, and 4.3%, respectively.

“These data are very reassuring,” Dr Cannon said. “We now have new information to help select the right treatment for individual patients, which has been hard to date, and this study can help.” ![]()

BARCELONA—A new study suggests a combination of 2 antithrombotic drugs is as effective as, but safer than, a 3-drug combination for patients with atrial fibrillation who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

The combinations were similarly effective in preventing thromboembolic events, unplanned revascularization, or death.

But the 2-drug combination—dabigatran plus clopidogrel/ticagrelor—reduced the risk of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding when compared to the 3-drug combination—warfarin plus aspirin and clopidogrel/ticagrelor.

These results were presented at ESC Congress 2017 (abstract 1920) and published in NEJM. The trial, known as RE-DUAL PCI, was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, makers of dabigatran.

“When we treat patients who have atrial fibrillation and need a stent, we need to strike a difficult balance between risk of clotting and risk of bleeding,” said study author Christopher Cannon, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Our study finds that patients who received 2 anticlotting medications—including one of a newer class of drug—had fewer bleeding events without being more at risk for a stroke or other cardiac events.”

Patients and treatment

The RE-DUAL PCI trial included 2725 patients with atrial fibrillation who had undergone PCI. Patients were randomized to receive the 3-drug combination or the 2-drug combination. The 2-drug combination included 2 different doses of dabigatran—110 mg or 150 mg twice daily.

The researchers compared the 100-mg dual-therapy group (n=981) to the entire triple-therapy group (n=981), and they compared the 150-mg dual-therapy group (n=763) to a corresponding triple-therapy group (n=764).

The corresponding triple-therapy group only included patients who had been eligible for the 150-mg dual-therapy group, meaning this group did not include elderly patients outside the US.

Results

The primary endpoint was the first major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding event.

The incidence of this endpoint was 15.4% in the 110-mg dual-therapy group and 26.9% in the triple-therapy group (hazard ratio [HR]=0.52, P<0.001 for non-inferiority, P<0.001 for superiority).

The incidence was 20.2% in the 150-mg dual-therapy group and 25.7% in the corresponding triple-therapy group (HR=0.72, P<0.001 for non-inferiority).

A main secondary endpoint was a composite efficacy endpoint of thromboembolic events (myocardial infarction, stroke, or systemic embolism), unplanned revascularization (PCI or coronary-artery bypass grafting), or death.

The incidence of this endpoint was 15.2% in the 110-mg dual-therapy group and 13.4% in the triple-therapy group (HR=1.13, P=0.30). And it was 11.8% in the 150-mg dual-therapy group and 12.8% in the corresponding triple-therapy group (HR=0.89, P=0.44).

The incidence was 13.7% in the 2 dual-therapy groups combined and 13.4% in the triple-therapy group (HR=1.04. P=0.005 for non-inferiority).

Serious adverse events during treatment occurred in 42.7% of the patients in the 110-mg dual-therapy group, 39.6% in the 150-mg dual-therapy group, and 41.8% in the triple-therapy group.

Fatal serious adverse events occurred during treatment in 3.9%, 3.2%, and 4.3%, respectively.

“These data are very reassuring,” Dr Cannon said. “We now have new information to help select the right treatment for individual patients, which has been hard to date, and this study can help.” ![]()

BARCELONA—A new study suggests a combination of 2 antithrombotic drugs is as effective as, but safer than, a 3-drug combination for patients with atrial fibrillation who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

The combinations were similarly effective in preventing thromboembolic events, unplanned revascularization, or death.

But the 2-drug combination—dabigatran plus clopidogrel/ticagrelor—reduced the risk of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding when compared to the 3-drug combination—warfarin plus aspirin and clopidogrel/ticagrelor.

These results were presented at ESC Congress 2017 (abstract 1920) and published in NEJM. The trial, known as RE-DUAL PCI, was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, makers of dabigatran.

“When we treat patients who have atrial fibrillation and need a stent, we need to strike a difficult balance between risk of clotting and risk of bleeding,” said study author Christopher Cannon, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Our study finds that patients who received 2 anticlotting medications—including one of a newer class of drug—had fewer bleeding events without being more at risk for a stroke or other cardiac events.”

Patients and treatment

The RE-DUAL PCI trial included 2725 patients with atrial fibrillation who had undergone PCI. Patients were randomized to receive the 3-drug combination or the 2-drug combination. The 2-drug combination included 2 different doses of dabigatran—110 mg or 150 mg twice daily.

The researchers compared the 100-mg dual-therapy group (n=981) to the entire triple-therapy group (n=981), and they compared the 150-mg dual-therapy group (n=763) to a corresponding triple-therapy group (n=764).

The corresponding triple-therapy group only included patients who had been eligible for the 150-mg dual-therapy group, meaning this group did not include elderly patients outside the US.

Results

The primary endpoint was the first major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding event.

The incidence of this endpoint was 15.4% in the 110-mg dual-therapy group and 26.9% in the triple-therapy group (hazard ratio [HR]=0.52, P<0.001 for non-inferiority, P<0.001 for superiority).

The incidence was 20.2% in the 150-mg dual-therapy group and 25.7% in the corresponding triple-therapy group (HR=0.72, P<0.001 for non-inferiority).

A main secondary endpoint was a composite efficacy endpoint of thromboembolic events (myocardial infarction, stroke, or systemic embolism), unplanned revascularization (PCI or coronary-artery bypass grafting), or death.

The incidence of this endpoint was 15.2% in the 110-mg dual-therapy group and 13.4% in the triple-therapy group (HR=1.13, P=0.30). And it was 11.8% in the 150-mg dual-therapy group and 12.8% in the corresponding triple-therapy group (HR=0.89, P=0.44).

The incidence was 13.7% in the 2 dual-therapy groups combined and 13.4% in the triple-therapy group (HR=1.04. P=0.005 for non-inferiority).

Serious adverse events during treatment occurred in 42.7% of the patients in the 110-mg dual-therapy group, 39.6% in the 150-mg dual-therapy group, and 41.8% in the triple-therapy group.

Fatal serious adverse events occurred during treatment in 3.9%, 3.2%, and 4.3%, respectively.

“These data are very reassuring,” Dr Cannon said. “We now have new information to help select the right treatment for individual patients, which has been hard to date, and this study can help.” ![]()

CNS lymphoma responds to CAR T-cell therapy

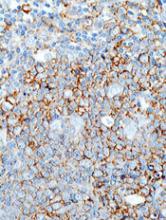

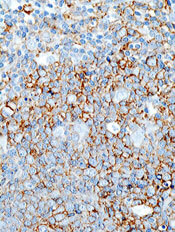

Researchers have reported the first known case of central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma responding to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The investigational CAR T-cell therapy JCAR017 induced complete remission of brain metastasis in a patient with refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

When a subcutaneous tumor began to recur 2 months after the patient received JCAR017 and a surgical biopsy was performed, the CAR T cells spontaneously re-expanded and the tumor again went into remission.

While the patient eventually relapsed and died more than a year after receiving JCAR017, the brain tumor never recurred.

“Brain involvement in DLBCL carries a grave prognosis, and the ability to induce a complete and durable response with conventional therapies is rare,” said Jeremy Abramson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“In addition, all available CAR T-cell trials have excluded patients with central nervous system involvement. This result has implications not only for secondary DLBCL like this case but also for primary central nervous system lymphoma, for which treatment options are similarly limited after relapse and few patents are cured.”

Dr Abramson and his colleagues described this case in a letter to NEJM. The patient was involved in a trial of JCAR017, which was sponsored by Juno Therapeutics.

The patient was a 68-year-old woman with germinal center B-cell-like DLBCL with a BCL2 rearrangement and multiple copies of MYC and BCL6.

The patients’ disease was refractory to conventional chemotherapy and an 8/8 HLA-matched stem cell transplant. After she enrolled in a phase 1 trial of JCAR017, the patient was found to have a new lesion in the right temporal lobe of her brain.

One month after the patient received JCAR017—given after lymphodepletion with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide—imaging showed complete remission of the brain lesion.

The subcutaneous lesion that recurred 2 months later disappeared after the biopsy with no further treatment. Blood testing showed an expansion of CAR T cells that coincided with the tumor’s regression.

While re-expansion of CAR T cells has been reported in response to other immunotherapy drugs, this is the first report of such a response to a biopsy.

“Typically, the drugs we use to fight cancer and other diseases wear off over time,” Dr Abramson said. “This spontaneous re-expansion after biopsy highlights this therapy as something entirely different, a ‘living drug’ that can re-expand and proliferate in response to biologic stimuli.” ![]()

Researchers have reported the first known case of central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma responding to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The investigational CAR T-cell therapy JCAR017 induced complete remission of brain metastasis in a patient with refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

When a subcutaneous tumor began to recur 2 months after the patient received JCAR017 and a surgical biopsy was performed, the CAR T cells spontaneously re-expanded and the tumor again went into remission.

While the patient eventually relapsed and died more than a year after receiving JCAR017, the brain tumor never recurred.

“Brain involvement in DLBCL carries a grave prognosis, and the ability to induce a complete and durable response with conventional therapies is rare,” said Jeremy Abramson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“In addition, all available CAR T-cell trials have excluded patients with central nervous system involvement. This result has implications not only for secondary DLBCL like this case but also for primary central nervous system lymphoma, for which treatment options are similarly limited after relapse and few patents are cured.”

Dr Abramson and his colleagues described this case in a letter to NEJM. The patient was involved in a trial of JCAR017, which was sponsored by Juno Therapeutics.

The patient was a 68-year-old woman with germinal center B-cell-like DLBCL with a BCL2 rearrangement and multiple copies of MYC and BCL6.

The patients’ disease was refractory to conventional chemotherapy and an 8/8 HLA-matched stem cell transplant. After she enrolled in a phase 1 trial of JCAR017, the patient was found to have a new lesion in the right temporal lobe of her brain.

One month after the patient received JCAR017—given after lymphodepletion with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide—imaging showed complete remission of the brain lesion.

The subcutaneous lesion that recurred 2 months later disappeared after the biopsy with no further treatment. Blood testing showed an expansion of CAR T cells that coincided with the tumor’s regression.

While re-expansion of CAR T cells has been reported in response to other immunotherapy drugs, this is the first report of such a response to a biopsy.

“Typically, the drugs we use to fight cancer and other diseases wear off over time,” Dr Abramson said. “This spontaneous re-expansion after biopsy highlights this therapy as something entirely different, a ‘living drug’ that can re-expand and proliferate in response to biologic stimuli.” ![]()

Researchers have reported the first known case of central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma responding to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The investigational CAR T-cell therapy JCAR017 induced complete remission of brain metastasis in a patient with refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

When a subcutaneous tumor began to recur 2 months after the patient received JCAR017 and a surgical biopsy was performed, the CAR T cells spontaneously re-expanded and the tumor again went into remission.

While the patient eventually relapsed and died more than a year after receiving JCAR017, the brain tumor never recurred.

“Brain involvement in DLBCL carries a grave prognosis, and the ability to induce a complete and durable response with conventional therapies is rare,” said Jeremy Abramson, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“In addition, all available CAR T-cell trials have excluded patients with central nervous system involvement. This result has implications not only for secondary DLBCL like this case but also for primary central nervous system lymphoma, for which treatment options are similarly limited after relapse and few patents are cured.”

Dr Abramson and his colleagues described this case in a letter to NEJM. The patient was involved in a trial of JCAR017, which was sponsored by Juno Therapeutics.

The patient was a 68-year-old woman with germinal center B-cell-like DLBCL with a BCL2 rearrangement and multiple copies of MYC and BCL6.

The patients’ disease was refractory to conventional chemotherapy and an 8/8 HLA-matched stem cell transplant. After she enrolled in a phase 1 trial of JCAR017, the patient was found to have a new lesion in the right temporal lobe of her brain.

One month after the patient received JCAR017—given after lymphodepletion with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide—imaging showed complete remission of the brain lesion.

The subcutaneous lesion that recurred 2 months later disappeared after the biopsy with no further treatment. Blood testing showed an expansion of CAR T cells that coincided with the tumor’s regression.

While re-expansion of CAR T cells has been reported in response to other immunotherapy drugs, this is the first report of such a response to a biopsy.

“Typically, the drugs we use to fight cancer and other diseases wear off over time,” Dr Abramson said. “This spontaneous re-expansion after biopsy highlights this therapy as something entirely different, a ‘living drug’ that can re-expand and proliferate in response to biologic stimuli.” ![]()

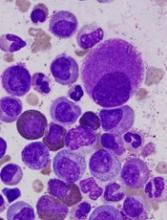

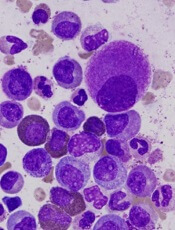

TKI granted priority review for newly diagnosed CML

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review to a supplemental new drug application (sNDA) for the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) bosutinib (Bosulif®).

If approved, the sNDA would expand the use of bosutinib to include patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Bosutinib is currently FDA-approved to treat adults with chronic, accelerated, or blast phase Ph+ CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy.

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA plans to make a decision on the sNDA for bosutinib by the end of this year.

Meanwhile, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has validated for review a type II variation application for bosutinib in patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase Ph+ CML.

Bosutinib already has conditional marketing authorization in the European Economic Area for the treatment of adults with Ph+ CML who previously received at least 1 TKI and adults with Ph+ CML for whom imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib are not considered appropriate.

Phase 3 trial

The applications submitted to the EMA and FDA are both supported by early results from the phase 3 BFORE trial. Results from this trial were presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting in May.

In this ongoing study, researchers are comparing bosutinib and imatinib as first-line treatment of chronic phase CML.

As of the ASCO presentation, the trial had enrolled 536 patients who were randomized 1:1 to receive bosutinib (n=268) or imatinib (n=268).

The presentation included results in a modified intent-to-treat population of Ph+ patients with e13a2/e14a2 transcripts who had at least 12 months of follow-up. In this group, there were 246 patients in the bosutinib arm and 241 in the imatinib arm.

Most of the patients were still on therapy at the 12-month mark or beyond—78% in the bosutinib arm and 73.2% in the imatinib arm. The median treatment duration was 14.1 months and 13.8 months, respectively.

At 12 months, the rate of major molecular response was 47.2% in the bosutinib arm and 36.9% in the imatinib arm (P= 0.02). The rate of complete cytogenetic response was 77.2% and 66.4%, respectively (P<0.008).

One patient in the bosutinib arm and 4 in the imatinib arm discontinued treatment due to disease progression, while 12.7% and 8.7%, respectively, discontinued treatment due to drug-related toxicity.

Adverse events that were more common in the bosutinib arm than the imatinib arm included grade 3 or higher diarrhea (7.8% vs 0.8%), increased alanine levels (19% vs 1.5%), increased aspartate levels (9.7% vs 1.9%), cardiovascular events (3% vs 0.4%), and peripheral vascular events (1.5% vs 1.1%). Cerebrovascular events were more common with imatinib than bosutinib (0.4% and 0%, respectively). ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review to a supplemental new drug application (sNDA) for the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) bosutinib (Bosulif®).

If approved, the sNDA would expand the use of bosutinib to include patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Bosutinib is currently FDA-approved to treat adults with chronic, accelerated, or blast phase Ph+ CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy.

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA plans to make a decision on the sNDA for bosutinib by the end of this year.

Meanwhile, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has validated for review a type II variation application for bosutinib in patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase Ph+ CML.

Bosutinib already has conditional marketing authorization in the European Economic Area for the treatment of adults with Ph+ CML who previously received at least 1 TKI and adults with Ph+ CML for whom imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib are not considered appropriate.

Phase 3 trial

The applications submitted to the EMA and FDA are both supported by early results from the phase 3 BFORE trial. Results from this trial were presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting in May.

In this ongoing study, researchers are comparing bosutinib and imatinib as first-line treatment of chronic phase CML.

As of the ASCO presentation, the trial had enrolled 536 patients who were randomized 1:1 to receive bosutinib (n=268) or imatinib (n=268).

The presentation included results in a modified intent-to-treat population of Ph+ patients with e13a2/e14a2 transcripts who had at least 12 months of follow-up. In this group, there were 246 patients in the bosutinib arm and 241 in the imatinib arm.

Most of the patients were still on therapy at the 12-month mark or beyond—78% in the bosutinib arm and 73.2% in the imatinib arm. The median treatment duration was 14.1 months and 13.8 months, respectively.

At 12 months, the rate of major molecular response was 47.2% in the bosutinib arm and 36.9% in the imatinib arm (P= 0.02). The rate of complete cytogenetic response was 77.2% and 66.4%, respectively (P<0.008).

One patient in the bosutinib arm and 4 in the imatinib arm discontinued treatment due to disease progression, while 12.7% and 8.7%, respectively, discontinued treatment due to drug-related toxicity.

Adverse events that were more common in the bosutinib arm than the imatinib arm included grade 3 or higher diarrhea (7.8% vs 0.8%), increased alanine levels (19% vs 1.5%), increased aspartate levels (9.7% vs 1.9%), cardiovascular events (3% vs 0.4%), and peripheral vascular events (1.5% vs 1.1%). Cerebrovascular events were more common with imatinib than bosutinib (0.4% and 0%, respectively). ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review to a supplemental new drug application (sNDA) for the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) bosutinib (Bosulif®).

If approved, the sNDA would expand the use of bosutinib to include patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Bosutinib is currently FDA-approved to treat adults with chronic, accelerated, or blast phase Ph+ CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy.

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA plans to make a decision on the sNDA for bosutinib by the end of this year.

Meanwhile, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has validated for review a type II variation application for bosutinib in patients with newly diagnosed, chronic phase Ph+ CML.

Bosutinib already has conditional marketing authorization in the European Economic Area for the treatment of adults with Ph+ CML who previously received at least 1 TKI and adults with Ph+ CML for whom imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib are not considered appropriate.

Phase 3 trial

The applications submitted to the EMA and FDA are both supported by early results from the phase 3 BFORE trial. Results from this trial were presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting in May.

In this ongoing study, researchers are comparing bosutinib and imatinib as first-line treatment of chronic phase CML.

As of the ASCO presentation, the trial had enrolled 536 patients who were randomized 1:1 to receive bosutinib (n=268) or imatinib (n=268).

The presentation included results in a modified intent-to-treat population of Ph+ patients with e13a2/e14a2 transcripts who had at least 12 months of follow-up. In this group, there were 246 patients in the bosutinib arm and 241 in the imatinib arm.

Most of the patients were still on therapy at the 12-month mark or beyond—78% in the bosutinib arm and 73.2% in the imatinib arm. The median treatment duration was 14.1 months and 13.8 months, respectively.

At 12 months, the rate of major molecular response was 47.2% in the bosutinib arm and 36.9% in the imatinib arm (P= 0.02). The rate of complete cytogenetic response was 77.2% and 66.4%, respectively (P<0.008).

One patient in the bosutinib arm and 4 in the imatinib arm discontinued treatment due to disease progression, while 12.7% and 8.7%, respectively, discontinued treatment due to drug-related toxicity.

Adverse events that were more common in the bosutinib arm than the imatinib arm included grade 3 or higher diarrhea (7.8% vs 0.8%), increased alanine levels (19% vs 1.5%), increased aspartate levels (9.7% vs 1.9%), cardiovascular events (3% vs 0.4%), and peripheral vascular events (1.5% vs 1.1%). Cerebrovascular events were more common with imatinib than bosutinib (0.4% and 0%, respectively). ![]()

HERDOO2 may guide duration of treatment for unprovoked VTE

Clinical Question: Can HERDOO2 guide anticoagulation cessation in women with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Background: Patients with unprovoked VTE have increased recurrence rates after stopping anticoagulation, but no tools have been validated to identify low risk patients.

Setting: Forty-four referral centers in seven countries.

Synopsis: Of patients with unprovoked, symptomatic VTE, 2,747 were evaluated after receiving anticoagulation for 5-12 months. HERDOO2 was used to classify women as low (0-1 points) or high (equal to or greater than 2 points) risk categories. Men were considered high risk. Anticoagulation was stopped for low risk patients. Treatment of high risk patients was left to physician choice.

Overall, high risk patients who continued anticoagulation had a 1.6% recurrence rate. Low risk women who stopped anticoagulation had a 3% recurrence rate per patient year, but postmenopausal women aged 50 years or older had a rate of 5.7%. High risk patients who stopped anticoagulation had a 7.4% recurrence rate. This study included multiple sites, but only 44% of participants were women. HERDOO2 should be used cautiously in postmenopausal women aged 50 years or older and in nonwhite women.

Bottom Line: HERDOO2 may help guide the decision to stop anticoagulation in select low-risk women with unprovoked VTE.

Citation: Rodger MA, Gregoire LG, Anderson DR, et al. Validating the HERDOO2 rule to guide treatment duration for women with unprovoked venous thrombosis: Multinational prospective cohort management study. BMJ. 2017 March;356:j1065.

Dr. Helfrich is an assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine.

Clinical Question: Can HERDOO2 guide anticoagulation cessation in women with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Background: Patients with unprovoked VTE have increased recurrence rates after stopping anticoagulation, but no tools have been validated to identify low risk patients.

Setting: Forty-four referral centers in seven countries.

Synopsis: Of patients with unprovoked, symptomatic VTE, 2,747 were evaluated after receiving anticoagulation for 5-12 months. HERDOO2 was used to classify women as low (0-1 points) or high (equal to or greater than 2 points) risk categories. Men were considered high risk. Anticoagulation was stopped for low risk patients. Treatment of high risk patients was left to physician choice.

Overall, high risk patients who continued anticoagulation had a 1.6% recurrence rate. Low risk women who stopped anticoagulation had a 3% recurrence rate per patient year, but postmenopausal women aged 50 years or older had a rate of 5.7%. High risk patients who stopped anticoagulation had a 7.4% recurrence rate. This study included multiple sites, but only 44% of participants were women. HERDOO2 should be used cautiously in postmenopausal women aged 50 years or older and in nonwhite women.

Bottom Line: HERDOO2 may help guide the decision to stop anticoagulation in select low-risk women with unprovoked VTE.

Citation: Rodger MA, Gregoire LG, Anderson DR, et al. Validating the HERDOO2 rule to guide treatment duration for women with unprovoked venous thrombosis: Multinational prospective cohort management study. BMJ. 2017 March;356:j1065.

Dr. Helfrich is an assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine.

Clinical Question: Can HERDOO2 guide anticoagulation cessation in women with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Background: Patients with unprovoked VTE have increased recurrence rates after stopping anticoagulation, but no tools have been validated to identify low risk patients.

Setting: Forty-four referral centers in seven countries.

Synopsis: Of patients with unprovoked, symptomatic VTE, 2,747 were evaluated after receiving anticoagulation for 5-12 months. HERDOO2 was used to classify women as low (0-1 points) or high (equal to or greater than 2 points) risk categories. Men were considered high risk. Anticoagulation was stopped for low risk patients. Treatment of high risk patients was left to physician choice.

Overall, high risk patients who continued anticoagulation had a 1.6% recurrence rate. Low risk women who stopped anticoagulation had a 3% recurrence rate per patient year, but postmenopausal women aged 50 years or older had a rate of 5.7%. High risk patients who stopped anticoagulation had a 7.4% recurrence rate. This study included multiple sites, but only 44% of participants were women. HERDOO2 should be used cautiously in postmenopausal women aged 50 years or older and in nonwhite women.

Bottom Line: HERDOO2 may help guide the decision to stop anticoagulation in select low-risk women with unprovoked VTE.

Citation: Rodger MA, Gregoire LG, Anderson DR, et al. Validating the HERDOO2 rule to guide treatment duration for women with unprovoked venous thrombosis: Multinational prospective cohort management study. BMJ. 2017 March;356:j1065.

Dr. Helfrich is an assistant professor in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine.

50 years of pediatric dermatology

The world in pediatric dermatology has changed in incredible ways since 1967. In fact, pediatric dermatology was not an organized specialty until years later! This article will look back at some of the history of pediatric dermatology, exploring how different the field was 50 years ago, and how it has evolved into the vibrant field that it is. By looking at some disease states, and differences in practice in relation to the care of dermatologic conditions in children both by pediatricians and dermatologists, we can see the tremendous evolution in our understanding and management of pediatric skin conditions, and perhaps gain insight into the future.

Pediatric dermatology was fairly “neonatal” 50 years ago, with only a few practitioners in the field. Recognizing that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits include a skin-related problem, and that there was limited training about skin diseases among primary care practitioners and inconsistent training amongst dermatologists, there was a clinical need for establishing the subspecialty of pediatric dermatology. The first international symposium was held in Mexico City in October 1972, and with this meeting the International Society of Pediatric Dermatology was founded. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) began in 1973, with Alvin Jacobs, MD, Samuel Weinberg, MD, Nancy Esterly, MD, Sidney Hurwitz, MD, William Weston, MD, and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers.” The journal Pediatric Dermatology released its first issue in 1982 (35 years ago), and the American Academy of Pediatrics did not have a section of dermatology until 1986.

Pediatrics and dermatology: The interface

Many of the first generation of pediatric dermatologists trained as pediatricians prior to pursuing their dermatology work, with some being “assigned” dermatology as pediatric experts, while others did formal residencies in dermatology. This history is important, as pediatric dermatology was, and remains, integrated with pediatrics, even while training in dermatology residencies became standard practice. An important part of the development of the field has been the education of pediatricians and dermatologists by pediatric dermatologists, with a strong sensibility that improved training for both generalists and specialists about pediatric skin disease would yield better care for patients and families.

Initially, there were very few pediatric or dermatology programs in the United States that had pediatric dermatologists. Over the succeeding decades, this is now less common, although even now there are still dermatology and pediatric residency programs that do not have a pediatric dermatologist for either training or to serve their patients. The founding leaders of the SPD set a tone of collaboration nationally and internationally, reaching out to pediatric colleagues and dermatology associates from around the world, and establishing superb educational programs for the exchange of ideas, presentation of challenging cases, and promoting state of the art knowledge of the field. Through annual meetings of the SPD, conferences immediately preceding the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings, the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology, and other regional and international meetings, the field developed as the number of practitioners grew, and as the specialized published literature reflected new knowledge in diagnosis and therapy.

Building upon the history of collaboration and reflecting the maturation of the field with a desire to influence the breadth and quantity of research in pediatric dermatology, the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) was formed in 2012. This organization was formed to promote and facilitate high quality collaborative clinical, translational, educational, and basic science research in pediatric dermatology with a vision to create sustainable, collaborative networks to better understand, prevent, treat, and cure dermatologic diseases in children. This network is now composed of over 230 members representing over 68 institutions from the United States and Canada, but including involvement globally from Mexico, Europe, and the Middle East.

Examples of changing perspectives: hemangiomas

A good way to look at evolution of the field is take a look at some of the similarities and differences in clinical practice in relation to common and uncommon disease states.

A great example is hemangiomas. Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that many lesions had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of course, the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” in the trade), was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized variant tumors that were distinct, such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, and hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa brain malformations) had yet to be described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden and her colleagues). For a time period, hemangiomas were treated with X-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. For many years after that, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, presumably a backlash from the radiation therapy interventions.

This story also reflects how organized research efforts helped with the evolution of knowledge and clinical care. The Hemangioma of Infancy Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists, and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: Tremendous revolution in surgery and laser

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. And how important this specialty work was! Acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, diaper and seborrheic dermatitis, and rare genetic syndromes, these conditions were a major part of the work of early pediatric dermatologists (and remain so now). What was not common was for pediatric dermatologists to have procedural or surgical practices, while this now is routinely part of the work of specialists in the field. How did this shift occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser in 1989 and the publication of a seminal article in the New England Journal of Medicine (1989 Feb 16;320[7]:416-21) on its utility in treating port-wine stains in children with minimal scarring. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists had the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the pediatric knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age appropriate manner, and consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota), hair lasers (to treat perineal areas to prevent pilonidal cyst recurrence or to treat hirsutism), and combinations of lasers to treat hypertrophic, constrictive, and/or deforming scars).

Inflammatory skin disorders: Bread and butter ... and peanut butter?

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris now is recognized as much more common under age 12 years than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later. Pediatric acne expert recommendations were formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013 (Pediatrics. 2013;131:S163-86). Over the past few years, there is a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance.

Psoriasis has been a condition that has been “behind the revolution,” in that no biologic agent was approved for pediatric psoriasis in the United States until several months ago, lagging behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, and new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis in adults is now tremendously controllable with biologic agents targeting TNF-alpha, IL 12/23, and IL-17. Etanercept has been approved for children with psoriasis aged 4 years and older, and other biologic agents are under study.

Atopic dermatitis now is ready for its revolution! AD has increased in prevalence from around 5% of the pediatric population 30-plus years ago to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their utilization of these useful agents.

It has been recognized for years that children with AD have higher risk of developing food allergies than children without AD. A changing understanding of how early food exposure may induce tolerance is changing the world of allergy and influencing the care of children with AD. This is where the peanut butter (or other processed peanut, such as “Bamba”) may be life saving. New guidelines have come from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases recommending that infants with severe eczema (or egg allergy, or both) have introduction of age-appropriate peanut-containing food as early as 4-6 months of age to reduce the risk of development of peanut allergy. It is recommended that these infants undergo early evaluation for possible sensitization to peanut protein, with referral to allergists for skin prick tests or serum IgE screens (though if positive, referral to allergists is appropriate), and assess the safety of going ahead with early feeding. It is hoped that following these new guidelines can minimize the development of peanut allergy.

The future

Where will pediatric skin disease, or more importantly, skin health over a lifetime be in 50 years? Can we cure or prevent the consequences of our lethal and life altering genetic diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa or our neurocutaneous disorders? Will our new insights into birthmarks (they are mostly somatic mutations) allow us to form specific, personalized therapies to minimize their impact? Will we be using computers equipped with imaging devices and algorithms to assess our patients’ moles, papules, and nodules? Will our vaccines have wiped out warts, molluscum, and perhaps, acne? Will we have cured our inflammatory skin disorders, or perhaps prevented them by interventions in the neonatal period? No predictions will be offered here, other than that we can look forward to incredible changes for our future generations of health care practitioners, patients, and families.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield has served as a consultant for Anacor/Pfizer and Regeneron/Sanofi. Email him at [email protected].

The world in pediatric dermatology has changed in incredible ways since 1967. In fact, pediatric dermatology was not an organized specialty until years later! This article will look back at some of the history of pediatric dermatology, exploring how different the field was 50 years ago, and how it has evolved into the vibrant field that it is. By looking at some disease states, and differences in practice in relation to the care of dermatologic conditions in children both by pediatricians and dermatologists, we can see the tremendous evolution in our understanding and management of pediatric skin conditions, and perhaps gain insight into the future.

Pediatric dermatology was fairly “neonatal” 50 years ago, with only a few practitioners in the field. Recognizing that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits include a skin-related problem, and that there was limited training about skin diseases among primary care practitioners and inconsistent training amongst dermatologists, there was a clinical need for establishing the subspecialty of pediatric dermatology. The first international symposium was held in Mexico City in October 1972, and with this meeting the International Society of Pediatric Dermatology was founded. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) began in 1973, with Alvin Jacobs, MD, Samuel Weinberg, MD, Nancy Esterly, MD, Sidney Hurwitz, MD, William Weston, MD, and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers.” The journal Pediatric Dermatology released its first issue in 1982 (35 years ago), and the American Academy of Pediatrics did not have a section of dermatology until 1986.

Pediatrics and dermatology: The interface

Many of the first generation of pediatric dermatologists trained as pediatricians prior to pursuing their dermatology work, with some being “assigned” dermatology as pediatric experts, while others did formal residencies in dermatology. This history is important, as pediatric dermatology was, and remains, integrated with pediatrics, even while training in dermatology residencies became standard practice. An important part of the development of the field has been the education of pediatricians and dermatologists by pediatric dermatologists, with a strong sensibility that improved training for both generalists and specialists about pediatric skin disease would yield better care for patients and families.

Initially, there were very few pediatric or dermatology programs in the United States that had pediatric dermatologists. Over the succeeding decades, this is now less common, although even now there are still dermatology and pediatric residency programs that do not have a pediatric dermatologist for either training or to serve their patients. The founding leaders of the SPD set a tone of collaboration nationally and internationally, reaching out to pediatric colleagues and dermatology associates from around the world, and establishing superb educational programs for the exchange of ideas, presentation of challenging cases, and promoting state of the art knowledge of the field. Through annual meetings of the SPD, conferences immediately preceding the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings, the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology, and other regional and international meetings, the field developed as the number of practitioners grew, and as the specialized published literature reflected new knowledge in diagnosis and therapy.

Building upon the history of collaboration and reflecting the maturation of the field with a desire to influence the breadth and quantity of research in pediatric dermatology, the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) was formed in 2012. This organization was formed to promote and facilitate high quality collaborative clinical, translational, educational, and basic science research in pediatric dermatology with a vision to create sustainable, collaborative networks to better understand, prevent, treat, and cure dermatologic diseases in children. This network is now composed of over 230 members representing over 68 institutions from the United States and Canada, but including involvement globally from Mexico, Europe, and the Middle East.

Examples of changing perspectives: hemangiomas

A good way to look at evolution of the field is take a look at some of the similarities and differences in clinical practice in relation to common and uncommon disease states.

A great example is hemangiomas. Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that many lesions had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of course, the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” in the trade), was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized variant tumors that were distinct, such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, and hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa brain malformations) had yet to be described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden and her colleagues). For a time period, hemangiomas were treated with X-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. For many years after that, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, presumably a backlash from the radiation therapy interventions.

This story also reflects how organized research efforts helped with the evolution of knowledge and clinical care. The Hemangioma of Infancy Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists, and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: Tremendous revolution in surgery and laser

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. And how important this specialty work was! Acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, diaper and seborrheic dermatitis, and rare genetic syndromes, these conditions were a major part of the work of early pediatric dermatologists (and remain so now). What was not common was for pediatric dermatologists to have procedural or surgical practices, while this now is routinely part of the work of specialists in the field. How did this shift occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser in 1989 and the publication of a seminal article in the New England Journal of Medicine (1989 Feb 16;320[7]:416-21) on its utility in treating port-wine stains in children with minimal scarring. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists had the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the pediatric knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age appropriate manner, and consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota), hair lasers (to treat perineal areas to prevent pilonidal cyst recurrence or to treat hirsutism), and combinations of lasers to treat hypertrophic, constrictive, and/or deforming scars).

Inflammatory skin disorders: Bread and butter ... and peanut butter?

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris now is recognized as much more common under age 12 years than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later. Pediatric acne expert recommendations were formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013 (Pediatrics. 2013;131:S163-86). Over the past few years, there is a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance.

Psoriasis has been a condition that has been “behind the revolution,” in that no biologic agent was approved for pediatric psoriasis in the United States until several months ago, lagging behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, and new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis in adults is now tremendously controllable with biologic agents targeting TNF-alpha, IL 12/23, and IL-17. Etanercept has been approved for children with psoriasis aged 4 years and older, and other biologic agents are under study.

Atopic dermatitis now is ready for its revolution! AD has increased in prevalence from around 5% of the pediatric population 30-plus years ago to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their utilization of these useful agents.

It has been recognized for years that children with AD have higher risk of developing food allergies than children without AD. A changing understanding of how early food exposure may induce tolerance is changing the world of allergy and influencing the care of children with AD. This is where the peanut butter (or other processed peanut, such as “Bamba”) may be life saving. New guidelines have come from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases recommending that infants with severe eczema (or egg allergy, or both) have introduction of age-appropriate peanut-containing food as early as 4-6 months of age to reduce the risk of development of peanut allergy. It is recommended that these infants undergo early evaluation for possible sensitization to peanut protein, with referral to allergists for skin prick tests or serum IgE screens (though if positive, referral to allergists is appropriate), and assess the safety of going ahead with early feeding. It is hoped that following these new guidelines can minimize the development of peanut allergy.

The future

Where will pediatric skin disease, or more importantly, skin health over a lifetime be in 50 years? Can we cure or prevent the consequences of our lethal and life altering genetic diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa or our neurocutaneous disorders? Will our new insights into birthmarks (they are mostly somatic mutations) allow us to form specific, personalized therapies to minimize their impact? Will we be using computers equipped with imaging devices and algorithms to assess our patients’ moles, papules, and nodules? Will our vaccines have wiped out warts, molluscum, and perhaps, acne? Will we have cured our inflammatory skin disorders, or perhaps prevented them by interventions in the neonatal period? No predictions will be offered here, other than that we can look forward to incredible changes for our future generations of health care practitioners, patients, and families.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield has served as a consultant for Anacor/Pfizer and Regeneron/Sanofi. Email him at [email protected].

The world in pediatric dermatology has changed in incredible ways since 1967. In fact, pediatric dermatology was not an organized specialty until years later! This article will look back at some of the history of pediatric dermatology, exploring how different the field was 50 years ago, and how it has evolved into the vibrant field that it is. By looking at some disease states, and differences in practice in relation to the care of dermatologic conditions in children both by pediatricians and dermatologists, we can see the tremendous evolution in our understanding and management of pediatric skin conditions, and perhaps gain insight into the future.

Pediatric dermatology was fairly “neonatal” 50 years ago, with only a few practitioners in the field. Recognizing that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits include a skin-related problem, and that there was limited training about skin diseases among primary care practitioners and inconsistent training amongst dermatologists, there was a clinical need for establishing the subspecialty of pediatric dermatology. The first international symposium was held in Mexico City in October 1972, and with this meeting the International Society of Pediatric Dermatology was founded. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) began in 1973, with Alvin Jacobs, MD, Samuel Weinberg, MD, Nancy Esterly, MD, Sidney Hurwitz, MD, William Weston, MD, and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers.” The journal Pediatric Dermatology released its first issue in 1982 (35 years ago), and the American Academy of Pediatrics did not have a section of dermatology until 1986.

Pediatrics and dermatology: The interface

Many of the first generation of pediatric dermatologists trained as pediatricians prior to pursuing their dermatology work, with some being “assigned” dermatology as pediatric experts, while others did formal residencies in dermatology. This history is important, as pediatric dermatology was, and remains, integrated with pediatrics, even while training in dermatology residencies became standard practice. An important part of the development of the field has been the education of pediatricians and dermatologists by pediatric dermatologists, with a strong sensibility that improved training for both generalists and specialists about pediatric skin disease would yield better care for patients and families.

Initially, there were very few pediatric or dermatology programs in the United States that had pediatric dermatologists. Over the succeeding decades, this is now less common, although even now there are still dermatology and pediatric residency programs that do not have a pediatric dermatologist for either training or to serve their patients. The founding leaders of the SPD set a tone of collaboration nationally and internationally, reaching out to pediatric colleagues and dermatology associates from around the world, and establishing superb educational programs for the exchange of ideas, presentation of challenging cases, and promoting state of the art knowledge of the field. Through annual meetings of the SPD, conferences immediately preceding the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings, the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology, and other regional and international meetings, the field developed as the number of practitioners grew, and as the specialized published literature reflected new knowledge in diagnosis and therapy.

Building upon the history of collaboration and reflecting the maturation of the field with a desire to influence the breadth and quantity of research in pediatric dermatology, the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) was formed in 2012. This organization was formed to promote and facilitate high quality collaborative clinical, translational, educational, and basic science research in pediatric dermatology with a vision to create sustainable, collaborative networks to better understand, prevent, treat, and cure dermatologic diseases in children. This network is now composed of over 230 members representing over 68 institutions from the United States and Canada, but including involvement globally from Mexico, Europe, and the Middle East.

Examples of changing perspectives: hemangiomas

A good way to look at evolution of the field is take a look at some of the similarities and differences in clinical practice in relation to common and uncommon disease states.

A great example is hemangiomas. Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that many lesions had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of course, the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” in the trade), was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized variant tumors that were distinct, such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, and hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa brain malformations) had yet to be described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden and her colleagues). For a time period, hemangiomas were treated with X-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. For many years after that, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, presumably a backlash from the radiation therapy interventions.

This story also reflects how organized research efforts helped with the evolution of knowledge and clinical care. The Hemangioma of Infancy Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists, and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: Tremendous revolution in surgery and laser

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. And how important this specialty work was! Acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, diaper and seborrheic dermatitis, and rare genetic syndromes, these conditions were a major part of the work of early pediatric dermatologists (and remain so now). What was not common was for pediatric dermatologists to have procedural or surgical practices, while this now is routinely part of the work of specialists in the field. How did this shift occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser in 1989 and the publication of a seminal article in the New England Journal of Medicine (1989 Feb 16;320[7]:416-21) on its utility in treating port-wine stains in children with minimal scarring. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists had the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the pediatric knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age appropriate manner, and consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota), hair lasers (to treat perineal areas to prevent pilonidal cyst recurrence or to treat hirsutism), and combinations of lasers to treat hypertrophic, constrictive, and/or deforming scars).

Inflammatory skin disorders: Bread and butter ... and peanut butter?

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris now is recognized as much more common under age 12 years than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later. Pediatric acne expert recommendations were formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013 (Pediatrics. 2013;131:S163-86). Over the past few years, there is a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance.

Psoriasis has been a condition that has been “behind the revolution,” in that no biologic agent was approved for pediatric psoriasis in the United States until several months ago, lagging behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, and new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis in adults is now tremendously controllable with biologic agents targeting TNF-alpha, IL 12/23, and IL-17. Etanercept has been approved for children with psoriasis aged 4 years and older, and other biologic agents are under study.

Atopic dermatitis now is ready for its revolution! AD has increased in prevalence from around 5% of the pediatric population 30-plus years ago to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their utilization of these useful agents.

It has been recognized for years that children with AD have higher risk of developing food allergies than children without AD. A changing understanding of how early food exposure may induce tolerance is changing the world of allergy and influencing the care of children with AD. This is where the peanut butter (or other processed peanut, such as “Bamba”) may be life saving. New guidelines have come from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases recommending that infants with severe eczema (or egg allergy, or both) have introduction of age-appropriate peanut-containing food as early as 4-6 months of age to reduce the risk of development of peanut allergy. It is recommended that these infants undergo early evaluation for possible sensitization to peanut protein, with referral to allergists for skin prick tests or serum IgE screens (though if positive, referral to allergists is appropriate), and assess the safety of going ahead with early feeding. It is hoped that following these new guidelines can minimize the development of peanut allergy.

The future

Where will pediatric skin disease, or more importantly, skin health over a lifetime be in 50 years? Can we cure or prevent the consequences of our lethal and life altering genetic diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa or our neurocutaneous disorders? Will our new insights into birthmarks (they are mostly somatic mutations) allow us to form specific, personalized therapies to minimize their impact? Will we be using computers equipped with imaging devices and algorithms to assess our patients’ moles, papules, and nodules? Will our vaccines have wiped out warts, molluscum, and perhaps, acne? Will we have cured our inflammatory skin disorders, or perhaps prevented them by interventions in the neonatal period? No predictions will be offered here, other than that we can look forward to incredible changes for our future generations of health care practitioners, patients, and families.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield has served as a consultant for Anacor/Pfizer and Regeneron/Sanofi. Email him at [email protected].

Suture found in bladder after hysterectomy

Suture found in bladder after hysterectomy

A 40-year-old woman underwent a hysterectomy due to dysmenorrhea. Despite the presence of blood in the catheter bag after the procedure, the surgeon did not consult a urologist or perform a cystoscopy. Later, when the patient reported urinary retention, urinary leakage, and dyspareunia, a urologist performed a cystoscopy and discovered a suture in the bladder wall and a vesicovaginal fistula.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

During the procedure, the gynecologic surgeon inadvertently placed a suture in the bladder wall. The presence of blood in the Foley catheter required an immediate urology consult and cystoscopy, during which the presence of the errant suture would have been discovered. Repair surgery then would have prevented subsequent injuries.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

The surgeon used reasonable judgment, as there were explanations for the blood in the catheter due to a difficult catheter placement and lysis of bladder adhesions.

VERDICT:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid intestinal and urinary tract injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy

Bowel injury during tubal ligation

A 40-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic tubal ligation using cauterization at an outpatient surgery center. Two hours after the procedure, her BP began to drop. She was promptly transferred to a hospital and underwent emergency surgery that revealed a bowel injury. Part of the patient’s small intestine was resected.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon committed a medical error when she injured the bowel during trocar insertion.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The bowel injury was a known complication of the surgery.

VERDICT:

A Louisiana defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

Colon injured twice: $1M settlement

A 59-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic total hysterectomy and salpingectomy. Her history included an umbilical hernia repair.

Two days after surgery, the patient experienced abdominal pain, chills, abdominal distention, and a foul-smelling discharge from her umbilical suture site. She went to the emergency department where a computed tomography scan revealed 2 injuries in the bowel. Emergency laparotomy included transverse colon resection and right colon colostomy with Hartmann’s pouch. She wore an ostomy bag for 8 months. She developed an infection because of the colostomy and also required operations to resolve a bowel obstruction and repair incisional hernias.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon was negligent when performing the surgery. When he inserted the Veress needle and trocar through the patient’s umbilicus, the transverse colon was injured twice with a 3-cm anterior tear and a 1-cm posterior laceration. The injuries were not discovered during the procedure. He should have been more careful knowing that she had undergone prior umbilical hernia surgery.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

The case was settled before the trial began.

VERDICT:

A $1 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Chronic pain after sling procedure: $2M verdict

A 63-year-old woman reported urinary incontinence to her gynecologist, who performed a transobturator midurethral sling procedure. After surgery, the patient experienced pelvic pain, urinary urgency, intermittent incontinence, and dyspareunia. She returned to the gynecologist twice. He performed a cystoscopy after the second visit but found nothing wrong.

The patient sought a second opinion. A gynecologic surgeon found a large mass in the patient’s bladder consisting of a crystallized piece of tape that had been used to secure the sling supporting the bladder. The mass was removed and the patient reported that, although surgery alleviated many symptoms, she was not pain-free.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologist negligently inserted the end of the sling through one wall of her bladder and failed to detect the malpositioning during surgery or later. He failed to diagnose and treat bladder stones that resulted from the sling’s malpositioning. He failed to perform a cystoscopy when she first reported symptoms and improperly performed cystoscopy at the second visit.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There was no negligence on the part of the gynecologist. The patient did not report ongoing symptoms until 1 year after sling insertion.

VERDICT:

A $2 million Pennsylvania verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Suture found in bladder after hysterectomy

A 40-year-old woman underwent a hysterectomy due to dysmenorrhea. Despite the presence of blood in the catheter bag after the procedure, the surgeon did not consult a urologist or perform a cystoscopy. Later, when the patient reported urinary retention, urinary leakage, and dyspareunia, a urologist performed a cystoscopy and discovered a suture in the bladder wall and a vesicovaginal fistula.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

During the procedure, the gynecologic surgeon inadvertently placed a suture in the bladder wall. The presence of blood in the Foley catheter required an immediate urology consult and cystoscopy, during which the presence of the errant suture would have been discovered. Repair surgery then would have prevented subsequent injuries.

PHYSICIANS' DEFENSE:

The surgeon used reasonable judgment, as there were explanations for the blood in the catheter due to a difficult catheter placement and lysis of bladder adhesions.

VERDICT:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid intestinal and urinary tract injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy

Bowel injury during tubal ligation

A 40-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic tubal ligation using cauterization at an outpatient surgery center. Two hours after the procedure, her BP began to drop. She was promptly transferred to a hospital and underwent emergency surgery that revealed a bowel injury. Part of the patient’s small intestine was resected.

PATIENTS' CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon committed a medical error when she injured the bowel during trocar insertion.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The bowel injury was a known complication of the surgery.

VERDICT:

A Louisiana defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

Colon injured twice: $1M settlement

A 59-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic total hysterectomy and salpingectomy. Her history included an umbilical hernia repair.